People think im autistic

51 reasons why I know I’m autistic | by Ashlea McKay

A cluster of water-coloured umbrellas viewed from underneath as droplets of colour fall away like rain.This is not an original idea by any stretch of the imagination.

There are several lists just like this one floating around online and having read quite a few of them over the last two and a half years, I felt inspired to create one of my own. While my late diagnosis at the age of 29 in April 2016 turned my world upside down, it also explained a lot.

I’ve pulled together a list of everything that makes me, me.

When viewed in isolation, any one of these things might seem like something that might apply to anyone — autistic or not — but I want you to keep in mind that the overall collection is just as relevant as its individual pieces. Don’t be someone who mistakenly believes that everyone is on the spectrum because that just isn’t true. It’s also quite marginalising and diminishes the validity of experiences had by autistic people.

Instead, I’d like you to view this as a celebration of a different brain on a page. The good, the exceptional, the challenging and the downright depressing. It’s all there and it’s all me.

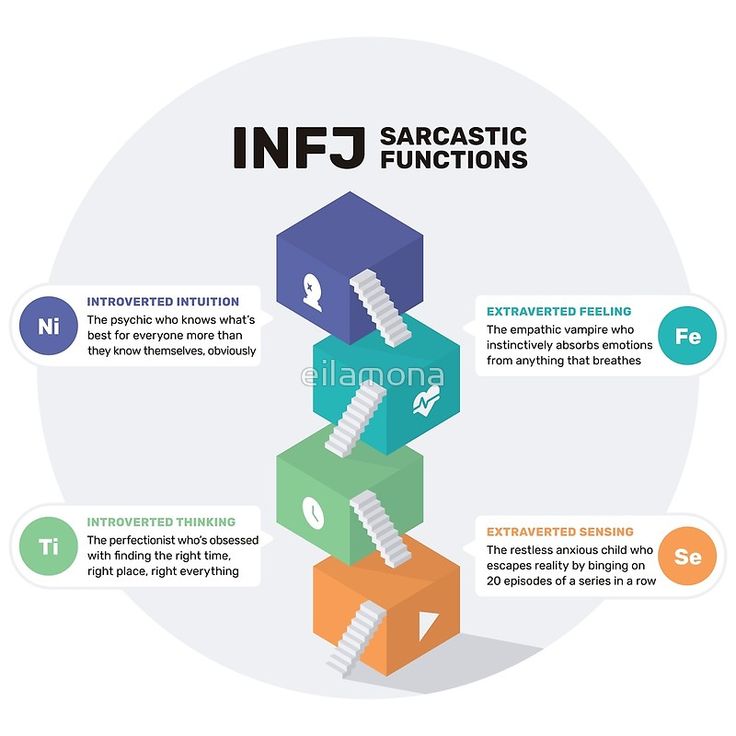

1. I don’t always know when someone is being sarcastic. Don’t invite that person to the meeting? OK, I won’t. Oops.

2. And on that note, it once took me 3 months to understand a dad joke.

3. The taste of mayonnaise and all mayonnaise based sauces makes me feel sick but I’m not allergic to it. This can be quite a challenging thing to explain when eating out and it’s not always respected.

4. A crowded shopping centre is my idea of hell. Bright lights, loud sounds, crowds and plenty of moments of unexpected and unpredictable human interaction. I do 95% of my shopping online and it all gets sent to a PO box that my husband checks during his lunch break. If an online store doesn’t deliver to PO boxes, I won’t shop with them.

5. I’ve never understood the concept of saying “Good Morning” to people the first time you see them in a day. I hate mornings. Also don’t understand why the time of day is part of a greeting.

I hate mornings. Also don’t understand why the time of day is part of a greeting.

6. My large shoe collection has a carefully considered taxonomy. They’re grouped by shoe type and care needs e.g., smooth leather shoes are in one group while glitter coated shoes are in another. Extra special shoes like those I purchase from Irregular Choice all remain in their original boxes.

7. I can’t always tell when someone is making fun of me. Someone once gave me a present as a joke and I actually really liked the gift and felt so happy that someone had been so thoughtful.

8. I really struggle to read facial expressions. I find that if I haven’t known the person for several years, I have to ask what’s going on behind it.

9. I’m terrible at remembering to stay in touch with people. It’s not because I don’t care about them, it just doesn’t naturally occur to me that I should actively remain in contact once my life moves on from them or where I see them the most.

10. Forming long term relationships (all types) can be really hard. More often than not, people tend to tire of my differences and leave me behind. It is starting to happen less and less — maybe I’ve just finally found the right people.

More often than not, people tend to tire of my differences and leave me behind. It is starting to happen less and less — maybe I’ve just finally found the right people.

11. My facial expressions don’t always match what’s going on inside. Someone once suggested I collaborate with others on an article and thought my facial expression meant I didn’t want to do it when really I was unpacking the problem of where the hell I was going to find these people and what to do if they said no. I’m constantly thinking 20 steps ahead and reviewing every possible pathway.

12. I don’t naturally read between the lines or recognise when to ‘take a hint’. For example, if I ask a question and someone doesn’t answer as their way of saying it’s a stupid question/they don’t agree/something else, I’ll just keep asking until they engage with me.

13. Certain textures have a calming effect on me and make me feel happy. I love those squishy things that seem to be having quite a moment — I almost lost my mind when I found giant ones at the shops the other night!

14. I freeze up and struggle to answer questions when approached by strangers in public. I’ve had several people (men mostly) accuse me of being dramatic (in much more colourful language) when I’ve reacted to their sudden intrusion into my heavily focused mind. In that moment, I’m don’t view them as a threat — I’m just startled.

I freeze up and struggle to answer questions when approached by strangers in public. I’ve had several people (men mostly) accuse me of being dramatic (in much more colourful language) when I’ve reacted to their sudden intrusion into my heavily focused mind. In that moment, I’m don’t view them as a threat — I’m just startled.

