Jung's dream theory

Jung and Dreams - Society of Analytical Psychology

Jung & Dreams, By Marcus West

“Dreams are impartial, spontaneous products of the unconscious psyche, outside the control of the will. They are pure nature; they show us the unvarnished, natural truth, and are therefore fitted, as nothing else is, to give us back an attitude that accords with our basic human nature when our consciousness has strayed too far from its foundations and run into an impasse.”

[Collected Works Volume 10, paragraph 317]

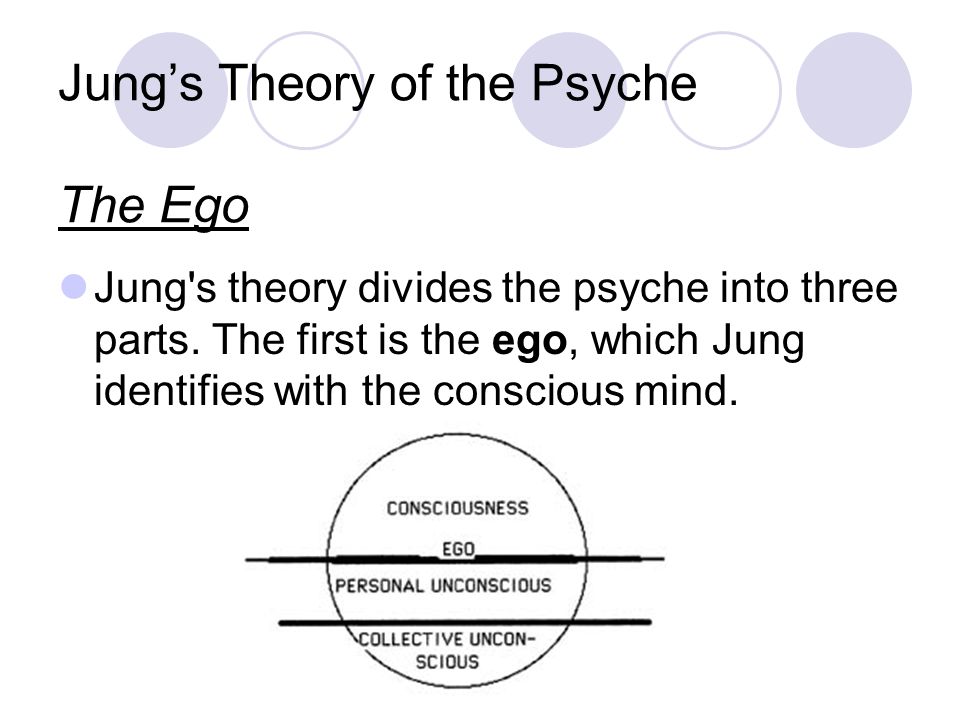

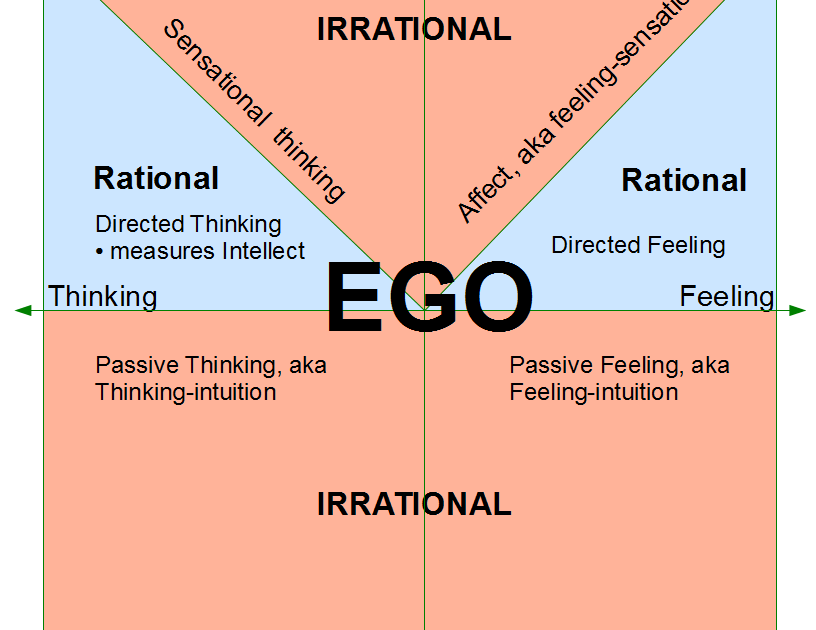

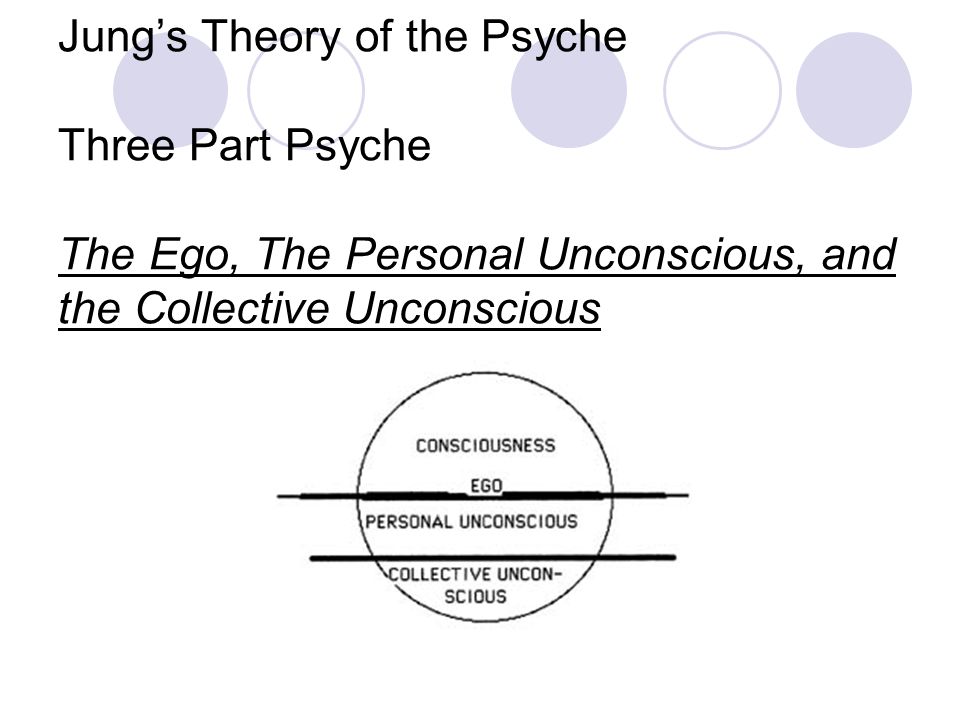

Jung saw the mind/body/feelings (or what he called ‘the psyche’) as all working together. Even negative symptoms could be potentially helpful in drawing attention to an imbalance; for example, depression could result from an individual suppressing particular feelings or not following a path that is natural and true to their particular personality. In this way he saw the psyche as a self-regulating system with all psychic contents – thoughts, feelings, dreams, intuitions etc.

– having a purpose; he thought the psyche was ‘purposive’.

The value of dreams

Jung saw dreams as the psyche’s attempt to communicate important things to the individual, and he valued them highly, perhaps above all else, as a way of knowing what was really going on. Dreams are also an important part of the development of the personality – a process that he called individuation.

Disguise

Whilst Freud thought that dreams expressed forbidden wishes that had to be disguised (he differentiated the manifest content of a dream – what was on the surface, from the latent content – what was hidden), Jung saw dreams as expressing things openly. He wrote:

“They do not deceive, they do not lie, they do not distort or disguise … They are invariably seeking to express something that the ego does not know and does not understand.” [CW 17, para. 189]

Symbols

If dreams are sometimes difficult to comprehend it is because we need to understand that dreams express themselves through the use of symbols. Of symbols Jung wrote:

Of symbols Jung wrote:

“A symbol is the best possible formulation of a relatively unknown psychic content”.

He also wrote, the dream is “a spontaneous self-portrayal, in symbolic form, of the actual situation in the unconscious” [CW 8, para. 505].

A symbol doesn’t just tell us about what the dream may appear to be about on the surface, but has meaning and resonance above and beyond the particular situation. As Marie Louise von Franz said:

“The unconscious doesn’t waste much spit telling you what you already know”

In expressing what is not known, particularly related to an imbalance, Jung thought that dreams were a form of compensation.

