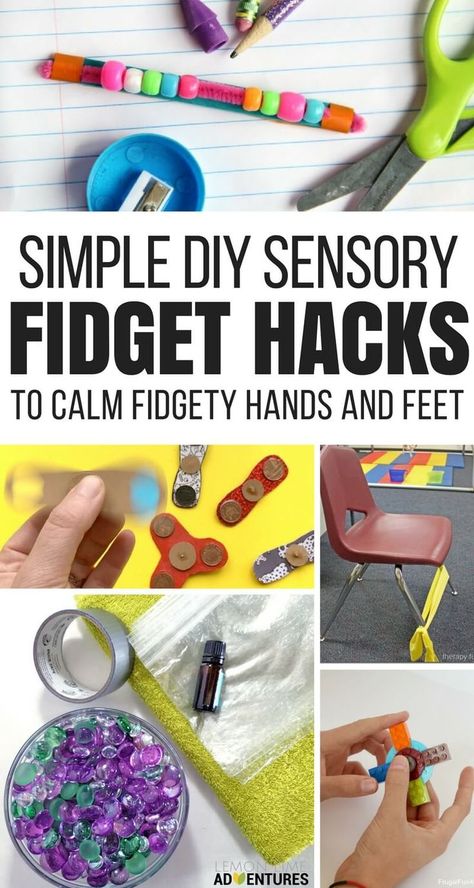

Adhd sensory seeking

Is This ADHD or SPD (Sensory Processing Disorder)?

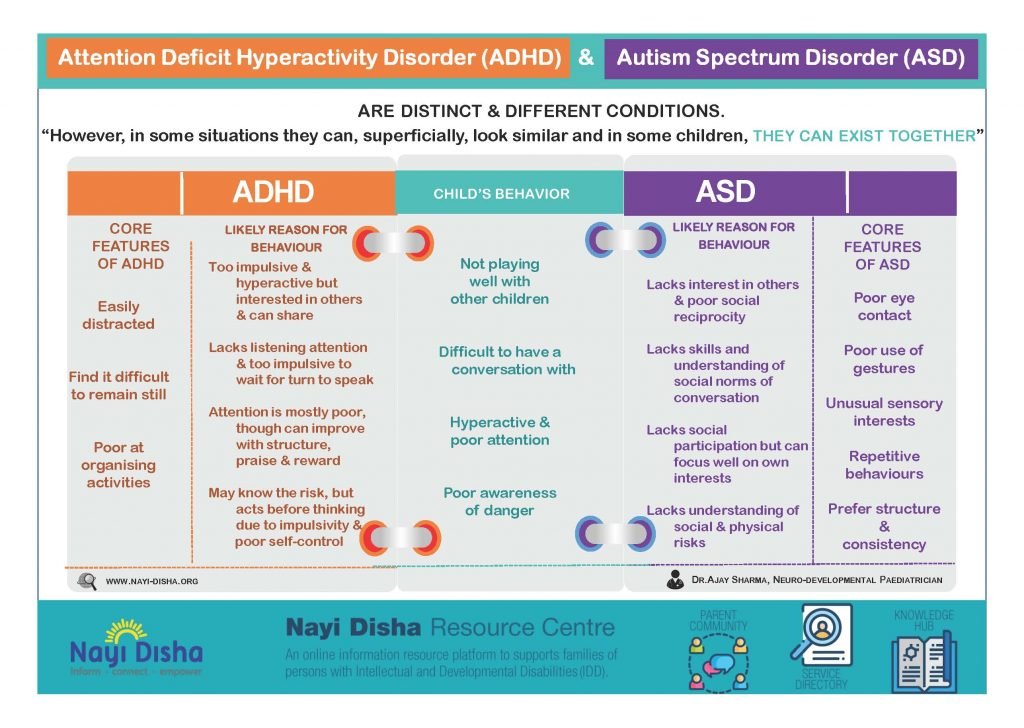

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and sensory processing disorder (SPD) share similarities, but they aren’t the same diagnosis.

Everyone can feel overstimulated at times, especially if you’re in the midst of chaos or you’ve been feeling stressed in other areas of life.

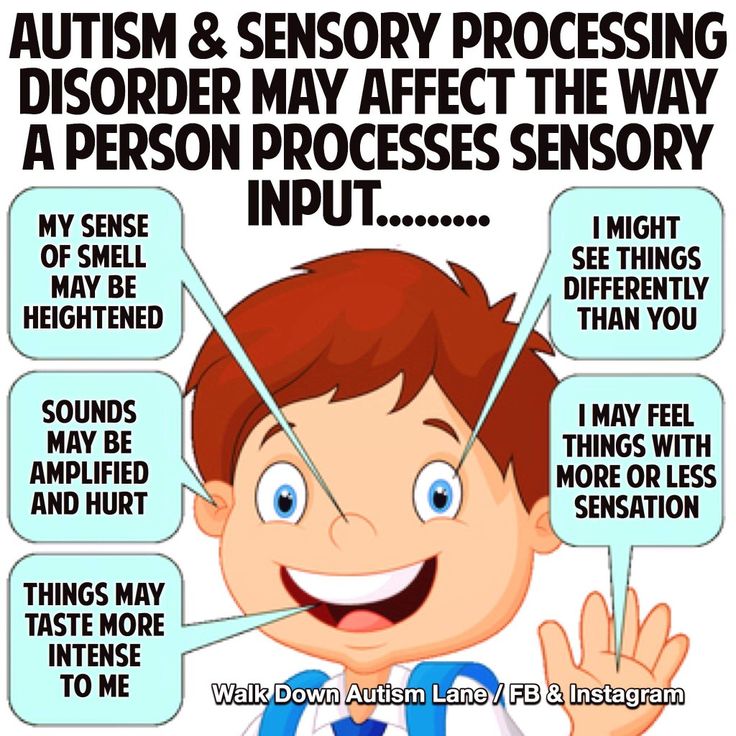

When you live with ADHD or SPD, however, how your brain processes sensory input may make you extra sensitive to certain sensations.

