How does teaching make a difference

How Teaching Makes a Difference in Students’ Lives – Association for Psychological Science – APS

Professor Excellent and Professor Good both work in the same psychology department at a medium-sized state university. In fact, they were hired the same year and are now in their third year as assistant professors. Dr. Excellent and Dr. Good teach similarly sized sections of introductory psychology and upper-division courses in their specialty areas. Their trajectories for tenure and promotion look promising — they both have productive labs generating top-notch articles and conference presentations, and their services to the department, college, and the discipline are exemplary.

Upon closer inspection though, there is one important difference between Dr Excellent and Dr. Good: Despite similarities in their course grade distributions, Dr. Excellent’s teaching is more impactful on students than Dr. Good’s teaching. Dr. Good is not an incompetent teacher — quite the contrary. Her teaching evaluations are above average, and students comment that they have learned much from her classes and enjoy her teaching.

Dr. Excellent’s students, too, rate her above average — much above average, and rave about what they have learned in her classes and how much they have enjoyed them. The written portions of Dr. Excellent’s teaching evaluations are telling. Many students note that Dr. Excellent has inspired them to study harder than ever before, helped them to become interested — really interested — in learning for the first time in their lives and instilled confidence in them as learners. In just the past year, three students have dropped by Dr. Excellent’s office to tell her that, because of their experience in her introductory psychology course, they are changing their majors to psychology. One of these students said to her, “Dr. Excellent, I want you to know how much you have changed my life. I will never be the same again. I now have a clear idea of what I want to do, and the confidence that I can do it.”

On the one hand, we all know teachers like Dr. Good. Psychology departments everywhere are filled with plenty of competent teachers like her. They represent our discipline honorably and teach its basic theories, principles, and applications well. On the other hand, we might know only one or two teachers like Dr. Excellent. Indeed, not every psychology department has a Dr. Excellent — truly exceptional teachers are rare. Like Dr. Good, these extraordinary teachers convey to students the nuts and bolts of the discipline, but they also do something much more: They somehow make a difference in students’ lives: They inspire.

They represent our discipline honorably and teach its basic theories, principles, and applications well. On the other hand, we might know only one or two teachers like Dr. Excellent. Indeed, not every psychology department has a Dr. Excellent — truly exceptional teachers are rare. Like Dr. Good, these extraordinary teachers convey to students the nuts and bolts of the discipline, but they also do something much more: They somehow make a difference in students’ lives: They inspire.

Making a Difference: A Teacher’s

Raison d’Être?

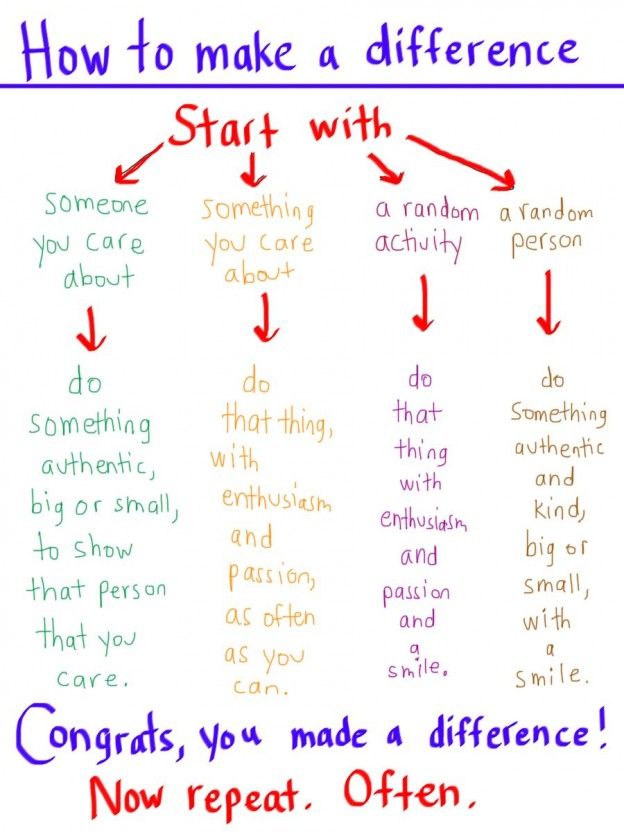

Should we seek to improve our teaching so that it becomes more akin to Dr. Excellent’s teaching rather than Dr. Good’s? Should we talk to each other in departmental hallways and conferences about how to improve our teaching until it at least borders on excellence? Should we prepare the next generation of the psychology professoriate to make a difference in the lives of our future students? The answer to each of these questions is a resounding yes, according to one of the patriarchs of the teaching of psychology, Charles L. Brewer. In the final sentence of a book chapter in which he reflected over his long and illustrious teaching career, Brewer (2002) commented “I hope the world is a better place because we teachers make a difference to our students; after all, that is what teaching is all about” (p. 507). Brewer is one of the few persons to express this idea in print. In fact, if you look through the well known “how to” books on teaching, such as those by Davis (2009) and Svinicki and McKeachie (2011), you will find little, if anything, about making a difference in students’ lives or how to do it effectively. Weimer (1993) and Fink (2003) noted that pedagogical journals follow suit by emphasizing primarily teaching techniques and how to help students learn the basic facts of one’s discipline rather than inspiring students to learn beyond the course material.

Brewer. In the final sentence of a book chapter in which he reflected over his long and illustrious teaching career, Brewer (2002) commented “I hope the world is a better place because we teachers make a difference to our students; after all, that is what teaching is all about” (p. 507). Brewer is one of the few persons to express this idea in print. In fact, if you look through the well known “how to” books on teaching, such as those by Davis (2009) and Svinicki and McKeachie (2011), you will find little, if anything, about making a difference in students’ lives or how to do it effectively. Weimer (1993) and Fink (2003) noted that pedagogical journals follow suit by emphasizing primarily teaching techniques and how to help students learn the basic facts of one’s discipline rather than inspiring students to learn beyond the course material.

Brewer is clearly onto something. After all, everyone who holds a PhD in psychology or is working toward one can probably attribute part of their desire to become a psychologist to one or two undergraduate teachers who inspired them. Those teachers make a big difference in our lives and in the future of the discipline.

Those teachers make a big difference in our lives and in the future of the discipline.

Although Brewer did not specify what he meant by making a difference in students’ lives or the processes involved, it is likely he envisioned the kind of impact that inspirational teachers like Dr. Excellent have on students rather than the impact of teachers like Dr. Good. There may be more at stake in teaching and learning than students getting good grades. Bill McKeachie, who wrote the bible on college and university teaching, agrees that making a difference in students’ lives is not bounded by the nuts and bolts of our science as he noted when he told us, “I think we make a difference in our students by letting them know that we are committed to helping each of them become better life-long learners. Actually, it’s not just giving them skills and strategies for learning, but, more important, giving them the confidence and motivation for life-long learning” (personal communication).

What Does It Mean to Make a Difference?

Is McKeachie correct? Does the key to making a difference in students’ lives rest on how a teacher helps them undergo some sort of significant personal transformation? Is inspiring a love for learning beyond the facts a defining characteristic of what it means to make a difference? Is it critically important to show students that we care about them, and how well they are learning the subject matter?

Curious about the answers to these questions, we put the matter to 173 upper-division (junior and senior) students across several courses (introductory psychology, applied behavior analysis, learning, research methods, and industrial/organizational psychology). We asked them, “Have you ever had a college or university teacher or teachers whom you felt made a genuine difference in your life in some way?” The good news is that of these students, 136 (79%) indicated that they had at least one college teacher who they felt had made a difference in their lives. The bad news is that, even after at least 3 years of college, a sizeable number of students (37, 21%) had not yet met such a teacher.

We asked them, “Have you ever had a college or university teacher or teachers whom you felt made a genuine difference in your life in some way?” The good news is that of these students, 136 (79%) indicated that they had at least one college teacher who they felt had made a difference in their lives. The bad news is that, even after at least 3 years of college, a sizeable number of students (37, 21%) had not yet met such a teacher.

We followed up by asking the first set of students “What did this teacher(s) do to make a difference?” Our students shared with us a variety ways in which some of their teachers had made a difference in their lives. Tops on their list (for 37 students, 27%) was that their most impactful teachers had taken a personal interest in them and helped them develop personal insights about how the subject matter was relevant to their lives. Almost as many students (29, 21%) indicated that their teacher(s) had provided encouragement in their work, which gave them confidence that they could succeed in the class and in college. Coming in a close third (28 students, 21%) was the teacher’s passion for the subject matter and showing a genuine concern for student learning. Fourth on the list (19 students, 14%) was that these teachers went out of their way, “above and beyond” as some students phrased it, to help students learn the material and succeed in the course. Rounding out the top five (10 students, 7%) was that some of their teachers inspired them to learn outside of the class.

Coming in a close third (28 students, 21%) was the teacher’s passion for the subject matter and showing a genuine concern for student learning. Fourth on the list (19 students, 14%) was that these teachers went out of their way, “above and beyond” as some students phrased it, to help students learn the material and succeed in the course. Rounding out the top five (10 students, 7%) was that some of their teachers inspired them to learn outside of the class.

