Contract for safety mental health

The Suicidal Client: Contracting for Safety

One of my colleagues angrily shared a story about a friend of hers. The friends father had been despondent ever since his wife died a few months ago. He told his daughter that it would be better if he just ended it all and joined his wife.

The daughter was sufficiently alarmed to take him to the local emergency room. There, he was interviewed and asked to sign a Contract for Safety, promising that he wouldnt harm himself. He sighed. He signed. And he was sent home.

His daughter was beside herself: Of course he signed the thing, she told my colleague. He knew if he refused hed be admitted and he didnt want to give up the option. So what was I supposed to do?

Fortunately, this story has a positive ending. The daughter was able to persuade her father to go to a therapist. The therapist was experienced and kind and, possibly because he was about the same age, able to connect with a 70-year-old depressed man who was grieving.

But the story is a good illustration of the limitations of the often used Contract for Safety.

Whats Wrong with a Contract for Safety?

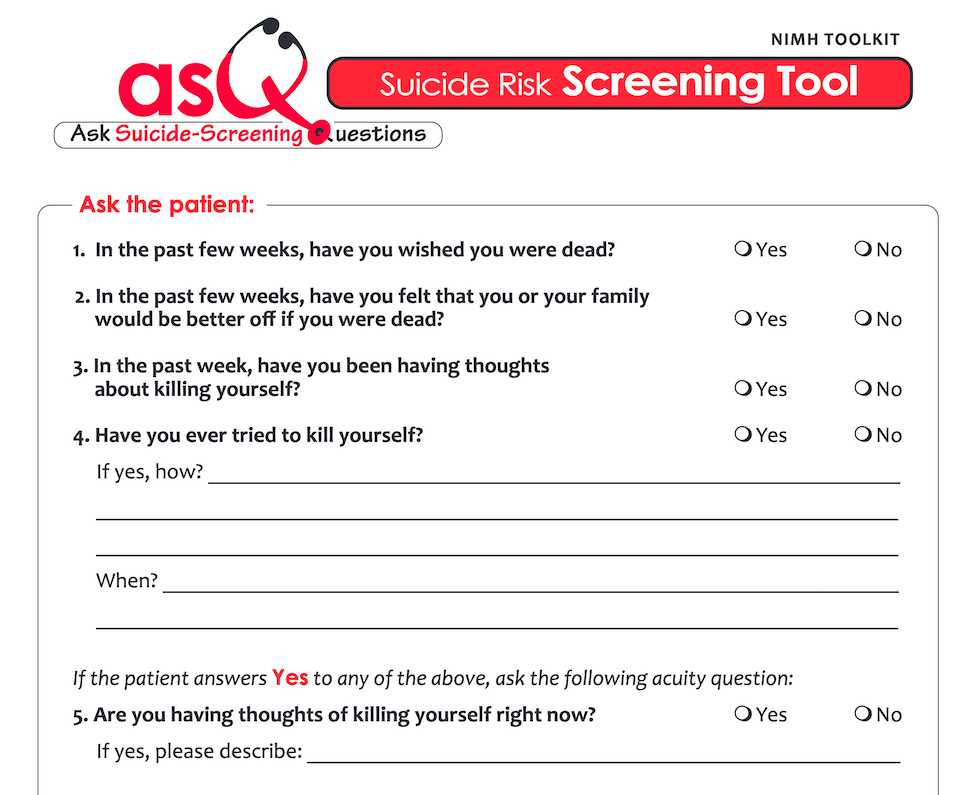

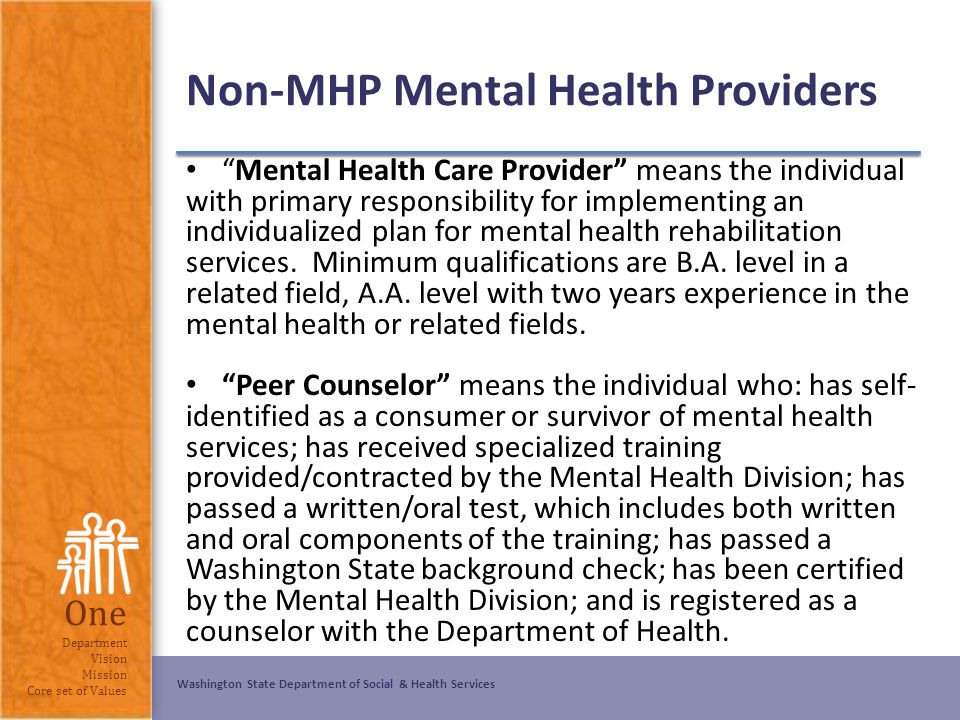

Results of Contracts for Safety (CFS), where a client is asked to agree either verbally or in writing that she will not engage in self harm, were first published by Drye, et.al. in 1973 . Although these original authors only investigated its effectiveness with patients in a long term relationship with their therapist, the use of the tool has since become standard practice for many crisis teams and clinicians, even during an initial interview. But are they effective?

A careful review of the literature by Kelly and Knudson at Idaho State Universitys Institute of Rural Health in 2000 showed that no studies demonstrate that contracts are an effective way to prevent suicide .

A 2001 study by B.L. Drew found that of people who attempted suicide in a psychiatric hospital, 65% had signed a CFS . In still another study, this one a 2000 survey of psychiatrists in Minnesota by Dr. Jerome Kroll, 40% had a patient make a serious or successful suicide attempt after signing a CFS.

Jerome Kroll, 40% had a patient make a serious or successful suicide attempt after signing a CFS.

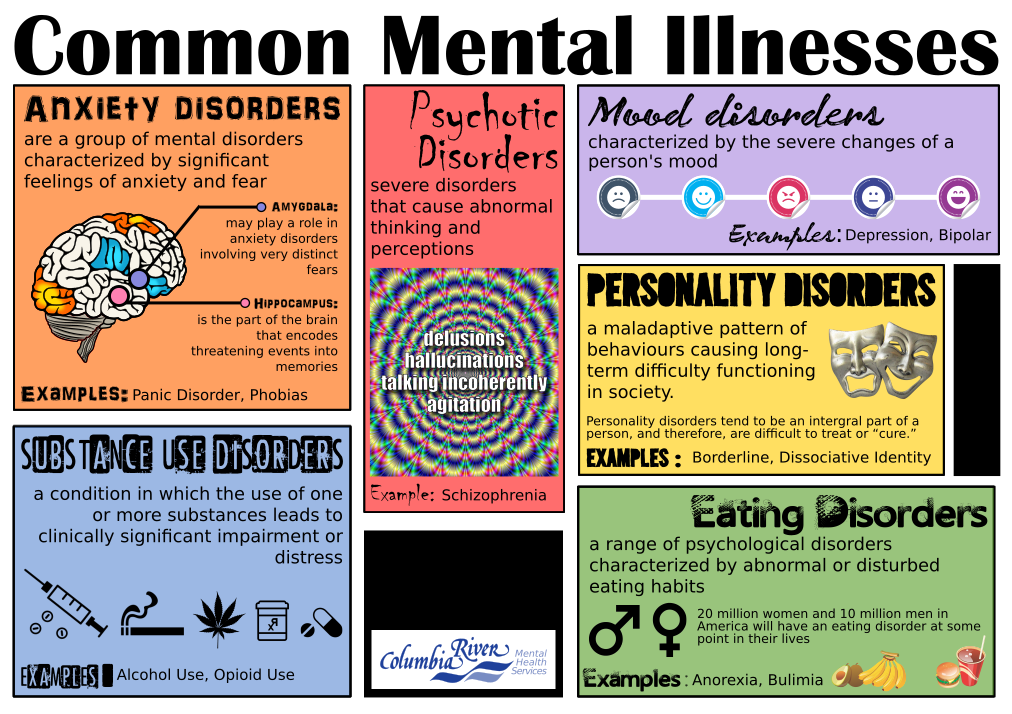

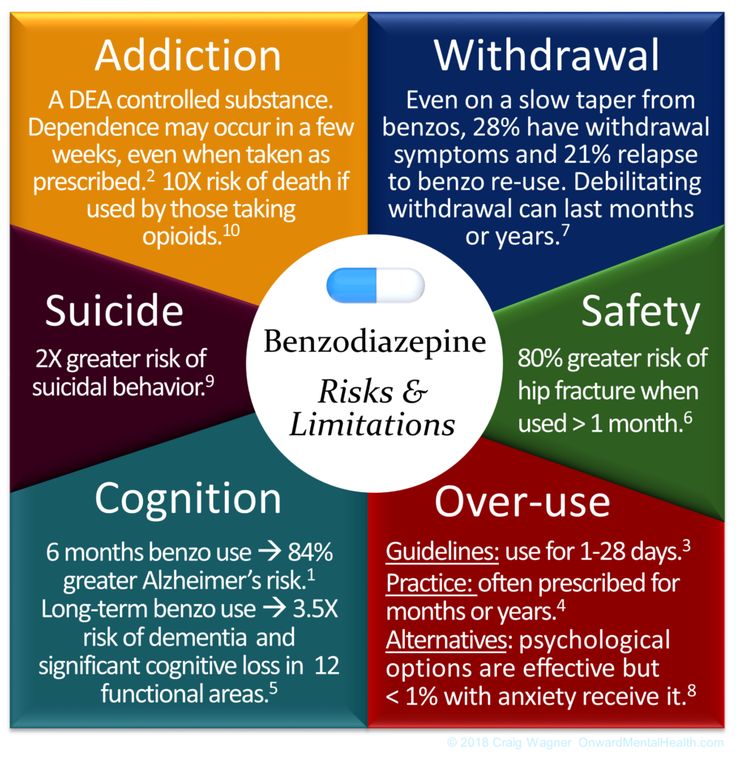

Contracts for Safety have not been found to be useful with suicidal patients who are psychotic, impulsive, depressed or agitated, who have a personality disorder or who are under the influence of alcohol or street drugs the very patients who are the most likely to show up in emergency rooms.

