Crazy definition psychology

The Definition of Insanity | Psychology Today

I hear this every week, sometimes twice a day: "The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results." No, it isn't.

To be clear, insanity is a legal term pertaining to a defendant's ability to determine right from wrong when a crime is committed. Here's the first sentence of law.com's lengthy definition:

Insanity. n. mental illness of such a severe nature that a person cannot distinguish fantasy from reality, cannot conduct her/his affairs due to psychosis or is subject to uncontrollable impulsive behavior.

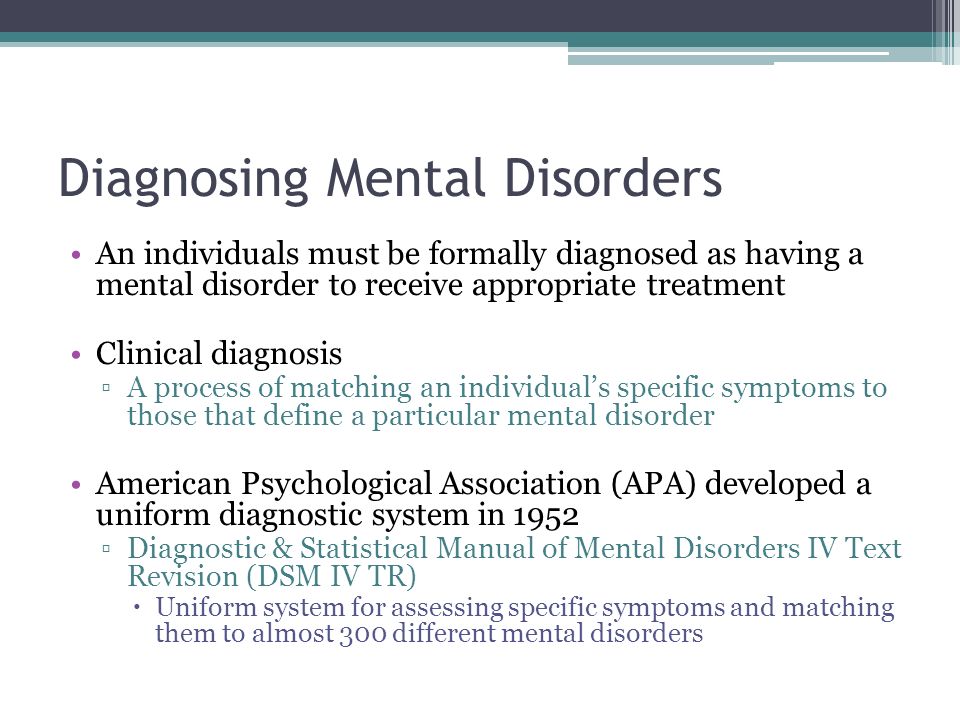

Insanity is a concept discussed in court to help distinguish guilt from innocence. It's informed by mental health professionals, but the term today is primarily legal, not psychological. There's no "insane" diagnosis listed in the DSM. There's no "nervous breakdown" either, but that's another post.

Origins of the term "insanity"

Where did this saying come from? It's attributed to Albert Einstein (probably not), Benjamin Franklin (probably not), Mark Twain (probably not) and mystery writer Rita Mae Brown (probably so) who used it in her novel Sudden Death. It's not clear who said it first, but according to at least one blogger it's "the dumbest thing a smart person ever said." The catchy saying has gathered steam in the past few years (example I, II, III), and regardless of the source, it's gotten a lot of mileage.

The dark underbelly of insanity

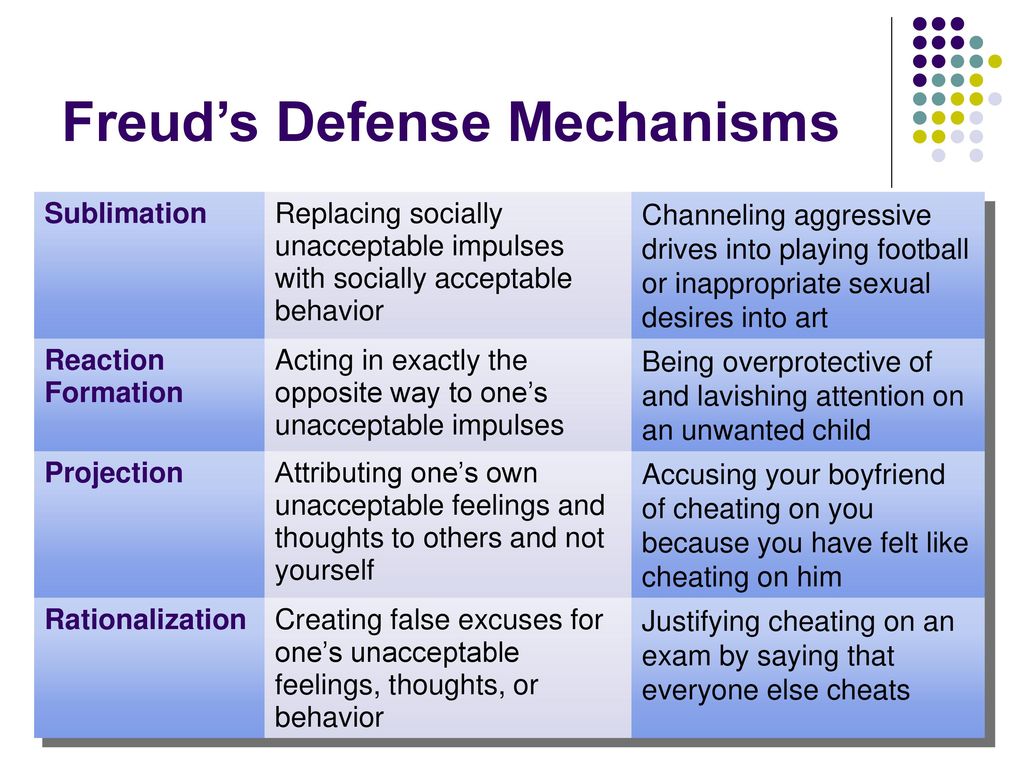

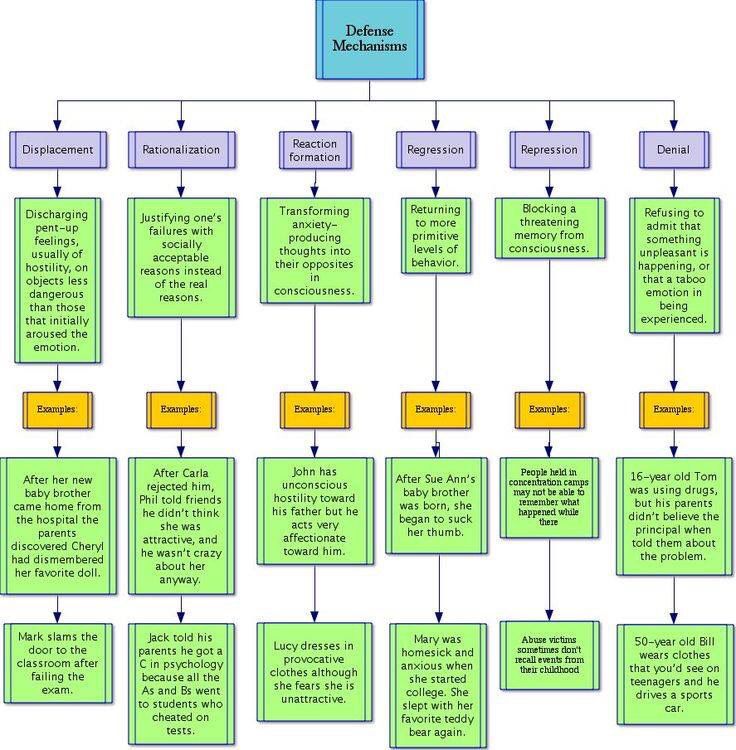

I'm not in the habit of slamming cute sayings (with one exception), but I think there's a dark underbelly to this one. I've started hearing people use it in the service of avoidance, which is a defense mechanism. Rather than facing their fears, they grab on to this saying for protection against possible failure, pain, or rejection. Some examples:

- "I've asked out two women and been shot down both times, and you know the definition of insanity..."

