What is psychological measurement

Understanding Psychological Measurement – Research Methods in Psychology – 2nd Canadian Edition

Chapter 5: Psychological Measurement

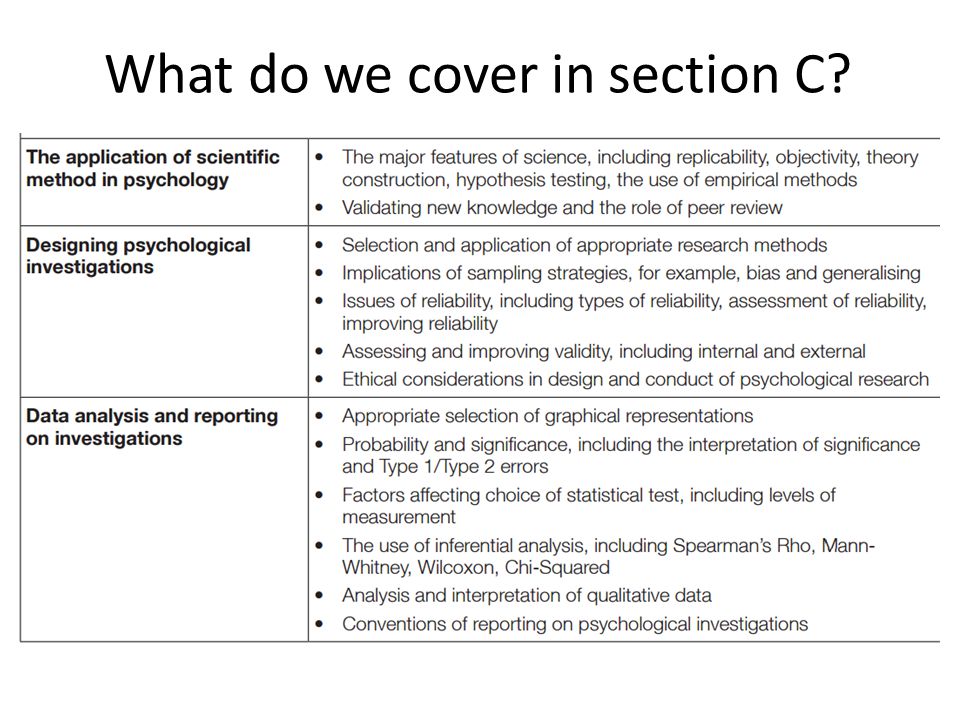

- Define measurement and give several examples of measurement in psychology.

- Explain what a psychological construct is and give several examples.

- Distinguish conceptual from operational definitions, give examples of each, and create simple operational definitions.

