Learn native american culture

Essential Understandings | Native Knowledge 360°

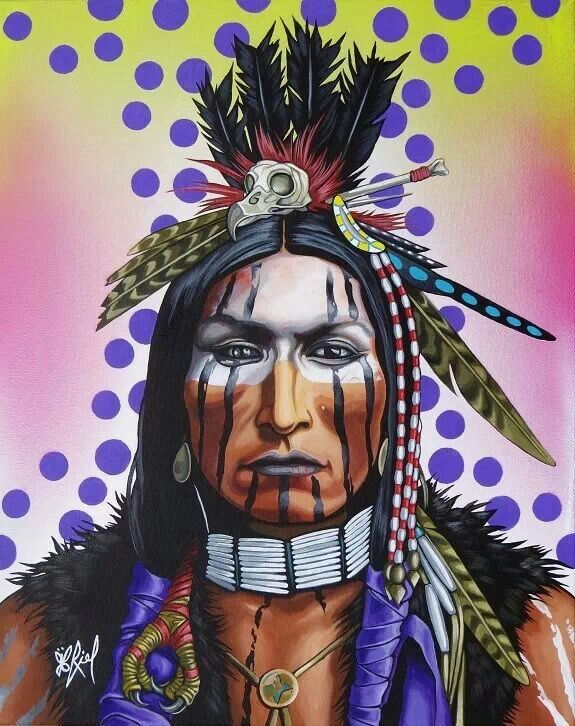

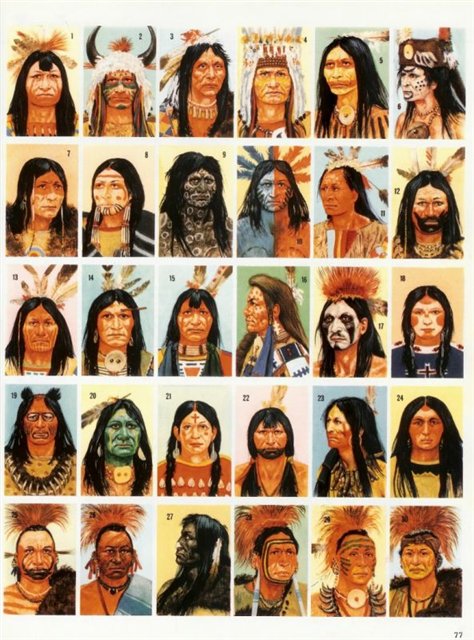

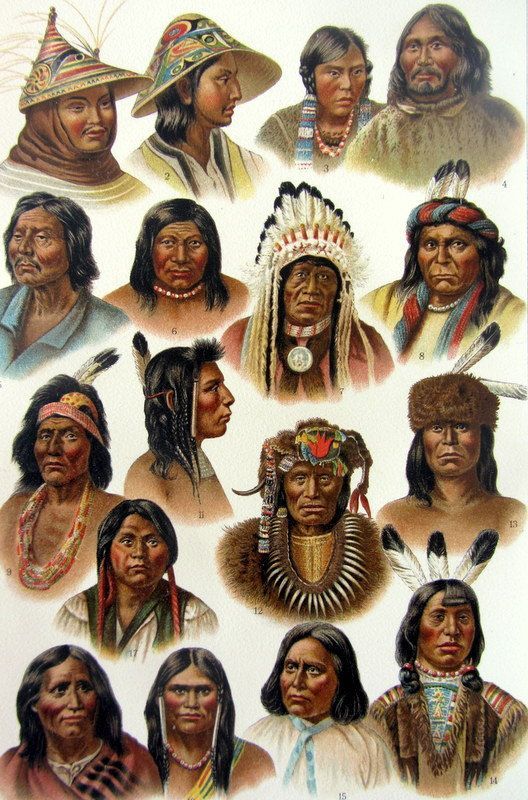

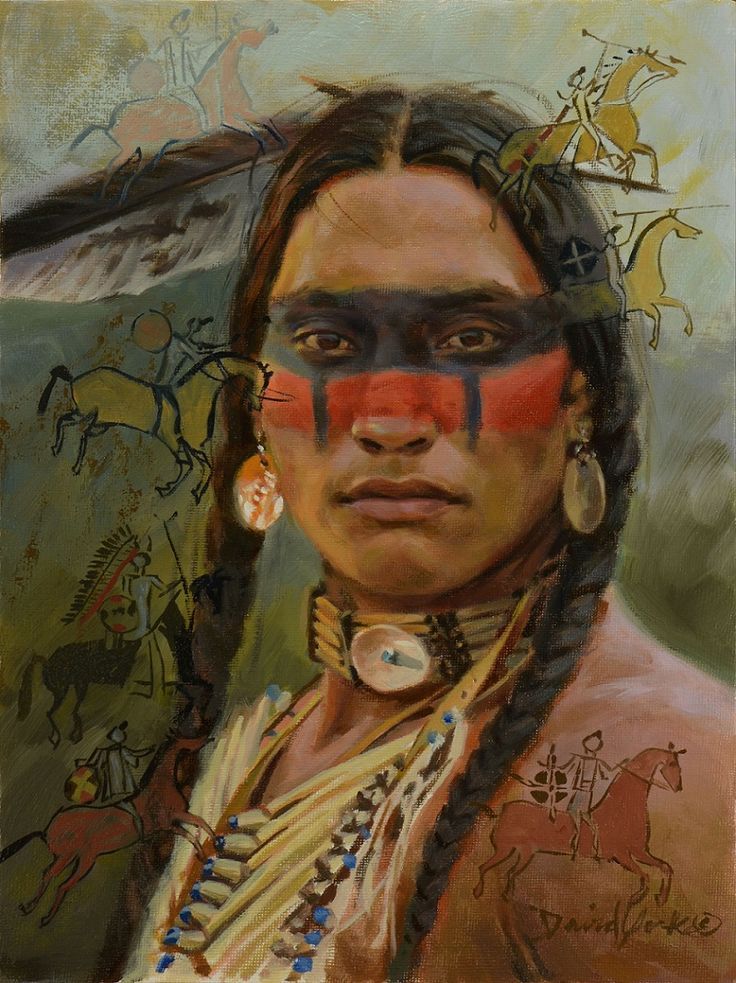

1. American Indian Cultures

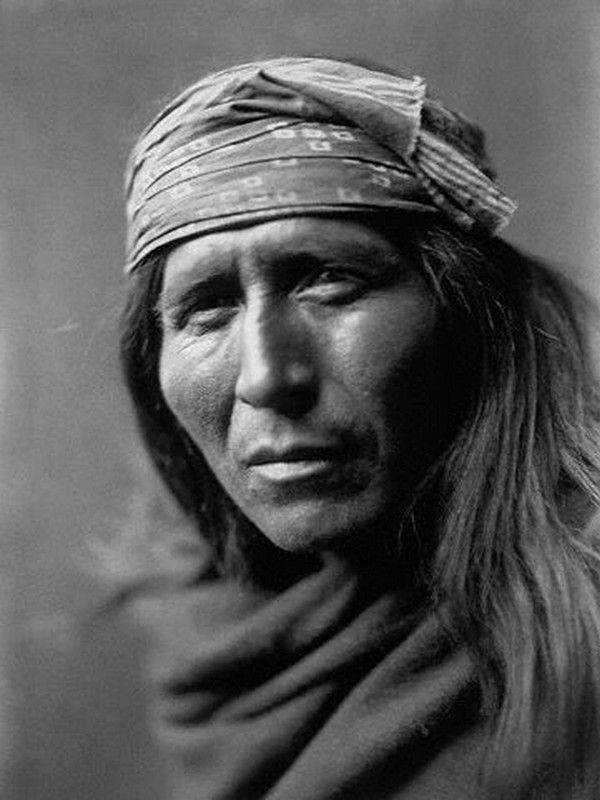

Culture is a result of human socialization. People acquire knowledge and values by interacting with other people through common language, place, and community. In the Americas, there is vast cultural diversity among more than 2,000 tribal groups. Tribes have unique cultures and ways of life that span history from time immemorial to the present day.

Key Concepts:

- There is no single American Indian culture or language.

- American Indians are both individuals and members of a tribal group.

- For millennia, American Indians have shaped and been shaped by their culture and environment. Elders in

each generation teach the next generation their values, traditions, and beliefs through their own tribal

languages, social practices, arts, music, ceremonies, and customs.

- Kinship and extended family relationships have always been and continue to be essential in the shaping of American Indian cultures.

- American Indian cultures have always been dynamic and changing.

- Interactions with Europeans and Americans brought accelerated and often devastating changes to American Indian cultures.

- Native people continue to fight to maintain the integrity and viability of indigenous societies. American Indian history is one of cultural persistence, creative adaptation, renewal, and resilience.

- American Indians share many similarities with other indigenous people of the world, along with many differences.

2. Time, Continuity, and Change

Indigenous people of the Americas shaped life in the Western Hemisphere for millennia. After contact, American

Indians and the events involving them greatly influenced the histories of the European colonies and the modern

nations of North, Central, and South America. Today, this influence continues to play significant roles in many

aspects of political, legal, cultural, environmental, and economic issues. To understand the history and

cultures of the Americas requires understanding American Indian history from Indian perspectives.

Today, this influence continues to play significant roles in many

aspects of political, legal, cultural, environmental, and economic issues. To understand the history and

cultures of the Americas requires understanding American Indian history from Indian perspectives.

Key Concepts:

- Many American Indian communities have creation stories that specify their origins in the Western Hemisphere.

- American Indians have lived in the Western Hemisphere for at least 15,000–20,000 years.

- The Western Hemisphere was laced with diverse, well-developed, and complex societies that interacted with one another over millennia.