- "I jogged for a week and actually gained weight. They say the definition of insanity is ..."

- "It's been a month and I'm still crying about his death. I'm living the definition of insanity."

The definition of insanity doesn't have anything to do with jogging. It's important to keep grieving, jogging and asking people for dates because these are areas of life that require some repetition and are quite sane. As a therapist, when I hear these statements I can collude with the protective bubble of the socially accepted catchphrase or challenge it. When met with the examples above, I'll challenge.

It's important to keep grieving, jogging and asking people for dates because these are areas of life that require some repetition and are quite sane. As a therapist, when I hear these statements I can collude with the protective bubble of the socially accepted catchphrase or challenge it. When met with the examples above, I'll challenge.

Why we confuse the definition of "insanity"

I think the confusion behind this statement is best illustrated by these two words:

Perseveration: the pathological, persistent repetition of a word, gesture, or act.

Perseverance: steady persistence in a course of action in spite of difficulties, obstacles, or discouragement.

Some forms of dementia, traumatic brain injury, anxiety, and OCD can cause people to perseverate. They repeat words and tasks or try repeatedly to solve problems, but are left frustrated and unsatisfied. They're not necessarily insane but stuck in a non-productive pattern due to a glitch in brain function. Some medications or CBT tools may prove helpful.

Some medications or CBT tools may prove helpful.

There's also the psychodynamic construct called repetition compulsion where people unconsciously repeat past conflicts in an attempt at mastery. We want to finish unfinished business, so sometimes we recreate old, unresolved problems for the potential of a better outcome. A typical example would be a guy who desired closeness with his emotionally unavailable mother as a child and therefore seeks out unavailable women in his adulthood. Or a woman who feels it's always her duty to invite her selection of apathetic friends to socialize. Or someone who is drawn to crowds of wealthier/smarter/prettier/etc. people where they always feel left out. They're all trying to finally conquer some old feelings of rejection. But even if they do succeed today, it doesn't erase the pain from the past.

Let's not confuse perseveration with perseverance. A persistent quest against a fear or toward a goal is often the best course of action. Repeating the same constructive behavior over and over, hoping (one day) for a positive result is difficult but virtuous. It's the effort made by eating oatmeal every morning, brushing your teeth after every meal and daily journaling. It's weekly therapy, consistent workouts, and taking time for spirituality. It's Rudy trying over and over to get into Notre Dame. Or Mother Theresa tirelessly serving the poor. Or someone working to systematically overcome shyness, build healthier habits, or communicate better with their spouse. It's a 12-stepper taking it "one day at a time." The qualities of perseverance—consistency, loyalty—are beneficial to health and definitely not insane. And they're doing the same thing every day, hoping for some measure of progress.

It's the effort made by eating oatmeal every morning, brushing your teeth after every meal and daily journaling. It's weekly therapy, consistent workouts, and taking time for spirituality. It's Rudy trying over and over to get into Notre Dame. Or Mother Theresa tirelessly serving the poor. Or someone working to systematically overcome shyness, build healthier habits, or communicate better with their spouse. It's a 12-stepper taking it "one day at a time." The qualities of perseverance—consistency, loyalty—are beneficial to health and definitely not insane. And they're doing the same thing every day, hoping for some measure of progress.

So how do you tell the difference? Perseveration feels compulsive, hopeless, helpless, automatic, and unsatisfying. There is a desire to stop, but stopping doesn't feel like an option. Perseverance feels like striving toward a noble goal, and whether or not it's reached, there is virtue in the effort.

Perseverance is a strong, valuable quality. Perseveration is a troubling issue needing clinical attention. Don't let a quaint saying blur this distinction.

Perseveration is a troubling issue needing clinical attention. Don't let a quaint saying blur this distinction.

Who Is the Crazy One?

Source: Pixabay

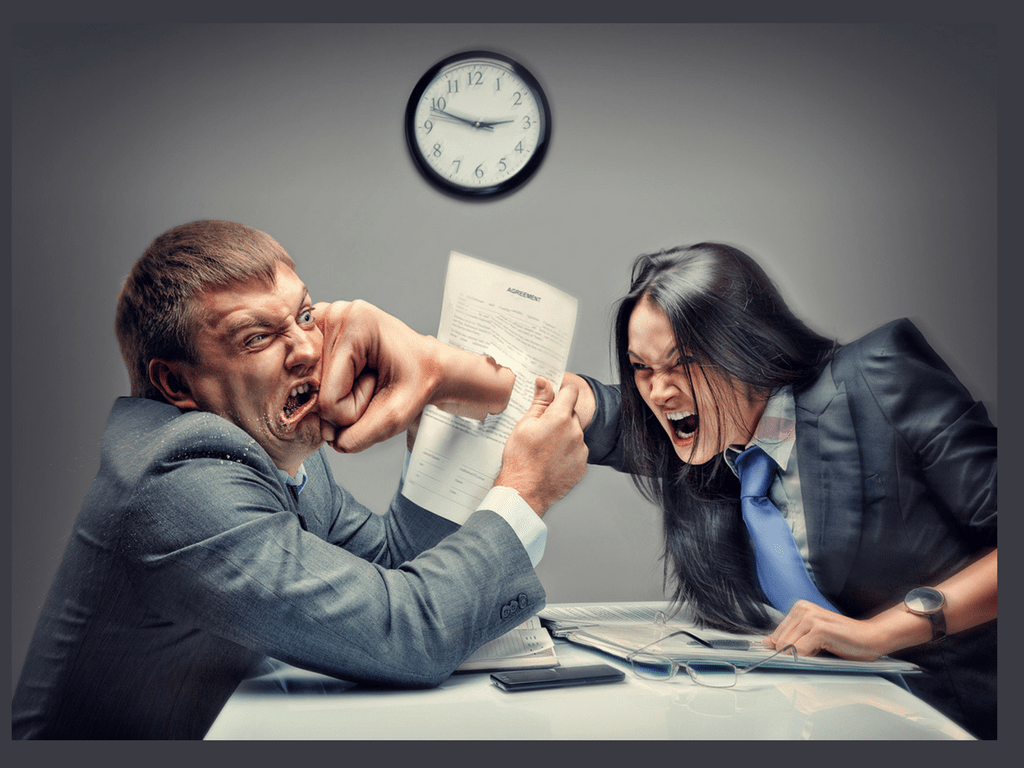

Has anyone ever told you “you’re crazy!”? They could have been referring to a risk you wanted to take, a perspective you had on something, a relationship you were involved in or a change you wanted to make. The word “crazy” is often used, but what does it really mean and when should you apply it? If you search on the definition of “crazy,” the variety of applications is far and wide:

- mentally deranged, especially as manifested in a wild or aggressive way:

- extremely enthusiastic:

- (of an angle) appearing absurdly out of place or in an unlikely position:

In fact, close to 20% of the entire American adult population is clinically diagnosed as mentally ill. They are not necessarily deranged, or even “wild or aggressive,” but they do suffer true mental health issues: “Every year, about 42. 5 million American adults (or 18.2 percent of the total adult population in the United States) suffers from some mental illness, enduring conditions such as depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.”

5 million American adults (or 18.2 percent of the total adult population in the United States) suffers from some mental illness, enduring conditions such as depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia.”

If you have encountered behavior that seems to be absurdly out of place or in an unlikely position, you’ve likely said either audibly or to yourself as self-talk, “that person is crazy.” You may try to avoid them, and do your best to stay as far away as possible.

Assuming you are not encountering someone with a true mental illness, how can you deal more effectively with people when their behavior triggers something in you and, rather than wanting to learn more, you move away in disgust?

There are many reasons you might react to what someone else is doing:

- You wouldn’t do things that way

- They are dramatic or over the top in their emotions and activities

- They don’t make any sense to you

- You have never heard, seen or been around someone “like that”

- They are from a different background, culture and/or point of view

- They act in an offensive or disturbing manner

- They create fear or resistance within you

In many cases, the odd or crazy behavior is due to a disconnect from the way you do things and what you understand to be true. Think about the current political environment – if you are in one camp or the other, you don’t just have a difference of opinion; the other camp considers you to be certifiably crazy in your leanings. When someone has a vastly different viewpoint, the tendency is to portray them as “out there”.

