Dsm 5 insomnia criteria

The DSM-5 Criteria for Diagnosing I Psych Central

Challenges with falling asleep, staying asleep, or returning to sleep are symptoms listed in the DSM 5 as the criteria of a sleep-wake disorder known as insomnia.

Almost everyone experiences periods of disrupted sleep. Worry, changes in your daily activity or routine, and temperature are all common things that can prevent a restful night.

One night of poor sleep doesn’t mean you’re living with insomnia.

But when the inability to sleep becomes a pattern over time, you may be experiencing a sleep disorder.

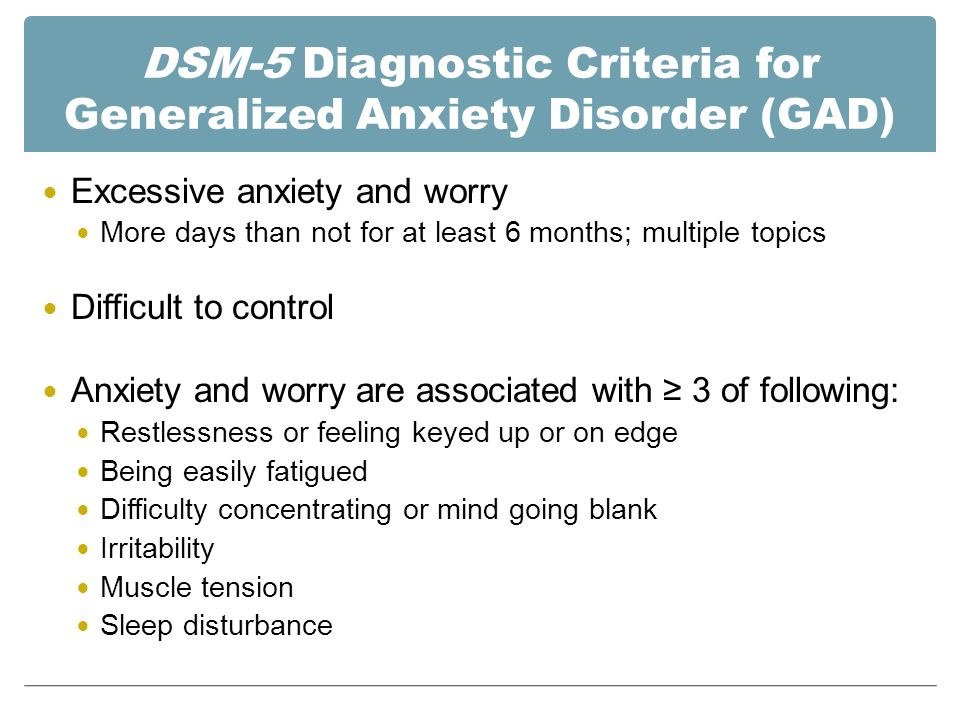

Insomnia is listed as a sleep-wake disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, revised text (DSM-5-TR). The condition has three primary symptoms.

- Challenges falling asleep (onset insomnia): inability to fall asleep beyond 20-30 minutes

- Inability to maintain sleep (middle insomnia): frequent waking during the night after sleep onset beyond 20-30 minutes, and difficulty returning to sleep after mid-night waking

- Early-morning wakefulness (late insomnia): waking at least 30 minutes before the desired time and before sleep reaches 6.

5 hours (often accompanied by an inability to resume sleep at all)

While only these symptoms are present in the DSM-5-TR for insomnia, how those symptoms present and how long you experience them are important for determining whether you have the condition.

Because not everyone requires the same amount of sleep, a healthcare or mental health professional will take into account what your ideal sleep duration may be, based on factors such as your past sleep history, age, and activity level.

Under a DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis, insomnia sleep disturbances are those that impact your daily function and negatively affect you socially, occupationally, or in other important areas of life.

Other DSM-5-TR insomnia disorder criteria necessary for diagnosis include:

- sleep difficulty is present at least 3 nights per week and for a period of at least 3 months

- you’re unable to sleep even with ample opportunity

- no other sleep-wake disorder, substance, or coexisting mental health condition explains the insomnia experience

