Quetiapine used for dementia

Treating disruptive behavior in people with dementia

Antipsychotic medicines are usually not the best choice

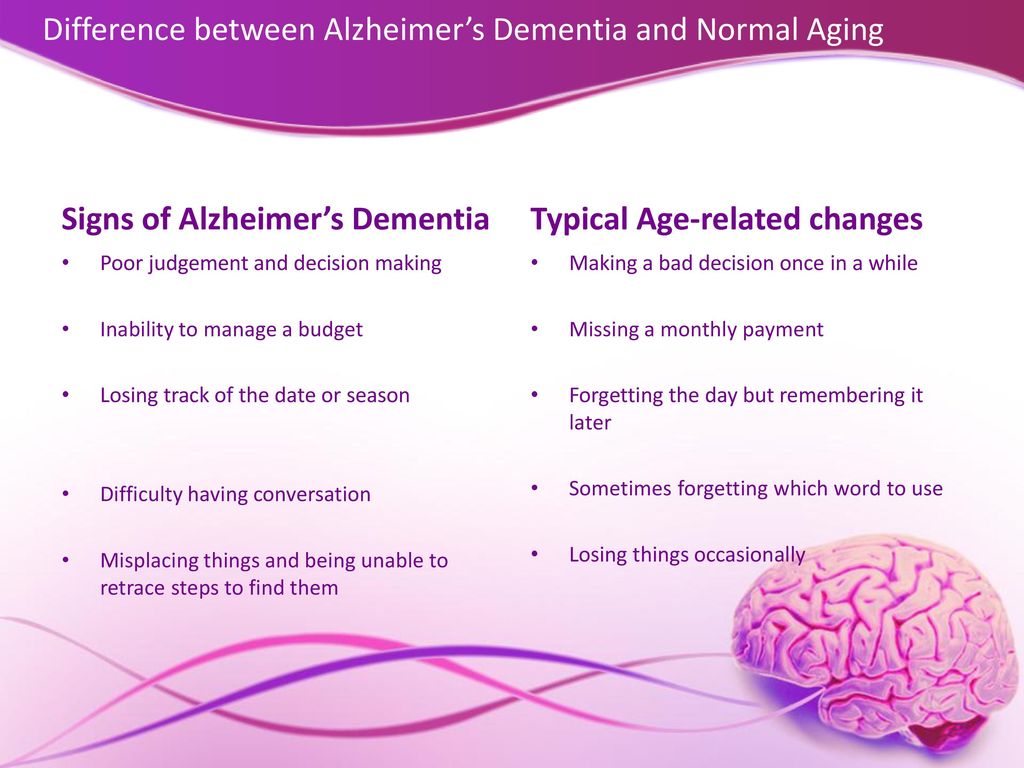

People with Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia can become restless, aggressive, or disruptive. They may believe things that are not true. They may see or hear things that are not there. These symptoms can cause even more distress than the loss of memory.

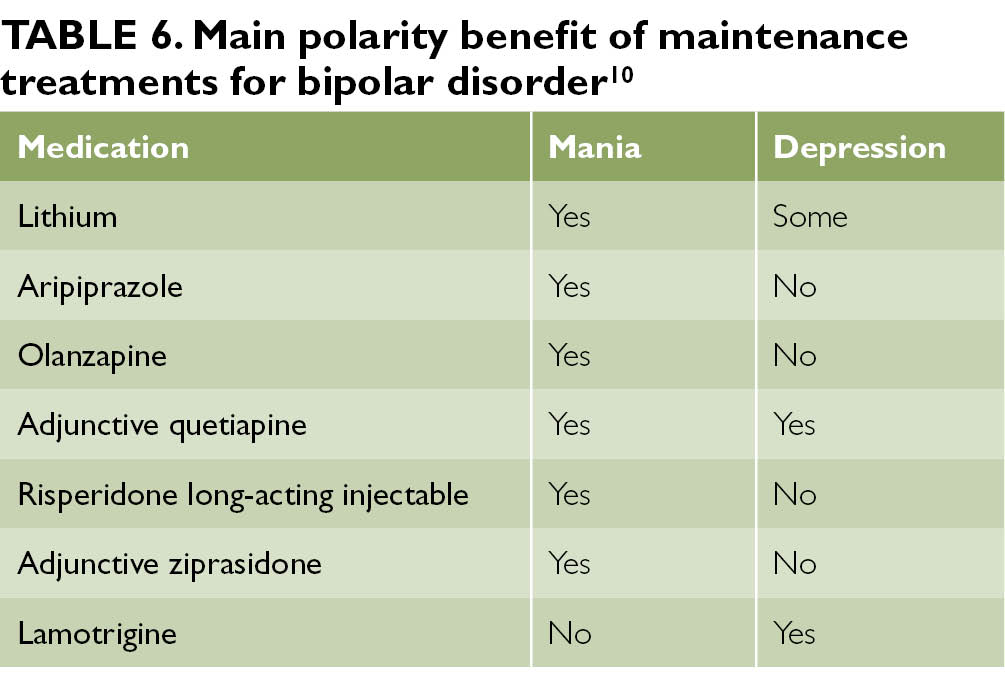

Doctors often prescribe powerful antipsychotic drugs to treat these behaviors:

- Aripiprazole (Abilify and generic)

- Olanzapine (Zyprexa and generic)

- Quetiapine (Seroquel and generic)

- Risperidone (Risperdal and generic).

