Ending therapy the meaning of termination

Ending Therapy | Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy

Termination of the Therapy Relationship

As with all relationships, a therapeutic relationship has a beginning and an end. The end of a therapeutic relationship often offers an opportunity for the therapist and client to engage in the termination process, which can include looking back on the course of treatment, helping the client plan ahead and saying goodbye.

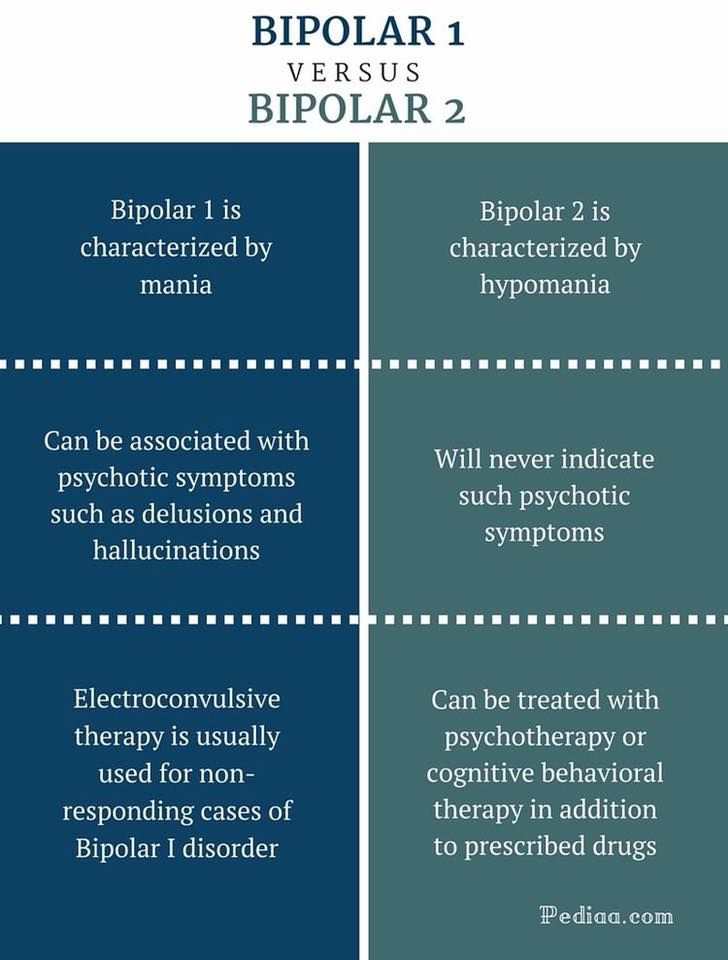

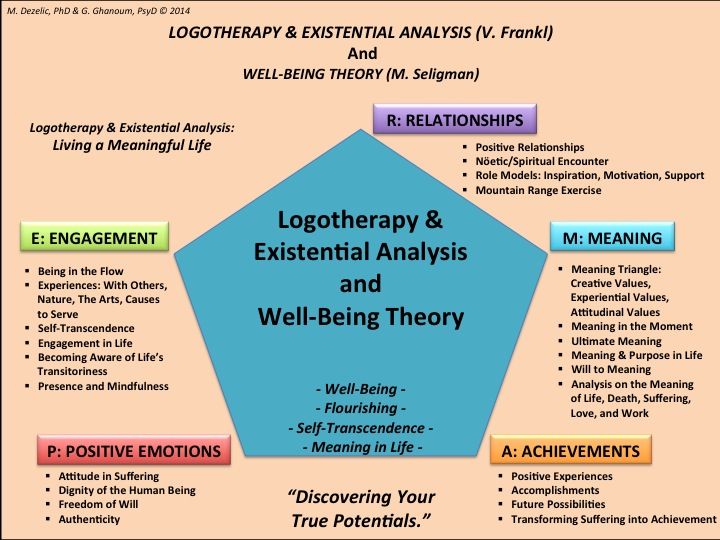

Although recognized as important, the termination of therapy has not received the empirical attention it deserves. However, results from a few studies (e.g. Quintana & Holahan, 1992; Knox, Adrians, Everson, Hess, Hill & Crook-Lyon, 2011; Marx & Gelso, 1987) do offer some support for two theoretical perspectives on therapeutic endings. The first, termination-as-loss perspective, is rooted in psychodynamic theories and describes the termination of psychotherapy as a significant loss for the client and emphasizes the importance of working through this loss in therapy (Mann, 1973; Strupp & Binder, 1985).

The second, termination-as-transformation perspective (Quintana, 1993; Maples & Walker, 2014), emphasizes termination as a time for internalizing growth and transforming the therapeutic relationship by providing clients with new insights about themselves and the therapeutic relationship. Related to both these perspectives, a body of research also offers support for the importance of the therapeutic relationship during the termination phase (Knox et al., 2011; Fragkiadaki & Strauss, 2012).

Studying the Termination Phase

Intrigued by the therapeutic relationship at the end of therapy, Charles J. Gelso and I examined therapists’ perceptions of three elements of the therapeutic relationship (i.e. the working alliance, real relationship and transference) during the termination phase in a recent study (Bhatia & Gelso, 2017). Following the widely used definition by Bordin (1979), the working alliance was conceptualized in terms of the working bond and the agreement of tasks and goals between the therapist and the client. Gelso (2011) defined the real relationship as the personal bond between the therapist and the client, characterized by the extent to which the therapist and client are genuine with each other and perceive each other realistically, and this conception of the real relationship was used in the study. Transference was conceptualized as the client’s experience of the therapist based on the client’s past experiences and involving a displacement of feelings, attitudes and behaviors rooted in earlier significant relationships onto the therapist (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012).

Gelso (2011) defined the real relationship as the personal bond between the therapist and the client, characterized by the extent to which the therapist and client are genuine with each other and perceive each other realistically, and this conception of the real relationship was used in the study. Transference was conceptualized as the client’s experience of the therapist based on the client’s past experiences and involving a displacement of feelings, attitudes and behaviors rooted in earlier significant relationships onto the therapist (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012).

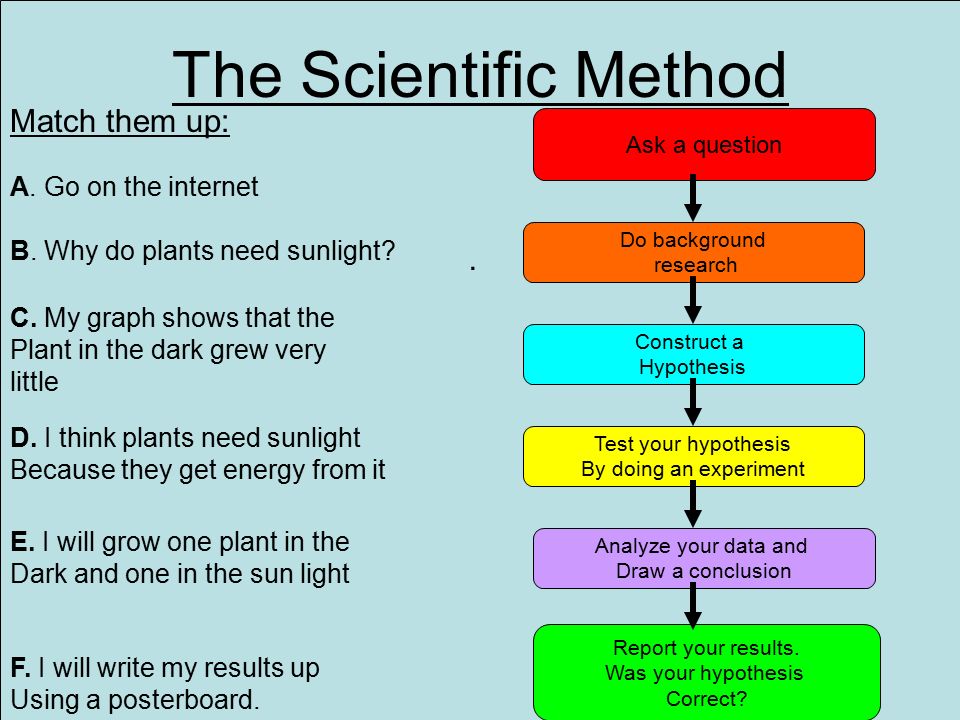

We used the following questions to guide our research; from the therapist’s point of view, how much time is spent in the termination phase? How do therapist perceptions of working alliance, real relationship and transference during the termination phase relate to the success of the overall treatment and the effectiveness of the termination phase? How do therapist perceptions of client sensitivity to loss associate with transference during the termination phase?

