Feeling like a fraud syndrome

What It Is & How to Overcome It

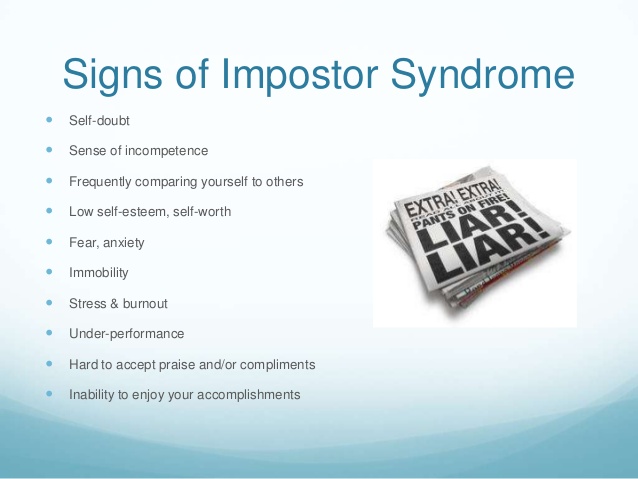

Imposter syndrome involves unfounded feelings of self doubt and incompetence. You can reduce these feelings by talking to friends, family, or other supportive peers. A mental health professional can also help you identify helpful coping strategies.

“What am I doing here?”

“I don’t belong.”

“I’m a total fraud, and sooner or later, everyone’s going to find out.”

If you’ve ever felt like an imposter at work, you’re not alone. A 2019 review of 62 studies on imposter syndrome suggested anywhere from 9 to 82 percent of people report having thoughts along these lines at some point.

Early research exploring this phenomenon primarily focused on accomplished, successful women. It later became clear, though, that imposter syndrome can affect anyone in any profession, from graduate students to top executives.

Imposter syndrome, also called perceived fraudulence, involves feelings of self-doubt and personal incompetence that persist despite your education, experience, and accomplishments.

![]()

To counter these feelings, you might end up working harder and holding yourself to ever higher standards. This pressure can eventually take a toll on your emotional well-being and your performance.

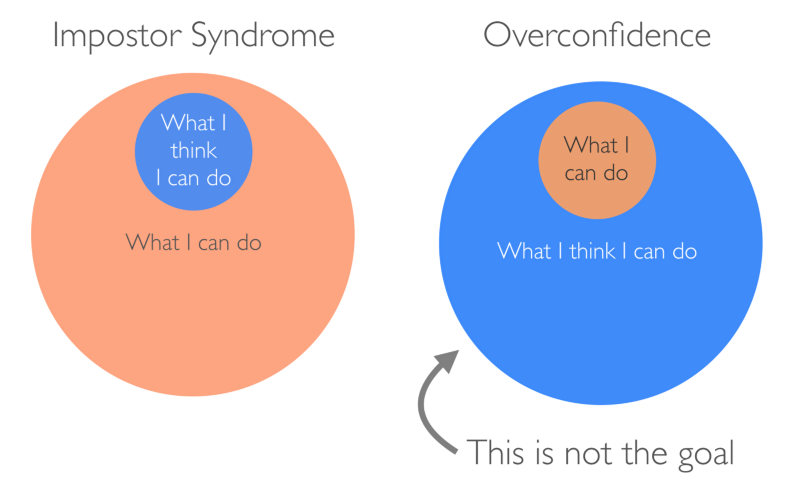

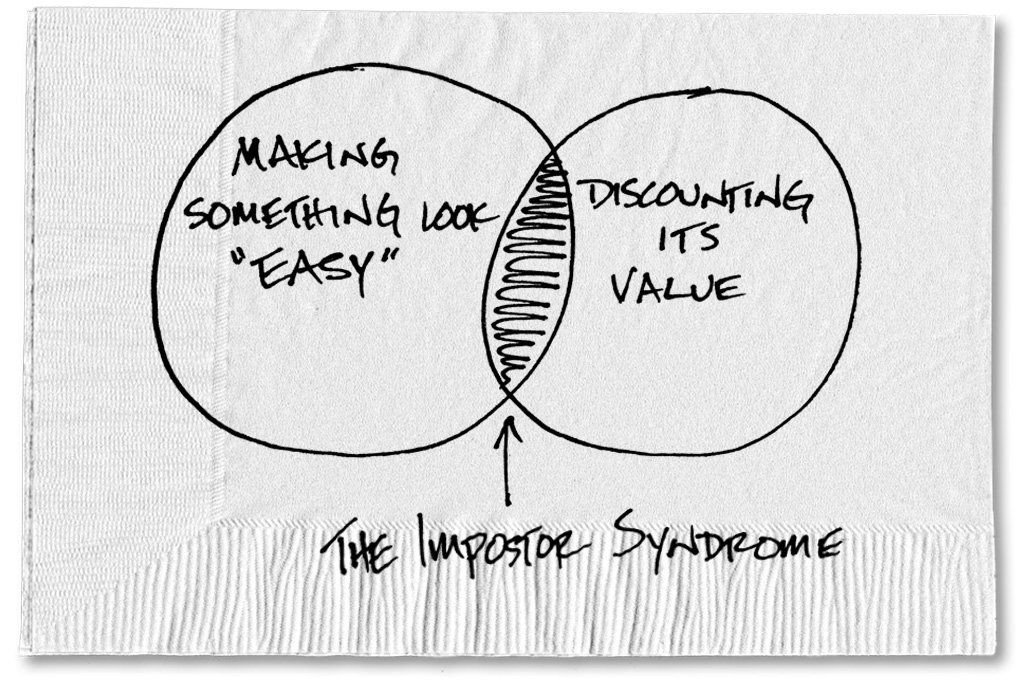

Imposter feelings represent a conflict between your own self-perception and the way others perceive you.

Even as others praise your talents, you write off your successes to timing and good luck. You don’t believe you earned them on your own merits, and you fear others will eventually realize the same thing.

Consequently, you pressure yourself to work harder in order to:

- keep others from recognizing your shortcomings or failures

- become worthy of roles you believe you don’t deserve

- make up for what you consider your lack of intelligence

- ease feelings of guilt over “tricking” people

The work you put in can keep the cycle going. Your further accomplishments don’t reassure you — you consider them nothing more than the product of your efforts to maintain the “illusion” of your success.

Any recognition you earn? You call it sympathy or pity. And despite linking your accomplishments to chance, you take on all the blame for any mistakes you make. Even minor errors reinforce your belief in your lack of intelligence and ability.

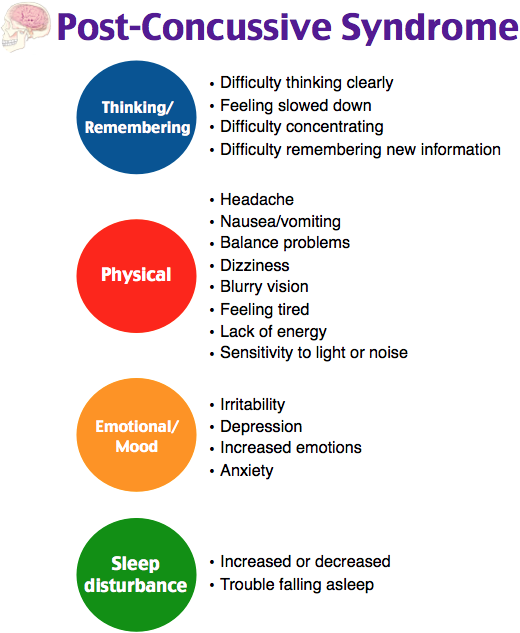

Over time, this can fuel a cycle of anxiety, depression, and guilt.

Living in constant fear of discovery, you strive for perfection in everything you do. You might feel guilty or worthless when you can’t achieve it, not to mention burned out and overwhelmed by your continued efforts.

