Evaluating a psychological test

Frequently Performed Psychological Tests - Clinical Methods

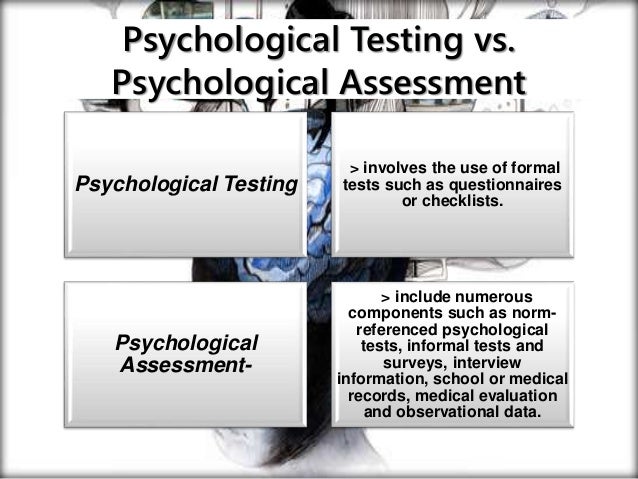

Definition

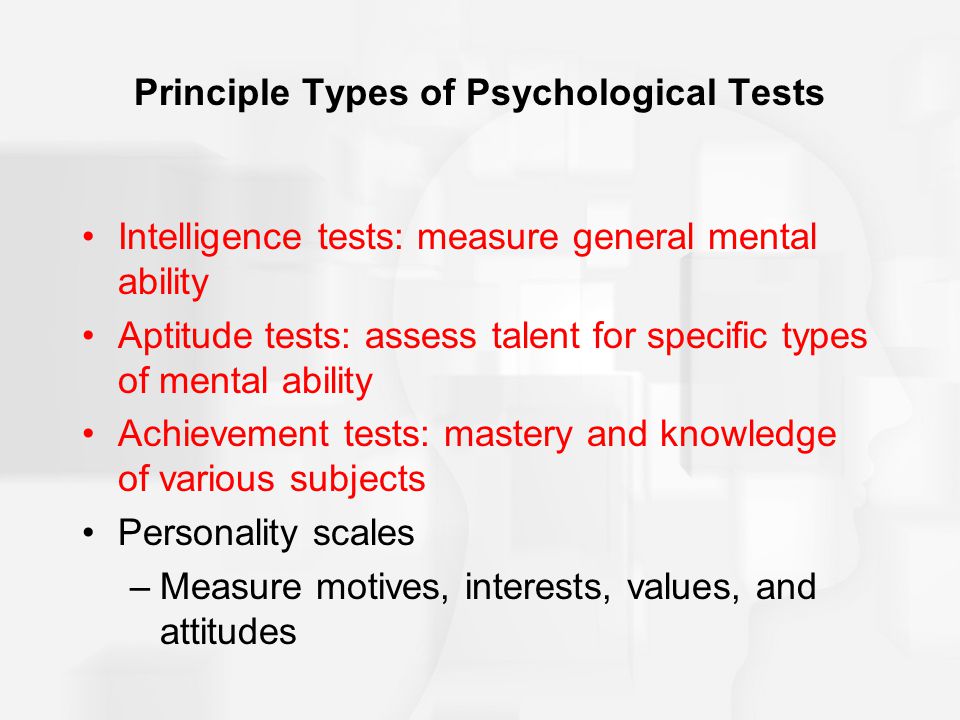

A psychologic test is a set of stimuli administered to an individual or a group under standard conditions to obtain a sample of behavior for assessment. There are basically two kinds of tests, objective and projective. The objective test requires the respondent to make a particular response to a structured set of instructions (e.g., true/false, yes/no, or the correct answer). The projective test is given in an ambiguous context in order to afford the respondent an opportunity to impose his or her own interpretation in answering.

Technique

Psychologic tests are rarely given in isolation but as a part of a battery. This is because any one test cannot sufficiently answer the complex questions usually asked in the clinical situation. Most diagnostic questions require the assessment of personality, intelligence, and perhaps even the presence of organic involvement. A typical battery of tests includes projective tests to assess personality such as the Rorschach and the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), an objective personality test such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), a semistructured test like the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Test, and an intelligence test, usually the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale Revised (WAIS-R).

The most important consideration for the physician is when to ask for psychologic assessment. As with medical diagnostic procedures, we are interested in finding answers to diagnostic questions that cannot be obtained through direct observation or interview. In our clinical experience, there are a myriad of circumstances requiring psychologic consultation either to assist in or rule out medical intervention. Some of the more typical situations include compliance, behavioral management, affirmation of clinical findings, the use of supportive drug therapies, and continuity of care issues.

Five case examples are offered to illustrate the above situations.

Mr. S. was a 35-year-old single salesman hospitalized for gastrointestinal problems associated with a previous operation. He had a history of noncompliance with both drugs and nutrition regimens. Severe debilitation would ensue following outpatient treatments, after which he would be hospitalized. This pattern repeated itself several times.

Psychologic assessment data were consistent with a pattern of addictive behavior and poor coping mechanisms under stressful conditions. Recommendations included a drug rehabilitation program and stress management techniques.

Dr. L., a 68-year-old retired dentist, had severe behavioral management problems with the nursing staff. He was verbally punitive and intrusive of other patients" privacy. Psychologic assessment revealed an organic brain syndrome indicating greater individual care and a lower expectation of his performance.

A 21-year-old single male, Mr. N., was admitted for hospitalization complaining of severe stomach pains and rectal bleeding. Psychologic testing was administered because the internist could find no evidence of physical pathology. Test battery results described a young man under an inordinate amount of stress due to a huge difference between his intellectual capabilities and the demands of his work place.

The recommendation was to find other employment and to work with a counselor to develop more realistic vocational goals.

Ms. C. was a middle-aged housewife complaining of panic attacks of unknown origin. She also said that she was in severe depression because of the death of her daughter 2 years previously. The clinical question was whether she should be given antidepressants or antianxiety agents as an adjunct to psychotherapeutic intervention. Test results were consistent with a state of anxiety as opposed to an affective disorder.

Ms. B. was a 23-year-old single female who was hospitalized following a drug overdose from a suicide attempt. Information was needed to determine how dangerous she was to herself, how restrictive an environment she needed for treatment, and what type of therapy was appropriate. Test results confirmed a compulsive personality with a dramatic flair. Ms. B. needed extensive individual psychotherapy but did not require lengthy hospitalization.

Nevertheless, it was essential to link her with outpatient care while she was still motivated to receive care.

Although the above examples are by no means exhaustive, they do point out the variety of commonly occurring circumstances in which psychologic assessment may be useful. It is important when ordering testing to formulate the diagnostic question in as specific a manner as possible. Such requests as "describe personality dynamics" or "rule out psychologic disturbance" are too general to answer in an effective and efficient manner. Do not hesitate to ask exactly what you want to know. The psychologist will inform you if he or she is unable to answer. Use the examples described above to formulate your question: Is this patient depressed? Is this patient psychotic? Why is this patient not conforming to the treatment regimen?

When presenting a patient to a psychologist for evaluation, it is helpful to have demographic data and a detailed history of the client. Also, the description presented of the problems should be in behavioral terms. Saying that a patient appears to be depressed is not as helpful as describing him or her as having a loss of appetite, early morning rising, or slowness of speech. If the patient is a management problem, give a concrete description of what this entails: won"t go to rehabilitation therapy, won"t let a technician draw blood.