In most cases, antipsychotics should not be the first choice for treatment, according to the American Geriatrics Society. Here’s why:

Antipsychotic drugs don’t help much.

Studies have compared these drugs to sugar pills or placebos (no treatment). These studies showed that anti-psychotics usually don’t reduce disruptive behavior in older dementia patients.

They can cause serious side effects.

Doctors can prescribe these drugs for dementia. But the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved this use. The side effects can be serious. The FDA now requires the strongest warning labels on the drugs. Side effects include:

- Drowsiness and confusion—which can reduce social contact and mental skills, as well as increase falls

- Weight gain

- Diabetes

- Shaking or tremors (which can be permanent)

- Pneumonia

- Stroke

- Sudden death

Other approaches often work better.

It is almost always best to try other approaches first, such as the suggestions listed below.

Make sure the patient has a thorough exam and medicine review.

- The cause of the behavior may be a common condition, such as constipation, infection, vision or hearing problems, sleep problems, or pain.

- Many medicines and combinations of medicines can cause confusion and agitation in older people.

Talk to a behavior specialist.

A specialist can help you find ways to handle the problem without medicines. For example, when someone is startled, they may become agitated. It may help to warn the person before you touch them.

Consider other medicines first.

Talk to your healthcare provider about the following medicines. They have been approved for treatment of disruptive behaviors.

- Medicines that slow mental decline in dementia.

- Antidepressants, for people with a history of depression or who are depressed and anxious.

Consider antipsychotic drugs if:

- Other steps have failed.

- The person is severely distressed.

- The person could hurt him- or herself, or others.

Start an antipsychotic medicine at the lowest possible dose. Caregivers and healthcare providers should watch the person carefully to make sure that symptoms improve and that there are no serious side effects. If the medicine is not helping or is no longer needed, it should be stopped, after discussion with a healthcare provider.

If the medicine is not helping or is no longer needed, it should be stopped, after discussion with a healthcare provider.

This report is for you to use when talking with your health-care provider. It is not a substitute for medical advice and treatment. Use of this report is at your own risk. © 2017 Consumer Reports. Developed in cooperation with the American Geriatric Society.

09/2013

Antipsychotics and other drug approaches in dementia care

Antipsychotic drugs

What are antipsychotic drugs?

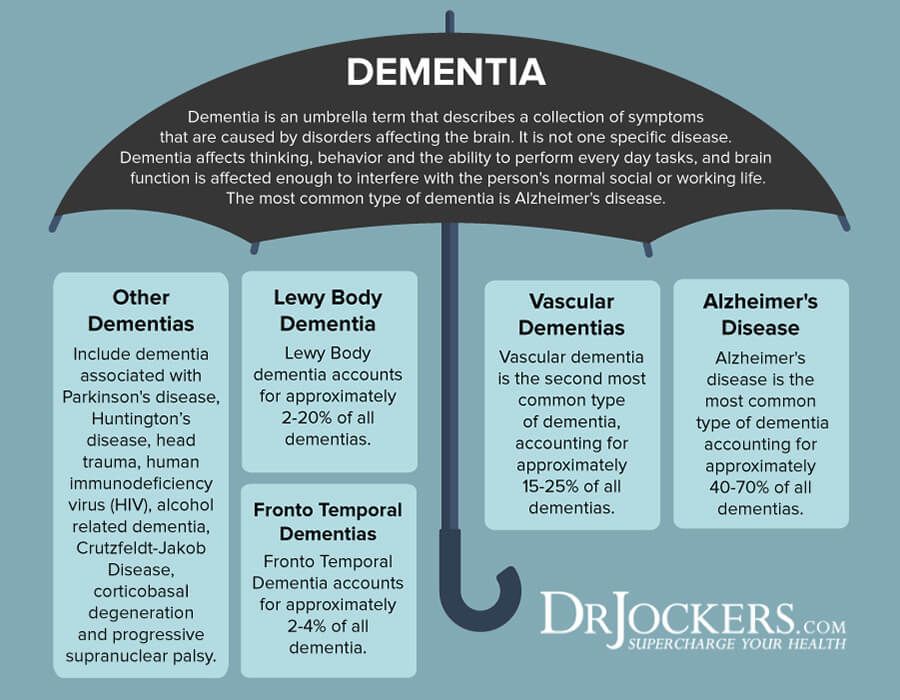

Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat people who are experiencing severe agitation, aggression or distress from psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions. They tend to be used only as a last resort, such as when the person, or those around them, are at immediate risk of harm.

For some people, antipsychotics can help to reduce the frequency or intensity of these changes. However, they also have serious risks and side effects, which the doctor must consider when deciding whether to prescribe them.

However, they also have serious risks and side effects, which the doctor must consider when deciding whether to prescribe them.

The first prescription of an antipsychotic should only be done by a specialist doctor. This is usually an old-age psychiatrist, geriatrician or GP with a special interest in dementia.

What antipsychotic drugs may be prescribed for a person with dementia?

There are several antipsychotic drugs that may be used. Each one has slightly different effects on the brain and has its own potential risks and side effects.

