Gifted children autism

Gifted, On the Spectrum, or Both?

A popular young adult novel character named Penelope Bunce often pulls out a chalk board when solving tough problems and starts by creating two lists: What We Know. What We Don’t Know.

When it comes to the connection between giftedness and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), it is important to understand that the latter column far exceeds the former. The DMS-5 continues to adjust its diagnostic criteria for ASD, and there is also no universal definition for giftedness. The scope of this article isn’t meant to be a scholarly review of the literature concerning autism, giftedness, and their intersections but will instead focus on summarizing how the two overlap and what parents and educators can do to help these children thrive.

Consider the following brief description for illustration:

A ten-year-old child in their local public school excels at computer programming and has a keen interest in learning advanced coding languages like Python. However, they don’t socialize with others at recess and seems to struggle to communicate when forced to do group work in class.

This child may be gifted and finding it difficult to meet like-minded peers who share their interest or work in groups where they have to wait for a long time for others to arrive at the same answer this child learned so quicky. The child may be autistic and able to excel in their subject of interest but not as equipped for social interactions that require reciprocity. The child may also be both gifted and autistic, often referred to as twice-exception (or 2e for short), where their asynchronous profile allows them to succeed in some tasks while being challenged by others. They may excel in academics but perhaps the sensory overload of recess and group projects causes them to seemingly withdraw. To add to the label confusion, a parent, an educator, and a clinician may all place different emphasis on different aspects of this child’s profile.

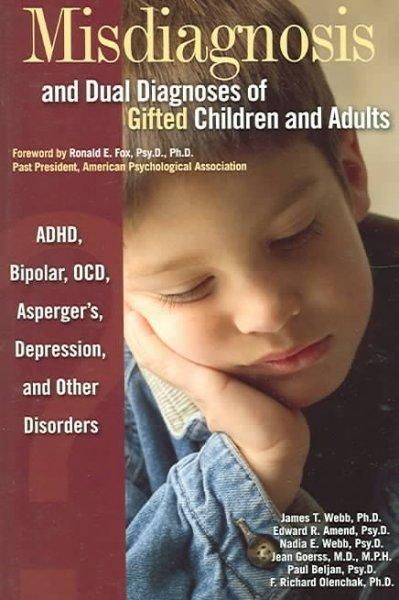

Many readers may already be having strong reactions. It is understandable given the history, stigma, and ongoing debates that circle around both the gifted and ASD communities. Parents of gifted children may worry that their child will be mislabeled as ASD, perhaps because of a teacher’s misunderstanding of gifted characteristics (and/or ASD characteristics). Parents of children who are identified as ASD may resent how this label has been used to pathologize, rather than embrace neurodiversity. Parents of children who are both gifted and autistic often feel that they can’t get the benefits of either label, such as access to advanced learning opportunities or scaffolding in school when their child needs extra support.

It is understandable given the history, stigma, and ongoing debates that circle around both the gifted and ASD communities. Parents of gifted children may worry that their child will be mislabeled as ASD, perhaps because of a teacher’s misunderstanding of gifted characteristics (and/or ASD characteristics). Parents of children who are identified as ASD may resent how this label has been used to pathologize, rather than embrace neurodiversity. Parents of children who are both gifted and autistic often feel that they can’t get the benefits of either label, such as access to advanced learning opportunities or scaffolding in school when their child needs extra support.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is considered a developmental condition that results from a brain-based difference. It is broadly defined but mainly focuses on issues of social and communication skills, as well as some observable behavioral differences, often referred to as “restricted and repetitive behaviors,” such as rocking. Professionals consider the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which includes behavioral checklists and severity levels, to help identify individuals.

Professionals consider the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which includes behavioral checklists and severity levels, to help identify individuals.

