Meditation for bipolar disorder

Meditation and Bipolar Disorder

Overview

Highlights

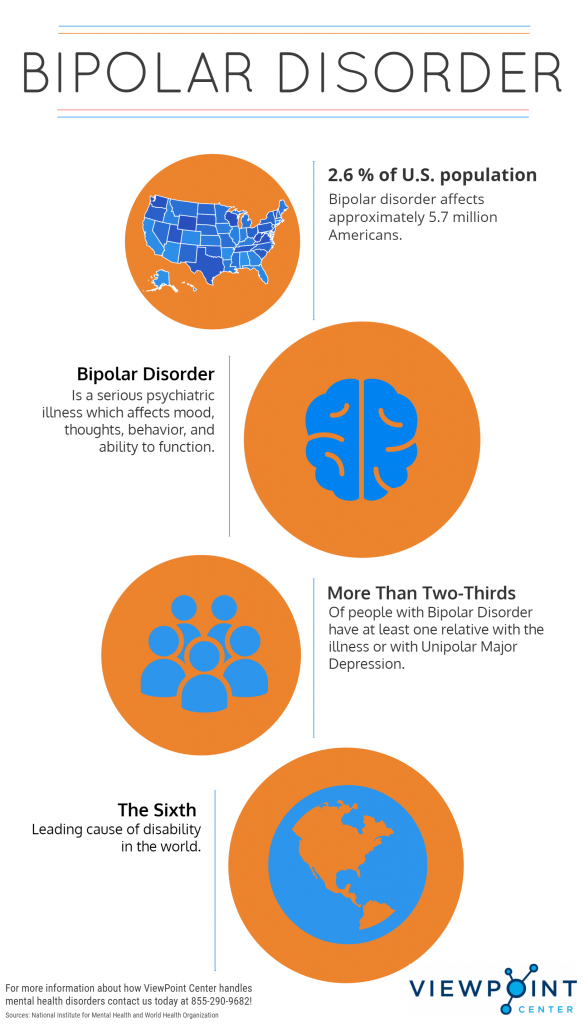

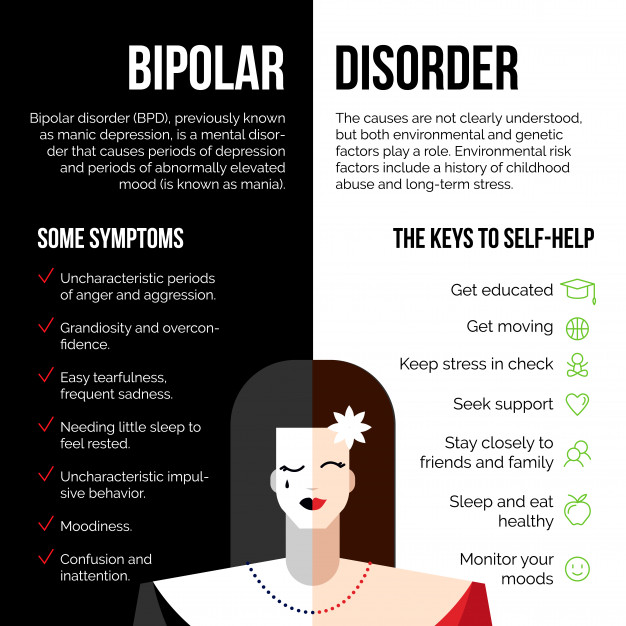

- Bipolar disorder causes extreme highs and lows in mood.

- Meditation helps to relax and reduce stress, helping people with bipolar disorder manage their mood.

- There are many levels and techniques of meditation, and it’s free and easy to practice.

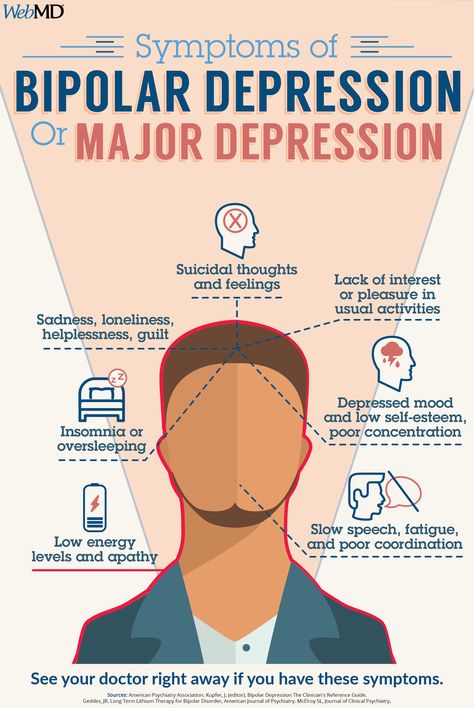

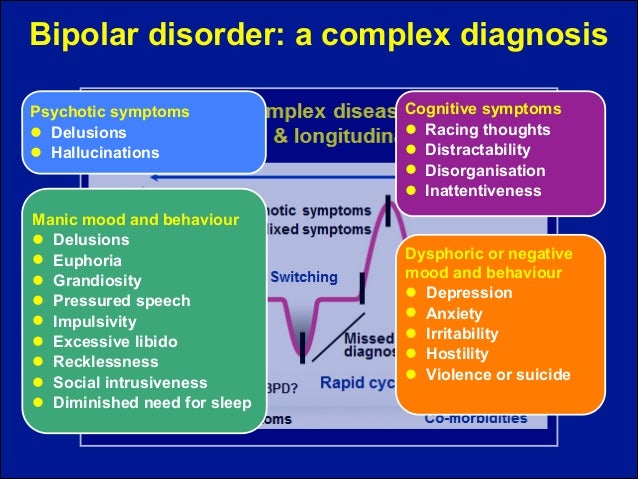

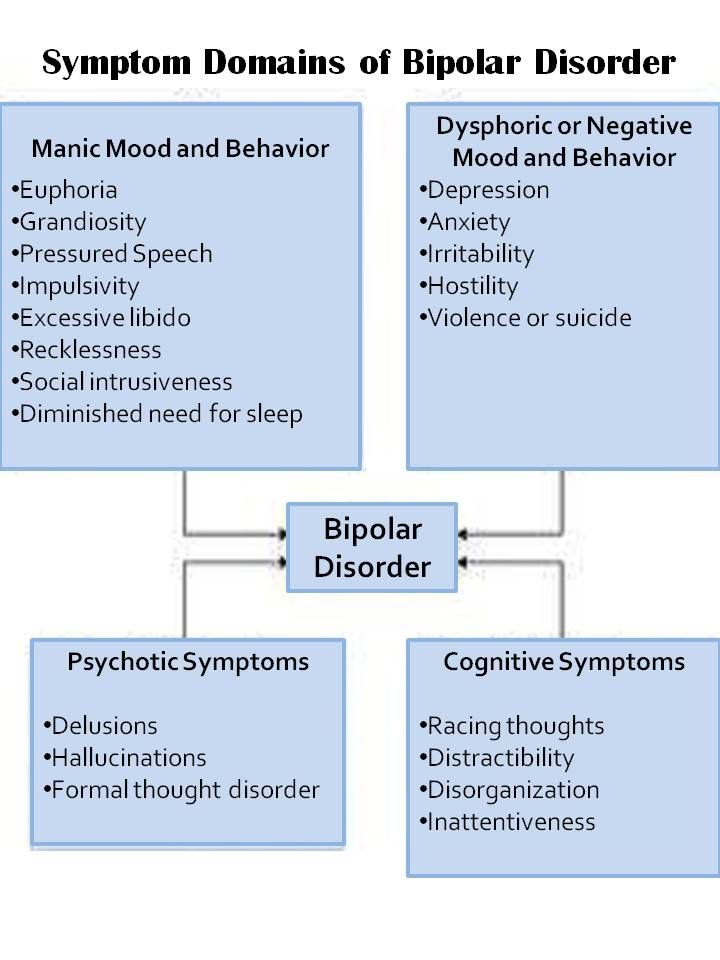

The extreme highs and lows of bipolar disorder can be hard to cope with, and difficult for those around you. The disorder causes mania at one end and depression at the other. Everyday life can be difficult for people with bipolar, and it can be hard to perform well in school or at a job. In addition, personal relationships can become strained.

