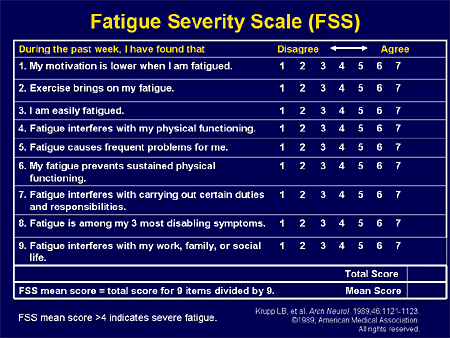

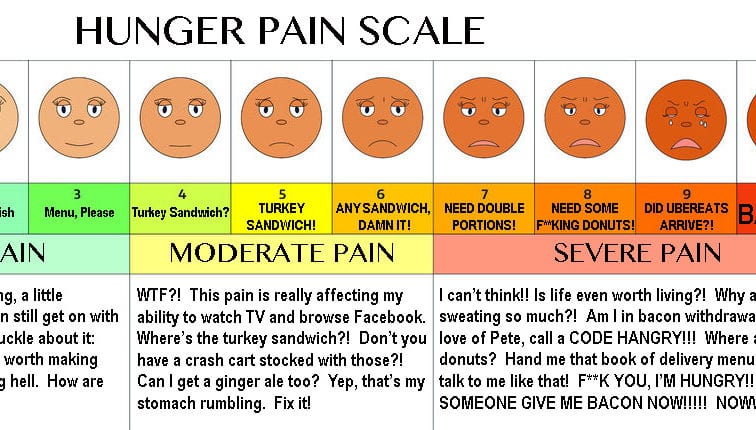

Bulimia severity scale

Bulimia Nervosa: Signs, Causes, and Treatment

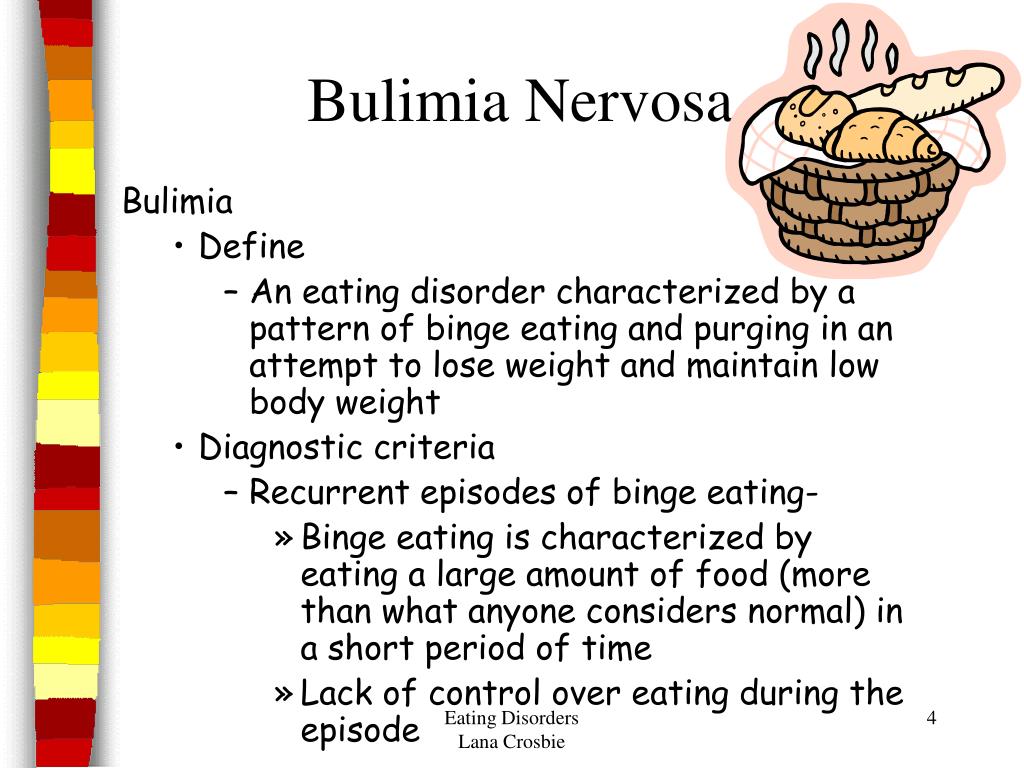

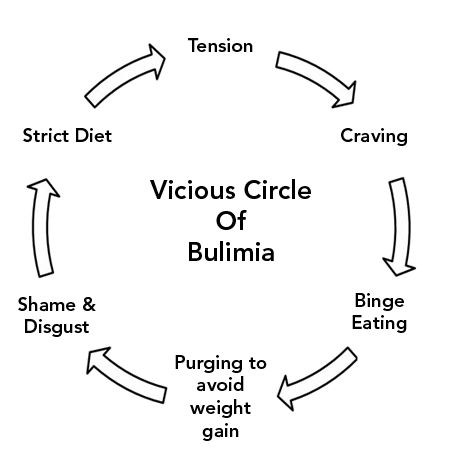

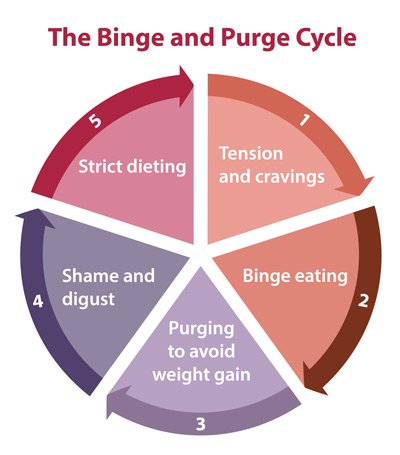

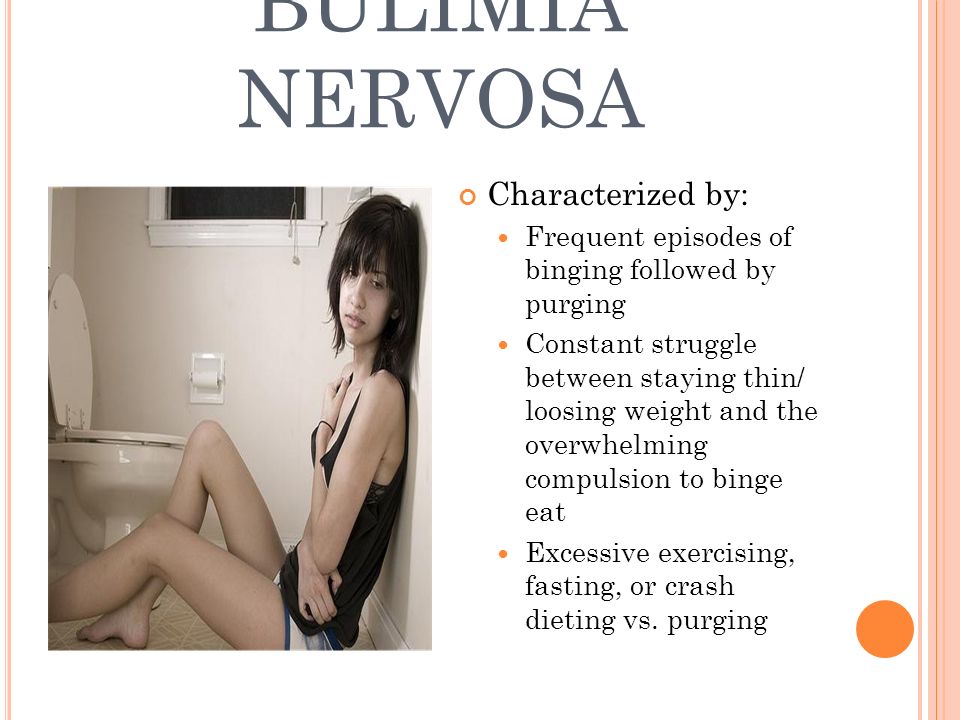

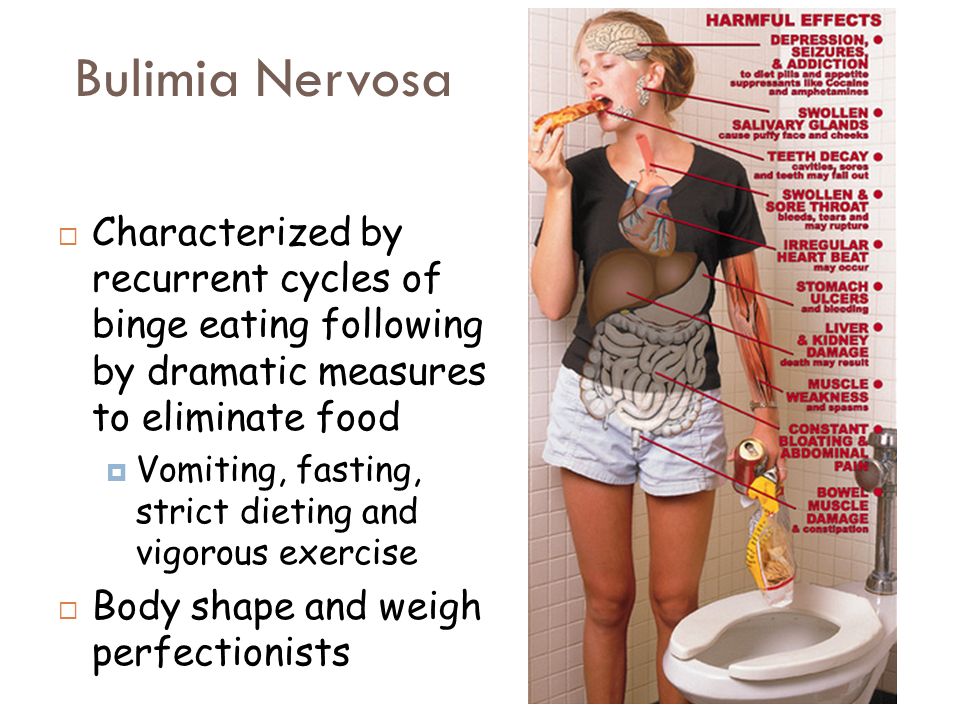

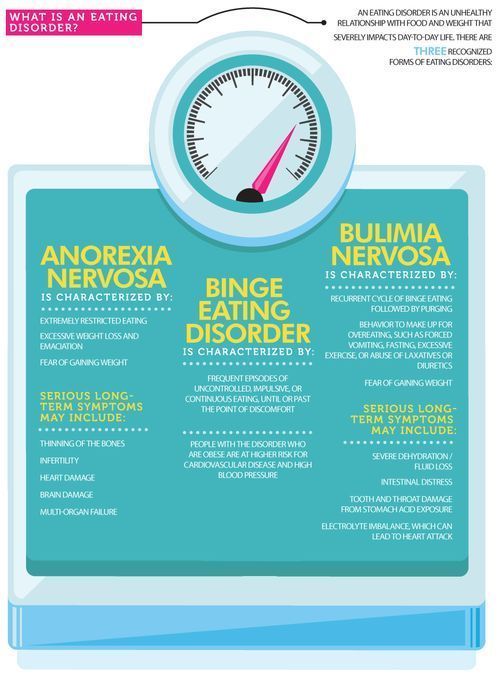

Bulimia nervosa, also known as bulimia, is an eating disorder. It’s generally characterized by eating large amounts of food in a short period of time, followed by purging.

Purging can occur through forced vomiting, excessive exercise, or by taking laxatives or diuretics.

Bulimia is a serious condition that can be life threatening.

People living with bulimia may purge or display purge behaviors, as well as follow a binge-and-purge cycle. Purge behaviors can also include other strict methods to maintain weight like fasting, exercise, or extreme dieting.

Bulimia nervosa may also cause an obsession with achieving an unrealistic body size or shape. A person living with this eating disorder might be obsessed with their weight and can often be self-critical.

Read on to learn more about bulimia, as well as the ways you may help yourself or a loved one with this eating disorder.