Based on these student perspectives, McKeachie’s insights appear spot on: Showing students how much we care about them and their learning fuels personal insight and growth, instills personal confidence, and inspires their interest in learning in and out of the classroom. In other words, teachers who make a difference really do facilitate a significant personal transformation in the lives of their students.

How Not to Make a Difference

What about the other students to whom we talked — those who reported that, at least to this point in their college careers, they had no teacher make a difference in their lives? We asked these students to share with us the reasons that they thought they had not run across this kind of teacher yet.

Most of these students (18, 49%) felt that large class sizes made it difficult, if not impossible, to develop the sort of relationship with their teachers that would allow professors to make a difference in their lives. Ten students (27%) said that their teachers gave them the clear impression that they did not care about them as students. Finally, six students (16%) said that they were neither motivated nor wanted to take the time to interact with their professors in ways that would allow their teacher to make a difference in their lives.

Although on the surface these three points appear to be at least slightly divergent, there is an underlying theme that unites them: Teaching and learning in college are personal experiences that occur within a social context. Factors that disrupt the social context make it unlikely, if not impossible, for impactful teaching to occur. Large classes in which teachers permit students to retain a significant degree of anonymity are unlikely to foster the sort of teaching that makes a difference in students’ lives. Similarly, if teachers and students are not willing to explore the social context to further enhance the learning experience, impactful teaching simply won’t happen.

Similarly, if teachers and students are not willing to explore the social context to further enhance the learning experience, impactful teaching simply won’t happen.

Teaching to Make a Difference

As the saying goes, it takes two to tango. To make a difference, teachers must be willing and able to create a conducive, social environment for learning and students have to be open to the experience of learning in this environment. The question is, of course, how to get this dance started in the first place and then how to keep it going.

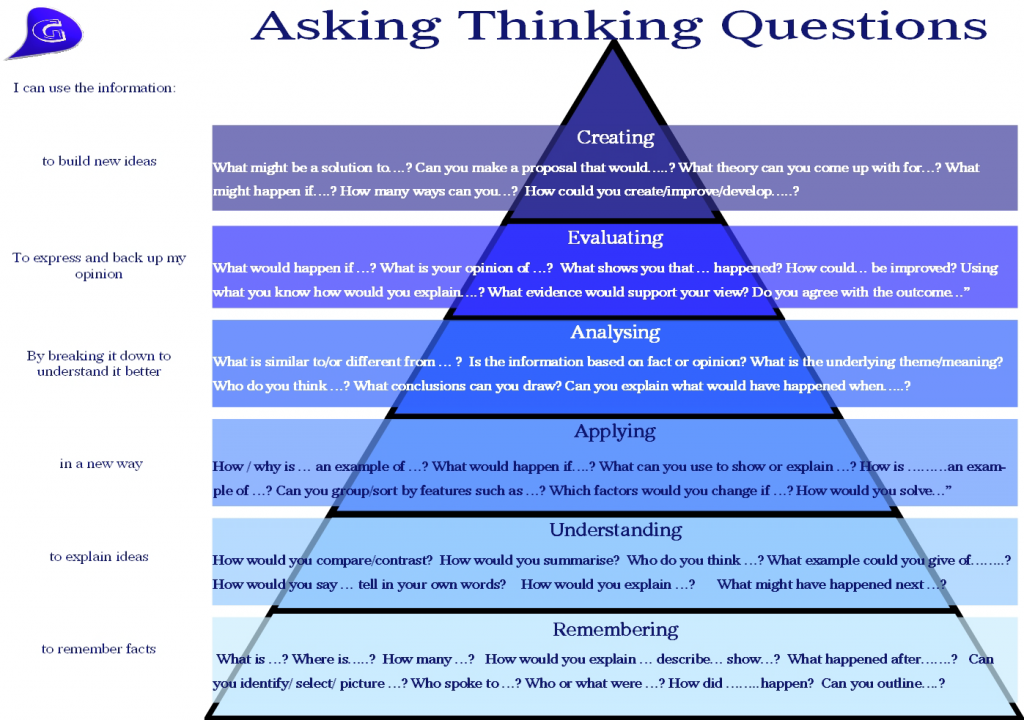

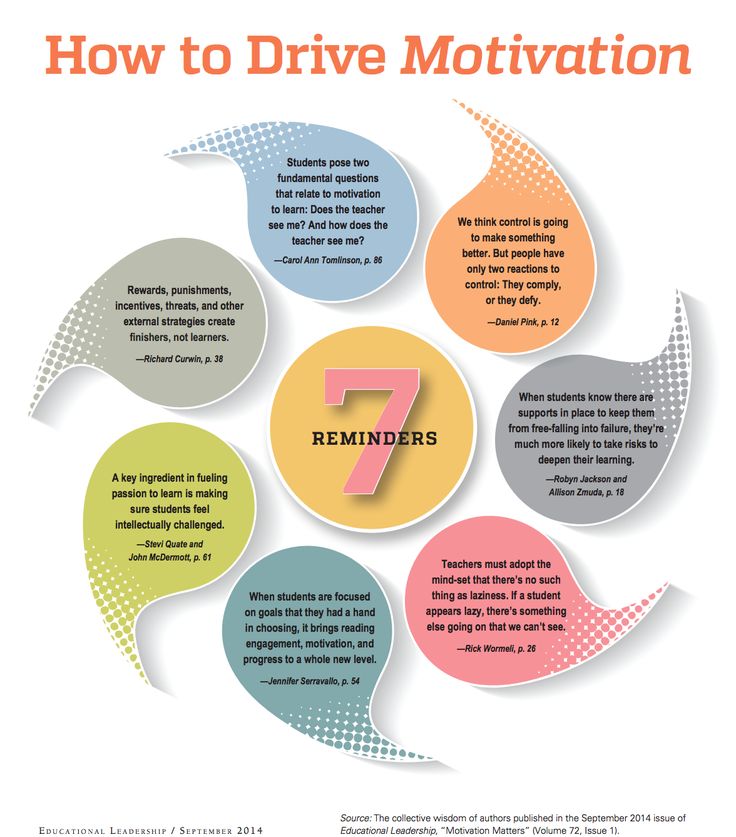

In his 1999 presidential address to the Society for the Teaching of Psychology, Neil Lutsky offered a possible answer. He noted that “success in teaching depends mainly on capturing and organizing students’ attention.” There is perhaps no better way to capture and keep your students’ attention than by sharing your passion for psychology — and for teaching psychology — with them. Psychology’s national award-winning teachers all agree on this point (e. g., Irons et al., 2007). Teachers must be enthusiastic about their subject matter if they wish their students to become interested studying the subject matter. There is no single best way for teachers to express their passion in the classroom; it differs for all of us. However, aspects of our personal presence in the classroom such as facial expression, voice inflection, hand gestures, and body posture often suggest to students that we are particularly excited about the material we are sharing with them (Buskist, Sikorski, Buckley, & Saville, 2002). We might do well to heed Brewer’s (2002) oft-quoted advice: “For all your learning and teaching, develop a passion that approaches religious fervor” (p. 504).

g., Irons et al., 2007). Teachers must be enthusiastic about their subject matter if they wish their students to become interested studying the subject matter. There is no single best way for teachers to express their passion in the classroom; it differs for all of us. However, aspects of our personal presence in the classroom such as facial expression, voice inflection, hand gestures, and body posture often suggest to students that we are particularly excited about the material we are sharing with them (Buskist, Sikorski, Buckley, & Saville, 2002). We might do well to heed Brewer’s (2002) oft-quoted advice: “For all your learning and teaching, develop a passion that approaches religious fervor” (p. 504).

Jane Halonen (2005, Para. 19) offered an insightful observation for maintaining your students’ interest once you have captured it. “The gift of great teachers is the ability to help students find meaning in what we ask them to learn.” Passion for the subject matter and for teaching well goes a long way in maintaining students’ interest in the course. However, teachers should never doubt the power of a good example, particularly if it is significantly connected to real life, in keeping students’ intellectually engaged in class. The learning experience is particularly powerful when students are engaged in activities that have personal relevance in understanding oneself as well as others (Fink, 2003).

However, teachers should never doubt the power of a good example, particularly if it is significantly connected to real life, in keeping students’ intellectually engaged in class. The learning experience is particularly powerful when students are engaged in activities that have personal relevance in understanding oneself as well as others (Fink, 2003).

Where do compelling examples come from? One could look at the classic studies in psychology — these studies are significant not merely because of elegant experimental design, but because they inform us about something particularly relevant in our lives. Fortunately, psychology has no shortage of such studies. One need not look any further than an introductory psychology text to find scores of such examples. The trick in sharing these studies with students is to tell them as a story — why the issue is important, how the study was conducted, what the specific findings were — and then relate it to some aspect of students’ lives. Telling students only about a study’s scientific value is not enough to engender interest, let alone excitement, in most students. Another source of examples rests with the students themselves. Taking time to chat with students about their interests, hobbies, and aspirations often sets the stage later for tying a psychological principle to what students are currently experiencing in their lives. For instance, through these discussions you may learn that a student’s family owns a successful small business and he or she plans to become involved in the business after graduation. Chances are that you may have several students in any one class who plan to enter the business world once they graduate. This situation provides an excellent opportunity to introduce the class to industrial/organizational psychology and to share an example or two about how this field ties to these students’ interests and aspirations. You might even ask your student with the family business to share with the class the particular problems this business typically encounters, and then provide examples of how an I/O psychologist might approach developing a solution to such issues.