- American Indian history is not singular or timeless. American Indian cultures have always adapted and

changed in response to environmental, economic, social, and other factors. American Indian cultures and

people are fully engaged in the modern world.

- American Indians employed a variety of methods to record and preserve their histories.

- European contact resulted in devastating loss of life, disruption of tradition, and enormous loss of lands for American Indians.

- Hearing and understanding American Indian history from Indian perspectives provides an important point of view to the discussion of history and cultures in the Americas. Indian perspectives expand the social, political, and economic dialogue.

- Indigenous people played a significant role in the history of the Americas. Many of these historically important events and developments in the Americas shaped the modern world.

- Providing an American Indian context to history makes for a greater understanding of world history.

3. People, Places, and Environments

For thousands of years, indigenous people have studied, managed, honored, and thrived in their homelands. These

foundations continue to influence American Indian relationships and interactions with the land today.

These

foundations continue to influence American Indian relationships and interactions with the land today.

Key Concepts:

- The story of American Indians in the Western Hemisphere is intricately intertwined with places and environments. Native knowledge systems resulted from long-term occupation of tribal homelands, and observation and interaction with places. American Indians understood and valued the relationship between local environments and cultural traditions, and recognized that human beings are part of the environment.

- Long before their contact with Europeans, indigenous people populated the Americas and were successful

stewards and managers of the land, from the Arctic Circle to Tierra del Fuego. European contact resulted in

exposure to Old World diseases, displacement, and wars, devastating the underlying foundations of American

Indian societies.

- Throughout their histories, Native groups have relocated and successfully adapted to new places and environments.

- Well-developed systems of trails, including some hard-surfaced roads, interlaced the Western Hemisphere prior to European contact. These trading routes made possible the exchange of foods and other goods. Many of the trails were later used by Euro-Americans as roads and highways.

- The imposition of international, state, reservation, and other borders on Native lands changed relationships between people and their environments, affected how people lived, and sometimes isolated tribal citizens and family members from one another.

4. Individual Development and Identity

American Indian individual development and identity is tied to culture and the forces that have influenced and

changed culture over time. Unique social structures, such as clan systems, rites of passage, and protocols for

nurturing and developing individual roles in tribal society, characterize each American Indian culture. American

Indian cultures have always been dynamic and adaptive in response to interactions with others.

Unique social structures, such as clan systems, rites of passage, and protocols for

nurturing and developing individual roles in tribal society, characterize each American Indian culture. American

Indian cultures have always been dynamic and adaptive in response to interactions with others.

Key Concepts:

- For American Indians, identity development takes place in a cultural context, and the process differs from one American Indian culture to another. American Indian identity is shaped by the family, peers, social norms, and institutions inside and outside a community or culture.

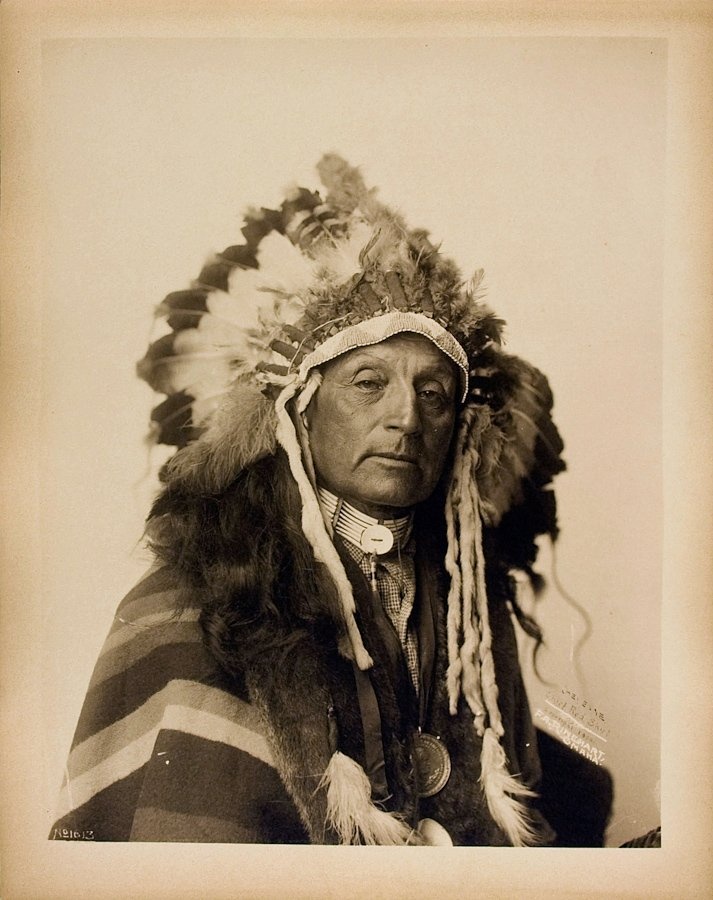

- Historically, well-established conventions and practices nurtured and promoted the development of

individual identity. These included careful observation and nurturing of individual talents and interests by

elders and family members; rites of passage; social and gender roles; and family specializations, such as

healers, religious leaders, artists, and whalers.

- Contact with Europeans and Americans disrupted and transformed traditional norms for identity development.

- Today, Native identity is shaped by many complex social, political, historical, and cultural factors.

- In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, many American Indian communities have sought to revitalize and reclaim their languages and cultures.

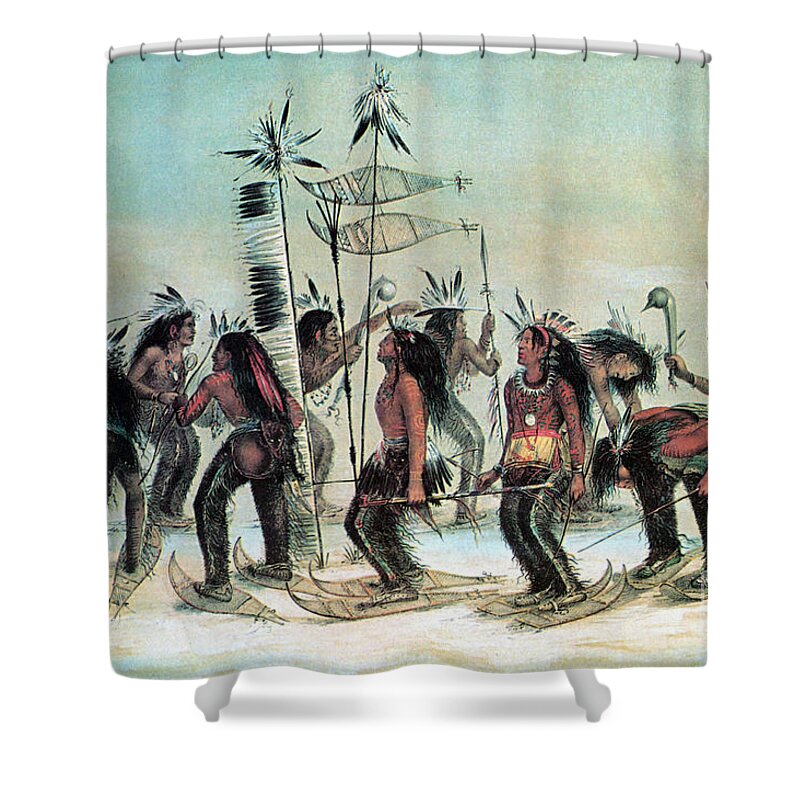

5. Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

American Indians have always operated and interacted within self-defined social structures that include institutions, societies, and organizations, each with specific functions. These social structures have shaped the lives and histories of American Indians through the present day.

Key Concepts:

- There is no single American Indian culture or language.

- American Indian institutions, societies, and organizations defined people's relationships and roles, and

managed responsibilities in every aspect of life—religion, health, government, diplomacy, war, agriculture,

hunting and fishing, trade, and so on.

- Native kinship systems were influential in shaping people's roles and interactions among other individuals, groups, and institutions.

- External educational, governmental, and religious institutions have exerted major influences on American Indian individuals, groups, and institutions. Native people have fought to counter these pressures and have adapted to them when necessary. Many Native institutions today are mixtures of Native and Western constructs, reflecting external influence and Native adaptation.

- A variety of specialized agencies have been formed to interact with and serve American Indian individuals, groups, and institutions.

- Today, because of treaties, court decisions, and statutes, tribal governments maintain a unique relationship with federal and state governments.

- Today, American Indian governments uphold tribal sovereignty and promote tribal culture and well-being.

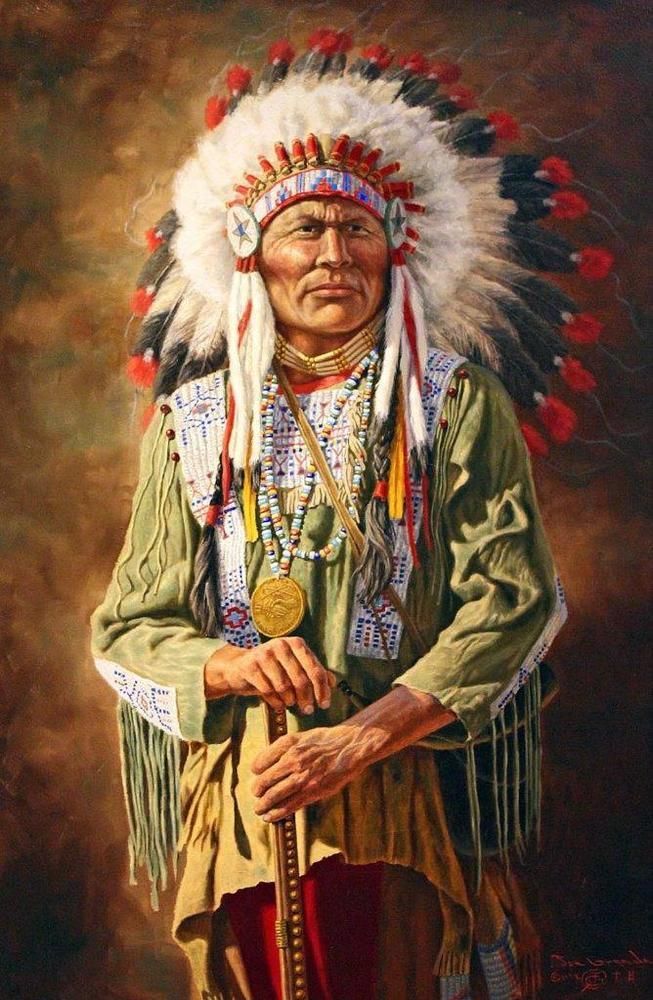

6. Power, Authority, and Governance

American Indians devised and have always lived under a variety of complex systems of government. Tribal governments faced rapid and devastating change as a result of European colonization and the development of the United States. Tribes today still govern their own affairs and maintain a government-to-government relationship with the United States and other governments.