In fact, there is even some evidence that for people diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder, a CFS may make things worse.

There are a number of reasons why clinicians continue to use Contracts for Safety, despite the evidence that when used alone, they may not be helpful and, in some cases, may even be harmful.

First, most clinicians receive limited training in suicidality. The use of the Contract for Safety has become almost folkloric. Confronted with a suicidal client, the clinician may have heard that such a contract is helpful. Doing something, even something that may be ineffective, feels better than doing nothing.

Secondly, some clinicians seem to think that the use and documentation of a CFS protects them from legal liability if the client does commit suicide

Studies have shown, however, that having a CFS does not decrease a clinicians liability. Thirdly, some clinicians think they can relax a bit if they have a contract. They mistakenly believe that having the contract buys them some time to help the client abandon suicide as a solution to his problems.

Finally, a severely mentally ill or intellectually disabled or addicted client may be in no shape to make a contract that represents an informed, responsible decision.

If Not a Contract for Safety, What?

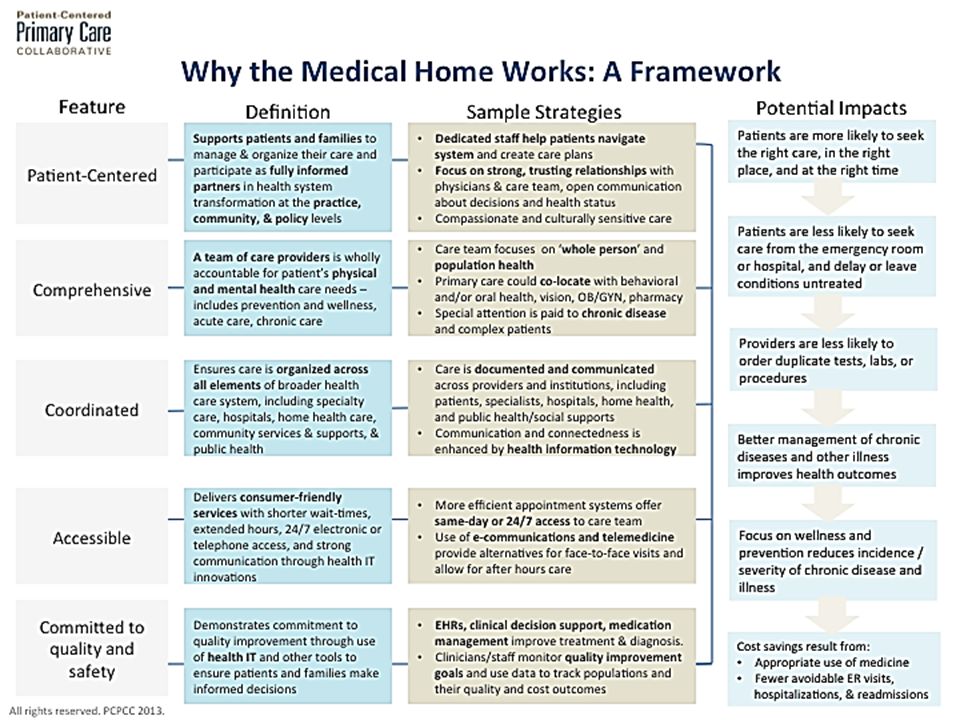

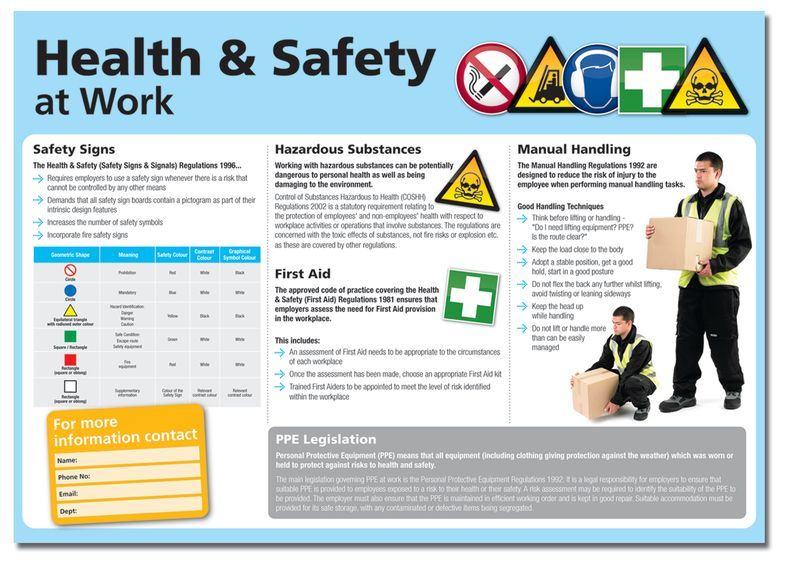

Obtain training: There are other, more effective responses to the threat of suicide than the Contract for Safety. But in order for any of them to be maximally effective, the clinician must develop his or her own expertise. (See related article). Few graduate and professional programs offer adequate training to new clinicians. If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

Develop the therapeutic relationship: Limit use of a Contract for Safety to clients with whom you have a long-term solid relationship: In such cases, the contract can be a useful way to open a conversation about their intentions and feelings.

It can be a relief to a long term client that you are taking her despair seriously and that you care enough to explore whether such an agreement would be helpful. When the client is in crisis, consider increasing the frequency of sessions or other types of contact.

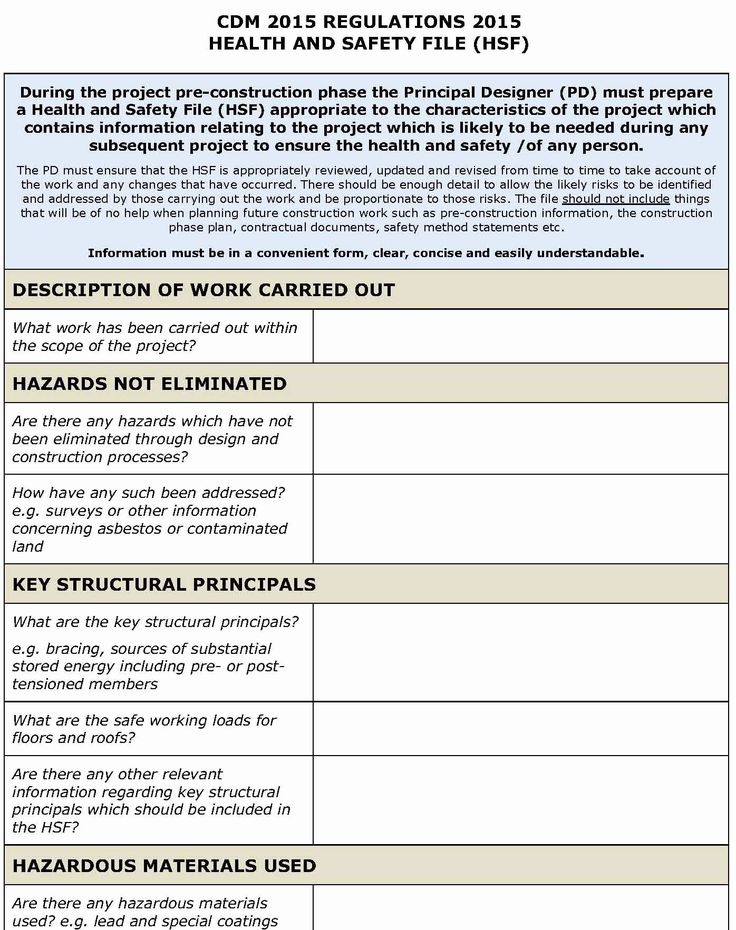

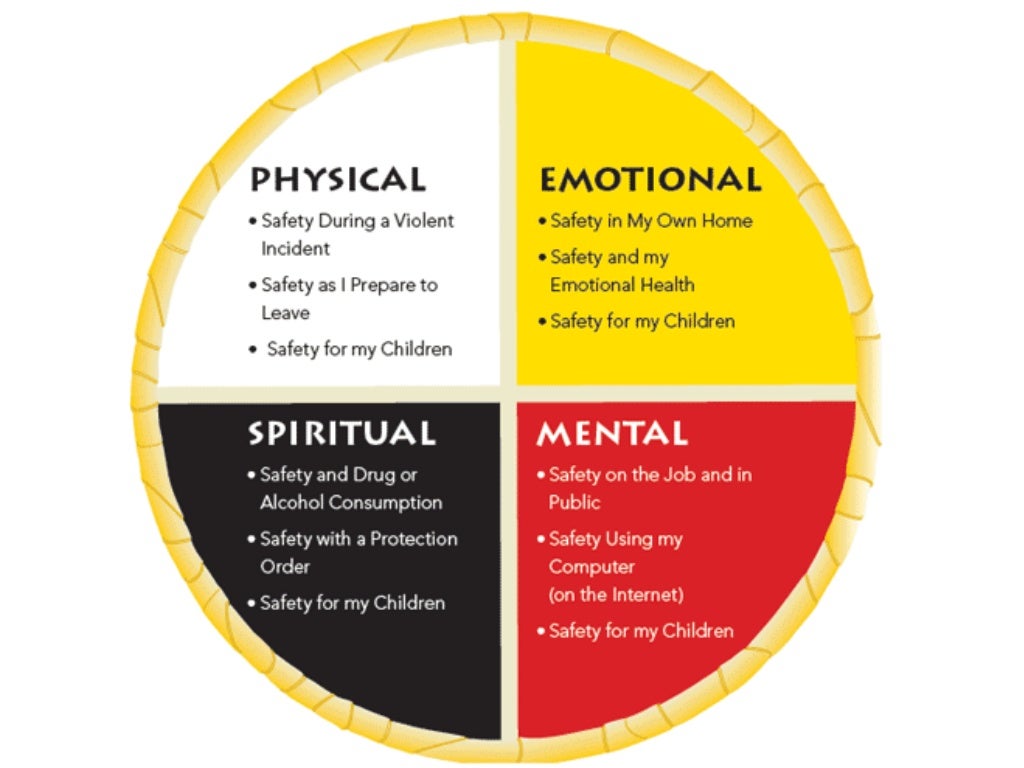

Use the contract only as a part of a full risk assessment: A comprehensive risk assessment includes an evaluation of risk factors, an understanding of what has precipitated suicidal thinking, assessment of the individuals plan and access to means, investigation of any history of past attempts and identification of resiliency factors and potential supports.

