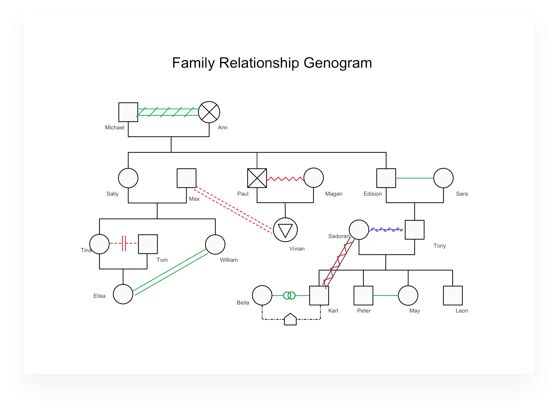

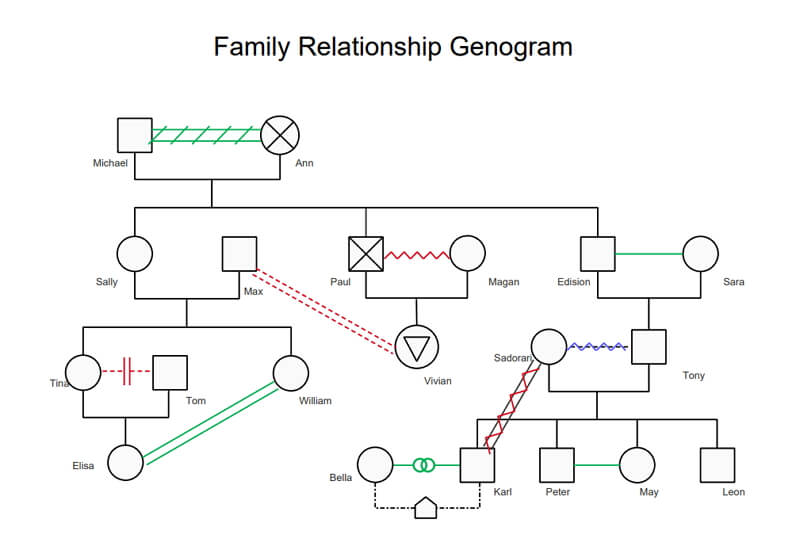

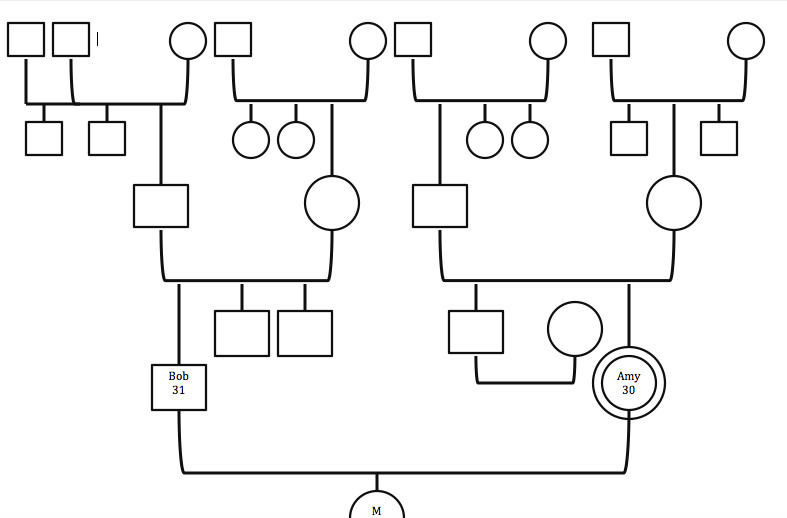

Genogram examples of 3 generations

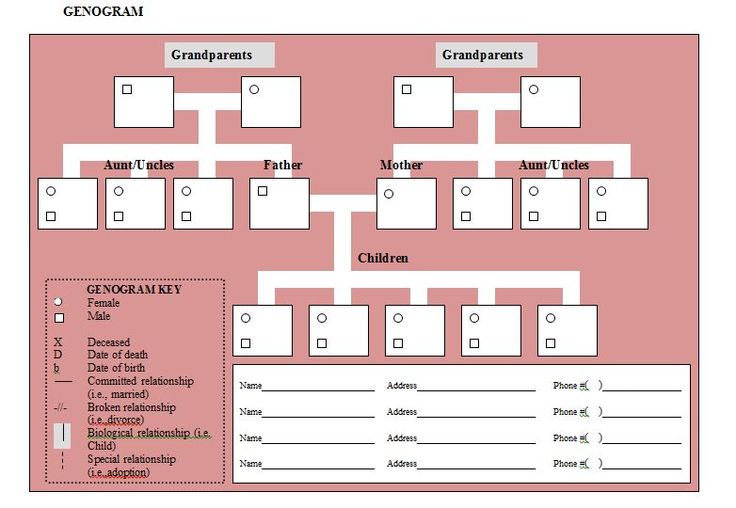

3 Generation Genogram

Browse Categories Create

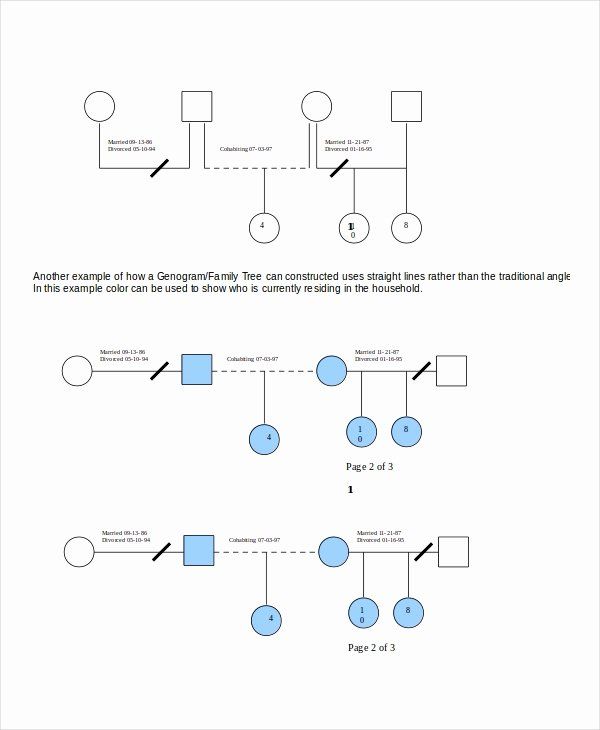

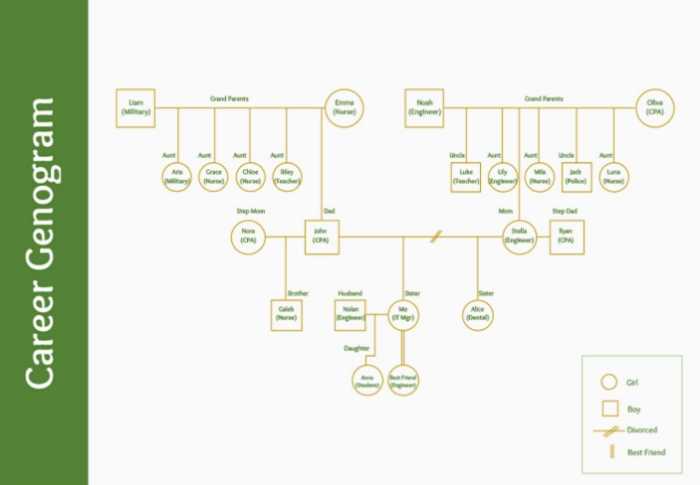

Create a 3-generation diagram to represent your family tree and see patterns and commonalities emerge.

Create

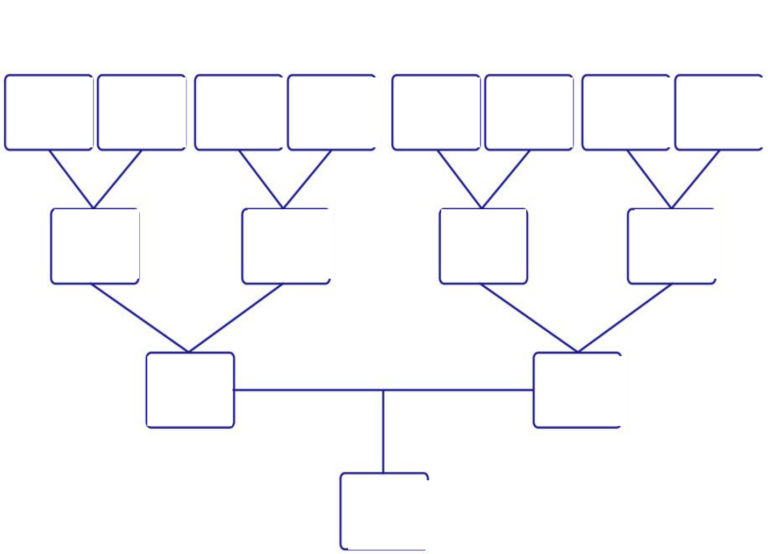

A 3-generation genogram is a graphical representation of a family tree that goes back three generations. It usually includes the grandparents, their children, and their grandchildren. With this diagram, families can see patterns that span multiple generations. This can be helpful in identifying issues that may be affecting the family as a whole. It can also be used to track health information. This can be useful in spotting trends that may be genetic in nature. Knowing this information can help families make informed decisions about their health. The 3-generation genogram can also be used to track relationship patterns. This can help families understand why certain relationships are the way they are.

It can also help families work through issues that may be causing conflict. A 3-generation genogram is a powerful tool that can be used in many different ways. It is a valuable tool for any family who wants to understand their history and their relationship patterns. To create this type of diagram, you will need to gather information about your family. This can be done through interviews, surveys, or other research methods. Once you have this information, you can begin to create the genogram. There are a few things to keep in mind when creating a 3-generation genogram. First, make sure to include as much information as possible. This will make it more useful for families. As much as possible, try to get the full names, dates of birth, and other important information. If you can't get this information, don't worry. You can still create a useful genogram with the information you do have. Once you have gathered all of the information, you are ready to begin creating the genogram. Start by drawing a horizontal line for each generation.