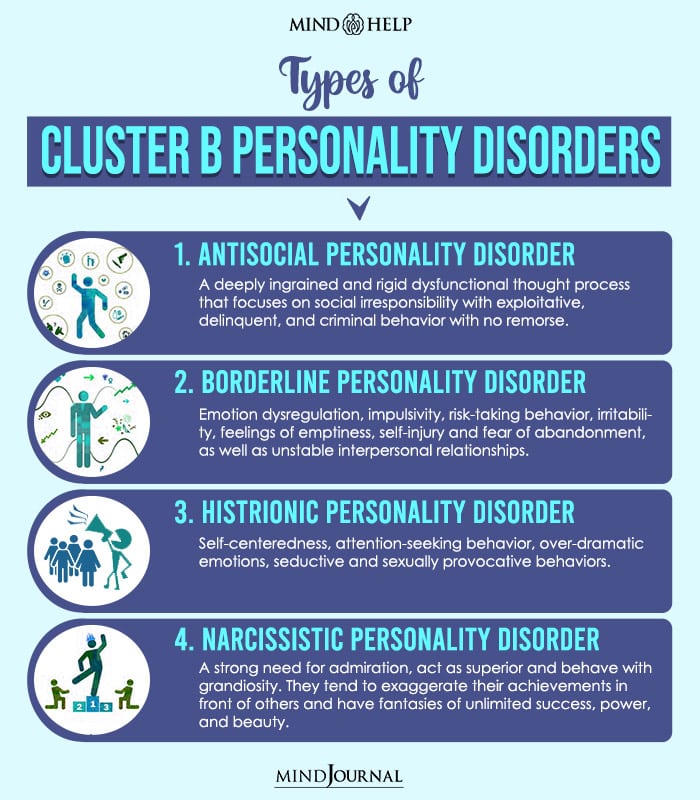

Leading imposter syndrome researcher Dr. Valerie Young describes five main types of imposters in her 2011 book “The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women: Why Capable People Suffer from the Impostor Syndrome and How to Thrive in Spite of It.”

These competence types, as she calls them, reflect your internal beliefs around what competency means to you.

Here’s a closer look at each type and how they manifest.

The perfectionist

You focus primarily on how you do things, often to the point where you demand perfection of yourself in every aspect of life.

Yet, since perfection isn’t always a realistic goal, you can’t meet these standards. Instead of acknowledging the hard work you’ve put in after completing a task, you might criticize yourself for small mistakes and feel ashamed of your “failure.”

You might even avoid trying new things if you believe you can’t do them perfectly the first time.

The natural genius

You’ve spent your life picking up new skills with little effort and believe you should understand new material and processes right away.

Your belief that competent people can handle anything with little difficulty leads you to feel like a fraud when you have a hard time.

If something doesn’t come easily to you, or you fail to succeed on your first try, you might feel ashamed and embarrassed.

The rugged individualist (or soloist)

You believe you should be able to handle everything solo. If you can’t achieve success independently, you consider yourself unworthy.

Asking someone for help, or accepting support when it’s offered, doesn’t just mean failing your own high standards. It also means admitting your inadequacies and showing yourself as a failure.

It also means admitting your inadequacies and showing yourself as a failure.

The expert

Before you can consider your work a success, you want to learn everything there is to know on the topic. You might spend so much time pursuing your quest for more information that you end up having to devote more time to your main task.

Since you believe you should have all the answers, you might consider yourself a fraud or failure when you can’t answer a question or encounter some knowledge you previously missed.

The superhero

You link competence to your ability to succeed in every role you hold: student, friend, employee, or parent. Failing to successfully navigate the demands of these roles simply proves, in your opinion, your inadequacy.

To succeed, then, you push yourself to the limit, expending as much energy as possible in every role.

Still, even this maximum effort may not resolve your imposter feelings. You might think, “I should be able to do more,” or “This should be easier. ”

”

There’s no single clear cause of imposter feelings. Rather, a number of factors likely combine to trigger them.

Potential underlying causes include the following.

Parenting and childhood environment

You might develop imposter feelings if your parents:

- pressured you to do well in school

- compared you to your sibling(s)

- were controlling or overprotective

- emphasized your natural intelligence

- sharply criticized mistakes

Academic success in childhood could also contribute to imposter feelings later in life.

Maybe elementary and high school never posed much of a challenge. You learned easily and received plenty of praise from teachers and parents.

In college, however, you find yourself struggling for the first time. You might begin to believe your classmates are all more intelligent and gifted, and you might worry you don’t belong in college, after all.

Personality traits

Experts have linked specific personality traits to imposter feelings.

These include:

- perfectionistic tendencies

- low self-efficacy, or confidence in your ability to manage your behavior and successfully handle your responsibilities

- higher scores on measures of neuroticism, a big five personality trait

- lower scores on measures of conscientiousness, another big five trait

Existing mental health symptoms

Fears of failure can prompt plenty of emotional distress, and many people coping with imposter feelings also experience anxiety and depression.

But living with depression or anxiety might mean you already experience self-doubt, diminished self-confidence, and worries around how others perceive you.

This mindset of feeling “less than” can both lead to and reinforce the belief that you don’t really belong in your academic or professional environment.

Imposter syndrome can worsen mental health symptoms, creating a cycle that’s difficult to escape.

New responsibilities

It’s not at all uncommon to feel unworthy of a career or academic opportunity you just earned.

You want the job, certainly. It could even be your dream job. All the same, you might worry you won’t measure up to expectations or believe your abilities won’t match those of your coworkers or classmates.

These feelings may fade as you settle in and get familiar with the role. Sometimes, though, they can get worse — particularly if you fail to receive support, validation, and encouragement from your supervisors or peers.

Along with the above factors, gender bias and institutionalized racism can also play a significant part in imposter feelings.

Research consistently suggests that while, yes, anyone can experience these feelings, they tend to show up more often in women and people of color. In other words: people who generally have less representation in professional environments.

Awareness of the bias against your gender or race might lead you to work harder in order to disprove harmful stereotypes. You might believe you need to dedicate more effort than anyone else in order to be taken seriously, much less earn recognition for your efforts.

Simply being aware of these negative stereotypes can affect your performance, leading you to fixate on your mistakes and further doubt your abilities.

The microaggressions and discrimination — both blatant and subtle — you experience along the way can reinforce the feeling you don’t belong. This is, of course, exactly what they’re intended to do.

Even the name “imposter syndrome” can reinforce the perception of yourself as unworthy. The word “imposter” carries a strong connotation of deceit and manipulation, while “syndrome” generally implies illness.

True imposter feelings involve self-doubt, uncertainty about your talents and abilities, and a sense of unworthiness that doesn’t align with what others think about you.

In short, you think you’ve fooled others into believing you are someone you aren’t.

But what if you find yourself in an environment where your peers fail to make room for you or imply you don’t deserve your success? Perhaps there aren’t any other people of color in your class, or your supervisor outright says, “Women usually don’t make it in this job. ”

”

It’s entirely understandable you might begin to feel out of place and undeserving.

There’s a big difference between secretly doubting your abilities and being made to feel as if your identity makes you unworthy of your position or accomplishments.

More inclusive research on imposter feelings as experienced by people of color, particularly women of color, may help separate these experiences.

Promoting workplace and academic cultures that foster inclusivity and actively work toward anti-racism could be key in reducing imposter feelings.

When it’s not imposter feelings you’re experiencing, but the more insidious effects of systemic racism, a culturally sensitive therapist can offer support and help you explore next steps.

If you feel like a fraud, working harder to do better may not do much to change your self-image.

These strategies can help you resolve imposter feelings productively.

Acknowledge your feelings

Identifying imposter feelings and bringing them out into the light of day can accomplish several goals.

- Talking to a trusted friend or mentor about your distress can help you get some outside context on the situation.

- Sharing imposter feelings can help them feel less overwhelming.

- Opening up to peers about how you feel encourages them to do the same, helping you realize you aren’t the only one who feels like an imposter.