Assess regularly: Risk assessment is a dynamic process and should be done regularly with clients who present with or have a history of suicidality or self-harm.

Take time to review risk whenever there is a change in presentation, if symptoms persist or get worse, if medications are changed or if the client talks about terminating.

Periodically utilize a tool like the Beck Depression Scale to check for progress with depressed clients. Regularly do a Mental Status Exam. Be sure to assess the client for delusions, hallucinations, a thought disorder or a decrease in capacity for reality testing.

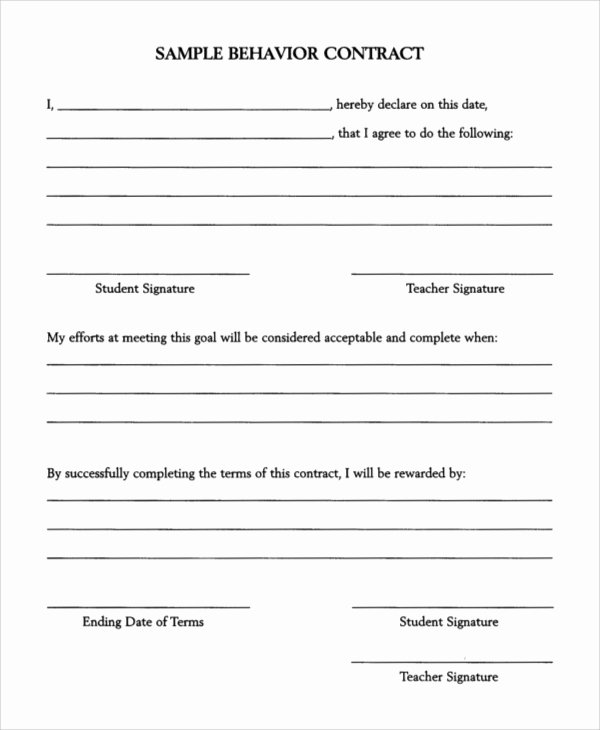

Develop a Safety Plan with your client. A Safety Plan differs from a Contract for Safety in several important ways. Such a plan focuses on what the client will do to keep himself safe rather than what he wont do to harm himself.

- Help the client identify her own triggers and situations that put her at greatest risk.

- Work with the client to list and practice whatever coping skills he has available.

- Determine if the client has access to guns, potentially lethal medications or any other means for hurting herself. Ask/insist that the client give such items to a trusted friend or relative.

- Ask the client to permit you to contact family members or other trusted individuals who can be helpful in getting her through a crisis. If possible, involve those individuals in some of the clients sessions to clarify whether they are willing to accept a supportive role and what they can do that is the most helpful for this individual. For example: Do they just need to talk the person through on the phone or do they need to take the person to the hospital?

- Identify other sources of support such as the local crisis team, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the local NAMI group. Write down the phone numbers and ask the client to keep them with him.

- Collaborate. If a client becomes suicidal, get a release to talk to the prescriber and to collaborate with the local crisis team. With the clients permission, involve the family (see above). Increase your own supervision.

The Contract for Safety has become too much a part of the routine for clinicians when confronted with the suicidal client.

Although it was created as an assessment tool for use with clients who have a relationship with their therapist, it is too often the immediate and only response to suicidality. Clinical decisions regarding risk require a much more thorough and complex assessment of the individual. When there is clinical concern about the clients safety, it is a safety plan, not a contract, that is most likely to result in positive outcomes.

Healthcare form photo available from Shutterstock

Contracting for Safety With Patients: Clinical Practice and Forensic Implications

OtherREGULAR ARTICLE

Keelin A. Garvey, Joseph V. Penn, Angela L. Campbell, Christianne Esposito-Smythers and Anthony Spirito

Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online September 2009, 37 (3) 363-370;

- Article

- Info & Metrics

Abstract

The contract for safety is a procedure used in the management of suicidal patients and has significant patient care, risk management, and medicolegal implications. We conducted a literature review to assess empirical support for this procedure and reviewed legal cases in which this practice was employed, to examine its effect on outcome. Studies obtained from a PubMed search were reviewed and consisted mainly of opinion-based surveys of clinicians and patients and retrospective reviews. Overall, empirically based evidence to support the use of the contract for safety in any population is very limited, particularly in adolescent populations. A legal review revealed that contracting for safety is never enough to protect against legal liability and may lead to adverse consequences for the clinician and the patient. Contracts should be considered for use only in patients who are deemed capable of giving informed consent and, even in these circumstances, should be used with caution. A contract should never replace a thorough assessment of a patient's suicide risk factors. Further empirical research is needed to determine whether contracting for safety merits consideration as a future component of the suicide risk assessment.

We conducted a literature review to assess empirical support for this procedure and reviewed legal cases in which this practice was employed, to examine its effect on outcome. Studies obtained from a PubMed search were reviewed and consisted mainly of opinion-based surveys of clinicians and patients and retrospective reviews. Overall, empirically based evidence to support the use of the contract for safety in any population is very limited, particularly in adolescent populations. A legal review revealed that contracting for safety is never enough to protect against legal liability and may lead to adverse consequences for the clinician and the patient. Contracts should be considered for use only in patients who are deemed capable of giving informed consent and, even in these circumstances, should be used with caution. A contract should never replace a thorough assessment of a patient's suicide risk factors. Further empirical research is needed to determine whether contracting for safety merits consideration as a future component of the suicide risk assessment.

The contract for safety, or no-suicide agreement, was first described in the literature more than 30 years ago.1 It is now used in a variety of settings to assess suicidality and determine level of care. For obvious reasons of ethics, research on the effectiveness of this tool is limited, and data have been largely confined to opinion-based surveys and retrospective reviews. Many experts on the evaluation and management of suicidal patients have warned against the use of this tool as a substitute for a thorough risk assessment, at least in part because obtaining a patient's written or verbal contract provides a false sense of security for many clinicians. The concept of a contract for safety has been taken out of its original context and applied to a large variety of settings and populations without evidence to support its use in these areas.

The purpose of this article is to review the use of no-suicide contracts from both clinical and legal perspectives. A literature review of PubMed was conducted using different terms to describe the same concept, including contract for safety, no-suicide agreement, and no-suicide contract. Additional articles and studies were selected from reference lists of review articles collected from the primary search. Papers were used if they discussed problems and potential concerns related to use of a contract for safety, including primary research and review articles. A LexisNexis search of all state and federal cases was also performed using the search terms contract for safety, no-suicide contract, no-suicide agreement, and stay-alive contract, to review legal outcomes related to the use of this practice.

Additional articles and studies were selected from reference lists of review articles collected from the primary search. Papers were used if they discussed problems and potential concerns related to use of a contract for safety, including primary research and review articles. A LexisNexis search of all state and federal cases was also performed using the search terms contract for safety, no-suicide contract, no-suicide agreement, and stay-alive contract, to review legal outcomes related to the use of this practice.

History of the Contract for Safety

The practice of contracting for safety dates back to an article by Drye et al.1 in 1973, in which the use of the no-suicide contract was studied in the context of an outpatient therapy practice. The practice was originally intended to assist in evaluation and planning, as well as to provide a way to share the burden of assessment and responsibility with the patient. The suicidal patient was asked to make a statement vowing not to kill him- or herself accidentally or on purpose, regardless of the circumstances, and to discuss internal responses to the statement. If any objection or qualification was made, the patient was thought to be at risk for suicide. Thirty-one counselors were surveyed, reporting on 266 seriously suicidal patients, with 20 suicides or serious attempts reported when the counselor's assessment method was not used and 4 when it was used.

If any objection or qualification was made, the patient was thought to be at risk for suicide. Thirty-one counselors were surveyed, reporting on 266 seriously suicidal patients, with 20 suicides or serious attempts reported when the counselor's assessment method was not used and 4 when it was used.

Drye et al.1 received criticism for their study's many shortcomings, yet their work became the foundation of a new concept in suicide management: putting the responsibility on the patient. The no-suicide contract evolved into an instrument that is often interpreted as an actual contract made between patient and clinician, in which the patient makes a commitment not to engage in self-harm. The initial purpose of this model—that is, to assess level of suicide risk as measured by the patient's reaction to the required statements—has been largely overlooked as the act of contracting has become more of a medicolegal procedure.

The initial contract for safety model was designed for use in patients with whom there is a well-established rapport, in the context of outpatient therapy, but soon gained popularity for inpatient and crisis use. Twiname2 became the first to suggest that the contract could be used in patients previously unknown to the clinician, although a continued thorough assessment of risk was emphasized.

Twiname2 became the first to suggest that the contract could be used in patients previously unknown to the clinician, although a continued thorough assessment of risk was emphasized.

Variations on the no-suicide contract now include both written and verbal forms of agreement in both inpatient and outpatient settings, often used on an ongoing basis from the first assessment of a patient in an urgent setting until the time of discharge from an inpatient stay, or at each outpatient visit. Unfortunately, in some instances, contracting for safety is used as a quick screening tool rather than a careful assessment. The patient who is able to contract for safety outside the hospital may be judged safe for outpatient treatment, while the patient who cannot contract for safety outside the hospital but can contract in the hospital may be judged to need inpatient admission but not close observation within the hospital. In this context, the contract for safety is treated as an objective assessment, similar to a laboratory value. The problem arises when clinicians rely too heavily on the patient's statement of intent and do not perform a careful assessment of suicide risk, or overestimate the patient's capacity to self-report.

The problem arises when clinicians rely too heavily on the patient's statement of intent and do not perform a careful assessment of suicide risk, or overestimate the patient's capacity to self-report.

Advantages of the Contract for Safety

Despite a lack of empirical evidence and an abundance of literature warning against its use in an isolated context, many clinicians continue to use the contract for safety. When used cautiously, it can be a way for the clinician to express concern for the suicidal patient. The clinician can use the process of contracting as a way to convey to the patient a common goal, to keep the patient alive.3 If the clinician is able to do so with empathy and concern, a therapeutic alliance can be formed through such a process.3,4 Unfortunately, this process can have the opposite effect if not done effectively, and the therapeutic alliance can suffer if the patient views contracting as merely an administrative task or a way for the clinician to relieve his own anxiety. 3–5

3–5

Contracting for safety may also restore a sense of control in the suicidal patient, who may otherwise feel a lack of control.3 It may serve as a reminder to the patient that he is ultimately responsible for making the decision to attempt suicide, and if the contracting process involves identifying a support system available to the patient if he feels unable to maintain control, including notifying staff in an inpatient setting or contacting a therapist on an outpatient basis, the contract for safety can function as a safety plan.

