Should i tell my therapist everything

Should I Tell My Therapist Everything? : OpenCounseling

Short On Time?

Here's two ways to read the article.

Whether you’re new to therapy or have been going for a while, you may be struggling with a pretty big question: “Should I tell my therapist everything?”

The purpose of therapy is to provide a safe space where you can talk about all the things you can’t talk about anywhere else. The reason your confidential relationship with your therapist is protected by law is that therapy just doesn’t work if you can’t trust that your therapist will keep your secrets.

But you probably know that there are exceptions to confidentiality, and lack of clarity about exactly what these are can make opening up in therapy feel even scarier than it already does.

Even the most ethical, above-the-board disclosures by therapists can shatter a client’s trust in therapy forever. Stories from clients who were hurt by a therapist’s disclosure might make you afraid to share important information with your therapist—or want to avoid therapy altogether.

We’re here to help. We want you to be able to walk into therapy confident and well-informed about what your therapist can and can’t share. Trust us—there is very little a good therapist can or would ever tell anyone about you. (And there are red flags that can help you spot and avoid the bad ones.)

We also want to go a little deeper and explore why it can be scary to share even those things you know your therapist can’t tell anyone else. It takes a lot of courage to open up in therapy—but the rewards can be huge.

Read on for some real talk about the consequences of telling—or not telling—your therapist everything.

On This Page

- What Shouldn't I Tell My Therapist?

- What If I Lie to My Therapist?

- Will My Therapist Think I'm Weird?

What Shouldn't I Tell My Therapist?

There really isn’t much you shouldn’t tell your therapist. But it’s a good idea to try not to tell them everything all at once.

Research shows that about 20 percent of clients leave therapy early and that most of the people who drop out of therapy quit after only two sessions.

There are many reasons people quit therapy so soon after they begin, and one of them is that they feel overwhelmed by how much they shared in their first session. They feel so nervous about having to go back and follow up about it that they just don’t go back.

Your therapist can handle however much you're ready to tell them—but the key is knowing what you are ready for.

A relationship with a therapist is like any relationship in that it flows better and is much more rewarding if you open up and share about yourself slowly, over time, as you get to know and trust one another better. If you go into full confession mode right away, you may worry you’ll be rejected for it.

Chances are extremely low your therapist would reject you for anything you tell them, but you may feel rejected even if your therapist is warm and caring toward you. Your self-loathing might kick in and make it feel too difficult to ever face that same therapist again who now knows

that thing about you.

So, our advice is to take it slow. You can start by telling your therapist your therapy goals, your reasons for coming to therapy, and the basic stuff that doesn’t feel too terribly personal: for example, whether you’re having symptoms of anxiety or depression, thinking about changing your career, or wanting to improve your relationships.

It’s probably best to wait before sharing the thing you’re most afraid of someone else knowing about you or your worst childhood memories. Again, it’s not bad to share these things early in therapy, and your therapist can handle it if you do. But chances are good it will make you feel bad, because it’s nerve-wracking to share your carefully guarded secrets with anyone—even a therapist.

The Easiest Way to Waste Your Time and Money in Therapy

Therapists find most of what you tell them interesting, because it’s all a clue to the beautiful mystery that is you.

That said, there are diminishing returns for giving your therapist details about your sandwich order from lunch, that outrageous gossip you heard at work, or what you think about today’s weather.

Therapy is a beautiful opportunity to go deeper than most of your conversations allow you to go. Your therapist actually wants to know the real answer to the question, “How are you?”

Superficial chit-chat and banter can be okay as an ice breaker at the beginning of a session, but spending any more than a few minutes chatting with your therapist the same way you would with a friend or a co-worker is a waste of the time and money you’re investing in therapy.

So, among the very few things we would say you shouldn’t tell your therapist are the chatty details of your day. Avoid the safe subjects you don’t have any big feelings or deep thoughts about and the conversation topics you use to put others at ease in casual social situations.

Your therapist doesn’t need any of that careful social tending. They want to know how you really feel and what you really think. So, tell them—you need to for therapy to work anyway!

Your therapist

will ask a lot of really personal questions in the beginning. Answer them as honestly as you can, but keep in mind you don’t have to share any more details than you feel ready to share. It’s perfectly legitimate to tell your therapist, “I’m not comfortable talking about that yet.”

Answer them as honestly as you can, but keep in mind you don’t have to share any more details than you feel ready to share. It’s perfectly legitimate to tell your therapist, “I’m not comfortable talking about that yet.”

And while we don’t recommend lying to your therapist (read on for more about what happens when you do), it’s not the end of the world if you do, especially in the beginning. Sometimes, telling little white lies or lying by omission early on in therapy is the only thing that makes you feel safe enough to keep going until you feel ready to tell your therapist the truth.

What If I Lie to My Therapist?

Maybe the thought of lying in therapy seems strange to you, or maybe you’ve already done it.

Either way, it’s not unusual—in fact, researchers have found that more than 90 percent of therapy clients lie to their therapists.

One of the most common lies people tell their therapists is that they’re enjoying or getting a lot out of therapy when they’re not.

It’s totally counterproductive to do this, but also totally understandable—most of us don’t like to bluntly tell others that we don’t like them or that we don’t think they’re doing a good job. And most people go into therapy wanting their therapist to like and think well of them—not resent them for telling them they think they suck.

Pro Tip!

It might seem weird, but it’s actually okay to tell your therapist you think they suck. Maybe you can find a kinder or more diplomatic way to say it—your therapist will probably appreciate it—but they actually want to know when what they’re doing isn’t working.

For more information about how to talk to your therapist about this and other difficult subjects—and how to decide when it just isn’t worth it to keep seeing your therapist—you can read our articles, “What If I Don’t Like My Therapist?” and “How Do I Break Up with My Therapist?”

Therapy clients also lie about how severe their symptoms are, what they’re insecure about, and how bad they’re feeling. It’s also common to lie about having suicidal thoughts.

It’s also common to lie about having suicidal thoughts.

The downside of telling any of these lies (or others) is that it limits how helpful your therapist can be. If a therapist doesn’t know how bad it really is for you, or that the way they’re working with you isn’t helping, you’re probably going to end up feeling pretty dissatisfied with therapy. You may even quit early without having been helped much by it.

Pro Tip!

It’s a lot more effective to tell a therapist, “I’m not ready to talk about that yet,” or “There’s something I want to tell you, but not yet,” than it is to lie about it. This way, your therapist will know there’s something important to come back to when you feel ready, but also that it’s not the right time to go into it now. Good therapists will respect this boundary when you set it.

Therapy is many things, and one of the most important is that it’s a quest for the truth. The truer a picture your therapist has of you, the more they’re going to be able to help you.

That said, some truths are hard to tell. Therapists know this, too. Telling your therapist a lie, especially early on, is not going to doom you or prevent you from being helped by therapy. It’s just going to limit how helpful therapy is for you—until you’re ready to tell the truth.

Will My Therapist Think I'm Weird? Will They Hate Me?