Our sample consisted of 233 licensed therapists in the U. S. of varying theoretical orientations. Therapists participating in the study identified a termination phase of treatment in their work with a client. The termination phase was defined as, “the last phase of counseling, during which the therapist and client consciously or unconsciously work toward bringing the treatment to an end” (Gelso & Woodhouse, 2002, pp. 346). Thus, at the outset, the findings and implications of the study do not address therapeutic endings that occur without warning and/or client dropouts. The major findings of the study and recommendations for clinical practice are discussed below.

S. of varying theoretical orientations. Therapists participating in the study identified a termination phase of treatment in their work with a client. The termination phase was defined as, “the last phase of counseling, during which the therapist and client consciously or unconsciously work toward bringing the treatment to an end” (Gelso & Woodhouse, 2002, pp. 346). Thus, at the outset, the findings and implications of the study do not address therapeutic endings that occur without warning and/or client dropouts. The major findings of the study and recommendations for clinical practice are discussed below.

Key Findings

The following key findings emerged from the results of the aforementioned study:

- Therapists reported the number of sessions included in the termination phase, as well as the total number of sessions included in treatment. Results indicated that the percentage of time spent on termination was approximately 17 percent of the total number of sessions.

- Examination of therapist ratings of termination phase evaluations and overall treatment outcome revealed that the success of the termination phase correlated with the success of overall treatment to a moderate extent (r=.30, p<.01).

- Therapist ratings of the working alliance and the real relationship during the termination phase correlated positively with termination phase evaluation and overall treatment outcome. In a regression model with the therapy relationship elements examined together, only the working alliance significantly predicted overall treatment outcome, highlighting its unique contribution to overall treatment outcome.

- Therapist ratings of transference (including both positive and negative transference) were positively associated with therapist ratings of perceived client sensitivity to loss.

Suggestions for Therapeutic Work in the Termination Phase

How can the results of the study inform therapeutic work? I offer below suggestions to consider during the termination phase. It is important to note here that these suggestions are not direct guidelines emerging from the results of the study; rather they are based on possible interpretations of the findings of this study, as well as on clinical impressions in therapeutic work. These recommendations need to be considered along with a theoretical understanding of individual cases in treatment.

It is important to note here that these suggestions are not direct guidelines emerging from the results of the study; rather they are based on possible interpretations of the findings of this study, as well as on clinical impressions in therapeutic work. These recommendations need to be considered along with a theoretical understanding of individual cases in treatment.

Spending time on termination

As per therapist reports, the average percentage of time spent on bringing treatment to an end by talking about termination was found to be approximately 17 percent of the total number of sessions, a number similar to the 16.67 percent reported by Gelso and Woodhouse (2002) in their review of termination literature. Perhaps this number can provide a rough estimate of the time to be spent on bringing treatment to a close (although more research in this realm is certainly needed).

Effectiveness of the termination phase

From the therapist’s perspective, a successful termination phase is related to better overall treatment outcome, and yet termination phase evaluations also appear to be distinct from overall treatment outcome. This finding is in line with Joyce, Piper, Ogrodniczuk, and Klien’s (2007) suggestion that the outcomes of the termination phase differ from overall treatment outcomes. In treatment then, there appears to be value in the therapist tending to the client’s experience of the termination phase, perhaps by exploring client satisfaction with the termination phase and reflecting upon the therapeutic work being done during the termination phase, over and above overall treatment outcomes.

This finding is in line with Joyce, Piper, Ogrodniczuk, and Klien’s (2007) suggestion that the outcomes of the termination phase differ from overall treatment outcomes. In treatment then, there appears to be value in the therapist tending to the client’s experience of the termination phase, perhaps by exploring client satisfaction with the termination phase and reflecting upon the therapeutic work being done during the termination phase, over and above overall treatment outcomes.

The working alliance during the termination phase

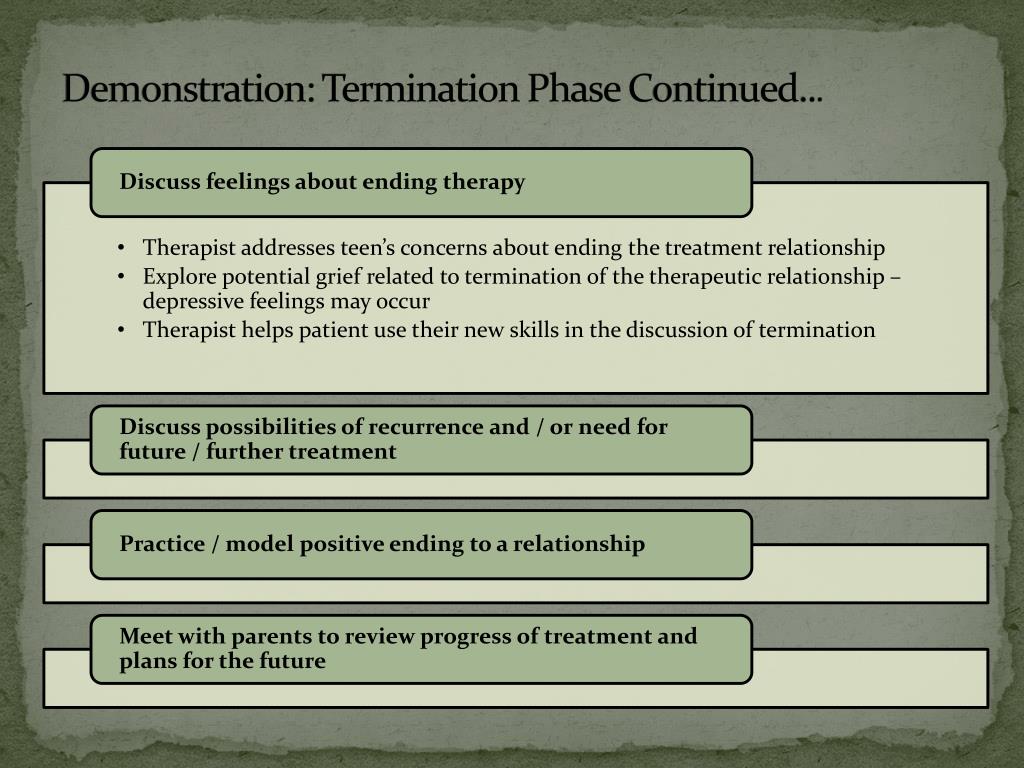

Therapist reports reveal that the role of the alliance is particularly important during the termination phase. In light of this finding, it seems helpful to revisit the alliance and bring it to the forefront of therapeutic work during the termination phase. For example, consolidating and discussing treatment goals, a component of the working alliance, can be an important component of the termination process (Norcross, Zimmerman, Greenberg & Swift, 2017). It may also help to discuss goals pertaining specifically to the termination phase to strengthen the alliance during the termination phase. For instance, in therapeutic work with a client expressing difficulty with ending relationships, the therapist and client may determine together to work through the end of the therapeutic relationship by providing a space for the client to mourn and express feelings about the ending.

