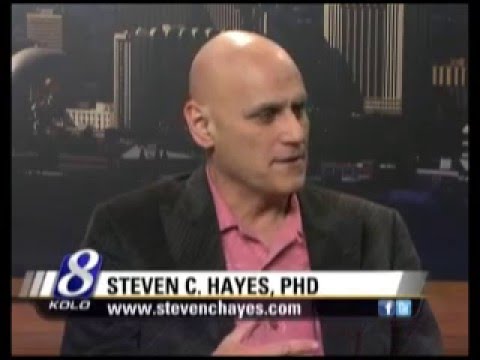

Acceptance and commitment therapy steven hayes

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Interview with Steven Hayes

Why ACT?

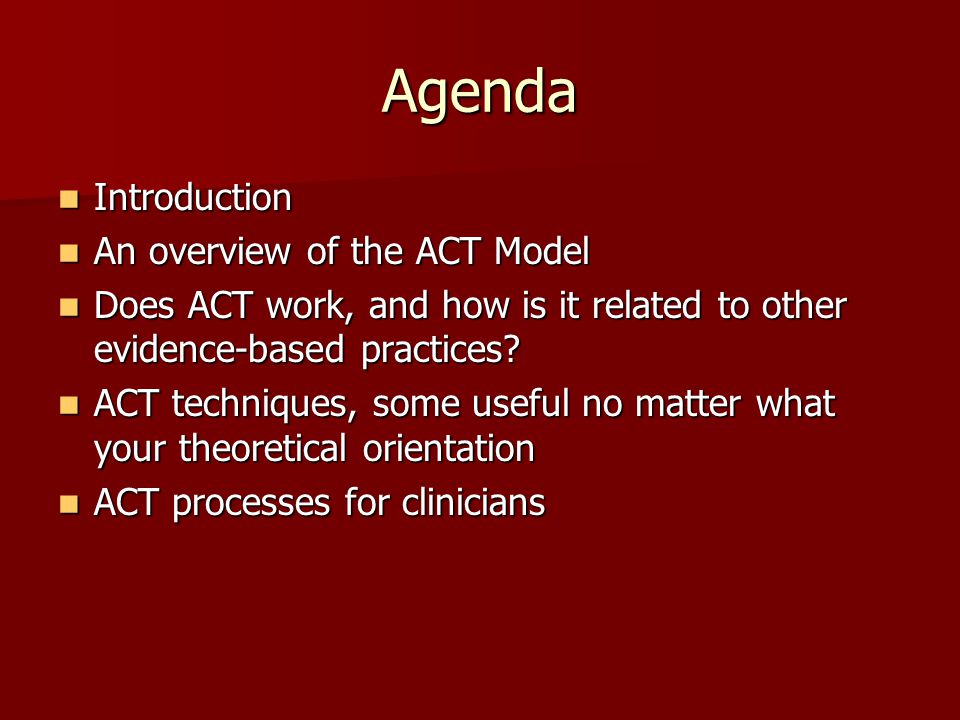

Tony Rousmaniere: In your experience, why do seasoned therapists who may already be proficient in other therapeutic modalities choose to learn ACT? What does ACT offer them that’s different?

Steven Hayes: I think there are a few main things that ACT offers. One is you can deal with deeper clinical issues, but inside of a model that feels progressive, so when you’re pushing into new territory, you have a road map that actually feels coherent. Another piece is that it’s personally relevant to people when they’re facing issues of their own. It’s kind of critical that we do work that does not feel false or hollow in some way, and almost all the ACT practitioners I know feel uplifted by the work when they’re struggling in their personal lives. They see the relevance.

I was giving a talk in England a few years ago and there was a person there from England’s evidence-based treatment program who asked that same question of the audience. Many of them shared that it’s fun to be part of a community that doesn’t speak down to you and that engages your intellectual interests in a number of different ways. People are able to integrate their interests in philosophy, evolutionary biology, social change and transformation, stigma and prejudice into their ACT work, which is unusual.

I think a lot of our psychotherapies have gotten way too focused on DSM disorders and things of that kind, especially the more evidence-based ones, and less interested in the broad application of behavioral science to all kinds of issues around human behavior. There’s a surprising number of people, for example, who are interested in Relational Frame Theory. It’s difficult material, very geeky, and doesn’t seem like something clinicians would be interested in. In fact, they’re not initially interested in it but as the work speaks to them, they become interested in it. Why is language like this? Why are our minds like this? Why does this model work? There’s also a community of scientists in ACT who are coming to conferences and presenting their work. It’s just kind of fun to be part of a group that has that aspect to it.

It’s just kind of fun to be part of a group that has that aspect to it.

TR: How about therapists coming from CBT or just a purely behavioral angle? Is it challenging for them to move towards the philosophical side of things?

SH: Part of what’s interesting about ACT is, when you go to an Association for Contextual Behavioral Science conference, which is the ACT community, there’s kind of a fruit-nut-seed mix of people there. There’s people from the gestalt, existential and humanistic side of things as well as behavioral and CBT folks. Because ACT sort of emerged out of behavior analysis, it includes some pretty hardcore Capital B behavioral people. Of the various groups, though, I think it’s hardest for traditional CBT folks because we’ve waved people off of some popular CBT methods that we just don’t think are very important or produce good outcomes. Especially detecting, challenging, disputing and changing cognitions—it’s just not something that we do very much at all. It can be hard for them to let go of these methods and can take some time to adjust.

It can be hard for them to let go of these methods and can take some time to adjust.

We may do psycho education and cognitive reappraisal, but it’s just too dangerous and too close to things that are going to be too hard to do and that clients are going to sometimes misuse. You would think that the behavioral folks would really hate the philosophical aspect of ACT, but actually they like it a lot because they can see the connection to their tradition. And having a way to deal seriously with cognition that isn’t dismissive or reductionistic is kind of a relief to them.

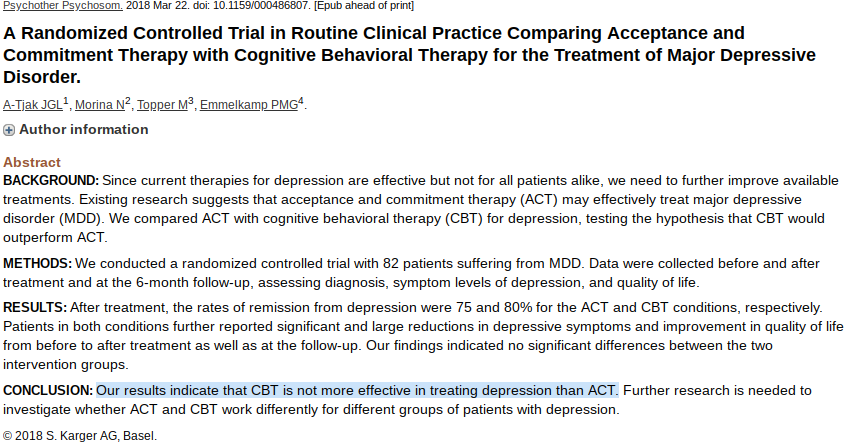

TR: ACT is considered an evidence-based treatment?

SH: Yes, ACT and many others. I mean, Motivational Interviewing is really Rogerian thinking scaled up into evidenced-based care. People are increasingly required in agency after agency and state after state to show that their practices are evidence-based, and that’s probably even more true worldwide. There are some parts of Europe where you basically can’t practice unless you are doing things that are on a list of evidence-based treatments.

Motivational Interviewing is really Rogerian thinking scaled up into evidenced-based care.

ACT processes and procedures allow you to fit what you’re doing to the needs of an individual and create things on the fly and do things that make sense to you clinically, and yet know that you’re practicing inside an evidence-based care framework. It’s nice to not have to check your mind at the door and leave behind some of the deeper clinical issues that interest you. You don’t have to minimize or dismiss the complexity of human beings in order to make it on the list of evidence-based treatments.

If You're Note Busy Being Born, You're Busy Dying

TR: You mentioned that ACT is a progressive model. Can you give a concrete example of what that means or how that would appear in the work of therapy?

SH: There’s a tendency for us as therapists to get into a groove clinically speaking, with our personal style and our knowledge, and settle into it. It’s not a bad thing, but there will always be curve balls thrown by cases that we can’t reach, patients we don’t know how or what to do with, complexities that don’t yield to our methods. And if you’re not busy being born, you’re busy dying, to quote a Dylan song. So the kind of progressivity I’m talking about is the sense that we as individuals and as a field are getting better and better and more and more able to deal with what is complex and difficult, while not having to check what you already know works at the door.

It’s not a bad thing, but there will always be curve balls thrown by cases that we can’t reach, patients we don’t know how or what to do with, complexities that don’t yield to our methods. And if you’re not busy being born, you’re busy dying, to quote a Dylan song. So the kind of progressivity I’m talking about is the sense that we as individuals and as a field are getting better and better and more and more able to deal with what is complex and difficult, while not having to check what you already know works at the door.

So many of our evidence-based approaches basically ask people to buy in whole cloth to everything that some founder came up with. I don’t think that’s necessary, healthy or even reasonable frankly. I like to say to people when they get interested in ACT, “You’re going to find your own work inside this work. There’s a reason why you’re here, and if that’s not true then you should walk away from it.” Once you see that connection you can build on it. You can do new things and the entire community will support you.

I think our communitarian approach is one of the reasons ACT has developed so much over the years.

I think our communitarian approach is one of the reasons ACT has developed so much over the years. People bring these different ideas in and we keep adding things, subtracting things, modifying things, and extending things so there’s the sense that we’re doing more and doing better and that we’re all part of it. That’s the sort of progressivity I’m talking about.

Being part of a knowledge-development community is an exciting thing. If you look at the people who are active in the ACT world, we’re out there as trainers and writers, scientists and researchers and really sophisticated clinicians. We’re moving forward in a way that’s networked. I call it a reticulated model, meaning a web or a network where each little node has their part of the task of getting better as we move forward.

The DSM Kool-Aid

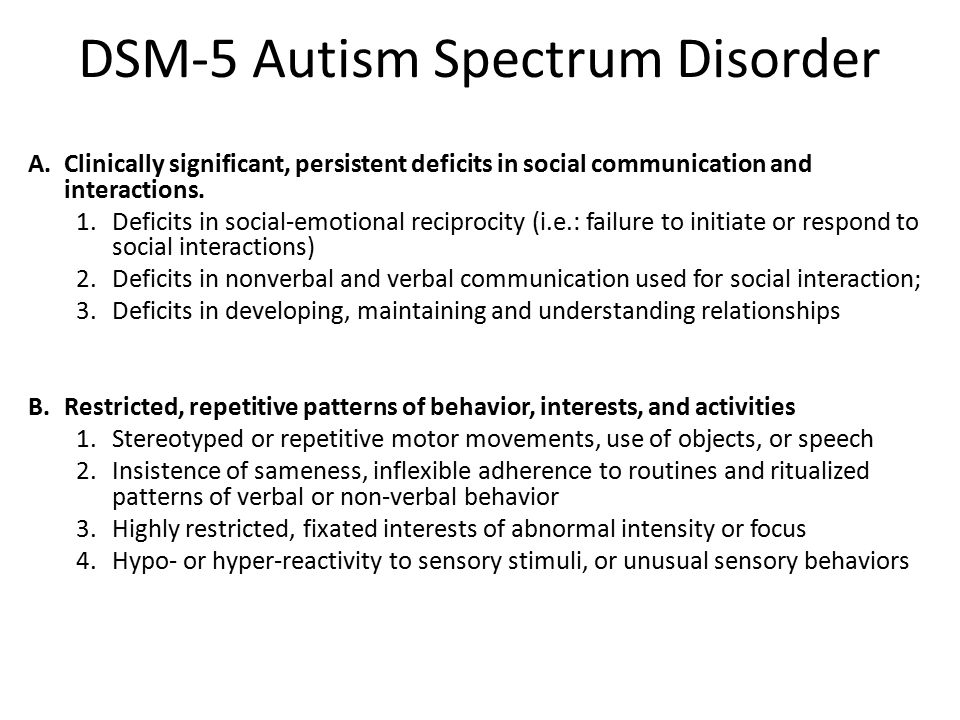

TR: ACT has much less of a focus on psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses than many or most other modalities. Can you talk about that and also your thoughts about the changes to the new DSM-5?

Can you talk about that and also your thoughts about the changes to the new DSM-5?

SH: We never did drink the Kool-Aid that was offered from the DSM-III onward. Not that it’s not of some use, of course, to have some sort of terminology or nosology, but it got way overextended. We don’t have any functional entities inside these syndromes. No diseases—none—have emerged. And that’s the whole point of that syndromal game—to lead you to an etiology so you can respond with proper treatment. An honest examination of it points to it being a billion dollar failure.

