Attention deficit disorder dsm 5

Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD

COVID-19: Information for parenting children with ADHD

Learn more

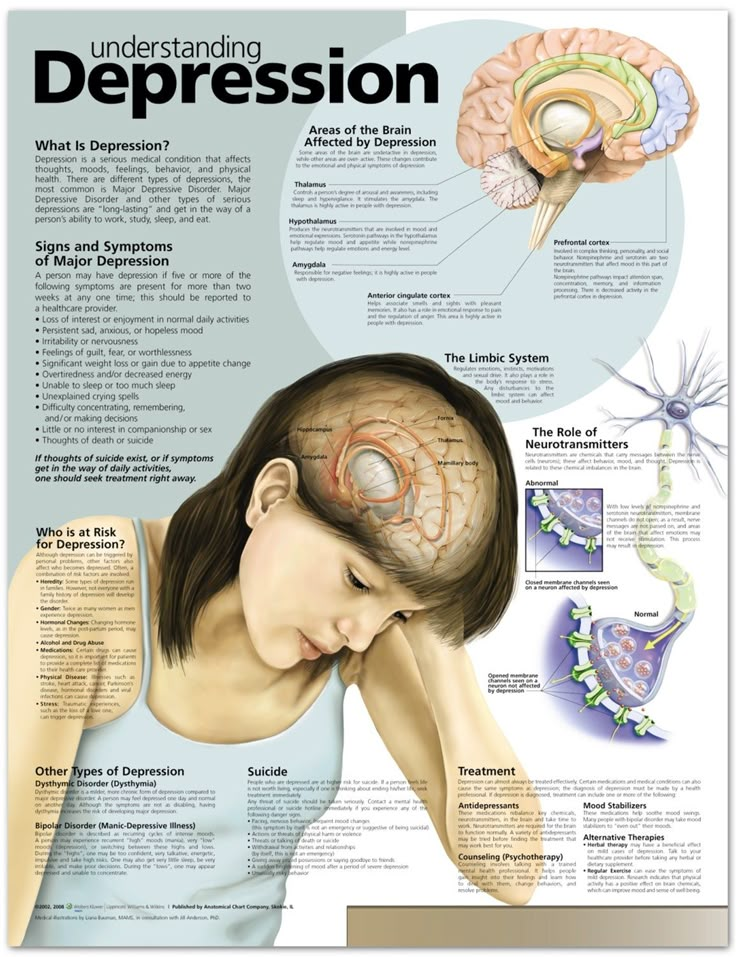

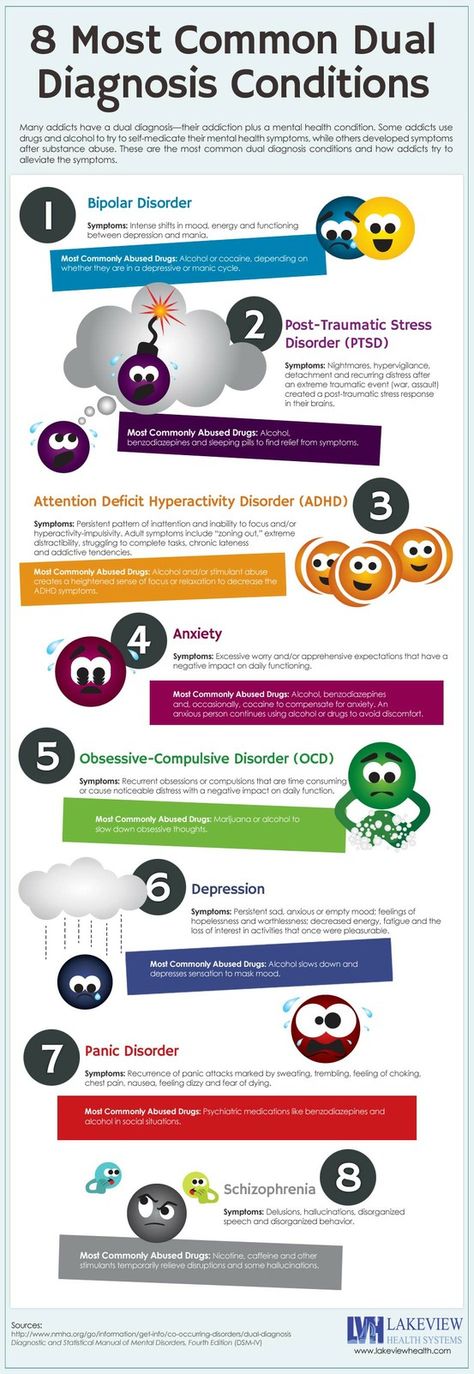

Deciding if a child has ADHD is a process with several steps. This page gives you an overview of how ADHD is diagnosed. There is no single test to diagnose ADHD, and many other problems, like sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and certain types of learning disabilities, can have similar symptoms.

If you are concerned about whether a child might have ADHD, the first step is to talk with a healthcare provider to find out if the symptoms fit the diagnosis. The diagnosis can be made by a mental health professional, like a psychologist or psychiatrist, or by a primary care provider, like a pediatrician.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that healthcare providers ask parents, teachers, and other adults who care for the child about the child’s behavior in different settings, like at home, school, or with peers. Read more about the recommendations.

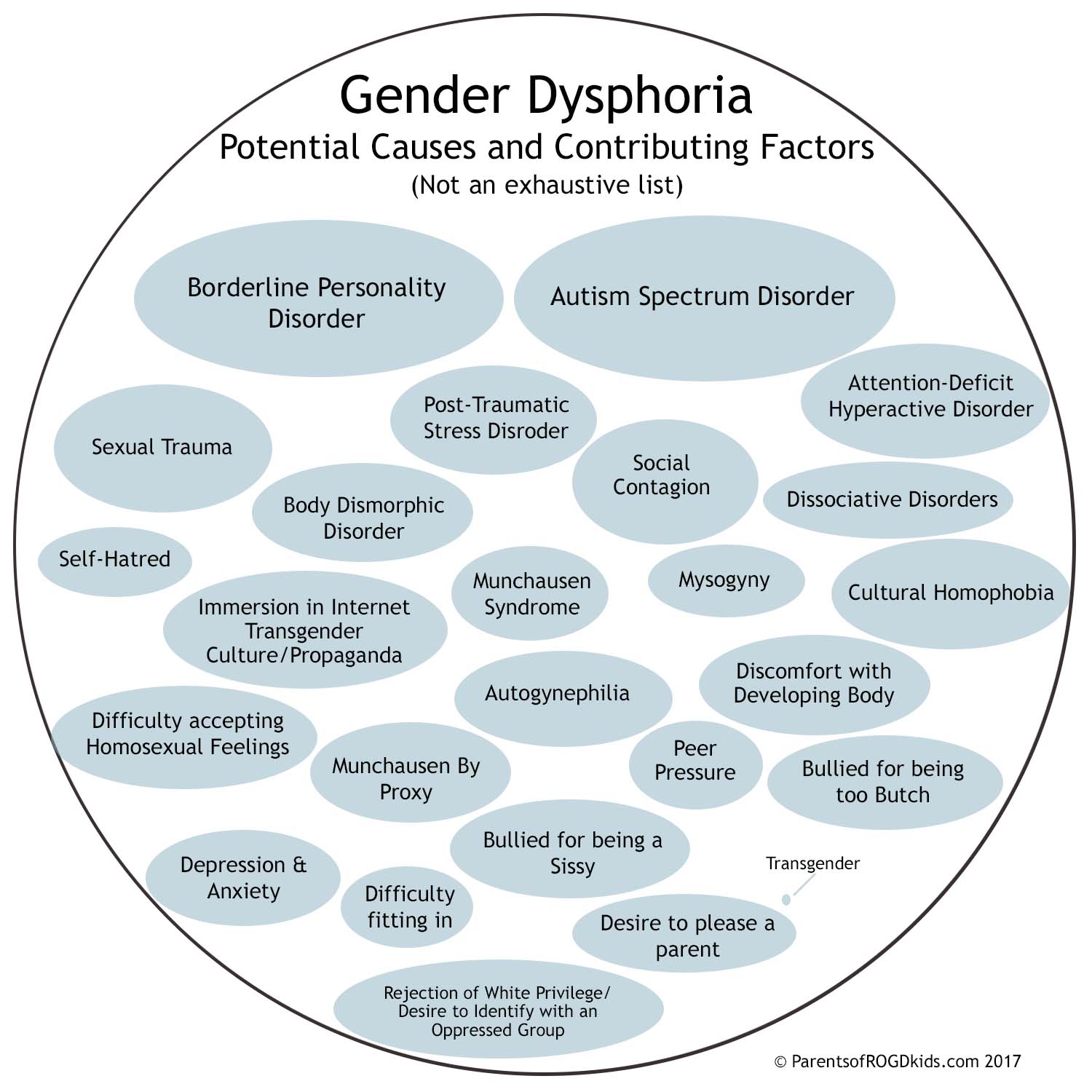

The healthcare provider should also determine whether the child has another condition that can either explain the symptoms better, or that occurs at the same time as ADHD. Read more about other concerns and conditions.

Why Family Health History is Important if Your Child has Attention and Learning Problems

How is ADHD diagnosed?