Then, add the names of the family members to the appropriate generations. Be sure to use a consistent format. This will make it easier to read and understand. Finally, consider using software or an online editor like Venngage to create the genogram. This can help you create a professional-looking diagram that is easy to share with others. After you have added all of the names, you can begin to add additional information. This can include relationship status, occupation, education, and anything else that you think would be helpful. Once you have finished adding all of the information, you are ready to share the genogram with your family. You can do this by emailing it, printing it out, or sharing it online. Creating a genogram can be a helpful way to understand your family's history and relationships. By including as much information as possible and using a consistent format, you can create a valuable tool for any family. With Venggage's templates and easy-to-use editor, you can create a genogram in minutes.

Then, add the names of the family members to the appropriate generations. Be sure to use a consistent format. This will make it easier to read and understand. Finally, consider using software or an online editor like Venngage to create the genogram. This can help you create a professional-looking diagram that is easy to share with others. After you have added all of the names, you can begin to add additional information. This can include relationship status, occupation, education, and anything else that you think would be helpful. Once you have finished adding all of the information, you are ready to share the genogram with your family. You can do this by emailing it, printing it out, or sharing it online. Creating a genogram can be a helpful way to understand your family's history and relationships. By including as much information as possible and using a consistent format, you can create a valuable tool for any family. With Venggage's templates and easy-to-use editor, you can create a genogram in minutes. You can also instantly share it with your family and loved ones. Start by selecting a template, then add your information and share it with your family. You can also download it as a PDF or image file to keep for your records. Simply sign up for a free account and start creating your genogram today.