Also, the description presented of the problems should be in behavioral terms. Saying that a patient appears to be depressed is not as helpful as describing him or her as having a loss of appetite, early morning rising, or slowness of speech. If the patient is a management problem, give a concrete description of what this entails: won"t go to rehabilitation therapy, won"t let a technician draw blood.

Finally, the referring physician may request either a specific test or an abbreviated battery. While some psychologists will go along with this practice, we do not encourage it. Psychologic tests, particularly personality ones, are only as good as the skills of the individual who administers and interprets them. The psychologist must feel confident and competent in the battery that he or she administers. Therefore, the number and choice of tests should be those of the psychologist, just as the medical procedures chosen for a patient are the responsibility of the physician in charge.

Basic Science

The most commonly used personality tests are the Rorschach, TAT, and MMPI. The assumptions underlying projective tests such as the Rorschach and TAT are that the standard set of stimuli are used as a screen to project material that cannot be obtained through a more structured approach. Ambiguous inkblots or pictures reinforce the use of individual expression and reduce resistance. A frequent criticism is the assumption that the individual simply responds to ambiguity with trivia or with what was most recently experienced, such as last night's television fare. The response to this criticism is the notion of psychic determinism. Behavior is a function of choice, not chance. Thus, how a person responds is a reflection of personal motives, fantasies, and needs.

The assumptions underlying projective tests such as the Rorschach and TAT are that the standard set of stimuli are used as a screen to project material that cannot be obtained through a more structured approach. Ambiguous inkblots or pictures reinforce the use of individual expression and reduce resistance. A frequent criticism is the assumption that the individual simply responds to ambiguity with trivia or with what was most recently experienced, such as last night's television fare. The response to this criticism is the notion of psychic determinism. Behavior is a function of choice, not chance. Thus, how a person responds is a reflection of personal motives, fantasies, and needs.

The best-known psychologic assessment tool is the Rorschach, the "inkblot test." It was first published by Hermann Rorschach in 1921 and was introduced to the United States in 1930 by Samuel Beck. The test consists of 10 symmetrical inkblots, half of which are acromatic. It is administered by giving the respondent one card at a time and asking him or her to describe what is seen. The respondent is told that he or she can see one or more things and that there are no right or wrong answers. The tester records the responses verbatim. There is then a second phase of testing called the inquiry. The respondent is again presented with each of the ten cards and asked to note the location of the response and what determines his or her answers.

The respondent is told that he or she can see one or more things and that there are no right or wrong answers. The tester records the responses verbatim. There is then a second phase of testing called the inquiry. The respondent is again presented with each of the ten cards and asked to note the location of the response and what determines his or her answers.

A large body of research takes to task the reliability and validity of projective techniques in general and the Rorschach in particular. The issue of reliability cannot be approached in a conventional sense with projective techniques. The Rorschach inkblots and the TAT pictures do not lend themselves to split-half reliability because the stimuli are not designed to be equivalent with each other. Test–retest reliability is difficult because many of the variables addressed by the test are affected by time. Interjudge reliability indices using Rorschach summary scores have been reported to be favorable, and Exner (1978), using his own scoring system, has reported test–retest reliability correlations ranging from . 50 to .90 on 17 different variables.

50 to .90 on 17 different variables.

Attempts at measuring the validity of the Rorschach also suffer from problems inherent in the nature of the test. The Rorschach is designed to assess highly complex, multidetermined behaviors for which prediction about specific acts is nearly impossible. It also assesses covert needs and fantasy life that may not currently or ever manifest themselves in overt behavior. Concurrent validity is contaminated by the unreliability of psychiatric diagnoses and the fact that individuals with similar diagnoses may indeed behave differently. In response to the criticisms on validity, Korner (1960) has answered that there is no good assessment technique capable of predicting behavior, so why criticize the Rorschach. He goes on to point out that projective techniques are not magic. They describe the personality at work, its adaptations and compromises, and the balance between fantasy and the demands of reality.

The TAT was developed by Henry Murray and Christiana Morgan in 1935. It consists of 30 achromatic picture cards, categorized into those appropriate for boys, girls, men, and women. It is customary to present approximately 10 cards to the respondent, who is then asked to tell a story about what is happening in the picture, what led up to it, and how will it turn out. The respondent is also asked to describe the characters" thoughts and feelings. As with the Rorschach, interjudge reliability is the most applicable test. Correlations have been about .80. The validity of the TAT can be measured when it is defined using specific procedures with a particular population and operationally defined criteria. Studies have examined both construct and concurrent validity. Stories have correlated significantly with behavioral measures of achievement and aggression. A correlation of .74 has been obtained between TAT expressed needs and those needs rated from autobiographies.

It consists of 30 achromatic picture cards, categorized into those appropriate for boys, girls, men, and women. It is customary to present approximately 10 cards to the respondent, who is then asked to tell a story about what is happening in the picture, what led up to it, and how will it turn out. The respondent is also asked to describe the characters" thoughts and feelings. As with the Rorschach, interjudge reliability is the most applicable test. Correlations have been about .80. The validity of the TAT can be measured when it is defined using specific procedures with a particular population and operationally defined criteria. Studies have examined both construct and concurrent validity. Stories have correlated significantly with behavioral measures of achievement and aggression. A correlation of .74 has been obtained between TAT expressed needs and those needs rated from autobiographies.

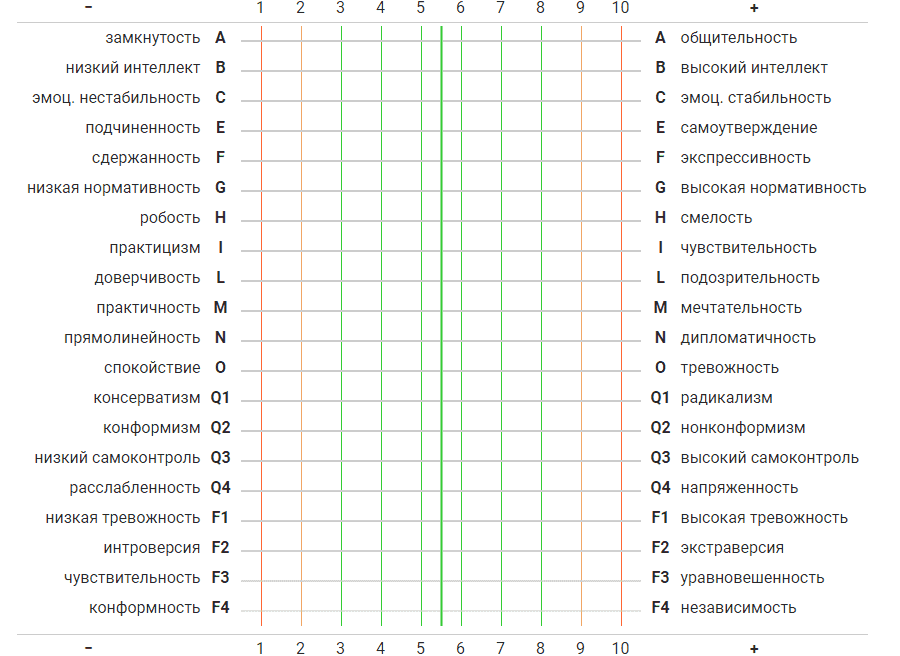

The most frequently used objective test for personality is the MMPI. It was published by Hathaway and McKinley in 1943 and revised in 1951. It is designed for ages 16 and over and contains 566 items to be answered yes or no. It may be administered to an individual or group, and the answer sheets can be hand- or machined-scored. The respondent is asked to read each question and decide what is true or false as applied to him or her and then to mark that response on the answer sheet. The test has four validity scales and eight clinical scales. The scales were developed empirically by administering an item pool to a large group of normal subjects, and contrasting their responses to those of selected homogeneous criteria groups of psychiatric patients. Those items that discriminate between the groups were used.