Compensation

One of Jung’s own dreams gives a good example of compensation; the dream concerned one of his patients. She was an intelligent woman but Jung noticed that increasingly in their sessions there was a shallowness entering into their dialogue. He determined to speak to her about this, but the night before the session he had the following dream:

He determined to speak to her about this, but the night before the session he had the following dream:

He was walking down a highway through a valley in late-afternoon sunlight. To his right was a steep hill. At its top stood a castle, and on the highest tower was a woman sitting on a kind of balustrade. In order to see her properly he had to bend his head far back. He awoke with a crick in his neck. Even in the dream he had recognised the woman as his patient. [Memories, Dreams and Reflections, p. 155]

Jung said that the interpretation was immediately apparent to him. If, in the dream, he had had to look up to the patient in this fashion, in reality he had probably been looking down on her – the dream had been a compensation for his attitude toward her.

Jungian dream analysis example

If we look at a dream that Jung used to describe his particular approach to dreams this may become clearer. A woman patient dreamt as follows:

She is about to cross a wide river. There is no bridge, but she finds a ford where she can cross. She is on the point of doing so, when a large crab that lay hidden in the water seizes her by the foot and will not let her go. (She wakes up in terror). [CW 7, para. 123]

There is no bridge, but she finds a ford where she can cross. She is on the point of doing so, when a large crab that lay hidden in the water seizes her by the foot and will not let her go. (She wakes up in terror). [CW 7, para. 123]

It is worth pausing to remember what Jung says about dream interpretation at this point:

“So difficult is it to understand a dream that for a long time I have made it a rule, when someone tells me a dream and asks for my opinion, to say first of all to myself: ‘I have no idea what this dream means’. After that I can begin to examine the dream”.

There are a number of symbols in his patient’s dream: the river, crossing a river, a ford, a crab, and the foot. To begin to understand the meaning of these symbols Jung asked his patient for her associations to the dream.

She said she thought the river formed a boundary that was difficult to get across, something she had to overcome, probably something to do with the treatment. She thought the ford offered a way of overcoming the difficulty, probably in the treatment. She associated the crab with cancer which she thought was a terrible disease, of which she was afraid and which had killed an acquaintance, Mrs X. The crab obviously wanted to drag her into the river, and she was terribly frightened.

She thought the ford offered a way of overcoming the difficulty, probably in the treatment. She associated the crab with cancer which she thought was a terrible disease, of which she was afraid and which had killed an acquaintance, Mrs X. The crab obviously wanted to drag her into the river, and she was terribly frightened.

“What keeps stopping me getting across?” she mused, “Oh yes, I had another row with my friend [a woman]”.

Jung describes his patient’s relationship with her friend as “a sentimental attachment, bordering on the homosexual, which has lasted for years”.

The dreamer adds that Mrs X had “an artistic and impulsive nature which the dreamer felt was punished by the cancer – in particular, Mrs X had an affair with an artist after her husband died”.

The objective vs. the subjective level

This dream could therefore be taken on an objective level, which would treat the dream images as corresponding to objects in the real world. On this level the dream could be about a fear of cancer and of following in Mrs X’s footsteps – being impulsive, having an affair, and experiencing terrifying consequences – being pulled under the ‘water’ by the cancer. This could also be described as an interpretation on the personal level.

On this level the dream could be about a fear of cancer and of following in Mrs X’s footsteps – being impulsive, having an affair, and experiencing terrifying consequences – being pulled under the ‘water’ by the cancer. This could also be described as an interpretation on the personal level.

Jung, however, made his interpretation on the subjective level. Here, he says – and this is a characteristically Jungian position – that every object in the dream corresponds to an element within the individual’s own psyche. Thus the river, the crab and all the associated elements refer to the dreamer’s own psyche.

Jung’s interpretation was, therefore, that the crab in the dream was pulling the dreamer back into the unconscious – the river – to confront the unacknowledged, not lived-out, and unhumanised part of her own personality – her own artistic and impulsive nature, as well as her own ‘masculine’ nature. The dream was trying to compensate for the absence of these qualities in her waking life.

Amplification

Jung interpreted that this was the masculine aspect of the dreamer’s nature as the crab has seized the dreamer by the foot. Jung amplified the dream symbol of the foot with reference to his own understanding of the symbolic meaning feet. Such amplifications could be with reference to any kind of mythical, religious, fairytale, archetypal association.

Jung linked the foot with the myth of Osiris and Isis (he would not necessarily tell the patient this link), and concluded that “the foot, as the organ nearest the earth, represents in dreams the relation to earthly reality and often has a phallic significance.” He also made a link to Oedipus [which literally means ‘swell-foot’] which he understood as ‘suspicious’, in other words, someone who was not well related to reality. [CW 5 para. 356] This relates the dream to the archetypal level, in other words those elements of the psyche that are common to all of us, like the masculine nature.

The Transference Level

When Jung said to his patient that he thought she had a powerful masculine nature, she did not recognise it, seeing herself as ‘fragile, sensitive, and feminine’. Jung wondered why she did not acknowledge her own masculine traits, so evident to him in relation to her friend. This brought him to another aspect of the dream – the transference level (the relationship to the analyst).

Jung wondered why she did not acknowledge her own masculine traits, so evident to him in relation to her friend. This brought him to another aspect of the dream – the transference level (the relationship to the analyst).

Whilst the dream images can correspond to different parts of the dreamer’s own psyche, they can also correspond to people in the objective world, as well as to the analyst in so far as the analyst may embody what the dream image is symbolising. This is the essence of a symbol – that it can apply in a number of different situations. This is what Jung found in this case.

His patient told him that when she was not with him, Jung appeared to her as “rather dangerous and sinister, like an evil magician or demon”. Jung therefore interpreted that he, Jung, was acting as the dangerous, masculine, foot-gripping crab (bearing the projection of his patient’s masculinity) and it was this dependent relationship with Jung, like that with her friend, which prevented her from crossing the river.

When he suggested all this to his patient she had “an unexpected feeling of hatefulness and despising toward her friend”. Jung suggests that “the repression of the hateful, masculine qualities was broken and, at that moment, the patient entered a new phase of life without even knowing it”.

Jung’s work on the inner, subjective level had incarnated, humanised and personalised these archetypal qualities – the impetuous, dangerous, hateful, despising, ‘masculine’ qualities – and thereby, instead of being possessed by these qualities unknowingly, she would be able to use those qualities in the service of her fuller life.

We can see that by treating the dream images as symbols, with the images all representing elements within the dreamer’s own psyche, and by asking for the dreamer’s personal associations to the dream, as well as amplifying other images with relation to archetypal themes, we are able to understand a dream and what it may be trying to communicate to the dreamer – usually by way of compensating for the dreamer’s current, conscious attitude, which is in some way one-sided or incomplete.

A final thought on dreams

Jung wrote:

“I have noticed that dreams are as simple or as complicated as the dreamer is himself, only they are always a little bit ahead of the dreamer’s consciousness. I do not understand my own dreams any better than any of you, for they are always somewhat beyond my grasp and I have the same trouble with them as anyone who knows nothing about dream interpretation. Knowledge is no advantage when it is a matter of one’s own dreams.” [CW 18, para. 244]

About Marcus West

Marcus is a training analyst with the SAP. He has written Understanding Dreams in Clinical Practice (published by Karnac 2011). See Marcus’s website.

Jung’s Theory of Dreams: A Reappraisal

Source: Kelly Bulkeley

The ideas of C.G. Jung (1875-1961) remain a valuable source of guidance into the world of dreams.

Many other theories have been proposed since his time, and some of his thinking now appears dated in light of later scientific and cultural developments. But his core works on the nature and meaning of dreaming still stand as perhaps the most deeply insightful writings about dreams of any Western psychologist, past or present.

But his core works on the nature and meaning of dreaming still stand as perhaps the most deeply insightful writings about dreams of any Western psychologist, past or present.

Below is a brief outline of some of the major concepts and themes in Jung’s theory of dreams. (A second post will include further ideas from his works.)