Treatment for bipolar disorder aims to help you control your mood by keeping it balanced and minimizing the ups and downs. One technique that can help you in this effort is meditation. Meditation is an easy and natural method for relaxing and reducing stress, and can be helpful for people with bipolar disorder.

Read on to learn how it could help you.

Meditation is an ancient technique that involves deep contemplation to help you better understand your inner self. It can relax your mind, help you cope with the stresses of daily life, and give you a more enlightened view of life in general.

There are many different kinds of meditation, but they all usually focus on:

- posture

- breathing

- attention

- relaxation

Q:

During the ups and downs of bipolar disorder, when is the best time to practice meditation?

A:

Once a manic episode has resolved, meditation can be extremely useful. Learning how to sit quietly and experience your breathing can provide a powerful sense of self that can elude people with bipolar disorder, especially if they have been ill for a long time.

Soroya Bacchus, MDAnswers represent the opinions of our medical experts. All content is strictly informational and should not be considered medical advice.

Meditation won’t cure bipolar disorder, but when added to your treatment plan, it could help you stabilize your mood. Bipolar disorder can be complicated by stress, and having bipolar disorder is stressful in itself. Relaxation techniques such as meditation can reduce the stress you experience from bipolar disorder, which can help you keep your mood in check.

One particular type of meditation that can be helpful is called mindfulness meditation. This method, which has received increasing attention in recent years, requires you to “pay attention” to your meditation and to be aware of what you’re thinking and feeling in a nonjudgmental way. It helps you develop an awareness of distressing thoughts and feelings, which enables you to disengage from those thoughts, rather than try to change or fix them.

Meditation is not a quick fix for bipolar disorder, but it can help you over time. One study showed that medication can help people with bipolar disorder in the short term, and that meditation is helpful in promoting a more balanced mood over a longer period of time.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)

- Mindfulness practices are being incorporated into bipolar treatment methods. MBCT, which has shown promise for people with bipolar disorder, combines mindfulness practices with cognitive behavioral therapy. This 2017 study showed that two years after taking part in MBCT, people who continued to practice mindfulness still found that it improved their quality of life and helped prevent depressive relapses.

Meditation helps strengthen the connection between your body and mind. It’s free and easy to practice. It can be done in formal classes or practiced at home, making it accessible to anyone who wants to try it. There are many different levels, from beginner to experienced.

One simple technique requires you to sit quietly and concentrate on your breathing. Focus on the natural rhythm of your breath as you slowly inhale and then slowly exhale.

Other techniques involve:

- focusing on a pleasurable moment, and then trying to recreate it in your mind, as realistically as possible

- repeating a soothing mantra, such as “om”

- slowly focusing on different parts of your body for different sensations, such as heat, tightness, or soreness

- taking a walk and focusing on the sensation of walking

Guided meditation is another option. It’s usually done in a group setting with someone providing cues and guidance. Classes are widely available from trained instructors. In addition, there are many mindfulness apps available for your smartphone. These apps make it easy to practice meditation at home.

It’s usually done in a group setting with someone providing cues and guidance. Classes are widely available from trained instructors. In addition, there are many mindfulness apps available for your smartphone. These apps make it easy to practice meditation at home.

Meditation cannot replace traditional therapy for bipolar disorder, so check with your doctor about other treatments you may need, such as medication or psychotherapy. Even though it’s not a cure for bipolar disorder, meditation can help you relax and reduce stress. It can also help you disengage from stressful or anxious thoughts, and better control your mood.

Meditation is easy and anyone can practice it, at home or in a class. It can be a helpful addition to your bipolar disorder treatment plan.

How to Balance a Healthy Lifestyle

For people with bipolar disorder, meditation and mindfulness may help with mood, emotional regulation, and stress management over time.

For some people with bipolar disorder, meditation may be recommended as an add-on to their treatment plan.

Some people living with bipolar disorder are known to ruminate more, meaning they may focus on negative experiences while in a depressive episode, or on positive experiences while in a manic episode. Meditation can help with long-term mood symptoms.

There’s no “one-size-fits-all” approach to managing bipolar disorder, so meditation may or may not work for you. But with the possible benefits, it could be worth a try.

The practice of meditation goes back thousands of years and has historically been used in spiritual practice. More recently, meditation has been adapted to promote general mindfulness, with a focus on achieving calm and positivity.

There are many kinds of meditation, but most emphasize four basic elements:

- Environment: Find a calm, quiet location with minimal distractions.

- Posture: Whether you’re sitting, lying down, or even walking, it’s important to be comfortable when meditating.

- Attention: Focus your thoughts on what’s happening in the moment.

Focusing on your breathing, feelings (physical or emotional), or repeating a chosen word or set of words can help center your attention.

Focusing on your breathing, feelings (physical or emotional), or repeating a chosen word or set of words can help center your attention. - Attitude: Specifically, try to create an attitude of openness and acceptance. This involves letting your thoughts and feelings come and go without judging them. Acknowledge your thoughts and let them go.

Meditation can be done on your own or as part of a guided program. These programs may include elements from other mindfulness techniques, such as breathing exercises or yoga.

When used in combination with your regular bipolar disorder treatment plan, meditation may support managing your moods and symptoms in the long term.

In a 2019 clinical trial involving 311 people with bipolar disorder II, people who meditated and took their medication had improved symptoms over those who only took medication and didn’t meditate.

The greatest improvements were seen for depressive symptoms, including:

- guilt

- depressed mood

- a sense of helplessness and hopelessness

A 2017 study asked people with bipolar disorder (approximately 3/4 with bipolar disorder I and 1/4 with bipolar disorder II) to report their experiences with mindfulness practices over the course of 2 years.

The results suggest that structured mindfulness exercises — including meditation — were associated with long-lasting improvements in self-reported symptoms. Even unstructured mindfulness practices, like daily mindful breathing, were associated with preventing depressive episodes and other improvements in daily life.

Research in 2018 suggests that people with bipolar disorder who participated in mindfulness-based interventions, including meditation, had significant improvements in their depression and anxiety symptoms but not manic symptoms.

Meditation and psychosis

Meditation may worsen symptoms for some people with manic episodes.

A 2019 review suggests that for some people who are especially susceptible to mania with symptoms of psychosis, meditation may trigger psychosis. But it’s currently unclear what may cause this.

These results don’t cancel out the benefits that many others with bipolar disorder may experience with meditation. However, people who are prone to psychosis may want to talk with their treatment team before starting meditation.

There are also ways to adapt meditation and mindfulness practices to avoid triggering psychosis, such as focusing on real-life awareness and breathing rather than abstract philosophies like cosmic energy and chakras.

There’s no “right” way to practice meditation — it’s all about finding components of meditation and mindfulness that work well for you.

Meditation can be attempted on your own by focusing on the key elements described above, or you can try a more guided approach. Meditation classes and support are often available from community resources, including:

- yoga centers

- athletic clubs

- hospitals and clinics

You may also find it helpful to find a therapist who’s trained in the use of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy or mindfulness-based stress reduction, two evidence-based strategies that use many aspects of meditation. A healthcare professional can help provide recommendations for qualified pros in your area.

You could also use online tools or smartphone apps that promote mindfulness. Existing results from clinical trials suggest that these tools, when used regularly as part of a guided mindfulness routine, can help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression and improve overall well-being.

Existing results from clinical trials suggest that these tools, when used regularly as part of a guided mindfulness routine, can help reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression and improve overall well-being.

Meditation won’t cure bipolar disorder, but it may help improve your mood.