It may also help to discuss goals pertaining specifically to the termination phase to strengthen the alliance during the termination phase. For instance, in therapeutic work with a client expressing difficulty with ending relationships, the therapist and client may determine together to work through the end of the therapeutic relationship by providing a space for the client to mourn and express feelings about the ending.

The real relationship during the termination phase

The strength of the personal bond between the therapist and the client during the termination phase also relates to good outcomes. Thus, it would benefit therapists to pay attention to the real relationship during the termination phase. Therapists can use the following questions to reflect on the strength of the real relationship; is there a real and personal relationship between the client and I, over and above a professional relationship? Am I able to understand and express what I truly feel about my client? Does my client appear to be sharing vulnerable material with me? These are just a few examples of questions that might provide insight into the strength of the real relationship (see Gelso, 2011).

Transference during the termination phase

Given the positive relationship between perceived client sensitivity to loss and transference, it appears valuable for therapists to be particularly attuned to the transference during the termination phase in the context of the client’s previous loss experiences. How transference is dealt with in therapeutic work often depends on theoretical orientation (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012), however, it appears that clients may experience feelings towards the therapist at the end of treatment as a result of previous losses across theoretical orientations. These feelings seem to be both positive and negative, at least in the eyes of the therapist, and not necessarily related to negative outcomes. Tending to transference, both positive and negative in valence, would likely represent areas of meaningful therapeutic work during termination.

Summary

To conclude, the termination phase in therapeutic work offers a unique opportunity to reflect on the ending relationship and to process the ending in the context of previous losses. Key implications for therapists include tending to the working alliance, real relationship and transference during the termination phase and evaluating the effectiveness of the termination phase of therapeutic work.

Key implications for therapists include tending to the working alliance, real relationship and transference during the termination phase and evaluating the effectiveness of the termination phase of therapeutic work.

+24

-9

Ending the Therapeutic Relationship-Avoiding Abandonment · NASWCANEWS.ORG

By Elizabeth M. Felton, JD, LICSW, Associate Counsel and Carolyn I. Polowy, JD, General Counsel

© March 2015. National Association of Social Workers. All rights reserved.

Social workers’ therapeutic relationships with their clients eventually come to an end. However, the way they end and how the social worker handles terminations can have ethical and legal implications.

This article will address some of the more common issues that may arise during termination and ways to enhance client care while avoiding allegations of abandonment.

Termination

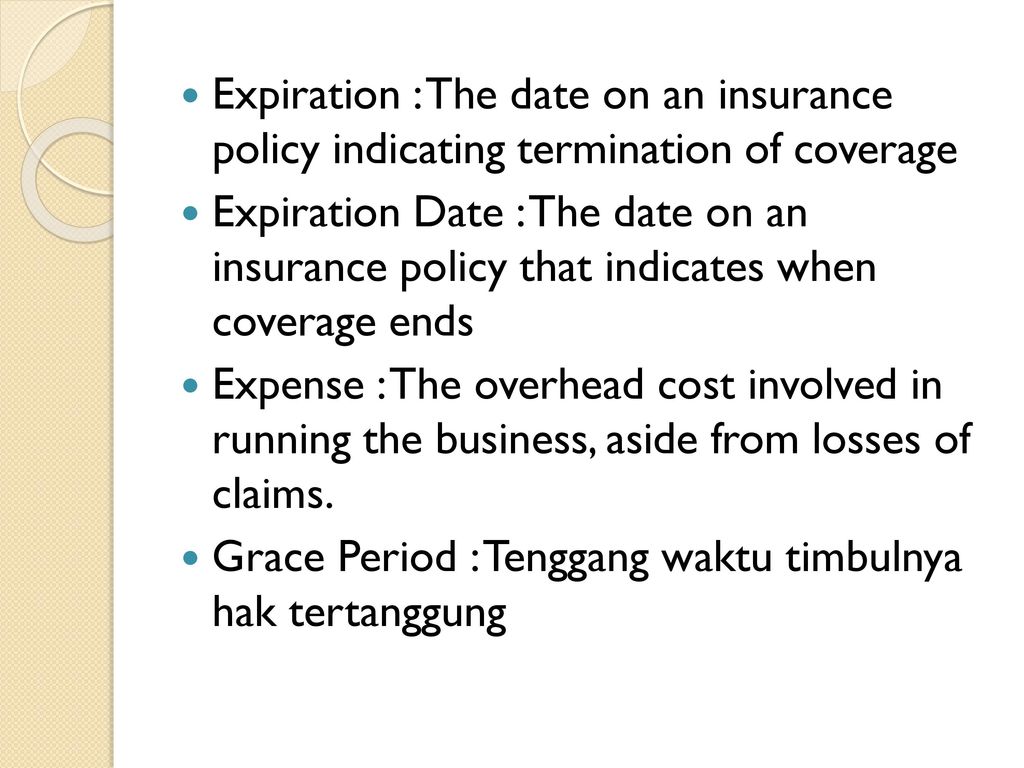

Social workers should assess a client’s ongoing treatment needs prior to initiating termination. The NASW Social Work Dictionary defines termination as: “The conclusion of the social worker –client intervention process; a systematic procedure for disengaging the working relationship. It occurs when goals are reached, when the specified time for working has ended, or when the client is no longer interested in continuing. Termination often includes evaluating the progress toward goal achievement, working through resistance, denial, and flight into illness. The termination phase also includes discussions about how to anticipate and resolve future problems and how to find additional resources to call on as future needs indicate.[1]”

The NASW Social Work Dictionary defines termination as: “The conclusion of the social worker –client intervention process; a systematic procedure for disengaging the working relationship. It occurs when goals are reached, when the specified time for working has ended, or when the client is no longer interested in continuing. Termination often includes evaluating the progress toward goal achievement, working through resistance, denial, and flight into illness. The termination phase also includes discussions about how to anticipate and resolve future problems and how to find additional resources to call on as future needs indicate.[1]”

There are many reasons why therapy ends. A client may terminate at any time for any reason. Ideally, termination occurs once the client and therapist agree that the treatment goals have been met or sufficient progress has been made and/or the client improves and no longer needs clinical services. However, there are many valid reasons that are discussed below as to why the therapist-client relationship may end the treatment before it is completed. Some of those reasons include:

Some of those reasons include:

- Client has mental health needs that are beyond the social worker’s area of expertise. For example, the client requires a different level of treatment (e.g., inpatient or crisis intervention) or more specialized treatment (e.g., trauma or substance abuse) than the social worker provides in the practice setting.

- Therapist is unable or unwilling, for appropriate reasons, to continue to provide care (e.g., therapist is retiring/closing practice or client threatened therapist with violence).

- Conflict of interest is identified after treatment begins.

- Client fails to make adequate progress toward treatment goals or fails to comply with treatment recommendations.

- Client fails to participate in therapy (e.g., non-compliance, no shows, or cancellations).

- Lack of communication/contact from the client.

It is recommended that therapists have a final session with their clients to review the overall progress before ending therapy, but sometimes this cannot happen, e. g., when the client stops communicating with the therapist. It is suggested that therapists create a policy for their practice so that cases are routinely closed after a certain amount of time without any contact from a client, for example: “If I do not have contact or communication from you for a period of xxxx days, I will assume that you no longer intend to remain active in this therapeutic relationship and your case will be closed. You can return to therapy in the future if you decide to continue treatment.”

g., when the client stops communicating with the therapist. It is suggested that therapists create a policy for their practice so that cases are routinely closed after a certain amount of time without any contact from a client, for example: “If I do not have contact or communication from you for a period of xxxx days, I will assume that you no longer intend to remain active in this therapeutic relationship and your case will be closed. You can return to therapy in the future if you decide to continue treatment.”

One way to establish that timeframe is to think about how long you want to be the therapist of record without seeing a client.