It is designed for ages 16 and over and contains 566 items to be answered yes or no. It may be administered to an individual or group, and the answer sheets can be hand- or machined-scored. The respondent is asked to read each question and decide what is true or false as applied to him or her and then to mark that response on the answer sheet. The test has four validity scales and eight clinical scales. The scales were developed empirically by administering an item pool to a large group of normal subjects, and contrasting their responses to those of selected homogeneous criteria groups of psychiatric patients. Those items that discriminate between the groups were used.

Results of the test are coded onto a profile sheet for interpretation. The mean t-score for each scale is 50 with a standard deviation (SD) of 10. The scale is significantly elevated beyond an SD of 2 or t-score of 70. Even though the MMPI is empirically derived, it shares a similar problem with the projective tests in terms of reliability and validity, that is, it is based on psychiatric diagnoses. How valid and reliable were the diagnoses of the patients in each of the criteria groups? The MMPI thoroughly addresses some other aspects of validity. The lie score (L) assesses social desirability. The F score is an internal consistency check, and the K score assesses test-taking attitude along a frankness–defensive continuum.

How valid and reliable were the diagnoses of the patients in each of the criteria groups? The MMPI thoroughly addresses some other aspects of validity. The lie score (L) assesses social desirability. The F score is an internal consistency check, and the K score assesses test-taking attitude along a frankness–defensive continuum.

An interesting hybrid between the projective and objective assessments is the semistructured incomplete-sentence test. While ostensibly a projective technique in which the respondent reflects his or her own wishes or conflicts to complete a sentence stem, it easily lends itself to objective scoring or screening for experimental use. The Rotter Incomplete Sentence Test is one of the more popular of this form of assessment. It contains 40 sentence stems each of which is to be completed by the respondent. The test takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and may be administered to an individual or to a group. It was originally used as a screening device to determine mental disturbance at an army convalescent hospital. Reliability and validity correlations are quite acceptable. The interjudge reliability is about .90, and split-half reliability is .83. As to validity, correlation coefficients with adjustment and maladjustment classifications for women was .64 and for men .77.

Reliability and validity correlations are quite acceptable. The interjudge reliability is about .90, and split-half reliability is .83. As to validity, correlation coefficients with adjustment and maladjustment classifications for women was .64 and for men .77.

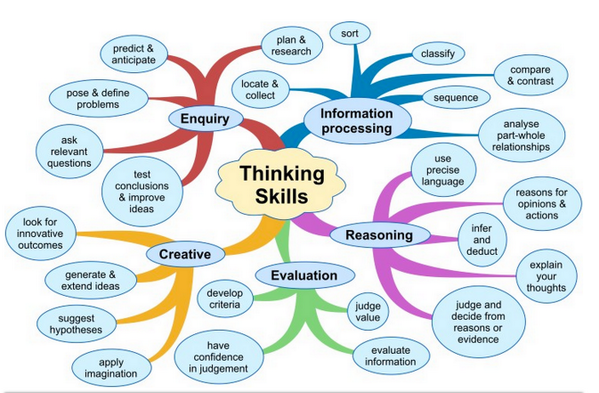

The use of intelligence testing in a clinical setting may be puzzling to the reader. In many ways the intelligence test is the foundation for differential diagnosis to the psychologist. The intelligence test measures major mental abilities that may be affected by the presence of an organic disease or injury, thought disorder, or environmental stress. The patterning of the scores on the intelligence test gives the psychologist clues as to the presence, extent, and relative influence of each of the above factors. The most empirically sound intelligence test is the WAIS-R, which was revised in 1981. The WAIS-R contains 11 tests, 6 verbal and 5 nonverbal. It was standardized on a stratified sample of ages ranging from 16 to 74 years, 11 months. The basic score is the intelligence quotient (IQ), a comparison of the individual with the average score of his or her age group. Each of the 11 tests also has its own scale scores, which are conversions of raw scores dependent also on comparison to reference groups. The sum of scale scores are converted to three IQ scores: verbal, performance, and full-scale IQs. Mean IQ is 100 with an SD of 15; thus, two-thirds of all adults have an IQ between 85 and 115. Reliability coefficients are excellent in the mid-90's range. In terms of validity, there is a .50 correlation with school performance and a .85 correlation with the Stanford–Binet test of intelligence. The WAIS-R takes approximately 90 minutes to administer and requires a competent tester.

The basic score is the intelligence quotient (IQ), a comparison of the individual with the average score of his or her age group. Each of the 11 tests also has its own scale scores, which are conversions of raw scores dependent also on comparison to reference groups. The sum of scale scores are converted to three IQ scores: verbal, performance, and full-scale IQs. Mean IQ is 100 with an SD of 15; thus, two-thirds of all adults have an IQ between 85 and 115. Reliability coefficients are excellent in the mid-90's range. In terms of validity, there is a .50 correlation with school performance and a .85 correlation with the Stanford–Binet test of intelligence. The WAIS-R takes approximately 90 minutes to administer and requires a competent tester.

A physician who wants to rule out an organic brain syndrome may call upon neuropsychologic testing. This is particularly true when a CT scan is negative in the presence of suspicious symptomatology (early Alheizmer's disease), in assessing the relative importance of organic versus psychologic variables in the behavior of trauma victims, and in differentiating between dementia and depression in the elderly. For cases in which an intense work-up for neurologic deficits is required, the patient should be referred to a specialist for neuropsychologic assessment. Since this procedure can be costly and time-consuming, the physician may want to screen first for the presence of a brain dysfunction. Most psychologists are well trained for this task. We will briefly describe two neuropsychologic tests that are useful for screening purposes. We do not necessarily endorse them as the best available, but only those with which we have familiarity.

For cases in which an intense work-up for neurologic deficits is required, the patient should be referred to a specialist for neuropsychologic assessment. Since this procedure can be costly and time-consuming, the physician may want to screen first for the presence of a brain dysfunction. Most psychologists are well trained for this task. We will briefly describe two neuropsychologic tests that are useful for screening purposes. We do not necessarily endorse them as the best available, but only those with which we have familiarity.

The first test is the Aphasia Screening Test adapted by Reitan (1984) from the Halstead/Wepman Aphasia Screening Test. It assesses several areas of dysfunction including dysphonia, dyslexia, spelling and constructional dyspraxia, and dyscalculia. The test uses the sign approach, that is, positive findings have distinct and definite significance, but normal performance cannot rule out organicity. Anyone with a basic grade school education is capable of answering every item correctly. The test is simple to administer and consists of 32 items that do not usually require more than 20 minutes to complete. The second, called the Category Test, is the most powerful in the Halstead/Reitan test battery. It consists of 205 stimuli and is divided into seven subtests. The Category Test assesses central processing, abstraction, and reasoning. The cutoff score is 51 errors. While Reitan recommends the use of a slide presentation with his own design projector and feedback system, DeFillipis and McCampbell (1979) have designed a much simpler method of presentation. Their Booklet Category Test (BCT) is portable, requiring only two loose-leaf notebooks and an answer sheet. They report .91 correlation between the BCT and the Category Test. There are two major criticisms of the Category Test: there is no normative data, and reliability has not been adequately studied. One study did report a test–retest correlation of .93.