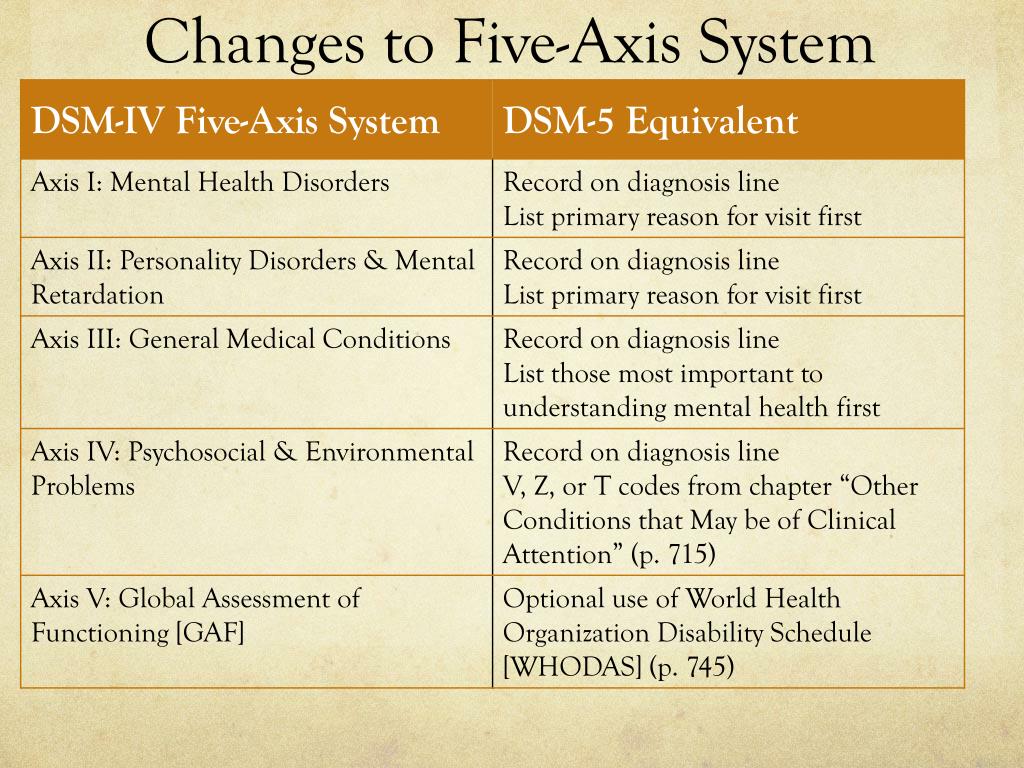

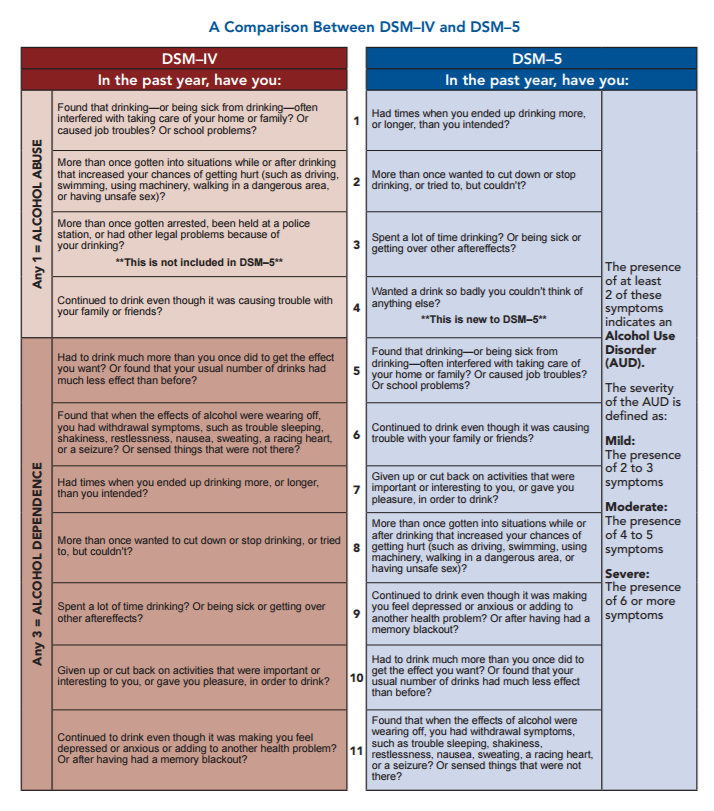

DSM-IV-TR vs.

DSM-5-TR

DSM-5-TRInsomnia disorder was included in the DSM-IV-TR, the version of the DSM that predates the DSM-5-TR.

