Existential therapy interventions

9 Powerful Existential Therapy Techniques for Your Sessions

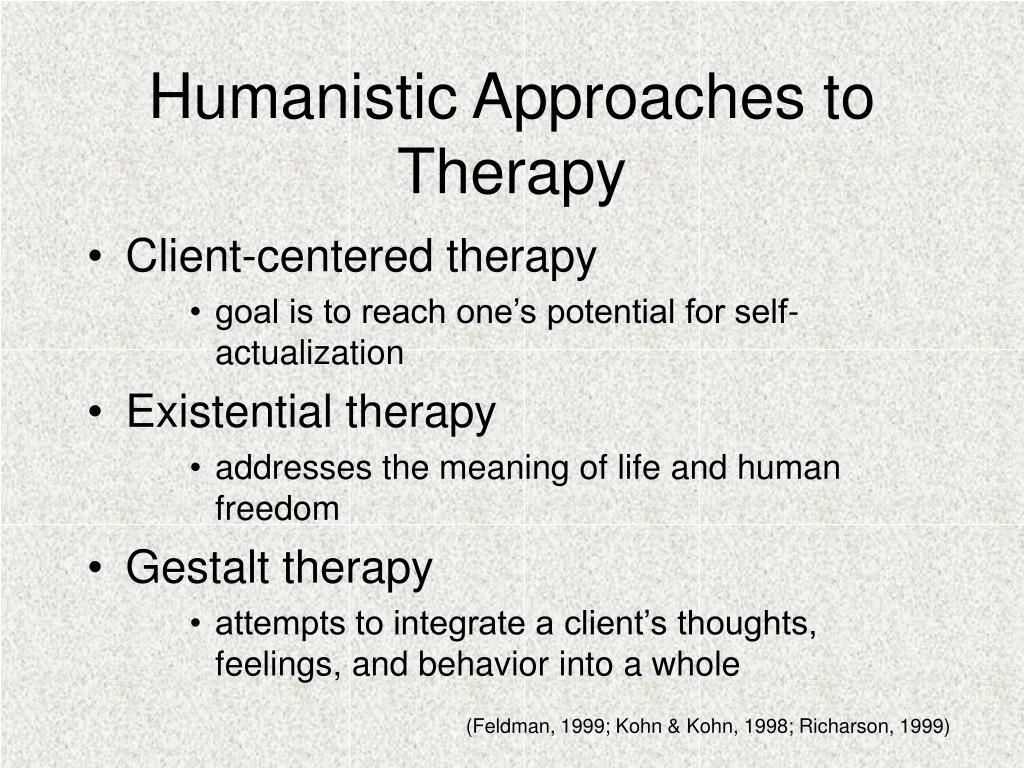

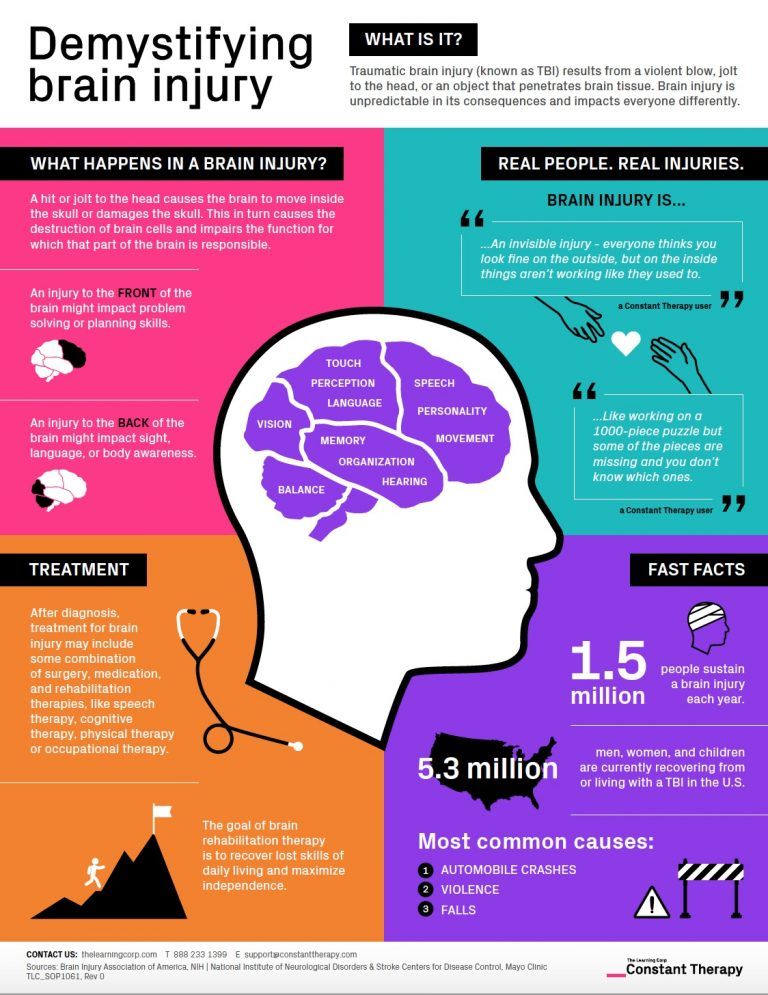

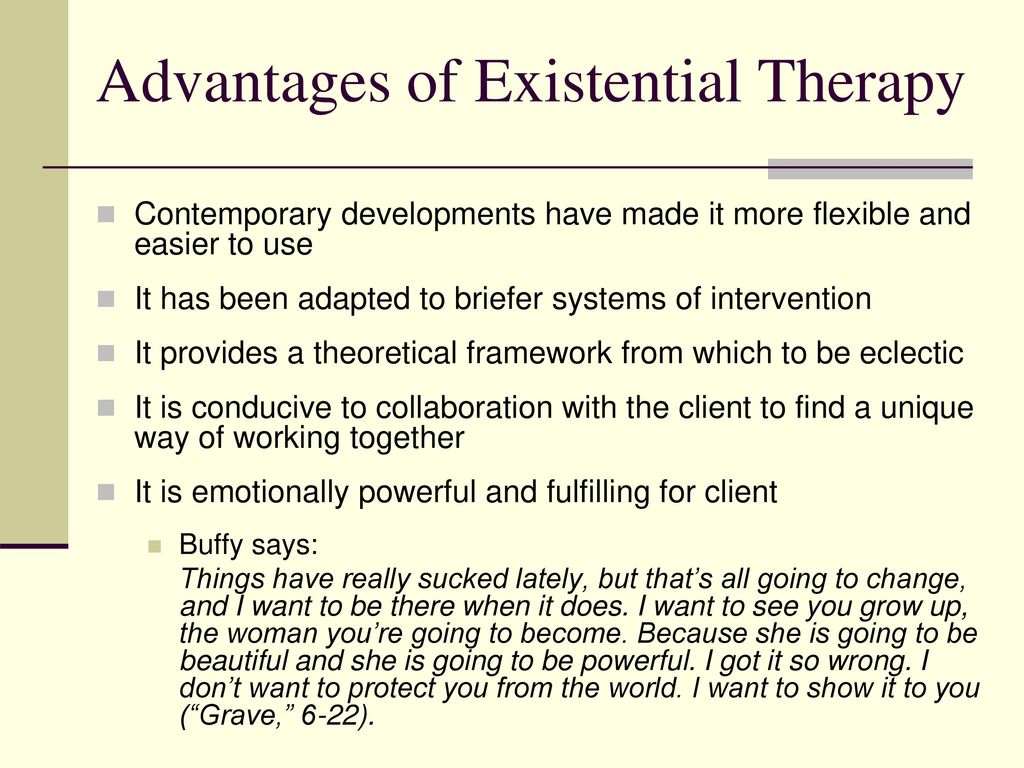

While not easily defined, existential therapy builds on ideas taken from philosophy, helping clients to understand and clarify the life they would like to lead (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

Although there is no single existential therapy, each approach shares the same basic principle that while life is fraught with dilemmas, we choose our values and whether and how we live by them (Adams, 2013).

This article introduces existential therapy before exploring how it is performed. We also provide helpful worksheets, questions, activities, and exercises to equip therapists for each session and support clients.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free. These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- How Does Existential Therapy Work?

- Real-Life Example of a Treatment Plan

- 4 Best Counseling Interventions & Techniques

- 5 Activities & Exercises for Your Sessions

- Helpful Worksheets to Give in Therapy

- 4 Questions to Ask Your Clients

- 3 Fascinating Books on the Topic

- A Look at Our Meaning & Valued Living Masterclass

- Resources From PositivePsychology.com

- A Take-Home Message

- References

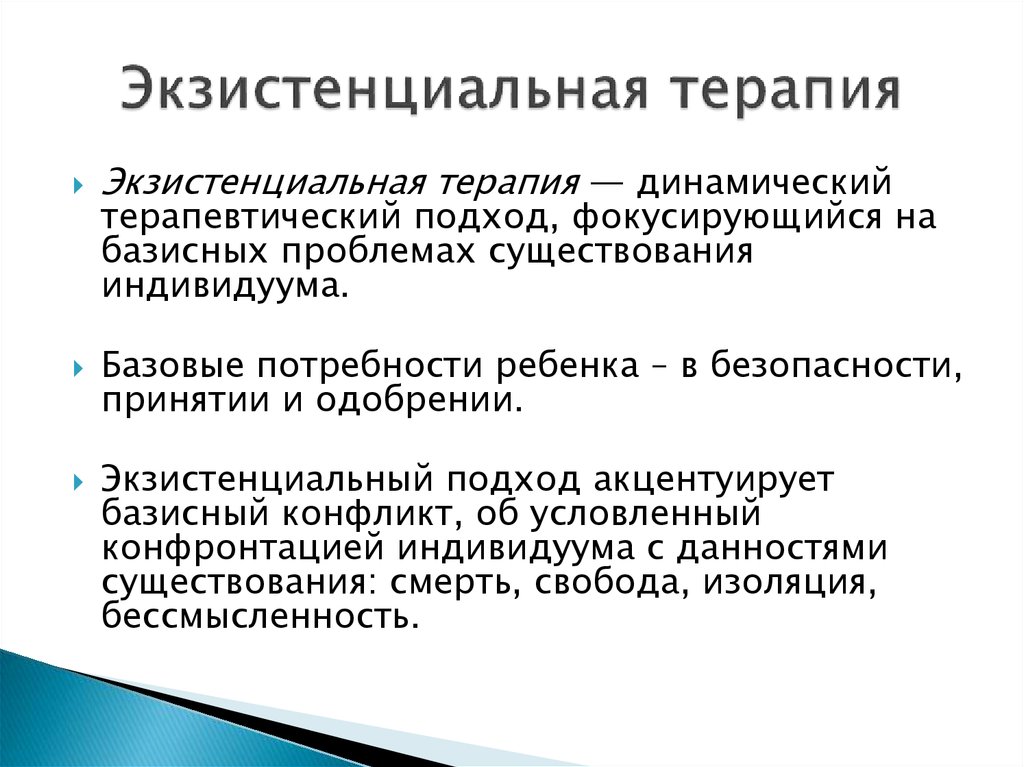

How Does Existential Therapy Work?

“The existential therapist recognizes that we all face certain universal conditions and that the differences between us come down to how we choose to respond to these conditions” (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015, p. 8).

Faced with the certainty of a life that will one day end, some of us try to deny the truth, while others tackle the reality head-on, living life to the fullest.

Existential therapy neither passes judgment nor applies pressure. It aims to uncover the client’s worldview and help them understand their values, beliefs, and attitudes. Once illuminated, the client is free to decide if their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are helping them live a life of meaning (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

It aims to uncover the client’s worldview and help them understand their values, beliefs, and attitudes. Once illuminated, the client is free to decide if their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are helping them live a life of meaning (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

Instead of pathologizing the patient, existential therapists see their role as helping the client reflect on their freedom and clarify “their values and beliefs, and the attitude they take to their world” (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015, p. 9).

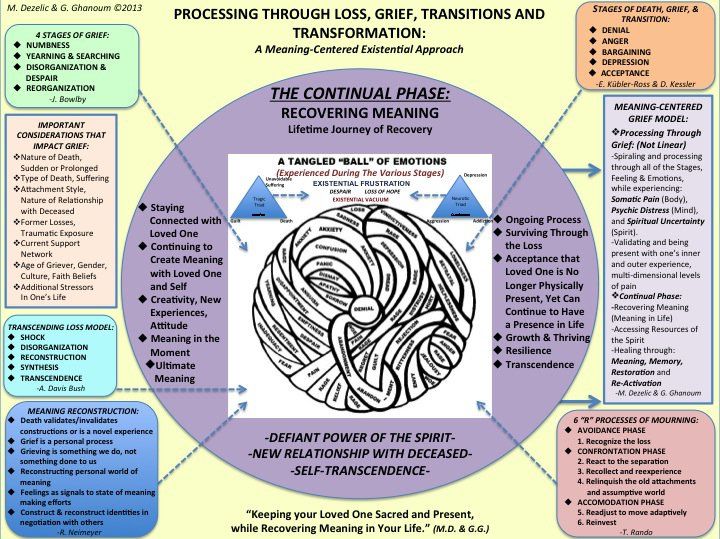

How to use existential therapy for grief

Whether expected or not, the death of a loved one is a shock that we typically hope to get over in order to return to ‘normal’ life. However, we may need to accept that life may never be the same again; and yet, it can still be meaningful and fulfilling (Adams, 2013).