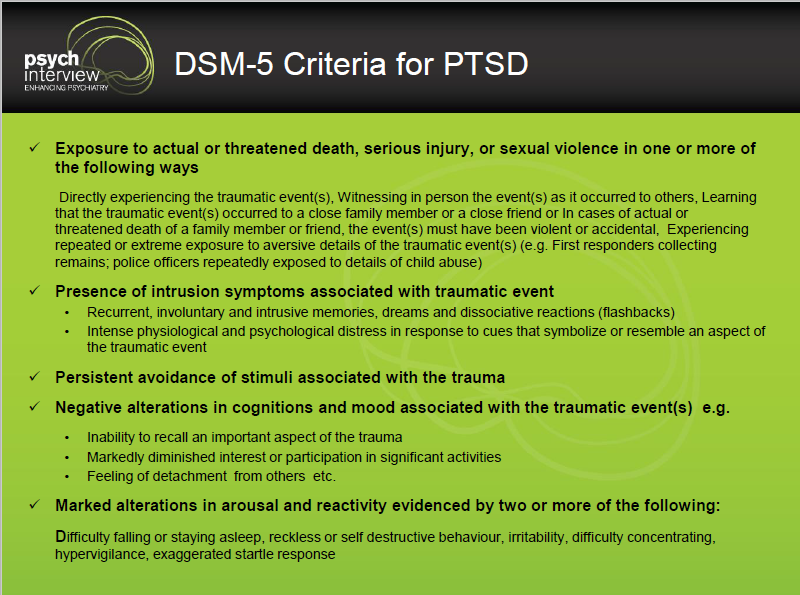

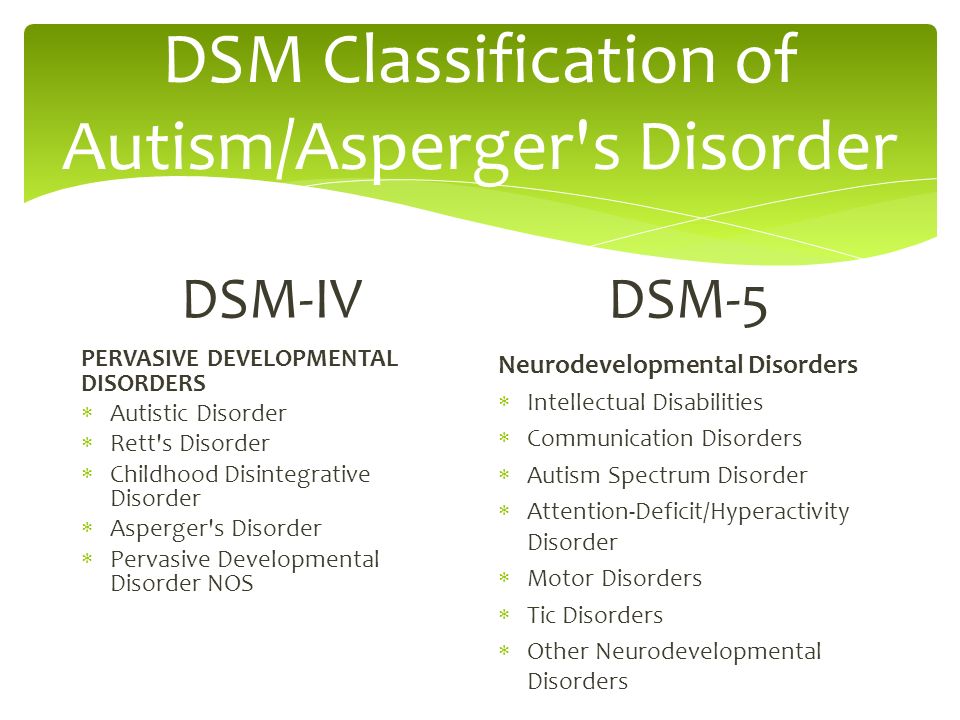

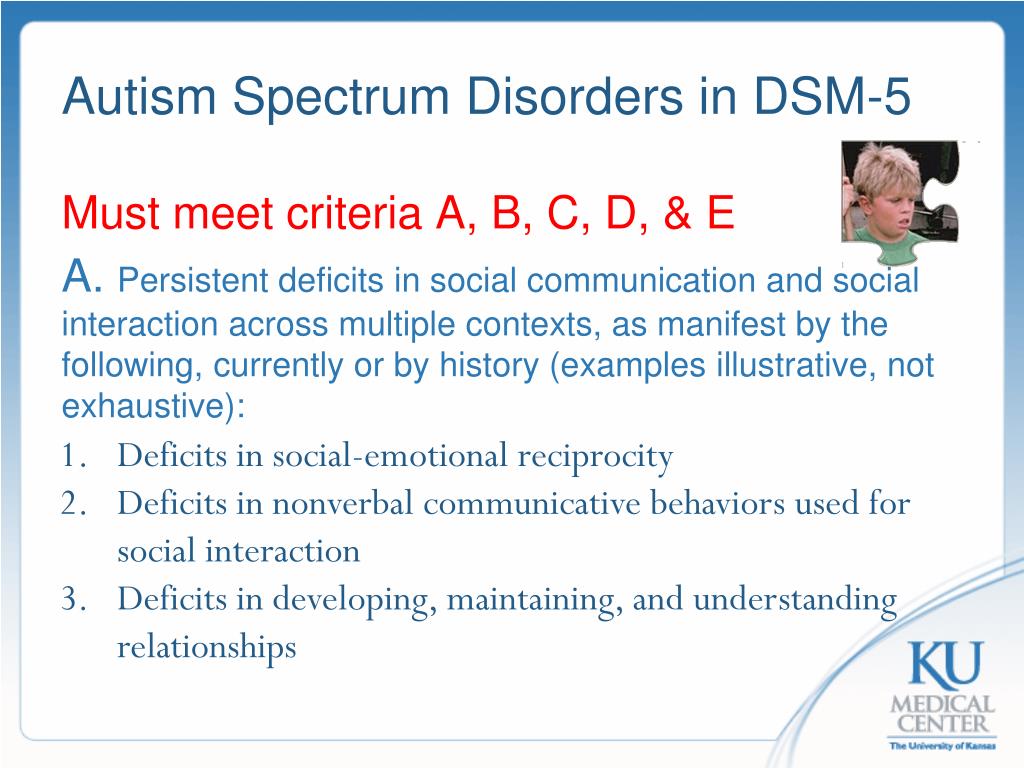

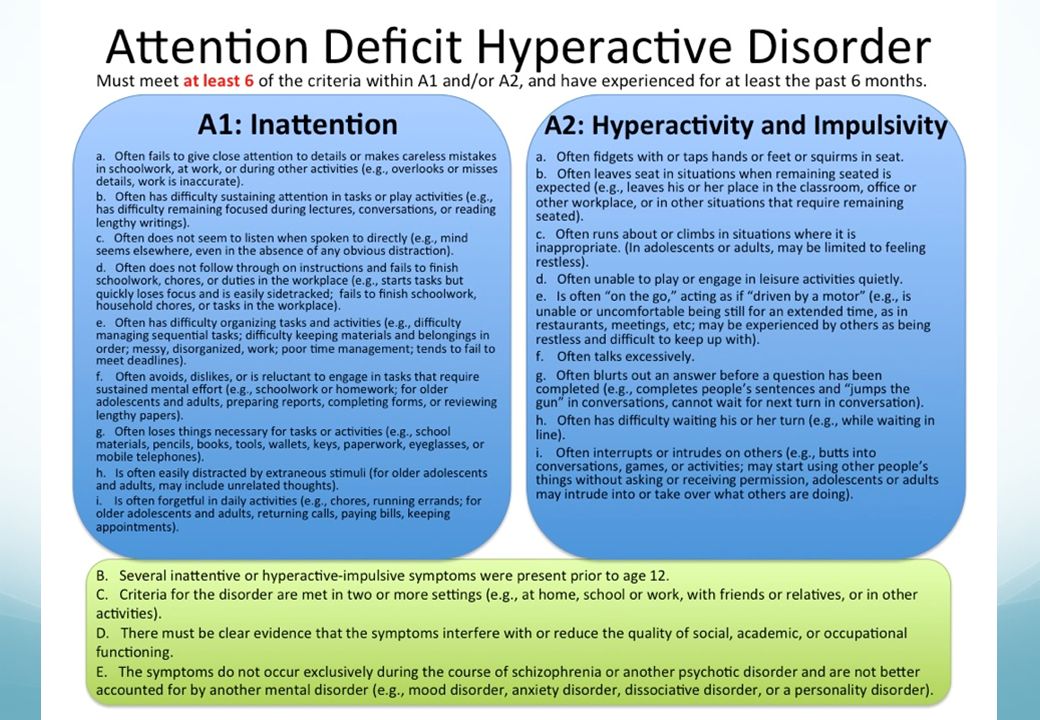

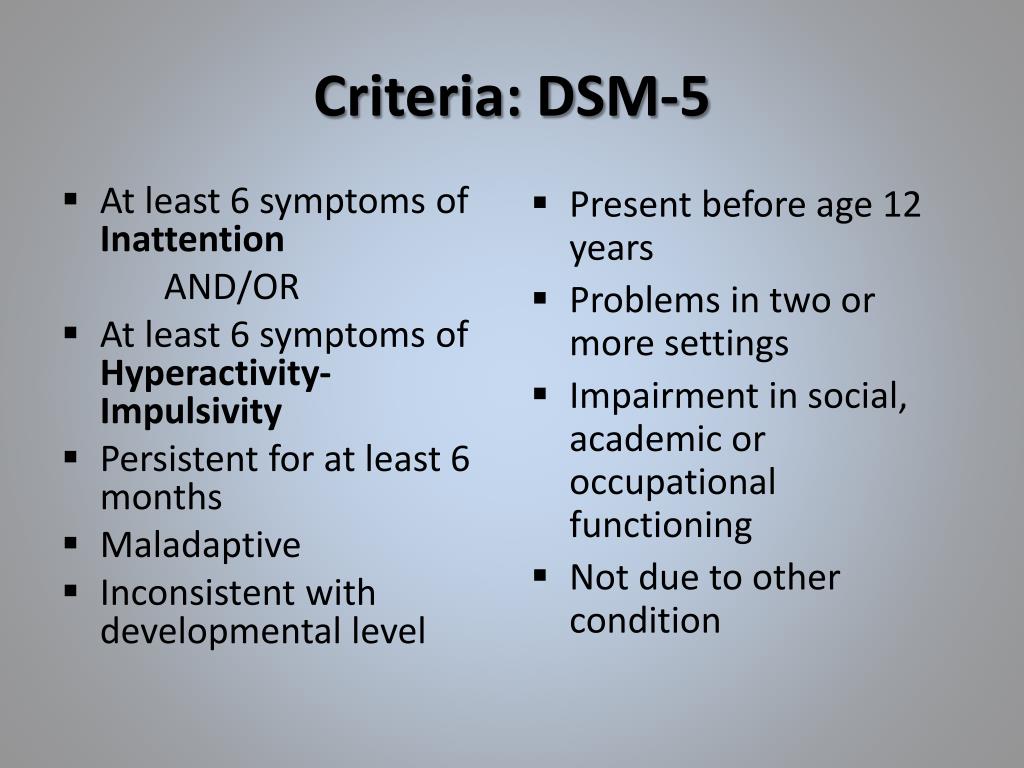

Healthcare providers use the guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth edition (DSM-5)1, to help diagnose ADHD. This diagnostic standard helps ensure that people are appropriately diagnosed and treated for ADHD. Using the same standard across communities can also help determine how many children have ADHD, and how public health is impacted by this condition.