The drug with the most evidence to support its use in dementia is risperidone. It is licensed for short-term (up to six weeks) treatment of persistent aggression in people with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease when there is risk of harm to the person or others. However, this is only if non-drug approaches have already been tried without success.

An older antipsychotic called haloperidol is licensed for use in people with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. However, most doctors consider its risks and side effects in people with dementia to be too severe. It tends to be used only in emergencies as a last resort.

However, most doctors consider its risks and side effects in people with dementia to be too severe. It tends to be used only in emergencies as a last resort.

What are off-label antipsychotics drugs?

Other antipsychotic drugs prescribed for people with dementia are done so ‘off-label’. This means that the doctor can prescribe them if they have good reason to do so, and provided they follow guidance set out by the General Medical Council.

A doctor may choose to prescribe an off-label antipsychotic drug when it offers a better balance of benefits and risks for an individual patient. For example, risperidone may be effective in people with dementia, but it also increases the risk of having a stroke. So if a person has already had a stroke it might be safer to prescribe an off-label drug that doesn’t carry this risk, even though it might be less effective.

The off-label antipsychotics most often used for patients with dementia are:

- quetiapine and clozapine – These drugs are mostly used if a person has dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia.

This is because they interfere less with drugs that treat other symptoms of these conditions. However, there is very little evidence that they are effective. They may also cause the person to become drowsy or dizzy, which can increase the risk of falling

This is because they interfere less with drugs that treat other symptoms of these conditions. However, there is very little evidence that they are effective. They may also cause the person to become drowsy or dizzy, which can increase the risk of falling - olanzapine – This is not as effective as risperidone, but may be prescribed if the doctor needs to sedate the person to stop them becoming agitated. However, it can make confusion worse, affect the person’s metabolism and increase the risk of them having a stroke

- aripiprazole – This is one of the newest antipsychotic drugs. Although it works well for people with schizophrenia, there is much less evidence that it reduces hallucinations and delusions in people with dementia, so it is not often used.

How are antipsychotic drugs reviewed?

Antipsychotic drug treatments should be reviewed after six or 12 weeks, or both.

When the prescription of an antipsychotic is reviewed, the doctor may suggest stopping the drug in one go (for people taking a low dose of antipsychotic) or a more gradual reduction (for people on a higher dose) known as ‘tapering’. In either case, the effects on the person’s behavioural and psychological changes should be closely monitored. If they seem to be getting worse, it may be necessary to restart or increase the dose again.

In either case, the effects on the person’s behavioural and psychological changes should be closely monitored. If they seem to be getting worse, it may be necessary to restart or increase the dose again.

If the person had a pre-existing mental health condition before they developed dementia and this was managed with antipsychotic drugs, they should continue to take them as prescribed by their psychiatrist.

Who can antipsychotic drugs help?

Some antipsychotics can have a small but significant beneficial effect on agitation, aggression and, to a lesser extent, psychosis in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Improvements are normally only seen once these drugs have been taken for several weeks.

Antipsychotic drugs may be prescribed for people with Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia or mixed dementia (which is usually a combination of these two).

If a person with dementia with Lewy bodies or Parkinson’s disease dementia is prescribed an antipsychotic drug, it should be done with the utmost care, under constant supervision and with regular review. This is because people with these types of dementia, who often have visual hallucinations, are at particular risk of severe negative reactions to most antipsychotics.

This is because people with these types of dementia, who often have visual hallucinations, are at particular risk of severe negative reactions to most antipsychotics.

The doctor is likely to choose a drug with the least side effects, but they will only be able to use very small doses. This is unlikely to have much effect on agitation and psychosis.

Issues with the use of antipsychotic drugs

Antipsychotic drugs can cause serious side effects, and the risk increases with continued use over weeks and months.

Possible negative effects of antipsychotics include:

- drowsiness or confusion

- shaking, unsteadiness and reduced mobility

- worse than usual dementia symptoms, such as problems with thinking and memory

- higher risk of swelling around the lower limbs

- higher risk of infections (particularly of the chest and urinary tract)

- higher risk of falls and fractures

- higher risk of blood clots

- higher risk of having a stroke

- higher risk of dying earlier than if they hadn’t taken the drugs.

The decision to use antipsychotics should be taken very seriously. Benefits may sometimes come at the expense of the person’s health and quality of life.

When considering prescribing an antipsychotic, the doctor will check if the person has high blood pressure, an irregular heartbeat, diabetes or a history of strokes. This is because these conditions carry additional risks for a person taking antipsychotic drugs.

There is evidence that some people with dementia who may not need antipsychotics are still being prescribed them. For example, they are being prescribed to treat distress or aggression before non-drug approaches have been tried thoroughly. Also, some people are kept on an antipsychotic for too long without a review at 12 weeks or a clear plan for when they should come off the drug.

There is an ongoing national drive to reduce inappropriate prescribing of antipsychotic drugs in dementia, especially for people in the later stages of dementia living in residential care. Alzheimer’s Society would like to see these drugs used only when they are really needed.

Alzheimer’s Society would like to see these drugs used only when they are really needed.

Questions to ask the doctor about antipsychotic drugs

If the person with dementia can consent to taking an antipsychotic drug, they need to be properly informed about the drug.

If a doctor is making the decision, the person with dementia and their carer should still be involved as much as possible and should be shown their care plan.