- Non-payment of agreed upon fees:

Before a social worker terminates for non-payment, the following criteria should be met:

- The financial contractual arrangements have been made clear to the client, preferably in writing.

- The client does not pose an imminent danger to self or others.

- The clinical and other consequences of the non-payment (i.

e., disruption of treatment/interruption of services) have been discussed with the client. NASW Code of Ethics, 1.16c

e., disruption of treatment/interruption of services) have been discussed with the client. NASW Code of Ethics, 1.16c

Certain circumstances may support a delay of the termination. For instance, it is not recommended that a therapist end treatment with a client who is in crisis at the time termination is being considered. A social worker has a responsibility to see that clinical services are made available when a client is in crisis. Postponing termination is preferred, if possible, until steps are in place to handle the crisis.

Abandonment

Abandonment is a specific form of malpractice that can occur in the context of a mental health professional’s termination of services. Abandonment, also referred to as ‘premature termination,’ occurs when a social worker is unavailable or precipitously discontinues service to a client who is in need.

In a malpractice case based on abandonment, the client alleges that the therapist was providing treatment and then unilaterally terminated treatment improperly. The client must show that he was directly harmed by the abandonment and that the harm resulted in a compensable injury. The client’s dissatisfaction with the outcome is not sufficient to establish the therapist’s negligence. The client must also show that the termination was not his fault, e.g., that he kept his appointments, complied with treatment recommendations, and paid his bills.[2]

The client must show that he was directly harmed by the abandonment and that the harm resulted in a compensable injury. The client’s dissatisfaction with the outcome is not sufficient to establish the therapist’s negligence. The client must also show that the termination was not his fault, e.g., that he kept his appointments, complied with treatment recommendations, and paid his bills.[2]

It is critical to be able to establish both the reason for termination and the manner in which it is carried out. After beginning a therapeutic relationship with a client, a social worker must not terminate therapy abruptly without referring the client to another mental health practitioner. If the social worker does not properly terminate the client-therapist relationship, the social worker exposes himself to allegations of abandonment which could lead to a lawsuit, a complaint to the state licensing board, or a request for professional review by the NASW Ethics Committee.[3] Proper termination that has been documented is a defense to abandonment allegations, and it supports good client care.

The NASW Code of Ethics addresses the issue of termination of services in 1.16:

1.16 Termination of Services

(a) Social workers should terminate services to clients and professional relationships with them when such services and relationships are no longer required or no longer serve the clients’ needs or interests.

(b) Social workers should take reasonable steps to avoid abandoning clients who are still in need of services. Social workers should withdraw services precipitously only under unusual circumstances, giving careful consideration to all factors in the situation and taking care to minimize possible adverse effects. Social workers should assist in making appropriate arrangements for continuation of services when necessary.

(c) Social workers in fee-for-service settings may terminate services to clients who are not paying an overdue balance if the financial contractual arrangements have been made clear to the client, if the client does not pose an imminent danger to self or others, and if the clinical and other consequences of the current nonpayment have been addressed and discussed with the client.

(d) Social workers should not terminate services to pursue a social, financial, or sexual relationship with a client.

(e) Social workers who anticipate the termination or interruption of services to clients should notify clients promptly and seek the transfer, referral, or continuation of services in relation to the clients’ needs and preferences.

(f) Social workers who are leaving an employment setting should inform clients of appropriate options for the continuation of services and of the benefits and risks of the options.

For more information, see NASW Code of Ethics.

Tips for Termination

- Prepare for termination from the beginning. Termination should be discussed early so both parties can have a number of sessions to discuss ending therapy.

- If continued treatment is needed, provide referrals to several mental health professionals, with addresses and phone numbers. Three referrals is the “rule of thumb” minimum.

If possible and with the client’s consent, assist in the transition to other health care providers.

If possible and with the client’s consent, assist in the transition to other health care providers. - Conduct the final session face -to-face, if possible. Avoid ending with a text, in an email or with a voicemail message.

- Make sure the client understands when, why and how therapy will be terminated.

- Document discussions about termination.

- Formalize the termination with a personalized termination letter (not a form letter).

What to include in a termination letter?

It is good practice for a social worker to draft a termination of treatment letter to every client once treatment has ended, regardless of the reason, to formally end the therapeutic relationship. This provides clarity to the client, and it helps avoid any implication that the social worker has an ongoing therapeutic responsibility. The termination letter would be in the form of a business letter and include:

- Client’s name

- Date treatment began

- Effective date of termination

- State the reason(s) for the termination.

(e.g., treatment goals have been met, client’s needs are beyond the scope of social’s workers practice or area of expertise, non-compliance with treatment recommendations, therapist is retiring/closing practice)

(e.g., treatment goals have been met, client’s needs are beyond the scope of social’s workers practice or area of expertise, non-compliance with treatment recommendations, therapist is retiring/closing practice) - Summary of treatment, including whether you feel further treatment is recommended

- If continued treatment is needed, provide three referrals to mental health professionals, with contact information

- Present the letter in person during a session or send it with delivery tracking and confirmation of service and/or certified return receipt

- Retain a copy of the letter and delivery documentation in the client’s file

- Mark the letter “confidential”

- Don’t mention confidential therapeutic treatment information

Conclusion

Addressing the termination of treatment is an important phase of the therapeutic process. For termination to be handled properly, discussions between the social worker and client should occur in advance and be addressed in a thoughtful and sensitive manner. It is best that clients not feel that they have been abandoned, for the sake of the client as well as the social worker. If continued treatment is needed, the social worker must make an effort to assist the client in obtaining ongoing services to ensure that these needs are adequately addressed. Proper documentation of the termination of the therapeutic relationship with the client will provide support for the social workers’ effort to meet the clients’ needs as treatment ends.

It is best that clients not feel that they have been abandoned, for the sake of the client as well as the social worker. If continued treatment is needed, the social worker must make an effort to assist the client in obtaining ongoing services to ensure that these needs are adequately addressed. Proper documentation of the termination of the therapeutic relationship with the client will provide support for the social workers’ effort to meet the clients’ needs as treatment ends.

Resources and References

Barbara A. Weiner, J.D. & Robert M. Wettstein, M.D., Legal Issues in Mental Health Care 164-165 (1993). “Codes of Ethics on Termination in Psychotherapy and Counseling,” Zuri Institute, Inc.

NASW Code of Ethics (2008)

Richard S. Leslie, J.D., Termination and Referral – When Does the Duty to the Patient End?, October 2008.

Robert L. Barker, NASW Social Work Dictionary 336, 433, (5th ed. 2003).

2003).

[1] Robert L. Barker, NASW Social Work Dictionary 433, (5th ed. 2003).

[2] Barbara A.Weiner, J.D. & Robert M. Wettstein, M.D., Legal Issues in Mental Health Care 164-165 (1993).

[3] Richard S. Leslie, J.D., Termination and Referral – When Does the Duty to the Patient End?, October 2008.

Staff

Website | + posts

Tags: Ending the Therapeutic Relationship-Avoiding AbandonmentLegal Issues

The end of the therapeutic relationship, or why we are afraid of clients leaving // Psychological newspaper

The ultimate goal of any psychotherapy is for the client to get along without it. One can hardly argue with this, but despite this so obvious fact, many psychoanalysts working in the transference space are extremely painful when a client leaves therapy. The end of a therapeutic relationship for many specialists is a topic filled with traumatic content, and its specificity lies in the fact that the only method of working through this problem is competent and regular supervision.