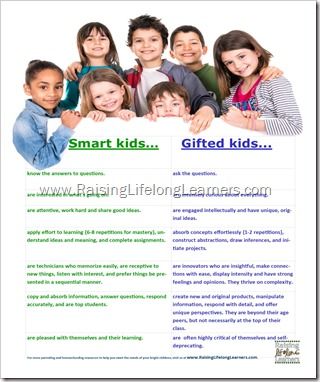

Giftedness is also considered a brain-based difference that is broadly defined. It is commonly characterized by high intelligence, creativity, and/or achievement. Diagnosing giftedness often involves above-level testing, IQ tests, or standardized achievement tests. Gifted behavior checklists are also frequently included in gifted identification.

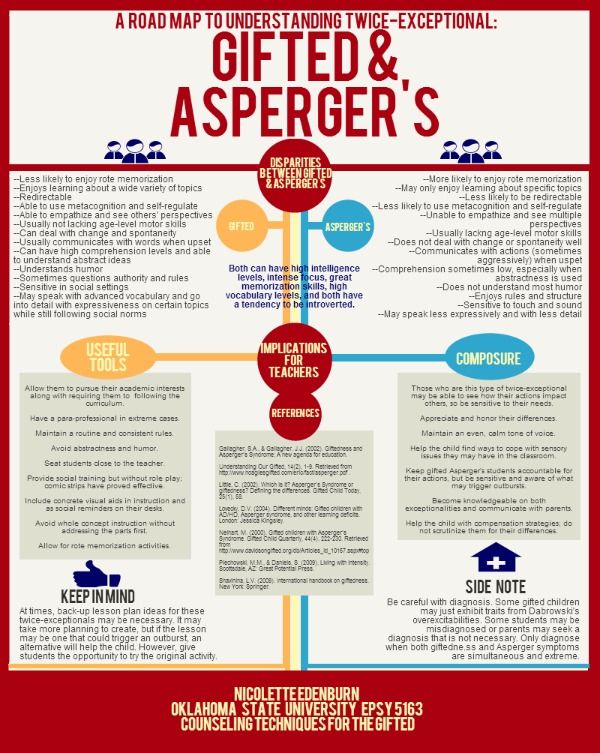

It should be noted that highly gifted children are not always well-adjusted, high-achievers. Highly gifted children are often described as intense or over-excitable and can present with sensory issues and executive functioning issues, much like those described in students who are identified with ASD. In addition, both students who are gifted or have ASD may struggle with social interactions. As the table below demonstrates, there are several identifying traits that both profiles share.

Shared Characteristics on Behavior Checklists for Both Giftedness and ASD

| Signs of Giftedness *Taken from NAGC & the Davidson Institute | Signs of Autism Spectrum Disorder *Taken from the CDC |

|---|---|

| Enthusiastic about unique interests | Has obsessive interests |

| Difficulty connecting with same-age peers | Has trouble relating to others or not have an interest in other people at all |

| High expectations of self and others, often leading to feelings of frustration | Has trouble understanding other people’s feelings or talking about their own feelings |

| Rigid rule-following at play time | Does not play “pretend” or interactive games |

| Issues with executive functioning | Has trouble adapting when routines change |

| Greater sensory sensitivity (see GRO) | Has unusual reactions to the way things smell, taste, look, feel, or sound |

| Impulsive, eager and spirited | Hyperactive, impulsive, and/or inattentive behavior |

How to Tell the Difference Between ASD and Giftedness?

While the examples above may not seem like an exact 1:1, it becomes difficult to disentangle when characteristics like “an intense interest in a peculiar subject” or “difficulty with social interactions” would fall under giftedness or ASD. What does become clear is that even shared traits are described differently depending on which context is considered. When referring to giftedness, words like “enthusiastic” are used to describe the intensity, while when referring to ASD, a behavior checklist might use a word like “obsessive.” Deficits based language often has its roots in educational frameworks which use performance levels to determine the flow of important resources like programming, in-class aid, and funding. However, it should be noted that many within the ASD community find the language used to describe them as ableist and further stigmatizing.

What does become clear is that even shared traits are described differently depending on which context is considered. When referring to giftedness, words like “enthusiastic” are used to describe the intensity, while when referring to ASD, a behavior checklist might use a word like “obsessive.” Deficits based language often has its roots in educational frameworks which use performance levels to determine the flow of important resources like programming, in-class aid, and funding. However, it should be noted that many within the ASD community find the language used to describe them as ableist and further stigmatizing.