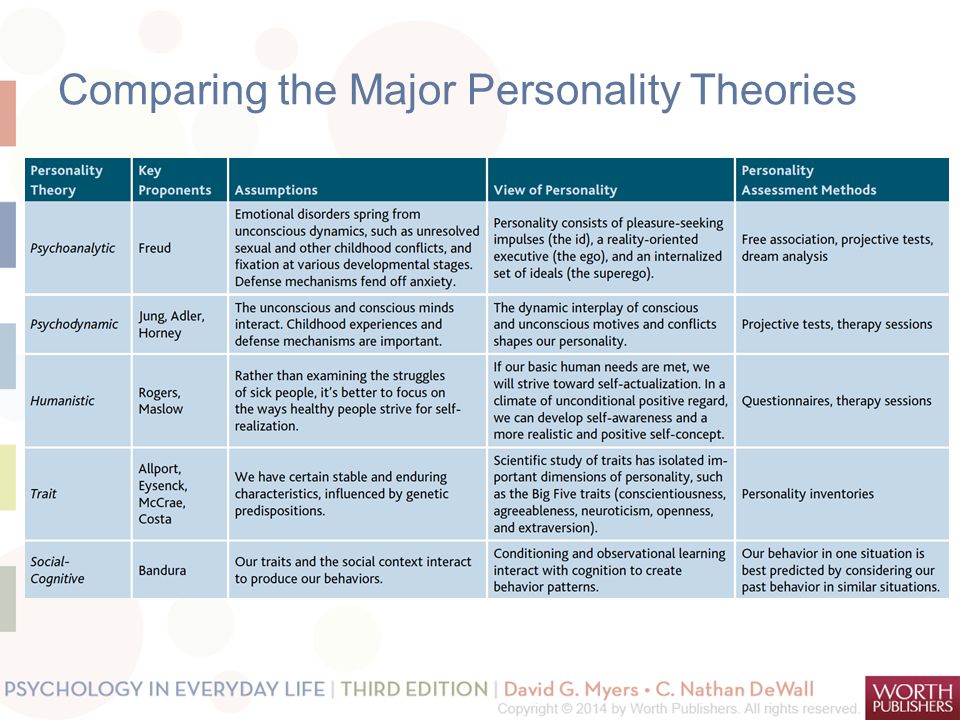

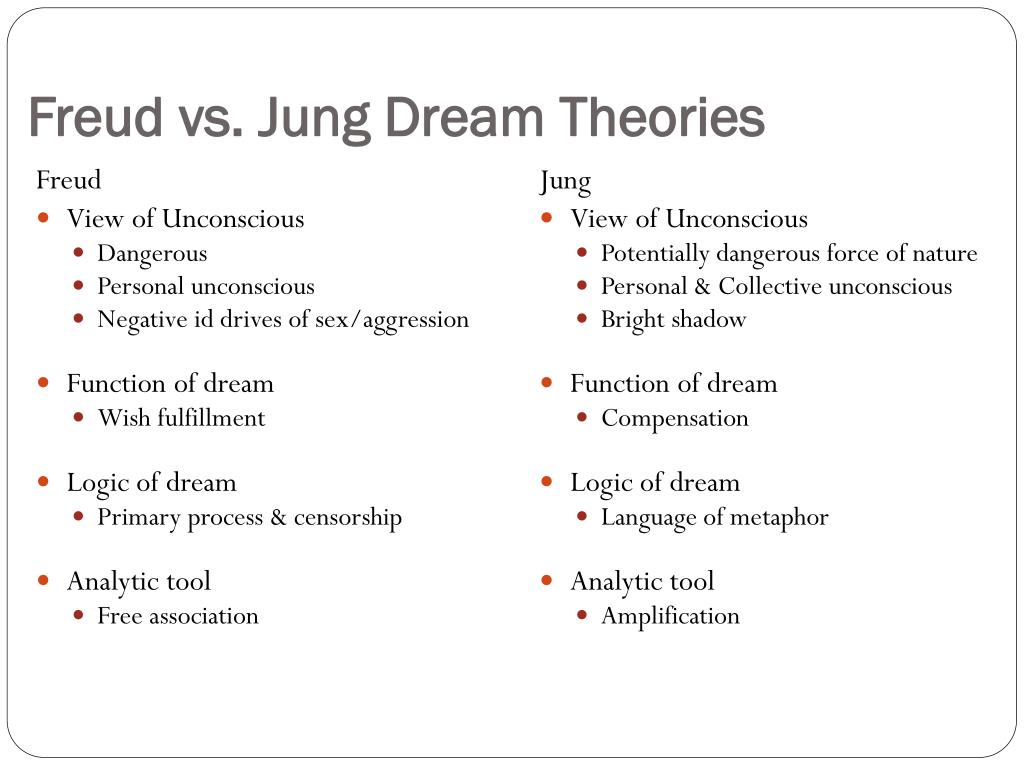

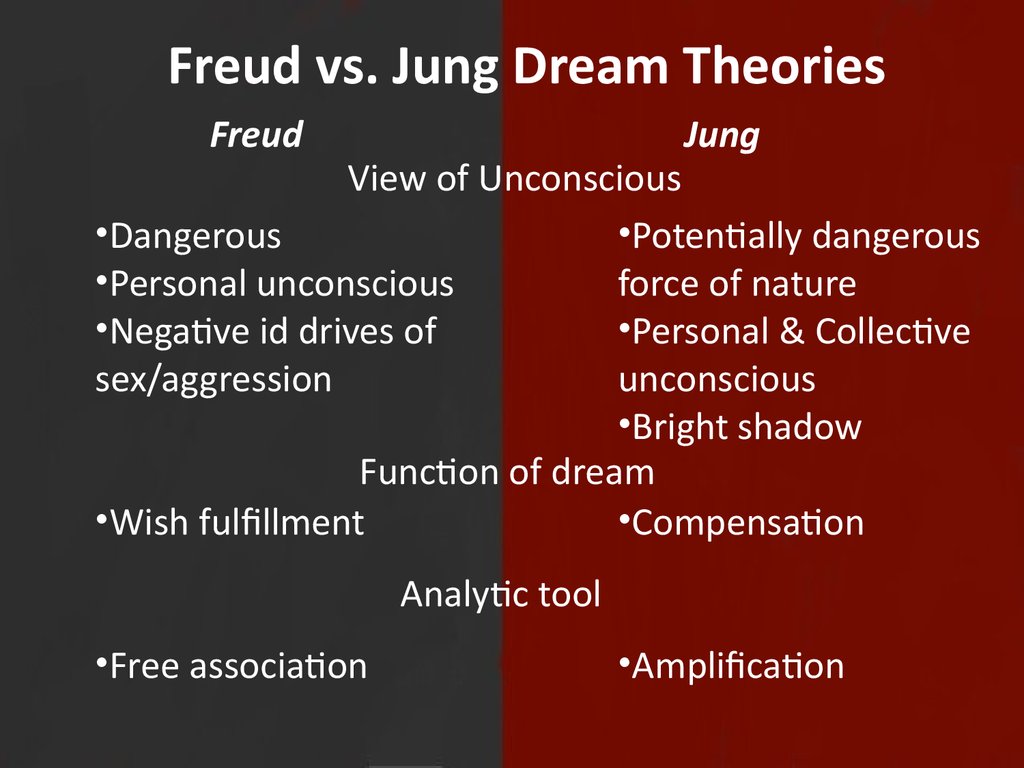

Lots of agreement with Freud, and one big difference

Jung learned several key ideas from his early mentor, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). Both Jung and Freud agreed that dreaming is a meaningful product of unconscious forces in the psyche with roots deep in the evolutionary biology of our species. Both of them agreed that dreams are valuable allies in healing people suffering from various kinds of mental illness. They both used the best neuroscience of their day to inform their theories, and they both went beyond the limits of brain science to seek insights about the nature of dreaming in mythology, history, and art. Both of them believed a greater knowledge of dreaming could help us better understand the philosophical mysteries of how the mind and body interact.