The symptoms of bulimia include eating large amounts of food at once and purging, along with a lack of control over these behaviors. A person living with bulimia may also experience feelings of self-disgust after eating.

While the precise list of symptoms may vary between individuals, bulimia may include the following symptoms:

- fear of gaining weight

- making comments about being “fat”

- a preoccupation with weight and body

- a strongly negative self-image

- binge eating, usually within a 2-hour period

- self-induced vomiting

- misuse of laxatives or diuretics

- use of supplements or herbs for weight loss

- excessive and compulsive exercise

- stained teeth (from stomach acid)

- acid reflux

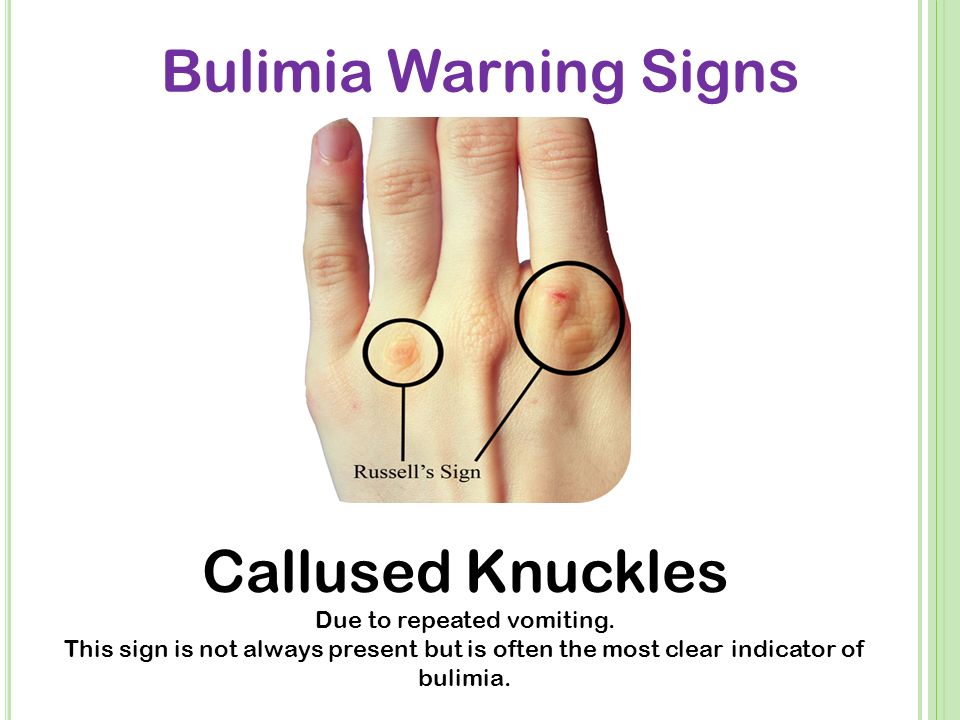

- calluses on the back of your hands

- going to the bathroom immediately after meals

- not eating in front of others

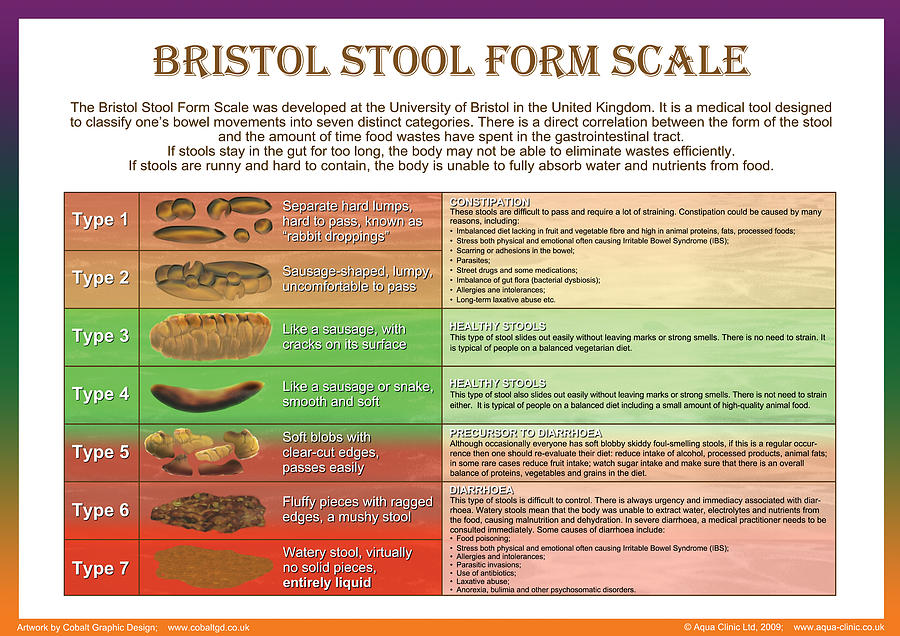

- constipation

- withdrawal from typical social activities

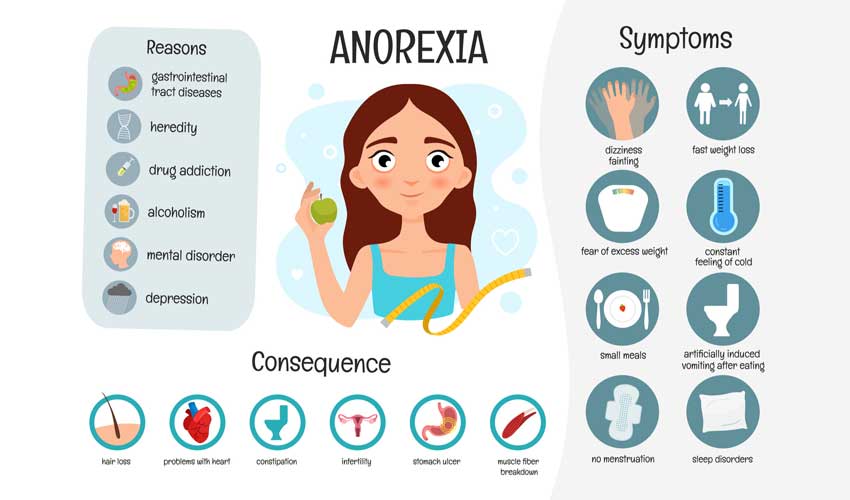

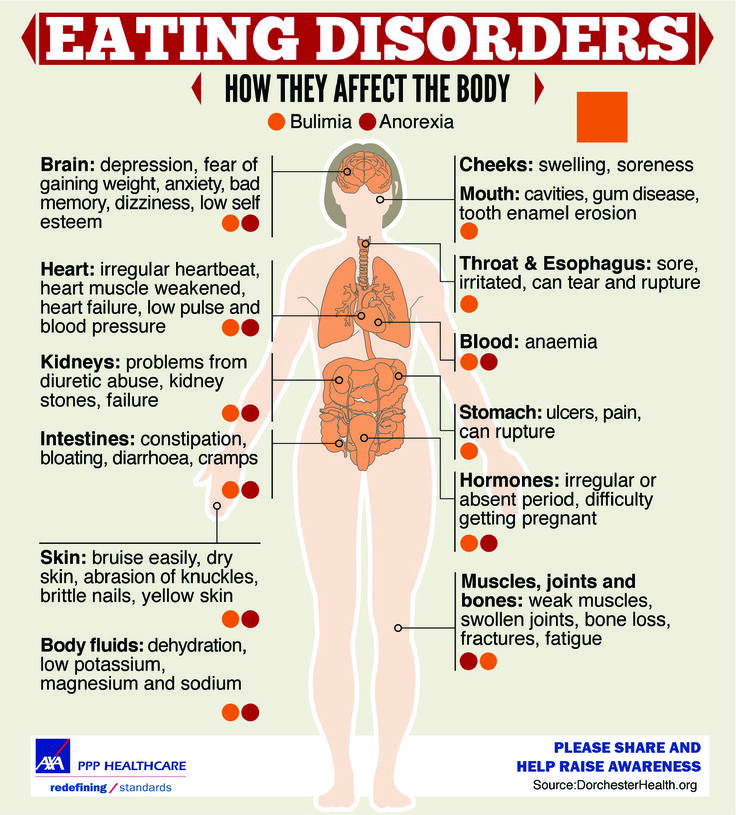

Complications from bulimia can include:

- kidney failure

- heart problems

- gum disease

- tooth decay

- digestive issues or constipation

- ulcers and stomach damage

- dehydration

- nutrient deficiencies

- electrolyte or chemical imbalances

- absence of a menstrual period

- anxiety

- depression

- drug or alcohol misuse

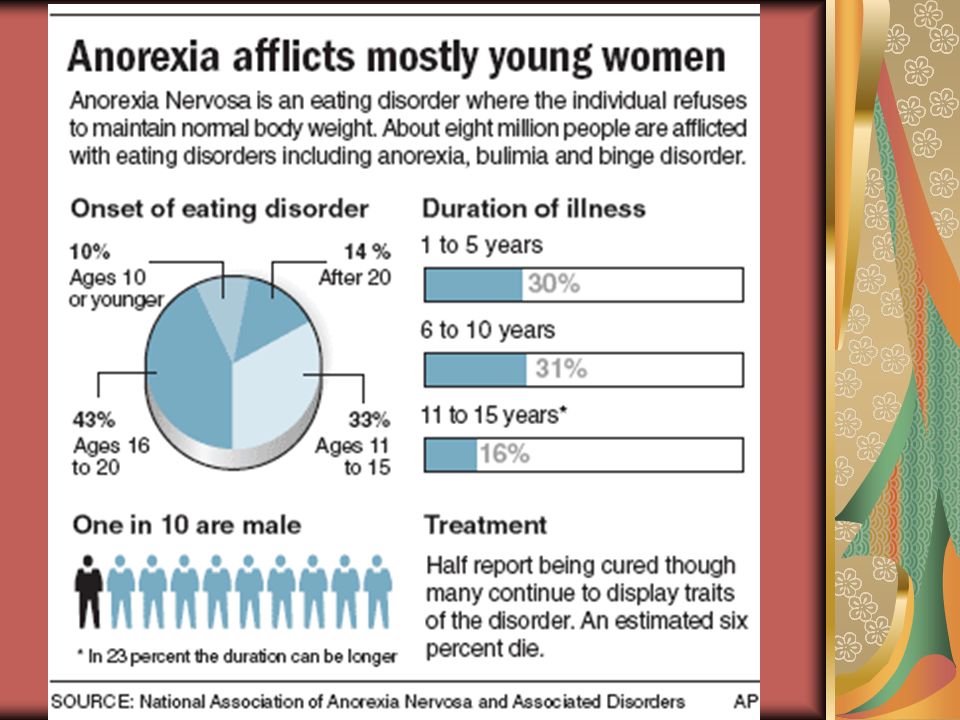

Bulimia can affect anyone at any age or body weight.

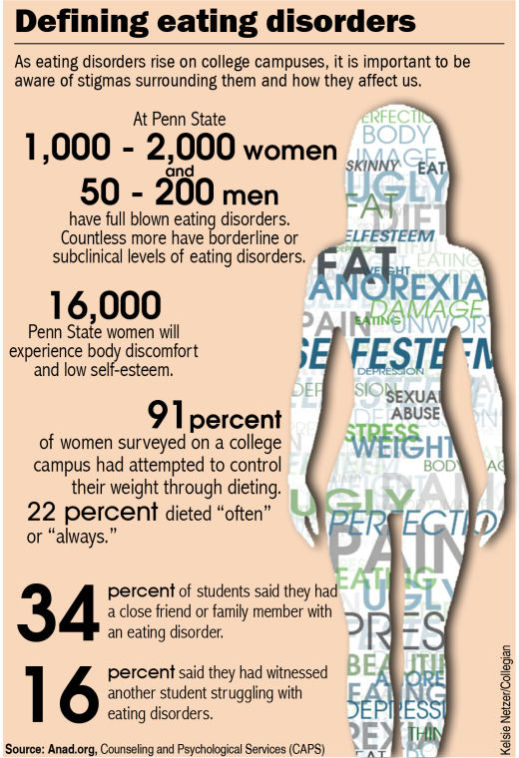

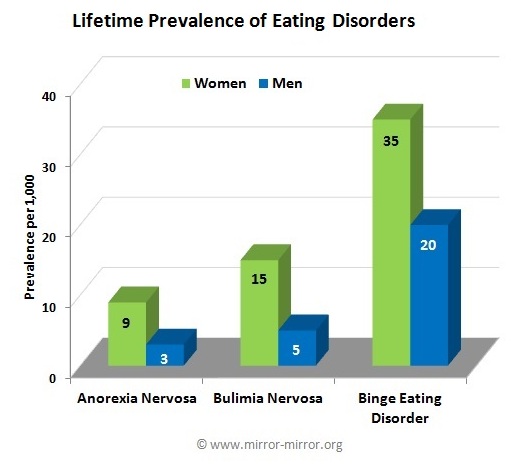

Research indicates that roughly 1.5 percent of women and 0.5 percent of men in the United States will experience bulimia at some point during their life. It’s more common in women, and the median age of onset is estimated to be around 12 years old.