We never did drink the Kool-Aid that was offered from the DSM-III onward....ACT work is based more on the psychology of the normal.

ACT work is based more on the psychology of the normal. I think we have every reason to believe that most of the things that people struggle with are based on the failure to bring out normal psychological processes. Not that there aren’t abnormal processes, of course there are. But if you take, for example, our tremendously useful human capacity to problem-solve, analyze, categorize, predict and evaluate things—this process, when applied to the world within, can become very toxic. It turns your life into a problem to be solved. Once you start focusing on your sadness or your anxiety or your urges, your problem-solving processes are going to be anywhere between unhelpful and pathological. They’re going to increase your focus on things that are just a small part of what’s going on and create these kind of self-amplifying loops—like, the more you try not to think of things, the more you actually think of them.

But if you take, for example, our tremendously useful human capacity to problem-solve, analyze, categorize, predict and evaluate things—this process, when applied to the world within, can become very toxic. It turns your life into a problem to be solved. Once you start focusing on your sadness or your anxiety or your urges, your problem-solving processes are going to be anywhere between unhelpful and pathological. They’re going to increase your focus on things that are just a small part of what’s going on and create these kind of self-amplifying loops—like, the more you try not to think of things, the more you actually think of them.

If you focus on the psychology of the normal as we have, we think that experiential avoidance accounts for about 25 percent of the variance in almost all of the major syndromes. But it also accounts for whether or not you can learn a new software program or are comfortable in your relationships and so on. We have to dig down and see what these processes are and how can we rein them in, because it isn’t possible—nor would we even want to—eliminate them.

Problem solving, for example, is just too darned useful for us to check at the door, but we need to learn how to respectfully decline our mind’s invitation to use our problem-solving repertoire for our normal flow of emotional and cognitive events. That’s very hard to do, but people can learn to do that. The mindfulness folks have learned a number of methods for doing it and we’ve found some additional tools that people can integrate into their lives pretty easily. Using these tools people can become more psychologically flexible, more able to shift their attention from fear and avoidance to what they most deeply care about and want from their lives.

We need to learn how to respectfully decline our mind’s invitation to use our problem-solving repertoire for our normal flow of emotional and cognitive events.

So our approach—instead of the DSM medicalization of human suffering—is to try to dig into the processes that narrow human lives or expand them, and to learn how to measure them so that we can begin to train people to use them to evolve forward. People don’t go into therapy when life is moving forward at a reasonable clip; they go in when life is stuck or going backwards. And it’s not that they get cured or fixed, because humans are not broken, they don’t need to be fixed. They need to be supported in a way that allows them to grow and do a better job over time with the things that they really care about—their kids, their work, their intimate relationships, their sense of participation and connection with the world around them. That’s just not going to be found inside a syndromal model. It doesn’t mean you can’t draw on genetics, epigenetics, physiology and neuroscience in formulating your treatment, but not with the mindset that we’re discovering abnormal processes.

People don’t go into therapy when life is moving forward at a reasonable clip; they go in when life is stuck or going backwards. And it’s not that they get cured or fixed, because humans are not broken, they don’t need to be fixed. They need to be supported in a way that allows them to grow and do a better job over time with the things that they really care about—their kids, their work, their intimate relationships, their sense of participation and connection with the world around them. That’s just not going to be found inside a syndromal model. It doesn’t mean you can’t draw on genetics, epigenetics, physiology and neuroscience in formulating your treatment, but not with the mindset that we’re discovering abnormal processes.

What we’re actually discovering is the richness of human experience and what moves you forward and moves you back and how can we get evidence-based processes linked to evidence-based procedures that can be used creatively by competent clinicians. Not to fix you but to get you over that hump. From there we have a kind of family dentist model—if you run into problems again, if you find yourself in a cul-de-sac, come on back in. Part of what’s exciting about ACT work is that anybody who responds to it is likely to respond even faster the next time around because the same basic processes show up over and over again. Often just reminding people of the progress that they’ve made in the past by learning to be more open, more aware, and more actively engaged in their values is enough to get them over the new barrier that they’ve run into in their life.

From there we have a kind of family dentist model—if you run into problems again, if you find yourself in a cul-de-sac, come on back in. Part of what’s exciting about ACT work is that anybody who responds to it is likely to respond even faster the next time around because the same basic processes show up over and over again. Often just reminding people of the progress that they’ve made in the past by learning to be more open, more aware, and more actively engaged in their values is enough to get them over the new barrier that they’ve run into in their life.

Treating Addiction with ACT

TR: I’ve seen a bunch of literature recently on using ACT with addictions. What’s the ACT approach to addictions?

SH: It’s an exciting area. There are about 10 or 12 controlled studies on ACT with addictions—several very powerful ones on smoking and now some in other areas of addictive behavior. In a recent study we published in The Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology titled, “Reducing Shame in Addictions: Slow and Steady Wins the Race,” we showed that you can focus ACT methods on reducing shame and self-stigma. We did a randomized trial at an inpatient unit comparing it to 12-step oriented inpatient care, and ACT interventions resulted in fewer days of substance use and higher treatment attendance at follow up.

We did a randomized trial at an inpatient unit comparing it to 12-step oriented inpatient care, and ACT interventions resulted in fewer days of substance use and higher treatment attendance at follow up.

When dealing with severe substance abuse, working with shame is critical because people have done a lot of damage, not just to themselves but to their families, their children, their work, to the things they care most about. You don’t get into a 28-day inpatient program in the modern era—at least, not in Nevada where it’s cowboy conservatives—without creating some real wreckage. You’ve probably lost your job and all the rest, and most likely someone else is footing the bill for your treatment.

Guilt actually predicts positive outcomes in substance abuse, but shame does not.

Guilt actually predicts positive outcomes in substance abuse, but shame does not. When you’ve done things that are harmful to others, guilt is a perfectly appropriate emotion; it’s something to have and experience and it can help reorient you toward what’s important in your life and what you can do to clean up the mess you have made. What shame adds on is the “I’m bad” piece—the kind of fused conceptualization of oneself as a broken organism. That’s toxic and it predicts bad outcomes.

What shame adds on is the “I’m bad” piece—the kind of fused conceptualization of oneself as a broken organism. That’s toxic and it predicts bad outcomes.

The normal, reasonable way that a human mind tries to resolve this problem is to talk itself out of shame. The Stuart Smalley solution: “Gosh darn it, I’m good enough and people love me.” But that’s a form of suppression and it can blow up like a house of cards when people leave treatment because it’s not grounded in a deeper set of values.

What we did initially in our groups was to slow things down, to learn to just watch the mind, watch all the chatter and finger wagging and shame and blame coming up, and then dig into the part that’s useful and let go of what’s not. It sobers people up in a way.

There’s kind of a humbling that takes place when you inhale into the pain of your own history and your own addiction and then make that leap of openness.

There’s kind of a humbling that takes place when you inhale into the pain of your own history and your own addiction and then make that leap of openness. You know, “I’m willing to take a leap of faith that I’m big enough to have this feeling,” and then the intentional flexibility inside a more mindful place to now shift my attention towards what I deeply care about. Then one step at a time, one day at a time—how am I going to get there? This resonates with some of the deeper parts of the Twelve-Step tradition. There’s nothing in the Twelve-Step program, or at least what I see in the Big Book version of it, that contradicts ACT, but these principles are not always what’s being applied in treatment facilities.

You know, “I’m willing to take a leap of faith that I’m big enough to have this feeling,” and then the intentional flexibility inside a more mindful place to now shift my attention towards what I deeply care about. Then one step at a time, one day at a time—how am I going to get there? This resonates with some of the deeper parts of the Twelve-Step tradition. There’s nothing in the Twelve-Step program, or at least what I see in the Big Book version of it, that contradicts ACT, but these principles are not always what’s being applied in treatment facilities.

For the folks participating in our ACT groups, their shame levels actually went down more slowly, but they continued to go down after treatment and their outcome rates were better. For those not in our groups, their shame levels went down more quickly while they were in treatment, but their recidivism rates were higher after treatment.

TR: So mindfulness work is really essential to ACT and specifically to this process of decreasing shame?

SH: Very much so. What’s true about any mindfulness work is that, if you’re going to open up, you’re going to see dark places. You can’t hide from yourself like you used to. Hiding from yourself created problems, but opening your eyes and being with yourself and watching your emotions rise and fall, being more honest about what you’re feeling, sensing, remembering, thinking—that’s also going to be difficult. I don’t think it’s by accident that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy works pretty well for people who have had depression three or more times, but is arguably inert for people who’ve only had a single depressive episode. Because if you’re going to open the door to the basement and go walking down into the basement you’re going to see stuff down there that’s not for the faint of heart.

What’s true about any mindfulness work is that, if you’re going to open up, you’re going to see dark places. You can’t hide from yourself like you used to. Hiding from yourself created problems, but opening your eyes and being with yourself and watching your emotions rise and fall, being more honest about what you’re feeling, sensing, remembering, thinking—that’s also going to be difficult. I don’t think it’s by accident that mindfulness-based cognitive therapy works pretty well for people who have had depression three or more times, but is arguably inert for people who’ve only had a single depressive episode. Because if you’re going to open the door to the basement and go walking down into the basement you’re going to see stuff down there that’s not for the faint of heart.

If you’re going to do this kind of work you’re going to find pain within you and without; you’re going to see injustice, you’re going to see suffering around you. You’re going to walk into the grocery store and you’re going to see people who don’t have enough money to buy the groceries they need. You’re going to see people walking by you who have a hard time taking a next step because they’re old and in physical pain. You start opening up to a more varied kind of perspective on yourself and others that I think is more honest.

You’re going to see people walking by you who have a hard time taking a next step because they’re old and in physical pain. You start opening up to a more varied kind of perspective on yourself and others that I think is more honest.

But we dare not take these Eastern traditions and simply throw them into our Western minds with the idea that we’re going to relax and walk around with a big smiley face all the time. It’s a richer soup than the kind that our western commercial culture is giving us and our children, but it’s a hard path. This study we did with shame and addiction sort of shows that giving people a healthy way to walk that path is slower, but it’s more surefooted. So we’re bringing something new, I think, to the addiction field that as it becomes more known will be helpful to people working with addictions.

“It’s Not a Happy-Happy, Joy-Joy Bliss Trip”

TR: It’s interesting what you say about mindfulness opening your eyes to some of the darker things in the world. Sometimes when I hear therapists or others talking about mindfulness and meditation it seems like they’re talking about a pleasure cruise to bliss land or this image of the Buddha looking all happy. It sounds like that’s not what you mean in ACT.

Sometimes when I hear therapists or others talking about mindfulness and meditation it seems like they’re talking about a pleasure cruise to bliss land or this image of the Buddha looking all happy. It sounds like that’s not what you mean in ACT.

SH: It isn’t and frankly it’s a distortion of those traditions. Taking a compassionate approach to yourself and others only really makes sense if you know how hard that is. If it’s not connected to the pain for which compassion is useful, then it’s just another suppressive, self-delusional trip. It’s a sort of psychological tranquilizer that is undermining what it’s there for and what I think we need right now.

Science and technology are creating such a challenge for us now that we can instantly see all the horrific things happening in the world on our screens. Those destroyed homes left in the wake of the Oklahoma tornado, the Boston Marathon bombings, the faces of the Newtown victims—your children are seeing it on their screens and you can’t throw out enough televisions and iPhones and all the rest to protect them from it.

The amount of pain that we’re exposed to now is a magnitude higher than anything we evolved to face. Your great-grandparents didn’t see anything near the flow of horrific images and judgmental words and painful events that we do now.

The amount of pain that we’re exposed to now is a magnitude higher than anything we evolved to face. Your great-grandparents didn’t see anything near the flow of horrific images and judgmental words and painful events that we do now. So we need modern minds for this modern world, but it’s not a happy-happy, joy-joy, bliss trip to the beach kind of thing. It’s much more serious and sober. Not serious in the sense that it’s not fun and joyful to be alive and connected, but in the sense that it does justice to the richness of human life. And it’s right in there from an ACT point of view.

We have a saying: “In your pain you find your values and in your values you find your pain.” When you connect with things that you deeply care about that lift you up, you’ve just connected yourself into places where you can and have been hurt. If love is important to you, what are you going to do with your history of betrayals? If the joy of connecting to others is important to you, what are you going to do with the pain of being misunderstood or failing to understand others? The acceptance and mindfulness work doesn’t self-soothe and makes all of that easy; instead it gives us the openness and grounding and consciousness to be able to move our attention in a non-suppressive way towards what we care about. It empowers us to take that leap of faith that we can care, that we can have values and nobody can stop us. Like Viktor Frankl wrote about, you can take away all of my external freedoms but you can’t take away my capacity to choose to love and care about others. You just can’t do it.