The following questions may help with discussions:

- Why is the person being prescribed an antipsychotic? Which specific behaviours or psychological changes is the drug meant to be helping with?

- Have possible medical causes of the changes (such as infection, pain or constipation) been investigated and ruled out?

- Are there any non-drug approaches that haven’t been tried which might help?

- What can I do as a carer to support the person?

- Is there anything else you need to know about the person (such as their personality, life history or other health problems) to work out what may be causing the changes?

- How will we know if the drug is working?

- What are the risks associated with taking this drug?

- What side effects might the drug cause and how can they be managed effectively?

- What is the plan for the person to come off the antipsychotic?

- When will the continued use of this drug be reviewed?

Useful organisations

General Medical Council (GMC)

Telephone

0161 923 6602 (9am–5pm Monday–Friday)

Email

[email protected]

Website

www. gmc-uk.org

gmc-uk.org

The GMC helps protect patients and improve UK medical education and practice by supporting students, doctors, educators and healthcare providers. It provides guidance on the prescribing of medication, including off-label drugs.

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)

Telephone

020 3080 6000

Email

[email protected]

Website

products.mhra.gov.uk

The MHRA products website provides detailed information on specific drugs, and the ‘Yellow Card’ scheme for reporting side effects.

Review details

Last reviewed: July 2021

Next review due: July 2024

Reviewed by: Dr Sharmi Bhattacharyya, Consultant & Clinical Lead, Older People’s Mental Health, North Wales Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board and Dr Manoj Rajagopal, Consultant Old Age Psychiatrist and Associate Medical Director, Lancashire & South Cumbria NHS Foundation Trust

This information has also been reviewed by people affected by dementia.

Seroquel in the treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of Alzheimer's disease - Psychiatry and Psychopharmacotherapy. P.B. Gannushkina Annex No. 2

Subscribe to new numbers

Author: IV Kolykhalov, Ya.

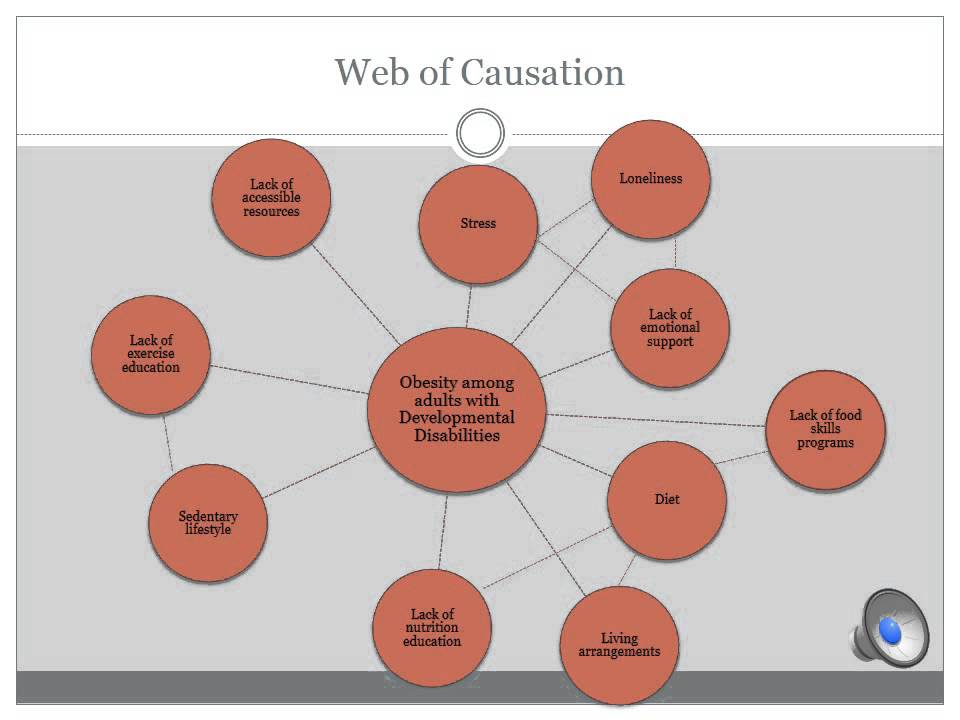

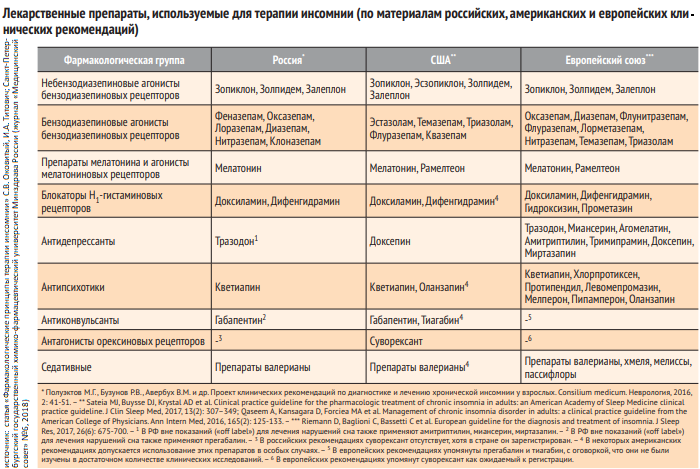

The need for drug treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of dementia is determined by their severity, the presence of anxiety or aggression, as well as the security threat associated with these violations for the patient or his immediate environment. Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents. Until now, various groups of psychotropic drugs have been used to treat psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants. nine0003

