Individuals with night eating syndrome

Night Eating Syndrome - StatPearls

Continuing Education Activity

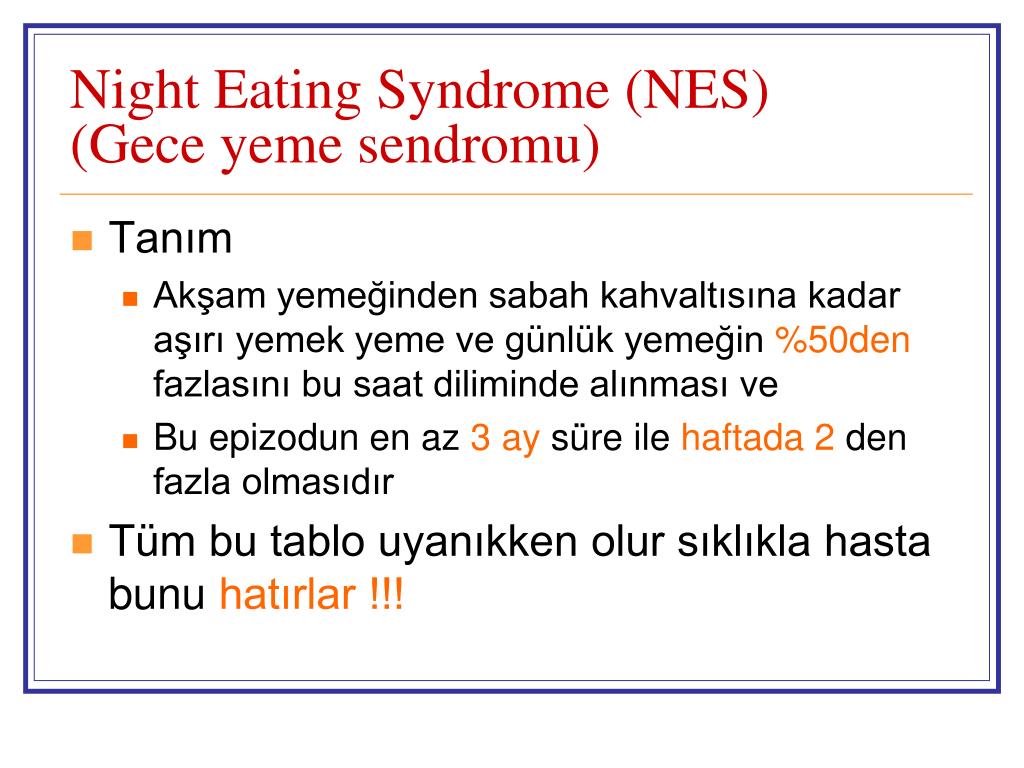

Night eating syndrome is a type of eating disorder that is characterized by hyperphagia in the evening with 25% or more of daily caloric intake after dinner with not less than two nocturnal awakenings during the week to eat food. The prevalence is 1.5% in the general population of the United States. The syndrome is complicated with obesity problems such as diabetes. Patients respond to variable treatment modalities such as SSRI, Light therapy, and progressive muscle relaxation treatment. This activity examines the diagnosis and management of night eating syndrome so that health care practitioners can help patients with this disorder.

Objectives:

Outline the clinical evaluation of night eating syndrome.

Describe the pathophysiology of night eating syndrome.

Review the differential diagnoses of night eating syndrome.

Summarize the appropriate management of night eating syndrome with prognosis.

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Introduction

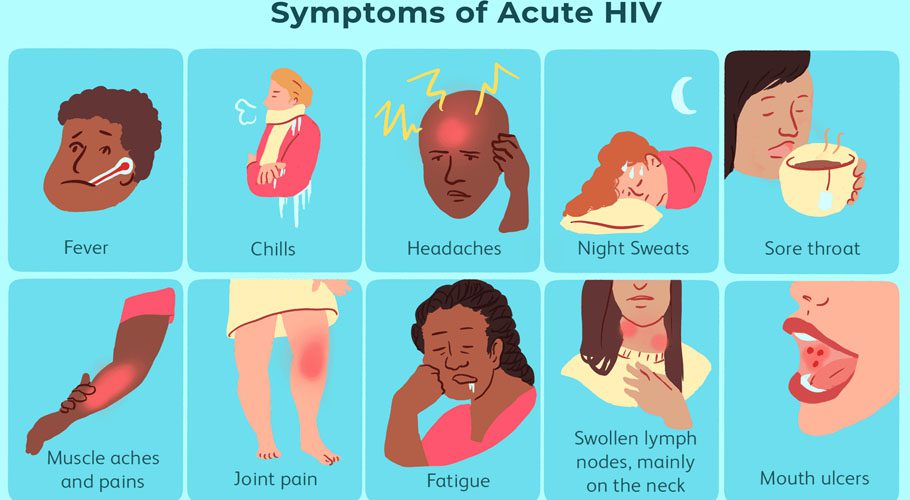

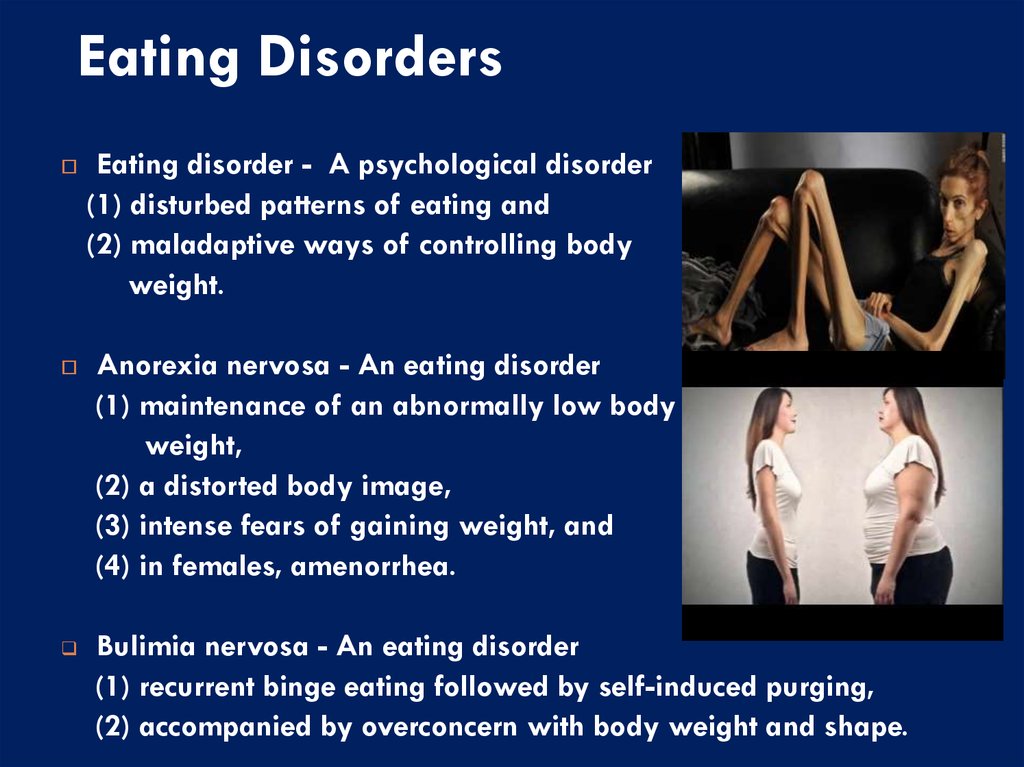

Night eating syndrome (NES) is a type of eating disorder related to eating after dinner and when awake at night. It was first discovered by Wolff, Stunkard, and Grace in a group of patients seeking weight loss treatment.[1] The syndrome was identified when their patients reported consuming a caloric intake of 25% or more at night during the time patients without obesity were not eating.[1] Night eating syndrome is characterized by at least three of the following symptoms: strong urge to eat between dinner and sleep, anorexia in the morning and/or during the night, maintenance or sleep onset insomnia, depressed mood, evening mood worsening, and the belief that one cannot sleep without eating.[2][3]

