Mental disorder questions

Frequently asked questions about mental health

Mental health questions

-

Q. What is mental health?

We all have mental health which is made up of our beliefs, thoughts, feelings and behaviours.

-

Q. What do I do if the support doesn’t help?

It can be difficult to find the things that will help you, as different things help different people. It’s important to be open to a range of approaches and to be committed to finding the right help and to continue to be hopeful, even when some things don’t work out.

-

Q.

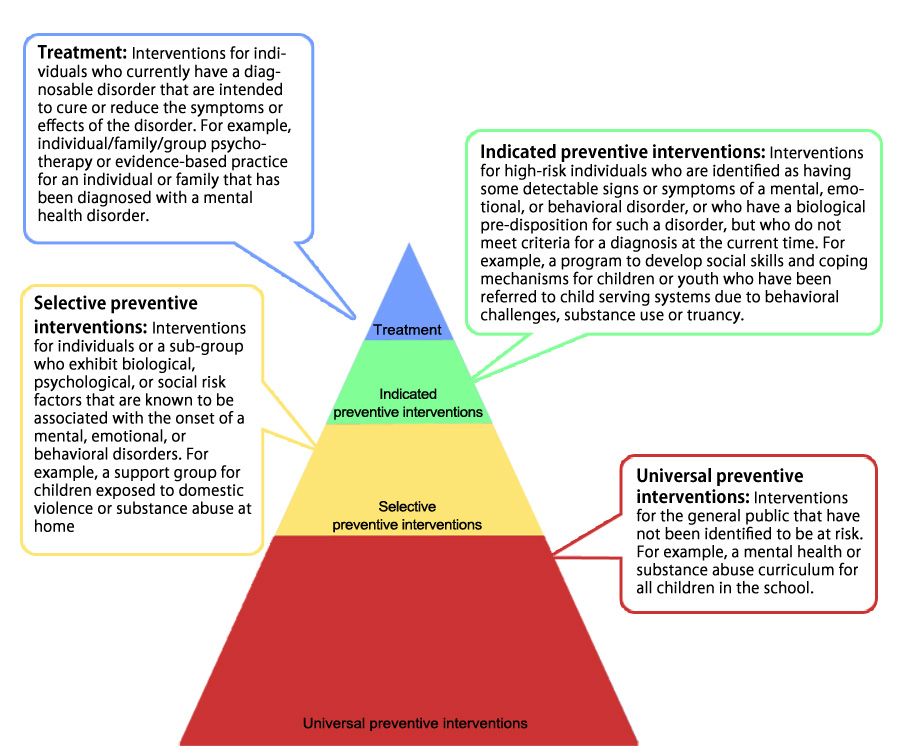

Can you prevent mental health problems?

We can all suffer from mental health challenges, but developing our wellbeing, resilience, and seeking help early can help prevent challenges becoming serious.

-

Q. Are there cures for mental health problems?

It is often more realistic and helpful to find out what helps with the issues you face. Talking, counselling, medication, friendships, exercise, good sleep and nutrition, and meaningful occupation can all help.

-

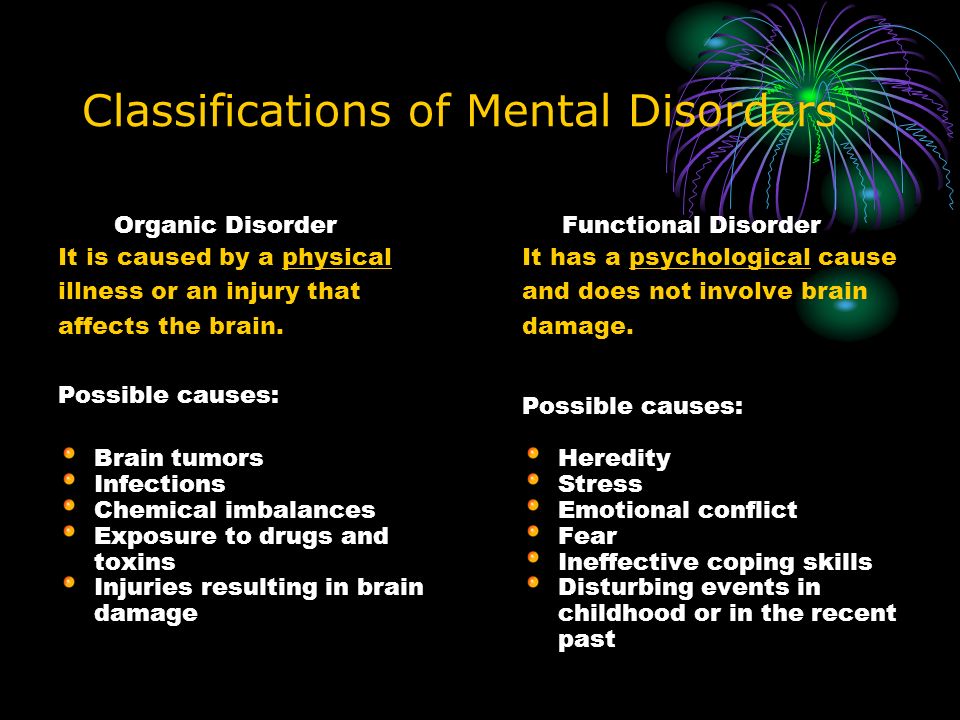

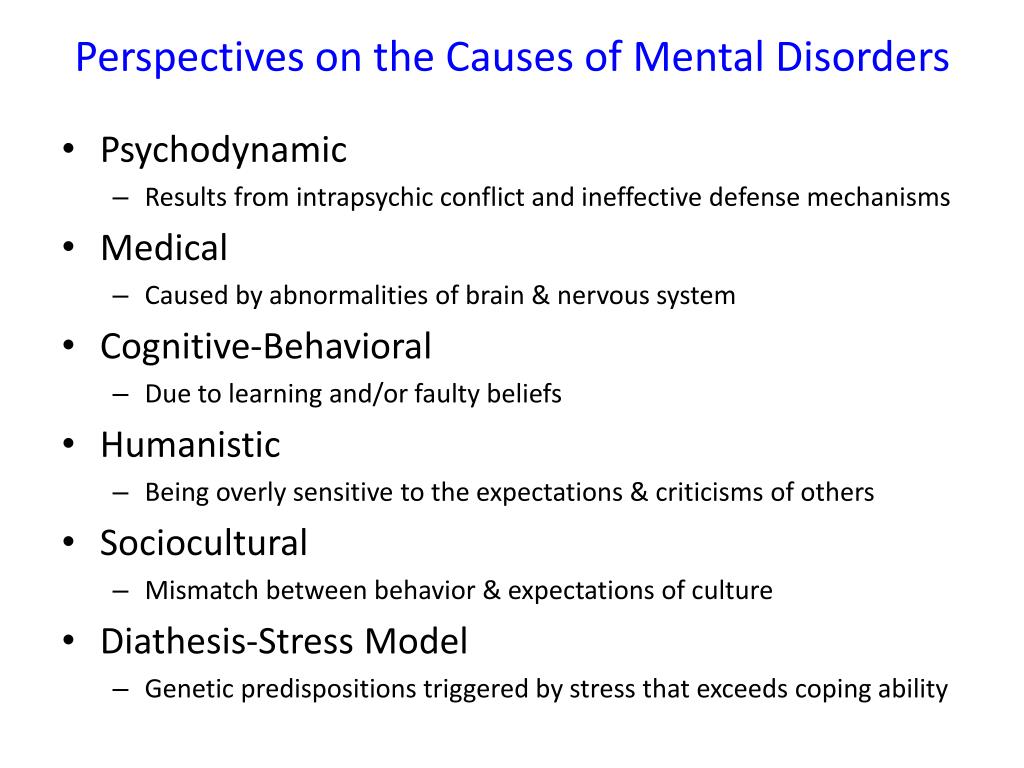

Q. What causes mental health problems?

Challenges or problems with your mental health can arise from psychological, biological, and social, issues, as well as life events.

-

Q. What do I do if I’m worried about my mental health?

The most important thing is to talk to someone you trust. This might be a friend, colleague, family member, or GP. In addition to talking to someone, it may be useful to find out more information about what you are experiencing. These things may help to get some perspective on what you are experiencing, and be the start of getting help.

