Critique and criticism

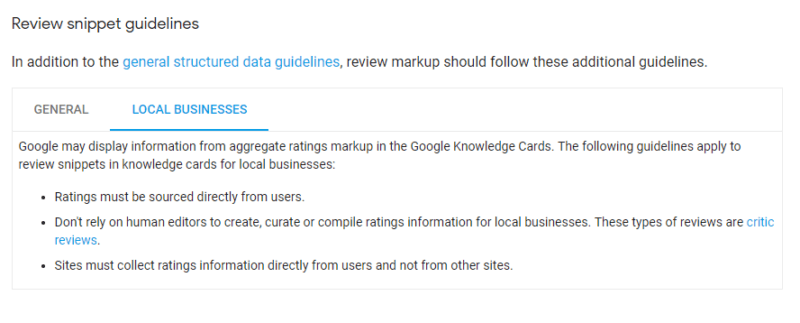

Difference between criticize, criticism, critique, critic, and critical – Espresso English

Hello students! Today I want to teach you about the confusing words criticize, criticism, critique, critic, and critical. These are all similar and they come from the same roots, but they have different functions and some slightly different meanings.

The English language has a lot of words like this – words that are very similar, but actually different – and you can learn a lot more of them in my e-book, 600+ Confusing English Words Explained.

CriticizeOK, let’s start with the word criticize. If you criticize something, you are identifying its faults or negative aspects. So if you say that a restaurant has bad food and slow service, you are criticizing it, you’re stating the bad things about it.

Criticize is a verb referring to the action of identifying faults. The noun form is criticism, referring to the statement or expression of faults. So you might say, “She criticized the restaurant. Her main criticism was about the poor quality of the food.” Note the pronunciation difference between criticize – it ends with the ize sound like in size – and criticism – it has the is sound like in his.

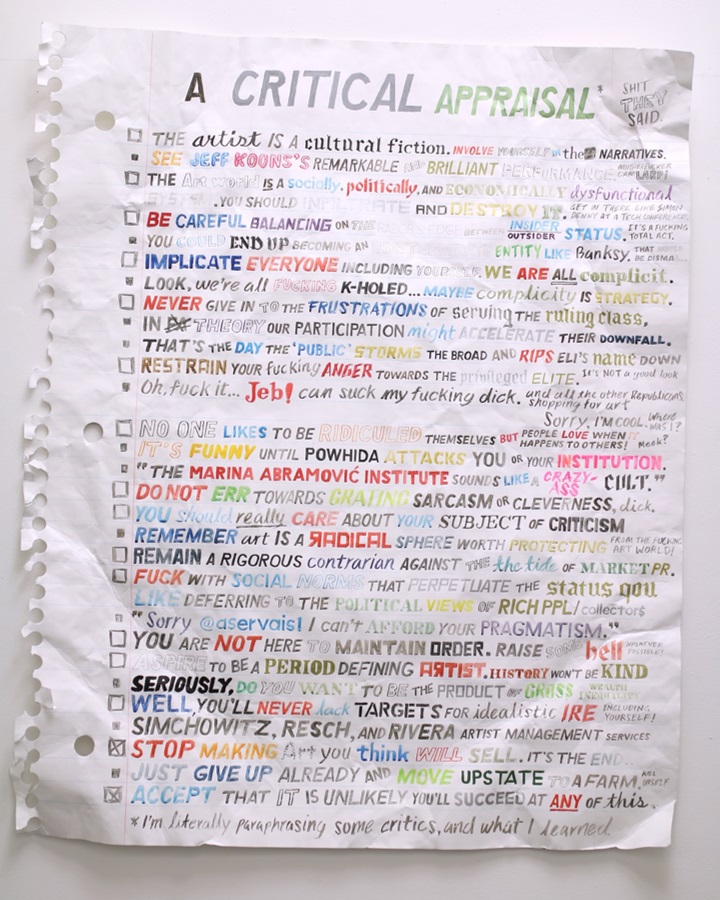

CritiqueNow let’s look at the word critique – this word can be a verb or a noun, and it refers to evaluating and analyzing something, identifying both its good points and its bad points. So when you criticize something you just say negative things, but when you critique something you can say both positive things and negative things. We often critique books, art, movies… the judges on talent shows like cooking shows or singing shows will critique the performance of the cooks or singers.

We often critique books, art, movies… the judges on talent shows like cooking shows or singing shows will critique the performance of the cooks or singers.

Note the pronunciation differences: we had CRI-ti-cize, CRI-ti-ci-sm, and cri-TIQUE has the stress on the second syllable, plus the ee sound as in weak.

CriticWhat about the word critic? This has the stress on the first syllable: CRI-tic. A critic is a person who judges or evaluates something. The people who write movie reviews are called movie critics. People who are critics perform the action of critiquing things (remember, critique means to identify both positive and negative aspects), but sometimes the word critic is also used to describe a person who only says negative things, a person who criticizes. There’s a saying, “Everyone’s a critic” – we often say this when people are criticizing (saying negative things about) something, even people who don’t really have much knowledge about the area.

And finally we have the word critical, which is an adjective, and it has two meanings. When you say a person is critical of something, it means the person is finding fault. For example, my boss is very critical of my work, he’s always making changes and corrections to it. But when you say a thing is critical, it means the thing is essential, it is necessary, it is very important. For example, honesty is critical to a good relationship.

ReviewSo let’s review these confusing words:

- criticize – a verb meaning to identify negative things;

- criticism – a noun referring to the statement of negative things;

- critique – a verb/noun referring to evaluating and identifying positive and negative points;

- critic – a person who judges or evaluates, and sometimes a person who only finds negative points;

- critical – two meanings: a person who tends to find fault, or a thing that is very important or essential

I know these words are complicated, but I hope I’ve helped make them a little clearer. For more lessons like this, I’d highly encourage you to get my e-book which will teach you more than 600 confusing English words.

For more lessons like this, I’d highly encourage you to get my e-book which will teach you more than 600 confusing English words.

Critique versus Criticize | MLA Style Center

Advice from the Editors

by Michael Kandel

Claire Kehrwald Cook, in her Line by Line, noted that critique as a verb “has not yet won full acceptance.” That was more than thirty years ago, and nowadays a great many scholarly writers use critique as a verb routinely and without blinking. But Cook also observed, though in passing, that the meaning of critique, “to give a critical examination of,” differs from that of criticize or review (174).

The difference is important. Merriam-Webster defines the noun critique as “a careful judgment in which you give your opinion about the good and bad parts of something (such as a piece of writing or a work of art)” but points out its overlap with criticism:

The overlap notwithstanding, here is a reasonable example of why maintaining a distinction matters: On the one hand, “The ballet instructor critiqued the dancer’s pirouette” could mean that the ballet dancer performed an excellent pirouette but that the teacher gave the dancer pointers to make it dazzling. On the other hand, “The reviewer criticized the dancer’s pirouette” means that the reviewer regarded the dancer’s performance unfavorably.

On the other hand, “The reviewer criticized the dancer’s pirouette” means that the reviewer regarded the dancer’s performance unfavorably.

The formal prose required in scholarly writing can make writers hesitant to use simple, down-to-earth words, lest their authority appear questionable. But the preference for critique in academic writing often erases the valuable difference between the two words.

Works Cited

Cook, Claire Kehrwald. Line by Line: How to Improve Your Own Writing. Houghton Mifflin, 1985.

“Critique, N.” Merriam-Webster.com, 2016, www.merriam-Webster.com/dictionary/critique.