Build connections

Avoid giving in to the urge to do everything yourself. Instead, turn to classmates, academic peers, and coworkers to create a network of mutual support.

Remember, you can’t achieve everything alone. Your network can:

- offer guidance and support

- validate your strengths

- encourage your efforts to grow

Sharing imposter feelings can also help others in the same position feel less alone. It also creates the opportunity to share strategies for overcoming these feelings and related challenges you might encounter.

Challenge your doubts

When imposter feelings surface, ask yourself whether any actual facts support these beliefs. Then, look for pieces of evidence to counter them.

Then, look for pieces of evidence to counter them.

Say you’re considering applying for a promotion, but you don’t believe you have what it takes. Maybe a small mistake you made on a project a few months ago still haunts you. Or perhaps you think the coworkers who praise your work mostly just feel sorry for you.

Fooling all of your coworkers would be pretty difficult, though, and poor work probably wouldn’t go unnoticed long term.

If you consistently receive encouragement and recognition, that’s a good sign you’re doing plenty right — and deserve a chance for promotion.

Avoid comparing yourself to others

Everyone has unique abilities. You are where you are because someone recognized your talents and your potential.

You may not excel in every task you attempt, but you don’t have to, either. Almost no one can “do it all.” Even when it seems like someone has everything under control, you may not know the full story.

It’s OK to need a little time to learn something new, even if someone else seems to grasp that skill immediately.

Instead of allowing others’ success to highlight your flaws, consider exploring ways to develop the abilities that interest you.

Success doesn’t require perfection. True perfection is practically impossible, so failing to achieve it doesn’t make you a fraud.

Offering yourself kindness and compassion instead of judgment and self-doubt can help you maintain a realistic perspective and motivate you to pursue healthy self-growth.

If you continue to struggle with imposter feelings, a therapist can offer support with:

- overcoming feelings of unworthiness or perceived fraudulence

- addressing anxiety, depression, or other emotional distress

- challenging and reframing unwanted beliefs

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

Stop Telling Women They Have Imposter Syndrome

Leer en español

Ler em português

Talisa Lavarry was exhausted. She had led the charge at her corporate-event-management company to plan a high-profile, security-intensive event, working around the clock and through weekends for months. Barack Obama was the keynote speaker.

Lavarry knew how to handle the complicated logistics required — but not the office politics. A golden opportunity to prove her expertise had turned into a living nightmare. Lavarry’s colleagues interrogated and censured her, calling her professionalism into question. Their bullying, both subtle and overt, haunted each decision she made. Lavarry wondered whether her race had something to do with the way she was treated. She was, after all, the only Black woman on her team. She began doubting whether she was qualified for the job, despite constant praise from the client.

Things with her planning team became so acrimonious that Lavarry found herself demoted from lead to colead and was eventually unacknowledged altogether by her colleagues. Each action that chipped away at her role in her work doubly chipped away at her confidence. She became plagued by deep anxiety, self-hatred, and the feeling that she was a fraud.

Each action that chipped away at her role in her work doubly chipped away at her confidence. She became plagued by deep anxiety, self-hatred, and the feeling that she was a fraud.

What had started as healthy nervousness — Will I fit in? Will my colleagues like me? Can I do good work? — became a workplace-induced trauma that had her contemplating suicide.

Today, when Lavarry, who has since written a book about her experience, Confessions From Your Token Black Colleague, reflects on the imposter syndrome she fell prey to during that time, she knows it wasn’t a lack of self-confidence that held her back. It was repeatedly facing systemic racism and bias.

Examining Imposter Syndrome as We Know It

Imposter syndrome is loosely defined as doubting your abilities and feeling like a fraud. It disproportionately affects high-achieving people, who find it difficult to accept their accomplishments. Many question whether they’re deserving of accolades.

Psychologists Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes developed the concept, originally termed “imposter phenomenon,” in their 1978 founding study, which focused on high-achieving women. They posited that “despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, women who experience the imposter phenomenon persist in believing that they are really not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise.” Their findings spurred decades of thought leadership, programs, and initiatives to address imposter syndrome in women. Even famous women — from Hollywood superstars such as Charlize Theron and Viola Davis to business leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and even former First Lady Michelle Obama and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor — have confessed to experiencing it. A Google search yields more than 5 million results and shows solutions ranging from attending conferences to reading books to reciting one’s accomplishments in front of a mirror. What’s less explored is why imposter syndrome exists in the first place and what role workplace systems play in fostering and exacerbating it in women. We think there’s room to question imposter syndrome as the reason women may be inclined to distrust their success.

They posited that “despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, women who experience the imposter phenomenon persist in believing that they are really not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise.” Their findings spurred decades of thought leadership, programs, and initiatives to address imposter syndrome in women. Even famous women — from Hollywood superstars such as Charlize Theron and Viola Davis to business leaders such as Sheryl Sandberg and even former First Lady Michelle Obama and Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor — have confessed to experiencing it. A Google search yields more than 5 million results and shows solutions ranging from attending conferences to reading books to reciting one’s accomplishments in front of a mirror. What’s less explored is why imposter syndrome exists in the first place and what role workplace systems play in fostering and exacerbating it in women. We think there’s room to question imposter syndrome as the reason women may be inclined to distrust their success.

Read more about

Mentoring Someone with Imposter Syndrome

The impact of systemic racism, classism, xenophobia, and other biases was categorically absent when the concept of imposter syndrome was developed. Many groups were excluded from the study, namely women of color and people of various income levels, genders, and professional backgrounds. Even as we know it today, imposter syndrome puts the blame on individuals, without accounting for the historical and cultural contexts that are foundational to how it manifests in both women of color and white women. Imposter syndrome directs our view toward fixing women at work instead of fixing the places where women work.

Feeling Unsure Shouldn’t Make You an Imposter

Imposter syndrome took a fairly universal feeling of discomfort, second-guessing, and mild anxiety in the workplace and pathologized it, especially for women. As white men progress, their feelings of doubt usually abate as their work and intelligence are validated over time. They’re able to find role models who are like them, and rarely (if ever) do others question their competence, contributions, or leadership style. Women experience the opposite. Rarely are we invited to a women’s career development conference where a session on “overcoming imposter syndrome” is not on the agenda.

They’re able to find role models who are like them, and rarely (if ever) do others question their competence, contributions, or leadership style. Women experience the opposite. Rarely are we invited to a women’s career development conference where a session on “overcoming imposter syndrome” is not on the agenda.

The label of imposter syndrome is a heavy load to bear. “Imposter” brings a tinge of criminal fraudulence to the feeling of simply being unsure or anxious about joining a new team or learning a new skill. Add to that the medical undertone of “syndrome,” which recalls the “female hysteria” diagnoses of the nineteenth century. Although feelings of uncertainty are an expected and normal part of professional life, women who experience them are deemed to suffer from imposter syndrome. Even if women demonstrate strength, ambition, and resilience, our daily battles with microaggressions, especially expectations and assumptions formed by stereotypes and racism, often push us down. Imposter syndrome as a concept fails to capture this dynamic and puts the onus on women to deal with the effects. Workplaces remain misdirected toward seeking individual solutions for issues disproportionately caused by systems of discrimination and abuses of power.

Bias and Exclusion Exacerbate Feelings of Doubt

For women of color, self-doubt and the feeling that we don’t belong in corporate workplaces can be even more pronounced — not because women of color (a broad, imprecise categorization) have an innate deficiency but because the intersection of our race and gender often places us in a precarious position at work. Many of us across the world are implicitly, if not explicitly, told we don’t belong in white- and male-dominated workplaces. Half of the women of color surveyed by Working Mother Media plan to leave their jobs in the next two years, citing feelings of marginalization or disillusionment, which is consistent with our experiences. Exclusion that exacerbated self-doubt was a key reason for each of our transitions from corporate workplaces to entrepreneurship.