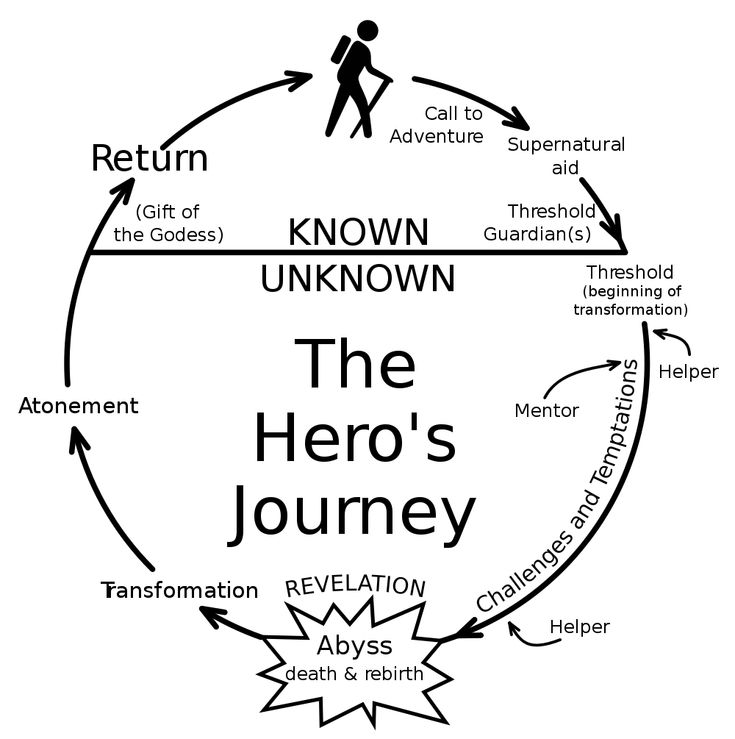

The most fundamental difference in Freud’s and Jung’s dream theories was this: Freud’s approach looked backward, and focused on the causal sources of dreams in early life experiences. Jung’s approach looked forward and tried to understand where the dreams might be leading, and what they might reveal about the individual’s future life development.

Compensation

The primary function of dreaming, according to Jung, is psychological compensation. Dreams help maintain a healthy, dynamic balance between consciousness and the unconscious. When the waking ego becomes too one-sided, or if it tries to repress a part of the unconscious, dreams will emerge to highlight the imbalance and guide the individual back on a path towards becoming a more integrated self.

“The fundamental mistake regarding the nature of the unconscious is probably this: it is commonly supposed that its contents have only one meaning and are marked with an unalterable plus or minus sign.

In my humble opinion, this view is too naïve. The psyche is a self-regulating system that maintains its equilibrium just as the body does. Every process that goes too far immediately and inevitably calls forth compensations, and without these, there would be neither a normal metabolism nor a normal psyche. In this sense, we can take the theory of compensation as a basic law of psychic behavior…. When we set out to interpret a dream, it is always helpful to ask: What conscious attitude does it compensate?” (1934, 101)

Reductive compensations

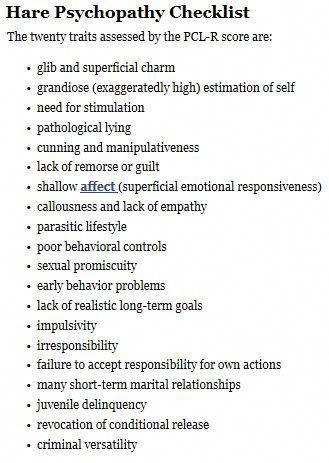

Sometimes the compensation can take a critical form, which Jung called reductive compensations. Dreams sometimes bring a chastening dose of humility when the waking ego becomes too inflated or self-important (the ancient Greeks called it hubris).

According to Jung, dreams give us honest portrayals of who we really are. If we think too highly of ourselves, the compensatory nature of the psyche will bring forth dreams that bring us back down into our depths. If we are too impressed with our own goodness and moral righteousness, we will be prone to dreams reminding us of our sins, our failings, our evil impulses, our hypocritical rationalizations, and ego-protecting deceptions.

If we are too impressed with our own goodness and moral righteousness, we will be prone to dreams reminding us of our sins, our failings, our evil impulses, our hypocritical rationalizations, and ego-protecting deceptions.

“There are people whose conscious attitude and adaptive performance exceed their capacities as individuals; that is to say, they appear to be better and more valuable than they really are…. They have not grown inwardly to the level of their outward eminence, for which reason the unconscious in all these cases has a negatively compensating, or reductive, function…. Every appearance of false grandeur and importance melts away before the reductive imagery of the dream, which analyses his conscious attitude with pitiless criticism and brings up devastating material containing a complete inventory of all his most painful weaknesses.” (1948a, 43-45)

The prospective function

Dreams can have many different functions, and Jung did not insist that every dream fits into one of his categories. But in addition to compensation, he proposed another major function of dreaming, which he called the prospective function. This is not prophecy, although it does overlap with traditional religious views about dreams offering glimpses and visions of possibilities for the future.

But in addition to compensation, he proposed another major function of dreaming, which he called the prospective function. This is not prophecy, although it does overlap with traditional religious views about dreams offering glimpses and visions of possibilities for the future.

Jung said the prospective function focuses primarily on the future growth of the individual along the path towards greater psychological integration and wholeness. If we can learn to understand these prospective dreams, they can offer an important source of unconscious intelligence and insight.

“The prospective function is an anticipation in the unconscious of future conscious achievements, something like a preliminary exercise or sketch, or a plan roughed out in advance…. That the prospective function of dreams is sometimes greatly superior to the combinations we can consciously foresee is not surprising, since a dream results from the fusion of subliminal elements and is thus a combination of all the perceptions, thoughts, and feelings which consciousness has not registered because of their feeble accentuation….

With regard to prognosis, therefore, dreams are often in a much more favorable position than consciousness.” (1948a, 41-42)

Archetypal images and “big dreams”

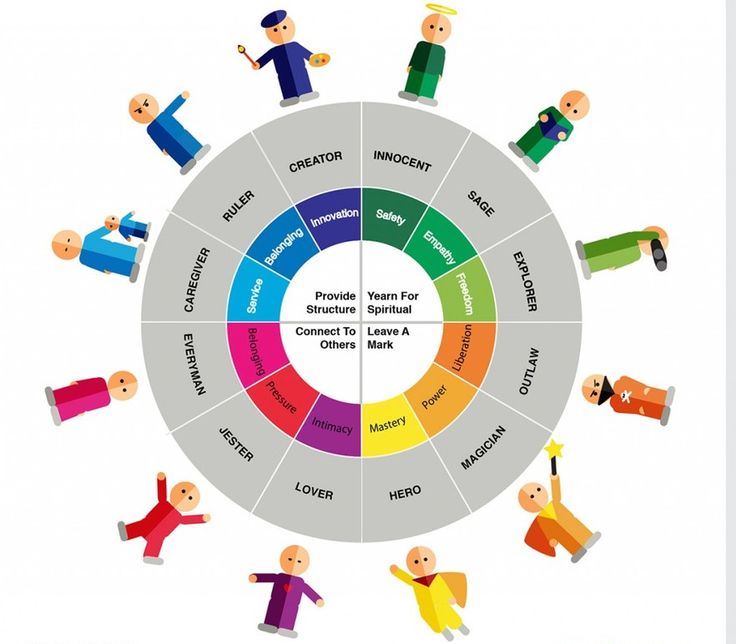

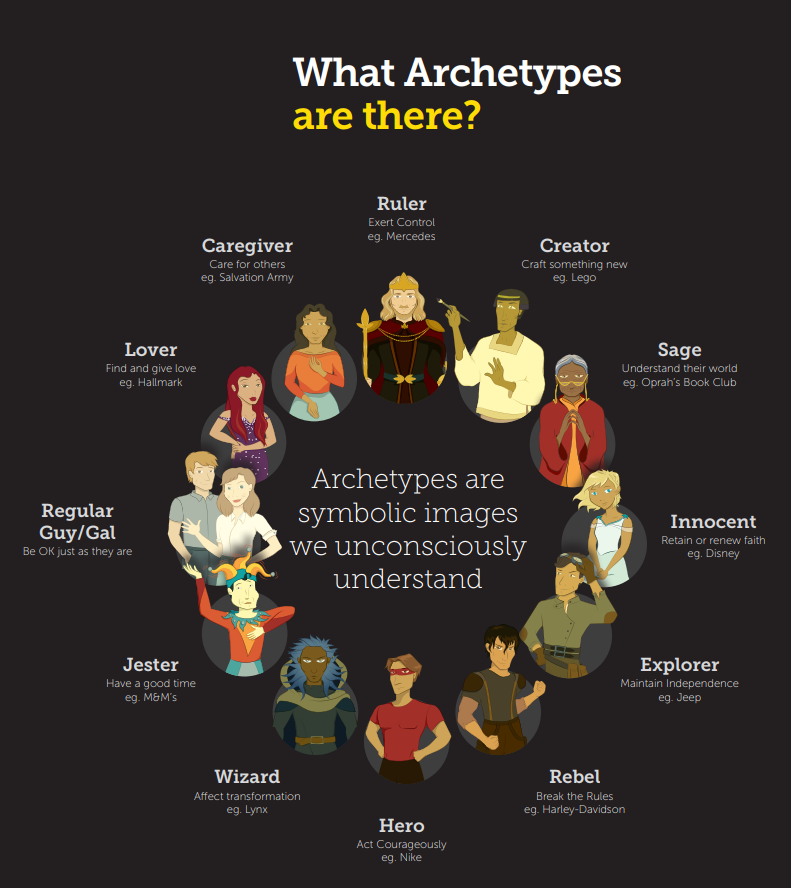

Jung put great emphasis on dreams with extremely vivid images. He regarded them as expressions of deeper unconscious patterns of instinctual meaning and wisdom he called archetypes. These dream images help to connect us with the primal energies of the psyche, whose ultimate developmental goal is our wholeness as humans, what Jung calls individuation.