The initial purpose of the no-suicide contract was to serve as an assessment tool, and its continued use for this purpose can provide valuable information regarding the suicidal patient. Whether a patient is willing to engage in such a contract can help guide the risk assessment, and the patient's attitude toward the agreement can also provide useful information.6 Refusal to contract for safety may provide the most valuable clinical information, eliminating a false sense of security and inciting action to ensure the patient's safety. 4,5,7

4,5,7

Empirical Evidence for Use of the Contract for Safety in Adults

At a time when evidenced-based medicine is becoming the standard of care and psychiatric education is evolving to keep up with this standard, one of the most significant problems regarding the continued use of the contract for safety is the lack of empirical evidence to support its effectiveness.4,8–11 The contract originated from a study1 that received a great deal of criticism for citing inadequate information and failing to perform adequate statistical analysis3 and has been called informal.10 The randomized controlled trial, the gold standard of evidence-based medicine, is not an option for many reasons. Blinding is not possible because a contract involves conscious awareness on the part of both parties involved. There is also an obvious dilemma in the ethics involved in comparing the suicide rate of a group of patients with a suicide agreement with that of a group without such an agreement. 12 Because of these limitations, research has fallen into three categories: frequency surveys, retrospective research on the impact of no-suicide contracts on suicidal behavior, and opinions of users.4,13

12 Because of these limitations, research has fallen into three categories: frequency surveys, retrospective research on the impact of no-suicide contracts on suicidal behavior, and opinions of users.4,13

A consistent finding among frequency surveys is that some form of no-suicide contract is used by the majority of inpatient and outpatient clinicians in the management of suicidal patients.10 Kroll14 examined the use of no-suicide contracts by psychiatrists in Minnesota, and found that of the 52 percent of psychiatrists who responded, 57 percent used no-suicide contracts. Drew15 found that no-suicide contracts were used by 79 percent of the psychiatric inpatient facilities surveyed in Ohio in 1999, and that they were typically negotiated after expressions of suicidal ideation, acts of self-harm, or suicide attempts. In 1998, Miller et al.16 surveyed 112 faculty members at Harvard Medical School and discovered that 61 percent of psychiatrists and 83 percent of psychologists frequently used no-suicide contracts.

Another area of research has focused on surveying the opinions of experts and patients regarding the usefulness of contracting for safety. Davidson and colleagues12 surveyed a group of psychologists regarding their views of no-suicide agreements and found that overall, such agreements were viewed as helpful with moderately suicidal patients and less helpful with slightly or severely suicidal patients. The results also indicated that the psychologists believed that contracting was appropriate with adults and adolescents, but not with children. Davis and colleagues17 took a different approach, surveying 135 patients admitted to an inpatient psychiatric hospital for suicidal ideation regarding their views on the use of no-suicide contracts. Most patients rated the agreements positively, independent of age, sex, social desirability, presence or absence of Axis II disorder, or degree of suicidal risk at admission. A history of suicidal behavior, including number of attempts, did affect the patients’ ratings of the helpfulness of these contracts, however, with multiple attempters viewing them as less helpful than those patients with no attempts. The authors hypothesized that given the severity of psychopathology found in multiple attempters, their views toward any intervention may be more negative than those of less severely ill patients. In addition, prior experience with contracting for safety and subsequent suicidal behaviors might have contributed to the doubt that these patients felt toward the usefulness of this intervention. This finding also suggests the necessity of having a strong therapeutic alliance when using the contract for safety to judge clinical risk. Patients who self-injure or attempt suicide after contracting for safety may feel less of an alliance with their treating clinicians.

The authors hypothesized that given the severity of psychopathology found in multiple attempters, their views toward any intervention may be more negative than those of less severely ill patients. In addition, prior experience with contracting for safety and subsequent suicidal behaviors might have contributed to the doubt that these patients felt toward the usefulness of this intervention. This finding also suggests the necessity of having a strong therapeutic alliance when using the contract for safety to judge clinical risk. Patients who self-injure or attempt suicide after contracting for safety may feel less of an alliance with their treating clinicians.

Buelow and Range13 surveyed college students in 2001 regarding attitudes toward certain interventions, asking the students to rate three different contracts that varied in level of detail. The students rated the most complex contract the most highly. A large majority (82%) of respondents recommended using a no-suicide contract in suicidal patients, but rated the no-suicide contract overall as the lowest among factors most likely to prevent suicide. Among respondents, 40 percent reported having been suicidal in the past, and there was no significant difference between their attitudes toward no-suicide agreements and those of respondents who had never been suicidal. The average length of time elapsed since suicidal ideation was 3.5 years, and it was hypothesized that the passage of time may have affected their opinions.13

Among respondents, 40 percent reported having been suicidal in the past, and there was no significant difference between their attitudes toward no-suicide agreements and those of respondents who had never been suicidal. The average length of time elapsed since suicidal ideation was 3.5 years, and it was hypothesized that the passage of time may have affected their opinions.13

Chart review studies have also been conducted to assess the effectiveness of the contract for safety. Busch et al.18 conducted a retrospective chart review of 14 inpatients who committed suicide or made serious attempts and found that 7 of them had made informal no-harm agreements with staff. They conducted a similar study 10 years later,19 revealing that of 76 patients who committed suicide while in the hospital, 28 percent had made some form of contract against self-harm with staff. Drew20 performed a retrospective chart review of 650 medical records of inpatients from adult psychiatric units at two general hospitals in northeastern Ohio and found that 65 percent of patients who harmed themselves had contracted for safety. The results based on two separate analyses suggested that individuals with contracts were five to seven times more likely to engage in self-harm than patients without contracts. Drew concluded that this was not a causal relationship, but more likely was attributable to the higher likelihood that high-risk patients had contracts. Use of the contract for safety was also not shown to decrease the likelihood of self-harm in this study.

The results based on two separate analyses suggested that individuals with contracts were five to seven times more likely to engage in self-harm than patients without contracts. Drew concluded that this was not a causal relationship, but more likely was attributable to the higher likelihood that high-risk patients had contracts. Use of the contract for safety was also not shown to decrease the likelihood of self-harm in this study.

Mishara and Daigle21 evaluated the effects of different telephone interventions with callers to two suicide prevention centers, finding that some form of contract was made with 68 percent of callers and that 54 percent of the contracts were upheld. The contracts included having a follow-up call with the center, however, and were considered upheld only if the caller followed through with this part of the contract. The percentage of callers who upheld the safety part of the contract was not known.

Use of the Contract for Safety in Adolescents

As the contract for safety has become more widely used in a variety of adult settings, many clinicians have also adapted it for use with adolescents and even children, often by including family members in the process. Data specific to the practice with adolescents are even more scarce and will be reviewed briefly. This topic remains controversial, and an exhaustive discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Data specific to the practice with adolescents are even more scarce and will be reviewed briefly. This topic remains controversial, and an exhaustive discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

Brent22 performed a review of the evaluation and treatment of adolescents who attempt suicide and identified the contracting process as a way of committing the patient and family to action, emphasizing coping strategies and crisis management as well as the importance of 24-hour clinical support. Brent's discussion of the no-suicide contract occurs in the context of an extensive review of suicide risk assessment and focuses on its utility in assessment and treatment rather than as a medicolegal procedure.

The most recent practice parameter of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry23 for the assessment and treatment of suicidal children and adolescents supports the use of the no-suicide contract as an assessment tool and suggests that it may increase the patient's and family's commitment to treatment, although the practice parameter warns against the use of the contract in isolation and the potential for underestimating suicide risk that can result from such a contract.

Research on the effectiveness of contracting for safety with adolescents in reducing suicide risk is minimal. The early literature suggests that using a no-suicide contract with adolescents at low or moderate risk of suicide is an effective strategy, but empirical evidence is not cited to support the recommendation.24 Jones25 conducted research on the use of contracting to target behaviors in children and adolescents in an inpatient setting, initially polling previously suicidal patients on an inpatient unit whose privileges depended on their compliance with a written no-suicide agreement. The patients reported that the agreement helped them change their suicidal behaviors, but they were only moderately interested in continuing the agreement after discharge.25

Jones et al.26 later conducted a retrospective review of incident sheets logging all serious behaviors observed by staff members at an inpatient child and adolescent psychiatric unit in Utah, to assess the effectiveness of a contracting system used in determining precaution status. This included an examination of incidents of suicidal behavior defined as suicidal talk, behavior, or self-mutilation. Records indicated that 1.94 percent of patients admitted during the 2.5 years before a contracting system was implemented were involved in an incident of suicidal behavior, compared with .17 percent of patients admitted over 3.5 years after the system was implemented. The contracting system employed was structured: adolescent patients were permitted to write their own contracts, and younger patients earned reductions in precaution status through specific behavioral demonstrations structured by staff. A decision tree was used to guide the contracting process, and continued monitoring was never abandoned. The contracting system was judged to be effective based on overall reduction in all types of incidents, but the relatively small number of instances of suicidal behavior (seven before implementation of contracting, one after implementation) limits the usefulness of these data in determining the effectiveness of contracting on suicidal behavior.

This included an examination of incidents of suicidal behavior defined as suicidal talk, behavior, or self-mutilation. Records indicated that 1.94 percent of patients admitted during the 2.5 years before a contracting system was implemented were involved in an incident of suicidal behavior, compared with .17 percent of patients admitted over 3.5 years after the system was implemented. The contracting system employed was structured: adolescent patients were permitted to write their own contracts, and younger patients earned reductions in precaution status through specific behavioral demonstrations structured by staff. A decision tree was used to guide the contracting process, and continued monitoring was never abandoned. The contracting system was judged to be effective based on overall reduction in all types of incidents, but the relatively small number of instances of suicidal behavior (seven before implementation of contracting, one after implementation) limits the usefulness of these data in determining the effectiveness of contracting on suicidal behavior.

Boehm and Campbell27 described calls made to an adolescent peer-support telephone service over a five-and-a-half-year period, and found that most callers agreed to no-suicide contracts with peer answerers when calling about suicidality. Only eight of 223 calls required tracing during the period that traced calls were documented. Calls were traced if callers were thought to be at risk and would not agree to a no-suicide contract. Notably, this study highlighted the adolescents’ willingness to agree to no-suicide contracts, but did not indicate whether the contracts were upheld.