-

Q. How do I know if I’m unwell?

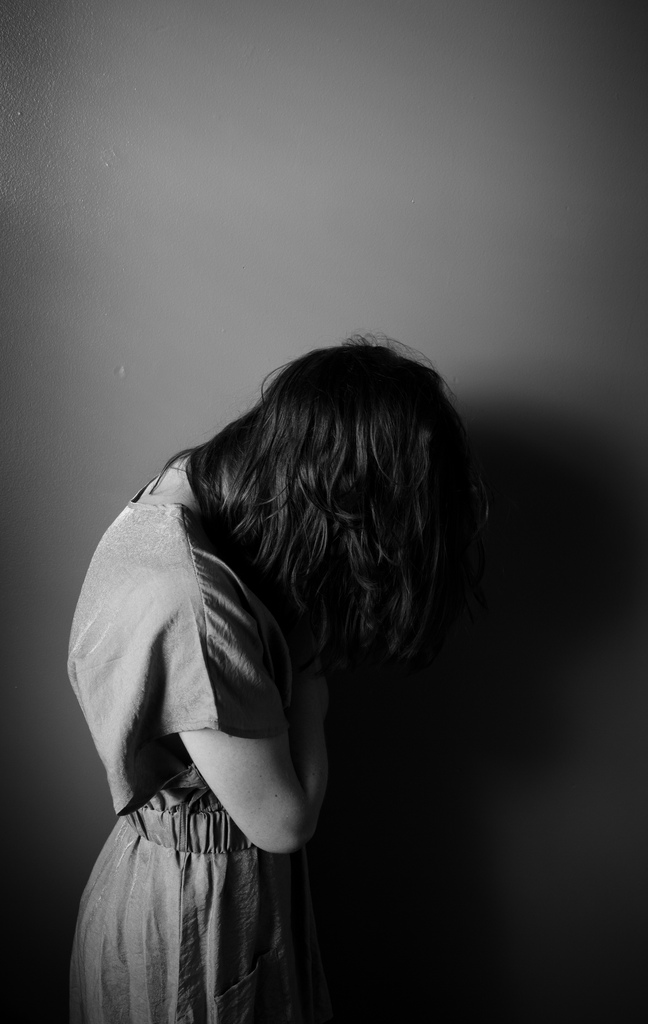

If your beliefs , thoughts , feelings or behaviours have a significant impact on your ability to function in what might be considered a normal or ordinary way, it would be important to seek help.

-

Q. What should I do if I’m worried about a friend or relative?

This may depend on your relationship with them. Gently encouraging someone to seek appropriate support would be helpful to start with.

-

Q. How do I deal with someone telling me what to do?

Some people may advise you on good evidence of what works with the best of intentions, but it’s important to find out what works best for you.

Stay in touch

Would you like to receive updates related to our service? Simple! Enter your e-mail address in the field below to subscribe. ..

..

In Partnership with...

72 Mental Health Questions for Counselors and Patients

What does “mental health” mean to you?

Is it the same as happiness?

Or is it simply the absence of mental illness?

Whether you are a professional therapist or want to help a friend in need, it helps to have some mental health questions up your sleeve.

You may not be able to diagnose someone who isn’t doing 100%, but with a little insight into their state of mind, you can play a valuable role in supporting them to get the help they need.

In this article, we’ll cover some mental health questions to ask yourself, your clients, or even your students. Read on to learn more.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Are Mental Health Questions?

- Mental Health Questions

- 5 Examples of Common Mental Health Questions for Risk Assessment and Evaluation

- 20 Mental Health Interview Questions a Counselor Should Ask

- 10 Mental Health Questions Aimed at Students

- 7 Questions for Group Discussion

- Common Mental Health Research Questions

- 9 Mental Health Questions a Patient Can Ask

- 12 Questions to Ask Yourself

- 9 Self-Reflection Questions

- A Take-Home Message

- References

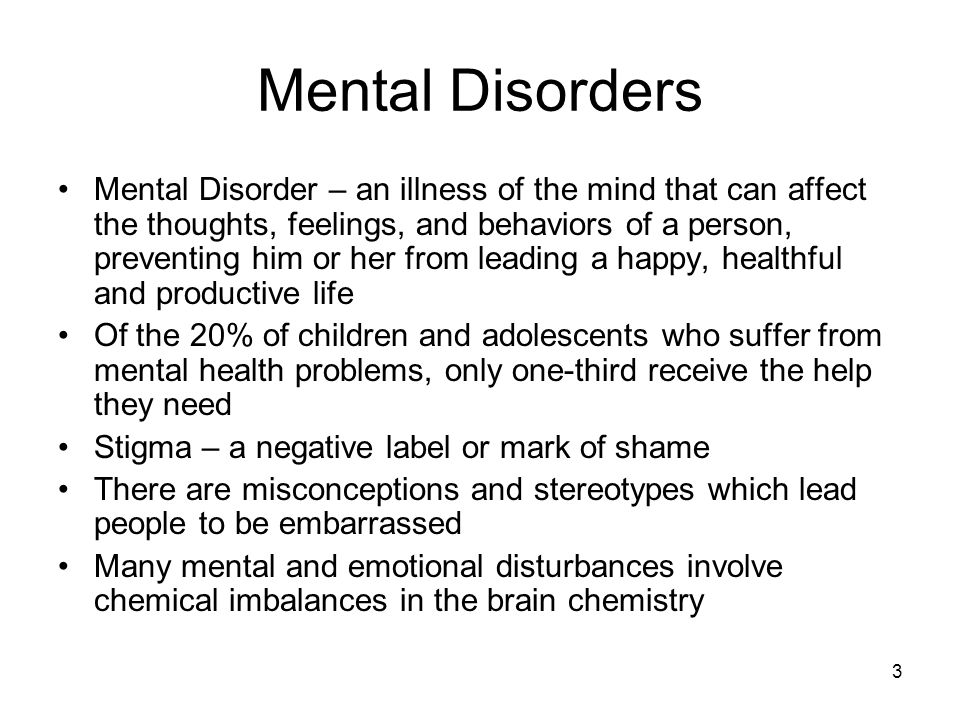

What Are Mental Health Questions?

Let’s start with a definition of mental health – more precisely, what it isn’t. In the article The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing, positive psychologist Corey Keyes (2002) is very adamant about not oversimplifying the mental health concept, writing:

“mental health is more than the presence and absence of emotional states.

”

Recapping the definition of a syndrome from the clinical literature, he then reminds us of the following:

“[a syndrome is] … a set of symptoms that occur together.”

Finally, Keyes argues that we can challenge the idea that syndromes are all about suffering. Instead, he argues that can we view mental health as:

“a syndrome of symptoms of an individual’s subjective well-being” or “a syndrome of symptoms of positive feelings and positive functioning in life.”

Mental Health Questions

The right questions can give you insight into others’ wellbeing and promote the benefits of mental health.

These questions also help you:

- Show your concern for someone who is struggling

- Open up a dialogue about their mental state

- Trigger them to reflect on their overall wellbeing

- Prompt or encourage them to seek professional help if it is necessary

To get a clearer idea of these questions, let’s consider some examples.

5 Examples of Common Mental Health Questions for Risk Assessment and Evaluation

Where do you take a mental health conversation once you’ve opened with, “How are you feeling?”

For professionals, it might help to screen your client for any disorders or distress. The Anxiety and Depression Detector (Means-Christensen, Sherbourne, Roy-Byrne, Craske, & Stein, 2006) can help you assess depression and anxiety disorders, and it’s only five questions long (O’Donnell, Bryant, Creamer, & Carty, 2008).

You may want to tweak some of these questions to make them more relevant to your client.