If love is important to you, what are you going to do with your history of betrayals? If the joy of connecting to others is important to you, what are you going to do with the pain of being misunderstood or failing to understand others? The acceptance and mindfulness work doesn’t self-soothe and makes all of that easy; instead it gives us the openness and grounding and consciousness to be able to move our attention in a non-suppressive way towards what we care about. It empowers us to take that leap of faith that we can care, that we can have values and nobody can stop us. Like Viktor Frankl wrote about, you can take away all of my external freedoms but you can’t take away my capacity to choose to love and care about others. You just can’t do it.

With meditation, the artificial anxiety that we pump into our lives sometimes recedes very quickly, and that’s fine. But people sometimes make the mistake of becoming mindfulness junkies. That’s the psychological equivalent of a tranquilizer and it’s an abuse of the traditions. Yet I worry that many therapists use it in just this way. It’s important to have the added dimension of values and caring and compassion and participation and making a difference.

Yet I worry that many therapists use it in just this way. It’s important to have the added dimension of values and caring and compassion and participation and making a difference.

TR: Speaking of making a difference, there’s a social justice component of ACT that I haven’t heard of in very many other therapeutic modalities. Can you describe this a bit more and also maybe some specific examples of how it’s being utilized to help people?

SH: I think that’s kind of a natural extension of ACT. The same cognitive processes that allow us to have a sense of transcendence or oneness or consciousness—the I-here-nowness of consciousness itself—are based upon the ability to see the world through other people’s eyes. So it isn’t just “I,” it’s “I/You.” There’s a social extension of consciousness that happens right in the process of becoming more aware of your own processes in which you begin, suddenly, to become aware of the fact that people around you are suffering. We can model this in the lab, actually. We use Relational Frame Theory methods with kids who don’t have a sense of self, and very soon empathy begins to emerge. When I see from my eyes, it happens at the same moment that you see from yours. When I learn to feel my feelings as feelings, it happens at the same moment that I see that you have feelings—that you’re feeling, too.

We can model this in the lab, actually. We use Relational Frame Theory methods with kids who don’t have a sense of self, and very soon empathy begins to emerge. When I see from my eyes, it happens at the same moment that you see from yours. When I learn to feel my feelings as feelings, it happens at the same moment that I see that you have feelings—that you’re feeling, too.

The natural extension of that process then is, if I’m going to be more accepting of my emotions and try to walk with them in a values-based way, what about the difficult emotions that other people are experiencing because of things that have happened to them? This is not a kind of mindfulness work that’s alone and cut off and sort of in the corner; it extends across time, place, and persons.

Objectification, dehumanization and prejudice naturally connect to things like self-stigma. I mentioned that we’ve done that kind of work with addicts, but we’ve also done it with LGBT populations, with victims of racial and religious prejudice. It’s the natural, reasonable, sensible thing to take the next step toward reining in the parts of the mind that lead us to objectify and dehumanize others.

It’s the natural, reasonable, sensible thing to take the next step toward reining in the parts of the mind that lead us to objectify and dehumanize others.

Can we bring a more compassionate and values-based world into existence, starting with ourselves and then extending it out?

Can we bring a more compassionate and values-based world into existence, starting with ourselves and then extending it out?

In our research on experiential avoidance, we’ve found that part of the problem with people who are prejudiced towards others is that they are unable to take in the perspective of others. They get overwhelmed by seeing the pain of others and would rather objectify and dehumanize them than feel what they would have to feel to know what it’s like to be them. We’ve shown the same thing with social anhedonia; you don’t care about being around others unless you have the big trio of good perspective-taking, empathy towards others and not running away from pain. So you can see how the model naturally leads us to a concern for issues of social justice. In a way it’s one and the same.

So you can see how the model naturally leads us to a concern for issues of social justice. In a way it’s one and the same.

I can’t cut myself off from others and objectify and dehumanize others except by attacking the processes that allow me to be more open and accepting of myself.

I can’t cut myself off from others and objectify and dehumanize others except by attacking the processes that allow me to be more open and accepting of myself.

And that gives us a way in because nobody goes into therapy saying, “Gee, I’m a bigot. What can you do for me?” But they do come in saying, “I feel distressed. I feel disconnected. I feel far away.” And it turns out that objectification and dehumanization of others produces those results for the individual.

This happens with us, too, as clinicians. You know the kind of dark humor that happens in the staff room—“Oh, Sally the Borderline has shown up.” “Oh, God! Not Sally.” I understand why people do it and don’t mean to wag my finger, but it comes very close to objectifying clients, dehumanizing them as a defense against the pain of not being able to reach them. These kinds of attitudes predict burnout and ultimately minimize your ability to make a difference with others.

These kinds of attitudes predict burnout and ultimately minimize your ability to make a difference with others.

TR: It’s so interesting to think of therapists as social change agents. Have you done research in this area too?

SH: Our very first randomized trial in the modern era—because we had a few in the ‘80s, then we went dark for 15 years while we worked out the basic model and the theory of cognition and the measures for fear—was done by a guy named Frank Bond at the University of London. He did research with people who were working in call centers in banks—a very tough job, a lot of pressure and very little pay. He compared ACT to a program that was encouraging people to take charge of the stressors in their environment and make changes so that their environment was more supportive. ACT was a more psychological model, obviously, and when people got more open and accepting and values-based, they started demanding work changes of their foremen. The thing that was keeping people small and keeping them in a box was fear—“What will my boss think if I raise this issue?’”

The thing that was keeping people small and keeping them in a box was fear—“What will my boss think if I raise this issue?’”

The values piece activated people and I’m proud of the fact that when you do the kind of work that we’re doing, you empower people who are downtrodden or on the short end of the stick. We’ve shown this in several studies, that If you are more open to your feelings, more conscious, more aware, more mindful, and more linked to your values, you will be more empowered to step up. We’re doing that now with racial minorities, ethnic minorities, religious minorities and also with a message for those who are in a majority status but who care about these issues.

Psychotherapists have a role to play not just in the area of mental health, but in social justice as well.

Psychotherapists have a role to play not just in the area of mental health, but in social justice as well.

There’s a richer journey there and I think a lot of therapists are frustrated just dealing one person at a time at a time with the results of a society that just doesn’t know how to support people in being more fully human. You can be in your therapist role but also be part of a social change effort that is linked directly to the clinical work that you’re doing.

You can be in your therapist role but also be part of a social change effort that is linked directly to the clinical work that you’re doing.

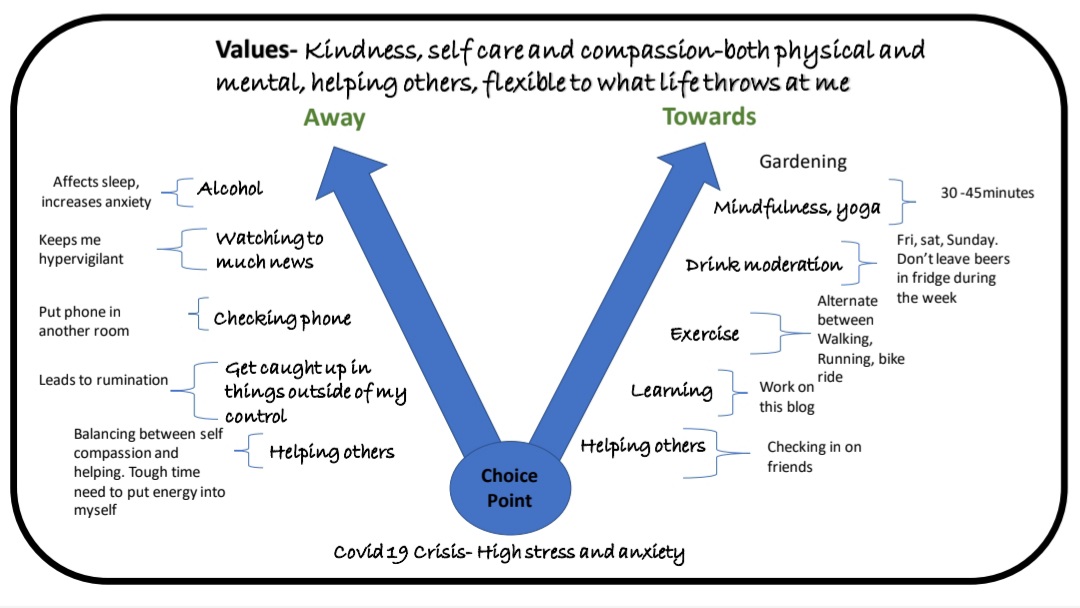

Running Towards Values

TR: It seems like you’re working to shift the focus away from symptom avoidance and towards values. Does that sound right?

SH: Exactly. A whole person running towards values—not in a suppressive or avoidant way in order to feel less of anything. There’s no delete button. In the language of mathematics, this is addition and multiplication, not subtraction and division. If people can learn how to add and multiply and open up, it’s deeply empowering.

TR: I saw on your website that you’re doing a study looking at the training effects of consultation groups. Is that right?

SH: Yes. People have begun to apply some of these very same processes of openness, mindfulness and values to training itself and we have now several studies showing that we can apply these methods to therapists and they will do a better job of learning. Psychological flexibility is important to us as learners and we’re looking carefully at training and studying it—not only how we train in ACT methods themselves, but also how we use ACT to train in a variety of psychotherapy and other processes that are helpful to us in our professional roles. It’s not simply a matter of learning a clinical technology; instead, we’re trying to create a knowledge development community that takes these processes and procedures wherever they can be of use to people.

Psychological flexibility is important to us as learners and we’re looking carefully at training and studying it—not only how we train in ACT methods themselves, but also how we use ACT to train in a variety of psychotherapy and other processes that are helpful to us in our professional roles. It’s not simply a matter of learning a clinical technology; instead, we’re trying to create a knowledge development community that takes these processes and procedures wherever they can be of use to people.

TR: Thank you so much for taking the time to share your work with us here at psychotherapy.net.

SH: It’s been a pleasure.

Copyright © 2013 Psychotherapy.net. All rights reserved.