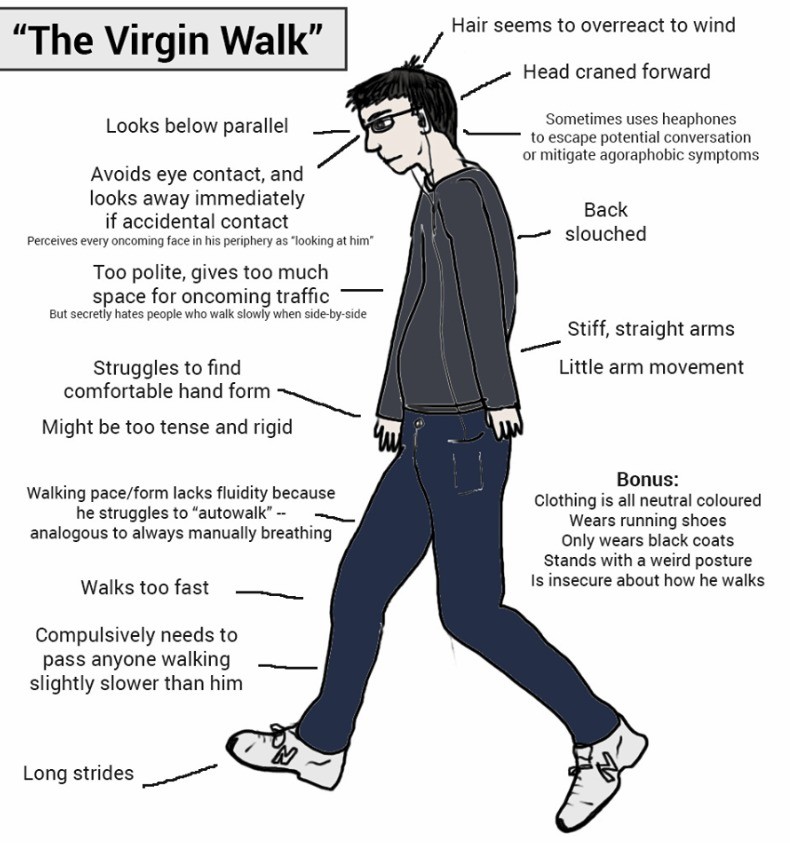

15. I don’t instinctively know the difference between left and right. I make shapes with my thumbs and forefingers to figure out which one to say when I’m giving someone directions.

16. I never know when it’s my turn to talk in a conversation. I always miss the ‘window’ and tend to interrupt a lot. Problem is if I don’t pipe up when I have that thought, I’ll most likely forget it by the time the other person stops speaking. Given enough time with specific individuals, we’ll both eventually fall into a conversation rhythm but that person has to be willing to meet me halfway and balance their irritations with my disability.

17. Small talk makes no sense to me. I don’t know why people ask how you are unless they truly want to know. I learned a long time ago that unless that person is a friend or family member they don’t want the truth. I’ve developed a default response for everyone else, but sometimes I get caught in a repeating autopilot loop of “I’m good thanks, how are you?” and lose track of what’s going on.

I don’t know why people ask how you are unless they truly want to know. I learned a long time ago that unless that person is a friend or family member they don’t want the truth. I’ve developed a default response for everyone else, but sometimes I get caught in a repeating autopilot loop of “I’m good thanks, how are you?” and lose track of what’s going on.

18. I’m really bad at remembering faces. Three years ago a conference I introduced myself to the same person four times in the space of a single day. We’re still friends — it’s OK.

19. I find large social gatherings (like conferences) to be really mentally draining. It takes a lot of work for me to constantly interact with strangers on that scale and for that long. I tend to disappear on walks at lunch or stick with people I know for periods of time so I can just be myself for a little while.

20. I love language. I’m good at applying it, learning it, and confusing the crap out of other people by the words or phrases I use.

21. I have a very hard time following unwritten social rules. I don’t understand them and I don’t instinctively apply them. I eat my dinner as soon as it arrives andI don’t instantly offer to remove my shoes on the rare occasions that I visit other people’s homes.

22. I have no problem going against the grain and doing my own thing. I read somewhere the other day that human beings are hardwired to please others as a survival mechanism but I seem to have a lesser degree of it. I won’t simply go along with something I don’t want to do or don’t believe is right just because the rest of the group is/wants to.

23. I don’t suck up to authority figures. I treat people equally and hold everyone to the same ethical standards. I don’t care who you are. I’m not that easily impressed. I value ideas and impact — not titles.

24. I never know what to with my arms when standing around out in public. They’re just kind of there and I don’t know where to put them. I’ve started wearing cross-body bags so I can just hold the strap or adjuster buckle whenever I get stuck.

25. I never make assumptions which can be challenging when receiving or giving instructions. I need full details and context — even the stuff that seems super obvious.

26. I love booking my cinema tickets online and choosing my seat. It helps me to predict that experience better and makes me feel a lot calmer. And if I happen to find someone in my seat, I will tell them to move because I’m not going to be someone who then goes and sits in someone else’s seat.

27. I really love my alone time. I like withdrawing from the world and recharging. I remember telling a friend one time that I was unwell over the weekend and he said “Oh it’s a shame it ruined your Saturday night!”. It depends what you think an ideal ‘Saturday night is’. Mine is my favourite takeaway and binge watching television at home in a comfy chair.

28. I don’t always know what to do when people around me are having a hard time. I care about them, but I struggle to understand how to put that feeling into action and help them in a meaningful way.

29. I research restaurant menus pretty heavily before choosing where to eat. I need to know exactly what to expect and if there are enough mayonnaise-free options.

30. Emotionally charged stories in film or television make me cry — a lot. I often find myself connecting with these characters on quite a deep level — even more so if it was based on a true story.

31. I love musical theatre. Yes, it’s loud and bright, but in the right way. It’s a chance for me to get completely lost in another world and I always sit in the front row. If I can’t get the front row, I won’t go. I saw Heathers: The Musical last month and the stage was at floor level. I was in the dead (pun intended) centre of the front row and it was so magical being that close to the story.

32. A knock at the door can ruin my entire day. It’s unpredictable, almost always unexpected, and it’s loud. That sound rattles me to my core and depending on how loud it was and how many times it happened, it can take several hours for me to regain my focus.

33. I can’t watch fictional depictions of autistic people in television and film without shaking and crying uncontrollably. It triggers something in me. There are some tv shows that walk a very fine line in this regard. Sometimes just the mention of an autistic person or just the word itself is enough to trigger that reaction in me.