“Who is deemed ‘professional’ is an assessment process that’s culturally biased and skewed,” said Tina Opie, an associate professor at Babson College, in an interview last year. When employees from marginalized backgrounds try to hold themselves up to a standard that no one like them has met (and that they’re often not expected to be able to meet), the pressure to excel can become too much to bear. The once-engaged Latina woman suddenly becomes quiet in meetings. The Indian woman who was a sure shot for promotion gets vague feedback about lacking leadership presence. The trans woman who always spoke up doesn’t anymore because her manager makes gender-insensitive remarks. The Black woman whose questions once helped create better products for the organization doesn’t feel safe contributing feedback after being told she’s not a team player. For women of color, universal feelings of doubt become magnified by chronic battles with systemic bias and racism.

Women at Work

Resources, practical advice, and personal stories to lift you up and move you forward.

In truth, we don’t belong because we were never supposed to belong. Our presence in most of these spaces is a result of decades of grassroots activism and begrudgingly developed legislation. Academic institutions and corporations are still mired in the cultural inertia of the “good ol’ boys” clubs and white supremacy. Biased practices across institutions routinely stymie the ability of individuals from underrepresented groups to truly thrive.

The answer to overcoming imposter syndrome is not to fix individuals but to create an environment that fosters a variety of leadership styles and in which diverse racial, ethnic, and gender identities are seen as just as professional as the current model, which Opie describes as usually “Eurocentric, masculine, and heteronormative.”

Confidence Doesn’t Equal Competence

We often falsely equate confidence — most often, the type demonstrated by white male leaders — with competence and leadership. Employees who can’t (or won’t) conform to male-biased social styles are told they have imposter syndrome. According to organizational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic:

According to organizational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic:

The truth of the matter is that pretty much anywhere in the world men tend to think that they are much smarter than women. Yet arrogance and overconfidence are inversely related to leadership talent — the ability to build and maintain high-performing teams, and to inspire followers to set aside their selfish agendas in order to work for the common interest of the group.

The same systems that reward confidence in male leaders, even if they’re incompetent, punish white women for lacking confidence, women of color for showing too much of it, and all women for demonstrating it in a way that’s deemed unacceptable. These biases are insidious and complex and stem from narrow definitions of acceptable behavior drawn from white male models of leadership. Research from Kecia M. Thomas finds that too often women of color enter their companies as “pets” but are treated as threats once they gain influence in their roles. Women of color are by no means a monolith, but we are often linked by our common experiences of navigating stereotypes that hold us back from reaching our full potential.

Women of color are by no means a monolith, but we are often linked by our common experiences of navigating stereotypes that hold us back from reaching our full potential.

Fixing Bias, Not Women

Imposter syndrome is especially prevalent in biased, toxic cultures that value individualism and overwork. Yet the “fix women’s imposter syndrome” narrative has persisted, decade after decade. We see inclusive workplaces as a multivitamin that can ensure that women of color can thrive. Rather than focus on fixing imposter syndrome, professionals whose identities have been marginalized and discriminated against must experience a cultural shift writ large.

Leaders must create a culture for women and people of color that addresses systemic bias and racism. Only by doing so can we reduce the experiences that culminate in so-called imposter syndrome among employees from marginalized communities — or at the very least, help those employees channel healthy self-doubt into positive motivation, which is best fostered within a supportive work culture.

Perhaps then we can stop misdiagnosing women with “imposter syndrome” once and for all.

What is the impostor syndrome and how to get rid of it

The feeling that success was achieved due to luck, not talent or skill, is inherent in many people in various fields - from professional to personal. How to overcome impostor syndrome and whether it is necessary, in RBC Trends

“For me, impostor syndrome is a feeling that you are not up to par, but you are already “stuck” in a situation. When you realize that you do not have enough skills, experience or qualifications to have the right to be here, but you are already here, and you need to find a way out, because there is no turning back. It’s not the fear of failure, but rather the feeling that something has gotten away with you and will soon be discovered,” describes this feeling Mike Canon-Brooks, co-founder of Atlassian, whose most famous products are the Jira bug tracking system and the Confluence collaboration system.

To find out if you are experiencing something similar, you can take a test developed by Pauline Klans, which includes 20 statements with varying degrees of agreement - from "not at all true" to "absolutely true."

Impostor Syndrome: psychologist Anna Pham on why we don’t believe in our success

(Video: RBC)

To accept this feeling and use it for your own benefit, it is important to realize a few things:

- others are also feel;

- it will not go away on its own even after some success has been achieved;

- this feeling can extend not only to the professional, but also to other areas of life, for example, relationships;

- is normal.

Prevalence of the impostor syndrome

According to various estimates, about 70% of people on the planet felt certain manifestations of the syndrome [1]. Celebrity anxiety about skill mismatch in position or job is also common among celebrities. Before his death, Albert Einstein confessed to his friend that he felt like a fraud [2].

Before his death, Albert Einstein confessed to his friend that he felt like a fraud [2].

Who is more prone to impostor syndrome - men or women

The phenomenon was first described in the 1970s by American psychology professor Pauline Rose Klans and clinical psychologist Suzanne Imes based on communication with women who have achieved high results. Despite objective evidence of success, they considered themselves unworthy of him and feared exposure. For a long time, researchers believed [3] that only women are affected by the syndrome. All because of gender restrictions. Women did not hold responsible positions, and they entered most professions much later than men.

Later, Klans noted in her article that all people, regardless of gender, are subject to the manifestations of the syndrome. Research in the 1990s confirmed [4] that men also experience impostor syndrome. At the same time, they are less likely to talk about their problems and go to psychotherapists, but they talk about fears in anonymous surveys [5].

Strictly speaking, it is not entirely correct to call this a "syndrome", since such feelings do not mean any deviations in the state of mental health and are quite natural for any person.

Imposter syndrome test

Dr. Valerie Young, an international expert working on the phenomenon of impostor syndrome, has identified five different types of "imposters".

Follow the questionnaire to find out if you have impostor syndrome and which of the five types it is.

Impostor syndrome test

Impostor syndrome test

Why does impostor syndrome develop?

There is no definite answer. Some experts believe that this is due to personal qualities, others highlight family or behavioral reasons. Sometimes the manifestation of the syndrome is associated with high parental expectations from children and the fear of not meeting them, which persists even into adulthood.

Psychologists also cite successful siblings as the cause, who the person suffering from Imposter Syndrome feels outshines them. The role of deceptive pictures in social networks is also high, fueling the feeling that everyone around is happy and has achieved high results in work, personal life, self-development, etc.

The role of deceptive pictures in social networks is also high, fueling the feeling that everyone around is happy and has achieved high results in work, personal life, self-development, etc.

What threatens the impostor syndrome

The syndrome creates real problems at work. For example, a person with impostor syndrome is afraid to take on a new business. He doubts himself, so he delays the start of work or brings it to the ideal for too long [6].

People with the syndrome deliberately set themselves easier goals, do not show initiative and refuse interesting offers [7]. They may ask for a lower salary than their peers or not talk about new ideas [8].

How to overcome the impostor syndrome

The phenomenon itself can be useful and play into our hands: for example, the fear of exposure makes us constantly develop in our field, take courses and learn new things, double-check our work and bring it to perfection. But the lack of state control can also be devastating.

If you understand that all of the above is about you, you can do the following:

- take an objective look at your achievements;

- write down the areas in which you have been successful;

- consider all the factors and causes that you think have influenced him;

- think about how much, in your opinion, each of the factors contributed to the achievement of a specific goal and put a number in front of it as a percentage. At this stage, it may turn out that you mistakenly attribute all your successes to luck, but putting it on paper, you will understand how stupid it looks.

Often "imposters" do not perceive any result other than perfect, so they need to learn to accept mistakes and failures. It's important to remember that you can't (and shouldn't) always be perfect, you can just be good enough at what you do.

