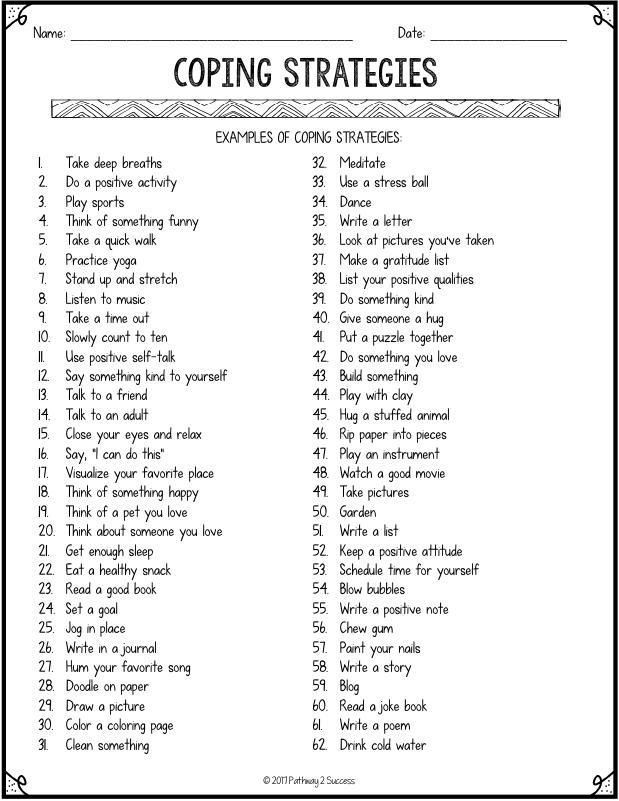

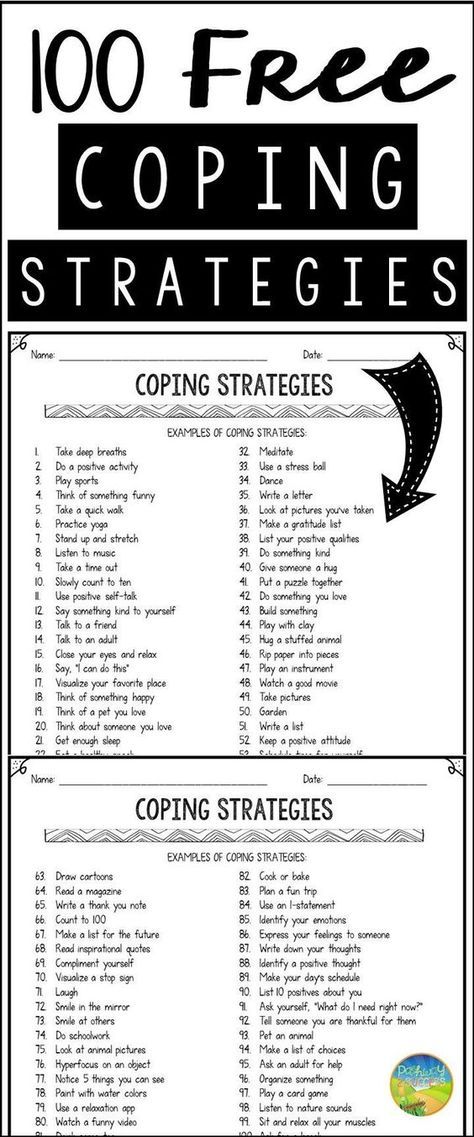

Example of coping

Coping Mechanisms: Definition, Examples, & Types

Coping Mechanisms: Definition, Examples, & TypesBy Sukhman Rekhi, M.A. What are coping mechanisms? Read on to discover various types of coping mechanisms and healthy ways to cope.