Think about the current political environment – if you are in one camp or the other, you don’t just have a difference of opinion; the other camp considers you to be certifiably crazy in your leanings. When someone has a vastly different viewpoint, the tendency is to portray them as “out there”.

But what if you could learn from the oddities of others? What if, in seeking to understand, you might find a friend you would not have otherwise had? How can you stay more open to recognizing where behavior manifests and how?

Some of the things that make one be crazy include:

- Extreme levels of stress – the person may not have a good way to deal with their life circumstances and they just can’t cope, so instead of turning to stress management like meditation or mindfulness, they act out in emotionally charged ways.

- Rushing or being anxious – people who are late, who have commitments they might not be able to meet, or who worry about what they need to do next can act out in crazy and offensive ways.

The rush never gets anyone to where they need to be more quickly; it just creates behavior that is negative to the person and those around them.

The rush never gets anyone to where they need to be more quickly; it just creates behavior that is negative to the person and those around them. - Misunderstandings or lack of information – sometimes a person holds a certain set of beliefs that cause them to view the world through a colored lens. They don’t see things clearly, so they don’t react in the most objective and level manner.

- Lack of education – not everyone has had the opportunity to go through school and learn, and even those who have may not have learned all they need to know to deal with the events of the world most effectively.

- Past history or familial origins – many people carry baggage from their upbringing or childhood experiences. They carry over difficulties or beliefs that no longer serve them well, but that they don’t know how to discard.

- Underdeveloped communication skills – many people speak well in their heads, but don’t do a great job of speaking to others and communicating their true thoughts and feelings.

They hide things, or try to shade them, and in doing so, can appear in a negative and even mistrusting manner.

They hide things, or try to shade them, and in doing so, can appear in a negative and even mistrusting manner. - Fear – the great motivator for most all negative behavior in anyone is a basis of fear; fear of losing something, fear of embarrassment, fear of death and many, many others. When a person is fearful, they can’t possibly think and act in a rational way. The fear drives the behavior.

These are just a few of the drivers behind behavior you might interpret as negative or “crazy.” All human beings experience one of these at one point or another, and all act in less than optimal ways. To avoid your own upset and emotional reactions, take a step back the next time you meet someone whom you consider to be crazy and see if you might be able to unpack what’s underneath the surface. This is the true definition of compassion and care – and as an added bonus, it allows you to move from a negative and reactionary state to a more interested, objective one.

WELL, AND WHO IS CRAZY HERE?.

40 studies that shook psychology

40 studies that shook psychology WELL, WHO IS CRAZY HERE?

Base materials: Rosenhan D. L. (1973). On being sane in insane places. Science, 179 , 250–258