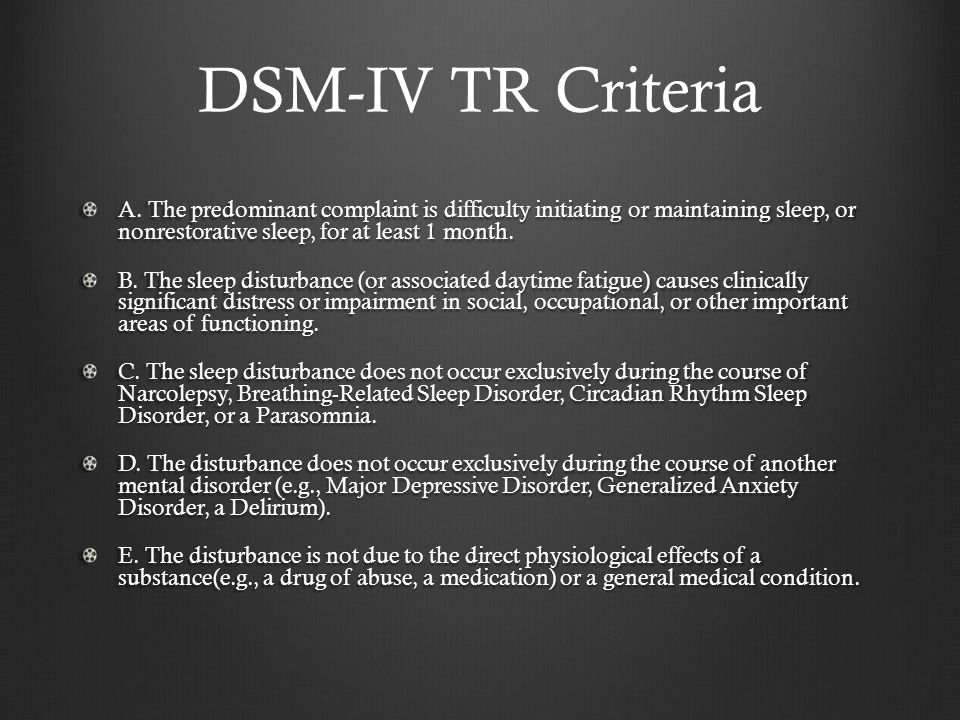

In the DSM-IV-TR, insomnia was less defined. Instead of early-morning waking as a symptom, the DSM-IV-TR listed “nonrestorative sleep” as a primary symptom.

The duration of the experience was also vague in the DSM-IV-TR. For a diagnosis, symptoms had to be present for a period of 1 month.

The DSM-5-TR elaborated on the experience of insomnia, stating that it occurred at least 3 nights a week, happened even under ideal circumstances, and was present for a period of at least 3 months.

If any of those criteria weren’t met or posed exceptions to the rule, specifiers were added to include more subtypes of insomnia disorder.

Insomnia disorder can come with diagnostic specifiers. Specifiers are conditions noted in the DSM-5-TR that set one presentation of insomnia apart from another.

In general, insomnia occurs in two forms:

- short term

- chronic

Short-term insomnia

Short-term insomnia, listed in the DSM-5-TR as episodic insomnia, lasts for at least 1 month but less than 3 months.

Chronic insomnia

Chronic insomnia is often listed as insomnia that lasts beyond 3 months. The DSM-5-TR breaks it down into two additional categories:

- persistent (lasting 3 months or longer)

- recurrent (two or more episodes within a single year)

Several other specifiers can be added to an insomnia disorder diagnosis such as:

- with non-sleep disorder mental comorbidity (occurring alongside another condition, including substance use disorder)

- with other sleep disorders

- with another medical comorbidity (occurring alongside a physical condition)

Other specified insomnia

Several diagnoses in the DSM-5-TR include a category of “other specified” or “unspecified.”

This specifier is used when you’re experiencing almost all the symptoms of a condition, or a mixed bag of symptoms, that can’t clearly be grouped under an existing diagnosis.

If your symptoms are causing you distress but don’t meet the full criteria for an insomnia diagnosis, a healthcare or mental health professional may use this identifier moving forward.

There are other reasons you might receive an unspecified DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis.

Situational insomnia, aka acute insomnia, is recognized by the DSM-5-TR as insomnia symptoms that meet all the criteria except the minimum duration requirement.

This form of insomnia is often related to life events or sleep schedule changes.

Another reason for an unspecified diagnosis may be the presence of only nonrestorative sleep. This symptom was originally listed in the DSM-IV-TR as a primary symptom of insomnia disorder.

While it’s no longer included as part of the DSM-5-TR criteria, experiencing only nonrestorative sleep for an extended period of time may warrant a diagnosis of “other specified insomnia” if no other condition is identified as the cause.