Filed Under: usage, word choice, writing tips

Michael Kandel

Michael Kandel edited publications at the MLA for twenty-one years. He also translated several Polish writers, among them Stanisław Lem, Andrzej Stasiuk, Marek Huberath, and Paweł Huelle, and edited, for Harcourt Brace, several American writers, among them Jonathan Lethem, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Morrow, and Patricia Anthony.

He also translated several Polish writers, among them Stanisław Lem, Andrzej Stasiuk, Marek Huberath, and Paweł Huelle, and edited, for Harcourt Brace, several American writers, among them Jonathan Lethem, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Morrow, and Patricia Anthony.

Published 17 October 2016

Criticism is criticism! - Questions of Literature

Critics have been written about more and more often in recent years. The Literaturnaya Gazeta, for example, opened a special column, "An Autographed Portrait," from time to time devoting entire pages to a conversation about the creative individuality of one or another prominent critic. Yes, and in other publications, literary portraits of the masters of our workshop, and detailed, analytical reviews or polemical notes on the margins of monographic works and collections of newspaper and magazine articles, are no longer a rarity.

What is the reason?

First of all, with the growing role of criticism as an organizer of the literary process in the country. The idea of criticism as literature, as an important, socially significant kind of creative activity, has been rooted in us for a long time, but it seems that the question of the responsibility of the literary - critical word - the word not only about books, but also about the time embodied in books - with especially acute and relevant today, when the processes of social development have accelerated sharply, there has been an intensification of creative principles in all spheres of life.

The idea of criticism as literature, as an important, socially significant kind of creative activity, has been rooted in us for a long time, but it seems that the question of the responsibility of the literary - critical word - the word not only about books, but also about the time embodied in books - with especially acute and relevant today, when the processes of social development have accelerated sharply, there has been an intensification of creative principles in all spheres of life.

There is every reason to believe that under these conditions, interest in criticism, which focuses public attention on the essential problems of modernity and contemporary literature, will constantly increase. That is why, it seems to us, the time has come to understand the current literary-critical economy, to try to see behind the general laws the living faces of critics who are actively working today, to understand what exactly is the strength of each of them and what, perhaps, their weakness.

Our conversation now is about four such critics, whose speeches in periodicals have more than once become an occasion for lively disputes, often determined the course of newspaper and magazine discussions, provoked and continue to cause the most contradictory opinions, but have not yet received any detailed assessment 1 .

Their names - Lev Anninsky, Igor Zolotussky, Vadim Kozhinov, Evgeny Sidorov - along with some others, are well known to everyone who more or less closely follows the movement of multinational Soviet literature and the literary thought of our days, seeks to understand the logic of the interaction of art and life, the artist and his audience, current creative initiatives and the classical heritage.

Each of the critics named here, as readers know, is distinguished by the breadth, multidimensionality of creative and research interests, has a taste for understanding topical issues of the history and theory of literature, with more or less activity turns to the experience of theater, cinema, television, music in his work , fine arts. But - "one cannot grasp the immensity", and, remembering, for example, E. Sidorov's attention to the methodological problems of the theory and practice of socialist realism, V. Kozhinov's own literary works, the work of I. Zolotussky and A. Anninsky on the study of Russian classics of the XIX century, the author still focuses primarily on what we call "current criticism", on books, articles, polemical speeches, one way or another connected with the latest phenomena and trends in the modern literary process.

But - "one cannot grasp the immensity", and, remembering, for example, E. Sidorov's attention to the methodological problems of the theory and practice of socialist realism, V. Kozhinov's own literary works, the work of I. Zolotussky and A. Anninsky on the study of Russian classics of the XIX century, the author still focuses primarily on what we call "current criticism", on books, articles, polemical speeches, one way or another connected with the latest phenomena and trends in the modern literary process.

Critics I. Zolotussky, E. Sidorov, L. Anninsky, V. Kozhinov appear here primarily as critics of modern literature. Too narrow? I don't think. Firstly, these writers, in my perhaps controversial opinion, most fully realized their potential, their ideological, aesthetic, moral and psychological attitudes when referring specifically to the literary "topic of the day", to what directly excites the mass readership. Secondly, the author, who is seriously engaged today in “current” prose, poetry, dramaturgy, journalism, inevitably puts all his knowledge, all his analytical tools into action, striving - at least ideally - to consider the domestic literary novelty in its broadest sense. ramified links with the classical past, with the processes now taking place in world culture, and above all in the culture of the socialist countries.

ramified links with the classical past, with the processes now taking place in world culture, and above all in the culture of the socialist countries.

Thirdly, and this is perhaps the most important thing, any qualified, significant statement of a critic about modern literature is perceived by us as a statement about modern life, about the course of changes in social life and consciousness. Such is the one and a half century tradition of Russian critical thought, and it is not for nothing that, speaking of the current multi-profile work of our workshop, of the sometimes striking dissimilarity in views and assessments, we invariably single out its powerful journalistic, socio-civil, educational charge and pathos as a common feature and sign of criticism.

It is possible, without the risk of falling into exaggeration, to say that the activities of modern criticism - with all the difference, and sometimes the polarity of methods, individual manners and "handwriting", despite the fact that there may be excessive love for the "prejudice of one's own be a delusion, is built in this sense on a fundamentally unified methodological platform.

Whatever the dispute is about - about mastering the classical traditions or about the image of a "business man", about the fate of rural prose or about the dynamic interaction of internationalist and patriotic principles in our literature, about the problems of the scientific and technological revolution or about the education of a reliable creative change, – the thoughts of the arguing in one way or another rush to the key issues that are now moving to the forefront in the public agenda with special energy: what to do? what is happening to us? who is guilty? where to begin? isn't it the beginning of change?..

Modern criticism in its most mature, original manifestations hopes to peer into reality through the magnifying glass of literature, to carry out its own “judgment” on it, to help shape public opinion and social ideals.

Does it always work? Alas, not always. And already in order to understand the reasons for both the miscalculations and the achievements of the current critical thought, it is useful, I think, to talk about the work of such dissimilar writers as E. Sidorov, L. Anninsky, V. Kozhinov and I. Zolotussky. By the way, it is worth noting that they all belong to the same generation, in principle, the initial time of which fell on the Great Patriotic War, and the civil and creative formation coincided with the turn of the 50s and 60s. The generation is one, but, as the reader will see, these critics drew different conclusions from our common spiritual, moral, literary experience, sometimes sharply contrasting, contradicting each other, and sometimes charged with internal contradictions.

Sidorov, L. Anninsky, V. Kozhinov and I. Zolotussky. By the way, it is worth noting that they all belong to the same generation, in principle, the initial time of which fell on the Great Patriotic War, and the civil and creative formation coincided with the turn of the 50s and 60s. The generation is one, but, as the reader will see, these critics drew different conclusions from our common spiritual, moral, literary experience, sometimes sharply contrasting, contradicting each other, and sometimes charged with internal contradictions.

Why is that?

Let's not rush, however, and start a conversation.

So…

LEV ANNINSKY, OR “FINALLY SAY WHAT THE TRUTH IS…”

Thinking about modern criticism, you think first of all about Lev Anninsky. There is a tantalizing riddle in his fate, in his word and glory.

First, let's talk about something easier, more obvious - about fame.