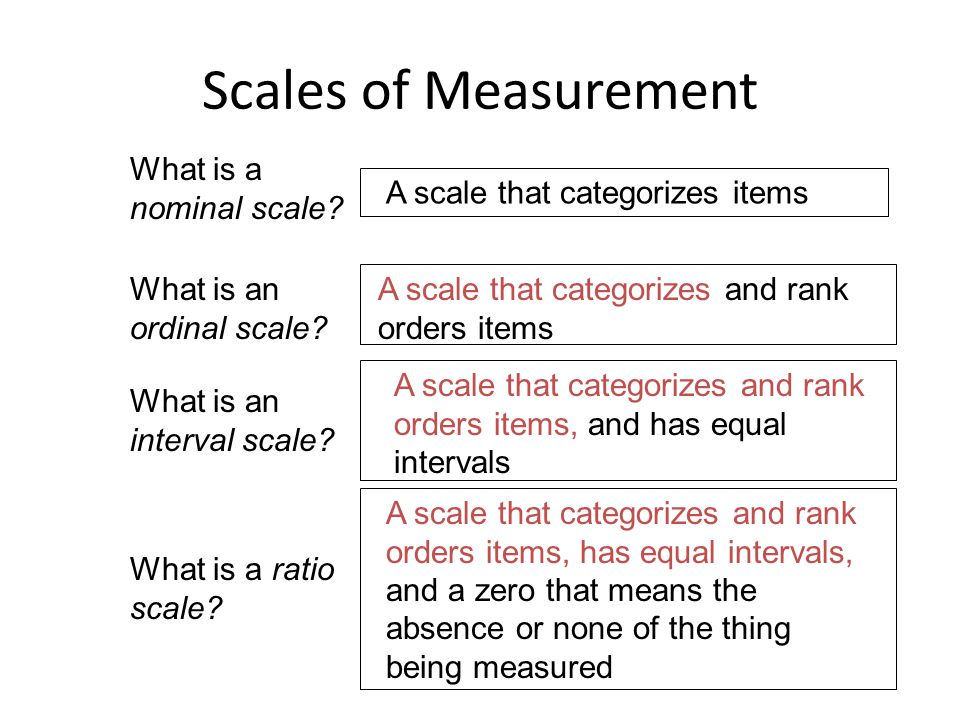

- Distinguish the four levels of measurement, give examples of each, and explain why this distinction is important.

is the assignment of scores to individuals so that the scores represent some characteristic of the individuals. This very general definition is consistent with the kinds of measurement that everyone is familiar with—for example, weighing oneself by stepping onto a bathroom scale, or checking the internal temperature of a roasting turkey by inserting a meat thermometer. It is also consistent with measurement in the other sciences.

In physics, for example, one might measure the potential energy of an object in Earth’s gravitational field by finding its mass and height (which of course requires measuring those variables) and then multiplying them together along with the gravitational acceleration of Earth (9.8 m/s2). The result of this procedure is a score that represents the object’s potential energy.

This general definition of measurement is consistent with measurement in psychology too. (Psychological measurement is often referred to as .) Imagine, for example, that a cognitive psychologist wants to measure a person’s working memory capacity—his or her ability to hold in mind and think about several pieces of information all at the same time. To do this, she might use a backward digit span task, in which she reads a list of two digits to the person and asks him or her to repeat them in reverse order. She then repeats this several times, increasing the length of the list by one digit each time, until the person makes an error. The length of the longest list for which the person responds correctly is the score and represents his or her working memory capacity. Or imagine a clinical psychologist who is interested in how depressed a person is. He administers the Beck Depression Inventory, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire in which the person rates the extent to which he or she has felt sad, lost energy, and experienced other symptoms of depression over the past 2 weeks. The sum of these 21 ratings is the score and represents his or her current level of depression.

The length of the longest list for which the person responds correctly is the score and represents his or her working memory capacity. Or imagine a clinical psychologist who is interested in how depressed a person is. He administers the Beck Depression Inventory, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire in which the person rates the extent to which he or she has felt sad, lost energy, and experienced other symptoms of depression over the past 2 weeks. The sum of these 21 ratings is the score and represents his or her current level of depression.

The important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. It does not require placing individuals or objects on bathroom scales, holding rulers up to them, or inserting thermometers into them. What it does require is some systematic procedure for assigning scores to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest.

Many variables studied by psychologists are straightforward and simple to measure. These include sex, age, height, weight, and birth order. You can often tell whether someone is male or female just by looking. You can ask people how old they are and be reasonably sure that they know and will tell you. Although people might not know or want to tell you how much they weigh, you can have them step onto a bathroom scale. Other variables studied by psychologists—perhaps the majority—are not so straightforward or simple to measure. We cannot accurately assess people’s level of intelligence by looking at them, and we certainly cannot put their self-esteem on a bathroom scale. These kinds of variables are called (pronounced CON-structs) and include personality traits (e.g., extraversion), emotional states (e.g., fear), attitudes (e.g., toward taxes), and abilities (e.g., athleticism).