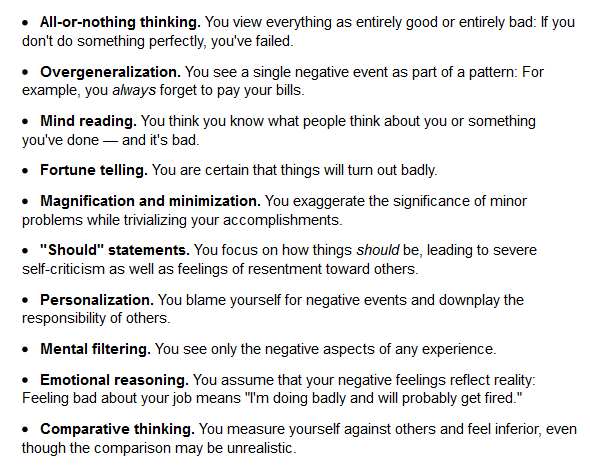

You might worry about sharing something even if you know your therapist can’t break confidentiality or report it—you might simply worry that your therapist will judge you for it.

If so, you’re not alone. It’s normal in nearly every social situation to be conscious of how you come across and to avoid saying or doing things that might cause someone else to dislike or reject you. These instincts don’t go away just because you intellectually know therapy is supposed to be different.

And it doesn’t help when you hear horror stories from people whose bad therapists acted unethically or unprofessionally and left them feeling rejected, worse about themselves, or looked down upon.

We’re not going to lie—those bad therapists are out there, but good therapists don’t do that.

Good therapists appreciate the sacred nature of what happens in therapy and see you in a different way than anyone else does.

A good therapist doesn’t stop where most people stop when you tell them something weird about you (if it’s actually weird—it probably isn’t nearly as weird as you think). They don’t just go, “Wow, that’s weird.” First, they know we’re all “weird” when no one else is looking, because “normal” is just an act we put on when we’re in public.

Second, and even more importantly, they care. They’re curious, maybe even fascinated by what you’re telling them, and they want to help you figure out why you do that weird thing you do. And nearly always, the reason is something that makes a therapist feel compassion or respect for you, not ridicule.

Even if the way you cope is quirky, what’s driving your behavior is probably something a lot of people can relate to and understand—including your therapist.

What Happens If I Tell My Therapist I'm Suicidal?

One of the scariest things to tell a therapist is that you’re having suicidal thoughts. It’s scary just to have them. Thinking about suicide can make you feel defective, broken, or like you have a dark secret you have to hide at all costs. It’s hard to tell anyone out of fear of how they might judge you—even a therapist.

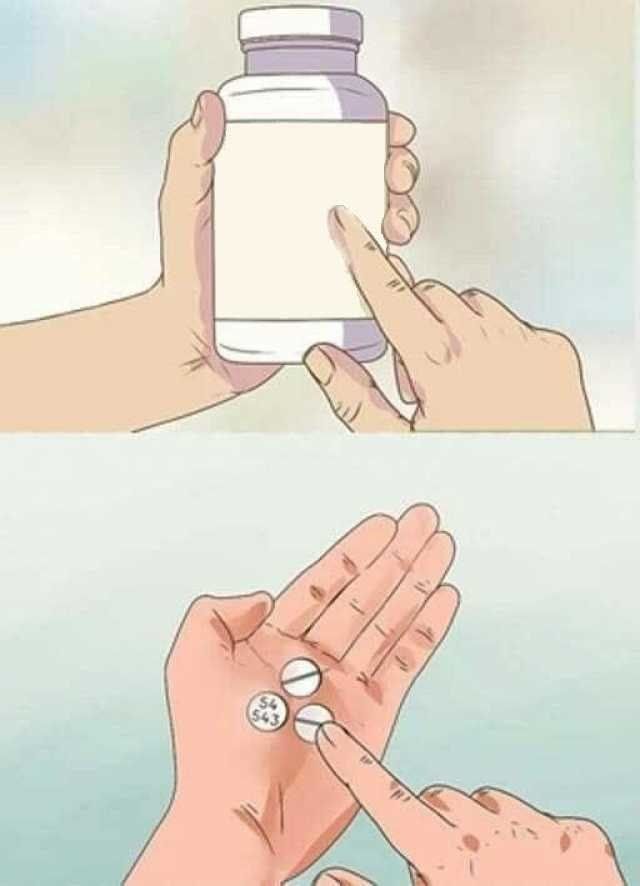

Then there’s the fact that one of the few times a therapist can break confidentiality is when you’re a danger to yourself or others. You might worry that the second you tell your therapist that you’ve ever thought about killing yourself, they’ll immediately want to call an emergency hotline, transfer you to a higher level of care, or even try to get you hospitalized.

Fortunately, though, there’s more nuance to it than that. Simply telling your therapist you’ve ever had suicidal thoughts does not mean they will immediately try to escalate the situation or refer you out.

After all, if you can’t talk to a therapist about suicidal thoughts, who else can you possibly talk to?

Therapists are familiar with the topic of suicidality, trained to talk about it and treat it with nuance, and are aware of how common suicidal thoughts actually are.

While there’s a chance an inexperienced therapist might get anxious if you tell them you’re thinking about suicide, veteran therapists will calmly explore this with you and gather information to determine if what you’re experiencing actually indicates you need a higher level of care.

You may well be in an advanced state of crisis that requires more than weekly therapy to address. Or working with a therapist may be all you need to deal with your suicidal thoughts. Your therapist will help you figure that out.

Is Therapy Enough or Do I Need a Higher Level of Care?

There are some important and specific distinctions therapists use to determine your risk level when you tell them you’ve had suicidal thoughts (or thoughts of harming someone else).

Therapists are allowed—and in some states, required—to break confidentiality when a client presents an imminent risk of harm to themselves or others. This means you need to have:

- Active, current thoughts about seriously harming (or killing) yourself or others

- Specific ideas about how you would do it—and an active plan and intent to do it

- Knowledge of and access to the means to carry out your plan to harm yourself or others

When all of these are true, the appropriate level of care is hospitalization. But that’s not a bad thing if it’s what you actually need. The whole point of going to a psychiatric unit for a few days (the average length of stay is 3 to 10 days) is to keep you safe and stabilize you until you’re no longer a danger to yourself or others.

But that’s not a bad thing if it’s what you actually need. The whole point of going to a psychiatric unit for a few days (the average length of stay is 3 to 10 days) is to keep you safe and stabilize you until you’re no longer a danger to yourself or others.

Even if you don’t enjoy your time in the hospital (some do!), it might just save your life—and most people who are prevented from harming themselves or others are deeply grateful they were. The nadir of a crisis is often an inflection point when life really starts to turn around and get better.