34. Anything that breaks or changes my routine at the last minute can be quite jarring for me. I plan ahead and make detailed schedules and to-do lists and it can take me a moment or two to change my focus and my plan. It’s not that I can’t do it, it just takes me a little longer and sometimes this is taken as me being unhelpful. Someone might ask me if I can do something for them and before I answer, I’ll often stop, run through my plan in my head and think about how I can rearrange my schedule before I respond. This can be viewed as hesitation. It’s not that I don’t want to help, it’s just that I first need to work out how I can help before I commit because I’d hate for them to be stuck with someone who can’t help them.

35. I really love colouring in. I was doing it long before it was cool and I do it everyday.

36. I’m good at dyeing my own hair in unnatural colours. A few years ago I dyed my platinum blonde, learned how to maintain the cool tone of it and dealt with my dark blonde regrowth by myself. It was a skill that I wanted to learn and through my determination and colouring in skills, I mastered it. I have a wonderfully supportive hairdresser who cheers me on every time I walk into the salon for my 8 week haircut.

37. Making and holding eye contact can be quite painful for me. I tend to look at people’s eyebrows, glasses and hair instead. If I’m meeting someone for the first time, I tend to look at the floor or at a space behind them. There’s only three people on this planet that I can hold eye contact with for more than 10 seconds, but even then I never make it beyond the 30 second mark before it hurts. One is my father, another is my husband of 5 years (we’ve together for 12 years in total) and the third is a really good friend who has had my back for almost 5 years now.

38. I have a very strong sense of justice. If I catch a whiff of wrongdoing or inequality I won’t stand by and watch it happen. I will speak out against it and I don’t care how unpopular it makes me. I’m not out for blood either. All I want is acknowledgment that it was wrong, an apology and clear evidence that steps are being taken to end or prevent it from happening again.

39. I’m good at solving puzzles and not because I am one — screw you and your puzzle piece logos! When my focus isn’t being trashed and I’m not being overwhelmed by my environment, I have strong problem solving skills and approaches that often differ from those around me. I’m able to look at things sideways, upside down and back to front in ways that other people might find strange but they’re almost always delighted when I crack it! I love games like The Room and solving sudoku puzzles. I’ve never played an escape room before but I suspect I would love it.

40. I fidget a lot. My hands are constantly moving and seeking out textured surfaces to touch. It’s involuntary and it’s actually called ‘stimming’ which is a mashup term used to describe self-stimulation. It’s my brain’s way of calming me down as I move through a world that is sensorily overwhelming. I was at a restaurant last month and someone put a pile of coasters on the table for people to use and before I knew it, they were in my hands being shuffled like playing cards over and over again.

It’s involuntary and it’s actually called ‘stimming’ which is a mashup term used to describe self-stimulation. It’s my brain’s way of calming me down as I move through a world that is sensorily overwhelming. I was at a restaurant last month and someone put a pile of coasters on the table for people to use and before I knew it, they were in my hands being shuffled like playing cards over and over again.

41. When I see something I like or I’m really happy and just being myself, I’ll often skip in between my walking steps and my hands will flap slightly at my sides. I don’t even know I’m doing it.

42. I tend to notice really small details as I pass them. I read licence plates, I look at individual pieces of gravel and tiny details on trees etc. I get lost in every edge, corner, and shape.

43. I can focus my attention so deeply that the rest of the world just disappears. This is one of my favourite things to do because I can achieve so much. The downside is, if that focus gets broken, it can take hours to get it back.

44. Talking on the phone especially with people I don’t know can be really hard for me. Conversation is always a challenge, but doing it over the phone seems to amplify those difficulties. It’s even harder to tell when it’s my turn to talk, I’m never sure if I’m going to get a chance to say everything I need to say and it’s usually an unexpected conversation that I haven’t had time to prepare for. I tend to rehearse pieces of conversations beforehand to create structure and give me something to fall back on if I get stuck. I also screen my calls and if a recruiter that I’ve never met for example, sends me an email saying something like “What’s your phone number, I want to talk to you about a role etc”, I usually ignore it because I’ve learned that they’re not usually interested in learning about and accommodating my communication differences when they approach me like that.

45. I experience Executive Dysfunction (ED) which means it’s hard for me to get and keep my shit together. I find it difficult to get organised and manage my time on my own. I use lists and lots and lots of post-it notes to help me keep everything together, but sometimes I make mistakes. It’s not easy managing ED while also coping with sensory overload and the confusing minefield of social interaction. It’s not just one thing that I can conquer and everything will be OK — it’s a constant daily battle to exist among all these moving parts. Most people don’t/can’t understand this and this makes life even harder. Please be kinder to autistic people and stop tearing them down for their perceived failings — you have no idea how much effort it takes to leave the house each day.

I find it difficult to get organised and manage my time on my own. I use lists and lots and lots of post-it notes to help me keep everything together, but sometimes I make mistakes. It’s not easy managing ED while also coping with sensory overload and the confusing minefield of social interaction. It’s not just one thing that I can conquer and everything will be OK — it’s a constant daily battle to exist among all these moving parts. Most people don’t/can’t understand this and this makes life even harder. Please be kinder to autistic people and stop tearing them down for their perceived failings — you have no idea how much effort it takes to leave the house each day.

46. I can’t drive a car. I spent 15 years and thousands of dollars trying to learn and I just couldn’t do it. There’s just too much stimulus to take in and I can’t manage every aspect of driving while processing all that information. I found that if I was across my mirrors, I was speeding and if I was watching my speed, I missed a mirror or a head check or made a wrong turn. I renewed my Learner Licence seven times. About 3 months after my diagnosis, it was due for renewal again and I just cut it up. I no longer feel pressured to be something I’m not and I’m at peace with what I can and cannot do.

I renewed my Learner Licence seven times. About 3 months after my diagnosis, it was due for renewal again and I just cut it up. I no longer feel pressured to be something I’m not and I’m at peace with what I can and cannot do.

47. Boarding a plane makes me feel severely anxious. There’s a lot of people moving quickly in one small metal tube of a space and I always worry that I’ll take too long or I’ll get in someone’s way or worse, there will be some unexpected social interaction required that I haven’t planned for and I’ll be stuck in that moment. Where possible I try to talk to the airlines about being pre boarded — even if it’s just 2 minutes ahead of everyone else. This is never a problem when travelling internationally but domestically in Australia is a very different story. The two major airlines that operate domestic flights out of Canberra (my home city) require me to speak directly to the gate staff about pre boarding and I’ve found that this can be a really awful experience. They often think that because I can talk, travel alone and dress myself as well as I do, that I must be full of shit. I’ve been mocked and ridiculed by gate staff who haven’t believed me and I’ve been forced to flash my medicalert bracelet just to be taken seriously. I’ve actually stopped asking about pre boarding and have resigned myself to being one of those annoying people who loiter around the gate queue space as soon as the staff appear. Or I ‘accidentally’ queue up when they call for business class passengers to board.