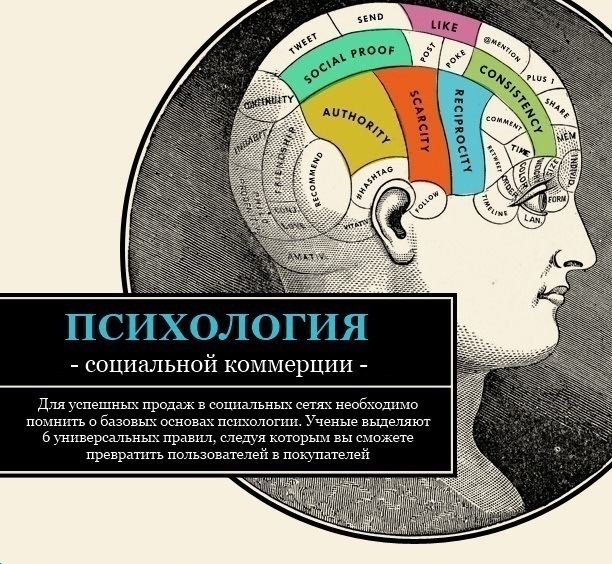

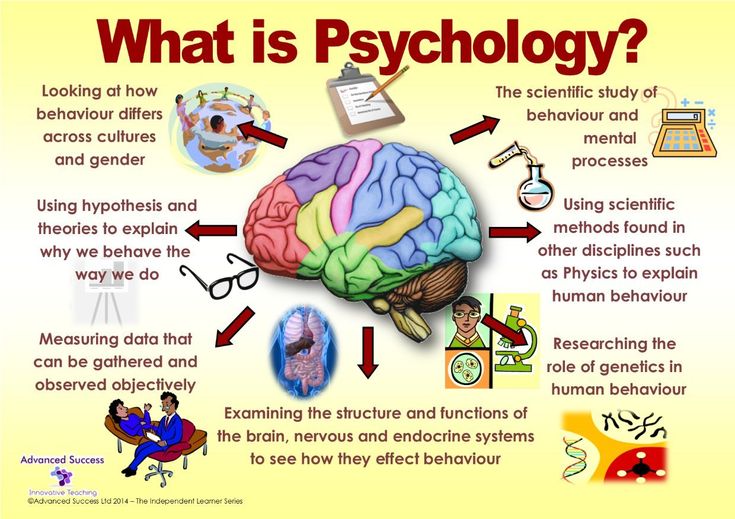

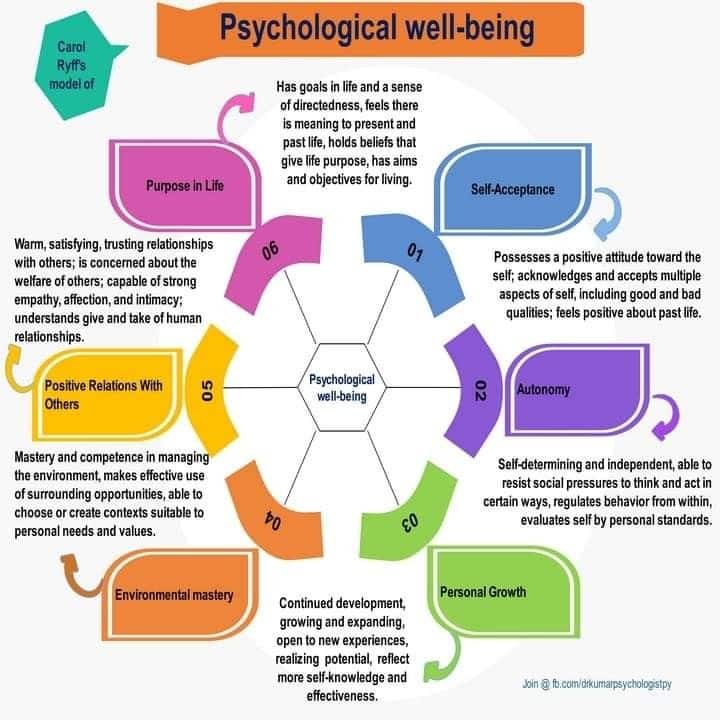

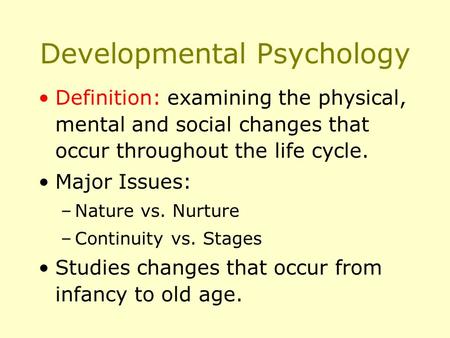

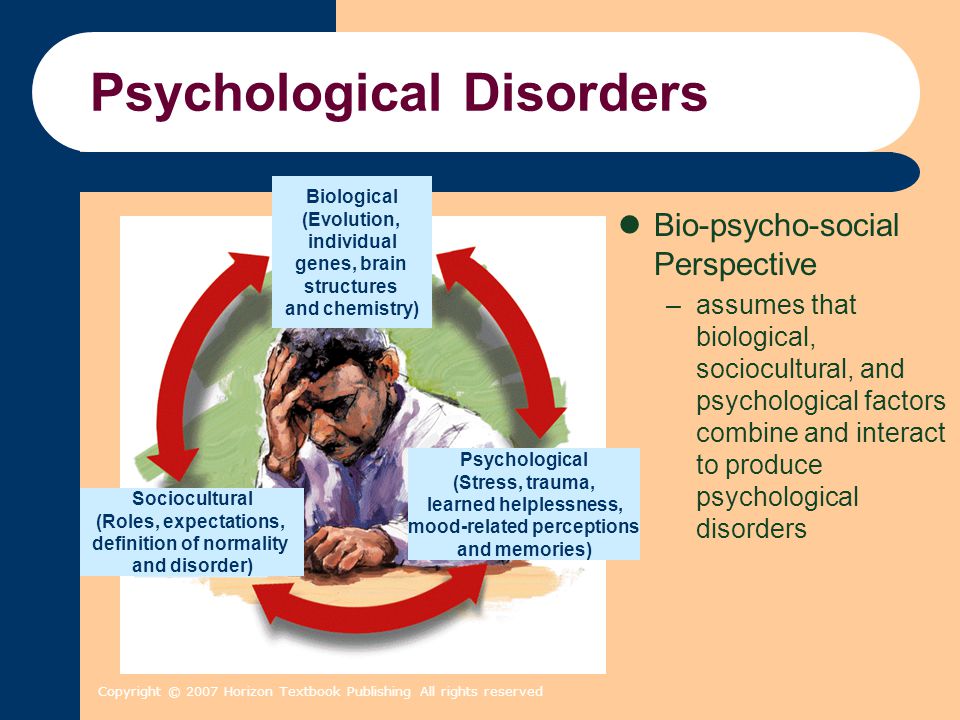

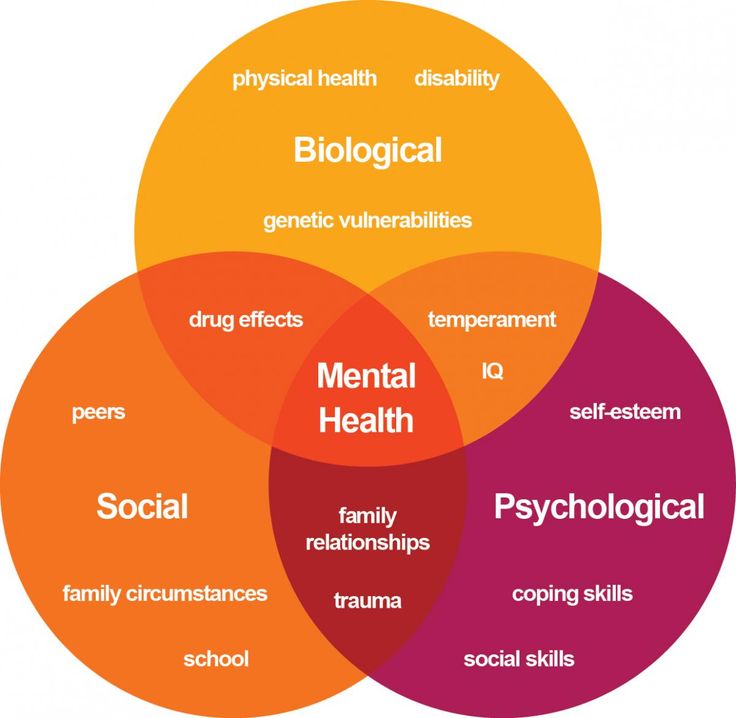

The question of how to distinguish normal from pathological behavior is fundamental in psychology. Determining what is a pathology plays a key role in understanding whether a person is mentally ill, and the diagnosis largely determines the treatment of the patient. The boundary separating normal behavior and pathology is very indistinct. Rather, one can imagine all human behavior as a kind of continuum, at one end of which is the norm, or what can be called effective psychological functioning , and at the other end - pathology, meaning mental illness (Fig. 1).

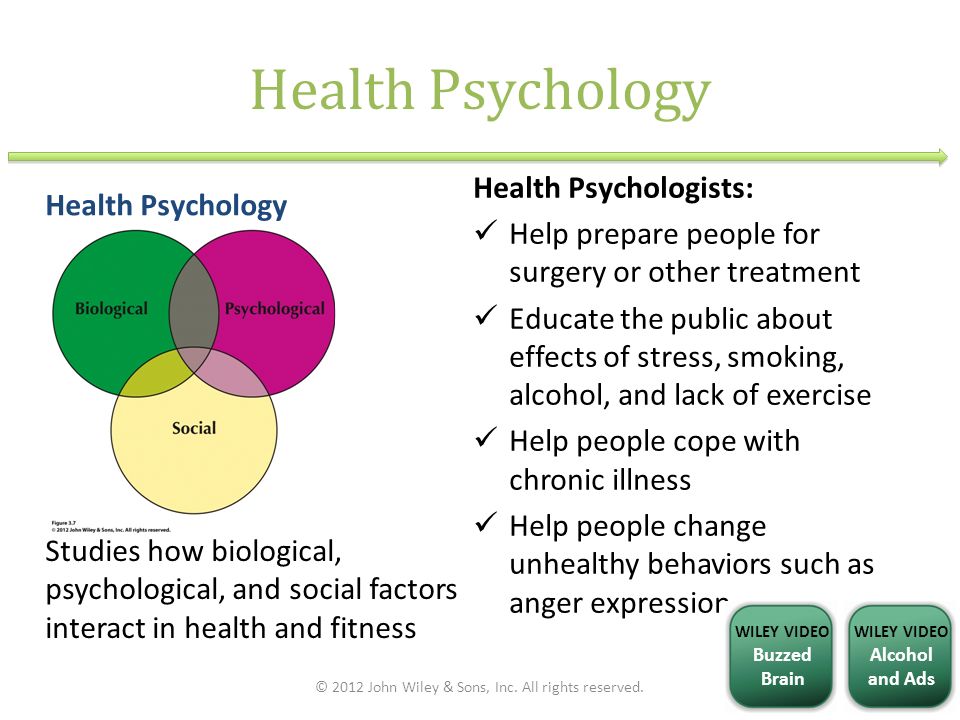

Mental health professionals must determine where on this continuum a particular person's behavior generally lies. Clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychotherapists may use one or more of the following criteria to make a decision.

Strange behavior . This is a subjective judgment, but you yourself know that in certain situations this or that behavior is clearly strange. For example, it's not unusual for you to go out and water the lawn in front of it, but things change when it happens when it's pouring rain! So, in order to judge the strangeness of behavior, it is necessary to take into account the circumstances in which it occurs. nine0003

Constancy of behavior. We all have moments of "madness". It is possible that a person on some occasion behaves unusually and strangely, and this need not be seen as evidence of mental illness. For example, you received some very important news, and now, walking along the sidewalk in the city center, you start dancing, and so you dance a quarter or two. This behavior, of course, is not normal, but it does not mean mental illness, unless you dance on this sidewalk regularly, day after day or every week. Therefore, this criterion for mental illness requires that the bizarre, antisocial, or disruptive behavior be continuous. nine0003

nine0003

Social deviation. When a person's behavior deviates radically from what is expected and normal, the criteria for social deviance may apply. When behavioral deviations reach extremes and last for a long time, for example, a person has auditory or visual hallucinations, this is evidence of mental illness.

Mental suffering. Often we, as intelligent creatures, are ourselves aware of our psychological difficulties and the suffering they cause us. When a person is afraid of a closed space, cannot use an elevator, or feels that he is not capable of deep and vital relationships with other people, he himself, without the help of a psychologist or psychiatrist, understands that he has psychological problems and that it hurts him . Often the fact and specificity of such suffering is of great help to specialists so that they can make a psychological diagnosis. nine0003

Psychological obstacles. When a person finds that it is impossible for him to be satisfied with life because of his psychological problems, this is considered as a psychological obstacle. For example, a person who is afraid of success and therefore gives up trying to change something in life suffers from a psychological obstacle.

For example, a person who is afraid of success and therefore gives up trying to change something in life suffers from a psychological obstacle.