The best results have been seen for symptoms of depression associated with bipolar disorder, along with symptoms of anxiety. Meditation may also help with long-term mood symptoms — meaning that it may help prevent the extreme ups and downs associated with bipolar disorder.

Scientists who study the brain believe this is because mindfulness actually changes structures within the brain involved in emotional regulation and stress management. In this way, mindful meditation can help improve self-awareness and self-regulation of mood.

When added to your treatment plan for bipolar disorder, meditation may help improve depressive symptoms and promote long-term mood symptoms.

Some types of meditation may not work well for people with mania and psychosis. It’s important to talk with your doctor or treatment team before starting any mindfulness-based techniques.

It’s important to talk with your doctor or treatment team before starting any mindfulness-based techniques.

You may want to try using online tools or apps to help guide your meditation at home, or you can find structured programs in your community to get started. Your healthcare team can also help connect you with a therapist who specializes in mindfulness-based techniques if you’re interested.

It can take a while to get used to meditation and for it to become part of your routine. But as with any lifestyle change, practice will help make meditation feel more natural — and can help you lay the foundation for long-lasting results.

Mindful Meditation

- Material Information

- Therapy

- Views: 8923

- Previous article Treatment of childhood trauma

- Next article Spring aggravation: how not to become discouraged

Set font

- Size

- Style

- Reading mode

Material content

- Mindful Meditation

- A conscious approach to the transformation of consciousness

- Attentive brain

- Adolescent brain and prefrontal cortex

- The Three Legs of the Mindfulness Tripod

- Stabilized consciousness

- All pages

In this chapter I will tell you how to use concentrated and conscious attention in order to first feel and then change the turbulent and annoying current of energy and information.

Unreliable mind

When I first saw Jonathan, he was only sixteen and in tenth grade. He shuffled into the office, his jeans hanging low on his hips, his long blond hair falling over his eyes. He said that the last couple of months he felt bad and sad, and from time to time, for no reason, he began to cry .

I learned that he had a group of close friends at school, and there were no problems with his studies. He indifferently, almost dismissively, said that everything was fine at home: his older sister and younger brother annoyed him, and his parents annoyed him, as always. It seemed that nothing unusual happened in Jonathan's life.

Still, something was definitely going wrong. Tears and bad moods were accompanied by Jonathan's uncontrollable fits of rage. Ordinary situations, when, for example, his sister was late or his brother took his guitar without permission, caused him great anger.

This drop in reactivity threshold worried not only his parents and me, but also Jonathan himself. He embarrassedly said that 's 's outbursts, while not something new, were getting stronger and scaring him.

He embarrassedly said that 's 's outbursts, while not something new, were getting stronger and scaring him.

He had similar episodes in high school, but his parents attributed it to adolescence and did not attach much importance to them at first. They brought Jonathan to me when he shared with them his feeling that he could no longer live.

The term mood means the general emotional background that we express through feelings, actions and reactions.

Just being next to Jonathan, I felt his despair and moral exhaustion . He admitted that he also noticed problems with sleep, decreased appetite and suicidal thoughts. But I determined that while Jonathan did not attempt suicide and did not plan them.

In textbooks on psychiatry, such a set of symptoms would point to deep depression , but I didn't want to discount other factors that were potentially related to Jonathan's condition.

In his family, his maternal uncle suffered from drug addiction and his paternal grandfather suffered from bipolar disorder. I decided not to rush into a diagnosis of depression.

Because of his addiction, Uncle Jonathan was regularly sent for drug tests. They were always negative, and Jonathan himself wondered why he should accept something that makes the mood jump even more. I was amazed at his insight and believed him.