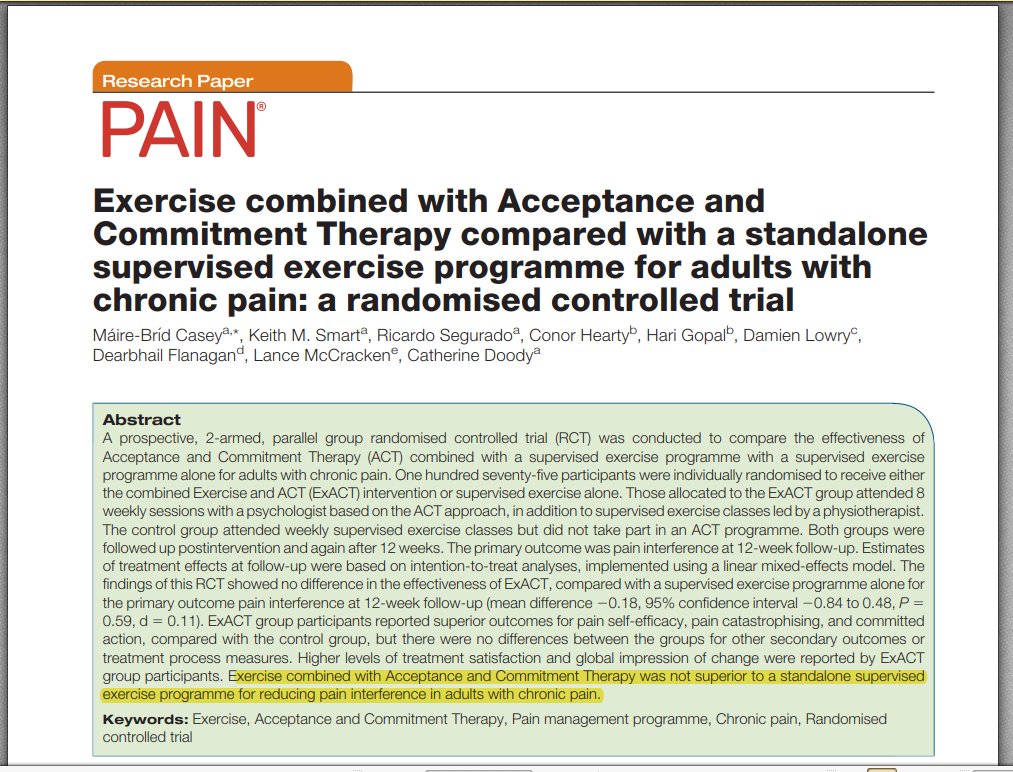

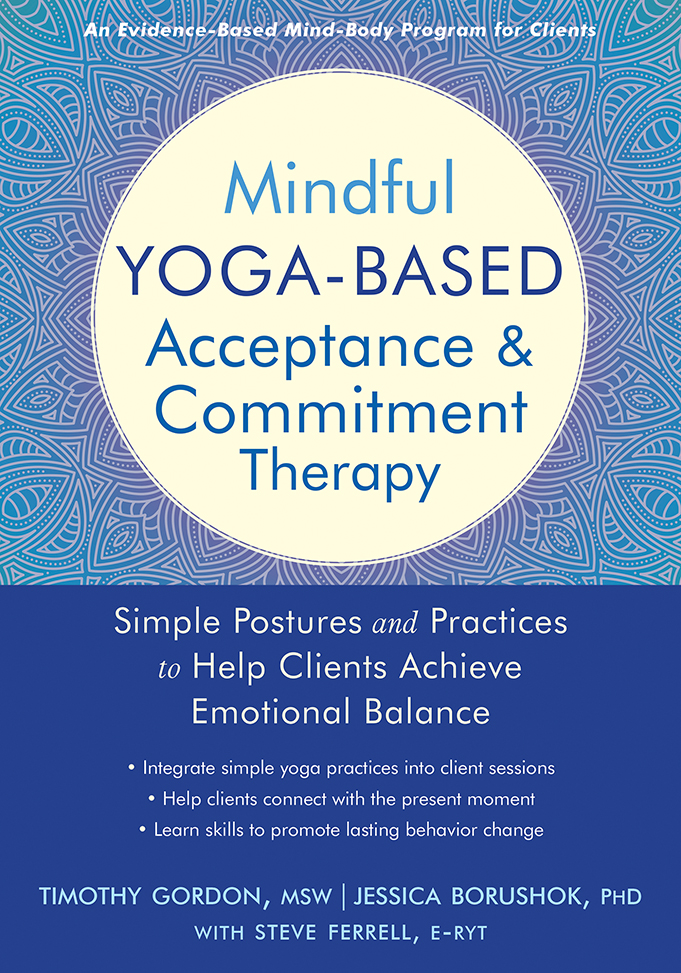

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Health Behavior Change: A Contextually-Driven Approach

Introduction

The pragmatic utility of psychological interventions on health behavior changes are judged by their effectiveness in promoting sustained and desired behavior change over an extended period of time. For example, effective interventions are not only those that get people to increase their steps per day or to eat a healthy meal, but also are those that maintain such gains months or years beyond the initial intervention. Mainstream health behavior change approaches have focused primarily on the content of cognitive and emotional variables that are thought to support long-term behavior change. Traditionally, health behavior change interventions target the social cognitive and belief-based variables to increase individuals’ intention (i.e., a person’s motivation toward the target behavior in terms of direction and intensity) and self-efficacy (i.e., one’s confidence in being capable of performing a novel behavior) in the hopes of maintaining the health behavior change (Schwarzer, 2008). While these approaches can be helpful to a degree, the magnitude of health problems and the maintenance of health behavior change suggests that alternatives are needed (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). One important approach that gains more and more momentum is to apply the context-driven approach to understand and predict health behavior change (Hayes, 2004).

For example, effective interventions are not only those that get people to increase their steps per day or to eat a healthy meal, but also are those that maintain such gains months or years beyond the initial intervention. Mainstream health behavior change approaches have focused primarily on the content of cognitive and emotional variables that are thought to support long-term behavior change. Traditionally, health behavior change interventions target the social cognitive and belief-based variables to increase individuals’ intention (i.e., a person’s motivation toward the target behavior in terms of direction and intensity) and self-efficacy (i.e., one’s confidence in being capable of performing a novel behavior) in the hopes of maintaining the health behavior change (Schwarzer, 2008). While these approaches can be helpful to a degree, the magnitude of health problems and the maintenance of health behavior change suggests that alternatives are needed (Kwasnicka et al., 2016). One important approach that gains more and more momentum is to apply the context-driven approach to understand and predict health behavior change (Hayes, 2004). In the current mini review, the authors aim to introduce the context-driven approach of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999) along with the description of how and why Relational Frame Theory (RFT; Hayes et al., 2001) and psychological flexibility provide coherent theoretical foundations and validated measures for ACT-based health behavior change. This should not be viewed as a detailed guidance and/or a systematic and comprehensive review, but more of a brief explanation and introduction focused on illustrating the links between the basic principles of ACT and related health behavior change.

In the current mini review, the authors aim to introduce the context-driven approach of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT; Hayes et al., 1999) along with the description of how and why Relational Frame Theory (RFT; Hayes et al., 2001) and psychological flexibility provide coherent theoretical foundations and validated measures for ACT-based health behavior change. This should not be viewed as a detailed guidance and/or a systematic and comprehensive review, but more of a brief explanation and introduction focused on illustrating the links between the basic principles of ACT and related health behavior change.