That said, hospitalization is not warranted when:

- You’ve had suicidal (or homicidal) thoughts in the past, but not recently

- You have vague, non-specific suicidal thoughts (such as “Sometimes, I wish I was dead”)

- You have semi-specific thoughts, but no plan or intent to act on them (i.e. “I sometimes wish I was dead but I would never do that to my family”)

Depending on the specific nature of your thoughts, and any risk or protective factors you have in your life, your therapist may:

- Have you sign a safety contract that spells out the steps you’ll take if your thoughts get worse or more specific,

- Suggest additional care besides therapy (such as group therapy or medication) or that you start coming to therapy more often, and/or

- Give you information about local crisis intervention resources including state or local crisis lines or walk-in centers where you can get 24/7 crisis care.

A good therapist will not report you or try to get you hospitalized just because you’ve ever thought about suicide or just because the idea recently, startlingly, popped into your mind. They have to have other information or evidence that your risk level for suicide is high.

Your therapist is there to help you figure out why this is happening and address the root cause as well as any immediate crisis you’re in. This means they need to be caring, respectful, and sensitive to what’s actually going on with you, and not take a one-size-fits-all approach.

A good therapist will want to help you get into a higher level of care if it’s really what you need—but they won’t try to escalate and push you into one if it isn’t.

Ultimately, no matter what kind of suicidal thoughts you’re having, or what your risk level is, you should tell your therapist.

Therapists are not the thought police, and their response to you is not punishment for having the wrong kind of thoughts. The plan of action a good therapist comes up with will be tailored to your specific situation so that you get the care you need to stay safe and get through a crisis.

The plan of action a good therapist comes up with will be tailored to your specific situation so that you get the care you need to stay safe and get through a crisis.

A good therapist will not push you into a higher level of care if it isn’t what you need. They will not judge you. Instead, they will meet you where you are and do all they can to help you.

Where to Call for Help

If you’re going through a mental health crisis, there’s someone you can call.

If you’re at immediate risk of harm, or have already harmed yourself, you should call 911 immediately.

If you’re thinking of suicide, but are not at immediate risk of harm if you don’t get medical intervention right away, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or a local mental health crisis hotline.

For lists of different mental health crisis hotlines you can call, you can go to any of the following pages on our site:

- National and International Suicide Hotlines

- Free Mental Health Hotlines in the United States

- The United States Mental Health Services Guide

On that last page, you can find information specific to your state, including the mental health crisis hotline for your city or county. Just select your state to get the local information you need.

Just select your state to get the local information you need.

What If I Tell My Therapist About Using Drugs?

Is your therapist cool or are they a narc? What will they do if you tell them you use alcohol, marijuana, or other legal drugs?

What will they do if you tell them you use illegal drugs? And what will they do if you tell them you’re using a lot of drugs, injecting drugs, or engaging in other high-risk behavior related to drug use?

Nothing. Your therapist will do nothing.

Well, not exactly. They’ll want to talk about it. They’ll want to explore what you’re doing, and why, and whether it’s causing problems in your life. They’ll want to know if it’s affecting your physical or mental health.

But they won’t turn you in to the cops. The only way drug use is ever an exception to confidentiality is if you tell a therapist you have an active plan to end your life (or someone else’s) by causing an intentional overdose.

Can I Address Substance Use in Therapy?

When you’re concerned about your substance use, it can be confusing to know what to do and where to go. Is therapy enough, or do you need to go to a substance abuse program?

Is therapy enough, or do you need to go to a substance abuse program?

We’re here to help. We’ve written a series of articles to help you navigate the complex and sometimes confusing world of substance abuse treatment. The following articles can help you explore what level or type of treatment you might need:

- Levels of Care for Substance Abuse Treatment

- How Therapy for Substance Use and Addiction Works

- What’s the Difference Between Substance Use Counseling and Therapy?

In short, you can address issues related to substance use in therapy. However, you’ll want to make sure your therapist has the experience and training to help you. If not, you may want to look for another therapist or seek additional treatment or support in addition to therapy.

Yes, substance use can cause you harm or put you at risk of harm. But that’s also true of a lot of other dangerous things you can do that a therapist can’t break confidentiality about or report you for.

For example, if you tell your therapist you like to drive way faster than the speed limit, or engage in risky sexual behavior, or pick fights at bars with people twice your size, they’ll want to explore that with you, and help you stop if you want to stop. But they won’t call and tell your spouse, your employer, or the cops.

In fact, they can’t. They risk losing their license if they do. And no good therapist would want to do that anyway. Their whole job is to provide a safe, judgment-free zone where you can talk about, and perhaps address, any behavior you want to change—or simply understand.

It’s not that drug use can’t be a form of self-harm or that it can’t put you at risk of severe consequences to your health and well-being, up to and including death. It’s not that your therapist will be indifferent or won’t worry about what you’re doing.

It’s that it’s not your therapist’s job to control you. Their job is to help you understand why you do what you do.

The reason there are exceptions to confidentiality when you are actively suicidal or homicidal is that the risk is so extreme and specific. (It’s also because awful events have spurred states to enact laws allowing or requiring therapists to disclose in those specific circumstances.)

For the most part, it’s a therapist’s job to help you navigate the gray areas and dark places in your life and help you find your way to where you want to be—not judge you and turn you in.

What If I Tell My Therapist I Committed a Crime?

Guilt over harm you caused in the past or fear of consequences of a crime you committed are good reasons to go to therapy. But can you trust a therapist with the details of what you did?

It depends. The simple rule of thumb in therapy is that if you did it a long time ago, a therapist probably can’t or won’t report it. But if you’re doing it now, or are planning on doing it in the future, a therapist may be allowed, or even required, to report it.

There are exceptions, however, to this general rule of thumb. Read the tips box below for more details.

What Are the Exceptions to Confidentiality?

Exceptions to confidentiality vary from state to state. But in general, they fall into one of a few categories:

- When a client reports child abuse

- When a client reports elder abuse or vulnerable adult abuse

- When a client presents an imminent risk of harm to self or others

- When there is a court order for a therapist to release information

In most cases, therapists are only allowed to break confidentiality if a client presents an active threat of harm. However, there is some variation in state laws about child abuse, and in some states, therapists may be encouraged (or required) to report child abuse even if it occurred in the past.

This is because some laws consider the risk of a past abuser continuing to abuse any children or minors currently under their care. (In some states, this perspective may be applied to elder abuse or vulnerable adult abuse as well. )

)

Therapists may also be required to release information if you’re under federal investigation for acts of terrorism or some kinds of organized crime.

But therapists are not required, or even allowed, to report any other kind of violence or harm that happened in the past and that is not at risk of happening again. That said, there is not a perfect guarantee of confidentiality if you confess past crimes to a therapist.

While a therapist cannot legally volunteer that information to police (or anyone), if someone else has reason to suspect you of a crime, and suspects your therapist knows, they can seek to have a judge in a criminal or civil proceeding order your therapist to release your records or testify in court. If the judge agrees, and orders your therapist to share what they know, they will have no choice but to disclose what you’ve told them.