Effect on functioning. This criterion is most important for psychological diagnosis: the extent to which the questionable behavior affects the person's ability to live the life he wants for himself and that is acceptable to society. A person's behavior can be strange, and strange all the time, but if it does not affect the person's ability to live and act in any way, then perhaps there is no true pathology here. For example, suppose you have an overwhelming desire to get up in bed every night before going to bed and sing the national anthem; most likely, this behavior of yours does not disturb the neighbors and has very little effect on your life in general, and therefore may not be a clinical problem. nine0003

The extent to which a person exhibits all of these symptoms and characteristics of mental illness is for psychologists, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals to decide. Therefore, despite the figures presented above, two questions remain: Can mental health professionals really tell the difference between a mentally ill person and a healthy person? And what are the consequences of mistakes? These are the questions that David Rosenhan asked himself.

Therefore, despite the figures presented above, two questions remain: Can mental health professionals really tell the difference between a mentally ill person and a healthy person? And what are the consequences of mistakes? These are the questions that David Rosenhan asked himself.

Theoretical foundations

Rosenchen wondered whether the characteristics leading to a psychological diagnosis refer to the patients themselves or to the situations and concomitant circumstances in which the observers (those who make the diagnosis) see these patients. He reasoned that if the accepted criteria and experience that professionals have in diagnosing mental illness are adequate, then those professionals should be able to distinguish between a mentally healthy person and an insane person. (Words like healthy and mentally ill are terms not used by psychologists. These words are used here because Rosenhan uses them in his work.) Rosenhan proposed the only way, from his point of view, to test the ability of specialists to correctly diagnose - to arrange so that normal people get into hospitals for the mentally ill, and see if there will be it is found that these people are in fact healthy. If "pseudopatients" behaved in the hospital as they do in normal life, and none of the hospital staff realized that these people are completely normal, this would be evidence that the diagnosis of mental illness is actually more related to the situation than with the patient. nine0003

If "pseudopatients" behaved in the hospital as they do in normal life, and none of the hospital staff realized that these people are completely normal, this would be evidence that the diagnosis of mental illness is actually more related to the situation than with the patient. nine0003

Method

Rosenchen recruited eight people (including himself) to be pseudopatients. Of the eight participants in the experiment (three women and five men), one was a graduate student, three were psychologists, one was a pediatrician, one was a psychiatrist, one was an artist, and one was a housewife. The participants' task was to get an appointment at one or more of 12 hospitals for the mentally ill in five states on both the east and west coasts of the United States. nine0003

All pseudopatients followed the same instructions. They called the hospital and asked to be admitted. When they arrived at the institution, they complained that they heard voices that said to them the words: "empty", "hollow" and "stupid". Apart from this single symptom, all participants in the experiment behaved perfectly normally and gave absolutely truthful information about themselves (except that they gave other names and other occupations). All subjects were admitted to different hospitals, and all but one were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia .

Apart from this single symptom, all participants in the experiment behaved perfectly normally and gave absolutely truthful information about themselves (except that they gave other names and other occupations). All subjects were admitted to different hospitals, and all but one were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia .

Once in the hospital, the pseudopatients did not show any symptoms of mental illness and behaved absolutely normally. They had no idea when they would be allowed to leave the hospital. They had to seek their own discharge by convincing the hospital staff that they were healthy enough to do so. All subjects kept diaries with notes. At first they tried to hide it, but it soon became clear that there was no need for such secrecy, since this was the behavior of the subjects (recording what happened ) was considered as another symptom of the disease. All subjects wanted to be released as soon as possible, so they behaved like model patients, followed the instructions of the staff and took all the medicines prescribed for them (which, however, they did not take, but flushed down the toilet).

Results

The length of hospital stay for pseudopatients ranged from seven to 52 days, with an average of 19 days. The most important result of this experience is that none of the pseudopatients aroused the suspicion of any of the hospital staff. When they were discharged, schizophrenia in remission. Other results and observations have been received.

While the hospital staff—doctors, nurses, and attendants—couldn't figure out the pseudosick, it wasn't easy to fool the other patients. In three cases of hospitalization of pseudopatients, 35 of 118 real patients expressed suspicions that the subjects were not in fact mentally ill. "You're not crazy at all! Are you a journalist or reporter? And you check what is being done in this hospital!” nine0003

Contacts between patients (subjects and non-subjects) and hospital staff were minimal and often quite bizarre. One of the tests done in this study by pseudopatients was to go up to different people from the hospital staff and try to make verbal contact with them, asking the most common, normal questions (for example, "When will I be allowed to go out?" or " When will they let me out of here?" In table. 1 presents the responses received.

1 presents the responses received.

Table 1

Responses of doctors and medical staff to questions from pseudopatients

The answer, when given, often took the following form:

Pseudopatient: Excuse me, doctor_, can you tell me when I can go for a walk?

Psychiatrist: Good morning, Dave. Well, how are you today?

Then the doctor, as a rule, left without waiting for an answer.

In the hospitals studied, patients had very little personal contact with staff, but there was no shortage of medicines. In this trial, eight pseudopatients received a total of 2100 tablets, which, as already mentioned, were not swallowed. Subjects noticed that many real patients also quietly flushed the pills down the toilet. nine0003

One of the pseudopatients told a funny story about a nurse who unbuttoned her gown to adjust her bra in a room full of male patients. There was nothing provocative in her intentions, she just did not consider patients to be people.

Discussion

Rosenhan's research showed that in a psychiatric hospital, normal people are indistinguishable from mental patients. Rosenhan believes that this is due to the very environment in this kind of institution - it has a strong influence on the judgments of the staff about the behavior of the individual. Once patients are admitted to the hospital, they will be treated as patients, there will be no individual approach. The usual attitude towards patients can be expressed as follows: "Since they got here, they must be crazy." More importantly, Rosenchen calls the by affixing a diagnostic label: the diagnosis becomes the main characteristic of the person or his personal feature. (See discussion of S. Asch's 1946 study "Making a Good Impression" in Chapter 4.) Once a label is diagnosed and recognized by hospital staff, everyone perceives the person's behavior as a direct consequence of the label; hence the inattention to the fact that the patient keeps some records. The fact that this fact does not arouse suspicion is evidence that record keeping simply becomes for the staff, as it were, another manifestation of the patient's illness, confirmation of the label. nine0003

The fact that this fact does not arouse suspicion is evidence that record keeping simply becomes for the staff, as it were, another manifestation of the patient's illness, confirmation of the label. nine0003

Hospital staff tend to ignore the possibility of situational influences on patients and only see the pathological features that a given patient should have according to the diagnosis. This was demonstrated by the following observation of one of the subjects:

“One psychiatrist drew attention to a group of patients sitting at the entrance to the hospital cafeteria half an hour before opening. He began to explain to a group of young psychiatric practitioners that the symptom of increased appetite is characteristic of a certain syndrome. It seems that the doctor did not even think that between meals in a psychiatric hospital there is simply nothing to do” (p. 253). nine0003

In addition, the glued diagnostic label generally often colored the interpretation of the life history of the pseudopatient. Remember that all subjects have been honest about their backgrounds and their families. Here is an example of a life story told by one of the pseudopatients, and the interpretation given to her by the hospital physician in his report upon the subject's discharge. In fact, the subject-pseudopatient said the following about himself:

Remember that all subjects have been honest about their backgrounds and their families. Here is an example of a life story told by one of the pseudopatients, and the interpretation given to her by the hospital physician in his report upon the subject's discharge. In fact, the subject-pseudopatient said the following about himself:

“In early childhood he had a very close relationship with his mother, but he was quite distant from his father. However, in adolescence and youth, it was his father who became a true friend for him, and relations with his mother became cooler. At the time of admission to the hospital, his relationship with his wife was generally close and warm. Children were rarely punished” (p. 253). nine0003

The attending physician gave the following interpretation of this, in general, completely normal and harmless story:

“This white 39-year-old man ... from early childhood began to show the instability of close relationships with other people. Relations with his mother were at first very warm, but cooled in adolescence. The relationship with the father, which was not at all close in childhood, becomes very good over time. There is no real stability. He tries to control his emotions in relation to his wife and children, but from time to time he has quarrels with his wife, and he punishes the children. And although he claims to have several good friends, it is felt that here, too, everything is unstable and unstable to a large extent” (p. 253). nine0003

The relationship with the father, which was not at all close in childhood, becomes very good over time. There is no real stability. He tries to control his emotions in relation to his wife and children, but from time to time he has quarrels with his wife, and he punishes the children. And although he claims to have several good friends, it is felt that here, too, everything is unstable and unstable to a large extent” (p. 253). nine0003

There is no evidence that the facts presented by the pseudopatients were intentionally misrepresented by the hospital staff. It's just that people were confident in the correctness of the diagnosis (in this case, schizophrenia), and the patient's life history, as well as his behavior, was interpreted in accordance with this diagnosis.