Here are the criteria in shortened form. Please note that they are presented just for your information. Only trained healthcare providers can diagnose or treat ADHD.

Get information and support from the National Resource Center on ADHD

DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD

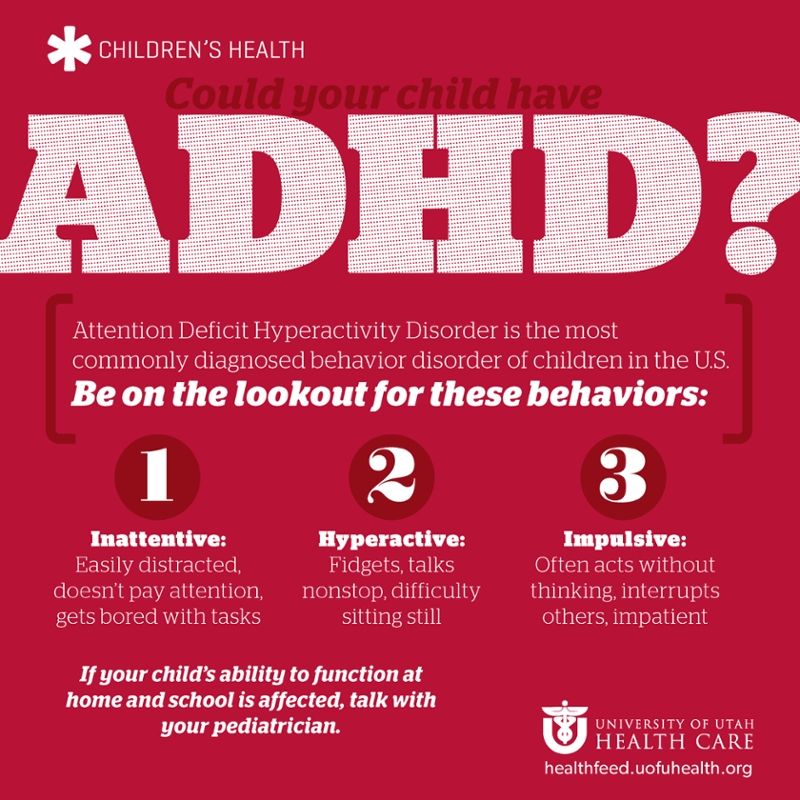

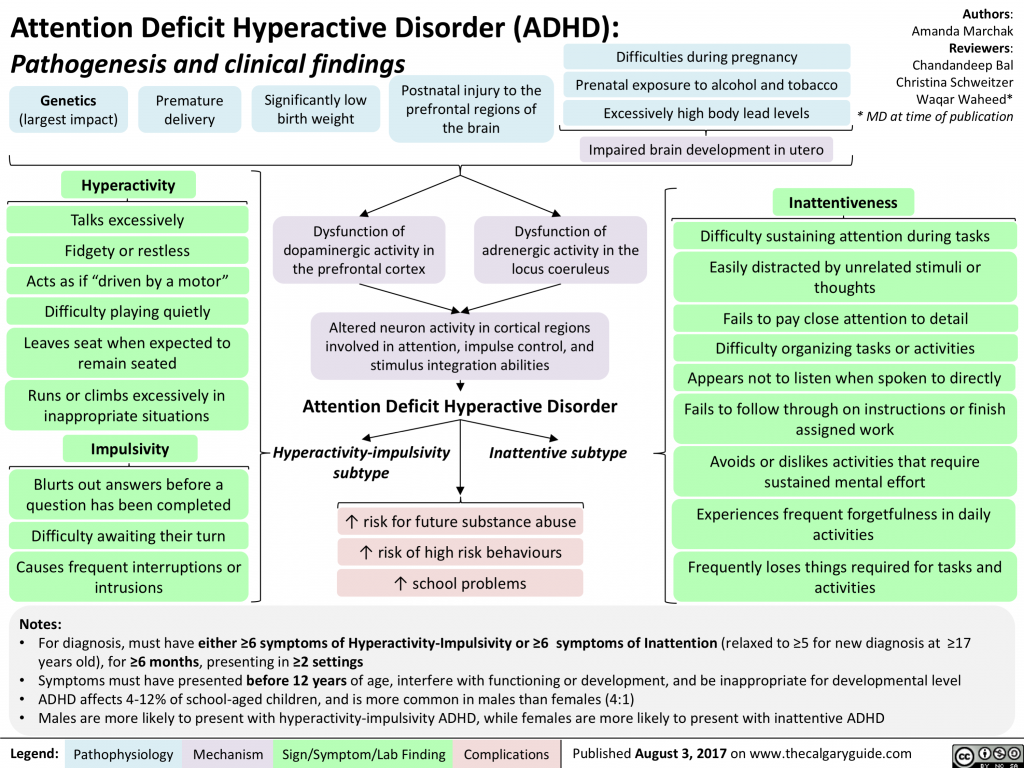

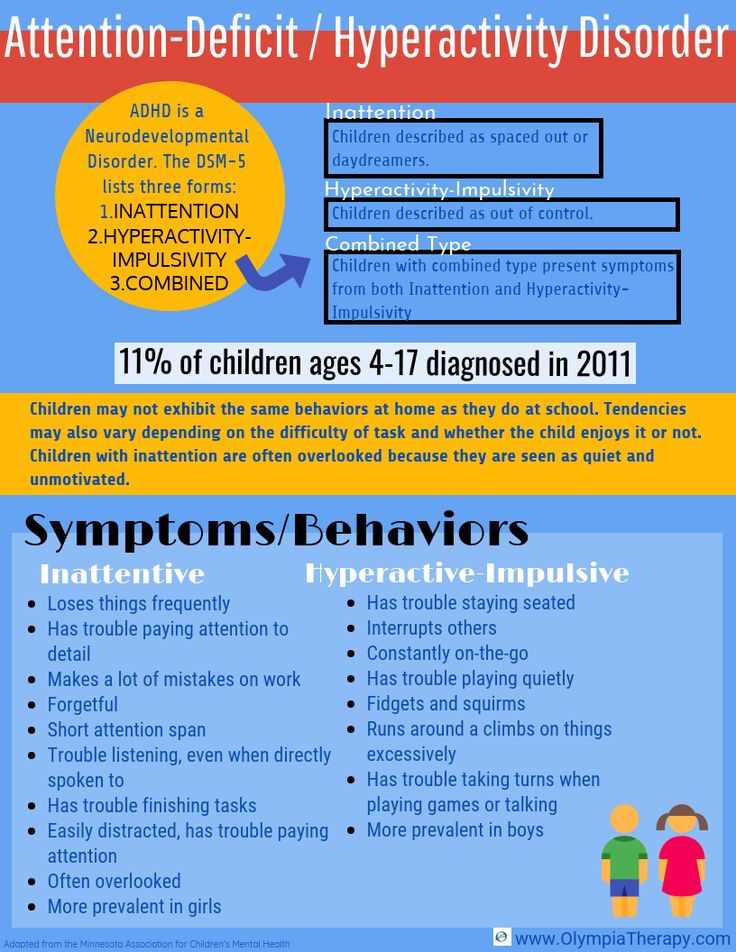

People with ADHD show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development:

- Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

- Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities.