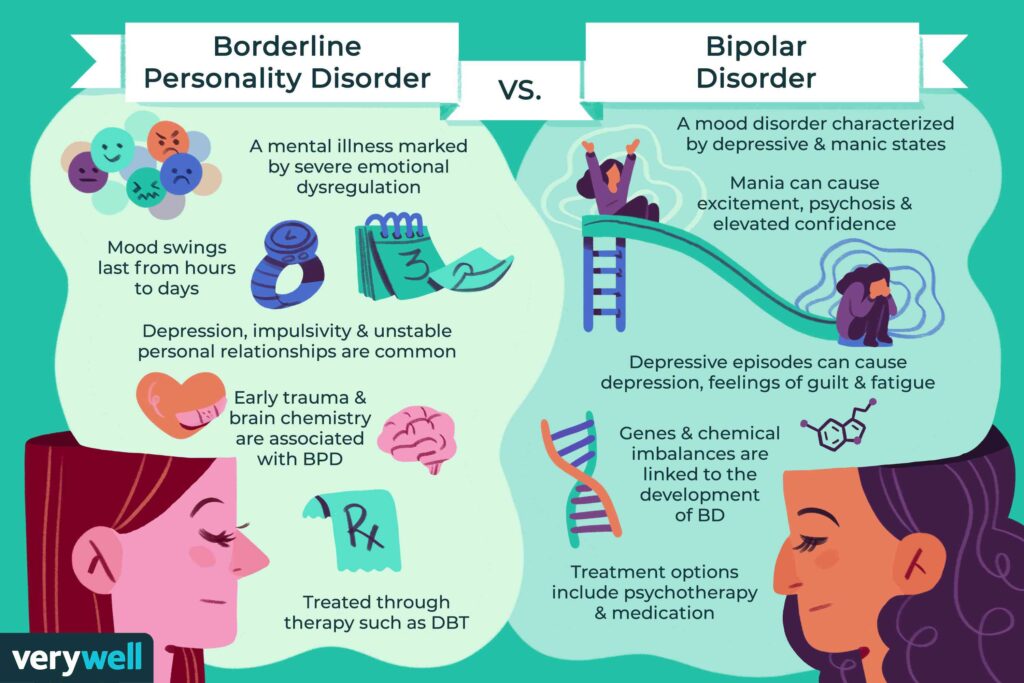

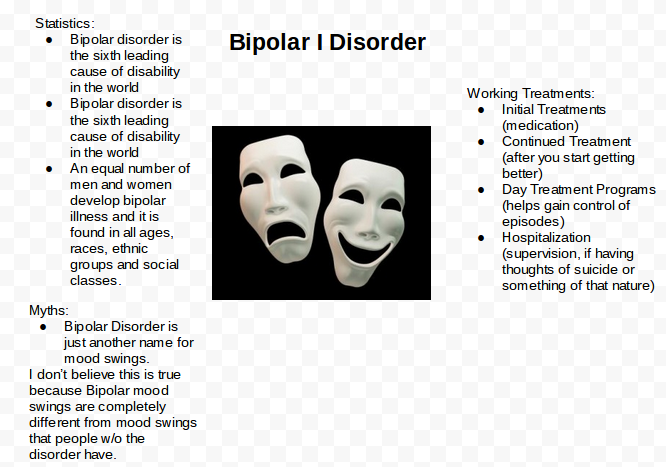

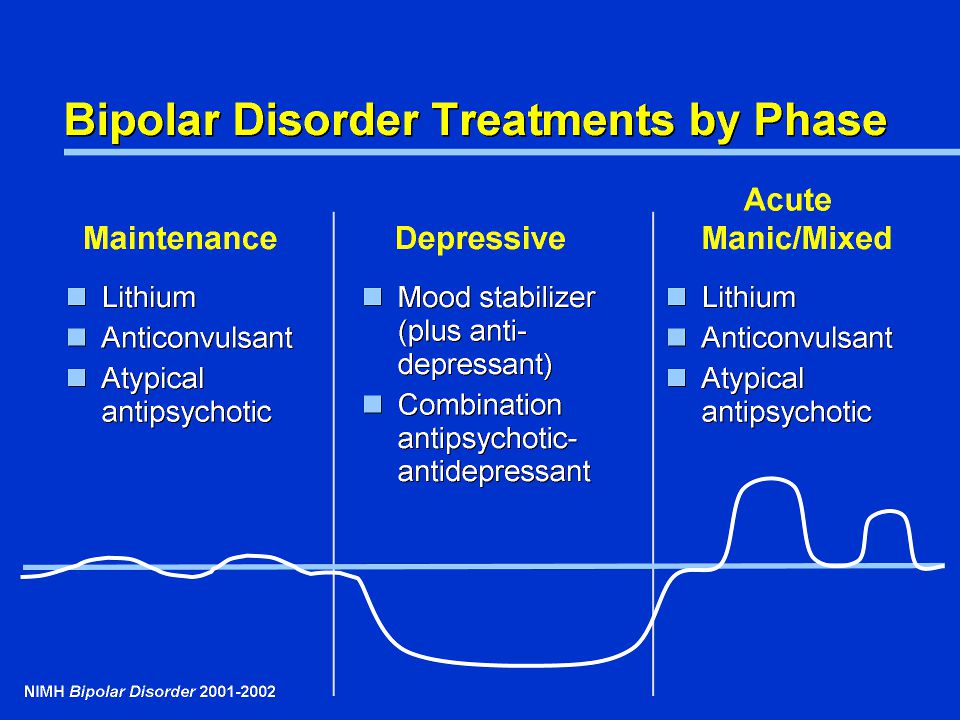

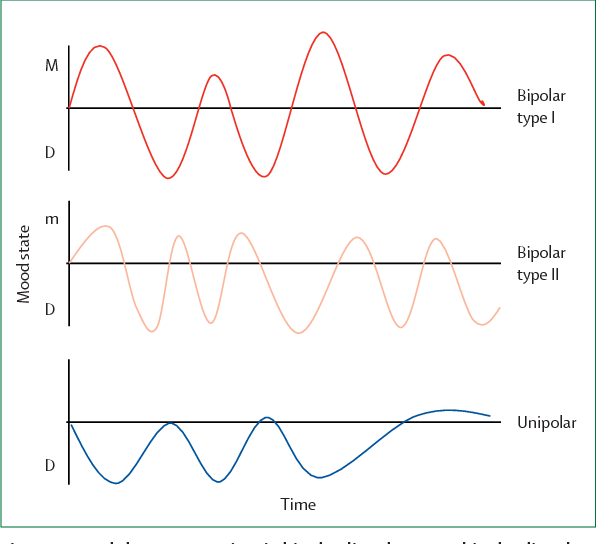

Sudden outbursts of anger could speak of irritability as one of the main signs of deep depression, especially in children. But they just as well apply to the symptoms of bipolar disorder, which is often inherited and often manifests itself in adolescence. At first, bipolar disorder is almost indistinguishable from the so-called unipolar depression, during which the mood only falls. However, in bipolar disorder, depression alternates with a brisk, or activated, state of mania. In mania, adults and adolescents are wasteful and irrational, they suffer from severe mood swings, they feel an exaggerated sense of self-importance and power, a reduced need for sleep, and an increased desire for both food and sex.

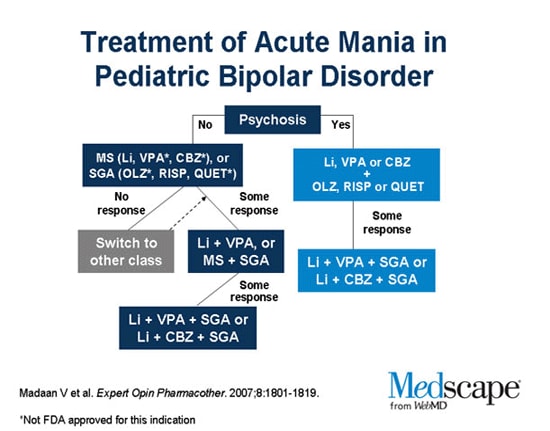

Distinguishing unipolar disorder from bipolar disorder is important in order to select the appropriate course of treatment, which is why I often consult about this diagnosis. In Jonathan's case, I even brought in two colleagues, and they both agreed that bipolar disorder was very likely.

From the point of view of the structure of the brain, bipolar disorder is characterized by severe dysregulation: it is difficult for a person to maintain emotional balance due to problems with coordination and stability of the brain channels responsible for mood.

Subcortical areas influence our feelings and mood, shape motivation and behavior. The prefrontal cortex, located just above the subcortical regions, controls our ability to balance our emotions.

Regulatory channels in the brain can fail for a number of reasons, some of them related to genetics or constitutional, that is, unacquired aspects of temperament.

According to one of the current theories, in people with bipolar disorder, there are structural features of the connection of the regulatory prefrontal channels with the lower limbic lobes, which are responsible for the formation of emotions and mood.

Heredity, the consequences of infection or exposure to neurotoxins determine this anatomical difference, leading in some cases to spontaneous activation of the lower limbic areas. Being in an activated state, these subcortical channels increase the speed of thinking, provoke an increase in appetite and general arousal.

To an outside observer, mania often seems attractive and pleasant, and the patient himself experiences periods of euphoria, but these are always replaced by uncontrolled anxiety and irritability, causing despair. And when dysfunction in the subcortical channels moves in the opposite direction, thoughts slow down, mood decreases, such vital functions of the body as sleep and appetite are disturbed, and a person sometimes almost completely refuses to communicate. Improper prefrontal regulation fails to bring the two extremes of the emotional range into balance, and manic and depressive states cause great suffering.

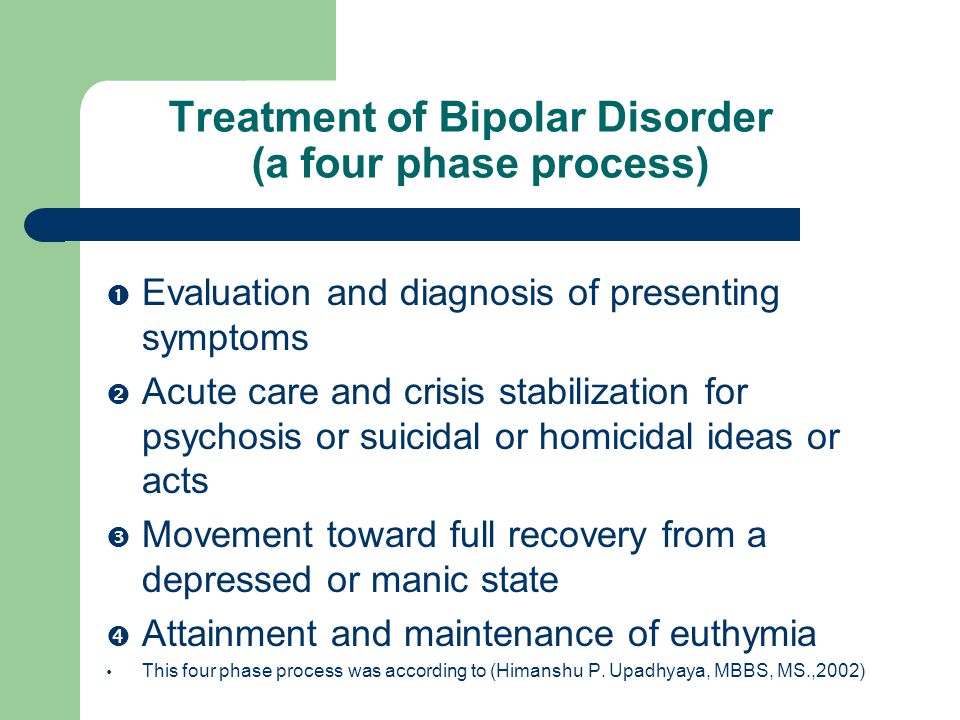

This is usually treated with medication, but the side effects of drugs used for bipolar disorder (called mood stabilizers) are much more severe than drugs for unipolar depression. Therefore, child psychiatrists are extremely cautious and reluctant to choose medications designed for the long-term use required by a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Therefore, child psychiatrists are extremely cautious and reluctant to choose medications designed for the long-term use required by a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Furthermore, if a person with undiagnosed bipolar disorder initially exhibits symptoms of depression and is given antidepressants, in some cases this clinical intervention provokes manic episodes or causes an intense form of the disorder in which cycles of manic and depressive states alternate very quickly, and sometimes a mixed state occurs, when both extremes appear at the same time.