You can also instantly share it with your family and loved ones. Start by selecting a template, then add your information and share it with your family. You can also download it as a PDF or image file to keep for your records. Simply sign up for a free account and start creating your genogram today.

See More Related Templates

Genogram Examples - GenoPro

Related Pages

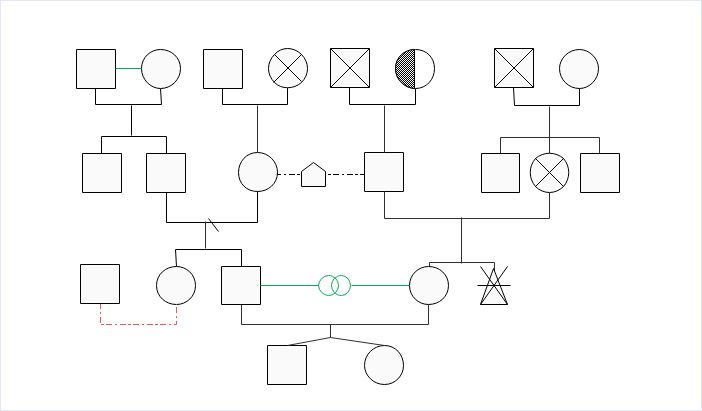

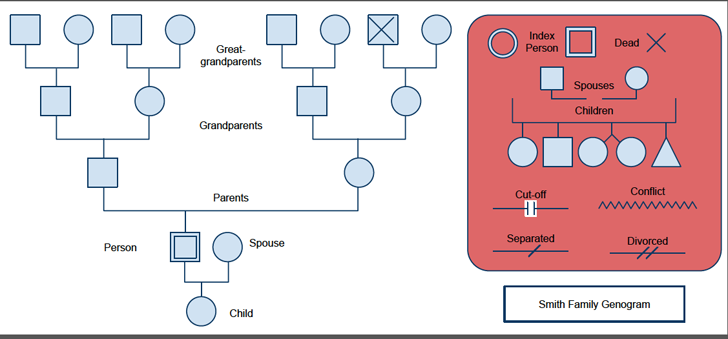

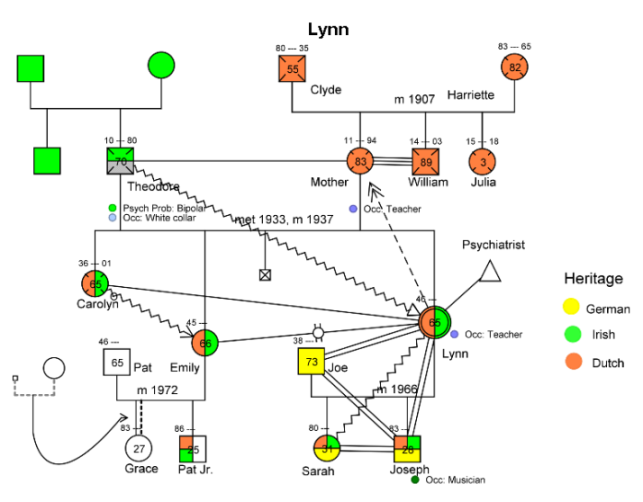

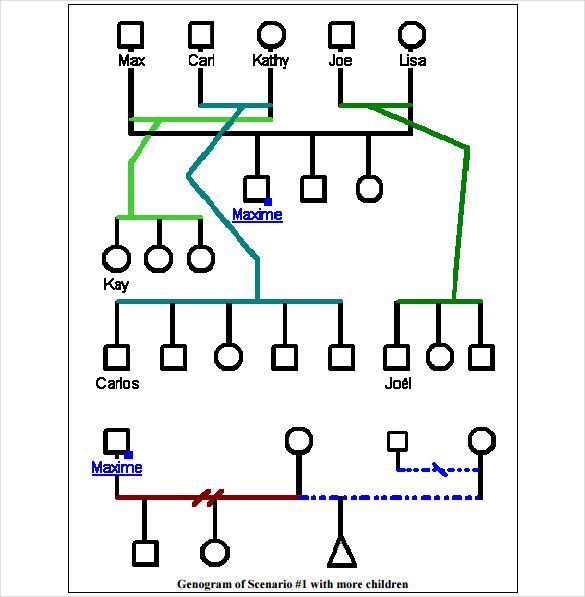

Introduction to GenogramsGenogram SymbolsGenogram RulesCreating a GenogramGenogram TemplateFamily relationshipsEmotional relationshipsMedical genogram Download GenoProGenograms come in various sizes and shapes, depending on their purpose. Below you will find examples of various genograms that illustrate a number of family situations that family trees may not be able to portray.

Star Wars Skywalker family genogram

Let’s start by looking at Padmé’s family. Her father Ruwee represented by square, mother Jobal represented by a circle. She also has an older sister named Sola, we know she is older because she is to the left.

She also has an older sister named Sola, we know she is older because she is to the left.

We can see that Padmé is in love with Anakin Skywalker who is the son of Shmi Skywalker and The Force.

Anakin and Padme have twins, Luke and Leia, however Anakin does not know this and does not know about Leia.

Luke is adopted by Owen Lars and Beru Whitsun. Owen turns out to be the son Of Cliegg Lars who married Anakin’s mother after Owen’s mother died.

On the other hand Leia is adopted by Bail Prestor Organa and Breha Antille and she takes the Organa family name.

Luke has a close violence relationship with his father, they fight every time they see each other.

Luke is friends with Han Solo who marries Leia and have a child named Ben.

Anakin, Luke, Leia, and Ben are strong carriers of Midi-chlorians, we can see a pattern from which we could begin to theorize that it is a hereditary trait.

Star Wars Skywalker family tree

Tiger Woods genogram

The following example is of Tiger Woods, considered to be one of the best golf players ever. Tiger was the child of Earl

Woods and Kutilda Punsawad, from Earl Woods' second marriage. Earl Woods took special interest in his son, and was his first golf coach. Earl had

himself been coached by his father, only in baseball. Earl and Tiger had a unique father-son bond, and Earl was Tiger's greatest inspiration in

life.