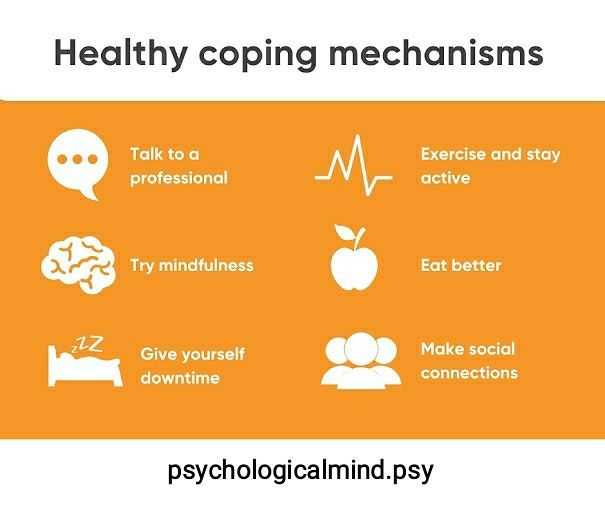

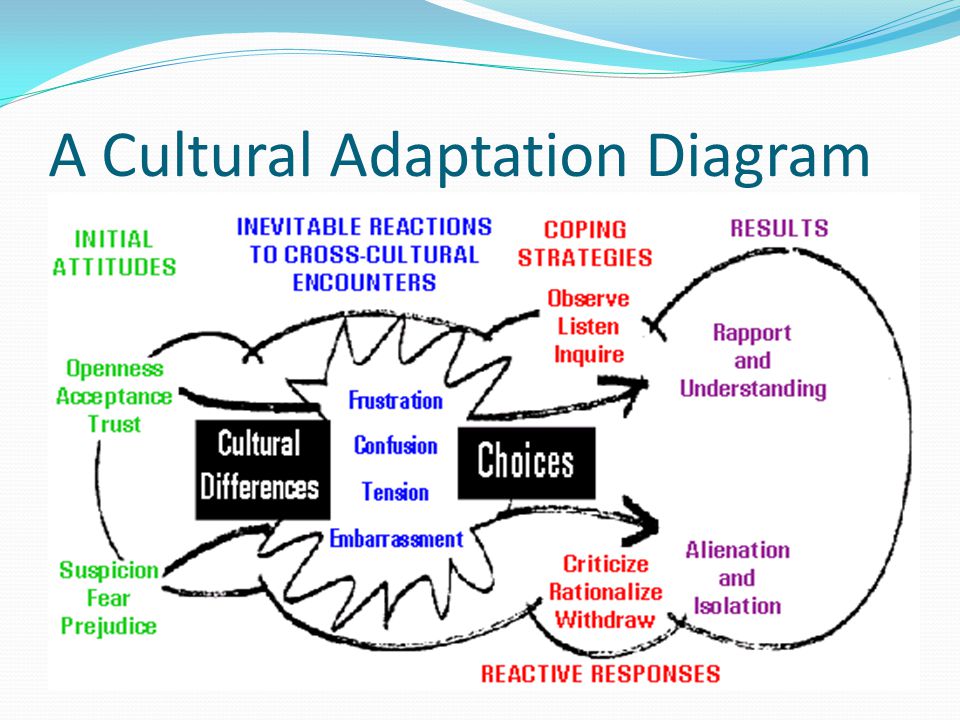

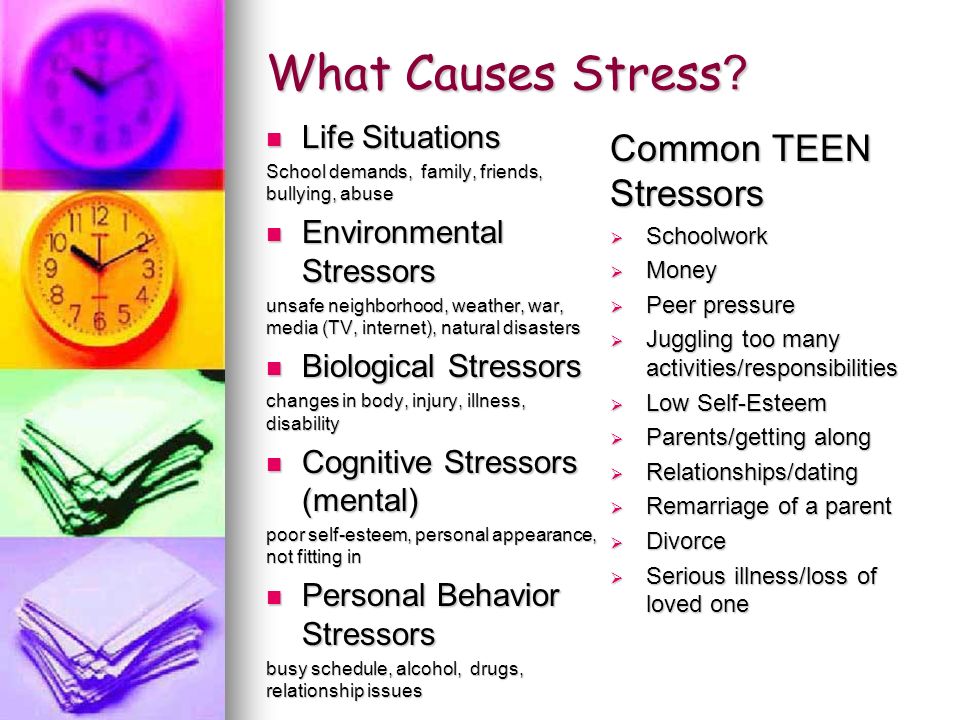

Learning how to effectively handle difficult moments in our lives is what healthy coping is all about. Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur? Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How toGrow Your Wellness Business Exponentially! ✓ Save hundreds of hours of time ✓ Earn more $ faster What Is a Coping Mechanism? (A Definition)While many of us may not be new to the concept of coping, it may be helpful to discuss the psychological definition of coping mechanisms. Coping mechanisms are cognitive and behavioral approaches that we use to manage internal and external stressors (Algorani & Gupta, 2021). Let’s break this down even further to gain a better understanding of the types of stressors and approaches to coping. Stressors that lead to coping

Let’s illustrate these approaches through an example. Perhaps you have been swamped with work and you miss your child’s school play. You may have had the date circled on your calendar for months (or more realistically, saved as an event on your phone), but maybe you had to stay late at a meeting, and by the time you left work there was too much traffic to make the play. Your child is visibly upset at you after the play and you feel disappointed in yourself for making them feel sad. Unfortunately, you can’t go back in time and make the play. What might you do now to cope with this stressful event?

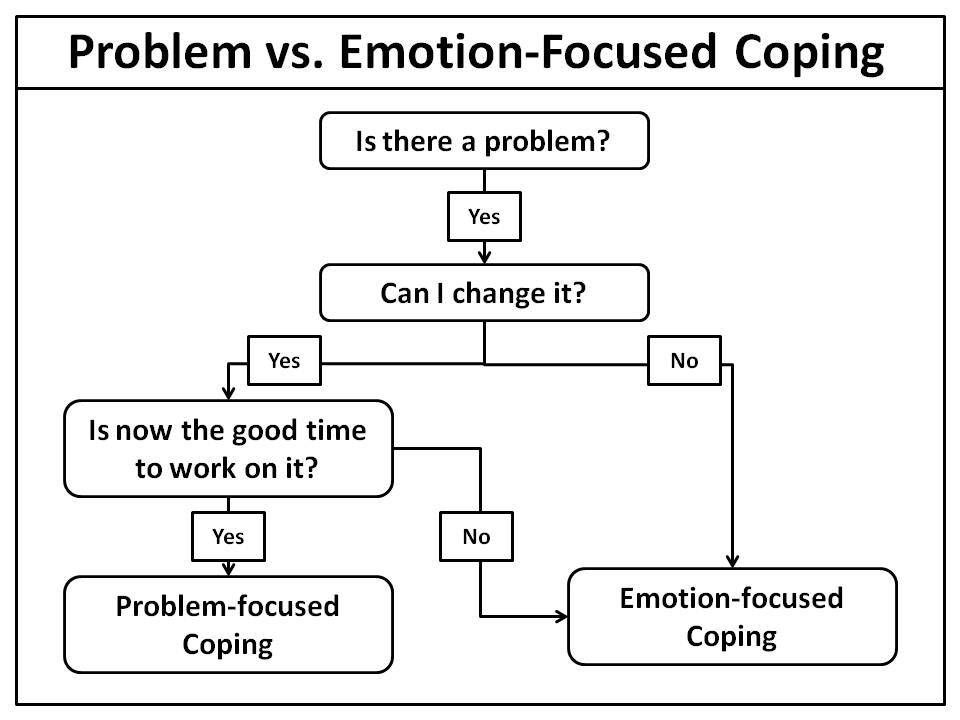

Coping Mechanism TechniquesWe may never be able to fully rid ourselves of stressors, no matter how resilient we are, but we do have the power to manage stress in healthy ways. Problem-Focused Coping refers to an actionable way to handle a stressful situation, much like the behavioral approach to coping we just talked about. This technique allows us to focus on tackling the problem itself. Typically, this coping technique is employed when we have control over a situation (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007). Here are some examples:

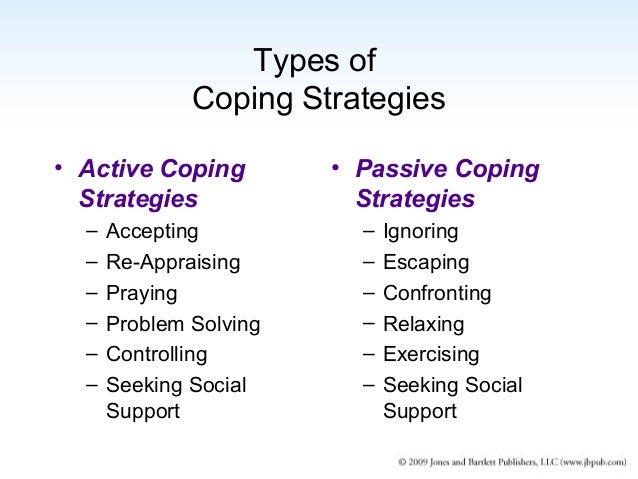

Coping Mechanism Styles When we deal with stressful situations, some of us may feel encouraged to deal with the problem right away, while some of us may want to evade the situation altogether. There is no one correct method to cope with life’s stressors, but it is important to be aware of distinct coping styles. Let’s take a look at two primary styles of coping.

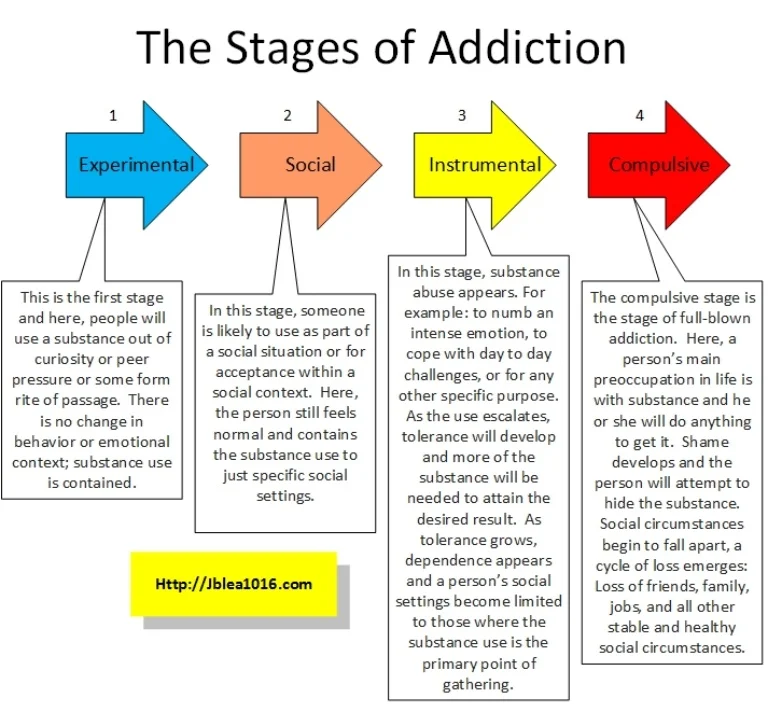

I like to think of this coping style as akin to the “laundry chair” in my bedroom. You know what I mean right? Somewhere in our homes, we all have this chair (or couch or treadmill or spot on the floor)that we throw random items on until we have to deal with them later. For me, it’s where I put my clothes that need to be folded, clothes that are folded but not put away yet, purses that I’ve taken out of the closet that need to go back, and sometimes even shopping bags with the items that I haven’t yet taken out of their packaging. Sometimes this “laundry chair” is perfectly clean, but one by one I add things to it until it becomes an overwhelming mountain of items that may or may not lead to some tears when I finally decide to clean. Some examples of avoidant coping may include not talking about the stressful situation, distracting yourself from the stressor such as by binge-watching a TV show, or escaping by resorting to alcohol or drug use. Coping Mechanism TypesBefore we get to specific coping mechanisms for various types of stress or mental health conditions, let’s elaborate a bit more on the types of coping mechanisms. So far, we have learned about various coping approaches, techniques, and styles. Here is a rundown of two dominant coping mechanism types: healthy and unhealthy.