With the above in mind, I asked Jonathan's parents to come with him, and we openly discussed the choice of treatment. Many physicians focus on the idea of chemical imbalance and how various neurotransmitters such as serotonin and noradrenaline cause euphoria or depression depending on their levels.

It seems to me that an in-depth discussion of emotional regulation in the brain gives patients a more complete picture of the problem and ways to solve it. I showed Jonathan and his parents a handy brain model and described the critical role of the prefrontal cortex. I also added that we are unable to explain why Jonathan's neural pathways are malfunctioning.

I showed Jonathan and his parents a handy brain model and described the critical role of the prefrontal cortex. I also added that we are unable to explain why Jonathan's neural pathways are malfunctioning.

According to one theory, depression blocks the ability of the brain to adapt to what is happening. (Remembering the river of integration, this state corresponds to a bank of internal stiffness.) Antidepressants, such as the well-known selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), and mood stabilizers, such as lithium salts, often help turn on neuroplasticity.

They change how neurotransmitters work and enhance the brain's ability to learn from experience, as in psychotherapy.

The combination of medication and psychotherapy is most often excellent for the treatment of serious mood disorders .

Sometimes psychotherapy alone can affect how the brain works. I told Jonathan and his family that, according to recent research, chronic recurrent episodes of depression are prevented by therapy based on the ancient mindfulness meditation technique.

True, I did not find similar published work on the use of mindfulness in patients with bipolar disorder, but I had reason to be cautiously optimistic. Controlled clinical studies have shown that mindfulness is an important ingredient in the successful treatment of many chronically dysregulated diseases, including anxiety disorder, drug addiction, and borderline personality disorder.*

A University of California study of obsessive-compulsive disorder that also looked at mindfulness meditation was one of the first to find that psychotherapy does induce changes in the brain. In addition, in a pilot study by our Mindfulness Research Center, we found that mindfulness meditation training is extremely effective for adults and adolescents with attention problems.

-

* Borderline personality disorder is a disease characterized by impulsivity, low self-control, emotional instability, unstable connection with reality, high anxiety and desocialization. Note. transl.

Note. transl.

A conscious approach to the transformation of consciousness

Mindfulness is often defined as the ability to deliberately focus on the present moment without being judged. Widespread both in the East and in the West, both in antiquity and in the modern world, this practice helps people to gain well-being. Sometimes when people hear the word "mindfulness" they immediately think it's about religion. In fact, mindfulness exercises are just a biological process that promotes well-being. This is a peculiar form of "brain hygiene" that has nothing to do with religion, although it is encouraged in many religions.

I didn't know if Jonathan's disorder would be amenable to this type of treatment, but the family's willingness to try and their concern about drug side effects convinced me that it was worth trying. I got the consent of Jonathan and his parents, and we agreed that if mindfulness meditation did not stabilize Jonathan's mood within a few weeks, we would move on to medication.

Attention concentration, brain transformation

I explained to Jonathan that brain structures change in response to experience, and new mental skills are developed through purposeful effort, conscious attention, and concentration.

New experiences stimulate neuronal activity, which in turn leads to the production of proteins that create new connections between neurons, and myelin, a lipid sheath that speeds up the transmission of nerve impulses. This process is called neuroplasticity.

In addition to concentrated attention, there are other factors that contribute to neuroplasticity: aerobic exercise and emotional arousal.

Apparently, aerobic exercise is useful not only for our cardiovascular and musculoskeletal, but also for the nervous system. We learn more effectively when we are physically active.

When we focus on something, our attention mobilizes cognitive resources, directly causing the activity of neurons in the corresponding areas of the brain.

Studies have also shown that animals that were rewarded for hearing sounds had significantly larger auditory centers in the brain, while those rewarded for seeing visual images had larger visual centers. This means that neuroplasticity is activated not only by sensory impulses, but by the very attention and emotional arousal. The latter is observed when animals are rewarded for what they hear or see, or when we are doing something important from our point of view.

If we are not emotionally involved, the experience becomes less memorable and transformation in brain structures is less likely.

Evidence of structural transformation of the brain as a result of conscious concentration of attention was also obtained in the course of computed tomography of violinists. On the tomograms, there is a huge jump in the growth and expansion of the areas of the cortex responsible for the left hand: it is she who moves along the strings with great accuracy and speed. Other studies have shown that the hippocampus responsible for spatial memory is enlarged in taxi drivers.

Other studies have shown that the hippocampus responsible for spatial memory is enlarged in taxi drivers.

Attentive brain

I wanted to teach Jonathan to focus his mind on a specific task . But what specifically stimulates the mindfulness technique? Why does it help with such a wide range of problems and will it have a positive effect on Jonathan's condition?

Modern clinical research, two thousand years of contemplative practice, and my own experience indicate that mindfulness is a form of mental activity that trains the mind to become aware of mindfulness and forces one to pay attention to one's own intentions.

Mindfulness requires focusing on the present moment without harsh judgments or hasty reactions. She teaches to observe oneself: people who practice it are able to describe their state of mind in words.

At the center of this process, it seems to me, lies a form of attunement to internal processes, which allows a person to become his own best friend. And just as our attunement to children forms a healthy and strong attachment in them, our attunement to ourselves lays the foundation for the stability and flexibility of consciousness.

And just as our attunement to children forms a healthy and strong attachment in them, our attunement to ourselves lays the foundation for the stability and flexibility of consciousness.

The act of attunement—internal in case of mindfulness and external in creating attachment—ensures healthy fiber growth in the medial prefrontal cortex.

Realizing this fact, I soon read that the area of the medial prefrontal cortex is indeed thicker in mindful meditation practitioners.

The following hypothesis prompted me to suggest this technique to Jonathan: the practice would help him increase and strengthen the parts of the brain that regulate mood, stabilize his consciousness and allow him to achieve emotional balance and stability .

I didn't think he had an insecure attachment as a child, but rather that mindfulness directly stimulates the growth of a cluster of neurons called resonance channels, which include the medial prefrontal cortex.

They give us the ability to tune in to other people and regulate our own behavior. This is where the connection between attunement and regulation comes into play: internal and interpersonal forms of attunement lead to the growth of regulatory channels in the brain. When we reach a state of alignment—internal or interpersonal—we become more balanced.

Adolescent brain and prefrontal cortex

Jonathan wanted to get rid of his unpleasant symptoms as soon as possible. Adolescence is not easy without them: it is accompanied by changes in the body, a nascent and sometimes overwhelming sense of sexuality, changes in self-identification and relationships, high demands at school, uncertainty about the future and stress in the family that comes with an understanding of inevitable independence.

The teenage brain is in constant motion. The prefrontal regions, including the medial regions, do not fully mature until age twenty-five or later.

The brain is affected not only by the most powerful hormonal changes, but also by genetically programmed neural thinning - the removal of neural connections, which helps to “polish” various channels: to keep the used ones and get rid of the unnecessary ones in order to make the brain more adapted to solving current problems and efficient.

The normal process of brain restructuring is enhanced under stress, which reveals existing or provokes new problems. Because of this, the functions of the medial prefrontal cortex - from the modulation of fear to empathy and ideas of moral norms - begin to work unpredictably, and the regulation of one's own emotions is problematic for any teenager.

However, in Jonathan's case, mood dysregulation was outside the average for puberty. Most teenagers do not reach suicidal thoughts. Because of the painful episodes, Jonathan developed self-doubt. He believed that now he could not rely on a constantly failing consciousness. In my understanding, he needed to become his own best friend. If Jonathan could be helped to grow integrative fibers in the medial prefrontal cortex, it would be easier for him to reach the state of FACES flow. The integration of awareness would stabilize him.