Both giftedness and autism fall on a spectrum, so while there may be individuals who clearly fit into one box or another, some behaviors might be more ambiguous and require additional information, context, or professional opinions. Just like in our discussion of giftedness and ADHD, it should be noted that there is no definitive test to identify either. Instead, understanding your child’s full learning profile will require a careful and thorough assessment of the whole child by a trained professional, particularly by someone who has worked with both gifted and ASD children.

Neuroscience research is ever-evolving, and while there is not yet one fail-safe method for identifying when a student is gifted, on the spectrum, or both, several professionals in the field have observed key areas that might help others identify ASD when the situation is not a clear-cut case.

Considering the motivation or context behind behaviors that may look the same on the surface is one tool professionals use when considering a possible diagnosis. For example, difficulty relating to age-peers is often cited as a shared characteristic. However, gifted students may have this difficulty because they have higher expectations of their peers, wish to dive deeper into topics, or desire a more mature form of friendship (see Miraca Gross’s article, “Play Partner or Sure Shelter”). Students on the autism spectrum often desire social connection, but may struggle interpreting facial expressions, expressing emotions, or engaging in tasks with reciprocity.

Another key indicator when considering an evaluation for ASD is the severity of symptoms and their impact across all aspects of life. As Dr. Melanie Crawford points out in her article, when symptoms create prolonged emotional distress and prevent students from engaging in regular tasks of daily life, it may be time to consult a professional. Examining the intensity of symptoms may also help professionals identify ASD in students who are gifted. For example, Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC, describes her experience investigating how, in some cases, intensity can’t always be “explained away” by giftedness alone.

As Dr. Melanie Crawford points out in her article, when symptoms create prolonged emotional distress and prevent students from engaging in regular tasks of daily life, it may be time to consult a professional. Examining the intensity of symptoms may also help professionals identify ASD in students who are gifted. For example, Emily Kircher-Morris, LPC, describes her experience investigating how, in some cases, intensity can’t always be “explained away” by giftedness alone.

How to Support Students Who Are Identified as Both Gifted and on the Autism Spectrum?

There are great resources for gifted children as well as resources for children who have been identified as ASD. When a student is twice-exceptional, with both giftedness and ASD, it may be difficult to navigate which options work best for your child. As Dr. Ed Amend suggests in this article, it is “the needs of a child, not the specific diagnosis or identification category, [that] are supposed to drive the interventions. ” Because giftedness and ASD can manifest in many different ways, it is important that educators, parents, and professionals follow the lead of the student to support their areas of strength and provide scaffolding in areas where student has deficits.

” Because giftedness and ASD can manifest in many different ways, it is important that educators, parents, and professionals follow the lead of the student to support their areas of strength and provide scaffolding in areas where student has deficits.

While there is still much we don’t know about the overlap of giftedness and ASD, what we do know are some ways to start supporting these students. A few common tips include the following:

- If your 2e child has significant areas of challenge that affect their ability to participate in classroom activities, social opportunities, or pursue their interests, a formal assessment may be the first step so that their full profile is understood. Try to locate individuals who have experience with both gifted and 2e students through lists like our Gifted and 2e Testers & Therapists map or Hoagies’ Gifted’s “Psychologists Familiar with Testing the Gifted and Exceptionally Gifted.”

- Use a 504 Plan or IEP to its full extent. While many support plans focus on school performance and can assist with challenge areas like written language, they can also aid with classroom transitions, social skills, and incorporate strategies for emotional regulation.

- Even if your 2e student struggles with social situations, it doesn’t mean they don’t want to connect with like-minded peers in their own way. One way to do this that also aids their intellectual development is by enrolling them in non-competitive clubs, summer programs, or other programs that focus on a specific area of interest like coding, history, or math.