Etiology

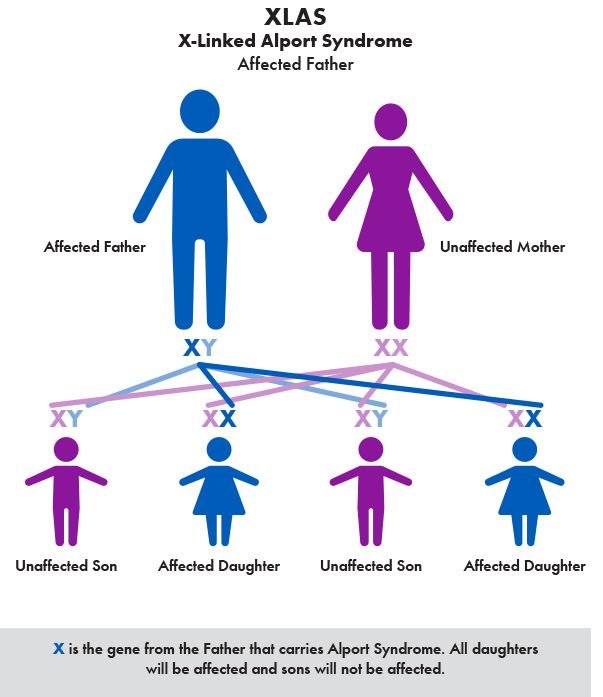

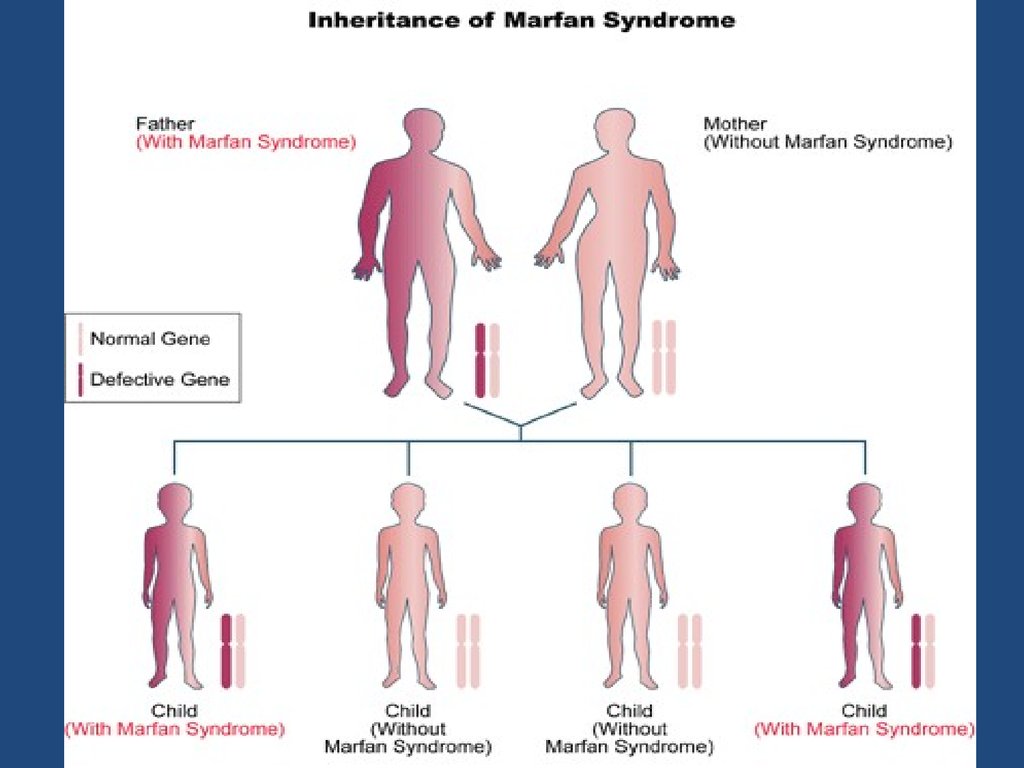

The etiology of night eating syndrome has remained unknown. Recent research has proposed a link between a psychological course, neurological, and/or genetic processes. A study by Lamerz and colleagues conducted on children in Germany showed that patients were more likely to develop night eating syndrome if their mothers had night eating behavior. These patients were compared to children of mothers who did not have night eating behavior.[4]

A study by Lamerz and colleagues conducted on children in Germany showed that patients were more likely to develop night eating syndrome if their mothers had night eating behavior. These patients were compared to children of mothers who did not have night eating behavior.[4]

A recent study compared night eating behaviors in families who had a person with the condition to those families who did not. The results showed that those with NES had first-degree relatives with the disorder more often than the control group suggesting a heritability aspect to the disorder.[5]

Stress can exacerbate the symptoms of the disorder, and symptoms can be alleviated by decreasing stress levels.[1] The initial onset and maintenance of the condition were shown by recent studies to be directly caused by stress and other psychiatric disorders like depression.[6]

Epidemiology

In the United States, the prevalence of night eating syndrome is 1.5%. NES prevalence is similar to other binge eating disorders like bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. [7][8] It is more frequently seen in obese populations, although not all individuals with NES are, in fact, obese.[9][10] A study in Sweden revealed a 2.5 times more prevalence of NES in males with obesity along with a 2.8 times higher prevalence in females with obesity in comparison to non-obese of both genders.[11]

[7][8] It is more frequently seen in obese populations, although not all individuals with NES are, in fact, obese.[9][10] A study in Sweden revealed a 2.5 times more prevalence of NES in males with obesity along with a 2.8 times higher prevalence in females with obesity in comparison to non-obese of both genders.[11]

A prevalence between 6 to 64% of NES was found among obese individuals looking for weight loss surgery in a review conducted by de Zwaan, Mitchell, Burgard, and Schenck. A study showed up to 55% of individuals seeking bariatric surgery have reported some symptoms of NES.[12] NES typically appears in the late teens to late twenties. NES also appears to be long-lasting, with relapse and remission tethered to stressors.[13][14] A Swedish twin registry participant in an interview-based study revealed more women than men who met all criteria for NES.[15] It could suggest that both genders experience NES symptoms equally. However, females are more affected negatively.[15]