Insomnia as a feature vs. a diagnosis

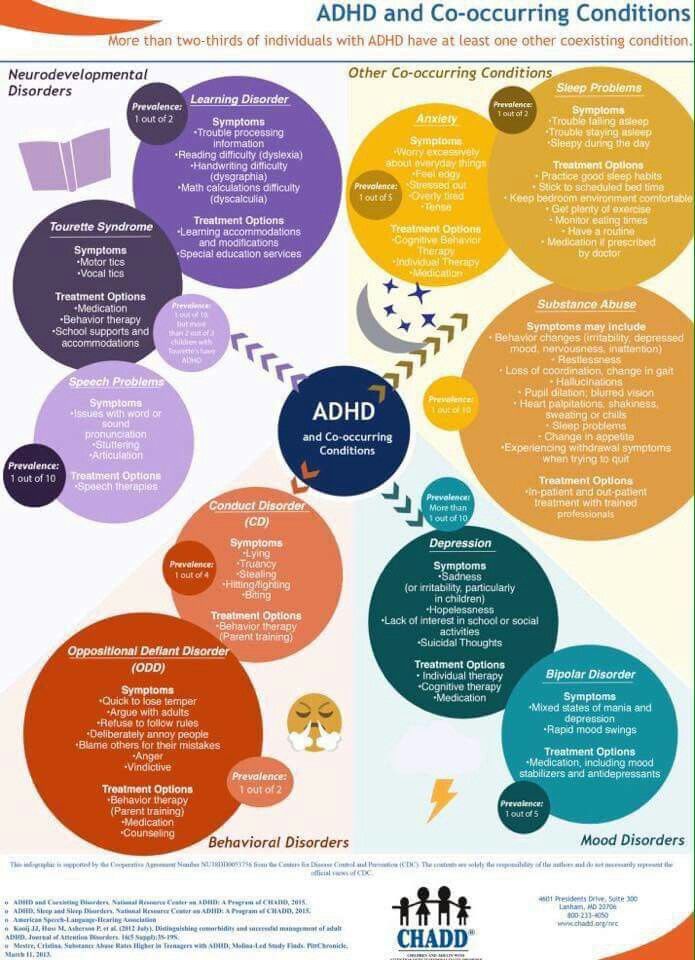

Insomnia can be both an independent diagnosis and a feature of other mental and physical conditions.

As a feature, insomnia represents challenges in sleeping but may not meet the full diagnostic criteria of a disorder.

When you’re living with insomnia disorder, your symptoms meet the sleep disturbance descriptions as well as the outlined time frames and levels of impairment cited in the DSM-5-TR.

If you’ve received a DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis, your primary symptoms will involve at least one of the following:

- difficulty falling asleep

- challenges maintaining sleep

- inability to fall back asleep after an early-morning wake up

These three symptoms define an insomnia diagnosis, regardless of type. How those symptoms manifest in your daily life is often unique.

You may experience:

- daytime sleepiness

- fatigue

- irritability

- mood fluctuations

- declining work or school performance

- difficulty concentrating

- lack of focus

- memory lapses

- erratic sleep schedules

- excessive napping

- spending more time in bed

- preoccupation with being unable to sleep

- decreased energy

- anxiety

- depression

- emotional reactivity

- muscle pain

- headache

- gastrointestinal upset

Several factors can influence how insomnia affects your thoughts and actions. If you’re living with insomnia disorder and major depressive disorder, for example, you may find symptoms of low mood are more prevalent for you.

If you’re living with insomnia disorder and major depressive disorder, for example, you may find symptoms of low mood are more prevalent for you.

Not everyone shows symptoms that directly reflect the severity of sleep disturbance.

You may experience insomnia for years, most nights of the week, but outwardly show minimal signs to those around you.

The DSM-5-TR lists several sleep disorders in addition to insomnia. This includes:

- hypersomnolence disorder

- narcolepsy

- obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea

- central sleep apnea

- sleep-related hypoventilation

- circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders

- non-rapid eye movement sleep arousal disorders

- nightmare disorder

- rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

- restless legs syndrome

- substance or medication-induced sleep disorder

- parasomnias

- other or unspecified sleep disorder

All these sleep disorders have their own criteria that set them apart from insomnia.

For many of them, specific sleep challenges are essential to the diagnosis and are the dominant feature even if insomnia is present.

For example, central sleep apnea involves breathing patterns that are critical to the diagnosis. Similarly, restless legs syndrome has symptoms specific to leg sensations and movement that aren’t part of the diagnostic criteria for insomnia.

Insomnia can be an independent condition or a feature of another primary condition. It’s characterized by challenges with falling asleep, staying asleep, and resuming sleep in the mornings.

When you live with insomnia, sleeplessness is often only one of the tell-tale signs. Irritability, trouble concentrating, and physical aches and pains can all be a part of the insomnia experience.

Insomnia is often treatable. It may improve as other co-occurring conditions improve, and it may lessen in severity with treatment and lifestyle changes.

To learn more about insomnia disorder, treatment, or where to find support, you can visit:

- American Sleep Association

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research

- Better Sleep Council

- Find a sleep therapist through the Anxiety & Depression Association of America

If you’re wondering if you may have a sleep disorder, consider taking our sleep quiz.

The DSM-5 Criteria for Diagnosing I Psych Central

Challenges with falling asleep, staying asleep, or returning to sleep are symptoms listed in the DSM 5 as the criteria of a sleep-wake disorder known as insomnia.

Almost everyone experiences periods of disrupted sleep. Worry, changes in your daily activity or routine, and temperature are all common things that can prevent a restful night.

One night of poor sleep doesn’t mean you’re living with insomnia.

But when the inability to sleep becomes a pattern over time, you may be experiencing a sleep disorder.

Insomnia is listed as a sleep-wake disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, revised text (DSM-5-TR). The condition has three primary symptoms.

- Challenges falling asleep (onset insomnia): inability to fall asleep beyond 20-30 minutes

- Inability to maintain sleep (middle insomnia): frequent waking during the night after sleep onset beyond 20-30 minutes, and difficulty returning to sleep after mid-night waking

- Early-morning wakefulness (late insomnia): waking at least 30 minutes before the desired time and before sleep reaches 6.

5 hours (often accompanied by an inability to resume sleep at all)

5 hours (often accompanied by an inability to resume sleep at all)

While only these symptoms are present in the DSM-5-TR for insomnia, how those symptoms present and how long you experience them are important for determining whether you have the condition.