It is also important how we ourselves perceive what is happening. As coach and consultant Kim Meninger writes [9], the feelings of excitement and anxiety are very similar from a physiological point of view, so sometimes you can just set yourself up for other experiences.

“Instead of thinking, 'I'm doomed to failure. Everyone will know that I am not suitable for this, it is better to tune in to the thought: “I am now very excited and looking forward to this adventure!”, And then the fear will be replaced by anticipation, ”advises Meninger.

The impostor syndrome is strongest when you leave your comfort zone. And every time you experience it, you get a signal that you are moving forward, developing.

The next time you feel impostor syndrome, sincerely congratulate yourself that you could stay in a comfortable, predictable position, avoid anxiety, and do the same job year after year for which you are too highly qualified without revealing your potential and regretting it, writes Meninger.

RBC's meditation podcast on fighting the impostor syndrome

It is important to approach your successes and failures critically, evaluating all the parties that could influence the current situation. But excessive self-criticism can lead to a deterioration in the mental state.

One of the ways to avoid destructive thoughts is the right attitudes and meditation exercises from the Time to Stop podcast.

What to read about impostor syndrome

- Podcast: why dealing with impostor syndrome is so hard (ENG)

- Dealing with Impostor Syndrome During Quarantine

- How Imposter Syndrome Affects Shopping Enjoyment

- The world chess champion told how to build self-confidence

detailed analysis. Scientific research, characteristics, tests and how to deal with it - Careers on vc.ru

There are many myths and opinions around the "impostor syndrome". Together with Elena Stankovskaya, Ph.D. in Psychology, a practicing consultant and teacher of the People Mindset practical online course, we analyzed in detail what this phenomenon is, whether it is necessary to fight it, and how it manifests itself in different people.

98 876 views

"Imposter Syndrome" is not a medical diagnosis, but rather a name for a set of experiences that are understandable and close to different people. We recognize ourselves when we read about this "syndrome", although there is no single cause behind the list of manifestations. This is similar to a temperature or a runny nose - in themselves they are not some kind of disease and can occur from a sore throat, flu, acute respiratory infections, or something else.

We recognize ourselves when we read about this "syndrome", although there is no single cause behind the list of manifestations. This is similar to a temperature or a runny nose - in themselves they are not some kind of disease and can occur from a sore throat, flu, acute respiratory infections, or something else.

From the point of view of Soviet clinical psychology, a "syndrome" is a group of symptoms that naturally manifest themselves together due to a common effective cause. And the authors of the term believed that such a reason exists for the impostor syndrome, but later studies have refuted this opinion.

It is now believed that although the "syndrome" reflects real experiences, there are very different mechanisms behind it - and therefore it is much more effective to work with these experiences separately than to separate them into a separate "syndrome". In this sense, the original term “imposter phenomenon” is more accurate - many people actually perceive their success as an accident and are afraid of exposure: they say that others will figure it out and understand that they do not correspond to their position or qualifications.

When clients come to me and complain about "Imposter Syndrome", I understand that this is their way of framing the problem. People come across articles about the "syndrome", and its description resonates, seems familiar and close. So I’m clarifying exactly how the “syndrome” manifests itself, what specifically worries people - because there are many reasons why we cannot appropriate success or are afraid of exposure. After I got acquainted with the client’s unique experience of “impostering”, we together try to understand what amplifies these experiences now, what events from the past have shaped them, and look for other ways to perceive ourselves.

Elena Stankovskaya

Scientists on "Imposter Syndrome"

1979 Paulina Klance and Susan Imes published "The Impostor Phenomenon Among High Achieving Women", which pioneered the term "Imposter Syndrome". They studied women who achieved objective career success but still felt like cheaters. According to Clans and Imes, "Imposter Syndrome" is a kind of "internal experience of intellectual falsity" in people who cannot stomach their success. They concluded that the “syndrome” has six characteristics (more on these in the next section):

According to Clans and Imes, "Imposter Syndrome" is a kind of "internal experience of intellectual falsity" in people who cannot stomach their success. They concluded that the “syndrome” has six characteristics (more on these in the next section):

- Impostor cycle.

- The desire to be special or to be the best.

- An aspect of superman/superwoman.

- Fear of mistakes or failure.

- Denying one's own competence and ignoring praise.

- Fear and guilt for one's own success.

1985 Harvey and Katz defined "Imposter Syndrome" as "a psychological pattern rooted in a strong and hidden feeling of being a con artist when something needs to be achieved." According to them, the "impostor syndrome" should have three signs:

- Belief that you are deceiving other people.

- Fear of being exposed.

- Failure to recognize one's achievements, abilities, intelligence or qualifications.

1991 Colligian and Sternberg coined the term "perceived fraud" to avoid confusion between "Imposter Syndrome" and commonplace fraud. They didn't see impostor syndrome as an emotional disorder, but as a combination of cognitive and affective elements—that is, a fixed thought pattern.

2005 Kets de Vries studied the phenomenon of deception and included "Imposter Syndrome" in it. He considered cheating to be a social norm - after all, we must hide our weaknesses and stay within the generally accepted standards of behavior. According to Kets de Vries, going beyond this gives rise to two extremes: unethical deception (banal fraud) and neurotic deception (that is, the “impostor syndrome”). Consider what he understood by the norm and extremes.

- Norm. Each of us is an impostor, because we strive to conform to some ideas of others and demonstrate a public self that is different from our real ones.

- Real impostors. They display a false identity to deceive others and are satisfied when they succeed. Such people may have a real fear of exposure.

- Neurotic impostors. Their experience of cheating is subjective, meaning they don't do anything truly unacceptable. Such people feel like deceivers regardless of the opinion of outsiders. They are characterized by fear of failure or success, perfectionism, procrastination, workaholism.

All scientists' definitions agree on one thing: "the impostor syndrome" is the subjective psychological experience of a person who is afraid of exposure and is sure that he is a deceiver.

Elena Stankovskaya — Candidate of Sciences in Psychology, Consultant Psychologist, Associate Professor at the National Research University Higher School of Economics, author of the book Transactional Analysis: 7 Lectures for the Magisteria Project. She leads the Imposter Syndrome module in the People Mindset Leadership module, a hands-on online course on teamwork and leadership skills.

It starts October 5th.

Characteristics of "Imposter Syndrome" according to Clans and Imes

Paulina Klance states that if a person has at least two of the above characteristics, he is subject to the "impostor syndrome". Let's analyze them in more detail.