Existential therapists offer clients a safe and supportive space to talk about what finiteness means, for the person they have lost and for their own existence.

How to use existential therapy for depression

Feelings associated with depression can often arise from a sense that we lack the power to make life different. We are left feeling helpless and passive.

Existential therapy suggests that “depression is not something a person has – it is what they are, it is their way of defining their way of being-in-the-world” (Adams, 2013, p. 111). Therapy encourages the person with depression to take risks and reconnect with their world and their autonomy.

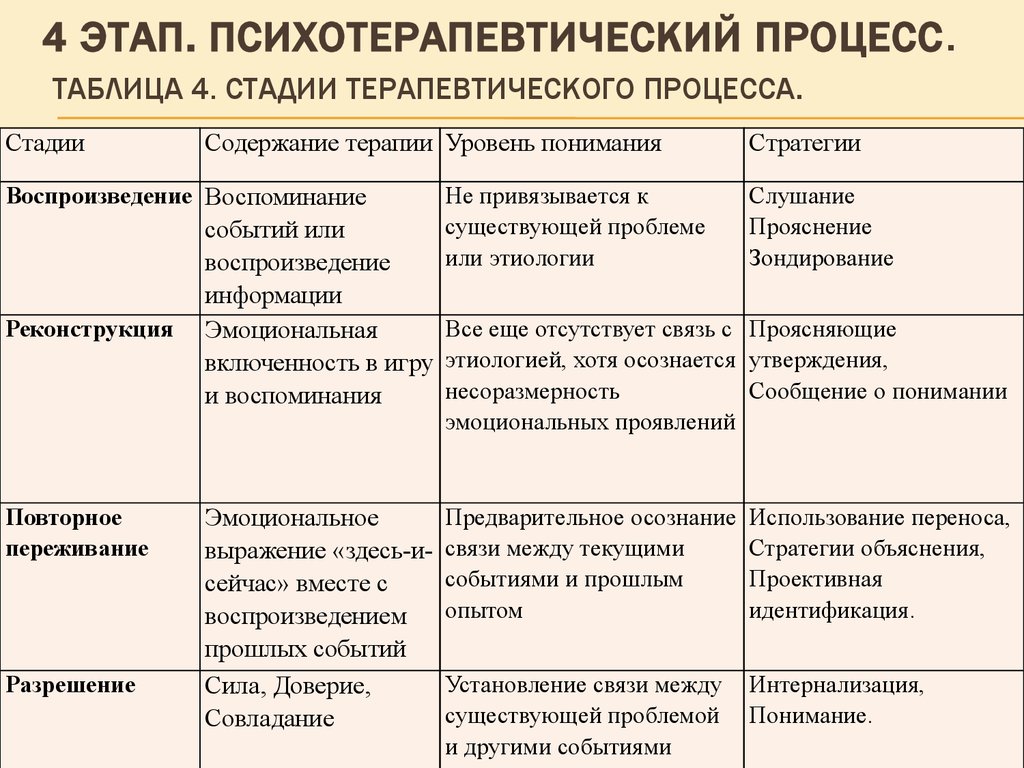

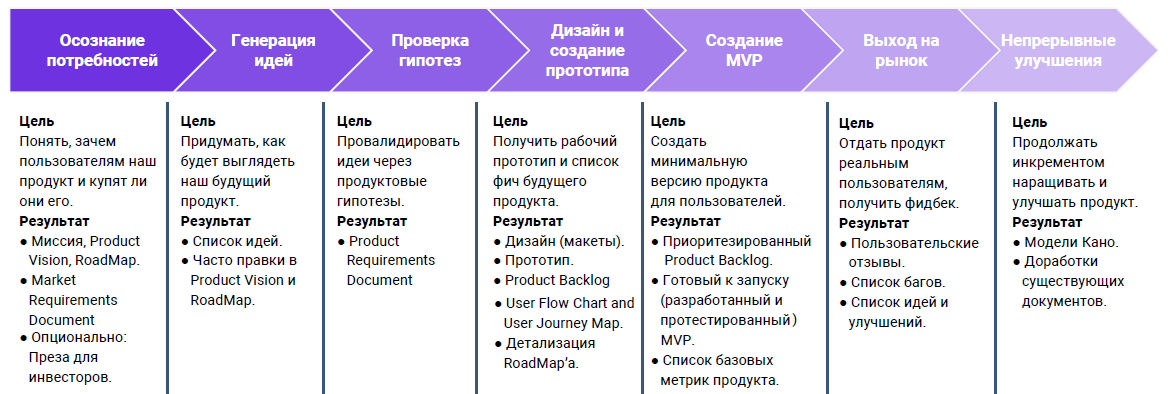

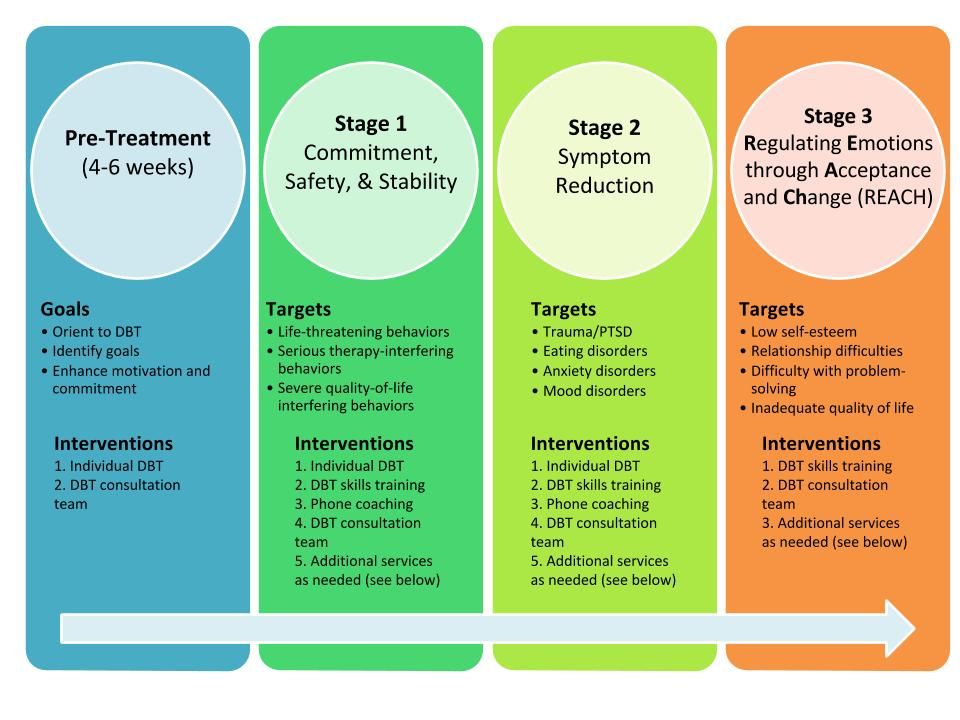

Real-Life Example of a Treatment Plan

The companion website to Skills in Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy (van Deurzen & Adams, 2016) provides valuable videos exploring putting existential theory into practice and turning essential concepts into treatment plans.

Iacovou and Weixel-Dixon (2015) describe the example of bereaved clients attending therapy, where treatment may follow a plan discussing these points:

- Mortality

Recognize that losing someone brings about questions regarding our own mortality.

- Awareness of death

Fostering an understanding that this is not a dress rehearsal; there is only one chance to live this life. - Choice of living

The client is immersed in deciding whether to retreat from life or accept the challenge of choosing how to live. - Handling existential anxiety

An awareness of others’ (and our own) limited lifespan can lead to existential dread and requires support from the therapist.

Existential therapy does not provide a ‘one-size-fits-all’ treatment plan, but instead moves the client through their understanding, providing support along the way as they recognize their values and choices.

4 Best Counseling Interventions & Techniques

Existential therapists adopt an attitude of encouragement when working with clients, using a variety of techniques and interventions to identify and reflect on what is important to them (van Deurzen, 2002; Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

Establishing contact

Similar to other therapeutic styles, in existential therapy the opening session is crucial for stating the therapist’s intention to help the client uncover their difficulties in living. It also provides the opportunity for the client to take stock of strengths and limitations and recognize that the therapist’s role is not to provide empathy or sympathy but to use the existential approach to methodically explore their ability to live (van Deurzen, 2002).

Essential points to clarify in the first session with the client regarding the therapeutic approach include (modified from van Deurzen, 2002):

- Existential anxiety is a feeling of unease associated with becoming aware of our vulnerability.

- Therapy is not aimed at removing anxiety but to find the courage to live with uncertainty.

- Authentic living involves making the most out of life and finding clarity in our goals and intentions.

- Authentic living is a goal, and while never fully achieved, the journey increases enjoyment and vitality.

Exploring the four worlds

The four worlds of human existence help orient the client’s position in the world. They prompt reflection on potentially unsolvable dilemmas and paradoxes that evoke anxiety throughout our lives (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

- Physical world

How we relate to our environment and our mortality, prompting us to ask (Adams, 2013, p. 27):

“How can I live my life fully knowing I may die at any moment?”

- Social world

How we relate to others and the culture to which we belong, prompting us to ask (Adams, 2013, p. 27):

“What are other people there for?”

- Personal world

How we relate to ourselves, including our imagination, and how we see our past and future, prompting us to ask (Adams, 2013, p. 28):

“How can I be me?”

- Spiritual world

How we relate to the unknown, our personal value system, and our vision for an ideal world, prompting us to ask (Adams, 2013, p. 28):

28):

“How should I live?”

The therapist listens for which world, or worlds, has prominence or have been neglected by the client.

Mapping the client’s worldview

The client’s worldview consists of their “attitudes, expectations and assumptions with respect to self, other and the world” and is essential to make sense of and give meaning to our place within a constantly changing world (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015, p. 106).

The therapist works with the client to identify and map their worldview. Once understood, the client can begin to see where specific strategies may restrict their chance of leading a fulfilling and meaningful life (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

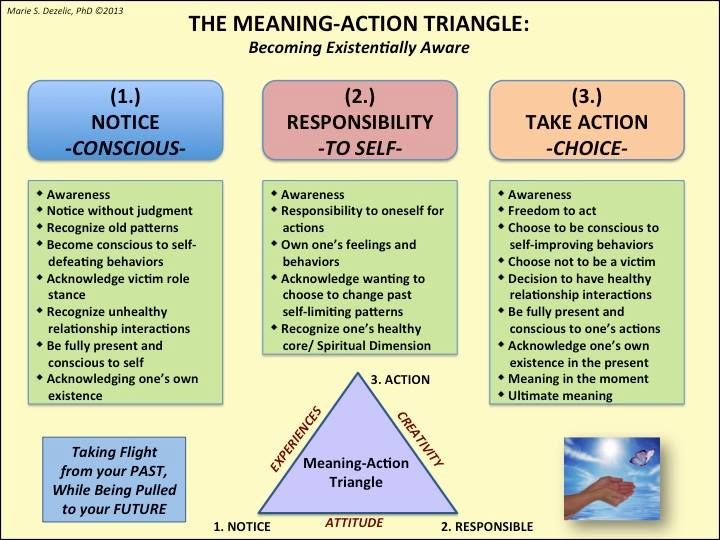

Choosing and changing

In existential therapy, the client is encouraged to take ownership of their choices. They learn to see their existing reality more clearly and recognize their contribution to the situation.

The client is encouraged to take responsibility for consequences and recognize that authentic living requires taking risks.

5 Activities & Exercises for Your Sessions

Existential therapy requires becoming aware of our values and beliefs and identifying whether we behave in line with them.

The following activities and exercises contribute to the client’s understanding of their existing and potential reality.

Denial of responsibility

We may talk about our lives in specific ways to assert our lack of responsibility over what happens in them (Adams, 2013), including:

- Substituting “I” with other pronouns (such as they)

- Talking about the past (and even the future) and avoiding discussing the present

- Being reactive rather than proactive

- Seeing ourselves as passive rather than active

Ask the client to consider a time when they used each of the above approaches (or others) to avoid owning their reality:

What was I trying to avoid by talking in this way?