They often think that because I can talk, travel alone and dress myself as well as I do, that I must be full of shit. I’ve been mocked and ridiculed by gate staff who haven’t believed me and I’ve been forced to flash my medicalert bracelet just to be taken seriously. I’ve actually stopped asking about pre boarding and have resigned myself to being one of those annoying people who loiter around the gate queue space as soon as the staff appear. Or I ‘accidentally’ queue up when they call for business class passengers to board.

48. Alcohol has a weird effect on my brain and it doesn’t take much. After one standard drink, I start feeling lightheaded and sleepy and after two standard drinks, I start feeling very dizzy and headachey. I’ve only ever been hungover once in my entire life and all it took was five standard drinks consumed across one 8 hour period.

49. I can’t wear stockings or tights for long periods of time. They feel fine when I first put them on but within an hour or so, they stretch and start moving. And then my other layers of clothing also start moving — but in different directions. Thanks to my sensory differences, this is almost impossible to tolerate. It’s incredibly distracting and very uncomfortable to the point that I cannot focus on anything else. I have found that fishnet stockings stay in place which is perfect because I love vintage styling, but otherwise I just wear black leggings as footless tights.

And then my other layers of clothing also start moving — but in different directions. Thanks to my sensory differences, this is almost impossible to tolerate. It’s incredibly distracting and very uncomfortable to the point that I cannot focus on anything else. I have found that fishnet stockings stay in place which is perfect because I love vintage styling, but otherwise I just wear black leggings as footless tights.

50. I experience regular bouts of insomnia. I find it very hard to switch my brain off at the end of the day — it just keeps on whirring. This makes falling asleep quite challenging and I can be left tossing and turning until well after 2am making it next to impossible to get up before 8am. It’s not always like this but when I’m caught in a pattern of sleeplessness like this, it can last for several months.

51. I’m not afraid to be seen. I don’t fear the consequences of speaking so openly about my disability, mental health issues or the abuse I’ve experienced at the hands of other people. I do despise the backlash and the hate mail I receive — but if I feel anything about that, it’s anger. Anger that will be channelled into putting a stop to each and every person who feels the need to bully and abuse autistic people. Authenticity comes easily to me.

I do despise the backlash and the hate mail I receive — but if I feel anything about that, it’s anger. Anger that will be channelled into putting a stop to each and every person who feels the need to bully and abuse autistic people. Authenticity comes easily to me.

This list is by no means comprehensive and I have no doubt I’ll be back in 6 months or so with a follow up piece of 51 more reasons why, but I really enjoyed writing it and hope you enjoyed reading it!

People Thinking I'm Autistic - Autism Spectrum Explained

9/28/2014

0 Comments

So, I was sitting with some of my friends yesterday and we were talking about autism, specifically how parents and siblings of autistic people are more likely to be on the spectrum, or at least broader autism phenotype, themselves. I made it clear that it was a safe space to ask questions, that there were no ‘dumb questions’ and anything and everything was on the table. And in that space one of them asked me a very thought provoking question:

And in that space one of them asked me a very thought provoking question:

Does it bother me that because I’m a sister of an Autistic person people are more likely to think I might be autistic, too?

I told her, no, it didn’t bother me, and we carried on with our conversation. But something about the question stuck with me and I kept thinking about it well into the night. When something sticks with me like that, that’s when I know it’s post-worthy, so I got my friend’s generous permission to share her question and my full response here.

You see, I realized that had you asked me this very same question two or three years ago, you would have received a very different answer.

Back then I would have told you that, you know, I wouldn’t really mind it so much if people thought I had Asperger’s. But, you know, Asperger’s and autism are really different, I would have told you. I would have assured you of the intelligence differences between the two groups, the communication differences, told you that people with Asperger’s and autistic people are as different as night and day. So there’s no way anyone could ever think that I was actually autistic, I would have said.

So there’s no way anyone could ever think that I was actually autistic, I would have said.

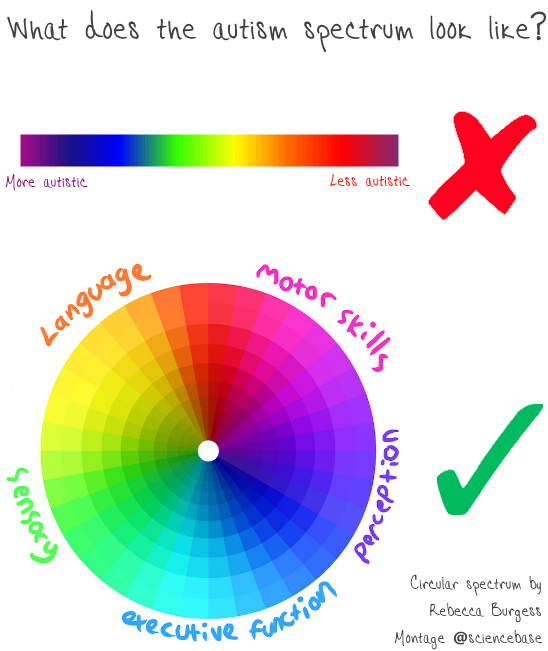

I would have been very, very wrong on a lot of counts. For one thing, the intelligence gap between Asperger’s and autism is over-hyped. There are no intelligence requirements to be diagnosed with one as opposed to the other, people with the diagnosis of classic autism can be as smart as or smarter than people with the previous diagnosis of Asperger’s, even by traditional IQ tests. And if though people with classic autism diagnoses do often test lower than people with Asperger’s diagnoses on traditional IQ tests, on other intelligence tests more suited to people on the spectrum that gap disappears.

At the time I would also have told you that people with Asperger’s are more ‘high functioning’ than people with classic autism. I would have also been wrong on that count (and wrong to use functioning labels in the first place). It turns out that people with those two once-separate diagnoses aren’t so different after all. In fact, the use of the two labels and false portrayals of how different they are (they aren’t) has led to artificial divides within the autism spectrum community. It’s also encouraged the “not like my child” attitude many non-autistic people have professed when reading the words of adults on the spectrum. “Oh, he has Asperger’s, what he’s saying doesn’t apply to my classically autistic child.” As you can see, the divides and misconceptions this creates are toxic. (For more on that, check out this post.)