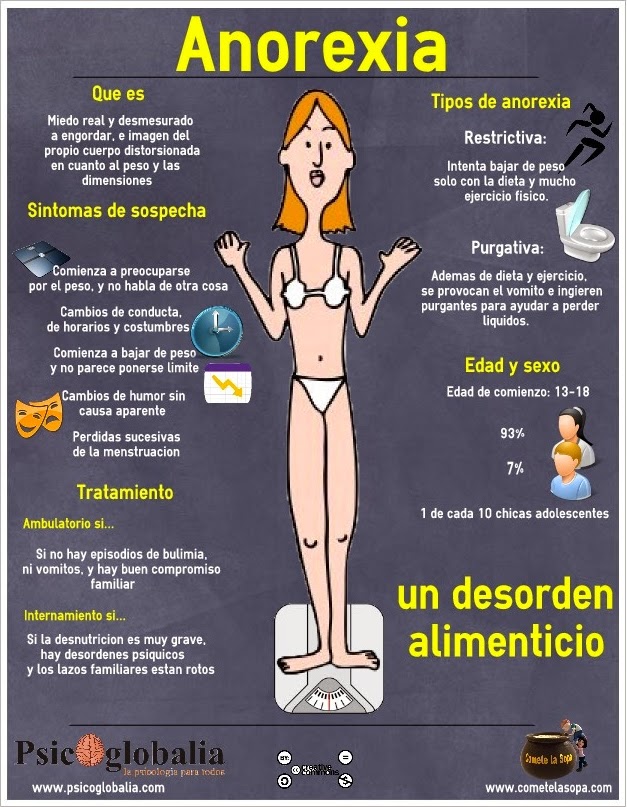

Risk factors may include:

- social factors

- biological makeup

- genetics

- psychological well-being

Additionally, some people living with bulimia may also have a history of anorexia nervosa or another eating disorder.

If you suspect your loved one needs help, it’s important to let them know that you’re there for them without any judgment. They may need you to just listen, or they might need your help finding and going to appointments.

Any progress should also be addressed with further encouragement.

Try saying things like:

- I’m here to listen.

- Can I help you with finding a doctor or mental health professional?

- Do you need help making an appointment? Can I drive you?

- You are a great person because _______.

- I appreciate you and I’m proud of you.

Avoid saying things like:

- You need to stop eating so much at once.

- Can’t you just stop purging?

- You need to get help.

- You look fine.

- Why are you worried about how you look?

- I don’t understand your behaviors.

- It’s all in your head or you’re just stressed.

Was this helpful?

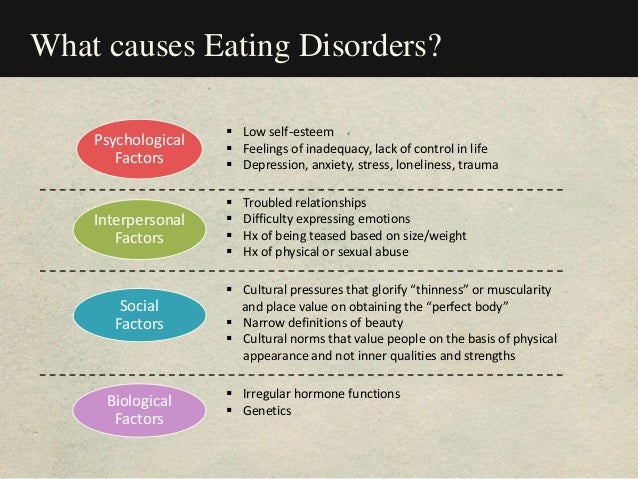

Bulimia has no single known cause. However, it’s thought that a combination of certain factors can influence its development. These can include:

- genes

- family history

- a past traumatic event

- social or cultural influences

A 2019 review, as well as some older research, also suggests that bulimia may also be associated with serotonin deficiencies in the brain. This important neurotransmitter helps regulate mood, appetite, and sleep.

A doctor typically uses a variety of tests to diagnose bulimia. First, they may conduct a physical examination. They may also order blood or urine tests.

They may also order blood or urine tests.

A psychological evaluation will help them understand your relationship with food and body image.

The doctor will also use criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The DSM-5 is a diagnostic tool that uses standard language and criteria to diagnose mental disorders.

The criteria used to diagnose bulimia include:

- recurrent binge eating

- regular purging through vomiting, excessive exercise, misuse of laxatives, or fasting

- deriving self-worth from weight and body shape

- binge eating and purging that happens, on average, at least once a week for 3 months

- not having anorexia nervosa

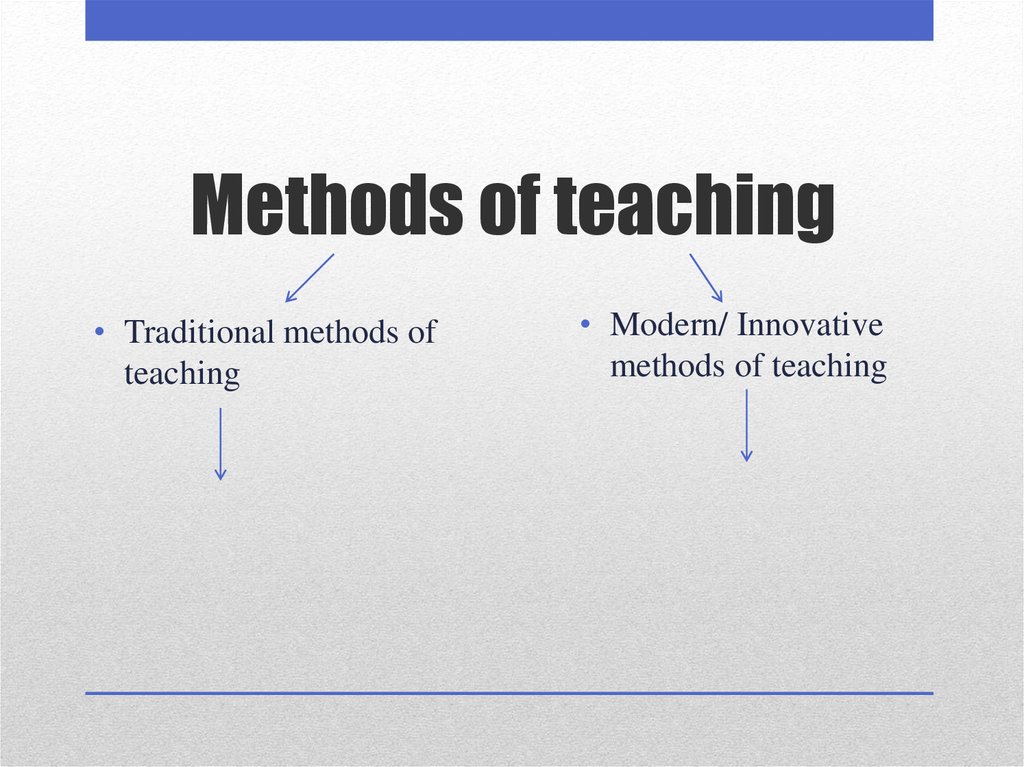

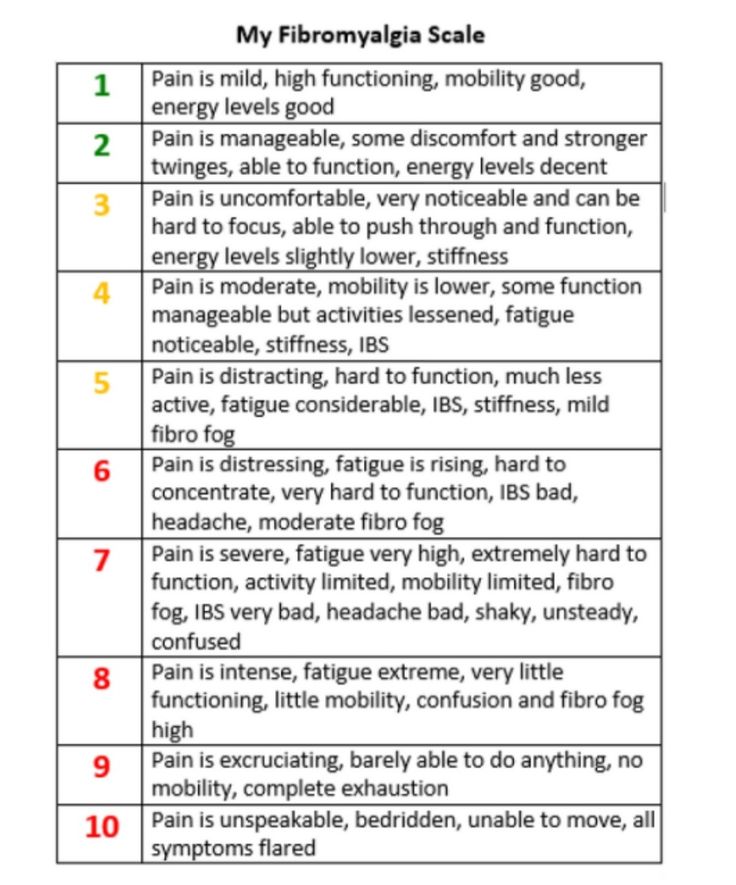

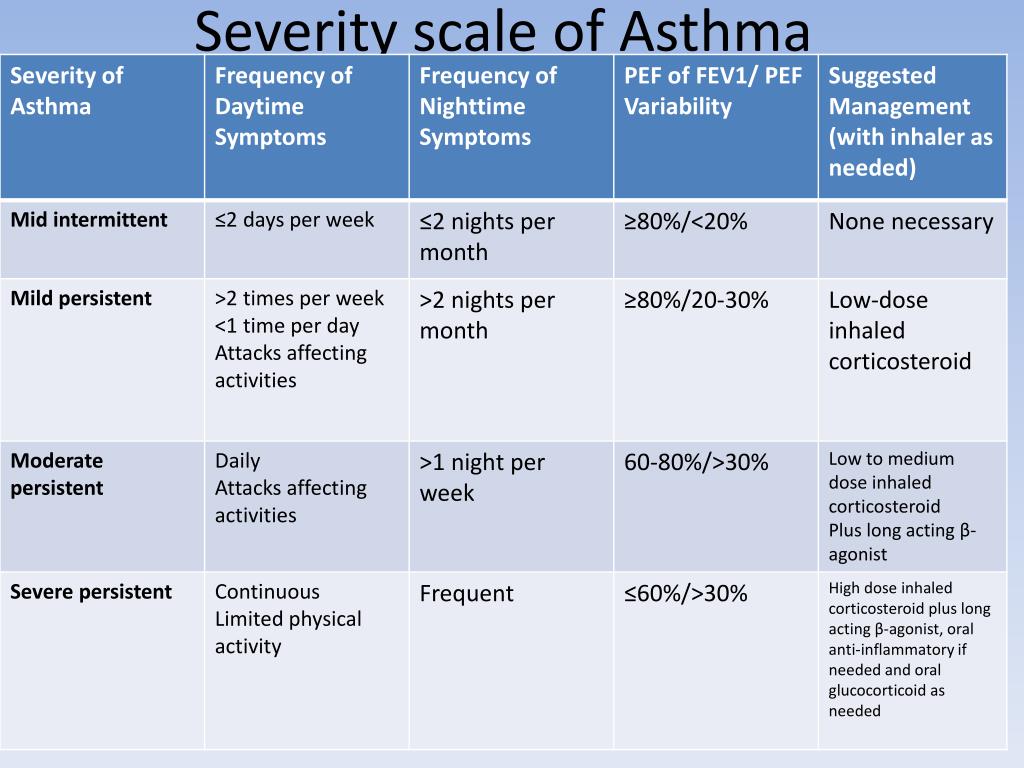

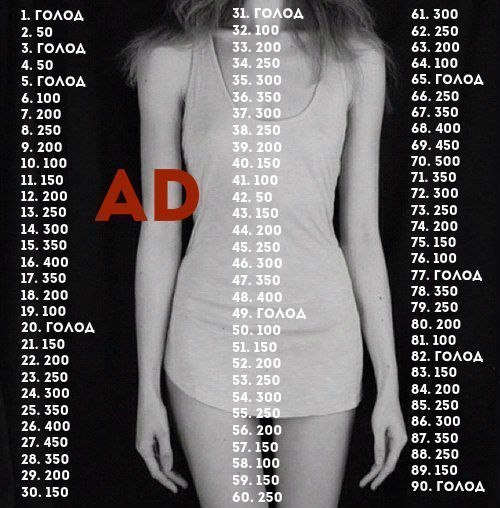

The DSM-5 also categorizes bulimia from mild to extreme:

- Mild: 1 to 3 episodes per week

- Moderate: 4 to 7 episodes per week

- Severe: 8 to 13 episodes per week

- Extreme: 14 or more episodes per week

You may need further tests if you’ve had bulimia for a long period of time. These tests can check for complications that could include problems with your heart or other organs.

These tests can check for complications that could include problems with your heart or other organs.

Treatment focuses on food and nutrition education as well as mental health treatment. It requires development of a healthy view of yourself and a healthy relationship with food.

Treatment options can include:

- Antidepressants. Currently, fluoxetine (Prozac) is the only antidepressant approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat bulimia. This selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor may also help with depression and anxiety. Fluoxetine is only approved for treating bulimia in adults.

- Psychotherapy. Also called talk therapy, this type of counseling can include cognitive behavioral therapy, family-based therapy, and interpersonal psychotherapy. The goal is to help you work through potentially harmful thoughts and behaviors that contribute to your condition. Group talk therapy may also be helpful.

- Dietitian support and nutrition education.

These can help you learn healthy eating habits and form nutritious meal plans. You may also learn to shift your attitudes toward food.

These can help you learn healthy eating habits and form nutritious meal plans. You may also learn to shift your attitudes toward food. - Treatment for complications. This may include hospitalization, especially for cases of severe dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and organ damage.

Successful treatment usually involves a combination of the above treatments, along with a collaborative approach between your doctor, mental health professional, and family and friends.

Some eating disorder treatment facilities offer live-in or day treatment programs. Some live-in programs provide around-the-clock support and care.

If you don’t already have a therapist, you can browse doctors in your area through the Healthline FindCare tool.

Bulimia can be life threatening if it’s left untreated or if the treatment fails. Bulimia is both a physical and psychological condition, and it may be a lifelong challenge to manage it.

However, there are several treatment options available that can help. Often, the earlier bulimia is detected, the more effective treatment may be.

Often, the earlier bulimia is detected, the more effective treatment may be.

Effective treatments focus on:

- food

- self-esteem

- problem solving

- coping skills

- mental health

These treatments can help you maintain healthy behaviors in the long term.

Bulimia is a type of eating disorder defined by eating large amounts of food in a short amount of time, followed by purging behaviors. While there are some known risk factors, there’s no single cause of bulimia.

It’s also important to know that this eating disorder can affect anyone.

If you suspect you or a loved one may be living with bulimia, it’s important to seek help from both a medical doctor and mental health professional.

Seeking prompt treatment may not only improve your quality of life, but it may also help prevent potentially life threatening complications.

Bulimia Nervosa - PsychDB

Table of Contents

Bulimia Nervosa

Primer

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Specifiers

Signs and Symptoms

Screening and Rating Scales

Pathophysiology

Differential Diagnosis

Investigations

Physical Exam

Treatment

Psychological

Pharmacological

Guidelines

Resources

Primer

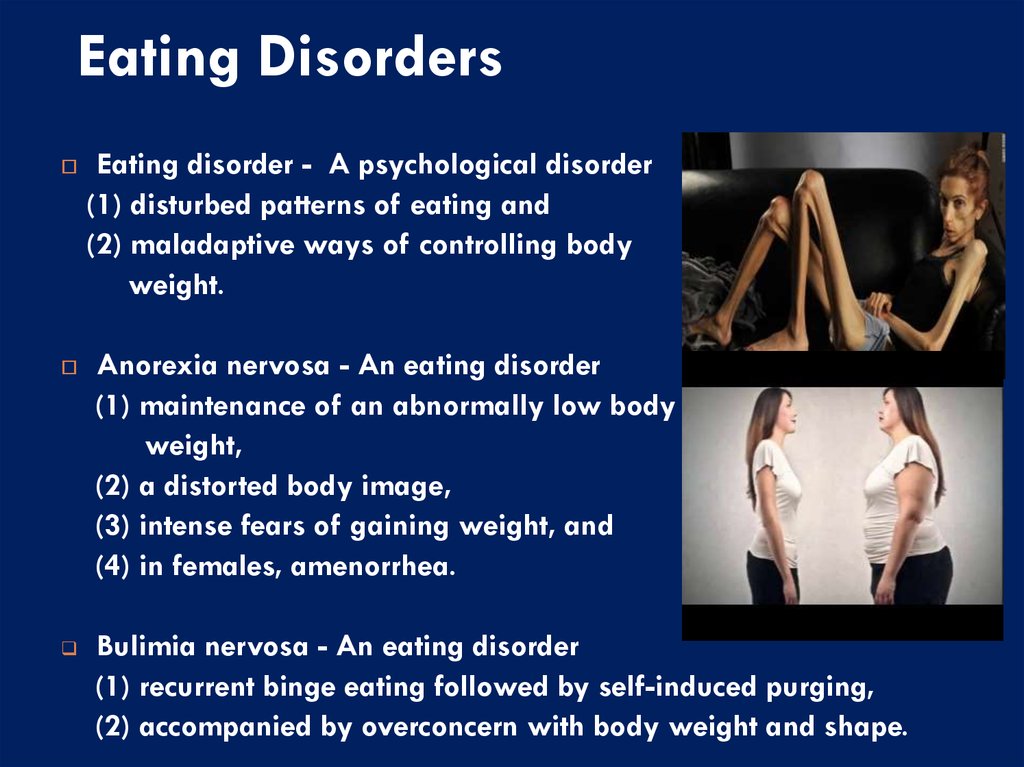

Bulimia Nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating, compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, and self-evaluation that is significantly influenced by body shape and weight.

Epidemiology

The 12-month prevalence in young females is 1 to 1.5%, with a peak in older adolescence and young adulthood.

Bulimia affects females significantly more than males (10:1).

Prognosis

Bulimia nervosa commonly begins in adolescence or young adulthood and onset before puberty or after age 40 is uncommon.

Binge eating most common starts during or after an episode of dieting to lose weight.

For many individuals, symptoms remit with or without treatment, but treatment improves outcomes.

There is an elevated risk for mortality, and the CMR (crude mortality rate) for bulimia nervosa is nearly 2% per decade (vs. 5% for anorexia nervosa).

Psychiatric Comorbidity

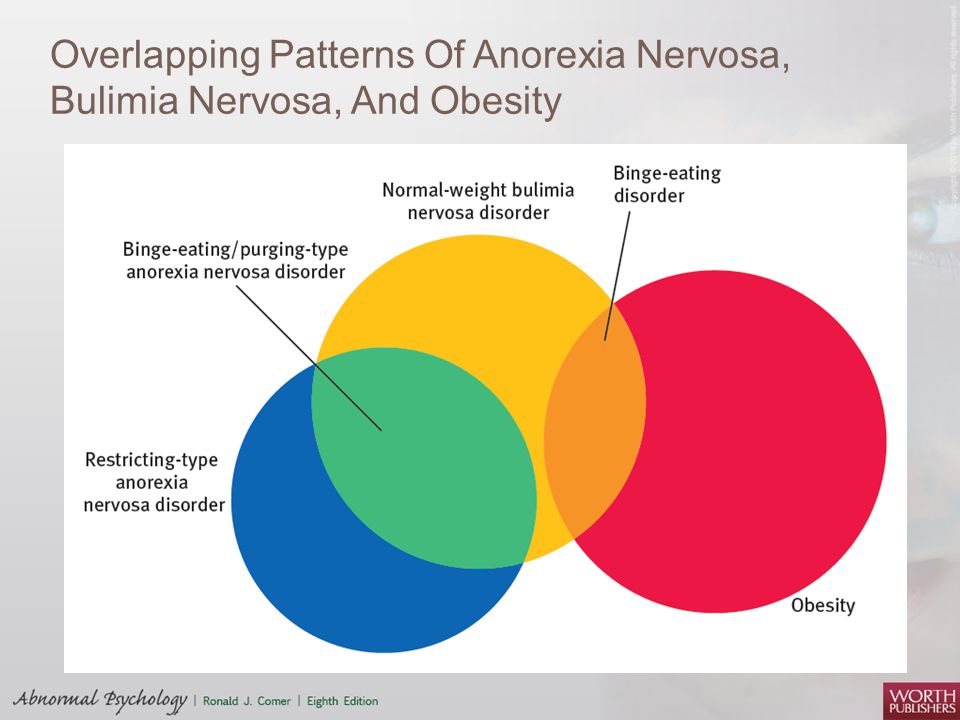

The conversion from initial bulimia nervosa to anorexia nervosa happens in a minority of cases (between 10 to 15%). Individuals who do cross-over to anorexia nervosa typically revert back to bulimia nervosa or have multiple occurrences of switching back and forth between these disorders.

A proportion of individuals with bulimia nervosa will continue to binge eat but no longer engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviours, and thus their symptoms will only meet criteria for binge-eating disorder or other specified eating disorder. Diagnosis should be based on the current (i.e. - past 3 months) clinical presentation.

There is an increased frequency of depressive symptoms (e.g. - low self-esteem) and depressive disorders in individuals with bulimia nervosa.

The lifetime prevalence of substance use, particularly alcohol or stimulant (in an attempt to control appetite and weight) use, is at least 30%.

A substantial percentage of individuals with bulimia nervosa also have borderline personality disorder.

Medical Comorbidity

Menstrual irregularity and/or amenorrhea can occur in females.

Fluid and electrolyte disturbances (e.g. - hyponatremia) from purging behaviours can sometimes cause serious medical complications.

Rare but potentially fatal complication include gastroesophageal rupture, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Individuals who chronically use laxatives to purge may become dependent and have constipation.

Risk Factors

Stressful life events, childhood obesity, early pubertal maturation, childhood sexual or physical abuse, social anxiety disorder, weight concerns, low self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and anxiety in childhood can increase the risk for bulimia nervosa.