I’m not the only one who noticed: in whatever audience you ask about the current critics (who are known, read, who are appreciated? . .), the first name of Anninsky will be called - if, however, at least one current name is remembered at all ... So it is in the literary environment: no matter who makes up the next “troika”, “five”, “ten” of the best literary critics of this day, Anninsky’s name will be pronounced with certainty - almost regardless of whether Anninsky ever wrote about this writer and what exactly wrote.

.), the first name of Anninsky will be called - if, however, at least one current name is remembered at all ... So it is in the literary environment: no matter who makes up the next “troika”, “five”, “ten” of the best literary critics of this day, Anninsky’s name will be pronounced with certainty - almost regardless of whether Anninsky ever wrote about this writer and what exactly wrote.

Why is that? What took (takes) Lev Anninsky?

Talent, the gift of writing?

The answer is good, correct, but insufficient; talent is an unmeasurable thing. rarely uncontested by contemporaries; and who doesn’t know that you can’t live in Russian literature with talent alone ... During the initial ten years of his work in criticism, Anninsky was indeed one of the first in terms of looseness of style, innate sense of composition and intonation flexibility, in open confession. Now there is no shortage of stylists - not without the formative influence of the same Anninsky, the influence of an example. But Anninsky has not completely disappeared in this galaxy, although, in fairness, let's say that his articles - by the standards of pure writing and pure confession - now do not contrast so much with the general literary-critical background, as it happened before.

But Anninsky has not completely disappeared in this galaxy, although, in fairness, let's say that his articles - by the standards of pure writing and pure confession - now do not contrast so much with the general literary-critical background, as it happened before.

So what then? Infallibility of judgment, reputation as an arbitrator - is it good taste, is it real truth?

Here, I suppose, Anninsky himself will resist first of all. He never seemed to want to be infallible. He never was. Even a cursory glance at the bibliographic cards will reveal how often the critic has been mistaken - either pinning his hopes on trends that never took off, or speaking very disapprovingly of really great writers or completely ignoring them. Be a good fellow is not a reproach, this is understandable. But let's take a list of the names of contemporaries about whom Anninsky "specially" did not write (mentions do not count), and whom we will find there: A. Akhmatov, A. Tvardovsky, V. Semin, B. Pasternak, V. Rasputin, V. Grossman, Ya. Smelyakov, A. Tarkovsky, L. Martynov, V. Belov, F. Abramov, V. Kaverin, F. Iskander, Yu. Kazakov, V. Astafiev ... - that is, almost half of the glory and pride of modern literature . The list is impressive, and the very possibility of it suggests that, in any case, the history of post-war prose and poetry cannot be studied “according to Anninsky”.

Pasternak, V. Rasputin, V. Grossman, Ya. Smelyakov, A. Tarkovsky, L. Martynov, V. Belov, F. Abramov, V. Kaverin, F. Iskander, Yu. Kazakov, V. Astafiev ... - that is, almost half of the glory and pride of modern literature . The list is impressive, and the very possibility of it suggests that, in any case, the history of post-war prose and poetry cannot be studied “according to Anninsky”.

So what's the point? I. Zolotussky noted recently that “they know and remember those critics who allowed themselves at least once not to be afraid of someone. Such a critic may then not write (or not be published) for many years, but he will be remembered. And say: this is the one who put that one. Or someone” 2 .

I. Zolotussky is probably right. But what has been said has absolutely nothing to do with Anninsky. He does not have the glory of a fighter against dullness, just as he does not have accusatory power. Negative assessments, of course, happened in his practice, but they were just not remembered - both due to the insignificance of the occasions, and due to the episodic nature, and, most precisely, due to the fact that Anninsky generally does not like to denounce, “put” anyone whatever it was.

He likes to argue.

“Dispute is the norm,” he said “in the middle of the sixties,” both in confirmation of the lived part of his literary biography, and as parting words to himself for the coming decades.

He was drawn to polemics even when the controversy of literary critical judgment was understood as something suspicious. And then, when, again, not without the efforts of Anninsky, she moved into a different, much more flattering synonymous series - closer to words and phrases like "search", "creative courage", "induces co-thinking" and so on. He loves to argue even now, when almost no one is arguing with him, and the debatability of his new provisions, which has become a custom, among most colleagues causes something like a lovingly condescending smile: Anninsky, of course, again sprinkles with paradoxes, but how is he all the same mil…

I have no doubt that this good-natured indulgence will hurt Anninsky no less than the thunder and lightning of the past. But what to do? Fate cannot be changed, and - “even if you win it, your right, you have to play like that” ... And it is probably no coincidence that he stitches one of his relatively recent articles with doubt: “... You won’t suddenly decide what is more worthy: to win someone else’s game or lose one's own" - in order, however, to push himself to the final answer: "It's ridiculous to win someone else's game. It is better to lose - but your own. Started. Got to you" 3 .

But what to do? Fate cannot be changed, and - “even if you win it, your right, you have to play like that” ... And it is probably no coincidence that he stitches one of his relatively recent articles with doubt: “... You won’t suddenly decide what is more worthy: to win someone else’s game or lose one's own" - in order, however, to push himself to the final answer: "It's ridiculous to win someone else's game. It is better to lose - but your own. Started. Got to you" 3 .

Where, however, did this inclination towards thoughts of loss, even if only hypothetical, suddenly arise? After all, the “party” seems to have been won, and most convincingly!..

Won?..

after all, he has been in print for a good quarter of a century, appealing to a dispute in order to achieve “wide popularity in narrow circles” or simply to “respond” to certain literary events. Especially since you can't mark out the real hierarchy of artistic values “according to Anninsky”. His choice is usually not based on the degree of literary significance of the author and work, but on a completely different basis. At times it even seems that Anninsky almost doesn't care which book to write about; it is possible that he could write an article full of literary-critical brilliance about the inkwell or about Zhekov's fattening. It is not for nothing that he, by his own admission, prefers to all the available means of professional "text analysis" the "technique of intercepting the topic", that is, in other words, the technique of replacing the author's problematic with his own, "Anna's". It is not for nothing that they read his articles not in order to better understand the book about which the critic starts talking, but in order to better understand Anninsky himself.

At times it even seems that Anninsky almost doesn't care which book to write about; it is possible that he could write an article full of literary-critical brilliance about the inkwell or about Zhekov's fattening. It is not for nothing that he, by his own admission, prefers to all the available means of professional "text analysis" the "technique of intercepting the topic", that is, in other words, the technique of replacing the author's problematic with his own, "Anna's". It is not for nothing that they read his articles not in order to better understand the book about which the critic starts talking, but in order to better understand Anninsky himself.

It doesn't matter, whatever he writes about, he writes about his own.

About what?

About the moral self-sufficiency of one, separately taken person in the vortex currents of the modern world. About the fate of the individual. About the spiritual climate, the socio-moral situation and the “soil” that have become the conditions for existence for this very individual, “for the “harvest” depends not only on seeds, but also on the soil. Children are more like their time than their parents."

Children are more like their time than their parents."

“Here it is, the pivot: to weigh the fate of the individual…” 4

Here it is, the most important task: to "understand yourself" - and thereby get closer to understanding everyone.

Here it is, the question of Lev Anninsky's questions: "Where is the way for the individual, if he wants to keep in touch with the whole?" 5

Aesthetics really does not fit into these coordinates, It is optional, it can be sacrificed - in relation to ethics, with the basic semantic "oppositions": personality - and time, private - and general, fractional - and holistic.