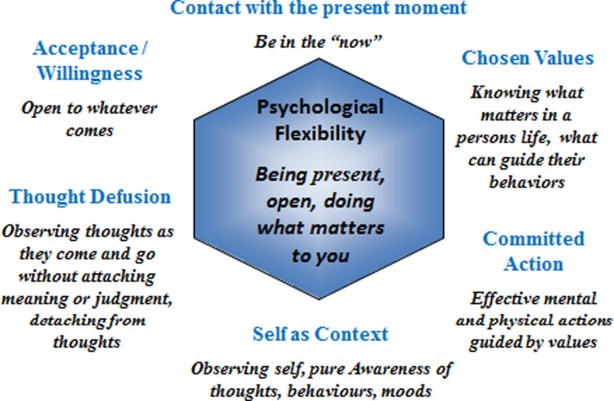

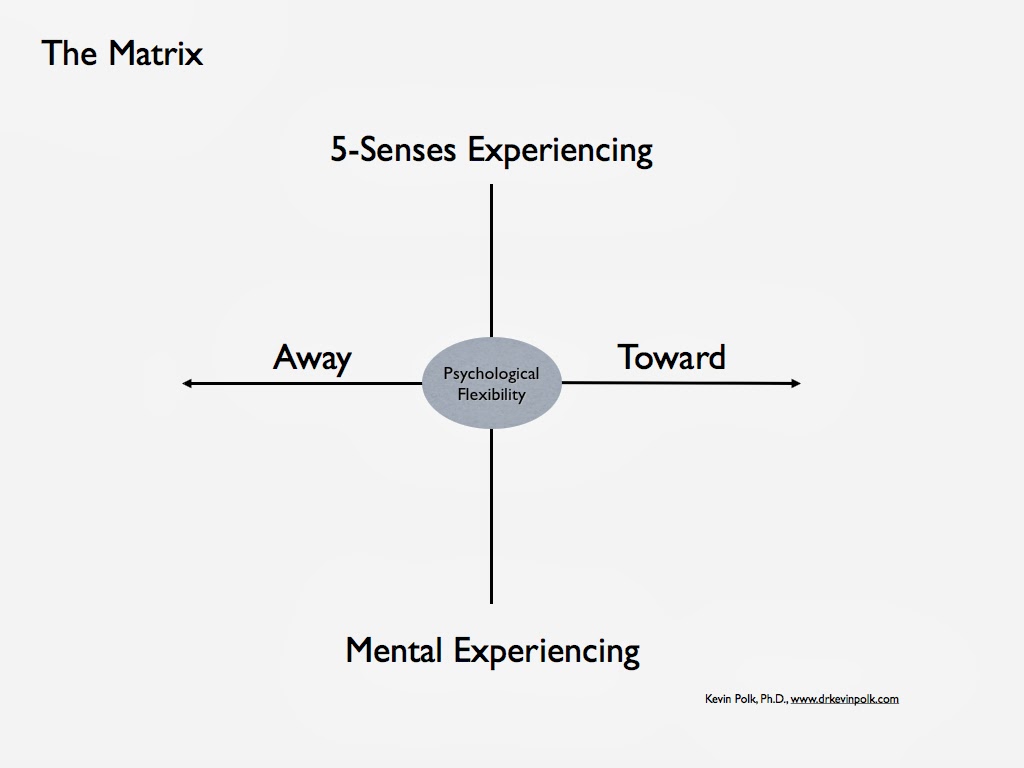

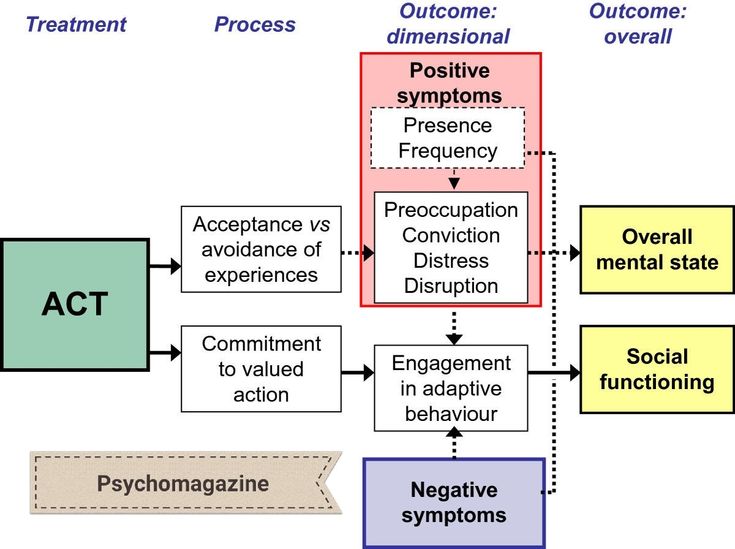

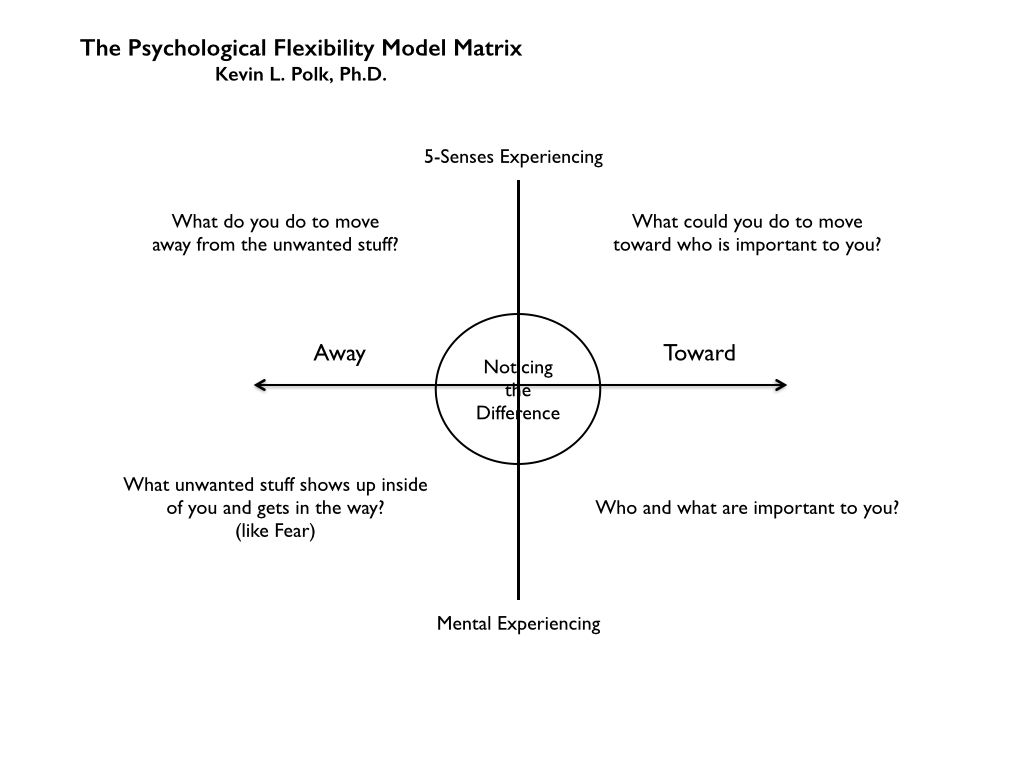

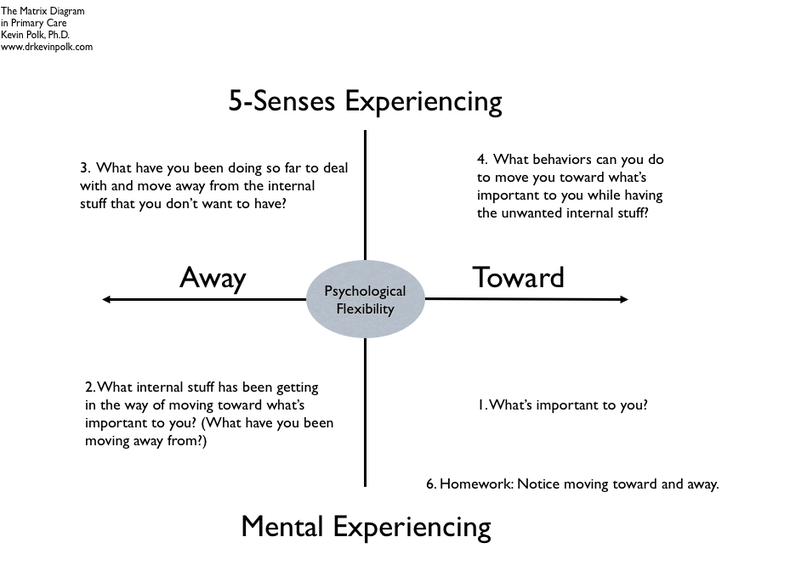

As compared to the content-driven approach, in which behavior change is based on thought content unique to each particular behavior (Ellis, 1962; Beck, 1976), a context-driven approach examines the social, psychological, and situational context that regulates the behavioral impact of thought and emotion (Hayes et al., 1999). For health behavior change, instead of trying to directly change difficult thoughts or feelings, acceptance and mindfulness-based skills can be cultivated to foster greater behavioral regulation. Perhaps the most studied set of contextual processes of this kind is psychological flexibility, which is “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being and to change, or persist in, behavior when doing so serves valued ends” (Biglan et al., 2008). Psychological flexibility is contextual in the sense that it refers to individuals changing their relationships with private events (i.e., thoughts, memories, feelings, and bodily sensations), not the events themselves. For example, psychological flexibility may focus on teaching a dieter to be mindful and observe an urge to eat a chocolate cake without necessarily attempting get rid of that urge. The content surrounding a temptation to eat something delicious may include such things as judgments about whether this urge is good or bad; psychological flexibility suggests that the focus should be on how the individual interacts with these thoughts, rather than their form or frequency. Accordingly, the ultimate goal for individuals, initiating and maintaining the health behavior change, is to make said change(s) consistent with their chosen values (e.

Perhaps the most studied set of contextual processes of this kind is psychological flexibility, which is “the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being and to change, or persist in, behavior when doing so serves valued ends” (Biglan et al., 2008). Psychological flexibility is contextual in the sense that it refers to individuals changing their relationships with private events (i.e., thoughts, memories, feelings, and bodily sensations), not the events themselves. For example, psychological flexibility may focus on teaching a dieter to be mindful and observe an urge to eat a chocolate cake without necessarily attempting get rid of that urge. The content surrounding a temptation to eat something delicious may include such things as judgments about whether this urge is good or bad; psychological flexibility suggests that the focus should be on how the individual interacts with these thoughts, rather than their form or frequency. Accordingly, the ultimate goal for individuals, initiating and maintaining the health behavior change, is to make said change(s) consistent with their chosen values (e. g., having a healthy lifestyle) even in the face of difficult thoughts or emotions.

g., having a healthy lifestyle) even in the face of difficult thoughts or emotions.

Health behavior change is a dynamic process. Psychological flexibility has much to offer in the context of health behavior change as a theoretical guide for cultivating long-term improvements in behavior. According to Kashdan and Rottenberg (2010), four aspects of psychological flexibility can be viewed as fundamental to health, including: (a) recognizing and adapting to various situational demands, (b) shifting mindsets or perspective when personal or social functioning are compromised, (c) balancing competing desires, needs, and life domains, and (d) being aware of, open, and committed to behaviors that are congruent with deeply held values. These four aspects of psychological flexibility are well positioned to explain successful behavioral maintenance toward healthy living in a real-life context (Kwasnicka et al., 2016).

In principle, psychological flexibility can facilitate lasting change in three ways: (a) by increasing commitment to, and improved maintenance of, value-driven behaviors, (b) by strengthening a willing, open, and accepting method of experiencing psychological events thus reducing psychological barriers to behavior change, and (c) by improved awareness of one’s internal and external environment through mindfulness processes that allow behavioral choices to be better fitted to the contextual situation (Butryn et al. , 2011). Functionally speaking, these processes are assessed empirically, in part, by examining whether psychological flexibility serves as the change mechanism for maintenance of adaptive and healthy behaviors (Ciarrochi et al., 2010).

, 2011). Functionally speaking, these processes are assessed empirically, in part, by examining whether psychological flexibility serves as the change mechanism for maintenance of adaptive and healthy behaviors (Ciarrochi et al., 2010).

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is a behavior change method based on RFT and is explicitly oriented toward the development of greater psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., 1999). Although much of the early ACT work targeted mental health, from the beginning there was also a focus on health behavior change (of the first three studies done on ACT in the 1980s one was on diet, and another on dealing with tolerance of physical pain) and that interest has only grown in recent years (e.g., Butryn et al., 2011; Manlick et al., 2013; Bricker et al., 2014, 2017; Moffitt and Mohr, 2015). ACT offers an alternative to traditional attempts to control unwanted psychological experiences. Rather than trying to control the content of thinking and emotions, ACT aims to help individuals change their relationship to these events (Hayes, 2004). In ACT, the goals of the health behavior change interventions are not explicit replacement of previous unhealthy psychological events with new and healthy events, but the concurrent cultivation of acceptance toward of the occurrence of unhealthy psychological events, defusion from strict adherence to those events (i.e., observe the events for what they are as just thoughts of our mind, rather than becoming entangled and fused with them), and the committed action of behaviors that support living in ways that serve predetermined healthy values. In this way, habits for the new healthy behaviors may be established with greater resiliency to psychological barriers.

In ACT, the goals of the health behavior change interventions are not explicit replacement of previous unhealthy psychological events with new and healthy events, but the concurrent cultivation of acceptance toward of the occurrence of unhealthy psychological events, defusion from strict adherence to those events (i.e., observe the events for what they are as just thoughts of our mind, rather than becoming entangled and fused with them), and the committed action of behaviors that support living in ways that serve predetermined healthy values. In this way, habits for the new healthy behaviors may be established with greater resiliency to psychological barriers.

Preliminary evidence of ACT on direct and initial behavior change as well as promotion of behavioral maintenance has been established. ACT has been investigated in several health related domains, with positive long-term results. For example, the effectiveness of a randomized brief physical-activity-focused ACT-based intervention produced significant increases in individuals’ levels of physical activity. The skills taught in this intervention were mindfulness, values clarification, and willingness to experience distress via face-to-face intervention (Butryn et al., 2011) or via DVD (Moffitt and Mohr, 2015). In smoking cessation treatment, the effectiveness of ACT as compared to other interventions (e.g., nicotine replacement treatment, functional analytic psychotherapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy) has been demonstrated in a series of RCTs (e.g., Gifford et al., 2004, 2011; Hernández-López et al., 2009; Bricker et al., 2014, 2017). ACT has been recommended as an acceptance-based self-regulation framework for weight management (Lillis and Kendra, 2014), with awareness of decision-making thoughts and commitment to chosen values viewed as two key components (Forman and Butryn, 2015). For example, a 1-day mindfulness and acceptance-based workshop targeting obesity-related stigma and psychological distress is effective on weight loss and weight-specific acceptance coping; the intervention effects on weight loss was also found mediated by psychological flexibility (Lillis et al.

The skills taught in this intervention were mindfulness, values clarification, and willingness to experience distress via face-to-face intervention (Butryn et al., 2011) or via DVD (Moffitt and Mohr, 2015). In smoking cessation treatment, the effectiveness of ACT as compared to other interventions (e.g., nicotine replacement treatment, functional analytic psychotherapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy) has been demonstrated in a series of RCTs (e.g., Gifford et al., 2004, 2011; Hernández-López et al., 2009; Bricker et al., 2014, 2017). ACT has been recommended as an acceptance-based self-regulation framework for weight management (Lillis and Kendra, 2014), with awareness of decision-making thoughts and commitment to chosen values viewed as two key components (Forman and Butryn, 2015). For example, a 1-day mindfulness and acceptance-based workshop targeting obesity-related stigma and psychological distress is effective on weight loss and weight-specific acceptance coping; the intervention effects on weight loss was also found mediated by psychological flexibility (Lillis et al. , 2009).

, 2009).

Relational Frame Theory and Health Behavior Change

As the underlying foundation of the ACT, RFT is a contemporary behavioral account of language and human cognition. RFT claims that language is not based on learned associations or direct contingencies of a typical variety but is rather based on learned relational responses – patterns of responding to one event in terms of another (Hayes et al., 2001). Taking in to the context of health behavior change, RFT provides advantages in the degree of precision made possible when analyzing verbal contributions to complex human behavior. When applied to the topic of health related behaviors, it provides a preliminary behavioral account for how specific verbal rules come to exert control over responding (Barnes and Keenan, 1993; Carpentier et al., 2002). For example, the sound of the word “cigarette” is placed in a “frame of coordination” or “sameness” with a thin cylinder of finely cut tobacco rolled in paper. From an RFT perspective, this relational response is not dependent on the sound of the name because it is under arbitrary contextual control, not the form of the related events or even direct contact with them (Hayes, 1994; Barnes-Holmes and Barnes-Holmes, 2000; Hayes et al. , 2001). The word “is” in the sentence “this is a cigarette” regulates the relational response of sameness between the name and object. These mutual relations then combine into networks of relations and the effects of related events are transformed. If you were told that a particular brand of cigarettes is laced with poison, you might be afraid to touch a cigarette of that brand even though you had no direct experience of bad things happening. From an RFT point of view, health behavioral change maintenance depends on not only one triggering factor like the intention of doing the behaviors but strengthening or weakening existing relational responses and learning new relational responses in the context of the target behavior(s).

, 2001). The word “is” in the sentence “this is a cigarette” regulates the relational response of sameness between the name and object. These mutual relations then combine into networks of relations and the effects of related events are transformed. If you were told that a particular brand of cigarettes is laced with poison, you might be afraid to touch a cigarette of that brand even though you had no direct experience of bad things happening. From an RFT point of view, health behavioral change maintenance depends on not only one triggering factor like the intention of doing the behaviors but strengthening or weakening existing relational responses and learning new relational responses in the context of the target behavior(s).

Relational Frame Theory also provides grounds for considering contextual forms of ACT-based interventions versus content-based forms. If cognitive relations are learned, it is not fully possible to remove the historically established psychological relations between environmental cues and past unhealthy behaviors because there is no psychological process called “unlearning” (Hayes, 2004). Furthermore, if relating can be based on arbitrary cues it is hard to imagine how to deliberately alter ones cognitive networks without unexpected effects. This makes lasting change difficult. For example, telling yourself not to think of eating unhealthy food (say “don’t think about potato chips”) may paradoxically increase the likelihood that you are thinking about unhealthy food, since the rule contains the very verbal stimuli (the words “potato chips”) that are related to the unhealthy food, and every time you check to see if you are following the rule, you are very close to violating it (Wegner, 1994). This paradox of emotional or cognitive control may help explain why attempting to control unhealthy behaviors may at times cause the inverse effect and why even individuals who choose to change their eating behavior, from an unhealthy to a healthy diet, may struggle to maintain this new lifestyle choice despite reporting high motivation.

Furthermore, if relating can be based on arbitrary cues it is hard to imagine how to deliberately alter ones cognitive networks without unexpected effects. This makes lasting change difficult. For example, telling yourself not to think of eating unhealthy food (say “don’t think about potato chips”) may paradoxically increase the likelihood that you are thinking about unhealthy food, since the rule contains the very verbal stimuli (the words “potato chips”) that are related to the unhealthy food, and every time you check to see if you are following the rule, you are very close to violating it (Wegner, 1994). This paradox of emotional or cognitive control may help explain why attempting to control unhealthy behaviors may at times cause the inverse effect and why even individuals who choose to change their eating behavior, from an unhealthy to a healthy diet, may struggle to maintain this new lifestyle choice despite reporting high motivation.

To overcome the problem of this paradoxical effect, RFT provides a theoretical explanation for the importance of using ACT-based interventions to develop psychological flexibility toward the verbal/cognitive networks that establish relations among stimuli, rules, and behaviors. People may need to learn how to strengthen or weaken the behavioral impact of rules rather than attempt to relate their presence or absence to success or failure. This breath of application is one reason ACT has been used to promote individuals’ psychological flexibility across a wide domain of health-related behaviors (e.g., Lillis et al., 2009; Butryn et al., 2011). For example, a diabetic person who can strengthen a values-linked rule such as “if I carry too much excessive weight I may not see my children grow up” may successfully reduce excessive eating throughout the day. Conversely, learning to weaken the impact of shame-linked rules like “I am a fat failure” through mindfulness and defusion methods described below fosters that same behavioral end.