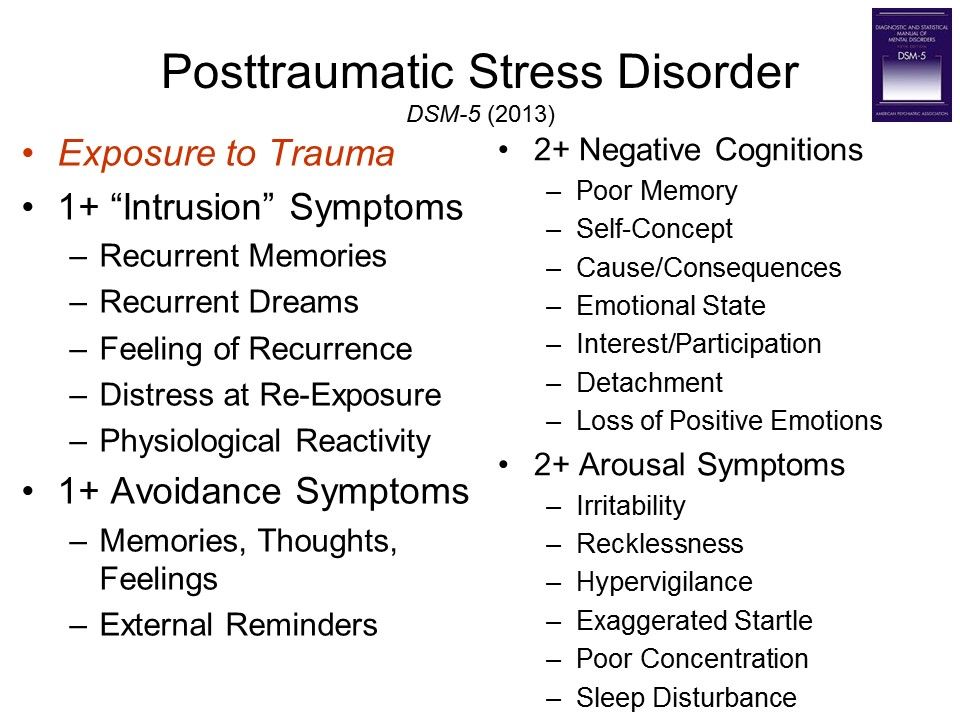

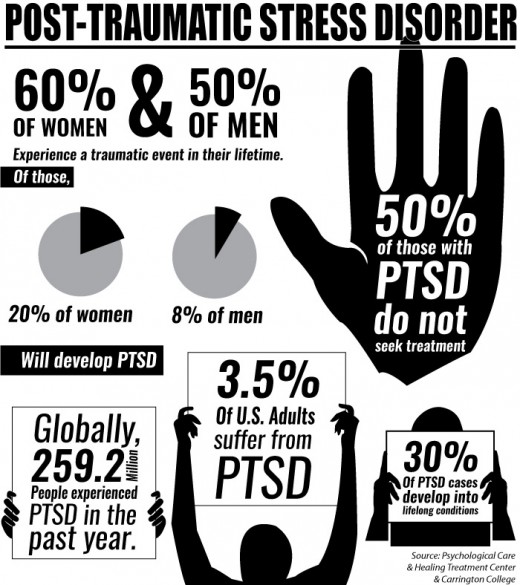

- Have you ever experienced a terrible occurrence that has impacted you significantly? Examples may include being the victim of armed assault, witnessing a tragedy happen to someone else, surviving a sexual assault, or living through a natural disaster.

- Do you ever feel that you’ve been affected by feelings of edginess, anxiety, or nerves?

- Have you experienced a week or longer of lower-than-usual interest in activities that you usually enjoy? Examples might include work, exercise, or hobbies.

- Have you ever experienced an ‘attack’ of fear, anxiety, or panic?

- Do feelings of anxiety or discomfort around others bother you?

These are just a few examples, and they are primarily concerned with identifying any potential signs of anxiety and depression. By design, they do not assess indicators of wellbeing, such as flourishing, life satisfaction, and happiness.

If you want to find out more about the latter, we have some great articles about Life Satisfaction Scales, as well as Happiness Tests, Surveys, and Quizzes and mental health exercises.

20 Mental Health Interview Questions a Counselor Should Ask

Open-ended questions are never a bad thing when you’re trying to start a discussion about mental health.

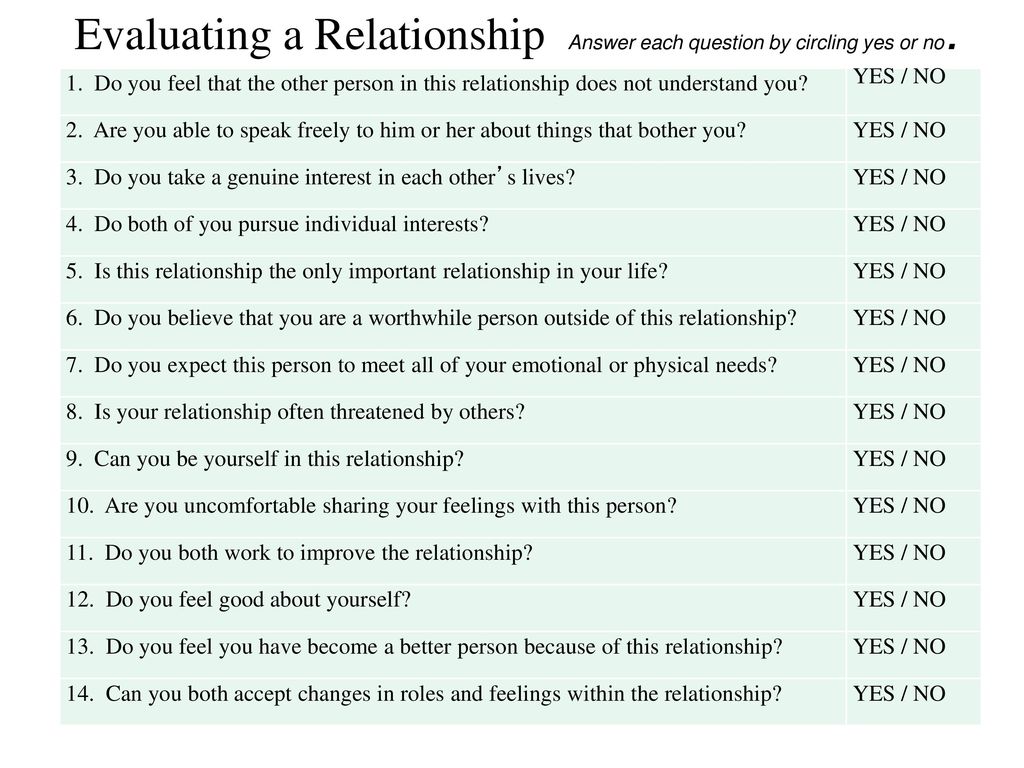

A study by Connell, O’Cathain, and Brazier (2014) suggested that seven quality of life domains are particularly relevant to a counselor who wants to open up dialogue with a client: physical health, wellbeing, autonomy, choice and control, self-perception, hope and hopelessness, relationships and belonging, and activity.

Physical health

Questions of this type were related to feelings such as agitation, restlessness, sleep, pain, and somatic symptoms. Examples of prompts to investigate this domain could include:

- Tell me about your sleeping habits over the past X months. Have you noticed any changes? Difficulty sleeping? Restlessness?

- How would you describe your appetite over the past X weeks? Have your eating habits changed in any way?

Wellbeing (and ill-being)

These questions looked at feelings of anxiety, distress, motivation, and energy. The ‘absence of negative feelings of ill-being,’ was understandably related to a higher perceived quality of life Connell et al., 2014). Sample prompts might include:

- Could you tell me about any times over the past few months that you’ve been bothered by low feelings, stress, or sadness?

- How frequently have you had little pleasure or interest in the activities you usually enjoy? Would you tell me more?

Autonomy, choice, and control

Questions about independence and autonomy were related to quality of life aspects such as pride, dignity, and privacy. Potential questions might include:

Potential questions might include:

- How often during the past X months have you felt as though your moods, or your life, were under your control?

- How frequently have you been bothered by not being able to stop worrying?

Self-perception

Self-perception questions were related to patients’ confidence, self-esteem, and feelings of being capable of doing the things they wanted to do. Counselors might want to use the following prompts:

- Tell me about how confident you have been feeling in your capabilities recently.

- Let’s talk about how often you have felt satisfied with yourself over the past X months.

Hope and hopelessness

These questions ask about the patient’s view of the future, their hopes and goals, and the actions they were taking toward them.

- How often over the past few weeks have you felt the future was bleak?

- Can you tell me about your hopes and dreams for the future? What feelings have you had recently about working toward those goals?

Relationships and belonging

These questions consider how the client felt they ‘fit in with society,’ were supported, and possessed meaningful relationships. Examples include:

Examples include:

- Describe how ‘supported’ you feel by others around you – your friends, family, or otherwise.

- Let’s discuss how you have been feeling about your relationships recently.

Activity

The more purposeful, meaningful, and constructive a client perceived their activities to be, the better.

- Tell me about any important activities or projects that you’ve been involved with recently. How much enjoyment do you get from these?

- How frequently have you been doing things that mean something to you or your life?

Read our post on mental health activities to assist clients in this area.

Other mental health questions for counselors

Another useful source of questions can be found on this website by Mental Health America (n.d.a; n.d.b). You’ll find questions about:

Depression – e.g., How bothered have you felt about tiredness or low energy over the past two weeks? How bothered have you felt about thoughts that you’ve let yourself or others down?