Further research has included studies examining the attitudes of high school students toward the no-suicide agreement. A group of high school students5 was asked their opinions about the use of a no-suicide contract in the context of a hypothetical situation. The students in this study generally favored the use of such an agreement over therapy alone, but their endorsement was not overwhelming. The study was limited by a relatively low response rate, the hypothetical nature of the situation, and the use of a general population of students whose opinions may differ from those of adolescents who have been suicidal.

The study was limited by a relatively low response rate, the hypothetical nature of the situation, and the use of a general population of students whose opinions may differ from those of adolescents who have been suicidal.

Adolescence has long been considered a time of increased impulsivity and risk-taking behavior, and suicidal behavior during this stage often reflects this behavior. It is common for adolescent suicide attempts to be impulsive rather than premeditated, and suicidal tendencies are often fleeting and precipitated by an acute event.28 A recent area of research, the investigation of possible biological components to increased suicide risk, has found common ground between suicide risk, aggression, and impulsivity. Attempts to measure impulsivity empirically during adolescence have been complicated by the pervasiveness of impulsivity in the general population of adolescents, as well as methodological problems involved in collecting data through self-report scales. 29 Given the inability to measure impulsivity and assess its impact on suicidal behavior accurately, the clinician should approach the practice of contracting for safety with extreme caution when treating adolescents, as it may be difficult to identify adolescents capable of upholding such contracts.

29 Given the inability to measure impulsivity and assess its impact on suicidal behavior accurately, the clinician should approach the practice of contracting for safety with extreme caution when treating adolescents, as it may be difficult to identify adolescents capable of upholding such contracts.

Informed Consent

Questions have been raised regarding the capacity of suicidal patients to consent to a no-suicide contract. The presence of such hindrances as intoxication, active psychosis, severe depression or intense hopelessness, and rapid shifts in alliance due to personality disorder have been named as potential challenges, and have been thought to interfere with a patient's ability to consent to such an agreement.6 Obtaining a contract with such individuals would not be valid from a legal standpoint if considered in terms of the criteria described by Simon7 in 1999, which state that a contract must involve parties who are legally competent.

Though adults have a legal presumption of competence,7 children and adolescents add another dimension to the question of informed consent and the contract for safety. The rights of minors to make their own health care-related decisions vary by individual state, but many states do not allow them to consent to inpatient admission or psychopharmacological treatment without a guardian's permission. A discussion of the statutes by state is beyond the scope of this article, but special consideration should always be given to the adolescent's capacity to give informed consent. A thorough assessment of capacity is often required before the initiation of any treatment without guardian consent, and capacity to consent to a no-suicide contract should be evaluated before including this practice in the risk assessment.

Medicolegal Considerations

Documentation of a patient's ability to contract for safety was once thought to reduce the clinician's legal liability,12 and many practicing clinicians include careful records of a patient's commitment to a contract in their documentation. A review of federal and state cases in which the act of contracting for safety is documented reveals that legal outcome is more often largely independent of the presence or absence of this procedure.

A review of federal and state cases in which the act of contracting for safety is documented reveals that legal outcome is more often largely independent of the presence or absence of this procedure.

In Stepakoff v. Kantar7,30 in 1985, the Massachusetts Supreme Court ruled in favor of a psychiatrist whose patient committed suicide, judging that he had met the standard of care. The psychiatrist's treatment of the patient had included a pact requiring the patient to contact him if he felt suicidal, which he did on several occasions, resulting in frequent contact and ongoing assessment of his suicide risk. The court ruled that the pact fell within the standard of care, but did not comment specifically about the use of such pacts. Thus, it appears that frequent contact and ongoing assessment on the part of the psychiatrist led to a favorable legal outcome rather than the use of a pact. In this case, the pact served as part of a larger plan for maintaining the safety of the patient, and thorough risk assessments were performed regularly.

Similarly, in Cox v. Willis-Knighton Medical Center,31 a Louisiana court found in favor of a nonpsychiatric physician when a patient committed suicide while on a pass from a chemical dependency unit. Although the patient's treatment plan had included a stay-alive contract, the court did not comment on the presence of such a contract in determining whether the standard of care was met.

In the case of Durney v. Terk 32 in 2007, the New York Supreme Court essentially dismissed the relevance of the contracting process when it overturned a ruling in favor of a patient who committed suicide one week after being discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit. The patient's wife had testified that the patient “hesitated” when asked to contract for safety during the family meeting on the day of his discharge, which the jury found to be a departure from the standard of care despite finding the actual discharge plan to be within acceptable standards. The decision was reversed on appeal, with the Supreme Court noting that a medical provider “could not be held liable for a mere error in professional judgment,” and that “for liability to ensue, plaintiff must show that the provider's treatment decision was something less than a professional medical determination.” While the jury found significance in this one aspect of the patient's care, the Supreme Court rendered the decision to base the patient's discharge on a multifactorial assessment to be within the standard of care, de-emphasizing the contract for safety as a primary assessment tool or requirement for discharge.

The decision was reversed on appeal, with the Supreme Court noting that a medical provider “could not be held liable for a mere error in professional judgment,” and that “for liability to ensue, plaintiff must show that the provider's treatment decision was something less than a professional medical determination.” While the jury found significance in this one aspect of the patient's care, the Supreme Court rendered the decision to base the patient's discharge on a multifactorial assessment to be within the standard of care, de-emphasizing the contract for safety as a primary assessment tool or requirement for discharge.

Several suicide cases in which physicians were found liable contained documentation of a patient's contract for safety. In Reid v. Altieri 33 in Florida in 2007, the jury found both the physician and the hospital negligent when a patient was refused admission shortly after being discharged from an inpatient psychiatric unit under a contract for safety. The patient's family had agreed to bring the patient back to the hospital if his suicidal thoughts returned. When they did so, the patient was denied admission because of poor communication between the physician and hospital. The testimony of the plaintiff's expert implied that the patient's contract indicated heightened responsibility for the physician and hospital. Although it is not explicitly discussed in the case, it is implied that part of the defendants’ negligence lay in their failure to uphold the contract.

The patient's family had agreed to bring the patient back to the hospital if his suicidal thoughts returned. When they did so, the patient was denied admission because of poor communication between the physician and hospital. The testimony of the plaintiff's expert implied that the patient's contract indicated heightened responsibility for the physician and hospital. Although it is not explicitly discussed in the case, it is implied that part of the defendants’ negligence lay in their failure to uphold the contract.

The appellate court of Illinois overturned the decision of a jury that ruled in favor of the defendant doctor in the case of a suicide by overdose of antidepressants in Hobart v. Shin.34 The plaintiff had alleged that the doctor, a family physician, was negligent in prescribing excessive amounts of doxepin to the patient, for which the clinician's defense was one of contributory negligence. The question of contributory negligence requires first, determination of negligence on the part of both the plaintiff and the defendant, and second, comparison of the plaintiff's negligence with that of the defendant. The focus of this defense is whether the plaintiff took appropriate precautions to protect his or her own interest.35 The basis of this doctor's defense was that the patient willfully took her own life, and her psychiatrist testified on the defendant's behalf that the patient had entered into a no-suicide contract with her before her suicide, and could have contacted her at any time.

The focus of this defense is whether the plaintiff took appropriate precautions to protect his or her own interest.35 The basis of this doctor's defense was that the patient willfully took her own life, and her psychiatrist testified on the defendant's behalf that the patient had entered into a no-suicide contract with her before her suicide, and could have contacted her at any time.

The jury's original decision was overturned on the grounds that contributory negligence is not an appropriate defense in any action against a doctor in the suicide of a patient with mental illness. In making this argument, the plaintiff cited Peoples Bank v. Damera,36 in which the Illinois court ruled on appeal that a suicide case differs from a typical medical malpractice case in that “here the patient does not share the goal of his physician of getting better,” and stated that comparative fault was not likely ever to be appropriate in a case of suicide. The decision was eventually reversed again by the Illinois Supreme Court, who ruled that this defense was appropriate unless the patient was considered so mentally ill as to be incapable of contributory negligence.

Reviewing the legal history makes it clear that the presence of a contract for safety does not decrease liability and may actually enhance it, as in the case of Reid v. Altieri.33 Another potential downside of this practice is its possible effect on reimbursement when used in an inpatient setting. Jane Doe v. Travelers Insurance Company37 involved a patient with suicidal ideation who was admitted to an inpatient unit and was deemed a serious suicide risk by the admitting clinician, but was denied reimbursement for hospitalization costs. The insurance reviewers cited the patient's willingness to contract for safety with the hospital and resultant admission with less frequent monitoring as grounds for rejection. Although the court found for the patient and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed this finding, this case still highlights that a contract for safety may be subject to interpretation and can be used in an unfavorable way by third-party payers.

Discussion

Evidence to support the continued use of the contract for safety is extremely limited for any population. There appears to be more literature discussing the paucity of evidence than there is actual research on the practice. Why then is documenting that a patient contracted for safety still such a common practice? The legal history reveals that the presence of a contract usually carries little significance in determining negligence, and may actually amplify the court's perception of the clinician's level of responsibility to the patient.

From a legal perspective, that contributory negligence may not be considered an appropriate defense in the case of a patient with known mental illness who commits suicide, depending on the jurisdiction, appears to abolish any potential use of the contract for safety as a legal safeguard. Although the initial goal of Drye et al.1 of calling on the patient to take some of the responsibility for his or her own survival may have been useful therapeutically, the courts have told us that the suicidal patient, by the nature of his or her illness, may not be relied upon to make healthful decisions.

Some clinicians may use the contract for safety as a shorthand way of documenting their assessment of a patient's suicide risk.14 While they may be conducting more thorough risk assessments than this documentation suggests, to abbreviate the process in this way implies too much dependence on the act of contracting, leaving out all the other essential components of the risk assessment that they may have considered in the process of formulating a treatment plan.

The contract for safety is an aspect of suicide risk management that has been given too much weight over the past several decades. What appears to have been created primarily as an assessment tool has become a sort of checkbox, detracting from the clinician's own judgment and formulation of risk. It has been taken out of its original context and is now used in virtually any setting, with any type of patient population despite the lack of clinical evidence to prove it is useful and an abundance of literature warning that it is not. If clinicians are going to continue to use the contract for safety as a way of managing rather than assessing risk, further research is needed to indicate whether suicide risk can actually be reduced through use of such a contract.

If clinicians are going to continue to use the contract for safety as a way of managing rather than assessing risk, further research is needed to indicate whether suicide risk can actually be reduced through use of such a contract.