Savvy therapists will likely choose to leave details of anything you confess out of your notes, and if they are compelled to testify, they can push back, claim privilege, and say they don’t want to answer. However, if a judge overrules them and requires them to answer a question about what you told them, they have to answer.

However, if a judge overrules them and requires them to answer a question about what you told them, they have to answer.

You might wonder about more than just what your therapist is able or required to report, though. You might wonder if they’ll judge you, or even have to stop seeing you as a client if what you tell them is too disturbing.

First, consider what you have to confess in context of everything else a therapist might hear. Therapists hear a lot of things. People confess their darkest secrets to them. Depending on what they’ve heard, and their views, what you might think of as an awful confession might barely register to a therapist as bad.

For example, your therapist might have worked with someone who murdered multiple people or someone who devastated dozens of people financially. If so, that one time you punched someone, or that time you hit another car in a parking lot and peeled out without telling anyone, might seem pretty tame to them in comparison.

Also consider why you’d be telling them. The vast majority of therapists do what they do because they believe everyone has the capacity to heal and change and because they respect and enjoy working with people who want to change. They might not respect what you did, but they’ll respect that you’re trying to address it.

The vast majority of therapists do what they do because they believe everyone has the capacity to heal and change and because they respect and enjoy working with people who want to change. They might not respect what you did, but they’ll respect that you’re trying to address it.

If you're coming into therapy with guilt over something you did, you're probably wanting to figure out how to make amends or at least how to never hurt someone like that again. Most therapists will be moved by this and want to help you.

But yes, there is a chance you might tell your therapist something that would shock them. In rare cases, your therapist might have been victimized in a similar way or have another reason that they wouldn’t be able to work with you anymore (in which case, they would simply refer you to another therapist).

In extremely rare cases—such as if you confessed to a string of unsolved serial murders—they might decide it’s worth risking or giving up their license (and their entire career) to break professional laws and report it. But that level of drama is usually reserved for the movies.

But that level of drama is usually reserved for the movies.

For the most part, your therapist respects your desire to deal with what you did and embraces their role—which is not to get you in trouble, but to help you heal.

What Can My Therapist Report? What Does My Therapist Have to Report?

In the last section, we briefly went over the general categories of what a therapist has to report. But it’s a little more complicated than that.

First, to review: as mandated reporters, therapists are required to report any information they receive about child, elder, or vulnerable adult abuse. Depending on the state, they are either allowed or required to break confidentiality if a client presents an active and immediate threat of harm to themselves or others.

Which States Have "Duty to Warn" Laws?

In response to the 1976 Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California case, many states adopted “duty to warn” laws. The purpose of these laws is to try to prevent violent crime by allowing therapists to warn people when one of their clients is planning to harm someone.

There are two types of “duty to warn” laws: “mandatory” and “permissive.” In states with mandatory duty to warn laws, therapists are required to disclose information when a client tells them that they plan to harm or kill someone else. In states with permissive duty to warn laws, therapists are allowed to disclose this information, but they are not required to do so.

As of 2023, all but four states have some kind of duty to warn law. For updated information about whether a particular state has duty to warn laws and whether they are mandatory or permissive, you can go to this webpage published by the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Therapists are also required to release records or testify in court if they receive a court order. This means that if a judge tells them they have to do it, they have no choice unless they want to be held in contempt of court, which can result in fines or jail time. (But they don’t have to share your information just because a lawyer tries to get them to—the ultimate say comes from the judge. )

)

There are a few other exceptions you might want to consider. First, if you are going to therapy because someone compelled you to—such as child protective services, a judge, or a parent (if you’re under 18)—your therapist may be allowed or required to disclose information to the person or organization that’s making you go to prove that you’re meeting the requirements of your mandated therapy.

However, if this is the case, your therapist will explain it to you from the beginning. And the ethical rules they follow limit what they can disclose to the smallest amount of information necessary. In some cases, this may mean simply confirming that you attended your required sessions.

Your Therapist Is Not Your Partner in Crime

Other important exceptions to confidentiality apply if you are in any way trying to use therapy to mitigate or avoid legal consequences of a crime you committed (or are planning to commit) or are raising the issue of your own mental health in a legal proceeding.

This means there are exceptions to confidentiality when:

- You are claiming emotional damages in a lawsuit

- You sue your therapist—or your therapist sues you

- You are the subject of a national security investigation

- You are suspected of having committed acts of terrorism

- You try to enlist your therapist in active commission or cover-up of a crime

- You are trying to prove or disprove your sanity or competence in a court of law

Again, most therapists will respect any efforts you make in good faith to atone for or address a past crime in therapy. But if you’re actively involved with the legal system, don’t expect therapy to be a “get out of jail free” card. In most cases, it isn’t.

Sometimes, working with a therapist might help your case, but you might also unwittingly tell your therapist something they have to disclose that could end up hurting it. And don’t expect your therapist to help you commit fraud—they may end up reporting you for it instead.

While we think it’s important to know and consider all of the exceptions to confidentiality, we encourage you to think about your therapist as a person, too.

Most therapists don’t want to report clients. Most therapists don’t want to escalate a situation when you tell them something in confidence and are asking for their help.

Therapists want to honor your privacy and your trust in them. They take many steps to limit how much information other people can get from them, including writing minimalistic session notes, pushing back against legal requests that are anything less than a court order, and taking a case-by-case approach to dealing with client crises.

So, while it’s important to be informed and to understand the exceptions to confidentiality, it’s equally important to remember why therapists do what they do—and what brings you to therapy. You’re there to get help, not get reported or get in trouble, and to the extent they can, your therapist wants to honor that.

Conclusion: Can I Trust My Therapist?

There’s so much you want to tell your therapist. But can you trust them?

For the most part, you can. Therapists take confidentiality seriously. Any therapist who doesn’t is at risk of losing their license, because every single type of therapist is bound by professional rules that require them to maintain it.

And it’s more than just a requirement.

Confidentiality is a philosophy that gets to the very heart of what therapy is about.

If you can’t trust a therapist not to tell other people the deeply personal information you share with them, therapy won’t work. You’ll hold back, lie, or avoid the topic you most need to talk about, and your therapy will stay on the surface of your life, not touching or changing it much.

While confidentiality is a central principle of therapy, there are a few exceptions to it. These have been introduced over time, as lawmakers and the public have decided there are some situations where public safety takes precedence over therapeutic principles.

Keep in mind, though, that for the most part, therapists don't want to report their clients. They only do it when it's absolutely necessary or required by law.

So, while there is no perfect guarantee that your secrets are safe with your therapist, you can walk into your therapist’s office with confidence that they are (especially if you know what the exceptions to confidentiality are and whether they apply to what you want to talk to your therapist about).

And the rewards of opening up to a therapist are immense. Talking about secrets takes away their power. When you explore things you feel ashamed, uncertain, or self-conscious about with a therapist, you can make peace with them, let them go, or realize you never had a reason to be ashamed in the first place. So please, give it a chance—good therapy can change your life.

Related Posts

What’s In My Therapist’s Notes About Me?