Those with night eating syndrome are more likely to have another eating disorder than the rest of the non-NES population, with a 5 to 44% prevalence. [9] Overlapping symptoms between NES and binge eating disorder have been shown as 15 to 20% of patients with NES also were found to have binge eating disorder. However, the conditions are differentiated by the quantity of food eaten per meal, the motivation for eating, and the concern about weight and shape.[16] Patients were recruited into a study by Lundgren from outpatient clinics using the NES screening questionnaire. Patients were asked about their evening food cravings, nocturnal ingestions, morning anorexia, and the sum of awakenings. The criteria for NES were met in 12.3% of the study participants, and it was found that those patients were also obese.[17][18]

[9] Overlapping symptoms between NES and binge eating disorder have been shown as 15 to 20% of patients with NES also were found to have binge eating disorder. However, the conditions are differentiated by the quantity of food eaten per meal, the motivation for eating, and the concern about weight and shape.[16] Patients were recruited into a study by Lundgren from outpatient clinics using the NES screening questionnaire. Patients were asked about their evening food cravings, nocturnal ingestions, morning anorexia, and the sum of awakenings. The criteria for NES were met in 12.3% of the study participants, and it was found that those patients were also obese.[17][18]

Pathophysiology

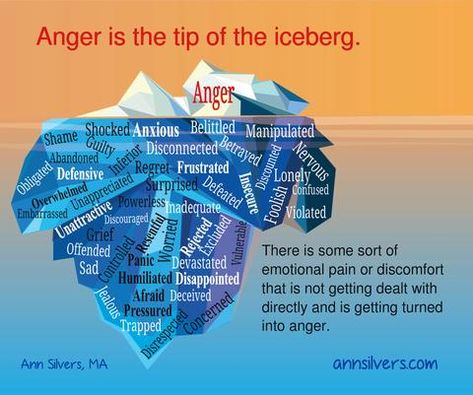

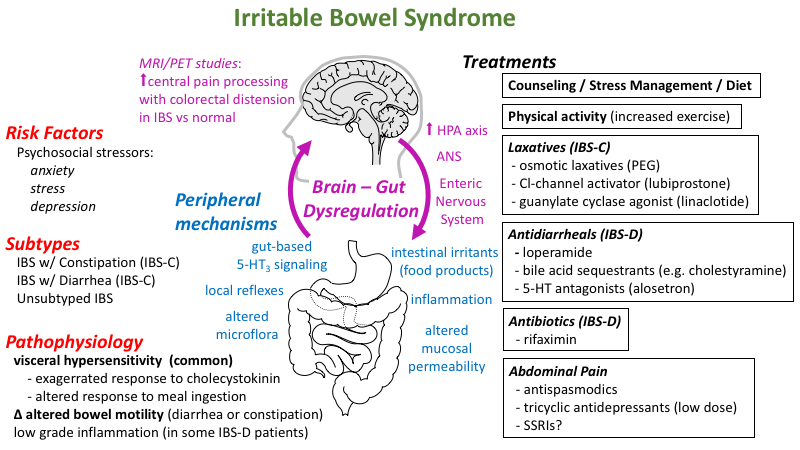

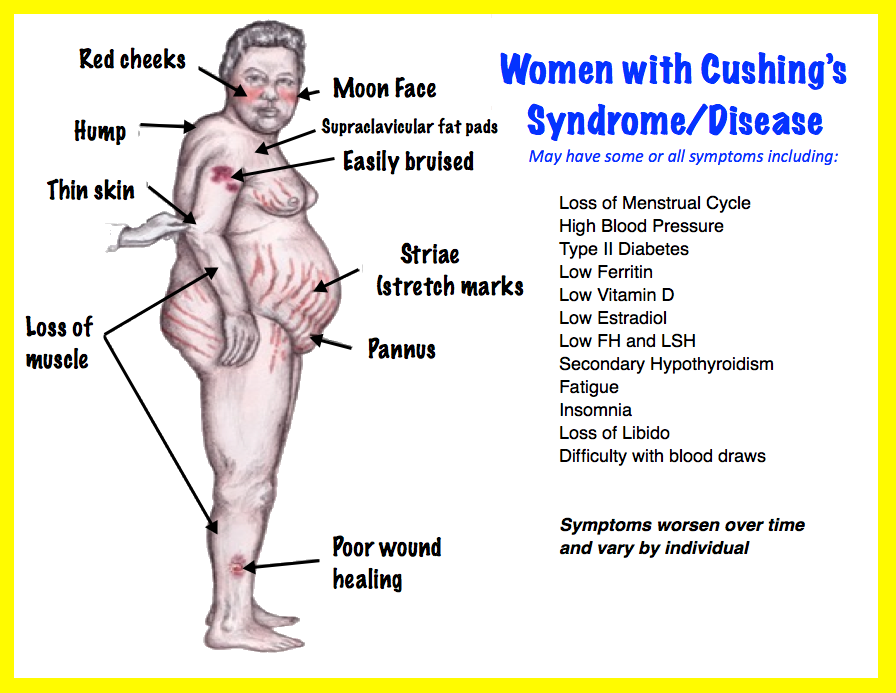

Researchers believe that cognitions and a wide range of emotions might play a major role in having NES. Most symptoms occur at night due to the belief that the individual can not sleep without eating. Patients also will feel a need to control the anxiety associated with that belief through eating. [19][20] Cortisol was examined during night eating as it is the hormone released during stress that is associated with overeating.[21][22]

[19][20] Cortisol was examined during night eating as it is the hormone released during stress that is associated with overeating.[21][22]

A study was done by Birketvedt and colleagues on 33 participants, 12 with NES and 21 control subjects. The subjects were fed regular intervals of meals over a 24-hour period and given no food after 8:00 pm.[23] Blood tests were drawn every 2 hours over the 24-hour period, with the results showing higher cortisol levels from 8:00 AM-2:00 AM in night eaters compared to those in the control group.[23]

History and Physical

Some studies have determined criteria to include hyperphagia in the evening with 25% or more of daily caloric intake after dinner with not less than two nocturnal awakenings during the week to eat food.[23][24][25] Additional criteria include the awareness of nocturnal eating habits and recall of the nocturnal eating habits.[2] A clinical picture is described by three of these criteria:

Breakfast and/or morning eating are missed due to a lack of desire[26]

The urge to eat between the evening meal and bedtime sleep[18][23]

Difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep occurring for four or more nights per week[27]

The belief that the individual must eat to return to sleep

The mood that worsens at night or is frequently depressed[27][28][29]