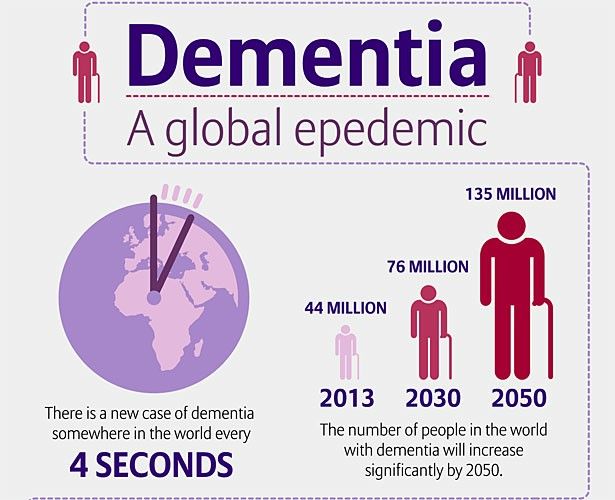

Behavioral and psychopathological disorders that accompany the development of dementia at different stages of its formation occur in more than 80% of patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) (R. Sweet B.Pollock, 1998). Approximately half of the patients observed in the outpatient departments of specialized clinics, and three-quarters of patients in nursing homes, have various psychotic and behavioral disorders (P.Tariot, L.Blazina, 1994; S.Finkel, 1998).

Sweet B.Pollock, 1998). Approximately half of the patients observed in the outpatient departments of specialized clinics, and three-quarters of patients in nursing homes, have various psychotic and behavioral disorders (P.Tariot, L.Blazina, 1994; S.Finkel, 1998).

Depending on the nature of behavioral and psychopathological disorders in dementia, the following groups of disorders are distinguished: psychotic (delusional, hallucinatory and hallucinatory-delusional) and depressive (depressed mood, apathy, lack of motivation) symptoms, as well as behavioral disorders proper (aggression, wandering, motor restlessness). , violent screaming, inappropriate sexual behavior, etc.). nine0012 The need for drug treatment of psychotic and behavioral symptoms of dementia is determined by their severity, the presence of anxiety or aggression, as well as the security threat associated with these violations for the patient or his immediate environment. Most cases of aggression, psychomotor agitation, as well as the actual psychotic symptoms of dementia, require the appointment of psychopharmacological agents.

Until now, various groups of psychotropic drugs have been used to treat psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with dementia: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants. nine0012 Undesirable effects are inherent in all of the listed groups of drugs. Thus, the use of antidepressants (especially tricyclics) in elderly patients with dementia is associated with the risk of hypotension and serious anticholinergic effects. Anxiolytics (especially benzodiazepines) can cause excessive sedation and cognitive depression, or, conversely, increase aggression and anxiety. But the greatest risk of adverse effects on elderly patients with dementia is associated with the use of antipsychotics. According to W.Petrie et al. (nineteen82), the use of antipsychotics was accompanied by adverse events in 90% of these patients. R. Barnes et al. (1982), who studied the effectiveness of treatment with loxapine and thioridazine (sonapax) in comparison with placebo for behavioral disorders in 56 patients with asthma and dementia of a different etiology, noted side effects in 45% of patients treated with loxapine and in 33% of those receiving thioridazine.