Key Concepts:

- Today, tribal governments operate under self-chosen traditional or constitution-based governmental

structures. Based on treaties, laws, and court decisions, they operate as sovereign nations within the

United States, enacting and enforcing laws and managing judicial systems, social well-being, natural

resources, and economic, educational, and other programs for their members. Tribal governments are also

responsible for interactions with American federal, state, and municipal governments.

- Long before European colonization, American Indians had developed a variety of complex systems of government that embodied important principles for effective rule. American Indian governments and leaders interacted, recognized each other's sovereignty, practiced diplomacy, built strategic alliances, waged wars, and negotiated peace accords.

- After 1492, American Indians suffered diseases and genocidal events that resulted in death on a catastrophic scale and the rapid decimation of Native populations. These episodes greatly compromised the continuity of existing tribal government structures.

- A variety of political, economic, legal, military, and social policies were used by Europeans and

Americans to remove and relocate American Indians and to destroy their cultures. U.S. policies regarding

American Indians were the result of major national debate.

Many of these policies had a devastating effect

on established American Indian governing principles and systems. Other policies sought to strengthen and

restore tribal self-government.

Many of these policies had a devastating effect

on established American Indian governing principles and systems. Other policies sought to strengthen and

restore tribal self-government. - A variety of historical policy periods have had a major impact on American Indian people's abilities to

self-govern. These include:

- Colonization Period, since 1492

- Treaty Period, 1789–1871

- Removal Period, 1834–1871

- Allotment/Assimilation Period, 1887–1934

- Tribal Reorganization, 1934–1958

- Termination, 1953–1988

- Self-Determination, 1975–present

7. Production, Distribution and Consumption

American Indians developed a variety of economic systems that reflected their cultures and managed their

relationships with others. Prior to European arrival in the Americas, American Indians produced and traded goods

and technologies using well-developed systems of trails and widespread transcontinental, intertribal trade

routes. Today, American Indian tribes and individuals are active in economic enterprises that involve production

and distribution.

Prior to European arrival in the Americas, American Indians produced and traded goods

and technologies using well-developed systems of trails and widespread transcontinental, intertribal trade

routes. Today, American Indian tribes and individuals are active in economic enterprises that involve production

and distribution.

Key Concepts:

- For thousands of years American Indians developed and operated vast trade networks throughout the Western Hemisphere.

- American Indians traded, exchanged, gifted, and negotiated the purchase of goods, foods, technologies, domestic animals, ideas, and cultural practices with one another.

- American Indians played influential and powerful roles in trade and exchange economies with partners in

Europe during the colonial period. These activities also supported the development and growth of the United

States.

- Today, American Indians are involved in a variety of economic enterprises, set economic policies for their nations, and own and manage natural resources that affect the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services throughout much of the United States.

8. Science, Technology, and Society

American Indian knowledge resides in languages, cultural practices, and teaching that spans many generations. This knowledge is based on long-term observation, experimentation, and experience with the living earth. Indigenous knowledge has sustained American Indian cultures for thousands of years. When applied to contemporary global challenges, Native knowledge contributes to dynamic and innovative solutions.

Key Concepts:

- American Indian knowledge can inform the ongoing search for new solutions to contemporary issues.

- American Indian knowledge reflects a relationship developed over millennia with the living earth based on keen observation, experimentation, and practice.

- American Indian knowledge is closely tied to languages, cultural values, and practices. It is founded on the recognition of the relationships between humans and the world around them.

- American Indian knowledge allowed American Indians to live productive, innovative, and sustainable lives in the diverse environments of the Western Hemisphere.

- American Indian knowledge and related innovations, goods, and technologies (e.g., agriculture) have had enormous global impact.

- Major social, cultural, and economic changes took place in American Indian cultures as a result of the

acquisition of goods and technologies from Europeans and others.

- Much American Indian knowledge was destroyed in the years after contact with Europeans. Nevertheless, the intergenerational transfer of traditional knowledge, the recovery of cultural practices, and the creation of new knowledge continue in American Indian communities today.

9. Global Connections

Much American Indian knowledge was destroyed in the years after contact with Europeans. Nevertheless, the intergenerational transfer of traditional knowledge, the recovery of cultural practices, and the creation of new knowledge continue in American Indian communities today.

Key Concepts:

- Interactions among American Indian communities across the Americas contributed to the change, growth, and vitality of Native nations.

- Global interactions with Europeans and others had both positive and negative consequences for American

Indians.

- The knowledge and perspectives of American Indians and other indigenous people around the world have the potential to inform solutions as global interdependence intensifies and change accelerates.

- As sovereign independent nations, American Indian tribes and their citizens are participants in global politics, economies, and other facets of contemporary life.

10. Civic Ideals and Practices

Ideals, principles, and practices of citizenship have always been part of American Indian societies. The rights and responsibilities of American Indian individuals have been defined by the values, morals, and beliefs common to their cultures. American Indians today may be citizens of their tribal nations, the states they live in, and the United States.

Key Concepts:

- As citizens of their tribal nations, American Indians have always had certain rights, privileges, and

responsibilities that are tied to cultural values and beliefs and thus vary from culture to culture.

- Not all American Indians today are citizens of their tribes.

- American Indians have acquired U.S. citizenship through a variety of means, including certain treaties and military service. Citizenship for all American Indians did not occur until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.

- Some American Indian people have neither desired nor accepted U.S. citizenship.

- American Indians today may be citizens of their tribes, the United States, and the states in which they live.

- As U.S. citizens, American Indians have often been denied the same rights and privileges as other U.S. citizens. They have formed movements to gain equitable rights and privileges.

- More than 560 tribal governments are recognized by the United States as having rights of sovereign

self-government.

Dozens of other tribes are recognized by various state governments, whose authorities and

responsibilities differ according to the laws of the states.

Dozens of other tribes are recognized by various state governments, whose authorities and

responsibilities differ according to the laws of the states.