Evaluation

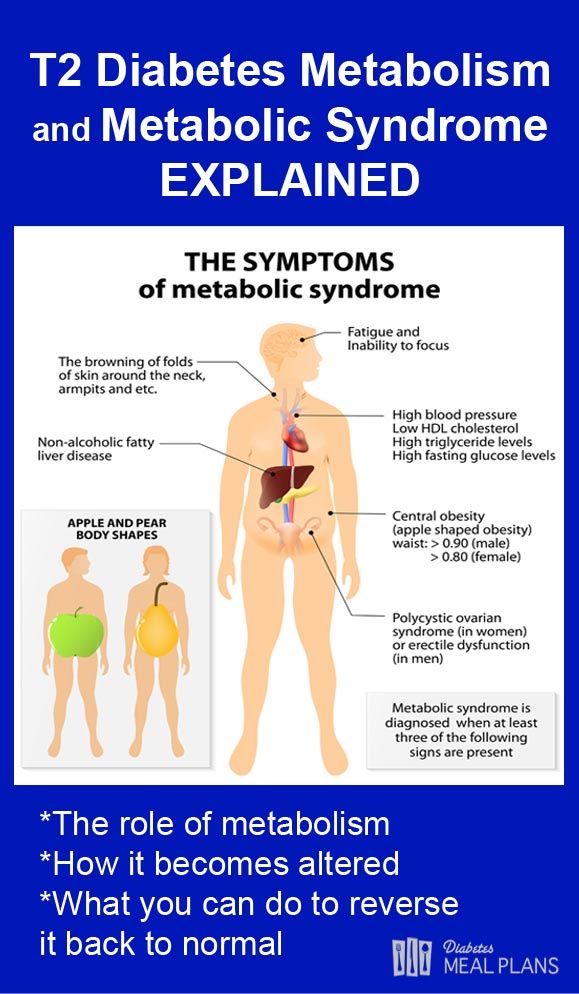

In a randomized control trial done by Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study, the diagnosis of NES was found to be related to more patients with a depressed mood. [30][26][16] The study also showed that diabetic individuals with obesity have higher BMI and reported weight problems at much younger life than those without eating disorders.[31]

[30][26][16] The study also showed that diabetic individuals with obesity have higher BMI and reported weight problems at much younger life than those without eating disorders.[31]

In previous studies, a significant predictor of HbA1c >7 was discovered in individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes that reported evening hyperphagia along with two or more diabetes complications and obesity.[32]

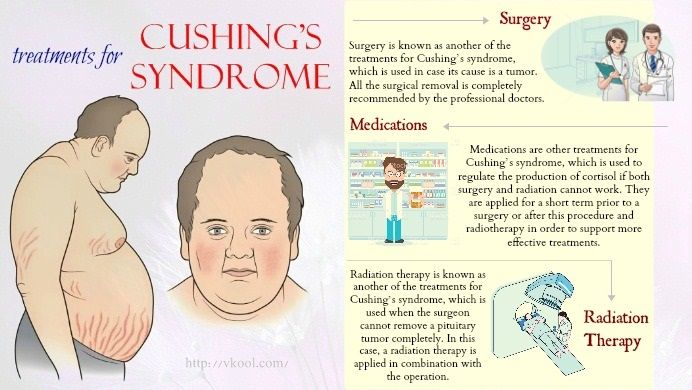

Treatment / Management

Psychotherapy has been shown to decrease night-eating symptoms. Twenty-five patients were treated with cognitive behavioral therapy by Allison and colleagues within 12 weeks of diagnosis.[33] The interventional study included education, logging of sleeping and eating habits, encouraging coping skills, regulating eating and sleep patterns, and weight management.[6][33] The study results showed reductions in weight gain, evening caloric intake, nocturnal ingestions, and recurrent awakenings at night. Treatment also showed improvements in mood enhancement and quality of life.

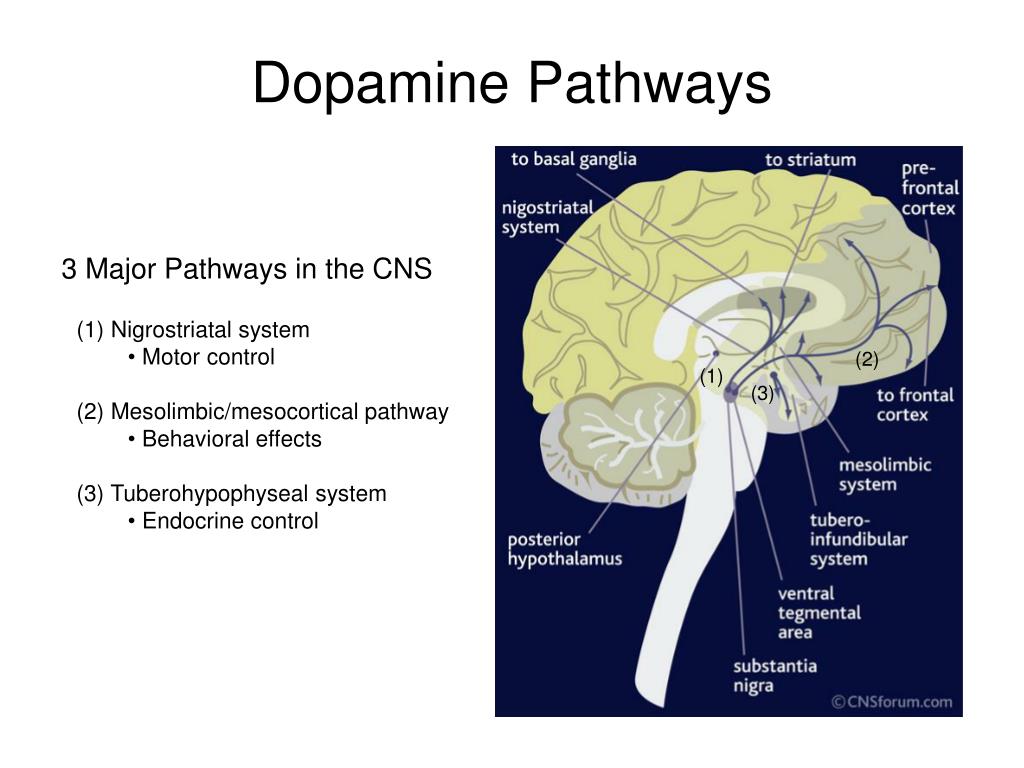

The serotonin system contributes to the regulation of eating, mood, and sleep. Therefore, it was assumed that reduced serotonin could lead to reduced satiety and circadian rhythm disturbances leading to an increased level of evening hyperphagia and nocturnal ingestions.[34] In a 12-week clinical trial study on 17 patients treated with sertraline, along with two additional studies that included randomized controlled trials, the results showed a massive reduction in night awakenings, evening hyperphagia, and calorie consumption after evening meals.[35][25]

The rate for remission was 29%. However, the response rate was 67%.[35] Open-label trial testing escitalopram efficacy revealed a significant reduction in NES symptoms, caloric intake consumed after dinner, and nocturnal ingestions; however, no difference was noticed in comparison to placebo in a randomized controlled trial.[36][37][35]

In a randomized study on 44 patients from both genders divided into three groups: education, education plus Progressive muscle relaxation PMR or PMR plus exercise, Vander Wal and colleagues concluded there was the percentage of food eaten was significantly different between the three groups of study with the group doing PMR having the greatest reduction. [38] The increase of postsynaptic serotonin has been proven using phototherapy. Two case studies used phototherapy to treat symptoms of NES and depression.[39]

[38] The increase of postsynaptic serotonin has been proven using phototherapy. Two case studies used phototherapy to treat symptoms of NES and depression.[39]

On a 51-year-old female with depression and NES, Freidman and colleagues conducted a study using paroxetine and bright light therapy. The results showed that discontinuation of the phototherapy made her NES symptoms return.[40] The effect of bright light therapy was also studied on 15 patients with NES, and the results showed a tremendous reduction in NES symptoms along with mood and sleep disturbance after treatment.[41]