People may need to learn how to strengthen or weaken the behavioral impact of rules rather than attempt to relate their presence or absence to success or failure. This breath of application is one reason ACT has been used to promote individuals’ psychological flexibility across a wide domain of health-related behaviors (e.g., Lillis et al., 2009; Butryn et al., 2011). For example, a diabetic person who can strengthen a values-linked rule such as “if I carry too much excessive weight I may not see my children grow up” may successfully reduce excessive eating throughout the day. Conversely, learning to weaken the impact of shame-linked rules like “I am a fat failure” through mindfulness and defusion methods described below fosters that same behavioral end.

Very recently, implicit methods of cognitive assessment, derived from RFT, have been used to predict the motivational impact of verbal descriptions on the relation between athletic activity and its outcomes, altering exercise levels and persistence through motivational operations (Jackson et al. , 2016). Accordingly, the effects of the sensory, or perceptual, consequences of eating can be altered based on how an individual frames those consequences verbally, and by how the person relates to their own verbal processes. A similar effect has been empirically shown in the physical activity of people who avoid pain (e.g., Vowles et al., 2007). Therefore, more research should be conducted in the fields of health, behavior, and clinical psychology to further clarify the processes underlying RFT principles, ACT processes, and health behavior change.

, 2016). Accordingly, the effects of the sensory, or perceptual, consequences of eating can be altered based on how an individual frames those consequences verbally, and by how the person relates to their own verbal processes. A similar effect has been empirically shown in the physical activity of people who avoid pain (e.g., Vowles et al., 2007). Therefore, more research should be conducted in the fields of health, behavior, and clinical psychology to further clarify the processes underlying RFT principles, ACT processes, and health behavior change.