Another source of examples rests with the students themselves. Taking time to chat with students about their interests, hobbies, and aspirations often sets the stage later for tying a psychological principle to what students are currently experiencing in their lives. For instance, through these discussions you may learn that a student’s family owns a successful small business and he or she plans to become involved in the business after graduation. Chances are that you may have several students in any one class who plan to enter the business world once they graduate. This situation provides an excellent opportunity to introduce the class to industrial/organizational psychology and to share an example or two about how this field ties to these students’ interests and aspirations. You might even ask your student with the family business to share with the class the particular problems this business typically encounters, and then provide examples of how an I/O psychologist might approach developing a solution to such issues.

Talking with students before class, after class, and at other times also shows them that you care about them as learners (Lowman, 1995; Wilson & Taylor, 2001). Demonstrating caring is an essential step in establishing rapport with your students — the contextual superglue that binds student and teacher together in the quest for learning and self-improvement. Of course, there are many elements to developing rapport with a class in addition to using real-life examples. Most of these elements consist of teacher behaviors that are easy to implement in the classroom such as smiling, calling students by name, maintaining eye contact, using inclusive language such as “we” and “us,” moving about the classroom, using humor, and being encouraging of student progress (Benson, Cohen, & Buskist, 2005; Buskist & Saville, 2001; Teven & Hanson, 2004; Titsworth, 2001; Wilson & Taylor, 2001).

A Final Thought

Making a difference is not about what we teach. Rather, it is about how we teach. Although instructors devote untold hours to preparing lectures and classroom activities focused squarely on the subject matter, in the end making a difference in students’ lives appears to have little to do with course content per se. What matters more, at least from a general student perspective, is that teachers create a supportive and caring classroom atmosphere in which they can inspire their students to become more confident, motivated, and effective life-long learners while conquering the subject matter. It is essential for teachers not only to consider how students will benefit intellectually from coursework, but also how students will benefit personally and emotionally from it. ♦

Although instructors devote untold hours to preparing lectures and classroom activities focused squarely on the subject matter, in the end making a difference in students’ lives appears to have little to do with course content per se. What matters more, at least from a general student perspective, is that teachers create a supportive and caring classroom atmosphere in which they can inspire their students to become more confident, motivated, and effective life-long learners while conquering the subject matter. It is essential for teachers not only to consider how students will benefit intellectually from coursework, but also how students will benefit personally and emotionally from it. ♦

References

Benson, T. A., Cohen, A. L., & Buskist, W. (2005). Rapport: Its relation to student attitudes and behaviors toward teachers and classes. Teaching of Psychology, 32, 236-238.

Brewer, C. L. (2002). Reflections on an academic career: From which side of the looking glass? In S. F. Davis & W. Buskist (Eds.), The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie (pp. 499-507). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

F. Davis & W. Buskist (Eds.), The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie (pp. 499-507). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Buskist, W., & Saville, B. K. (2001, March). Rapport-building: Creating positive emotional contexts for enhancing teaching and learning. APS Observer, 14(3), 12-13, 19.

Buskist, W., Sikorski, J., Buckley, T., & Saville, B. K. (2002). Elements of master teaching. In S. F. Davis & W. Buskist (Eds.), The teaching of psychology: Essays in honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie and Charles L. Brewer (pp. 27-39). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Halonen, J. S. (2005). The path of less trouble. In T. A. Benson, C. Burke, A. Amstadter, R. Siney, B. Beins, V. W. Hevern, & W. Buskist (Eds.), Teaching in autobiography: Perspectives from psychology’s exemplary teachers. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from http://teachpsych.lemoyne.edu/teachpsych/eit/index.html

Buskist (Eds.), Teaching in autobiography: Perspectives from psychology’s exemplary teachers. Retrieved March 1, 2010, from http://teachpsych.lemoyne.edu/teachpsych/eit/index.html

Irons, J. G., Beins, B., Burke, C., Buskist, W., Hevern, V. W., & Williams, J. (Eds.). (2007). The teaching of psychology in autobiography: Perspectives from psychology’s exemplary teachers (Vol. 2). Retrieved February 27, 2010, from http://www.teachpsych.org/resources/e-books/tia2006/tia2006.php

Lowman, J. (1995). Mastering the techniques of teaching (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lutsky, N. (1999, August). Not on the exam: Teaching, psychology and the examined life. Paper presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA.

Svinicki, M., & McKeachie, W. J. (2011). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (13th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Teven, J. J., & Hanson, T. L. (2004). The impact of teacher immediacy and perceived caring on teacher competence and trustworthiness. Communication Quarterly, 52, 39-54.

Titsworth, B. S. (2001). The effects of teacher immediacy, use of organizational lecture cues, and students’ notetaking on cognitive learning. Communication Education, 50, 283-297.

Weimer, M. E. (1993). The disciplinary journals on pedagogy. Change, 25(6), 44-51.

Wilson, J. H., & Taylor, K. W. (2001). Professor immediacy behaviors associated with liking students. Teaching of Psychology, 28, 136-138.

How Teachers Make a Difference in Students Lives

If you think about it, school is the place where students spend more time than with their own families. It is the place where young people learn the most things before they enter the workforce than anywhere else.

Teachers can have a lot of influence and this can become even more evident when there are problems at home.

At the beginning of my life, before I took many different career directions, I was a French and English teacher. In this article, I will share my views on how teachers can positively impact students’ lives.

How Teachers Make a Difference

Most people who are successful in life today were once helped by someone else. In most cases, these people were supported by their teachers. For this reason, most of them are grateful for what their former teachers did for them. They do not forget how their teachers helped them and encouraged them when things were bad for them or when it seemed like there was no hope.

We have all had teachers who have impacted our lives in one way or another. We have all had teachers who inspired us to cultivate our talents, pursue our dreams, and prepare for the future. Some teachers can inspire students to learn more and do their best. Others can discourage students from succeeding. That’s why it’s important for every teacher to understand that they have the power to positively or negatively impact their students’ lives.

The same is true for many other successful people today. In almost all cases, you will find that the people who are successful today were once helped by someone in their past – someone who cared about them and wanted them to succeed in life.

Therefore, it is important that we teach our students not only academic knowledge but also the values that will help them improve their lives.

How Can Teachers Have a Positive Impact on Students?

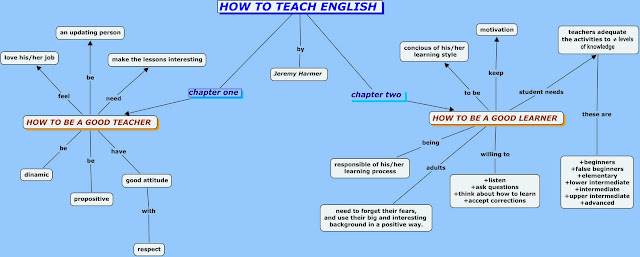

Teachers can motivate students to achieve great things – both inside and outside the classroom. Teachers who truly love their jobs are able to transfer that passion for learning to their students.

When a good teacher is excited about learning, that enthusiasm can spread like wildfire and ignite a passion for learning in every student. This passion for knowledge can lead students to great success throughout their lives – both personally and professionally.

Through Education

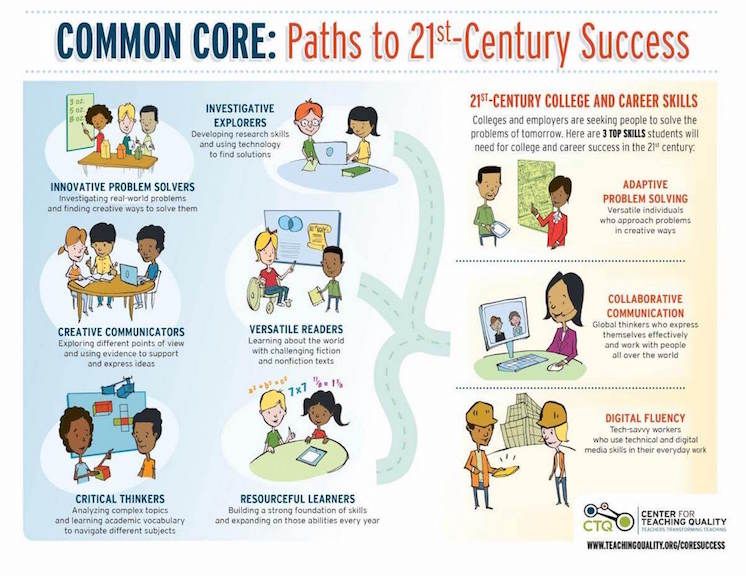

While teachers and educators have many different roles in education, their primary role is teaching. This means they must be able to effectively teach the lesson plan and pass on knowledge in a way that is easy for students to understand – so it will lead them to academic success.

This means they must be able to effectively teach the lesson plan and pass on knowledge in a way that is easy for students to understand – so it will lead them to academic success.

In addition, they must be able to motivate students by creating a positive learning environment, encouraging enthusiasm for learning, and providing positive reinforcement to students who perform well.