Suicide risk assessment and management are complicated processes unlike any other in medicine. There are no laboratory values or imaging studies to support the decision-making process in the event of a bad outcome. Decisions should be guided by a thorough assessment of risk. A complete suicide risk assessment is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to the Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors38 and the Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Suicidal Behavior.23

Footnotes

-

Presented in poster format at the 38th Annual Meeting of The American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, Miami, Florida, October 18, 2007

References

- ↵

Drye RC, Goulding RL, Goulding ME: No-suicide decisions: patient monitoring of suicidal risk.

Am J Psychiatry 130:171–4, 1973

Am J Psychiatry 130:171–4, 1973 - ↵

Twiname BG: No-suicide contracts for nurses. J Psychiatr Nurs Ment Health Serv 19:11–2, 1981

- ↵

Lee JB, Bartlett ML: Suicide prevention: critical elements for managing suicidal clients and counselor liability without the use of a no-suicide contract. Death Stud 29:847–65, 2005

- ↵

Range LM, Campbell C, Kovac SH, et al: No-suicide contracts: an overview and recommendations. Death Stud 26:51–74, 2002

- ↵

Myers SS, Range LM: No-suicide agreements: high school students’ perspectives. Death Stud 26:851–7, 2002

- ↵

Weiss A: The no-suicide contract: possibilities and pitfalls. Am J Psychother 55:414–9, 2001

- ↵

Simon RI: The suicide prevention contract: clinical, legal, and risk management issues.

J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 27:445–50, 1999

J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 27:445–50, 1999 - ↵

Farrow TL, O'Brien AJ: ‘No-suicide contracts’ and informed consent: an analysis of ethical issues. Nurs Ethics 10:199–207, 2003

-

Potter ML, Dawson AM: From safety contract to safety agreement. J Psychosoc Nurs 39:38–45, 1997

- ↵

Rudd MD, Mandrusiak M, Joiner TE: The case against no-suicide contracts: the commitment to treatment statement as a practice alternative. J Clin Psychol 62:243–51, 2006

- ↵

Kelly KT, Knudson MP: Are no-suicide contracts effective in preventing suicide in suicidal patients seen by primary care physicians? Arch Fam Med 9:1119–21, 2000

- ↵

Davidson MW, Wagner WG, Range LM: Clinicians’ attitudes toward no-suicide agreements. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25:410–4, 1995

- ↵

Buelow G, Range LM: No-suicide contracts among college students.

Death Stud 25:583–92, 2001

Death Stud 25:583–92, 2001 - ↵

Kroll J: Use of no-suicide contracts by psychiatrists in Minnesota. Am J Psychiatry 157:1684–6, 2000

- ↵

Drew BL: No-suicide contracts to prevent suicidal behavior in inpatient psychiatric settings. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 5:23–8, 1999

- ↵

Miller MC, Jacobs DG, Gutheil TG: Talisman or taboo: the controversy of the suicide-prevention contract. Harv Rev Psychiatry 6:78–87, 1998

- ↵

Davis SE, Williams IS, Hays LW: Psychiatric inpatients’ perceptions of written no-suicide agreements: an exploratory study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 32:51–66, 2002

- ↵

Busch KA, Clark DC, Fawcett J: Clinical features of inpatient suicide. Psychiatr Ann 23:256–62, 1993

- ↵

Busch KA, Fawcett J, Jacobs DG: Clinical correlates of inpatient suicide.

J Clin Psychiat 64:14–9, 2003

J Clin Psychiat 64:14–9, 2003 - ↵

Drew BL: Self-harm behavior and no-suicide contracting in psychiatric inpatient settings. Arch Psychiat Nurs 15;99–106, 2001

- ↵

Mishara BL, Daigle MS: Effects of different telephone intervention styles with suicidal callers at two suicide prevention centers: an empirical investigation. Am J Community Psychol 25:861–85, 1997

- ↵

Brent DA: Practitioner review: the aftercare of adolescents with deliberate self-harm. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:277–86, 1997

- ↵

Practice Parameter for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents With Suicidal Behavior. Available at www.aacap.org. Accessed December 1, 2007

- ↵

Valente SM: Adolescent suicide: assessment and intervention. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2:34–9, 1989

- ↵

Jones RN: Unique interventions for child inpatient psychiatry.

J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 28:29–31, 1990

J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 28:29–31, 1990 - ↵

Jones RN, O'Brien PO, McMahon WM: Contracting to lower precaution status for child psychiatric inpatients. J Psychosoc Nurs 31:6–10, 1993

- ↵

Boehm KE, Campbell NB: Suicide: a review of calls to an adolescent peer listening phone service. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 26:61–6, 1995

- ↵

Kennedy SP, Baraff LJ, Suddath RL, et al: Emergency department management of suicidal adolescents. Ann Emerg Med 43:452–9, 2004

- ↵

Gorlyn M: Impulsivity in the prediction of suicidal behavior in adolescent populations. Int J Adolesc Med Health 17:205–9, 2005

- ↵

Stepakoff v. Kantar, 473 N.E.2d 1131, 1133–1137 (Mass. 1985)

- ↵

Cox v. Willis-Knighton Med.

Ctr., 680 So.2d 1309, 1318–1320 (La. Ct. App. 1996)

Ctr., 680 So.2d 1309, 1318–1320 (La. Ct. App. 1996) - ↵

Durney v. Terk, 840 N.Y.S.2d 30, 31–33 (N.Y. App. Div. 2007)

- ↵

Reid v. Altieri, 950 So.2d 518, 520–524 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 2007)

- ↵

Hobart v. Shin, 686 N.E.2d 617, 618–623 (Ill. App. Ct. 1997)

- ↵

57 Am. Jur. 2d Negligence § 806 (2007)

- ↵

Peoples Bank of Bloomington v. Damera, 581 N.E.2d 426, 429 (Ill. App. Ct. 1991)

- ↵

Doe v. Travelers Ins. Co., 167 F.3d 53, 55–61 (1st Cir. 1999)

- ↵

Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients With Suicidal Behaviors. Available at: http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/SuicidalBehavior_05-15-06.pdf. Accessed November 16, 2007

View Abstract

PreviousNext

Back to top

Article 13.

Observance of medical secrecy \ ConsultantPlus

Observance of medical secrecy \ ConsultantPlus Article 13. Observance of medical secrecy

secret.

2. It is not allowed to disclose information constituting a medical secret, including after the death of a person, by persons to whom they became known during training, performance of labor, official, official and other duties, except for the cases established by parts 3 and 4 of this article .

3. Disclosure of information constituting a medical secret to other citizens, including officials, for the purpose of medical examination and treatment of a patient, conducting scientific research, publishing them in scientific publications, using them in the educational process and for other purposes is allowed with written consent citizen or his legal representative. Consent to the disclosure of information constituting a medical secret may also be expressed in an informed voluntary consent to medical intervention.

(Part 3 as amended by Federal Law No. 315-FZ of July 2, 2021)

(see the text in the previous edition)

3. 1. After the death of a citizen, it is allowed to disclose information constituting a medical secret to a spouse, close relatives (children, parents, adopted children, adoptive parents, siblings, grandchildren, grandparents) or other persons indicated by the citizen or his legal representative in written consent to the disclosure of information constituting a medical secret, or informed voluntary consent to medical intervention, at their request, if the citizen or his legal representative has not prohibited the disclosure of information constituting a medical secret.

1. After the death of a citizen, it is allowed to disclose information constituting a medical secret to a spouse, close relatives (children, parents, adopted children, adoptive parents, siblings, grandchildren, grandparents) or other persons indicated by the citizen or his legal representative in written consent to the disclosure of information constituting a medical secret, or informed voluntary consent to medical intervention, at their request, if the citizen or his legal representative has not prohibited the disclosure of information constituting a medical secret.

(Part 3.1 was introduced by Federal Law No. 315-FZ of July 2, 2021)

who, as a result of his condition, is unable to express his will, subject to the provisions of Clause 1 of Part 9 of Article 20 of this Federal Law;

2) in the event of a threat of the spread of infectious diseases, mass poisoning and injury;

the behavior of a conditionally convicted person, a convicted person in respect of whom the serving of a sentence has been suspended, and a person released on parole, as well as in connection with the execution by the convicted person of the obligation to undergo treatment for drug addiction and medical and (or) social rehabilitation;

(as amended by Federal Laws No. 205-FZ of 23.07.2013, No. 93-FZ of 01.04.2020)

205-FZ of 23.07.2013, No. 93-FZ of 01.04.2020)

(see the text in the previous edition)

fulfillment by persons recognized as addicted to drug addiction or consuming narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances without a doctor's prescription or new potentially dangerous psychoactive substances, assigned to them, when imposing an administrative penalty by a court, the obligation to undergo drug addiction treatment, diagnostics, preventive measures and (or) medical rehabilitation;

(Clause 3.1 was introduced by Federal Law No. 230-FZ of July 13, 2015)

Part 2 of Article 54 of this Federal Law, to inform one of his parents or other legal representative;

5) for the purpose of informing the internal affairs authorities:

a) about the admission of a patient in respect of whom there are sufficient grounds to believe that harm to his health was caused as a result of unlawful actions;

b) admission of a patient who, due to health, age or other reasons, is unable to provide personal information;

c) the death of an unidentified patient;

(Clause 5 as amended by Federal Law No. 438-FZ of December 22, 2020)

438-FZ of December 22, 2020)

(see the text in the previous edition)

- medical (medical-flight) commissions of federal executive bodies and federal state bodies in which the federal law provides for military service and equivalent service;

(as amended by the Federal Law of 04.06.2014 N 145-FZ)

(see the text in the previous edition)

stay in an organization engaged in educational activities, and in accordance with Part 6 of Article 34.1 of the Federal Law of December 4, 2007 N 329-FZ "On Physical Culture and Sports in the Russian Federation" of an accident with a person undergoing sports training and not a member of labor relations with a physical culture and sports organization that does not provide sports training and is a customer of sports training services, while such a person undergoes sports training in an organization that provides sports training, including during his participation in sports competitions provided for by the implemented sports training programs;

(as amended by Federal Laws No. 317-FZ of November 25, 2013, No. 78-FZ of April 6, 2015)

317-FZ of November 25, 2013, No. 78-FZ of April 6, 2015)

(see the text in the previous edition)

in medical information systems, in order to provide medical care, taking into account the requirements of the legislation of the Russian Federation on personal data;

9) in order to carry out accounting and control in the system of compulsory social insurance;

10) for the purpose of monitoring the quality and safety of medical activities in accordance with this Federal Law;

11) is no longer valid. - Federal Law of November 25, 2013 N 317-FZ.