Act for Health Behavior Change: The Psychological Flexibility Model

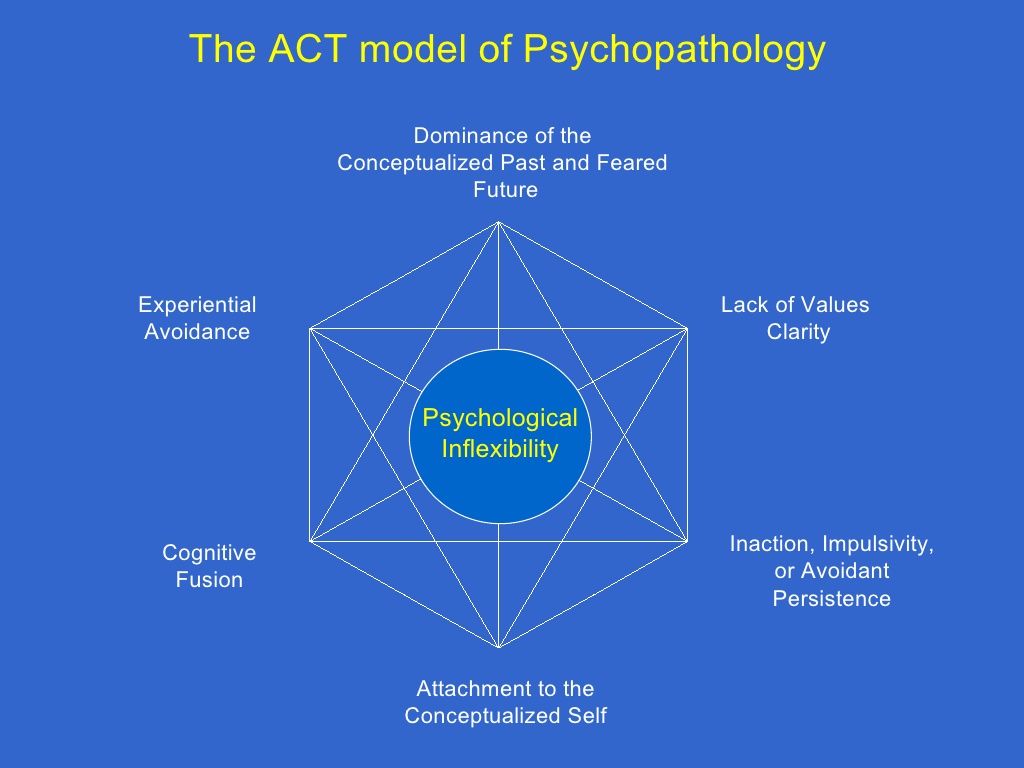

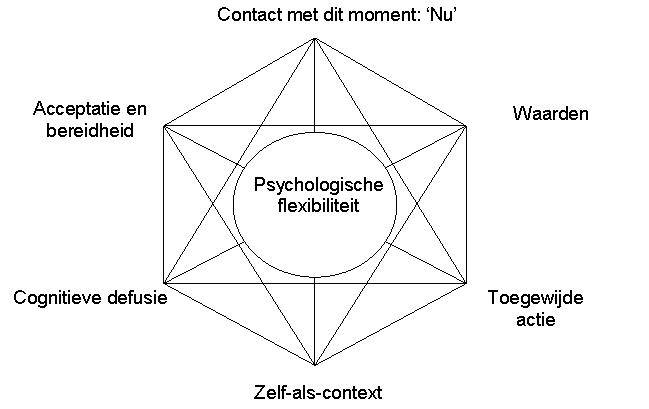

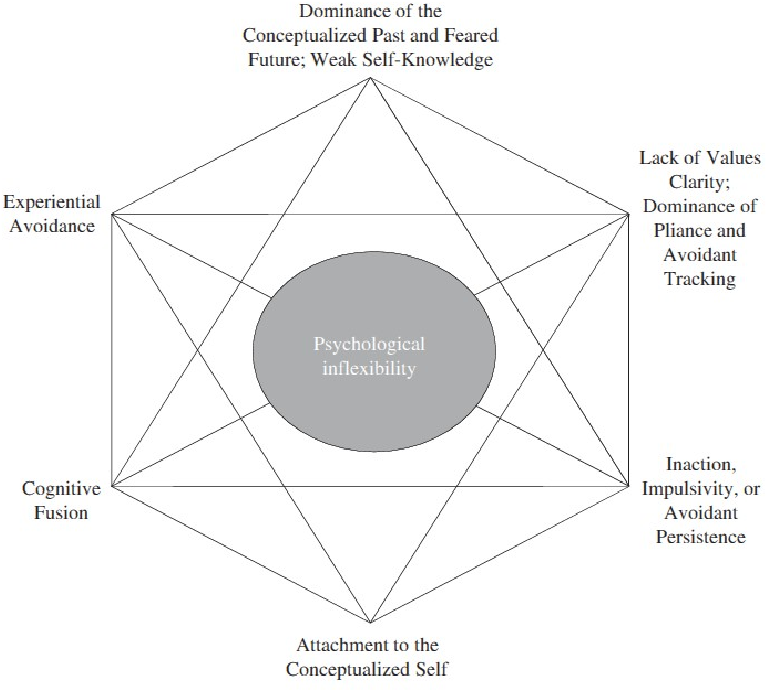

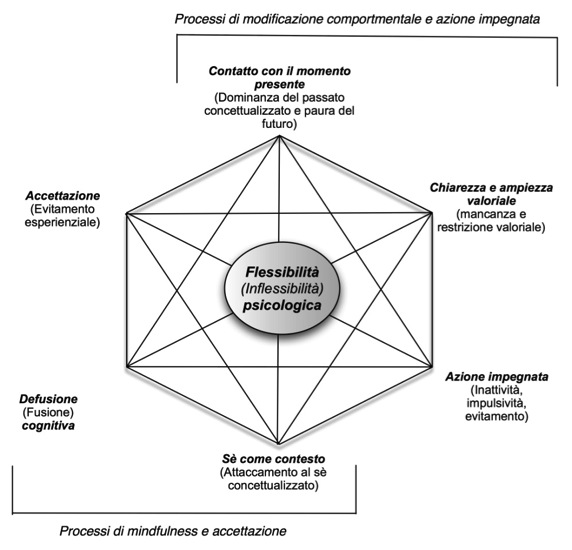

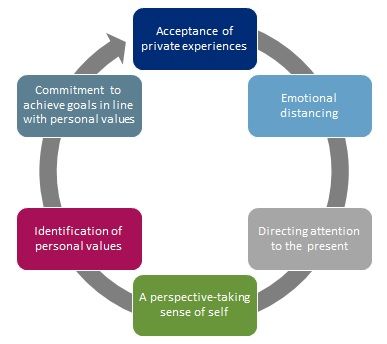

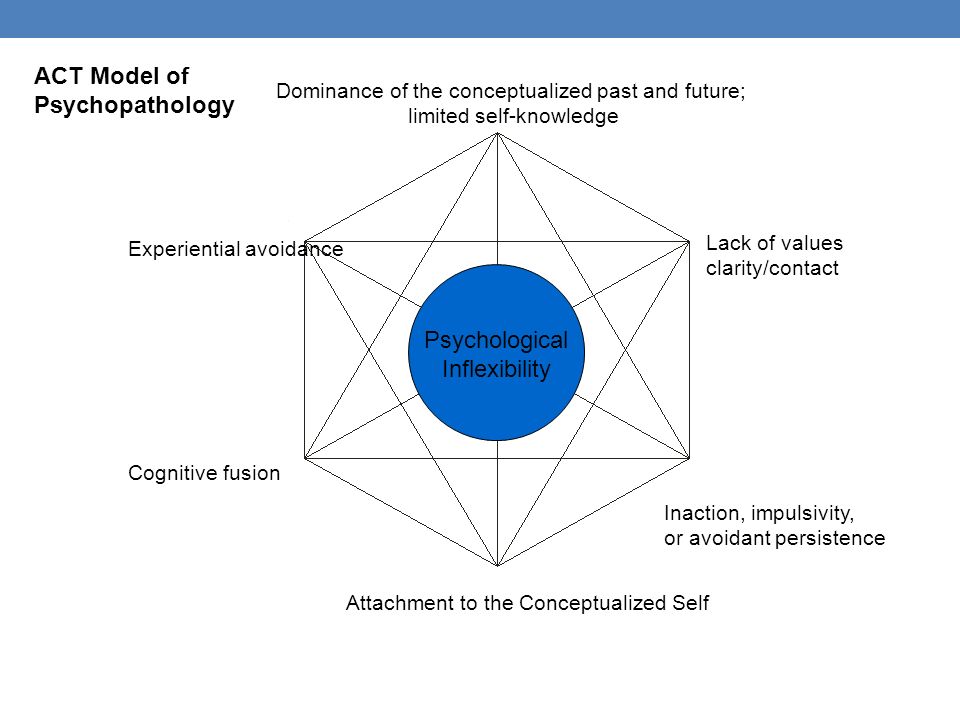

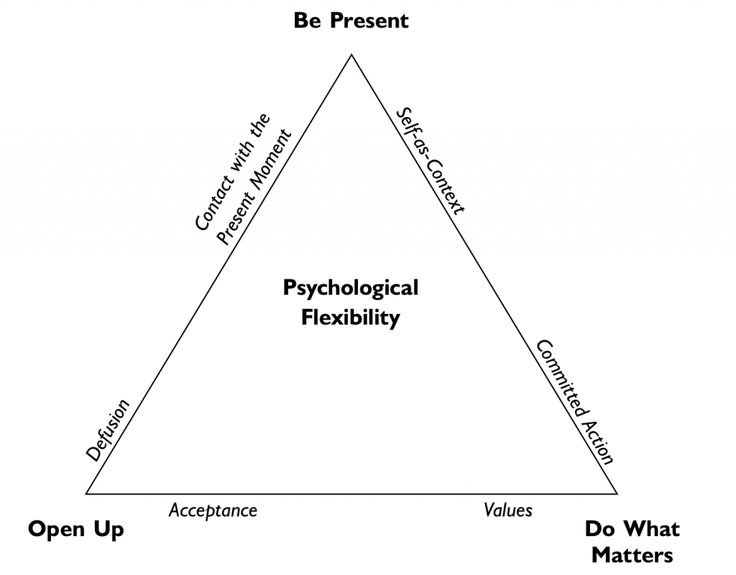

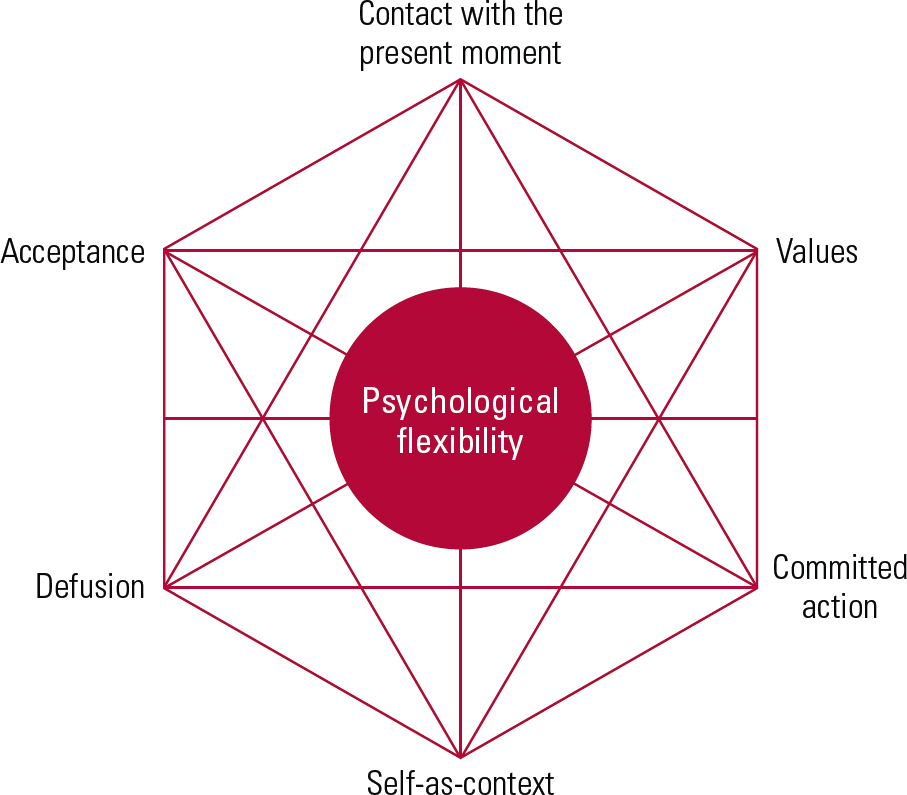

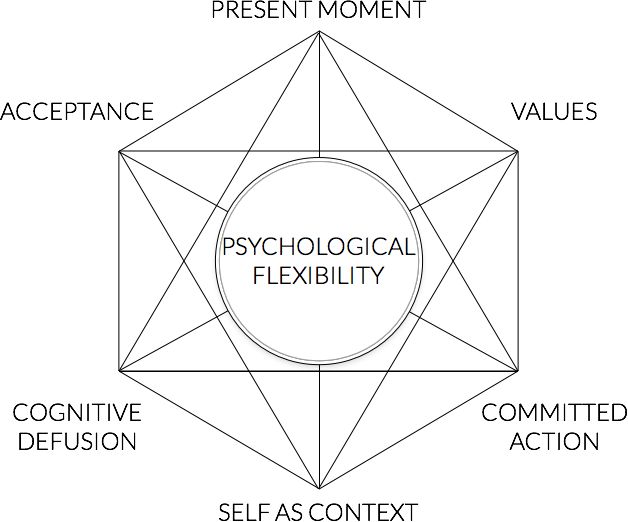

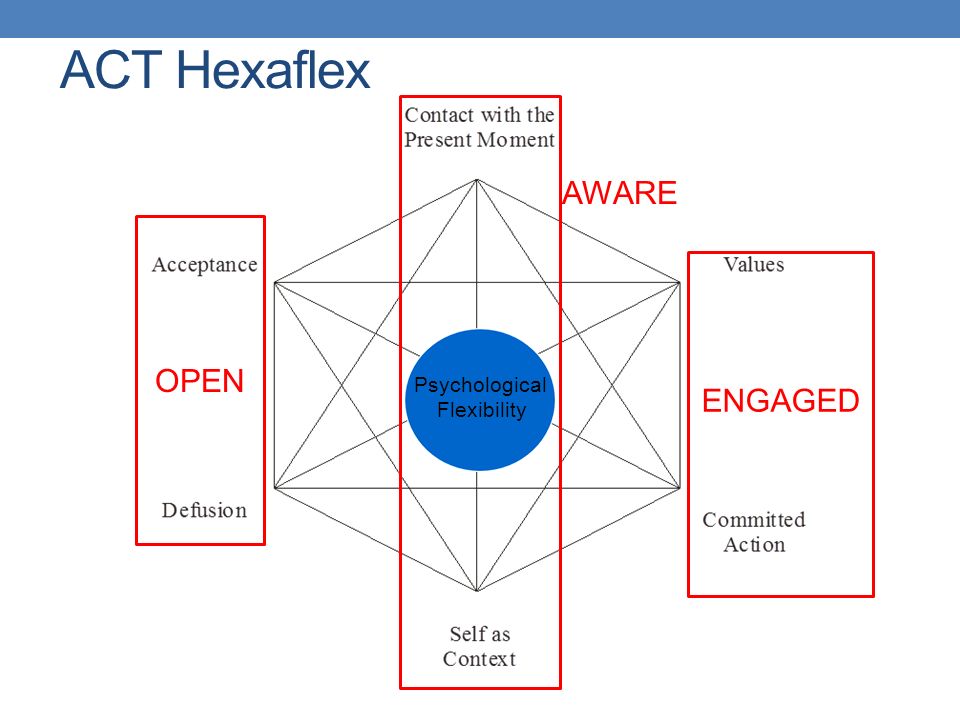

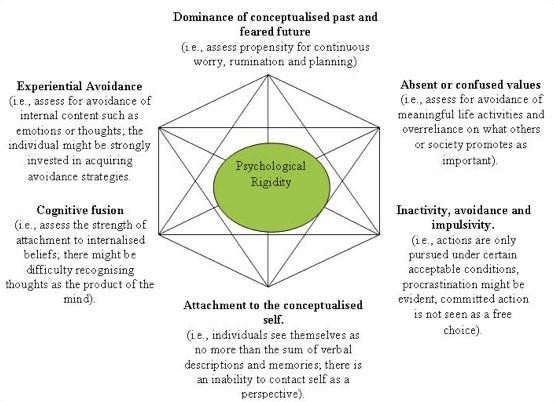

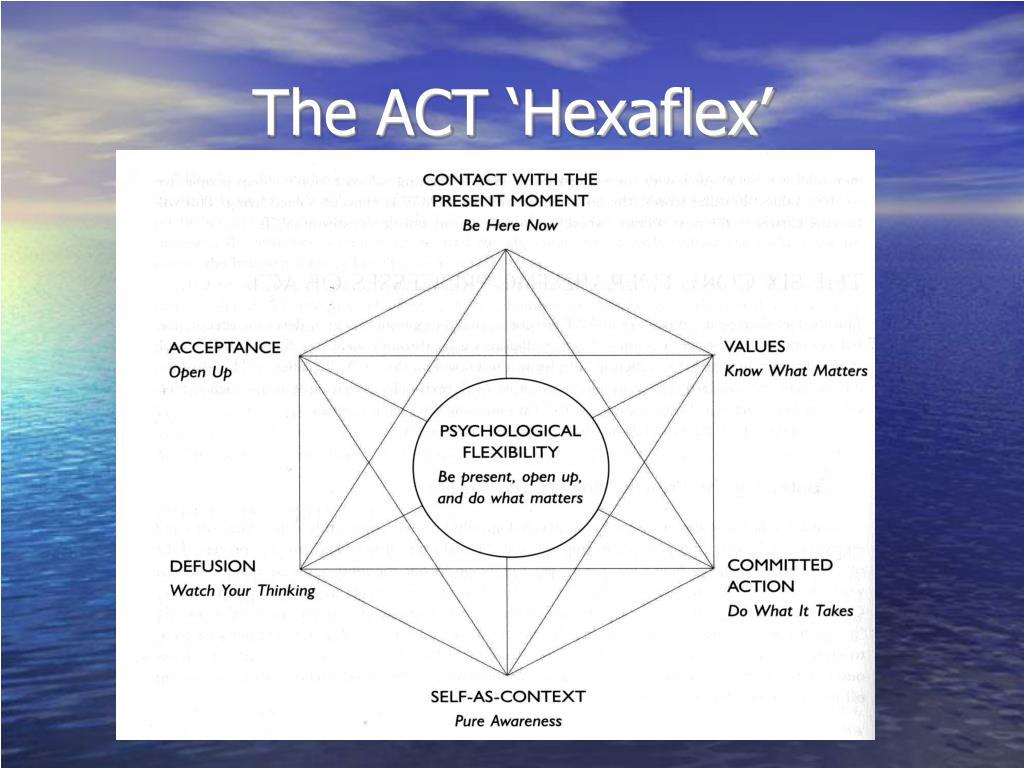

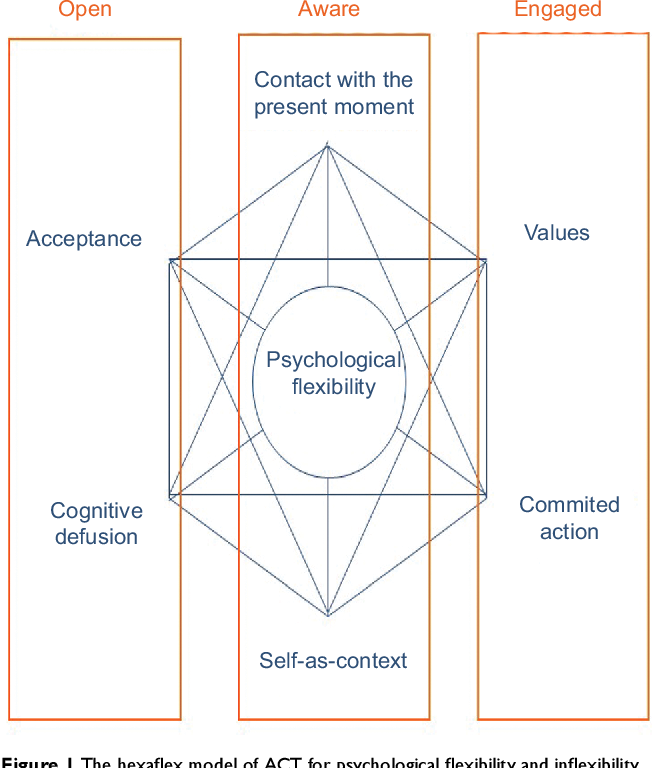

Psychological flexibility model is a behavior change model based on RFT and its applied extensions that is used for understanding how rule-following behavior can affect behavior (Hayes et al., 1999; Gross and Fox, 2009) based on how people interact with their own language processes (Bond et al., 2006). According to the psychological flexibility model, which underpins ACT, psychological flexibility consists of six primary components: defusion, acceptance, self as context, contact with the present moment, values, and committed action. Psychological inflexibility is the opposite: fusion, experiential avoidance, the conceptualized self, rigid attention to the past or future, unclear values, and inaction, impulsivity, or persistence avoidance.

Psychological inflexibility is the opposite: fusion, experiential avoidance, the conceptualized self, rigid attention to the past or future, unclear values, and inaction, impulsivity, or persistence avoidance.

Psychological flexibility promotes behavior that aligns with the individual’s values rather than allowing thoughts about events to dominate regardless of their usefulness. To date, ACT is the most researched intervention model targeting psychological flexibility. Psychological flexibility is described as the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behavior such that one continues to behave in a way that is consistent with their pre-established and identified values (Hayes et al., 1996). The following will briefly describe these six flexibility processes and relate them to health behavior.

Defusion

A defining concept of psychological flexibility is defusion. In situations where fusion occurs, individuals respond to the content of their language as if those descriptions are literally occurring (Hayes et al. , 1999). For example, an individual attempting to quit smoking may experiencing physiological distress and may engage in verbal behavior that describes the context as “this is too difficult, I can’t quit.” When this verbal behavior is seen as a literal description of ability, the individual may return to smoking as a function of the description of the event and not as function of what they are physically capable of achieving. Defusion is the use of function-altering cues and strategies to reduce the transformation of stimulus functions in such cases, thus changing the impact of verbal events on other behavioral processes. Said in a more commonsense way, defusion it looking at thoughts with an attitude of dispassionate curiosity. Defusion methods, such as repeating the name of a feared object until it loses meaning, may reduce the impact of such thoughts (Blackledge, 2015).