To accomplish these tasks, teachers must possess a number of qualities beyond a college degree or teaching credential. In fact, it is possible that the most important quality of a teacher is something that cannot be learned in school.

Here are five qualities teachers need to have a positive impact on their students:

- Empathy

- Sense of humor

- Clear communication skills

- Creativity

- A positive attitude

Recognition of Students’ Potential

The teaching profession is a tough job, but not everyone knows that.

If you are a prospective teacher for the first time, you may think that being a good teacher is about teaching a specific skill, creating a lesson plan, using some good teaching strategies, and learning things that you learn during your teacher education.

However, what many people do not know is that teaching is one of the most difficult professions in the world. Teachers not only have to teach and convey a subject matter and certain material but a good educator also has to be able to understand and help his students, and sometimes encourage positive behavior.

A good teacher is able to observe and be receptive. For example, some young people are shy or afraid to ask questions in class, or simply have difficulty expressing themselves verbally in front of others; a good teacher should watch for such signs in their students so they can help them if necessary. A good educator must also be able to motivate students to learn by making lessons interesting and fun for them.

In addition, effective teachers must be creative, always coming up with new ways to make learning interesting and fun for young people, especially if they’re a middle school or high school teacher where their students may begin to take an interest in things other than their academic success.

From my experience, I believe that all students have great potential, and it is the teacher’s approach that helps them develop that potential or keeps them from exploring it further.

Through Feedback

Feedback is important for many reasons. One is that students learn to accept constructive criticism so they can learn to move forward better in life and put their egos aside. Another reason is that feedback can provide the right advice that could be their golden ticket to a better future. It’s as important as a test score, because a test score does not always tell the whole story, nor does it give advice on which soft skill to improve.

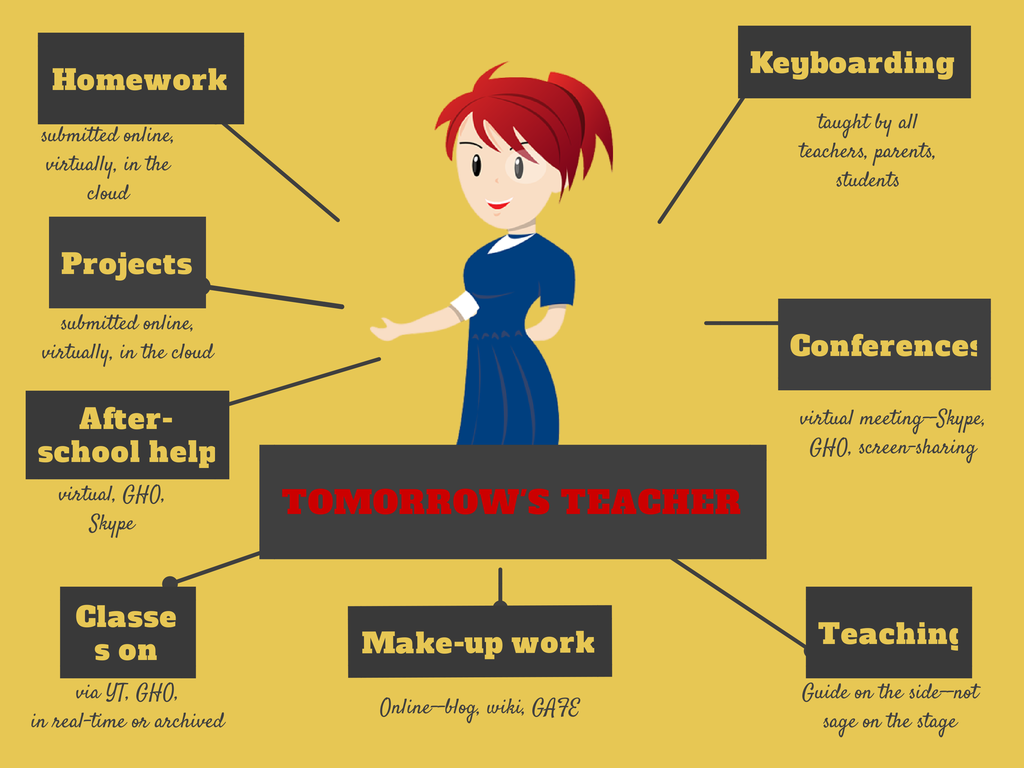

By Creating a Speech Bubble

The role of an effective teacher goes far beyond just teaching a subject matter and standardized tests. Great teachers create an environment where students want to learn and are actively engaged. This is where interpersonal skills come into play.

Great teachers create an environment where students want to learn and are actively engaged. This is where interpersonal skills come into play.

A teaching profession also requires creating a safe space for learning, students are more likely to share their ideas and try new things without fear of failure.

For example, when I was teaching English Language Learners in Thailand, my high school students had to give a presentation in English. Some of them were shy, isolated, and often afraid to speak up. By putting them in a group of more confident students and giving those who had the confidence the responsibility of making sure each individual in the group succeeded, the weaker students made progress and integrated better. It gave them a sense of achievement and encouraged them to take a positive behavior in class.

Here are 4 tips to help develop those interpersonal skills and make a positive difference in the classroom:

- Use positive language

- Build rapport with students

- Create a safe place to learn

- Make yourself available

Inspire Them and Be Role Models

Teachers challenge students to think outside the box and take on new challenges with confidence. They are also there to support students when they take risks and fail – an important lesson students need to learn to succeed in life.

They are also there to support students when they take risks and fail – an important lesson students need to learn to succeed in life.

They can motivate students to achieve great things – both inside and outside the classroom.

Those who truly love their jobs can share that passion for learning with their students. When a teacher is passionate about learning, that enthusiasm can spread like wildfire and ignite a passion for learning in every student. This passion for knowledge can lead students to great success throughout their lives – both personally and professionally.

Aspiring teachers are like candles – consuming themselves to light the way for others. They lead by example through their own actions and deeds, inspiring students to follow them.

Students can see you as a role model and want to be like you. When they admire you and recognize your good qualities, they will want to behave in a way that they know will please them and make them more like you.

By Helping Them Choose a Career

Students often decide on a career, or at least their first work experience, while they are still in school. A teacher can introduce their students to different careers and discuss the pros and cons of each. Some teachers even organize a field trip for the class so they can get an idea of a particular profession. This is a great opportunity for your students to learn about different careers and what it takes to be successful in that career.

Teachers can help students identify their strengths and weaknesses by identifying them early on. Then they can tailor their curriculum to address those strengths and weaknesses.

This will help students develop self-confidence and self-monitor their behavior. This will help them feel more confident in their future careers.

Give Confidence

Students who feel encouraged by their teachers are more likely to try new things and take risks if they feel they can succeed.

Encouragement from teachers can come in many different forms, such as verbal praise, positive reinforcement, and high expectations for all students. If you feel your teacher believes in you, you will want to try harder and achieve more than if you do not feel encouraged by him or her.

If you feel your teacher believes in you, you will want to try harder and achieve more than if you do not feel encouraged by him or her.

When students feel that their talents are recognized and valued by their teachers, they are more likely to cultivate them and use them for personal growth.

By Teaching Values

When a teacher teaches students the value of hard work and commitment, he or she encourages them to prepare for a promising future by giving them the tools they need to succeed in school and in life. Students who learn that without hard work there is nothing worthwhile will be able to forgo instant gratification for greater rewards later.

Influence on Parents

It’s not always possible, and it’s often a very touchy subject as it depends on the situation, but I have occasionally seen parents be receptive to the advice of teachers, and sometimes this can even improve the relationship between parent and child.

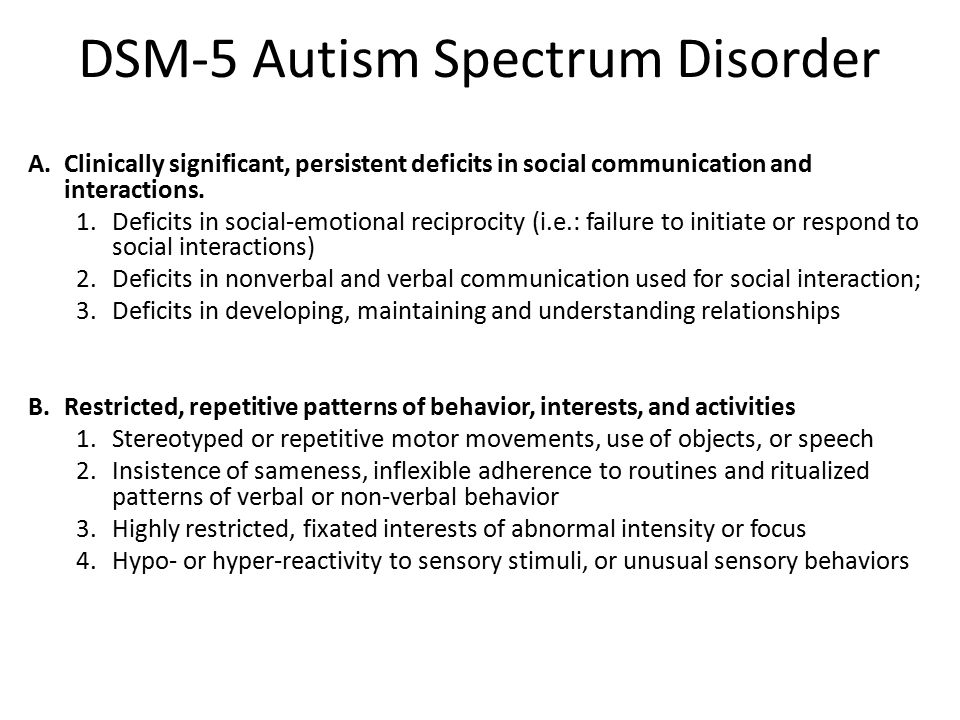

For example, a teacher may identify autism or a special talent that explains why parents can not understand their child’s behavior at home because they spend less time with their child than they would like. If you are a teacher who identifies a disability, it is best to discuss this with your principal first, as each school has a different policy and often has experience with how to deal with parents on such issues.