Differential Diagnosis

Night eating syndrome is usually confused with sleep-related eating disorders. The main differential criterion between NES and sleep related-eating disorders is the nature and the component of nocturnal eating. While the NES is composed of both hyperphagia and nocturnal eating along with awareness, sleep-related eating disorders are mainly characterized by repeated involuntary eating habits during sleep. [2] A sleep-related eating disorder is considered parasomnia due to involuntary and poorly recalled eating habits, along with nonfood items consumed, sharing similarities to sleepwalking.[2]

[2] A sleep-related eating disorder is considered parasomnia due to involuntary and poorly recalled eating habits, along with nonfood items consumed, sharing similarities to sleepwalking.[2]

Night eating syndrome can be classified as an insomnia-related disorder as patients are awake, aware, and able to recall their eating habits. Generally, patients with NES do not report underlying sleep disorders. However, some patients might report both syndromes.[2][42]

Sharing the behavior of evening hyperphagia between NES and binge eating disorder does not necessarily mean they share the same etiology. Unlike binge eating disorder, evening hyperphagia in NES patients is mainly correlated to nocturnal anxiety.[20] In addition, the amount of food consumed in the evening in patients with NES is not as large (≈300Kcal) as in patients with binge eating disorders.[23]

Prognosis

Patients treated for NES with pharmacological, cognitive therapy, and lifestyle changes have noticed a significant improvement in their symptoms. [43] For those who are untreated, many health issues and emotional challenges are related to being overweight or having obesity, such as high cholesterol, diabetes, and high blood pressure.[6]

[43] For those who are untreated, many health issues and emotional challenges are related to being overweight or having obesity, such as high cholesterol, diabetes, and high blood pressure.[6]

Complications

Patients with NES commonly become overweight due to increased calorie intake before bedtime. The increased caloric intake results in complications such as diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiac disease, and obesity. Without psychotherapy, psychiatric disturbances can develop.[44]

An association between NES and various psychopathologies, particularly depression, was found in most studies.[16][35] Many patients with NES were found to meet lifetime criteria for major depressive disorders, MDD, substance abuse, and anxiety disorder.[45][46]

Deterrence and Patient Education

NES is a type of eating disorder characterized by excessive night eating habits (after dinner) or awakening from sleep to eat (nocturnal ingestions).[6] Additionally, three or more symptoms occur: the urge to eat between dinner and sleep, morning anorexia, maintenance insomnia or sleep onset, depressed mood or worsened mood in the evening and the belief that without eating, one can not get back to sleep. [2][3]

[2][3]

The prevalence in the United States is 1.5%, about the same as binge eating disorder.[6] The symptoms are often in remission and relapse according to life stressors, starting in early adulthood.[13][14] The treatment includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy, such as cognitive behavioral therapy.[43]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Since most patients will not bring up issues with night eating either due to shame or guilt, it is recommended to use screening questions. The primary care provider should refer the patient to a psychiatric specialist for appropriate treatment.[6] Patients with type 2 diabetes need to be screened for NES due to the high percentage of patients with pre-existing type 2 diabetes having clinical NES.[47] After diagnosis, treatment should be followed by an interprofessional healthcare team that includes psychiatry, internal medicine, and endocrinology, working with nurses, pharmacists, and other mental health professionals.

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

STUNKARD AJ, GRACE WJ, WOLFF HG. The night-eating syndrome; a pattern of food intake among certain obese patients. Am J Med. 1955 Jul;19(1):78-86. [PubMed: 14388031]

- 2.

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O'Reardon JP, Geliebter A, Gluck ME, Vinai P, Mitchell JE, Schenck CH, Howell MJ, Crow SJ, Engel S, Latzer Y, Tzischinsky O, Mahowald MW, Stunkard AJ. Proposed diagnostic criteria for night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2010 Apr;43(3):241-7. [PMC free article: PMC4531092] [PubMed: 19378289]

- 3.

de Zwaan M, Marschollek M, Allison KC. The Night Eating Syndrome (NES) in Bariatric Surgery Patients. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015 Nov;23(6):426-34. [PubMed: 26395455]

- 4.

Lamerz A, Kuepper-Nybelen J, Bruning N, Wehle C, Trost-Brinkhues G, Brenner H, Hebebrand J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B.

Prevalence of obesity, binge eating, and night eating in a cross-sectional field survey of 6-year-old children and their parents in a German urban population. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;46(4):385-93. [PubMed: 15819647]

Prevalence of obesity, binge eating, and night eating in a cross-sectional field survey of 6-year-old children and their parents in a German urban population. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Apr;46(4):385-93. [PubMed: 15819647]- 5.

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ. Familial aggregation in the night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2006 Sep;39(6):516-8. [PubMed: 16609983]

- 6.

McCuen-Wurst C, Ruggieri M, Allison KC. Disordered eating and obesity: associations between binge-eating disorder, night-eating syndrome, and weight-related comorbidities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018 Jan;1411(1):96-105. [PMC free article: PMC5788730] [PubMed: 29044551]

- 7.

Rand CS, Macgregor AM, Stunkard AJ. The night eating syndrome in the general population and among postoperative obesity surgery patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1997 Jul;22(1):65-9. [PubMed: 9140737]

- 8.

de Zwaan M, Müller A, Allison KC, Brähler E, Hilbert A. Prevalence and correlates of night eating in the German general population.

PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97667. [PMC free article: PMC4020826] [PubMed: 24828066]

PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97667. [PMC free article: PMC4020826] [PubMed: 24828066]- 9.

Vander Wal JS. Night eating syndrome: a critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012 Feb;32(1):49-59. [PubMed: 22142838]

- 10.

Kucukgoncu S, Midura M, Tek C. Optimal management of night eating syndrome: challenges and solutions. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:751-60. [PMC free article: PMC4371896] [PubMed: 25834450]

- 11.

Tholin S, Lindroos A, Tynelius P, Akerstedt T, Stunkard AJ, Bulik CM, Rasmussen F. Prevalence of night eating in obese and nonobese twins. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009 May;17(5):1050-5. [PMC free article: PMC2923060] [PubMed: 19396084]

- 12.

Gallant AR, Lundgren J, Drapeau V. The night-eating syndrome and obesity. Obes Rev. 2012 Jun;13(6):528-36. [PubMed: 22222118]

- 13.

Marshall HM, Allison KC, O'Reardon JP, Birketvedt G, Stunkard AJ. Night eating syndrome among nonobese persons.

Int J Eat Disord. 2004 Mar;35(2):217-22. [PubMed: 14994360]

Int J Eat Disord. 2004 Mar;35(2):217-22. [PubMed: 14994360]- 14.

Napolitano MA, Head S, Babyak MA, Blumenthal JA. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: psychological and behavioral characteristics. Int J Eat Disord. 2001 Sep;30(2):193-203. [PubMed: 11449453]

- 15.

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, Stunkard AJ, Bulik CM, Lindroos AK, Thornton LM, Rasmussen F. Validation of screening questions and symptom coherence of night eating in the Swedish Twin Registry. Compr Psychiatry. 2014 Apr;55(3):579-87. [PubMed: 24457035]

- 16.

Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: a comparative study of disordered eating. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005 Dec;73(6):1107-15. [PubMed: 16392984]

- 17.