Where To Learn About Native American Culture in the United States

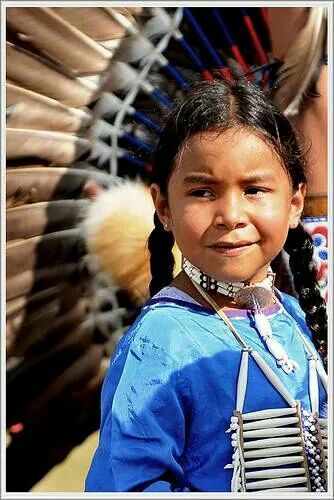

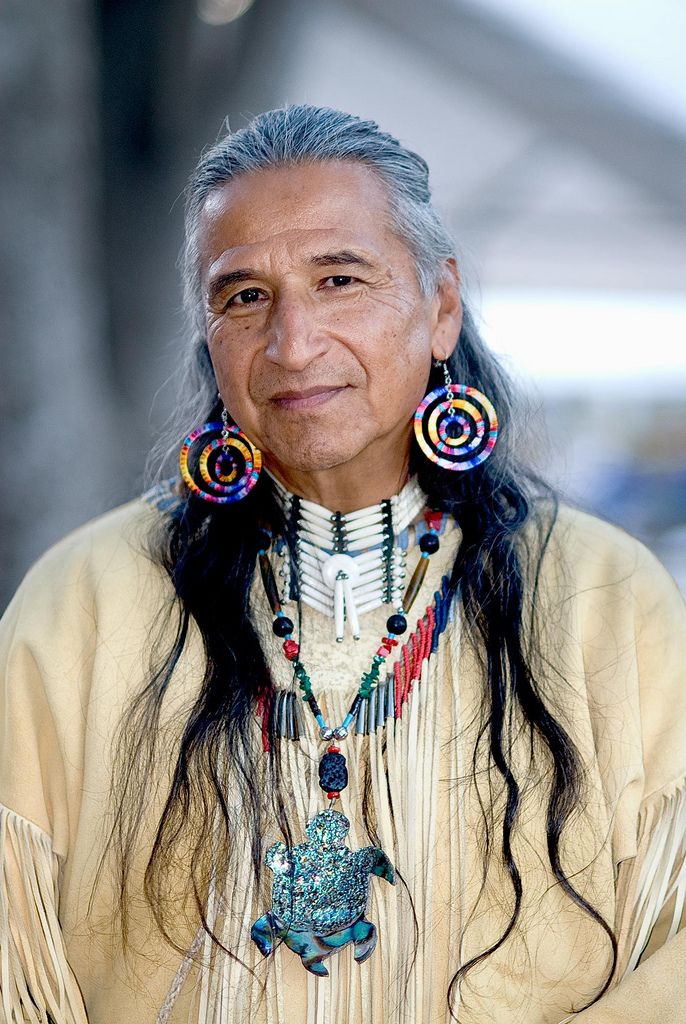

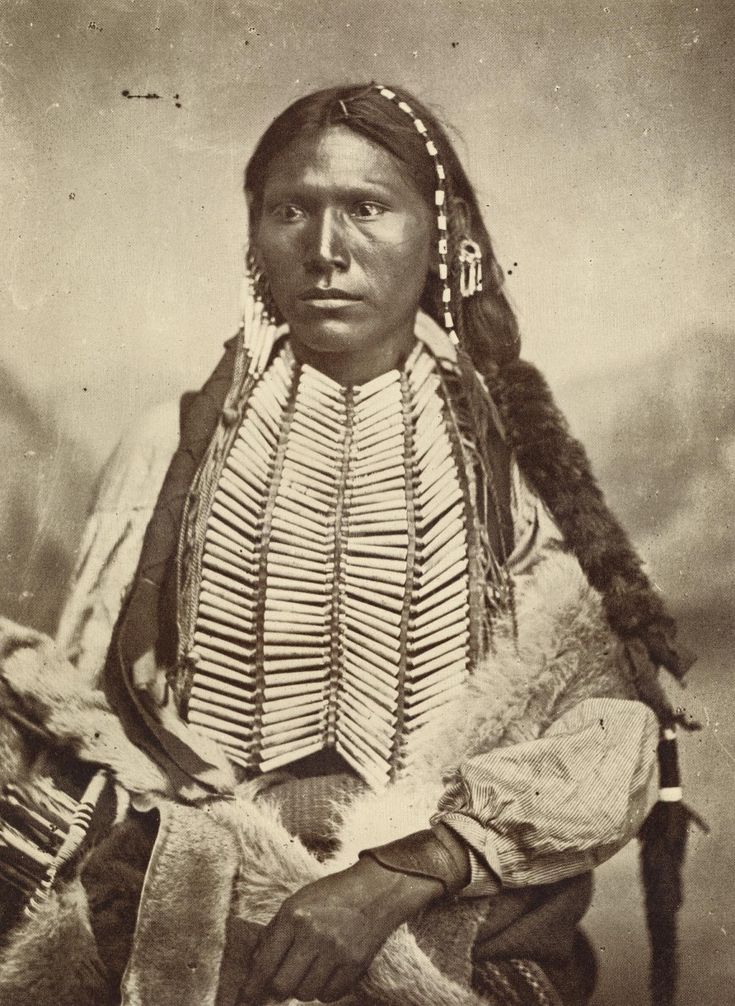

One of my earliest memories is watching Grandma sew beads on Uncle Elmer’s deerskin leggings. Listen to my grandmother, and you’ll hear stories about me in diapers moving to the heartbeat of the drum. Talk to me and I’ll tell you about my husband recalling how unfamiliar he felt when he first met me and found himself the only non-Indian person among American Indians.

Fusing an understanding of Native American people won’t happen with a few social outings, but it’s a good start in a series of small steps. The difference between appreciating or exploiting a culture — and avoiding cultural appropriation — has to do with how we watch and listen. Observe quietly and be respectful. Be a well-behaved guest and use your best company manners. Let the changes take place inside of you slowly.

Let the changes take place inside of you slowly.

Here are 10 places to discover modern-day Indian life and observe tribal descendants echoing and giving expression to cultural traditions.

Photo: Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian/Facebook

The National Museum of the American Indian is the first national museum in the United States dedicated solely to Native American heritage. It highlights over 12,000 years of history across more than 1,200 indigenous tribes and cultures, and features one of the world’s most expansive collections of American Indian arts, artifacts, and photographic and media archives. Permanent exhibitions delve into native religions and ceremonies, as well as native communities’ contemporary struggles for identity.

Where: The National Museum of the American Indian is located on the National Mall between the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum and the US Capitol Building.

Hours of operation: 10 AM – 5:30 PM, closed December 25.

Price: Admission is free.

The museum’s Mitsitam Native Foods Cafe provides visitors with the opportunity to enjoy the indigenous cuisines of the Americas and to explore the history of Native foods.

Hours of operation: The Mitsitam Cafe is open daily 11 AM – 3 PM, closed December 25.

Photo: Nick Fox/Shutterstock

Taos Pueblo is home to the Tiwa-speaking tribe and is set against a backdrop of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Today, nearly 150 people call Taos Pueblo home, and visitors can take guided tours and learn about the village’s culture, history, people, and ancient pueblo life. Taos Pueblo has been inhabited by members of the Taos tribe for more than 1,000 years.

Where: 120 Veterans Highway, Taos, NM

Admission Price: Adults $16 per person. Children 10 and under are free.

Hours: The Pueblo is generally open to visitors daily from 8 AM to 4:30 PM (Sunday 8:30 AM to 4:30 PM), except when tribal rituals require closing the Pueblo.

Photo: PhotoTrippingAmerica/Shutterstock

Located in the foothills of Oklahoma’s Ozark Mountains, the Cherokee Heritage Center is dedicated to preserving the culture and artifacts of the Cherokee Nation. Take a walking tour through Diligwa, a living history exhibit that depicts a 1710 Cherokee village and allows visitors to experience craft-making demonstrations, storytelling, and recreated daily life in the early 18th century. Visit the center’s representation of a late 19th-century rural Cherokee village, Adams Corner. Experience the Trail of Tears exhibit, which delves into the forced removal of Cherokees from their ancestral lands in the 1830s to what is now present-day Oklahoma.

Where: 21192 S. Keeler Drive, Park Hill, OK 74451

Hours of operation: Visit the Cherokee Heritage Museum website for specific summer, winter, and holiday hours.

Price: Adults: $12, youth (5-18 years of age) $7.00. Children under five years of age with paid a adult are free.

For over 35 years, Red Earth has been recognized as the primary multi-cultural resource in Oklahoma for advancing the understanding and continuation of traditional and contemporary Native culture and art.

When does it take place: This is an annual event. Visit the Red Earth website for specific dates, more information and to obtain a visitor’s guide.

Photo: EQRoy/Shutterstock

Arizona is home to 22 tribes, each with its own rich history, culture, language and land base. The Heard Museum works with American Indian tribes to reposition the Heard away from the traditional museum role as a professional observer of “the other”, and is dedicated to preserving the cultures and heritage of Native American Tribes in the Southwestern United States.

Where: 2301 N. Central Avenue, Phoenix, AZ 85004

Hours of operation: Tuesday to Sunday: 8 AM to 4 PM

Price: Adults (ages 18-64) $18.00, Children (ages 6-17) $9. Advanced bookings online is cheaper than walk-ins.

Advanced bookings online is cheaper than walk-ins.

Seeing American Indian life through the lens of Native filmmakers is one of the best ways to understand the modern Native experience. Visit the American Indian Film Festival website for more information.

The Navajo Nation is the largest Indian reservation in the United States, spanning 27,000 square miles throughout Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, with over 173,000 residents (as of the 2010 census). The annual Navajo Nation Fair takes place annually in September. Guests can observe powwows, tribal dances, and select ceremonies held for healing and religious, not entertainment, purposes. Guests will be asked to refrain from taking photographs or to quietly leave during certain parts of a ceremony. This weeklong celebration is an opportunity to learn about the Navajo people and culture.

Photo: Teresa Otto/Shutterstock

Every third week of August, Crow Agency (60 miles south of Billings off I-90) becomes the Tepee Capital of the World when it hosts Crow Fair, the largest modern-day American Indian encampment in the nation, and the largest gathering of the year for the Apsaalooke Nation.

Photo: aceshot1/Shutterstock

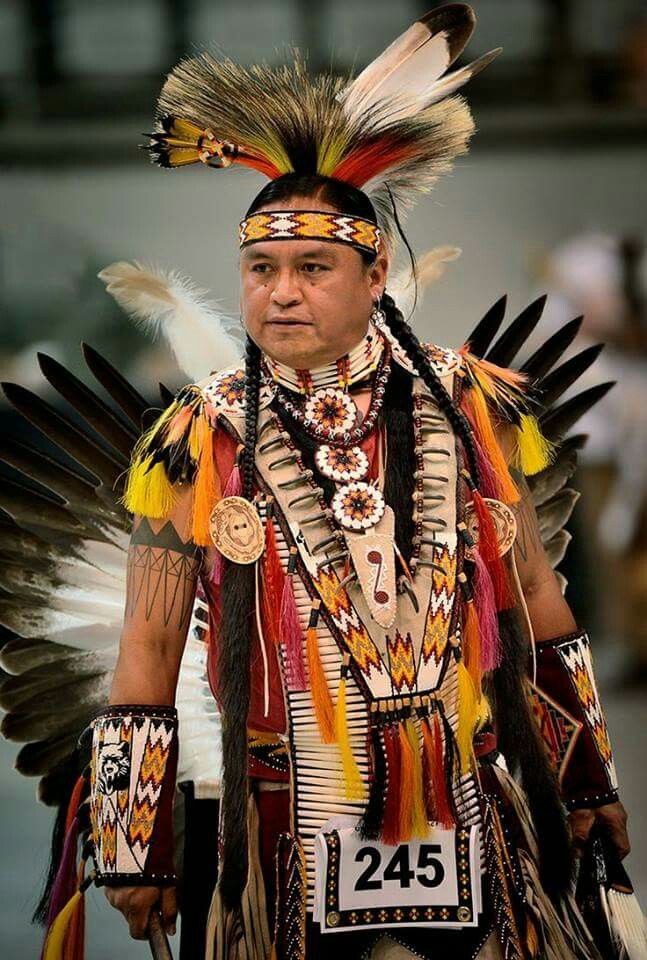

The Gathering of Nations is the largest powwow in North America and attracts thousands of indigenous people representing hundreds of tribes. The multi-day event’s festivities celebrate and promote Native American cultural heritage. Highlights include traditional song, dance, and drumming competitions, which feature over 3,000 performers representing more than 500 North American tribes. Attendees can also buy Native art from more than 800 Native American artisans and traditional Native foods.