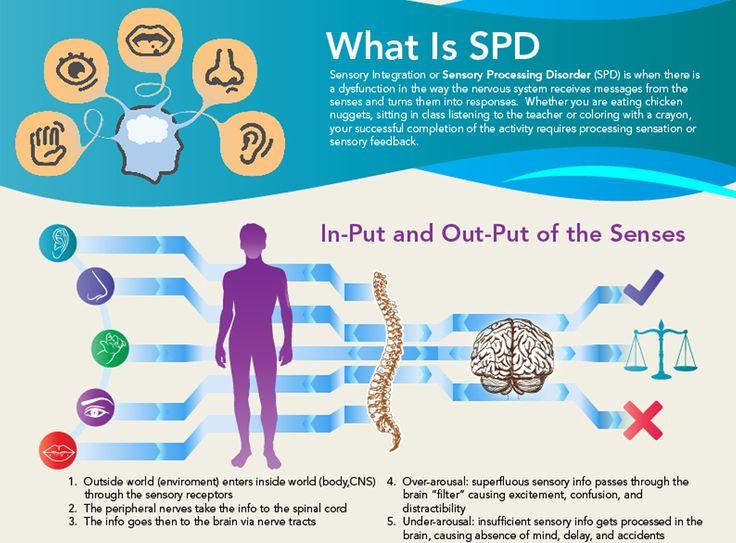

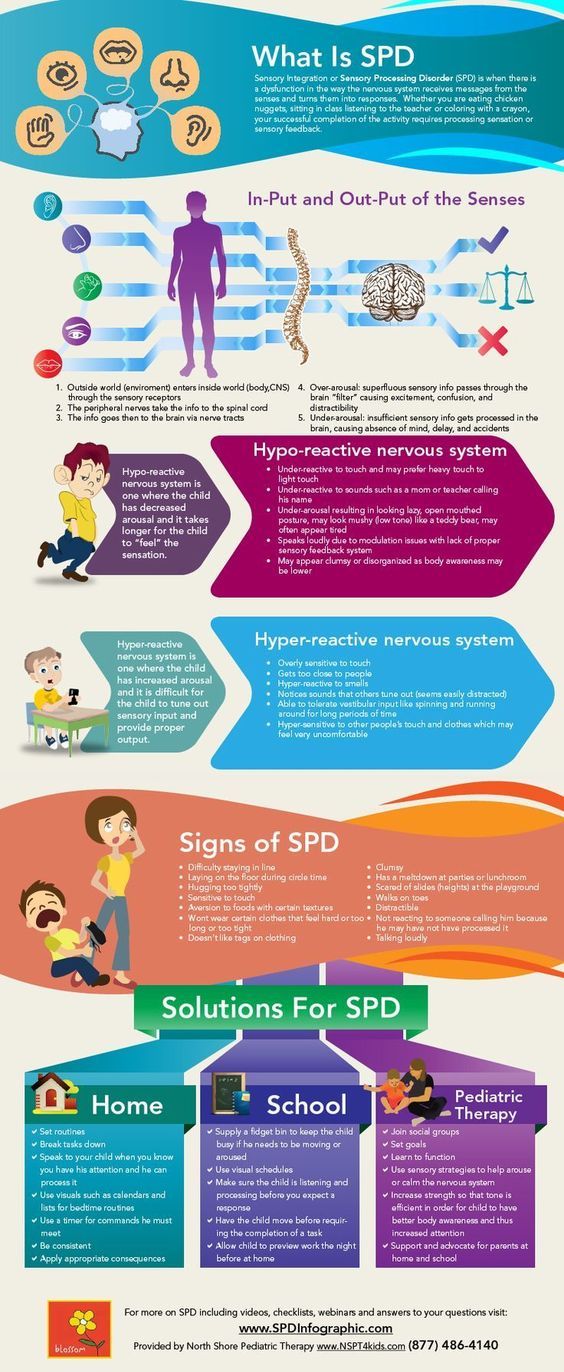

SPD is a brain disorder that affects how you process sensory input.

Sensory input comes primarily from the world around you. The things you see, smell, hear, taste, and feel are all a part of sensory processing.

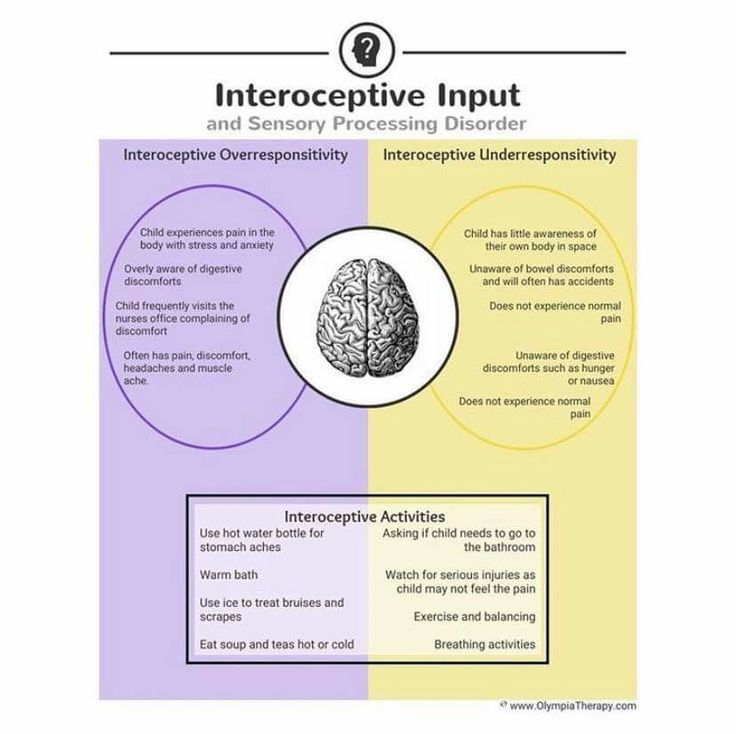

In SPD, you may have heightened sensitivity to certain sensory inputs, but it’s possible to experience the opposite effect. For some people, SPD means having diminished sensitivity.

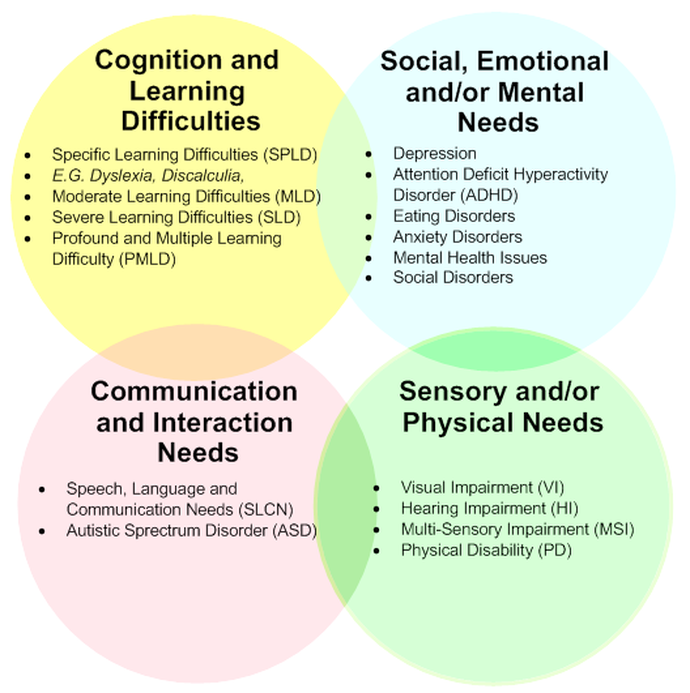

SPD can affect one sensory system in the body — or multiple. You may experience SPD related to any of the eight sensory systems in your body, which are:

- visual

- tactile

- auditory

- smell (olfactory)

- spatial orientation (vestibular)

- taste (gustatory)

- internal sensors like hunger or thirst (interoception)

- muscle and joint movement (proprioception)