No child should think of themselves as “deficient” because of who they are. It can be difficult for some families to initially accept a 2e label of gifted and ASD because of the history of stigma that has surrounded the ASD community. However, a diagnoses can be helpful when it comes to accessing tools and support systems that the student might not otherwise have, such as an IEP, access to a community of like-minded peers, resources to decrease stress, and a fair and appropriate education that allows the student to explore their areas of interest. In a neurodiverse world, there are many examples of successful individuals who could be described as 2e – there’s no reason why your student can’t thrive too!

Additional Resources on the Intersections of ASD and Giftedness

Autism and ADHD | A Mom’s Story About Kids with Multiple Diagnoses | Understood – For learning and thinking differences

Gifted and Talented Students on the Autism Spectrum: Best Practices for Fostering Talent and Accommodating Concerns | (researchgate. net)

net)

Autism –vs- Giftedness: A Neurobiological Perspective – Resources by HEROES (njgifted.org)

Interview with Marianne Kuzujanakis on Misdiagnosis – Davidson Institute (davidsongifted.org)

Twice Exceptional – Smart Kids with Learning Differences – Davidson Institute (davidsongifted.org)

Tips for Parents: Autism Spectrum Disorders Q & A – Davidson Institute (davidsongifted.org)

Giftedness and Autism: What to Know

Autism and giftedness can go hand in hand. Twice-exceptional kids have great ability, but they also face certain challenges.

Giftedness and autism share some qualities, like intellectual excitability and sensory differences. Some kids have these qualities because they’re both gifted and autistic.

If your child is nonverbal and shies away from eye contact and touch but can play piano concertos after hearing them only once, it’s easy to spot the coexistence of autism and giftedness.

It’s usually not that obvious, though. Not all autistic kids avoid eye contact or shun hugs, and many are great conversationalists. Meanwhile, only a few gifted kids are prodigies with exceptional recall.

Not all autistic kids avoid eye contact or shun hugs, and many are great conversationalists. Meanwhile, only a few gifted kids are prodigies with exceptional recall.

It’s more likely you’ve noticed that your child has some impressive, detailed knowledge about a focused interest, plus they show bouts of emotional intensity or sensory issues that are common in gifted children.

Giftedness is extraordinary ability, high IQ, or both. It’s a neurological sensitivity that changes the way a person experiences the world.

Gifted children:

- learn faster and more easily

- get bored very quickly

- feel emotions and physical sensations more intensely

- remember things more acutely

- think and reason with increased complexity

- need challenge, change, and novelty

- experience social isolation

- are detached from social norms

The IQ level that is considered gifted, or having higher intellectual abilities, is 130 or higher. This is within the top 2% of the population.

This is within the top 2% of the population.

IQ isn’t the only factor used to assess cognitive level because IQ tests can measure only your functioning at the time of the test. If you are ill or distracted by stress or troubling thoughts, you might not score as well as you could.

This is why psychologists perform full assessments and not only IQ tests when they identify giftedness.

Giftedness and high scholastic achievement are not the same. With discipline and good study habits, a student with an “average” IQ can earn excellent grades in school.

Meanwhile, a gifted student can struggle in school and underachieve. This is often because they are:

- depressed

- frustrated

- anxious

- not interested in the subject being taught

Gifted kids aren’t always very motivated by grades. Instead, they may care more about the things they consider relevant, important, or interesting.

Without early acceleration, gifted children may experience lower grades as they get older. If their early schoolwork is too easy, they don’t have the opportunity to learn study skills and work ethic. As the difficulty level of subject material increases, their grades can drop.

If their early schoolwork is too easy, they don’t have the opportunity to learn study skills and work ethic. As the difficulty level of subject material increases, their grades can drop.

Other differences between gifted students and high achievers include:

- High achievers develop evenly as they mature, whereas gifted kids develop in an uneven way, with some abilities far surpassing others.

- Gifted people have more sensitivity and emotional intensity than high achievers.

- High achievers may be more extroverted than gifted people, who are more likely to be introverts.

Some school gifted and talented programs base entrance criteria on achievement rather than intelligence testing. Many also include a larger portion than the top 2%. This means that some students in these programs may be high achievers who aren’t gifted.