10. Attend a Powwow in your local area

Photo: Jose Gil/Shutterstock

While it’s great fun and highly informative to attend the Gathering of Nations powwow or Crow Fair, not everyone has access to travel. Any powwow held in your community that you feel drawn to is the right place to begin. Surround yourself with Native families as they exchange news, ideas, song and dance, and reflect on traditions.

If money or opportunity does not permit you to travel to destinations offering exposure to observe and experience Native American ethnicity and culture, then travel from your armchair. Here are Native published websites that offer information and articles presented from a Native American point of view.

Here are Native published websites that offer information and articles presented from a Native American point of view.

-

Indian Country Media Network

-

Project 562: Changing The Way We See Native America

-

News From Native California

-

American Indians In Children’s Literature

-

Oyate

Indian Country Today is dedicated to serving the Nations and celebrating Native American people and offers a wide variety of news and resources.

Project 562 is offered as a solution to historical inaccuracies, stereotypical representations and silenced Native American Voices in media in an effort to humanize the otherwise “vanishing race” and share the stories that Native Americans would like to be told.

The experience of California Indians has been diverse and profound

Established in 2006, American Indians in Children’s Literature (AICL) provides critical perspectives and analysis of indigenous peoples in children’s and young adult books, the school curriculum, popular culture, and society. Scroll down for links to book reviews, Native media, and more.

Scroll down for links to book reviews, Native media, and more.

Oyate is a Native organization working to see that Native lives and histories are portrayed with honesty and integrity.

A version of this article was previously published on October 10, 2017, and was updated on September 11, 2020, with more information.

More like this

Value Positions of Education in the Development of American Indian Cultures

UDK 008(73):37 Danchevskaya O.Ye.

VALUE POSITIONS OF EDUCATION IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF INDIAN CULTURES IN THE USA.

Danchevskaya Oksana Evgenievna, Senior Lecturer, Department of English Phonetics, Faculty of Foreign Languages, Moscow State Pedagogical University; Competitor of the Department of Cultural Studies, Faculty of Sociology, Economics and Law, Moscow Pedagogical State University

Annotation

The article analyzes the changes that took place in the system of Indian education from the beginning of the development of North America by Europeans to the present stage. Particular attention is paid to the impact of such changes on the culture, ethnic identity, linguistic heritage, and traditions of the American Indians. The steps taken in the field of Indian education in the 21st century by both the US government and the autochthonous population are covered in sufficient detail.

Particular attention is paid to the impact of such changes on the culture, ethnic identity, linguistic heritage, and traditions of the American Indians. The steps taken in the field of Indian education in the 21st century by both the US government and the autochthonous population are covered in sufficient detail.

Key words: American Indians (Native Americans), Indian cultures, Indian languages, Indian education system.

It is impossible to imagine any society in which education in one form or another would not be given special attention as a process of development and self-development of the individual, associated with the acquisition of socially significant experience of mankind, embodied in knowledge, skills, creative activity and emotional and value attitude to peace, a necessary condition for the preservation and development of material and spiritual culture.[1] The autochthonous population of North America can serve as a vivid example of how closely education is interrelated with the culture and daily life of an ethnic group.

The upbringing and education of children and youth has always played an important role in the life of American Indians. Parents, relatives and all members of the tribe were constantly engaged in teaching the younger generation, who were carefully passed on the knowledge, skills and abilities accumulated by the ancestors for centuries, which are necessary not only for each individual, but also for the survival and further development of the community as a whole. This knowledge was multifaceted and concerned all aspects of human existence on earth. Children were taught their native language, learned the lessons of labor education, acquired skills in building houses,

comprehended the secrets of traditional crafts, martial arts, healing, joined the hunt, competed in dexterity and endurance, participated in the ceremonies and rituals of their tribe, receiving spiritual instructions from their elders, learning to live in harmony with people and the nature around them. Before the arrival of Europeans on the continent, the Indians had not heard of any special schools. Their school was life itself, with its simple way of life and centuries-old traditions, from which, in fact, the culture of a particular tribe was formed.

Their school was life itself, with its simple way of life and centuries-old traditions, from which, in fact, the culture of a particular tribe was formed.

“The main socio-cultural functions of education are associated with the solution of the problem of socialization and inculturation of the individual”[2], and the processes of inculturation, the assimilation by the individual of “norms and values that regulate the collective life of community members and maintain the necessary level of social consolidation of people, lead to direct social reproduction of the community as a cultural systemic integrity.”[3] Therefore, even at the dawn of the era of European exploration of North America on the continent, with the advent of missionaries who were sent to Indian communities with a “civilizing” role, the foundation for future schools began to be laid, which in turn were to become a powerful tool for the assimilation of natives into Euro-American society. The missionaries primarily introduced the Native Americans to the teachings of the Christian faith as well as the realities of European life, and sometimes taught them how to write and read English. Some of them went further and developed a writing system for individual Indian languages (for some of the aboriginal languages, writing was later introduced by anthropologists). Some missionaries, in particular the Jesuits, in some areas of North America continue their educational activities today. This, of course, traces the positive role of the interaction of Americans with Indian cultures. But in general, such education was completely divorced from the vital needs of the indigenous population itself.

Some of them went further and developed a writing system for individual Indian languages (for some of the aboriginal languages, writing was later introduced by anthropologists). Some missionaries, in particular the Jesuits, in some areas of North America continue their educational activities today. This, of course, traces the positive role of the interaction of Americans with Indian cultures. But in general, such education was completely divorced from the vital needs of the indigenous population itself.

An example of this is the treaty signed at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1744 between the government of Virginia and the Six Nations. ... the envoys of Virginia addressed the Indians with a speech and said that there were funds at Williamsburg College for the education of Indian youth, and that if the leaders of the Six Nations sent half a dozen of their sons to this college, the government would see that they were well provided for and trained in all the sciences of the white people. The [Indian] speaker began by expressing a deep sense of gratitude to the government of Virginia for this offer. “Because we know,” he said, “that you highly value the sciences taught in the college, and that the maintenance of our young people will be very dear to you, therefore we are convinced that by this offer you want to do us a good deed; and we thank you very much. But you are wise and should know that different nations think differently, and therefore you should not be offended if our ideas about this kind of training do not coincide with yours. We have some experience in this, several of our young men have recently been educated in the colleges of the northern provinces, they have been trained in all your sciences; but when they returned to us, it turned out that they were poor runners, did not know how to live in the forests, were unable to endure cold and hunger, did not know how to build huts, hunt deer, kill enemies, speak our language well, and therefore they incapable of being either hunters or warriors or members of the council; they are good for nothing at all.

The [Indian] speaker began by expressing a deep sense of gratitude to the government of Virginia for this offer. “Because we know,” he said, “that you highly value the sciences taught in the college, and that the maintenance of our young people will be very dear to you, therefore we are convinced that by this offer you want to do us a good deed; and we thank you very much. But you are wise and should know that different nations think differently, and therefore you should not be offended if our ideas about this kind of training do not coincide with yours. We have some experience in this, several of our young men have recently been educated in the colleges of the northern provinces, they have been trained in all your sciences; but when they returned to us, it turned out that they were poor runners, did not know how to live in the forests, were unable to endure cold and hunger, did not know how to build huts, hunt deer, kill enemies, speak our language well, and therefore they incapable of being either hunters or warriors or members of the council; they are good for nothing at all. .we, if the people of Virginia send us a dozen of their sons, take care of their education as best we can, teach them everything we know, and make them real men.[4]

.we, if the people of Virginia send us a dozen of their sons, take care of their education as best we can, teach them everything we know, and make them real men.[4]

However, the American government began to allocate special funds for the education of the Indians (and often it meant “education”) only from the beginning of the 19th century, but the money continued to go mainly to missions. The education of the indigenous population was part of the ethno-cultural policy of the state and was supposed to serve both the religious and political and economic goals of the Americans, in particular, their land reform, because, according to them, “a wild Indian needs a thousand acres of land for free movement, while an educated person will need only a small plot to decently support a family. Barbarism is costly, wasteful, and immoderate. Intelligence stimulates frugality and increases prosperity.”[5]

First, day schools began to appear on the reservations, run by missionaries. Attendance at these missionary schools was compulsory for all children between the ages of 6 and 16. They were forbidden to adhere to the traditions of their tribe and to speak any other language than English. However, from the point of view of assimilation, such a training scheme was not successful, since the children were close to home, where they continued to communicate in their native language and adhere to their culture.

They were forbidden to adhere to the traditions of their tribe and to speak any other language than English. However, from the point of view of assimilation, such a training scheme was not successful, since the children were close to home, where they continued to communicate in their native language and adhere to their culture.

Then, on the basis of reservations, it was decided to establish boarding schools in which children would live permanently and could go home only for Christmas and summer holidays. But even this did not help to familiarize the children with American values and culture, as their parents often visited them, thereby not allowing them to break away from the life of the tribe.