If you are a teacher who identifies a disability, it is best to discuss this with your principal first, as each school has a different policy and often has experience with how to deal with parents on such issues.

There is also the issue of what is considered acceptable parenting in different families or cultures.

We should not judge others by our own standards of parenting, but we cannot deny that some parenting styles lead to negative outcomes for children. Some parents need professional help when their mental illness is harming their children or when there is domestic violence in the family, but unfortunately, many of these families do not know what services are available to them or they fear the consequences.

Schools are the backbone of our society; they are where the youth learn, grow and develop into adults. Schools are not only for education, but also for socializing, learning social skills, and finding a sense of belonging. Teachers are the ones who spend the most time with students during these years, so it is their job to make sure students feel safe both in school and in their community.

Teachers are the ones who spend the most time with students during these years, so it is their job to make sure students feel safe both in school and in their community.

Teachers have a duty to make sure their students are safe while they are in our classrooms and also when they leave school. They can do this by speaking up when something about a student’s situation strikes them as odd, or by simply asking how their day was. Teachers should always be on the lookout for signs of abuse or neglect, as children may not know how to report it themselves.

The community benefits from teachers who actively work to protect their children because they can identify abuse or neglect early before it escalates into something more dangerous like homicide or suicide.

When young children feel that no one cares about them, tragedies occur. Therefore, it is important that preschool teachers (or kindergarten teachers), elementary school teachers, or high school teachers do everything in their power to prevent such problems, for example, by talking to the principal, who may suggest a special education teacher.

These problems are usually most obvious in elementary school, middle school, and high school. Once students reach higher education, it’s often too late to intervene, especially if the student needs special education. However for master’s degree students, there can be support at the college for personal problems, but it’s up to young people to decide whether to take the plunge and seek help.

What Makes Good Teachers?

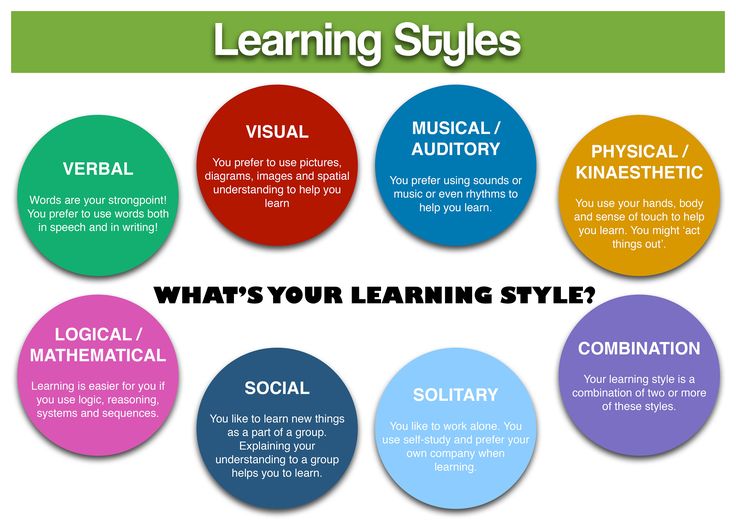

Good teachers promote learning in their classrooms by using a variety of techniques and strategies to teach their students. They use a variety of methods to help students learn, and they know that each student learns in his or her own way. The best teachers adapt their methods to meet the needs of their students.

A great teacher does not only have a good teaching style, he’s good at listening. An effective teacher listens to what his students are saying to better understand them, and he also listens to what his students are not saying to be aware of any problems. These are just some of the things that make good teachers.

These are just some of the things that make good teachers.

Whether you teach in a traditional classroom or at home, there are many ways to communicate your strengths and weaknesses. Share your experiences with students, and develop different learning methods.

- Understand the context of your teaching environment and students’ life.

- Demonstrate your ability to use various student teaching techniques individually and in combination with other techniques.

- Develop various measures of student learning, including teacher portfolios, student work samples, and teacher-student conferences.

- Share student experiences that relate to strengths and weaknesses, such as work experience and personal interests.

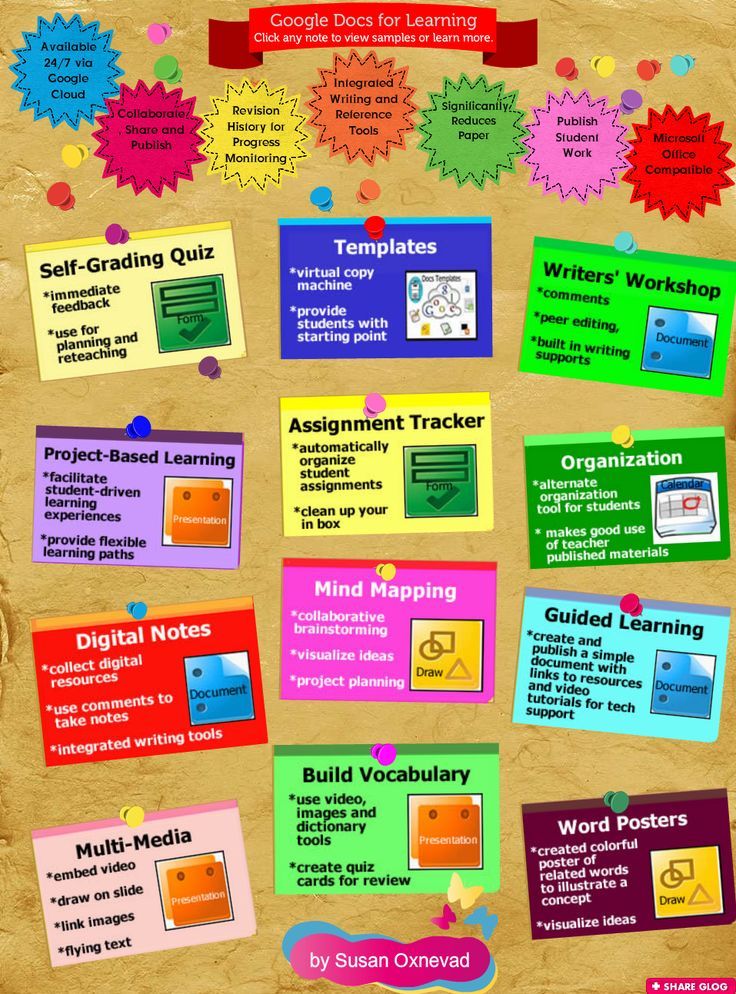

- Incorporate technology (if you’re allowed by the school) into your teaching style. Students tend to associate teacher quality with modernity.

Teachers Matter

Learning with an educator is not just about the teacher’s effectiveness and teaching strategies in a particular subject matter and the test score students end up with, but also about the teacher’s quality, which can boost student achievement and professional development later in life.

Aspiring teachers can make a big difference in their students’ life and they can influence positive behavior.

Related: What Are Positive Influences

The Teaching Profession Is a Job With Many Responsibilities

Many people think that a teacher only works a few hours a day, takes his paycheck, and has lots of vacation time. That’s true for some teachers. But the average teacher works more than 8 hours a day, and they don’t get a high salary. We say that young people are our future, and I’d say that teachers are also the future, because they can make a difference for our future if we support them.