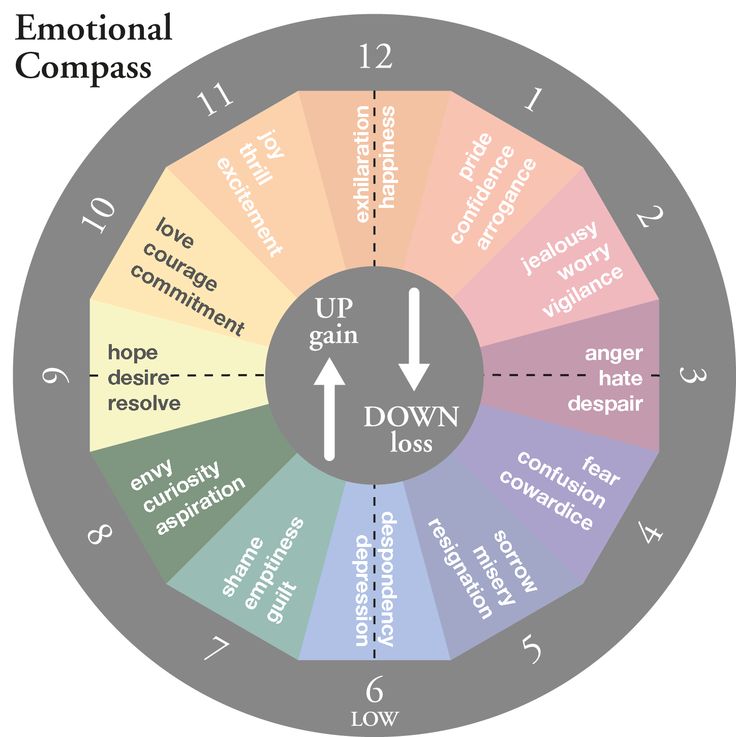

Becoming aware of your emotional vocabulary

When exploring and explaining emotions, we are often limited by our education and personal and cultural history (Adams, 2013).

Ask the client to list 10 of their most familiar emotional states (such as anger, happiness, fear, envy, hopeful, sadness). These are ones they encounter daily.

Then they should ask someone close to them to do the same.

Compare the lists and consider what emotions may have been missed, ignored, or avoided.

Considering values

It can be challenging to live an authentic and meaningful life without a clear understanding of our personal values and beliefs.

Ask the client to consider the following values questions and discuss their answers within the session (Adams, 2013):

How do you want to live your life?

How do you want to treat others and be treated?

How do you build/evolve a sense of overall meaning and purpose?

How do you feel about human existence as a whole?

2 Role-play exercises to try

Role-play can be a safe and fun way to explore emotions, values, and behavior.

Living with values

Having answered the previous question regarding values, take turns within a pair reflecting on how to live according to these values in different scenarios (at work, home, out with friends, etc. ).

).

Each person asks questions of the other regarding what they would do in a real or imagined situation.

For example,

Person one – “How would you interact with the staff in your team at work?”

Person two – “I would be open and honest in my dealings, considering their requests and providing fair responses.”

The role-play aims to encourage each person to see how behavior and talking can reflect personal values.

Most meaningful life

In pairs, take turns interviewing the other person regarding how their most meaningful life might look.

The interviewer makes up the questions, but they may include:

What job would you have in your most meaningful life?

Would you have a partner?

If so, how would you treat and be treated by that partner?

What sort of friends would you have?

The aim is, without judgment, to help the person answering form an image of what a meaningful life might be for them.

Helpful Worksheets to Give in Therapy

The following worksheets offer insight into what a meaningful life might look like for the client and examine the potential for bias from the therapist.

Becoming aware of our assumptions as existential therapists

All of us, including therapists, bring biases into conversations with others.

The Becoming Aware of Assumptions worksheet helps therapists reflect on what biases they carry that could impact the content and effectiveness of a treatment session.

Remembering Our First Times

When reflecting on what is happening in our lives, over-familiarity with events can cloud our feelings.

The Remembering Our First Times worksheet encourages reflection on how something felt the first time it happened and its impact.

Things That Went Well or Badly

Life is always unpredictable. While it can be difficult feeling out of control, we have a say over how we react.

The Things That Went Well or Badly worksheet allows us to reflect on an event that was important and felt like either a success or a failure.

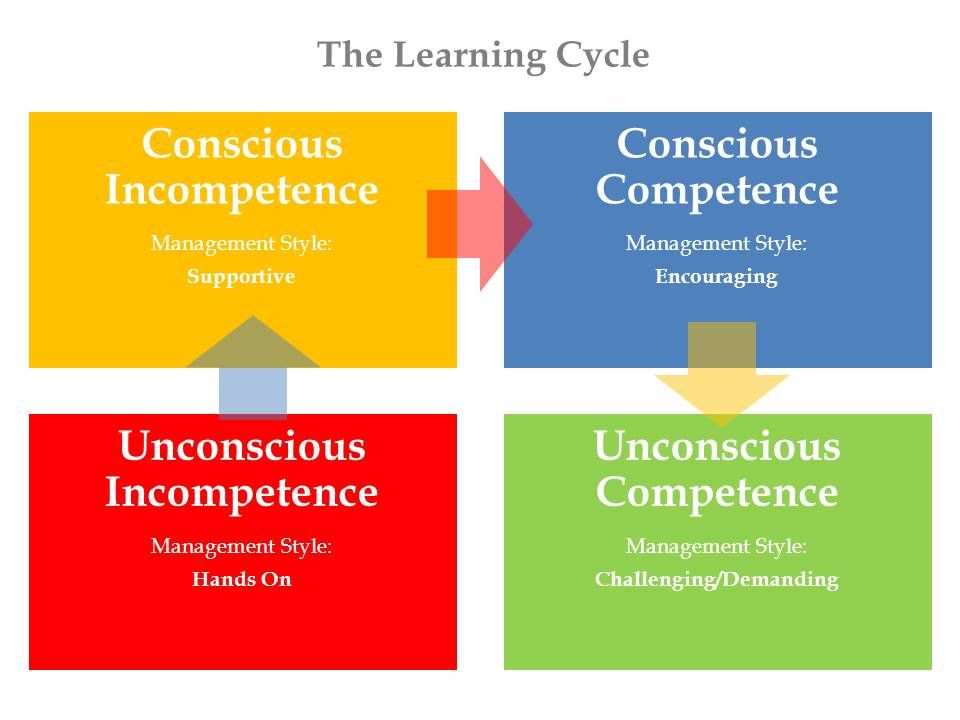

Learning New Skills

Learning new skills can be extremely rewarding, encouraging growth and fostering new opportunities. However, the process can bring anxiety, apprehension, and even fear (Adams, 2013).

The Learning New Skills worksheet helps the client reflect on times they learned new skills to help them normalize and accept the feelings accompanying the growth process.

Four Worlds of Human Existence

As we have already seen, the four worlds of human existence are an essential aspect of existential therapy and can stimulate ongoing reflection in clients (Adams, 2013).

The Four Worlds of Human Existence worksheet can be shared with clients and revisited throughout treatment to encourage the client to reflect on their lives.

Managing Existential Anxiety

Considering some of life’s bigger questions as part of existential therapy can lead clients to experience a sense of fear, known as existential anxiety, that may discourage further work or risk taking (van Deurzen, 2002).

Share the Managing Existential Anxiety worksheet to help them recognize that existential anxiety is normal and consider the positive experiences and emotions they experience in life to maintain a balanced outlook.

4 Questions to Ask Your Clients

The following four questions are incredibly helpful for promoting reflection in clients.

They are very big questions, and it is important to make clear to the client that there are no right or wrong answers, but the act of reflecting is powerful (van Deurzen & Adams, 2016).

What do I intend to do before I die?

How do I get along with my friends, family, and those closest to me?

What do I owe myself in life, and how do I get it?

What are my moral values, and how do I live up to them?

3 Fascinating Books on the Topic

We have included three books that introduce trainees or experienced practitioners to the central ideas behind existential therapy.

1.

Existential Counselling & Psychotherapy in Practice – Emmy van DeurzenThe third edition of this valuable text explores the idea that our problems arise from the essential paradoxes of human existence rather than personal pathology.

This insightful and far-reaching book explores the theory and practical methods for the therapist to help clients understand what constitutes meaning and value in their lives.

Find the book on Amazon.

2.

A Concise Introduction to Existential Counselling – Martin AdamsThis is a valuable introduction to existential counseling for students and those new to the field wishing to understand the key concepts.

Martin Adams explores how to use the therapeutic process to work effectively with clients, teaching them to live according to their values.

Find the book on Amazon.

3.

Existential Therapy: 100 Key Points and Techniques – Susan Iacovou and Karen Weixel-DixonThis is an insightful and accessible book for understanding the human challenges of existence.

The authors provide a comprehensive introduction and overview of ideas and techniques central to the philosophical theories underpinning existential therapy, along with practical approaches for use with clients.

Find the book on Amazon.

For further reading, we also recommend these 7 Best Books to Help You Find the Meaning of Life.

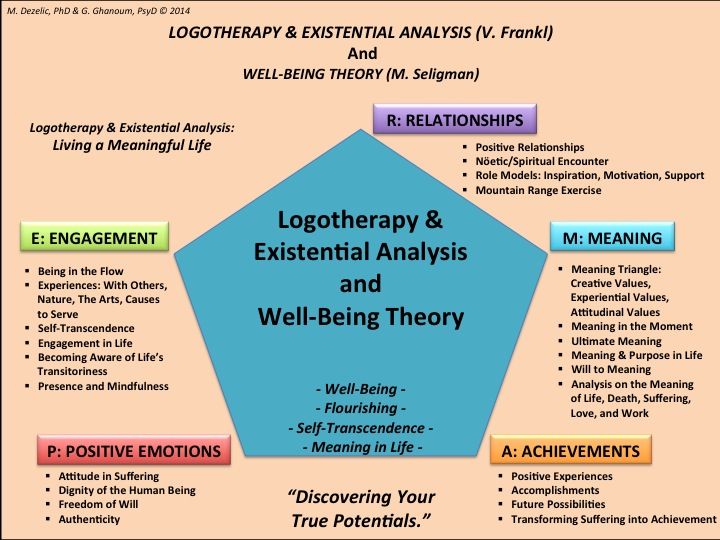

A Look at Our Meaning & Valued Living Masterclass

The Meaning and Valued Living Masterclass is an online program for therapists, psychologists, counselors, coaches, and practitioners who want to help their clients find meaning and discover their values, connecting them to their ‘why’ so that they can bear any ‘how.’

The course consists of three modules. The introduction provides an in-depth look at positive psychology; the meaning module provides clarity on the complex topic of ‘meaning’ and tools to increase meaning in life; and the third module addresses valued living to help clients discover what is important to them.

The masterclass has received sterling reviews from entrepreneurs, business owners, and coaches, and can also help you earn continuing education credits.

Resources From PositivePsychology.com

Existential therapists work with clients to explore some of the most meaningful questions in their lives, including living fully and with meaning.

Why not download our free Meditations on Meaning exercises pack and try out the following powerful tools?

- The Top 5 Values

This helpful exercise is a valuable tool for increasing clients’ awareness of their values. - Self-Eulogy

This is a valuable worksheet for helping clients discern how they live in line with their values.

Other free resources include:

- The PERMA Model

Understand and apply the PERMA model to your life by adopting a positive attitude and finding things that make you happy and engaged. - Self-Esteem Journal for Adults

Journaling can promote positive self-reflection and encourage and enhance self-esteem.

More extensive versions of the following tools are available with a subscription to the Positive Psychology Toolkit©, but they are described briefly below:

- The Life Certificate

Enduring the death of a loved one can be one of the most painful experiences in our lives. It can help to remember the many good things about the deceased by creating a life certificate, including:- Reflecting on favorite stories that characterize the person and what they meant to you

- Thinking of words that best describe them and how you appreciated them

- How they helped you be the person you are today

- The Values Timeline

Invite the client to reflect on their values and how they have changed over their lifetime while recognizing they remain in control of what they are:- Clarify your top five core values.

- Identify core values from earlier stages of your life.

- Recognize how these values have changed over your life.

- Examine how these values are serving you now.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others discover meaning, check out this collection of 17 validated meaning tools for practitioners. Use them to help others choose directions for their lives in alignment with what is truly important to them.

A Take-Home Message

Existential therapy is based on the idea that our problems arise from the essential paradoxes of human existence rather than personal pathology.

We choose our values and whether and how we live according to them.

Existential therapists recognize that many of us are practiced at deceiving ourselves regarding life’s realities; we fail to see how the way we behave, think, and feel may be contributing to our unhappiness and lack of fulfillment (Iacovou & Weixel-Dixon, 2015).

During therapy, the practitioner encourages the client to remain open to other ways of living and being that they are not currently choosing. As such, it can be demanding, asking clients to comprehend and accept their responsibility for the choices they make. Taking responsibility for our lives can be a great source of anxiety, directly or indirectly, and requires dedicated and professional support (Adams, 2013).