The US government had to resort to a third option - to move boarding schools off the reservations. This idea was born when Captain Richard Henry Pratt organized a small school for 72 Apache prisoners at Fort Marion in 1875, where he taught them English and preached Christianity. Subsequently, he decided to continue his experience and on November 1, 1878 he opened the Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which eventually became one of the main Indian boarding schools. R. Pratt's goal was "to kill an Indian and [thereby] save [in him] a man"[6], in other words, to completely assimilate the aboriginal population into American society, immersing it in the English-speaking environment and culture. At the Carlisle School, part of the educational program was the mandatory residence of Indian children for several months in American families, where they had to experience all the benefits of living in a civilized European style according to Christian canons. Such schools were also beneficial for Americans, as they opened up new jobs for them, and could also provide cheap labor in the form of students.

Subsequently, he decided to continue his experience and on November 1, 1878 he opened the Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which eventually became one of the main Indian boarding schools. R. Pratt's goal was "to kill an Indian and [thereby] save [in him] a man"[6], in other words, to completely assimilate the aboriginal population into American society, immersing it in the English-speaking environment and culture. At the Carlisle School, part of the educational program was the mandatory residence of Indian children for several months in American families, where they had to experience all the benefits of living in a civilized European style according to Christian canons. Such schools were also beneficial for Americans, as they opened up new jobs for them, and could also provide cheap labor in the form of students.

The rules at boarding schools were very strict. Students had their hair cut short, dressed from their traditional clothes into school uniforms, and even had their Native American names replaced with English ones. In schools, any manifestations of the cultures and religions of students were prohibited. Living conditions left much to be desired, and in combination with hard work, which was an indispensable condition for staying at school, they left a serious imprint on their health. In addition, Native Americans found themselves separated from their families for a long time, which also had a negative effect on the children's psyche. Many parents did not want to send their children to boarding schools, and then the authorities took them by force. Some children were so impressed that they fell ill or ran away.

In schools, any manifestations of the cultures and religions of students were prohibited. Living conditions left much to be desired, and in combination with hard work, which was an indispensable condition for staying at school, they left a serious imprint on their health. In addition, Native Americans found themselves separated from their families for a long time, which also had a negative effect on the children's psyche. Many parents did not want to send their children to boarding schools, and then the authorities took them by force. Some children were so impressed that they fell ill or ran away.

The elders of the tribe, who witnessed the catastrophic changes of the nineteenth century - bloody wars, the almost complete disappearance of bison, disease and famine, the reduction of tribal territory, the humiliation of life on reservations, the invasion of

missionaries and white settlers - it seemed that there would be no end to the atrocities, created by whites. And after all that, schools. After all this, the white man concluded that the only way to save the Indians was to destroy them, that the last great Indian war must be fought against children. Now they've come for the children.[7]

After all this, the white man concluded that the only way to save the Indians was to destroy them, that the last great Indian war must be fought against children. Now they've come for the children.[7]

Under the plan of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the successful assimilation of Aboriginal schoolchildren was intended to remove the "Indian problem" from the agenda, since "there would be no more people called Indians."[8] After leaving school, graduates had to "bring civilization" (including the English language) to their tribe, that is, to assimilate themselves and help their community in this. However, this happened extremely rarely. Even those students who outwardly submitted often secretly communicated with each other in their native language and maintained their culture. Almost none of the graduates became what the educators expected to see: people either returned to their roots completely, or combined both cultures. Despite the fact that at the beginning of the 20th century, new pedagogical theories called for softer measures of education, for the gradual transformation of Indian children, taking into account national characteristics, boarding schools did not bring the desired results. Meriam's report at 19In 28, he criticized the US educational policy towards the indigenous population, and the system of boarding schools officially ceased to exist, leaving an indelible mark on the memory of the Indians and inflicting mental trauma on entire generations: a significant part of the graduates, finding themselves "between two worlds" - Indian and Euro-American - so and could not find her place in life. "Children returned from school disappointed losers, unable to re-adjust to life on the reservation and also unable to settle in white society."[9]] Ultimately, they turned out to be strangers among their own and did not become their own among strangers. For many, this was a real tragedy.

Meriam's report at 19In 28, he criticized the US educational policy towards the indigenous population, and the system of boarding schools officially ceased to exist, leaving an indelible mark on the memory of the Indians and inflicting mental trauma on entire generations: a significant part of the graduates, finding themselves "between two worlds" - Indian and Euro-American - so and could not find her place in life. "Children returned from school disappointed losers, unable to re-adjust to life on the reservation and also unable to settle in white society."[9]] Ultimately, they turned out to be strangers among their own and did not become their own among strangers. For many, this was a real tragedy.

Today, the situation in the field of education is more optimistic. Thus, educational institutions on the reservations are already controlled by the tribes themselves and supported in every possible way by the state: grants are issued to existing colleges, assistance is provided in founding new ones. Today, Native Americans are trying to take an active role in their own education. Back at 19In 1972, the presidents of the first six tribal colleges in the country established the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (A1HEC) to provide comprehensive support to Indian educational institutions. Today, it already operates 34 colleges in the US and one in Canada. The consortium has four main goals: “to maintain generally accepted standards of excellence in American Indian education; to promote the development of new colleges controlled by the tribes; promote the development of a legislative framework to support American Indian higher education; to stimulate the active involvement of American Indians in the development of higher education policy.”[10] Most reservations have their own colleges, where young people are introduced to the culture and traditions of the tribe and taught their native language. Today, about 20 Indian languages are represented in their programs. The general school curriculum of such colleges also included subjects related to the history, languages, cultures, traditions, and art of the Indians, which played an important role in their cultural revival.

Today, Native Americans are trying to take an active role in their own education. Back at 19In 1972, the presidents of the first six tribal colleges in the country established the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (A1HEC) to provide comprehensive support to Indian educational institutions. Today, it already operates 34 colleges in the US and one in Canada. The consortium has four main goals: “to maintain generally accepted standards of excellence in American Indian education; to promote the development of new colleges controlled by the tribes; promote the development of a legislative framework to support American Indian higher education; to stimulate the active involvement of American Indians in the development of higher education policy.”[10] Most reservations have their own colleges, where young people are introduced to the culture and traditions of the tribe and taught their native language. Today, about 20 Indian languages are represented in their programs. The general school curriculum of such colleges also included subjects related to the history, languages, cultures, traditions, and art of the Indians, which played an important role in their cultural revival. Today, there are federal programs under the Bureau of Indian Affairs aimed at raising the educational level of the aboriginal population and using an individual approach in teaching - depending on the tribal affiliation, abilities and development of each individual. The Congress aims to provide the Indians with a full-fledged education that would allow them to further master their chosen specialties and

Today, there are federal programs under the Bureau of Indian Affairs aimed at raising the educational level of the aboriginal population and using an individual approach in teaching - depending on the tribal affiliation, abilities and development of each individual. The Congress aims to provide the Indians with a full-fledged education that would allow them to further master their chosen specialties and

continue professional growth. The entire system of education of the indigenous population is under the special jurisdiction of the state, which is associated not only with the doctrine of guardianship, but also with the awareness of the American government of the importance of such programs. According to the Census Bureau for 2000, 70.9% of the indigenous population has a school education, and 15.4% have bachelor's degrees and above. But there is still a lot to be done, because 16.1% of children still do not graduate from school...[11] However, the Indians themselves are also active in resolving this problem. For example, in order to provide necessary resources to tribal colleges and to assist Native American students in education from high school to graduate school, and to recognize the achievements of Native Americans in various fields of science in 19TES), and in 1997, a new school began operating on a part of the Navajo Reservation in Utah. This happened only after the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against the Department of School Education of this state. The reason was the lack of a secondary school in that area, as a result of which the children had to travel very far to study. The lawsuit was granted, which once again reminded everyone of the equal rights of the Indians, including the right to free secondary education.[12]

For example, in order to provide necessary resources to tribal colleges and to assist Native American students in education from high school to graduate school, and to recognize the achievements of Native Americans in various fields of science in 19TES), and in 1997, a new school began operating on a part of the Navajo Reservation in Utah. This happened only after the Department of Justice filed a lawsuit against the Department of School Education of this state. The reason was the lack of a secondary school in that area, as a result of which the children had to travel very far to study. The lawsuit was granted, which once again reminded everyone of the equal rights of the Indians, including the right to free secondary education.[12]

Nevertheless, unfortunately, the policy of suppressing ethnic cultures pursued by the state until the middle of the 20th century played a detrimental role. Many parents understood that if they wanted their children to succeed in American society, they had to learn English. As a result, today only 9% of all living North American Indians speak their native language.[13]

As a result, today only 9% of all living North American Indians speak their native language.[13]

Indian languages deserve special attention, because language is the most important means of preserving and maintaining culture. It is through him that the spirituality of the people, their worldview, value orientations, the deep essence of religious ideas, ceremonies, rituals, rituals are revealed. According to experts, at the time of the arrival of the first Europeans on both American continents, there were from 15 to 40 million people speaking 1800 - 2000 languages, 300 of which were in North America. This diversity of languages in the Western Hemisphere alone is unique,[14] and some of them are surprising in their structure. So, linguists classify the language of the Chippewa Indians, in which there are about 6,000 verb forms, among the most difficult in the world. K 19In 95, about 209 Indian languages \u200b\u200bsurvived in North America, some of which may belong to the same language group. But there are tribes in which the last native speakers are only a handful of elderly people, with the departure of which their language will also die, and, consequently, almost 80% of the total number of modern languages \u200b\u200bof the North American Indians will sink into oblivion. The situation is complicated by the fact that these languages did not have a written language. For example, the Cherokee script, developed and introduced by Sequoyah, a member of their tribe, did not appear until 1821 and was the first non-European script to become widespread among Indians and mestizos. In the United States, the most common Indian language today is Navajo, which is spoken by approximately 150,000 people.[16] 91), which aims to "protect the rights of indigenous languages and promote linguistic and cultural diversity".[17] In the U.S. Department of Education's

But there are tribes in which the last native speakers are only a handful of elderly people, with the departure of which their language will also die, and, consequently, almost 80% of the total number of modern languages \u200b\u200bof the North American Indians will sink into oblivion. The situation is complicated by the fact that these languages did not have a written language. For example, the Cherokee script, developed and introduced by Sequoyah, a member of their tribe, did not appear until 1821 and was the first non-European script to become widespread among Indians and mestizos. In the United States, the most common Indian language today is Navajo, which is spoken by approximately 150,000 people.[16] 91), which aims to "protect the rights of indigenous languages and promote linguistic and cultural diversity".[17] In the U.S. Department of Education's

ranking of minority teacher training programs, this institution was ranked in the top ten in the nation.[18]

Modern American legislation, in contrast to the beginning of the last century - the period of boarding schools - actively supports the preservation of the linguistic heritage of the Indians. October 30 19In 1990, the Native American Languages Act was passed, in which Congress emphasized that “the status of [their] cultures and languages ... is unique, and the United States is responsible for engaging with Native Americans to ensure the survival of these unique cultures and languages" because "the traditional languages of ... [the Indians] are an integral part of their cultures and identities, and the main form of transmission, and hence survival. [their] cultures, literatures, histories, religions, political institutions and values.”[19]] Along with teaching Indians their native language and including the latter in university programs, other steps are being taken. For example, the American Modern Language Association decided in the spring of 2005 to encourage linguists to study Native American languages in depth, followed by the compilation of dictionaries, grammars, and other educational materials to help in their teaching.