Video: Unhealthy Coping MechanismsWant to learn more about unhealthy coping mechanisms? Check out this video: Coping Mechanisms for StressNow that we have set the blueprint for all different types of coping strategies and methods, let’s talk about specific coping mechanisms for particular situations. The following sections will offer a list of several different types of coping mechanisms which include problem-focused and emotion-focused coping tips. The primary goal of coping with stress is finding healthy ways to de-stress (Scheier, Weintraub, & Carver, 1986). Keep reading for some examples that you may want to try if you are overwhelmed or stressed out.

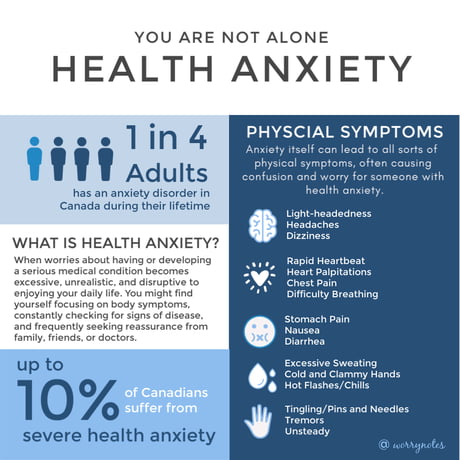

Coping Mechanisms for AnxietyEver experience your heart racing too fast, your palms starting to sweat, and your mind feeling overwhelmed with worry? This tense combination of symptoms can be a result of feeling anxious.

Coping Mechanisms for DepressionIf you’re dealing with clinical depression or experiencing sporadic depressive episodes, you may know the feeling of hopelessness, fatigue, and a lack of motivation all too well. Aside from the emotional symptoms that can be present during depression, you may also feel certain physical side effects such as a change in sleeping or eating habits (Aselton, 2012). Let’s take a look at some ways we can help mitigate our symptoms of depression.

Coping Mechanisms for GriefGrief can be the result of several life changes, such as the loss of a loved one, divorce, moving from your home, or even graduating from school.

TED Talk: Finding Your Coping MechanismNeed some support in finding a coping mechanism that works for you? Try watching this TED Talk on coping mechanisms by Joseph Lewis: Quotes on Coping MechanismsLooking for words of encouragement to deal with life’s challenges? Here are some wise words that may offer you some perspective.

Articles Related to Coping MechanismsWant to learn more? Check out these articles:

Books Related to Coping MechanismsIf you’d like to keep learning more, here are a few books that you might be interested in.

Final Thoughts on Coping MechanismsJust like our individual life paths, the way we cope with stressors and challenges may all look different from person to person. We hope this article offered you insights into various methods of coping mechanisms, styles, and techniques for everyday stress, major life events, and dealing with your mental health. Finding a healthy coping strategy that works for you may take time, but we hope you recognize there is no one-size-fits-all approach to coping. And finally, please remember to be kind to yourself as you learn and add coping strategies to your wellness repertoire. Don't Forget to Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How toGrow Your Wellness Business Exponentially! References

| Are You a Therapist, Coach, or Wellness Entrepreneur? Grab Our Free eBook to Learn How to Grow Your Wellness Business Fast! Key Articles:

Content Packages:

|

Coping Mechanisms - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf

Emad B. Algorani; Vikas Gupta.

Author Information and Affiliations

Last Update: April 28, 2022.

Definition/Introduction

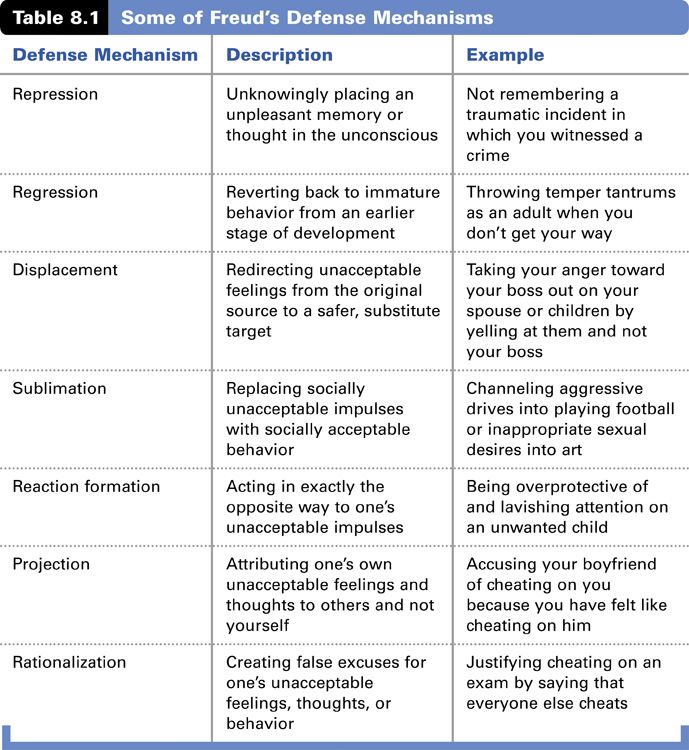

Coping is defined as the thoughts and behaviors mobilized to manage internal and external stressful situations.[1] It is a term used distinctively for conscious and voluntary mobilization of acts, different from 'defense mechanisms' that are subconscious or unconscious adaptive responses, both of which aim to reduce or tolerate stress.[2]

When individuals are subjected to a stressor, the varying ways of dealing with it are termed 'coping styles,' which are a set of relatively stable traits that determine the individual's behavior in response to stress. These are consistent over time and across situations.[3] Generally, coping is divided into reactive coping (a reaction following the stressor) and proactive coping (aiming to neutralize future stressors). Proactive individuals excel in stable environments because they are more routinized, rigid, and are less reactive to stressors, while reactive individuals perform better in a more variable environment.[4]

These are consistent over time and across situations.[3] Generally, coping is divided into reactive coping (a reaction following the stressor) and proactive coping (aiming to neutralize future stressors). Proactive individuals excel in stable environments because they are more routinized, rigid, and are less reactive to stressors, while reactive individuals perform better in a more variable environment.[4]

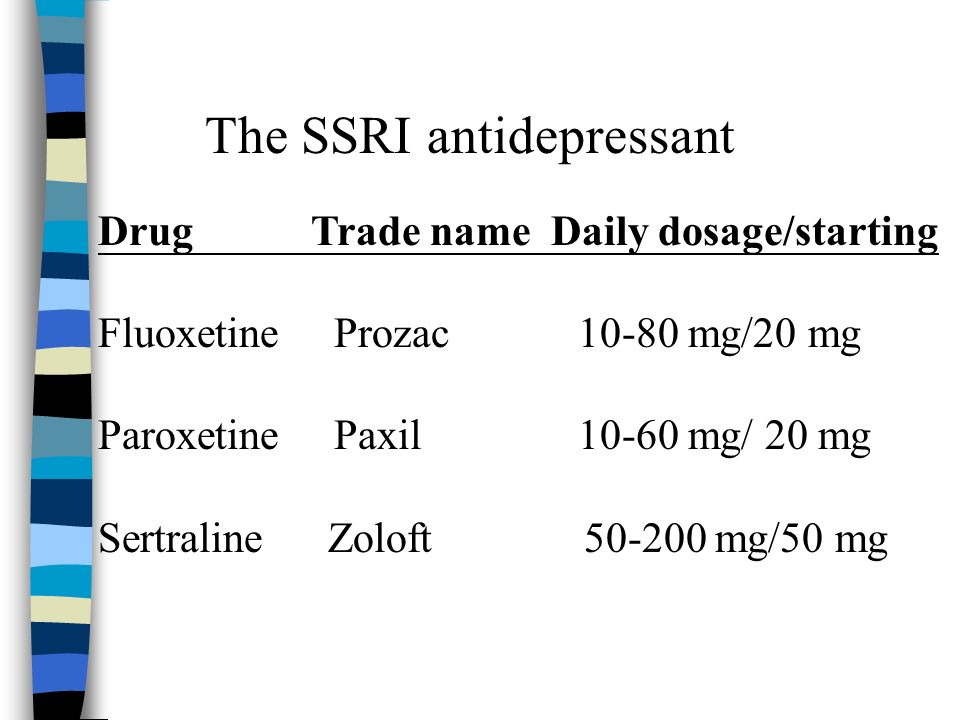

Coping scales measure the type of coping mechanism a person exhibits. The most commonly used scales are COPE (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced), Ways of Coping Questionnaire, Coping Strategies Questionnaire, Coping Inventory for Stressful Situations, Religious-COPE, and Coping Response Inventory.[5]