Hence Jung’s interest in the distinction between “big” and “little” dreams. Big dreams revolve around powerful archetypal images from the collective unconscious. Such dreams are guideposts along the path of individuation.

“Not all dreams are of equal importance. Even primitives distinguish between ‘little’ and ‘big’ dreams, or, as we might say, ‘insignificant’ and ‘significant’ dreams. Looked at more closely, ‘little' dreams are the nightly fragments of fantasy coming from the subjective and personal sphere, and their meaning is limited to the affairs of the everyday.

That is why such dreams are easily forgotten, just because their validity is restricted to the day-to-day fluctuations of the psychic balance. Significant dreams, on the other hand, are often remembered for a lifetime, and not infrequently prove to be the richest jewel in the treasure-house of psychic experience.” (1948b, 76)

Carl Gustav Jung "Memories, Dreams, Reflections" - review from dear_bean

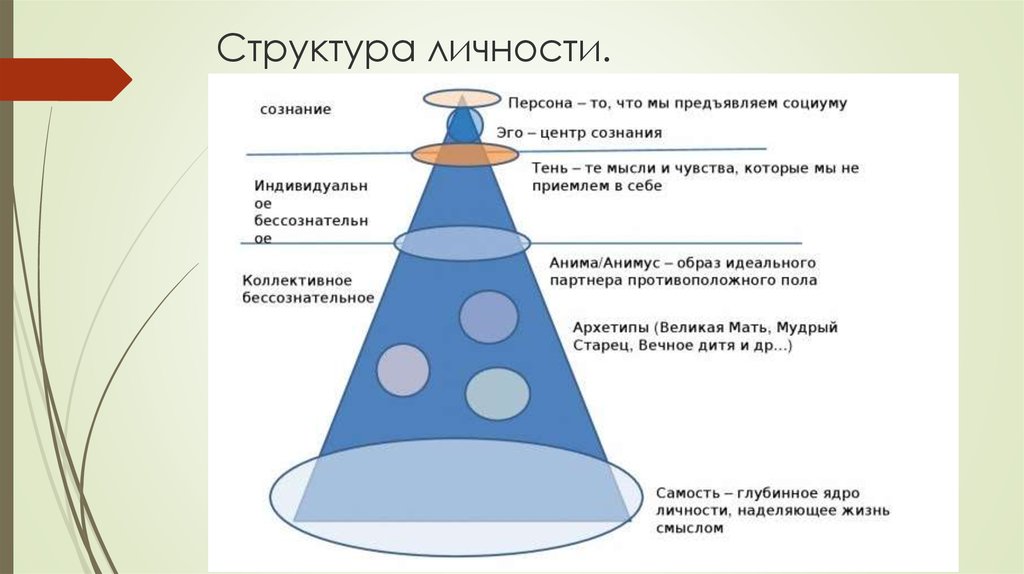

Carl Gustav Jung - Swiss psychologist and philosopher, founder of "analytical psychology". This is a story of life with an emphasis on the most significant things, especially on the intricacies of the life path. This is a story about the formation of Jung, about finding his place in the scientific field. It is not an autobiographical confession in the usual sense - it does not offer the mysteries of life, but instead points to the places where emotions and fantasies together reveal life's key milestones and fundamental landmarks. It is more subtle and complex than the theory described in reduced Jungianism.