If Jonathan could be helped to grow integrative fibers in the medial prefrontal cortex, it would be easier for him to reach the state of FACES flow. The integration of awareness would stabilize him.

I explained all this to Jonathan and reminded him that regular exercise, proper nutrition, and adequate sleep provide the basis for neuroplasticity. It is surprising how often the basic principles of a healthy brain are ignored.

Exercise as a treatment is greatly underestimated: aerobic exercise not only releases endorphins that positively affect mood, but also increases the number of connections between neurons. Regular and balanced nutrition reduces mood swings. And sleep is a universal remedy. With the latter, Jonathan had problems, so a systematic approach was needed.

Sleep Hygiene involves a soothing ritual before going to bed. For an hour or two, you should turn off all digital devices, do quiet activities: take a bath, listen to soothing music, read a book, and minimize the use of caffeine and other stimulants as the evening approaches. All this relaxes both the body and the mind.

All this relaxes both the body and the mind.

With these basic rules of healthy living in place, Jonathan and I moved on to specific techniques for integration.

We have started classes aimed at training mindfulness skills. The idea was that these techniques create a temporary state of brain activation each time we repeat them. With regular repetition, short-term conditions become long-term and permanent. Thus, through practice, mindfulness becomes a character trait.

Here is a simple diagram I drew for Jonathan to give him a visual representation of the attention span. I called it the wheel of awareness.

Wheel of awareness

Imagine a bicycle wheel with an axle in the center and spokes radiating from it to the rim.

- The rim is everything we can pay attention to: thoughts and feelings, perceptions of the world around us, or sensations in the body.

- Axis is the inner space of consciousness from which awareness emanates.

- Spokes indicate the direction of attention to a specific part of the rim.

Awareness is focused on the axis of the wheel, and we focus on various objects - points on the rim. The axis serves as a metaphor for the prefrontal cortex.

To understand how this works, let's move on to the first exercise I suggested to Jonathan.

I decided to use insight meditation with Jonathan because, firstly, I myself learned it from experienced teachers, and secondly, most of the relevant research was conducted on its basis.

Mindful Attention Exercise: Concentration on Breathing

Several of my patients reported that after these exercises they became less anxious, they had a deeper sense of clarity, security and well-being. I was hoping Jonathan would have the same reaction.

Fortunately, he responded well to this session and did mindful meditation daily, at first for five to ten minutes at a time. When he was distracted, he would simply capture the moment and carefully direct his attention back to his breath.

When he was distracted, he would simply capture the moment and carefully direct his attention back to his breath.

Mindfulness Training and Consciousness Stabilization

Jonathan was in the school film club, and somehow he needed to make short documentaries about different parts of the city. He showed me one of his films, and I was struck by how cleverly he used the angle of the camera to convey the mood and texture of the city where we were both born and raised.

His eyes sparkled with pride when he noticed how much I liked his work. Then I told Jonathan about the camera lens and tripod metaphor.

The lens of the camera is our ability to perceive our own consciousness. Without a tripod, consciousness trembles all the time, like amateur videos shot with a handheld camera.

Jonathan instantly understood the point of the comparison: the blurry footage was similar to the feeling of being lost that his mood swings caused him. He also liked the image of the ocean from the previous exercise. He identified himself with a cork floating on a troubled sea. Regardless of which metaphor is closer to you - the wheel, the lens or the sea - they have the same meaning . Deep within us, there is a point of observation, objectivity, and openness. It is the receptive center of our consciousness, the serene depth of the inner sea. From there, Jonathan saw how reflective awareness changes the way the brain works and its structure.

He identified himself with a cork floating on a troubled sea. Regardless of which metaphor is closer to you - the wheel, the lens or the sea - they have the same meaning . Deep within us, there is a point of observation, objectivity, and openness. It is the receptive center of our consciousness, the serene depth of the inner sea. From there, Jonathan saw how reflective awareness changes the way the brain works and its structure.

Let's look at this process using the three pillars of awareness: observation, objectivity and openness .

Mindfulness Tripod Three Legs

Observant

If I may say so, then first of all Jonathan needed to become aware of his awareness and observe the concentration of attention. When he began to focus on his breathing, he found himself constantly distracted and lost in thoughts, feelings, and memories. However, this did not mean that he was meditating incorrectly.

The meaning of the exercise is to notice moments of distraction and again focus on the object. It is like strengthening muscles: as we bend and unbend the arm, tensing and relaxing the biceps, we concentrate attention, and when it is dispersed, we return it again. This practice emphasized Jonathan's goal - in this case - concentration on the breath. Holding on to a goal is the foundation of all mindfulness practices, whether we choose to focus on posture and movement, breathing, a candle flame, or any other object. Gradually, Jonathan managed to develop the skill of conscious attention - to set a goal and stick to it.

As an add-on, Jonathan agreed to keep a diary of daily activities, noting mood swings, meditations done or not done, and aerobic exercise. This was another opportunity to develop the ability to observe internal and external impressions and think about the mechanisms of the work of consciousness.

As Jonathan began his notes, we quickly discovered that he lacked confidence in the capabilities of his mind.

Almost everyone who tries meditation finds that thoughts and feelings constantly interrupt attempts to concentrate, even after several years of practice. At such moments, Jonathan was overcome with strong irritation, and he wrote that he was losing control. He showed me excerpts from his diary, where self-abasement bordered on unwillingness to live on. But there were also gaps of something new: “My father asked me not to put the music so loudly, and I exploded. He's always picking on! But today I was able to follow the outburst of anger as if from an observation tower: I saw the smoke coming, it made me feel bad, but I couldn’t stop.” According to him, the next day he calmed down, but still felt that consciousness had “betrayed” him again.

The distance that allows you to observe your own mental activity is an important first step towards the regulation and stabilization of consciousness. Jonathan began to realize that he could ride out such a storm in the prefrontal cortex without being swayed by brainwaves from other parts of the brain. It was a good start.

It was a good start.

Objectivity

If you are relatively new to the training of conscious attention, it will be useful for you to compare it with mastering a musical instrument. At first, you concentrate on certain elements: the strings, the keys, or the mouthpiece. Then you work on basic skills: play scales or chords, consistently focusing on each note. Purposeful and regular practice allows you to develop a new ability. It actually strengthens the areas of the brain required for a new activity.

Mindfulness training also helps to develop the ability to set a goal and go towards it, only consciousness acts as a musical instrument. This is developed through observation and contributes to the stabilization and retention of attention. The next step is to learn to distinguish the quality of awareness from the object of attention.

Jonathan and I started this stage by "scanning" the body. He needed to lie on the floor and concentrate on the part of the body that I called. We moved in succession from toes to nose, stopping periodically to allow him to notice specific sensations. When Jonathan was distracted, he needed to notice what was distracting him, let it go and focus again, just like he did with his breathing. Immersion in bodily sensations directed his attention to a new spot on the rim of the wheel of awareness. He found areas of tension or relaxation and noticed what he was distracted by, moving inside the sector of the wheel where the sixth sense is located.

We moved in succession from toes to nose, stopping periodically to allow him to notice specific sensations. When Jonathan was distracted, he needed to notice what was distracting him, let it go and focus again, just like he did with his breathing. Immersion in bodily sensations directed his attention to a new spot on the rim of the wheel of awareness. He found areas of tension or relaxation and noticed what he was distracted by, moving inside the sector of the wheel where the sixth sense is located.

Then I taught Jonathan motion meditation: he took twenty slow steps around the room, concentrating on the feet or lower legs, and using a similar approach. When Jonathan realized he was distracted, he simply brought his attention back. This set the stage for objectivity. The object of concentration changed with each practice, but the feeling of awareness remained the same.