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, Crow S, O'Reardon JP, Berg KC, Galbraith J, Martino NS, Stunkard AJ. Prevalence of the night eating syndrome in a psychiatric population. Am J Psychiatry.

2006 Jan;163(1):156-8. [PubMed: 16390906]

2006 Jan;163(1):156-8. [PubMed: 16390906]- 18.

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O'Reardon JP, Martino NS, Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Stunkard AJ. The Night Eating Questionnaire (NEQ): psychometric properties of a measure of severity of the Night Eating Syndrome. Eat Behav. 2008 Jan;9(1):62-72. [PubMed: 18167324]

- 19.

Vinai P, Allison KC, Cardetti S, Carpegna G, Ferrato N, Masante D, Vallauri P, Ruggiero GM, Sassaroli S. Psychopathology and treatment of night eating syndrome: a review. Eat Weight Disord. 2008 Jun;13(2):54-63. [PubMed: 18612253]

- 20.

Sassaroli S, Ruggiero GM, Vinai P, Cardetti S, Carpegna G, Ferrato N, Vallauri P, Masante D, Scarone S, Bertelli S, Bidone R, Busetto L, Sampietro S. Daily and nightly anxiety among patients affected by night eating syndrome and binge eating disorder. Eat Disord. 2009 Mar-Apr;17(2):140-5. [PubMed: 19242843]

- 21.

Björntorp P, Rosmond R. Neuroendocrine abnormalities in visceral obesity.

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000 Jun;24 Suppl 2:S80-5. [PubMed: 10997616]

Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000 Jun;24 Suppl 2:S80-5. [PubMed: 10997616]- 22.

Epel E, Lapidus R, McEwen B, Brownell K. Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001 Jan;26(1):37-49. [PubMed: 11070333]

- 23.

Birketvedt GS, Florholmen J, Sundsfjord J, Osterud B, Dinges D, Bilker W, Stunkard A. Behavioral and neuroendocrine characteristics of the night-eating syndrome. JAMA. 1999 Aug 18;282(7):657-63. [PubMed: 10517719]

- 24.

O'Reardon JP, Ringel BL, Dinges DF, Allison KC, Rogers NL, Martino NS, Stunkard AJ. Circadian eating and sleeping patterns in the night eating syndrome. Obes Res. 2004 Nov;12(11):1789-96. [PubMed: 15601974]

- 25.

Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Lundgren JD, Martino NS, Heo M, Etemad B, O'Reardon JP. A paradigm for facilitating pharmacotherapy at a distance: sertraline treatment of the night eating syndrome.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;67(10):1568-72. [PubMed: 17107248]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;67(10):1568-72. [PubMed: 17107248]- 26.

Gluck ME, Geliebter A, Satov T. Night eating syndrome is associated with depression, low self-esteem, reduced daytime hunger, and less weight loss in obese outpatients. Obes Res. 2001 Apr;9(4):264-7. [PubMed: 11331430]

- 27.

Allison KC, Engel SG, Crosby RD, de Zwaan M, O'Reardon JP, Wonderlich SA, Mitchell JE, West DS, Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for night eating syndrome using item response theory analysis. Eat Behav. 2008 Dec;9(4):398-407. [PMC free article: PMC2583783] [PubMed: 18928902]

- 28.

Tzischinski O, Lazer Y. [Nocturnal eating disorder--sleep or eating disorder?]. Harefuah. 2000 Feb 01;138(3):199-203, 271, 270. [PubMed: 10883092]

- 29.

de Zwaan M, Roerig DB, Crosby RD, Karaz S, Mitchell JE. Nighttime eating: a descriptive study. Int J Eat Disord. 2006 Apr;39(3):224-32. [PubMed: 16511835]

- 30.

Crow S, Kendall D, Praus B, Thuras P. Binge eating and other psychopathology in patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Int J Eat Disord. 2001 Sep;30(2):222-6. [PubMed: 11449458]

- 31.

Allison KC, Crow SJ, Reeves RR, West DS, Foreyt JP, Dilillo VG, Wadden TA, Jeffery RW, Van Dorsten B, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome in adults with type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007 May;15(5):1287-93. [PMC free article: PMC2753278] [PubMed: 17495205]

- 32.

Morse SA, Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Hirsch IB. Isn't this just bedtime snacking? The potential adverse effects of night-eating symptoms on treatment adherence and outcomes in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006 Aug;29(8):1800-4. [PubMed: 16873783]

- 33.

Allison KC, Lundgren JD, Moore RH, O'Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for night eating syndrome: a pilot study. Am J Psychother. 2010;64(1):91-106. [PubMed: 20405767]

- 34.

Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Lundgren JD, O'Reardon JP. A biobehavioural model of the night eating syndrome. Obes Rev. 2009 Nov;10 Suppl 2:69-77. [PubMed: 19849804]

- 35.

O'Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ, Allison KC. Clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2004 Jan;35(1):16-26. [PubMed: 14705153]

- 36.

Allison KC, Studt SK, Berkowitz RI, Hesson LA, Moore RH, Dubroff JG, Newberg A, Stunkard AJ. An open-label efficacy trial of escitalopram for night eating syndrome. Eat Behav. 2013 Apr;14(2):199-203. [PubMed: 23557820]

- 37.

Vander Wal JS, Gang CH, Griffing GT, Gadde KM. Escitalopram for treatment of night eating syndrome: a 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012 Jun;32(3):341-5. [PubMed: 22544016]

- 38.

Vander Wal JS, Maraldo TM, Vercellone AC, Gagne DA. Education, progressive muscle relaxation therapy, and exercise for the treatment of night eating syndrome.

A pilot study. Appetite. 2015 Jun;89:136-44. [PubMed: 25660340]

A pilot study. Appetite. 2015 Jun;89:136-44. [PubMed: 25660340]- 39.

Krysta K, Krzystanek M, Janas-Kozik M, Krupka-Matuszczyk I. Bright light therapy in the treatment of childhood and adolescence depression, antepartum depression, and eating disorders. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2012 Oct;119(10):1167-72. [PubMed: 22806006]

- 40.

Friedman S, Even C, Dardennes R, Guelfi JD. Light therapy, obesity, and night-eating syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 May;159(5):875-6. [PubMed: 11986153]

- 41.

McCune AM, Lundgren JD. Bright light therapy for the treatment of night eating syndrome: A pilot study. Psychiatry Res. 2015 Sep 30;229(1-2):577-9. [PubMed: 26239768]

- 42.

Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, Geliebter A, Lundgren JD, Gluck ME, O'Reardon JP. Development of criteria for a diagnosis: lessons from the night eating syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 2009 Sep-Oct;50(5):391-9. [PMC free article: PMC3835341] [PubMed: 19683608]

- 43.

Pinto TF, Silva FG, Bruin VM, Bruin PF. Night eating syndrome: How to treat it? Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2016 Oct;62(7):701-707. [PubMed: 27925052]

- 44.

Zawilska JB, Santorek-Strumiłło EJ, Kuna P. [Nighttime eating disorders--clinical symptoms and treatment]. Przegl Lek. 2010;67(7):536-40. [PubMed: 21387771]

- 45.