In fact, the use of the two labels and false portrayals of how different they are (they aren’t) has led to artificial divides within the autism spectrum community. It’s also encouraged the “not like my child” attitude many non-autistic people have professed when reading the words of adults on the spectrum. “Oh, he has Asperger’s, what he’s saying doesn’t apply to my classically autistic child.” As you can see, the divides and misconceptions this creates are toxic. (For more on that, check out this post.)

So, now that we’ve established what kind of answer I would have given two years ago, and how very wrong it was, how would I respond now if someone asked me if I mind people thinking I’m autistic? The short answer, which I gave, is that I don’t mind. But here’s the longer answer.

I’d probably take it as a compliment. I think the reason people take the idea of being autistic as an insult is that, for one thing, they don’t know much about autism, and for another, they only know the deficits associated with autism. Me, though, I see strengths. Many of my favorite people to talk to are consistently on the autism spectrum, and that’s for a reason. For one thing, they know a whole lot about their areas of interest, and it is ridiculously fun to be around someone who can speak with passion and knowledge about a subject. It’s hard for me to hang around with friends on the spectrum and not learn something, and I love that. With my friends on the spectrum we can skip the gossip and head straight into the parts of conversation I most enjoy.

Me, though, I see strengths. Many of my favorite people to talk to are consistently on the autism spectrum, and that’s for a reason. For one thing, they know a whole lot about their areas of interest, and it is ridiculously fun to be around someone who can speak with passion and knowledge about a subject. It’s hard for me to hang around with friends on the spectrum and not learn something, and I love that. With my friends on the spectrum we can skip the gossip and head straight into the parts of conversation I most enjoy.

Things are also generally more straightforward. We’re more honest with each other, I think. In the absence of being able to read expressions well, you have to communicate more openly about your feelings, and I like that. I don’t want to perpetuate the myth that autistic people can’t lie about things, because that’s just not true, but with my friends on the spectrum we kind of skip the silly societal rules and communicate more directly, which is nice. Yeah, that’s a lot of what people see as a deficit, ‘poor social skills’, but it can have positives, too, and I generally far prefer it.

People I know who are on the spectrum tend to be people that I admire, so being compared with them? Yeah, that’s a compliment.

What’s more, if someone thought I was on the spectrum, I would no longer confidently reassure them that they’re wrong to think that. I’d probably tell them that I personally thought I was broader autism phenotype (BAP) with an anxiety disorder, rather than being diagnosably autistic, but that I’ve had enough autistic friends mention that they thought I was on the spectrum to admit that they may well be right, which is why I generally just give a lower bar for my neurology, not an upper. (I say I’m at least BAP.)

I think the absolute only thing I’d regret about someone thinking I was autistic would be the stigma and resulting discrimination that come along with that. (Which I’ve already experienced some of when a mother wouldn’t let me care for her child because she thought I was autistic) But that’s not me personally regretting being perceived as autistic, just regretting what people think that being autistic means.

So there it is, my answer. It’s a fair bit longer than I thought it was, but I’m satisfied with it. And I think it just goes to show how far a little bit of autism understanding can take you. I’m glad my friend asked the question.

Have any questions of your own for me on what it’s like to be a sibling? Leave them in the comments!

-Creigh

Picture reads: Does it bother me that because I'm a sister of an Autistic person people are more likely to think I might be autistic, too?

0 Comments

“I think I have autism. How to check it?

74,193

Question for an expert Teenagers

I am 16 years old and I notice some strange traits in myself, most of them from early childhood. I searched the Internet for information and found that something similar happens with people with autism spectrum disorder.

- Can't control my emotions. In short, I am capable of bursting into tears at any moment, laughing too loudly in public.

Sometimes, in the heat of anger, I tell my loved ones that I hate them.

Sometimes, in the heat of anger, I tell my loved ones that I hate them. - I walk on my toes when I'm very passionate about something or when I talk about something. This feature has not gone away for more than 12 years, even doctors do not know what it is.

- I'm afraid of something new. It is difficult for me to make new acquaintances and communicate with people, I hate being late and I am afraid of unfamiliar places. I also don’t like trying new foods, so I eat pasta and cheesecakes all my life.

- I don't feel social norms: I don't understand, for example, why you can't sit on the railings in the subway. A couple of times I took other people's things without asking, for example, my sister's socks.

- I am hypersensitive to heat, sound and light. I don’t wear a hat in the winter because I feel so uncomfortable, and for the same reason I don’t tie my hair. I go berserk when you touch my hair. If I'm hot, I immediately start crying.

I get frightened by loud sounds and literally freeze in place, losing contact with the outside world.

I get frightened by loud sounds and literally freeze in place, losing contact with the outside world. - Can't play in a team. I just can't figure out how to do it.

Do these signs mean anything? And if so, what should I do next, where should I go?

Eliza, 16 years old

Good afternoon, Eliza! Autism spectrum disorders are characterized by:

- lack of opportunity to initiate and maintain socially significant communication;

- the presence of limited, repetitive, rigid actions, thoughts, patterns of behavior.

There is such a term: “special interest”. A person is ready to talk about the subject of his interest for hours and reacts very sharply when he is interrupted. For example, a child can study dinosaurs and only dinosaurs from 5 to 11 years old, grow to an expert level in their study.

In this case, a person needs a special interest for its own sake: there is no social component, the need for the approval of loved ones or the satisfaction of ambitions. A person is 100% involved and "turns off" from the outside world.

A person is 100% involved and "turns off" from the outside world.

The world of a person with autism is isolation in instability. Any change is perceived as a disaster. And rituals become the key to controlling the surrounding reality. A person with ASD struggles for the complete immutability of being.

Insufficient stability of the image of "I" and the world is associated with hypersensitivity and the tendency of such people to "sensory overload". A person with ASD can practically experience physical pain when touched by others or loud sounds are heard. At the same time, social interaction also acquires paradoxical features: the obstacle to contact with another is not the unwillingness to communicate, but the unbearability of communication.