Types of sensory processing disorder

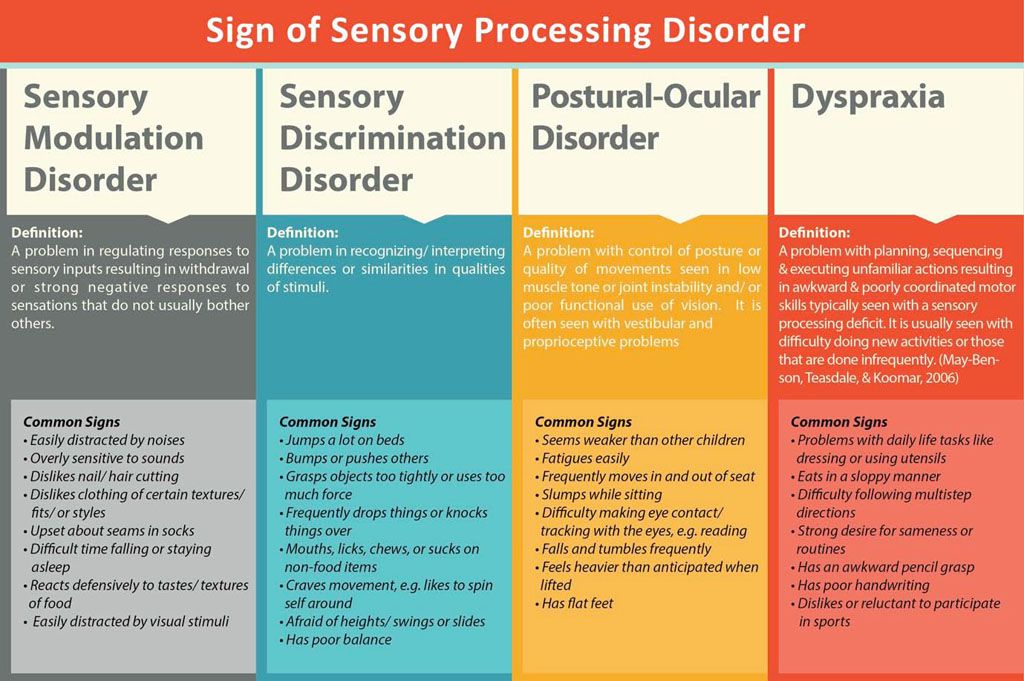

Several types of SPD exist, and within those types are as many as 13 SPD subtypes. The three types of SPD include:

- Sensory modulation disorder

- Over-responsivity sensory modulation, heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli

- Under-responsivity sensory modulation, reduced sensitivity to sensory stimuli

- Sensory craving, an intense desire for sensory stimulation tending to end in disorganized sensory input and unsatisfied sensory craving

- Sensory-based motor disorder

- Postural disorder, altered perception of body position and underdeveloped movement patterns

- Dyspraxia, challenges related to planning and executing movements

- Sensory discrimination disorder (a difficulty interpreting characteristics or subtle qualities related to one or more of the eight sensory systems)

Research from 2021 shows more than half of children living with SPD experience multiple subtypes. Over-responsivity sensory modulation is the most common.

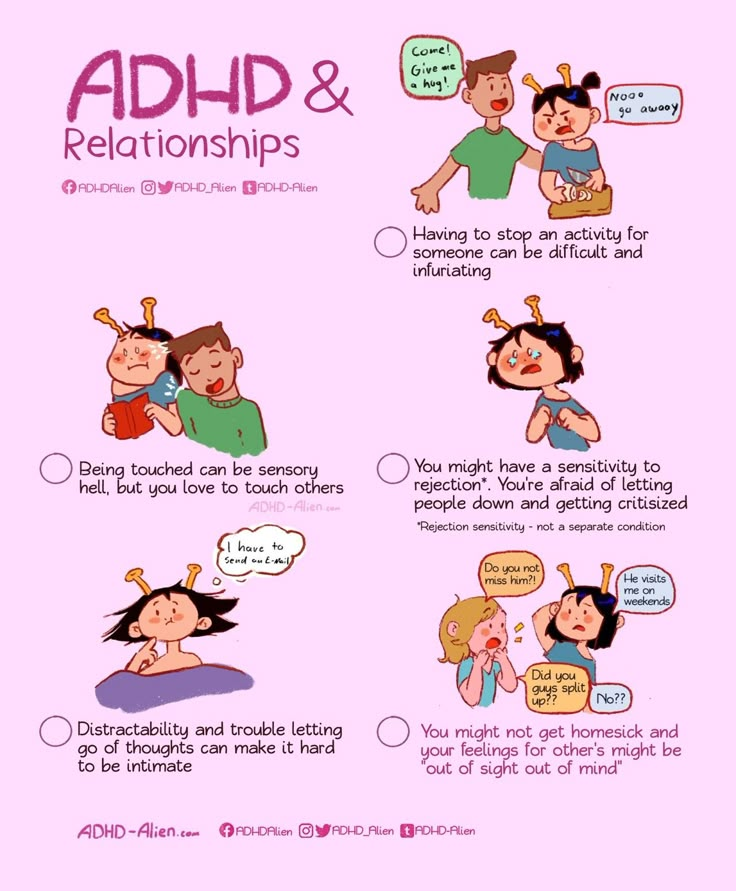

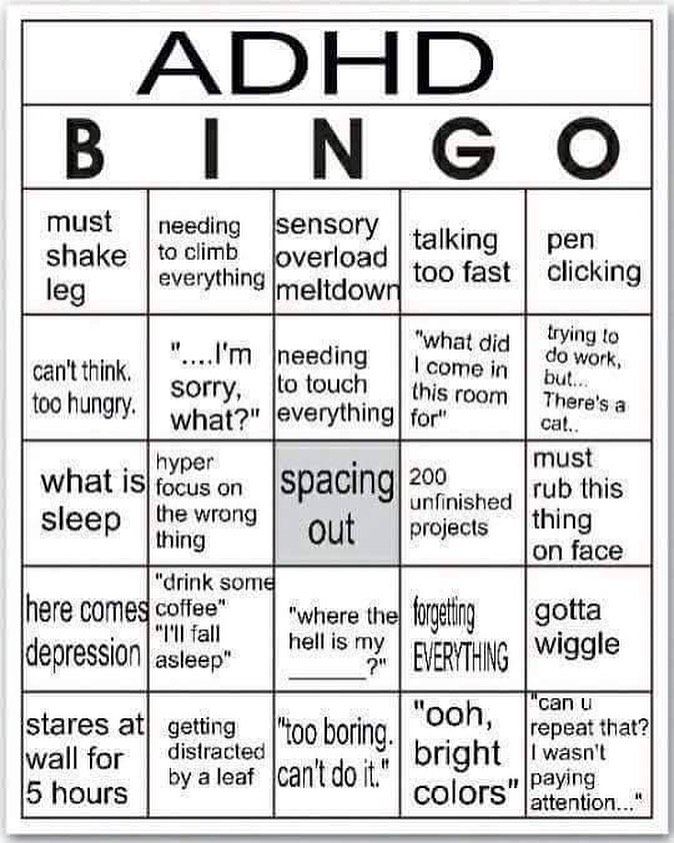

ADHD and SPD can have similar sensory processing symptoms.

In 2010, a review found sensory processing symptoms were more common in ADHD than among children not living with the condition.

What’s more, the review noted ADHD co-occurring with oppositional defiant disorder and anxiety was a predictor of more severe sensory processing challenges.

Both ADHD and SPD often feature challenges with tactile processing and over-responsivity.

They may also share characteristics that appear the same but have different underlying mechanisms.

“ADHD and sensory differences can sometimes look alike,” says Sharon Kaye-O’Connor, a licensed clinical social worker and psychotherapist specializing in ADHD from Manhattan, New York.

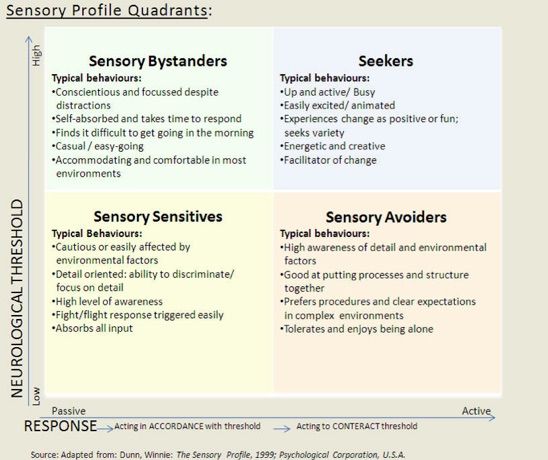

“For example, someone with a need for constant movement might be [experiencing] ADHD, or they may fit the sensory seeking profile of someone with SPD.”