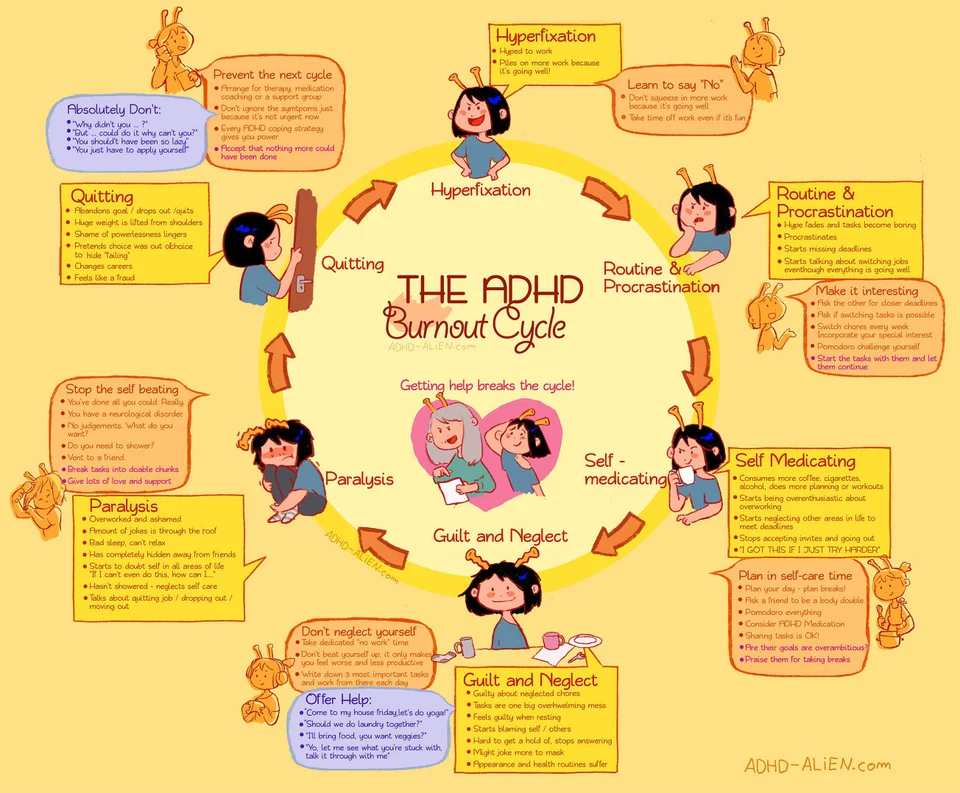

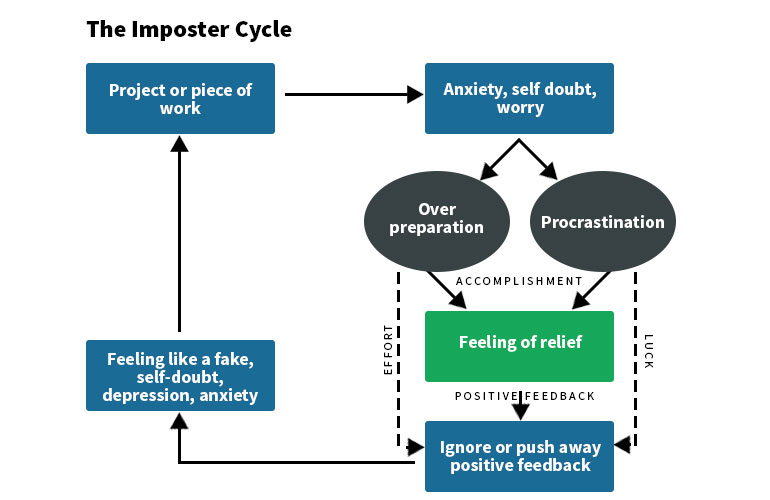

Imposter Cycle

The impostor cycle begins when a person faces the need to achieve something - for example, study or a project at work:

- Anxiety arises in a person.

- Anxiety provokes either overpreparation or procrastination. Moreover, procrastination is followed by a stage of intense “doing” - after all, you have to meet the deadline.

- When a task is completed, there is a sense of relief and accomplishment. But this feeling passes quickly.

- People around give positive feedback, but the person does not accept it, because it does not correspond to his perception of the mechanism of success, and does not believe that success is related to his abilities.

- If the second stage was overpreparation, the person believes that success is due to hard work. If there was procrastination in the second stage, then he explains the success as random luck. At the same time, a person firmly believes that achieving a result through hard work does not confirm his abilities.

- Then the person is faced with a new challenge, self-doubt causes anxiety and the impostor cycle repeats.

The impostor cycle has two permanent effects - overload and increased sense of fraud.

Overload. Occurs due to the fact that the efforts and energy spent on achieving the goal significantly exceed the necessary ones and interfere with other priorities. Moreover, people with the "impostor syndrome" are aware of this problem, but in practice they almost never can break this pattern of behavior and limit themselves only to the necessary efforts.

Increasing sense of fraud from cycle to cycle. Paradox: every time the success is repeated, the "impostor syndrome" only gets worse. Paulina Klance suggested that the "imposters" have their own ideal of success and excessive expectations from the goals achieved. They simply ignore their accomplishments if the actual performance falls short of their ideal standard. At the same time, “imposters” are high achievers who unreasonably rate their work low, which means that each achievement further emphasizes the gap between real and imagined standards of success, reinforcing the “imposter syndrome”.

Paradox: every time the success is repeated, the "impostor syndrome" only gets worse. Paulina Klance suggested that the "imposters" have their own ideal of success and excessive expectations from the goals achieved. They simply ignore their accomplishments if the actual performance falls short of their ideal standard. At the same time, “imposters” are high achievers who unreasonably rate their work low, which means that each achievement further emphasizes the gap between real and imagined standards of success, reinforcing the “imposter syndrome”.

Imposter Cycle - from "The Impostor Phenomenon", Jaruwan Sakulku, James Alexander

The need to be special, the best

Often people with "Imposter Syndrome" secretly want to be better than their peers or colleagues. All their childhood they could be the first in the class or school, but when they come to the university or get a job, they understand that there are many outstanding people in the world, and their talents are not phenomenal. As a result, "imposters" simply ignore their abilities and conclude that they are simply stupid.

As a result, "imposters" simply ignore their abilities and conclude that they are simply stupid.

Superwoman/Superman Aspects

This item is closely related to the previous one. People with Imposter Syndrome demand perfection from themselves in all areas of life. They set themselves almost unattainable standards, and then feel overwhelmed and disappointed.

Fear of failure

"Imposters" are very worried when it is necessary to achieve something - they are terribly afraid of failure. Making mistakes or not doing everything to the highest standard, they feel shame and humiliation. For most people with Imposter Syndrome, it is fear that becomes the main driver. Result: They try to reduce the risk of failure and start working too hard.

Feeling incompetent and underestimating praise

People with "Imposter Syndrome" cannot accept compliments and believe in themselves, they tend to attribute success to external factors, ignore positive reviews and objective measures of success. Not only that, they are making efforts to prove to everyone: we do not deserve praise, this is not our achievement. But "Imposter Syndrome" is a much deeper and more serious phenomenon than coquetry or false modesty.

Not only that, they are making efforts to prove to everyone: we do not deserve praise, this is not our achievement. But "Imposter Syndrome" is a much deeper and more serious phenomenon than coquetry or false modesty.

Fear and guilt about success

"Imposters" often feel guilty about being different from others or doing better than others - they are very afraid of being rejected. Another of their fears is excessive demands or expectations from others. "Imposters" are not confident that they can maintain their level of efficiency and refuse additional responsibility, and excessive demands or expectations can "reveal" their "deception".

When and why to go to a psychologist

If you have found in yourself at least two of the characteristics from the last chapter, then you have an "impostor syndrome". But it is not always necessary to get rid of it - only if the "syndrome" interferes with living or building a career. As a first approximation, this is easy to understand:

- Career.

A person does not pretend to what he could get and what he deserves - it seems to him that they are deceiving everyone even in their current position. Although in fact he has qualities that would benefit the company in a higher position.

A person does not pretend to what he could get and what he deserves - it seems to him that they are deceiving everyone even in their current position. Although in fact he has qualities that would benefit the company in a higher position. - Quality of life. Most of the energy and nerves are spent not on doing the job, but on avoiding exposure, over-preparing for projects, internal struggles and servicing their doubts.

Paulina Klance has developed a test that helps determine the degree of development of "Imposter Syndrome".

"Imposters" often choose some kind of role model for themselves - the very image of a "smart brother" or "smart sister" that they aspire to. Moreover, it can be both a living person and a historical figure, as in Mayakovsky's "Letter to Comrade Kostrov":

... break loose,

jealous of Copernicus,

him,

and not Marya Ivanna's husband,

considering

his rival

.

But even if a person with "Imposter Syndrome" achieves his goals and objectively outgrows this ideal image, he will not get rid of problems, but will continue to spend energy on fighting fear and doubt. In this case, there can be two scenarios:

- We do not notice at all that we have outgrown our role model, and imperceptibly we switch to comparison with the new Copernicus.

- We say that we were just lucky, it's just a case, luck, or colleagues and relatives helped us in time, and we continue to consider this person better than ourselves.

As a result, the life scenario does not change, but a distorted perception appears: we take only those facts that confirm our idea of ourselves. And a mental system is built that supports itself with all its might, ignoring the facts that contradict it.