It is often a significant mistake for the psychotherapist to shift the focus of attention to the therapeutic process, which begins after the formation of a working alliance. What is often overlooked is the fact that such a fruitful interaction does not arise from a vacuum, but is the result of complex deep processes that contribute to the establishment of a connection between the client and the therapist, and then inevitably ends in separation. Do not forget that the main difference between psychotherapeutic relationships and friendship or love relationships is not only the presence of a strict setting framework, but also the finiteness of the communication process. Each session inevitably comes to an end, and sooner or later the therapy itself will be terminated. In a sense, the course of therapy can be compared with the cycles of development of civilizations within the framework of the biologization approach. Like human civilization, the therapeutic relationship can be thought of as a living being, developing and progressing. The stage of birth (beginning of therapy) is replaced by the stage of growing up (formation of a working alliance). Gradually, “growing up” through many crises leads to the heyday and the period of the greatest productivity of joint work. It is at this time that insights, insights appear, and soon after that the recession stage inevitably sets in. During this period, repeated crises are possible, the patient may be disappointed in the therapist, and often a negative therapeutic reaction leads to a break in the relationship. If the period of initiation of therapy is worked out in sufficient detail in preparation for work, then the completion of the therapeutic interaction is overlooked by many analysts. As a result, this area turns into the area of shadow contents of the psychotherapist, goes into the sphere of the repressed, and this problem can damage not only the professional identity of the psychoanalyst, but also the formation of a healthy identity in his clients.

The stage of birth (beginning of therapy) is replaced by the stage of growing up (formation of a working alliance). Gradually, “growing up” through many crises leads to the heyday and the period of the greatest productivity of joint work. It is at this time that insights, insights appear, and soon after that the recession stage inevitably sets in. During this period, repeated crises are possible, the patient may be disappointed in the therapist, and often a negative therapeutic reaction leads to a break in the relationship. If the period of initiation of therapy is worked out in sufficient detail in preparation for work, then the completion of the therapeutic interaction is overlooked by many analysts. As a result, this area turns into the area of shadow contents of the psychotherapist, goes into the sphere of the repressed, and this problem can damage not only the professional identity of the psychoanalyst, but also the formation of a healthy identity in his clients.

It is not uncommon to encounter situations in which the client's departure frightens and traumatizes the psychoanalyst so much that a symbiotic relationship is formed in place of a full-fledged psychotherapy. A painful interdependence of client and therapist is formed, a symbiotic relationship in therapy is strengthened and stimulated by both parties, and the result can be years and decades of fruitless analysis that gives the patient a sense of imaginary satisfaction, but does not satisfy his true needs and does not contribute to his full individuation.

A painful interdependence of client and therapist is formed, a symbiotic relationship in therapy is strengthened and stimulated by both parties, and the result can be years and decades of fruitless analysis that gives the patient a sense of imaginary satisfaction, but does not satisfy his true needs and does not contribute to his full individuation.

When it comes to the space of transference, one cannot help but recall that in analytic therapy parental transference takes place most often. The transference mother figure, embodied in the figure of the psychotherapist, has great power and considerable influence on the unconscious of the patient. Maternal transfer can contribute to a successful and healthy symbolic separation, thereby developing and strengthening the patient's ego-functioning, but at the same time, it can also become the basis of a protracted symbiotic relationship that does not at all contribute to individuation and the development of the internal qualities necessary for the client [8].

The end of therapy is an important stage in the analytic relationship that deserves close attention and has a serious symbolic significance. Every specialist needs to remember that any client will leave sooner or later. What matters is not the fact that he leaves, but how exactly he does it.

The Importance of the Therapeutic Setting

The conscious end of therapy by mutual agreement is an ideal variant of the end of the therapeutic relationship, after which the client enters the so-called post-analytic phase, which is important for his personal development. However, this is not always the case. Much more common is a traumatic termination of therapy, an unconscious exit from analytic interaction caused by a negative therapeutic reaction that has not been worked out within the framework of a working alliance, processes of acting out, the realization of any repressed contents that have not been transferred to the conscious sphere. Such an outcome is also dangerous because it often leads to the depreciation and leveling of a fairly large part of the success achieved. In the absence of supervision, the psychotherapist may face a serious crisis of professional identity, which, if not worked out, will lead to an insurmountable fear of leaving patients in the future [1].

In the absence of supervision, the psychotherapist may face a serious crisis of professional identity, which, if not worked out, will lead to an insurmountable fear of leaving patients in the future [1].

The setting or therapeutic contract is what partly prevents the outcome described above. The task of the setting is not to keep the client in therapy, but at a rational organizational level to prevent certain actions that will damage the client in the first place. Finally, the setting establishes the boundaries of reality, which allows the psychotherapist to always maintain a distance and avoid, if possible, the formation of a symbiotic therapeutic relationship [2].

Any social and organizational framework that the psychotherapist introduces at the very beginning of therapy is a guarantee of the security of the analytic space. At the beginning of therapy, when the therapist is not yet intimately familiar with the patient's unconscious and has no access to it, such an organizational framework provides a solid and effective basis for a further working alliance. In the therapeutic contract, the clause concerning the completion of work is of great importance. Often it is left without attention, but it should be conveyed to the client among the most significant conditions. The client must be aware that therapy can only be completed in person, by mutual agreement and after a certain number of closing sessions.

In the therapeutic contract, the clause concerning the completion of work is of great importance. Often it is left without attention, but it should be conveyed to the client among the most significant conditions. The client must be aware that therapy can only be completed in person, by mutual agreement and after a certain number of closing sessions.

When is it not recommended to quit?

• The least favorable outcome of any therapy is a kind of "boycott" and a demonstrative refusal to work on the part of the client in case of an unprocessed transference. Such withdrawal becomes the result of the work of the resistance mechanism, it becomes the last defense of the psyche that does not want to penetrate into traumatic contents, and it rarely has a positive prognosis [7].

• Care is undesirable if there is an unexplored or not fully voiced conflict with the therapist. Any conflict needs to be explored. In a situation of misunderstanding and any kind of confrontation, it is required to work out the conflict in the office, and only after that make a decision to leave.

• Another undesirable outcome is the withdrawal of a client who struggles with personal feelings for the therapist, feeling embarrassed and ashamed. The task of the therapist is to help the client express their feelings and discuss them in a safe way without violating the setting. Voicing these strong feelings for the therapist can be the start of really productive transference work.

Finally, any psychologist needs to remember that if the client does decide to leave, the psychologist has no right to keep him in therapy by force. Any manipulative actions and attempts to keep the client in a therapeutic relationship, especially in the presence of a formed symbiotic dependence, significantly worsen the situation and subjectively deprive the client of a sense of freedom and personal security [5].

End of therapy as symbolic separation

The therapist who tries to keep a departing client unwittingly turns into a controlling parent who, at his own discretion, wants to protect his offspring from self-destruction and escape. However, there are situations when this symbolic escape becomes the only way to separate from the symbolic parent figure, which can be embodied in the personality of the therapist [4].

However, there are situations when this symbolic escape becomes the only way to separate from the symbolic parent figure, which can be embodied in the personality of the therapist [4].

Separation is, perhaps, symbolically the process closest to completion of the analysis. Leaving the psychoanalyst by mutual conscious agreement or as a result of negative transference and devaluation, the client in any case parted with a significant figure. This separation always traumatizes him, as if he had been traumatized by the separation from his mother. At the same time, as in the case of separation from the mother figure, such a separation is both traumatic and liberating.

There are certain patterns of behavior of patients at the end of the analysis, depending on how well the real separation was passed in the real relationship of the patient with his parents during childhood and adolescence.

In particular, if the patient's relationship with the mother had delayed separation, and the mother did not let the child away from her without giving him freedom of action, the client will do his best to avoid the unpleasant and disturbing topic of separation. As a result, parting with the therapist can occur suddenly, as a result of a sharp devaluation of long-term joint work, accompanied by fear and guilt for the decision made independently. At the same time, in the relationship with the mother, the separation still remains unexplored: separation from the analyst is safe, it does not destroy the patient, which cannot be said about the all-consuming mother figure. In this way, the client escapes the realization that certain traumatic contents remain unprocessed.