Signs of overstimulation

Overstimulation can present as something different for everyone. Some overt signs could include:

Some overt signs could include:

- visible discomfort to textures or clothing tags (tactile)

- covering ears (auditory)

- shading eyes, perhaps indoors, under fluorescent lighting (visual)

- anxiety driving (vestibular)

- irritation or agitation navigating crowded settings (vestibular)

Other signs might not be so easily recognizable:

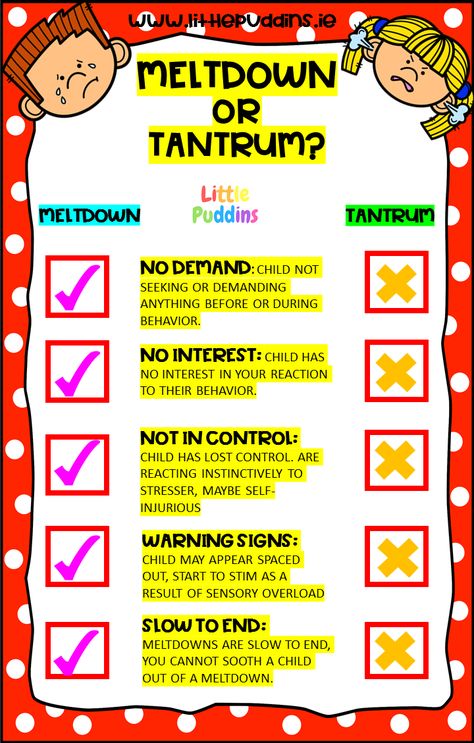

Tantrums or emotional outbursts

Kaye-O’Connor notes both children and adults may experience episodes of increased emotionality. This can present as anything from tears to anger.

Withdrawal

“You may feel a need to withdraw from the environment or shut down to reduce overwhelm,” she says.

Kaye-O’Connor explains that “sensory processing disorder is different from ADHD because SPD is essentially having the trait of sensory differences by itself, while ADHD consists of a more complex constellation of traits.”

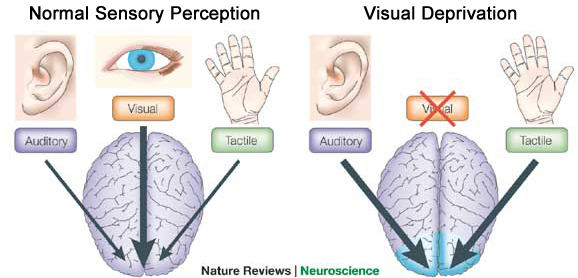

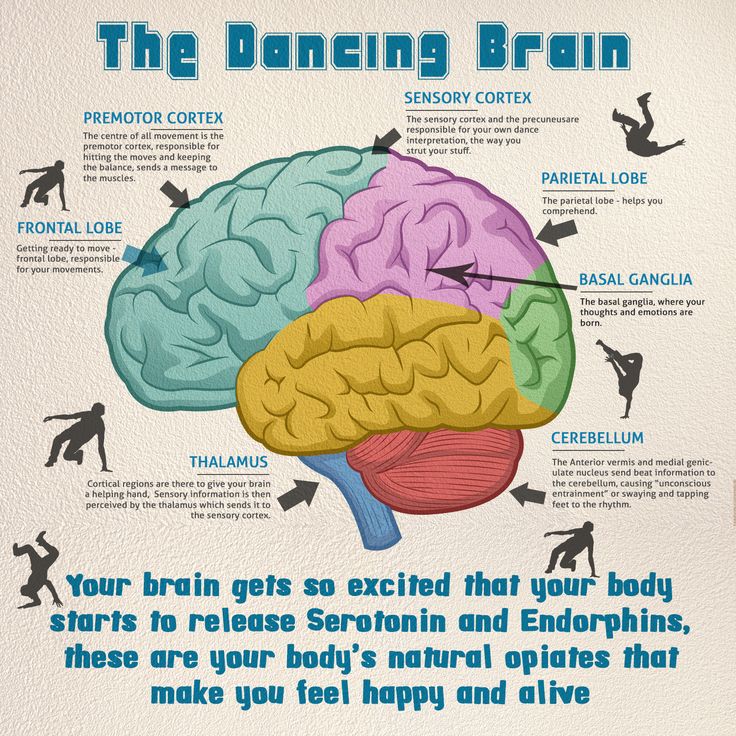

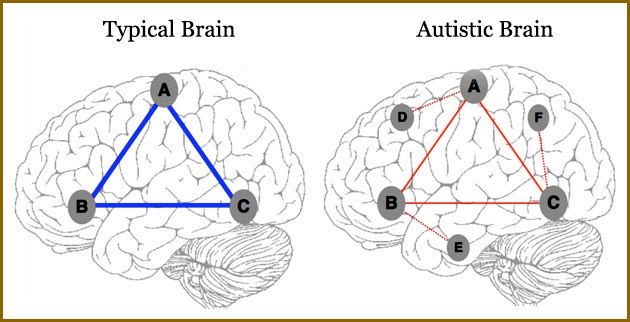

In the brain

In the brain, there are notable differences between ADHD and SPD.

An imaging study from 2016 showed reduced white matter in the brain is associated with SPD. White matter uses electrical impulses to transmit communication between parts of the brain.

When you live with SPD, regions of your brain may not be receiving information correctly or efficiently, resulting in sensory processing challenges.

In ADHD, imaging research from 2018 also showed brain alterations are present; however, these have to do with structural changes in the frontal areas of the brain responsible for executive function.

Evidence from 2019 also suggests that brain chemicals (neurotransmitters) dopamine and norepinephrine play a significant role in ADHD. In contrast, the neurophysiological roots of SPD have not been linked to those neurotransmitters.

Overstimulation

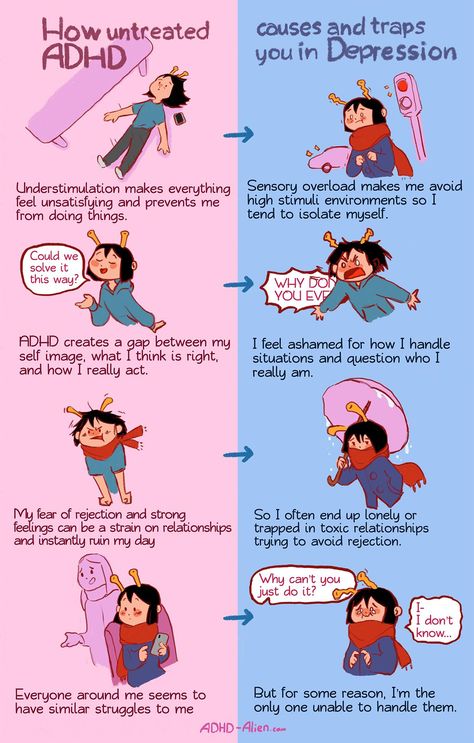

In SPD, overstimulation is exactly that — too much of a sensory input. It can be a source of great anxiety.

In ADHD, what appears as overstimulation may sometimes be an anxiety disorder.

“Many neurodivergent folks are actually diagnosed with anxiety disorders before their neurodivergence

is identified because anxiety and sensory overwhelm can appear so similar,” says Kaye-O’Connor.

“Sensory overwhelm can also lead to anxiety or the feeling of panic.”

As many as 50% of adults living with ADHD also live with an anxiety disorder, according to the Anxiety & Depression Association of America.