What Is My Therapist Writing About Me?

Why Does My Therapist Stare at Me?

Stephanie Hairston

Stephanie Hairston is a freelance mental health writer who spent several years in the field of adult mental health before transitioning to professional writing and editing. As a clinical social worker, she provided group and individual therapy, crisis intervention services, and psychological assessments.

As a clinical social worker, she provided group and individual therapy, crisis intervention services, and psychological assessments.

Why It Happens and What to Do

If you feel like you’ve disclosed too much in therapy, it might feel awkward or nerve-wracking. But this common experience might actually be an opportunity.

It’s your first or 15th therapy session, and you blurted out something you’re convinced you shouldn’t have.

Maybe you mentioned a weird dream you had, a painful experience you never told anyone about, or that you’re furious with your therapist.

At best, you feel awkward and a tad bit anxious. At worst, you’re mortified and decide you’re never going back to therapy ever again.

First, feeling like you’ve disclosed too much in therapy is actually pretty common. Second, disclosing revealing information is often a good thing.

As psychologist and professor Thomas G. Plante, PhD, notes, “Therapists can’t really help people unless they know what is troubling the person they are trying to help. ”

”

Here’s how to pinpoint why you’re so bothered, and how to turn it into a fruitful moment for growth and change.

There may be many reasons you think you’ve said too much in therapy. Identifying the underlying concern helps you better understand what’s going on and gives you a starting point to discuss in therapy.

Maybe you’re experiencing the sinking feeling of regret, embarrassment, anxiety, or deep discomfort because:

- you’re not ready to face a very painful event or a trauma that you’ve revealed

- you don’t trust the therapeutic relationship enough (yet)

- what you said wasn’t the truth, or it wasn’t the whole truth

- you’re afraid of the legal, moral, personal, or relationship consequences

- you think your therapist might judge you for what you said

- you fear your therapist will reject or abandon you

- you think your therapist will find what you’ve said too difficult

- you think you’re betraying a loved one’s trust, or feel bad for talking about someone negatively

Either way, remember that you’re absolutely not alone in feeling this way.

And after the initial “Oh no!” feeling, remind yourself that therapy is such a powerful tool for change precisely because you’re processing thoughts, experiences, and emotions you’d never say to anyone else.

With that said, it’s still natural to feel some discomfort and negative feelings.

When you think you’ve shared too much, you might yearn to take it back. You might minimize its importance, glossing over it with your therapist as if it weren’t a big deal. Or you might berate yourself, feeling a deep sense of shame.

Try to resist the urge to pretend it didn’t happen, and be gentle with yourself.

Consider these tips:

- Bring up what you said at your next therapy session. A good therapist will understand your discomfort and help you work through it, Plante says. Together, you can discuss why the information you shared made you feel uneasy.

- Let them know you don’t want to talk about it. At your next session, tell your therapist you’re just not ready to explore the topic (yet).

- Let them know why you’re feeling regretful. If you feel you said too much because you’re uncomfortable with the therapist, consider sharing this, too. Sometimes you may need to find a therapist who’s better aligned with your values and needs, says Cadence Chiasson, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Denver, Colorado.

The amount of information you share with a therapist is entirely up to you. After all, you’re the client.

Still, the more honest you are with your therapist, the better. Giving your therapist a window into your thoughts, feelings, and experiences provides them with context and details, so they can best help you.

As you start therapy, you may choose to focus on less intense topics. This helps you get comfortable with the therapist. But everyone’s comfort levels around self-disclosure vary.

“I’ve had clients tell me what seems like all of their deepest, darkest secrets in our first meeting,” Chiasson says. “I’ve also had clients who take 6 months or more to start opening up. ”

”

There’s no topic truly off the table when it comes to therapy, says Ryan Drzewiecki, PsyD, a licensed psychologist and director of clinical operations at All Points North Lodge in Edwards, Colorado.

In fact, learning to speak freely is an essential part of therapy, he explains.

Most therapists will not judge you, says Peter Cellarius, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Los Gatos, California.

If they do — after all, they’re human — a good therapist will not let feelings of judgment get in the way of helping you.

Therapists are trained to put any judgment aside and focus on why a client is working with them, Chiasson says.

Therapists accumulate thousands of hours of direct and indirect counseling experience. They also complete continuing education on ethics throughout their career, says Drzewiecki.

This training guides them to help clients who have a wide variety of life experiences, and to do so without letting judgment affect their approach.

All therapists are trained to keep your information private and confidential. Creating a safe space for you to share revealing, personal information is a critical part of therapy that mental health professionals take very seriously.

However, in some situations, a therapist may be required to break confidentiality. Typically, this happens when the client or someone they know is in danger. The intent is to protect them from harm.

According to the American Psychological Association, these situations may include:

- plans of suicide or severely hurting yourself

- plans to hurt or kill another person

- ongoing domestic violence involving or in the presence of children

- abuse or neglect of children

- abuse or neglect of an older adult or an adult with disabilities

- a court order, which sometimes occurs if the client’s mental health comes into question during a court proceeding

Therapists may need to report this information to the police, adult protective services, child protective services, or similar law enforcement authorities. Different states may vary slightly in their confidentiality laws.

Different states may vary slightly in their confidentiality laws.

When starting therapy, mental health professionals typically explain privacy policies and are happy to answer any questions clients might have.

After all, most people aren’t familiar with these rules and regulations, so if you’re unsure or confused about confidentiality, raise your questions and concerns to your therapist.

Sharing something you think is too sensitive or personal can be uncomfortable. But know you’re not alone in thinking you’ve disclosed too much in therapy.

When this happens, it can help to explore why you think you’ve overshared and talk it over with your therapist. It’s often these types of vulnerable discussions that lead to illuminating insights and major growth.

Also, remember that therapists hear all types of stories and see all sorts of emotions. They’re trained to listen and help you reach your therapy goals.

Still uncomfortable about your sharing? It might be that your therapist simply isn’t the right fit for you. This, too, is common, and might mean it’s time to end therapy with them and find someone else to work with.

This, too, is common, and might mean it’s time to end therapy with them and find someone else to work with.

Whatever path you choose, be patient and understanding with yourself.

In therapy, as in life, it’s natural to stumble and fall. While difficult, these tumbles also provide the best learning opportunities — when we let them.

what to do, what to say and how to behave

So, you have decided to go to psychotherapy. How not to be afraid of the first dose, prepare for it and get the maximum effect? We share information and advice.

- What does it look like in practice?

- How to prepare for the first appointment with a psychotherapist?

- A few days before the first appointment:

- A few hours before admission:

- During the reception

"Therapist's appointment" can sound intimidating. I still remember stories about punitive psychiatry in the USSR, when people were registered and deprived of legal capacity. It may seem that the task of this doctor is to diagnose you and prescribe pills, which, moreover, cause addiction. And in the worst case - "upech" in a psychiatric clinic.