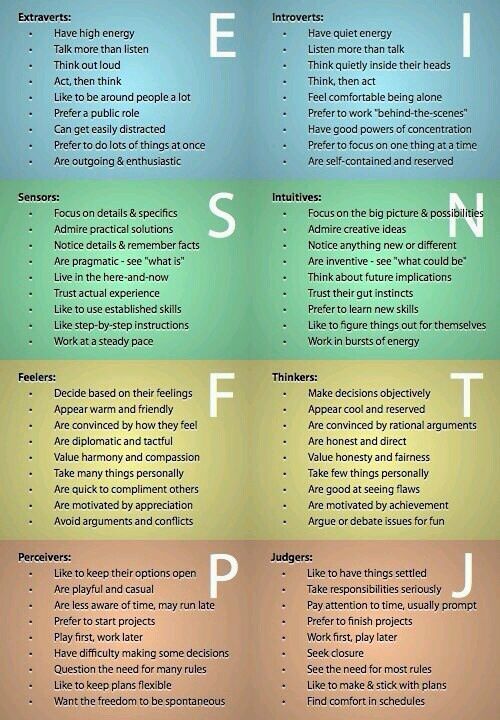

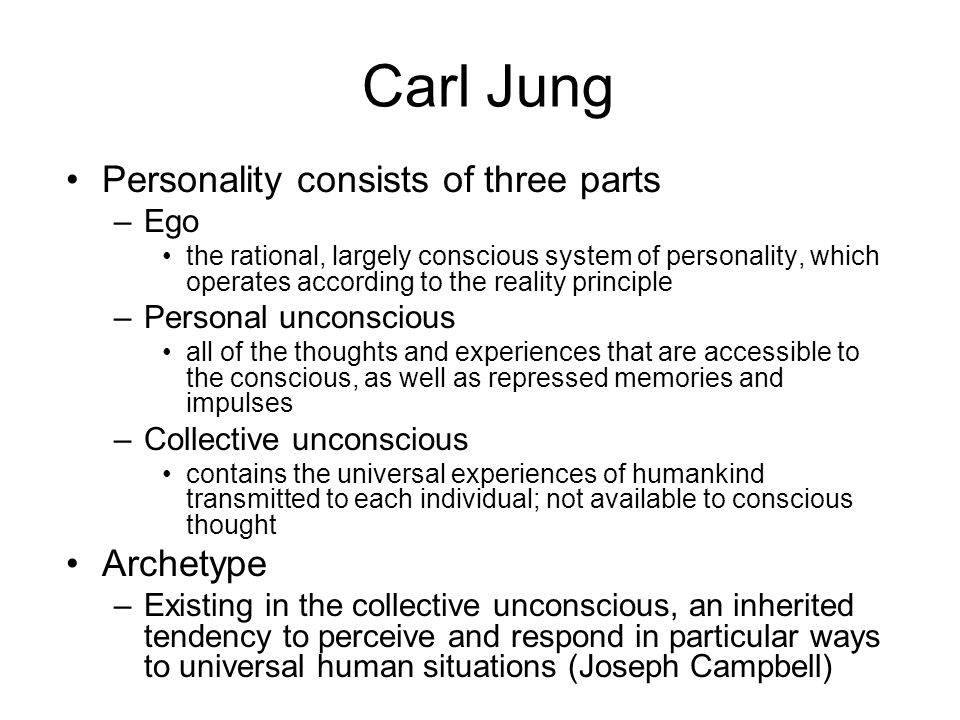

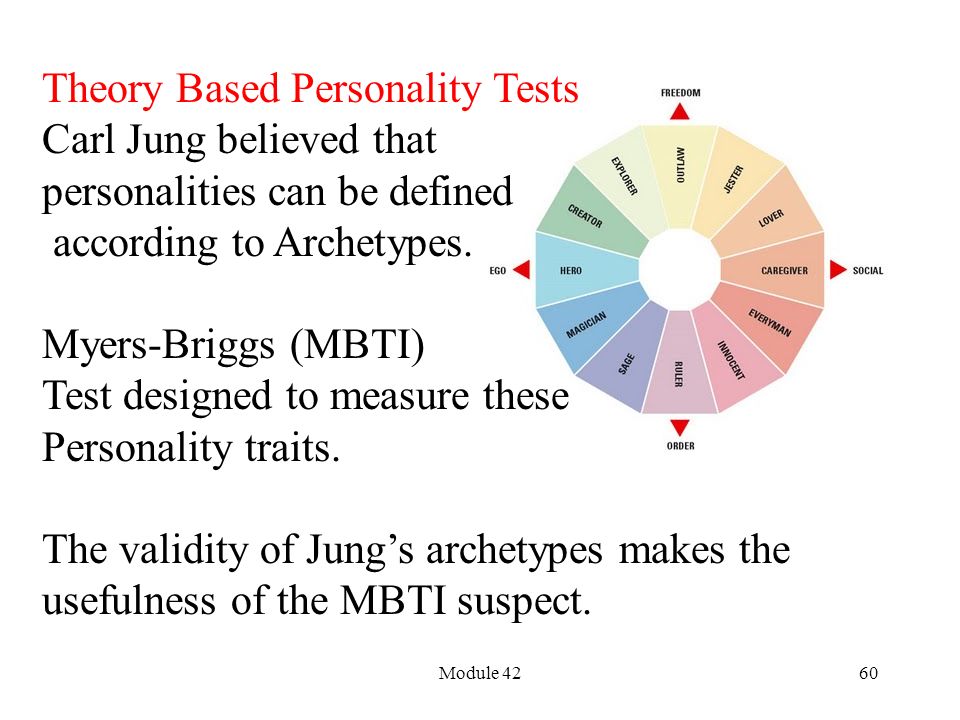

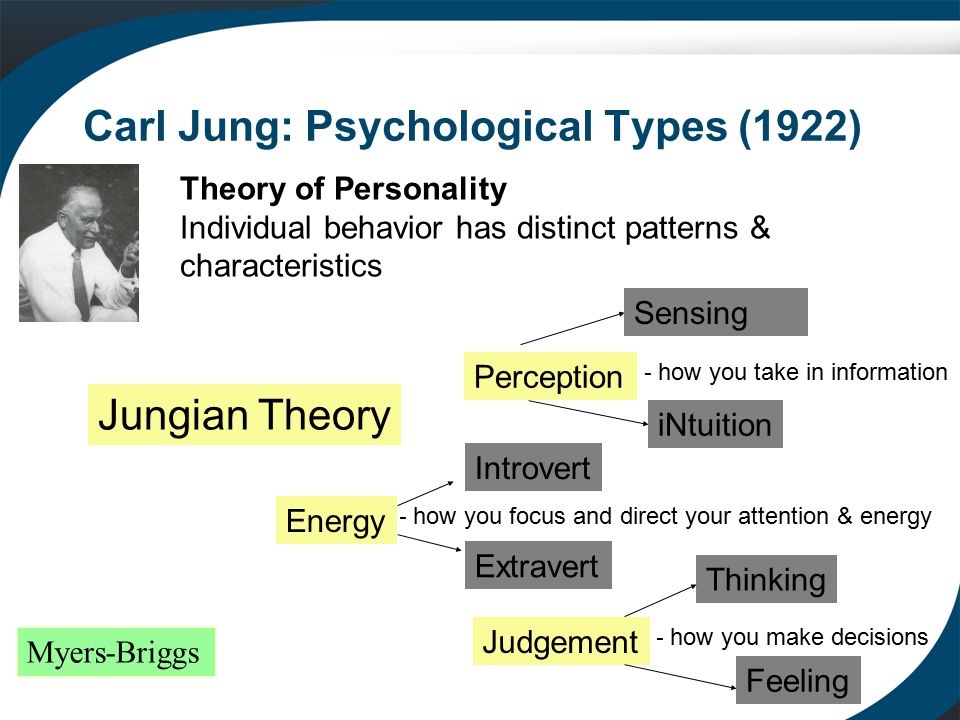

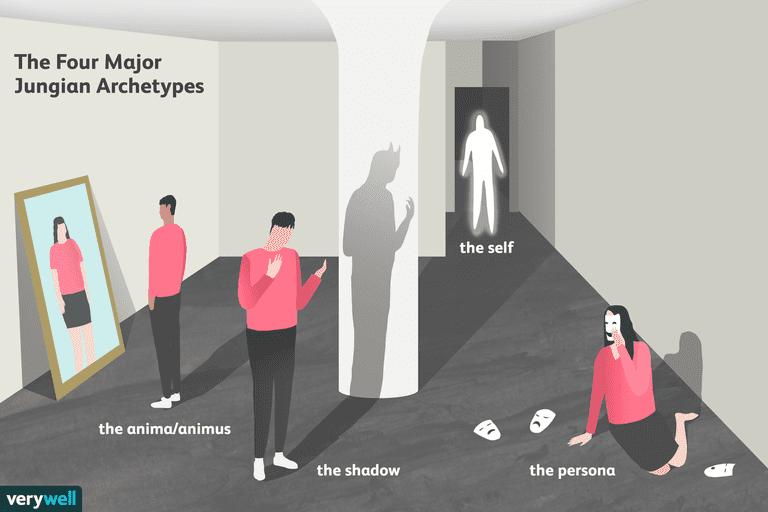

Jung's contribution to the development of psychology and psychotherapy is invaluable. He developed the doctrine of the collective unconscious, in the images of which (the so-called archetypes) he saw the source of universal human symbolism, including myths and dreams. Introduced the terms "introversion" (immersion in oneself) and "extraversion" (interaction with other people). Jung considered the center of personality to be the "self" - the desire for individuality. Developed a typology of characters depending on the dominant function of the personality. The goal of psychotherapy, according to Jung, is the realization of the individuation of the personality. Influenced cultural studies, comparative religion and mythology. He laid the foundation for the now so popular socionics. Jung does not deny the influence of Freud's sexual and Adlerian power complex, but unlike Freud, he does not reduce everything to one factor.

Initially, Jung was interested in anthropology and Egyptology, he chose to study the natural sciences, and then his eyes turned to medicine. During his studies, he became interested in the study of spiritualism, attended seances several times. Just before his final exams, he "suddenly understood the connection between psychology, or philosophy, and medical science." He immediately decided to specialize in psychiatry.

During his studies, he became interested in the study of spiritualism, attended seances several times. Just before his final exams, he "suddenly understood the connection between psychology, or philosophy, and medical science." He immediately decided to specialize in psychiatry.

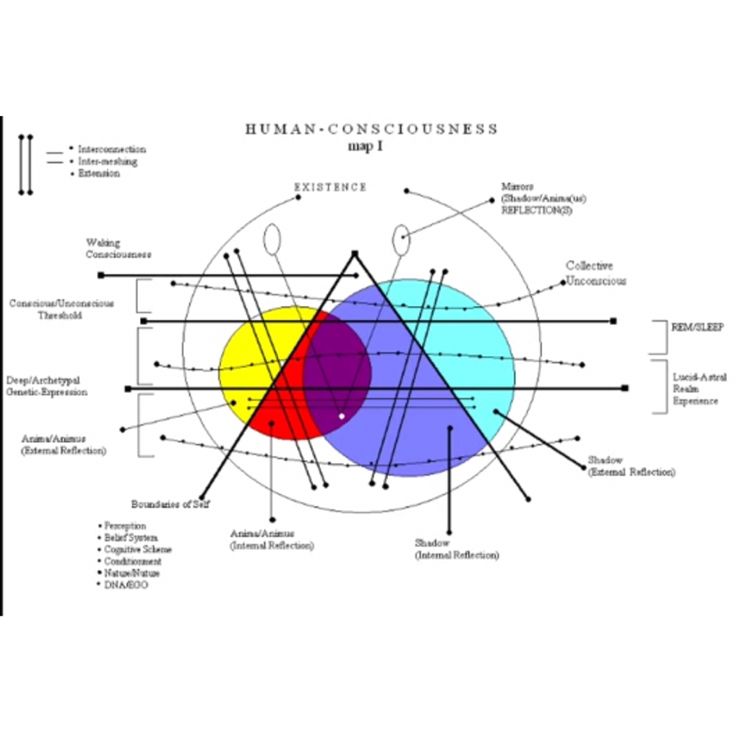

Dreams, myths, religious beliefs are all means of coping with conflicts through wish fulfillment, as psychoanalysis reveals; moreover, they hint at a possible solution to the neurotic dilemma. Jung was not satisfied with the interpretation of dreams as different variations of the Oedipus complex, in which his view differs significantly from Freud, which, by the way, is by no means the only method of psychoanalysis, since such an interpretation did not recognize the creative perspective of dreams. Jung himself repeatedly changed the direction of his life under the influence of his dreams, as if they were prophetic omens. In Jung's memoirs, we learn that the dead come to him, ring the bell and their presence is felt by his whole family. It is no coincidence that Jung developed a technique for communicating with the mystical world, studied trance. He also described the individual (personal) and collective unconscious. The individual unconscious is a powerful component of the human soul. A stable contact between consciousness and the unconscious in the individual psyche is necessary for its integrity. The collective unconscious is common to a group of people and does not depend on the individual experience and experiences of a person. The collective unconscious consists of archetypes (human prototypes) and ideas. The most obvious and complete archetypes can be seen in the images of the heroes of fairy tales, myths, legends. In addition, each person in his own experience can meet with archetypes in the images of dreams. Jung believed that there is a certain inherited structure of the psyche, developed over hundreds of thousands of years, that makes us experience and realize our life experience in a very specific way. And this certainty is expressed in what Jung called archetypes that influence our thoughts, feelings, actions.