Because not everyone requires the same amount of sleep, a healthcare or mental health professional will take into account what your ideal sleep duration may be, based on factors such as your past sleep history, age, and activity level.

Under a DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis, insomnia sleep disturbances are those that impact your daily function and negatively affect you socially, occupationally, or in other important areas of life.

Other DSM-5-TR insomnia disorder criteria necessary for diagnosis include:

- sleep difficulty is present at least 3 nights per week and for a period of at least 3 months

- you’re unable to sleep even with ample opportunity

- no other sleep-wake disorder, substance, or coexisting mental health condition explains the insomnia experience

DSM-IV-TR vs.

DSM-5-TR

DSM-5-TRInsomnia disorder was included in the DSM-IV-TR, the version of the DSM that predates the DSM-5-TR.

In the DSM-IV-TR, insomnia was less defined. Instead of early-morning waking as a symptom, the DSM-IV-TR listed “nonrestorative sleep” as a primary symptom.

The duration of the experience was also vague in the DSM-IV-TR. For a diagnosis, symptoms had to be present for a period of 1 month.

The DSM-5-TR elaborated on the experience of insomnia, stating that it occurred at least 3 nights a week, happened even under ideal circumstances, and was present for a period of at least 3 months.

If any of those criteria weren’t met or posed exceptions to the rule, specifiers were added to include more subtypes of insomnia disorder.

Insomnia disorder can come with diagnostic specifiers. Specifiers are conditions noted in the DSM-5-TR that set one presentation of insomnia apart from another.

In general, insomnia occurs in two forms:

- short term

- chronic

Short-term insomnia

Short-term insomnia, listed in the DSM-5-TR as episodic insomnia, lasts for at least 1 month but less than 3 months.

Chronic insomnia

Chronic insomnia is often listed as insomnia that lasts beyond 3 months. The DSM-5-TR breaks it down into two additional categories:

- persistent (lasting 3 months or longer)

- recurrent (two or more episodes within a single year)

Several other specifiers can be added to an insomnia disorder diagnosis such as:

- with non-sleep disorder mental comorbidity (occurring alongside another condition, including substance use disorder)

- with other sleep disorders

- with another medical comorbidity (occurring alongside a physical condition)

Other specified insomnia

Several diagnoses in the DSM-5-TR include a category of “other specified” or “unspecified.”

This specifier is used when you’re experiencing almost all the symptoms of a condition, or a mixed bag of symptoms, that can’t clearly be grouped under an existing diagnosis.

If your symptoms are causing you distress but don’t meet the full criteria for an insomnia diagnosis, a healthcare or mental health professional may use this identifier moving forward.

There are other reasons you might receive an unspecified DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis.

Situational insomnia, aka acute insomnia, is recognized by the DSM-5-TR as insomnia symptoms that meet all the criteria except the minimum duration requirement.

This form of insomnia is often related to life events or sleep schedule changes.

Another reason for an unspecified diagnosis may be the presence of only nonrestorative sleep. This symptom was originally listed in the DSM-IV-TR as a primary symptom of insomnia disorder.

While it’s no longer included as part of the DSM-5-TR criteria, experiencing only nonrestorative sleep for an extended period of time may warrant a diagnosis of “other specified insomnia” if no other condition is identified as the cause.

Insomnia as a feature vs. a diagnosis

Insomnia can be both an independent diagnosis and a feature of other mental and physical conditions.

As a feature, insomnia represents challenges in sleeping but may not meet the full diagnostic criteria of a disorder.

When you’re living with insomnia disorder, your symptoms meet the sleep disturbance descriptions as well as the outlined time frames and levels of impairment cited in the DSM-5-TR.

If you’ve received a DSM-5-TR insomnia diagnosis, your primary symptoms will involve at least one of the following:

- difficulty falling asleep

- challenges maintaining sleep

- inability to fall back asleep after an early-morning wake up

These three symptoms define an insomnia diagnosis, regardless of type. How those symptoms manifest in your daily life is often unique.

You may experience:

- daytime sleepiness

- fatigue

- irritability

- mood fluctuations

- declining work or school performance

- difficulty concentrating

- lack of focus

- memory lapses

- erratic sleep schedules

- excessive napping

- spending more time in bed

- preoccupation with being unable to sleep

- decreased energy

- anxiety

- depression

- emotional reactivity

- muscle pain

- headache

- gastrointestinal upset

Several factors can influence how insomnia affects your thoughts and actions. If you’re living with insomnia disorder and major depressive disorder, for example, you may find symptoms of low mood are more prevalent for you.

If you’re living with insomnia disorder and major depressive disorder, for example, you may find symptoms of low mood are more prevalent for you.

Not everyone shows symptoms that directly reflect the severity of sleep disturbance.

You may experience insomnia for years, most nights of the week, but outwardly show minimal signs to those around you.

The DSM-5-TR lists several sleep disorders in addition to insomnia. This includes:

- hypersomnolence disorder

- narcolepsy

- obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea

- central sleep apnea

- sleep-related hypoventilation

- circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders

- non-rapid eye movement sleep arousal disorders

- nightmare disorder

- rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

- restless legs syndrome

- substance or medication-induced sleep disorder

- parasomnias

- other or unspecified sleep disorder

All these sleep disorders have their own criteria that set them apart from insomnia.