Here is one of Jonathan's diary entries of that time: “I realized an amazing thing - I directly feel this change - I have thoughts and feelings, sometimes strong and bad. I used to think that this was all of me, but now I understand that these are just impressions that do not define me. Another note described how Jonathan once got angry with his brother. “I was just beside myself with anger. But then I forced myself to go outside. Walking in the yard, I practically felt this border in my head: one part of the consciousness saw and understood everything, and the other was under the heel of the senses. It was very strange. I watched the breath, but I'm not sure it's not useless. Later, I seem to have calmed down. I felt like I stopped taking my own feelings too seriously.”

I used to think that this was all of me, but now I understand that these are just impressions that do not define me. Another note described how Jonathan once got angry with his brother. “I was just beside myself with anger. But then I forced myself to go outside. Walking in the yard, I practically felt this border in my head: one part of the consciousness saw and understood everything, and the other was under the heel of the senses. It was very strange. I watched the breath, but I'm not sure it's not useless. Later, I seem to have calmed down. I felt like I stopped taking my own feelings too seriously.”

For homework, Jonathan alternated between breathing, body scanning, and moving meditation. But at some point, his irritation returned in a new form. He said that sometimes he gets a severe "headache", a kind of "voice" telling him what he should feel and do and that he is not meditating correctly and generally good for nothing.

I reminded Jonathan that these judgments are just the activity of his mind, and convinced him that he was not alone: many people have an inner judging and critical voice. But for the next step, Jonathan needed to stop slavishly obeying this voice. It seemed to me that he was ready for such a challenge.

But for the next step, Jonathan needed to stop slavishly obeying this voice. It seemed to me that he was ready for such a challenge.

Openness

Observation allowed Jonathan to focus on the nature of intention and attention, which are the driving forces of mental activity. Objectivity taught him to distinguish awareness from brain activity. But now the storm activity has manifested itself in the form of expectations and “I have to” statements that inevitably imprison us. And attempts to force yourself to change feelings do not lead to anything. Open awareness means that we accept them but do not give in to them.

Don't you think it's strange that Jonathan came to me wanting to be different, and I'm teaching him to accept himself as he is? There is one difference: our desire to overcome experience creates internal tension, and in doing so, we make ourselves suffer. But instead of breaking into the inner world and saying, “No, don't do it!”, we are able to accept reality and see what happens. Oddly enough, every time people realize that this helps them change. It is better to approach the inner world with openness and readiness to accept it, and not with prejudice. Imagine the following situation: one of your friends began to talk about his problems. Surely you would listen to him, ask him to tell everything that is on his mind, and in addition to sincere interest, you would offer to lend a shoulder. This is what openness means – being attuned to the current situation, being kind to yourself and supporting yourself while remaining receptive and refraining from hasty reactions and judgments.

Oddly enough, every time people realize that this helps them change. It is better to approach the inner world with openness and readiness to accept it, and not with prejudice. Imagine the following situation: one of your friends began to talk about his problems. Surely you would listen to him, ask him to tell everything that is on his mind, and in addition to sincere interest, you would offer to lend a shoulder. This is what openness means – being attuned to the current situation, being kind to yourself and supporting yourself while remaining receptive and refraining from hasty reactions and judgments.

Except Jonathan hasn't learned to be kind to himself yet. For example, he would concentrate on his breathing, get distracted, and immediately begin to think that he was meditating incorrectly. I urged Jonathan to treat harsh self-criticism as just another mental activity and suggested calling it evaluation and switching back to breathing. Jonathan liked the definition of "doubt" better.

Instead of succumbing to endless "shoulds", through openness we gradually learn to accept ourselves and our experiences. But first of all, it is necessary to understand when exactly we ourselves act as our own jailers.

Consciousness stabilized

Jonathan began to notice some changes in himself. When it was not easy for him, he went to run or ride a bicycle in order to find some way out of the condition that gripped him. Physical activity helped him calm his body, restore awareness, and restore balance. A few weeks into our work, Jonathan described a new experience for him. He began to feel raging thoughts and strong emotional outbursts with greater clarity: he managed not to give in to them. His parents were surprised and pleased that he seemed to have found a way to calm these storms.

Here is what Jonathan wrote one night in his diary: “This afternoon I had a fight with my mother. I came home from school late and she just lashed out at me and she was so angry. I went to my room. I wanted to kill myself. I sat on the bed and wondered what the point was. Then a feeling of absolute helplessness swam through my head, as if it were a raft, a boat, or a piece of wood. But if earlier I was always in a boat and sailed away, this time I was somewhere else. I saw that the raft was just a feeling of not being able to do anything to get out. But by letting the boat just be in my head without getting into it, I didn't feel so guilty about it. And then she vanished." Jonathan and I discussed how the "boat" made him understand that he shouldn't be floating aimlessly on the waves of desperation. He realized that he was able to prevent the "attack" of feelings. Jonathan was also convinced that the observation of the inner world and the willingness to accept him was taken out of a depressed state. Considering thoughts from afar, he did not succumb to them. In many ways, Jonathan's experience confirmed the results of research, according to which people who were trained in mindfulness meditation showed a change in the brain towards a state of approach.

I went to my room. I wanted to kill myself. I sat on the bed and wondered what the point was. Then a feeling of absolute helplessness swam through my head, as if it were a raft, a boat, or a piece of wood. But if earlier I was always in a boat and sailed away, this time I was somewhere else. I saw that the raft was just a feeling of not being able to do anything to get out. But by letting the boat just be in my head without getting into it, I didn't feel so guilty about it. And then she vanished." Jonathan and I discussed how the "boat" made him understand that he shouldn't be floating aimlessly on the waves of desperation. He realized that he was able to prevent the "attack" of feelings. Jonathan was also convinced that the observation of the inner world and the willingness to accept him was taken out of a depressed state. Considering thoughts from afar, he did not succumb to them. In many ways, Jonathan's experience confirmed the results of research, according to which people who were trained in mindfulness meditation showed a change in the brain towards a state of approach. This allows you to go towards problem situations, rather than avoid them. This is how emotional stability is formed.

This allows you to go towards problem situations, rather than avoid them. This is how emotional stability is formed.

Jonathan later wrote: “I know it sounds stupid, but my outlook on life has changed. What used to seem like a personification of my personality turned out to be just a part of what was happening. And strong feelings are just experiences that don't define me."

I was very moved by his discoveries and marveled at Jonathan's ability to express such profound thoughts. Now we needed to hone this newfound ability in order to re-route the energy and information flows and prevent strong emotional overflows. Having learned to use the skills of self-observation, Jonathan was ready to learn the techniques that would allow him to do something. I showed him the basic ways to relax. I suggested that he choose a quiet place, imaginary or real, to represent him at critical moments. We combined this method with the grounding sensation that Jonathan achieved by simply watching his body or breathing. Over time, Jonathan learned to prevent impending emotional outbursts by noticing changes in his body: palpitations, abdominal discomfort, tense fists - and this alone helped to smooth out their intensity. Jonathan experienced for himself how mindful attention contributes to mental balance.

Over time, Jonathan learned to prevent impending emotional outbursts by noticing changes in his body: palpitations, abdominal discomfort, tense fists - and this alone helped to smooth out their intensity. Jonathan experienced for himself how mindful attention contributes to mental balance.

In his diary he wrote: “By observing my feelings, I can change what they do to me. Previously, they had explosive power and lasted for hours. Now, after a few minutes, I see them thrashing around, and when I decide not to take them to heart, they just dissolve. It's pretty weird, but for the first time in my life, I'm starting to believe in myself."

For these changes, it was necessary to accept the situation and let it go until the consciousness calmed down. It's a hard road. Emotional storms were a huge problem in Jonathan's life, but they motivated him to create a safe haven within his mind.