Method 4 Form Matters . Mastery of the teacher [Proven methods of outstanding teachers] [litres]

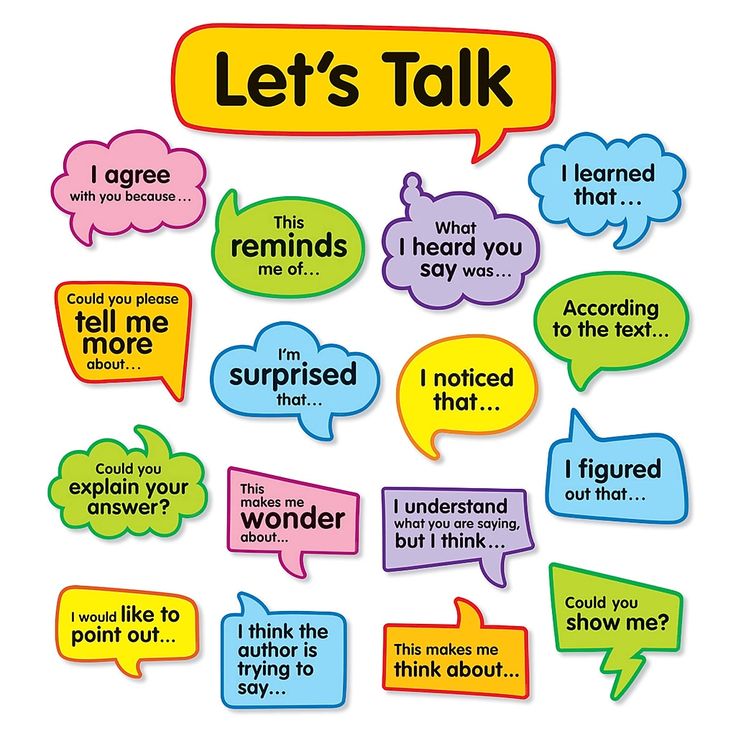

In school, the medium itself carries an important message: in order to succeed and meet the requirements of specific situations and society, students must be able to articulate their thoughts and communicate them in a variety of effective forms. It is important not only that what the student says , but also that how he says it. Powerful battering ram for college - complete sentence. For college admission, an applicant must write an essay demonstrating fluency in syntax (as with every written work once he becomes a student). For interviews with potential employers, you need to be able to correctly agree on the subject and predicate. Prepare your students for academic and career success by requiring full, grammatical answers whenever possible. Use the “Form matters” technique for this.

It is important not only that what the student says , but also that how he says it. Powerful battering ram for college - complete sentence. For college admission, an applicant must write an essay demonstrating fluency in syntax (as with every written work once he becomes a student). For interviews with potential employers, you need to be able to correctly agree on the subject and predicate. Prepare your students for academic and career success by requiring full, grammatical answers whenever possible. Use the “Form matters” technique for this.

Teachers who understand the importance of this methodology rely on the basic submission requirements listed below.

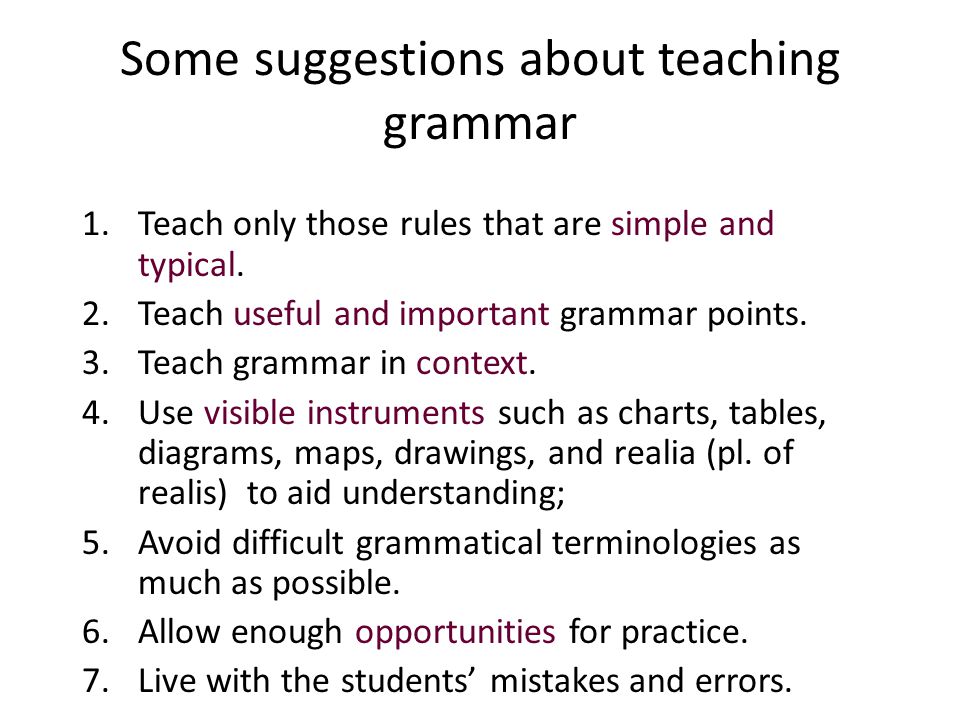

• Grammar format. Yes, you must pay attention to the inadmissibility of slang, correct syntax, word usage and grammar, even if you are sure that in some situations deviation from the standard is acceptable and normal and if the student's speech is an example of a "school dialect". Or rather, that's how you perceive it. You may not know how the family or community in which the child lives speaks and what is considered normal or acceptable in their opinion. There are many examples of children choosing dialects or trying to speak differently than their parents or their families expect them to.

Or rather, that's how you perceive it. You may not know how the family or community in which the child lives speaks and what is considered normal or acceptable in their opinion. There are many examples of children choosing dialects or trying to speak differently than their parents or their families expect them to.

The range of opinions and options here is huge. To make it easier to determine what is considered a standard, whether it is the only correct form of language, and whether it is generally correct in essence, master teachers are based on a much narrower but practical premise. They assume that there is a so-called language of opportunity - that is, a kind of code that signals readiness to speak in front of the widest possible audience. This code represents the ease of use of forms of language that are used in work, study, and business. According to this code, the noun agrees with the verb, the words are used in the traditional sense, and the rules are learned and followed exactly. If your students prefer to switch every day and use the language of opportunity selectively, in particular only in a school environment, so be it. But one of the fastest ways to help students is to focus on preparing to successfully compete for jobs and college places. And for this, you should ask them to constantly monitor the speech in the class and correct any errors and shortcomings. There is always a time and place to engage students in a broader sociological discussion about dialect: under what circumstances is it acceptable to use it, who determines its correctness, what is the degree of subjectivity in this definition, what are the wider consequences of switching from code to code, and so on. Given the frequency of very real student errors and the huge potential losses that result from not correcting these errors, it is extremely important to find simple methods for identifying and correcting speech errors with minimal distraction from the learning process. Then you will be able to correct errors constantly and imperceptibly.

If your students prefer to switch every day and use the language of opportunity selectively, in particular only in a school environment, so be it. But one of the fastest ways to help students is to focus on preparing to successfully compete for jobs and college places. And for this, you should ask them to constantly monitor the speech in the class and correct any errors and shortcomings. There is always a time and place to engage students in a broader sociological discussion about dialect: under what circumstances is it acceptable to use it, who determines its correctness, what is the degree of subjectivity in this definition, what are the wider consequences of switching from code to code, and so on. Given the frequency of very real student errors and the huge potential losses that result from not correcting these errors, it is extremely important to find simple methods for identifying and correcting speech errors with minimal distraction from the learning process. Then you will be able to correct errors constantly and imperceptibly. Two simple methods are especially effective.

Two simple methods are especially effective.

• Identify error. If the student makes a grammatical error, simply repeat what was said in an interrogative tone: “We three went to the garden?”, “Did the boy eat a roll?” And let the child correct himself. If he fails, use the following method, or just quickly give the correct answer yourself and ask the student to repeat it.

• Start repair. If the student makes a grammatical error, rephrase their answer so that it sounds grammatically correct and let the child complete the sentence. Using the examples above, say: "We are three together …” “Boy ate …” and let the student complete the correct wording himself.

• Full offer form. Try to have your students practice impromptu complete sentences as often as possible. If the child responds with a fragment of a phrase or in general with one word, use one of the following methods.

You could, for example, say the first words of a complete sentence to show your child how it should begin.

Teacher: James, how many tickets are in the basket?

James: Six.

Teacher: In the basket…

James: There are six tickets in the basket.

Another method is to remind the student how to answer before the student answers.

Teacher: Who can tell me in full sentence what is the time and place of this work?

Student: The story takes place in Los Angeles in 2013.

And the third method is to remind about this requirement later with the help of a quick and simple hint that practically does not interrupt the course of the educational process.

Teacher: In what year was Julius Caesar born?

Student: In the hundredth year BC.

Teacher: Say in full sentence.

Student: Julius Caesar was born in 100 BC.

Some teachers use the code "like a literate person" to remind children to use full sentences. For example: "Who can tell me the same thing, but as a literate person?"

• Sound format. There is no point discussing answers with thirty people if only a few hear you. If your words are important enough for the whole class to hear, speak in a way that everyone can hear. Otherwise, the discussion in the class and the participation of the student in it turn into unnecessary, untimely banter. Make sure students listen to their classmates, insist that they respond loudly and clearly. By accepting an answer that the other students haven't heard, you're demonstrating that it doesn't really matter much.

Perhaps the most effective way to send the opposite signal to the class is to quickly and clearly, with as little distraction as possible, to remind the children to speak so that everyone can hear you. For example, say to a girl whose voice is barely audible, one single word: "sound. " This is much better than exhorting her for five seconds: “Maria, we can’t hear you at the end of the class. Please follow the voice." And this is better for three reasons. First, it's more efficient. In business terms, here we are dealing with low-level transaction costs. In terms of time, the most valuable asset of a school education, it's worth next to nothing. In the time it takes for a less experienced teacher to have the student's response heard by the whole class, in the manner of the above example with Maria, the master teacher casually reminds the girl three or four times to answer louder.