Significance of the findings

Rosenhan's study shocked many psychiatrists. The results revealed two important factors. First, it turned out that specialists in psychiatric hospitals are not always able to distinguish between mentally healthy people and sick people. According to Rosenhan, “The hospital itself, as a rule, presents such a specific environment for a person that it is very easy to misunderstand the behavior of any patient here. The fact that during hospitalization people find themselves in such an environment ... probably has a far from curative effect on them ”(p. 257). Second, Rosenhan showed the dangers of diagnostic labels. Once a patient is diagnosed with a specific diagnosis (such as schizophrenia, manic-depressive psychosis, etc.), this label, as it were, obscures all other personality traits. It seems that a person's behavior and all his characteristic features stem from mental disorders that have received the label of diagnosis. The worst thing about this style of treatment is that the labeled patient becomes established in his illness. When he is treated as a person with certain mental disorders, over time he begins to behave exactly as expected of him. nine0003

According to Rosenhan, “The hospital itself, as a rule, presents such a specific environment for a person that it is very easy to misunderstand the behavior of any patient here. The fact that during hospitalization people find themselves in such an environment ... probably has a far from curative effect on them ”(p. 257). Second, Rosenhan showed the dangers of diagnostic labels. Once a patient is diagnosed with a specific diagnosis (such as schizophrenia, manic-depressive psychosis, etc.), this label, as it were, obscures all other personality traits. It seems that a person's behavior and all his characteristic features stem from mental disorders that have received the label of diagnosis. The worst thing about this style of treatment is that the labeled patient becomes established in his illness. When he is treated as a person with certain mental disorders, over time he begins to behave exactly as expected of him. nine0003

Thanks to Rosenhan's work, psychiatrists make diagnoses more carefully and thoroughly, and they have also become more aware of the dangers of labeling a diagnosis when there is no longer a person behind the diagnosis. It can also be noted that a number of problems raised in the study no longer exist due to a decrease in the number of patients held in psychiatric hospitals. Psychological drugs have been discovered and widely used that can significantly reduce the symptoms of diseases in many patients, which allows the latter to live outside hospitals and lead a relatively normal life. At the same time, there are more local psychiatric and crisis centers, targeted therapies for each type of problem behavior, and specialists generally try to avoid any labels. nine0003

It can also be noted that a number of problems raised in the study no longer exist due to a decrease in the number of patients held in psychiatric hospitals. Psychological drugs have been discovered and widely used that can significantly reduce the symptoms of diseases in many patients, which allows the latter to live outside hospitals and lead a relatively normal life. At the same time, there are more local psychiatric and crisis centers, targeted therapies for each type of problem behavior, and specialists generally try to avoid any labels. nine0003

This in no way suggests that psychiatrists have completely abandoned diagnostic labels. However, thanks mainly to the work of Rosenhan and other researchers in the same field, labels in psychiatry are now used carefully and with an understanding of the power they have.

Questions and criticisms

One of the research and teaching hospitals learned about the results of the Rosenhan study before they were published, and the hospital staff doubted that such misdiagnosis could occur in their institution. To test this, Rosenhan informed the hospital administration that one or more pseudopatients would try to get into their hospital over the next three months. All staff members were asked to rate each patient who arrived at the hospital on a 10-point scale, noting the likelihood that the person might be a pseudopatient. By the end of the three-month period, 19 patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment.3 patients. Of these, 41 patients were identified with more or less certainty as pseudopatients by at least one person on the hospital staff. Twenty-three were questioned by at least one psychiatrist, and 19 were identified as pseudopatients by one psychiatrist and another member of the hospital staff. Rosenchen (the deceiver!) actually did not send any pseudo-patients to the hospital during these three months! “This experiment is very instructive,” says Rosenhan. “He shows that the tendency to think healthy people are sick can also be reversed when the stakes are high enough (in this case, the experts were worried about their prestige and tried to demonstrate how good they were at diagnosing).

To test this, Rosenhan informed the hospital administration that one or more pseudopatients would try to get into their hospital over the next three months. All staff members were asked to rate each patient who arrived at the hospital on a 10-point scale, noting the likelihood that the person might be a pseudopatient. By the end of the three-month period, 19 patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment.3 patients. Of these, 41 patients were identified with more or less certainty as pseudopatients by at least one person on the hospital staff. Twenty-three were questioned by at least one psychiatrist, and 19 were identified as pseudopatients by one psychiatrist and another member of the hospital staff. Rosenchen (the deceiver!) actually did not send any pseudo-patients to the hospital during these three months! “This experiment is very instructive,” says Rosenhan. “He shows that the tendency to think healthy people are sick can also be reversed when the stakes are high enough (in this case, the experts were worried about their prestige and tried to demonstrate how good they were at diagnosing). But one thing is certain: any diagnostic process that so easily leads to large errors of this sort cannot be considered very reliable” (p. 252). nine0003

But one thing is certain: any diagnostic process that so easily leads to large errors of this sort cannot be considered very reliable” (p. 252). nine0003

Rosenchen repeated his study several times, for a total of 12 hospitals in the period 1973-1975.

He got the same results every time (see Greenberg, 1981, and Rosenhan, 1975). However, other scientists have disputed Rosenhan's conclusions from this study. Spitzer (1976) argued that while Rosenchen's methods might appear to reveal flaws in the psychological diagnostic system, they actually do not. For example, it was easy for pseudopatients to get into hospitals because many real patients get there on the basis of verbal messages (and who would think that a person is trying to fraudulently get into such a place?). The reasoning here is that if you go to the doctor's office and complain of severe bowel pain, you may end up in the hospital with a diagnosis of gastritis, appendicitis, or an ulcer. Even if you deceived the doctor, diagnostic methods (i. e., a diagnostic conversation between a doctor and a patient. — Note ed.) were not false. In addition, Spitzer pointed out that although pseudopatients behaved quite normally when they were admitted to hospitals, such variations in behavior in mental disorders are quite common, and this does not mean at all that the hospital staff demonstrated their incompetence without exposing the deception.

e., a diagnostic conversation between a doctor and a patient. — Note ed.) were not false. In addition, Spitzer pointed out that although pseudopatients behaved quite normally when they were admitted to hospitals, such variations in behavior in mental disorders are quite common, and this does not mean at all that the hospital staff demonstrated their incompetence without exposing the deception.

The debate about the importance of diagnoses in psychiatry, which began with Rosenhan's 1973 article, continues. Regardless of what modern scientists manage to do, it is clear that Rosenhan's research remains one of the most important in the history of psychology. nine0003

Modern developments

Rosenchen's experiment, which called into question the reliability of psychiatric diagnoses, has been used in the work of many researchers; we mention here the work of two of them. One paper is by Thomas Szasz, a psychiatrist who has been known since the early 1970s for his critique of the concept of mental illness. He was convinced that mental disorders were not a disease and could not be properly understood as a disease; rather, they should be seen as problems existence (problems in living), having their own social causes, as well as causes related to the immediate environment. In one of his articles, Szasz says that if one person (the psychiatrist) cannot understand the other (the patient), "this is no reason to believe that the patient is sick" (Szasz, 1993, p. 610).

He was convinced that mental disorders were not a disease and could not be properly understood as a disease; rather, they should be seen as problems existence (problems in living), having their own social causes, as well as causes related to the immediate environment. In one of his articles, Szasz says that if one person (the psychiatrist) cannot understand the other (the patient), "this is no reason to believe that the patient is sick" (Szasz, 1993, p. 610).