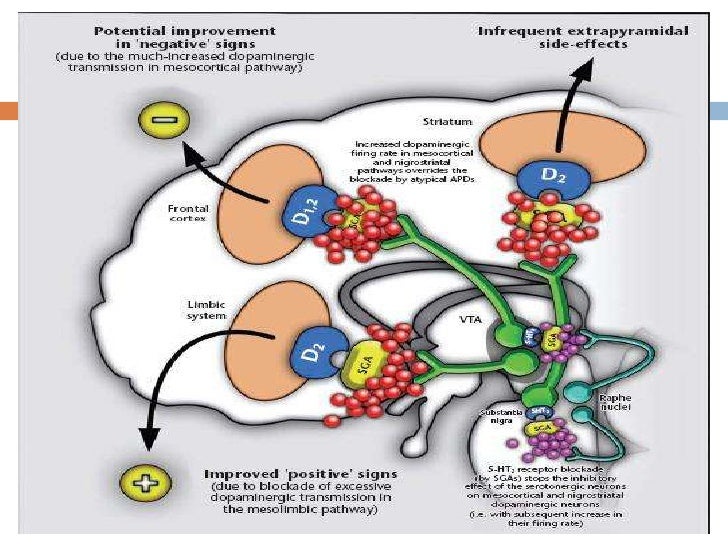

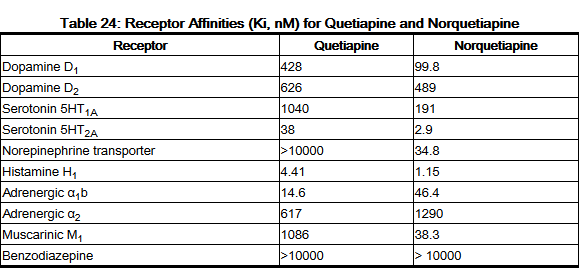

The search for psychotropic drugs with minimal anticholinergic effects seems to be a particularly urgent task in relation to the treatment of behavioral and psychotic disorders in patients with AD. nine0012 The emergence of a new generation of atypical antipsychotics is making a significant contribution to the improvement of modern antipsychotic therapy for dementia. Atypical neuroleptics have a significant advantage over traditional antipsychotics because they affect a wider range of psychopathological disorders, including affective disorders, agitation, hostility, and the actual psychotic symptoms that develop in various forms of dementia. It is especially important that in therapeutic doses they practically do not cause extrapyramidal and neuroendocrine side effects. nine0012 Seroquel (quetiapine) is the latest atypical antipsychotic drug introduced into practice. Seroquel is a dibenzothiazepine derivative with a wide range of affinity for various central nervous system receptor subtypes. Seroquel has the highest affinity for 5-HT 2 - serotonergic receptors with relatively low interaction with dopamine D 1 - and D 2 - receptors (J.Goldstein, 1996). Along with this, compared with classical antipsychotics, seroquel exhibits low tropism for muscarinic and a 1 -adrenergic receptors (C.Sailer, A.Salama, 1993). Seroquel shows selectivity for mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine receptors, which are considered responsible for the development of the actual antipsychotic effect. Unlike most classic and some atypical neuroleptics, seroquel has minimal effect on the nigrostrial dopamine system, which is associated with the development of neurological extrapyramidal side symptoms. All of these properties make Seroquel an effective antipsychotic with a favorable side effect profile. nine0012 The possibility of using Seroquel in geriatric psychiatry was studied in a large multicenter open study. Seroquel was used in elderly patients (n=151) with various psychotic disorders.

Seroquel has the highest affinity for 5-HT 2 - serotonergic receptors with relatively low interaction with dopamine D 1 - and D 2 - receptors (J.Goldstein, 1996). Along with this, compared with classical antipsychotics, seroquel exhibits low tropism for muscarinic and a 1 -adrenergic receptors (C.Sailer, A.Salama, 1993). Seroquel shows selectivity for mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine receptors, which are considered responsible for the development of the actual antipsychotic effect. Unlike most classic and some atypical neuroleptics, seroquel has minimal effect on the nigrostrial dopamine system, which is associated with the development of neurological extrapyramidal side symptoms. All of these properties make Seroquel an effective antipsychotic with a favorable side effect profile. nine0012 The possibility of using Seroquel in geriatric psychiatry was studied in a large multicenter open study. Seroquel was used in elderly patients (n=151) with various psychotic disorders. The study lasted 12 weeks. The average daily dose of the drug was 100 mg/day. According to D.McManus et al. (1999), the most common side effects during the study period were drowsiness (in 32% of patients), dizziness (in 14%), orthostatic hypotension (in 13%) and agitation (in 11%). A significant improvement in the condition of patients on the BPRS and CGI scales by the end of the study was established. Separately, the results of a study in a subgroup of patients (n=40) with Parkinson's disease were analyzed (J. Juncos et al., 1998). The results of this analysis showed that seroquel significantly reduced the severity of psychotic symptoms and did not cause worsening of the motor symptoms of parkinsonism. Moreover, during the period of treatment with seroquel, the severity of the latter gradually decreased. An analysis of the effectiveness of Seroquel in patients with Alzheimer's disease who exhibit symptoms of hostility (n=78) (L. Schneider et al., 1999) showed that the drug significantly significantly reduced hostile behavior.

The study lasted 12 weeks. The average daily dose of the drug was 100 mg/day. According to D.McManus et al. (1999), the most common side effects during the study period were drowsiness (in 32% of patients), dizziness (in 14%), orthostatic hypotension (in 13%) and agitation (in 11%). A significant improvement in the condition of patients on the BPRS and CGI scales by the end of the study was established. Separately, the results of a study in a subgroup of patients (n=40) with Parkinson's disease were analyzed (J. Juncos et al., 1998). The results of this analysis showed that seroquel significantly reduced the severity of psychotic symptoms and did not cause worsening of the motor symptoms of parkinsonism. Moreover, during the period of treatment with seroquel, the severity of the latter gradually decreased. An analysis of the effectiveness of Seroquel in patients with Alzheimer's disease who exhibit symptoms of hostility (n=78) (L. Schneider et al., 1999) showed that the drug significantly significantly reduced hostile behavior.

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of seroquel in the treatment of psychotic and behavioral disorders in patients with asthma. The study was conducted at the Scientific and Methodological Center for the Study of Alzheimer's Disease and Associated Disorders of the National Center for Health Care of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences. nine0012 The clinical study was performed as a simple open study on a non-selective group of patients (n=31, 5 men and 26 women) aged 49 to 84 years with various clinical forms of asthma. The mean age of the patients was 68.5±8.2 years. The duration of the disease ranged from 2 to 20 years and averaged 5.5±3.8 years. Five patients were treated in stationary conditions, 26 - on an outpatient basis.

The distribution of patients by clinical forms of asthma in accordance with the ICD-10 diagnostic headings is presented in tab. 1.

The condition of 7 patients corresponded to the stage of mild dementia, 16 - moderate and 8 patients - severe dementia (according to the criteria of the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale).