Many people with ASD are unable to "feel" those around them. And they need to develop their own system of acceptable response based on logic. This allows you to fit into the social context of the situation and reduce stress.

This disorder affects all areas of a person's life: personal and family life, education, professional activities

Thus, sensory deficits, difficulties in social interaction and "recognition" of one's own emotions and feelings are woven into a bizarre tangle of contradictions. This leads to mental confusion, increased anxiety, fear of one's own failure.

But people with ASD often also have incredible abilities: this is a specific imagery of thinking, reliance on visual stimuli, the ability to easily handle large amounts of data. It is very difficult for "normotypes", or ordinary people, to imagine how incomprehensible their world seems to the "rain man". Especially those aspects of it that relate to communication.

And here a conscious, systematic study of the world of relationships comes to the rescue. An ordinary child "grasps" the world of people as a whole, while a person with ASD goes "from the bottom up", analyzing particulars, forming standards, learning the rules.![]()

Imagine that you are learning a foreign language, decoding the signals of others and making them understandable. The world around us is a game with rules that change. You will have to adapt, analyze. And it's like a computer game where you go from level to level. Deficiencies and features may not appear for a long time. Until the demands of society exceed the capabilities and resources of a person with ASD.

This disorder affects all areas of a person's life: personal and family life, education, professional activities, and so on. If difficulties arise in only one sector, most likely, we are talking about a particular case of maladaptation, and not about the spectrum.

Diagnosis of ASD in adulthood has a number of difficulties. For some reason, we still think that autism is lowing, silence and diapers at 25. Although in reality people of the spectrum can demonstrate a level of intelligence much above average and fit into the social system great, like, for example, Temple Grandin (American scientist and writer).

Differential diagnosis is very subtle here, since there may be other conditions, as if “hinting” to autism

Neuropsychologist Oliver Sachs wrote: "Every autistic person is an island cut off from the mainland." But, fortunately, in our time, people have learned to build bridges and build boats.

There can be no general recommendations for people on the spectrum. “If you met one person with autism, then you met only one person with autism,” they say in the USA. However, an important part of the therapy of such people is the work with the definition of their own feelings and emotions. Cognitive behavioral therapy will make life much easier.

A type of physical activity that is comfortable for you will be a good help. It would be nice to calibrate the sensory systems, take care of yourself and your body. It is important to find something of your own and close to you, to "ride" the wave.

As for the exact diagnosis of your condition, it is better to address this question to a psychotherapist who deals with ASD and has been doing it all his life. Precisely because high-functioning autists are practically not diagnosed in our country. And the differential diagnosis here is very subtle, since there may be other conditions that seem to “hint” at autism, for example, attachment disorders. What was previously called "cold mother". Or, for example, violations of sensory integration due to minor trauma in childbirth.

Precisely because high-functioning autists are practically not diagnosed in our country. And the differential diagnosis here is very subtle, since there may be other conditions that seem to “hint” at autism, for example, attachment disorders. What was previously called "cold mother". Or, for example, violations of sensory integration due to minor trauma in childbirth.

It is necessary to look at the features of development at an early age, the facts presented are not enough. But the expert will ask about it. I can’t give you a specific specialist, because patients with ASD do not come to me with requests for verification of the diagnosis.

In addition, you are now in a difficult, crisis period of development: 16 years is puberty. Despite many of the symptoms you listed, trying to self-diagnose autism may involve looking for the idea of otherness as an attempt to define yourself and explain what is happening to you. And then there is no question of autism as such - a psychologist who deals with people of adolescence will help here.

Photo Source: Getty Images

New on the site

"Stay on target, don't blame everyone around and don't feel sorry for yourself": how to get into the Forbes list

Why do we change: is it "choice paralysis"?

How to know if you are a deep person — a comment from a Gestalt therapist what is obstetric violence and why does it happen. Part 1. Pregnancy

Contrast shower, breakfast and break: 16 rules for slimness - take care of yourself

"Panic attacks have stopped, but the fear of death has not gone away"

How autistics see us | PSYCHOLOGIES

77,301

Man among men

These are strange children. Their eyes elude us, and we ask ourselves if they see us at all. Their behavior is surprising, and even frightening: they can randomly wave their arms for a long time, spin around in one place or ask the same question many times in a monotone voice ... Autism - the name of the disorder they suffer from - often turns into an insulting mockery breaking the hearts of parents.

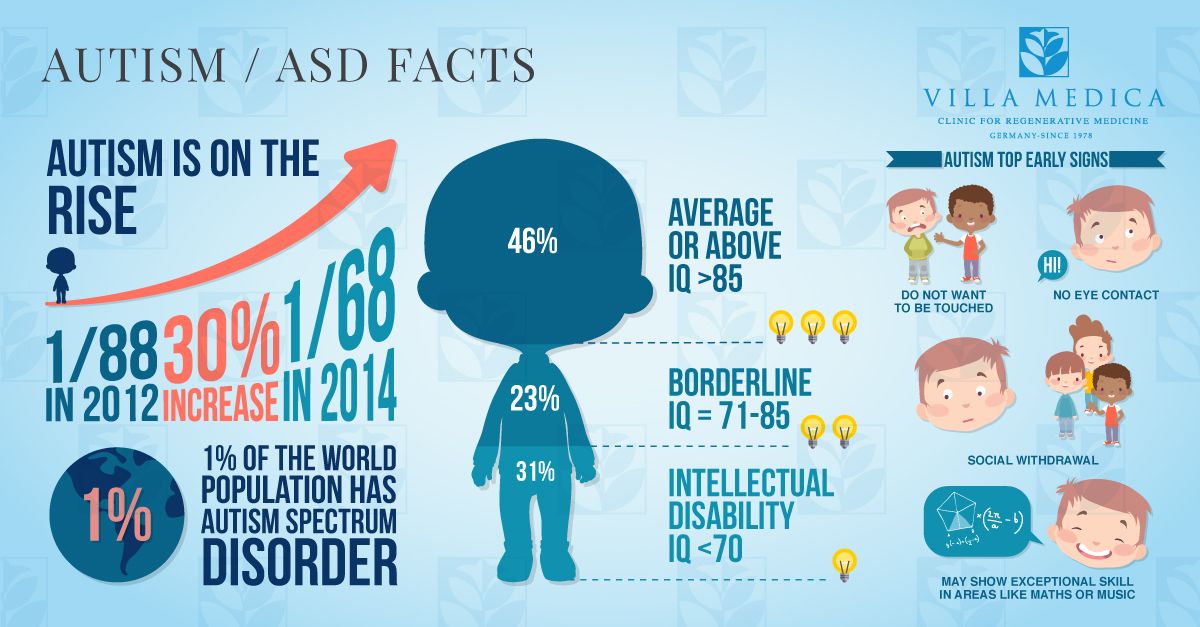

Over the past two decades, the number of people diagnosed with autism has been growing rapidly around the world. “For example, in the US, this diagnosis is made to one in 88 children,” says psychiatrist Brian King, director of the Seattle Center for Children with Autism (USA). “And in South Korea, even one in 38.” There are no exact figures for Russia, but, according to experts, in any class and in any group of kindergarten there is a child with one of the mild forms of autism.