Another study, based on Rosenhan's 1973 papers, looked at how patients themselves feel when labeled as mentally ill (Wahl, 1999). The study involved more than 1,300 people diagnosed with mental disorders. They were asked how they felt about being stigmatized as mentally ill, and whether they felt they were being discriminated against in any way. Most of the patients answered that they actually feel their illness as a stigma, and, moreover, they feel it to a very strong extent in the general attitude of those around them, the attitude of family members, the church parish, colleagues, and even the psychiatrists themselves. In addition, the author of the study notes, “the majority of respondents tried to hide their mental disorders and were very worried that people would not find out that they were mentally ill and would treat them worse. They confessed that they felt insecure, bitter, embittered, and rated themselves low” (p. 467). nine0003

In addition, the author of the study notes, “the majority of respondents tried to hide their mental disorders and were very worried that people would not find out that they were mentally ill and would treat them worse. They confessed that they felt insecure, bitter, embittered, and rated themselves low” (p. 467). nine0003

We may indeed be making some progress in the public sphere. In a study by Boisvert and Faust (1999), subjects were presented with imaginary scenarios of an employee of a firm who was very rude to his boss. The scenarios varied in how much stress the employee experienced, and in some scenarios the employee was described as having previously been diagnosed with schizophrenia. The researchers thought that subjects were more likely to attribute employee rudeness to personality traits when the label of schizophrenia was present; if there is no evidence of mental illness in the script, the cause will be looked for in a stressful environment. Now guess what happened. It turned out that the subjects evaluated the events of the scenario in the opposite way. They condemned the personality of our employee the less, the more - according to the script - he had to experience stress, regardless of from having a label of schizophrenia. And what's more, the researchers got almost the same results when the participants were actual practicing psychiatric clinicians or college students.

They condemned the personality of our employee the less, the more - according to the script - he had to experience stress, regardless of from having a label of schizophrenia. And what's more, the researchers got almost the same results when the participants were actual practicing psychiatric clinicians or college students.

So, we can say that we have reason to rejoice - after all, the results of these experiments show that in our society there is more tolerance and understanding towards people with mental disabilities. The reality is that, until now, the diagnosis of mental illness continues to be as much an art as it is a science. It's unlikely that we'll ever be done with labels ; they seem to be a necessary part of the effective treatment of psychological disorders, just as the names of diseases are part of the diagnosis and treatment of physical diseases. So, if we can't get rid of the labels altogether, we should keep working and try to make sure that the diagnosis does not turn into a stigma, does not make a person feel insecure and ashamed.

Business course, or the Crazy House on the Arbat What is the task There are many people who want to earn money, and there are psychologists who undertake to help them with this. And they charge good money for it. Right! Many people wanted to get to this instructor: it works brightly, coolly and

I remember here, I don't remember here...

I remember here, I don't remember here... According to the Wall Street Journal, American scientists have discovered a special gene that in each case solves an extremely topical issue for people of intellectual labor: whether to forward new information from short-term

4. HERE AND NOW

4. HERE AND NOW Orthodox psychotherapy is based on the implicit assumption that a neurotic is a person who once had problems, and that the goal of therapy is to resolve these problems that occurred in the past. This is the assumption that

HERE AND NOW Orthodox psychotherapy is based on the implicit assumption that a neurotic is a person who once had problems, and that the goal of therapy is to resolve these problems that occurred in the past. This is the assumption that

Chapter 7 nine0002 Chapter 7 Truly, today Russia smells so much that no air freshener helps. Because it smells mainly not of Russia, but of Slavophilism of the most obscurantist persuasion. That television, carefully avoiding

Relationships with relatives, or how to turn your house into a crazy

Relationships with relatives, or How to turn your house into a crazy one They say that families that started life in the parental home disintegrate either very quickly or never... According to an old custom, it is customary for a husband to bring a young wife to his parents'0003

About what luck has to do with it

About what luck has to do with it Exactly so according to the formula: Perfection multiplied by Luck. For it turns out that if, for example, we accept as a working definition that the perfection of a person is a certain function of his education and abilities, and luck is directly

For it turns out that if, for example, we accept as a working definition that the perfection of a person is a certain function of his education and abilities, and luck is directly

I have nothing to do with it

nine0002 I'm here for nothing The opposite of the previous category are people who chronically refuse to accept any responsibility for the problems that arise. When they receive feedback or face setbacks, they quickly find who they areGenius or crazy?

Genius or crazy? The man sitting across from me nearly drove me crazy. He showed both manner and style - his clothes were surprisingly monotonous, as if he, like a chameleon, wanted to blend into the faded wall in a hotel room in Toronto. He looked like a gnome and mumbled monotonously, looking

54 I have a question that torments me: "Am I crazy or is everyone else?"

54 I have a question that torments me: "Am I crazy or is everyone else?" In one of his famous discourses, the Buddha argued that being angry is like grabbing a hot coal to throw at someone. As a result, you yourself will get burned. Albert

As a result, you yourself will get burned. Albert

11. WHO IS HERE? nine0169

11. WHO IS HERE? As you put in a lot of time and effort to work on yourself, you will begin to discover a greater, more comprehensive process of meditation. If you follow your process for a long time, you will come to know about two different types of awareness:

I have nothing to do with it, mate

I don't belong here, buddy Study the history of commerce. You will definitely find that in any economic climate, the winners in one way or another are those who take their duties seriously: they work in exactly the segment that they really think

What does love have to do with it

What is love here A simple test that has saved millions of families Susanna Romo was finally happy. Together with her husband Ernie, they lived in a sunny home on the Pacific coast in Chula Vista, a city located in San Diego County, California. They had a spacious

Together with her husband Ernie, they lived in a sunny home on the Pacific coast in Chula Vista, a city located in San Diego County, California. They had a spacious

If you are talking to yourself, you are crazy. If you are talking to your computer, you are normal. If you're talking to your car, it's time to buy a new one

If you are talking to yourself, you are crazy. If you are talking to your computer, you are normal. If you're talking to your car, it's time to buy a new one Imagination is the most efficient way to predict the behavior of other objects. We endow them with our

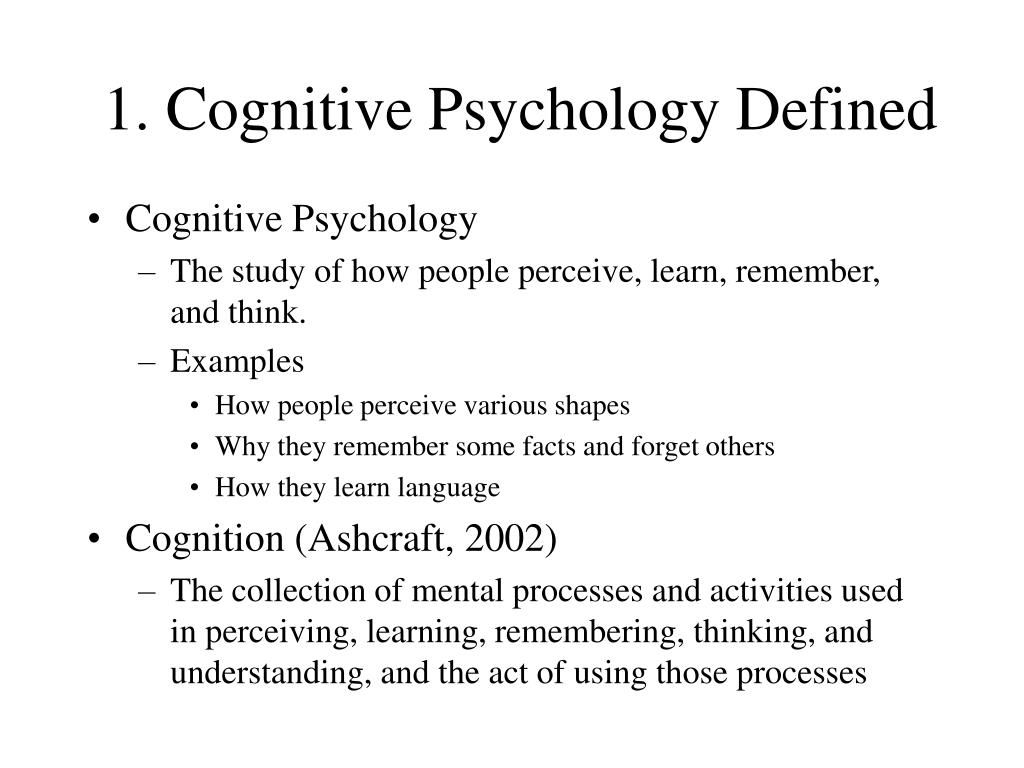

Personality and activity: briefly about Rubinstein's theory

Almost 90 years ago, Sergei Rubinshtein proposed an idea that laid the foundation for the scientific approach in Soviet psychology. He was one of the first among domestic scientists to put forward the principle of the unity of consciousness and activity. The theory is that consciousness induces a person to perform certain actions, and they, in turn, form his consciousness. So Soviet psychology switched to scientific experiments in which the human psyche was studied through its behavior. nine0003