The clinical study was carried out according to a specially developed protocol using unified individual patient records. Patients' condition was assessed before the start of treatment and during the course of therapy (on days 28 and 56) using the Global Clinical Impression (CGI) scale, MMSE, ADAS-cog. -AD). nine0003

The majority of patients (38.7%) were included in the study due to the lack of effect from previous treatment with antipsychotic drugs. In 25.8%, the reason for switching to Seroquel was the presence of side effects from previous therapy, and 35.5% were prescribed antipsychotic therapy for the first time.

The drug was prescribed at a dose of 50 mg/day (25 mg 2 times a day). Over the next 7 days, the dose was increased to 100 mg / day (50 mg 2 times a day). A further increase in the dose of Seroquel was carried out individually by no more than 50 mg/day (maximum dose 300 mg/day). The duration of course therapy was 8 weeks. nine0012 Prior to the start of therapy, the majority (67. 7%) of patients had psychotic and behavioral symptoms so severe that they presented significant difficulties for their caregivers and/or were dangerous for the patient himself. In 10 patients (32.3%), behavioral disorders and psychotic disorders created some difficulties for those caring for them and/or could be dangerous for the patient himself, therefore, they were rated as moderate.

7%) of patients had psychotic and behavioral symptoms so severe that they presented significant difficulties for their caregivers and/or were dangerous for the patient himself. In 10 patients (32.3%), behavioral disorders and psychotic disorders created some difficulties for those caring for them and/or could be dangerous for the patient himself, therefore, they were rated as moderate.

By the end of therapy, the severity of psychotic and behavioral disorders was assessed as follows: moderately severe disorders - in 9(29.0%) patients, slightly pronounced - in 17 (54.8%) patients. In 5 patients (16.2%), the mentioned symptoms were completely reduced.

Evaluation of the effectiveness of therapy on the CGI scale ( Fig. 1 ) showed that in the examined patients, a significant and very significant positive effect of seroquel therapy was observed in 51.5% of cases already by the 28th day of therapy, and by the time the course was completed - in 64 .5% of patients. Only 1 patient showed no positive dynamics during treatment with seroquel. nine0003

nine0003

During therapy with Seroquel, a significant improvement in psychotic and behavioral symptoms on the BEHAVE-AD scale was found, starting from the 28th day of therapy ( fig. 2 , tab. 2 ).

At the end of therapy, a decrease in the severity of behavioral and psychotic symptoms by 73.5% was noted.

Analysis of the severity of individual groups of symptoms presented in the BEHAVE-AD scale showed that by the end of therapy, significant positive dynamics was noted across the entire spectrum of psychotic and behavioral symptoms. According to the sub-items of the scale "hallucinatory disorders", "impaired activity", "aggressiveness", the reduction of symptoms was more than 70% ( fig. 3 ).

It should be emphasized that in the course of treatment with seroquel, patients did not show any negative dynamics of cognitive indicators. On the contrary, by the end of therapy, there was a significant improvement in cognitive functions both on the MMSE scale and on the ADAS-cog scale. ( fig. 4 ).

( fig. 4 ).

Adverse events were observed in 5 (16.1%) of 31 patients treated, but no severe side effects were noted in any case. nine0012 4 patients (12.9%) had complaints of muscle weakness, which stopped after a dose reduction. In 2 patients, increased daytime sleepiness was noted. One patient was diagnosed with orthostatic hypotension.

The study showed that seroquel is an effective and safe agent in the treatment of behavioral and psychotic disorders in AD. During therapy with Seroquel, no significant adverse events were noted. Of particular note is the absence of extrapyramidal side symptoms, which are not uncommon in neuroleptic therapy of patients with dementia. In the process of treatment with Seroquel in patients with asthma, both psychotic and behavioral pathology are equally successfully reduced. The severity of psychopathological symptoms significantly decreased with the use of relatively small (50–300 mg/day) doses of Seroquel (average 100 mg/day). The highest doses of Seroquel had to be used to relieve delusional and hallucinatory disorders (100–300 mg/day) and relatively smaller doses to reduce the symptoms of aggression (50–200 mg/day) and treat depressive and anxiety-phobic disorders (50–200 mg/day). ). nine0012 Seroquel therapy in patients with AD not only does not increase cognitive impairment, as occurs with the use of typical antipsychotics, but as psychotic and behavioral symptoms decrease, even a significant improvement in the cognitive functioning of patients is observed.

The highest doses of Seroquel had to be used to relieve delusional and hallucinatory disorders (100–300 mg/day) and relatively smaller doses to reduce the symptoms of aggression (50–200 mg/day) and treat depressive and anxiety-phobic disorders (50–200 mg/day). ). nine0012 Seroquel therapy in patients with AD not only does not increase cognitive impairment, as occurs with the use of typical antipsychotics, but as psychotic and behavioral symptoms decrease, even a significant improvement in the cognitive functioning of patients is observed.

Thus, seroquel can be recommended to patients with AD as an effective and safe drug for the treatment of psychotic and non-psychotic psychopathological disorders, as well as behavioral disorders associated with dementia. nine0012

List of used literature Hide list

1. Burns A, Jacoby R, Levy R. Br J Psychiat 1990; 157:72–94.

2. Finkel S.I. Clinician 1998; 16:33–42.

3. Goldstein J.Safety and tolerability of switching from conventional antipsychotic therapy to quetiapine fumarate followed by abrupt withdrawal from quetiapine fumarate (poster). Presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit Program, Boca Raton, FL, June 10–13, 1998.