Anxiety – e. g., Over the last two weeks, how bothered have you been by feelings of fear or dread, as though something terrible might happen? How often have you been bothered by so much restlessness that you can’t sit still?

g., Over the last two weeks, how bothered have you been by feelings of fear or dread, as though something terrible might happen? How often have you been bothered by so much restlessness that you can’t sit still?

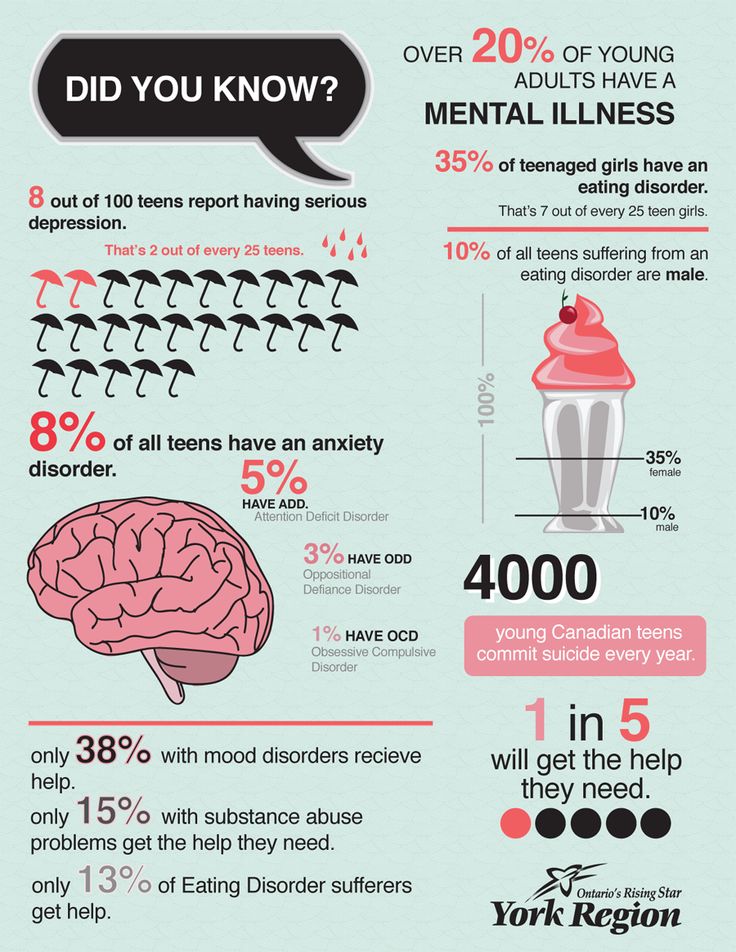

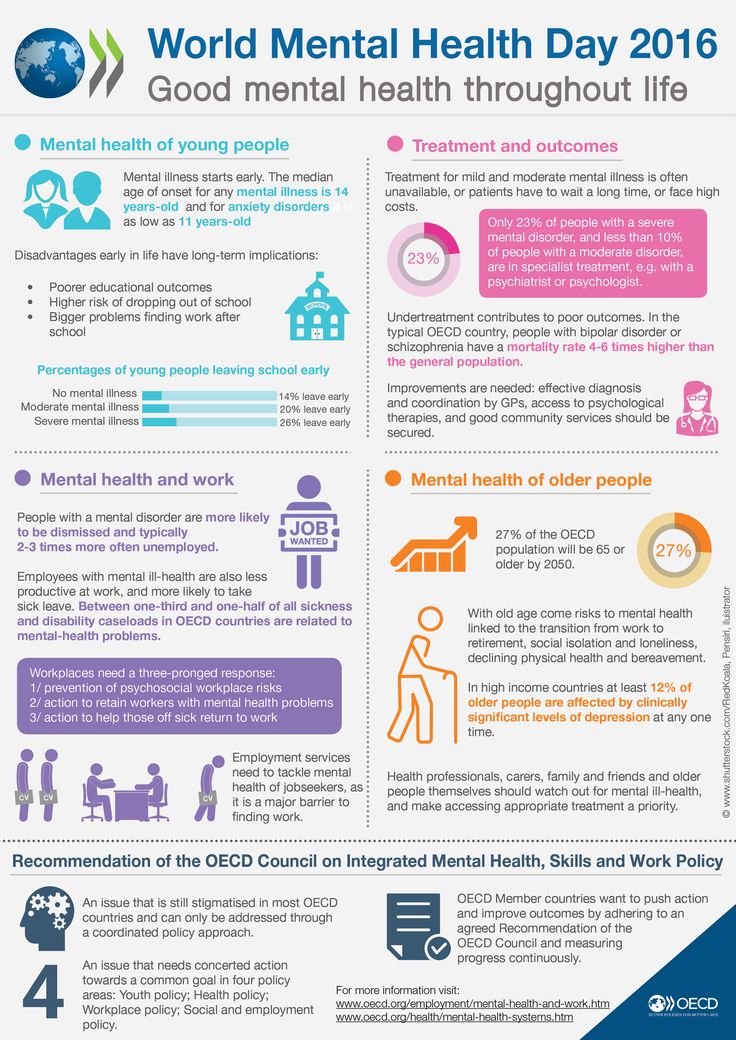

Mental health for young people – e.g., How often have you felt fidgety or unable to sit still? Have you felt less interested in school?

Whatever counseling interview questions you choose to ask as a practitioner, you may find that you need to refer your client to a different healthcare provider. You can help others improve their mental health by making them feel supported and ensuring they are aware of their options for continued support.

10 Mental Health Questions Aimed at Students

Life skills and self-efficacy are two key aspects of mental health, which is why these measures are sometimes used to assess the latter.

Bashir (2018) mentions several assessments used to assess mental health, including:

- The Life Skills Assessment Questionnaire (Saatchi, Kamkkari, & Askarian, 2010)

- The Self-Efficacy Scale (Singh & Narain, 2014)

- Mental Health Scale (Talesara & Bano, 2017)

Bashir (2018) found “a positive significant relationship between the mental health of senior secondary school students with life skills and self-efficacy,” suggesting that the two measures together can be used to get an understanding of students’ mental health.

Mental health questions for students

Other self-efficacy and life skills measures could give us a good idea of some example mental health questions for students. The following may help:

Academic self-efficacy questions for students

How much confidence do you have that you can successfully:

- Complete homework within deadlines?

- Focus on school subjects?

- Get information on class assignments from the library?

- Take part in class discussions?

- Keep your academic work organized?

Mental health questions (World Health Organization, 2013)

- Over the last 12 months, how frequently have you felt so worried about something that you were unable to sleep at night?

- Over the last 12 months, how frequently have you felt alone or lonely?

- Over the last 12 months, how often did you seriously consider attempting suicide?

- Over the last 12 months, did you ever plan how you might attempt suicide?

- How many close friends would you say you have?

As with all the other questions in this article, you’ll probably want to tweak and amend these items to suit your audience.

7 Questions for Group Discussion

The catch-all term “mental health group” can refer to several different things. Mental health groups may gather together for therapy or may be more informal peer support groups. You may also find yourself part of a group that’s purely for friends, family, and carers of those whose mental health is a concern.

Whatever group you find yourself in, the World Health Organization (2017) has some suggestions that will help you create a safe and productive space.

Mental health group best practices

Everything that is said in therapy should remain confidential; nothing from the discussion should be shared outside of the group setting.

Bear in mind that not everyone in the discussion will be at the same stage. Some may be new, others may be more seasoned or regular visitors.

Recognize that people won’t necessarily get along, but they all are welcome anyway.

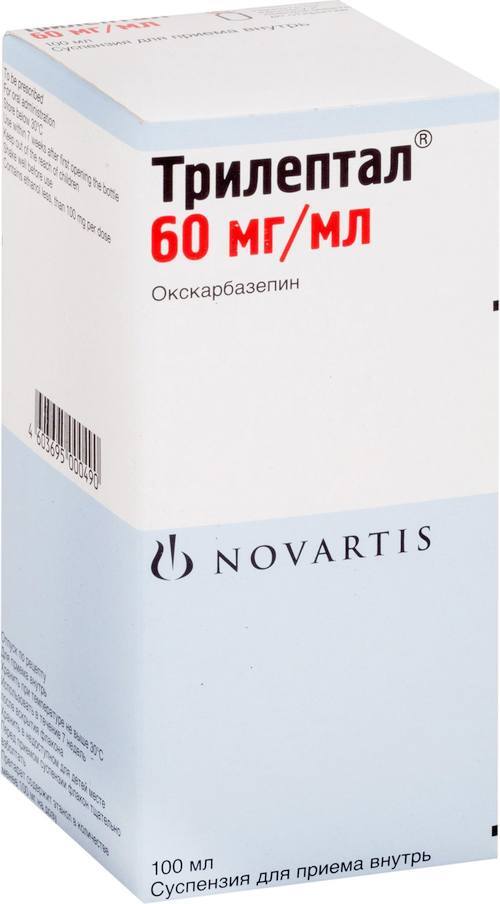

Try not to view peer support or group discussions as a panacea for mental conditions. While they may be a great place to get suggestions or clarity, mental health is about feeling good in more than one way. Participants or caregivers may also require coaching, counseling, or medication to feel better.