October 30 19In 1990, the Native American Languages Act was passed, in which Congress emphasized that “the status of [their] cultures and languages ... is unique, and the United States is responsible for engaging with Native Americans to ensure the survival of these unique cultures and languages" because "the traditional languages of ... [the Indians] are an integral part of their cultures and identities, and the main form of transmission, and hence survival. [their] cultures, literatures, histories, religions, political institutions and values.”[19]] Along with teaching Indians their native language and including the latter in university programs, other steps are being taken. For example, the American Modern Language Association decided in the spring of 2005 to encourage linguists to study Native American languages in depth, followed by the compilation of dictionaries, grammars, and other educational materials to help in their teaching.

Curious is the fact that, despite the long years of the policy of semi-pressure of Indian languages and cultures, the US itself sometimes resorted to their help. For example, some of the languages - Apache, Cherokee, Choctaw and Comanche - were used by the US military to convey secret messages. During World War II, a new encoding language was needed. The way out was found by World War I veteran Philip Johnston, who, although an American, spoke the Navajo language perfectly. He explained his choice by the fact that it is a very complex language that did not have a written language at that time. The High Command approved the choice, and on May 19For 42 years, the first 29 Navajo Indians developed a Navajo code with a special dictionary of military terms that had to be memorized in the learning process. The Japanese, experienced in deciphering, were never able to “crack” this code. Among the 540 Navajo Indians who served in the Navy during World War II, between 375 and 420 were Navajo Code Talkers. On September 17, 1992, at the Pentagon (Washington), veteran Navajo codebreakers were awarded honorary awards (previously it was impossible to do this because of the secrecy of the operation).

For example, some of the languages - Apache, Cherokee, Choctaw and Comanche - were used by the US military to convey secret messages. During World War II, a new encoding language was needed. The way out was found by World War I veteran Philip Johnston, who, although an American, spoke the Navajo language perfectly. He explained his choice by the fact that it is a very complex language that did not have a written language at that time. The High Command approved the choice, and on May 19For 42 years, the first 29 Navajo Indians developed a Navajo code with a special dictionary of military terms that had to be memorized in the learning process. The Japanese, experienced in deciphering, were never able to “crack” this code. Among the 540 Navajo Indians who served in the Navy during World War II, between 375 and 420 were Navajo Code Talkers. On September 17, 1992, at the Pentagon (Washington), veteran Navajo codebreakers were awarded honorary awards (previously it was impossible to do this because of the secrecy of the operation). At the same time, an exhibition dedicated to their work in that most important period for all mankind and the code itself was opened, and a monument was erected to them in Veterans Park, located on the Navajo reservation.

At the same time, an exhibition dedicated to their work in that most important period for all mankind and the code itself was opened, and a monument was erected to them in Veterans Park, located on the Navajo reservation.

For Native Americans, however, things began to change for the better only a little over a quarter of a century ago, and this applies to all parts of their culture. Native American scientist, public figure, historian, writer and lawyer Vine Deloria Jr. I am sure that for the most productive interaction of the Indians with the Euro-American civilization, as well as in order to help the tribes, it is necessary that the Native Americans receive a decent education. While lamenting the decline of US culture, he believes that young Indians, before being exposed to the philosophy of the dominant Euro-American culture, should come into close contact with the traditional teachings of their tribes, which will help them make an informed choice. He points to examples of the brilliant level of education among the "Five Civilized Tribes" (Creek, Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, and Chickasaw) achieved back in the 19th century thanks to the deep motivation of students and strict requirements for the entire system of intra-tribal colleges. Undoubtedly, even today, Native Americans study at schools and universities throughout the country, but not all of them graduate. The writer reproaches the state for worrying whether the Indians entered the educational institution or not, instead of

Undoubtedly, even today, Native Americans study at schools and universities throughout the country, but not all of them graduate. The writer reproaches the state for worrying whether the Indians entered the educational institution or not, instead of

worry about whether they really get the necessary knowledge there and whether they are able to go through the entire training stage. And Indians, in turn, often fail to ask the important questions that should guide their behavior:

Why do we send people to college if we can't encourage them to help strengthen the tribe, the resources of the reservation, and the community? Are we letting our best resources - educated people - just flow away? Are we wasting money and lives under the current system, in which there is no responsibility and sovereignty becomes an empty slogan? Are we strengthening nations or destroying communities?[20]

Along with the development of Indian education, the state realized the need to provide American students with comprehensive knowledge about the natives. In 1972, a law was passed on the study of the country's historical heritage, and already 10 years later, more than 250 special courses on the study of the history and culture of ethnic minorities, including American Indians, operated in the educational institutions of the United States. Separate courses began to be developed on the study of Native Americans, including all aspects of their lives - from oral traditions and ceremonies to modern US Indian politics, from the history of the Indians to their achievements in American society. The purpose of such courses, according to the author of one of them, prof. J. B. Ryan, - not only a closer acquaintance with the natives, but also help in understanding much in ourselves. "Before you can come to peace with Native Americans, you first need to understand them with their individuality, distinct cultures and traditions."[21] The emergence of a new subject in university programs - Indian studies (American Indian Studies) - provoked an interest in studying the life of Indian communities.

In 1972, a law was passed on the study of the country's historical heritage, and already 10 years later, more than 250 special courses on the study of the history and culture of ethnic minorities, including American Indians, operated in the educational institutions of the United States. Separate courses began to be developed on the study of Native Americans, including all aspects of their lives - from oral traditions and ceremonies to modern US Indian politics, from the history of the Indians to their achievements in American society. The purpose of such courses, according to the author of one of them, prof. J. B. Ryan, - not only a closer acquaintance with the natives, but also help in understanding much in ourselves. "Before you can come to peace with Native Americans, you first need to understand them with their individuality, distinct cultures and traditions."[21] The emergence of a new subject in university programs - Indian studies (American Indian Studies) - provoked an interest in studying the life of Indian communities. But, unfortunately, not all Native Americans are happy with this, especially when it comes to information that is not customary to disclose to the uninitiated, because of which scientists sometimes face unwillingness on the part of the natives to cooperate. The Indians themselves explain this behavior by the fact that they have already been “studied to death”, but this, as a rule, does not bring any benefit to them.[22] And yet, it must not be forgotten that0003

But, unfortunately, not all Native Americans are happy with this, especially when it comes to information that is not customary to disclose to the uninitiated, because of which scientists sometimes face unwillingness on the part of the natives to cooperate. The Indians themselves explain this behavior by the fact that they have already been “studied to death”, but this, as a rule, does not bring any benefit to them.[22] And yet, it must not be forgotten that0003

The Indian Studies era seeks to introduce Indians into educational systems as leaders, curriculum developers, professors, researchers, and writers. It was conceived not only to cultivate intellectuals within the tribes, but also as a system for studying indigenous communities from the inside, learning the language, culture, historical and legal relationship with the United States as a nation within a nation. It was conceived for the tribal communities of America, and the main goal was the protection of lands, resources and the sovereign autonomy of the nation's status. [23]

[23]

Thus, we can conclude that in the field of education, attempts at forced assimilation and acculturation did not bring the expected results, causing the Indians more harm than good. And yet, even at that time, Euro-American civilization introduced some positive aspects, such as the development of writing among various tribes, and at the present stage, with the aim of reviving ethnic cultures in the country and awakening interest in them, special programs are being created for aboriginal students and in the general program A new subject, Indian studies, is being actively introduced in US universities. Today, unlike in the recent past, Indians have the right to decide for themselves what is more important for their children, taking into account their ethnic and cultural characteristics, which allows them to develop harmoniously, continue cultural traditions and preserve the language of their ancestors.

Literature

1. Large encyclopedic dictionary. (http://www. voliks.ru/)

voliks.ru/)

2. Culturology: XX century. Encyclopedia. St. Petersburg: Universitetskaya kniga, 1998. (http://www.philo sophy.ru/edu/ref/enc/)

3. Ibid.

4. Franklin, B. Notes on the Savages of North America. (http://www.first-americans. spb. ru/n2/win/ franklin. htm)

5. Adams, D.W. Education for Extinction - American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 18751928. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1995. P.20.

6. Keohane, S. The Reservation Boarding School System in the United States, 1870-1928. (http://www.twofrog.com/rezsch.html)

7. Adams, D.W. Education for Extinction - American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 18751928. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1995. P.337.