(see text in previous edition)

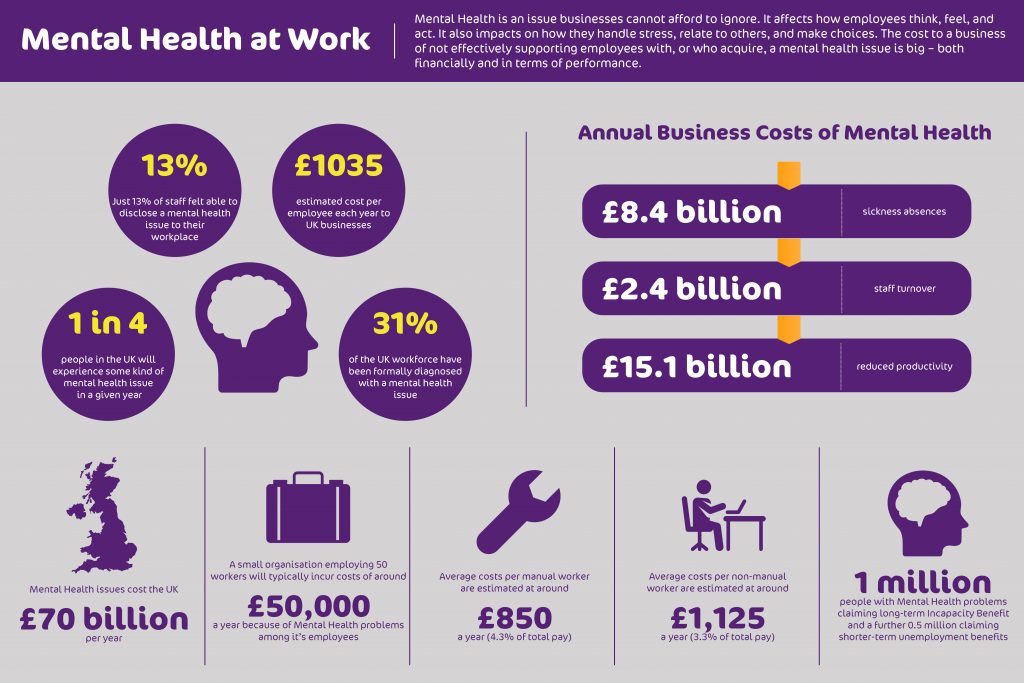

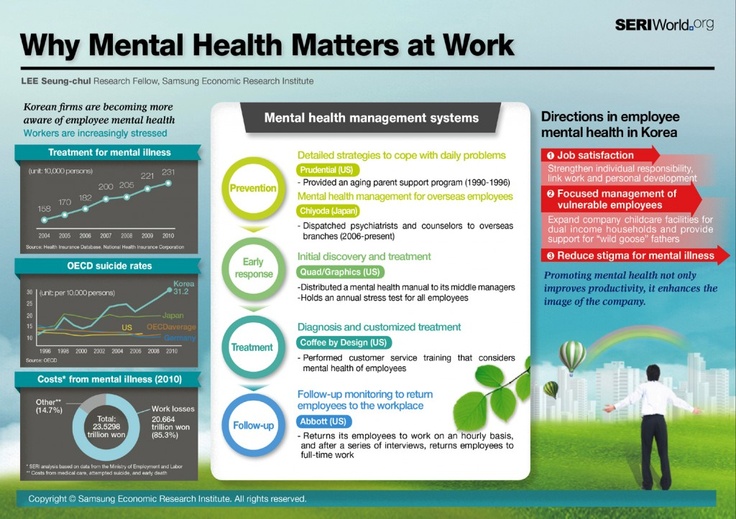

Mental Health Day - Udmurt Psychiatry

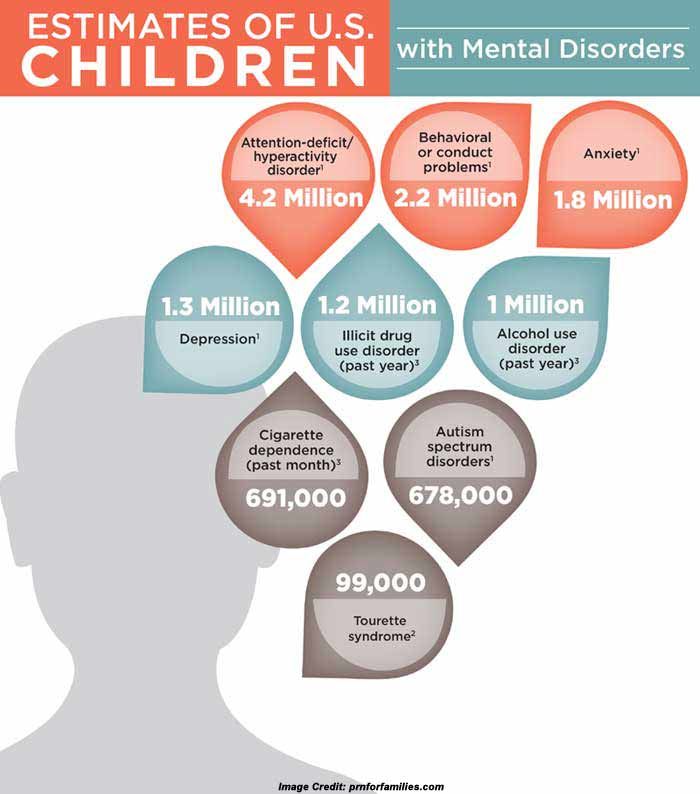

Mental Health Day first appeared in 1992 and has become an annual event with the support of WHO and the World Mental Health Federation. In recent years, this day has had a specific theme: depression, the problem of mental disorders among young people and the older generation, and suicides. In 2020, WHO is calling for the mobilization of resources for mental health. Almost 1 billion people in the world suffer from mental disorders, 3 million people die every year as a result of alcohol abuse, and every 40 seconds one person commits suicide. Currently, another negative factor for the mental health of the population has become the COVID-19 pandemic.that disrupted the normal lives of billions of people around the world.

Almost 1 billion people in the world suffer from mental disorders, 3 million people die every year as a result of alcohol abuse, and every 40 seconds one person commits suicide. Currently, another negative factor for the mental health of the population has become the COVID-19 pandemic.that disrupted the normal lives of billions of people around the world.

The impact of COVID-19 on mental health deserves to be discussed on the eve of Mental Health Day. The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced restrictions on communication between people, social isolation, disrupted the plans of millions of people, caused interruptions in the provision of medical care, including psychiatric care, and disrupted the usual work of doctors and nurses. This is primarily due to such reasons as an increase in the incidence and risk of infection in medical organizations. Psychiatric hospitals differ significantly in structure and equipment from other medical institutions, and patients are treated for a long time due to the peculiarities of the course of mental disorders. Now we can confidently say that the pandemic has affected us all. Regardless of whether we had this infection or not, this infection definitely had an impact on our mental state.

Now we can confidently say that the pandemic has affected us all. Regardless of whether we had this infection or not, this infection definitely had an impact on our mental state.

Naturally, in conditions of uncertainty, fear of getting infected and dying, multiplied by the quarantine regime, job loss, economic downturn, psychological problems come to the fore. Unfortunately, we could not find reliable literary sources on the prevalence and manifestations of mental disorders during the medieval and more ancient epidemics of plague, cholera, and even relatively close in time pandemics of influenza (Spanish flu), Asian and Hong Kong flu in the middle of the 20th century, we could not find. During the period of the death of thousands and tens of thousands of people, the need to save lives, the study of mental disorders did not greatly excite researchers.

But already in February 2020, at the very beginning of a new pandemic, Chinese psychiatrists published the first works on mental health problems, in which they indicated that up to 54% of the general population sample reported a negative impact of the epidemic on psychological well-being, while 16 . 5% developed symptoms of depression, 28.8% experienced moderate to severe anxiety symptoms.

At present, it is conditionally possible to distinguish several groups among the population in need of priority psychological and psychiatric assistance:

First, there is a healthy population that consumes an excessive amount of negative information, is afraid of the future, panic-stricken and does not tolerate new stressors. In this case, you should listen to the recommendations and advice of federal and local health authorities, use only reputable news sources, reduce the amount of time spent watching, reading or listening to news that causes stress or upset. The elderly are especially in need of attention and assistance in this case, due to a combination of several adverse risk factors, including a high likelihood of a complicated course of coronavirus infection, social isolation, increased suicidal risk, and low awareness of using the help offered via the Internet or via mobile communications.

Secondly, these are those with mild COVID-19 who are in quarantine, or those who are severely ill, hospitalized or in need of hospitalization. Persons belonging to this group should remember that qualified medical care will be provided without fail, and the main thing is to strictly follow the recommendations received. If you need to receive up-to-date information support, you can contact the call center of the Ministry of Health of Udmurtia for accompanying patients with COVID-19by phone 8-800-100-24-47. The call center employs and provides assistance to specialists with higher medical and psychological education. Call center specialists not only receive calls, but also support feedback with patients, work with risk groups, monitor the well-being and dynamics of the patient's condition.

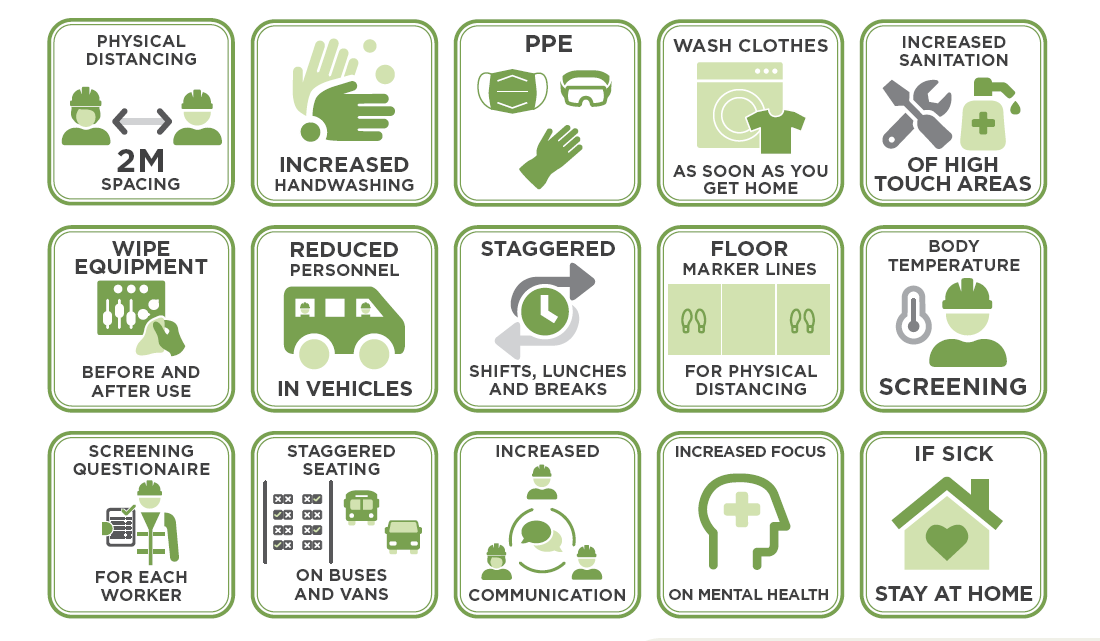

Thirdly, these are medical personnel, both directly providing assistance to patients with COVID-19, and those who provide assistance to other categories of patients. Medical workers have always been the first to suffer from chronic stress in the workplace and, as a result, professional burnout. The pandemic is an additional trigger for burnout among healthcare workers. Burnout is a syndrome understood as the result of chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully dealt with, with emotional and energy exhaustion, feelings of work-related negativism, and reduced professional performance. In a pandemic, additional stress factors join all of the above: high

workload, lack of time, work in new roles and conditions, imbalance between the number of staff and patients, frequent need to inform patients and their families of unpleasant information, high mortality rate.