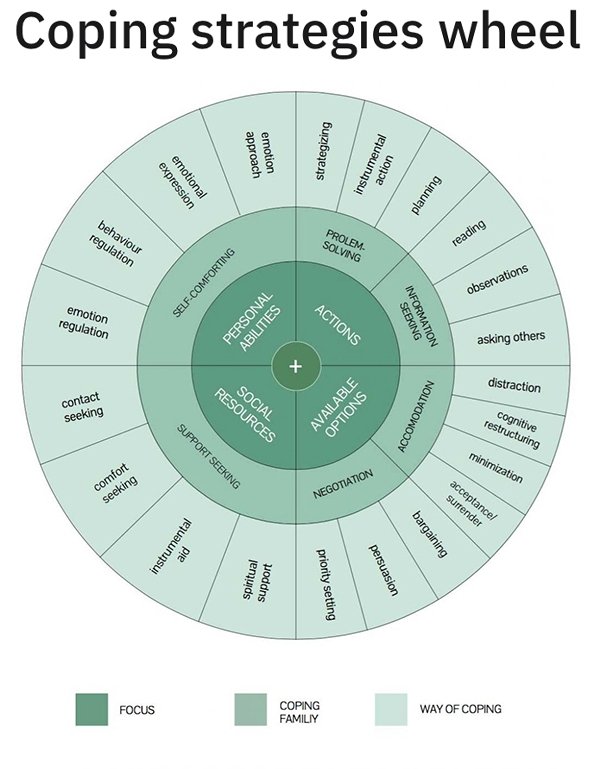

Coping is generally categorized into four major categories which are[1]:

Problem-focused, which addresses the problem causing the distress: Examples of this style include active coping, planning, restraint coping, and suppression of competing activities.

Emotion-focused, which aims to reduce the negative emotions associated with the problem: Examples of this style include positive reframing, acceptance, turning to religion, and humor.

Meaning-focused, in which an individual uses cognitive strategies to derive and manage the meaning of the situation

Social coping (support-seeking) in which an individual reduces stress by seeking emotional or instrumental support from their community.

Many of the coping mechanisms prove useful in certain situations. Some studies suggest that a problem-focused approach can be the most beneficial; other studies have consistent data that some coping mechanisms are associated with worse outcomes.[6][1] Maladaptive coping refers to coping mechanisms that are associated with poor mental health outcomes and higher levels of psychopathology symptoms. These include disengagement, avoidance, and emotional suppression.[7]

The physiology behind different coping styles is related to the serotonergic and dopaminergic input of the medial prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens. [4] The neuropeptides vasopressin and oxytocin also have an important implication relative to coping styles. On the other hand, neuroendocrinology involving the level of activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, corticosteroids, and plasma catecholamines were unlikely to have a direct causal relationship with an individual's coping style.[8]

[4] The neuropeptides vasopressin and oxytocin also have an important implication relative to coping styles. On the other hand, neuroendocrinology involving the level of activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, corticosteroids, and plasma catecholamines were unlikely to have a direct causal relationship with an individual's coping style.[8]

Issues of Concern

Patients using maladaptive coping mechanisms are more likely to engage in health-risk behaviors than those with appropriate mechanisms. They are also more non-adherent and more likely to use cigarettes or alcohol.[9]

Coping influences patients' compliance to therapy and the course of the disease by lifestyle changes. In disorders where non-medicinal treatment plays a role in the progression, coping mechanisms are important in determining the severity of such conditions. Coping styles may be helpful in patients' educational programs or psychotherapy, and paying attention to them could contribute to the prevention of sequelae. [10][11]

[10][11]

The importance of coping styles does not only affect the patients alone but also their physicians and nurses. Healthcare workers are more likely to choose a problem-oriented coping mechanism while the tendency to choose avoidance decreases with age and employment duration. The incidence of burnout syndrome decreases with the use of problem-oriented coping mechanisms, social integration, and the use of religion.[12][13]

Clinical Significance

Understanding coping mechanisms is a cornerstone in choosing the best approach to the patient to build an effective doctor-patient relationship. The need to monitor the patient's level of distress and coping mechanisms arise because patients who adopt maladaptive mechanisms are more likely to perceive their doctors as being disengaged and less supportive. This perception is clinically significant because about one out of four cancer patients use a maladaptive coping mechanism.[14]

The relation between maladaptive coping mechanisms and numerous disorders has been established. Psychiatric disorders such as PTSD, anxiety, and major depression, and somatic symptoms were all correlated with coping styles related to avoidance.[15] This scenario holds for other disorders such as hypertension and heart diseases, where maladaptive coping strategies were used by patients who had more severe symptoms.[16]

Psychiatric disorders such as PTSD, anxiety, and major depression, and somatic symptoms were all correlated with coping styles related to avoidance.[15] This scenario holds for other disorders such as hypertension and heart diseases, where maladaptive coping strategies were used by patients who had more severe symptoms.[16]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Teaching patients and their caregivers appropriate coping skills can have a significant impact on the way they perceive their condition, the severity of the symptoms, and the psychological distress associated with it. In patients diagnosed with lung cancer, assertive communication was associated with less pain interference and psychological distress; coping skills effects extend to family caregivers who reported less psychological distress when practicing guided imagery. Other coping mechanisms as mindfulness might not be as beneficial in certain situations.[17] [Level 2]

Physicians, psychiatrists, physical therapists, nurses, and health educators share the role of educating patients to become more responsible for their health. Interprofessional involvement can help patients cope better with the symptoms of their illnesses. Coping skills training programs didn't prove to be effective in reducing pain severity among knee osteoarthritis patients. They did not confer pain or functional benefit beyond that with surgical and postoperative care, but combining both physical exercises and coping skills training with treatment had a more significant improvement.[18][19][20] [Level 1, Level 2]

Interprofessional involvement can help patients cope better with the symptoms of their illnesses. Coping skills training programs didn't prove to be effective in reducing pain severity among knee osteoarthritis patients. They did not confer pain or functional benefit beyond that with surgical and postoperative care, but combining both physical exercises and coping skills training with treatment had a more significant improvement.[18][19][20] [Level 1, Level 2]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