Here, as the reader sees, there is a lot in common with the circle of ideas and questions that formed that generation of critics, to which56 years old”, belongs to Lev Anninsky. But the differences are also significant - it was they that determined Anninsky's literary and civil independence, made him in our criticism something like a "cat that walks by itself. "

"

Anninsky was initially journalistic on an internal assignment, like M. Shcheglov, like V. Lakshin, like F. Kuznetsov, like Yu. Seleznev. The lessons of revolutionary-democratic criticism, with its appeal to personal activity and responsibility, with its verification of literature by life, with its technique of intercepting a theme and concentrating socially significant principles in the analyzed text, did not pass unnoticed. Another question is how he used them.

A took advantage of this: turned his eyes with pupils into the soul; those rich means by which society was usually studied, turned to the comprehension of the individual, his "soul" and his "role". In other words: if we take the traditional metaphor - a tree, then Anninsky's attention from the very beginning was attracted by individual leaves, while his comrades in the generation and profession took up some of the trunk, some of the roots, some of the crown. Moreover, if they, peers, knew and asserted their knowledge of what literature should be, what a person and society are called to become, then he, Anninsky, asked, doubted the answer and was not ashamed to ask again and again . ..

..

Anninsky's evolution since 1956 (the date of the first publications) naturally proceeded in the same direction as the evolution of modern critical thought in general. But she walked out of the flow (“... It is even her interest

: to go out of the flow”), and it turned out that he did not associate himself with any of the literary movements that were unfolding before his eyes. Even with his own generation of “knights of immediate action” (Evg. Yevtushenko, Vl. Firsov and others), with whom he is related both by confession, and inner plasticity, and vivid emotionality, and much more, is the book “The Kernel of a Nut” (1965), which is devoted mainly to the needs of this generation, is not suitable not only for the role of a “manifesto”, but even for the role of a literary-critical analogue of “Wave of the Hand” and “Oz”, “Stop, look around ...” and “In search of joy”.

This lack of connection, of course, frees the hands, and makes estimates independent of the "directional" conjuncture. But it is also risky - great critics (or contenders for this role) in Russia have always come as the affirmers of a new movement, new literary reputations, and it is no coincidence that even in our most recent memory, the name of V. Lakshin highlights the phenomenon of the so-called "New World" prose, the names of A. Makarov and I. Dedkov - literature, born "in the depths of Russia", and the name of V. Kozhinov - "quiet lyrics" of the mid-60s - mid-70s.

But it is also risky - great critics (or contenders for this role) in Russia have always come as the affirmers of a new movement, new literary reputations, and it is no coincidence that even in our most recent memory, the name of V. Lakshin highlights the phenomenon of the so-called "New World" prose, the names of A. Makarov and I. Dedkov - literature, born "in the depths of Russia", and the name of V. Kozhinov - "quiet lyrics" of the mid-60s - mid-70s.

Anninsky's name doesn't highlight anything. He, as said, is not an affirmative at all. He is an inquirer; and why be surprised that in literary opinion the view of him as a "critic-sprinter", as a thinker who does not have "one long thought", as a doctor of the heart, not consumed by "one but fiery passion" is gradually gaining strength ...

The reason seems to be obvious here. While criticism, by united or disunited efforts, takes redoubt after redoubt on the way of affirming the truths and ideals vital to it, Anninsky either lags behind the common front, then jumps forward, or generally goes around the well-defended bastions. A long siege of social and literary prejudices is not according to him, just as exhausting positional battles are not according to him, His method is "attack with style", parachute assaults of autonomous thought; and while our advanced criticism, with a fervor that has not cooled down since the time of Dudintsev and Shcheglov, Pomerantsev and Panova, proves that people are not divided into "small" and "big", into "heroes" and "non-heroes", that each of us is equally worthy before face of literature and history, Anninsky is already shaking:

A long siege of social and literary prejudices is not according to him, just as exhausting positional battles are not according to him, His method is "attack with style", parachute assaults of autonomous thought; and while our advanced criticism, with a fervor that has not cooled down since the time of Dudintsev and Shcheglov, Pomerantsev and Panova, proves that people are not divided into "small" and "big", into "heroes" and "non-heroes", that each of us is equally worthy before face of literature and history, Anninsky is already shaking:

“How to make people equally worthy if they are not born the same and live differently?” 6 , and while criticism (here the efforts of its various detachments are just united) tirelessly repeats: “Forward, to Pushkin!” - Anninsky already doubts: “... There is something pitiful in that cult of Pushkin that began with us ... twenty years ago ... Today, an oath in the name of Pushkin is a kind of self-hypnosis ...” 7 etc. etc.

etc.

In order for a thought to take possession of everyone and everyone, it must really be implanted with methodical planning, and ten or twenty years is really not a time limit. But Anninsky does not address everyone. He appeals to everyone - and only, and in this case, there is no need for a detailed argument. Quite enough is a hint, a phrase thrown in between times, a doubt in the generally accepted, in order to arouse the counter thought of the reader, to give it nourishment. Moreover, Anninsky does not seek to convince the reader. It is enough for him if the reader connects to his, criticism, internal, spiritual problems.

"Where is the way for the individual..."?

There is, of course, a variant of heroism, holy sacrifice, self-denial in the name of a higher Goal, and Anninsky in his articles and books repeatedly and with unfailing reverence explored this form of the moral self-sufficiency of the individual. But, according to the critic, “heroism is connected with the fact that a person, as it were, makes up for the lack of harmony in himself and in the world” 8 , whereas it is important for Anninsky to find harmony - with himself and with the world; the emphasis on heroics implies moral maximalism, intolerance of compromise (any!) as a way to solve a life task, while Anninsky, in his basic - "personal" - attitudes, gravitates towards "moral realism", that is, precisely towards tolerance, that is, precisely towards a reasonable compromise between person and circumstance.

And finally, and this is perhaps the most important thing, a person can show his heroic principles only in an extreme situation, only in an alternative choice between life and death, honor and dishonor, loyalty to an idea and treason, while the reality of our life ( fortunately for us, of course ...) is such that the decisive choice "either - or" either does not arise at all with conscious clarity, or is assembled from countless and, thanks to this countlessness, indistinguishable set of local confrontations and local concessions - "environment", circumstances, fashion , conjuncture, own inertia, own negligence and so on and so forth. “When the country orders to be a hero, anyone becomes a hero in our country,” and Anninsky knows this very well. But he is occupied with something else: how to resist, how to save himself in a bus crush and at a meeting of the local committee, in conflict with a grumpy janitor and in friendship with the “powerful of this world”? ..

In general terms, “Anninsky's problem” (“the problem of everyone”) could be formulated as follows: “Participation of a person in the drama of common life, which he did not write and during which he is not free. A role imposed on a person by a situation. A role that replaces a person. When he no longer understands where the role is and where he himself is” 9 .

A role imposed on a person by a situation. A role that replaces a person. When he no longer understands where the role is and where he himself is” 9 .

But Anninsky, and this is his fundamental originality, does not believe in the possibility of solving anything "in a general way." He would have been glad to find some general regularity, an algorithm suitable for cracking through any of life's problems, he slipped, it happened, on the presentation of one or another "variant of truth" as an ethical and aesthetic constant, he was not averse to being deceived in the hope to fish out an "invariant" in a sea of hypotheses ("I do not renounce illusions - this is also a form of knowledge"). And yet: the “El Dorado of Dreams” has already had the honor of evaporating, and the river of thought, which seemed to be so full-flowing quite recently, has already managed to pass into a delta before the critic’s eyes, to stratify into a myriad of channels, backwaters, estuaries, etc.

What to do? Explore delta. Go to the understanding of the river from understanding each of the channels separately.