As such, it can be demanding, asking clients to comprehend and accept their responsibility for the choices they make. Taking responsibility for our lives can be a great source of anxiety, directly or indirectly, and requires dedicated and professional support (Adams, 2013).

This article introduces the theory and practices behind existential therapy and provides tools, worksheets, and questions to help clients in sessions or as homework.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free.

- Adams, M. (2013). A concise introduction to existential counselling. SAGE.

- Iacovou, S., & Weixel-Dixon, K. (2015). Existential therapy: 100 Key points and techniques. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- van Deurzen, E. (2002). Existential counselling & psychotherapy in practice (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- van Deurzen, E., & Adams, M. (2016). Skills in existential counselling & psychotherapy.

SAGE.

SAGE.

The Existential Approach | The NSPC

The existential approach is first and foremost philosophical. It is concerned with the understanding of people’s position in the world and with the clarification of what it means to be alive. It is also committed to exploring these questions with a receptive attitude, rather than a dogmatic one: the search for truth with an open mind and an attitude of wonder is the aim, not the fitting of the client into pre-established categories and interpretations.

The existential approach considers human nature to be open-ended, flexible and capable of an enormous range of experience. The person is in a constant process of becoming. I create myself as I exist. There is no essential, solid self, no given definition of one’s personality and abilities.

Existential thinkers avoid restrictive models that categorise or label people. Instead, they look for the universals that can be observed transculturally. There is no existential personality theory which divides humanity up into types or reduces people to part components. Instead, there is a description of the different levels of experience and existence that people are inevitably confronted with.

Extracts are taken from ‘Existential Therapy’ (chapter 8) by Emmy van Deurzen, in Dryden, W. ed. The Dryden Handbook of Individual Therapy, London, Sage Publications, 2008.

Existential Therapy

World Confederation for Existential Therapy

Preface

In 2014-2016, an international group representing a cross-section of contemporary existential therapists joined together in a cooperative effort to create this broad definition. It was written in the spirit of inclusiveness and diversity that characterizes this unique orientation, toward the goal of arriving at an accessible, succinct, "good enough" working definition of existential therapy. This definition recognises and honours the shared and unifying stance which underpins and informs the various different ways of understanding and practising existential therapy today, without doing violence to its inherent spontaneity, flexibility, creativity and mystery. What follows is the current version of an ongoing, continually evolving, collective quest.

- What is existential therapy?

Existential therapy is a philosophically informed approach to counselling or psychotherapy. It comprises a richly diverse spectrum of theories and practices. Due partly to its evolving diversity, existential therapy is not easily defined. For instance, some existential therapists do not consider this approach to be a distinct and separate “school” of counselling or psychotherapy, but rather an attitude, orientation or stance towards therapy in general. However, in recent years, existential therapy is increasingly considered by others to be a particular and specific approach unto itself. In either case, it can be said that though difficult to formalize and define, at its heart, existential therapy is a profoundly philosophical approach characterized in practice by an emphasis on relatedness, spontaneity, flexibility, and freedom from rigid doctrine or dogma.Indeed, due to these core qualities, to many existential therapists, the attempt to define it seems contradictory to its very nature.

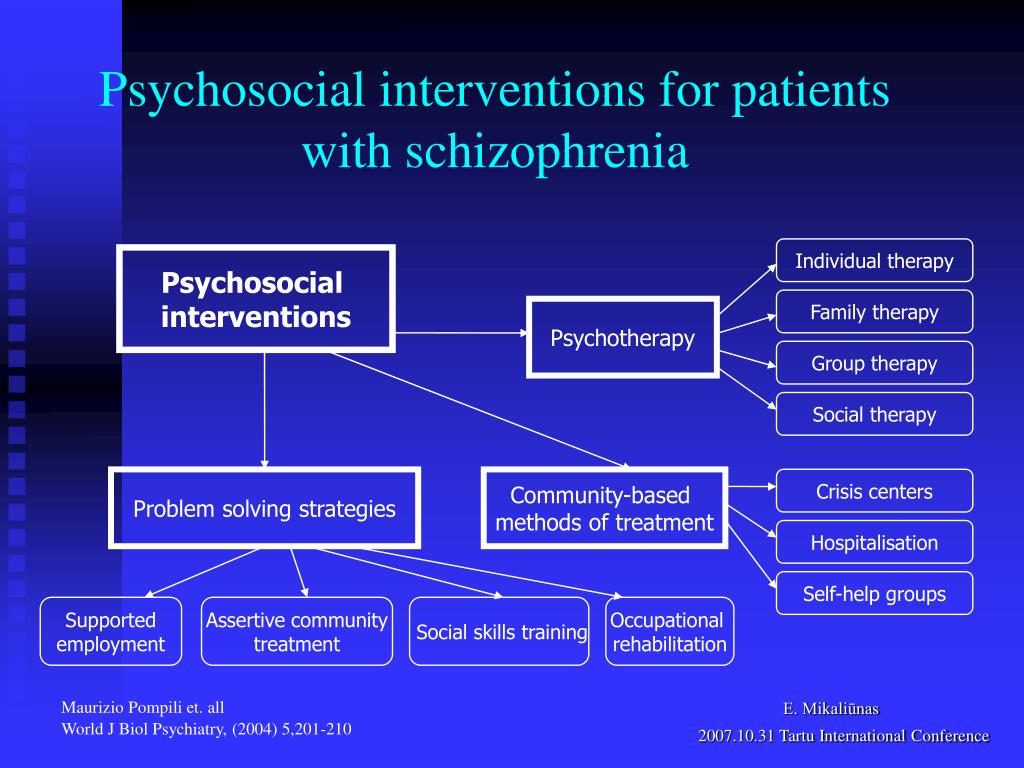

As with other therapeutic approaches, existential therapy primarily (but not exclusively) concerns itself with people who are suffering and in crisis. Some existential therapists intervene in ways intended to alleviate or mitigate such distress when possible and assist individuals to contend with life’s inevitable challenges in a more meaningful, fulfilling, authentic, and constructive manner. Other existential therapists are less symptom-centred or problem-oriented and engage their clients in a wide-ranging exploration of existence without presupposing any particular therapeutic goals or outcomes geared toward correcting cognitions and behaviours, mitigating symptoms or remedying deficiencies. Nevertheless, despite their significant theoretical, ideological and practical differences, existential therapists share a particular philosophically-derived worldview which distinguishes them from most other contemporary practitioners.

Existential therapy generally consists of a supportive and collaborative exploration of patients’ or clients' lives and experiences. It places primary importance on the nature and quality of the here-and-now therapeutic relationship, as well as on an exploration of the relationships between clients and their contextual lived worlds beyond the consulting room. In keeping with its strong philosophical foundation, existential therapy takes the human condition itself -- in all its myriad facets, from tragic to wondrous, horrific to beautiful, material to spiritual -- as its central focus. Furthermore, it considers all human experience as intrinsically inseparable from the ground of existence, or “being-in-the-world”, in which we each constantly and inescapably participate.

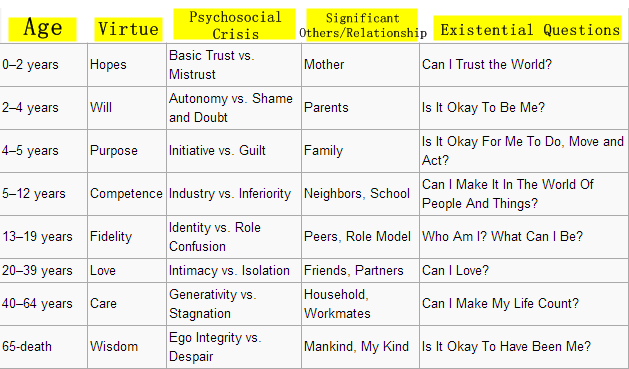

Existential therapy aims to illuminate the way in which each unique person -- within certain inevitable limits and constraining factors -- comes to choose, create and perpetuate his or her own way of being in the world.In both its theoretical orientation and practical approach, existential therapy emphasizes and honours the perpetually emerging, unfolding, and paradoxical nature of human experience, and brings an unquenchable curiosity to what it truly means to be human. Ultimately, it can be said that existential therapy confronts some of the most fundamental and perennial questions regarding human existence: "Who am I?" “What is my purpose in life?” “Am I free or determined?” “How do I deal with my own mortality?” "Does my existence have any meaning or significance?" "How shall I live my life?"

- Why is it called “existential” therapy?

Existential therapy is based on a broad range of insights, values, and principles derived from phenomenological and existential philosophies. These philosophies of existence stress certain “ultimate concerns” -- often in dialectical tension with each other -- such as freedom of choice, the quest for meaning or purpose, and the problems of evil, isolation, suffering, guilt, anxiety, despair, and death.For existential therapists, “phenomenology” refers to the disciplined philosophical method by which these ultimate concerns or "givens" are addressed, and through which the person’s basic experience of being-in-the-world can best be illuminated or revealed, and thus, more accurately understood. This phenomenological method begins by deliberately trying to set aside one’s presuppositions so as to be more fully open and receptive to the exploration of another person’s subjective reality.

Though there can be many different motivations for individuals choosing to engage in this explorative process, as with most forms of counselling, psychotherapy, or psychological and psychiatric treatment, existential therapy is commonly sought by people in the throes of an existential crisis: some specific circumstance in which we experience our basic sense of survival, security, identity or significance as being threatened. Such existential threats may be of a physical, social, emotional or spiritual nature, and may be directed toward one's self, others, the world in general or the ideas and perceptions we live by. They shock and shake us out of our sense of safety and complacency, forcing us to question and doubt our most deeply held beliefs or values. Because, according to existential therapists, human existence is, by its very nature, continually changing or becoming, we are naturally prone to experiencing such existential challenges or crises across the lifespan. In existential therapy, these disorienting and anxiety provoking periods of crisis are perceived as both a perilous passage and an opportunity for transformation and growth.

They shock and shake us out of our sense of safety and complacency, forcing us to question and doubt our most deeply held beliefs or values. Because, according to existential therapists, human existence is, by its very nature, continually changing or becoming, we are naturally prone to experiencing such existential challenges or crises across the lifespan. In existential therapy, these disorienting and anxiety provoking periods of crisis are perceived as both a perilous passage and an opportunity for transformation and growth. - How does existential therapy work?

Existential therapists see their practice as a mutual, collaborative, encouraging and explorative dialogue between two struggling human beings -- one of whom is seeking assistance from the other who is professionally trained to provide it. Existential therapy places special emphasis on cultivating a caring, honest, supportive, empathic yet challenging relationship between therapist and client, recognizing the vital role of this relationship in the therapeutic process.

In practice, existential therapy explores how clients’ here-and-now feelings, thoughts and dynamic interactions within this relationship and with others might illuminate their wider world of past experiences, current events, and future expectations. This respectful, compassionate, supportive yet nonetheless very real encounter -- coupled with a phenomenological stance -- permits existential therapists to more accurately comprehend and descriptively address the person's way of being in the world. Taking great pains to avoid imposing their own worldview and value system upon clients or patients, existential therapists may seek to disclose and point out certain inconsistencies, contradictions or incongruence in someone's chosen but habitual ways of being. By so doing, some existential therapists will when necessary, constructively confront a person's sometimes self-defeating or destructive ways of being in the world. Others will deliberately choose to avoid viewing or addressing any experience or expression of the person's being in the world from a perspective that construes it as being positive/negative, constructive/destructive, healthy/unhealthy, etc. In either case, the therapeutic aim is to illuminate, clarify, and place these problems into a broader perspective so as to promote clients' capacity to recognize, accept, and actively exercise their responsibility and freedom: to choose how to be or act differently, if such change is so desired; or, if not, to tolerate, affirm and embrace their chosen ways of being in the world.

In either case, the therapeutic aim is to illuminate, clarify, and place these problems into a broader perspective so as to promote clients' capacity to recognize, accept, and actively exercise their responsibility and freedom: to choose how to be or act differently, if such change is so desired; or, if not, to tolerate, affirm and embrace their chosen ways of being in the world.

To facilitate this potentially liberating process, existential therapy focuses primarily on enhancing the person's awareness of his or her “inner” experiencing, "subjectivity" or being: the temporal, transitory, vital flux of moment-to-moment thoughts, sensations and feelings. At the same time, existential therapy recognizes the inevitable interplay between past, present and future. In this regard, existential therapists respect the impressive power of the past and the future and directly address it as it impacts upon the present. - What makes existential therapy different from other therapies?

In addition to its unique combination of philosophical worldview, phenomenological stance, and core emphasis on both the therapeutic relationship and actual experience, existential therapy is generally less focused on diagnosing psychopathology and providing rapid symptom relief per se than other forms of therapy. Instead, distressing "symptoms" such as anxiety, depression or rage are recognized as potentially meaningful and comprehensible reactions to current circumstances and personal contextual history. As such, existential therapy is primarily concerned with experiencing and exploring these disturbing phenomena in depth: directly grappling with rather than trying to immediately suppress or eradicate them. Consistent with this, existential therapy tends to be more exploratory than specifically or behaviorally goal-oriented. Its principal aim is to clarify, comprehend, describe and explore rather than analyze, explain, treat or “cure” someone's subjective experience of suffering.

Instead, distressing "symptoms" such as anxiety, depression or rage are recognized as potentially meaningful and comprehensible reactions to current circumstances and personal contextual history. As such, existential therapy is primarily concerned with experiencing and exploring these disturbing phenomena in depth: directly grappling with rather than trying to immediately suppress or eradicate them. Consistent with this, existential therapy tends to be more exploratory than specifically or behaviorally goal-oriented. Its principal aim is to clarify, comprehend, describe and explore rather than analyze, explain, treat or “cure” someone's subjective experience of suffering. - What techniques or methods do existential therapists employ?

Existential therapy does not define itself predominantly on the basis of any particular predetermined technique(s). Indeed, some existential therapists eschew the use of any technical interventions altogether, concerned that such contrived methods may diminish the essential human quality, integrity, and honesty of the therapeutic relationship. However, the one therapeutic practice common to virtually all existential work is the phenomenological method. Here, the therapist endeavours to be as fully present, engaged, and free of expectations as possible during each and every therapeutic encounter by attempting to temporarily put aside all preconceptions regarding the process. The purpose is to gain a clearer contextual in-depth understanding and acceptance of what a certain experience might signify to this specific person at this particular time in his or her life.

However, the one therapeutic practice common to virtually all existential work is the phenomenological method. Here, the therapist endeavours to be as fully present, engaged, and free of expectations as possible during each and every therapeutic encounter by attempting to temporarily put aside all preconceptions regarding the process. The purpose is to gain a clearer contextual in-depth understanding and acceptance of what a certain experience might signify to this specific person at this particular time in his or her life.

Many existential therapists also make use of basic skills like empathic reflection, Socratic questioning, and active listening. Some may also draw on a wide range of techniques derived from other therapies such as psychoanalysis, cognitive-behavioural therapy, person-centred, somatic, and Gestalt therapy. This technical flexibility allows some existential practitioners the freedom to tailor the particular response or intervention to the specific needs of the individual client and the continually evolving therapeutic process. However, whatever methods might or might not be employed in existential therapy, they are typically intentionally chosen to help illuminate the person's being at this particular moment in his or her history.

However, whatever methods might or might not be employed in existential therapy, they are typically intentionally chosen to help illuminate the person's being at this particular moment in his or her history. - What are the goals of existential therapy?

The overall purpose of existential therapy is to allow clients to explore their lived experience honestly, openly and comprehensively. Through this spontaneous, collaborative process of discovery, clients are helped to gain a clearer sense of their experiences and the subjective meanings they may hold. This self-exploration provides individuals with the opportunity to confront and wrestle with profound philosophical, spiritual and existential questions of every kind, as well as with the more mundane challenges of daily living. Fully engaging in this supportive, explorative, challenging process can help clients come to terms with their own existence, and take responsibility for the ways they have chosen to live it. Consequently, it can also encourage them to choose ways of being in the present and future that they, themselves, identify as more deeply satisfying, meaningful and authentic.

Consequently, it can also encourage them to choose ways of being in the present and future that they, themselves, identify as more deeply satisfying, meaningful and authentic. - Who can potentially benefit from existential therapy?

An existential approach may be helpful to people contending with a broad range of problems, symptoms or challenges. It can be utilized with a wide variety of clients, ranging from children to senior citizens, couples, families or groups, and in virtually any setting, including clinics, hospitals, private practices, the workplace, organizations, and in the wider social community. Because existential therapy recognizes that we always exist in an interrelational context with the world, it can be especially useful for working with clients from diverse demographic and cultural backgrounds.

While existential therapy is particularly well-suited to people who are seeking to explore their own philosophical stance toward life, it may, in some cases, be a less appropriate choice for patients in need of rapid remediation of painful, life-threatening or debilitating psychiatric symptoms. However, precisely due to its fundamental focus on a person’s entire existence rather than solely on psychopathology and symptoms, existential therapy can nonetheless potentially be an effective approach in addressing even the most severe reactions to devastating psychological, spiritual or existential disruptions or upheavals in their lives, whether in combination with psychiatric medication when needed or on its own.

However, precisely due to its fundamental focus on a person’s entire existence rather than solely on psychopathology and symptoms, existential therapy can nonetheless potentially be an effective approach in addressing even the most severe reactions to devastating psychological, spiritual or existential disruptions or upheavals in their lives, whether in combination with psychiatric medication when needed or on its own. - What scientific evidence is there regarding the efficacy of existential therapy?

A range of well-controlled studies indicates that certain forms of existential therapy, for certain client groups, can lead to increased well-being and sense of meaning (Vos, Craig & Cooper, 2014). This body of evidence is growing, with new studies showing that existential therapies can produce as much improvement as other therapeutic approaches (e.g., Rayner & Vitali, in press). This finding is consistent with decades of scientific research which shows that, overall, all forms of psychotherapy are effective, and that, on average, most therapies are more or less equally helpful (Seligman, 1995; Wampold & Imel, 2015), with specific client characteristics and preferences determining the best therapeutic approach for any given individual. There is also a good deal of evidence indicating that one of the core qualities associated with existential therapy – a warm, valuing and empathic client or patient-therapist relationship — is predictive of positive therapeutic outcomes (Norcross & Lambert, 2011). Additionally, existential therapy's central emphasis on finding or making meaning has been shown in general to be a significant factor in effective treatment (Wampold & Imel, 2015).

There is also a good deal of evidence indicating that one of the core qualities associated with existential therapy – a warm, valuing and empathic client or patient-therapist relationship — is predictive of positive therapeutic outcomes (Norcross & Lambert, 2011). Additionally, existential therapy's central emphasis on finding or making meaning has been shown in general to be a significant factor in effective treatment (Wampold & Imel, 2015). - Where can I find out more about existential therapy and/or professional training to become an existential therapist?

Until recently, there were few if any formal training programs for existential therapists. In recent years, this situation has changed, with the creation of various training programs in the United States, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Portugal, Russia, Canada, Scandinavia, Israel, Argentina, Mexico, Chile, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Lithuania, Greece, Australia and many other countries.

A full list of training courses is available on the website.

More about the existential approach

An extract from the constitution of the Federation of Existential Therapists in Europe (FETE) to be found at http://existentialfete.online/:

"The existential worldview:

Existential Therapy values the interactive, relational and embodied nature of human consciousness and human existence. It considers that human beings are free to effect change in their lives in a responsible, deliberate, ethical and thoughtful manner, by understanding their difficulties and by coming to terms with the possibilities and limitations of the human condition in general and of their own lives in particular. It emphasises the importance of finding meaning and purpose by engaging with life at many levels, physical, social, personal and spiritual. It does not prescribe a particular worldview but examines the tensions and contradictions in a person’s way of being. This will include a consideration of existential limits such as death, failure, weakness, guilt, anxiety and despair. "

This will include a consideration of existential limits such as death, failure, weakness, guilt, anxiety and despair. "

How does existential therapy work?

There are many forms of Existential Therapy and each has its own specific methods and ways of exploring difficulties and change, but all forms of existential therapy work with dialogue to enable a person to find their own authority in exploring their life and the way they want to live it. This will often involve a philosophical and ethical exploration of the big questions of human existence, such as truth, meaning, justice, beauty, freedom, consciousness, choice, responsibility, friendship and love.

Existential Therapy is a pragmatic and experiential approach which favours embodiment, emotional depth, clarity and directness and which employs the principles of logic, paradox, dialectics, phenomenology and hermeneutic exploration amongst other methods.

What does it aim for?

Existential therapists aim to approach a person’s un-ease or suffering in a phenomenological, holistic way. Symptoms are not seen as the defining aspect of a person’s troubles, but rather as an expression of the person’s disconnection from reality, or distorted reality.

Symptoms are not seen as the defining aspect of a person’s troubles, but rather as an expression of the person’s disconnection from reality, or distorted reality.

Therefore Existential therapists see symptoms as a way of coping with difficulty, a problem, or an existential crisis. A person’s experience will be considered at all levels.

Equal attention will be paid to a person’s past, present and future. Existential therapists facilitate a person’s greater awareness of their mode of being in the world, helping them to be more in touch with their concrete physicality, their interactions and relationships, their engagement with their own identity or lack of it, their concept of what grounds their being and the ways in which they may be able to bring the flow and their capacity for transcendence, learning and pleasurable forward movement back to life. It helps people to tolerate and embrace suffering and difficulty to engage with it constructively.

How do we train people?

Existential therapists are trained in specialist training programs, that require training at post-graduate level and which involve theoretical learning, skills training, practical learning under supervision, a process of personal therapy to learn to apply existential principles in practice and the completion of some form of phenomenological research project or a final project that includes theory and practice. ”

”

- Norcross, J. C., & Lambert, M. J. (2011). Evidence-based therapy relationships. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (2nd ed., pp. 3-21). New York: Oxford University.

- Rayner, M., & Vitali, D. (in press). Short-term existential psychotherapy in primary care: A quantitative report. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. [Spanish translation published as Rayner, M. y Vitali, D. (2015). Psicoterapia existencial de corto plazo en atención primaria: Un reporte cuantitativo. Revista electrónica Latinoamericana de Psicologia Existencial "Un enfoque comprensivo del ser". N° 11. Octubre.]

- Vos, J., Craig, M., & Cooper, M. (2014). Existential therapies: A meta-analysis of their effects on psychological outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(1), 115-128. doi: 10.1037/a0037167

- Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2015). The Great Psychotherapy Debate: The Evidence for What Makes Psychotherapy Work (2nd ed.

). New York: Routledge.

). New York: Routledge.

What is existential psychotherapy? – Blog – Yasno

Death, loneliness, meaning and responsibility — existential psychotherapy does not agree to a smaller scope. This direction is a good example of how philosophy has found practical application in psychotherapy. We deal with key concepts and try to understand why existential therapists love depression.

Existential psychotherapy grew out of existential philosophy and phenomenology. That is why in the title illustration we have outstanding existentialists - Kierkegaard, Heidegger, Sartre - and those who embodied their ideas in psychotherapy - Viktor Frankl, Irvin Yalom (we will talk about the rest below). Concept "existence" (from Latin existentia - existence) was introduced in the 19th century by Soren Kierkegaard. Existence is a way of being of the human person. It is not equal to everyday existence, it is not set in advance - on the contrary, it is an open opportunity to become a person. The goal of existential psychotherapy is to help a person fulfill himself.

The goal of existential psychotherapy is to help a person fulfill himself.

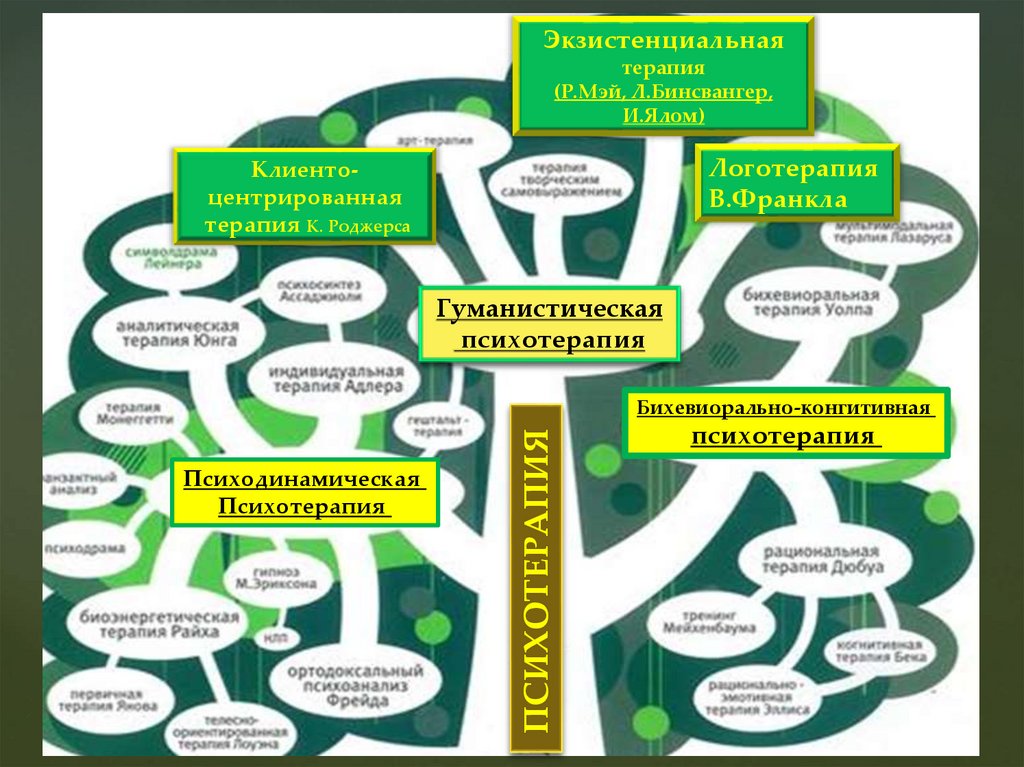

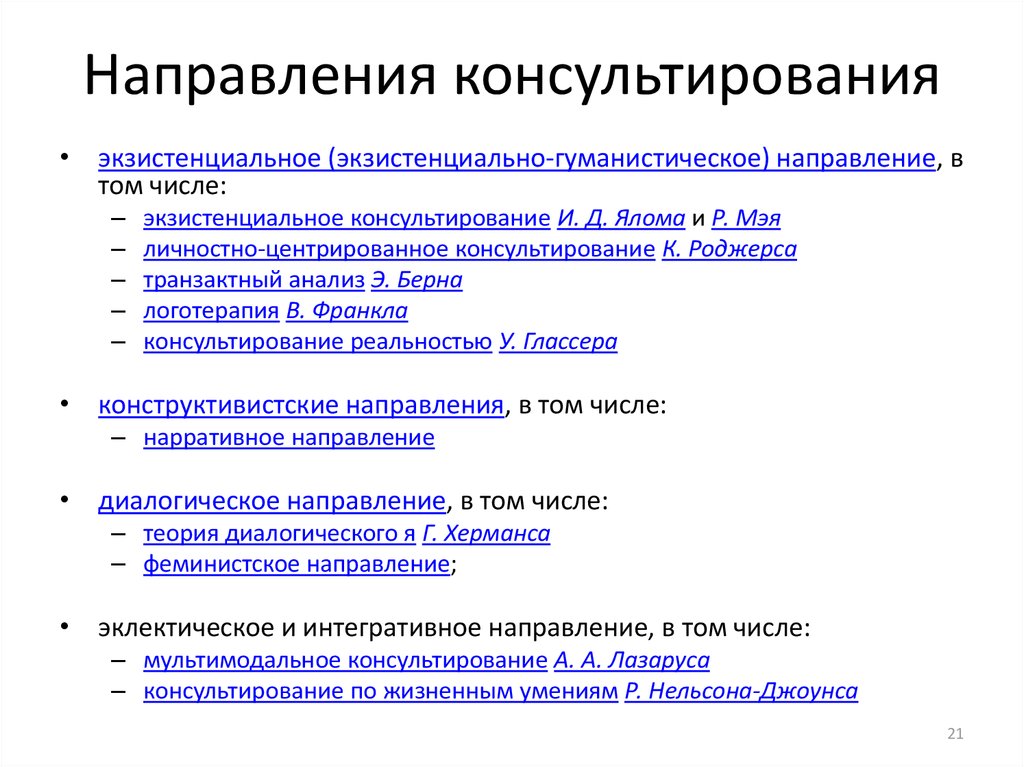

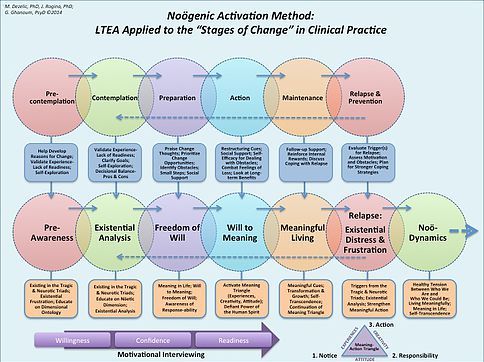

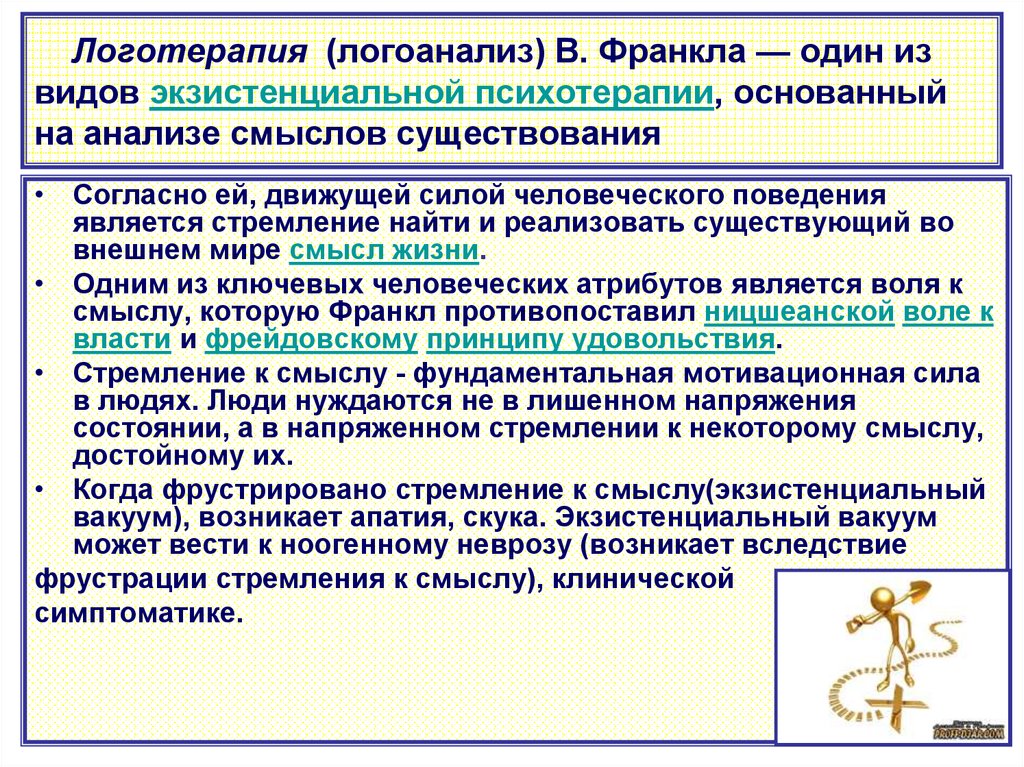

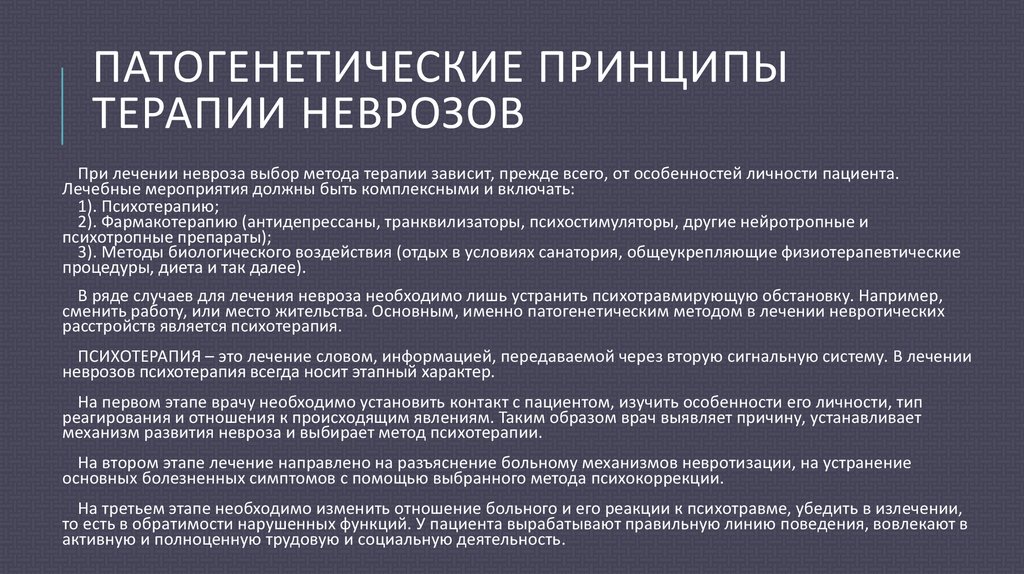

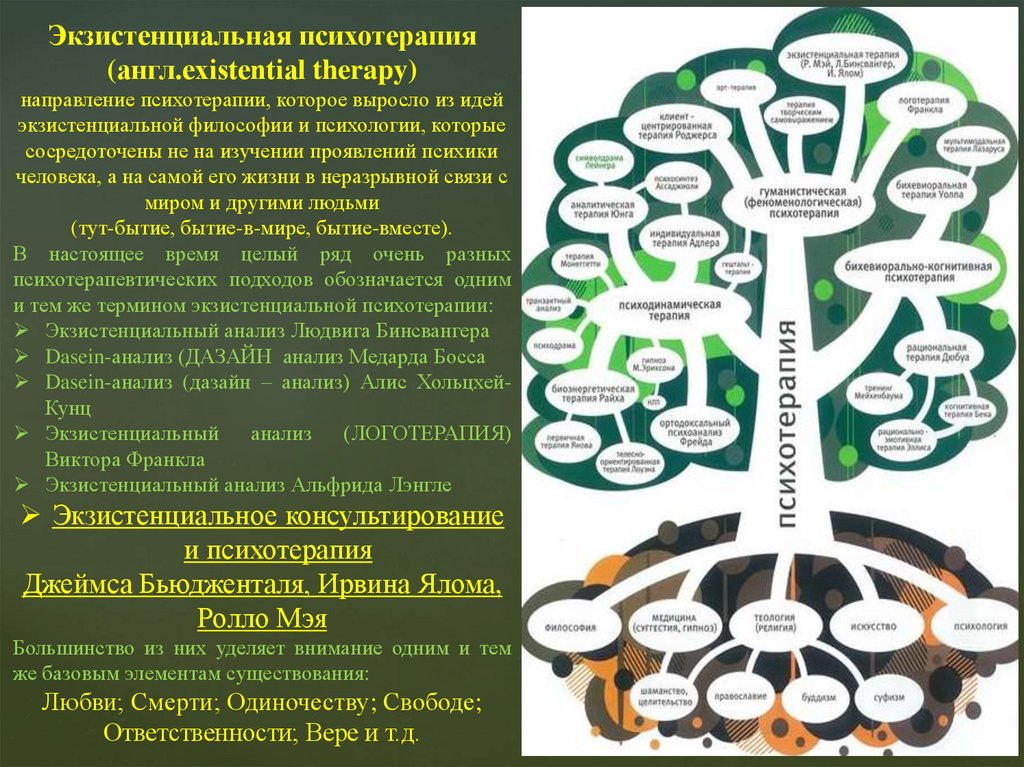

Existential psychotherapy has many branches: Viktor Frankl's logotherapy, Carlfried Durkheim's existential-initial therapy, Dasein-analysis based on the works of Heidegger; Yalom, Lenglet, May, and Bugental are doing existential counseling. It’s easy to get confused, but they are actually based on five key concepts: meaning/meaninglessness, fear of death, free will, responsibility, isolation . From phenomenologists, psychotherapists took a method: the client is examined not as a ready-made construct with a set of scenarios, traumas and defenses, but as a person in continuous development. The therapist each time as if gets acquainted with the client anew.

Key concepts

The ideal client of an existential psychotherapist sooner or later comes to the following conclusions:

- I am mortal, therefore my existence cannot be postponed. nine0022

- I'm not afraid of loneliness.

- I am free to choose and I am responsible for my choice.

- I seek meaning in everything.

DEATH

In existential psychotherapy, death works as a boundary situation and can change one's outlook on life, but at the same time serves as a source of anxiety. Irvin Yalom, in his book Existential Psychotherapy, writes about this paradox as follows: “Physically, death destroys a person, but the idea of death can save him.” Therefore, the work of the therapist is aimed at ensuring that the client confronts his own death, can bear the thought of it, and being aware of it, feels the fullness of life. nine0005

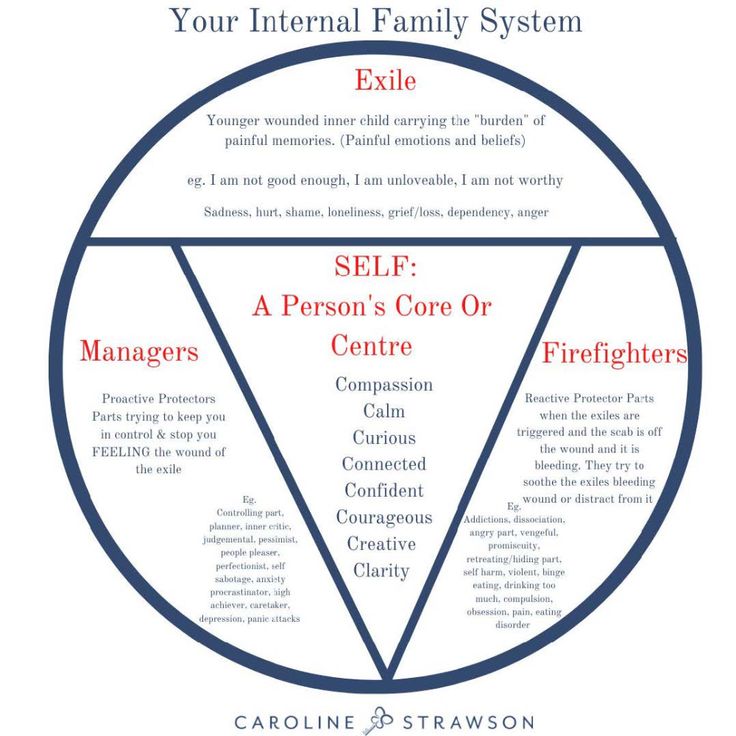

FREE WILL AND RESPONSIBILITY

The main premise of existential psychotherapy is this: we are fully responsible for our lives, not only for our actions, but also for our inability to act. Therefore, therapeutic interventions are designed to ensure that the client takes full responsibility for his own failures. Why invest energy in personal change when the client is convinced that genes, chance, bad luck, or a rejecting mother are the cause of all troubles? nine0005

Why invest energy in personal change when the client is convinced that genes, chance, bad luck, or a rejecting mother are the cause of all troubles? nine0005

People avoid taking responsibility in the most sophisticated ways. Being compulsive, a person seems to admit that he is obsessed with some idea or is under the control of an irresistible force. He is far from what he really wants, his life consists only of compulsions. You can avoid responsibility by making yourself a victim of circumstances. Insensitivity to one's own desires, the inability to make a decision - can also be examples of avoidance of responsibility.

To show the client his own ways of avoiding responsibility, therapists often work provocatively. For example, they suggest replacing the construction “I can’t” with “I would not want to.” For clients who blame their parents for all their troubles, the therapist may suggest having a dialogue with them and saying several times: “I will not change until the way you treated me when I was little changes. ” nine0005

” nine0005

But awareness alone is not enough, and any therapist tries to influence the will of the client and achieve action.

ISOLATION

A person can be isolated from the world and other people, can be isolated from some part of himself, but existential isolation is a broader concept and is directly related to responsibility. When a person realizes responsibility for his choice, he understands that no one will make this choice for him - there is no one who protects and guides him. This is existential loneliness. nine0005

The opposite of isolation is fusion. Reluctance to leave the parental home, fear of letting the child go, co-dependent relationships, parasitism on others are examples of avoiding isolation. The task of the psychotherapist is to help the client enter into relationships not out of fear of loneliness, to help him see how he can use people, escaping from this fear.

It is interesting that the very word "existence" contains the idea of separation: ex- (from, from), sistere - to put, place. The process of growth is impossible without separation: autonomy, self-reliance, self-control, independence. nine0005

The process of growth is impossible without separation: autonomy, self-reliance, self-control, independence. nine0005

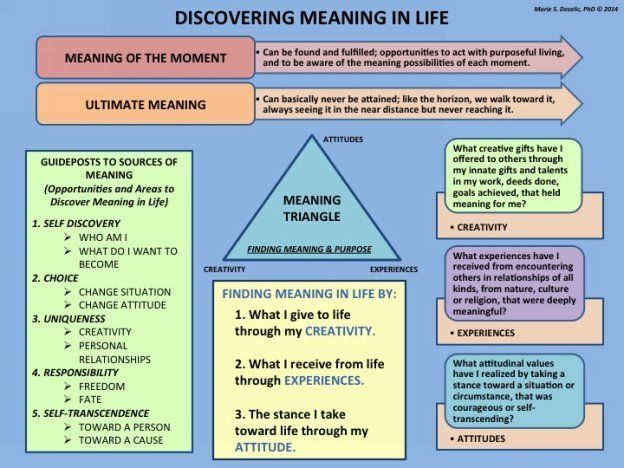

MEANING

“Man does not seek pleasure, he seeks meaning, and pleasure is a by-product of meaning,” wrote Viktor Frankl. He singled out three ways to make your life meaningful: creativity, experience and attitude towards suffering. But how can you find meaning in suffering? The answer to this question becomes clear when you remember the biography of Frankl himself. He was one of the survivors of Nazi concentration camps and tried to understand how prisoners in a hopeless and tragic situation managed to find a meaning to live on. The only thing left for them was to take a heroic stance towards their destiny. nine0005

For Irvin Yalom, the antidote to meaninglessness is engagement. He believes that the desire to become involved is always within the client, and the therapist's task in this case is to look for what prevents this involvement: what prevents the client from entering into close relationships? what prevents him from finding a really interesting job? why does he not allow himself any creative manifestations?

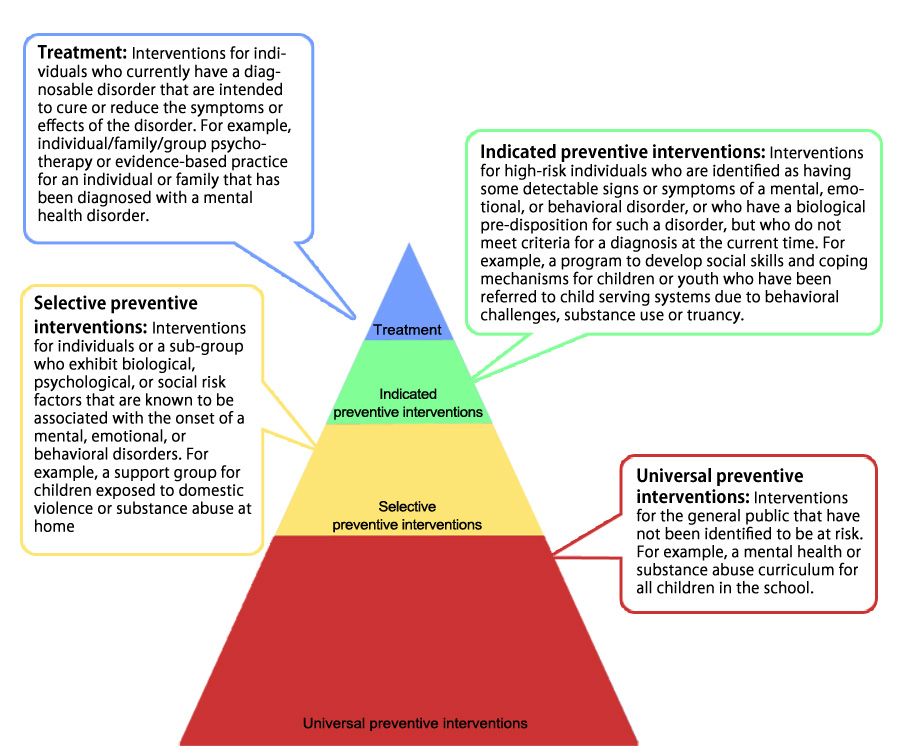

When is existential therapy needed?

Existential psychotherapy is good for those who are on the verge of life changes or are experiencing a “dark night of the soul”. Existential psychotherapists focus on a person's ability to overcome suffering. nine0005

Existential psychotherapists focus on a person's ability to overcome suffering. nine0005

For example, existential therapists do not consider depression and anxiety to be a symptom of a mental illness that needs to be treated. Rather, they see them as necessary experiences for becoming a person. Depression indicates a crisis of old values and may open the way for new ones. Anxiety indicates that a person is awakening to life and must make an important life choice. Where a person feels resentful, frustrated and broken, he can become truly awakened. nine0005

Existential therapy helps a person to see how his worldview changes and colors the world, how his feelings are connected with values and meanings. The goal of therapy is to lead a person to comprehend his own emotions, actions and values, to teach him to choose his own path in life and to be responsible for any choice.

Reflection and action in existential psychotherapy (Con G.)

Con (UK)

|

What is existential practice?

One day my psychoanalyst friend asked me: “What are you are you doing ?” He was familiar with existential texts, but did not know how these philosophical ideas could be useful in meetings with problem-laden people in the counseling room. And for many students, this is precisely the difficulty - not in the complexity of the texts of Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty, but in what is the connection between these ideas and daily therapeutic reality. nine0005

nine0005

There are obviously a number of difficulties for existential therapists. Of course, there are a number of specific requirements, which they follow in their work with clients. Meanwhile, however, in psychoanalytic practice there are many references to psychoanalytic theory. But in existential therapy such links are much less.

Could it be that a direct connection between the existential thought and existential practice was simply absent or that it be so ghostly that even words cannot will you pass? Could it be that one existential session differs so significantly from the other that the desired common for of all sessions, the base we are trying to describe is simply missing like a fact?

By the way, Medard Boss, a friend of Heidegger and one of the first existential therapists, believed that all Freud's theories demanded adjustments, but did not propose any amendments to Freudian practice. He believed that Freud's practice miraculously expresses existential thought, and not psychoanalytic, and on this basis denied the connection between Freud's theory and his own practice. nine0005

nine0005

It is existential therapists who are convinced that existential therapy is characterized mainly by its freedom from "techniques". In my opinion, they pay attention to what she is not , not that she is herself represents .

Practice and technique

On this occasion, I would like to put forward the following assumption: we distinguish between practice and technology. If theory is essentially "the way we think" (literally: how we look at things), then practice - is "what we are do or don't do with the way we think." In other words, practice is always there: it consists in the implementation or in not-doing what we think.

About technicality, I would say so. It occurs when our action loses touch with how we think. Loss of communication may occur in if we allow our action to become mechanical, automatic, lost flexibility. Or even when the action becomes simply comfortable and habitual, although at the same time we we realize that it is not related to how we think. nine0005

nine0005

Thus, if we think and feel existential-phenomenological - I say "we think and feel" as if thoughts and feelings are always together - we can choose, follow us this in our practice or else not do this. We can decide to continue working psychodynamically, if for some reason it is important to us, and by doing so, turn the practice towards technology.

What is existential phenomenology?

In order to get to the solution of this problem, I will first say a few words about how I understand existential phenomenology. This is necessary because there is a definite more than one way to describe it. There is no room for comparisons here. various ways of explaining the existential-phenomenological thoughts, but anyone who wants to discuss his existential experience, will first have to say what he means when says "existential" and "phenomenological". The assumption that everyone understands these terms in the same way is invariably leads to misunderstanding and confusion. nine0005

nine0005

My own practice is based on how I presented existential phenomenology in his early works Heidegger, in particular, in "Being and Time", and what he, as I think, later came back at the end of his life when he was lecturing students and psychiatrists in Switzerland. Phenomenology of Heidegger, inspired by the reading of Husserl, differs quite significantly from it. In a general sense, phenomenology, in the words of Dermot Moran, is best understood as a radical, anti-traditional style. philosophy, which focuses on trying to ... describe phenomena, in a broad sense - how something becomes what it is becomes, as it manifests itself for consciousness, for worried [2, 4].

It was important for Husserl to study the essence of this experience. Such is possible only if we suspend what he called "natural / natural attitude", the way in which we daily we interact with life itself, our practical involvement. It distorts "the true understanding of experience in that the form in which it is given to us” [2, 11].

For Heidegger this is unacceptable. Phenomenology is important to him. existence, and existence is understood by him as "Being-in-the-world" and includes the phenomena of artificiality and temporality. Again Let us turn to Morgan: “Heidegger wanted to apply phenomenology as the best way to get to the phenomena of a particular human life” [2, 228]. Heidegger, meanwhile, leaves nothing behind brackets - existence stands out (as the word implies) in a multifaceted situation where everything matters. And because the context always wider than we think, nothing can be once and for all thoroughly understood. nine0005

I will now move on to some particular aspects of existential phenomenology and try to convey what it gives to my practice.

being-in-the-world

What does it mean to understand existence as "being-in-the-world"? It means, that as human beings we are always included in a wider a context that we did not choose, but to which we are free to respond anyway. Being part of the context, we are also its co-creators.

Being part of the context, we are also its co-creators.

It is within this context that what we experience happens. like bans or failures. Change of context due to change our answer - that's what can help with the decision that we called "psychological problems". nine0005

And then the place of therapy is no longer in a hypothetically structured "psyche" inside a person, and the actions of the therapist are no longer connected with in order to weaken or strengthen the hypothetical components of this "psyche". The place of therapy is rather in a broader context, according to relation to which a person is both a part of it and co-creator, and the task of therapy is already to explore the answers specific personality that she gives to this context, leading to question: to what extent is a change in responses desirable and Maybe? nine0005

Here we see the relevance of different kinds of thinking to different types of practice. If we think that the existences of our clients can only be understood in the context of their lives, our practice is not will concentrate on their "intrapsychic" processes. Also us complete constructions and assumptions are not needed, which give meaning to these processes. Then the therapeutic practice will move from the individual "psyche" to the world and what can be perceived in it. And what can be perceived and there are phenomena of our relations to the world. These phenomena are not explanations - the latter remain speculation, from time to time changing from case to case. For an existential therapist phenomena are prioritized. nine0005

Also us complete constructions and assumptions are not needed, which give meaning to these processes. Then the therapeutic practice will move from the individual "psyche" to the world and what can be perceived in it. And what can be perceived and there are phenomena of our relations to the world. These phenomena are not explanations - the latter remain speculation, from time to time changing from case to case. For an existential therapist phenomena are prioritized. nine0005

Phenomena prioritization

What is good about the priority of phenomena for therapeutic situations? Let us give a simple example (and any example of this kind there is a simplification). A woman is crying in a session. Her tears are phenomenal. Therapists can, of course, come up with their own ideas for about her tears. But these ideas will be just guesses. A woman might say, “My mother used to cry a lot. Interesting, not Is that why I cry so much? This is her guess, but for therapist, this is part of her experience with tears that must certainly be taken into account. Why existential what the therapist must avoid is "collusion" with the client to turn his guesses into explanations. nine0005

Why existential what the therapist must avoid is "collusion" with the client to turn his guesses into explanations. nine0005

Assumptions may or may not be right, but they are always significant. However, they are significant only in the context, and - not in the context of a therapist. We see a difference between the two interpretation: a reducing interpretation that narrows the meaning phenomenon to “it means this…”, and hermeneutic, which expands the foundations of understanding by expanding the context, in within which the phenomenon has meaning. hermeneutical interpretation cannot be final. nine0005

The meaning of the client's tears will emerge from the broadest context of her life story created in the therapeutic space. There a connection can be found between her mother's tears and her own crying, but it is impossible to assign once and for all a certain the meaning of her tears.

Multidimensionality of time

Reasoning about the context of the "history of life" leads us to the question of applicability of existential-phenomenological understanding time in existential practice. nine0005

nine0005

Husserl in The Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Inner Time changed a sequence of different "nows" covering all directions of the three-dimensional version of the interpretation. Robert Dostal sums it up like this: "The past in the present remains in the past, and the future in the present is assumed to be future. Husserl says that these three dimensions form present” [1, 147].

Heidegger bases his theory on Husserl's constructions, but goes further. He sees time as part of existence, time becomes existential. Our past is part of our present as something that once happened to us, in our "artificiality" and our "absence". Our future is part our present as our potentiality, possibility. Absence and opportunity together make our history. nine0005

It is a well-known claim that the existential therapist concentrates only on what is called "here-and-now" and does not take into account the past and the future. However, perhaps it would be correct to say that in our concern for the present we inseparably preoccupied with both the past and the future, which are parts of present. And we must turn to it whenever it does not discovered.

And we must turn to it whenever it does not discovered.

Of course, we do not consider the "past" as the "cause" of the present in in the sense in which we understand that0080 now billiard room the ball rolls because before we pushed it. Context again occupies a linear position: the past is part of the context, which is our life. However, we do not believe that the past defeats lurk somewhere in the "psychic position", so that, having arisen at a certain moment, lead to the current trouble.

On the other hand, the future in the form of opportunities that are equally degree of probability can be both realized and missed, also is part of our present. If things were different, how can we even talk about change? nine0005

If our clients allow themselves (and we allow them) to have attitude to the history of one's life, part of the past is inevitable will show up, and they will be able to make new connections and more carefully explore the possibilities. It seems to me that the assumption rigid linear connections as something that connects the subtlest multi-mesh context network does not stand up to scrutiny. We need remember that we are talking about the context of the client, and, as already it was noted that this work is most successfully obtained by the clients, but not without delicate "visits" of the therapist. nine0005

It seems to me that the assumption rigid linear connections as something that connects the subtlest multi-mesh context network does not stand up to scrutiny. We need remember that we are talking about the context of the client, and, as already it was noted that this work is most successfully obtained by the clients, but not without delicate "visits" of the therapist. nine0005

Freedom and choice

Speaking of new opportunities, we come to the problem of choice. It would seem that psychotherapy has little to say about this, especially if it belongs to the deterministic direction. At that same time, the very term "change", as it seems to me, is included in her composition. When our clients come to us, they often feel trapped and have no hope get rid of it.

Existential thinking distinguishes between what is "given" and our responses to this. Thus becomes apparent the point where it becomes possible choice of new possibilities. The "given" may be out our control, this Heidegger called "absence". However, our the answers are not predicted in advance. Although it may be so. We are not we can change what our people have done or failed to do parents, but we can change our feelings about this. We can change our attempts to avoid pain and try learn to distinguish the pain that is inevitable from the one from which you can get rid of. Moreover, we can feel incapable of making such changes and admitting their powerlessness make a new choice. nine0005

However, our the answers are not predicted in advance. Although it may be so. We are not we can change what our people have done or failed to do parents, but we can change our feelings about this. We can change our attempts to avoid pain and try learn to distinguish the pain that is inevitable from the one from which you can get rid of. Moreover, we can feel incapable of making such changes and admitting their powerlessness make a new choice. nine0005

Two kinds of "given"

Some existential "givens" are different for each of us - as those social circumstances that we did not choose: our family, our language and our society with its laws and customs. Heidegger calls them ontic.

But there are still such "givens" that are shared by all of us, such as parts of our existence, the conditions of Being. Heidegger called them "ontological". These include our "leaving", "absence", our immutable "being-with-others", our embodiment and our temporality. Some existential therapists (to whom I I reckon myself) are sure that the denial of such “givens” can lead us into conflicts that will become part of our way being. nine0005

Some existential therapists (to whom I I reckon myself) are sure that the denial of such “givens” can lead us into conflicts that will become part of our way being. nine0005

Thus protective rituals of possession may be the answer. “no” to that insecurity that is part of existence. Difficulties in relationships of any kind can be the answer "no" the very nature of human Being, which is so characteristic communication.

Existential therapist, depending on how phenomenological his approach, will pay attention, before of everything, on the ontic part of the customer experience. Heidegger himself argued that the phenomena that manifest themselves in therapy "should not be subordinated to the all-embracing existential" [4, 162]. But therapist, depending on how existentially he works, will distinguish inclusions of the ontological in the ontic difficulties, and will be open to it when it manifests itself in client conversation. nine0005

Another

And in conclusion, let us turn to the question of our relationship with the Other, to a problem that has not been sufficiently addressed by critics existentialism and therapists. True, Heidegger wrote little about this, but he emphasizes the relational nature of existence, characterizing "Being-with" as an integral part of the human Genesis. If the existence of the Other is part of our very existence, then the nature of our relationship to the Other is obvious subject to criticism. The denial of the existence of the Other is the denial existence itself. This may be the starting point for belated existential study of violence. Heideggerian the concept of "Being-with" can, I believe (joining in this to others), to be basic for existential ethics. nine0005

True, Heidegger wrote little about this, but he emphasizes the relational nature of existence, characterizing "Being-with" as an integral part of the human Genesis. If the existence of the Other is part of our very existence, then the nature of our relationship to the Other is obvious subject to criticism. The denial of the existence of the Other is the denial existence itself. This may be the starting point for belated existential study of violence. Heideggerian the concept of "Being-with" can, I believe (joining in this to others), to be basic for existential ethics. nine0005

A particular aspect of our relationship with the Other, considered Heidegger and often mentioned - the distinction between "concern" (I would call it "anxiety"), which "takes a jump in", and the one that "jumps forward". This is the difference between an intervention that removes the burden of the Other, and an intervention that becomes a help to the Other on the way implementation of new opportunities [3, 158-159].

In conclusion, let's take a closer look at a specific an example of the relationship between client and therapist within existential therapy. We have established that the task of the therapist is not to help restore balance unstable "psyche" within the client. Rather, it should help research and expansion of the context to which arose and customer difficulties continue to arise. The goal is to create therapeutic space in which the client can make new connections and discover new opportunities. These connections and opportunities, as we have seen, belong to the client, and the therapist has no power over them and cannot be an expert in them. interpretation. nine0005

Perhaps one of the earliest meanings of the word "therapy" most accurately describes the task of the therapist - to provide assistance, be at your service.

Literature

-

Dostal R.J. (1993). Time at phenomenology in Husserl and Heidegger, in C.

B. Guignon (ed.), The Cambrigde Companion to Heidegger. Cambridge: C.U.P.

B. Guignon (ed.), The Cambrigde Companion to Heidegger. Cambridge: C.U.P. -

Moran D. (2000). Introduction to Phenomenology. London: Routledge. nine0005

-

Heidegger M. (1987). Zollikoner Seminar. Protocolle - Gespräche - Breife. Hrg. von M. Boss. Frankfurt a. M.: Klostermann.

-

Heidegger M. (1962). Being And Time. Tr. J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson. Oxford: Blackwell.

E. van Dorzen (UK)

| nine0089 |

| Emmy van Dorzen - Professor, Director of New School of Psychotherapy and Counseling (St. Sheffield, practicing existential psychotherapist. Translated by M. Kulakova, 2004. |

Only when a person is dead does it become clear what he meant to you. When Hans died, I was more shocked than I could imagine. imagine - as if a beloved uncle or a good friend had died. Although, to tell you the truth, I've never been particularly close to him, and I didn't feel like I knew him very well. I guess both of us deliberately tried to get out of the way of the other, at least because they were surprisingly tightly connected by the same interest to the use of Heidegger's ideas in psychotherapy. He was in hospital when I last called him and offered me meet to discuss in detail some purely technical moments. Together we lamented how few people understand Heidegger is deep enough to work in this area, and he expressed his gratitude that there were times when we discussed these things together. I felt that he appreciated me and I enjoyed talking with him. I wasn't sure I gave him what he asked for: close intellectual cooperation. We were both frustrated at how they blurred and perverted Heidegger's thoughts instead of studying his work in detail the way they deserve it.

When Hans died, I was more shocked than I could imagine. imagine - as if a beloved uncle or a good friend had died. Although, to tell you the truth, I've never been particularly close to him, and I didn't feel like I knew him very well. I guess both of us deliberately tried to get out of the way of the other, at least because they were surprisingly tightly connected by the same interest to the use of Heidegger's ideas in psychotherapy. He was in hospital when I last called him and offered me meet to discuss in detail some purely technical moments. Together we lamented how few people understand Heidegger is deep enough to work in this area, and he expressed his gratitude that there were times when we discussed these things together. I felt that he appreciated me and I enjoyed talking with him. I wasn't sure I gave him what he asked for: close intellectual cooperation. We were both frustrated at how they blurred and perverted Heidegger's thoughts instead of studying his work in detail the way they deserve it. With subtext, I asked are we not also talking about him. Hans was melancholy because of that he could no longer continue his research Heidegger's contribution to psychotherapy. This conversation took place just a few weeks before his death, but he still has there was a clear, strict understanding of the essence and an obvious thirst intelligent search. He was not interested in discussing his life, and even less - possible death. nine0005

With subtext, I asked are we not also talking about him. Hans was melancholy because of that he could no longer continue his research Heidegger's contribution to psychotherapy. This conversation took place just a few weeks before his death, but he still has there was a clear, strict understanding of the essence and an obvious thirst intelligent search. He was not interested in discussing his life, and even less - possible death. nine0005

In a sense, it was right to leave everything as it is. Hans and me said everything that needed to be said to each other. Last year, feeling that his end was drawing near, I wrote him a lengthy a letter in order to defuse the situation and, by the way, give back connection about his second book. We met during lunch at small old-fashioned restaurant near Waterloo and spent the most private discussion we've ever had were. He complained about the absence of such a restaurant and ate and talked so animatedly that I thought He still has a good ten years of life ahead of him. Then he came to new school to lecture about their new book and demonstrated genuine advocacy talent, defending Heideggerianism from outside attacks. Look at him was nice. nine0005

Then he came to new school to lecture about their new book and demonstrated genuine advocacy talent, defending Heideggerianism from outside attacks. Look at him was nice. nine0005

I first met Hans when he came to the first meeting of the Society for Existential Analysis in December 1988. Windy Dryden told him that I was going to open this new Society, and Hans came there in the hope of asking me a tricky question, suspecting that I don't know too much about the method. At In this, unlike many, he was extremely polite, and we continued our conversation over lunch, during which it became clear that he does not have his own base for the presentation of ideas. I immediately invited him to teach us at Regent College, and he willingly accepted the invitation. Started a professional friendship lasting sixteen years. We respected each other and often agreed to disagree on some specific points. But we never been close friends. I guess it's something awkward our relationship consisted in the contradiction between the fact that he was older, and the role I played in his professional activities. Things got complicated when I had to leave College, and he decided to stay there. We were kind to to each other in society, but something unsaid remained between us for many years. Hans continued teaching at College for another year, sharing teaching with Digby Tantam group therapy. She and Digby had known each other for a long time, since working at the Institute for Group Analysis. And it is Hans first attempted to convert Digby to existentialism at 1984 by inviting him to a lecture he gave at the institute, citing that it is much more existential than analytic, those. to the fact that Digby in those days (long before we met) stubbornly rejected. Of course, Hans was right, and he such rejection was unpleasant, but when we married Digby, Hans felt that balance was being restored.