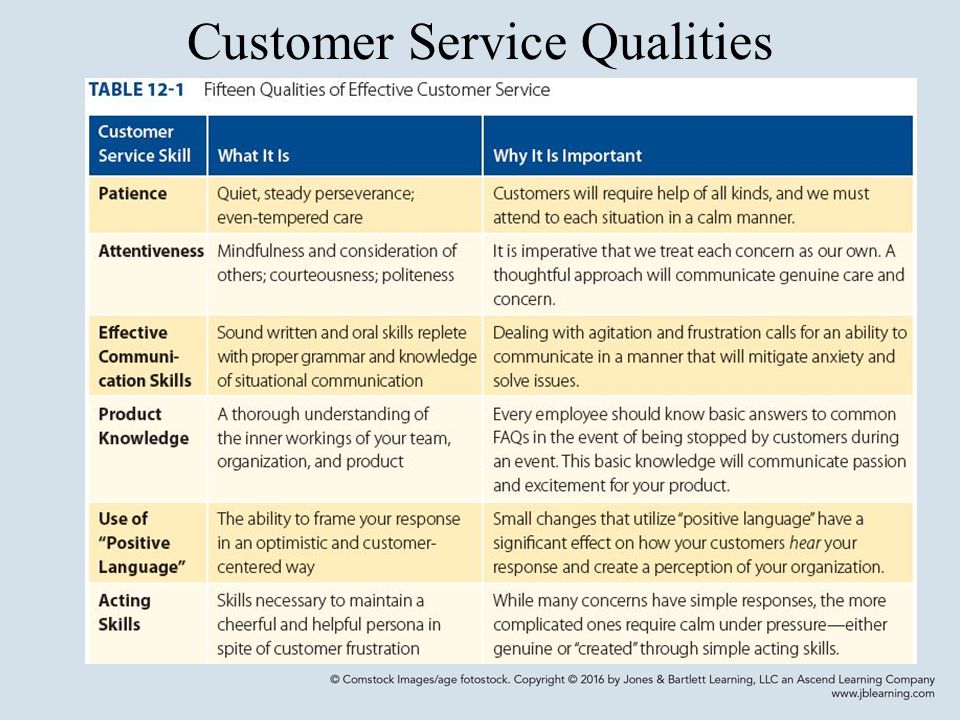

Understanding the coping styles is central to support the patient's coping efforts. Talking with the medical staff to seek information and social support was the most popular coping strategy in anxious surgical patients. Monitoring patients' coping strategies using various coping scales (e.g., COPE, Ways of Coping Questionnaire, Coping Strategies Questionnaire) can help in evaluating the patient's psychological status and continued improvement.[21]

Review Questions

Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

Comment on this article.

References

- 1.

Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:745-74. [PubMed: 14744233]

- 2.

Venner M. [Adjustment, coping and defense mechanisms--deciding factors in the therapeutic process]. Z Gesamte Inn Med. 1988 Jan 15;43(2):40-3. [PubMed: 3358307]

- 3.

de Boer SF, Buwalda B, Koolhaas JM. Untangling the neurobiology of coping styles in rodents: Towards neural mechanisms underlying individual differences in disease susceptibility. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Mar;74(Pt B):401-422. [PubMed: 27402554]

- 4.

Coppens CM, de Boer SF, Koolhaas JM. Coping styles and behavioural flexibility: towards underlying mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010 Dec 27;365(1560):4021-8. [PMC free article: PMC2992750] [PubMed: 21078654]

- 5.

Kato T. Frequently Used Coping Scales: A Meta-Analysis. Stress Health.

2015 Oct;31(4):315-23. [PubMed: 24338955]

2015 Oct;31(4):315-23. [PubMed: 24338955]- 6.

Stoeber J, Janssen DP. Perfectionism and coping with daily failures: positive reframing helps achieve satisfaction at the end of the day. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011 Oct;24(5):477-97. [PubMed: 21424944]

- 7.

Compas BE, Jaser SS, Bettis AH, Watson KH, Gruhn MA, Dunbar JP, Williams E, Thigpen JC. Coping, emotion regulation, and psychopathology in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis and narrative review. Psychol Bull. 2017 Sep;143(9):939-991. [PMC free article: PMC7310319] [PubMed: 28616996]

- 8.

Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Coppens CM, Buwalda B. Neuroendocrinology of coping styles: towards understanding the biology of individual variation. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010 Jul;31(3):307-21. [PubMed: 20382177]

- 9.

Sánchez M, Rice E, Stein J, Milburn NG, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Acculturation, coping styles, and health risk behaviors among HIV positive Latinas. AIDS Behav.

2010 Apr;14(2):401-9. [PMC free article: PMC2835805] [PubMed: 19847637]

2010 Apr;14(2):401-9. [PMC free article: PMC2835805] [PubMed: 19847637]- 10.

Cattelaens K, Schewe S, Schuch F. [Treat to target-participation of the patient]. Z Rheumatol. 2019 Jun;78(5):416-421. [PubMed: 30937529]

- 11.

Rydlewska A, Krzysztofik J, Libergal J, Rybak A, Rydlewski J, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P, Jankowska EA. [Coping styles in patients with systolic heart failure]. Przegl Lek. 2013;70(1):15-8. [PubMed: 23789299]

- 12.

Kwarta P, Pietrzak J, Miśkowiec D, Stelmach I, Górski P, Kuna P, Antczak A, Pietras T. Personality traits and styles of coping with stress in physicians. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2016 May;40(239):301-7. [PubMed: 27234861]

- 13.

Ilić IM, Arandjelović MŽ, Jovanović JM, Nešić MM. Relationships of work-related psychosocial risks, stress, individual factors and burnout - Questionnaire survey among emergency physicians and nurses. Med Pr. 2017 Mar 24;68(2):167-178. [PubMed: 28345677]

- 14.

Meggiolaro E, Berardi MA, Andritsch E, Nanni MG, Sirgo A, Samorì E, Farkas C, Ruffilli F, Caruso R, Bellé M, Juan Linares E, de Padova S, Grassi L. Cancer patients' emotional distress, coping styles and perception of doctor-patient interaction in European cancer settings. Palliat Support Care. 2016 Jun;14(3):204-11. [PubMed: 26155817]

- 15.

Santarnecchi E, Sprugnoli G, Tatti E, Mencarelli L, Neri F, Momi D, Di Lorenzo G, Pascual-Leone A, Rossi S, Rossi A. Brain functional connectivity correlates of coping styles. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2018 Jun;18(3):495-508. [PubMed: 29572771]

- 16.

Casagrande M, Boncompagni I, Mingarelli A, Favieri F, Forte G, Germanò R, Germanò G, Guarino A. Coping styles in individuals with hypertension of varying severity. Stress Health. 2019 Oct;35(4):560-568. [PubMed: 31397061]

- 17.

Winger JG, Rand KL, Hanna N, Jalal SI, Einhorn LH, Birdas TJ, Ceppa DP, Kesler KA, Champion VL, Mosher CE.

Coping Skills Practice and Symptom Change: A Secondary Analysis of a Pilot Telephone Symptom Management Intervention for Lung Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 May;55(5):1341-1349.e4. [PMC free article: PMC5899922] [PubMed: 29366911]

Coping Skills Practice and Symptom Change: A Secondary Analysis of a Pilot Telephone Symptom Management Intervention for Lung Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018 May;55(5):1341-1349.e4. [PMC free article: PMC5899922] [PubMed: 29366911]- 18.

Allen KD, Somers TJ, Campbell LC, Arbeeva L, Coffman CJ, Cené CW, Oddone EZ, Keefe FJ. Pain coping skills training for African Americans with osteoarthritis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2019 Jun;160(6):1297-1307. [PMC free article: PMC6719680] [PubMed: 30913165]

- 19.

Riddle DL, Keefe FJ, Ang DC, Slover J, Jensen MP, Bair MJ, Kroenke K, Perera RA, Reed SD, McKee D, Dumenci L. Pain Coping Skills Training for Patients Who Catastrophize About Pain Prior to Knee Arthroplasty: A Multisite Randomized Clinical Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Feb 06;101(3):218-227. [PMC free article: PMC6791506] [PubMed: 30730481]

- 20.

Bennell KL, Ahamed Y, Jull G, Bryant C, Hunt MA, Forbes AB, Kasza J, Akram M, Metcalf B, Harris A, Egerton T, Kenardy JA, Nicholas MK, Keefe FJ.

Physical Therapist-Delivered Pain Coping Skills Training and Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 May;68(5):590-602. [PubMed: 26417720]

Physical Therapist-Delivered Pain Coping Skills Training and Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 May;68(5):590-602. [PubMed: 26417720]- 21.

Aust H, Rüsch D, Schuster M, Sturm T, Brehm F, Nestoriuc Y. Coping strategies in anxious surgical patients. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016 Jul 12;16:250. [PMC free article: PMC4941033] [PubMed: 27406264]

Psychological violence and ways of coping

Zyuzkina Anastasia Andreevna, psychologist of the health care institution "City Clinical Psychiatric Dispensary"

Often domestic violence against women and children is not perceived as an act of violence.