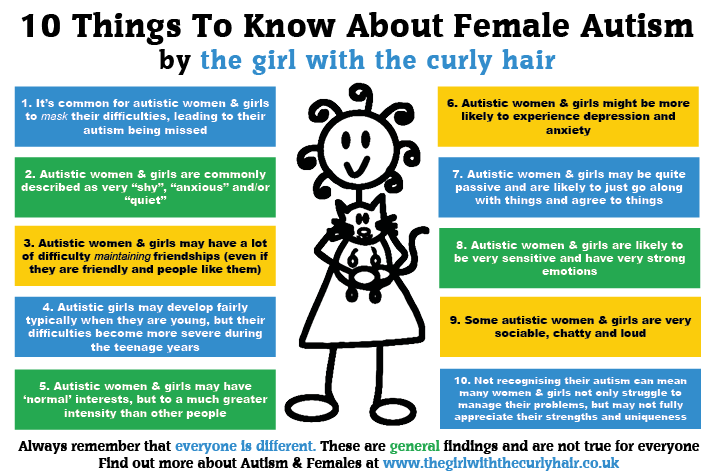

A few months after birth, these children already seem unusual (although the diagnosis is made at a year and a half). Manifestations are extremely diverse, not without reason experts say: "If you know one person with autism, this does not mean that you know about autism."

Some children will acquire speech, others will not. Some will lag behind in mental development (about 45% of them), others will show a brilliant intellect or a phenomenal memory. Someone will make discoveries or write books, and someone will never be able to learn to read. But no matter how different they are, people with autism are able to open up if we make an effort to teach them how to communicate with us.

But no matter how different they are, people with autism are able to open up if we make an effort to teach them how to communicate with us.

They do not distinguish a person's voice from other sounds

The originality of an autist is primarily in the fact that he hears, sees, and feels reality in a different way.

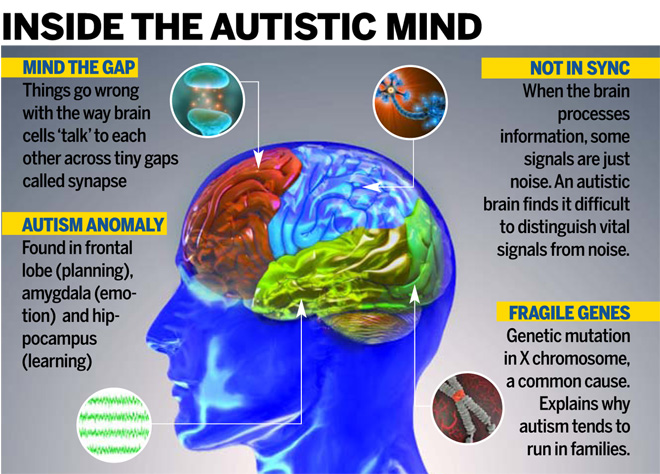

“Due to genetic disorders, the brains of these children are overactive,” says Monika Zilbovicius, a psychologist at the French Institute for Health and Medical Research (Inserm). - He simply does not have time to combine, analyze everything that the child sees, hears, touches. The world is perceived fragmentary and distorted.

Perceptual impairment can cause a child to confuse a raised finger with a pencil, for example. For him, the human voice is no different from other sounds: he does not respond to his name (it seems to his parents that he does not hear), but he flinches when a car passes along the street. Such sensory confusion also occurs in relation to touch: “Masha is now 4 years old, she cannot stand the touch of soft materials like velvet, as if they burn her,” her mother says. “But she likes to touch and stroke the spiky washcloth.”

“But she likes to touch and stroke the spiky washcloth.”

Their sensations are not connected

We all communicate with other people through the senses, they help to navigate the world and understand others. Data from the organs of sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell, entering the brain of a child with autism, are superimposed on each other, like bricks that are not cemented together. And as soon as something unexpected happens, such as a loud phone call or a strong desire to go to the toilet, the unstable pile of “sensory bricks” crumbles. There is panic.

Nine-year-old Maxim, for example, cannot stand applause. This sound causes an acute anxiety in the boy, because of which he can completely lose control of himself. Anomaly of sensory perception is the cause of inexplicable crying in children with autism at an early age. Hence their desire to find a sensation that will calm the inner storm: to look at a spinning toy, to bite oneself, to sway.

Some stereotyped movements are typical of autism, such as the rapid flailing of the arms, which parents describe as a frightened bird or butterfly beating its wings..png.1755431ccb56810ddc59cd3661612df2.png) All these repetitive movements soothe such children, restoring their self-confidence and a sense of security.

All these repetitive movements soothe such children, restoring their self-confidence and a sense of security.

Change is possible

“Autism is “growing differently”: these kids think and learn in their own way, they process information differently,” says Joe Stevens, director of the EarlyBird autism program (UK). “We don't have a magic ball to see what the child will be like in the future. But everyone can achieve positive changes. Parents are their child's best teachers, but they need the support of professionals. There is only one reason for failure - if the child has not been selected the right assistance program for him. We need not to calm down, but to continue to look for tools that will allow him to communicate with the world.”

They do not pick up other people's emotions

We can communicate with other people because we are able to understand their feelings. From the very first months of life, the baby learns to distinguish the expression on the mother's face and to capture her emotional state. Gradually, he begins to establish connections between his feelings and what is happening in the outside world.

Gradually, he begins to establish connections between his feelings and what is happening in the outside world.