In the United States, 1 in 59 children is autistic. About 70% of autistic people have an intellectual disability, which means they have an IQ lower than 70. The remaining 30% have intelligence that ranges from average to gifted.

The remaining 30% have intelligence that ranges from average to gifted.

Autism and intelligence are two separate characteristics. A person can be autistic with any level of intelligence.

But if your child is gifted and autistic, it can seem like the two are connected.

Both giftedness and autism share traits like:

- idealism

- perseveration, an intense focus on one topic

- high learning drive

- sensory differences

- a vivid imagination

- difficulty sitting still

- challenges with emotional regulation

- niche areas of expertise

- logical and precise thinking

- divergent thinking

An autistic person who’s also gifted is considered “twice exceptional” (2e).

Giftedness and autism are types of exceptionalities. When children are both intellectually gifted and have a neurobiological difference, motor skills issue, or learning disability, they’re 2e kids.

Examples of 2e include:

- gifted autism

- gifted and dyslexic

- gifted with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- gifted with dyspraxia

Because autism and giftedness exist separately, it’s possible to have a gifted child with more pronounced autistic traits who may benefit from more support at home and at school. You can also have a fully verbal and self-sufficient autistic child with a typical IQ who isn’t twice exceptional.

You can also have a fully verbal and self-sufficient autistic child with a typical IQ who isn’t twice exceptional.

Giftedness can make up for other issues and reduce their impact. For example, a 2e child who has trouble concentrating may compensate with quick thinking and still learn in school.

This may sound like a good thing, but it can cause barriers to diagnosis, which can delay support.

Giftedness can also intensify issues. A twice-exceptional child might fixate on something they can’t change longer than a nongifted child would. Or a 2e child might think of more points to use in an argument than an autistic child with average intelligence.

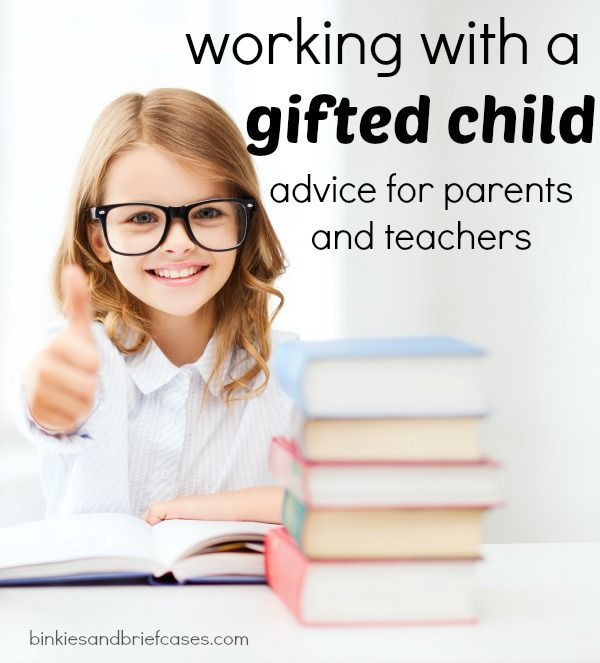

It’s OK if you don’t always understand your gifted autistic child. You can still help them thrive and make the most of their talents.

It helps to see the whole child and not just the issue you’re trying to address.

Giftedness can hide challenges. An issue that seems minor might be like a mostly hidden iceberg with more beneath the surface than you can see.

Effective communication is vital. You can foster this skill by actively listening to and observing your child. Wait for them to talk, and give them time to think.

It’s a good idea to pay attention to what their behavior is saying. For example, if your child yells angrily, they might feel fatigued, frustrated, or stressed rather than anger.

School strategies to help your 2e child include:

- Consider finding activities outside of school to build on strengths, increase confidence, and find new friends.

- Try to locate assistive technology.

- Consider role play coaching for social skills scenarios.

- If you can, advocate for a reduced homework load and more time for assignment completion.

- Consider teaching planning, organizations strategies, and time management.