The topic of psychological abuse is broad, this issue is relevant not only in the field of the family system, but also in the sphere of work.

For example, in the scientific literature, psychological violence is called mobbing - the employer's disrespectful attitude towards employees in the context of labor relations. Situations where periodically (at least once a week) the employee is humiliated and harassed by the team or the manager, the purpose of which is to dismiss the employee during the period of employment. Mobbing is manifested in the oppression of a long period of time and includes negative statements, unfounded criticism, social isolation of an employee, dissemination of deliberately false information about a person, and more.

Situations where periodically (at least once a week) the employee is humiliated and harassed by the team or the manager, the purpose of which is to dismiss the employee during the period of employment. Mobbing is manifested in the oppression of a long period of time and includes negative statements, unfounded criticism, social isolation of an employee, dissemination of deliberately false information about a person, and more.

Psychological consequences for the object of mobbing are so serious that social significance is perceived as traumatic and compared with murder, rape and robbery. Some people even think about suicide.

Most often, psychological abuse occurs in the family. The main victims of domestic violence are women and children. The consequences of psychological violence include sleep and appetite disorders, alcoholism, reckless committing of traumatic actions, a change in the nature of the individual.

Psychological violence is a form of influencing the emotions or psyche of a partner through threats, intimidation, insults, criticism, condemnation, etc. That is, a constant verbal negative impact on another person. More often this type of violence is subjected to wives from their husbands, much less often vice versa.

That is, a constant verbal negative impact on another person. More often this type of violence is subjected to wives from their husbands, much less often vice versa.

Psychological abuse can escalate into physical abuse.

Domestic violence also spreads in cohabitation as cohabitation. Most often it is a form of psychological abuse. Psychological abuse is on a par with physical abuse, since the personality is violated by suppressing self-esteem. Under such conditions, the person who is targeted by the negative impact does not assess the situation as dangerous and sometimes it is necessary to convince them that they have become precisely the victims. Beliefs are formed as if she herself is to blame, misunderstood, did not tolerate, did not prove, provoked. As a result, personal characteristics are formed: self-restraint, alienation, negativism, refusal to express one's own position.

Insults, violence, mistreatment in psychology is called abuse. The person who forces to do something, offends, forces to perform actions that are unpleasant to another person, respectively, is an abuser.

The reasons why one partner affects the psyche of another are varied, the most common: the need for self-realization and self-affirmation at the expense of the other, difficulties in the inability to express one's desires and thoughts, past experience, financial dependence on one's partner, the perception of violence as a norm in family behavior, propaganda of violence in the media / movies / video games, psychological deviations in the form of a psychological trauma.

With constant criticism, the self-esteem of the victim decreases to a certain level and self-confidence is shaky, in this state it is easier for the tyrant to impose his opinion and desired behavior. The victim in such a state of mind doubts the correctness of his actions, a feeling of insignificance and guilt is instilled. By psychologically influencing such a person, another model of life is laid, the position of a tyrant is adopted and control is exercised on his part.

There are many signs of psychological violence and a combination of signs is used to determine it, and not each factor individually:

- criticism - a rough assessment of shortcomings, comments about appearance, intelligence, taste preferences, such criticism may be followed by insults.

- Humiliation - insults, rough treatment.

- Accusation - conviction of guilt, for example, in family failures and shifting responsibility for everything that happens.

- Despotism - commanding tone in communication, orders and instructions instead of requests.

- Intimidation - Threats of physical violence against the victim and their loved ones, limiting prohibitions on contact with children and threats from the tyrant to commit suicide.

- Prohibition to communicate with relatives, friends, colleagues, deprivation of means of communication.

- Prohibited from visiting places outside the home and obtaining permission from a partner to leave the house.

- Permanent presence, partner rarely leaves alone.

- Monitoring behavior and communication outside the home, checking private messages, checking call lists, checking email, installing software, hidden or open surveillance (video surveillance).

Emotional abuse also includes jealousy, which manifests itself in constant accusations of adultery.

A psychological abuser has such qualities as: disrespectful attitude towards a partner and his life principles; the imposition of help that was not asked for, generosity that puts in an awkward position; total control; jealousy; threatening behavior; the presence of double standards “I can, but you can’t”; life credo "a man (woman) is never guilty of anything."

There are several types of psychological violence. Gaslighting is one of the most severe forms of psychological abuse. The gaslighter denies their partner or child adequateness using the phrases “it seemed to you”, “it didn’t happen”, “you just don’t understand it”. The victim is instilled that the perception of the environment is erroneous, therefore, the victim is convinced that she is going crazy. Neglect - ignoring any needs, arguing that a person does not need it, deliberate negligence. Sometimes the abuser pushes his partner to plastic surgery, refuses to deal with everyday life and children. In this situation, it is best to isolate yourself from the abuser. Visholding - refusal to discuss an exciting topic. Emotional blackmail - ignoring any action of the victim, emotional coldness, silence, blackmail with personal information. The purpose of such behavior is the subordination of another person, deprivation of one's own will, and only by limiting communication can one protect himself from this. Ignoring - emotional withdrawal. Isolation - prohibition of communication with everyone except the abuser himself, so the request for help is difficult to carry out. Control - tight control over any actions of the partner. Criticism - pointing out shortcomings and miscalculations, that in front of other people it looks like ridicule. The purpose of such behavior is to form an inferiority complex, after such an impact it is difficult to recover from such a relationship, faith in oneself, partnership is lost.

In this situation, it is best to isolate yourself from the abuser. Visholding - refusal to discuss an exciting topic. Emotional blackmail - ignoring any action of the victim, emotional coldness, silence, blackmail with personal information. The purpose of such behavior is the subordination of another person, deprivation of one's own will, and only by limiting communication can one protect himself from this. Ignoring - emotional withdrawal. Isolation - prohibition of communication with everyone except the abuser himself, so the request for help is difficult to carry out. Control - tight control over any actions of the partner. Criticism - pointing out shortcomings and miscalculations, that in front of other people it looks like ridicule. The purpose of such behavior is to form an inferiority complex, after such an impact it is difficult to recover from such a relationship, faith in oneself, partnership is lost.

It is best for the victim to get out of the situation of violence (even run away, disappear from view). Victims of psychological abuse cannot avoid mental problems. Such people are in a state of psychological trauma and experience anxiety, fear, may become depressed, and suicidal attempts are not excluded. There is also emotional dependence, neglect of one's needs, various addictions may arise, for example, alcohol or drugs.

According to studies, in those families where various types of violence (physical, psychological) are used, signs of a delay in the physical and neuropsychic development of children are noticed.

In each specific case of violence, a psychological consultation is required.

It is important to take responsibility for your life, set your own goals, learn to listen to yourself and your feelings, stop negative influences and report what is unpleasant, not tolerate when something causes negative feelings.

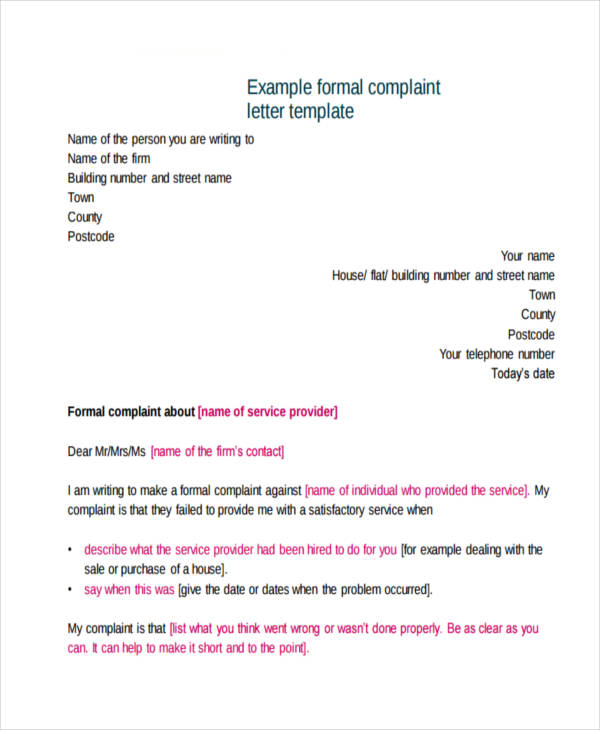

In difficult social, economic and psychological situations, you should contact crisis centers to receive the necessary assistance.