As a result, parting with the therapist can occur suddenly, as a result of a sharp devaluation of long-term joint work, accompanied by fear and guilt for the decision made independently. At the same time, in the relationship with the mother, the separation still remains unexplored: separation from the analyst is safe, it does not destroy the patient, which cannot be said about the all-consuming mother figure. In this way, the client escapes the realization that certain traumatic contents remain unprocessed.

There are also situations in which intimacy with the mother was basically absent even in early childhood, if the mother was not empathic and accepting enough. Such patients avoid not so much separation as intimacy itself. Forming a working alliance in such cases is a long and laborious process. Intimacy is unknown to the patient, as is the feeling of empathy and trust. Leaving therapy is not perceived as something that leads to the loss of a valuable relationship, since the patient has not formed the experience of realizing this value. If, on the other hand, the therapist is faced with a situation in which the all-consuming mother has traumatized the child with destructive intimacy, any rapprochement will seem dangerous. At the slightest violation of the boundaries, the reaction can be withdrawal.

If, on the other hand, the therapist is faced with a situation in which the all-consuming mother has traumatized the child with destructive intimacy, any rapprochement will seem dangerous. At the slightest violation of the boundaries, the reaction can be withdrawal.

The narcissistic component is also important in the situation of completion of therapy. Clients with a significant narcissistic radical may leave therapy with a feeling of insignificance and of not living up to the expectations of a significant figure, alternating with a sense of superiority over the therapist.

It is very important that most of the most important traumatic contents, experiences, repressed fears and desires are voiced and worked through during the sessions. This will help to avoid unconscious and untimely termination of work and the depreciation of its results.

According to Sigmund Freud, an analysis can be considered naturally completed only if the patient has become aware of a sufficient amount of internal contents that cause resistance, and if the analyst is convinced that the client has been worked out to such an extent that he can not be afraid of a repetition of pathological processes. This does not guarantee that the patient will be protected from all sorts of further internal conflicts, however, in the view of the founder of psychoanalysis, it is an essential condition for a healthy final analysis [8].

This does not guarantee that the patient will be protected from all sorts of further internal conflicts, however, in the view of the founder of psychoanalysis, it is an essential condition for a healthy final analysis [8].

The end of therapy is always symbolic. In case of a successful outcome, the end becomes a joint summing up, and the client leaves with a feeling of gratitude, full of valuable experiences, and, no less important, with the knowledge that he can return at any moment, and he will be accepted, as if accepted in a parental home. This outcome is the symbolic embodiment of a healthy separation. If both the client and the therapist have been able to work through the resistance and transference points intelligently, the conclusion of the analysis will be experienced without psychological damage to both parties and will turn into a meaningful internal experience. If throughout the therapeutic interaction the client was forced to rely on the analyst, then after a healthy completion of therapy, he gets the opportunity to stand firmly on the ground, creatively transform reality, flexibly adapt to changes in the world around him independently, thanks to a strengthened ego.

If the patient's departure is traumatic: the most common mistakes

The most common mistake that causes many psychotherapists to panic about losing another patient is the desire to give him quick results on demand. Intrapsychic processes cannot be accelerated artificially, and logical interpretation does not help eliminate traumatic fixation or bring the repressed experience to consciousness. Work may be slow, and impatient clients may complain. The task of the psychotherapist is not to try with guilt to satisfy the client’s request at the moment “here and now” with all his might, but to help him work out his feelings of discontent, impatience, irritation.

There are patients who are not committed to long-term work. They strive to solve their problems quickly and painlessly, refusing any responsibility for the results of therapy. In this case, the therapist may also face a serious sense of guilt towards the departing patient, as the patient verbally or non-verbally accuses him of unfulfilled obligations and lack of professional competence. Here again it is worth recalling the framework of the setting, explaining which, the therapist must share the responsibility with the client. It is very important that the client realize that exactly half of the responsibility for the continued success of therapy lies with him.

Here again it is worth recalling the framework of the setting, explaining which, the therapist must share the responsibility with the client. It is very important that the client realize that exactly half of the responsibility for the continued success of therapy lies with him.

Finally, the essential mistake of the therapist is an unworked countertransference. The only way to avoid this is timely supervision of clinical cases. Supervision is an obligatory companion of a practicing psychotherapist, regardless of work experience and level of professionalism. It is equally necessary for both beginners and experienced psychologists who have been working successfully for many years. Only with the help of competent supervision can one recognize undeveloped transfer relationships in therapy, because of which there is an insurmountable fear of losing a client, protect oneself from professional burnout, and secure one's own professional identity.

Literature

1. Garcia H. End of analysis. From demanding love to giving. Three dreams and one gift // Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis. - 2007, No. 4.

Garcia H. End of analysis. From demanding love to giving. Three dreams and one gift // Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis. - 2007, No. 4.

2. Grinson R. Technique and practice of psychoanalysis. - Voronezh: NPO "MODEK", 1994. - 491 p.

3. Kahn Michael – Between therapist and client. New relationships. - St. Petersburg: B.S.K., 1997. - 148 p.

4. Kinodo J.M. Taming Loneliness: Separation Anxiety in Psychoanalysis. - M.: Kogito-Centre, 2008. - 254 p.

5. Sandler Joseph, Dar Christopher, Holder Alex. Patient and psychoanalyst: Fundamentals of the psychoanalytic process / transl. from English. - 2nd ed. - M.: Kogito-Centre, 2007. - 254 p.

6. Tome X., Kakhele X. Modern psychoanalysis: in 2 volumes - M., 1996.

7. Ferenczi Sh. Body and subconsciousness. Removal of prohibitions from sexuality. Series "Classics of Psychoanalysis" / trans. with him. - M.: NOTA BENE, 2003. - 362 p.

8. Freud Z. Finite and Infinite Analysis. – M.: MG Management, 1998. - 224 p.

– M.: MG Management, 1998. - 224 p.

9. Ferenczi, Sandor. The problem of the termination of the analysis // Final contributions to the problems and methods of psychoanalysis. (Michael Balint, Ed.; Eric Mosbacher, et al, Trans.). New York: Basic Books.

10. Holmes, Jeremy. Termination in Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: an Attachment Perspective. European Journal of Psychoanalysis/ Number 1 – 2014/1/ Electronic source: http://www.journal-psychoanalysis.eu/termination-in-psychoanalytic-psychotherapy-an-attachment-perspective-2/

Citation: Balabanova E.A. The End of Therapeutic Relationship or Why We Are Afraid of Clients Leaving // Clinical and Medical Psychology: Research, Training, Practice: Electron. scientific magazine - 2014. - N 2 (4) [Electronic resource]. – URL: http://medpsy.ru/climp (accessed: hh.mm.yyyy).

Source

Code of Ethics for a Psychologist

Preamble

- The Code of Ethics for a Psychologist of the Russian Psychological Society is drawn up in accordance with the Constitution of the Russian Federation, Federal Law of the Russian Federation No.

152-FZ of July 27, 2006 “On Personal Data”, the Charter of the Russian Psychological Society, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association "Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects", International Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles for Psychologists, Ethical Metacode of the European Federation of Psychological Associations .

152-FZ of July 27, 2006 “On Personal Data”, the Charter of the Russian Psychological Society, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association "Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects", International Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles for Psychologists, Ethical Metacode of the European Federation of Psychological Associations . - The Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society is the advisory and regulatory body of the Russian Psychological Society on the professional ethics of a psychologist.

- In this Code of Ethics, the term "Psychologist" refers to a person with a higher education in psychology.

- In this Code of Ethics, the term "Client" refers to a person, a group of persons or an organization who has agreed to be the object of psychological research for personal, scientific, industrial or social interests, or who personally turned to the Psychologist for psychological help.