Lundgren JD, Allison KC, O'Reardon JP, Stunkard AJ. A descriptive study of non-obese persons with night eating syndrome and a weight-matched comparison group. Eat Behav. 2008 Aug;9(3):343-51. [PMC free article: PMC2536488] [PubMed: 18549994]

- 46.

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, Affenito S, May A, Kraemer HC. Exploring the typology of night eating syndrome. Int J Eat Disord. 2008 Jul;41(5):411-8. [PubMed: 18306340]

- 47.

Abbott S, Dindol N, Tahrani AA, Piya MK. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J Eat Disord.

2018;6:36. [PMC free article: PMC6219003] [PubMed: 30410761]

2018;6:36. [PMC free article: PMC6219003] [PubMed: 30410761]

What is Night Eating Syndrome?

Skip to contentWhat is Night Eating Syndrome?

Night eating syndrome is an eating disorder, characterized by a delayed circadian pattern of food intake. Night eating syndrome is not the same as binge eating disorder, although individuals with night eating syndrome are often binge eaters. It differs from binge eating in that the amount of food consumed in the evening/night is not necessarily objectively large nor is a loss of control over food intake required. It was originally described by Dr. Albert Stunkard in 1955 and is currently included in the “Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder” category of the DSM-5.

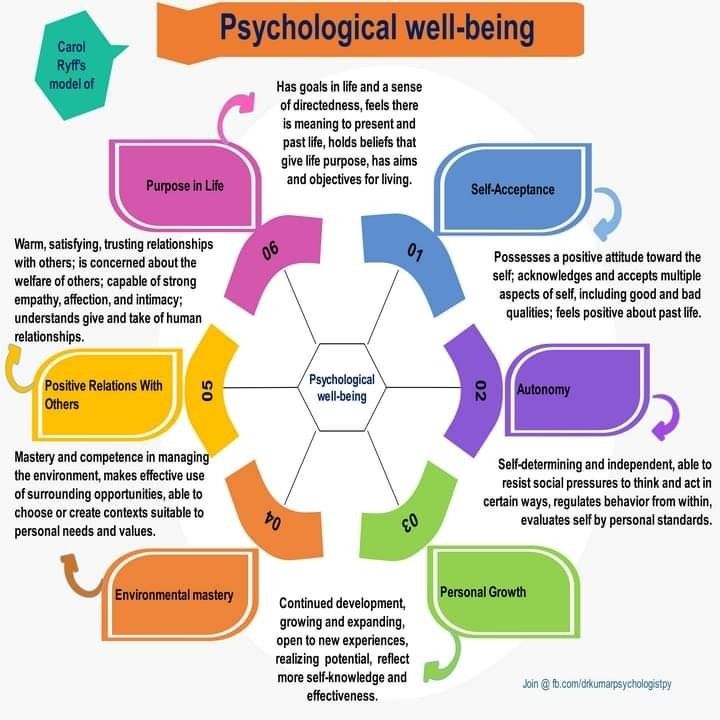

Individuals with night eating syndrome feel like they have no control over their eating patterns, and often feel shame and guilt over their condition.

Night eating syndrome affects an estimated 1.5% of the population, and is equally common in men and women, according to the National Institute of Mental Health.

Signs & Symptoms of Night Eating Syndrome

Those with night eating syndrome may be overweight or obese. They feel like they have no control over their eating behavior, and eat in secret and when they are not hungry. They also feel shame and remorse over their behavior.

They may hide food out of shame or embarrassment. Those with night eating syndrome typically eat rapidly, eat more than most people would in a similar time period and feel a loss of control over their eating. They eat even when they are not hungry and continue eating even when they are uncomfortably full. Feeling embarrassed by the amount they eat, they typically eat alone to minimize their embarrassment. They often feel guilt, depression, disgust, distress or a combination of these symptoms.

Those with night-eating syndrome eat a majority of their food during the evening. They eat little or nothing in the morning, and wake up during the night and typically fill up on high-calorie snacks.

Traits of patients with night-eating syndrome may include being overweight, frequent failed attempts at dieting, depression or anxiety, substance abuse, concern about weight and shape, perfectionism and a negative self-image.

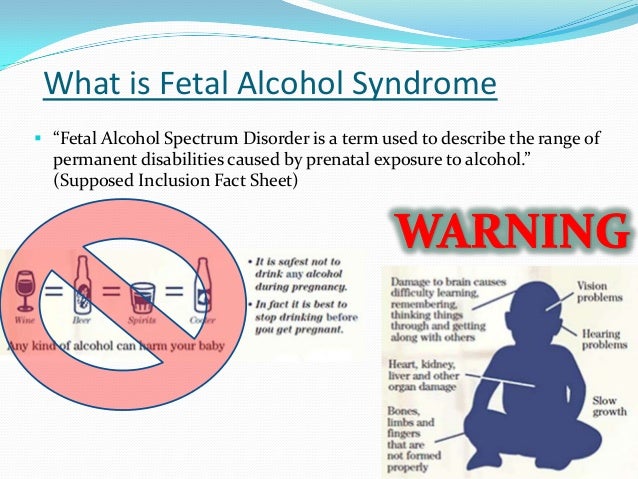

Causes of Night Eating Syndrome

Causes of night eating syndrome vary, but there are usually a variety of contributing factors. Sometimes college students pick up the habit of eating at night and are unable to break the habit when they become working adults. High achievers sometimes work through lunches, and then overcompensate by eating more at night.

Night eating syndrome, ironically, may be a response to dieting. When people restrict their intake of calories during the day, the body signals the brain that it needs food and the individual typically overcompensates at night. Night eating may also be a response to stress.

Those with night eating syndrome are often high achievers, but eating patterns can affect their ability to socialize or manage work-related responsibilities. They may also have different hormonal patterns, resulting in their hunger being inverted so that they eat when they should not and do not eat when they should.

Medical Impact of Night Eating Syndrome

Individuals with night eating syndrome are often obese or overweight, which makes them susceptible to health problems caused by being overweight, including high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol. Those who are obese increase their risk of heart diseases, many types of cancer and gallbladder disease.

Those who are obese increase their risk of heart diseases, many types of cancer and gallbladder disease.

Individuals with night eating syndrome often have a history of substance abuse, and may also suffer from depression. They typically report being more depressed at night. They also frequently have sleep disorders.

Treating Night Eating Syndrome

As with other eating disorders, successful treatment of night eating syndrome typically requires a combination of therapies.

Treatment for night eating syndrome typically begins with educating patients about their condition, so they are more aware of their eating patterns and can begin to identify triggers that influence how they eat. Just identifying that they have night eating syndrome and that it is not their fault can be an important first step toward recovery.

Treatment of night eating syndrome also includes nutrition assessment and therapy, exercise physiology, and an integration of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT), interpersonal therapy (IT) and stress management. An additional online component may also help patients gain control over their disorders.

An additional online component may also help patients gain control over their disorders.

It is important for individuals with night eating syndrome to change their behavior by changing their beliefs. If they believe that they are powerless to change the way they eat, they will not be able to change.

Helping Someone With Night Eating Syndrome

If you suspect you or someone you know has Night Eating Syndrome (NES), do something about it. Night Eating Syndrome can have a dramatic impact on a person. Seek professional counseling as soon as possible.

Notice: JavaScript is required for this content.

404: Page not found

The page has probably been moved or removed.