For many of them, specific sleep challenges are essential to the diagnosis and are the dominant feature even if insomnia is present.

For example, central sleep apnea involves breathing patterns that are critical to the diagnosis. Similarly, restless legs syndrome has symptoms specific to leg sensations and movement that aren’t part of the diagnostic criteria for insomnia.

Insomnia can be an independent condition or a feature of another primary condition. It’s characterized by challenges with falling asleep, staying asleep, and resuming sleep in the mornings.

When you live with insomnia, sleeplessness is often only one of the tell-tale signs. Irritability, trouble concentrating, and physical aches and pains can all be a part of the insomnia experience.

Insomnia is often treatable. It may improve as other co-occurring conditions improve, and it may lessen in severity with treatment and lifestyle changes.

To learn more about insomnia disorder, treatment, or where to find support, you can visit:

- American Sleep Association

- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research

- Better Sleep Council

- Find a sleep therapist through the Anxiety & Depression Association of America

If you’re wondering if you may have a sleep disorder, consider taking our sleep quiz.

Diagnosis and treatment of insomnia: new European guidelines

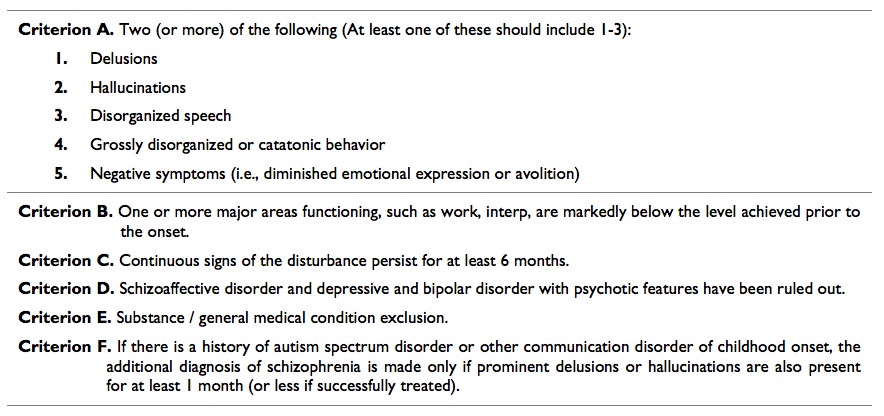

The September issue of J Sleep Res published clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia in adults prepared by the working group of the European Sleep Research Society ( ESRS ). Recommendations are based on a systematic review of meta-analyses published up to June 2016. Issues of etiology and pathophysiology (including 3P -model and hyperactivation model), diagnostic criteria (according to ICD-10, DSM-5 and ICSD-3 ) and procedure for diagnosing insomnia. A detailed assessment of the somatic and psychiatric/psychological history is mandatory, including diseases of the internal organs, the use of stimulants/alcohol and drugs, the presence of mental disorders, personality traits, and social factors that may cause sleep disturbances. Sleep assessment, in addition to the history of insomnia and its symptoms, includes information from a bed partner, an analysis of social and circadian factors (shift work, sleep phase shifts, etc. ) and sleep-related habits. It is recommended that you complete a standard sleep diary for 7-14 days, as well as an insomnia severity index ( Insomnia Severety Index ) and / or similar questionnaires (Bergen scale of Inssonia / Bergen InSomnia Scale ), Sleep indicator / SLEEP Condition ). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ( Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ) can be used to assess sleep but is not a specific method for diagnosing insomnia. Actigraphy is mandatory used for circadian rhythm disorders and irregular sleep and wakefulness, to a lesser extent - for the quantitative assessment of sleep parameters. Polysomnography is used not only when it is necessary to exclude other sleep disorders (sleep apnea, periodic lower limb movement syndrome and narcolepsy), but also for treatment-resistant insomnia, insomnia in occupational risk groups (for example, drivers) and when a significant discrepancy is suspected.

) and sleep-related habits. It is recommended that you complete a standard sleep diary for 7-14 days, as well as an insomnia severity index ( Insomnia Severety Index ) and / or similar questionnaires (Bergen scale of Inssonia / Bergen InSomnia Scale ), Sleep indicator / SLEEP Condition ). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ( Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ) can be used to assess sleep but is not a specific method for diagnosing insomnia. Actigraphy is mandatory used for circadian rhythm disorders and irregular sleep and wakefulness, to a lesser extent - for the quantitative assessment of sleep parameters. Polysomnography is used not only when it is necessary to exclude other sleep disorders (sleep apnea, periodic lower limb movement syndrome and narcolepsy), but also for treatment-resistant insomnia, insomnia in occupational risk groups (for example, drivers) and when a significant discrepancy is suspected. between subjective sensation and actual sleep duration. The hypothesis of a special biological significance of insomnia with a short sleep duration, confirmed by polysomnography, is mentioned.

between subjective sensation and actual sleep duration. The hypothesis of a special biological significance of insomnia with a short sleep duration, confirmed by polysomnography, is mentioned.