I still remember stories about punitive psychiatry in the USSR, when people were registered and deprived of legal capacity. It may seem that the task of this doctor is to diagnose you and prescribe pills, which, moreover, cause addiction. And in the worst case - "upech" in a psychiatric clinic.

Reality is very far from horror stories. Not only people with serious disorders go to a therapist. A professional psychotherapist always observes three conditions in his work: customer security , privacy and evidence-based approach .

What does it look like in practice?

Psychotherapy is not like consulting with an ordinary doctor. Strictly speaking, a psychotherapist is not a doctor. He may have a medical degree, but this is not a prerequisite.

Moreover, having such an education does not guarantee better help. Even if a person graduated from a medical university, he needs to additionally study to become a psychotherapist. Working with the mental state of a person, his emotions and thoughts is not a “treatment”.

Working with the mental state of a person, his emotions and thoughts is not a “treatment”.

The appointment takes place in person, in a specially equipped office, or online. The psychotherapist's office also does not look like a doctor's office - it looks more like a small living room. There are several comfortable chairs and tables in it, soft comfortable lighting is set up. If you plan to work with a therapist online, try to recreate a similar atmosphere in the room.

Psychotherapy is a conversational practice. This means that most of the time you will be talking to a specialist. But this will not be an ordinary conversation, as with a friend - therapeutic methods, exploration of your inner world and work on yourself will be woven into it. Everything you talk about is confidential. This means that the therapist does not disclose information even that you came to him. Even if close relatives ask.

Some approaches require homework assignments . Since therapy is always a two-way process, it is very important to work on yourself outside of the office. For example, a therapist may ask you to keep a diary of emotions as you work on understanding and expressing them. If you are working with others, your homework may be to apply the new communication skills you learned in therapy.

Since therapy is always a two-way process, it is very important to work on yourself outside of the office. For example, a therapist may ask you to keep a diary of emotions as you work on understanding and expressing them. If you are working with others, your homework may be to apply the new communication skills you learned in therapy.

How to prepare for the first appointment with a psychotherapist?

It is normal for you to be nervous before your first appointment. How to prepare for it in order to reduce stress levels and make psychotherapy more productive?

A few days before the first appointment:

1. State what is bothering you

No one requires you to clearly state your request to a psychotherapist in psychological language. But still try to determine what you do not like and what you would like to change. Try not to limit yourself to the phrases "I feel bad" or "I think I'm going crazy." What exactly are you feeling?

2. Think about what you would like to achieve

Think about what you would like to achieve

Psychotherapy does not have a universal goal. Each person imagines happiness, success and comfort in his own way. Imagine how life has to change for you to enjoy it. What would you like to get rid of, and what would you like to integrate? How will you know that it worked?

3. Find out everything you need to know about psychotherapy

It is better to dispel the myths in advance and find out how therapy works and what happens in it. Can help with this:

- I'm listening to you podcast is a real recording of therapy sessions with comments from a client and a psychologist.

- A guide to the areas of psychotherapy - to understand what areas exist, how they differ, with what and how they work.

- Blog and Instagram Alter - simple and honest about psychotherapy, psychology, relationships and self-care.

- The experience of your friends and family. Talk to them if they are willing to share: why they decided to see a therapist, how the work was structured and what was achieved.

A few hours before the appointment:

1. Do not use anything that changes consciousness

Not even "50 grams for courage." Sobriety is a very important condition of therapy.

2. Refresh something you would like to talk about

It is not necessary to have a clear plan. Just keep in mind the most basic things you think a therapist should know.

3. Tune in to talk

Try to relax and have an open conversation. You don't have to tell your therapist everything right away, but it's not in your best interest to shut yourself up either. If you find it difficult to talk about yourself, warn the specialist about it. He will adjust the pace and the therapy techniques used for you.

During your appointment

1. Track your condition

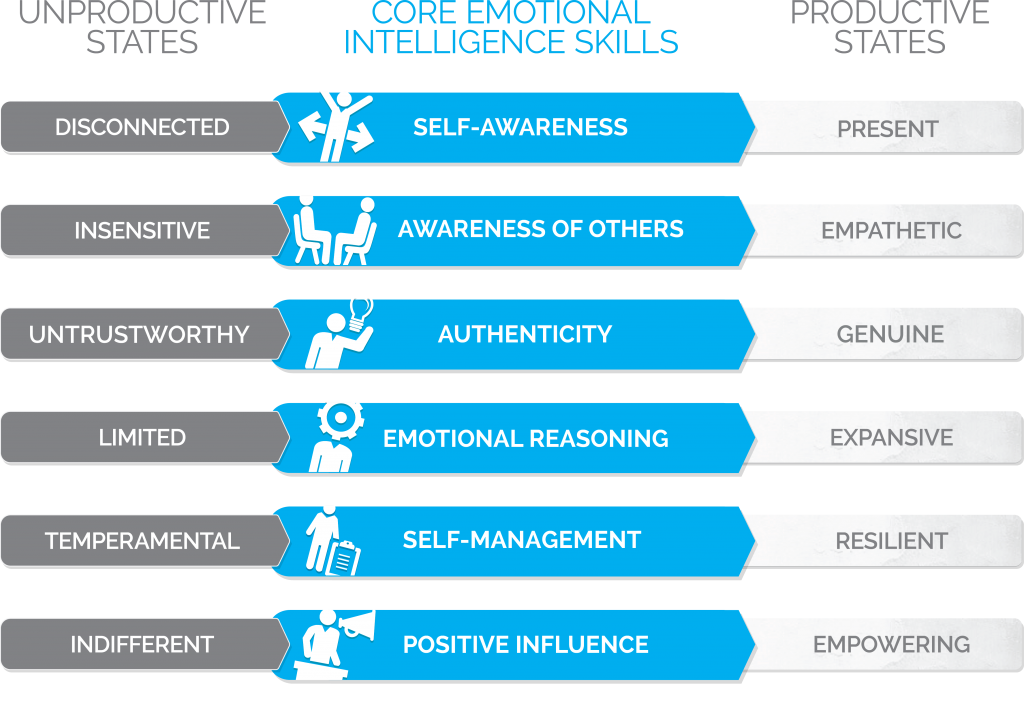

The best way to know if a specialist is right for you is to listen to yourself. How comfortable are you? Are there any feelings of shame, guilt, constraint? Do you want to share personal information specifically with this person, or is there some kind of internal block?

2. Give the therapist feedback

Give the therapist feedback

If you don't like something, talk about it directly. So far, this is not a direct signal that the specialist is not suitable. Perhaps he should slightly change the course of work and try other techniques. If everything is going well and you feel better, talk too. This will help you understand that you are on the right track.

Important: You may be tempted to hide something or lie to your therapist. This is a common reaction that can have many causes. Here we share tips on how to overcome that impulse and be more open.

Rate this article

[Total: 12 Rating: 4]

Share this post

Link copied to clipboard!