These include sex, age, height, weight, and birth order. You can often tell whether someone is male or female just by looking. You can ask people how old they are and be reasonably sure that they know and will tell you. Although people might not know or want to tell you how much they weigh, you can have them step onto a bathroom scale. Other variables studied by psychologists—perhaps the majority—are not so straightforward or simple to measure. We cannot accurately assess people’s level of intelligence by looking at them, and we certainly cannot put their self-esteem on a bathroom scale. These kinds of variables are called (pronounced CON-structs) and include personality traits (e.g., extraversion), emotional states (e.g., fear), attitudes (e.g., toward taxes), and abilities (e.g., athleticism).

Psychological constructs cannot be observed directly. One reason is that they often represent tendencies to think, feel, or act in certain ways. For example, to say that a particular university student is highly extraverted does not necessarily mean that she is behaving in an extraverted way right now. In fact, she might be sitting quietly by herself, reading a book. Instead, it means that she has a general tendency to behave in extraverted ways (talking, laughing, etc.) across a variety of situations. Another reason psychological constructs cannot be observed directly is that they often involve internal processes. Fear, for example, involves the activation of certain central and peripheral nervous system structures, along with certain kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours—none of which is necessarily obvious to an outside observer. Notice also that neither extraversion nor fear “reduces to” any particular thought, feeling, act, or physiological structure or process. Instead, each is a kind of summary of a complex set of behaviours and internal processes.

In fact, she might be sitting quietly by herself, reading a book. Instead, it means that she has a general tendency to behave in extraverted ways (talking, laughing, etc.) across a variety of situations. Another reason psychological constructs cannot be observed directly is that they often involve internal processes. Fear, for example, involves the activation of certain central and peripheral nervous system structures, along with certain kinds of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours—none of which is necessarily obvious to an outside observer. Notice also that neither extraversion nor fear “reduces to” any particular thought, feeling, act, or physiological structure or process. Instead, each is a kind of summary of a complex set of behaviours and internal processes.

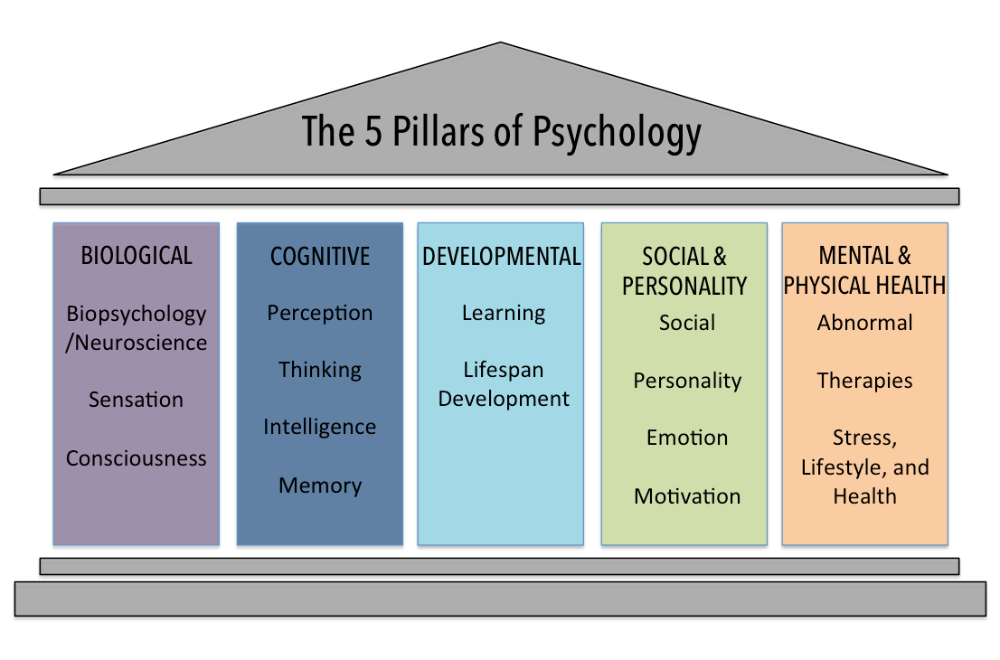

The Big Five is a set of five broad dimensions that capture much of the variation in human personality. Each of the Big Five can even be defined in terms of six more specific constructs called “facets” (Costa & McCrae, 1992)[1].