Treatments

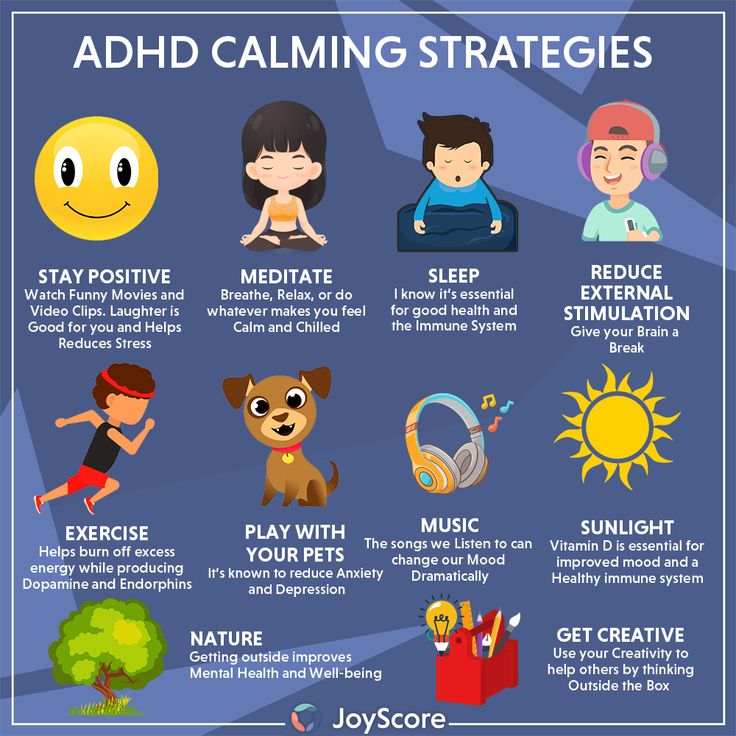

ADHD can often be successfully managed through medication and behavioral therapy aimed at improving executive function skills.

There’s currently no medication that’s recommended for SPD. Treatment focuses on lifestyle changes and therapeutic approaches aimed at retraining the senses.

Sensory seeking in ADHD

Preprint research, meaning it has not been peer-reviewed or published, suggests sensory deficits in ADHD may come from being easily distracted by irrelevant stimuli while also experiencing impairment toward relevant sensory details.

You may be seeking a certain sensory experience, for example, only to find your attention on something else and that sensory experience is never satisfied.

In SPD, on the other hand, you may receive the sensory input you’re looking for only to have it not process correctly in your brain, leaving you wanting more.

ADHD and SPD can have very similar symptoms, both featuring traits related to sensory processing challenges.

In some cases, behaviors seen in ADHD mimic those of SPD but happen for different reasons. Constant movement, for example, may be a trait of hyperactivity in ADHD and a trait related to proprioception in SPD.

It is possible to live with both ADHD and SPD.

Talking with a mental health professional can help you learn which condition may align the most with your symptoms. Having this information can help in creating a treatment plan that best addresses your needs.

3 Types of Sensory Disorders That Look Like ADHD

1 of 16

Mistaking Sensory Disorders for ADHD

I got my start in Sensory Processing Disorder when I was a teacher — some of the kids I was teaching seemed so out-of-sync, and I couldn’t understand why. What was so dreadful about a tambourine being played? Why did some children avoid the jungle gym at all costs, while others could never get off? Why did one child never take his feet off the ground, ever? I wondered if it was ADHD — but the diagnosis didn’t quite fit. When I finally discovered SPD, it opened my eyes to what these children were dealing with.

What was so dreadful about a tambourine being played? Why did some children avoid the jungle gym at all costs, while others could never get off? Why did one child never take his feet off the ground, ever? I wondered if it was ADHD — but the diagnosis didn’t quite fit. When I finally discovered SPD, it opened my eyes to what these children were dealing with.

2 of 16

8 Senses in Disorder

We have at least eight senses. Most people know about the classic five: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching. But many are unaware of the other three:

- The vestibular sense: the “master sense” connected to our inner ear, which tells us where we are, how fast we’re moving, if we’re falling, etc.

- Proprioception: the muscle and joint sense, which helps us know how to get into a coat or how to get up the stairs

- Interoception: internal organs senses that let us know if we’re hungry, thirsty, have to go to the bathroom, etc.

3 of 16

Typical Sensory Processing

Senses serve a number of purposes. First and foremost, they keep us safe — they tell us that a Frisbee is coming toward our head, for example — and we need to duck! Once we’re safe, we can follow up on sensory stimuli, and start to learn. This is called discrimination — we can look at the people playing Frisbee and teach ourselves what they’re doing, so maybe next time we can jump up and catch the Frisbee and start to play.

Next, we use our senses for satisfaction — we identify things that feel good, and we continue to do those things because they bring us joy. Finally, we need our senses for action — we plan out what we’d like to do, then combine our senses together to execute the action.

[Take This Test: Sensory Processing Disorder in Children]

Little boy standing behind the window in sad mood. Sad Teenager looking in the Window and closing his ears with hands. Unhappy child in a plaid shirt. Alone at home. Upset.

Sad Teenager looking in the Window and closing his ears with hands. Unhappy child in a plaid shirt. Alone at home. Upset.4 of 16

How Sensory Disorders Scramble Messages

These tools — reacting, learning, enjoying, and taking action — are used every moment of our lives. Sensory processing disorder (SPD) puts all those everyday functions out of order.

Ordinary sensory experiences — like things we see, feel, and do — are processed in an atypical way when you have SPD. The term “atypical” can mean a lot of things in SPD — perhaps the brain responds late, or perhaps it doesn’t respond at all. Perhaps it responds incorrectly. But ultimately, we don’t respond to our sensory input as we typically should, and that leads to a host of problems.

A child with SPD examines the ground with a magnifying glass.5 of 16

3 Types of Sensory Disorders

SPD is far from a one-size-fits-all disorder. There are three major categories — each with a few subtypes! It’s important to remember that these categories are not mutually exclusive; a highly sensitive child with SPD can have symptoms from more than one category and subtype, which can confuse parents or professionals striving to make an accurate diagnosis.

There are three major categories — each with a few subtypes! It’s important to remember that these categories are not mutually exclusive; a highly sensitive child with SPD can have symptoms from more than one category and subtype, which can confuse parents or professionals striving to make an accurate diagnosis.

A sensory processing disorder, however, should not be confused for sensory processing sensitivity (SPS), a biologically-based trait characterized by increased awareness and sensitivity to the environment. SPS is not associated with dysregulation, but with awareness, depth of processing, and needing time to process information and stimuli.

6 of 16

1. Sensory Modulation Disorder

Sensory modulation is the first category of SPD, with three subtypes of its own. The first is sensory over-responsivity. We call this child the “avoider,” because she goes out of her way to avoid sensory stimulation — by covering her ears, hiding under her desk, or closing her eyes. Her sensory input is too sensitive, and everything seems like too much for her.

Her sensory input is too sensitive, and everything seems like too much for her.

The second subtype is under-responsivity; this child is the “disregarder.” This child won’t notice what’s going on around him — even if it’s extra loud, bright and colorful, or an extreme temperature. His sensory input is muted, so he often seems uncaring or withdrawn. In reality, he just isn’t noticing what’s happening to his senses.

The third subtype is sensory craving; this child is known as the "seeker," or sometimes, the "bumper and crasher." This child wants sensations, as many as possible. She’ll be a daredevil, climbing to the highest branch or swinging the farthest on the tire swing. Her sensory input is never enough, and she always wants more, more, more.

[Take This Test: Is It Sensory Processing Disorder or ADHD?]