Another reason to tackle this topic is the avoidance behavior that underlies the "Imposter Syndrome". If you often choose an activity that helps to hide that you don’t know something, refuse new heights, self-expression, hide your thoughts because of fear, this is an occasion to reconsider your ideas about yourself. Having dealt with all this, we get more freedom - we can choose activities not out of fear, but based on what turns us on and what we really want.

If you often choose an activity that helps to hide that you don’t know something, refuse new heights, self-expression, hide your thoughts because of fear, this is an occasion to reconsider your ideas about yourself. Having dealt with all this, we get more freedom - we can choose activities not out of fear, but based on what turns us on and what we really want.

The basis of the "syndrome" is an internal conflict

The impostor syndrome is paradoxical: I feel like a deceiver, but at the same time I know that I am not, it is just a "syndrome". That is, some part of me believes in my strength and that I receive recognition deservedly.

Consider an example: a woman works in a male team, in a position that is traditionally considered “male” in society. And they certainly face a negative attitude towards themselves, depreciation of their work, distrust. Such an attitude of others reinforces internal doubts about competence, but a woman does not quit, moreover, she strives to grow and build a career. Thus, under these doubts, inner confidence is almost always hidden - no, after all, I am smart, capable. I attribute my success to chance, and at the same time I think that when I do this, it's a "syndrome".

Thus, under these doubts, inner confidence is almost always hidden - no, after all, I am smart, capable. I attribute my success to chance, and at the same time I think that when I do this, it's a "syndrome".

As a result, "Imposter Syndrome" is not some kind of total insecurity, but a constant tension between confidence and doubts about one's abilities. After all, if a person is sincerely sure of his incompetence, then why should he achieve something? He will live quietly at his level and will not strive for something great.

And there may be different causes and manifestations. Many people have the illusion that if they were truly smart, then everything would work out very easily for them - and in any area. Roughly speaking, if a person from year to year cannot master some narrow part of his work, then he gets the feeling that in other areas he is a complete zero. The stereotyped idea that truly smart people do everything almost intuitively is to blame for this: they get behind the wheel and immediately know how to drive a car. And if you have to “squirm” at the circuit for 20 hours in a row, then you are definitely an impostor and a deceiver.

And if you have to “squirm” at the circuit for 20 hours in a row, then you are definitely an impostor and a deceiver.

There is also a second frequent manifestation: it is impossible to show that I am proud of myself, that I am cool or cool. And here the reason may be hidden in childhood, when a pattern of behavior is imposed on the child: do not stick out, do not attract attention, do not show your success, sit silently and quietly, hide. There are also more individual cases.

We write about product management and development in the make sense and Product Mindset telegram channels, and you can discuss any product issues in Product Sense Chat.

For example, a talented and bright student transfers to another school, and there his talents are not appreciated and there is no opportunity to show them - they are simply of no interest to anyone. And when in the future some “strange” people come to him and say: you are very smart, cool, you are doing great, he cannot believe them, because he has already formed a strong opinion about himself.

It turns out that the core of the "impostor syndrome" is script beliefs and basic ideas about ourselves, as well as how others perceive us. And even if I have accumulated a large collection of external achievements, my strong inner conviction is no longer disputed. Because scenario beliefs support our picture of the world, stabilize it, shape the perception of reality. A simple example: if I was a black sheep at school - smarter and more talented than others, and therefore they told me all the time that I was not ok, then when people suddenly start praising me, then my patterns do not allow this praise to be digested and I think they are wrong or some weird ones.

Causes of the "Imposter Syndrome"

"Imposter Syndrome" is a popular subject of research, but scientists are still arguing about the reasons for its appearance. Some point to the influence of the family atmosphere in childhood, others emphasize the importance of character traits such as neuroticism, and still others explore the problems of minorities in work teams - national, gender, racial, social.

Paulina Klance and Susan Imes found two typical scenarios in the childhood of women with "Imposter Syndrome":

- A smart brother or sister, with whom they were constantly compared and to whom they have been trying to grow up all their lives, to prove to everyone that they are also worth something.

- As children, they were praised a lot and told that with their abilities they could overcome any obstacles. But as they grew up, they understood: much is given to them with difficulty, which means that they are not as good as everyone thought.

In 2006, Julie Vaunt and Sabina Kleitman conducted a study and found out an interesting fact: the fears of "imposters" are very much dependent on excessive care and custody from the father, and the mother's parenting style affects them only indirectly - as a reflection of the father's style.

Another “syndrome” arises because of the cult of intellect in the family — and then the “imposters” do their best to change their behavior, meet the family's standards and please their parents in order to keep or earn their love. Even to the detriment of their nature and desires. If the family does not give support and approval to the child, he thinks that his achievements are not interesting or impressive to anyone. And then there is shame, a feeling of humiliation and a feeling - I am an impostor.

Even to the detriment of their nature and desires. If the family does not give support and approval to the child, he thinks that his achievements are not interesting or impressive to anyone. And then there is shame, a feeling of humiliation and a feeling - I am an impostor.

"Imposter Syndrome" is also associated with the Dunning-Kruger effect, when low-skilled people overestimate their abilities, while professionals tend to doubt their abilities, feel insecure and consider others more competent. As in the story about Socrates: he proved to his students that he did not know much more than they did. Socrates drew two circles - the small one showed the amount of knowledge of the students, the large one - his own knowledge. The zone of the unknown is that which is in contact with the circle, which means that Socrates does not know much more than his students.

The Dunning-Kruger effect is also correlated with research by Jim Collins, which formed the basis of the book Good to Great. Collins speaks of five levels of leaders, of which we are only interested in levels four and five, the highest levels of leadership development.

Collins speaks of five levels of leaders, of which we are only interested in levels four and five, the highest levels of leadership development.

- The manager of the fourth level attributes all the achievements of the company to himself, his qualities and insight, and they tend to shift the responsibility for failures to others. For such a leader, success is a natural consequence of his own talent, he is confident in himself, knows how to speak brightly and motivate the team.

- Level 5 leaders almost always say “we”, “just lucky”, “there were very talented people in the team”. Such leaders outwardly look uncertain and modest, they look for the reasons for failures in their decisions and actions, they motivate by their own example, and not by incendiary speeches. At the same time, they have a strong will and desire to succeed. Long-term success for companies is usually driven by Level 5 leaders.

Who is subject to "Imposter Syndrome"

Klance and Imes considered the "imposter syndrome" a social phenomenon: successful women were much more likely than their male counterparts to believe that their success was accidental, and those around them would never give them grants and recognition if they understood the situation better. At first, the authors associated the "syndrome" with social inequality, discrimination, and the position of women at the time - women were not considered capable of leading or achieving anything serious outside the household.

At first, the authors associated the "syndrome" with social inequality, discrimination, and the position of women at the time - women were not considered capable of leading or achieving anything serious outside the household.

But in 1993, after a series of studies, Pauline Klance confirmed that men also often become victims of the “impostor syndrome”. In general, up to 70% of people go through this “syndrome” at least once in their lives (The Impostor Phenomenon), among which there are many successful and famous people. Michelle Obama, Tom Hanks, famous writer John Steinbeck, actress Jodie Foster, and even Einstein shared their feelings about the "Imposter Syndrome" at various times.

Types of "imposters"

Manifestations of "Imposter Syndrome" vary from person to person. For example, a “narcissist” considers himself exceptional and is afraid that others will suddenly figure him out and say: you are ordinary, like all of us. And an anxious person will not be able to establish himself in some kind of positive opinion about himself and will each time try to build it anew.

Valerie Young, an expert on "imposters", created a classification of people subject to this "syndrome".

- Perfectionists. They set themselves an overstated bar, and then even if they achieve goals by 99% feel like failures. Any mistake - and they doubt their competence.