For example, when falling, children always look at the reaction of their parents. If the mother is frightened and frowns, the child understands that something bad has happened, but if she helps him up with a smile, then this event no longer looks dramatic for him. Over time, the child begins to recognize and name his various states with words. The perception of oneself is formed on the basis of the reactions of other people, and above all - the mother.

But a child with autism does not have this opportunity. “His brain receives only a partial image of those who address him,” explains Monika Zilbovicius. For example, he only sees the mouth and cheeks, but not the eyes. As a result, he simply does not have a chance to learn to distinguish between facial expressions of joy, anger, sadness and many other emotions that are an important part of our non-verbal communication.

Most children, by about the age of three, are able to attribute a certain mood to another. The child gradually catches that the thoughts, ideas, desires of others are different from his own, so gradually children begin to communicate and interact with others. Having learned to understand their behavior and desires, they find real pleasure in this interaction.

Their thinking is concrete

To reiterate, a child diagnosed with autism has difficulty understanding emotions. Even when he has a high level of intelligence and uses speech correctly, others still confuse him, sometimes frighten him, and all too often remain incomprehensible.

14-year-old Ella is doing well in the school program. But it is extremely difficult for her to perceive the jokes of her classmates. “When we talk, we use metaphors, abstract images, we rely on intonation,” explains Christine Hull, clinical psychologist at the Autism Center in Atlanta (USA). “All this escapes the child with autism. For him, a word is just a word. Because the autistic mindset is concrete mindset.”

For him, a word is just a word. Because the autistic mindset is concrete mindset.”

Ella sees that others are laughing at her words, but is unable to understand what made them laugh. “Children like Ella are not capable of metaphors, they are not able to understand them spontaneously,” the psychologist adds. - When a child hears that his mother "swallows books", he sees her literally swallowing sheets of paper. It is difficult for him to understand the implicitly expressed, and especially that which makes it so difficult to study at school - abstraction.

What is the cause of autism?

Autism is a congenital disorder of mental development. They can't get sick, and they can't be cured. “For a long time, experts assumed that autism could be the result of psychological trauma received in early childhood, when parents were cold and cruel in their treatment of the child,” says Brian King. - According to another version, vaccines for childhood vaccinations could provoke it. However, neither hypothesis was confirmed."

However, neither hypothesis was confirmed."

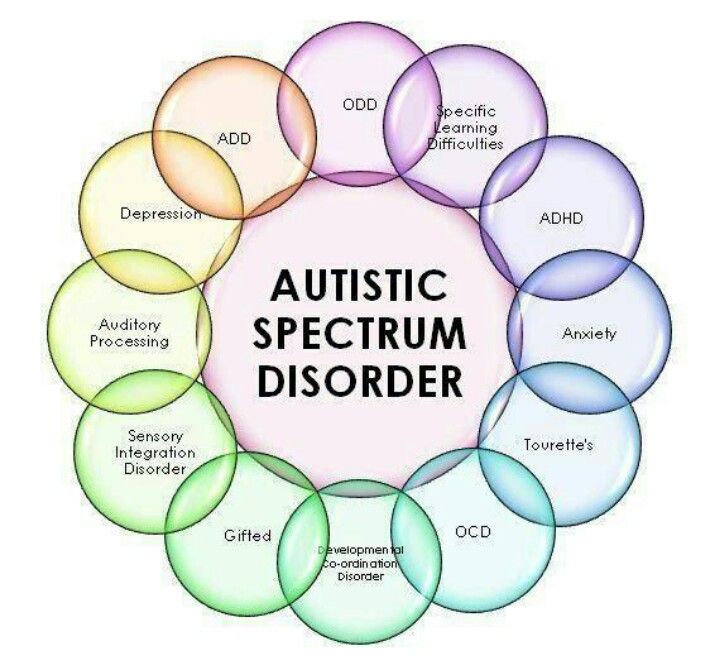

The cause of autism in genetic failures, emphasizes the psychiatrist. According to other data, in people with autism, there is a redundancy of neural connections between parts of the brain. As a result, their brains are overloaded and unable to cope with the flow of information. In addition, premature babies weighing less than 2 kg are 5 times more likely to develop autism spectrum disorders than other newborns.

It is difficult for them to learn the rules of behavior

A person with autism who does not "read" the experiences of others also finds it difficult to get others to understand his own feelings. His voice sounds monotonous, without modulations, he can say "thank you very much" in an angry tone that he himself does not feel, he can unwittingly make tactless remarks.

Thus, Ella, in front of her other classmates, told her math teacher that she had a “hefty nose”. She didn't mean to offend her at all. But the inability to perceive other people's emotions often causes irritation or even anger.

“For them, living in society is like wandering through a dense forest,” emphasizes Christine Hull. Even people with “high-functioning” autism—those who graduate, work, and live with non-autistics—admit that they constantly feel insecure. “I had to learn by heart how to behave in every situation,” says one of the famous autistic Temple Grandin (Temple Grandin) in the book Opening the Doors of Hope.

They spend a lot of energy to live among us

One can cite as an example the young Muscovite Svetlana, who has matured and is already working as an engineer, but at 26 she has never learned to look her interlocutors in the eye: “Although no one does not notice, because I have trained to look at the point between the eyebrows when I am talking to a person. Always on the lookout, from a very early age they spend all their energy living among us, adapting to sounds and sights and finally understanding what we say.

“Yes, they show empathy deficits, but that doesn't mean they're incapable of feeling emotions,” warns Christine Hull. - They need love, affection, warm relations just like we do. If not more! And he concludes with a smile: “And we must meet them halfway, give each of them the keys that he needs. Don't behave like people with autism towards them."

- They need love, affection, warm relations just like we do. If not more! And he concludes with a smile: “And we must meet them halfway, give each of them the keys that he needs. Don't behave like people with autism towards them."

“We are different, but not worse”

Steve Summers, an adult with Asperger's Syndrome, wrote a poignant confession, which is published on the Autismum portal.

“I'm autistic and I'm tired. Tired of being rejected. Tired of being ignored. Tired of being expelled. Tired of being treated like an outcast. Tired of people who don't understand what autism is. From people who refuse to accept autistic people for who they are. Tired of other people's expectations that I will try and behave "normally". I'm not "normal". I am autistic. Do you want to help us? Listen to autistic people. Put more effort into learning about autism. Accept that we are different, but not worse. Don't try to turn us into a bad copy of your "normal" idea. Accept that it's okay for us to be ourselves.