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

- Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

- Often talks excessively.

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

- Often has trouble waiting their turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years.

- Several symptoms are present in two or more settings, (such as at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

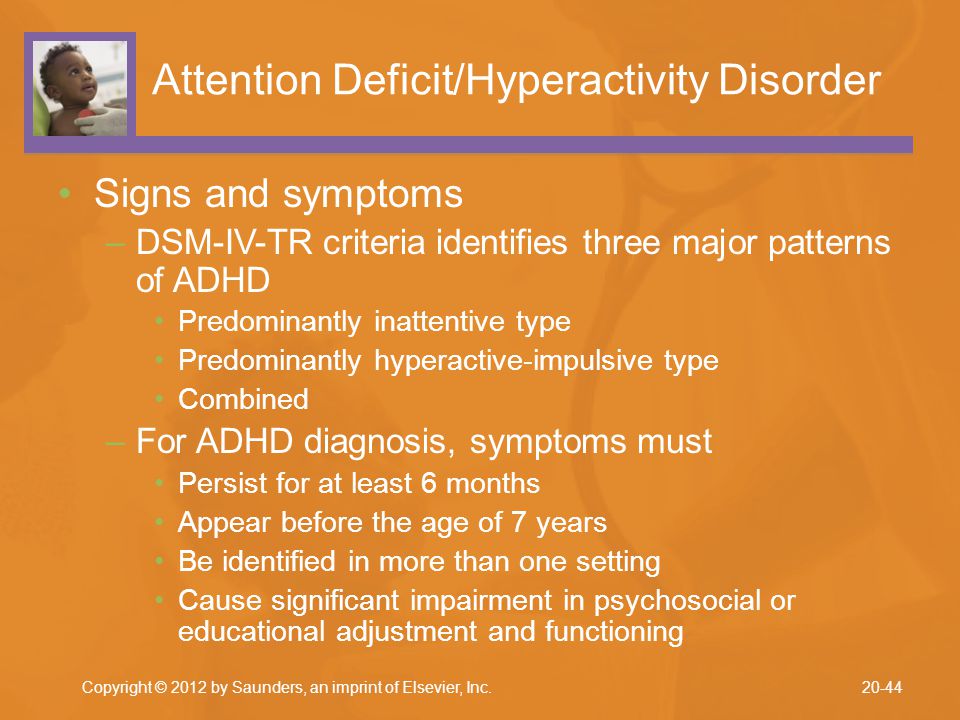

Based on the types of symptoms, three kinds (presentations) of ADHD can occur:

- Combined Presentation: if enough symptoms of both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past 6 months

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: if enough symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, were present for the past six months

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.

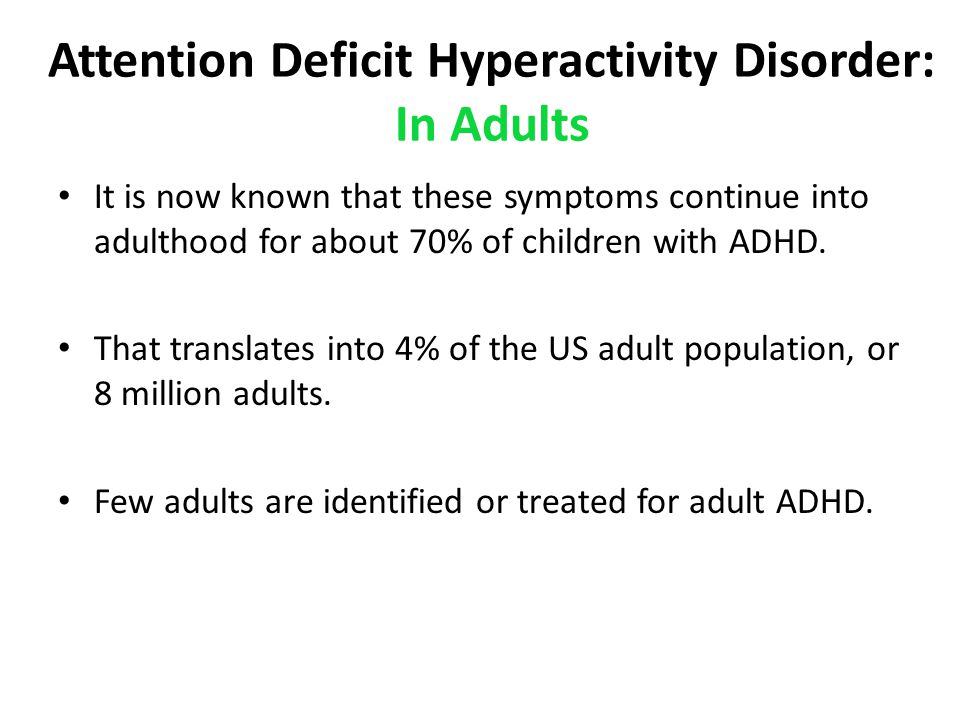

Diagnosing ADHD in Adults

ADHD often lasts into adulthood. To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

For more information about diagnosis and treatment throughout the lifespan, please visit the websites of the National Resource Center on ADHD and the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Reference

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Treatment of ADHD | CDC

Get information and support from the National Resource Center on ADHD

My Child Has Been Diagnosed with ADHD – Now What?

When a child is diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), parents often have concerns about which treatment is right for their child. ADHD can be managed with the right treatment. There are many treatment options, and what works best can depend on the individual child and family. To find the best options, it is recommended that parents work closely with others involved in their child’s life—healthcare providers, therapists, teachers, coaches, and other family members.

ADHD can be managed with the right treatment. There are many treatment options, and what works best can depend on the individual child and family. To find the best options, it is recommended that parents work closely with others involved in their child’s life—healthcare providers, therapists, teachers, coaches, and other family members.

Types of treatment for ADHD include

- Behavior therapy, including training for parents; and

- Medications.

Treatment recommendations for ADHD

For children with ADHD younger than 6 years of age, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends parent training in behavior management as the first line of treatment, before medication is tried. For children 6 years of age and older, the recommendations include medication and behavior therapy together — parent training in behavior management for children up to age 12 and other types of behavior therapy and training for adolescents. Schools can be part of the treatment as well. AAP recommendations also include adding behavioral classroom intervention and school supports. Learn more about how the school environment can be part of treatment.

AAP recommendations also include adding behavioral classroom intervention and school supports. Learn more about how the school environment can be part of treatment.

Good treatment plans will include close monitoring of whether and how much the treatment helps the child’s behavior, as well as making changes as needed along the way. To learn more about AAP recommendations for the treatment of children with ADHD, visit the Recommendations page.

Behavior Therapy, Including Training for Parents

ADHD affects not only a child’s ability to pay attention or sit still at school, it also affects relationships with family and other children. Children with ADHD often show behaviors that can be very disruptive to others. Behavior therapy is a treatment option that can help reduce these behaviors; it is often helpful to start behavior therapy as soon as a diagnosis is made.

The goals of behavior therapy are to learn or strengthen positive behaviors and eliminate unwanted or problem behaviors. Behavior therapy for ADHD can include

Behavior therapy for ADHD can include

- Parent training in behavior management;

- Behavior therapy with children; and

- Behavioral interventions in the classroom.

These approaches can also be used together. For children who attend early childhood programs, it is usually most effective if parents and educators work together to help the child.

Children younger than 6 years of age

For young children with ADHD, behavior therapy is an important first step before trying medication because:

- Parent training in behavior management gives parents the skills and strategies to help their child.

- Parent training in behavior management has been shown to work as well as medication for ADHD in young children.

- Young children have more side effects from ADHD medications than older children.

- The long-term effects of ADHD medications on young children have not been well-studied.

Behavior Therapy for Younger and Older Children with ADHD [PDF – 466 KB]

School-age children and adolescents

For children ages 6 years and older, AAP recommends combining medication treatment with behavior therapy. Several types of behavior therapies are effective, including:

Several types of behavior therapies are effective, including:

- Parent training in behavior management;

- Behavioral interventions in the classroom;

- Peer interventions that focus on behavior; and

- Organizational skills training.

These approaches are often most effective if they are used together, depending on the needs of the individual child and the family.

Learn more about behavior therapy

Learn more about ADHD treatment and support in school

Read about the evidence for effective therapies for ADHD

Top of Page

Medications

Medication can help children manage their ADHD symptoms in their everyday life and can help them control the behaviors that cause difficulties with family, friends, and at school.

Several different types of medications are FDA-approved to treat ADHD in children as young as 6 years of age:

- Stimulants are the best-known and most widely used ADHD medications.

Between 70-80% of children with ADHD have fewer ADHD symptoms when taking these fast-acting medications.

Between 70-80% of children with ADHD have fewer ADHD symptoms when taking these fast-acting medications. - Nonstimulants were approved for the treatment of ADHD in 2003. They do not work as quickly as stimulants, but their effect can last up to 24 hours.

Medications can affect children differently and can have side effects such as decreased appetite or sleep problems. One child may respond well to one medication, but not to another.