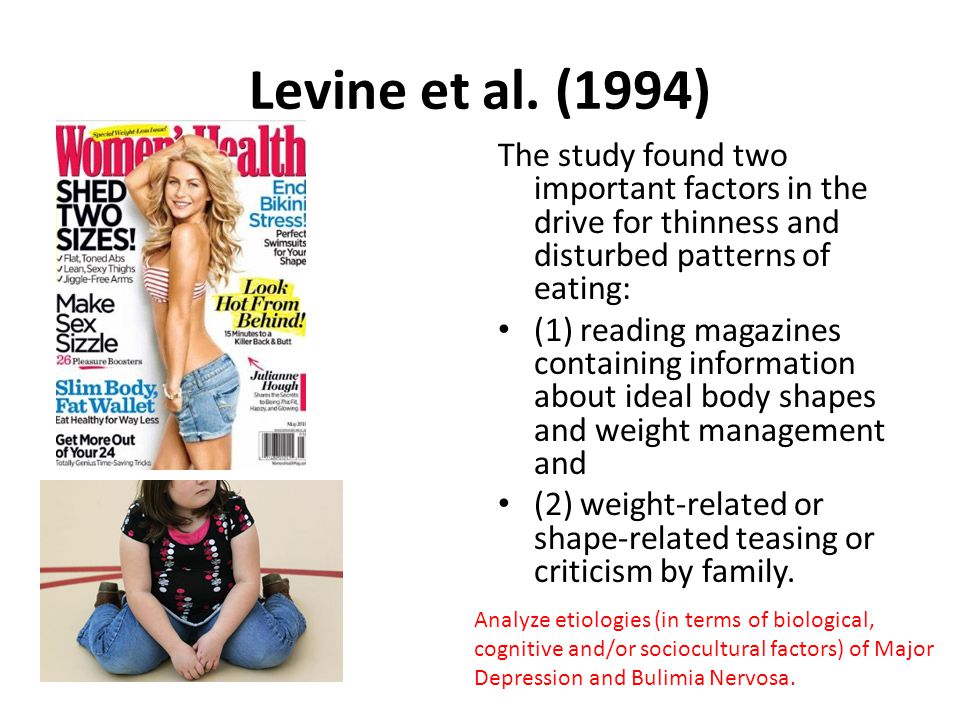

Internalization of a thin body ideal has been found to increase risk for developing weight concerns, which increases the risk for bulimia nervosa.

There may be genetic vulnerabilities for bulimia as well.

Cultural

See also: Cheng, Z. H., Perko, V. L., Fuller-Marashi, L., Gau, J. M., & Stice, E. (2019). Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eating behaviors, 32, 23-30.

Eating behaviors, 32, 23-30.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Criterion A

Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following:

Eating, in a discrete period of time (e.g. - within any

2-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances.A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e.g. - a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating).

Criterion B

Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviours in order to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise.

Criterion C

The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviours both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months.

Criterion D

Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.

Criterion E

The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa.

Specifiers

Specifiers

Specify if:

In partial remission: After full criteria for bulimia nervosa were previously met, some, but not all, of the criteria have been met for a sustained period of time.

In full remission: After full criteria for bulimia nervosa were previously met, none of the criteria have been met for a sustained period of time.

Severity Specifier

Specify if: The minimum level of severity is based on the frequency of inappropriate compensatory behaviours (see below). The level of severity may be increased to reflect other symptoms and the degree of functional disability.

Mild: An average of

1 to 3episodes of inappropriate compensatory behaviours per week.

Moderate: An average of

4 to 7episodes of inappropriate compensatory behaviours per week.Severe: An average of

8 to 13episodes of inappropriate compensatory behaviours per week.Extreme: An average of

14or more episodes of inappropriate compensatory behaviours per week.

Signs and Symptoms

An “episode of binge eating” is defined by the DSM-5 as eating, in a discrete period of time, an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances. This is a determination that is contextual and requires subjectivity of clinician judgment.

Some individuals do not report a feeling of loss of control but instead say they have abandoned any efforts to control their eating.

This can be considered as “loss of control” under the DSM-5 criteria.

This can be considered as “loss of control” under the DSM-5 criteria.The most common triggers for binge eating episodes include negative affect (emotions), interpersonal stressors; dietary restraint; negative feelings related to body weight, body shape, and food; and boredom

Binge eating usually occurs in secrecy or individuals will try to make it inconspicuous.

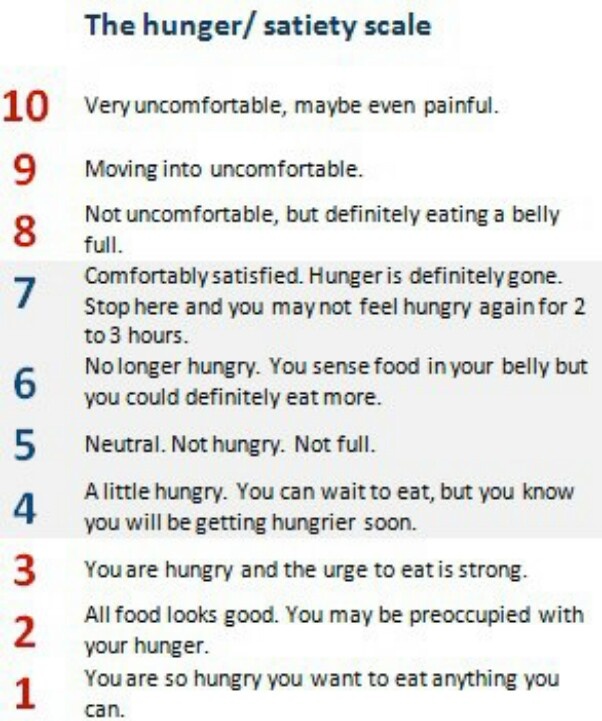

During binges, individuals tend to eat foods they would otherwise avoid, will eat until they are painfully or uncomfortably full.

The most common inappropriate compensatory behaviour is vomiting.

Individuals may use fingers or instruments to stimulate the gag reflex. Overtime, individuals may be able to vomit at will. Other purging behaviors include the misuse of laxatives and diuretics.

Outside of the episodes of bingeing, individuals will restrict their total caloric consumption and preferentially select low-calorie foods while avoiding foods that they perceive to be fattening or likely to trigger a binge.

Screening and Rating Scales

Eating Disorder Scales

| Name | Rater | Description | Download |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS) | Patient | A 22-item self-report scale for individuals between 13 to 65 years old that screens for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. | Link |

Pathophysiology

See also: Brambilla, F. (2001). Aetiopathogenesis and pathophysiology of bulimia nervosa. CNS drugs, 15(2), 119-136.

Differential Diagnosis

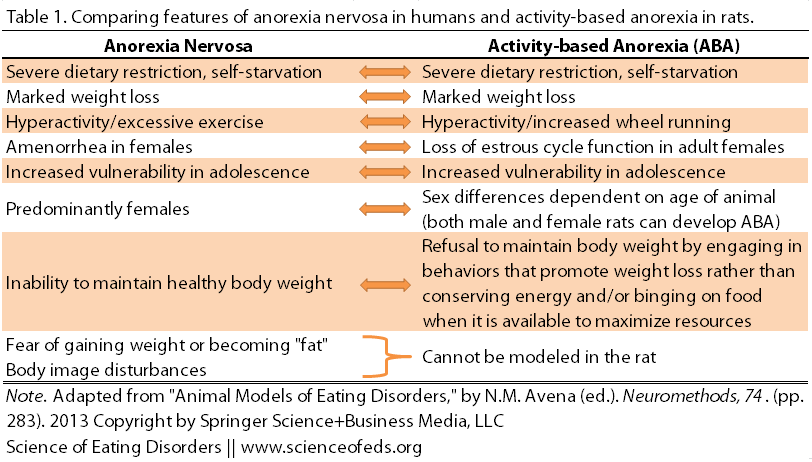

Anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type

Individuals whose binge-eating behaviour occurs only during episodes of anorexia nervosa are given the diagnosis anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type. These individuals should not be given the additional diagnosis of bulimia nervosa.

Individuals with an initial diagnosis of anorexia nervosa who then binge and purge but whose presentation no longer meets the full criteria for anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type (e.

g. - when weight is normal according to BMI), a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa should be given only when all criteria for bulimia nervosa have been met for at least

g. - when weight is normal according to BMI), a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa should be given only when all criteria for bulimia nervosa have been met for at least 3months.The other key differences between bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa is that:

A diagnosis of bulimia nervosa should not be given when the disturbance occurs only during episodes of anorexia nervosa.

Individuals with bulimia are typically within the normal weight or overweight range (BMI >18.5 and <30 in adults).

Binge-eating disorder

Individuals who binge eat but do not engage in repeated, inappropriate compensatory behaviors should have a diagnosis of binge-eating disorder considered instead.

Kleine-Levin syndrome

In neuropsychiatric disorders such as Kleine-Levin syndrome, there is also disturbed eating behaviour.

However, the characteristic feature of bulimia nervosa, concern and self-evaluation with body shape and weight, are not present.

However, the characteristic feature of bulimia nervosa, concern and self-evaluation with body shape and weight, are not present.

Major depressive disorder, with atypical features

Overeating is common in major depressive disorder, with atypical features (atypical depression). However, there is no inappropriate compensatory behaviors and they do not exhibit the excessive concern with body shape and weight characteristic of bulimia nervosa. If criteria for both disorders are met, both diagnoses should be given.

Borderline personality disorder

Binge-eating behaviour makes up part of the impulsive behaviours seen in borderline personality disorder. If the criteria for both borderline personality disorder and bulimia nervosa are met, both diagnoses should be given.

Investigations

See also: Rushing, J. M., Jones, L. E., & Carney, C. P. (2003). Bulimia nervosa: a primary care review. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 5(5), 217.

P. (2003). Bulimia nervosa: a primary care review. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry, 5(5), 217.

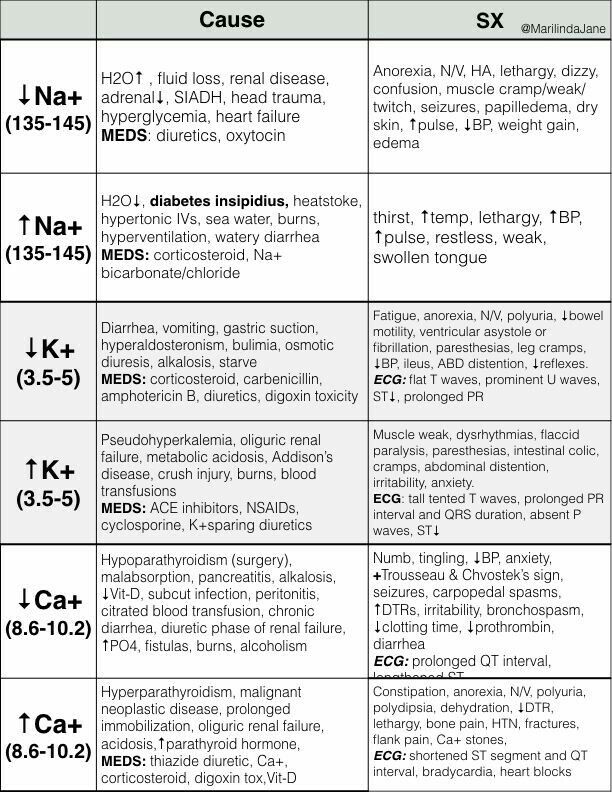

Various laboratory abnormalities can be present:

Fluid and electrolyte abnormalities (hypokalemia, hypochloremia, and hyponatremia)

Loss of gastric acid through vomiting may produce a metabolic alkalosis (elevated serum bicarbonate)

Frequent purging through laxative and diuretic abuse can cause metabolic acidosis.

Mildly elevated levels of serum amylase (from increase in the salivary isoenzyme)

ECG may show cardiac arrhythmias (due to hypokalemia)

Thus, standard investigations include:

CBC, electrolytes, extended electrolytes, renal function (Cr, eGFR, BUN), albumin level, serum amylase, liver function (AST, ALT, GGT), cholesterol, and an electrocardiogram.

Physical Exam

Oral examination may reveal permanent loss of enamel (in particular lingual surfaces of the front teeth) from recurrent vomiting, dental carries, and salivary gland and parotid gland hypertrophy

Perioral irritation, and oral ulcers may also be noticeable

Hand examination may reveal calluses on the back of hand (from repeated contact with teeth)

Dermatological exam may reveal petichiae

A cardiac exam may be warranted to assess for arrhythmias, edema, and decreased volume status.

Gastrointestinal exam may reveal non-focal abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, signs of constipation. Rarely some individuals may have signs or symptoms of esophageal tears, or gastric rupture. Chronic use of laxatives may also result in constipation and/or rectal prolapse.