7 of 16

2. Sensory Discrimination Difficulties

The second category of SPD is difficulty with sensory discrimination, or using the senses to learn. Let’s call this child the “jumbler.” This child struggles to use his senses to make judgments, so even if he’s done a task many times before, he goes into it blind each time. If he has to pick up a bucket of water every day, for example, he forgets the information he learned the last time he picked something up. He doesn’t use his proprioception to evaluate how much the bucket might weigh, and perhaps he picks it up with too much force and water slops everywhere. Or he may not use enough and can’t get a grip on it.

Let’s call this child the “jumbler.” This child struggles to use his senses to make judgments, so even if he’s done a task many times before, he goes into it blind each time. If he has to pick up a bucket of water every day, for example, he forgets the information he learned the last time he picked something up. He doesn’t use his proprioception to evaluate how much the bucket might weigh, and perhaps he picks it up with too much force and water slops everywhere. Or he may not use enough and can’t get a grip on it.

For children, being the jumbler can be embarrassing. They’re always “messing up” simple tasks, and are often teased by others.

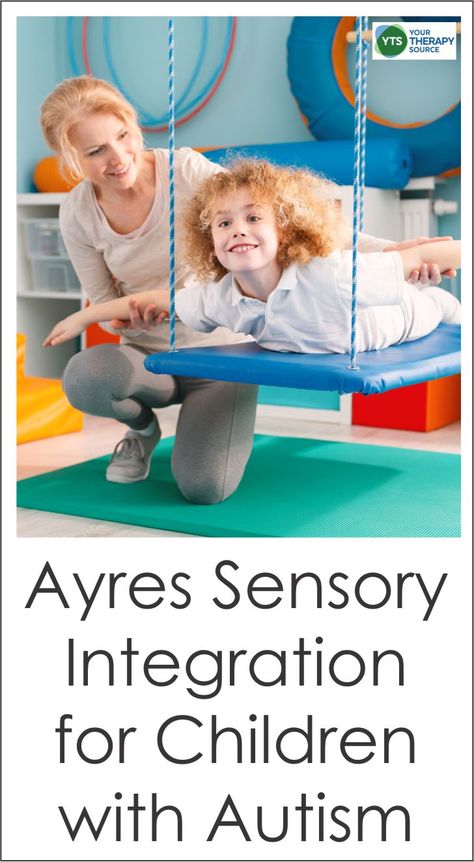

Boy exercising on half balance massage ball with instructor8 of 16

3. Sensory-Based Motor Disorder

The final category of SPD, sensory-based motor disorder, has two subtypes. The first is postural disorder — let’s call this child the “slumper.” The slumper has difficulty with movement, and moves in a clumsy, disorganized way. He may have difficulty stabilizing himself. He may struggle to run without tripping over his feet. Kids with postural disorder have difficulty crossing the midline, or using the hands and feet on one side of the body on the other side.

He may have difficulty stabilizing himself. He may struggle to run without tripping over his feet. Kids with postural disorder have difficulty crossing the midline, or using the hands and feet on one side of the body on the other side.

9 of 16

Dyspraxia

The second subtype is dyspraxia, or the “fumbler.” This child will have difficulty planning and executing actions. If you hand him a box, for example, and ask him to do something with it, he won’t know what to do. A neurotypical child will say, “I can climb in the box. I can go under the box. I can push the box.” The fumbler will struggle to come up with an “action idea.” He’ll prefer toys, games, and situations that are familiar, instead of novel — new situations require new motor planning, and a child with dyspraxia will shy away from that.

A girl with SPD on a swing.10 of 16

Does My Child Have a Sensory Disorder?

Put on your sensory goggles to find out! “Sensory goggles” is a term invented by two SPD moms, Laurie Wienke and Carrie Fannin. Essentially, it encourages parents to look at their child’s behaviors through a sensory point of view, to try to determine if they may be caused by SPD. Ask yourself:

Essentially, it encourages parents to look at their child’s behaviors through a sensory point of view, to try to determine if they may be caused by SPD. Ask yourself:

- Is my child seeking more touch or movement than other children do?

- Is my child avoiding everyday touch and movement?

- Does she have difficulty functioning in certain environments where a lot of senses are used?

If your child expresses some or all of these behaviors, follow up with one more question: What is my child’s self-therapy?

Children with SPD may not know they have a “disorder,” but they instinctively know what situations are difficult for them, and what they can do to seek relief. A child who is a “seeker,” for instance, may stay on the swings for hours, trying to swing higher and higher each time. A child who is an “avoider,” on the other hand, may spend entire days under his comforter on his bed, where he feels safe and unstimulated. If your child engages in unusual behaviors or does certain things significantly more than other children his age, look into SPD.

11 of 16

Symptom Overlap Between SPD and ADHD

Surprisingly, some of the most outwardly obvious symptoms of SPD are inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Sound familiar?

SPD is misdiagnosed as ADHD all the time. So, when faced with common symptoms, parents and doctors need to look at other possibilities — particularly SPD. Why are children inattentive? It could be ADHD, sure. Or it could be a child with SPD, unable to focus because his chair is wobbly — and his vestibular sense is reacting improperly, making him feel like he’s going to be thrown off the face of the earth.

A girl with SPD climbs a chute at the playground.12 of 16

Hyperactivity with Sensory Disorders

Hyperactivity and impulsivity can be symptoms of a sensory disorder as well. A child who can’t sit in his seat may be “seeking” more sensory input, or trying to escape an overwhelming sensation. He may be unconsciously trying to escape from a flickering florescent light, for example, that’s irritating his senses and driving him crazy. Young children, in particular, may not be able to explain why they act the way they do, so it’s important for adults to carefully observe the child’s behaviors — and ask the right questions.

He may be unconsciously trying to escape from a flickering florescent light, for example, that’s irritating his senses and driving him crazy. Young children, in particular, may not be able to explain why they act the way they do, so it’s important for adults to carefully observe the child’s behaviors — and ask the right questions.

13 of 16

How Parents Can Approach Sensory Disorders

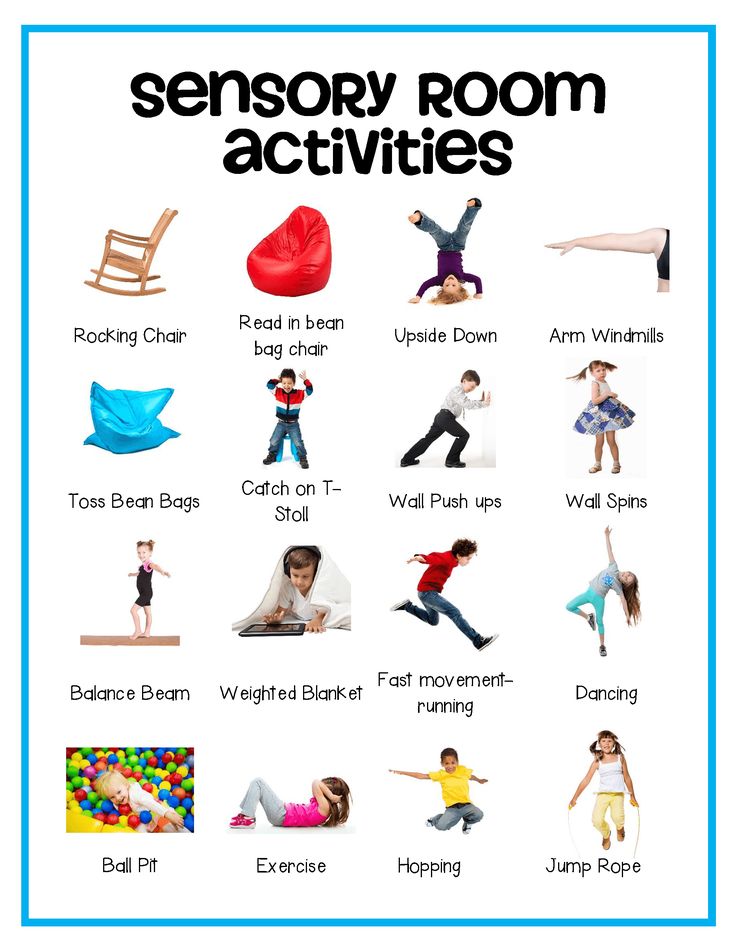

What can you do, as a parent, to help your child with SPD? First, you can get your kids playing vigorously with open-ended fun — outside whenever possible. Outdoor play — without unnecessary rules and restrictions — is key to developing and enhancing a child’s sensory processing. Dr. Jean Ayres, the SPD pioneer, once said, “Fun is the child’s word for sensory integration.” If your child is engaged in using his senses, he’s strengthening his sensory responses and his brain.