This is Anninsky's choice. An “empiricist” by conviction, a “concreteist” in the sense that he fully trusts only concrete knowledge, only “piece” spiritual experience, he seems to be interested in literature only in order to go beyond his own biographical niche, to “lose” at least mentally different versions, to push to the neighbors in life, to offer them a kind of exchange of spiritual experience... 9Any way beyond the line of life practice - to fantasy, myth, "devilry", generally unreality - Anninsky irritates, if not offended - as an attempt to replace the real with imaginary, escape to the empyrean or unleash the plot with the help of "God from the machine". Anninsky, I suspect, is somewhat irritated by poetry as a kind of literary speech: all these euphonies, metaphors, rhymes, tercetes ... he has no time and reluctance to deal with them, as well as with the "gamut of styles" in general; to have time to find out the main thing - the “version of a person”, his spiritual pedigree and biography, path, “truth”.

As for "artistic features", inattention to them is more than compensated by the sharpness of empathy, which is truly rare in our criticism, and, I think, writers like it so much to be "interpreted" by Anninsky, that he, with all his "burning through" through the text, with love to engrave your own drawing on the living flesh of the work, never acts as a third-party expert. Speaking about Shukshin and Ziedonis, Leskov and Fet, the heroes of Lost Home and Exchange, he seems to be writing about himself, about his pain and his choice.

However, why “as if”? He writes really about himself. He argues, if you take it seriously, not with criticism (by no means) and not with writers (perhaps to a certain extent), but personally with himself, Lev Alexandrovich Anninsky: he refutes himself, puts himself to blame, makes fun of himself, and, I believe that it was not for nothing that in answering the questionnaire of the Literary Review he said that he was afraid to "determine the type and face" of his constant interlocutor: "I will bury myself in the mirror. "

"

This sets the level of sincerity and honesty, because why deceive yourself?.. There is only one task: to reveal your "version of a person" and double-check it - in interaction with other versions that do not coincide.

Naturally, what is especially interesting here is not close - "almost your own!" - experience, and the one that is further away is alien; "one's own", and this is understandable, more visible in contrast with "not one's own". And Anninsky writes: about Nikolai Ostrovsky (“How the Steel Was Tempered” by Nikolai Ostrovsky, 1971), about Boris Kornilov, about the poets of the “generation of the fortieth year”, those who will be perceived as the “front-line generation” (“Thirties-seventies”, 1977; "Mikhail Lukonin", 1982).

What is he looking for in them, in "big-headed boys of an unprecedented revolution"? Exactly what, according to the views of the critic, is lacking in modern man. Integrity. Solidity. Moral health. And moral peace.

They were hardly happy, children of the post-revolutionary-pre-war era. But in them, if we recall Pushkin's formula, there was "peace and freedom", bestowed by the Feeling of being called to a historical destiny; and Anninsky, without stint, multiplies characteristics that echo each other: "... Ostrovsky's hero ... is internally monolithic to such an extent that even peers similar to him could not dream of"; “With Pushkin, the idea of the integrity of human existence entered into the consciousness of Kornilov”; “So this is what the war gave Mezhirov: a sense of fusion with the Whole”; “His (Lukonin’s. – S. Ch.) poetry is initially oriented towards the whole…” 10 etc. etc.

But in them, if we recall Pushkin's formula, there was "peace and freedom", bestowed by the Feeling of being called to a historical destiny; and Anninsky, without stint, multiplies characteristics that echo each other: "... Ostrovsky's hero ... is internally monolithic to such an extent that even peers similar to him could not dream of"; “With Pushkin, the idea of the integrity of human existence entered into the consciousness of Kornilov”; “So this is what the war gave Mezhirov: a sense of fusion with the Whole”; “His (Lukonin’s. – S. Ch.) poetry is initially oriented towards the whole…” 10 etc. etc.

Does Anninsky reproach his contemporaries with their dissimilarity to "fathers" and "elder brothers"? No, he doesn't reproach; knows that that "fate was born of a certain historical time." The era, its fundamental properties, gave birth to this one, which, as the critic knows, is even richer in some ways than previous destinies: at least “the endless flowering of shades”, an abundance of modalities instead of the categorical imperative, the possibility of choice.

It is for this thrice-glorified opportunity for moral choice that modern man seems to have paid with the loss of integrity, "betrothal" to the "all-gathering idea." This is what Lev Anninsky thinks, it seems to me, “laying out ... a painful pattern of continuous moral torment over the grid of traditional social relations”, desperately envious of the choice “was made somewhere in the initial stage, and as if not by them, but by their fate” . “... For them,” the critic repeats over and over again, “complete involvement in the structure of the world, in the cause of the world, is a state of mind to such an extent that the question here is not about the fact of duty, but only about the limit of self-giving or, using the well-known poetic metaphor, about the degree of fit of the drive belt in the great working machine of history ... " 11 .

Lev Anninsky's books and articles of recent years, entirely aimed at "weighing the fate of the individual", are, I am convinced, one of the strongest attacks today against individualistic self-indulgence, against the hope for the possibility of personal inner independence and personal moral purity. “Everyone raves about independence… and everyone is furious with this very independence, and how they rush about!” 12 - this quotation alone, and there are many of them from the "late" Anninsky, will, I think, be enough to see in what has been said above is by no means a paradox.

“Everyone raves about independence… and everyone is furious with this very independence, and how they rush about!” 12 - this quotation alone, and there are many of them from the "late" Anninsky, will, I think, be enough to see in what has been said above is by no means a paradox.

Yes, his books and articles of recent years are exactly about this – about the drama and the curse of choice: “How? Where? At what cost? – about how personalities need “ultimate truths and ultimate clarity that does not get bogged down in the accidents of the moment” 3 , about whether a person who is not included in the structure, who has fallen out of a pre-prepared social nest, pre-staged for him, is able to find support roles.

The alternative is absolutely clear for the current Anninsky: either preoccupation with the Whole, the feeling of being an inseparable part of the overall structure, or “spiritual restlessness”, the orphan complex of a well-fed “home” boy, envying the friendly game of kindergarten children under the tutelage of a wise teacher who decides for them . Torn off from the Whole, not accepted into the Whole, a person can run around as much as he likes, reveling in personal moral self-sufficiency, despising "herding", etc. - he, if he is really decent and really honest with himself, has nowhere to escape from the insidious question, on which , as you know, more than one Russian intellectual was breaking down:

Torn off from the Whole, not accepted into the Whole, a person can run around as much as he likes, reveling in personal moral self-sufficiency, despising "herding", etc. - he, if he is really decent and really honest with himself, has nowhere to escape from the insidious question, on which , as you know, more than one Russian intellectual was breaking down:

Are you well with yourself, my friend? “And to understand another? This is where everything comes to a close”…

- Perhaps it is not superfluous to recall that this article continues a kind of cycle of works on critics of modern literature, begun by sketches of Al. Mikhailov (“New World”, 1982, N 1), Vl. Gusev (“Literary newspaper”, April 11, 1984), V. Kamyanov (“Literary review”, 1985, N 9). [↩]

- “Literary study”, 1981, N 6, p. 94. [↩]

- "Contacts", M., 1982, p. 88. [↩]

- Literary Review, 1981, N 7, p. 93. [↩]

- "Contacts", p. 185. [↩]

- Literary Review, 1977, N 10, p.