While they may be a great place to get suggestions or clarity, mental health is about feeling good in more than one way. Participants or caregivers may also require coaching, counseling, or medication to feel better.

7 Group questions

What questions can we ask to get some discussion flowing in a mental health group?

You may want to start with a focus for your discussion. Ask someone to share a story, experience, or step in as a facilitator with a video about the theme at hand. If you are discussing the role of social support, for example, you may have a presentation or case study prepared on the importance of friends and family.

Once you’ve opened with your story or resource, try some of these to spark a discussion (Gruttadaro & Cepla, 2014):

- How do you feel about the story you just heard? What was your first reaction? How about as the story unfolded?

- What were your thoughts regarding the signs and symptoms of this mental health issue? Have you experienced any of these yourself or in someone you know?

- How would you react if you noticed these in someone you care about?

- How might taking action benefit you and the person you care about?

- What actions could you take to help someone who is exhibiting these signs and symptoms?

- What do you believe is important for anyone to be aware of if they know someone with this mental health issue?

- What experiences have you had that are related to this story? What was similar? What differed?

Common Mental Health Research Questions

Curious to know the top research questions related to mental health worldwide? Tomlinson et al. (2009) identified some of the key priorities for researchers to look at.

(2009) identified some of the key priorities for researchers to look at.

The group came up with 55 questions, and the top three topics included:

- Health policy and systems research topics – e.g., How can health policy and systems research help us create parenting and social skills interventions for early childhood care in a cost-efficient, feasible, and effective way?

- Cost-effective interventions for low-resource settings – e.g., How can affordable interventions be delivered in settings where resources are scarce?

- Questions about child and teen mental disorders – e.g., How effective and cost-effective are school-based mental health treatments for special needs schoolchildren?

9 Mental Health Questions a Patient Can Ask

Engaging with your mental health practitioner is one of the best ways to get the most out of your check-ups. The healthcare system is changing, and gone are the days when a patient sat passively for a diagnosis or prescription (Rogers & Maini, 2016).

These days, arguably, medical dialogues place more emphasis on helping a client help themselves through information, education, and commitment to a better lifestyle. It’s good news indeed for anyone who wants to get proactive about their mental health. So what should you be asking your practitioner?

Before committing to a mental health practitioner, you’ll need to know a few things about the services they provide. Many therapists can provide psychological treatments but aren’t able to prescribe medication. You’ll need a psychiatrist or physician for that.

Bear this in mind, and consider the following questions when you’re deciding whether a provider is right for you (Association for Children’s Mental Health, n.d.; Think Mental Health, n.d.):

- What is your experience with treating others with my mental health condition?

- Will you be able to collaborate or liaise with my physician on an integrated care plan?

- What does a typical appointment with you look like?

- What treatments or therapies are you licensed to administer?

- Are there benefits or risks that I should know about these therapies?

- What is the general time frame in which most patients will see results?

- How will I know if the treatment is having an effect?

- How long does this type of treatment last?

- What does research say about this type of treatment?

12 Questions to Ask Yourself

Mental Health Week takes place every year in October.

It is an awareness-raising campaign that encourages us to tune in early to the symptoms of mental illness.

But, of course, you can always check in with yourself as regularly as you like.

Example questions about wellbeing

The Canadian Mental Health Association (n.d.) provides some self-report questions that you can start with; these questions cover six areas and require only agree/disagree responses. Try some of these as an example:

- Sense of self questions– e.g., I see myself as a good person. I feel that others respect me, yet I can still feel fine about myself if I disagree with them.

- Sense of belonging questions – e.g., I have others around me who support me. I feel positive about my relationships with others and my interpersonal connections.

- Sense of meaning or purpose questions – e.g., I get satisfaction from the things I do. I challenge my perspectives about the world and what I believe in.

- Emotional resilience questions – e.

g., I feel I handle things quite well when obstacles get in my way. I accept that I can’t always control things, but I do what I can when I can.

g., I feel I handle things quite well when obstacles get in my way. I accept that I can’t always control things, but I do what I can when I can. - Enjoyment and hope questions – e.g., I have a positive outlook on my life. I like myself for who I am.

- Contribution questions – e.g., The things that I do have an impact. My actions matter to those around me.

9 Self-Reflection Questions

Elsewhere on PositivePsychology.com, we’ve written about the many potential benefits of narrative therapy. If you’re looking for some writing or journal prompts to help you get started, you can try putting your responses to these questions down on paper (Post Trauma Institute, 2019).

- Have my sleeping habits changed? Do I wake up and fall asleep at regular times? When I sleep, how would I describe the quality of my rest?

- How has my appetite increased or decreased recently?

- Am I having trouble focusing at work or school? Can I concentrate on the things I want to do? Do I find pleasure in things that usually make me happy?

- Am I socializing with my friends as much as I usually do? How about spending time with my family? Am I withdrawing or pulling away from those around me who matter?

- Do I feel like I’m maintaining a healthy balance between leisure, myself, my career, physical activity, and those I care about? How about other things that matter to me?

- How relaxed do I feel most of the time, out of 10? Is this the same, more, or less than usual?

- How do I feel most of the time? Happy? Anxious? Satisfied? Sad?

- What are my energy levels like when I finish my day? Are there any significant changes in my tiredness?

- Am I having any extreme emotions or mood swings? Any suicidal thoughts, breakdowns, or panic attacks?

It may help to keep track of your responses over time and take notice of any differences in your answers. It should go without saying that the earlier you seek out any help you may need, the better. Consider reading one of these recommended mental health books if you are still unsure about seeking help.

It should go without saying that the earlier you seek out any help you may need, the better. Consider reading one of these recommended mental health books if you are still unsure about seeking help.

A Take-Home Message

Mental health is not about the absence of mental illness. When we take the time to ask ourselves and others about our mental states, we can potentially make some crucial steps toward wellbeing.

As Keyes (2002) describes, we can think of our mental health as a continuum, with languishing at one end and flourishing at the other. By starting a dialogue and showing that we care, we can help each other get the help we need and potentially begin to feel better.

What questions have you asked yourself before? And what would you add to our list? Let us know in the comments below!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free.

- Association for Children’s Mental Health. (n.

d.). Questions to ask your mental health professional about treatment options, medications, and more. Retrieved July 29, 2021 from http://www.acmh-mi.org/get-information/childrens-mental-health-101/questions-ask-treatment/

d.). Questions to ask your mental health professional about treatment options, medications, and more. Retrieved July 29, 2021 from http://www.acmh-mi.org/get-information/childrens-mental-health-101/questions-ask-treatment/ - Bashir, L. (2018). Mental health among senior secondary school students in relation to life skills and self-efficacy. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research Review, 3(9), 587–591.

- Canadian Mental Health Association. (n.d.). Check in on your mental health. Retrieved from https://mentalhealthweek.ca/check-in-on-your-mental-health/

- Connell, J., O’Cathain, A., Brazier, J. (2014). Measuring quality of life in mental health: Are we asking the right questions? Social Science & Medicine, 120, 12–20.

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207–222.

- Means-Christensen, A. J.

, Sherbourne, C. D., Roy-Byrne, P. P., Craske, M. G., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: Diagnostic accuracy of the Anxiety and Depression Detector. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(2), 108–118.

, Sherbourne, C. D., Roy-Byrne, P. P., Craske, M. G., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: Diagnostic accuracy of the Anxiety and Depression Detector. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(2), 108–118. - Mental Health America. (n.d.a). Questions to ask a provider. Retrieved July 29, 2021, from https://www.mhanational.org/questions-ask-provider/

- Mental Health America. (n.d.b). Mental health screening tools. Retrieved July 29, 2021, from https://screening.mhanational.org/screening-tools

- Gruttadaro, D., & Cepla, E. (2014). Say it out loud: NAMI discussion group facilitation guide. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Retrieved July 29, 2021, from https://www.nami.org/getattachment/Get-Involved/Raise-Awareness/Engage-Your-Community/Say-it-Out-Loud/Say-it-Out-Loud-Discussion-Group-Facilitation-Guide.pdf

- O’Donnell, M. L., Bryant, R. A., Creamer, M., & Carty, J.