Clinical guidelines detail the epidemiology of chronic insomnia (prevalence ranges from 5.7% to 19% in studies conducted in various European countries), the health risks associated with insomnia, and the costs to health care systems. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTI) is recommended as first-line therapy for chronic insomnia in adults of all ages. Various variants of CBTI are considered (training in sleep hygiene, relaxation methods, cognitive therapy, behavioral strategies - sleep restriction, stimulus control), other psychotherapeutic approaches (method of nonjudgmental conscious observation and hypnotherapy). The table provides a list of studies confirming the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic methods in terms of evidence-based medicine.

Pharmacotherapy for insomnia is recommended when first-line therapy (CBTI) is not effective or available. In these cases, benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine receptor agonists, as well as some sedative antidepressants, can be used for short-term therapy - all of them are not recommended for long-term therapy. Antihistamines and antipsychotics are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia (due to the lack of proven efficacy, and antipsychotics also due to side effects). Melatonin and herbal medicine are also not recommended for the treatment of insomnia. Bright light therapy and physical exercise are being considered as additional methods that may be effective in patients with insomnia. Alternative medicine methods (acupuncture, acupressure, aromatherapy, foot reflexology, homeopathy, meditation, moxibustion and yoga) are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia.

In these cases, benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine receptor agonists, as well as some sedative antidepressants, can be used for short-term therapy - all of them are not recommended for long-term therapy. Antihistamines and antipsychotics are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia (due to the lack of proven efficacy, and antipsychotics also due to side effects). Melatonin and herbal medicine are also not recommended for the treatment of insomnia. Bright light therapy and physical exercise are being considered as additional methods that may be effective in patients with insomnia. Alternative medicine methods (acupuncture, acupressure, aromatherapy, foot reflexology, homeopathy, meditation, moxibustion and yoga) are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia.

Possible side effects of various treatments for insomnia (CBTI, pharmacotherapy) are discussed in detail, including those related to their use in the elderly, the impact on the management of transport and production activities, the risk of traumatic injuries, suicide, and the impact on cognitive functions. . Data from large cohort studies in France and the UK are presented, indicating that even episodic benzodiazepine use is associated with increased mortality.

. Data from large cohort studies in France and the UK are presented, indicating that even episodic benzodiazepine use is associated with increased mortality.

Promising trends in the treatment of insomnia are mentioned separately. It is noted that the problems with conducting an individual CBTI dictate the need to study lightweight approaches, such as conducting CBTI by paramedical staff, including in groups, as well as using the Internet. Acceptance and responsibility therapy ( Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, ACT ) and intensive sleep restoration ( intensive sleep retraining ) . Drugs available in the US but not in Europe (ramelteon and suvorexant), as well as tiagabine and pregabalin, are being considered. Additional evaluation of the effectiveness of bright light therapy, physical training, and new methods such as brain cooling ( brain cooling ) and transcranial electrical stimulation is required.

Full text of clinical guidelines in English — download in PDF

Insomnia in patients with schizophrenia

Material specially for Gedeon Richter: Portal for Physicians prepared by:

Evgeniy Dmitrievich Kasyanov, psychiatrist, researcher at the Department of Translational Psychiatry, N.N. V.M. Bekhtereva, creator of the popular science portal "Psychiatry & Neuroscience".

Translation: Dolina A.A.

Sleep is a physiological state characterized by a temporary cessation of sensory activity, mobility and alertness. Body functions and mental activity undergo changes. This is of great importance for mental and physical balance [1]. Insomnia is often seen as a symptom of mental disorders. However, evidence suggests that insomnia may be an independent phenomenon and may even precede psychiatric disorders [1].

Most patients with schizophrenia complain about sleep disorders [1]. The condition is almost always associated with daytime fatigue and mood swings, including irritability, dysphoria, tension, helplessness, and depressed mood. In addition, this condition is associated with a serious risk of relapse in depression and anxiety, and may also predict exacerbation of psychotic symptoms [1].

The condition is almost always associated with daytime fatigue and mood swings, including irritability, dysphoria, tension, helplessness, and depressed mood. In addition, this condition is associated with a serious risk of relapse in depression and anxiety, and may also predict exacerbation of psychotic symptoms [1].

Batalla-Martin et al. quantified the prevalence of insomnia in a sample of 267 outpatients with schizophrenia and studied its impact on quality of life. However, the diagnostic variability of insomnia makes it difficult to compare the results of different studies, for this reason the authors analyzed insomnia based on different diagnostic tools. The prevalence of insomnia in patients with schizophrenia was 23.2% according to the ICD-10 criteria, which is higher than in the general population [2].

The prevalence of insomnia according to DSM-IV criteria was 7.9%, similar to the prevalence seen in studies with general population samples. The prevalence of any of the clinical symptoms of insomnia was 63.7%. The frequency of symptoms is one of the criteria for diagnosing insomnia, and the difference between the two guidelines in this regard explains these differences. However, in another study by Seow et al. used the DSM-V found a similar prevalence of insomnia of 25%, which is explained by the greater similarity of the ICD-10 and DSM-V diagnostic criteria for the number of nights per week during which sleep problems are present.