For psychological support, you can contact the helpline, where they will listen, support and determine the type of assistance.

The importance of evaluating clients' coping strategies - Practical Health Psychology

Nadia Garnefsky, Vivian Kraay, Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Leiden, The Netherlands

“Rob just found out he has HIV (negative event). He thinks he is the one to blame (self-blame) and avoids meeting friends (avoidance). This situation made him sad. When Rob is at home, he can't stop thinking about his feelings (rumination) and considers what happened to be a complete disaster (catastrophizing). Because he is sad, he has little energy. As a result, he avoids communication even more, which makes him even sadder. Thus, Rob is drawn into a vicious circle."

People experience a range of strong emotions in response to negative life events. To cope with these emotions, people can use a variety of cognitive and behavioral strategies. This process is called coping. Lazarus defined coping as an individual's efforts to cope with stress caused by harm, threat or challenge. In Rob's case, the negative event was the news of his positive HIV status. Many other stressful events can happen, from single events such as the death of a loved one, divorce, or job loss, to long-term events such as bullying, high workloads, and relationship problems. Thus, coping is applicable to all kinds of life stresses.

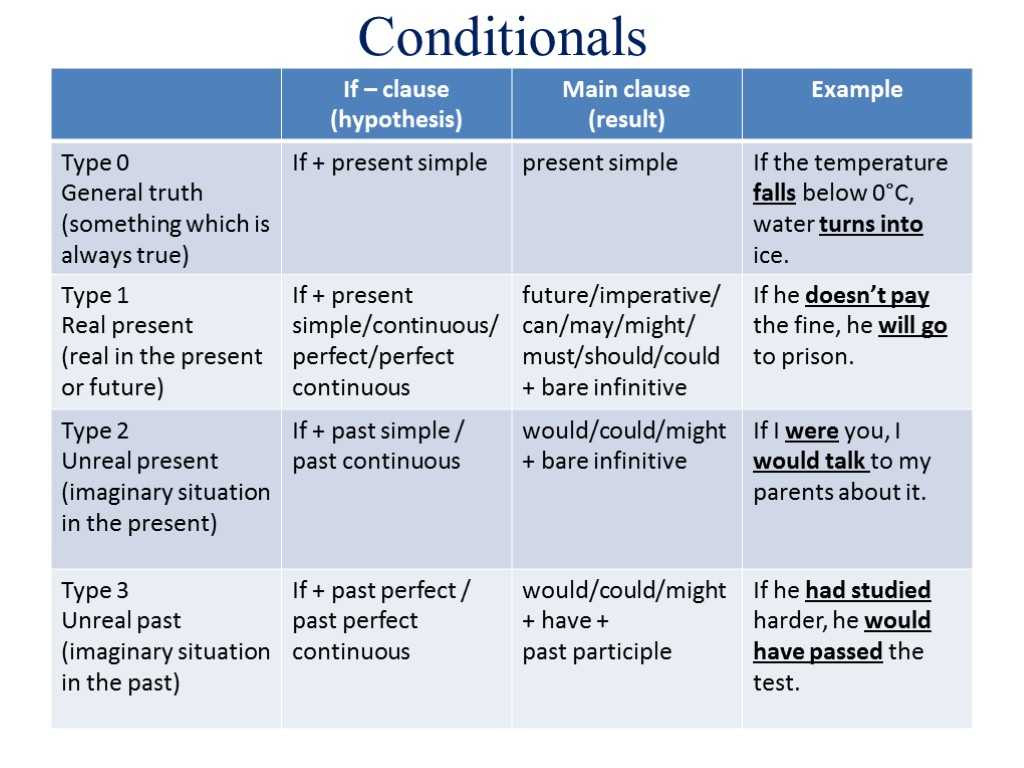

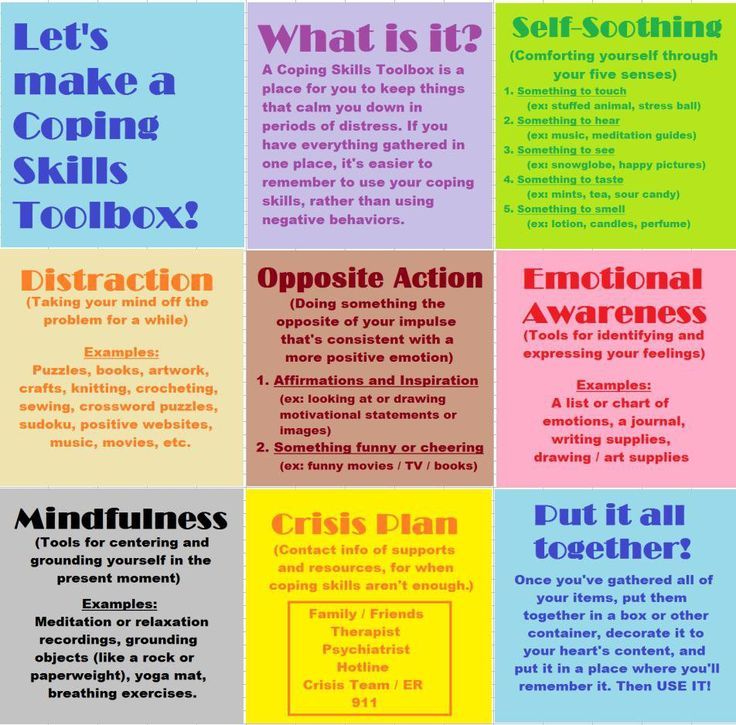

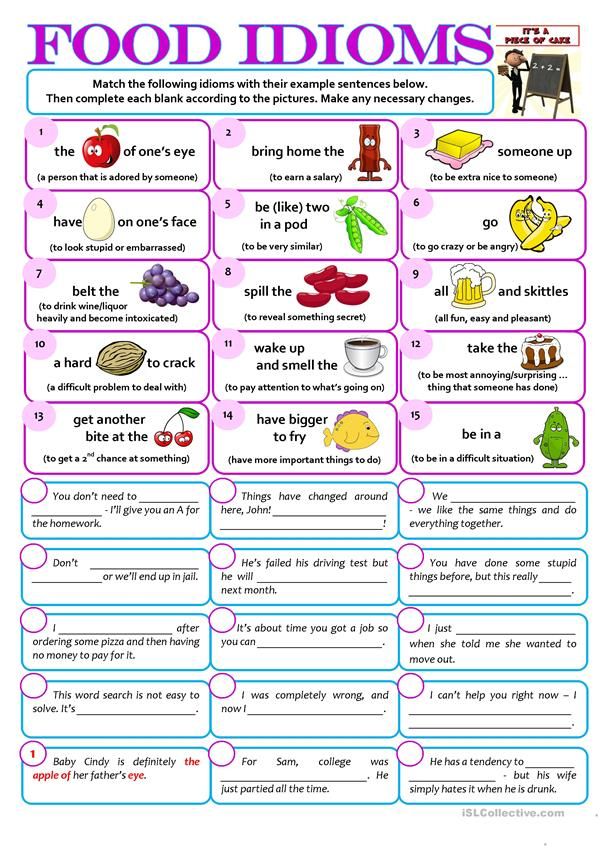

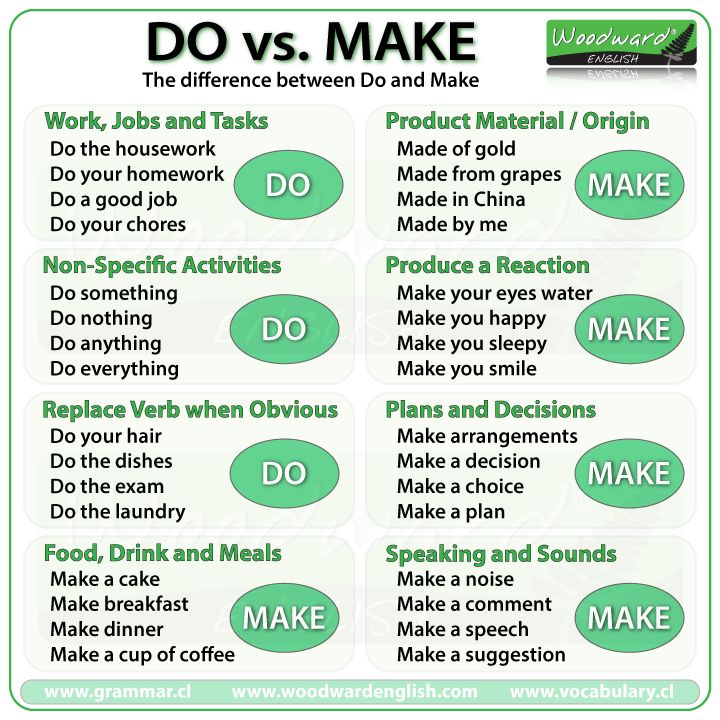

Coping strategies can be divided into cognitive (“what do you think”) and behavioral (“what do you do”). An example of a cognitive coping strategy is self-blame. People who use this coping strategy blame themselves for what they went through (Rob blamed himself for contracting HIV). Other examples of cognitive strategies are rumination and catastrophizing. Rumination is the repeated reflection on the emotions, thoughts, and feelings associated with a negative experience. Catastrophizing means focusing too much on the destructive aspects of what happened. Rob resorted to all these strategies. Other cognitive strategies are blaming others, accepting, refocusing on more pleasant things, planning your steps, re-evaluating or giving the event a positive value, and putting the event in perspective (in comparison to other, worse events). In total, 9cognitive coping strategies. An example of a behavioral coping strategy is avoidance - avoiding situations and social contacts, which was also observed in Rob. Other behavioral coping strategies include seeking distraction, taking action to cope with the experience, seeking social support, and ignoring—behaving as if nothing had happened. So, in total, 5 behavioral coping strategies are described.

To assess cognitive and behavioral coping strategies, 2 instruments were created and validated - the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) and the Behavioral Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (BERQ). CERQ has already been translated and validated in many languages, and BERQ is being actively translated.

Studies that have examined the role of cognitive and behavioral coping strategies using CERQ and BERQ have identified useful and less useful strategies. Among cognitive strategies, rumination, catastrophizing, and self-blame were found to be less useful than positive reappraisal, putting the situation into perspective, and refocusing on the positive. In terms of behavioral strategies, avoidance and ignorance are less helpful than distraction, action, and seeking social support. These are general conclusions; in a particular stressful situation, another can be observed.

Knowledge of the client's specific cognitive and behavioral coping strategies can help to understand the vicious circle of psychological problems and can suggest ways to change maladaptive patterns and build more adaptive ones.

“Rob has started therapy. The therapist assessed Rob's cognitive and behavioral coping strategies and found high scores for self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, and avoidance.

Typically, we utilize cognitive and behavioral approaches to cope (Burns & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991).

Typically, we utilize cognitive and behavioral approaches to cope (Burns & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991).  ” Forgiving yourself lets you shift the focus to your actions instead of ruminating on what happened.

” Forgiving yourself lets you shift the focus to your actions instead of ruminating on what happened. Let’s take a look at some of the primary types of coping mechanisms that may be helpful to incorporate into your own coping toolkit.

Let’s take a look at some of the primary types of coping mechanisms that may be helpful to incorporate into your own coping toolkit.

Similar to dealing with stressors, an avoidant coping style may start as harmless until the stressful situations keep adding on, leading to a backlog of emotions that still need to be dealt with.

Similar to dealing with stressors, an avoidant coping style may start as harmless until the stressful situations keep adding on, leading to a backlog of emotions that still need to be dealt with.  , 2021). Some healthy coping examples include:

, 2021). Some healthy coping examples include:

Regardless of whether you’re experiencing fear or worrying about an upcoming event, you can try out these tips that may help you cope with anxious thoughts (Savitsky et al., 2020).

Regardless of whether you’re experiencing fear or worrying about an upcoming event, you can try out these tips that may help you cope with anxious thoughts (Savitsky et al., 2020).  Let’s say you receive the unfortunate news that you were laid off from your job. You have a family to provide for and bills to pay, and this sudden change is eliciting an anxious stress response. How will you make ends meet without an income? Perhaps you think to yourself, “This is the worst thing that could happen.” This is an example of catastrophic thinking. It’s incredibly easy for our minds to think of the worst-case scenario when a stressful situation like this appears. The practice of cognitive reframing (also called reappraisal), however, encourages you to challenge your thoughts and help restructure a negative thought into a more positive one. Instead, you may try telling yourself, “This situation sucks and it feels very difficult right now, but I know I will get through it.” Reframing harmful thoughts can help us then change behavior that can lead to a better outcome.

Let’s say you receive the unfortunate news that you were laid off from your job. You have a family to provide for and bills to pay, and this sudden change is eliciting an anxious stress response. How will you make ends meet without an income? Perhaps you think to yourself, “This is the worst thing that could happen.” This is an example of catastrophic thinking. It’s incredibly easy for our minds to think of the worst-case scenario when a stressful situation like this appears. The practice of cognitive reframing (also called reappraisal), however, encourages you to challenge your thoughts and help restructure a negative thought into a more positive one. Instead, you may try telling yourself, “This situation sucks and it feels very difficult right now, but I know I will get through it.” Reframing harmful thoughts can help us then change behavior that can lead to a better outcome.  Aromatherapy, in particular, appeals to our sense of smell. Research has shown that the same system that helps us regulate smell can also play a role in regulating emotions. One way to practice aromatherapy is to smell essential oils. For anxiety specifically, lavender oil is a popular scent for relieving anxious thoughts and reducing overall stress. Next time you’re out shopping, consider searching nearby for essential oils that seem to calm you.

Aromatherapy, in particular, appeals to our sense of smell. Research has shown that the same system that helps us regulate smell can also play a role in regulating emotions. One way to practice aromatherapy is to smell essential oils. For anxiety specifically, lavender oil is a popular scent for relieving anxious thoughts and reducing overall stress. Next time you’re out shopping, consider searching nearby for essential oils that seem to calm you.  Ever felt like laying in bed all day to deal with sadness you’re experiencing? I’ve been there too. Although sleeping under a warm blanket, with loads of junk food and a fully loaded Netflix queue next to me was my go-to depression coping strategy, I quickly felt even more miserable. While indulging in junk food and binge-watching is a fun activity from time to time, too much of it can point to an unhealthy and avoidant coping style. Instead, you may find it helpful for you, in the long run, to stick to a daily routine. Whether it includes a weekly cleaning schedule, a daily self-care routine, or even just meal-prepping your food, having a regular routine can help balance your moods.

Ever felt like laying in bed all day to deal with sadness you’re experiencing? I’ve been there too. Although sleeping under a warm blanket, with loads of junk food and a fully loaded Netflix queue next to me was my go-to depression coping strategy, I quickly felt even more miserable. While indulging in junk food and binge-watching is a fun activity from time to time, too much of it can point to an unhealthy and avoidant coping style. Instead, you may find it helpful for you, in the long run, to stick to a daily routine. Whether it includes a weekly cleaning schedule, a daily self-care routine, or even just meal-prepping your food, having a regular routine can help balance your moods.  Exercise helps release endorphins, which are “happiness hormones” that help with lifting moods.

Exercise helps release endorphins, which are “happiness hormones” that help with lifting moods.  Grief is our inherent response to a loss of some kind and healing from loss is not a linear process (Root & Exline, 2014). As you go through the highs and lows of your grief process, you may want to be mindful of some of these coping mechanisms.

Grief is our inherent response to a loss of some kind and healing from loss is not a linear process (Root & Exline, 2014). As you go through the highs and lows of your grief process, you may want to be mindful of some of these coping mechanisms.

B., & Gupta, V. (2021). Coping mechanisms. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

B., & Gupta, V. (2021). Coping mechanisms. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.  H. (1987). Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. Journal of personality and social psychology, 52(5), 946.

H. (1987). Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. Journal of personality and social psychology, 52(5), 946.  ..

..