(2008). Mental health following traumatic injury: Toward a health system model of early psychological intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 387–406.

(2008). Mental health following traumatic injury: Toward a health system model of early psychological intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(3), 387–406. - Post Trauma Institute. (2019). How to do a mental health check-up DIY style! Retrieved from https://www.posttraumainstitute.com/how-to-do-a-mental-health-check-up-diy-style/

- Rogers, J., & Maini, A. (2016). Coaching for health: Why it works and how to do it. Open University Press.

- Saatchi, M., Kamkkari, K., & Askarian, M. (2010). Life skills questionnaire. Psychological Tests Publish Edits, 85.

- Singh, A. K., & Narain, S. (2014). Manual for Self-Efficacy Scale. National Psychological Corporation.

- Talesara, S., & Bano, A. (2017). Mental Health Scale. National Psychological Corporation.

- Think Mental Health. (n.d.). Questions to ask your GP – What to discuss. Retrieved from https://www.thinkmentalhealthwa.com.au/mental-health-support-services/how-your-gp-can-help/questions-to-ask-your-gp/

- Tomlinson, M.

, Rudan, I., Saxena, S., Swartz, L., Tsai, A. C., & Patel, V. (2009). Setting priorities for global mental health research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(6), 438–446.

, Rudan, I., Saxena, S., Swartz, L., Tsai, A. C., & Patel, V. (2009). Setting priorities for global mental health research. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(6), 438–446. - World Health Organization. (2013). Global school-based student health survey: 2013 core questionnaire modules. Retrieved July 29, 2021, from http://www.who.int/entity/chp/gshs/GSHS_Core_Modules_2013_English.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2017). Creating peer support groups in mental health and related areas: WHO QualityRights training to act, unite, and empower for mental health (pilot version) (No. WHO/MSD/MHP/17.13).

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find Country »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- e

- ё 9000

- x

- C

- h

- Sh

9000 WHO in countries » - Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Schizophrenia

Key Facts

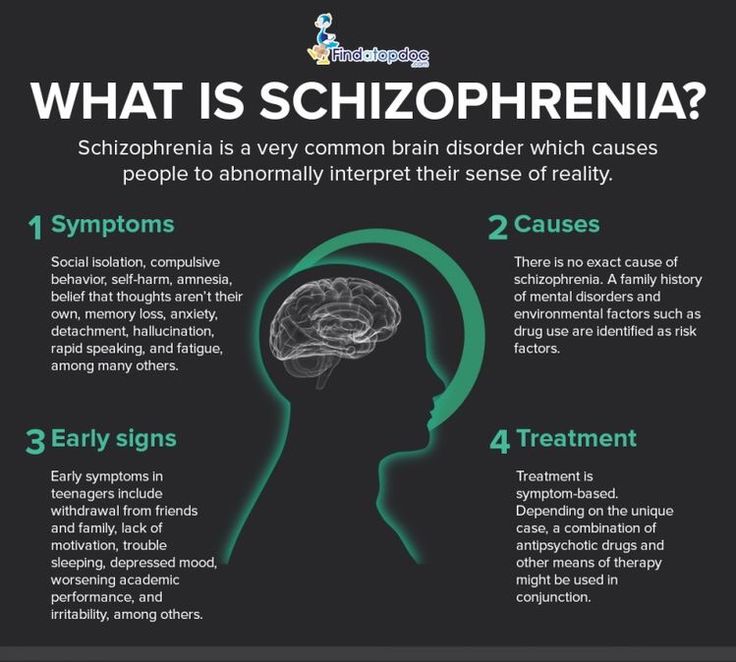

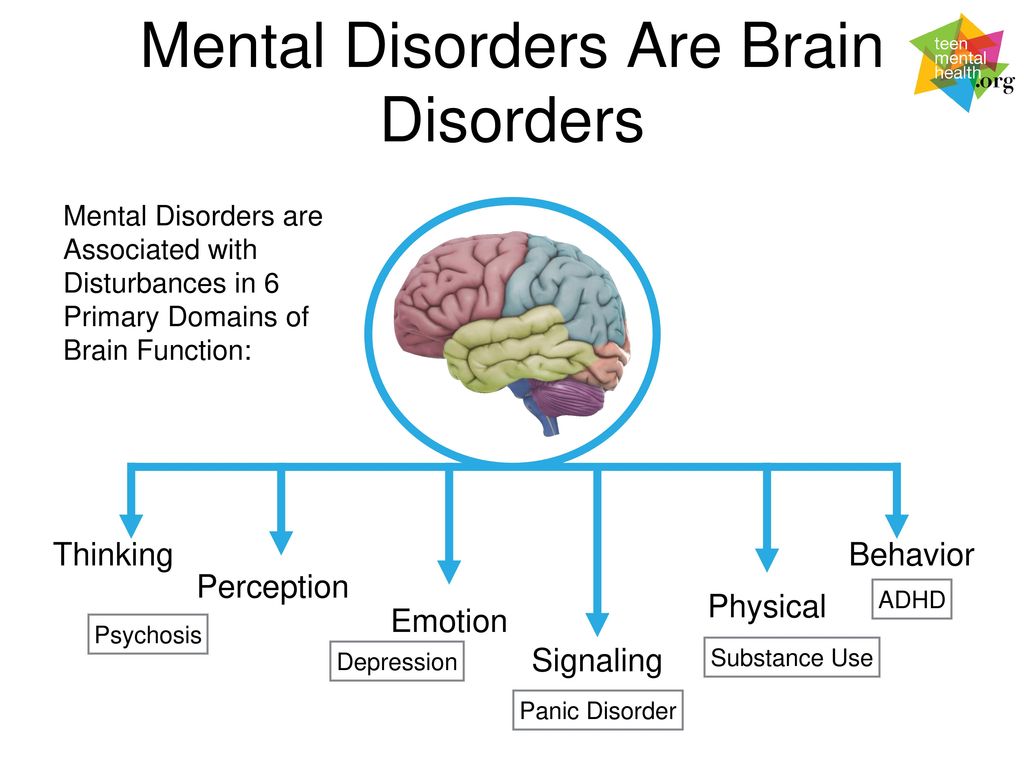

- Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder that affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people worldwide.

- Schizophrenia causes psychosis, is associated with severe disability, and can negatively affect all areas of life, including personal, family, social, academic and work life.

- People with schizophrenia are often subject to stigma, discrimination and human rights violations.

- Globally, more than two thirds of people with psychosis do not receive specialized mental health care.

- There are a number of effective care options for patients with schizophrenia that can lead to a complete recovery of at least one in three patients.

Symptoms

Schizophrenia is characterized by significant disturbances in perception of reality and behavioral changes such as:

- persistent delusions: the patient has a persistent belief in the truth of certain things, despite evidence to the contrary;

- persistent hallucinations: the patient hears, sees, touches non-existent things and smells non-existent smells;

- sensation of external influence, control or passivity: the presence in the patient of the sensation that his feelings, impulses, actions or thoughts are dictated from outside, put in or disappear from consciousness by someone else's will, or that his thoughts are broadcast to others;

- disorganized thinking, often expressed in incoherent or pointless speech;

- Significant disorganization of behavior, which manifests itself, for example, in the performance by the patient of actions that may seem strange or meaningless, or in an unpredictable or inappropriate emotional reaction that does not give the patient the opportunity to organization of their behavior;

- "negative symptoms" such as extreme poverty of speech, smoothness of emotional reactions, inability to feel interest or pleasure, social autism; and/or

- Extreme agitation or, on the contrary, slowness of movements, freezing in unusual postures.

People with schizophrenia often also experience persistent cognitive or thinking problems that affect memory, attention, or problem-solving skills.

At least one third of patients with schizophrenia experience complete remission of symptoms (1). In some, periods of remission and exacerbation of symptoms follow each other throughout life, in others there is a gradual increase in symptoms.

Scope and impact

Schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people, or 1 in 300 people (0.32%) worldwide. Among adults, the rate is 1 in 222 (0.45%) (2). Schizophrenia is less common than many other mental disorders. Onset is most common in late adolescence and between the ages of 20 and 30; while women tend to have a later onset of the disease.

Schizophrenia is often accompanied by significant stress and difficulties in personal relationships, family life, social contacts, studies, work or other important areas of life.

Individuals with schizophrenia are 2-3 times more likely to die early than the population average (2). It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

It is often associated with physical illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic disease, and infectious disease.