With SPD treatment, younger is usually better — young children’s brains are more malleable, and respond well to effective early intervention. But OTSI can be implemented at any age — even for adults! Old dogs may take longer to learn new tricks, but therapy can “bend” the brain of someone with SPD, making it possible for them to function more happily.

But OTSI can be implemented at any age — even for adults! Old dogs may take longer to learn new tricks, but therapy can “bend” the brain of someone with SPD, making it possible for them to function more happily.

14 of 16

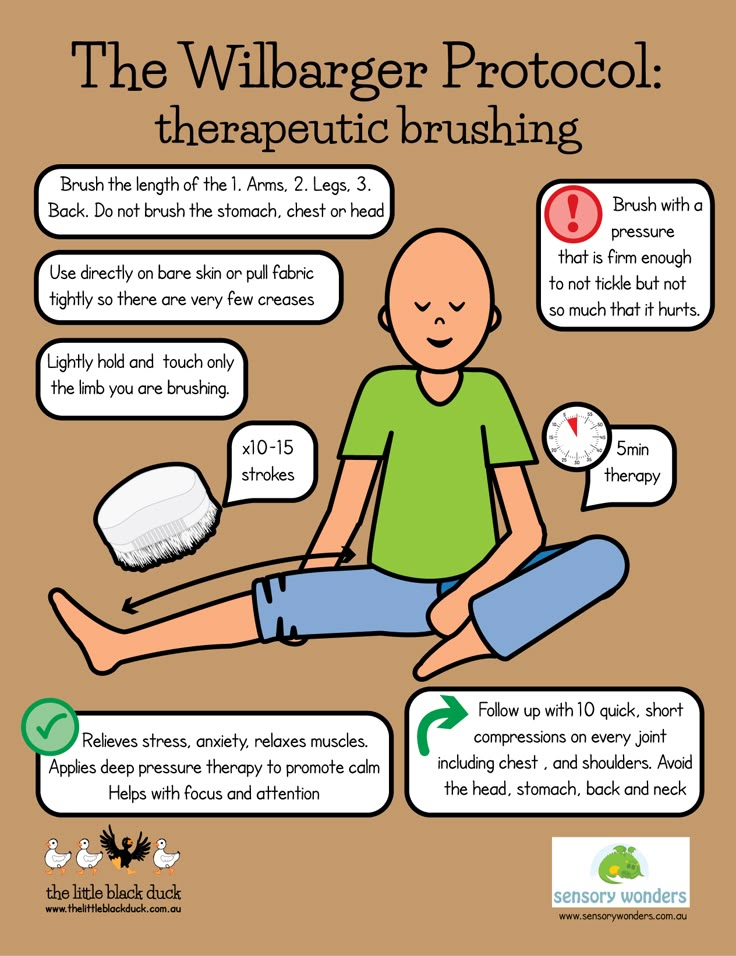

The Power of Touch

The right kind of touch can be very soothing for a child, especially when she’s upset. If your child is having a meltdown, the best course of action may be to embrace her in a strong hug, or have him lay on the couch while you gently press on his back and legs. Teach her how to squeeze her own body when she’s upset — squeezing the forearms, biceps, shoulders, or thighs can deliver calming pressure to an overstimulated child.

A girl has OT to treat her SPD.15 of 16

Treatment with OTSI

The most effective treatment for SPD is occupational therapy, more commonly referred to as OT. The specific type of OT is called OTSI — or occupational therapy using sensory integration techniques.

The specific type of OT is called OTSI — or occupational therapy using sensory integration techniques.

Specific techniques can vary widely from child to child, depending on their particular difficulties, but the overall goal is always the same: to get the brain-body connection working more smoothly. The therapist will try to engage the child in activities that interest her, while speaking to her sensory difficulties. An “avoider” child, for instance, may be presented with fun prizes hidden inside various materials — shaving cream is a common example. He may be hesitant to touch at first, but he’ll eventually become curious for the prize and dig his hands into the shaving cream — strengthening his sensory response and helping him manage his aversion to new textures.

A girl with SPD plays with a sensory table.16 of 16

Think Your Child Has a Sensory Disorder?

Some studies have shown that as many as 40 percent of people with SPD or ADHD will actually have both conditions. This overlap is important for doctors to know, because treatment should be tailored to each child's unique situation. Stimulant medication for ADHD, for example, won’t help a child’s SPD. Occupational therapy, on the other hand, may not fully control ADHD symptoms, but it will most likely benefit the child regardless. My suggestion is to start with OT — if ADHD symptoms remain a problem, revise your treatment strategy to include ADHD-specific interventions.

This overlap is important for doctors to know, because treatment should be tailored to each child's unique situation. Stimulant medication for ADHD, for example, won’t help a child’s SPD. Occupational therapy, on the other hand, may not fully control ADHD symptoms, but it will most likely benefit the child regardless. My suggestion is to start with OT — if ADHD symptoms remain a problem, revise your treatment strategy to include ADHD-specific interventions.

If you suspect that your child may have some sensory issues, don’t hesitate to go for an evaluation. Sometimes, you don’t need a full assessment — just a conversation with a qualified OT may help you solve the puzzle. If you’d like, it’s okay to try a few sessions of OT without a formal diagnosis, just to see how your child responds. Almost every child loves sensory integration techniques, and even those who don’t qualify for a formal SPD diagnosis will most likely benefit from some fun OT sessions.

[Read This: "My Senses Are in Overdrive — All of the Time"]

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

While the causes of ADHD are not fully understood, help for children and adults who suffer from this disorder remains relevant. If we look at the signs of ADHD in detail, we can see a problem that is associated with listening / obedience. This is expressed in the fact that the child shouts out answers to unfinished questions, interrupts the actions of the interlocutor, and monopolizes the conversation.

If we look at the signs of ADHD in detail, we can see a problem that is associated with listening / obedience. This is expressed in the fact that the child shouts out answers to unfinished questions, interrupts the actions of the interlocutor, and monopolizes the conversation.

A child who seeks to assume a clearly dominant position in any situation is a bad listener. First of all, listening requires sufficient mastery of your body and its interaction with the environment. Hand movement, restlessness in one place, inability to wait for one's turn, very easy distractibility - all these indicators indicate that the listening process is not perfect. Our brain will not be focused to work if it has to spend energy on bodily functions that should not be spent on a lot of conscious control.

If you are hypersensitive to sounds, lights, or the smallest environmental stimuli, chances are you will have trouble completing certain tasks, especially when you feel like you are literally being bombarded with information from all directions at once. A good listener first it is required that all functions of the body be synchronized. In fact, productive listening/behavior requires good sensory integration.