Treatment

Psychological

Various forms of psychotherapy have been found to be effective for treatment of bulimia, including:

Individual therapy (CBT, IPT, behavioural, and psychodynamic approaches)

Group therapy (CBT, IPT, supportive, and psychodynamic approaches)

Family and couples self-help, online resources, 12 step programs

Recommended Reading

Buy on Amazon

PsychDB is an Amazon Associate and earns from qualifying purchases. Thank you for supporting our site!

Pharmacological

Antidepressant medications have been shown to be helpful (can reduce binge eating and purging) in treating bulimia, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine.

This may be based on elevating central 5-hydroxytryptamine levels.

Thus, SSRIs can be used for particularly difficult binge-purge cycles that do not respond to psychotherapy alone.

Combination of CBT and fluoxetine has highest remission rates compared to either treatment alone.

Imipramine, desipramine, trazodone, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) have also been investigated but are less frequently used.

Medication is helpful in patients with comorbid depressive disorders and bulimia nervosa.

Bupropion is contraindicated due to increased seizure risk in individuals in eating disorders.

Guidelines

See also: Psychiatry Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs)

Resources

For Patients

KeltyMentalHealth: Eating Disorders

For Providers

Articles

Research

References

1) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

(2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

2) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

3) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

4) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

5) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

6) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

7) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

8) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

(2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

9) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

10) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

11) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

12) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

13) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

14) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

15) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

(2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

16) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

17) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

18) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

19) American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

20) Yager, Joel, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. American Psychiatric Association, 2006. Third Edition

21)Guideline Watch for the Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Eating Disorders 11

22)Israël, M. (2002). Should some drugs be avoided when treating bulimia nervosa?. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 27(6), 457.

(2002). Should some drugs be avoided when treating bulimia nervosa?. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 27(6), 457.

Diagnostic criteria for eating disorders - Psychotherapist Sergei Melnikov

Formal signs of eating disorders from anorexia to psychogenic overeating

Warning: this page is for informational purposes only and is intended for professionals. These criteria do not serve for self-diagnosis purposes and may cause/increase anxiety in people who are overly concerned about their health.

On this page I have posted the formal diagnostic criteria that guide a psychiatrist or psychotherapist when making a diagnosis. Categories of diseases are described by increasing severity (subjectively according to the author), indicating the code from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10th revision. The only disease not included in the ICD-10 is Binge eating disorder , given with formal criteria from the latest version of the American Psychiatric Handbook - DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). First, the commonly used colloquial form is indicated, then the cipher and its description in the reference book with a few comments.

First, the commonly used colloquial form is indicated, then the cipher and its description in the reference book with a few comments.

Stress eating / Psychogenic overeating. F50.4 Overeating associated with other psychological disorders

Diagnostic criteria

Regular and systematic overeating due to stressful events such as bereavement, accident, childbirth, etc.

Comments

A common cause that leads to alimentary obesity. The formal reason for weight gain in this case is still excess nutrition: the daily calorie content of food exceeds the caloric content of consumption. However, in the case of psychogenic overeating, a person resorts to food not as a satisfaction of physical hunger, but as a "comforter" from emotional problems. In a psychological sense, this option is similar to emerging alcoholism: “I rarely drink, mostly to relax. It happens when I get nervous. But I can quit at any time." True, with psychogenic overeating, a person is not worried about a hangover, there are no physical / mental problems (memory / attention impairment) in the case of systematic “abuse” of food.

If we are talking about short-term jamming (weeks), the psychotraumatic situation will be resolved, then the person may stop jamming, remaining, perhaps with a slight plus on the scales, which can return to normal. But if the conditions of stress do not change (daily unloved work / regular problems within the family) or a person has no other ways to solve their psychological problems, then the condition can progress and worsen. Gradually leading to the following diagnosis ↓

Binge eating disorder

1. Repeated cases of gluttony. The binge episode is characterized by:

- Eating in a given period of time (eg 2 hours) an amount of food that is significantly more than most people would eat in the same period of time under the same circumstances.

- Feeling of loss of control over eating during the episode. For example, the feeling that a person cannot stop eating or control what and how much they eat.

2. Overeating is associated with three (or more) of the following:

- The person eats much faster than usual.

- The person eats until there is a feeling of excessive and uncomfortable fullness in the stomach.

- A person eats a large amount of food without feeling physical hunger.

- A person eats alone because he is shy about the amount of food he eats.

- The person feels self-loathing, depression, or guilt about overeating.

3. There is distress (negative stress) due to overeating.

4. Overeating occurs at least 2 days every week for 6 months.

5. Overeating is not accompanied by regular "cleansing" and occurs not only during bouts of bulimia or anorexia.

Comments

To continue the analogy with alcoholism, in this case we are talking about loss of control, food failures or "binges". A sense of guilt is formed (imagine an alcoholic remembering "ugly" yesterday), avoidance of eating in the company may be formed. At this stage, there may be no criticism of your condition or it may be external / formal: "I can always stop my overeating if I want. " Unfortunately, this condition is formed for a long time (a formal sign is from 6 months) and gradually. As a rule, the help of a specialist is already needed to resolve this problem.

" Unfortunately, this condition is formed for a long time (a formal sign is from 6 months) and gradually. As a rule, the help of a specialist is already needed to resolve this problem.

Further diagnoses may be based on quite pronounced disorders in the mental / physical sphere, therefore their diagnosis is possible only from a specialized specialist: a psychiatrist / psychotherapist. In extreme cases, the diagnosis can be carried out by a clinical psychologist who has sufficient experience in working with this pathology.

F50.2 Bulimia nervosa

Diagnostic criteria

- A. There are recurrent episodes of binge eating (at least twice a week for a three-month period) in which a large amount of food is consumed in a short period of time.

- B. There is a constant preoccupation with eating, a strong desire or obsessive desire to eat.

- C. The patient tries to counteract the effect of obesity from food intake by using one of the following methods:

- self-induced vomiting;

- self-administration of laxatives;

- intermittent periods of fasting;

- use of drugs, in particular appetite suppressants; thyroid drugs or diuretics; if bulimia develops in diabetic patients, they may neglect insulin therapy.

- D. Patients perceive themselves as too fat, there is an obsessive fear of getting fat (which usually leads to underweight).

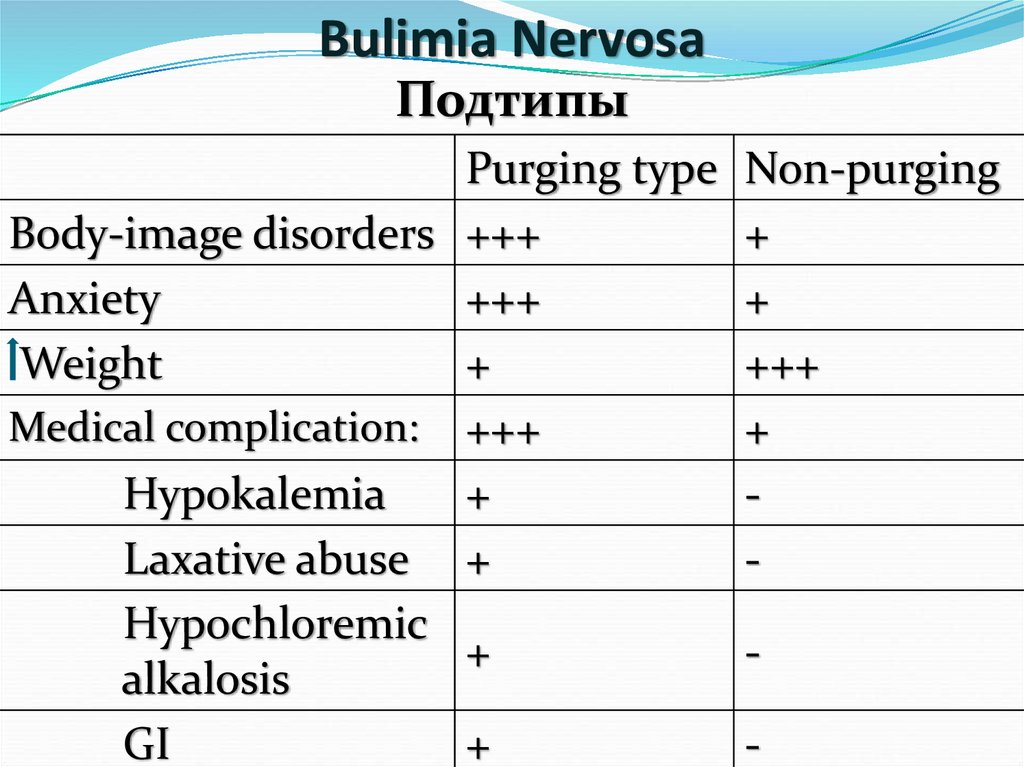

Purging type: during an episode of bulimia, the person regularly induces vomiting, uses laxatives, diuretics, or enemas

Non-purging type: during an episode of bulimia, the person uses inappropriate compensatory behaviors such as fasting or excessive physical activity, but does not artificially induce vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, etc. on a regular basis.

F50.3 Atypical bulimia nervosa

Diagnostic criteria

A disorder that has some features of bulimia nervosa, but the overall clinical picture does not allow for this diagnosis. For example, there may be repeated bouts of binge eating and overuse of laxatives without significant changes in body weight, or there may be no typical overconcern with one's own figure and body weight.

F50.

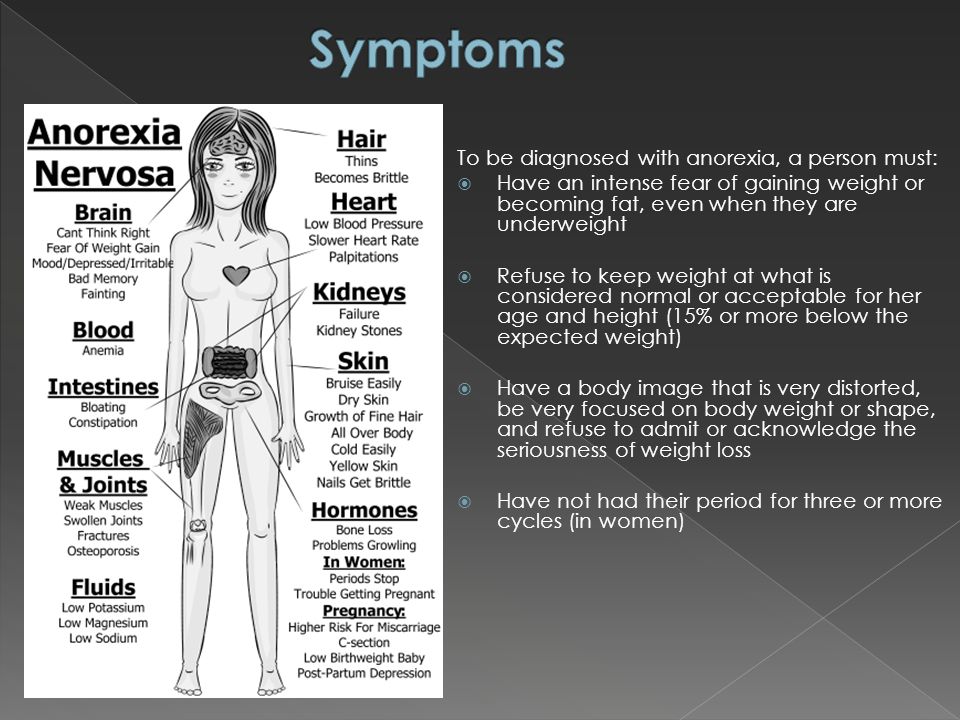

0 Anorexia nervosa

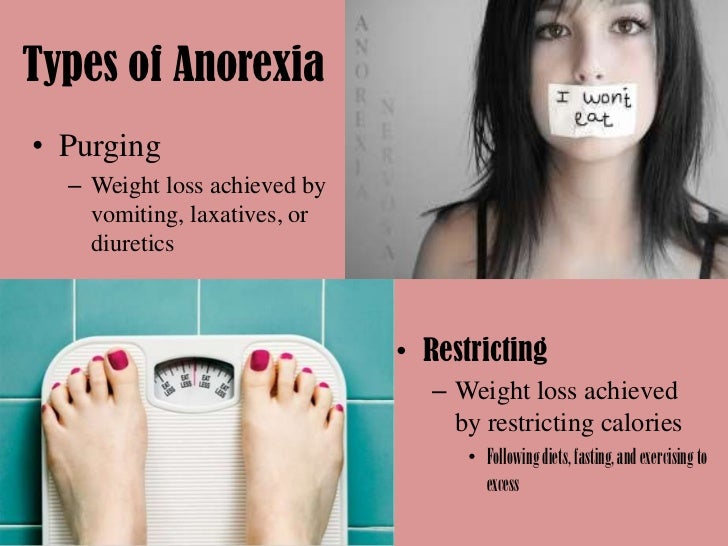

0 Anorexia nervosa Diagnostic criteria

- A. There is weight loss resulting in a body weight that is at least 15% below normal or expected for age or height, or a BMI of 17.5 or less.