8.Prucha, F.P. American Indian Treaties: The History of a political anomaly. Berkeley etc.: University of California Press, 1997. P.24.

9. Barron, M.L. (Ed.) American Minorities. NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957. P.153.

10. Tsekhanskaya, K.V. The Indian problem in the USA (60s - 80s of the XX century). Diss. for the competition uch. step. to. ist. n. M., 1984. P.29.

Tsekhanskaya, K.V. The Indian problem in the USA (60s - 80s of the XX century). Diss. for the competition uch. step. to. ist. n. M., 1984. P.29.

11. US Census Bureau. (http://www.census.gov)

12. American Indians. (http://www.usdoj.gov/kidspage/crt/indian.htm)

13. US Census Bureau. (http://www.census.gov)

14. Encyclopedia of North American

(http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/naind/html/na 000107 entries.htm)

15. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 4. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1988.

16. Encyclopedia of North American

(http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/naind/html/na 000107 entries.htm)

17. American Indian Languages Development Institute website (http: //www.u.arizona.edu/~aildi/)

18. Ibid.

19. Native American Languages Act of 1990. P.L. 101-477; October 30, 1990.

20. Deloria, V., Jr. Excerpted from Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. NY, Macmillan, PP. 127. 1969. (http://nativenewsonline.org/natnews.htm)

NY, Macmillan, PP. 127. 1969. (http://nativenewsonline.org/natnews.htm)

21. Ryan, J. B. Listening to Native Americans // Listening: Journal of Religion and Culture, Vol. 31, No.1 Winter 1996 pp. 24-36. (http://www.op.org/DomCentral/library/native.htm)

22. From the author's personal correspondence with Native Americans.

23. Cook-Lynn, E. Anti-Indianism in Modern America: A Voice from Tatekeya's Earth. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2001. P.152-153.

Indians.

Indians.

(AILDI).

why North American Indians have been disenfranchised for centuries - RT in Russian

On June 2, 1924, a law came into force in the United States that granted Indians the right to American citizenship. From the formation of the United States until the beginning of the 20th century, indigenous peoples were exterminated en masse, millions of hectares of land were confiscated from them. Despite the fact that in theory the Indians were given equal rights with the heirs of the colonizers, in practice the document remained formal for a long time, experts say. Although a number of Indians became eligible for benefits after the passage of the citizenship law, they were not granted full voting rights in all states until after the end of World War II.

Although a number of Indians became eligible for benefits after the passage of the citizenship law, they were not granted full voting rights in all states until after the end of World War II.

When European colonialists reached the shores of North America at the end of the 16th century, according to various estimates, up to 18 million Indians lived on the territory of the modern United States. In terms of the level of technical and socio-economic development, they were inferior to the population of Central and South America, but some peoples managed to create pre-state political associations and had a high culture.

The British began to oust the Indian tribes from their lands. The “ally” of the colonialists was European diseases, against which the Native Americans had no immunity: the Indians were specially given infected objects, provoking deadly epidemics among them.

In addition, the Europeans relied on a system of fraudulent contracts when seizing land. The colonizers signed documents for the sale of land with unauthorized persons and recorded in the papers streamlined language, such as "days of travel. " The Indians, when concluding agreements, understood by "days of travel" the standard day's passage of a hunter over rough terrain. However, the colonialists hired the best runners and specially prepared tracks for them. This made it possible to fraudulently increase the area of the purchased territory several times.

" The Indians, when concluding agreements, understood by "days of travel" the standard day's passage of a hunter over rough terrain. However, the colonialists hired the best runners and specially prepared tracks for them. This made it possible to fraudulently increase the area of the purchased territory several times.

- British MP James Oglethorpe introduces the Yamacro Indians to the Georgia Colony Trust, by artist William Verelst

- © William Verelst

Historian and writer Alexei Styopkin said in an interview with RT that in the 18th century, Indians living in the American colonies of the British Empire were officially considered subjects of the king. However, they were limited in political rights.

“In particular, they could not hold official positions. To manage them, the authorities appointed special representatives. As for the Indians who lived outside the counties, on the lands that Britain only formally considered its own, for example, in the border areas, they were also nominally referred to as royal subjects, but they did not even know about it, ”said Styopkin.

The issue of the status of Indians living outside the colonies, the British authorities did not regulate.

"Road of Tears"

After the American War of Independence, the new American authorities tried to partially regulate relations with the Indians. Washington secured for itself the exclusive right to enter into agreements with the indigenous population of America, including the acquisition of land.

Candidate of Cultural Studies, Associate Professor at the Institute of Foreign Languages of the Moscow Pedagogical State University Oksana Danchevskaya, in an interview with RT, noted that the Indians were granted the status of sovereign peoples. This step allowed the authorities to sign agreements with them on an equal footing, which became one of the main components of the American-Indian policy.

“During the so-called treaty period (from 1778 to 1887. - RT ) about 500 treaties were concluded between the United States and a number of tribes. All of them were then violated by the American government,” Danchevskaya said.

All of them were then violated by the American government,” Danchevskaya said.

Related

“The Indians were considered expendable”: how the leader Tecumseh became a victim of the confrontation between Washington and London

On October 5, 1813, the leader of one of the largest Indian unions, Tecumseh, was killed in a battle with the US troops. According to historians, he...

In the early 19th century, after long wars, the US federal government made treaties with five Indian peoples considered "civilized" (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole). According to these agreements, the Indians, in exchange for some territorial concessions, received the right to perpetual use of their lands in the southeast of the modern United States.

But already in 1823, the US Supreme Court declared all the territories of the indigenous population "no man's land", and seven years later the authorities passed a law on the eviction of the Indians. Under the new regulation, all Native Americans, including "civilized" peoples, had to leave the territories east of the Mississippi River and resettle on the steppes of present-day Oklahoma.

Under the new regulation, all Native Americans, including "civilized" peoples, had to leave the territories east of the Mississippi River and resettle on the steppes of present-day Oklahoma.

In 1831, the US Army forcibly drove a significant portion of the "civilized" Indians to the west. Many of them died on the way from hunger, cold and disease. This deportation is known among historians as the "road of tears". The remaining Indians resisted for a while, but by the end of the 19th century, only a small handful of the Seminole people, who had settled in the swamps of Central Florida, refused to comply with Washington's demands. All other Indians left the eastern part of the USA.

In 1851, the government of the country passed a law according to which the tribes living west of the Mississippi also lost their lands and were subject to relocation to reservations. In the second half of the 19th century, the seizure of their territories in the center and southwest of the North American continent began. The Indians, who lived on the Great Plains and in the mountainous regions on the border with Mexico, offered fierce resistance to the invaders. The war with them dragged on for about 40 years.

The Indians, who lived on the Great Plains and in the mountainous regions on the border with Mexico, offered fierce resistance to the invaders. The war with them dragged on for about 40 years.

- "Road of Tears" - the deportation of "civilized" Indians to the western United States

- © Robert Lindnö

In the course of the so-called land races, the American authorities distributed to their citizens the territories previously transferred to the "civilized" peoples of Oklahoma. The troops suppressed the resistance of the Lakota, Arapaho, Chayenne, Comanche and Apache Indians. Soldiers killed old people, women and children in Indian camps. The native inhabitants of the prairies inflicted several defeats on the military and achieved a truce. However, after the construction of the First Transcontinental Railroad and the destruction of the bison, which served as a source of food for the Indians of the Great Plains, resistance was crushed.

The Indian Wars officially ended in 1890 with the assassination of one of the most respected Lakota chiefs, Sitting Bull, and the massacre at Wounded Knee, which claimed the lives of approximately 300 Indians. From the formation of the United States until the end of the 19th century, the authorities took away from the indigenous people about 600 million hectares of land. By the beginning of the 20th century, only about 250 thousand Indians remained in the United States.

"Legal confusion"

Oksana Danchevskaya recalled that in 1868 the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was adopted, which granted citizenship to all natives of the United States. It did not apply to a single category of the population - members of Indian tribes.

Three years later, the US authorities passed a law that removed the status of "sovereign peoples" from Indian tribes. Writer and historian Yury Stukalin said in an interview with RT that "the situation with the situation of the indigenous people has become chaotic from a legal point of view. " According to the expert, the Indians were under the jurisdiction of the United States government, but were deprived of civil rights.

" According to the expert, the Indians were under the jurisdiction of the United States government, but were deprived of civil rights.

Related

Systemic isolation: will the indigenous population of North America be able to leave the reservations

260 years ago in North America, in the area of the town of Shamong, the first reservation for the Indians was created. So it was...

Danchevskaya adheres to a similar point of view. The expert noted that "the Indians had a dual status during this period." This state of affairs continued for more than 50 years.

“On the one hand, they were oppressed in every possible way and their rights were not considered, on the other hand, the US authorities gradually developed the regulatory framework associated with them. It should be noted that some of the Indians received citizenship during this time through military service, marriage and assimilation,” the candidate of cultural studies emphasized.

According to Danchevskaya, the First World War was a powerful catalyst for the process of granting rights to indigenous peoples.

"Many Indians served in the military, the indigenous population participated in all the wars fought by the United States," she added.

In 1924, the US Parliament, at the suggestion of Congressman Homer Snyder, passed the Indian Citizenship Act. On June 2, it was signed by President John Calvin Coolidge Jr.

- Indian Citizenship Act 1924 year

- © archives.gov

According to Stukalin, the natives were given citizenship, but it was not entirely clear what to do with it.

"Many whites still did not consider the Indians to be people," the historian noted.

Despite the fact that formally, along with citizenship, the natives were supposed to receive all the rights due to white Americans, there were problems with this at the state level.