46. [↩]

46. [↩] - Literary Review, 1983, N 4, p. 26.[↩]

- "Thirties - seventies", M., 1977, p. 123. [↩]

- Literary Review, 1981, N 11, p. 50. [↩]

- "Thirties - seventies", p. 29, 108, 185, 143. [↩]

- "Thirties - Seventies", p. 127, 126[↩]

- Literaturnaya Gazeta, January 26, 1983 years old. 8 "Thirties - Seventies", p. 30.[↩]

Would you like to continue reading? Subscribe for full access to the archive.

Already subscribed? Log in to access the full text.

Criticism: what is it, how to properly criticize and perceive criticism

. We deal with psychologistsUpdated on October 28, 2022, 09:48

shutterstock

From the point of view of human development, criticism is an important element of communication that allows us to see and correct our mistakes, and therefore become better. However, almost no one likes to be criticized. The reason is that the line between good and bad criticism is very thin, it is quite easy to cross it. Often this is due to excessive emotions or personal dislike. But sometimes even the value judgments of others without any negative connotation can hurt. How to learn to criticize others correctly and to easily perceive sometimes not the most pleasant opinions from the outside? RBC Life offers an impartial look at the situation through the eyes of psychologists.

Often this is due to excessive emotions or personal dislike. But sometimes even the value judgments of others without any negative connotation can hurt. How to learn to criticize others correctly and to easily perceive sometimes not the most pleasant opinions from the outside? RBC Life offers an impartial look at the situation through the eyes of psychologists.

Content

- What is it

- Types of criticism

- How to perceive

- How to criticize

What is criticism

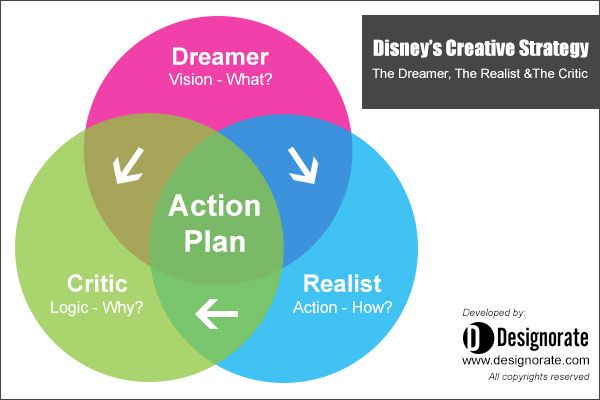

Criticism is a tool that allows you to evaluate and analyze any phenomena from various areas of life. From the point of view of science, criticism is twofold: in its simplest form, it is either good or bad. For example, you can criticize from resentment, in order to hurt the opponent personally, or, conversely, to motivate a person to correct mistakes and improve himself.

Emotional reactions to criticism also differ [1]. Some people are offended, angry and hold a grudge for many years, others easily accept judgments addressed to them or do not notice them at all. The difference in perception depends on many things [2].

The difference in perception depends on many things [2].

- Type of criticism. It can be criticism that inspires or, on the contrary, humiliates and ridicules failures.

- Experience. The more often a person experiences negative emotions, the more painfully he experiences each new episode. For example, if a child had very demanding parents, they may be vulnerable to negative feedback later on.

- Relations. Depending on who criticizes, the reaction to what is said may vary. Mom, spouse, boss or subordinate - criticism from each of them will have its own power.

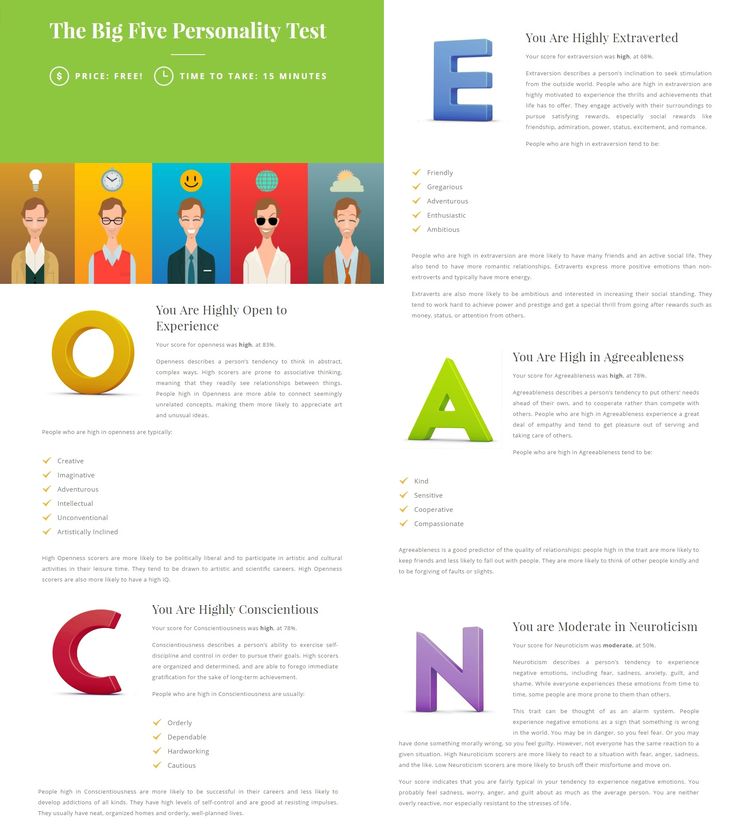

- Individuality. Each person has his own character and psychological characteristics. Self-confident people respond more easily to criticism, but may shift the blame to others. More sensitive and emotional, on the contrary, experience more and tend to judge themselves too harshly in response to what is said. Some people almost do not react to criticism, at the same time, it is important for them to find out why there is an opinion about them and how it can be changed.

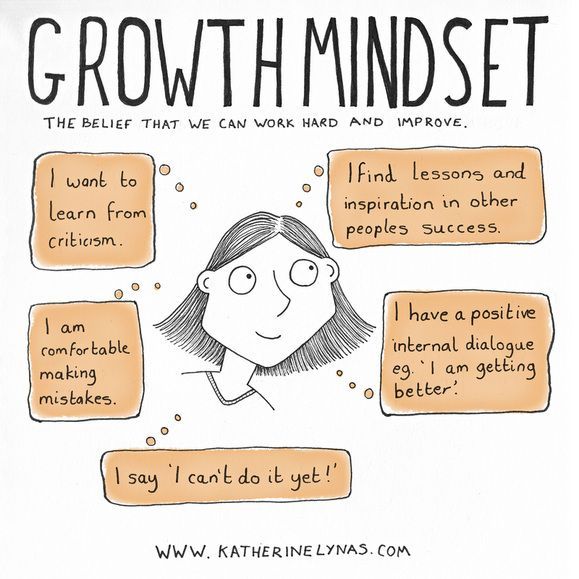

And these are not all factors. Moreover, the same person will perceive criticism differently depending on the context and situation. However, we all need constructive self-correction, and other people can help us with this. For example, the corporate culture actively uses the feedback method. On the one hand, this is the same criticism, that is, a person can be told something unpleasant or point out shortcomings, but there are differences. Feedback is always focused on the desired action, future-oriented, and focused on strengths rather than weaknesses.