" This is much better than exhorting her for five seconds: “Maria, we can’t hear you at the end of the class. Please follow the voice." And this is better for three reasons. First, it's more efficient. In business terms, here we are dealing with low-level transaction costs. In terms of time, the most valuable asset of a school education, it's worth next to nothing. In the time it takes for a less experienced teacher to have the student's response heard by the whole class, in the manner of the above example with Maria, the master teacher casually reminds the girl three or four times to answer louder.

Transaction costs is the amount of resources needed to carry out an exchange: economic, verbal or any other. The goal of every teacher is to make sure that any necessary intervention in the course of the lesson minimally distracts the class from the task being solved, from what it is doing. Therefore, when reminding children of something, one should try to get by with an absolute minimum of words.

Second, by saying the single word "sound" instead of verbosely describing what you expect from the student, you show the children that explanations are superfluous. In the class, you need to answer so that everyone can hear, this is obvious. And your brief reminder makes it clear that you initially expect a loud and intelligible answer from the responder, and not at all asking him for a favor. Thirdly, by clearly and concisely pointing out to the student what needs to be done to correct what has been done wrong, the teacher avoids accusations of nitpicking. This allows him to maintain a good relationship with the child and, if necessary, to make comments so often that his expectations become predictable and, therefore, most effective in changing the student's behavior.

The last point deserves special attention and additional discussion. One day, several colleagues and I were present at the lesson of one teacher. During the lesson, she reminded the students four or five times to speak louder and more clearly, but used the word louder than for this, and not the sound. Thus, over and over again, she emphasized the absence of something, some kind of deficiency, constantly emphasizing that her expectations were not being met. She told the class "a long negative story." We will discuss this idea further when we talk about the 43 Positive Framing technique in Chapter 7. Word sound, on the contrary, would serve as a quick reminder, clearly indicating to the child what is expected of him.

Thus, over and over again, she emphasized the absence of something, some kind of deficiency, constantly emphasizing that her expectations were not being met. She told the class "a long negative story." We will discuss this idea further when we talk about the 43 Positive Framing technique in Chapter 7. Word sound, on the contrary, would serve as a quick reminder, clearly indicating to the child what is expected of him.

My colleagues have also noted that some teachers use the word sounding with a subtlety that would not be achieved by using the word louder than . For example: “Jason, could you use the sound of your voice to tell the class how to find the least common multiple?” or "I need a student whose voice is high enough to tell the whole class what to do next!"

As a result, my colleagues and I came to the conclusion that when working with the sound format, the short and capacious word sound is the gold standard.

• Units format. In math and science classes, always replace "bare numbers" (without specifying units) with "clothed" numbers. For example, if you ask a student what the area of a rectangle is and he says 12, ask him to name the unit of measure, or just say that the number needs to be dressed, that it looks badly dressed to you.

In math and science classes, always replace "bare numbers" (without specifying units) with "clothed" numbers. For example, if you ask a student what the area of a rectangle is and he says 12, ask him to name the unit of measure, or just say that the number needs to be dressed, that it looks badly dressed to you.

KEY MESSAGE

“SHAPES MATTER”

It is not just what students say that matters, but how they communicate their message. To be successful in life, they need to learn to articulate their thoughts in the language of opportunity.

Thinking about the quality of teaching in universities

Nowadays, the priority direction in the activities of universities in China is to provide high quality educational services. The quality of education is influenced by many factors, but it is ensured, first of all, by the educational quality of teachers. Evaluation of the quality of teaching is especially important in terms of stimulating teaching staff to improve the quality of teaching and improve teaching methods. This article is devoted to the analysis of values, indicators and standards for assessing the quality of teaching staff, designing procedures for assessing the educational quality of teachers in universities.

Evaluation of the quality of teaching is especially important in terms of stimulating teaching staff to improve the quality of teaching and improve teaching methods. This article is devoted to the analysis of values, indicators and standards for assessing the quality of teaching staff, designing procedures for assessing the educational quality of teachers in universities.

Keywords: teaching quality assessment, teaching quality

And in 2012, their number reached 6.8 million, that is, within ten years the number of new students increased by 3 times. In this regard, the problem of maintaining and improving the quality of educational services is acute.

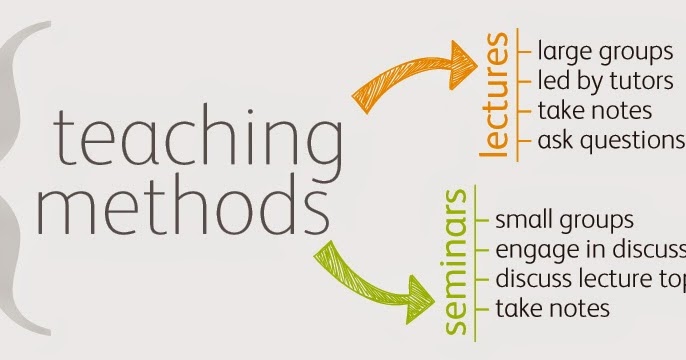

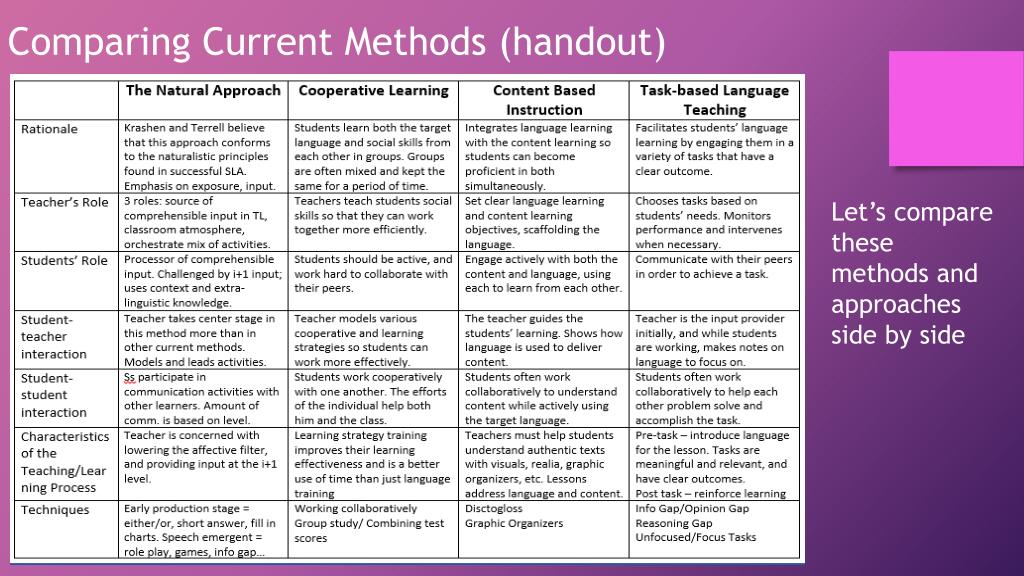

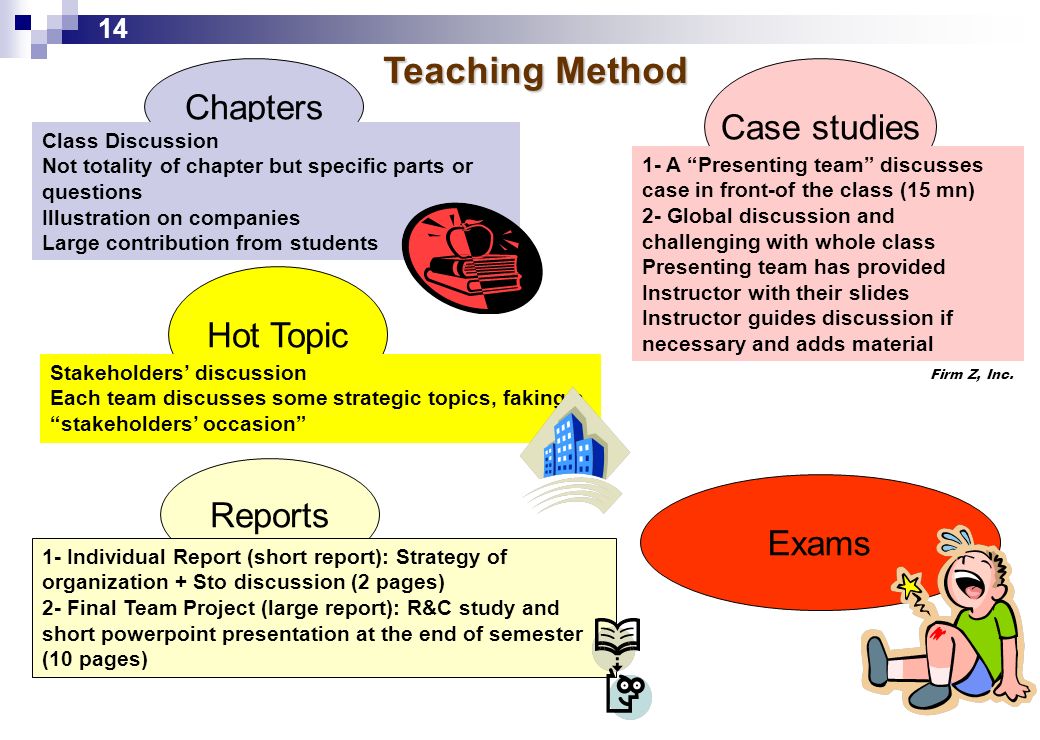

In universities, lecture-based teaching is the main teaching method and determines the quality of education in universities. Teaching contains many elements such as the conditions of learning, the degree of difficulty of the lectures, the teaching of teachers, the effectiveness of learning, etc. All these elements are interconnected with each other. Teaching is the most important link and directly determines the level of training of specialists. Therefore, the assessment of the quality of teaching (hereinafter referred to as the EQP) is of relevance in stimulating teachers to improve the quality of education.