The test is simple to administer and consists of 32 items that do not usually require more than 20 minutes to complete. The second, called the Category Test, is the most powerful in the Halstead/Reitan test battery. It consists of 205 stimuli and is divided into seven subtests. The Category Test assesses central processing, abstraction, and reasoning. The cutoff score is 51 errors. While Reitan recommends the use of a slide presentation with his own design projector and feedback system, DeFillipis and McCampbell (1979) have designed a much simpler method of presentation. Their Booklet Category Test (BCT) is portable, requiring only two loose-leaf notebooks and an answer sheet. They report .91 correlation between the BCT and the Category Test. There are two major criticisms of the Category Test: there is no normative data, and reliability has not been adequately studied. One study did report a test–retest correlation of .93.

Clinical Significance

The Rorschach describes personality structure, offering a multidimensional picture of the individual's current functioning and potential. As Korner (1960) states, the Rorschach shows the personality at work. There are several scoring systems for the Rorschach, most being based on four major categories: location, determinants, content, and the use of populars and originals. The location, or area of the response, yields information about the respondent's ability toward perceptual organization, abstraction, and synthesis. Determinants of the response refer to those qualities that produce it, such as form, shape, and color. They are tied to such personality variables as emotionality, impulsivity versus control, and openness versus constrictiveness. The content of the block reveals the personal meanings, attitudes, and interests of the respondent. Originals and populars are related to the respondent's creativity, reality testing, and conventionality, among other variables.

As Korner (1960) states, the Rorschach shows the personality at work. There are several scoring systems for the Rorschach, most being based on four major categories: location, determinants, content, and the use of populars and originals. The location, or area of the response, yields information about the respondent's ability toward perceptual organization, abstraction, and synthesis. Determinants of the response refer to those qualities that produce it, such as form, shape, and color. They are tied to such personality variables as emotionality, impulsivity versus control, and openness versus constrictiveness. The content of the block reveals the personal meanings, attitudes, and interests of the respondent. Originals and populars are related to the respondent's creativity, reality testing, and conventionality, among other variables.

Whereas the Rorschach presents personality structure and organization, the TAT reflects the content of personality, including needs, pressures, conflicts, values, and interest. There are instances in which the content of a given TAT story is so revealing of the patient's difficulties that it would be reported verbatim in the psychologic report. Certain cards are said to "pull" specific types of themes: Card 1, attitudes toward authority; Card 4, attitudes toward heterosexual relationships; and Card 5, relationships with the mother figure. Also, diagnostic groups tend to have a certain orientation toward the stories. Obsessive–compulsives may be pedantic. Depressives may have short stories with monosyllabic words. Schizophrenics may have disjointed or delusional content.

There are instances in which the content of a given TAT story is so revealing of the patient's difficulties that it would be reported verbatim in the psychologic report. Certain cards are said to "pull" specific types of themes: Card 1, attitudes toward authority; Card 4, attitudes toward heterosexual relationships; and Card 5, relationships with the mother figure. Also, diagnostic groups tend to have a certain orientation toward the stories. Obsessive–compulsives may be pedantic. Depressives may have short stories with monosyllabic words. Schizophrenics may have disjointed or delusional content.

There are three approaches to interpretation of the MMPI: single scale, statistical, and clinical. Many physicians who order the MMPI are doing so because they are comfortable with the single scale approach. This involves looking at an elevated scale and making assumptions about the patient. As stated, there are eight clinical scales: HS (hypochondriasis), D (depression), HY (hysteria), PD (psychopathic deviant), PA (paranoia), PT (psychothemia), SC (schizophrenia), and MA (hypomania). Although space does not permit a description of all these scales, elevations of each are associated with a diagnostic grouping related to a cluster of symptoms; for example, elevated HS is associated with an immature person with lack of insight who tends to complain about his or her health. Interpretation of single scales must be taken with great caution. The scales were devised to fit with the Kraepelin System of diagnosis, which is outmoded. For instance, there is no longer a diagnostic grouping of psychopathic deviate. Each of the scales has a much different meaning in relation to more modern classifications.

Although space does not permit a description of all these scales, elevations of each are associated with a diagnostic grouping related to a cluster of symptoms; for example, elevated HS is associated with an immature person with lack of insight who tends to complain about his or her health. Interpretation of single scales must be taken with great caution. The scales were devised to fit with the Kraepelin System of diagnosis, which is outmoded. For instance, there is no longer a diagnostic grouping of psychopathic deviate. Each of the scales has a much different meaning in relation to more modern classifications.

The statistical approach for interpretation involves code types. A code type is a particular correlation of elevated clinical scales (e.g., 2 through 7). A large sample of patients are given the MMPI. They are grouped by similarity in code types. These groupings are then correlated with clinical and demographic data, the notion being that patients with similar MMPI profiles will manifest similar problems. The difficulty with this approach, often called the "cookbook" approach, is that the data do not tend to generalize to other settings.

The difficulty with this approach, often called the "cookbook" approach, is that the data do not tend to generalize to other settings.

The third approach to MMPI interpretation is the clinical approach. The expert clinician depends on his or her knowledge of personality dynamics, case history, and current environmental circumstances to formulate hypotheses as to psychologic difficulties of the respondent. The MMPI computer-generated report uses this type of approach. One has to be extremely cautious in relying too heavily on the report because its author has no firsthand knowledge of the respondent. The clinical psychologist administering the MMPI will use the clinical approach but seldom in isolation without other tests, or at least a clinical interview.

The Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank is a screening device. We have found it useful as a way of obtaining content information similar to that of the TAT in patients who were too threatened or too depressed to take on the challenge of making up stories. Rotter has given several suggestions for interpretation in addition to a reliable scoring system. The adjusted person tends to produce stems that are more neutral and flippant. The statements tend to be short, concise, and humorous. The maladjusted individual tends to write longer sentences that are complicated and emotionally charged. A frequent theme is that nobody understands them.

Rotter has given several suggestions for interpretation in addition to a reliable scoring system. The adjusted person tends to produce stems that are more neutral and flippant. The statements tend to be short, concise, and humorous. The maladjusted individual tends to write longer sentences that are complicated and emotionally charged. A frequent theme is that nobody understands them.

It is not unusual for physicians to question the use of intelligence testing on their patients. The common assumption is that the test is not relevant to differential diagnosis. Contrary to this assumption, the intelligence test is an essential part of any test battery. First, the general level of intelligence will determine how much the patient is capable of understanding and therefore cooperating in his treatment. In other words, how concrete or simplified need the physician be in his or her instructions? Second, the intelligence test is a broad-based screening for organicity. The Verbal Scale IQ has been related to left hemisphere functioning and Performance Scale to right hemisphere. A significant difference of approximately 15 points between these two IQs requires more intense assessment. A dramatic difference between a given subscale mean and the mean for that scale may also be cause for concern. A third important use of the results of the intelligence test is its relationship to aspects of personality functioning. As an example, current state of anxiety can be related to subscale scores on digit span and picture completion. Loose association on the similarity or comprehension subtest may be associated with a psychotic process.

A significant difference of approximately 15 points between these two IQs requires more intense assessment. A dramatic difference between a given subscale mean and the mean for that scale may also be cause for concern. A third important use of the results of the intelligence test is its relationship to aspects of personality functioning. As an example, current state of anxiety can be related to subscale scores on digit span and picture completion. Loose association on the similarity or comprehension subtest may be associated with a psychotic process.