Maria RazlogovaClinical psychologist at the Rassvet clinic

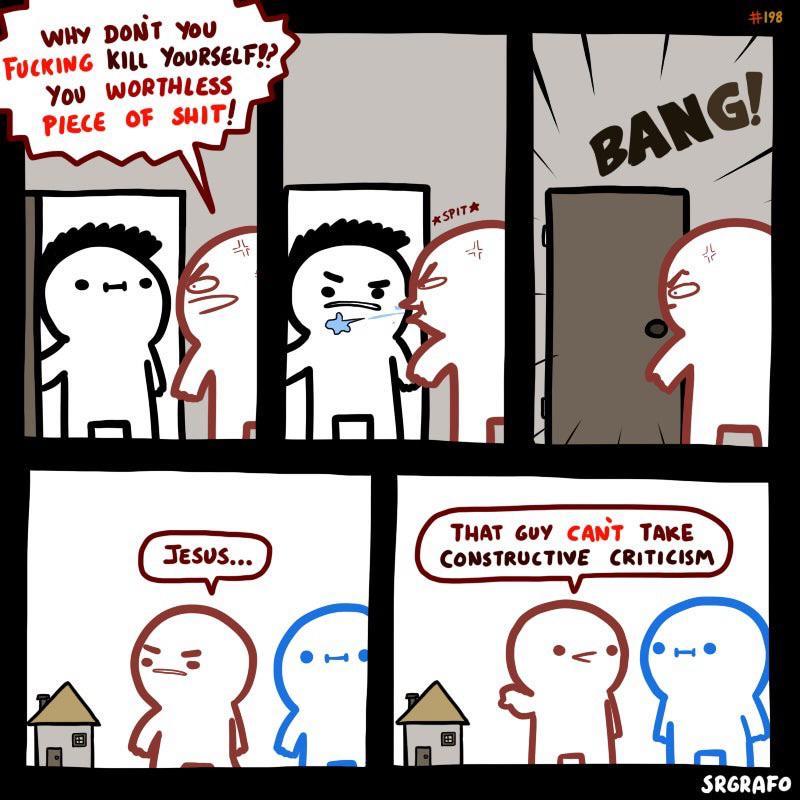

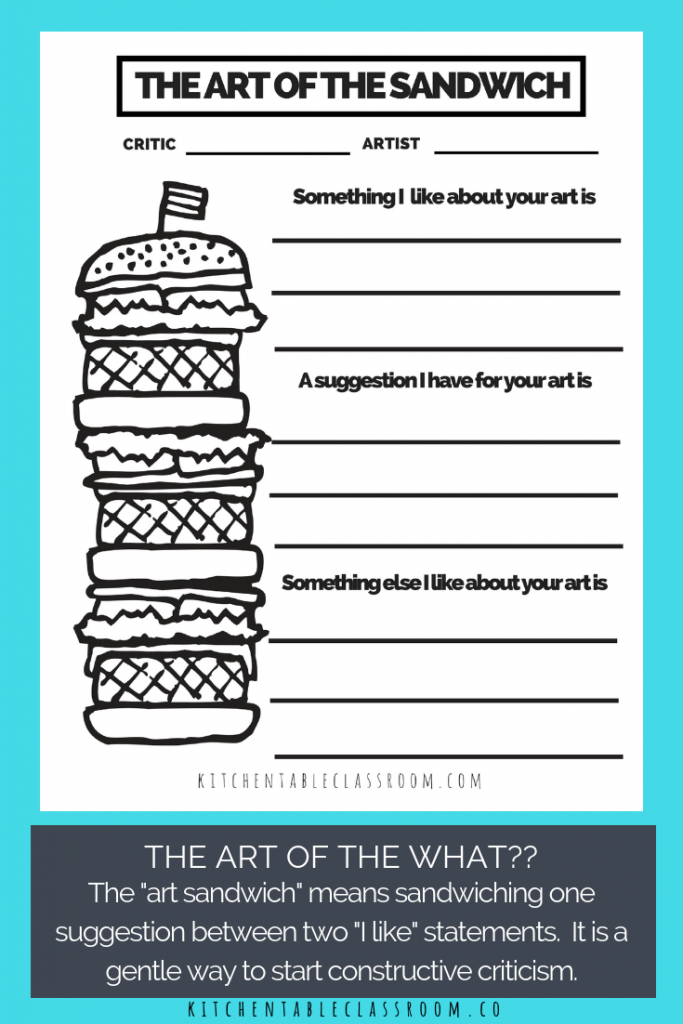

“The problem is that often criticism does not refer to specific behavior - “you are doing it wrong now”, but to the person as a whole - “you are clumsy, lazy, mediocrity ...”. Such assessments do not help, but, on the contrary, reduce motivation. Useful criticism reflects not only mistakes, but also strengths. It is built on the principle of a sandwich: find something to praise - point out the problem - praise again.

Types of criticism

shutterstock

The balance of constructive and destructive criticism is important for a person

Criticism is diverse and largely depends on the angle at which you look at it. According to Elena Fiveyskaya, psychologist and coach at GMS Clinic, criticism can be divided into the following types.

- By impact: beneficial, destructive or mixed, which contains a useful argument, but supported by some misinformation. It is often found in philistine reviews.

- According to the form of presentation: explicit, with an open discussion of the minuses, as well as implicit, with a skeptical assessment.

- According to the form of expression: remark, claim, objection, accusation or dissatisfaction.

- Self-criticism: an inner voice that condemns and compares against you.

In addition, they distinguish factual criticism, moral, aesthetic, logical, religious, liberal and others [3]. But most often you can hear about constructive and destructive criticism. They can both point to flaws and errors, but with important differences.

But most often you can hear about constructive and destructive criticism. They can both point to flaws and errors, but with important differences.

Constructive criticism

Constructive criticism is a way to provide useful feedback. It includes practical suggestions and focuses on a specific issue, rather than assessing the whole situation and the person personally. However, it can contain both positive and negative comments. But in general terms, it will be clear, concrete and effective. In teamwork, constructive criticism can increase motivation, improve work in general, and help achieve results.

The main features of constructive criticism:

- Intention: motivation, helping a person to improve his work.

- Areas: focuses on the shortcomings of the work.

- Action: offers a solution to the problem and suggestions to improve the situation.

An example of constructive criticism: “I noticed that lately mistakes in your work have become frequent. If I've put too much on you, let me know so I can change the load. Glad to talk about it."

If I've put too much on you, let me know so I can change the load. Glad to talk about it."

Destructive criticism

Destructive criticism is a kind of feedback in which the object is not the action, but the person himself. Such judgments, as opposed to constructive ones, do not improve the situation and do not help motivate the interlocutor or subordinate. Often destructive criticism is used to attack in case of personal dislike and is aimed at lowering someone's self-esteem. It is not of practical use and is perceived as excessive pickiness. In a work environment or at home, this is not the best tool to inspire employees or loved ones.

Main features of destructive criticism:

- Intention: to harm, offend, offend.

- Area: is focused on the person, not on his work.

- Action: offers no solution.

An example of destructive criticism: “There are mistakes in your report again. You're just not made for the job."

You're just not made for the job."

Elena FiveyskayaLeading specialist, psychologist, coach GMS Clinic

“If there were only such types of criticism as dissatisfaction or claims, I would be inclined towards the absence of its positive influence on the development of mankind. But if we are talking about such a form as an objection, remark, claim, this is an opportunity for growth. The remark does not sound very pleasant, but noticing an error or inaccuracy is the path to improvement. Through the claim, we can achieve an exchange and improvement of the work as a whole. This allows you to develop social communication skills. But in order to broadcast positive criticism, we need a resource. If it is not there, then it is easy to slip into discontent and accusations.”