- B. Weight loss is caused by the patients themselves, which is achieved by avoiding "fatty foods".

- C. Patients perceive themselves as too fat, there is an obsessive fear of getting fat, as a result of which the patient considers only very low weight acceptable for himself.

- D. A general endocrine disorder ... manifested in women by amenorrhea and in men by loss of libido and potency (an obvious exception is the persistence of menstrual bleeding in anorexic women on hormone replacement therapy).

- E. This disorder does not meet criteria A and B for bulimia nervosa (F50.2).

The following features support the diagnosis, although are not necessary:

- self-induced vomiting,

- self-administration of laxatives,

- excessive gymnastic exercises;

- use of appetite suppressants and/or diuretics.

Inhibitory type: during an anorexia attack, a person does not regularly overeat or purge (induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas).

Overeating-Purifying Type: During an anorexia attack, the person regularly overeats or purges.

Comments

Most often, the disorder occurs in adolescent girls and young women, but adolescent boys and young men, as well as children approaching puberty and older women up to menopause, can also become ill. It should be noted that patients often dissimulate (conceal/deny) their condition. In this case, anorexia nervosa presents significant difficulties in diagnosis and treatment and rehabilitation tactics, even for doctors of other specialties who have not encountered this in their practice.

F50.1 Atypical anorexia nervosa

A disorder that shares some of the features of anorexia nervosa, but whose overall clinical presentation does not warrant this diagnosis. Thus, one of the key symptoms of the above disorder, such as amenorrhea or severe fear of obesity, may be absent in the presence of marked weight loss and behavior aimed at achieving weight loss.

Thus, one of the key symptoms of the above disorder, such as amenorrhea or severe fear of obesity, may be absent in the presence of marked weight loss and behavior aimed at achieving weight loss.

Affective pathology in patients with adolescent bulimia nervosa

Currently, many researchers [1-4] note a decrease in the age of patients during the period of manifestation of bulimia nervosa (NB) and an increase in its prevalence in the second decade of life. This makes the problem of bulimic spectrum disorders relevant to child and adolescent psychiatry.

One of the important aspects of the problem under consideration is the high level of comorbid pathology in NB, which aggravates the mental state of patients and makes it difficult to carry out therapeutic measures. Depression has long attracted particular attention in this respect. A significant frequency of depressive states in patients was noted even at the first description of NB by G. Russell [5]. At the end of the 20th century, a number of foreign psychiatrists [6, 7] even tried to consider NB as a variant of endogenous depression. In addition, it was found [8] the accumulation of cases of mood disorders in the families of patients with NB and of patients with NB in the families of patients with depression, which gave reason to assume the presence of common etiological factors in these diseases. There are observations [9] that low mood in patients with ND increases the urge to eat, and the severity of the negative affect significantly correlates with the number of episodes of overeating. The most obvious comorbid relationship is observed between NB and bipolar affective disorder (BAD), especially type II (combination of major depressive episodes and hypomania) according to DSM-5 [10], and this comorbidity is associated with an early onset and more severe course of affective illness [11— 13].

In addition, it was found [8] the accumulation of cases of mood disorders in the families of patients with NB and of patients with NB in the families of patients with depression, which gave reason to assume the presence of common etiological factors in these diseases. There are observations [9] that low mood in patients with ND increases the urge to eat, and the severity of the negative affect significantly correlates with the number of episodes of overeating. The most obvious comorbid relationship is observed between NB and bipolar affective disorder (BAD), especially type II (combination of major depressive episodes and hypomania) according to DSM-5 [10], and this comorbidity is associated with an early onset and more severe course of affective illness [11— 13].

Comorbid NB affective disorders in adolescent patients are still little studied. We can only point to works that have shown that in adolescent girls suffering from NB, the risk of developing both “major” depression and dysthymia exceeds the population [3], and that in this age group, dysthymia is detected in patients with NB more often than severe depressive states [14]. This suggests that affective pathology may be a risk factor for the development of eating disorders (EDD).

This suggests that affective pathology may be a risk factor for the development of eating disorders (EDD).

The purpose of this study was to study the features of affective pathology in patients with NB of childhood and adolescence, comorbid interactions of these diseases, as well as the role of mood disorders in the development of ED.

Material and methods

The initial sample included 57 female adolescents with a typical form of NB, who in 2009-2016. were consulted at the Department of Child Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the Russian Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, as well as in the departments of children and adolescents of the Scientific and Practical Center for Mental Health of Children and Adolescents and Psychiatric Hospital No. 15 of Moscow. After that, 52 (91%) of patients whose condition met the criteria for F50.2 - typical NB and F30-F39 - mood disorders. Patients with primary endocrine pathology and schizophrenia spectrum disorders were excluded.

The age of patients ranged from 13.9 to 17.4 years (mean 16.4±0.9 years). Duration N.B. at the start of the study ranged from 3.5 to 28 months (mean 11.1±7.2 months). Body mass index (BMI) was in the range of 18.6–28.7 kg/m 2 (mean — 22.0±2.4 kg/m 2 ), i.e. none of the patients showed both protein-energy deficiency and obesity.

To assess the severity of eating disorders, the scale-questionnaire "test of attitude to food" - EAT-26, which is one of the most common tools for studying eating disorders [15-17], was used. Determination of the severity of affective pathology was carried out both by the psychopathological method and using the Beck Depression Scale [18–20].

After an outpatient consultation or discharge from the hospital, patients were observed follow-up for 1 to 7 years.

Statistical processing of the results was performed using the statistical computer program AtteStat [21].

Results

Clinical features and dynamics of the development of NB and comorbid affective disorders made it possible to distinguish three main groups of patients.

The first group included 18 (35%) girls who developed NB against the background of autochthonous depressive episodes.

The manifestation of NB in these cases occurred at the age of 14.6-17.0 years (mean 15.8±0.8 years). It was preceded by an anorexic stage lasting from 1.5 to 13 months (mean 6.5±4.7 months), the clinical manifestations of which in 5 (28%) patients met the criteria for typical anorexia nervosa (AN), and in 13 (72%) - atypical.

In the family history of patients in this group of relatives of the first and second degree of kinship, psychopathological manifestations of the affective spectrum during life were detected in all 18 (100%) cases: in 10 (56%) depressive episodes, and in 6 (33%) - repeated, in 6 (33%) - hyperthymic affective temperament; in 2 (11%) - dysthymia. Mothers of 5 (28%) patients had ED during their lifetime: typical AN in 2 (11%) cases, atypical AN in 3 (17%) cases. Alcohol dependence was diagnosed in 6 (33%) relatives, anxiety-phobic manifestations were diagnosed in 4 (22%) relatives.

The premorbid personality of 14 (78%) patients of the first group was determined by a combination of psychasthenic and hysterical traits expressed to one degree or another, and 4 (14%) - psychasthenic and schizoid, and in all patients the noted personality traits did not go beyond character accentuation [22 ].

In all 18 cases, the development of depression was 3—11 months ahead of the manifestation of N.B. The age of the patients at the onset of depression varied from 12.9 to 15.4 years (mean 14.1 ± 0.8 years). ) — with dysphoria and 4 (22%) — with melancholy, in the form of anxious-adynamic, adynamic-dysphoric and melancholy-adynamic states.

In 13 (72%) cases, depression preceded the anorexic stage and proceeded with a significant severity of the dysmorphophobic symptom complex, corresponding in clinical manifestations to juvenile dysmorphophobic depression [23, 24]. Depressive dysmorphophobic experiences gradually formed into an overvalued idea of dissatisfaction with one's figure and the need to improve it, which led to more and more strict diets, weight loss and the development of AN.

In another 5 (28%) cases, depression manifested itself already in the period of "anorexic" symptoms. In the opinion of most researchers [20, 25-27], food restriction, lack of intake of precursors of various biologically active substances, including serotonin, hormonal imbalance and hunger stress play the role of a provoking factor in the development of depression in patients with AN.

After the manifestation of the NB itself, the severity of depressive manifestations increased, which was facilitated by severe distress associated with the need to constantly resist increased appetite, the realization of the inability to control the process of nutrition, to realize the overvalued idea of gaining an ideal figure, global failure in life and impotence; depressive ideas of self-abasement and dissatisfaction with oneself took the form of self-accusations of lack of will, overeating and cleansing behavior. During this period, depression reached moderate severity, in 15 (83%) cases there was a vitalization of negative affect, in 14 (78%) - endogenous circadian rhythm, in 15 (83%) - suicidal thoughts, in 4 (22%) - suicidal attempts. , and in 3 (17%) - auto-aggressive actions in the form of episodic self-cutting.

, and in 3 (17%) - auto-aggressive actions in the form of episodic self-cutting.

Statistically significant correlations were obtained for the severity of affective symptoms and ED, assessed using the Beck Depression Scale and EAT-26: Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.624; p = 0.005 (checking the normality of the distribution was carried out according to the Shapiro-Wilk test).

Follow-up observation of patients made it possible to identify two main variants of the dynamics of NB and associated affective disorders. In the first variant, which was observed in 14 (78%) patients, depression was replaced by an episode of hypomania, accompanied by a smoothing of the eating disorder, and further alternation of depressive and hypomanic states with exacerbation of NB in the depressive phase and reduction in the hypomanic phase. The condition could be regarded as BAD type II with a course close to continual. In 6 (33%) patients, throughout the follow-up follow-up, approximately equal duration of hypomanic and depressive states with clinically significant manifestations of NB in the depressive phase remained, and in 8 (44%) patients, a gradual increase in the duration of hypomania was observed, accompanied by a reduction and decrease in the severity of depression, for several years, stable hypomania was formed with complete remission of NB.

In the second variant of the dynamics, observed in 4 (22%) patients, there were prolonged recurrent unipolar depressive states with eating disorders [28], interspersed with short-term incomplete (symptomatic) remissions. With repeated episodes, a gradual decrease in the severity of depressive affect was observed, the clinical manifestations of NB also softened, transforming into atypical, often difficult to differentiate ED.

The second group included 7 (13%) patients in whom NB developed in comorbid relationship with reactive depression caused by long-acting or combined psychotraumatic effects (death of a close friend, departure from the family of a beloved father, inability to take the usual leadership positions in a new group of peers, failure to enter a prestigious educational institution, etc.).

NB symptoms appeared at the age of 14.8-16.3 years (mean - 15.6±1.2 years). There were no statistically significant differences in the age of patients during the manifestation period in the second group compared to the first. In all 7 (100%) cases, the development of NB was preceded by a short - 1-1.5 month anorexic stage, which did not reach the severity of typical AN.

In all 7 (100%) cases, the development of NB was preceded by a short - 1-1.5 month anorexic stage, which did not reach the severity of typical AN.

In a family history of relatives of the first and second degree of kinship, 3 (43%) patients were diagnosed with depressive states (in 2 cases, psychogenically provoked), in 3 (43%) - anxiety-phobic disorders, in 2 (29%)%) - alcohol addiction.