In the course of ordering psychologic consultation, if there is any question of the presence of brain dysfunction, the physician may want to order screening in the form of the Category Test and Aphasia Screening Test. The Category Test is the most powerful of the Halstead/Reitan battery. It is essentially a processing test assessing abstraction and reasoning. The Category Test measures level of performance and offers no information concerning localization. Further differentiation in terms of severity, location, or specificity requires more intense evaluation. A quick screening for localization would be the Aphasia Screening Test. It assesses both left and right hemisphere functioning with respect to language ability. If the respondent cannot copy correctly, we might suspect a right hemisphere lesion. On the other hand, if he or she cannot name an object, we might think about a left hemisphere lesion. In the use of this test there will be many false negatives but few false positives.

Further differentiation in terms of severity, location, or specificity requires more intense evaluation. A quick screening for localization would be the Aphasia Screening Test. It assesses both left and right hemisphere functioning with respect to language ability. If the respondent cannot copy correctly, we might suspect a right hemisphere lesion. On the other hand, if he or she cannot name an object, we might think about a left hemisphere lesion. In the use of this test there will be many false negatives but few false positives.

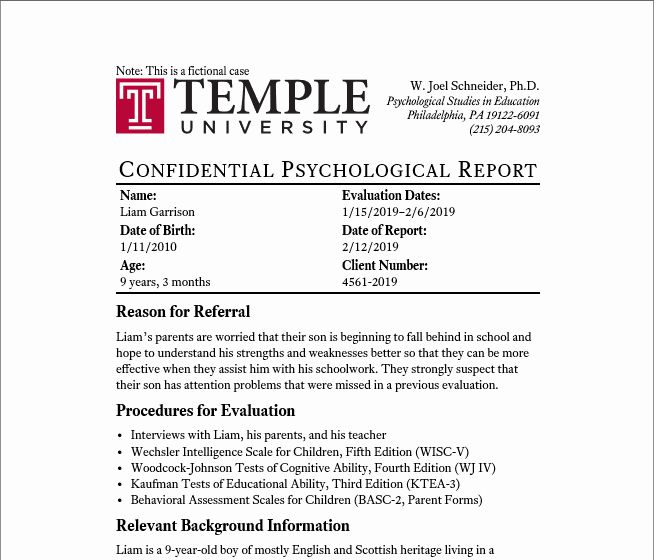

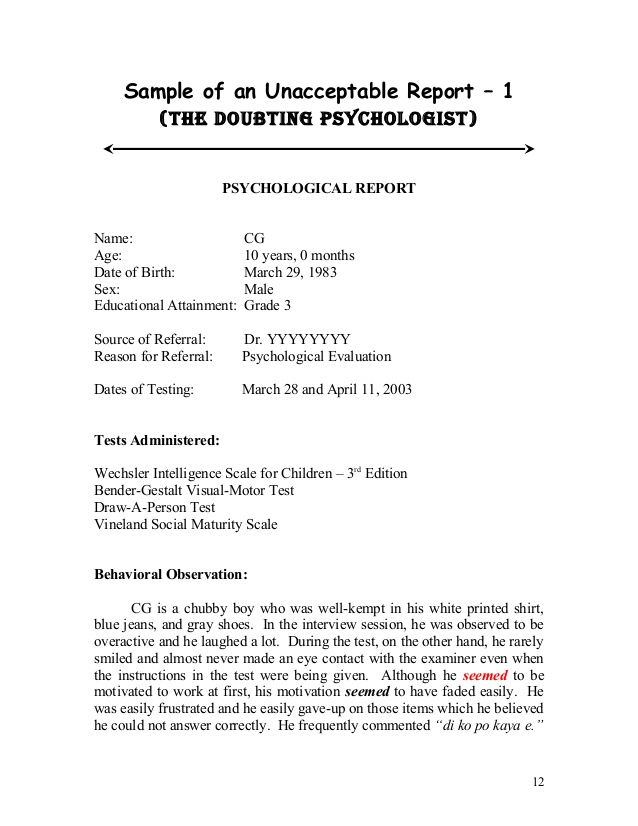

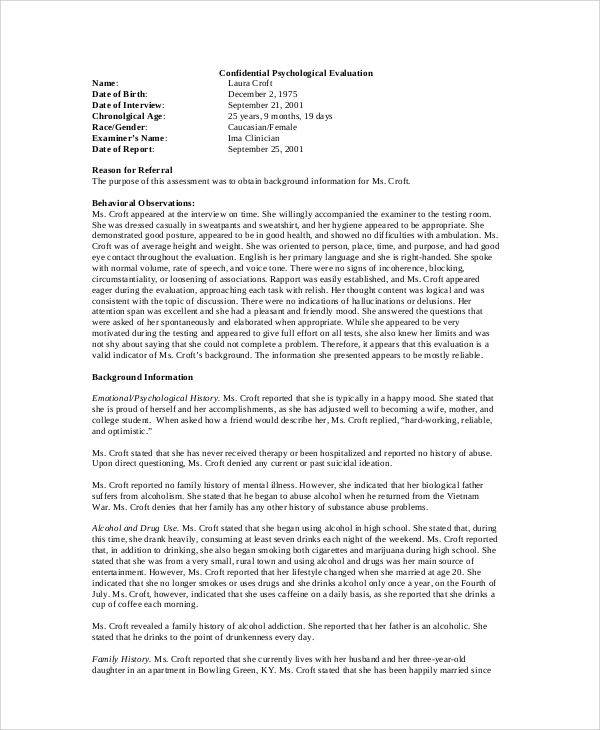

The physician usually receives the results of psychologic assessments in the form of a psychologic report. There are a variety of formats, so we will describe a typical one. The report will usually be about 2 to 3 typed pages, long enough to do the raw data justice but not so long as to impinge upon the valuable time of the physician. The first section will be a description of the presentation of the respondent and his or her test-taking behavior. The next section will describe the respondent's intellectual functioning, strengths and weaknesses, and the presence of organic symptoms. The third section is an overview of the respondent's current emotional and social functioning that may include samples of actual test responses as examples. In a final section, the psychologist summarizes the findings and offers recommendations. Interpretation of findings in psychologic test batteries largely depends on the clinical acumen of the psychologist. The organization and synthesis of test data require much skill and knowledge of personality dynamics. Each of the tests has a unique contribution to the overall clinical picture, but none can stand by itself. Thus, the psychologist must determine what is relevant, what is internally consistent, and what is central or irrelevant to diagnosis and intervention.

The third section is an overview of the respondent's current emotional and social functioning that may include samples of actual test responses as examples. In a final section, the psychologist summarizes the findings and offers recommendations. Interpretation of findings in psychologic test batteries largely depends on the clinical acumen of the psychologist. The organization and synthesis of test data require much skill and knowledge of personality dynamics. Each of the tests has a unique contribution to the overall clinical picture, but none can stand by itself. Thus, the psychologist must determine what is relevant, what is internally consistent, and what is central or irrelevant to diagnosis and intervention.

References

DeFilippis NA, McCampbell E. The manual for the Booklet Category Test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1979.

Exner JE. The Rorschach: a comprehensive system. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley, 1978.

*Freeman FS.

Theory and practice of psychological testing. New York: Holt, Rineholt & Winston, 1962.

Theory and practice of psychological testing. New York: Holt, Rineholt & Winston, 1962.Goldfried MR, Stricker G, Winer LB. Rorschach handbook of clinical and research applications. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1971.

Harrison R. Thematic Apperception Test. In: Wolman B, ed. Handbook of clinical psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965;562–620.

*Hathaway SR, McKinley JC. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory: users guide for the Minnesota report. University of Minnesota, 1982.

*Jarvis PE, Barth JT. Halstead-Reitan Test Battery: an interpretative guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1984.