- This Code of Ethics applies to all activities of psychologists defined by this Code of Ethics. This Code of Ethics applies to all forms of work of the Psychologist, including those carried out remotely or via the Internet.

- The professional activity of a psychologist is characterized by his special responsibility to clients, society and psychological science, and is based on the trust of society, which can only be achieved by observing the ethical principles of professional activity and behavior contained in this Code of Ethics.

- Code of Ethics for Psychologists serves: for internal regulation of the activities of the community of psychologists; to regulate the relationship of psychologists with society; the basis for the application of sanctions in case of violation of the ethical principles of professional activity.

I. Ethical principles of a psychologist

The work ethics of a psychologist is based on universal moral and ethical values. The ideals of the free and all-round development of the personality and its respect, the rapprochement of people, the creation of a just, humane, prosperous society are decisive for the activity of a psychologist. The ethical principles and rules of a psychologist's work formulate the conditions under which his professionalism, the humanity of his actions, respect for the people with whom he works, and under which the psychologist's efforts are of real benefit are preserved and strengthened.

The ideals of the free and all-round development of the personality and its respect, the rapprochement of people, the creation of a just, humane, prosperous society are decisive for the activity of a psychologist. The ethical principles and rules of a psychologist's work formulate the conditions under which his professionalism, the humanity of his actions, respect for the people with whom he works, and under which the psychologist's efforts are of real benefit are preserved and strengthened.

- The principle of respect

The psychologist proceeds from respect for personal dignity, human rights and freedoms proclaimed and guaranteed by the Constitution of the Russian Federation and international documents on human rights.

The principle of respect includes : - Respect for the dignity, rights and freedoms of the individual

- A psychologist treats people with equal respect regardless of their age, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, belonging to a certain culture, ethnic group and race, religion, language, socioeconomic status, physical abilities and other grounds.

- Impartiality of the Psychologist does not allow a biased attitude towards the Client. All actions of the Psychologist in relation to the Client must be based on data obtained by scientific methods. The subjective impression that the Psychologist has when communicating with the Client, as well as the social position of the Client, should not have any influence on the conclusions and actions of the Psychologist.

- The Psychologist avoids activities that may lead to discrimination of the Client on any grounds.

- The psychologist should organize his work in such a way that neither its process nor its results harm the health and social status of the Client and persons associated with him.

- A psychologist treats people with equal respect regardless of their age, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, belonging to a certain culture, ethnic group and race, religion, language, socioeconomic status, physical abilities and other grounds.

- Privacy

- Information obtained by the Psychologist in the process of working with the Client on the basis of a trusting relationship is not subject to intentional or accidental disclosure outside the agreed conditions.

- Research results must be presented in such a way that they cannot compromise the Client, the Psychologist or psychological science.

- Psychodiagnostic data of students obtained during their studies must be treated confidentially. Client information must also be treated confidentially.

- By demonstrating specific cases of his work, the Psychologist must ensure that the dignity and well-being of the Client is protected.

- The Psychologist should not look for information about the Client that goes beyond the professional tasks of the Psychologist.

- The Client has the right to consult a Psychologist or work with him without the presence of third parties.

- Uncontrolled storage of research data may harm the Client, the Psychologist and society as a whole. The procedure for handling the data obtained in research and the procedure for their storage should be strictly regulated.

- Information obtained by the Psychologist in the process of working with the Client on the basis of a trusting relationship is not subject to intentional or accidental disclosure outside the agreed conditions.

- Awareness and voluntary consent of the Client

- The client must be informed about the purpose of the work, about the methods used and ways of using the information received. Work with the Client is allowed only after the Client has given informed consent to participate in it. In the event that the Client is not able to make a decision on his participation in the work himself, such a decision must be made by his legal representatives.

- The Psychologist must inform the Client of all major steps or treatments. In the case of inpatient treatment, the Psychologist must inform the Client about the possible risks and about alternative methods of treatment, including non-psychological ones.

- Video or audio recordings of a consultation or treatment can only be made by the Psychologist after he has received the Client's consent to do so. This provision also applies to telephone conversations.

Acquaintance of third parties with video, audio recordings of consultations and telephone conversations can be allowed by the Psychologist only after obtaining consent to this from the Client.

Acquaintance of third parties with video, audio recordings of consultations and telephone conversations can be allowed by the Psychologist only after obtaining consent to this from the Client. - Participation in psychological experiments and research must be voluntary. The client must be informed in a form understandable to him about the goals, features of the study and the possible risk, discomfort or undesirable consequences, so that he can independently decide on cooperation with the Psychologist. The psychologist is obliged to make sure in advance that the dignity and personality of the Client will not be affected. The Psychologist must take all necessary precautions to ensure the safety and well-being of the Client and to minimize the possibility of unforeseen risk.

- Where prior exhaustive disclosure is contrary to the objectives of the study being conducted, the Psychologist must take special precautions to ensure the welfare of the subjects.

Where possible, and provided that the information communicated will not harm the Client, all clarifications must be made after the end of the experiment.

Where possible, and provided that the information communicated will not harm the Client, all clarifications must be made after the end of the experiment.

- Customer self-determination

- The Psychologist recognizes the Client's right to maximum autonomy and self-determination, including the general right to enter into and end a professional relationship with the Psychologist.

- Any person can be a client in case of undoubted legal capacity due to age, state of health, mental development, physical independence. In case of insufficient legal capacity of a person, the decision on his cooperation with the Psychologist is made by a person representing the interests of this person under the law.

- The psychologist must not interfere with the Client's desire to involve another psychologist for consultation (in cases where there are no legal contraindications to this).

- Principle of competence

The psychologist must strive to ensure and maintain a high level of competence in his work, as well as to recognize the limits of his competence and his experience. The psychologist should provide only those services and use only those methods in which he has been trained and experienced.

The principle of competence includes : - Knowledge of professional ethics

- A psychologist must have a thorough knowledge of professional ethics and must be familiar with the provisions of this Code of Ethics. In his work, the Psychologist must be guided by ethical principles.

- If staff or students act as experimenters in the conduct of psychodiagnostic procedures, the Psychologist must ensure, regardless of their own responsibility, that their actions comply with professional requirements.

- The psychologist is responsible for the conformity of the professional level of the personnel he supervises with the requirements of the work performed and this Code of Ethics.

- In his working contacts with representatives of other professions, the Psychologist must show loyalty, tolerance and readiness to help.

- Limitations of professional competence

- A psychologist is obliged to carry out practical activities within his own competence, based on his education and experience.

- Only the Psychologist carries out direct (questionnaire, interviewing, testing, electrophysiological research, psychotherapy, training, etc.) or indirect (biographical method, observation method, study of the products of the Client's activity, etc.) work with the Client.

- The Psychologist must master the methods of psychodiagnostic conversation, observation, psychological and pedagogical influence at a level sufficient to maintain the Client's feeling of sympathy, trust and satisfaction from communicating with the Psychologist.

- If the Client is ill, then work with him is allowed only with the permission of the doctor or the consent of other persons representing the interests of the Client.

- Restrictions on the means used

- The psychologist can apply methods that are adequate to the objectives of the study, age, gender, education, condition of the Client, the conditions of the experiment. Psychodiagnostic methods, in addition, must be standardized, normalized, reliable, valid and adapted to the contingent of subjects.

- The psychologist must apply scientifically recognized methods of processing and interpreting data. The choice of methods should not be determined by the Psychologist's scientific predilections, his social hobbies, personal sympathy for Clients of a certain type, social status or professional activity.

- A psychologist is prohibited from presenting deliberately distorted primary data, deliberately false and incorrect information in the results of the study.

If the Psychologist discovers a significant error in his research after the research has been published, he must take all possible steps to correct the error and further publish the corrections.