How to Handle Criticism Painlessly

shutterstock

Don't rush to respond to criticism right away. Give yourself time to analyze and understand what your interlocutor wants

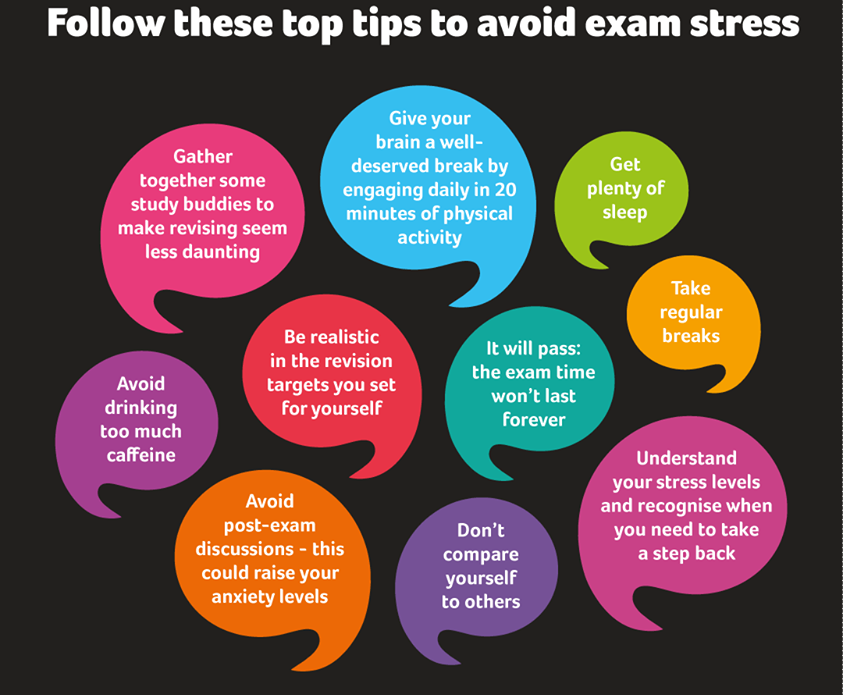

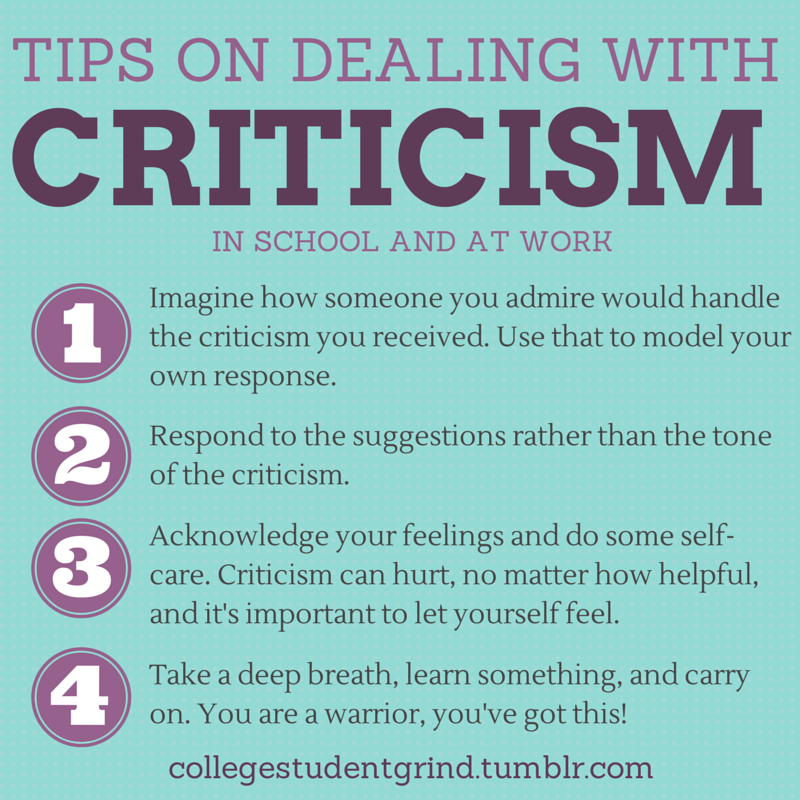

It is impossible to completely avoid criticism from superiors or relatives, but there are ways to take it painlessly and respond correctly to comments. On the advice of psychologist Maria Razlogova, the following recommendations can be followed.

On the advice of psychologist Maria Razlogova, the following recommendations can be followed.

1. Take a break

If you feel hurt by someone's comment, take a break. Mentally count to ten, take a few deep slow breaths and exhalations. It is normal during a personal conversation to ask for a pause from the interlocutor to think about what is happening. If you manage to let go of a spontaneous impulsive reaction, you are already well done.

2. Analyze what was said

When you have calmed down, you can analyze the received message. Remind yourself that this is only an estimate of another person who may be wrong, inaccurate, or generally distort reality to their advantage. Try to separate the wheat from the chaff and mentally formulate what you agree with the interlocutor and what you don’t. Think about the goals of your interlocutor.

Perhaps he did not want to offend you at all, but tried to help, albeit clumsily. If you haven't asked your interlocutor for feedback and received unsolicited advice, ask them not to do that again. If a person wants to help you, it makes sense to do so only with your permission or at your request.

If a person wants to help you, it makes sense to do so only with your permission or at your request.

3. Try to understand the essence and benefit

Perhaps the criticism came from a person who, due to his role in your life, must sometimes criticize you. For example, when it comes to a boss or a teacher. In this case, treat this feedback as a function within a business or study relationship. Try to extract from the criticism the content that can help you and discuss those aspects of it with which you disagree.

4. Don't be afraid to speak

If what you said hurt you, you can tell the other person about it. This will help to regulate your state, because voicing experiences reduces their intensity. In addition, it will help to establish emotional contact and mutual understanding, which can be important when talking with loved ones.

5. Improve yourself

If it is very difficult for you to accept criticism and you experience constant problems in connection with this, it makes sense to discuss this with a psychologist. You may need to learn emotion regulation skills or make changes to your social circle.

You may need to learn emotion regulation skills or make changes to your social circle.

How to properly criticize

shutterstock

Constructive criticism of others and yourself is a skill to learn

Most people tend to perceive personal criticism as something negative, although this is not always the case. It's not easy to criticize without being offended.

On the advice of coach Elena Fiveyskaya, in order for criticism to be as effective as possible, it is worth following some important rules.

1. Listen to yourself

Before criticizing a person, decide what you want: to help another become better or to throw out your negative feelings. In the latter case, according to the expert, it is better to work with yourself and what is behind it - envy, internal dissatisfaction, an attempt to assert yourself.

2. Direct to action

Directing criticism at the person's actions rather than the person's personality: for example, saying not that the person is stupid, but that their work lacks scientific evidence. The most important thing to remember is that constructive criticism should be a dialogue between two people, not a monologue. You don't always know all the details that influenced a person's decisions or actions.

The most important thing to remember is that constructive criticism should be a dialogue between two people, not a monologue. You don't always know all the details that influenced a person's decisions or actions.

3. Show respect

Treat the criticized with respect, from the position of "adult-adult", that is, on an equal footing. Resist the temptation to go into the position of a "parent" (even if it is kind) and do it from top to bottom, for example, in a pointing and instructive tone.

4. Rate feedback

Assess the readiness and desire of the criticized for feedback. If he is not open to discussion, even the most constructive criticism can be unpleasant and affect his mood. In addition, any criticism should be timely. But this does not mean that it is necessary to point out an error at the moment when it has already occurred. Instead, it is about drawing the person's attention to the problem while they still have time to fix or prevent it.

5.