Tiger was the child of Earl

Woods and Kutilda Punsawad, from Earl Woods' second marriage. Earl Woods took special interest in his son, and was his first golf coach. Earl had

himself been coached by his father, only in baseball. Earl and Tiger had a unique father-son bond, and Earl was Tiger's greatest inspiration in

life.

Albert Einstein genogram

This next example is the genogram of Albert Einstein's family. This genogram tried to answer the question, where exactly did Einstein's genius come from? Well, this genogram does not reveal anyone of particular genius in the rest of his family, which may rule out the genetic factor. An interesting factor is that one of his sons had schizophrenia, a mental disorder. Also, Einstein still has at least five surviving descendants.

Albert Einstein family tree

Rosie O'Donnell example

This example features a well-known television show host, Rosie O'Donnell, who is in a committed same-sex relationship with

Kelli Carpenter. She has adopted children, prior to her relationship, and her partner has given birth to a child who was conceived with

the help of an anonymous sperm donor during the term of this current relationship. Together with these children, and a dog names Zoe, they create

a household. Rosie also had a foster child named Mia, but she was taken away from her in 2001, so she no longer lives with her.

She has adopted children, prior to her relationship, and her partner has given birth to a child who was conceived with

the help of an anonymous sperm donor during the term of this current relationship. Together with these children, and a dog names Zoe, they create

a household. Rosie also had a foster child named Mia, but she was taken away from her in 2001, so she no longer lives with her.

The genogram also demonstrates that Rosie had a fused relationship with her mother until she passed away at the age of 38 from breast cancer. After that, Rosie grew estranged from her father who was not emotionally available for his children. Interestingly, her brother is also in a committed long-term same-sex relationship.

O'Donnell family tree

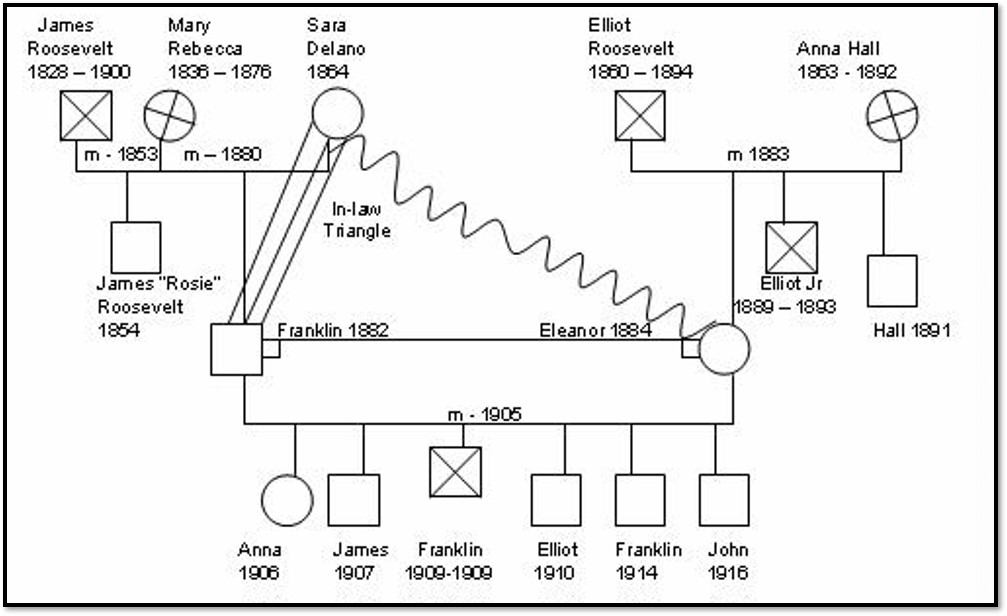

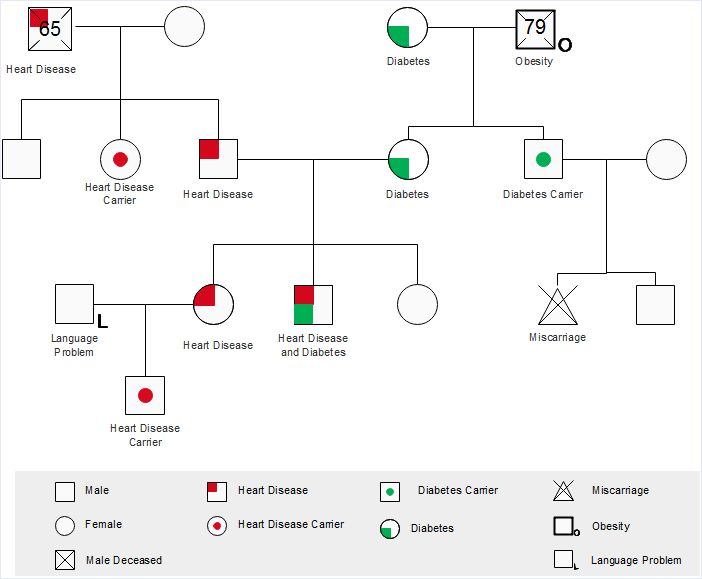

Fictional breast cancer study genogram

This last example is a fictional breast cancer study involving six families. In this study, a three-generational genogram was

created for the family of six women born in the early 1900s, and diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50. With these genograms, we can

easily see the incidence of breast cancer and ovarian cancer in the descendants because of the medical symbols

provided. Researchers can add important details, such as the age of diagnosis, the age at death, the type of cancer, the location of the cancer

(left, right, bilateral), etc., and display them on the genogram to facilitate interpretation of the data.

With these genograms, we can

easily see the incidence of breast cancer and ovarian cancer in the descendants because of the medical symbols

provided. Researchers can add important details, such as the age of diagnosis, the age at death, the type of cancer, the location of the cancer

(left, right, bilateral), etc., and display them on the genogram to facilitate interpretation of the data.