*Korner AF. Theoretical considerations concerning the scope and limitations of projective techniques. In: Murstin BI, ed. Handbook of projective techniques. New York: Basic Books, 1960;23–24.

MacInnes WE, Forch JR, Golden CJ. A cross-validation of a booklet form of the Category Test.

Clin Neuropsychol. 1981;3:3–5.

Clin Neuropsychol. 1981;3:3–5.Mauger PA. Predicting response to treatment using the MMPI. In: Butcher J, Dahlstrom G, Gynther M, Schofield W, eds. Clinical notes on the MMPI. Nutley, NJ: Hoffman-LaRoche, 1980.

Reitan RM. Aphasia and sensory-perceptual deficits in adults. Tucson: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratories, 1984.

Rotter JB, Fafferty JE, Schachtitz E. Validating the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Test for college screening. In: Murstein BI, ed. Handbook of projective techniques. New York: Basic Books, 1960;859–72.

*Schneidman ES. Projective techniques. In: Wolman BB, ed. Handbook of clinical psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965;498–521.

Wechsler D. The WAIS-R manual. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1981.

Is This Test Good? How To Evaluate Psychological Tests

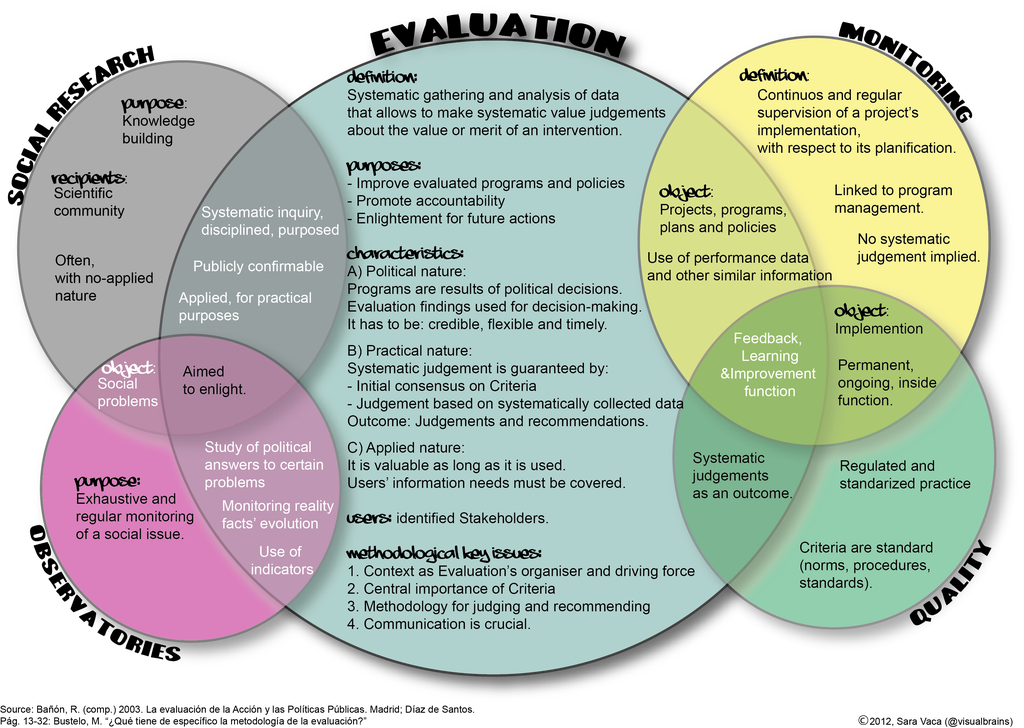

Psychological tests have become increasingly popular and influential. There are tests of intelligence and personality, along with tests designed to diagnose various mental disorders. Given the way that these tests are used (e.g., college admission and clinical treatment), it is critical that we understand how to evaluate the quality of a test.

Given the way that these tests are used (e.g., college admission and clinical treatment), it is critical that we understand how to evaluate the quality of a test.

But what makes a test good or bad?

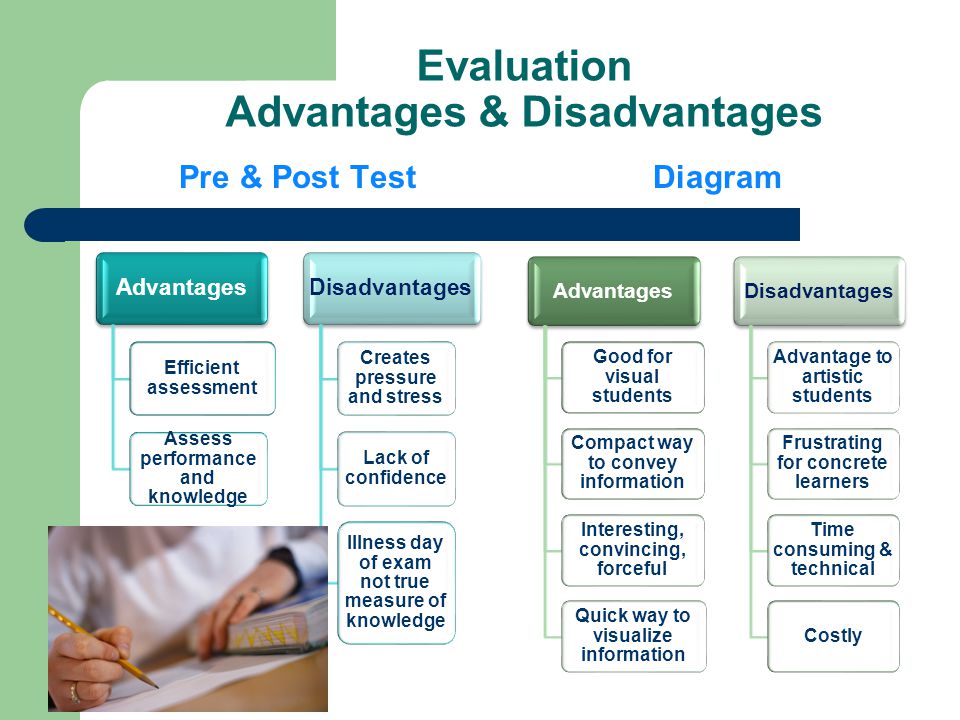

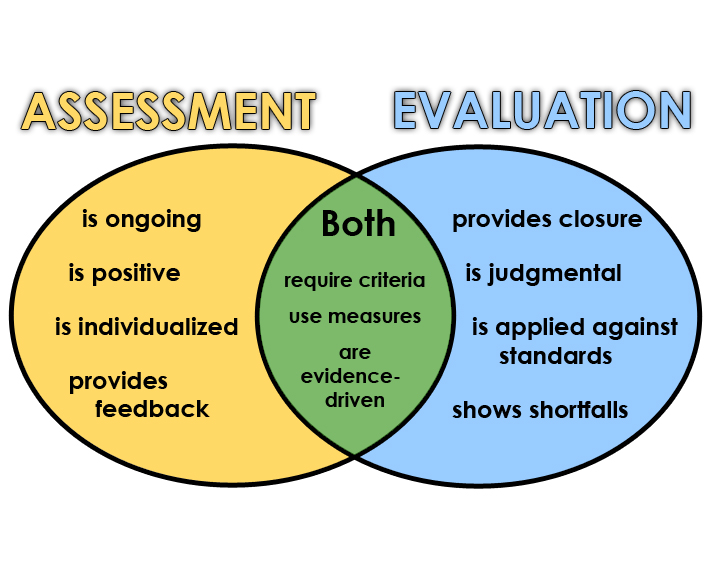

The simplest way to answer this question is to examine two questions:

- Does the test measure something accurately and consistently (the reliability question).