If the Psychologist discovers a significant error in his research after the research has been published, he must take all possible steps to correct the error and further publish the corrections.

- Professional development

- A psychologist must constantly improve his professional competence and his awareness of the ethics of psychological work (research).

- Impossibility of professional activity under certain conditions

- If any circumstances force the Psychologist to terminate work with the Client prematurely and this may adversely affect the Client's condition, the Psychologist must ensure that work with the Client continues.

- A psychologist should not perform his professional activities when his abilities or judgment are adversely affected.

- Liability principle

The psychologist must be mindful of his professional and scientific obligations to his clients, to the professional community and to society as a whole. The psychologist must strive to avoid causing harm, must be held accountable for his actions, and must ensure, as far as possible, that his services are not abusive.

The psychologist must strive to avoid causing harm, must be held accountable for his actions, and must ensure, as far as possible, that his services are not abusive.

Liability principle includes : - Primary responsibility

- The Psychologist's decision to undertake a research project or intervention assumes responsibility for possible scientific and social consequences, including the impact on individuals, groups and organizations involved in the research or intervention, as well as indirect effects, such as the influence of scientific psychology on public opinion and on the development of ideas about social values.

- The psychologist must be aware of the specifics of interaction with the Client and the responsibility arising from this. The responsibility is especially great if the subjects or clients are persons suffering from drug dependence or persons with disabilities, as well as if the research or intervention program purposefully limits the Client's legal capacity.

- If the Psychologist concludes that his actions will not improve the Client's condition or pose a risk to the Client, he must stop the intervention.

- Doing no harm

- The psychologist uses only such methods of research or intervention that are not dangerous to the health, condition of the Client, do not represent the Client in the results of the study in a false, distorted light, and do not provide information about those psychological properties and characteristics of the Client that are not related to specific and agreed tasks of psychological research.

- Solving ethical dilemmas

- The psychologist must be aware of the possibility of ethical dilemmas and be personally responsible for their solution. Psychologists consult on these issues with their colleagues and other significant persons, and also inform them of the principles reflected in the Code of Ethics.

- If the Psychologist has ethical questions in connection with his work, he should contact the Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society for advice.

- The psychologist must be aware of the possibility of ethical dilemmas and be personally responsible for their solution. Psychologists consult on these issues with their colleagues and other significant persons, and also inform them of the principles reflected in the Code of Ethics.

- Integrity

The psychologist should strive to promote the openness of science, learning and practice in psychology. In this activity, the psychologist must be honest, fair and respectful of his colleagues. The psychologist should clearly represent his professional tasks and the functions corresponding to these tasks.

Integrity includes : - Awareness of the limits of personal and professional opportunities

- A psychologist must be aware of the limitations of both his own possibilities and the possibilities of his profession. This is a condition for establishing a dialogue between professionals of various specialties.

- Honesty

- The Psychologist and the Client (or the party initiating and paying for psychological services for the Client) before entering into an agreement, agree on remuneration and other significant conditions of work, such as the distribution of rights and obligations between the Psychologist and the Client (or the party paying for psychological services) or the storage procedure and application of research results.

The psychologist must notify the Client or employer that his activities are primarily subject to professional and not commercial principles.

When hiring, the Psychologist must notify his employer that:

- within the limits of his competence, he will act independently;

- he is obliged to observe the principle of confidentiality: this is required by law;

- professional management of his work can only be carried out by a psychologist;

– it is impossible for him to fulfill non-professional requirements or requirements that violate this Code of Ethics.

When hiring a Psychologist, the employer must receive the text of this Code of Ethics. - Public dissemination of information about the services provided by the Psychologist serves the purpose of making an informed decision by potential Clients about entering into a professional relationship with the Psychologist.

Such advertising is acceptable only if it does not contain false or distorted information, reflects objective information about the services provided, and complies with the rules of decency.

Such advertising is acceptable only if it does not contain false or distorted information, reflects objective information about the services provided, and complies with the rules of decency. - A psychologist is prohibited from organizing advertising for himself or any particular intervention or treatment. Advertising for the purpose of competition must under no circumstances deceive potential Clients. The psychologist should not exaggerate the effectiveness of his services, make claims of the superiority of his professional skills and applied methods, and also give guarantees of the effectiveness of the services provided.

- A Psychologist is not permitted to offer a discount or reward for referring Clients to him, or enter into agreements with third parties for this purpose.

- The Psychologist and the Client (or the party initiating and paying for psychological services for the Client) before entering into an agreement, agree on remuneration and other significant conditions of work, such as the distribution of rights and obligations between the Psychologist and the Client (or the party paying for psychological services) or the storage procedure and application of research results.

- Directness and openness

- The psychologist must be responsible for the information he provides and avoid distorting it in research and practice.

- The psychologist formulates the results of the study in terms and concepts accepted in psychological science, confirming his conclusions by presenting the primary materials of the study, their mathematical and statistical processing and the positive conclusion of competent colleagues. When solving any psychological problems, research is carried out, always based on a preliminary analysis of the literature data on the question posed.

- In the event of a distortion of information, the psychologist must inform the participants of the interaction about this and re-establish the degree of trust.

- The psychologist must be responsible for the information he provides and avoid distorting it in research and practice.

- Avoidance of conflicts of interest

- The psychologist must be aware of the problems that can arise as a result of dual relationships. The psychologist should try to avoid relationships that lead to conflicts of interest or exploitation of the relationship with the Client for personal gain.

- A psychologist must not use professional relationships for personal, religious, political or ideological interests.

- The Psychologist must be aware that a conflict of interest may arise after the formal termination of the Psychologist's relationship with the Client. The psychologist in this case also bears professional responsibility.

- The Psychologist must not enter into any kind of personal relationship with his Clients.

- The psychologist must be aware of the problems that can arise as a result of dual relationships. The psychologist should try to avoid relationships that lead to conflicts of interest or exploitation of the relationship with the Client for personal gain.

- Responsibility and openness to the professional community

- The results of psychological research should be made available to the scientific community. The possibility of misinterpretation must be prevented by correct, complete and unambiguous presentation. Data about participants in the experiment must be anonymous. Discussions and criticism in scientific circles serve the development of science and should not be hindered.

- A psychologist must respect his colleagues and must not criticize their professional actions in an unbiased manner.

- The psychologist must not, by his actions, contribute to the displacement of a colleague from his sphere of activity or deprivation of his work.

- If the Psychologist believes that his colleague is acting unprofessionally, he must point this out to him in confidence.

- The results of psychological research should be made available to the scientific community. The possibility of misinterpretation must be prevented by correct, complete and unambiguous presentation. Data about participants in the experiment must be anonymous. Discussions and criticism in scientific circles serve the development of science and should not be hindered.

II. Violation of the Psychologist's Code of Ethics

- Violation of the Psychologist's Code of Ethics includes ignoring the provisions set out in it, misinterpreting them, or intentionally violating them. Violation of the Code of Ethics may be the subject of a complaint.

- A complaint about a violation of the Psychologist's Code of Ethics can be submitted to the Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society in writing by any individual or legal entity.

Consideration of complaints and making decisions on them is carried out in accordance with the established procedure by the Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society.

Consideration of complaints and making decisions on them is carried out in accordance with the established procedure by the Ethics Committee of the Russian Psychological Society. - Sanctions applied to a Psychologist who has violated the Code of Ethics may include: a warning on behalf of the Russian Psychological Society (public censure), suspension of membership in the Russian Psychological Society, accompanied by broad information to the public and potential clients about the exclusion of this specialist from the current register of RPO psychologists . Information about the sanctions applied is publicly available and is transferred to professional psychological associations in other countries.

- In case of serious violations of the Code of Ethics, the Russian Psychological Society may apply to bring the Psychologist to court.

This Psychologist's Code of Ethics was adopted on February 14, 2012 V Congress of the Russian Psychological Society.