It is no coincidence that Jung developed a technique for communicating with the mystical world, studied trance. He also described the individual (personal) and collective unconscious. The individual unconscious is a powerful component of the human soul. A stable contact between consciousness and the unconscious in the individual psyche is necessary for its integrity. The collective unconscious is common to a group of people and does not depend on the individual experience and experiences of a person. The collective unconscious consists of archetypes (human prototypes) and ideas. The most obvious and complete archetypes can be seen in the images of the heroes of fairy tales, myths, legends. In addition, each person in his own experience can meet with archetypes in the images of dreams. Jung believed that there is a certain inherited structure of the psyche, developed over hundreds of thousands of years, that makes us experience and realize our life experience in a very specific way. And this certainty is expressed in what Jung called archetypes that influence our thoughts, feelings, actions. By the way, Jin Shinoda Bolen wrote about archetypes interestingly and efficiently in the book “Goddesses in Every Woman”, she is a follower of Jungian psychology.

By the way, Jin Shinoda Bolen wrote about archetypes interestingly and efficiently in the book “Goddesses in Every Woman”, she is a follower of Jungian psychology.

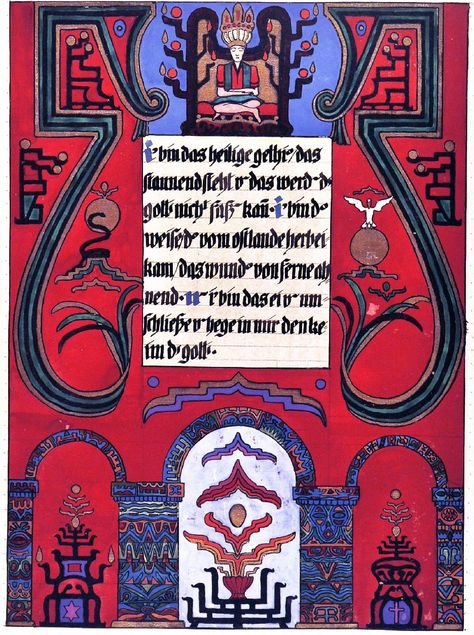

In one of his later works, Carl Jung proposed a number of psychotherapeutic techniques that can be applied in clinical settings. In particular, his method of "active imagination". The patient is invited to draw or paint any images that spontaneously come to his mind. With the development of a personality, a change in its self, with a change in the image and thoughts, the drawings also change. The patient's desire to convey as accurately as possible the image that appears to him can help him to manifest his unconscious ideas. Jung believed that this technique helps the patient not only in that it gives him the opportunity to express his fantasies, but also allows him to really somehow use them.

Treatment with Jungian methods follows the path of integrating the psychological components of the personality, and not just working through the unconscious, as it is according to Freud. Complexes, according to Jung, bring not only nightmares, erroneous actions, forgetting the necessary information, but are also conductors of creativity. Therefore, they can be combined through art therapy (“active imagination”) - a kind of joint activity between a person and his traits that are incompatible with his consciousness in other forms of activity.

Complexes, according to Jung, bring not only nightmares, erroneous actions, forgetting the necessary information, but are also conductors of creativity. Therefore, they can be combined through art therapy (“active imagination”) - a kind of joint activity between a person and his traits that are incompatible with his consciousness in other forms of activity.

In 1922, Jung bought a manor in Bollingen and built the so-called Tower there for many years. Having at the initial stage the appearance of a primitive round stone dwelling, after completion the Tower acquired the appearance of a small castle with two towers, an office, a fenced yard and a pier for boats. In his memoirs, Jung described the building process as an exploration of the structure of the psyche embodied in stone.

According to Jung, the ultimate goal in life is the full realization of the Self , that is, the formation of a single, unique and integral individual. The development of each person in this direction is unique, it continues throughout life and includes a process called individuation. However, not only Jung wrote about this. Almost everyone who did not reach into the abyss of the dark study of psychoanalysis saw in the individual the ability to develop and grow, overcoming certain crises and neuroses. Even existentialism views a person through the prism of his crises and choices, but the choice for life, because a person is always not complete.

However, not only Jung wrote about this. Almost everyone who did not reach into the abyss of the dark study of psychoanalysis saw in the individual the ability to develop and grow, overcoming certain crises and neuroses. Even existentialism views a person through the prism of his crises and choices, but the choice for life, because a person is always not complete.

Everything would be fine, but only I lowered the score because esoteric inclinations, the study of dreams, mythology, alchemy are far from me. Listening to Masha on this issue was much more interesting than thinking about it herself. Probably, for the first time in my life it is - that someone's story is more valuable than their own thoughts on the issue. I am not very interested in magic, and Jung can be considered not only as a psychiatrist, but also as a Magician. I was not at all close to his turn towards magic, higher phenomena, astrology, extrasensory perception, psychic abilities. I had the opportunity to retreat to a magical life while reading, but it's not like that. Jung's understanding of magic separated him from Freud and even from those Jungian rationalists who were embarrassed by his esotericism. From the first moment I read Jung, I saw that he was trying to go two ways and make his psychology both rationalistic and esoteric. On the basis of this particular book, I would conclude that he belongs to the esoteric inclination.

Jung's understanding of magic separated him from Freud and even from those Jungian rationalists who were embarrassed by his esotericism. From the first moment I read Jung, I saw that he was trying to go two ways and make his psychology both rationalistic and esoteric. On the basis of this particular book, I would conclude that he belongs to the esoteric inclination.

Something I did not understand Jung, as I understand and love other philosophers and psychologists. Maybe this is just not my direction, because from the same Alfred Adler I had a clear concept of striving for excellence, the teachings of Karen Horney gave more than a hundred other books gave, the teachings of Freud laid the foundation for all study. I used to worry that I take something of my own from every psychologist, psychiatrist and philosopher, but I don’t have a clear concept and a single preference ( maybe I just lean a little more towards existentialism and have a special love for Karen Horney ). At that moment, it seemed to me that I needed to have a clear idea, although now I understand that science does not stand still, and every contribution of any psychologist is now reflected in the soul of people through the interconnection of all components. But now I realized that Jung is still somewhat not my teaching, and I can take from him only psychological types that gave rise to socionics.

At that moment, it seemed to me that I needed to have a clear idea, although now I understand that science does not stand still, and every contribution of any psychologist is now reflected in the soul of people through the interconnection of all components. But now I realized that Jung is still somewhat not my teaching, and I can take from him only psychological types that gave rise to socionics.

Thank you, Masha the_unforgiven , for this tip in flash mob 2014 ! I needed him :) For you need to have different opinions and you need to know more.

Listening to you was a great pleasure.

Combined with non-fiction and book-Eurovision (Switzerland).

Carl Jung's theory of dreams | is... What is Carl Jung's Theory of Dreams?

Carl Gustav Jung did not share the concept of Sigmund Freud, outlined in the treatise "The Interpretation of Dreams", that dreams are a "cipher" encoding forbidden impulses of sexual desire, a representation of unfulfilled desires, considering such a view to be simplistic and naive. In fact, the dream, Jung wrote, is "a direct manifestation of the unconscious" and only "ignorance of its language prevents us from understanding its message."

In fact, the dream, Jung wrote, is "a direct manifestation of the unconscious" and only "ignorance of its language prevents us from understanding its message."

In order to interpret dreams, unlike Freud, Jung urged the dreamer not to "run away into free association", but to focus on the specific image of the dream and give it as many analogies as possible. Jung believed that the method of free associations allows revealing only the dreamer's personal (individual) associations, grouped around complexes (which Jung proved experimentally) [1] , but does not allow one to get closer to the meaning of the dream itself.

According to Jung, the dream field of meaning is much broader than these individual limits and reflects the richness and complexity of the entire realm of the unconscious, both individual and collective. One of Jung's ideas is that the soul, as a self-regulating organism, compensates for the setting of consciousness with the opposite unconscious setting. [2] Therefore, mythology can provide assistance in the interpretation of a dream, since dreams speak the mythological language of symbols that unite opposite attitudes into integral semantic categories. Only a lack of understanding of the symbolic language puts the interpreter in the position of "a Frenchman who, once on the streets of London, is convinced that everyone around him is mocking him or trying to hide something."