What does it mean to find your therapist? Rubric: Psychologists do not give advice

The question "how to choose a therapist?" implies not only formal criteria such as education, specialization and experience, but also a whole series of questions about how to understand that this is the right “my therapist”, how to distinguish ineffective therapy from temporary resistance or fear of change, and what role in choosing a therapist should play intuition and sensations? We asked these questions to Treatfield specialists.

There is a lot of talk and writing online about how important it is to “find your therapist”. But what is “your therapist” and “the right therapist”?

Psychotherapist answers Maya Kotelnitskaya

How to choose a psychotherapist with whom you are exactly on the same path? Before asking this question, you should form your request to a specialist or understand why you need a psychotherapist. For example, I work with anxiety, depression, crisis conditions, couples therapy, LGBTQ and supportive therapy for mental disorders, sexual problems, eating disorders. Certified psychotherapist in the Gestalt approach. You can always ask a specialist if he works with the condition that you would like to work on.

There are many ways to choose a psychotherapist, the main thing is your inner feeling from the person. If you are looking for a psychotherapist through social networks or websites, see if your values, interests match, in what areas he (a) works, what education, how many years of practice. Is the person suitable for you by age, appearance. And if your request is about relationships with parents, then the therapist may even look like one of them - and then this is a good option for work.⠀

Is the person suitable for you by age, appearance. And if your request is about relationships with parents, then the therapist may even look like one of them - and then this is a good option for work.⠀

Recommendations from friends in choosing a specialist do not always help. Their experience in therapy was useful to them, but this does not mean at all that a specialist is right for you. When you are praised by a therapist, you form a prejudiced attitude towards him, and high expectations do not help the beginning of therapy.

You will most likely find out if this is your specialist in the first introductory session. Always focus on inner comfort when communicating with a psychotherapist.

The Treatfield Team's Complete Guide to Choosing a Therapist: Guide. How to choose a psychologist?

How to choose a psychotherapist to find "your therapist"? That is, what else, besides the formalities (experience, education) to rely on? Is it necessary to trust irrational impulses like “I want a woman/man; to a peer / to an older one? What criteria will help you make a good choice?

Psychotherapist answers Elena Statnik

Choosing a psychotherapist is different from choosing any other specialist. This is because an important factor in successful psychotherapy is the relationship you develop with the therapist. The relationship between you and the therapist will be, to a large extent, the "medicine" that will move you forward in the process of psychotherapy.

This is because an important factor in successful psychotherapy is the relationship you develop with the therapist. The relationship between you and the therapist will be, to a large extent, the "medicine" that will move you forward in the process of psychotherapy.

For such a special relationship, the trust that gradually develops in the course of work is very important. When choosing a psychotherapist, it is important to ask yourself the question: do I want to trust this person, is there a desire to share personal information?

Initially, it's good if you have something in common that will help build a working alliance. It's great if there are common values, similar views on some things. This is not a prerequisite, because in the process of professional training, psychotherapists are trained to be non-judgmental and accept clients with all their characteristics and their individuality. But it can be a help at the beginning of cooperation.

It can often be attractive that the therapist's life stories are similar to personal experiences, it seems that the person will be able to understand me better if they have lived something similar. Such a coincidence can be useful if the therapist has worked through his personal situation in his own therapy - and then the scar that remains after the event is the experience that will help to be stable and empathic. The coincidence of life circumstances, in fact, is not at all a prerequisite for the successful work of the psychotherapist and the client. The main thing is that a specialist works with such requests. This can be clarified with a psychotherapist at the first meeting or even in the process of correspondence.

Such a coincidence can be useful if the therapist has worked through his personal situation in his own therapy - and then the scar that remains after the event is the experience that will help to be stable and empathic. The coincidence of life circumstances, in fact, is not at all a prerequisite for the successful work of the psychotherapist and the client. The main thing is that a specialist works with such requests. This can be clarified with a psychotherapist at the first meeting or even in the process of correspondence.

A video with the participation of a therapist can help in choosing a psychotherapist - listen to his speech, intonation, timbre. These seemingly minor things can make a big difference in whether or not working with a therapist is comfortable. It is good if the psychotherapist is a pleasant person for you to communicate with. You can listen to your feelings at the moment when you watch the video: if bodily you do not react with tension, anxiety, but rather the opposite, then this person is likely to suit you.

You can view the therapist's social media page, search for professional articles and posts. This can help to get a feel for the therapist's style, to understand the views on the therapy process, on what requests and topics it works with, with what clients.

Recommended reading: How is psychotherapy different from talking to a friend?

Attending a workshop, webinar, or lecture by a psychotherapist can be a great experience. This personal contact can give a more vivid picture of the person and help make a decision.

The cost of therapy is also an important factor in the choice. It should be tangible, but should not be too large. Otherwise, expectations from therapy will be excessive and this may affect the process of therapy.

Clients often look for a therapist of a particular gender or age. Indeed, in the course of our personal development and depending on life circumstances or difficulties, it may seem that this is the kind of therapist that is needed - a male therapist or a female therapist, an older or peer therapist. I think it is important to listen to such desires of yours, you can tell your therapist about such a selection criterion. Sometimes this helps to quickly delve into the problem, to outline it more clearly.

I think it is important to listen to such desires of yours, you can tell your therapist about such a selection criterion. Sometimes this helps to quickly delve into the problem, to outline it more clearly.

It is important to know about things like education, availability of therapy and regular supervision. A good sign will be calm and clear answers to these questions.

Many psychotherapists can offer several trial meetings where the therapist can make sure that the client's request is within his competence and, if suddenly not, redirect to another specialist. And the client will be able to decide in these few meetings whether everything suits him and whether he wants to continue working.

What exactly should not be in psychotherapy is judgment and evaluation of your personality, actions, feelings and thoughts, there should be no violence - emotional and physical, the psychotherapist should not seek any services from you, initiate or respond to your suggestion of friendship, romantic or sexual relations.

How do I distinguish between resistance in therapy and when the therapist is really not the right fit for me? If there is a feeling of “no, this is not my therapist”, what to do about it? How to understand that this is true, and not just avoiding difficult topics? Do I need to act immediately, stop therapy and look for a new one?

Psychotherapist answers Natalia Ivakhno

When at the first stage of your acquaintance with a psychotherapist it seems to you that he does not hear you, does not allow you to speak, immediately tries to interpret your words, if it is annoying that he uses a lot of terminology, it seems to you that he is trying in some way to increase his worth in your eyes if you feel that there is a conflict of beliefs - this is not "your" therapist. You turn to a psychotherapist and you have certain expectations. I want to find the perfect therapist who would always be on your side, fully share your views and protect you from all the evil in this world. But in the process it turns out that he is the same person, he does not have all the answers, and he can be wrong. Then doubts creep in. At this point, pay attention to how you feel around your therapist.

But in the process it turns out that he is the same person, he does not have all the answers, and he can be wrong. Then doubts creep in. At this point, pay attention to how you feel around your therapist.