4 Juncos J, Yeung P, Sweitzer D et al. Quetiapine improves psychotic symptoms associated with Parkinson's disease (poster). Presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology; Las Croabas, P. R.; December 14–18, 1998.

5. McManus DQ, Arvanitis LA, Kowalcyk BB et al. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:292–8.

6. Petrie WM, Ban TA, Berney S et al. J Clin Psychophamacol 1982; 2:122–6.

7 Sailer CF, Salama AL. Psychopharmacology 1993; 112:285–92.

8. Schneider L, Yeung P, Sweitzer D, Arvanitis LA. "SEROQUEL" (quetiapine fumarate) reduces aggression and hostility in patients with psychoses related to Alzheimer's disease (poster). Presented at the 152th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, May 15–20th, 1999.

9. Sweet RA, Pollock BG. Drugs & Aging 1998; 12(2): 115–27.

10. Tariot PN, Blazina L. The psychopathology of dementia. In: Morris JC, editor. Handbook of dementing illnesses. N.Y.: Marcel Dekker lnc, 1994; 461–75.

November 15, 2003

Views: 9552

✚ Treatment of psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychiatric clinic of Professor Minutko. Article #7058

Alzheimer's disease (AD) affects 5-15% of the population over 65 and about 20% of people over 80. Alzheimer's disease is characterized by the gradual onset of multiple cognitive impairments and is associated with ongoing cognitive decline. There is a high prevalence of psychotic symptoms and behavioral disturbances in Alzheimer's disease. A review of studies assessing the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease-related psychosis found a median prevalence of 41.1% (range 12.2% to 74.1%), however, patients seen in outpatient clinics showed lower indicators. nine0003

Alzheimer's disease (AD) psychosis is characterized by delusions or hallucinations and may be associated with psychomotor agitation, negative symptoms, or depression. However, atypical antipsychotics were widely used and recommended by geriatric experts in the treatment of psychosis in Alzheimer's disease, with modest efficacy and relative safety, until US FDA warnings were issued in 2005 and meta-analyses showed no significant difference from placebo. . However, even today there are no specific psychotropic drugs that are approved for the treatment of psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Studies have shown that risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine can reduce psychotic symptoms and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia. Taking olanzapine for psychoses that developed with Alzheimer's disease (average dose 5.5 mg / day), quetiapine (average dose 56.5). mg/day), risperidone (median dose 1.0 mg/day) have been shown to be effective, but metabolic side effects have markedly dampened psychiatric enthusiasm for using these drugs to treat psychosis. However, clozapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole are recommended in most cases. nine0003

However, atypical antipsychotics were widely used and recommended by geriatric experts in the treatment of psychosis in Alzheimer's disease, with modest efficacy and relative safety, until US FDA warnings were issued in 2005 and meta-analyses showed no significant difference from placebo. . However, even today there are no specific psychotropic drugs that are approved for the treatment of psychosis in Alzheimer's disease. Studies have shown that risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine can reduce psychotic symptoms and behavioral disturbances in patients with dementia. Taking olanzapine for psychoses that developed with Alzheimer's disease (average dose 5.5 mg / day), quetiapine (average dose 56.5). mg/day), risperidone (median dose 1.0 mg/day) have been shown to be effective, but metabolic side effects have markedly dampened psychiatric enthusiasm for using these drugs to treat psychosis. However, clozapine, quetiapine, and aripiprazole are recommended in most cases. nine0003

The safety and tolerability profile of aripiprazole suggests a low potential for adverse effects on dementia and overall patient health. Let me remind the reader of my Blog that aripiprazole is a partial D 2 receptor agonist, a 5-HT 2A receptor antagonist, and a partial 5-HT 1A receptor agonist. In addition, aripiprazole has been shown to exhibit moderate affinity for alpha 1, alpha 2 and histamine H 1 receptors and negligible affinity for muscarinic M 1 receptors. Aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or conditions that may predispose patients to hypotension. Efficacy results indicate that aripiprazole 10 mg/day is an effective dose for patients with Alzheimer's disease psychosis, although some patients have achieved significant benefit with aripiprazole even at 5 mg/day. nine0003

Let me remind the reader of my Blog that aripiprazole is a partial D 2 receptor agonist, a 5-HT 2A receptor antagonist, and a partial 5-HT 1A receptor agonist. In addition, aripiprazole has been shown to exhibit moderate affinity for alpha 1, alpha 2 and histamine H 1 receptors and negligible affinity for muscarinic M 1 receptors. Aripiprazole should be used with caution in patients with known cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, or conditions that may predispose patients to hypotension. Efficacy results indicate that aripiprazole 10 mg/day is an effective dose for patients with Alzheimer's disease psychosis, although some patients have achieved significant benefit with aripiprazole even at 5 mg/day. nine0003

At the same time, physician warnings about cardiac, metabolic, cerebrovascular, and death risks have raised serious psychiatric concerns about the use of atypical antipsychotics in elderly patients with dementia. Movement disorders, sedation, and orthostasis are associated with an increased risk of falls and subsequent fractures.