What transformations did Jonathan have? We don't have CT scans to be sure, but it seems to me that from a neurological standpoint, Jonathan has built up integrative fibers in the medial prefrontal cortex. He accomplished this over several months of intensive work, with two sessions a week and almost daily aerobic exercise and mindfulness practice. A new way for him to focus attention and integrate consciousness became possible due to the expansion of the medial prefrontal cortex and the buildup of GABA-inhibiting fibers, which calmed the storms raging in the subcortical regions. This kept his irritable limbic amygdala quiet, so the GABA gel didn't involve his brainstem in the maddening fight-run-freeze process. Also, most likely, Jonathan began to use his left hemisphere more and be in a state of approach. Jonathan has learned to coordinate and balance his brain activity in new and more adaptive ways. Now he could "sit out" the storm without succumbing to overwhelming manifestations of consciousness. The mental training not only eased the symptoms of mood swings, but also made Jonathan emotionally stable: “I feel very clear. I'm practically a different person. Now I'm probably stronger.

He accomplished this over several months of intensive work, with two sessions a week and almost daily aerobic exercise and mindfulness practice. A new way for him to focus attention and integrate consciousness became possible due to the expansion of the medial prefrontal cortex and the buildup of GABA-inhibiting fibers, which calmed the storms raging in the subcortical regions. This kept his irritable limbic amygdala quiet, so the GABA gel didn't involve his brainstem in the maddening fight-run-freeze process. Also, most likely, Jonathan began to use his left hemisphere more and be in a state of approach. Jonathan has learned to coordinate and balance his brain activity in new and more adaptive ways. Now he could "sit out" the storm without succumbing to overwhelming manifestations of consciousness. The mental training not only eased the symptoms of mood swings, but also made Jonathan emotionally stable: “I feel very clear. I'm practically a different person. Now I'm probably stronger. "

"

Within six months of our working together, Jonathan's symptoms had virtually disappeared. He behaved more at ease and carefree. I would say that he was comfortable in his body. “I just don’t take all these feelings and thoughts too close to my heart, and they don’t evoke such strong emotions in me anymore!” he said. We continued to strengthen his new skills. During our last meeting, after a year of therapy, Jonathan stood up to shake my hand, and I saw again the sparkle in his eyes that had so often been hidden by a mask of anxiety and fear. Now his gaze was straight, his face relaxed, and his handshake confident. He has grown seven or eight centimeters since we first met, which seemed like an eternity ago.

After graduating from high school, Jonathan went to college in another city. Many years have passed, and recently I happened to meet his parents in a shop next door. They told me that he was doing great and the mood swings weren't coming back. He studies cinema and psychology.

Daniel Siegel. Mindsight: The New Science of Personal Transformation

- Previous article Treatment of childhood trauma

- Next article Spring aggravation: how not to become discouraged

At different poles: what you should know about bipolar disorder and why people with such a diagnosis and their loved ones should not lose hope How to keep from overprotection or vice versa from a too detached position? What is better - to support as much as possible or to give a person space and time to try to cope with this on his own, so that later it would be easier for him?

— Here we need both support and responsibility of the person himself. Both of these are necessary. Another question is what people understand by support. If we take the case of Kanye, then there was such an episode when he left somewhere, and Kim complained that we want to support you, but you ignore us and are not going to receive this support (Editor's note: just as part of his campaign, Kanye was in Wyoming and did not answer Kim's calls). And the whole family flaps its wings and shouts that no, we won’t let you be alone, we will support you. This very clearly shows how often we do not hear people and do not understand what kind of support they really need from us. Sometimes you have to get away from a person.

And the whole family flaps its wings and shouts that no, we won’t let you be alone, we will support you. This very clearly shows how often we do not hear people and do not understand what kind of support they really need from us. Sometimes you have to get away from a person.

But one must understand that bipolar disorder stigmatizes the family too.

It is very difficult to accept this whole situation. If it is not easy for a person himself, although he experiences all the symptoms of the disease on himself, then it is more difficult for the family in a certain sense, because they do not know what is happening to him, how he feels it and how much he can control. The life of loved ones, of course, often turns into hell. Especially if the disorder is intense, with large manic episodes, it is emotionally very difficult. But like Kanye, when Kim tried to lock him up and send doctors to see him, unless an adult wants to see a doctor, he can't be forced to do so. This is a definite violence.

— What to do in such cases, how to act and convince?

— The main way in case a person does not want to go to the doctors is, of course, enlightenment and persuasion, but soft, in the form of dialogue, not dictate. To do this, family members themselves must be enlightened. And another important aspect: relatives also need support to have a resource for such communication. There are now support groups specifically for relatives of people with bipolar disorder. That is, at the first stage, when the disease has not yet been diagnosed or when there is a diagnosis, but treatment is not carried out, it is the close environment that suffers, and not the patient himself.

But this suffering needs to be dealt with, and this may also require therapy.

Otherwise, they will exhaust their resources and will no longer be able to support in any way, or they can even harm their loved one who has bipolar disorder, by forcing them to undergo treatment too much, by being overprotective. In a support group, relatives will be helped to form their position and strategy for communicating with the sick person, they will be taught how to organize their interaction with him without losing respect for him and without infringing on his human dignity and taking care of himself at the same time. Overprotection will not lead to anything good, but it can lead to codependency, the consolidation of the roles of rescuers and victims, and dysfunction of the family. But if you build the boundaries correctly, then this can lead the patient to realize responsibility for his illness and his life.

In a support group, relatives will be helped to form their position and strategy for communicating with the sick person, they will be taught how to organize their interaction with him without losing respect for him and without infringing on his human dignity and taking care of himself at the same time. Overprotection will not lead to anything good, but it can lead to codependency, the consolidation of the roles of rescuers and victims, and dysfunction of the family. But if you build the boundaries correctly, then this can lead the patient to realize responsibility for his illness and his life.

— You said that the diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder is the diocese of a psychiatrist, but still, if a person begins to suspect that something is wrong with him, it is still less scary to go to a psychologist, a psychotherapist than to a psychiatrist. Psychiatry sounds like a sentence to us. Does it make sense to turn to a psychotherapist all the same first, so that he directs, explains where to go next?

— Yes, it often happens. After all, here any person will be treated with understanding and without condemnation. And, of course, when a person sees that he has such good support, it will be easier for him to turn directly to a psychiatrist. A psychologist can not only direct, but offer to consult with a specialized specialist. The person may not agree, but as good contact with the psychologist develops, this situation may shift.

After all, here any person will be treated with understanding and without condemnation. And, of course, when a person sees that he has such good support, it will be easier for him to turn directly to a psychiatrist. A psychologist can not only direct, but offer to consult with a specialized specialist. The person may not agree, but as good contact with the psychologist develops, this situation may shift.

This can help both accepting the diagnosis and working with tracking one's conditions.

But even with this kind of therapeutic support - and this applies to all conditions in general that have a profound effect on a person's life - the patient may go into shock after visiting a psychiatrist and making a final diagnosis. Because usually the patient goes to a consultation with the hope that perhaps everything is not so bad. But if the doctor confirms the diagnosis and starts talking about treatment, then, of course, it is worth visiting a psychologist (psychotherapist) to cope with this shock. In general, by the way, it is better to start treating bipolar disorder, the sooner the better. Because if treatment is not started on time, then type II bipolar disorder, with a milder course, can turn into type I. And this is a more serious story. It is believed that the earlier treatment begins, the better the prognosis.

In general, by the way, it is better to start treating bipolar disorder, the sooner the better. Because if treatment is not started on time, then type II bipolar disorder, with a milder course, can turn into type I. And this is a more serious story. It is believed that the earlier treatment begins, the better the prognosis.

— Is there a chance to be cured or is it for life?

- Looks like not. At least for now. If BAD is diagnosed, then a good option is to enter a long-term remission. But we must understand that one psychiatrist or psychotherapist is not enough. There must be a good alliance between medical support and therapy. If we use computer terms for clarity, then, relatively speaking, medicines correct hard, equipment, so to speak, and the therapist corrects software - software. One will not work without the other. Therefore, if a person only visits a doctor, and does not also work with his attitudes, with his attitude towards his illness, then he has much more vulnerabilities and all kinds of provocations that can put him into a state of stress, but he will not cope with it.