- Does the test measure what it says it measures (the validity question).

A good test is one that demonstrates high levels of reliability and validity.

Reliability

The reliability of a test is how accurately and consistently it measures something.

To give you an example, a ruler is a fairly reliable measure of length. If you measure how long a piece of paper is with a ruler, you are likely to get a fairly accurate and consistent result. That is, you should get a similar result each time you measure the paper.

In contrast, using your footsteps to measure the length of a corridor is not likely to be a reliable measure of length. There is no guarantee that each step you take is the same length, and if the corridor is not a whole number of steps long, then trying to divide your steps into smaller units (e.g., half a step or a quarter of a step) is far from precise.

There is no guarantee that each step you take is the same length, and if the corridor is not a whole number of steps long, then trying to divide your steps into smaller units (e.g., half a step or a quarter of a step) is far from precise.

In psychology, there are several common ways to assess the reliability of a test:

- Test-retest reliability

- Internal consistency (e.g., split-half reliability and Cronbach’s alpha)

- Alternate/parallel forms reliability

Test-retest reliability is the simplest form of reliability. You simply give people the test once and then give it to them again later. If the test has good reliability, people should receive similar scores on both occasions, barring some sort of change in the attribute being measured (e.g., if someone suffers a traumatic brain injury, you would not expect them to score equally well on an intelligence test before and after the injury).

One of the issues with test-retest reliability is that changes in the attribute being measured may occur. For example, if you measure someone’s height at the age of 27 and then again at the age of 30, there probably won’t be much difference. However, if you measure their height at 4 and then again at 7, there will be a significant change. When it comes to tests of intelligence and reasoning, practice and experience also tend to play a role as people often do better the second time around (both from general practice effects and from actually learning).

For example, if you measure someone’s height at the age of 27 and then again at the age of 30, there probably won’t be much difference. However, if you measure their height at 4 and then again at 7, there will be a significant change. When it comes to tests of intelligence and reasoning, practice and experience also tend to play a role as people often do better the second time around (both from general practice effects and from actually learning).

Internal consistency measures of reliability are interested in how well different items on a test measure the same thing. For example, if you have a test of extraversion, then the items in that test should all be measuring the same thing (extraversion). Therefore people’s scores on one item should be related to their scores on the other items.

The simplest way to get at this is using split-half reliability. What you do is you take a test and split in half (e.g., odd items and even items). You then compare people’s scores on one half to their scores on the other half. If a test is reliable, it should produce similar scores on both halves.

If a test is reliable, it should produce similar scores on both halves.

The problem with this approach is that there are multiple ways to split a test in half, so how do you know which way is the best? Cutting a test in half also tends to make it less reliable because there are fewer measurements being carried out (each item is essentially a measurement). The answer to both these problems is to use Cronbach’s alpha which essentially averages across all the different ways a test can be cut in half and adjusts for the length of the test. Indeed, Cronbach’s alpha is probably the most widely cited measure of reliability in psychological testing.

Alternate forms reliability is calculated by comparing different versions of a test to each other. For example, if you have a mathematics exam, you might have two versions that use different numbers in the problems. If the tests are reliable, people should score similarly on both versions.

The reliability of a test can range from 0 to 1. Here is a rough guideline:

Here is a rough guideline:

- 0.90+ = Fantastic

- 0.80 – 0.90 = Good

- 0.70 – 0.80 = Moderate

- 0.60 – 0.70 = Poor

- Less than 0.60 = Not suitable for anything except rough experimental work

If you’re going to use a psychological test, the first thing you should look at is its reliability. If it not a reliable test, then it’s not really measuring anything at all, and you’re basically wasting your time.

Validity

The validity of a test is how well a test measures what it says it measures. Notice that for a test to be valid, it must first be reliable because if a test doesn’t measure anything (i.e., it’s not reliable), then there’s no way it can measure what it says it does.

The validity of a test depends heavily on what it is being used for. A test can be a perfectly valid measure of personality, but if you try to use it measure intelligence, then it will fail miserably. Likewise a ruler is a valid measure of length and not a valid measure of weight (a scale would be a valid measure of weight but not a valid measure of length).

So how do we assess validity?

- Convergent validity

- Divergent validity

- Content validity

- Criterion-related validity

If a test has convergent validity, then scores on that test are related to scores on tests that they should be related to. For example, if you design a new intelligence test, then scores on that test should be highly correlated (i.e., strongly related) to scores on existing intelligence tests.

If a test has divergent validity, then scores on that test are not related to scores on tests they should not be related to. For instance, if you design a new intelligence test, then scores on that test should not be strongly correlated (i.e., not strongly related) to measures of shoe size since shoe size doesn’t have anything to do with intelligence.

In other words, scores on a test claiming to measure something should be related to other measures of that something (e..g, tests of extraversion should all be correlated to each other but not to something like eating speed).

Content validity is concerned with how well a test samples from the area it claims to measure. For example, if you’re giving twelfth graders a test that claims to be a comprehensive measure of their mathematical ability, then it has to cover more than just addition and subtraction because twelfth grade mathematics involves far more than those two operations. Likewise, a valid measure of overall personality needs to measure more than just extraversion. It should also measure other traits (e.g., conscientious, openness, etc.).

For a test to have criterion-related validity, it must be able to predict certain outcomes. For example, in a workplace situation, incoming employees might be given a placement test that compares them to current employees that have done well (this is called concurrent validity). Alternatively, employees might be given a test upon joining a company against which their later performance will be compared (this is called predictive validity).

Although measuring validity is not as straightforward as reliability, most forms of validity rely on correlations (i. e., how strongly related things are to each other). Correlations can range from -1.00 to +1.00. For forms of validity that want strong correlations, then a larger absolute value is better (i.e., farther from zero is better). For forms of validity that want weak/no correlations, then a smaller absolute value is better (i.e., closer to zero is better).

e., how strongly related things are to each other). Correlations can range from -1.00 to +1.00. For forms of validity that want strong correlations, then a larger absolute value is better (i.e., farther from zero is better). For forms of validity that want weak/no correlations, then a smaller absolute value is better (i.e., closer to zero is better).

For example, most measures of intelligence are strongly correlated with each other, which you would expect since they are all supposed to be measuring the same thing. In contrast, tests of intelligence tend not to be strongly correlated with tests of personality, which makes sense since intelligence and personality are not the same thing.

Overall

Reliability and validity are the two simplest ways to evaluate how good a test is. There are, of course, other ways, but understanding the reliability and validity of a particular test can tell you a lot about whether or not it’s trustworthy or worth using.

Reliability asks whether a test measures something accurately and consistently. Validity asks whether a test measures what it is supposed to measure. To be valid, a test must first be reliable. The best tests are those that show both high levels of reliability and high levels of validity.

Validity asks whether a test measures what it is supposed to measure. To be valid, a test must first be reliable. The best tests are those that show both high levels of reliability and high levels of validity.

If you want to read more about my thoughts on writing, education, and other topics, you can find those here.

I also write original fiction, which you can find here.

Like this:

Like Loading...

10 serious psychological tests that you can take on the Internet

January 26, 2021 A life

Questionnaires used by practicing psychologists will help you look deep into yourself. The main thing is not to try to make a diagnosis “by profile picture”.