Patients with schizophrenia often become the object of human rights violations both within the walls of psychiatric institutions and in everyday life. Significant stigmatization of people with this disease is a widespread phenomenon that leads to their social isolation and has a negative impact on their relationships with others, including family and friends. This creates grounds for discrimination, which in turn limits access to health services in general, education, housing and employment.

Humanitarian emergencies and health crises can cause intense stress and fear, disrupt social support mechanisms, lead to isolation and disruption of health services and supply of medicines. All these shocks can have a negative impact on the lives of people with schizophrenia, in particular by exacerbating existing symptoms of the disease. People with schizophrenia are more vulnerable during emergencies to various human rights violations and, in particular, face neglect, abandonment, homelessness, abuse and social exclusion.

Causes of schizophrenia

Science has not established any one cause of the disease. It is believed that schizophrenia may be the result of the interaction of a number of genetic and environmental factors. Psychosocial factors may also influence the onset and course of schizophrenia. In particular, heavy marijuana abuse is associated with an increased risk of this mental disorder.

Assistance services

At present, the vast majority of people with schizophrenia do not receive mental health care worldwide. Approximately 50% of patients in psychiatric hospitals are diagnosed with schizophrenia (4). Only 31.3% of people with psychosis get specialized mental health care (5). Much of the resources allocated to mental health services are inefficiently spent on the care of patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Available scientific evidence clearly indicates that hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals is not an effective treatment for mental disorders and is regularly associated with the violation of the basic rights of patients with schizophrenia. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

Therefore, it is necessary to ensure the expansion and acceleration of work on the transfer of functions in the field of mental health care from psychiatric institutions to the level of local communities. Such work should begin with the organization of the provision a wide range of quality community-based mental health services. Options for community-based mental health care include integrating this type of care into primary health care and hospital care. general care, setting up community mental health centres, outpatient care centres, social housing with nursing care and social home care services. Involvement in the care process is important the patient with schizophrenia, his family members and members of local communities.

Schizophrenia management and care

There are a number of effective approaches to treating people with schizophrenia, including medication, psychoeducation, family therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation (eg life skills education). The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

The most important interventions for helping people with schizophrenia are assisted living, special housing and employment assistance. It is extremely important for people with schizophrenia and their families and/or caregivers to a recovery-centered approach that empowers people to participate in decisions about their care.

WHO activities

steps are in place to ensure that appropriate services are provided to people with mental disorders, including schizophrenia. One of the key recommendations The action plan is to transfer the function of providing assistance from institutions to local communities. WHO Special Mental Health Initiative aims to further progress towards the goals of the Comprehensive Plan mental health action 2013–2030 by ensuring that 100 million more people have access to quality and affordable mental health care.

The WHO Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) is working to develop evidence-based technical guidelines, tools and training packages to scale up services in countries, especially in low-resource settings. The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The program focuses on a priority list of mental health disorders, including psychosis, and aims to strengthen the capacity of non-specialized health workers in as part of an integrated approach to mental health care at all levels of care. To date, the mhGAP Program has been implemented in more than 100 WHO Member States.

The WHO QualityRights project aims to improve the quality of care and better protect human rights in mental health and social care settings and to expand opportunities of various organizations and associations to defend the rights of persons with mental disorders and psychosocial disabilities.

The WHO guidelines on community mental health services and human rights-based approaches provide information for all stakeholders who intend to develop or transform mental health systems and services. health in accordance with international human rights standards, including the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Bibliography

(1) Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska E, Siegel C, Wanderling J. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

(2) Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool?params=gbd-api-2019-permalink/27a7644e8ad28e739382d31e77589dd7 (accessed 25 September 2021)

(3) LaursenTM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology , 2014;10, 425-438.

(4) WHO. Mental health systems in selected low- and middle-income countries: a WHO-AIMS cross-national analysis. WHO: Geneva, 2009

(5) Jaeschke K et al. Global estimates of service coverage for severe mental disorders: findings from the WHO Mental Health Atlas 2017 Glob Ment Health 2021;8:e27.

Dementia

Dementia- Popular Topics

- Air pollution

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Hepatitis

- Data and statistics »

- News bulletin

- The facts are clear

- Publications

- Find Country »

- A

- B

- C

- D

- D

- E 9000 In

- Ф

- x

- C

- h

- Sh

9000 WHO in countries »- Reporting

- Regions »

- Africa

- America

- Southeast Asia

- Europe

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Western Pacific

- Media Center

- Press releases

- Statements

- Media messages

- Comments

- Reporting

- Online Q&A

- Developments

- Photo reports

- Questions and answers

- Update

- Emergencies "

- News "

- Disease Outbreak News

- WHO Data »

- Dashboards »

- COVID-19 Monitoring Dashboard

- Basic moments "

- About WHO »

- CEO

- About WHO

- WHO activities

- Where does WHO work?

- Governing Bodies »

- World Health Assembly

- Executive committee

- Main page/

- Media Center /

- Newsletters/

- Read more/

- Dementia

Cathy Greenblat

© A photo

Dementia is a syndrome, usually chronic or progressive, in which there is a deterioration in cognitive function (ie the ability to think) to a greater extent than is expected with normal aging. There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

Dementia is caused by a variety of illnesses and injuries that primarily or secondarily cause brain damage, such as Alzheimer's disease or stroke.

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide. It can have a profound impact not only on the people who suffer it, but also on their families and caregivers. There is often a lack of awareness and understanding about dementia, leading to stigma and barriers to diagnosis and care. The impact of dementia on caregivers, families and society as a whole can be physical, psychological, social and economic.

Signs and symptoms

Dementia affects people differently, depending on the impact of the disease and on the individual before the disease. The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

Early stage: The early stage of dementia often goes unnoticed because it develops gradually. Common symptoms include:

- forgetfulness;

- loss of track of time;

- disorientation in a familiar area.

Intermediate: As dementia progresses towards the intermediate stage, the signs and symptoms become more pronounced and increasingly narrowing. They include:

- forgetting about recent events and people's names;

- disorientation at home;

- increasing difficulties in communication;

- need for help with self-care;

- behavioral difficulties, including aimless walking and asking the same questions.

Late stage: In the late stage of dementia, almost complete dependence and inactivity develops. Memory impairment becomes significant, and physical signs and symptoms become more obvious. Symptoms include:

Symptoms include:

- disorientation in time and space;

- difficulty in recognizing relatives and friends;

- increasing need for help with self-care;

- difficulty in moving;

- behavioral changes that may be aggravated and include aggressiveness.

Common forms of dementia

There are many forms of dementia. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Dementia rates

There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, more than half, almost 60% of them, live in low- and middle-income countries. There are about 10 million new cases of the disease every year.

The proportion of the general population aged 60 years and over with dementia at any point in time is estimated to be between 5% and 8%.

The total number of people with dementia is projected to be around 82 million in 2030 and 152 by 2050. This growth will be driven in large part by an increase in the number of people with dementia in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Currently there is no therapy to cure or change the course of dementia. Numerous new drugs are under investigation and are at various stages of clinical trials.

However, much can be done to support and improve the lives of people with dementia, their caregivers and their families. The main goals of medical care for dementia are:\n

- early diagnosis to ensure early and optimal management;

- optimization of physical health, cognitive abilities, activity and well-being;

- detection and treatment of associated physical illness;

- detection and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms;

- provide information and long-term support for carers.

Risk factors and prevention

Although age is the most important known risk factor for dementia, it is not an inevitable consequence of aging. What’s more, dementia doesn’t just affect the elderly—early onset of dementia (defined as the onset of symptoms before the age of 65) accounts for up to 9% of all cases of dementia.

Research shows that the risk of dementia can be reduced by exercising regularly, not smoking, avoiding the harmful use of alcohol, controlling your weight, eating well, and maintaining normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Other risk factors include depression, low educational attainment, social isolation, and cognitive inactivity.

Social and economic impact

Dementia has a significant social and economic impact in terms of medical costs, social care costs and informal care. In 2015, total global public spending on dementia was estimated at US$818 billion, corresponding to 1.1% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP). Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Impact on families and caregivers

Dementia can have a profound impact on the families of those affected and their caregivers. The physical, emotional and financial burden can put a lot of stress on families and caregivers, and they need support from the health, social, financial and legal systems.

Human rights

People with dementia are often denied the basic rights and freedoms that other people have. In many countries, physical means and chemicals are widely used in nursing homes and intensive care facilities to retain patients, even though there are regulations in place to protect the human rights to freedom and choice.