All this creates the conditions for the occurrence of distress (stress that has a negative effect on the body, a disorganizing effect on activity and behavior), increases anxiety, fear of infecting oneself and loved ones, a feeling of helplessness and internal devastation, reduces concentration, challenges a sense of honesty and professionalism . Health workers should not forget about rest and respite during work or between shifts, do not forget about food and exercise, maintain contact with family, friends, and influential colleagues.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, mental health professionals have become more likely to be contacted by people with adjustment disorder — a state of subjective distress with difficulties in domestic, professional and social functioning that occurs during the period of adaptation to a significant change in life or a stressful event. The second category of patients are people with anxiety disorders: anxiety, fear, panic attacks, insomnia, fixation on disturbing news. Many repeated complaints of a physical nature that resemble a somatic disease that are not confirmed by objective clinical studies are somatoform disorders.

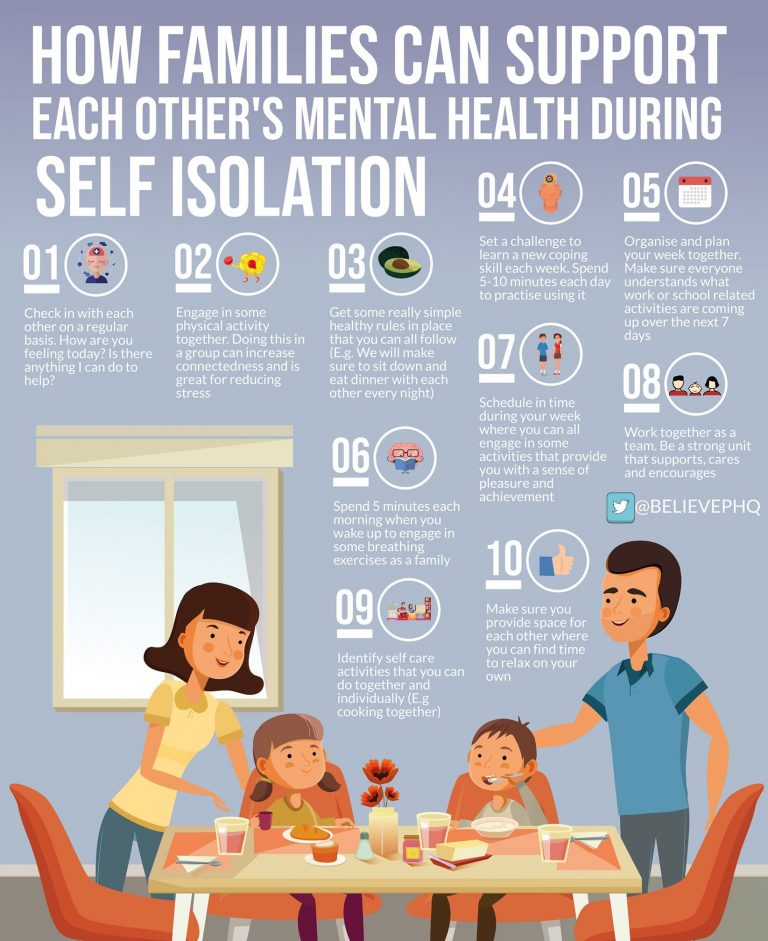

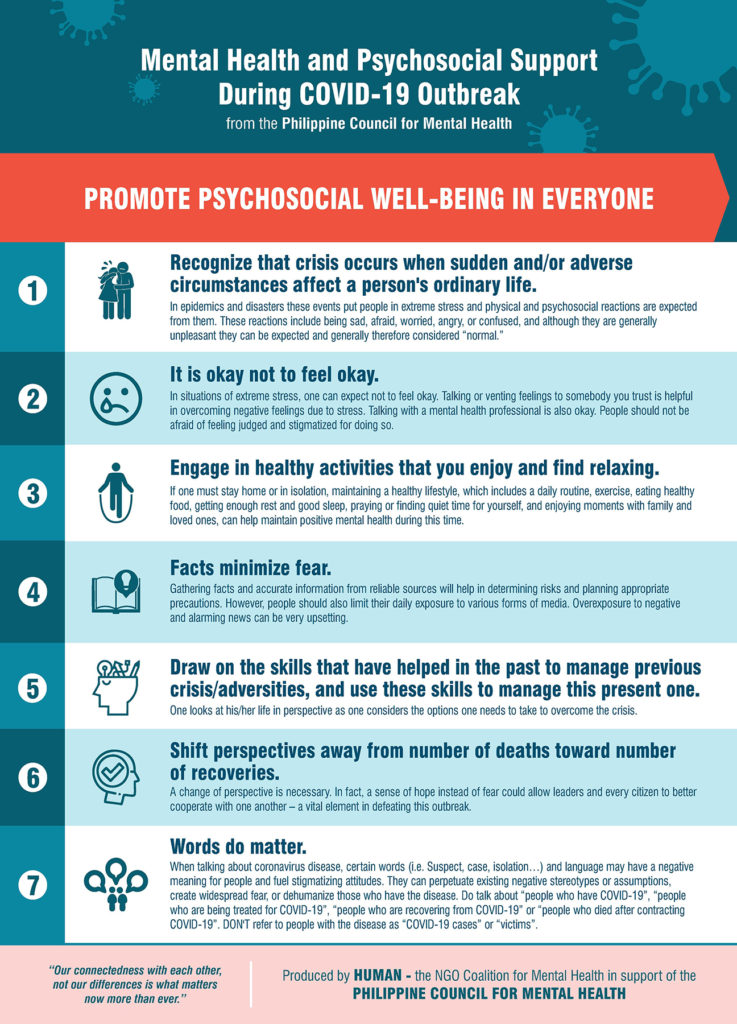

Here are some tips that will also help maintain mental health and significantly reduce stress levels:

1. Watch your daily routine: get up and go to bed at the same time; maintain personal hygiene; stick to a healthy diet and a regular eating pattern; Set aside time for work and time for rest.

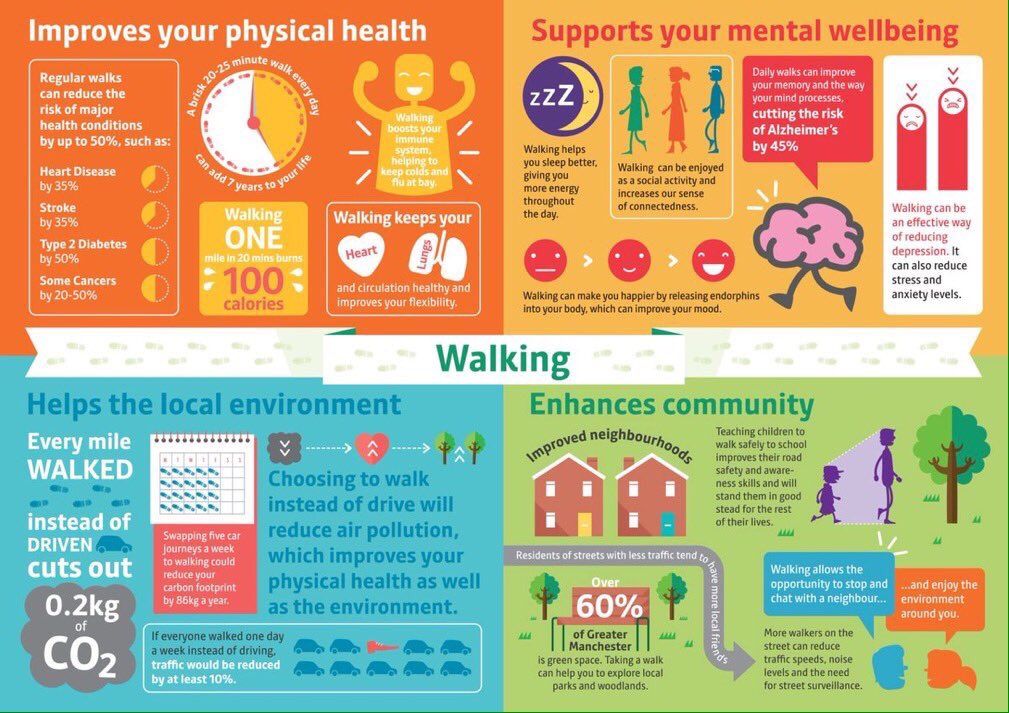

2. Continue your usual physical activity. If you are just starting to play sports, pay attention to techniques that help relieve tension (yoga, tai chi, stretching).

3. Keep up your passions and hobbies. Read more books, watch movies with positive content, listen to music that brings you peace.

4. Spend less time reading the news.

5. Maintain social contacts. If your movement is restricted, maintain regular contact with family and friends by phone and online. Connect more with people you trust.

6. Limit or completely eliminate alcohol. Avoid alcohol as a means of combating fear, anxiety, and boredom. Remember! Alcohol abuse is associated with an increased risk of infectious diseases and a poor prognosis of treatment.

7. If you constantly experience tension, fear, irritation, do relaxation exercises (breathing exercises, meditation, memory exercises, listening to music).

8. Have a plan of action in case you need help related to physical or mental health, psychosocial needs. Find all the necessary contacts, notify relatives and friends about it.