, 1999). For example, an individual attempting to quit smoking may experiencing physiological distress and may engage in verbal behavior that describes the context as “this is too difficult, I can’t quit.” When this verbal behavior is seen as a literal description of ability, the individual may return to smoking as a function of the description of the event and not as function of what they are physically capable of achieving. Defusion is the use of function-altering cues and strategies to reduce the transformation of stimulus functions in such cases, thus changing the impact of verbal events on other behavioral processes. Said in a more commonsense way, defusion it looking at thoughts with an attitude of dispassionate curiosity. Defusion methods, such as repeating the name of a feared object until it loses meaning, may reduce the impact of such thoughts (Blackledge, 2015).

Acceptance

Acceptance occurs when an individual willingly experiences automatic, and sometimes unwanted, emotions or sensations without attempting to control the form, frequency, or situational sensitivity of these experiences (Bond et al. , 2006). The psychological flexibility model contends it is not the content of emotions that become problematic to a quality life but rather problems arise when individuals interact with these events in an avoidant way (Bond et al., 2006). An example of behavior that is not indicative of acceptance is when an obese individual, who experiences anxiety around exercise and the gym, avoids these situations where anxiety occurs. Conversely, an individual experiencing anxiety around exercise and engaging in acceptance responses would instead acknowledge the anxiety with a sense of dispassionate curiosity and allow themselves to experience these emotions and situations where they occur. Scores of studies have shown that such strategies increase task persistence (Levin et al., 2012).

, 2006). The psychological flexibility model contends it is not the content of emotions that become problematic to a quality life but rather problems arise when individuals interact with these events in an avoidant way (Bond et al., 2006). An example of behavior that is not indicative of acceptance is when an obese individual, who experiences anxiety around exercise and the gym, avoids these situations where anxiety occurs. Conversely, an individual experiencing anxiety around exercise and engaging in acceptance responses would instead acknowledge the anxiety with a sense of dispassionate curiosity and allow themselves to experience these emotions and situations where they occur. Scores of studies have shown that such strategies increase task persistence (Levin et al., 2012).

Flexible Attention to the Present Moment

Human beings are uniquely adept at problem solving and planning. While these behaviors are often beneficial, they can sometimes be maladaptive, especially when language patterns become fused with temporal and evaluative statements. Problem solving always requires examination of the past and future (e.g., “How did I get here?” “Where am I going?”), but can overwhelm flexible attention to the present environment, both external and internal. Working in coordination with acceptance and defusion, contact with the present moment helps individuals respond while in touch with current environmental demands rather than merely the “what if” contexts reflective of rumination over past experiences and anxious anticipation of future ones (Bond et al., 2006). When individuals attend flexibly, fluidly, and voluntarily to the immediately relevant internal and external environment, performance demands can be better adjusted to what is presently occurring.

Problem solving always requires examination of the past and future (e.g., “How did I get here?” “Where am I going?”), but can overwhelm flexible attention to the present environment, both external and internal. Working in coordination with acceptance and defusion, contact with the present moment helps individuals respond while in touch with current environmental demands rather than merely the “what if” contexts reflective of rumination over past experiences and anxious anticipation of future ones (Bond et al., 2006). When individuals attend flexibly, fluidly, and voluntarily to the immediately relevant internal and external environment, performance demands can be better adjusted to what is presently occurring.

Self-as-Context

The concept of self-as-context refers to the perspective skills needed for an individual to report on their own behavior from a consistent perspective or point of view. RFT research shows three key deictic relational frames are involved: I/YOU, HERE/THERE, and NOW/THEN (Hayes et al. , 2006). When “I/HERE/NOW” comes together, it yields a sense of self as an observer. An individual, who can see and recognize their own verbal descriptions of themselves as distinct from the “I/HERE/NOW” perspective, may feel less threatened by negative statements about the self. For example, someone engaging in addictive behavior stating “I’m a no good drunk” might more readily recognize that statement merely as a thought that does not summarize themselves as a totality. By changing the statement to “I am having the thought that I am a no good drunk” they may thus reorient toward better quality of life behaviors.

, 2006). When “I/HERE/NOW” comes together, it yields a sense of self as an observer. An individual, who can see and recognize their own verbal descriptions of themselves as distinct from the “I/HERE/NOW” perspective, may feel less threatened by negative statements about the self. For example, someone engaging in addictive behavior stating “I’m a no good drunk” might more readily recognize that statement merely as a thought that does not summarize themselves as a totality. By changing the statement to “I am having the thought that I am a no good drunk” they may thus reorient toward better quality of life behaviors.

This first four flexibility processes provide a working definition of mindfulness in a psychological flexibility model. The processes of adopting chosen values and commitment to the action of health behaviors relates to both initiation and maintenance of health behavior change.

Values

Values are defined as chosen immediate qualities of ongoing patterns of action that are verbally established as reinforcers (Hayes et al. , 1999). For example, an individual may value “investing in family life.” Such a statement is differentiated from a goal in that a value is not a tangible outcome such as “Friday family movie night” but is instead a quality of action. Values are known to increase task persistence across multiple health related behavior (e.g., Chase et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2016). An individual who values investing in family life will engage in multiple behaviors that contribute to that stated value, i.e., helping children with homework, attending soccer and dance lesions, date nights, open communication, dressing up for date nights, exercising to model and pattern healthy life behaviors and so on. Values based living then, is living in such a way that values provide direction like a compass.

, 1999). For example, an individual may value “investing in family life.” Such a statement is differentiated from a goal in that a value is not a tangible outcome such as “Friday family movie night” but is instead a quality of action. Values are known to increase task persistence across multiple health related behavior (e.g., Chase et al., 2013; Jackson et al., 2016). An individual who values investing in family life will engage in multiple behaviors that contribute to that stated value, i.e., helping children with homework, attending soccer and dance lesions, date nights, open communication, dressing up for date nights, exercising to model and pattern healthy life behaviors and so on. Values based living then, is living in such a way that values provide direction like a compass.

Committed Action

In clinical settings, committed action looks much like traditional behavioral approaches (Bond et al., 2006). As part of psychological flexibility, committed action takes the role of expanding an individual’s valued responses into larger and larger patterns of activity. Larger patterns can be built by obtainable intermediary goals that comport with pre-established values. For example, an individual who experiences exercise anxiety and has historically pulled out or stopped exercising, may now set the goal of walking for an hour, three times a week in alignment with their value of “living a healthy lifestyle through exercise.”

Larger patterns can be built by obtainable intermediary goals that comport with pre-established values. For example, an individual who experiences exercise anxiety and has historically pulled out or stopped exercising, may now set the goal of walking for an hour, three times a week in alignment with their value of “living a healthy lifestyle through exercise.”

Conclusion

Although ACT was originally developed in the field of clinical psychology (Hayes, 2004), it has shown promise in facilitating individuals’ health behavior change with greater efficacy and fulfillment in individuals’ real-life contexts. The authors call for the further application of ACT and its underlying psychological flexibility model into the promotion of health behavior change. In particular, the health behavior change of individuals with clinical conditions such as chronic pain in order to increase beneficial physical activity (e.g., VanBuskirk et al., 2014). Finally, we emphasize that empirical evidence, gathered through robust research designs, on the efficacy and resilience/durability of ACT interventions on health behavioral change is urgently needed (e. g., randomized controlled trials).

g., randomized controlled trials).

Author Contributions

C-QZ, EL, PS, P-KC, MH, and SH contributed to the conception and writing of the content for the review.

Funding

The open access publication fee was supported by RAE Professional Development Grant (Ref. 0032017) awarded to P-KC by the Faculty of Social Sciences, Hong Kong Baptist University.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Barnes, D., and Keenan, M. (1993). A transfer of functions through derived arbitrary and non-arbitrary stimulus relations. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 59, 61–81. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.59-61

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Barnes-Holmes, D., and Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2000). Explaining complex behavior. two perspectives on the concept of generalized operant classes. Psychol. Rec. 50, 251–265. doi: 10.1007/BF03395355

Rec. 50, 251–265. doi: 10.1007/BF03395355

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Google Scholar

Biglan, A., Hayes, S. C., and Pistorello, J. (2008). Acceptance and commitment: implications for prevention science. Prev. Sci. 9, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0099-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blackledge, J. T. (2015). Cognitive Defusion in Practice: A Clinician’s Guide to Assessing, Observing, and Supporting Change in Your Client. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Google Scholar

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., and Barnes-Homes, D. (2006). Psychological flexibility, ACT and organizational behavior. J. Organ. Behav. Manage. 26, 25–54. doi: 10.1300/J075v26n01_02

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bricker, J. B., Copeland, W., Mull, K. E., Zeng, E. Y., Watson, N. L., Akioka, K. J., et al. (2017). Single-arm trial of the second version of an acceptance & commitment therapy smartphone application for smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 170, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.029

L., Akioka, K. J., et al. (2017). Single-arm trial of the second version of an acceptance & commitment therapy smartphone application for smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 170, 37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.029

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bricker, J. B., Mull, K. E., Kientz, J. A., Vilardaga, R., Mercer, L. D., Akioka, K. J., et al. (2014). Randomized, controlled pilot trial of a smartphone app for smoking cessation using acceptance and commitment therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 143, 87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.07.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Butryn, M. L., Forman, E., Hoffman, K., Shaw, J., and Juarascio, A. (2011). A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for promotion of physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 8, 516–522. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.4.516

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Carpentier, F., Smeets, P. M., and Barnes-Holmes, D. (2002). Establishing transfer of compound control in children: a stimulus control analysis. Psychol. Rec. 52, 139–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03395420

(2002). Establishing transfer of compound control in children: a stimulus control analysis. Psychol. Rec. 52, 139–158. doi: 10.1007/BF03395420

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chase, J. A., Houmanfar, R., Hayes, S. C., Ward, T. A., Vilardaga, J. P., and Follette, V. M. (2013). Values are not just goals: online ACT-based values training adds to goal-setting in improving undergraduate college student performance. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 2, 79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.08.002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ciarrochi, J., Bilich, L., and Godsel, C. (2010). “Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in acceptance and commitment therapy,” in Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance: Illuminating the Processes of Change, ed. R. Baer (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc).

Google Scholar

Ellis, A. (1962). Reasons and Emotion in Psychotherapy. Secaucus, NJ: Lyle Stuart.

Google Scholar

Forman, E. M., and Butryn, M. L. (2015). A new look at the science of weight control: how acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite 84, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004

M., and Butryn, M. L. (2015). A new look at the science of weight control: how acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite 84, 171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gifford, E. V., Kohlenberg, B. S., Hayes, S. C., Antonuccio, D. O., Piasecki, M. M., Rasmussen-Hall, M. L., et al. (2004). Acceptance-based treatment for smoking cessation. Behav. Ther. 35, 689–705. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80015-7

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gifford, E. V., Kohlenberg, B. S., Hayes, S. C., Pierson, H. M., Piasecki, M. P., Antonuccio, D. O., et al. (2011). Does acceptance and relationship focused behavior therapy contribute to bupropion outcomes? A randomized controlled trial of functional analytic psychotherapy and acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation. Behav. Ther. 42, 700–715. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.002

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gross, A. , and Fox, E. J. (2009). Relational frame theory: an overview of the controversy. Anal. Verbal Behav. 25, 87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF03393073

, and Fox, E. J. (2009). Relational frame theory: an overview of the controversy. Anal. Verbal Behav. 25, 87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF03393073

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hayes S. C. (1994). “Relational frame theory: a functional approach to verbal events,” in Behavior Analysis of Language and Cognition, eds S. C. Hayes and L. J. Hayes (Reno, NV: Context Press), 9–30

Google Scholar

Hayes, S. C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 35, 639–665. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hayes, S. C., and Barnes-Holmes, D., and Roche, B. (2001). Relational Frame Theory. A post Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Google Scholar

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., and Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

Behav. Res. Ther. 44, 1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., and Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Experiential Approach to Behavior Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Hayes, S. C., Wilson, K. G., Gifford, E. V., Follette, V. M., and Strosahl, K. (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: a functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 64, 1152–1168. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.6.1152

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hernández-López, M., Luciano, M. C., Bricker, J. B., Roales-Nieto, J. G., and Montesinos, F. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy for smoking cessation: a preliminary study of its effectiveness in comparison with cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 23, 723–730. doi: 10.1037/a0017632

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jackson, M. L., Williams, W. L., Hayes, S. C., Humphreys, T., Gauthier, B., and Westwood, R. (2016). Whatever gets your heart pumping: the impact of implicitly selected reinforcer-focused statements on exercise intensity. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 5, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.11.002

L., Williams, W. L., Hayes, S. C., Humphreys, T., Gauthier, B., and Westwood, R. (2016). Whatever gets your heart pumping: the impact of implicitly selected reinforcer-focused statements on exercise intensity. J. Contextual Behav. Sci. 5, 48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.11.002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kashdan, T. B., and Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30, 865–878. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar