Deflecting definition psychology

What is Deflecting?

Deflection happens when we redirect the focus, blame, or criticism away from ourselves in an attempt to preserve our self-image and avoid dealing with negative consequences.

It can be used as a reactive coping mechanism to avoid feelings of guilt and shame, or as a narcissistic abuse tactic to avoid accountability.

Whether we realize it or not, deflecting our mistakes onto others can create a negative impact on the thoughts, feelings, and emotions of the people we love.

We’re gonna dive into the what, why, and how of deflecting to help you get a better understanding of why individuals deflect emotions in relationships.

What is deflecting?

Deflecting can be used as an unintentional defense mechanism from psychological trauma – or it could be a very malicious and deliberate way to cause harm.

Deflecting in a relationship can feel like your partner is turning your attention away from their behavior and, instead, blaming everything on you.

Not only does a deflecting partner avoid taking responsibility for what they did wrong, they can also invalidate your feelings by denying your emotional response to their actions. This can make you question your own thoughts and deny your feelings. Deflecting can be easier to recognize during an argument, but it can happen in any scenario (e.g. during a meeting, on a date, playing a card game, etc.) and is often harder to spot.

What are some examples of deflection?

Changing the subject

Deflecting can frequently take place in an argument is when someone abruptly changes the subject after their behavior is called into question. The deflector will redirect the conversation to focus on something their target did wrong to escape having to take accountability for their own actions.

Examples of changing the subject:

- "I only lied because you always overreact. So really it's your fault."

- “I don’t want to talk about this especially when you did something wrong as well.

”

” - "Oh, yeah? Well, I didn't get mad when you did it a few months ago."

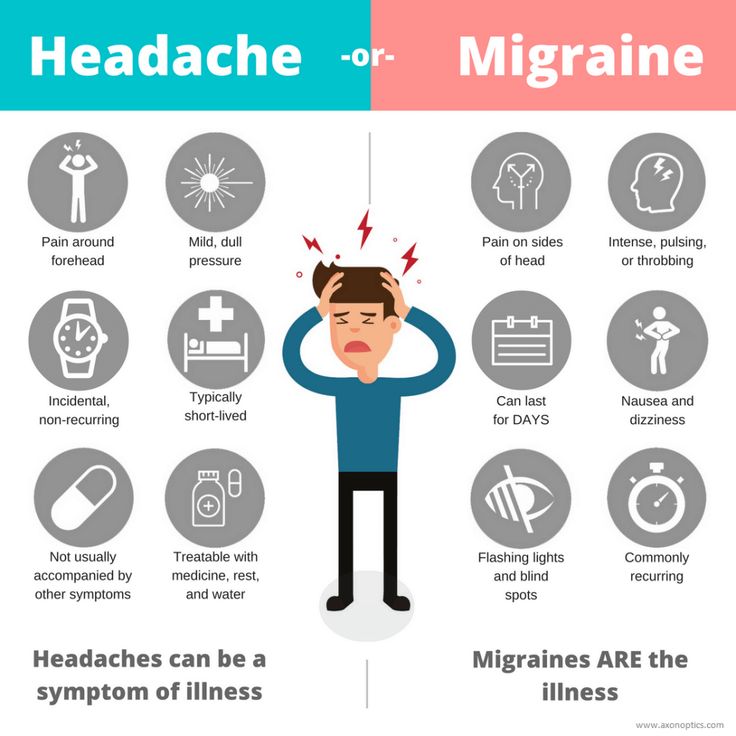

Gaslighting

Gaslighting happens when someone denies your thoughts, feelings, and overall sense of reality. It can lead you to question your version of events, and even make you feel the need to apologize for things that aren’t your fault.

Examples of gaslighting:

- "You shouldn’t feel bad because it's not that big of a big deal."

- "That never happened at all. It’s all in your mind…you probably dreamed it."

- “I never said that - don’t put words in my mouth.”

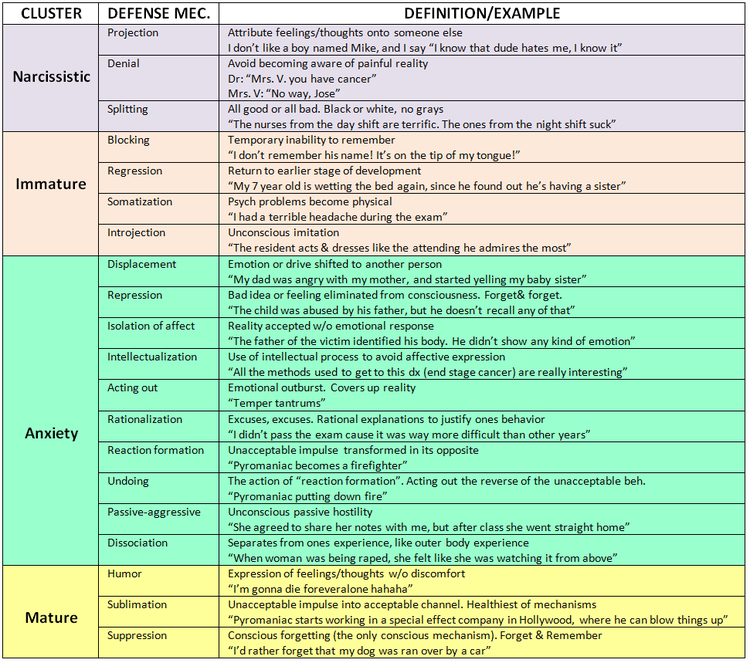

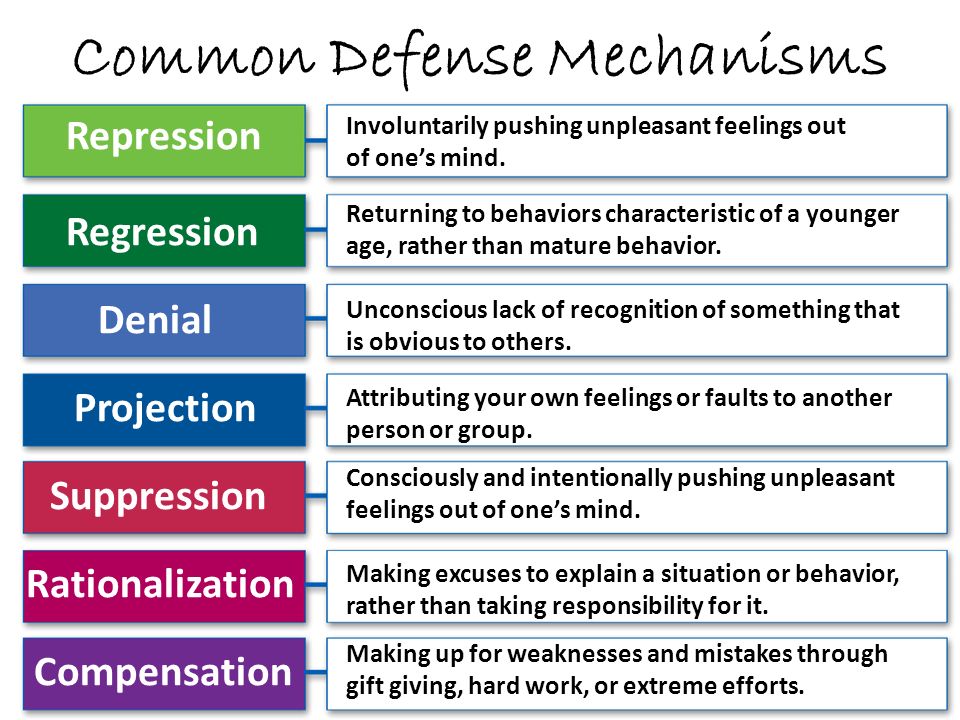

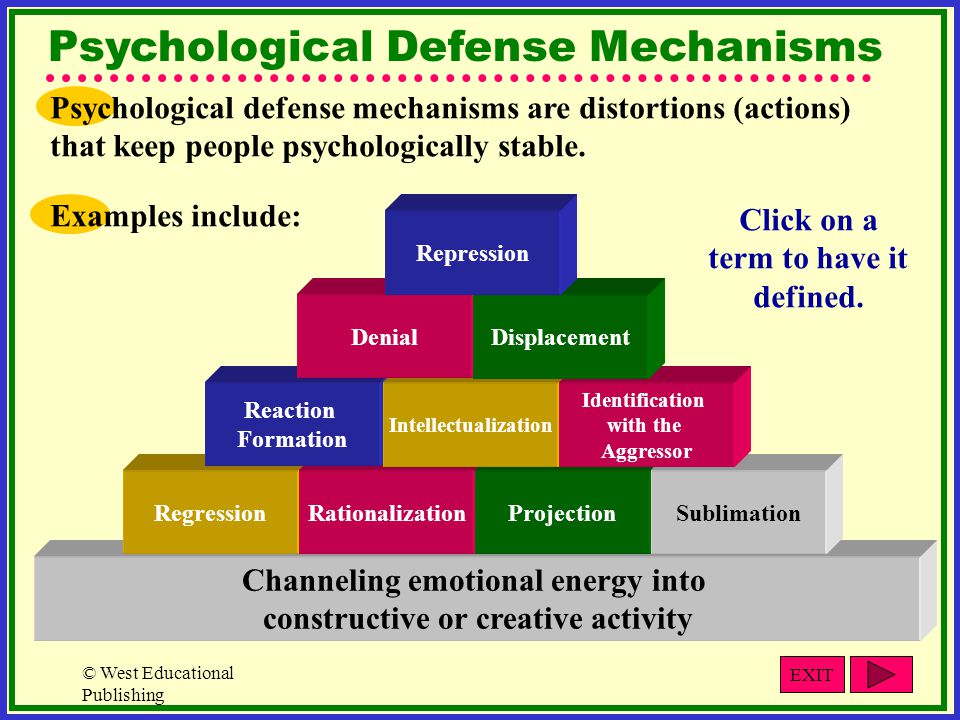

Projection

This refers to someone unconsciously taking unwanted emotions or traits they don’t like about themselves and attributing them to someone else.

An example of projection could be a cheating spouse who accuses their spouse of infidelity:

- “I saw the way you looked at them. You can’t tell me there’s nothing going on there.”

- “Why won’t you give me your cell phone if you’ve got nothing to hide?”

Attacking

Deflectors may be so desperate to get the attention off themselves, they lash out and attack their victim. This can include name-calling, criticizing, mocking, making inappropriate or triggering jokes, yelling, swearing, interrupting, and threatening you. Just as a physical attack can cause pain and discomfort, a verbal attack can cause immediate emotional pain or discomfort.

This can include name-calling, criticizing, mocking, making inappropriate or triggering jokes, yelling, swearing, interrupting, and threatening you. Just as a physical attack can cause pain and discomfort, a verbal attack can cause immediate emotional pain or discomfort.

Examples of attacking:

- "Who cares what you think? You're just an idiot."

- "If you bring this issue up again, this relationship is over."

- “It looks like you’ve gained weight - you should really eat healthier.”

Why do people use deflection?

There are times when we all make a mistake that may result in negative repercussions, or even require punishment.

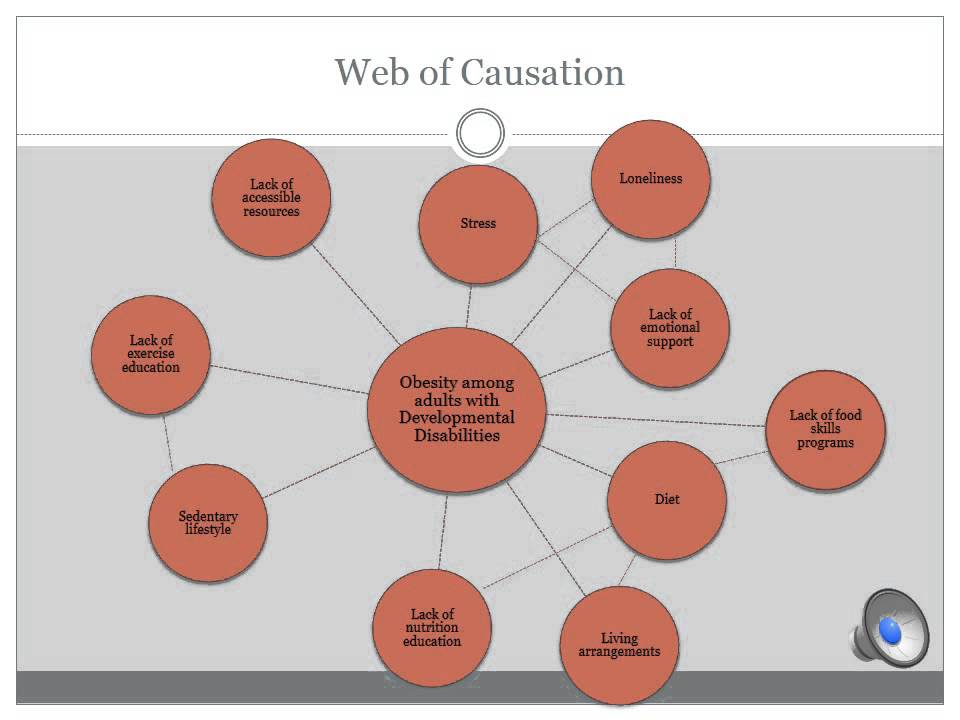

Sometimes deflection is an internalized defense mechanism we use to protect ourselves; other times, our partner may simply lack the emotional maturity to accept responsibility for the mistakes they’ve made. Anxious people typically don’t mean to harm anyone else by deflecting, but they could be too nervous about what will happen if people believe that they made a big mistake. If a child was emotionally abused or highly criticized for every mistake they made, they will use psychological deflection as a way to avoid punishment and continue using this coping mechanism into their adulthood.

If a child was emotionally abused or highly criticized for every mistake they made, they will use psychological deflection as a way to avoid punishment and continue using this coping mechanism into their adulthood.

Deflection can also be used as a narcissistic abuse tactic to avoid accountability for their wrongdoings and ensure that no one ever sees them as being less than perfect. These individuals suffer from an inflated ego, and will do whatever it takes to make themselves look as good as possible, even if that means making others look bad on purpose. Narcissists do not care who they might hurt in the process of deflection; in fact, they may even master their strategy of psychological manipulation to trigger the emotions of their target.

How can deflection be harmful?

Owning your mistakes allows you to resolve the issue right away and learn from what you did to avoid making the same mistake again. However, when you try to place the blame on someone else and avoid taking accountability, the root of the issue will never be fixed, and tension will continue to build within the relationship.

Constant deflection can indicate one of many red flags in an abusive relationship. As with other forms of verbal abuse, it can cause short and long-term consequences, as well as low self-esteem, depression, anxiety, chronic stress, and other mental health issues.

In some cases, narcissists can be so abusive and manipulative to the point where their behavior elicits you into lashing out, insulting them, or even behaving violently. This is known as reactive abuse, in which the victim is provoked into reacting in a way that, out of context, might seem abusive. In reality, however, the victim is simply overwhelmed with being abused.

How do you handle someone who uses deflection tactics?

Stand your ground. Before you can address the deflecting, you must be honest with yourself and acknowledge what you are experiencing. You must communicate how you feel before you can begin to take steps to gain back control. Remember, you are not responsible for your partner's behavior, but you can offer them support if they are willing to acknowledge their weaknesses and make the necessary changes.

Set boundaries. Make it clear that you will not partake in unreasonable arguments or overlook verbal abuse. For instance, if your partner refuses to listen to your perspective, or if they cannot control their temper, the conversation will be over, and you will leave the room.

Limit your exposure. Take some time (i.e. a few hours or days) away from your significant other, if you can, and spend time with people who love and support you. Limiting exposure with the person can give you space to reevaluate your relationship and define what a healthy relationship should look like.

End the relationship. If there is no sign of improvement, or the relationship becomes increasingly worse, then you will likely need to go your separate ways. In some situations, like if you live with them, have children together, or are dependent on them in some way, it may be difficult – or impossible – to break things off immediately. In these cases, reach out to a trusted loved one to start working on an exit plan.

Learning to admit to your faults and shortcomings is a crucial part of building trust and maintaining a healthy relationship – not only with your romantic partner, but with everyone you know. If you want to learn more about the state of your current relationship, take our healthy relationship quiz.

Deflection in psychology – what it is, why people use it, and how to deal with it

The healthiest and most mature reaction we can have when confronted with our own mistakes is to stop, think about the situation, and apologise. However, this can be a difficult and uncomfortable thing to do, which is why we often end up shifting the blame away from ourselves. In psychology, this is called deflection, and it’s one of the most common defence mechanisms.

What is deflection?

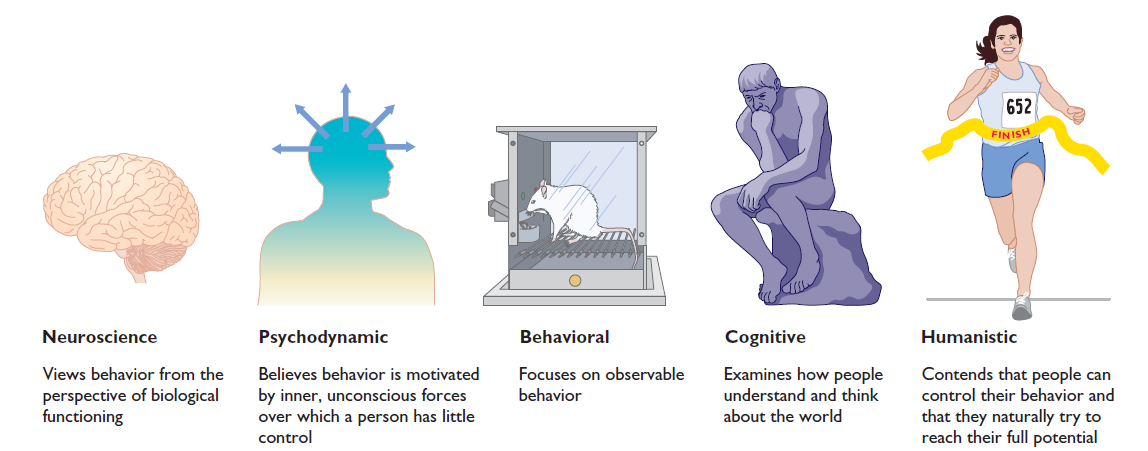

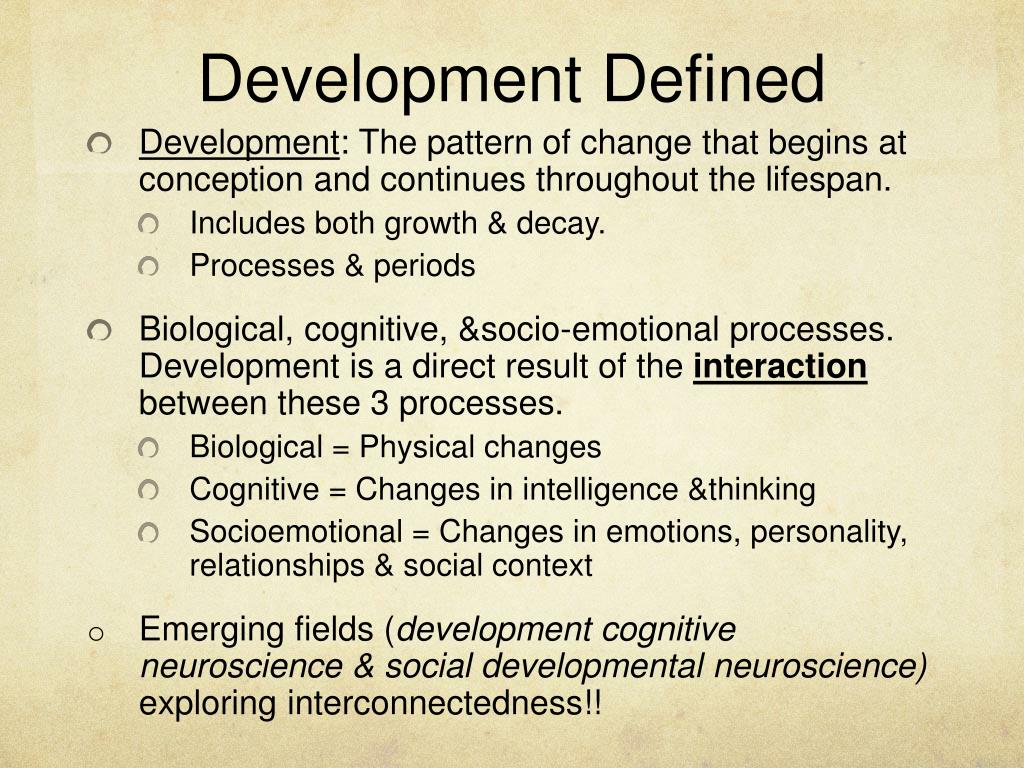

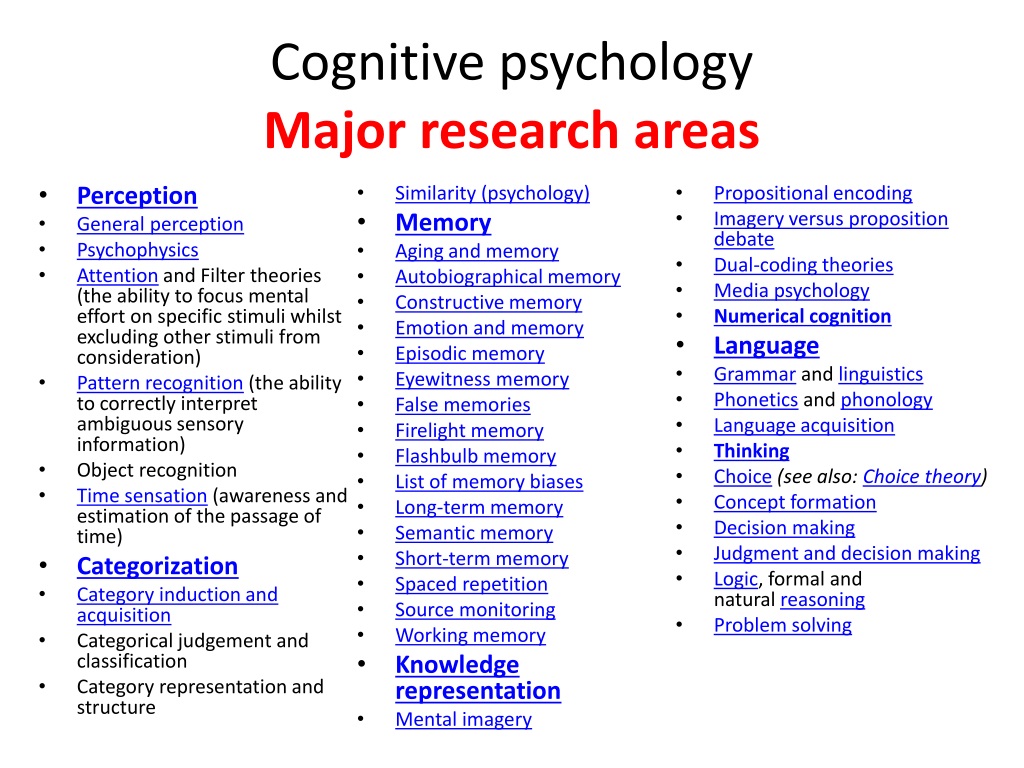

According to Sigmund Freud, people use 12 defence mechanisms to protect themselves from difficult, anxiety-inducing thoughts. Deflection is one of these mechanisms.

Deflecting typically appears in conflictual situations, when a person is confronted with their mistakes. Instead of accepting responsibility and facing the uncomfortable situation head-on, the deflector will try to move the focus from themselves, usually by passing the blame onto someone or something else.

Everyone resorts to deflection from time to time, especially in childhood. However, when someone uses deflection constantly and refuses to accept the consequences of their own actions, deflection can become pathological and affect not only the mental health of the deflector, but also of those they interact with.

Examples of deflection

Even though we may not always be aware of them, examples of deflection can be found everywhere in day-to-day life, in all types of relationships.

Deflection in romantic relationships: If you find out that your partner is cheating on you and you confront them about it, they deflect the blame, telling you that they only cheated on you because you did something wrong or didn’t offer them enough attention.

Deflection in friendships: When telling your friend about one of their negative behaviours, they get defensive and belittle you instead.

Deflection between family members: After explaining to a parent that their actions hurt you, they say that they didn’t do anything wrong and that it’s your fault for being too sensitive.

Deflection in public: Politicians who are questioned about their lack of results can pass the blame to their predecessors.

Deflection at work: A deflecting colleague will try to avoid looking bad in front of superiors and shift the focus on another employee, saying that a bad outcome is actually their fault.

Why do we deflect?

Although no one likes it when a person deflects, it’s important to remember that deflection isn’t an inborn trait – it’s a learned habit. We first learn deflection as children, when we lie about our actions to avoid getting in trouble, and this is actually a normal part of development.

As adults, we can use deflection either consciously or unconsciously, and, in general, we deflect because we don’t want to feel bad and take a blow to our self-esteem. After all, it’s easier to blame a colleague for an unsuccessful project than admit that it was our fault and risk looking bad in the eyes of a supervisor.

We can also deflect when we’re not yet ready to face certain emotions and memories that others bring up. This isn’t because we want to harm them, but because we want to protect ourselves. However, deflection can also be used as a manipulation technique by people with narcissistic personality traits, who exercise control over others by demolishing their self-esteem.

Signs that someone may be a deflector:

- Nothing is ever their fault. Whenever something goes wrong, they pass the blame to someone else.

- They don’t know how to deal with conflict and look visibly uncomfortable talking about their mistakes.

- Every time you try talking about their mistakes, they shut down or tell you that you misinterpreted things.

- After many unsuccessful attempts, you may end up avoiding confrontation altogether because it makes you guilty or frustrated.

Deflection and narcissism

The main difference between deflection as a self-defence mechanism and deflection as a manipulation technique is that narcissists lack empathy and, when they deflect the blame to the person who accused them in the first place, they try to increase their control over them. Quite often, deflection is followed by an attack because narcissists love being right all the time, and they’ll quickly start accusing you of things you may or may not have done. In some cases, narcissists can go beyond deflection and use gaslighting – a manipulation technique that involves questioning the other person’s experiences or reality.

How to react when a person is deflecting

Interacting with a person who deflects can be incredibly frustrating, and when this behaviour persists, it can make you question yourself and even lead to depression and anxiety symptoms. When a long-time friend, romantic partner or relative deflects blame, that can make you feel that your voice doesn’t matter or make you want to avoid direct confrontation.

Once you’ve realised that a person is a deflector, the most important thing to do is stay calm and patient. More often than not, losing your cool and starting an argument will legitimise the deflector’s feelings and give them more to work with. Instead, stay calm and use short sentences to prevent the situation from escalating. You can also try and confront the deflector, saying that their lack of acceptance hurts your feelings. They may acknowledge this defence mechanism, and together you can explore ways that they can overcome this. However, deflectors don’t always want to change and, in that case, you have to accept that you can’t control their behaviour, only your reaction to it. Depending on the role they play in your life, you can try to set boundaries and limit contact with them, but if the relationship is too toxic and affects your mental health, cutting all contact could be better for you in the long run.

However, deflectors don’t always want to change and, in that case, you have to accept that you can’t control their behaviour, only your reaction to it. Depending on the role they play in your life, you can try to set boundaries and limit contact with them, but if the relationship is too toxic and affects your mental health, cutting all contact could be better for you in the long run.

What if you’re the deflector?

If you recognise yourself in the descriptions above, that’s a good sign because one of the hardest parts about deflecting is being aware that you’re doing it and committing to change. To stop using deflecting as a coping strategy:

- Look at the conflict objectively instead of letting yourself be controlled by your emotions.

- Take a mental note of your first reaction when someone brings up a mistake.

- When someone points out a mistake, try to stay open and acknowledge their feelings instead of shutting down or immediately assuming they’re wrong.

- Allow yourself to be vulnerable and accept that it’s normal to make mistakes.

If you have been using deflection to cope with negative memories and experiences for years, breaking the pattern can be hard. A therapist can help you understand why you resorted to deflection in the first place and suggest healthier coping strategies.

More Articles by UK Therapy Guide

Meet Our Therapist - Part Two

by UK Therapy Guide

Meet Naomi Magnus, who has been with us for years as one of our therapists. She is here to tel you more about UK Therapy Guide and online therapy/

Read More

Meet Our Therapist - Part One

by UK Therapy Guide

Meet Vicky Day, one of our long standing therapists. Here is what she has to say about working with UK Therapy Guide and online counselling.

Read More

Relationship and Couples Therapy

by UK Therapy Guide

Every relationship has problems at some point. If you are lucky in your relationship, these will only be minor problems that you both can get past because of the love and respect that you have for each other. However, this will not be the case with every relationship. There are so many people struggling with their current relationships for various reasons. If you are experiencing some difficulties in your relationship, perhaps couples therapy could be for you?

If you are lucky in your relationship, these will only be minor problems that you both can get past because of the love and respect that you have for each other. However, this will not be the case with every relationship. There are so many people struggling with their current relationships for various reasons. If you are experiencing some difficulties in your relationship, perhaps couples therapy could be for you?

Read More

Finding the Right Therapist

by UK Therapy Guide

When you first decide that you would like or need to have therapy, one of the big questions that seems to spring to everyone’s mind is “how do I find a therapist?”. In this article, we talk about how you can find the right therapist for you.

Read More

Bereavement Counselling

by UK Therapy Guide

The loss of a loved one can be devastating in many different ways and can affect your wellbeing. Everyone grieves differently, but rest assured, you do not have to go through it alone.

Read More

Online Counselling and How it Can Help You

by UK Therapy Guide

Online counselling is a great way to receive therapy via video conferencing or Skype without the need of having to leave your home. This article explains how useful online therapy can be and how it can help you moved forward without the need of having to visit a counsellor / therapist face to face at their practice. Getting out and about isn't always easy for people, so online therapy is a an excellent alternative for many people all over the world requiring therapy.

Read More

Can getting therapy for anxiety really help?

by UK Therapy Guide

With suffers of anxiety on the up-rise, how can getting anxiety counselling help you? This article explains more, along with some of the different types of anxiety that people suffer from.

Read More

Career Counselling – opening the door to job satisfaction

by UK Therapy Guide

You may decide that you need career counselling to help with choosing a new role or even leaving the one that you are in currently. Useful at any time in life, career counselling is not only suitable for those about to enter the work field; with your working life taking up so much of your time, it is important to get it right and working with an experienced career counsellor can help.

Useful at any time in life, career counselling is not only suitable for those about to enter the work field; with your working life taking up so much of your time, it is important to get it right and working with an experienced career counsellor can help.

Read More

Jungian Analysis – getting in touch with your individual psyche

by UK Therapy Guide

Jungian analysis or psychology originates from ideas put forward by Carl Jung. It focuses on the importance of each individual's psyche and ways in which they can be made ‘whole’ again.

Read More

Finding a counsellor needn’t be hard; here are some useful tips to help

by UK Therapy Guide

When trying to find the right counsellor to suit you, they need to be a good fit for your personality and problems. At the same time, you need to feel safe and secure with them so look for those that have professional qualifications and accreditations.

Read More

Interpersonal therapy as a treatment for depression: Is it right for you?

by UK Therapy Guide

If you are feeling depressed and seeking help via therapy, you may find that your counsellor recommends the use of interpersonal therapy (IPT). If this is something you have not heard of before and feel slightly concerned about it, let’s take a look at what this form of therapy involves and how it works.

If this is something you have not heard of before and feel slightly concerned about it, let’s take a look at what this form of therapy involves and how it works.

Read More

Troubled teen? Try Family Therapy

by UK Therapy Guide

As parents of a teenager, the path forward is not always an easy one. At times you may find yourselves disagreeing about what discipline to put in place, what is at the root of any problems that manifest or even how to react. If siblings are involved, they may kick off, feeling left out because all of the attention is on the teen who is troubled and not on them. In these circumstances, family therapy can help all parties involved.

Read More

Miscarriage – life after death

by UK Therapy Guide

It makes no difference whether this is your first miscarriage or one of several, nor whether you have other children at home; losing a baby due to miscarriage is like any other loss and if not handled correctly, can leave the mother and even the father and rest of the family in pieces.

Read More

How does family therapy help and what is the goal?

by UK Therapy Guide

The aim of family therapy is to ensure that all members of the group are operating in a functional and positive way. If there are any problems creating pressures within the unit, either psychological, emotional or mental, the whole family may fall apart of suffer damage.

Read More

What is the purpose of family therapy and what are the different types?

by UK Therapy Guide

We all have a family, each of them very different. It may be made up of blood relatives but also adopted or fostered members or even people who figure greatly and have been present for a long time. Whatever the mix and no matter how big, small or complex, it will have a big effect upon the way that we develop and behave, from the beginning to the end of our lives.

Read More

How does Gestalt therapy work and how will it benefit me?

by UK Therapy Guide

If your counsellor thinks that you will be a good fit for Gestalt therapy, they will show you how to truly experience what is happening rather than relying upon your understanding of the event. During your sessions together, your thoughts, beliefs, feelings and way of behaving will all be examined in depth.

During your sessions together, your thoughts, beliefs, feelings and way of behaving will all be examined in depth.

Read More

What are the key concepts of Gestalt therapy?

by UK Therapy Guide

Gestalt therapy dates back to the 1940s and was developed by Fritz Perls. A type of psychotherapy, it works on the basis that everyone is a whole comprised of mind, body and soul, as described by the relational theory principle.

Read More

Relationship on the rocks? You need couple’s therapy

by UK Therapy Guide

There is no doubt about it; relationships are hard work. Just like a living thing, they require constant attention, nourishment and care if they are to grow, survive and thrive. So what should you do if you are going through a difficult patch and it seems your relationship is headed for the rocks? This is where couple’s therapy can be a great help.

Read More

Get help and support from your therapist via Skype counselling

by UK Therapy Guide

It can be difficult if you need the support of one-to-one counselling but don’t feel comfortable talking face-to-face. But there is a solution and a very good one; Skype therapy allows you to fully engage in counselling and psychotherapy without having to leave your home.

But there is a solution and a very good one; Skype therapy allows you to fully engage in counselling and psychotherapy without having to leave your home.

Read More

Treat your difficult emotions by talking on the telephone

by UK Therapy Guide

Telephone therapy is a form of counselling that involves you being treated by a therapist via phone. You will be able to talk freely about how you feel and what sort of distressing thoughts you may be having.

Read More

Special psychology. What is "Special Psychology"? The concept and definition of the term "Special Psychology" - Glossary

Glossary. Psychological dictionary.

- A

- B

- B

- D

- D

- F

- W

- and

- K

- L

- M

- H

- O

- P

- P

- C

- T

- W

- F nine0005 Х

- C

- H

- W

- E

- I

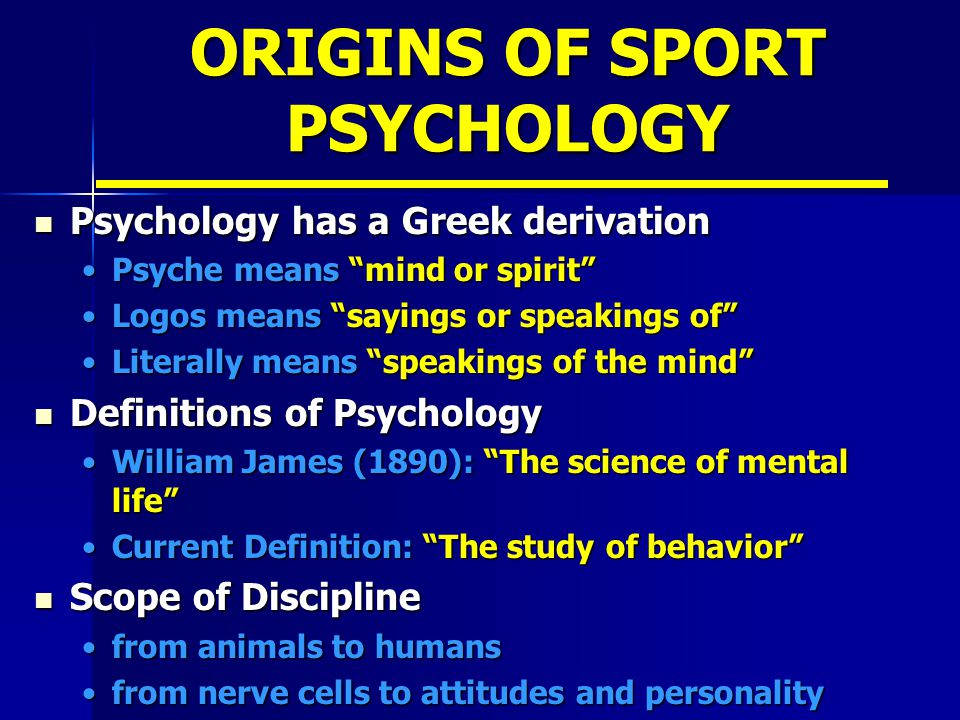

Specialized psychology is a field of developmental psychology focused on the study of special conditions inherent in children and adolescents with such developmental features that slow down their social adaptation, interfere with involvement in the educational process and hinder personal growth.

Special psychology is sometimes called correctional, it is part of defectology - the science of the upbringing and development of children with physical and mental disabilities. Over its century-old history, special psychology has been able to take shape as a separate discipline and significantly expand the range of tasks: now it includes several sections that are differentiated depending on the area in which one or another deviation from the norm is manifested. For example, deaf psychology studies the psychology of children with hearing problems. nine0003

Logopsychology is aimed at studying the psychology of children with speech disorders. Tiflopsychology considers the condition of children who have vision problems. The task of special psychology is such a formation of a personality that will make it possible to compensate for the lack of work of an absent or poorly realized function of the body, which is of a natural nature. This substitution or restructuring occurs due to the techniques used, developed taking into account the development of a particular child. nine0003

nine0003

The main method of work within special psychology is a psychological experiment, which can be individual or group, depending on the situation. The method of observation, questioning and studying the products of activity (drawings, written works ...) is also actively used.

< Social psychology

Sports psychology >

Popular terms

Special psychology

Illusion of defect: 4 principles of communication with special children

Educator and psychologist Christel Manske has been working with autistic children, children with trisomy, ADHD and other disabilities for over 40 years. Her view of such children is unusual - bright, free from stereotypes, it restores our own integrity and humanity.

Media news2

new on site

- Ghosts of the past: how I lived in Auschwitz - memories of a child of concentration camp prisoners

- “I can't keep my interest in anything.

I leave everything halfway”

I leave everything halfway” - "It's inconvenient to ask your husband for money every time, but he doesn't understand hints"

- Scientists have found out which partners men and women choose in difficult times

- "I see prophetic dreams": how the unconscious gives clues - personal experience

- Man with nails: what is the new masculinity

- "Fandorin. Azazel": how did the new series based on the novel by Boris Akunin turn out

- “My husband accused me of giving birth to a child for myself, freaked out and left”

Today they read

- “I ran away from an abuser. She lowered my self-esteem to the bottom"

- "My husband is tired of family slavery, and my children and I are a burden to him"

- “A friend called after a year and a half of ignorance and began to pour insults. What's the matter?"

- "Tell me, it won't come true": why this sign really works

- “During a break in the relationship, the wife slept with another man.

We are together again, but I can't forgive her"

We are together again, but I can't forgive her" - "Dildos Changed My Life": Ceramic Artist Saved Her Back Pain and Started Making Sex Toys

Psychologies invites

Psychologies Telegram channel

SUBSCRIBE

new issue WINTER 2022 — 2023 No. 72

More details

special projects

Ideas about the mental norm in clinical psychology //Psychological newspaper

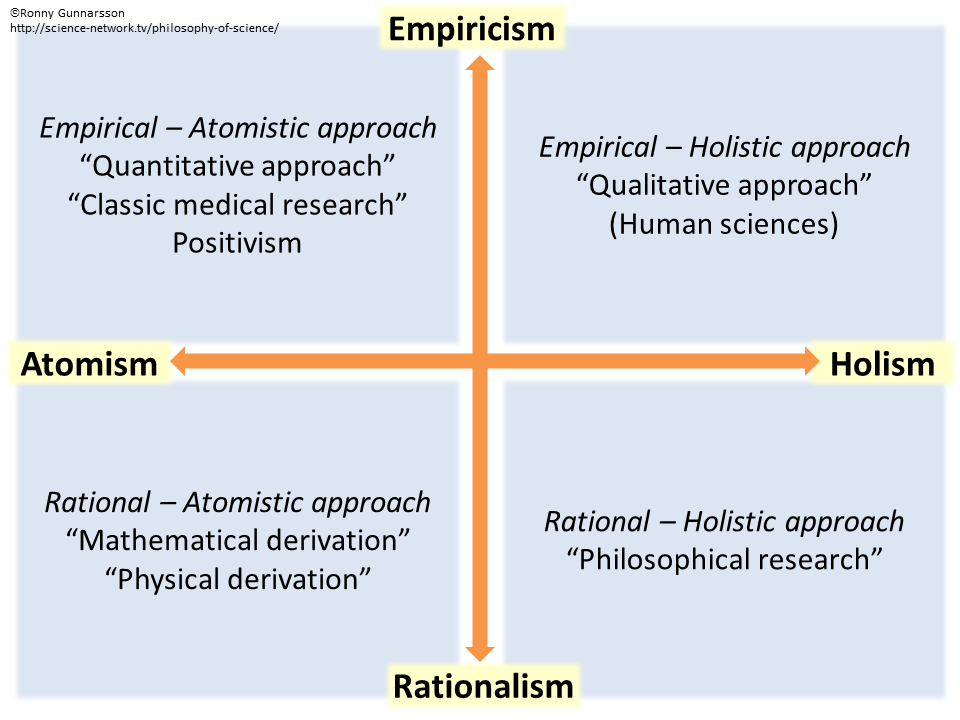

The category of mental norm is an important component of the conceptual apparatus of psychology. At the same time, in recent decades, the definition of the mental norm and its boundaries has become a field of lively discussions. Today, there are many criteria for the norm, proposed by different researchers. Clinical psychologists are not left out. After all, the very emergence of clinical psychology as an independent field of scientific knowledge (in particular, the formation of its historically earliest field - pathopsychology) was associated with the need for experimental "study of abnormal manifestations of the mental sphere, since they illuminate the tasks of the psychology of normal persons" [V. M. Bekhterev, 1907, p. 8]. Mental disorders V.M. Bekhterev considered deviations and modifications of the norm, subject to the same basic laws. “But, thanks to a more convex picture of the pathological manifestations of mental activity, often the relationships between the individual constituent elements of complex mental processes are much brighter and more prominent than in the normal state” [V.M. Bekhterev, 1903, p. 1].

M. Bekhterev, 1907, p. 8]. Mental disorders V.M. Bekhterev considered deviations and modifications of the norm, subject to the same basic laws. “But, thanks to a more convex picture of the pathological manifestations of mental activity, often the relationships between the individual constituent elements of complex mental processes are much brighter and more prominent than in the normal state” [V.M. Bekhterev, 1903, p. 1].

In recent years, the task of system analysis of the category of mental norm has become increasingly relevant. This is due, first of all, to the logic of the modern development of clinical psychology, which, along with the preservation of interest in traditional pathological models, is increasingly turning to the study of the functioning of the normal psyche [E.D. Chomskaya et al., 1997; V.V. Nikolaev, G.A. Arina, 1996; A.Sh. Tkhostov, 2002; and etc.]. Interest in the problem of the norm today is also due to the need for a comprehensive solution to increasingly complex diagnostic and rehabilitation tasks.

What views on the norm "work" in clinical psychology? Do they influence the development of its methodology, methods and specific methods of empirical research? And can clinical and psychological practice change and renew ideas about the mental norm? nine0003

The mental norm is often defined as the absence of any pathological manifestations, mental disorders. A serious drawback of such a "negative" definition is that it only approximately outlines the boundaries of the normal, but does not reveal its essence, qualitative specifics. In addition, consideration of the norm within the framework of the traditional dichotomy "norm - pathology" also requires the definition of the latter. It would seem that the solution of such a problem should be facilitated by the steady interest of medicine and natural science that has been preserved for centuries in various phenomenological manifestations of pathological abnormalities, in their role in the processes of biological evolution. However, medicine is still dominated by a simplified understanding of pathology as a disease, a deviation from the norm. Psychology must come to its own, deeper understanding of pathology, relying not only on the medical, but also on the philosophical tradition, in which "pathos" means "changes in the soul under the influence of any influence, suffering, passion" [Philosophical Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1983]. We should not forget that the norm and pathology are not mutually exclusive concepts: a normal, mentally healthy person should not have psychopathological syndromes, but individual pathological symptoms may well occur [B.S. Bratus et al., 1988]. Interestingly, one of the important signs of the norm is the availability of such pathological manifestations of self-compensation [T.V. Akhutina, 2002]. In general, we can say that the concepts of norm and pathology are culturally and historically conditioned, their boundaries are quite mobile; between the norm and pathology there is a complex continuum of transitional states.

However, medicine is still dominated by a simplified understanding of pathology as a disease, a deviation from the norm. Psychology must come to its own, deeper understanding of pathology, relying not only on the medical, but also on the philosophical tradition, in which "pathos" means "changes in the soul under the influence of any influence, suffering, passion" [Philosophical Encyclopedic Dictionary, 1983]. We should not forget that the norm and pathology are not mutually exclusive concepts: a normal, mentally healthy person should not have psychopathological syndromes, but individual pathological symptoms may well occur [B.S. Bratus et al., 1988]. Interestingly, one of the important signs of the norm is the availability of such pathological manifestations of self-compensation [T.V. Akhutina, 2002]. In general, we can say that the concepts of norm and pathology are culturally and historically conditioned, their boundaries are quite mobile; between the norm and pathology there is a complex continuum of transitional states. nine0003

nine0003

In clinical psychology, there is also an understanding of the norm as an average value (standard), a kind of criterion for comparing test results [K.M. Gurevich, 1995]. It is widely used in studies of individual mental functions, carried out using the methods of mathematical statistics. However, according to a number of authors, the average statistical norm should not be absolutized [A.A. Korolkov, V.P. Petlenko, 1977; V.V. Luchkov, V.R. Rokityansky, 1987; B.S. Bratus, 1996]. Such an understanding excludes all unusual mental manifestations from the category of the norm, does not give an idea of the qualitative characteristics of mental activity, of the individual characteristics of the personality and behavior in general. There are aspects of processes and phenomena that cannot be quantified and cannot be compared with the statistical norm. In addition, it is limited by many limits (age, population, environmental, etc.). In some cases, it is advisable to rely on the understanding of the mental norm as a certain complex of individual characteristics of a person and activity [B. S. Bratus, 1996; E.A. Klimov, 1997].

S. Bratus, 1996; E.A. Klimov, 1997].

There is also a view of the norm as an opportunity for adaptation. Many mental and behavioral disorders are considered precisely as states of stable maladjustment. However, one should not forget that the disease, in turn, can be considered as a form of adaptation to the special conditions of existence, that in some cases pathological processes can be adaptive and remain adaptive as long as they retain their protective function [I.V. . Davydovsky, 1968; and etc.]. The view of the norm as an opportunity for adaptation has a number of other limitations. When it comes to social adaptation, which is a necessary condition for the effective interaction of members of the society in the process of joint activities and communication, it must be taken into account that the requirements of the society for the individual are always ambiguous, just as the society itself is heterogeneous. Throughout life, a person is in the process of constant search for that social group or subculture in which its features are evaluated as characteristic of the norm. In modern conditions, a subject, not only successfully adapted to a given environment, but also capable of actively transforming it, should be recognized as normal. nine0003

In developmental psychology, the norm is viewed as a range of fluctuations, as a specific historically conditioned system of indicators of a given population, within which there is a variety of individual options, as a dynamic deployment of an optimal ontogeny program determined by biological and sociocultural factors [Development Psychology, 2001; N.Ya. Semago, M.M. Semago, 2000]. Such a view of the norm is logically connected with ideas about the zone of proximal development; the norm becomes a means of identifying favorable and unfavorable conditions of mental ontogenesis. nine0003

Finally, the mental norm can be considered as the presence of certain personality traits, stable moral guidelines: a genuine interest in the world, optimism, productivity, the ability to self-realization, to freely choose from various alternatives [I. I. Mechnikov, 1987; E. Fromm, 1992, 1994; B.S. Bratus, 1998; and etc.]. Here the norm acts as a kind of "ideal", "sample" of a harmonious personality.

I. Mechnikov, 1987; E. Fromm, 1992, 1994; B.S. Bratus, 1998; and etc.]. Here the norm acts as a kind of "ideal", "sample" of a harmonious personality.

Interestingly, different areas of clinical psychology demonstrate "heterochronism" in the development of the problem of the norm. In pathopsychology, which studies “patterns of the decay of mental activity and personality traits in comparison with the regularities of the formation and course of mental processes in the norm” [B.V. Zeigarnik, 1986, p. 5], comparison of the results of patients with those of healthy subjects was initially almost mandatory. Neuropsychological research presents a mixed picture. The lack of comparison with the results of normal subjects is characteristic of many neuropsychological works of the 60s and 70s. last century. The interest of neuropsychology in the problem of the mental norm was clearly manifested only in the second half of the 1980s. and was due to an appeal to the study of individual differences and ontogenesis. Today, neuropsychologists are actively developing the problem of individual differences and the typology of the norm; talk about the need for a set of standards for different age periods and sociocultural conditions, about the importance of determining the relationship between the “psychological” norm and the norm established by objective medical indicators [E.D. Chomskaya, 2003; Yu.V. Mikadze, 2002; A.V. Semenovich, 2002; and etc.]. In modern clinical psychology, the interpretation of a number of symptoms is changing - they can be considered not as pathological manifestations, but as compensatory neoplasms of the psyche [N.K. Korsakova, E.Yu. Balashova, 1995; L.S. Tsvetkova, 2001].

Today, neuropsychologists are actively developing the problem of individual differences and the typology of the norm; talk about the need for a set of standards for different age periods and sociocultural conditions, about the importance of determining the relationship between the “psychological” norm and the norm established by objective medical indicators [E.D. Chomskaya, 2003; Yu.V. Mikadze, 2002; A.V. Semenovich, 2002; and etc.]. In modern clinical psychology, the interpretation of a number of symptoms is changing - they can be considered not as pathological manifestations, but as compensatory neoplasms of the psyche [N.K. Korsakova, E.Yu. Balashova, 1995; L.S. Tsvetkova, 2001].

Thus, at present, in clinical psychology, the process of comprehending the category of mental norm continues, the criteria underlying it are clarified and supplemented, and scientific areas are developing that set as their task theoretical and practical research in this subject area.

Retrieved : Balashova E.

Learn more