Providing high-quality care for people with dementia and their caregivers requires appropriate and supportive legal and regulatory frameworks based on internationally recognized human rights standards.

WHO activities

WHO recognizes dementia as a public health priority. In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

- taking action on dementia as a public health priority; raising awareness about dementia and creating supportive environment initiatives for people with dementia; reduced risk of developing dementia;

- reduced risk of dementia; diagnosis, treatment and care;

- dementia information systems; support for carers of people with dementia; and

- research and innovation.

An international monitoring platform, the Global Dementia Observatory, has been established for policy makers and researchers to facilitate monitoring and sharing of information on dementia policy, health care, epidemiology and research. WHO is also developing a knowledge-sharing platform to facilitate the sharing of best practices in the field of dementia.

WHO has developed a dementia action plan to help Member States develop and operationalize dementia action plans. This guidance is closely linked to the WHO Global Observatory on Dementia and includes relevant methodologies, such as a checklist, to guide the preparation, development and implementation of action plans for dementia. In addition, this guide can be helpful in identifying stakeholders and setting priorities.

The WHO Guidelines for Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia provide evidence-based recommendations for interventions to reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia such as physical inactivity and unhealthy diets, and to manage medical conditions associated with dementia including hypertension and diabetes.

Dementia is also a priority condition under the Mental Health Gap Action Program (mhGAP), which is an important resource for general practitioners, especially in low- and middle-income countries, to use when providing health care first line for psychiatric and neurological problems and disorders caused by the use of psychoactive substances.

WHO has developed the iSupport program to provide caregivers of people with dementia with information and skills. The iSupport web tool is available as a printed manual and is already in use in a number of countries. An online version of "iSupport" will be available soon.

","datePublished":"2022-09-20T12:00:00.0000000+00:00","image":"https://cdn.who.int/media/images/default-source/imported/en -dementia_ce93dcb3-2920-4021-9af5-32cbbee9bf9f.jpg?sfvrsn=1a94c86c_3","publisher":{"@type":"Organization","name":"World Health Organization: WHO","logo":{"@type":"ImageObject"," url":"https://www.who.int/Images/SchemaOrg/schemaOrgLogo.jpg","width":250,"height":60}},"dateModified":"2022-09-20T12:00: 00.0000000+00:00","mainEntityOfPage":"https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia","@context":"http://schema.org ","@type":"Article"};

Key Facts

- Dementia is a syndrome in which memory, thinking, behavior and ability to perform daily activities deteriorate.

- Dementia mainly affects the elderly, but is not a normal condition of aging.

- There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, and almost 10 million new cases occur each year.

- Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia, accounting for 60-70% of all cases.

- Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide.

- Dementia has a physical, psychological, social and economic impact not only on those affected, but also on their caregivers, families and society as a whole.

Dementia

Dementia is a syndrome, usually chronic or progressive, in which cognitive function (i.e., the ability to think) deteriorates to a greater extent than is expected in normal aging. There is a degradation of memory, thinking, understanding, speech and the ability to navigate, count, learn and reason. Dementia does not affect consciousness. Cognitive impairment is often accompanied, and sometimes preceded, by deterioration in emotional control, as well as degradation of social behavior or motivation.

Dementia is caused by a variety of illnesses and injuries that primarily or secondarily cause brain damage, such as Alzheimer's disease or stroke.

Dementia is one of the leading causes of disability and addiction among older people worldwide. It can have a profound impact not only on the people who suffer it, but also on their families and caregivers. There is often a lack of awareness and understanding about dementia, leading to stigma and barriers to diagnosis and care. The impact of dementia on caregivers, families and society as a whole can be physical, psychological, social and economic.

Signs and symptoms

Dementia affects people differently, depending on the impact of the disease and on the individual before the disease. The signs and symptoms associated with dementia go through three stages of development.

Early stage: The early stage of dementia often goes unnoticed because it develops gradually. Common symptoms include:

- forgetfulness;

- loss of track of time;

- disorientation in a familiar area.

Intermediate: As dementia progresses towards the intermediate stage, the signs and symptoms become more pronounced and increasingly narrowing. They include:

- forgetting about recent events and people's names;

- disorientation at home;

- increasing difficulties in communication;

- need for help with self-care;

- behavioral difficulties, including aimless walking and asking the same questions.

Late stage: In the late stage of dementia, almost complete dependence and inactivity develops. Memory impairment becomes significant, and physical signs and symptoms become more obvious. Symptoms include:

- disorientation in time and space;

- difficulty in recognizing relatives and friends;

- increasing need for help with self-care;

- difficulty in moving;

- behavioral changes that may be aggravated and include aggressiveness.

Common forms of dementia

There are many forms of dementia. Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Alzheimer's disease is the most common form, accounting for 60-70% of all cases. Other common forms include vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia (abnormal protein inclusions that form inside nerve cells), and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia (degeneration of the frontal lobe of the brain). There are no clear boundaries between different forms of dementia, and mixed forms of dementia often coexist.

Dementia rates

There are about 50 million people with dementia worldwide, more than half, almost 60% of them, live in low- and middle-income countries. There are about 10 million new cases of the disease every year.

The proportion of the general population aged 60 years and over with dementia at any point in time is estimated to be between 5% and 8%.

The total number of people with dementia is projected to be around 82 million in 2030 and 152 by 2050. This growth will be driven in large part by an increase in the number of people with dementia in low- and middle-income countries.

Treatment and care

Currently there is no therapy to cure or change the course of dementia. Numerous new drugs are under investigation and are at various stages of clinical trials.

However, much can be done to support and improve the lives of people with dementia, their caregivers and their families. The main goals of medical care for dementia are:

- early diagnosis to ensure early and optimal management;

- optimization of physical health, cognitive abilities, activity and well-being;

- detection and treatment of associated physical illness;

- detection and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms;

- provide information and long-term support for carers.

Risk factors and prevention

Although age is the most important known risk factor for dementia, it is not an inevitable consequence of aging. What’s more, dementia doesn’t just affect the elderly—early onset of dementia (defined as the onset of symptoms before the age of 65) accounts for up to 9% of all cases of dementia.

Research shows that the risk of dementia can be reduced by exercising regularly, not smoking, avoiding the harmful use of alcohol, controlling your weight, eating well, and maintaining normal blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. Other risk factors include depression, low educational attainment, social isolation, and cognitive inactivity.

Social and economic impact

Dementia has a significant social and economic impact in terms of medical costs, social care costs and informal care. In 2015, total global public spending on dementia was estimated at US$818 billion, corresponding to 1.1% of the world's gross domestic product (GDP). Total spending as a share of GDP ranged from 0.2% in low-income countries to 1.4% in high-income countries.

Impact on families and caregivers

Dementia can have a profound impact on the families of those affected and their caregivers. The physical, emotional and financial burden can put a lot of stress on families and caregivers, and they need support from the health, social, financial and legal systems.

Human rights

People with dementia are often denied the basic rights and freedoms that other people have. In many countries, physical means and chemicals are widely used in nursing homes and intensive care facilities to retain patients, even though there are regulations in place to protect the human rights to freedom and choice.

Providing high-quality care for people with dementia and their caregivers requires appropriate and supportive legal and regulatory frameworks based on internationally recognized human rights standards.

WHO activities

WHO recognizes dementia as a public health priority. In May 2017, the World Health Assembly approved the Global Health Sector Action Plan for the Response to Dementia 2017-2025. The plan is a comprehensive program of action for policy makers, international, regional and national partners and WHO in the following areas:

- taking action on dementia as a public health priority; raising awareness about dementia and creating supportive environment initiatives for people with dementia; reduced risk of developing dementia;

- reduced risk of dementia; diagnosis, treatment and care;

- dementia information systems; support for carers of people with dementia; and

- research and innovation.

An international monitoring platform, the Global Dementia Observatory, has been established for policy makers and researchers to facilitate monitoring and sharing of information on dementia policy, health care, epidemiology and research. WHO is also developing a knowledge-sharing platform to facilitate the sharing of best practices in the field of dementia.

WHO has developed a dementia action plan to help Member States develop and operationalize dementia action plans. This guidance is closely linked to the WHO Global Observatory on Dementia and includes relevant methodologies, such as a checklist, to guide the preparation, development and implementation of action plans for dementia. In addition, this guide can be helpful in identifying stakeholders and setting priorities.

The WHO Guidelines for Reducing the Risk of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia provide evidence-based recommendations for interventions to reduce modifiable risk factors for dementia such as physical inactivity and unhealthy diets, and to manage medical conditions associated with dementia including hypertension and diabetes.