- "Experts". Constantly going to trainings and accumulating certificates, trying to get too detailed information before starting any project. They are afraid of looking stupid, so they are embarrassed to ask questions in meetings or in class. They will not take on the project if they do not meet all the formal criteria specified in the requirements.

- "Natural Geniuses". They got used to the fact that in childhood everything was easy for them. Therefore, when you have to work hard to achieve a goal, they consider it a sign of their incompetence.

- Soloists. They feel that they are obliged to do everything on their own, and asking for help means signing their insolvency.

- "Supermen" / "Superwoman". Force themselves to work harder than others to prove their level. Trying to succeed in all areas of life - at work, in the family, in relationships - and can experience severe stress when something does not work out.

Development driver and stable worldview

There are pluses in the "impostor syndrome" - it stabilizes the picture of the world, structures our activity and time. Yes, we doubt, but we have a stable understanding - I am a deceiver and I know that I should be afraid of being exposed. This is a very stable and predictable picture of the world. But when we are told: you are doing everything great - we are lost and do not know what to believe, this creates a conflict with our picture of the world and we say: no, this is how I am and this is what I should be afraid of.

Because of the "Imposter Syndrome", people invest a lot of time in their studies and work, in developing their professional skills. And then our "syndrome" becomes a driver of personal development. Behind this process is the desire to realize our inner conviction that we are smart and talented after all. As a result, a person really does a lot of work, pumping much more intensively and deeper than those who do not consider themselves a deceiver. And although subjectively the “imposter” cannot appropriate success for himself, but objectively, deep inside, he understands that this is true, I did it. And this understanding gives a certain happiness.

And then our "syndrome" becomes a driver of personal development. Behind this process is the desire to realize our inner conviction that we are smart and talented after all. As a result, a person really does a lot of work, pumping much more intensively and deeper than those who do not consider themselves a deceiver. And although subjectively the “imposter” cannot appropriate success for himself, but objectively, deep inside, he understands that this is true, I did it. And this understanding gives a certain happiness.

Strategies for dealing with "Imposter Syndrome"

There are two ways to get rid of the vivid manifestations of the “impostor syndrome”: with the help of quality feedback, a psychologist, or on your own.

Feedback. Despite the stable picture of the world of "impostors", the development of the "syndrome" depends very much on the quality of the feedback. When there is strong, supportive and realistic feedback, a person gradually develops an adequate self-image.

We recommend two episodes of the make sense podcast about team relationships: About conflicts and difficult situations in a team, and about the role of emotions and trust in relationships with Andrey Ryzhkin, About company culture and values, remote work and mental health with Anna Boyarkina

Psychologist. Turning to a psychologist and understanding with him why the “syndrome” has formed and what to do with it is a good method. Together with a specialist, you can go from the present to the past and answer important questions:

- What is supporting these doubts right now?

- Are there people who believe in my client's competence and talent?

- What kind of feedback does he get and what achievements can he really be proud of?

- Why does he think that these achievements do not belong to him?

- What are the benefits of doubt?

- Who does the client consider smart and talented, who does he look up to? Where did this level of ambition come from?

Then you can go into the past and understand how and when the "impostor syndrome" was formed:

- In what relationship did this feeling and self-image arise?

- What experience fixed the "syndrome", and what - vice versa?

- How does the client now confirm his competence and what gives him?

If you passed the Paulina Clans test and it showed a very high level of development of the "impostor syndrome", you should contact a specialist - he will help you make the "syndrome" your friend and growth driver, and not a development blocker that enslaves and prevents you from realizing yourself.

How to properly communicate with those who are prone to impostor syndrome, build healthy relationships with the team and the world around it, be a leader who helps others grow and grow yourself through it, as well as how to better understand your strengths and weaknesses and use it for development , we analyze in detail on the People Mindset course together with teachers from Miro, Vyshka, CIAN, Skyeng and other leading companies.

Alaina Levin's Advice: How to Deal with Impostor Syndrome on Your Own

Alaina is a STEM career consultant and author of Networking for Nerds (Wiley, 2015).

You are a driver. "Imposter Syndrome" is just a fantasy. It is based only on your opinion, not facts. It is a subjective internal, not an objective external process. But you manage yourself, and therefore, you can quite fight the “syndrome”. This will give strength.

Don't hide from your emotions. During the "fits" of impostor syndrome, you may experience insecurity, fear, shame, anxiety, and other negative emotions. But that's okay - allow yourself to experience them and write down how you feel. This will help you understand how impostor syndrome affects you, and in the future you will already clearly understand when it manifests itself.

During the "fits" of impostor syndrome, you may experience insecurity, fear, shame, anxiety, and other negative emotions. But that's okay - allow yourself to experience them and write down how you feel. This will help you understand how impostor syndrome affects you, and in the future you will already clearly understand when it manifests itself.

Get angry! But not on yourself: “Who does this syndrome think it is? And why the hell is he whispering to me that I'm unworthy of my position? Let's get out of here!" Giving vent to your anger, you understand: no one will convince you that you are in the wrong place.

Review your professional experience. Remember all the completed projects, skills, interesting solutions to work problems, review your presentations, documents. These are your real achievements, facts, not fantasies. Such a review will help to counter the subjective “arguments” that the “syndrome” palms off.

Try to prove that you are an impostor. When you're reviewing, ask yourself why you're objectively unfit for the position or an impostor. When you have collected such facts, note those that are associated with emotions. You will see, you will have almost no real arguments left.

When you're reviewing, ask yourself why you're objectively unfit for the position or an impostor. When you have collected such facts, note those that are associated with emotions. You will see, you will have almost no real arguments left.

Look around. Who else has achieved such success? Did they have the same “necessary” training that you are supposedly required to have? If they are successful, then so can you.

Keep moving forward. Constantly take small steps that will instantly demonstrate that you are not an impostor and help you move up the career ladder. Publish an article, do a little research, agree on cooperation with an interesting person. Also, try incorporating flow state into your work.

Be kind to yourself. It takes resilience, flexibility, and courage to beat the impostor syndrome. Constantly remind yourself that I am not a fraud and would never have received such a position and responsibility if I was stupid. Praise yourself when you manage to calm the manifestations of the “syndrome”. But remember - he can come back at any moment. So relax and if necessary return to the first point - act iteratively, over time it will get better and better.

But remember - he can come back at any moment. So relax and if necessary return to the first point - act iteratively, over time it will get better and better.

Contact support

It seems that everything is simple, but science has again made its corrections. In 2019, a group of scientists published a study on "Imposter Syndrome". It turns out that it is very important to ask for support outside of the area in which you feel like an "imposter". Doing Data Science? Seek support from your grandmother, brother, accountants or PR friends. Do you work in marketing? Contact turners, logisticians and managers. Outsiders often see our competence better and are able to assess our knowledge and skills.

In the sources you will find several more effective methods to combat the "imposter syndrome", but they will not work if you really are an impostor - it happens :) These methods have one more limitation: they are able to contain the syndrome, but do not cure his. And if the “impostor syndrome” is highly developed, you still have to figure out its causes together with a specialist.

And if the “impostor syndrome” is highly developed, you still have to figure out its causes together with a specialist.

References

- The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention, Pauline Rose Clance, Suzanne Ament Imes

- A validation study of the Harvey Impostor Phenomenon Scale, Edwards, P. W., Zeichner

- Yes, Impostor Syndrome Is Real. Here's How to Deal With It

- The Impostor Phenomenon, Jaruwan Sakulku, James Alexander

- Imposter phenomenon and self-handicapping: Links with parenting styles and self-confidence

- When Will They Blow My Cove?: The Impostor Phenomenon Among Austrian Doctoral Students

- Impostor phenomenon and mental health: The influence of racial discrimination and gender

- Impostor feelings as a moderator and mediator of the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health among racial/ethnic minority college students

- Good to Great by Jim Collins

- Lecture notes by Ludwig Bystronovsky on how to develop in the profession

- How to banish impostor syndrome, Alaina G.

Learn more