Previous: Introduction to genograms

Next: Genogram symbols

Focused genograms in the practice of a psychotherapist

Year of publication and journal number:

2010, No. 2

This article introduces psychotherapists to one of the further directions in the development of such an instrument of systemic family psychotherapy as genograms. The focused genogram is a ready-to-use, specific, understandable and convenient tool in the form of a sequence of already known questions, allowing the therapist to obtain accurate and complete information about the local aspect of the client's life through the consideration of multi-generational patterns. Focused genograms can be used by psychotherapists of any school, not necessarily systemic family ones. They help both structure the session and serve as a ready-made form of homework. Their use allows the client to realize that his belief is under the pressure of some family tradition, and make a further choice. In the case of pair work, it is useful to compare spouses' positions on the same issue, which are also rooted in the traditions of parental families.

Focused genograms can be used by psychotherapists of any school, not necessarily systemic family ones. They help both structure the session and serve as a ready-made form of homework. Their use allows the client to realize that his belief is under the pressure of some family tradition, and make a further choice. In the case of pair work, it is useful to compare spouses' positions on the same issue, which are also rooted in the traditions of parental families.

The genogram is the "calling card" of M. Bowen's Theory of Family Systems. This is a convenient graphical way to schematically display a family tree, including the designation of family members, their relationships with each other, dates of important events, geographical location.

The power of traditional genograms lies in creating a visual representation of family histories, myths, legends, rules, a spectrum of relationships, and their interrelationships over several generations. It allows you to visually analyze the location of various groups in the family system, the emotional processes of nuclear families, the dynamics of "emotional waves" in systems.

Dates, relationships, and locations are just a general outline for exploring emotional boundaries, mergers, breakups, key conflicts, the extent of sincerity, and the number of actual and potential relationships in a family. Generational context research allows predictions to be made.

Completing a genogram is neither an easy task nor an end in itself. To fill the scheme with content, you need to know what to look for. Since the creation of the genogram by Bowen, the development of this family therapy tool has advanced. Bowen's traditional genogram has given rise to several new tools. One of these tools is Focused genogram .

The Focused Genogram is the result of a series of structured questions based on Systems Theory, asked in a specific sequence, and allowing the therapist to obtain accurate and complete information about one local aspect of the client's life through the consideration of multigenerational patterns.

Focused genograms are designed to study the nature of some specific beliefs, attitudes, emotional and behavioral patterns within a given topic.

For example:

- Relationship, profession,

- money,

- marriage,

- social roles,

- gender expectations in the family,

- preferences in intimacy, sexual

- Ethnic features,

- features of the emotional sphere.

Focused genogram is a recent invention. This term and method was proposed and developed by several authors: Gerald R. Weeks, Rita DeMaria, and Larry Hof. At 19In 1999 they published the book FOCUSED GENOGRAMS: intergenerational assessment of individuals, couples, and families. It should be noted that so far there is practically no literature on this topic in Russian.

When should you use a focused genogram?

When the client needs to realize that his belief is under the pressure of some family tradition. If this is a couple, or a family, then when it will be useful for clients to compare views on the same issue, which are also rooted in the traditions of their parent families.

Example. Spouses quarrel. The motive is the struggle for power. The subject of quarrels most often is the lack of a permanent income from the husband. In the course of conversations, it becomes clear to the therapist that the spouses somehow have different attitudes about how to earn money. In this case, applying the money-focused genogram (money genogram) will help both to see the nature of this difference, which can eventually lead to anxiety reduction and compromise.

Another example. The client experiences constant depression and feelings of helplessness in their marriage. In the process of work, it becomes clear that these feelings are facilitated by a feeling of unfulfillment, that he cannot come to terms with his personal growth and his position. In working with such a client, it will be useful to apply the genogram focused on professional growth (professional genogram) in order to study the origin of some patterns and scenarios that affect not only his attitude to work, success, but also how it may also affect his relationship with his wife.

This article will give an example of two genograms focused on feelings.

Genogram focused on feelings (Genogram of Feelings).

In order to advance therapeutic change in any way, it is important to have a deeper understanding of the emotional bonds in couples and families and how they are formed and how those bonds can be broken.

Any genogram focused on feelings should trace the client's emotional history and family system in a way that helps the client become more aware of their emotional expression patterns, both in terms of pleasure and pain, to As a result, effective and satisfying emotional events could take place in the present.

The first school of emotional learning takes place in the family of origin. This emotional learning is represented by the role models parents present to their children, not only in how they communicate with them, their children, but also in what feelings they share as husband and wife.

In this sense, parents can be both gifted emotional teachers and set examples of another kind. Therefore, the expression of emotions and feelings, both verbal and non-verbal, varies significantly within different families.

Therefore, the expression of emotions and feelings, both verbal and non-verbal, varies significantly within different families.

Decisions about which of our feelings to express, and how to express our feelings in relationships, are usually made during childhood and adolescence.

A feelings-focused genogram can help reveal the reasons behind these decisions and beliefs. It can be used to gather a lot of information in general about feelings in the family and may take several sessions to complete. Such a genogram may include answers to the following questions:

- What feelings were predominant in each of your family members?

- What was the prevailing feeling, mood in your family as a whole? Who created this mood, who was responsible for it?

- Which feelings were the most frequent and which were the strongest?

- Expression of what feelings was forbidden in the family? If the taboo feeling nevertheless manifested itself, what was the punishment?

- What happened when feelings were not expressed in the family?

- Who in the family knew and who did not know how others felt?

- What happened to you when you expressed a forbidden feeling or feelings?

- How did you adapt to life, experiencing such, so to speak, unwanted emotions?

- Have others tried to force their opinion on you about how and how you should feel?

- Have you ever seen someone lose control of his or her feelings? What happened then? Has anyone in particular suffered from this? How exactly?

- If physical punishment was used in your family, what feelings did your parents express? And what feelings were allowed to children?

- Do you have feelings that you can't explain, but that are close to the feelings you've had in the past?