1. Sondi test

The test is aimed at identifying psychological abnormalities. It consists of several stages. At each of them you will be shown portraits, from which you will need to choose the least and most pleasant in your opinion. nine0003

This testing method was developed by psychiatrist Leopold Szondi in 1947. The doctor noticed that in the clinic, patients communicated closer with those who had the same diseases. Of course, the Internet test will not give you a diagnosis - it will just help to detect some tendencies. Moreover, depending on the state of the psyche, the results will be different, so you can take the Szondi test in any incomprehensible situation.

The doctor noticed that in the clinic, patients communicated closer with those who had the same diseases. Of course, the Internet test will not give you a diagnosis - it will just help to detect some tendencies. Moreover, depending on the state of the psyche, the results will be different, so you can take the Szondi test in any incomprehensible situation.

Take the Test →

2. Beck Depression Scale

As the name suggests, this test measures how depressed you are. It takes into account the common symptoms and complaints of patients with this disease. When answering each question, you have to choose the closest one from several statements. nine0003

The test is worth taking even for those who are absolutely sure that they are healthy. Some of the statements in the questionnaire may seem strange to you, but many of them are true for a person with a disease. So if you think that depression is when someone is depressed from idleness, it's time to rethink your attitude.

Take the test →

3. Zang (Zung) scale for self-assessment of depression

Another test related to depression. It is shorter and easier to understand than the previous questionnaire. If you like an integrated approach in everything and are not ready to be content with the results of one test, you can combine them. nine0003

The author of this test is psychiatrist William Zang, also known in Russian psychology as William Tsung.

Take the test →

4. Beck Anxiety Scale

The test allows you to assess the severity of various phobias, panic attacks and other anxiety disorders. The results are not very telling. They will only tell you if you have reason to be concerned or not.

You are to read 21 statements and decide how true they are for you. nine0003

Take the test →

5. Luscher color test

This test helps to assess the psychological state through the subjective perception of color. Everything is very simple: from several colored rectangles, you first choose those that you like more, and then those that you like less.

Based on the results of the Luscher test, a specialist will be able to give recommendations on how to avoid stress, but you just look deeper inside yourself.

Take the test →

6. Projective test "Cube in the Desert"

This test looks less serious than the previous ones, and it really is. It consists of fantasy exercises. Few questions, but the result is simple and clear.

You will be asked to present a series of images, and then they will give you an interpretation of what you were imagining. This test, most likely, will not discover America, but will simply introduce you to the real you once again.

Take the test →

7. Eysenck's temperament test

You have to answer 70 questions to find out whether you are choleric, sanguine, phlegmatic or melancholic. At the same time, the test determines the level of extraversion, so you can find out if you are an introvert or just temporarily tired of people. nine0003

Take the test →

8.

Extended Leonhard-Shmishek test

Extended Leonhard-Shmishek test The test helps to reveal personality traits. The final grade is set on several scales, each of which reveals one or another aspect. Separately, it is checked whether you sincerely answered questions or tried to be better than you really are.

Pass the test →

9. Heck-Hess neurosis rapid diagnostic method

This scale will help determine the degree of probability of neurosis. If it is high, then it may be worth contacting a specialist. nine0003

Take the test →

10. Hall's Emotional Intelligence Test

Emotional intelligence is a person's ability to recognize the moods and feelings of others. To evaluate it, psychologist Nicholas Hall came up with a 30-question test.

Take the Test →

Also Read 🧐

- 11 Free Online Resources for Psychological Help

- Why you can't trust the results of psychological research

- The secret ingredient for extraordinary mental toughness

*Activities of Meta Platforms Inc. and its social networks Facebook and Instagram are prohibited in the territory of the Russian Federation.

and its social networks Facebook and Instagram are prohibited in the territory of the Russian Federation.

Online tests for employees, testing when hiring, psychological service for personnel assessment (Moscow)

Tests for employees online, testing when hiring, psychological service for personnel assessment (Moscow)ht-lab.ru

Home

psytest.ht-lab.ru

nine0002 Testsproftest.ht-lab.ru

Knowledge tests

analytics.ht-lab.ru

Analytics

expert.ht-lab.ru

Test Assessment

+7 (495) 669-67-19

Request a call

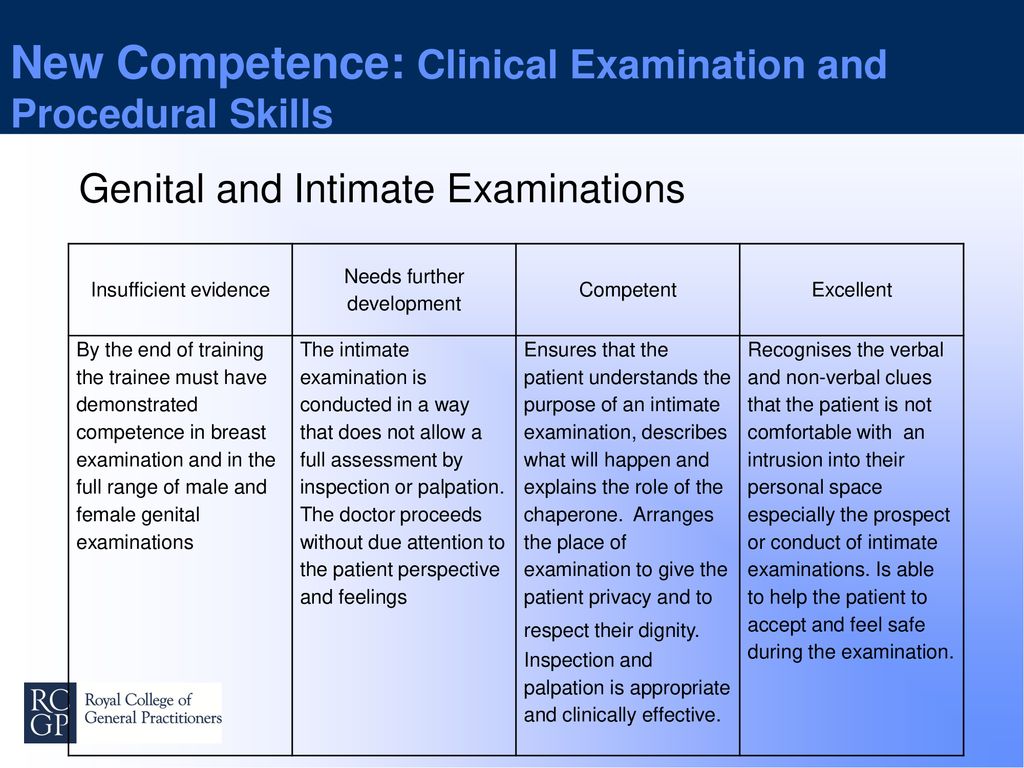

Among the existing assessment procedures tests are the most objective and at the same time the most cost-effective assessment tool . Our platform is not a panacea for personnel assessment, but in the hands of a specialist it is a tool that allows you to assess what is inaccessible to observation and significantly reduce the scale of more expensive assessment procedures. nine0003

nine0003

For more than a quarter of a century, the Laboratory has been representing the Russian school of psychometrics and testology , developing psychological tests and introducing test technologies into HR practice. Experience in the development and application of testing has shown that only an integrated approach in the assessment of guarantees the maximum diagnostic accuracy .

Using a rich arsenal of proven in-house developed diagnostic tools and applying an integrated approach to diagnostics, we are able to flexibly approach the solution of any specific task for the selection and evaluation of personnel for companies.

Our tests are used in recruitment, including for mass selection. It is also possible to pass online with the included proctoring service.

Router

Test-connections is a product of synthesis of "test-elements" that evaluate individual and psychological characteristics of a person from different angles.