- If you can, arrange for an in-school homework buddy.

Parenting a 2e child can seem like a daunting task, but the rewards make it worthwhile. Not only does your child have exceptional intellect, but they also have a refreshingly atypical perspective.

It can be helpful to reach out to other parents in the autism community and find others with 2e children like yours. You can collaborate in your shared adventure of raising extraordinary children.

If you’re looking for helpful resources, here are a few to start:

- Davidson Institute

- National Association for Gifted Children

- Supporting Emotional Needs of the Gifted (SENG)

- Mensa for Kids

- Hoagies’ Gifted Education Page

- Project 2e-ASD

Doubly special children can be very different. Below are three examples of such children and what challenges they may face in school.

Doubly special children can be very different. Below are three examples of such children and what challenges they may face in school. 1. Disability is ignored due to talent

Shanika is in high school. She can read and complete assignments at a level that is beyond the ability of most students her age. She is fond of fashion and dreams of starting her own jewelry company.

Intelligence test results show that she is gifted, so she was assigned to the Gifted Support Program. However, she has never received services for her disability, she has not even been tested for the problems she has.

She has a serious attention deficit, which is why many teachers call her lazy, they say that she does not try. She was even accused of deliberately avoiding high scores. All this, of course, is unfair and does not reflect what is happening to her.

2. Giftedness ignored due to disability

Jacob is 12 years old. He has difficulty with reading, handwriting and social skills. He is very athletic and dreams of becoming a coach or a physical education teacher.

He is very athletic and dreams of becoming a coach or a physical education teacher.

He is enrolled in a special education program due to his difficulties but does not receive help due to his giftedness. He is annoyed by the material taught in his class. Sometimes he even claims that school teachers "talk like fools."

As a result, he is often distracted in class, including exhibiting problem behavior. Teachers consider him headstrong, stubborn and evil, in their opinion, he specifically tries to piss them off. He, in turn, would just like to perform more difficult learning tasks, but it is difficult for him to convey this idea to teachers.

3. Disability and giftedness cancel each other out

Caroline is in fourth grade. She has never received services for either gift or disability, and neither her problems nor her talents are known. Parents and teachers do not suspect anything, since in general her results are average, and she does not stand out from her peers.

During most lessons she is too bored, the material seems extremely simple to her. But she has problems with social communication, so she cannot convey these experiences to other people. It was always very difficult for her to put her thoughts and emotions into words, although her speech development in general corresponds to the age norm. She loves to draw and dreams of one day working in the fashion industry.

Conclusion

Unfortunately, there are practically no schools, classes or programs specifically for doubly special children. Therefore, it is important for us to draw attention to this problem and seek services for such students. There are approaches to help people with disabilities and there are approaches to help intellectually gifted students, but what services are best for those in both groups?

If doubly special students find themselves in a class or school for gifted children (or even just in a general education class of a general education school), then with a high probability teachers will not be ready for their problems, because of a misunderstanding, children will be accused of laziness and malicious behavior. If such students end up in a special class or school, learning tasks will be too easy for them, it will be too difficult for them to maintain concentration, they may develop problem behavior.

If such students end up in a special class or school, learning tasks will be too easy for them, it will be too difficult for them to maintain concentration, they may develop problem behavior.

We must improve student ability and skill testing to identify doubly special children, because the sooner they are known, the better.

Inclusive rebus: artistic talent, cognitive style, autism and paleontology

Currently, pedagogy is turned towards studying the specific educational needs of "special" children in order to make the learning environment as comfortable, accepting and developing as possible. The last concept is the key, because a child with learning difficulties can show remarkable talent - in music, art, dance, languages, etc. The task of the education system is not only to correct the gaps as much as possible, but also to help the child become successful in those areas in which nature has gifted him.

Children with autism often show amazing talents in this regard. Over the past 15 years, many scientists around the world have been absorbed in the question of why autism spectrum disorders are associated with the phenomenon of savantism - a specific giftedness (up to genius). And there is some interesting data already.