Questions about what feelings were represented in the family, what feelings were acceptable or not acceptable, and how different feelings were expressed explain the historical basis of the relationship. For example, the partner may then begin to see how certain feelings have always been blocked. And that relationships that may have once been functional and useful may no longer be functional today.

For example, the partner may then begin to see how certain feelings have always been blocked. And that relationships that may have once been functional and useful may no longer be functional today.

This applies equally to such socially disapproved feelings as anger. And in this case, the parental family is as strong a factor in the development of this belief system as it is in others. Children learn a lot about anger and conflict as they see, or fail to see, their parents' behavior. And the power of this influence is difficult to exaggerate.

Case Study

A man came in with recurring years of depression, feelings of unhappiness in his marriage, thoughts of wanting a divorce and his inability to go for it, fear of becoming an alcoholic. To the question: “At what moments of communication with his wife does he most acutely experience his unhappiness?”, He answered that at the moments when they quarrel. To the therapist’s question: “What exactly in the wife’s behavior during moments of quarrels makes him acutely experience this feeling of unhappiness?”, The client replied that when they quarrel, his wife “literally crushes him . ..”. To the therapist’s question: “What emotion of his wife, in his opinion, unambiguously leads him to feel “crushed?”, The client replied that her anger is probably this emotion. To the therapist’s question: “Is it right for spouses to have such feelings towards each other?”, The client replied that, in his opinion, “not only loving, but simply even slightly respecting each other, people cannot do this.”

..”. To the therapist’s question: “What emotion of his wife, in his opinion, unambiguously leads him to feel “crushed?”, The client replied that her anger is probably this emotion. To the therapist’s question: “Is it right for spouses to have such feelings towards each other?”, The client replied that, in his opinion, “not only loving, but simply even slightly respecting each other, people cannot do this.”

When a partner believes that certain feelings should not be experienced or expressed, the application of an appropriate focused genogram can help uncover the reason for this.

Anger focused genogram (Anger Genogram) illustrates these influences (DeMaria, Weeks, & Hof, 1999).

It answers the following questions:

- What do you think anger is?

- When you are angry, what does it mean?

- When you are angry with your spouse (partner), what does it mean?

- When a spouse is angry, what does it mean?

- When your spouse is angry with you, what does it mean?

- How do you respond to your spouse's anger?

- How do you react to your own anger?

- How do you let your spouse know that you are angry?

- How long does your anger usually last?

- What other feelings do you associate with anger?

- How did your parents handle anger, conflict?

- Have you ever seen your parents angry or in conflict with each other?

- When one of your family members (each one is called) became angry, how did others react?

- How did you cope with the anger of each of your parents?

- When a parent was angry with you, how did you feel and what did you do?

- When you got angry, who listened to you, or was able to listen? Who is not?

- How did your family members react when you became angry?

- Who was allowed and who was not allowed to get angry in your family?

- What is your best/worst memory of anger in your family?

- Has anyone in your family been seriously hurt when someone else was angry?

Genogram questions often show the difference in some patterns of parental families of both partners, and the associated feeling of comfort from the intensity of expression of emotions.

For example, for those who grow up in a family where conflict manifests itself through distance and isolation, the emotional intensity can be very uncomfortable. Likewise, those who grow up in families with volatile emotions are more likely to be emotionally spontaneous and volatile as well.

Example

A man acted as his mother's "pseudo-husband". He realized that his mother desperately needed his love and admiration. Ultimately, he found that by always being cheerful and loving, he could get her approval.

In his own marriage, he showed emotional benevolence, but at the same time, he periodically “erupted”, addressed his wife with great irritation, anger, and indignation. He always found a reason to be haughty and angry towards his wife.

His wife, on the contrary, felt guilty and depressed for many years. In her own family of origin, she was a peacemaker, and yet, in the end, she failed in this role. And she was subconsciously forced to keep trying herself in this role until everyone felt happy again.

When the emotions of the partners are not compatible with the situation, it is useful to think of an emotional shift towards the family of origin.

Focused genogram study showed that the husband had unexpressed anger towards his parents. In this case, the emotions directed towards his mother were actually projected onto his wife.

Another example

Consider a family where one family member, usually the father, is the only person who expresses his anger openly. In many of these cases, this pattern of behavior is associated with alcohol. The father used anger to exercise his power and express aggression. His mother and other family members responded to this behavior with fear, not knowing if his father would lose control.

Children raised in such a family may use the same pattern of behavior. Or, they may be very frightened of both the manifestation of their own anger and anger coming from others, and they may go even further in their behavior to avoid anger and its expression.

The third example of a family that tries to deny anger and conflict. Children from such families do not have and do not understand their own experience of anger or any of their partners. Thus, anger becomes an unknown and fearful feeling, often poorly understood.

The type of learning that one goes through in one's family of origin can play a significant role in choosing a partner. A partner who grew up in a home that often experienced anger may choose a rescue partner who appears not only to be devoid of anger, but of all feelings in general. In another case, the partner might choose a partner who is perceived as weak and dependent, so she or he can safely transfer old, unresolved feelings of anger onto him.

Working with a focused genogram, rescue partners come to understand what early events in their lives can affirm and teach. It is possible that they were told as children that they should never be angry, and this greatly limited their individual sensory experience, and led them to doubt their perception of the world.

They may subconsciously repeat old patterns of behavior or carry out a mission intended for the parent, and the therapist may see the same dynamic in the couple that was present in the couple of their parents.

Anger that is openly expressed and lived can serve both to give the person a sense of power, energy, and control, and to be used as a shield against experiencing feelings that are more difficult or painful. And the therapist can explore what those other feelings might be.

Some of the feelings underlying anger are: irritation, guilt, sadness, depression, helplessness, dependence, and mistrust. The therapist must keep these possibilities in mind while exploring those that seem likely.

The partner may not be in touch with these feelings, or may find it inappropriate to feel or express the underlying feeling.