Healthcare providers who prescribe medication may need to try different medications and doses. The AAP recommends that healthcare providers observe and adjust the dose of medication to find the right balance between benefits and side effects. It is important for parents to work with their child’s healthcare providers to find the medication that works best for their child.

Top of Page

Parent Education and Support

CDC funds the National Resource Center on ADHD (NRC), a program of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). The NRC provides resources, information, and advice for parents on how to help their child. Learn more about the services of the NRC.

The NRC provides resources, information, and advice for parents on how to help their child. Learn more about the services of the NRC.

Tips for Parents

The following are suggestions that may help with your child’s behavior:

- Create a routine. Try to follow the same schedule every day, from wake-up time to bedtime.

- Get organized. Encourage your child to put schoolbags, clothing, and toys in the same place every day so that they will be less likely to lose them.

- Manage distractions. Turn off the TV, limit noise, and provide a clean workspace when your child is doing homework. Some children with ADHD learn well if they are moving or listening to background music. Watch your child and see what works.

- Limit choices. To help your child not feel overwhelmed or overstimulated, offer choices with only a few options. For example, have them choose between this outfit or that one, this meal or that one, or this toy or that one.

- Be clear and specific when you talk with your child. Let your child know you are listening by describing what you heard them say. Use clear, brief directions when they need to do something.

- Help your child plan. Break down complicated tasks into simpler, shorter steps. For long tasks, starting early and taking breaks may help limit stress.

- Use goals and praise or other rewards. Use a chart to list goals and track positive behaviors, then let your child know they have done well by telling them or by rewarding their efforts in other ways. Be sure the goals are realistic—small steps are important!

- Discipline effectively. Instead of scolding, yelling, or spanking, use effective directions, time-outs or removal of privileges as consequences for inappropriate behavior.

- Create positive opportunities. Children with ADHD may find certain situations stressful. Finding out and encouraging what your child does well—whether it’s school, sports, art, music, or play—can help create positive experiences.

- Provide a healthy lifestyle. Nutritious food, lots of physical activity, and sufficient sleep are important; they can help keep ADHD symptoms from getting worse.

Top of Page

ADHD in Adults

ADHD lasts into adulthood for at least one-third of children with ADHD1. Treatments for adults can include medication, psychotherapy, education or training, or a combination of treatments. For more information about diagnosis and treatment throughout the lifespan, please visit the websites of the National Resource Center on ADHD and the National Institutes of Mental Health

More information

For more information on treatments, please click one of the following links:

National Resource Center on ADHD

National Institute of Mental Health

Information for parents from the American Academy of Pediatrics

References:

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study.

Pediatrics 2013;131(4):637-644.

Pediatrics 2013;131(4):637-644.

Parents typically attend 8-16 sessions with a therapist and learn strategies to help their child. Sessions may involve groups or individual families.

- The therapist meets regularly with the family to monitor progress and provide support

- Between sessions, parents practice using the skills they’ve learned from the therapist

After therapy ends families continue to experience improved behavior and reduced stress.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children | Zinov'eva

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. DOI:

2. Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. [Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Defitsit vnimaniya s giperaktivnost'yu u detei [Deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity at children]. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. (In Russ.)]

Defitsit vnimaniya s giperaktivnost'yu u detei [Deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity at children]. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. (In Russ.)]

3. Zavadenko NN. Hyperactivity and attention deficit in childhood. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. [Zavadenko N.N. Giperaktivnost' i defitsit vnimaniya v detskom vozraste [Hyperactivity and deficiency of attention at children's age]. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. (In Russ.)]

4. Biederman J, Kwon A, Aleardi M, et al. Absence of gender effects on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings in nonreferred subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1083–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1083.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed.: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

6. Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Negativity of mismatch in evoked potentials of the brain in adolescents in the norm and with attention deficit upon presentation of acoustic stimuli of short duration. Russian Physiological Journal. THEM. Sechenov. 2003;33(7):671–5. [Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Mismatch negativity in evoked brain potentials in adolescents in normal conditions and attention deficit in response to presentation of short-duration acoustic stimuli. Rossiiskii fiziologicheskii zhurnal im. I.M. Sechenova = Neuroscience and behavioral physiology. 2003;33(7):671–5. (In Russ.)]

Russian Physiological Journal. THEM. Sechenov. 2003;33(7):671–5. [Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Mismatch negativity in evoked brain potentials in adolescents in normal conditions and attention deficit in response to presentation of short-duration acoustic stimuli. Rossiiskii fiziologicheskii zhurnal im. I.M. Sechenova = Neuroscience and behavioral physiology. 2003;33(7):671–5. (In Russ.)]

7. Becker SP, Langberg JM, Vaughn AJ, Epstein JN. Clinical utility of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale comorbidity screening scales. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(3):221–8. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318245615b.

8. Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigorieva NV. Neurophysiological study of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Siberian Bulletin of Psychiatry and Narcology. 2003;(1):47–51. [Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigor'eva NV. Neurophysiological research of a syndrome of deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity. Sibirskii vestnik psikhiatrii i narkologii. 2003;(1):47–51. (In Russ.)]

2003;(1):47–51. (In Russ.)]

9. Biederman J, Faraone S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237–48. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2.

10. Mick E, Faraone SV. Genetics of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(2):261–84, vii-viii. DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.011.

11. Haavik J, Blau N, Thö ny B. Mutations in human monoamine-related neurotransmitter pathway genes. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(7):891–902. DOI: 10.1002/humu.20700.

12. Schulz KP, Himelstein J, Halperin JM, Newcorn JH. Neurobiological models of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: a brief review of the empirical evidence. CNS spectra. 2000;5(6):34–44.

13. Arnsten AFT, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):211–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020. Epub 2011 Feb 2.

Epub 2011 Feb 2.

14. McNally MA, Crocetti D, Mahone EM, et al. Corpus callosum segment circumference is associated with response control in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Child Neurology. 2010;25(4):453–62. DOI: 10.1177/0883073809350221. Epub 2010 Feb 5.

15. Nakao T, Radua J, Rubia K, Mataix-Cols D. Gray matter volume abnormalities in ADHD: voxelbased meta-analysis exploring the effects of age and stimulant medication. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1154–63. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020281. Epub 2011 Aug 24.

16. Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ. Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(12):1361–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.011. Epub 2006 Sep 1.

17. Finger AB. Lectures on developmental neurology. Moscow: MEDpressinform; 2012. 376 p. [Pal'chik AB. Lektsii po nevrologii razvitiya [Lectures on development neurology]. Moscow: MEDprecsinform; 2012. 376 p. (In Russ.)]

Moscow: MEDprecsinform; 2012. 376 p. (In Russ.)]

18. Reddy DS. Neurosteroids: Endogenous role in the human brian and therapeutic potentials. Prog. Brain Res. 2010;186:113–137.

19. Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19649–54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707741104. Epub 2007 Nov 16.

20. Fair DA, Posner J, Nagel BJ, et al. Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychology. 2010;68(12):1084–91. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.003. Epub 2010 Aug 21.

21. Makris N, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Seidman LJ. Towards Conceptualizing a Neural Systems-Based Anatomy of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31(1–2):36–49. DOI: 10.1159/000207492. Epub 2009 Apr 17.

22. Kaplan RF, Stevens MC. A review of adult ADHD: a neuropsychological and neuroimaging perspective. CNS Spectrums. 2002;7(5):355–62.

CNS Spectrums. 2002;7(5):355–62.

23. Krause J. SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(4):611–25. DOI: 10.1586/14737175.8.4.611.

24. Zametkin A, Liebenauer L, Fitzgerald G, et al. Brain metabolism in teenagers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:333–40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170011002.

25. Arns M, Conners CK, Kraemer HC. A decade of EEG Theta/Beta ratio research in ADHD – a meta-analysis. J Atten Discord. 2013;17(5):374–83. DOI: 10.1177/1087054712460087. Epub 2012 Oct 19.

26. Anjana Y, Khaliq F, Vaney N. Event-related potentials study in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Funct Neurol. 2010;25(2):87–92.

27. Oades RD, Dittman-Balcar A, Schepker R, et al. Auditory event-related potentials (ERPs) and mismatch negativity (MMN) in healthy children and those with attention-deficit or tourettetic symptoms. Biol Psychol. 1996;43(2):163–85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7.

Biol Psychol. 1996;43(2):163–85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7.

28. Meisel V, Servera M, Garcia-Banda G, et al. Neurofeedback and standard pharmacological intervention in ADHD: a randomized controlled trial with six-month follow-up. Biol Psychol. 2013;94(1):12–21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.04.015.

29. Wilens T, Spencer T, Biederman J. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):456–63. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.043.

30. Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(3):328–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

31. Hammerness P, McCarthy K, Mancuso E, et al. Atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:215–26. Epub 2009Apr 8.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:215–26. Epub 2009Apr 8.

32. Sangal RB, Sangal JM. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: using P300 topography to choose optimal treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6(10):1429–37. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14737175.6.10.1429.

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Modern ideas about the etiology, pathogenesis, diagnostic criteria and approaches to the treatment of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder are presented. The necessity of strict adherence to the criteria for the diagnosis of the syndrome and a balanced approach to drug therapy is emphasized.