A good listener first it is required that all functions of the body be synchronized. In fact, productive listening/behavior requires good sensory integration.

Discussions about ADHD pay very little attention to the lack of sensory integration, which is one of the possible causes of impairment. Anna Jean Ayres, the founder of sensory integration, argued that poor sensory integration leads to hyperactivity and poor attention. She assured that all these problems arise when the vestibular apparatus does not function well.

Properly modulated vestibular action is essential for maintaining a calm and alert state. In addition, the vestibular apparatus helps to keep the level of excitation of the nervous system in balance. An underactive vestibular system contributes to hyperactivity and quick distractibility.

There are two reasons why the vestibular apparatus is unable to integrate sensory information:

1. The vestibular apparatus is overloaded with too much information. To cope with this problem, we must restore the ability to selectively “turn off” some sounds and “switch” to information that is important to us for learning and social skills.

To cope with this problem, we must restore the ability to selectively “turn off” some sounds and “switch” to information that is important to us for learning and social skills.

2. The vestibular apparatus does not receive sufficient stimulation for optimal brain function. In this case, we make up for the lack of stimulation with body movements: if they are children, they are restlessly twitching their arms, jumping up and down on the couch, running down the aisles of the supermarket, despite the fact that those around them do not approve of their behavior. Adults compensate for their energy by running 20 km a day, jumping off a bridge, being constantly on the move and often feeling thirsty due to excitement.

Behavioral changes

Behavioral changes can occur at any age and can be caused by various causes: illness, accident, stress or depression. These changes can begin at different stages of life: perinatal, childhood, adolescence, and even adulthood. This can lead to catastrophic consequences for children of preschool and school age, students and business people in their professional activities.

Symptoms of change in behavior:

✔ The child is more mobile than his peers, he has an attention deficit.

✔ The child started walking late.

✔ The child can only play with interest for a short time.

✔ The child has “bad” hearing and needs to be repeated several times.

✔ It is difficult for a child to concentrate on anything and remember.

✔ The child has speech understanding problems, tone differences. The child has dysgraphia and dyslexia.

✔ The child cannot adapt to the social environment.

✔ The child is not motivated.

✔ The child lacks energy and intrinsic motivation.

✔ The child has poor motor skills, balance and coordination problems.

Success depends on what you hear

For many people, being successful is one of the important goals of life. Each of us defines success in our own way, but many of us want almost the same thing: good performance at school, fulfillment in professional activities, in communication with the outside world. By and large, success lies in the ability to communicate with people. The ability to communicate lies in purposeful listening. In terms of quality, the ability to listen is the most important form of verbal communication.

By and large, success lies in the ability to communicate with people. The ability to communicate lies in purposeful listening. In terms of quality, the ability to listen is the most important form of verbal communication.

Studies have shown that out of total verbal communication time:

✔ 45% listening

✔ 30% speaking

✔ 16% reading

✔ 9% writing

Touch search: razvitie_il — LiveJournal

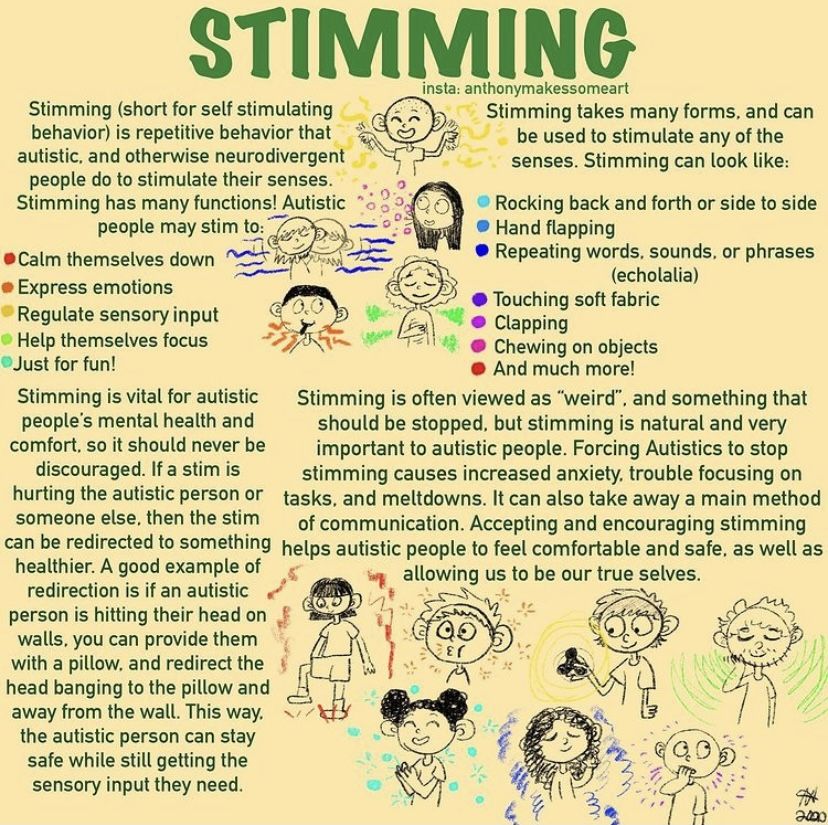

In Hebrew - חיפושThe second profile, rarer. Search not as part of the profile (as in the over-reactivity profile, there is a search in regulatory systems or a search in a system turned off during shutdown). Search as an independent profile . The profile is heavy and difficult for therapy.

(I’ll say right away - I haven’t tested a single child with this profile yet. Everything I write is theory for me).

The child is in a constant active search for stimulation. This is a kind of constant need for stimulation that cannot be satisfied. The search is meaningless - empty, just stimulation, for the sake of stimulation itself. Without any purpose. There is no plan and no result.

The search is meaningless - empty, just stimulation, for the sake of stimulation itself. Without any purpose. There is no plan and no result.

Most of the child's time is devoted to seeking sensory stimulation.

In contrast to the previous profile, where sensory search (in regulatory systems) leads to calming and improvement of the child’s condition, the search here leads to deterioration. search, extreme hyperactivity, causeless laughter, etc.

The search is expressed not only in regulatory systems, but also in others. What is very important - there is a tendency to SPIRAL stimulation, for example: . The quality of its circling is getting worse, in the motor sense. In general, in any search in this profile, the quality worsens the more the more stimulation there is, and there is a helicity effect. It never stops itself, because it cannot. It will be glad if you stop.

Search is VERY active and on all systems!

There is a problem with boundaries - both the body and, well, the soul. Constantly checks the boundaries. He calms down when he understands that the boundaries are given by an adult. These children constantly test the boundaries, and sometimes they are identified as OCD. In adulthood, they like to serve in the army, where there are clear boundaries assigned from above - both ranks and behavior. These children feel bad in a free and flexible framework, because they do not know how to set boundaries for themselves and slide into a search.

Constantly checks the boundaries. He calms down when he understands that the boundaries are given by an adult. These children constantly test the boundaries, and sometimes they are identified as OCD. In adulthood, they like to serve in the army, where there are clear boundaries assigned from above - both ranks and behavior. These children feel bad in a free and flexible framework, because they do not know how to set boundaries for themselves and slide into a search.

What does it look like?

Constantly running, bumping, jumping, playing music or TV too loudly, enjoying excessive, bright, colorful, rapidly changing visual stimulation, they are attracted to strong smells and tastes, they can taste or smell everything.

They will look for stimulating stimulation - any circling, better - head down, hanging head down, strong active proprio-falling, collisions, jumps. Strong, moving visual stimulation, loud noises, strong smells and tastes. In the oral region - chewing, biting, gnawing in the anterior region of the mouth.