All these elements are interconnected with each other. Teaching is the most important link and directly determines the level of training of specialists. Therefore, the assessment of the quality of teaching (hereinafter referred to as the EQP) is of relevance in stimulating teachers to improve the quality of education.

1. The importance of assessing the teaching quality of teachers

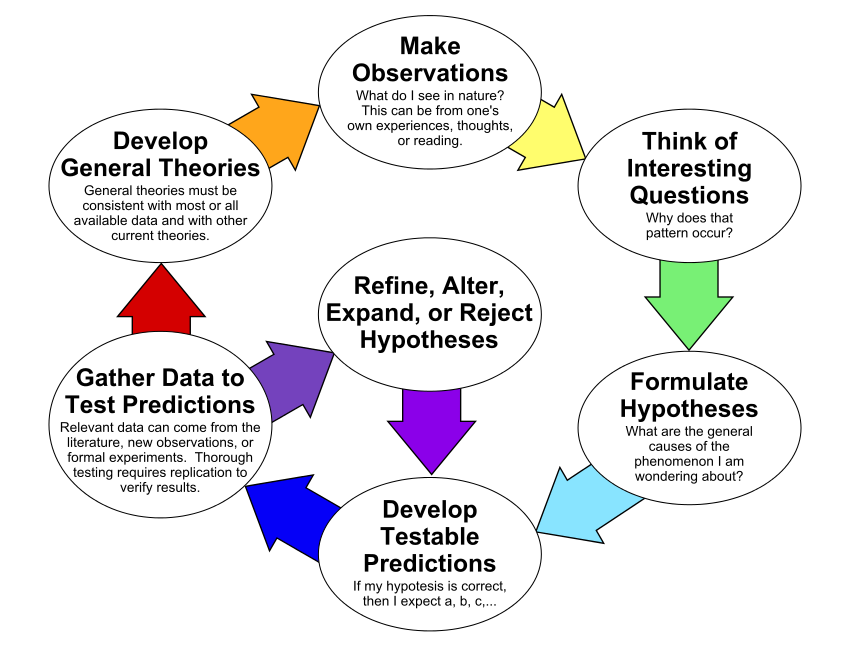

First, the assessment of the teaching quality of teachers diagnoses and improves learning activities. Scientific and technological development requires continuous transformation in the process of training specialists in the field of higher education in order to meet the ever-growing need for the country's economic construction and social development. Regularly conducting RCT, collecting a large amount of educational information, it is possible to systematically analyze the learning process, detect problems in a timely manner and improve educational services, and stimulate in-depth transformation in universities.

Secondly, the OKP will reorganize the management of the faculty in a scientific way. EQP is focused on accurately determining the quality of the teaching staff, obtaining feedback for taking action in universities, helps the management to fully and accurately understand the state of teaching, provides the basis and objective standards for the correct implementation of measures, the implementation of scientific management of universities.

Thirdly, the OKP contributes to the improvement of the teacher himself. Evaluation will help teachers to detect problems in the implementation of training, analyze the causes of their occurrence, find methods for their resolution, and thus contribute to the development and progress of the teacher himself.

2. Indicators and standards for learning assessment

Indicators and standards are inherently linked. In the operation of the OKP, on the one hand, evaluation indicators serve as the basis for standards, evaluation standards are inconceivable without indicators, standards are also a measure for checking the degree of implementation of indicators. The standards define the learning objectives. On the other hand, standards and indicators are relative, in some cases they turn from one type to another: the content of the indicators is converted into standards and vice versa.

The standards define the learning objectives. On the other hand, standards and indicators are relative, in some cases they turn from one type to another: the content of the indicators is converted into standards and vice versa.

Indicators, as the basis of the GST, in modern Chinese mean "necessarily achieved goals set in the plan" and at the same time serve as specific, measuring sub-goals. Features of educational goals are manifested by evaluating these sub-goals.

The RCS standards for construction are divided into three types: the personality standard of teachers, the standard of their responsibility and the standard of teaching effectiveness. The three standards are relatively independent of each other and organically linked. In the activities of the OKP, all three standards must be taken into account. One-sided consideration of one of the standards will make the assessment of learning inaccurate.

3. Designing procedures for GPV indicators in universities

A series of rigorous, scientific and regulatory procedures and methods must be adopted in order to adequately carry out the design of GPV indicators. In general terms, the design of procedures includes the following:

In general terms, the design of procedures includes the following:

3.1. Develop the first edition of indicators and evaluation standards. At the same time, it is necessary to create a special commission on the OKP, draw up models of indicators and evaluation standards.

According to the principle of design, first of all, it is necessary to divide the learning objectives into specific indicators. At the same time, it must be taken into account that the procedure for indicators is drawn up according to a certain logic and criteria in the classification of objects. It is necessary to develop each branch-indicator in as much detail as possible. Those indicators for which it is difficult to establish specific quantitative (in quantitative terms) requirements must be described in precise language in order to most adequately check the status of their implementation.

3.2. Classify and combine

In the initially developed system of OKP, there inevitably exists such a situation as repetition among themselves, the content of each other, contradiction, ambiguity and setting the question “upside down”. At the same time, indicators and standards to some extent do not reflect the essential features of the object of assessment. Therefore, having compiled an assessment system, it is necessary to analyze it comprehensively using an integrated approach: the inductive method, analysis of statistical data, a qualitative study of the problem in order to select the necessary and discard the secondary, to classify and combine. Thus, indicators and standards embody the principle of their design.

At the same time, indicators and standards to some extent do not reflect the essential features of the object of assessment. Therefore, having compiled an assessment system, it is necessary to analyze it comprehensively using an integrated approach: the inductive method, analysis of statistical data, a qualitative study of the problem in order to select the necessary and discard the secondary, to classify and combine. Thus, indicators and standards embody the principle of their design.

3.3. Reasoning by experts

To ensure the objectivity and foresight of the developed system of the OKP, it is necessary to conduct an expert analysis, involve relevant specialists, experts on this issue. It is necessary to discuss relevant issues in the form of a questionnaire. In conclusion, according to experts, it is necessary to conduct a generalization, statistical analysis, and compile an official table of the OKP.

3.4 Pre-checking and argumentation

After discussion by experts, select points for putting the OKP into action, in the process of verification, clarify how valid the opportunity to disseminate it and existing issues.

When choosing items, attention should be paid to the following: a) adopt a random selection method, thereby guaranteeing the representativeness of exemplary items; b) take into account the integrality (range) of the selected samples, that is, the representativeness of the samples needs to be ensured by their integrality. This will allow you to make as few mistakes as possible in the selection of samples. Based on the results of the audit, it is necessary to carry out a comprehensive change in the system of indicators of the OKP. At the same time, it is necessary to take into account the opinion of theoretical workers, relevant individuals and society, to extract rational proposals for further revision of indicators and evaluation standards.

3.5 Work on the final text and application in practice

After the above procedures, it is necessary to once again discuss the draft system of indicators for the CCP, only after that it is possible to work on the final text. When creating the final text, it is still necessary to select points for production in an experimental order, and, based on the results of this work, to process and form the final system of the OKP.

When creating the final text, it is still necessary to select points for production in an experimental order, and, based on the results of this work, to process and form the final system of the OKP.

4. Quantitative table of OKP in universities

After the system of OKP indicators is established, for the purpose of convenient application in universities, a quantitative table is usually compiled, in which information is recorded in the field of teacher training. Such a table embodies the system of indicators of the OKP, serves as the basis for assessing the quality of teaching in universities.

4.1. The components of the quantitative table OKP

The table in its structure consists of three parts - indicators, standards and categories for assessing the quality of teaching.

4.2. Purpose of the quantitative table OKP

This table is used by teachers, students and learning managers. It allows teachers to note their strengths and weaknesses in teaching, students to convey their feedback to the managing department, and managers to discover general issues in the teaching of teachers, take measures to solve them. The Quantitative Table is useful for three parts of the learning process. Like a node, it connects teachers, students and administrators, serving as a reliable way of contact between three parties.

The Quantitative Table is useful for three parts of the learning process. Like a node, it connects teachers, students and administrators, serving as a reliable way of contact between three parties.

4.3. Compilation of a quantitative table OKP

It is necessary to comprehensively design a quantitative table so that it not only demonstrates the teaching process, but also shows the effectiveness of teaching. The table shows both the assessment of learning and the assessment of the complex personality of teachers, including the attitude to learning, content, methodology, abilities, teaching effectiveness.

First step: arrange the indicators in a certain format, describe the indicators in a clear and understandable language.

Second step: assign a score to each indicator.

The third step: set the conditional parameter of the OCR indicators. First of all, it is necessary to determine the point equivalent for each category.

Literature

1.