In recent years, great progress has been made in the study of one of the most urgent problems of neuropediatrics - attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. The urgency of the problem is determined by the high frequency of this syndrome in the child population and its great social significance. Children with Attention Deficit Disorder have normal or high intelligence, but tend to do poorly in school. In addition to learning difficulties, attention deficit disorder is manifested by motor hyperactivity, attention defects, distractibility, impulsive behavior, and problems in relationships with others. It should be noted that attention deficit disorder is observed in both children and adults. In recent years, its genetic nature has been proven. It is quite obvious that the interests of various specialists - pediatricians, teachers, neuropsychologists, speech pathologists, neurologists - are concentrated in the focus of scientific problems of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In addition to learning difficulties, attention deficit disorder is manifested by motor hyperactivity, attention defects, distractibility, impulsive behavior, and problems in relationships with others. It should be noted that attention deficit disorder is observed in both children and adults. In recent years, its genetic nature has been proven. It is quite obvious that the interests of various specialists - pediatricians, teachers, neuropsychologists, speech pathologists, neurologists - are concentrated in the focus of scientific problems of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

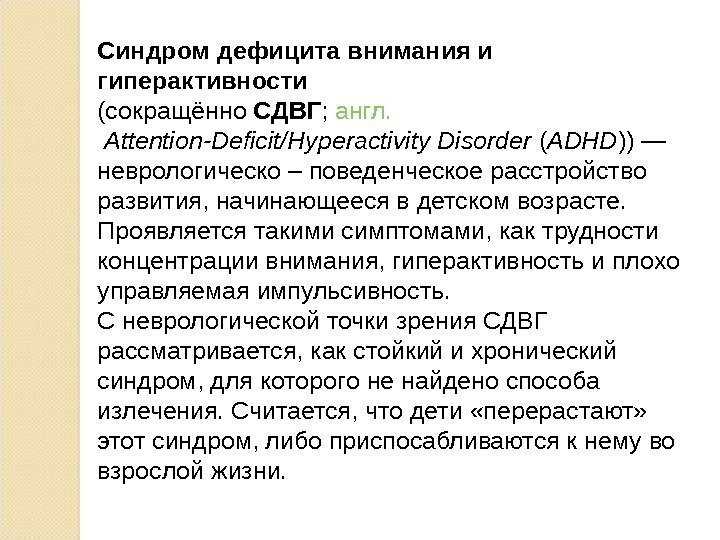

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is a dysfunction of the central nervous system (mainly the reticular formation of the brain), manifested by difficulties in concentrating and maintaining attention, learning and memory disorders, as well as difficulties in processing exogenous and endogenous information and stimuli.

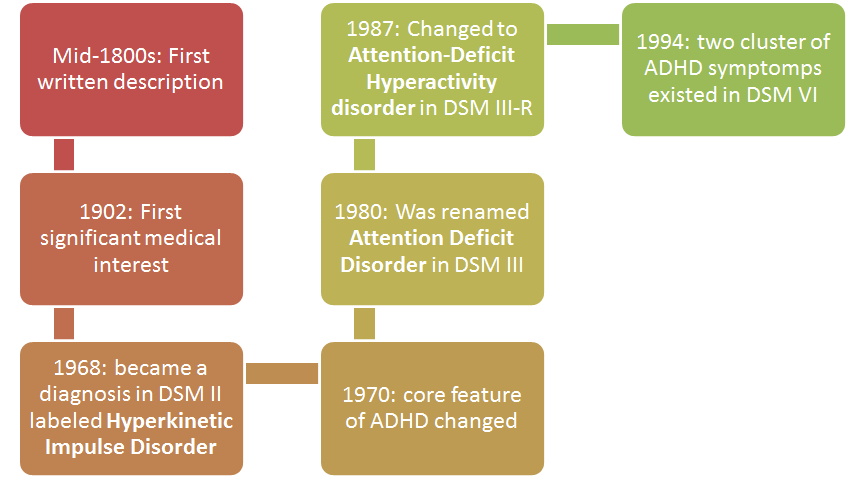

The term "attention deficit disorder" was isolated in the early 80s from the broader concept of "minimal brain dysfunction". The history of the study of minimal brain dysfunction is associated with the studies of E. Kahn et al. (1934), although separate studies have been carried out earlier. Observing school-age children with such behavioral disorders as motor disinhibition, distractibility, impulsive behavior, the authors suggested that the cause of these changes is brain damage of unknown etiology, and proposed the term "minimal brain damage". Later, learning disorders (difficulties and specific impairments in learning writing, reading, counting skills; disorders of perception and speech) were included in the concept of "minimal brain damage". Subsequently, the static "minimal brain damage" model gave way to a more dynamic and more flexible "minimal brain dysfunction" model.

In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association developed a working classification - DSM-IV (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition), according to which cases previously described as minimal brain dysfunction were proposed to be considered as deficiency syndrome attention and hyperactivity disorder. The underlying premise was that the most common and significant clinical symptoms of minimal brain dysfunction included impaired attention and hyperactivity. In the latest DSM-IV classification, these syndromes are grouped under one name "attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". In the ICD-10, the syndrome is covered under "Emotional and behavioral disorders usually onset in childhood and adolescence" in the subsection "Impaired activity and attention" (F90.0) and "Hyperkinetic conduct disorder" (F90.1).

The underlying premise was that the most common and significant clinical symptoms of minimal brain dysfunction included impaired attention and hyperactivity. In the latest DSM-IV classification, these syndromes are grouped under one name "attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder". In the ICD-10, the syndrome is covered under "Emotional and behavioral disorders usually onset in childhood and adolescence" in the subsection "Impaired activity and attention" (F90.0) and "Hyperkinetic conduct disorder" (F90.1).

The frequency of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, according to different authors, varies from 2.2 to 18% in school-age children. Such differences are explained by non-compliance with clear criteria for diagnosis. According to the American Psychiatric Association, about 5% of school-age children suffer from ADHD. Almost every school class has at least one child with this disease. In the study of N.N. Zavodenko et al. [1], the frequency of attention deficit disorder in schoolchildren was 7. 6%. Boys are affected twice as often as girls.

6%. Boys are affected twice as often as girls.

Classification. According to DSM-IV, 3 variants of the course of attention deficit / hyperactivity disorder are distinguished depending on the prevailing clinical symptoms:

- a syndrome that combines attention deficit and hyperactivity;

- attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity;

- hyperactivity disorder without attention deficit.

Some researchers question the association of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperactivity disorder, since up to 40% of all patients suffer from only attention deficit without hyperactivity. Attention deficit without hyperactivity disorder is more common in girls.

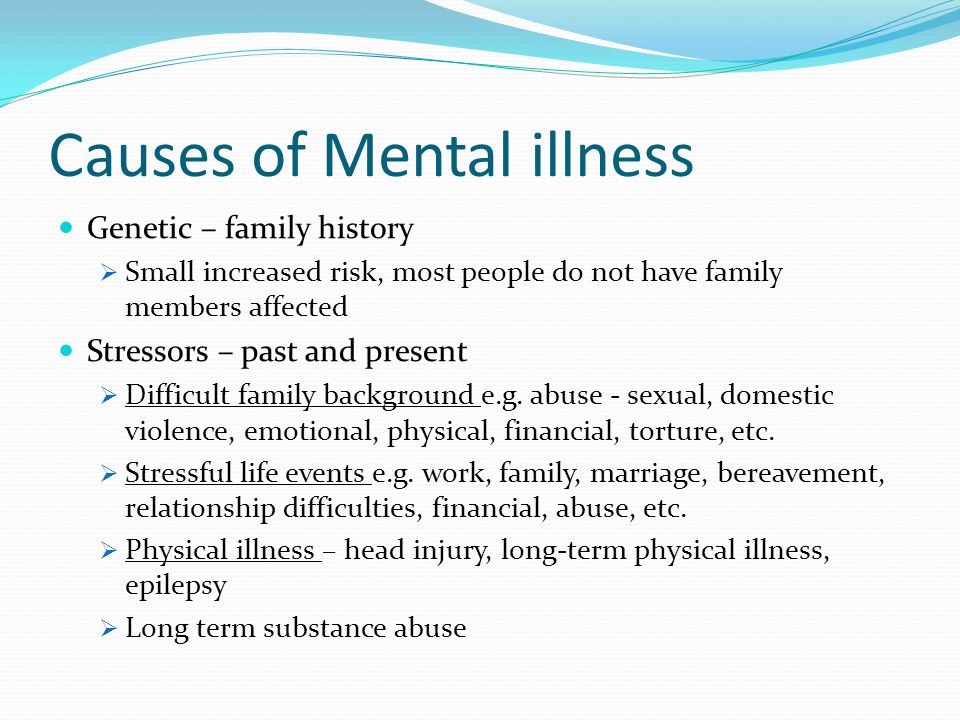

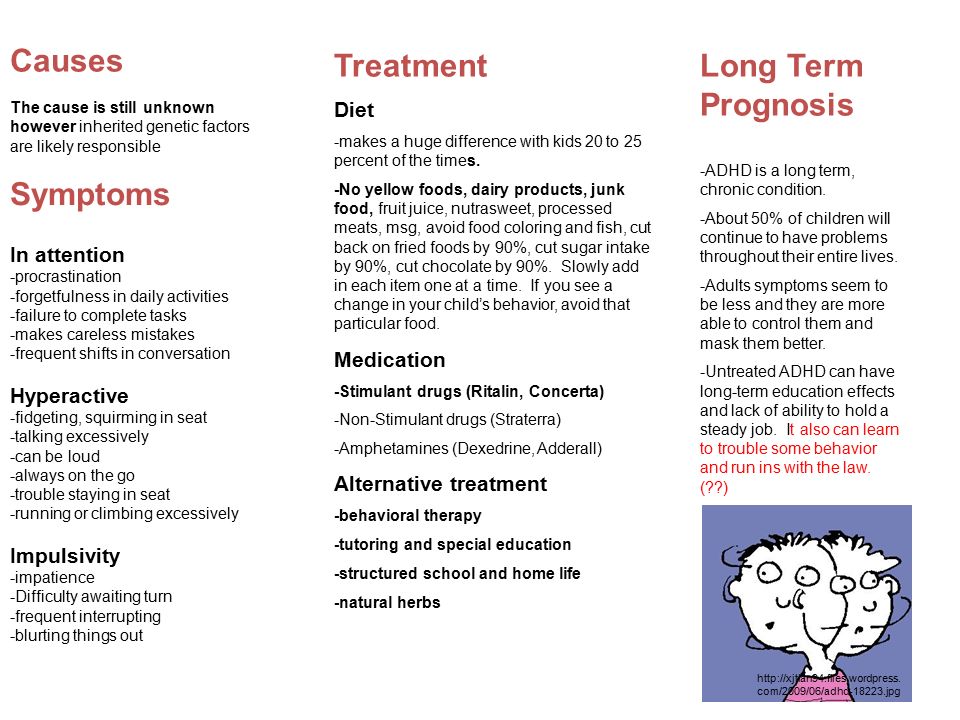

Attention deficit disorder can be both primary and result from other diseases, that is, it can be secondary or symptomatic (genetically determined syndromes, mental illness, consequences of perinatal and infectious lesions of the central nervous system).

The etiology is not well understood. Most researchers suggest the genetic nature of the syndrome. Families of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder often have close relatives who had similar disorders at school age [2]. To identify hereditary burden, a long and detailed questioning is necessary, since the difficulties of learning at school by adults are consciously or unconsciously "amnesiac". Pedigrees of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder also often show a burden of obsessive-compulsive disorder (obsessive thoughts and compulsive rituals), tics, and Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome. Probably, there is a genetically determined relationship of neurotransmitter disorders in the brain in these pathological conditions.

It is assumed that attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is determined by mutations in 3 genes that regulate dopamine metabolism - the D4 receptor gene, the D2 receptor gene, and the gene responsible for dopamine transport [3]. S. Faraone, J. Biederman [3] discusses the hypothesis that the carriers of the mutant gene are children with the most pronounced hyperactivity.

S. Faraone, J. Biederman [3] discusses the hypothesis that the carriers of the mutant gene are children with the most pronounced hyperactivity.

Along with genetic factors, family, pre- and perinatal risk factors for the development of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder are distinguished. Family factors include the low social status of the family, the presence of a criminal environment, severe disagreements between parents. Neuropsychiatric disorders, alcoholism and deviations in sexual behavior in the mother are considered especially significant [2]. Pre- and perinatal risk factors for the development of attention deficit disorder include neonatal asphyxia, maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy, certain drugs, and smoking.

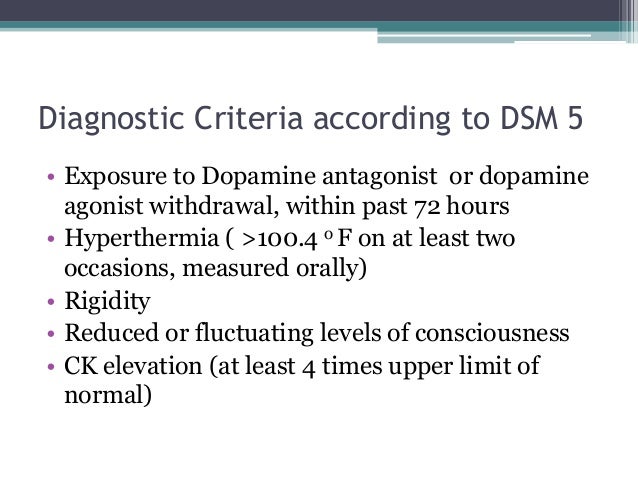

It is assumed that the pathogenesis of the syndrome is based on disturbances in the activating system of the reticular formation, which contributes to the coordination of learning and memory, the processing of incoming information and the spontaneous maintenance of attention. Violations of the activating function of the reticular formation, apparently, are associated with a lack of norepinephrine in it [3]. The impossibility of adequate processing of information leads to the fact that various visual, sound, emotional stimuli become redundant for the child, causing anxiety, irritation and aggressiveness. Violations in the functioning of the reticular formation predetermine secondary disorders of the neurotransmitter metabolism of the brain. The theory of the relationship of hyperactivity with dopamine metabolism disorders has numerous confirmations, in particular, the success of the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with dopaminergic drugs. It is possible that disorders of neurotransmitter metabolism leading to hyperactivity are associated with mutations in genes that regulate the functions of dopamine receptors. Separate biochemical studies in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder indicate that the metabolism of not only dopamine, but also other neurotransmitters, serotonin and noradrenaline, is disturbed in the brain.

Violations of the activating function of the reticular formation, apparently, are associated with a lack of norepinephrine in it [3]. The impossibility of adequate processing of information leads to the fact that various visual, sound, emotional stimuli become redundant for the child, causing anxiety, irritation and aggressiveness. Violations in the functioning of the reticular formation predetermine secondary disorders of the neurotransmitter metabolism of the brain. The theory of the relationship of hyperactivity with dopamine metabolism disorders has numerous confirmations, in particular, the success of the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder with dopaminergic drugs. It is possible that disorders of neurotransmitter metabolism leading to hyperactivity are associated with mutations in genes that regulate the functions of dopamine receptors. Separate biochemical studies in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder indicate that the metabolism of not only dopamine, but also other neurotransmitters, serotonin and noradrenaline, is disturbed in the brain.

In addition to the reticular formation, dysfunction of the frontal lobes (prefrontal cortex), subcortical nuclei, and pathways connecting them is likely to be important in the pathogenesis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder [4]. One of the confirmations of this assumption is the similarity of neuropsychological disorders in children with attention deficit disorder and in adults with damage to the frontal lobes of the brain. Spectral tomography of the brain revealed a decrease in blood flow in the prefrontal cortex of the brain during intellectual loads in 65% of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, while in the control group it was only in 5% [4].

Criteria for diagnosis and clinical manifestations. Adequate diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is impossible without strict adherence to the diagnostic criteria. These, according to DSM-IV, include:

- the child has an attention deficit and / or hyperactivity disorder;

- early (up to 7 years) onset of symptoms and duration (more than 6 months) of their existence;

- some symptoms occur both at home and at school;

- symptoms are not manifestations of other diseases;

- violation of learning and social functions.

It should be noted that the presence of learning and social dysfunctions is a necessary criterion for the diagnosis of "Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". In addition, the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder can only be made when learning difficulties are evident (i.e., not earlier than 5-6 years of age).

According to the DSM-IV, a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder can be made if at least 6 of the symptoms described below are present. A child has an attention deficit if he:

- does not pay attention to details and makes mistakes in work;

- hardly maintains attention in work and play;

- does not listen to what is said to him;

- unable to follow instructions;

- unable to organize a game or activity;

- has difficulty performing tasks that require prolonged concentration of attention;

- often loses things;

- often and easily distracted;

- sometimes forgetful.

Diagnosis of hyperactivity requires at least 5 of the following symptoms. The child is hyperactive if he:

- makes fussy movements with arms and legs;

- often jumps up from his seat;

- hypermobile in situations where hypermobility is unacceptable;

- cannot play silent games;

- always in motion;

- says a lot.

A child is impulsive (i.e. unable to stop and think before speaking or acting) if they:

- answers a question without listening to it;

- cannot wait for his turn;

- interferes in the conversations and games of others.

In a significant percentage of cases, the clinical manifestations of the syndrome occur before the age of 5-6 years, and sometimes already in the 1st year of life. Children of the 1st year of life, who subsequently develop hyperactivity, often suffer from sleep disorders and hyperexcitability. In the future, they become extremely naughty and hyperactive, their behavior is hardly controlled by their parents. At the same time, children who later have attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity may moderately lag behind in motor (they begin to roll over, crawl, walk 1-2 months later) and speech development in infancy, they are inert, passive, not very emotional. As the child grows, attentional disturbances become apparent, which parents usually do not pay attention to at first.

In the future, they become extremely naughty and hyperactive, their behavior is hardly controlled by their parents. At the same time, children who later have attention deficit disorder without hyperactivity may moderately lag behind in motor (they begin to roll over, crawl, walk 1-2 months later) and speech development in infancy, they are inert, passive, not very emotional. As the child grows, attentional disturbances become apparent, which parents usually do not pay attention to at first.

Impaired attention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity phenomena lead to the fact that a school-age child with normal or high intelligence has impaired reading and writing skills, does not cope with school assignments, makes many mistakes in completed work and is not inclined to listen to adult advice. The child is a source of constant anxiety for others (parents, teachers, peers), as he interferes in other people's conversations and activities, takes other people's things, often behaves completely unpredictably, overreacts to external stimuli (the reaction does not correspond to the situation). Such children hardly adapt in the team, their distinct desire for leadership has no actual reinforcement. Due to their impatience and impulsiveness, they often come into conflict with peers and teachers, which exacerbates existing learning disabilities. The child is also unable to foresee the consequences of his behavior, does not recognize authorities, which can lead to antisocial acts. Especially often, antisocial behavior is observed in adolescence, when children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder have an increased risk of developing persistent behavioral disorders and aggressiveness. Adolescents with this pathology are more likely to start smoking early and take narcotic drugs [5], they are more likely to experience traumatic brain injuries [6]. Parents of a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are sometimes moody and impulsive themselves. Outbursts of rage, aggressive actions, and a child's stubborn refusal to behave in accordance with parental rules can lead to an uncontrollable reaction from the parents and to physical abuse.

Such children hardly adapt in the team, their distinct desire for leadership has no actual reinforcement. Due to their impatience and impulsiveness, they often come into conflict with peers and teachers, which exacerbates existing learning disabilities. The child is also unable to foresee the consequences of his behavior, does not recognize authorities, which can lead to antisocial acts. Especially often, antisocial behavior is observed in adolescence, when children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder have an increased risk of developing persistent behavioral disorders and aggressiveness. Adolescents with this pathology are more likely to start smoking early and take narcotic drugs [5], they are more likely to experience traumatic brain injuries [6]. Parents of a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are sometimes moody and impulsive themselves. Outbursts of rage, aggressive actions, and a child's stubborn refusal to behave in accordance with parental rules can lead to an uncontrollable reaction from the parents and to physical abuse.

On neurological examination of a child with attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity, focal neurological symptoms are usually absent. There may be a lack of fine motor skills, impaired reciprocal coordination of movements and moderate ataxia. More often than in the general child population, speech disorders are observed [7].

Differential diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder should be carried out with specific learning disorders (dyscalculia, dyslexia, etc.), asthenic syndromes against the background of intercurrent diseases, thyroid diseases, mild mental retardation and schizophrenia. Differential diagnosis is often difficult, since attention deficit disorder can be combined with a number of other diseases and conditions, most often with psychiatric pathology (depression, panic attacks, obsessive thoughts, etc.) [8].

The system of treatment and monitoring of children with attention deficit has not been developed enough, due to the unclear pathogenesis of the disease. There are non-drug and drug methods of correction.

There are non-drug and drug methods of correction.

Non-pharmacological correction includes methods of behavior modification, psychotherapy, pedagogical and neuropsychological correction. The child is recommended a sparing mode of learning - the minimum number of children in the class (ideally no more than 12 people), a shorter duration of classes (up to 30 minutes), the child's stay in the first desk (eye contact between the teacher and the child improves concentration). From the point of view of social adaptation, it is also important to purposefully and long-term education of socially encouraged norms of behavior in a child, since the behavior of some children has features of antisocial [9]. Psychotherapeutic work is needed with parents so that they do not regard the child's behavior as "hooligan" and show more understanding and patience in their educational activities. Parents should monitor the observance of the day regimen of a "hyperactive" child (meal time, homework, sleep), provide him with the opportunity to expend excess energy in physical exercises, long walks, running. Fatigue while performing tasks should also be avoided, as this may increase hyperactivity. "Hyperactive" children are extremely excitable, so it is necessary to exclude or limit their participation in activities associated with the accumulation of a large number of people. Since the child has difficulty concentrating, you need to give him only one task for a certain period of time. The choice of partners for games is important - the child's friends should be balanced and calm.

Fatigue while performing tasks should also be avoided, as this may increase hyperactivity. "Hyperactive" children are extremely excitable, so it is necessary to exclude or limit their participation in activities associated with the accumulation of a large number of people. Since the child has difficulty concentrating, you need to give him only one task for a certain period of time. The choice of partners for games is important - the child's friends should be balanced and calm.

Drug therapy for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder is appropriate when non-drug methods of correction are ineffective. Psychostimulants, tricyclic antidepressants, tranquilizers and nootropic drugs are used. In international pediatric neurological practice, the effectiveness of two drugs has been empirically established - the antidepressant amitriptyline and Ritalin, which belongs to the amphetamine group.

Methylphenidate (Ritalin, Centedrin, Meredil) is the first line drug of choice in the treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The positive effect of methylphenidate is observed in 70-80% of children. The drug is administered once in the morning at a dose of 10 mg (1 tablet), but the daily dose can reach 6 mg/kg. The therapeutic effect occurs quickly - during the first days of admission. Despite the high efficacy of methylphenidate, there are limitations and contraindications to its use associated with frequent side effects. The latter include growth retardation, irritability, sleep disturbance, loss of appetite and body weight, provocation of tics, dyspeptic disorders, dry mouth and dizziness. The drug may develop addiction. Contraindications to taking the drug are the child's age less than 6 years, pronounced states of anxiety and agitation, as well as the presence of a family history of tics and Tourette's syndrome. Unfortunately, methylphenidate is not available on the Russian pharmaceutical market. In domestic pediatric practice, the drug amitriptyline, which has fewer side effects, is more widely used. Amitriptyline is prescribed for children under 7 years old at a dose of 25 mg / day, for children over 7 years old - at a dose of 25-50 mg / day.

The positive effect of methylphenidate is observed in 70-80% of children. The drug is administered once in the morning at a dose of 10 mg (1 tablet), but the daily dose can reach 6 mg/kg. The therapeutic effect occurs quickly - during the first days of admission. Despite the high efficacy of methylphenidate, there are limitations and contraindications to its use associated with frequent side effects. The latter include growth retardation, irritability, sleep disturbance, loss of appetite and body weight, provocation of tics, dyspeptic disorders, dry mouth and dizziness. The drug may develop addiction. Contraindications to taking the drug are the child's age less than 6 years, pronounced states of anxiety and agitation, as well as the presence of a family history of tics and Tourette's syndrome. Unfortunately, methylphenidate is not available on the Russian pharmaceutical market. In domestic pediatric practice, the drug amitriptyline, which has fewer side effects, is more widely used. Amitriptyline is prescribed for children under 7 years old at a dose of 25 mg / day, for children over 7 years old - at a dose of 25-50 mg / day. The initial dose of the drug is 1/4 tablet and increases gradually over 7-10 days. The effectiveness of amitriptyline in the treatment of children with attention deficit disorder is 60%.

The initial dose of the drug is 1/4 tablet and increases gradually over 7-10 days. The effectiveness of amitriptyline in the treatment of children with attention deficit disorder is 60%.

Single domestic studies also prove the effectiveness of the use of nootropic drugs (nootropil, piracetam and instenon) in the treatment of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. N.N. Zavodenko et al. observed a positive effect of instenon in 59% of patients [1]. Instenon was administered at a dose of 1.5 tablets per day to children aged 7-10 years for 1 month. There was an improvement in the characteristics of behavior, motor skills, attention and memory.

The greatest effect in the treatment of ADHD is achieved by combining various methods of psychological work (both with the child himself and with his parents) and drug therapy [10].

The prognosis is relatively good, as a significant proportion of children have symptoms that disappear during adolescence. Gradually, as the child grows, disturbances in the neurotransmitter system of the brain are compensated, and some of the symptoms regress. However, in 30-70% of cases, clinical manifestations of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (excessive impulsivity, irascibility, absent-mindedness, forgetfulness, restlessness, impatience, unpredictable, rapid and frequent mood changes) can also be observed in adults. The factors of an unfavorable prognosis of the syndrome are its combination with mental illness, the presence of psychopathology in the mother, as well as symptoms of impulsivity in the patient himself [11]. Social adaptation of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder can only be achieved with the interest and cooperation of the family, school and society.

Gradually, as the child grows, disturbances in the neurotransmitter system of the brain are compensated, and some of the symptoms regress. However, in 30-70% of cases, clinical manifestations of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (excessive impulsivity, irascibility, absent-mindedness, forgetfulness, restlessness, impatience, unpredictable, rapid and frequent mood changes) can also be observed in adults. The factors of an unfavorable prognosis of the syndrome are its combination with mental illness, the presence of psychopathology in the mother, as well as symptoms of impulsivity in the patient himself [11]. Social adaptation of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder can only be achieved with the interest and cooperation of the family, school and society.

Russian Bulletin of Perinatology and Pediatrics, N3-2000, p.39-42

Literature

1. Zavodenko H.H., Petrukhin A.S., Semenov P.A. Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Various Methods of Pharmacotherapy. Moscow Medical Journal 1998; 19-23.

Moscow Medical Journal 1998; 19-23.

2. Weinstein C.S., Apfel R.J., Weinstein S.R. Description of mothers with ADHD with children with ADHD. Psychiatry 1998; 61:1:12-19.

3. Faraone S.V., Biederman J. Neurobiology of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44:10:951-958.

4. Amen D.G., Carmichael B.D. High-resolution brain SPECT imaging in ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1997; 9:2:81-86.

5. Willens T.E., Biedermann J., Mick E. et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in association with early onset substance use disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997; 185:8:475-482.

6. Di Scale C., Lescohier I., Barthel M., Li G. Ingures to children with ADHD. Pediatrics 1998; 102:6:1415-1421.

7. Purvis K.L., Tannock R. Language abilities in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, reading disabilities, and normal controls. J Abnorm Child Psychol 1997; 25:2:133-144.