The prevalence of any of the clinical symptoms of insomnia was 63.7%. The frequency of symptoms is one of the criteria for diagnosing insomnia, and the difference between the two guidelines in this regard explains these differences. However, in another study by Seow et al. used the DSM-V found a similar prevalence of insomnia of 25%, which is explained by the greater similarity of the ICD-10 and DSM-V diagnostic criteria for the number of nights per week during which sleep problems are present.

Research has also shown that older age, lower education, and a body mass index corresponding to obesity become statistically significant factors associated with insomnia. Logistic regression showed that the presence of insomnia increases the likelihood of problems with mobility, self-care, and also causes difficulties in daily activities. The presence in patients with schizophrenia of chronic pain or discomfort and symptoms of anxiety and depression is also associated with a higher likelihood of insomnia.

The consequences of insomnia go beyond the disorder itself and affect all areas of patients' lives. In this regard, in addition to quantitative measurements of insomnia, it is important to resort to a qualitative assessment, which could provide a more complete understanding of the pathology from the point of view of the patient's own perception and experience, in order to be able to tailor future interventions for the treatment of insomnia.

Batalla-Martin et al. Of the 267 participants in the 2020 study, 170 patients with schizophrenia were selected who met at least one of the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for insomnia. Physicians studied the clinical symptoms, the effects of insomnia, and patients' perceptions of the care they received. The final sample consisted of 31 patients with schizophrenia, they were divided into three clusters: severe-moderate insomnia; mild insomnia; absence of symptomatic insomnia [2].

Interviewed patients clearly identified various characteristics of insomnia, described their experiences, ideas about ideal sleep. Patients described insomnia as a condition that prevents them from sleeping and resting, giving rise to a feeling of constant anxiety. Virtually all participants reported that they would like to have a sense of physical and mental relaxation as they realize the importance of this in their daily lives. Participants cited poor sleep hygiene, rumination, and intrusive thoughts as key factors preventing them from falling asleep. Reflections were present in all three groups, regardless of the severity of their insomnia. They became the trigger that caused the participants the most anxiety and distress. Delusions present in schizophrenia, comorbid medical conditions, or problems with urinary incontinence also contributed to the onset of insomnia.

Patients described insomnia as a condition that prevents them from sleeping and resting, giving rise to a feeling of constant anxiety. Virtually all participants reported that they would like to have a sense of physical and mental relaxation as they realize the importance of this in their daily lives. Participants cited poor sleep hygiene, rumination, and intrusive thoughts as key factors preventing them from falling asleep. Reflections were present in all three groups, regardless of the severity of their insomnia. They became the trigger that caused the participants the most anxiety and distress. Delusions present in schizophrenia, comorbid medical conditions, or problems with urinary incontinence also contributed to the onset of insomnia.

Insomnia was associated with many consequences:

- feelings of depression, guilt, bad mood, anxiety, irritability, apathy, restlessness;

- lack of energy and motivation;

- difficulty concentrating and working;

- memory problems, impaired thinking;

- difficulty waking up,

- exacerbation of the course of schizophrenia.

These effects significantly limited the ability of patients to perform daily tasks, which affected their quality of life.

Behavioral strategies used by patients to fall asleep faster vary. Someone listened to music before going to bed, others drank herbal tea, others meditated. The researchers found that most of these actions were ineffective. Participants reported that being active during the day, resulting in extreme fatigue in the evening, allowed them to fall asleep more quickly.

However, patients in the severe/moderate insomnia group were unaware of the need for movement and activity, and reported a lack of motivation despite the severity of suffering.

Patients with severe/moderate and mild insomnia require pharmacological treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy. Pharmacological treatment is a common solution offered to patients, but has undesirable side effects such as morning sleepiness, drug addiction or tolerance. Some patients also have a negative view of additional drugs because they take a large number of drugs to treat the underlying disorder. Patients without insomnia, but with a history of one or more risk factors, require psychoeducation and preventive treatment, including advice on habits, sleep hygiene, and relaxation techniques.

Patients without insomnia, but with a history of one or more risk factors, require psychoeducation and preventive treatment, including advice on habits, sleep hygiene, and relaxation techniques.

Insomnia is a serious public health problem. Patients with schizophrenia who suffer from insomnia have a lower quality of life. Knowledge of the subjective experience of patients gives a more complete picture of the impact of insomnia on the course of schizophrenia and the condition of patients. Based on this experience, it is worth adjusting the therapy in order to prevent the transition of a sleep disorder into a chronic form and a worsening of the prognosis of the underlying disease. From interviews with patients, their readiness to be treated comprehensively, without abandoning any of the possible strategies, is obvious - patients are looking for serious, powerful and effective methods of treatment. The quality of life of people with schizophrenia and insomnia can be improved by offering strategies that combine the patient's own perspective and experience with the support and motivation of the physician.