In the pre-manifest period, the personality of patients was determined by a combination of psychasthenic radicals with hysterical traits expressed to one degree or another, which did not go beyond a clear accentuation of character [22].

The onset of psychogenic depression in these cases was 2–5 months ahead of the manifestation of NB. The structure of affect was dominated by astheno-adynamic manifestations, combined with anxiety and irritability. In 3 (43%) patients, autoaggressive actions (self-cutting) were noted. Depressive ideas of low value, dissatisfaction with oneself and one's appearance, overvalued dysmorphophobic constructions with explanations of life failures by figure flaws and subsequent attempts to correct them, which were in the nature of an irresistible pessimistic fixation on the embodiment of overvalued ideas, quickly joined the psychogenic experiences dominant in the mind. This group of patients was characterized by a rapid transformation of anorexic symptoms into typical N.B. The development of the latter was accompanied by a significant deepening of depressed mood and endogenization of depression, when the situation that caused it ceased to sound in the experiences of patients and the affect of melancholy became predominant with vitalization in 4 (57%) patients and an endogenous circadian rhythm in 2 (29%).

This group of patients was characterized by a rapid transformation of anorexic symptoms into typical N.B. The development of the latter was accompanied by a significant deepening of depressed mood and endogenization of depression, when the situation that caused it ceased to sound in the experiences of patients and the affect of melancholy became predominant with vitalization in 4 (57%) patients and an endogenous circadian rhythm in 2 (29%).

Follow-up observation in this group of patients showed favorable dynamics of both NB and affective disorders. Against the background of complex therapy, there was a fairly rapid (within 3-6 months) improvement in mood and smoothing of the manifestations of NB. In the future, these patients formed a stable remission. Weight and BMI returned to pre-illness levels, and there was no significant negative psychological response to weight gain. After 4-7 years, all patients showed a complete absence of eating disorders and other maladaptive psychopathological manifestations, they successfully studied at universities, worked, had a fairly wide circle of friends, various hobbies and interests. In 4 (57%) patients, these changes reached the degree of mild hypomanic states, suggesting the development of "subthreshold" bipolar disorder [29, thirty].

In 4 (57%) patients, these changes reached the degree of mild hypomanic states, suggesting the development of "subthreshold" bipolar disorder [29, thirty].

The third group included 27 (51%) patients who developed NP in close association with chronic mood disorders that met the ICD-10 criteria for dysthymia. In this group, the manifestation of NB occurred at the age of 14.2-16.7 years (mean - 15.1±0.8 years). Development of N.B. was preceded by a long period - from 6 months to 3 years (mean - 18 ± 8.1 months) of atypical anorexic eating disorders with dissatisfaction with one's figure, "fear of fullness", repeated periods of diets followed by breakdowns and fluctuations in body weight. There were no cases of typical AN in this group.

Family history of 11 (41%) patients in relatives of the first and second degree of kinship during their lives revealed anxiety-phobic disorders, 7 (26%) - alcohol dependence, 6 (22%) - dysthymia (in 3 (11%) %) cases with episodes of double depression), hyperthymic affective temperament in 6 (22%) cases, mild depressive episodes in 3 (11%) cases (recurrent in 2 (7%) cases). Clinically significant eating disorders were also not observed, however, 11 (41%) mothers of patients showed excessive attention to the figure, constantly expressed concerns about weight gain, overeating, "the inherited constitution that predisposes them to fullness."

Clinically significant eating disorders were also not observed, however, 11 (41%) mothers of patients showed excessive attention to the figure, constantly expressed concerns about weight gain, overeating, "the inherited constitution that predisposes them to fullness."

The premorbid personality of 16 (59%) patients was determined by a combination of psychasthenic (closer to anancastic) and hysterical radicals expressed to one degree or another, 5 (19%) - psychasthenic and schizoid, 2 (7%) - hysterical and schizoid, 2 (7 %) - anancaste features that did not go beyond the explicit accentuation of the character [22]. This gave reason to believe that in the genesis of chronic mood disorders in the third group of patients, the main role, apparently, was played by hereditary-constitutional factors. We are talking about the constitutionally depressive variant of cycloid personalities, identified by P.B. Gannushkin [31], or depressive temperament described by H. Akiskal and G. Mallaya [32]. Disorders of emotions and mood began to manifest themselves already at preschool and primary school age, and in adolescence they developed into a picture of dysthymia, in the structure of which adynamia with irritability, dysphoria, and anhedonia predominated. As one of the 15-year-old patients noted: “For as long as I can remember, from the age of 6-7, the mood was almost always sad, dull, angry.”

Disorders of emotions and mood began to manifest themselves already at preschool and primary school age, and in adolescence they developed into a picture of dysthymia, in the structure of which adynamia with irritability, dysphoria, and anhedonia predominated. As one of the 15-year-old patients noted: “For as long as I can remember, from the age of 6-7, the mood was almost always sad, dull, angry.”

Against the background of stable hypothymia with low self-esteem and dissatisfaction with oneself, dysmorphophobic experiences easily arose, a steady rejection of one's figure, a dependence of mood on body weight and an overvalued desire to reduce weight were formed. Already in primary and secondary school age, hypothymia was combined with symptoms of dysmorphophobia and individual attempts to limit food intake with subsequent breakdowns; by the age of 12-13, such attempts became regular and constituted the essence of a protracted anorexic stage.

The manifestation of NB itself was accompanied by a deepening of mood disorders, reaching the level of double depression (an episode of "major" depression against the background of dysthymia [10, 33]), in the structure of which adynamic, dysphoric and hysteroform manifestations predominated, accompanied by melancholy and anxiety, often with vitalization . In these cases, there were statistically significant positive correlations between the severity of affective symptoms and NB, assessed using the Beck Depression Scale and the EAT-26 questionnaire, with Pearson's correlation coefficient values of r = 0.867 ( p = 0.0001) and r = 0.753 ( p = 0.0003), respectively (the normality of the distribution was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test).

In these cases, there were statistically significant positive correlations between the severity of affective symptoms and NB, assessed using the Beck Depression Scale and the EAT-26 questionnaire, with Pearson's correlation coefficient values of r = 0.867 ( p = 0.0001) and r = 0.753 ( p = 0.0003), respectively (the normality of the distribution was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk test).

Follow-up for up to 7 years showed that only 8 (30%) patients had remission with no clinically significant ED. In the remaining 19 (70%) patients, during the entire follow-up period, manifestations of dysthymia and eating disorders persisted, and NB transformed into hard-to-differentiate atypical forms. In patients with a favorable outcome, there were repeated short-term periods of dysthymia weakening that did not exceed 1–2 months, associated with the achievement of a temporary decrease in body weight, favorable life events, or autochthonous ones, during these periods, RPP also smoothed out. It should be noted that even in patients with the most favorable prognosis, dysmorphophobic ideas were not completely deactivated, and the level of social functioning was reduced compared to healthy peers.

It should be noted that even in patients with the most favorable prognosis, dysmorphophobic ideas were not completely deactivated, and the level of social functioning was reduced compared to healthy peers.

Talk

The data obtained show that NB, which manifests itself in adolescence, is distinguished by a high level of comorbidity with affective spectrum disorders, the latter preceding the development of eating disorders. The most common form of comorbid affective pathology in patients with adolescent NB was dysthymia with episodes of double depression, the second most common form was BAD type II (the development of NB associated with depressive phases of BAD was noted in more than 1/3 of patients), less often NB developed due to psychogenic provoked depression, often followed by mild hypomania, and the least characteristic was the comorbidity of NB with autochthonous recurrent unipolar depression.

Affective disorders in comorbid adolescent NB were characterized by a number of common clinical features: early manifestation, greater severity and long-term persistence of affective symptoms, often persisting throughout the entire follow-up period. Dysthymia was characterized by persistence of negative affect, frequent decompensation and repeated episodes of double depression, bipolar disorder was characterized by a course close to continual, and unipolar recurrent depression was characterized by prolonged depressive phases with short-term incomplete (symptomatic) remissions. The duration of even the most favorable endoform depressions was more than 1 year.

Dysthymia was characterized by persistence of negative affect, frequent decompensation and repeated episodes of double depression, bipolar disorder was characterized by a course close to continual, and unipolar recurrent depression was characterized by prolonged depressive phases with short-term incomplete (symptomatic) remissions. The duration of even the most favorable endoform depressions was more than 1 year.

Attention is drawn to the complex relationship of psychogenic, constitutional and endogenous factors in the development of the disorders under consideration. In many cases, the clinical picture and dynamics of depressions that developed autochthonously against the background of a hereditary-constitutional predisposition and carry all the main features of endogenous hypothymia, at subsequent stages of the dynamics, during the period of active manifestations of NB, are to a greater extent determined by psychogenic influences, reactive experiences of impotence to achieve slimness and inability to lose weight, and improvement and deterioration are often due to favorable or unfavorable psychosocial influences, as well as fluctuations in body weight. At the same time, hypothymic states that are psychogenic at the initial stages, as they progress, often acquire features characteristic of endogenous affective pathology, often with bipolar phenomena.

At the same time, hypothymic states that are psychogenic at the initial stages, as they progress, often acquire features characteristic of endogenous affective pathology, often with bipolar phenomena.

A number of authors [14, 18, 34, 35, 36] noted a significant role of hypothymia in the genesis of RPP. The development of depressive ideas into special pessimistic constructions of dysmorphophobic content with the further formation of an overvalued desire to improve the figure and eating disorders, which we previously identified in some patients with AN and identified as an affective mechanism for the development of the disease [28], was predominant in the case of ND with onset in adolescence.

The close connection with hypothymia, which was noted in the period of NB formation, can also be traced at subsequent stages. In the active phase, the severity of NB and depression are statistically significantly positively correlated, there is a parallelism in the increase and smoothing of their clinical manifestations. Bulimic symptoms and mood disorders seem to “solder together”, forming a wider affective-behavioral symptom complex, and hypothymia supports bulimic symptoms, and the increase in manifestations of NB is a significant factor in deepening depression, forming a pathological vicious circle.

Bulimic symptoms and mood disorders seem to “solder together”, forming a wider affective-behavioral symptom complex, and hypothymia supports bulimic symptoms, and the increase in manifestations of NB is a significant factor in deepening depression, forming a pathological vicious circle.

A clear relationship was also noted between the outcomes of NB and the characteristics of the dynamics of affective pathology: normalization of mood or the development of hypomania contributed to the development of remission of ED. Accordingly, the worst clinical and social outcome was found in patients with long-term persistent hypothymia, within the framework of dysthymia and prolonged unipolar depressions of recurrent depressive disorder, more favorable - with alternation of depressions and hypomanias in the structure of type II bipolar disorder, and the best - with single psychogenically provoked endo-reactive depressions.

Other researchers [12, 30, 37, 38] also obtained data on the simultaneous reduction of bulimic and depressive symptoms during effective pharmaco- and psychotherapeutic interventions, while the positive effect of antidepressants in ND was often explained by their effect on comorbid depression. In recent publications [8, 12, 39, 40], there is a commonality of hereditary factors and pathogenetic mechanisms of ED and affective disorders, and a large role is assigned to disorders of serotonin neurotransmission.

In recent publications [8, 12, 39, 40], there is a commonality of hereditary factors and pathogenetic mechanisms of ED and affective disorders, and a large role is assigned to disorders of serotonin neurotransmission.

The data obtained in our study indicate that timely treatment of depressive and dysthymic conditions plays an important role in achieving remission of adolescent NB. Taking into account the association of hypothymia with psychogenic influences, psychotherapeutic influence and the development of an integrated approach to the treatment of N.B. One of the models of such therapy is developed by Yu.S. Shevchenko and A.A. Severny [41] five-level therapy, including drug, neuropsychological, behavioral, syndromic and social-personal blocks.

In conclusion, it can be noted that the comorbidity of NB with prolonged unipolar recurrent depressions and constitutionally determined chronic mood disorders, as well as the predominance of depressive states over hypomanic ones in the structure of comorbid bipolar disorder, are among the factors of its unfavorable outcome.