For example, a person grew up in a family that practiced emotional coldness and rejection and entered his marriage with strong unresolved addiction needs. Previously, he could not admit that he needed any manifestation of feelings. He couldn't ask for what he wanted for fear of not getting it and the risk of rejection, and so he expected his wife to automatically know and give him what he desperately wants. He was constantly angry with her for her failure to meet his unspoken needs.

Previously, he could not admit that he needed any manifestation of feelings. He couldn't ask for what he wanted for fear of not getting it and the risk of rejection, and so he expected his wife to automatically know and give him what he desperately wants. He was constantly angry with her for her failure to meet his unspoken needs.

Focused genogram technique

Focused genogram can be used both directly in the session, and then it can act as a structure, or in the form of homework. Each of these methods has its own advantages. In the event that clients give answers to genogram questions in a session, the therapist has the opportunity to work directly with the feelings and reactions of clients. But this increases the total time of work with genograms, because during one session, it is possible to discuss a couple of issues and the difference in the positions of clients. Thus, it takes two, or even three, four months to complete the discussion of the genogram. At the same time, the process of discussing questions and answers of the genogram has been a certain structure of work for many years. The therapist can plan ahead, and this is especially helpful for beginning therapists who need some structure to support them.

The therapist can plan ahead, and this is especially helpful for beginning therapists who need some structure to support them.

If the focused genogram is given as homework, there are other advantages. Firstly, it reduces the total time of work with the genogram. Secondly, the client comes to the therapist already with some analysis of his answers, i.e. takes a more detached expert position, which creates an exploratory collaborative environment between client and therapist. The therapist and client are on one side, and the client's responses and situation are on the other. And as a result, this increases the trust of the therapeutic relationship and the effectiveness of the work. At the same time, it is also possible to discuss the first emotions that the client experienced when he got acquainted with each new question, and what prompted him to settle on the final opinion. If the work is carried out with a married couple, then questions are given to each spouse, and initially each answers them independently. Next, a joint discussion of the answers by the spouses is proposed to compare the positions of the spouses on each question. This last action can take place either at home or in session.

Next, a joint discussion of the answers by the spouses is proposed to compare the positions of the spouses on each question. This last action can take place either at home or in session.

An important issue is also the choice of the right moment to apply the focused genogram. To begin with, the author suggests trying to use them at the end of the session as homework. Clients will be able to review the questions in their entirety at home, and then, at the next meeting, begin a joint discussion of the first answers, which may be accompanied by interpretations by the therapist, either clarifying or containing "a difference that creates a difference ...".

Conclusions

At first glance, a tool like focused genograms has undoubted advantages. When using them , the client gets the opportunity:

- to formulate their own point of view,

- to reflect it on paper, and take an external expert position in relation to it,

- to understand it, express their attitude, formulate priorities,

- the need to develop an alternative.

Focused genogram helps the client to concretize the perception of available opportunities, determine what influences their choice, stimulates interest and success.

At the same time, in marital therapy focussed genograms are able to clarify the difference in the nature of partners' preferences. Getting acquainted with inherited priorities in each other's positions, the spouses get the opportunity:

- to see that the cause of conflicts is not in personal qualities, but in the difference and inconsistency of positions inherited by families,

- clarify their own expectations and beliefs,

- compare with the expectations of a partner , reconcile them,

- evaluate both the possibility of their implementation and their own or joint resources.

- make choices about accepting or rejecting certain beliefs, applying those decisions to healthy functioning in your relationships.

Finally, the Bowen method is quite difficult to use and takes a long time to learn, and focused genograms can be used by psychotherapists of any school , not only systemic family therapists. For this, it is not necessary to think through a systemic hypothesis.

For this, it is not necessary to think through a systemic hypothesis.

Psychotherapist in the form of a focused genogram receives a ready-to-use, very specific, understandable and convenient tool for practice in the form of a sequence of already known questions. This is especially convenient for novice therapists, as helps structure the session. In addition, the focused genogram is a good form of homework.

The use of focused genograms changes the interaction in the "psychologist-client" pair . Externalization of the client's point of view places both him and the therapist on the same research field, creating a creative coalition between them. This increases the safety and confidence of the therapeutic process, and ultimately increases efficiency.

PSYCHOLOGICAL EXAMINATION OF THE FAMILY AS A WHOLE. FAMILY HISTORY RESEARCH. Genogram

Genogram

One of the simplest, but meaningful and fairly common tools for collecting information about a family is a genogram.

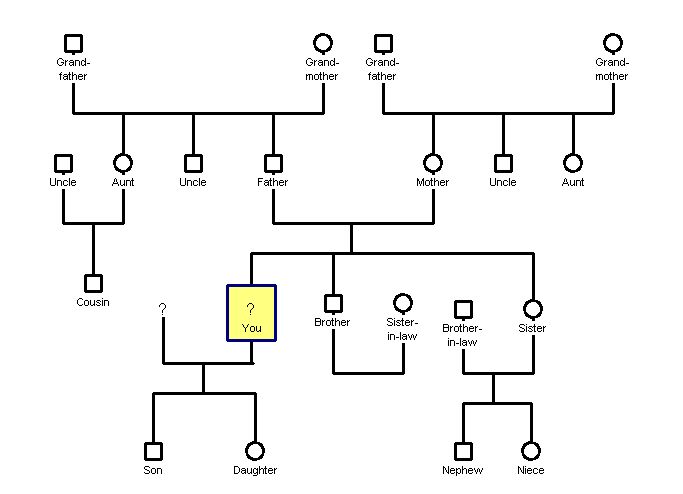

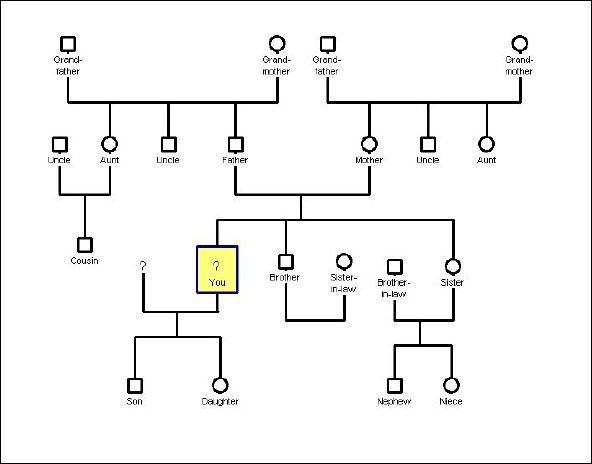

Genogram [Chernikov A. V., 1998] is a form of graphic family pedigree, on which information about family members is recorded in a special way - with the help of special signs - at least in three generations.