[2] Therefore, mythology can provide assistance in the interpretation of a dream, since dreams speak the mythological language of symbols that unite opposite attitudes into integral semantic categories. Only a lack of understanding of the symbolic language puts the interpreter in the position of "a Frenchman who, once on the streets of London, is convinced that everyone around him is mocking him or trying to hide something."

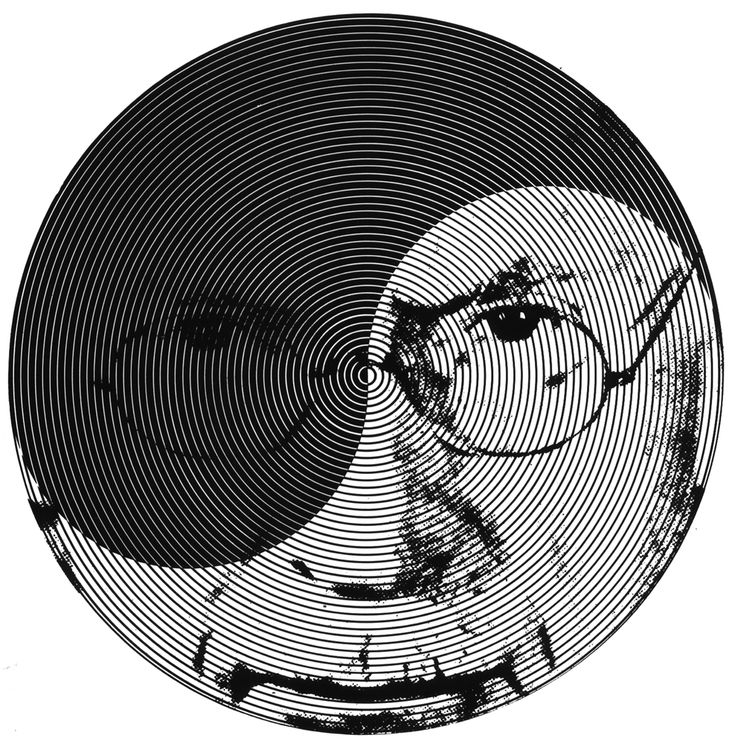

Jung considered the dream as a means to establish a connection between the conscious and the subconscious and saw in the dream the function of compensating for the ego's position. He also emphasized "big" dreams, that is, dreams associated with a numinous feeling of delight and horror. In these dreams, Jung saw the highest spiritual guidance that comes from the center of human (and possibly all) being - the Self.

Jung developed two main approaches to the analysis of dream material: objective and subjective. [3] In an objective approach, each dream character refers to a real person: a mother is a mother, a girlfriend is a girlfriend, and so on. In a subjective approach, each dream character represents an aspect of the dreamer himself. Jung believed that although it may be difficult for the dreamer at first to take a subjective approach, but in the process of working on a dream, he will be able to identify his own traits and previously unknown aspects of his personality in the characters of the dream. So, for example, if a person dreams that he is attacked by a mad killer, then the dreamer may become aware of his murderous impulses. This approach has been extended by Gestalt therapists: they believe that even inanimate objects in a dream can be seen as embodiments of aspects of the dreamer's personality.

In a subjective approach, each dream character represents an aspect of the dreamer himself. Jung believed that although it may be difficult for the dreamer at first to take a subjective approach, but in the process of working on a dream, he will be able to identify his own traits and previously unknown aspects of his personality in the characters of the dream. So, for example, if a person dreams that he is attacked by a mad killer, then the dreamer may become aware of his murderous impulses. This approach has been extended by Gestalt therapists: they believe that even inanimate objects in a dream can be seen as embodiments of aspects of the dreamer's personality.

Jung believed that archetypes (animus, anima, shadow, etc.) manifest themselves in dreams through symbols or characters. This may be an old man, a young girl or a huge spider involved in the plot. Everyone embodies an unconscious attitude, mostly hidden from consciousness. Even as an integral part of the dreamer's psyche, they often exist autonomously and are perceived by the dreamer as external figures. Acquaintance with the archetypes, manifested in the symbols of dreams, allows a person to become more aware of his unconscious attitudes, integrate previously split off parts of the personality and be included in the process of a holistic understanding of his Self, which Jung considered the main task of analytical work [2] .

Acquaintance with the archetypes, manifested in the symbols of dreams, allows a person to become more aware of his unconscious attitudes, integrate previously split off parts of the personality and be included in the process of a holistic understanding of his Self, which Jung considered the main task of analytical work [2] .

Jung believed that the material repressed by consciousness (to which Freud reduced unconscious contents in general) is similar to what in his conception is called the Shadow, and constitutes only a certain part of the unconscious.

Jung warned against blindly ascribing certain meanings to dream symbols without a clear understanding of the dreamer's personal situation. He described two approaches to dream symbols: the causal approach and the finalist approach. [4] In the causal approach, the symbol is reduced to certain basic tendencies. Thus, the sword can symbolize the penis, the snake - too. In the finalist approach, the dream interpreter asks: "Why this particular symbol and not another?" The sword can then represent the penis in terms of its qualities: it is hard, sharp, inanimate, and destructive. And the snake, representing the penis, indicates other qualities: something alive, dangerous, possibly poisonous and slippery. The finalistic approach reveals additional nuances of the meaning of the setting in which the dreamer finds himself.

And the snake, representing the penis, indicates other qualities: something alive, dangerous, possibly poisonous and slippery. The finalistic approach reveals additional nuances of the meaning of the setting in which the dreamer finds himself.

With regard to the technique of working with dreams, Jung recommended analyzing each detail of the dream separately, and then revealing the essence of the dream for the dreamer. This approach is an adaptation of the procedure described by Wilhelm Stekel, who advised thinking about a dream like an article in a newspaper and coming up with a headline for it. [5] Harry Stack Sullivan also describes similar "sleep distillation" processes. [6]

Although Jung insisted on the universality of archetypal symbols, his point of view is the opposite of understanding the sign - an image that has a uniquely defined meaning. His approach was to recognize the dynamics and fluidity that exists between a symbol and its meaning. Symbols should be explored as sources of individual meaning for patients, rather than being reduced to predetermined concepts. This will prevent the dream interpreter from slipping into theoretical and dogmatic exercises that take the process away from the patient's psychological state. In support of this idea, he emphasized that it is very important to "stick to the dream" - to reveal the depth of its meaning through the client's associations with a separate image. This approach is completely opposite to Freud's free associations, leading away from the features of the image. He described, for example, the image of a "wooden table". Perhaps the dreamer would have found some associations with this image, or, on the contrary, there would have been no personal meanings (which would have aroused suspicions about the special significance of the image). Jung, on the other hand, asks the patient to imagine this image as vividly as possible and talk about it as if the interlocutor had never seen wooden tables.

Symbols should be explored as sources of individual meaning for patients, rather than being reduced to predetermined concepts. This will prevent the dream interpreter from slipping into theoretical and dogmatic exercises that take the process away from the patient's psychological state. In support of this idea, he emphasized that it is very important to "stick to the dream" - to reveal the depth of its meaning through the client's associations with a separate image. This approach is completely opposite to Freud's free associations, leading away from the features of the image. He described, for example, the image of a "wooden table". Perhaps the dreamer would have found some associations with this image, or, on the contrary, there would have been no personal meanings (which would have aroused suspicions about the special significance of the image). Jung, on the other hand, asks the patient to imagine this image as vividly as possible and talk about it as if the interlocutor had never seen wooden tables.

Jung stressed the importance of context in understanding a dream. He believed that the dream should not be understood simply as a complex riddle invented by the unconscious, which must be deciphered in order to reveal the causal factors behind it. Dreams cannot serve as lie detectors that would reveal the dishonesty of the conscious attitude. Dreams, like the unconscious itself, speak their own language. Being representations of the unconscious, dream images are self-sufficient and have their own logic. Jung believed that dreams could contain important messages, philosophical ideas, illusions, wild fantasies, memories, plans, irrational experiences, and even telepathic insights. [7]

The conscious or “daytime” life of the soul is complemented by the unconscious, “nightly” side, which we perceive as a fantasy. Jung believed that despite the obvious importance of our conscious life, the importance of the unconscious life in dreams should not be underestimated.