The theory is that consciousness induces a person to perform certain actions, and they, in turn, form his consciousness. So Soviet psychology switched to scientific experiments in which the human psyche was studied through its behavior. nine0003

Rubinstein outlined his theory in the book Fundamentals of General Psychology. In the same place, he summarized and analyzed almost the entire experience of world research in this scientific field. This book has become one of the best domestic textbooks on general psychology and a source of knowledge for many generations of specialists. Let us briefly talk about the principle of the unity of consciousness and activity, as well as the related concept of personality according to Rubinstein.

Prior theories

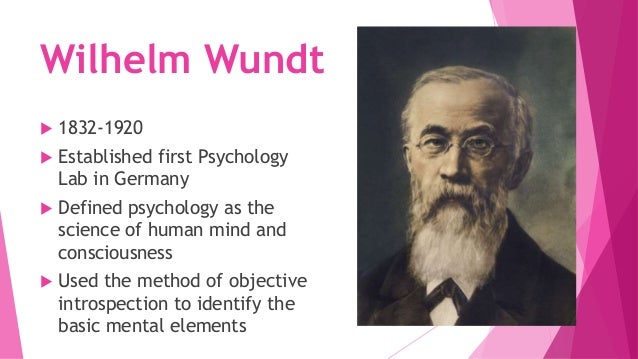

Philosophers have long argued about how the mental and the physical are related. The mathematician Rene Descartes, who sharply contrasted matter and spirit as two different entities, put an end to this issue at one time. This idea changed slightly, but still lived and flourished until the 20th century. It dominated Russian psychology until the 1930s.

This idea changed slightly, but still lived and flourished until the 20th century. It dominated Russian psychology until the 1930s.

Over time, evidence has emerged that the mind and body are interconnected. For example, scientists have seen that damage to various parts of the brain leads to impaired mental functions. But even then, domestic psychologists did not change the Cartesian tradition. They managed to explain the new facts in two ways. nine0003

The theory of psychophysical parallelism asserted that the mental and the physical constitute two series of phenomena independent of each other, which simply accompany each other. The mental phenomenon corresponds to the physical, but is not connected with it. Human consciousness in this sense is just a shadow of real physical processes, a side effect that is devoid of any power.

The theory of interaction recognized that the mental and physical are connected, but also only externally. For example, strong emotions can lead to changes in the body. But this connection was considered purely mechanical. They didn't see any value in it. Mind and physiology were still treated separately. nine0003

But this connection was considered purely mechanical. They didn't see any value in it. Mind and physiology were still treated separately. nine0003

11/22/2019 Books

Activities according to Rubinstein

Such a view of the problem prevented psychology from becoming a science. Until now, it has been reduced to philosophical reflections that could not be substantiated. But when Rubinstein declared that the physical and mental are two sides of the same process, he opened scientific methods to Soviet psychology. After all, one can observe a person’s behavior and draw conclusions about his psyche. Therefore, the scientist put the concept of activity at the head of his principle of unity. nine0003

According to Rubinstein, activity is an action and occupation by which a person transforms reality. For example, work, study or play. According to Rubinstein's theory, the psyche and activity are not in equal relations. The second of them is primary. Of course, a person's thinking, imagination and feelings influence his view of the world. But they, in turn, are formed as a result of his actions.

But they, in turn, are formed as a result of his actions.

To learn more about mental processes, you can observe the behavior of people in certain conditions. Such experiments have already been carried out abroad. For example, scientist Henry Ruger in 19In 10, he studied how subjects solve a mechanical puzzle. Participants in the experiment at first apparently tried to solve the problem at random. But after each unexpected success, they comprehended it and allowed less and less unnecessary movements. Such an interweaving and interaction of random and conscious attempts is characteristic of the formation of a skill in a person.

Thus, a skill is an action that is transferred from one situation to another. But also the thought process, because its development requires generalization. nine0003

11/23/2018 Reviews

Personality according to Rubinstein

It is formed and manifested in activity. To understand how this happens, you need to turn to mental processes. These include thinking, memory, sensations, perception, imagination, speech, attention, emotions and will. All of them are interconnected, since they develop simultaneously as a person grows up and life circumstances change. Over time, they become mental functions of the individual, that is, operations that a person can regulate. For example, perception in the course of personality development turns into observation, and involuntary imprinting is replaced by conscious memorization. nine0003

These include thinking, memory, sensations, perception, imagination, speech, attention, emotions and will. All of them are interconnected, since they develop simultaneously as a person grows up and life circumstances change. Over time, they become mental functions of the individual, that is, operations that a person can regulate. For example, perception in the course of personality development turns into observation, and involuntary imprinting is replaced by conscious memorization. nine0003

In the course of activity, mental processes turn into personality traits. They are individual for each person and partly depend on the characteristics of the human nervous apparatus. Mental properties include features of perception, thinking, memory and others. For example, receptivity and impressionability, observation, thoughtfulness, prudence and emotional excitability. They determine the abilities, character and orientation of the individual. The latter includes motives that induce a person to act. For example, needs, interests, ideals and the position taken by a person in relation to his goals and objectives are his attitudes. nine0003

For example, needs, interests, ideals and the position taken by a person in relation to his goals and objectives are his attitudes. nine0003

06/28/2019 Authors

So, according to Rubinstein, personality consists of three aspects:

- Orientation. What does a person want, what is attractive to him, what does he aspire to?

- Abilities and talents. What can a person do?

- Character. Which of the ideals, attitudes and needs was fixed as features of his personality?

More - in the book "Fundamentals of General Psychology" by Sergei Rubinstein.

11/21/2019Books

Tell your friends:

Send news

to email:

Review Policy

Welcome to the Community of Readers! We always welcome your feedback on our books, and we invite you to share your impressions directly on the website of the AST publishing house. Our site has a review pre-moderation system: you write a review, our team reads it, after which it appears on the site. In order for a review to be published, it must follow a few simple rules:

In order for a review to be published, it must follow a few simple rules:

1. We want to see your unique experience

On the book page, we will publish unique reviews that you personally wrote about a particular book you read. You can leave general impressions about the work of the publishing house, authors, books, series, as well as comments on the technical side of the site in our social networks or contact us by mail [email protected].

2. We are for courtesy

If you didn't like the book, explain why. We do not publish reviews containing obscene, rude, purely emotional expressions addressed to the book, author, publisher or other users of the site. nine0003

3. Your review should be easy to read

Write texts in Cyrillic, without extra spaces or incomprehensible characters, unreasonable alternation of lowercase and uppercase letters, try to avoid spelling and other errors.

4. Reviews must not contain third-party links

We do not accept reviews that contain links to any third-party resources.

5. For comments on the quality of publications, there is a "Complaint book" button. the form "Give a complaint book." nine0003

If you encounter missing or out-of-order pages, a defect in the cover or inside of the book, or other examples of typographical defects, you can return the book to the store where it was purchased. Online stores also have the option of returning defective goods, check with the respective stores for details.

6. Review - a place for your impressions

If you have questions about when the continuation of the book you are interested in will be released, why the author decided not to finish the cycle, whether there will be more books in this design, and other similar ones - ask us at social networks or by mail [email protected]. nine0003

7. We are not responsible for the operation of retail and online stores.

In the book card, you can find out which online store the book is in stock, how much it costs, and proceed to purchase.