The site is constantly updated to keep the information up to date; the absence of a particular page is a normal situation.

Please,

use form Site Search

select the topic of interest in Tag Cloud

or go to the desired section through Site Map .

Cannot find 'tags' template with page ''

Our hospitals

University Clinical Hospital No. 1 Moscow, st. Bolshaya Pirogovskaya, 6, building 1 University Clinical Hospital No. 2 Moscow, st. Pogodinskaya, 1, building 1 University Clinical Hospital No. 3 Moscow, st. Rossolimo, 11, building 4,5 University Clinical Hospital No. 4 8 (49)9) 246-76-83 Moscow, m. Sportivnaya, st. Dovatora, 15 University Clinical Hospital No. 5 143069, p / o Vvedenskoye, Zvenigorod Sechenov Center for Motherhood and Childhood Moscow, st. B. Pirogovskaya, 19, building 1 Centralized laboratory and diagnostic service

View all hospitals

Our hospitals on the map

University Clinical Hospital No. 1 University Clinical Hospital No. 2 University Clinical Hospital No. 3 University Clinical Hospital No. 4 University Clinical Hospital No. 5 Sechenov Center for Motherhood and Childhood Center of Cardioangiology (NPTsIK) Dental center Institute of Medical Parasitology, Tropical and Transmissible Diseases. E.I. Marcinovsky Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology. V.F. Snegirev Center for the Treatment of Addictive Disorders

1 University Clinical Hospital No. 2 University Clinical Hospital No. 3 University Clinical Hospital No. 4 University Clinical Hospital No. 5 Sechenov Center for Motherhood and Childhood Center of Cardioangiology (NPTsIK) Dental center Institute of Medical Parasitology, Tropical and Transmissible Diseases. E.I. Marcinovsky Clinic of Obstetrics and Gynecology. V.F. Snegirev Center for the Treatment of Addictive Disorders

News

April 7 - World Health Day

04/07/2023

March 27 - Nephrologist's Day

03/27/2023

Cardiac patch instead of holter. Sechenov University took the heart rate under the control of artificial intelligence

Sechenov University took the heart rate under the control of artificial intelligence

03/09/2023

February 15 - International Day of the operating room nurse

02/15/2023

February 9 - International Day of the Dentist

02/08/2023

February 4 Open Day at the Clinic of Coloproctology and Minimally Invasive Surgery UKB No. 2

01/30/2023

All newsWhat is the nocturnal appetite syndrome and why is it dangerous?

There are many people in our world who have a pronounced night eating syndrome. If you can't fall asleep without a hearty meal at night, or wake up in the middle of the night with an acute feeling of hunger, then you know what it is. Why night hunger occurs and how to deal with it, experts said.

“Permanent breakdowns and nighttime “escapes” to the kitchen arise due to improper nutrition and distribution of calories throughout the day,” says Anna Ivashkevich, nutritionist, clinical nutritionist, member of the National Association of Clinical Nutrition Union . – There is no single correct solution, everything is very individual. You can stop eating after 6:00 pm, eat a hearty breakfast, add more protein to your diet and try to avoid high-fat and carbohydrate foods, but you will still suffer from excess weight and dream of pizza late at night.

– There is no single correct solution, everything is very individual. You can stop eating after 6:00 pm, eat a hearty breakfast, add more protein to your diet and try to avoid high-fat and carbohydrate foods, but you will still suffer from excess weight and dream of pizza late at night.

According to the expert, if you go to bed after 23:00 or 00:00, then your light snack or low-calorie dinner eaten at 17:00 will be processed by the body long ago, and you will fall asleep with a feeling of hunger. And if you repeat this scheme daily, then everything eventually leads to a breakdown and abundant overeating at night or at night.

The most correct solution would be not to eat 1.5-2 hours before bedtime and evenly distribute your food throughout the day, namely: 25% kcal should come from breakfast, 35% kcal from lunch, 25% kcal from dinner and 15 % of multiple snacks.

“If you are a night owl and your day starts at 12:00 in the morning and ends at 01:00 or 02:00 at night, then the last meal should be at 22:00-23:00,” says Anna Ivashkevich. - It can be a vegetable salad, hummus, boiled fish or baked chicken. By the way, a few pieces of cheese eaten before bedtime, or 1-2 teaspoons of red caviar have a positive effect on the quality of sleep.

- It can be a vegetable salad, hummus, boiled fish or baked chicken. By the way, a few pieces of cheese eaten before bedtime, or 1-2 teaspoons of red caviar have a positive effect on the quality of sleep.

If, on the contrary, you are a fan of early rises and start your day at 7:00 or 8:00 in the morning, and go to bed at 22:00 or 23:00, then, according to the expert, the last meal should be at 20 :00.

“Not eating between 6:00 pm and 7:00 am or 8:00 am can lead to bile stasis and stone formation, weight gain, as your body will be deprived of nutrients for a long time and, accordingly, will accumulate the received calories and store them, not lose weight."

After 18:00, those who go to bed at 21:00 may not eat. Snack options for quality and restful sleep (pick one):

- banana

- radish and tomato

- Eggs

- Brown rice

- turkey

- Red caviar

- Hungry nuts

- Fish

- Brown rice

- Red Wine glass

Photo: Yay/TASS

however. According to nutritionist, nutritionist, therapist Maria Cherevko , there are several main reasons why you are so drawn to the kitchen at night:

According to nutritionist, nutritionist, therapist Maria Cherevko , there are several main reasons why you are so drawn to the kitchen at night:

- Neuroendocrine disorders (lead to disturbances in the metabolism of cortisol, insulin, leptin, causing a feeling of uncontrolled hunger).

- Circadian rhythm disorders (energy in the evening and morning fatigue, insufficient sleep, etc.).

- Peculiarities of human perception of stress (it is not the presence of stress that is important - everyone has it, but the ability to adequately respond to it).

- Features of education and cultural traditions (family settings affecting daily routine and nutrition).

- Genetic mutations responsible for satiety, carbohydrate metabolism and stress hormones.

- Presence of a spectrum of anxiety-depressive disorders .

“Therefore, there is no and cannot be a unified approach to the treatment of night eating syndrome,” says the expert. – Nevertheless, whatever one may say, the treatment is based on two links. The first is lifestyle modification aimed at restoring the physiological rhythms of the body (principles of rational nutrition, physical activity, restoration of circadian rhythms and work and rest regimes). The second is working with anxiety and stress with the help of specialists.

– Nevertheless, whatever one may say, the treatment is based on two links. The first is lifestyle modification aimed at restoring the physiological rhythms of the body (principles of rational nutrition, physical activity, restoration of circadian rhythms and work and rest regimes). The second is working with anxiety and stress with the help of specialists.

⠀

Life hacks from Maria Cherevko:

- The best pillow is fatigue. Let active sports into your life - classes are needed in the second half of the day, but no later than 3 hours before bedtime. Reasons for anxiety will never go away - change your reaction to them with the help of a psychologist.

“Unfortunately, people who work night shifts find it difficult to solve these problems,” says the expert. - Our hormonal rhythms are subject to natural fluctuations, and not to the employer. In this regard, we can only advise effective recovery between shifts. Sleep, relaxation routines, and walks in the fresh air will help to normalize cortisol levels.