The genogram, unlike other forms of consultative and therapeutic records kept by a psychologist, allows you to constantly make additions and adjustments at each meeting with the family. This can be done by both the psychologist and the client. It enables the therapist and client to keep in mind a large amount of information about family members, their relationships and key events in family history.

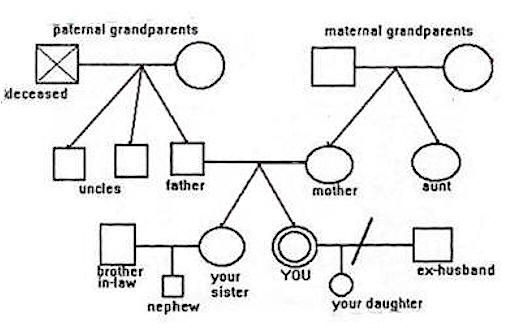

Genogram is not a test and does not contain clinical scores. But it is a tool for collecting information about a problem family, i.e. performs the same function as tests. The genogram was introduced by Murray Bowen [Bowen, 1978] and serves to analyze family history from the standpoint of systems theory. The list of standard symbols used in the genogram is presented below (Fig. 15, 16).

On the genogram, next to the persons to whom it refers, other important information can be briefly marked: names, education, occupation, serious diseases, place of residence at the moment, etc.

For a client to draw the genogram of his family on a sheet of paper the first time, even if there are symbols in front of him, is a practically unsolvable task. Therefore, as a rule, the genogram is compiled by a psychologist or a psychologist with the active participation of family members (members).

In any case, a detailed interview is conducted on the material of the genogram.

Fig. 15. The main designations of the family genogram

Adopted daughter, with the indicated date of birth (above) and the date of admission to a new family (below)

second husband)

- Genogram of three generations: spouses, their parents and children. The example shows that the spouses have two children: a boy of 8 years and a girl of 5 years old, born at 1988 and 1991 The wife is the only child in the family, the husband has a younger brother. Children are designated by seniority from left to right

Pic. 16. Types of relationships

According to A. V. Chernikov [Chernikov A. V., 1998], a genogram interview usually includes the following questions:

1. Family composition. Who lives with you? What kind of relationship are they? Did the couple have other marriages? Do they have children? Where do the rest of the family live?

2. Demographic information about the family: names, gender, age, length of marriage, occupation and education of family members, etc.

3. Current state of the problem. Who in the family knows about the problem? How does each of them see it and how do they react to it? Does anyone in the family have similar problems?

4. History of the development of the problem. When did the problem occur? Who noticed her first? Who thinks of it as a serious problem, and who tends not to attach much importance to it? What decision attempts were made, by whom, and in these situations? Has the family consulted a specialist before and have there been hospitalizations? How have relationships in the family changed compared to what they were before the crisis? Do family members see the problem as changing? In what direction: for better or for worse? What will happen in the family if the crisis continues? How do you see relationships in the future?

5. Recent events and transitions in the family life cycle: births, deaths, marriages, divorces, moves, job problems, illnesses of family members, etc.

Recent events and transitions in the family life cycle: births, deaths, marriages, divorces, moves, job problems, illnesses of family members, etc.

6. Family reactions to important events in family history. What was the family's reaction when a certain child was born? Who was it named after? When and why did the family move to this city? Who has experienced the death of a family member the hardest? Who took it easier? Who organized the funeral?

Evaluation of past coping patterns, especially family reorganizations after losses and other critical transitions, provides important hypotheses about family rules, expectations, and organizational patterns.

7. Family of parents of each spouse. Are the client's parents alive? If they died, when and from what? If alive, what are they doing? Retired or working? Are they divorced? Have they had other marriages? When did they meet? When did you get married? Does the client have siblings? Older or younger and by how much? What do they do, are they married and do they have children?

The therapist can then ask the same questions about the parents of the father and mother. The goal is to collect information on at least three to four generations, including the generation of the identified patient. Important information is information about adopted children, miscarriages, abortions, children who died early.

8. Other significant family members: friends, colleagues, teachers, doctors, etc.

9. Family relationships. Are there any family members who have broken off relationships with each other? Is there anyone who is in a serious conflict? Which family members are very close to each other? Who in the family does this person trust the most? All married couples have some difficulties and sometimes conflict. What types of disagreement are there in a client pair? The client's parents? In the marriages of the client's siblings? How does each spouse get along with each child?

The therapist can ask special circular questions (see section 3.4). For example, he might ask her husband, “How close do you think your mother and your older brother were?” - and then ask about his wife's impressions on this topic.

It is sometimes helpful to ask how the people present at the meeting would be described by other family members: "How would your father describe you when you were thirteen, which is your son's age now?" The purpose of such circular questions is to detect differences in relationships with different family members. While discovering different perceptions in different family members, the therapist simultaneously introduces new information into the system, enriching the family with views of itself.

10. Family roles. Which family member likes to take care of others? And who likes to be taken care of a lot? Who in the family looks like a strong-willed person? Who is the most authoritative? Which child is more obedient to their parents? Who is successful? Who is constantly failing? Who seems warm? Cold? Distancing from others? Who is the most sick in the family? Etc.

It is important for the therapist to pay attention to the labels and nicknames that family members give to each other (“supermother”, “iron lady”, “domestic tyrant”, etc.