In a situation where you have already been in therapy for some time, but still:

- you feel coldness and detachment from the psychotherapist;

- if you want to defend yourself all the time, if you do not understand what is happening and you were not given any explanation;

- your therapist is "great", charismatic and at first you experience euphoria from the fact that he paid attention to you, but over time it begins to tire and overwhelm;

- if you feel that they want to subordinate you to someone else's will, they require constant consent, and in case of refusal, the meetings turn into constant disputes and showdowns;

- if your point of view is not listened to and any manifestation of your principles is interpreted as a teenage rebellion;

- if you feel that the therapist is sexually attracted to you;

- if you do not feel safe.

And the most important thing is that during the meetings you tried to discuss all this with the therapist, but you understand that your feelings were not heard and the dialogue did not work, then there is no point in continuing the meetings.

But what to do if you have a good relationship with the therapist, everything seems to be fine, you see changes for the better, at certain stages you admit to yourself that the therapy works, and suddenly:

- you want to drop everything and run away, each meeting is more and more difficult;

- you start to be late and reschedule meetings;

- there is irritation from the fact that you have to pay for it;

- your dislike for the therapist becomes similar to the one you already experienced for other people;

- on the eve of meetings, you get sick, get injured;

- you stop trusting the therapist;

- you do not want to talk about important events and experiences for you.

In this case, most likely, we are talking about resistance to therapy. It is possible that you have encountered unpleasant aspects of your personality that are still lurking in the back of your mind..

It is possible that you have encountered unpleasant aspects of your personality that are still lurking in the back of your mind..

Recommended reading: When and how to end psychotherapy

Resistance in psychotherapy is a defense mechanism that, like Cerberus, guards the entrance to our personal hell. When we are on the verge of any change, there is always an objective concern about what's next. After all, even changes for the better are stress that we unconsciously try to avoid. And if you put in a lot of effort to overcome something, and suddenly some event made you relive your previous feelings, this is perceived as a collapse. For example, you learned to internally resist non-constructive criticism and for a certain time made progress in this, but at some point an insignificant remark makes you experience, as before, insecurity and shame - many feelings and experiences arise: guilt and anger, confusion, disappointment, resentment, apathy, resentment, suspicion. It begins to seem to you that all the work done is useless, the therapist does not understand anything and does not know how, and it will never get better. The question arises what to do next.

It begins to seem to you that all the work done is useless, the therapist does not understand anything and does not know how, and it will never get better. The question arises what to do next.

In such a situation, it is advisable to stop the attempt to escape and share your feelings with the therapist, to have an open conversation about your feelings. These periods of decline are a natural part of the psychotherapy process. They will be repeated in therapy and in life. But each time the intensity of negative experiences will decrease and it will be much easier to climb up.

To change something in yourself, you need to do it yourself. The therapist cannot do your job, he can only be in the role of a guide, guided by your desires and possibilities, and be a support in difficult, painful situations.

By accepting the psychotherapist's imperfection, realizing it, you learn to accept yourself with your mistakes, fears, complexes.

You learn to trust yourself, and the therapist will help you go through your own feelings, you will be able to look at yourself from the other side, in a new way. After all, do not forget that psychotherapy is a relationship, and you also need to work on them. But when to leave this relationship is up to you.

After all, do not forget that psychotherapy is a relationship, and you also need to work on them. But when to leave this relationship is up to you.

How many sessions do I need to understand that the therapist is right for me and I managed to “find my therapist”? Is it possible to understand this immediately in the first session? Or does it take a long time? What feelings and criteria to look at to understand?

Psychotherapist answers Svetlana Lobanova

How many sessions do you need to understand that a therapist is suitable? At least one. If after the first session you don’t want to close your laptop / run out of the office and never see this person again, then the therapist is at least “not suitable” for you. I always ask my clients this question at the first session: “would you like to run away and forget that we even met”? If not, then I propose to take a conditional period of five sessions for yourself, during which you can look at each other, listen to yourself and understand whether I can be useful as a therapist and whether there is a desire to build a relationship with me. This is my individual and very conditional period of time, it can vary with different therapists. Psychotherapy is all about relationships, and relationships take time to build. Yes, this may sound strange - therapy and relationships, what's the connection? But how a client builds a relationship with me is the only real information I get about him. Everything else - stories, stories that the client brings me - all this has already passed through the filter of his perception, and this is a product of him, the client, consciousness and subconscious. Which is also very important and sufficient for counseling, but not enough for therapy.

This is my individual and very conditional period of time, it can vary with different therapists. Psychotherapy is all about relationships, and relationships take time to build. Yes, this may sound strange - therapy and relationships, what's the connection? But how a client builds a relationship with me is the only real information I get about him. Everything else - stories, stories that the client brings me - all this has already passed through the filter of his perception, and this is a product of him, the client, consciousness and subconscious. Which is also very important and sufficient for counseling, but not enough for therapy.

One can decide at the very first session that this wonderful person opposite is the one whom I have been looking for for so long and finally found. Attentive, listening, accepting and non-judgmental! One that has never been seen before in life. And it's wonderful! Transference (an unrealistic representation of a person based on one's own desires, needs, and fantasies) is an excellent basis for forming a therapeutic alliance. This is an important part of successful therapeutic work: the client's ability to trust the therapist and cooperate to establish and achieve therapy goals.

This is an important part of successful therapeutic work: the client's ability to trust the therapist and cooperate to establish and achieve therapy goals.

But the transfer does not always happen in the first sessions, and in all the others too. Often the therapist is initially seen as a meticulous and cold-hearted doctor who needs to “get it straight” without hiding anything. And this can cause some discomfort, which I, as a client, choose to ignore from the idea that "the therapist needs to be told everything how." But a psychotherapist is not a doctor, not a pathologist. A psychotherapist is a person just like you, only trained to notice the nuances that are usually not noticed in the usual, everyday life. For example, pay attention to the fact that you are currently revealing more intimate details of your life than the situation requires. And not to shame you, not to blame, but just to notice and give you the opportunity to decide how to deal with it further.

A "good" therapist can explain things you don't understand in understandable terms, gather your disparate thoughts into a clear structure. And if suddenly he can’t, then this is not a “bad” therapist, but, for example, confused (like any living person, the therapist can be confused), or “not yours”.

And if suddenly he can’t, then this is not a “bad” therapist, but, for example, confused (like any living person, the therapist can be confused), or “not yours”.

"Your" therapist is someone with whom you manage to get along, literally: you understand what he/she is talking about, and he/she understands what you are talking about. And if you suddenly do not understand, then you are free to clarify and ask again.

Yes, sometimes you and your therapist don't get along. You may not like the manner of speech, the way of communication, the voice, the appearance, the metaphors that the therapist uses. You may just be "uncomfortable". And you have the right both to clarify all these points, and to refuse the services of a particular specialist.

To sum up, “your therapist” is a person with whom you are comfortable and safe to talk about different, personal, intimate things. And only you can decide how long it takes to trust someone. There is no right or wrong time: you can find “the right one” the first time, or you can review many different specialists or stop therapy after a couple of sessions.