Over the past 15 years, many scientists around the world have been absorbed in the question of why autism spectrum disorders are associated with the phenomenon of savantism - a specific giftedness (up to genius). And there is some interesting data already.

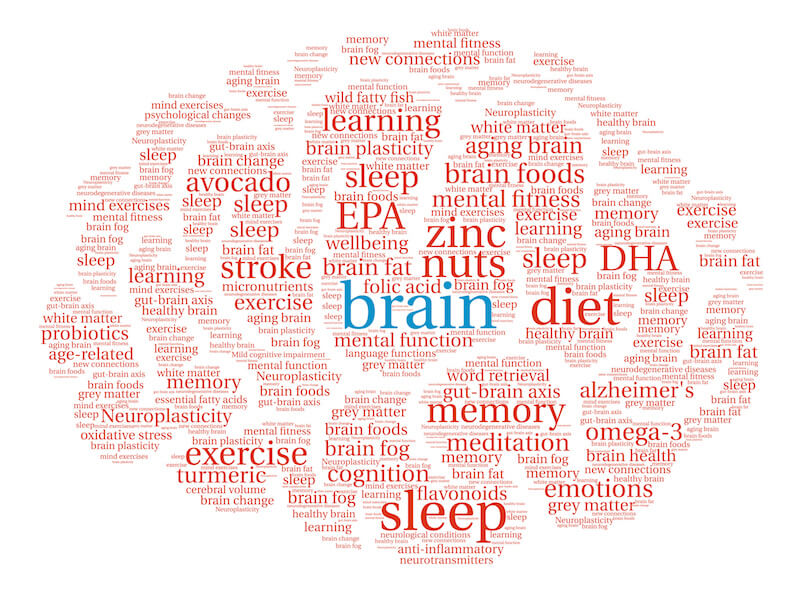

Research shows that many people with autism have a tendency to process information locally, which leads to a highly specific perception of the world around them. For example, most people tend to perceive visual images as a whole - as a single object. Looking at a bicycle, we quickly catch the characteristic features and understand that we have a bicycle in front of us. The same with any other object. A child with autism is often inclined to see a lot of details - and he remembers them firmly and for a long time. But at the same time, he may not understand that there is a bicycle in front of him. This is the case when the child "does not see the forest for the trees."

This seems to be the mechanism behind the incredible artistic talents of some children with autism. Their drawings (starting from the age of 2 years old!) are distinguished by detail (and often from memory), attention to foreshortening, perspective, three-dimensional image. In other words, we can talk about a high degree of realism. At the same time, the image may often be incomplete, there is no integrity, and work with color is often ignored.

Their drawings (starting from the age of 2 years old!) are distinguished by detail (and often from memory), attention to foreshortening, perspective, three-dimensional image. In other words, we can talk about a high degree of realism. At the same time, the image may often be incomplete, there is no integrity, and work with color is often ignored.

Research shows that on very rare occasions, typical artistically gifted children show a tendency to local processing. Their drawings are not very detailed, but the depicted image is fairly quickly guessed by the general characteristics. At the same time, rare young artists who are prone to hyperrealism often differ from their peers in deficits in the social and communicative sphere, as well as an obsessive, all-consuming love for drawing (a tendency to stereotypical and repetitive activities). And these are all specific features of autism.

In other words, from a drawing of a person one can quite reliably understand his cognitive style. And often local processing of information is a characteristic feature of people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

And often local processing of information is a characteristic feature of people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

However, the most interesting data were presented by archaeologists. After analyzing many samples of European rock art of the late Paleolithic era, scientists noted their typical characteristics - focusing on details, components to the detriment of the integrity of images, typical layering of images, ignoring color, amazing plasticity of drawings - that is, taking into account angles, volume, perspective. These are all the features that distinguish the artistic creativity of gifted children with ASD. Scientists unequivocally reject the version that such drawings may be associated with the use of any psychoactive substances by our ancient ancestors, because. none of them can significantly affect a person's cognitive style. Local processing is born with a person. And often this is a person with autism. And apparently, autism has been around for many, many millennia.