| Openness to experience | Fantasy | Aesthetics | Feelings | Actions | Ideas | Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conscientiousness | Competence | Order | Dutifulness | Achievement/Striving | Self-discipline | Deliberation |

| Extroversion | Warmth | Gregariousness | Assertiveness | Activity | Excitement seeking | Positive emotions |

| Agreeableness | Trust | Straight-forwardness | Altruism | Compliance | Modesty | Tender mindedness |

| Neuroticism | Worry | Anger | Discouragement | Self-conciousness | Impusivity | Vulnerability |

The of a psychological construct describes the behaviours and internal processes that make up that construct, along with how it relates to other variables. For example, a conceptual definition of neuroticism (another one of the Big Five) would be that it is people’s tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness across a variety of situations. This definition might also include that it has a strong genetic component, remains fairly stable over time, and is positively correlated with the tendency to experience pain and other physical symptoms.

For example, a conceptual definition of neuroticism (another one of the Big Five) would be that it is people’s tendency to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, anger, and sadness across a variety of situations. This definition might also include that it has a strong genetic component, remains fairly stable over time, and is positively correlated with the tendency to experience pain and other physical symptoms.

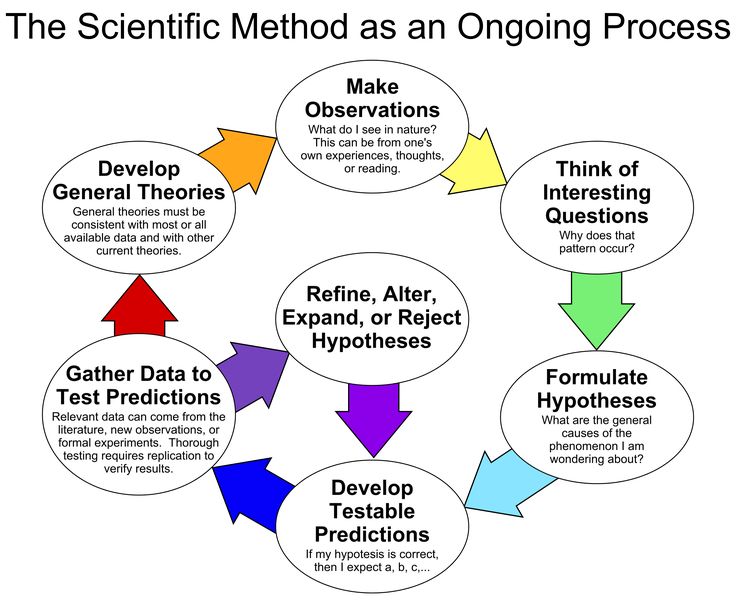

Students sometimes wonder why, when researchers want to understand a construct like self-esteem or neuroticism, they do not simply look it up in the dictionary. One reason is that many scientific constructs do not have counterparts in everyday language (e.g., working memory capacity). More important, researchers are in the business of developing definitions that are more detailed and precise—and that more accurately describe the way the world is—than the informal definitions in the dictionary. As we will see, they do this by proposing conceptual definitions, testing them empirically, and revising them as necessary. Sometimes they throw them out altogether. This is why the research literature often includes different conceptual definitions of the same construct. In some cases, an older conceptual definition has been replaced by a newer one that fits and works better. In others, researchers are still in the process of deciding which of various conceptual definitions is the best.

Sometimes they throw them out altogether. This is why the research literature often includes different conceptual definitions of the same construct. In some cases, an older conceptual definition has been replaced by a newer one that fits and works better. In others, researchers are still in the process of deciding which of various conceptual definitions is the best.

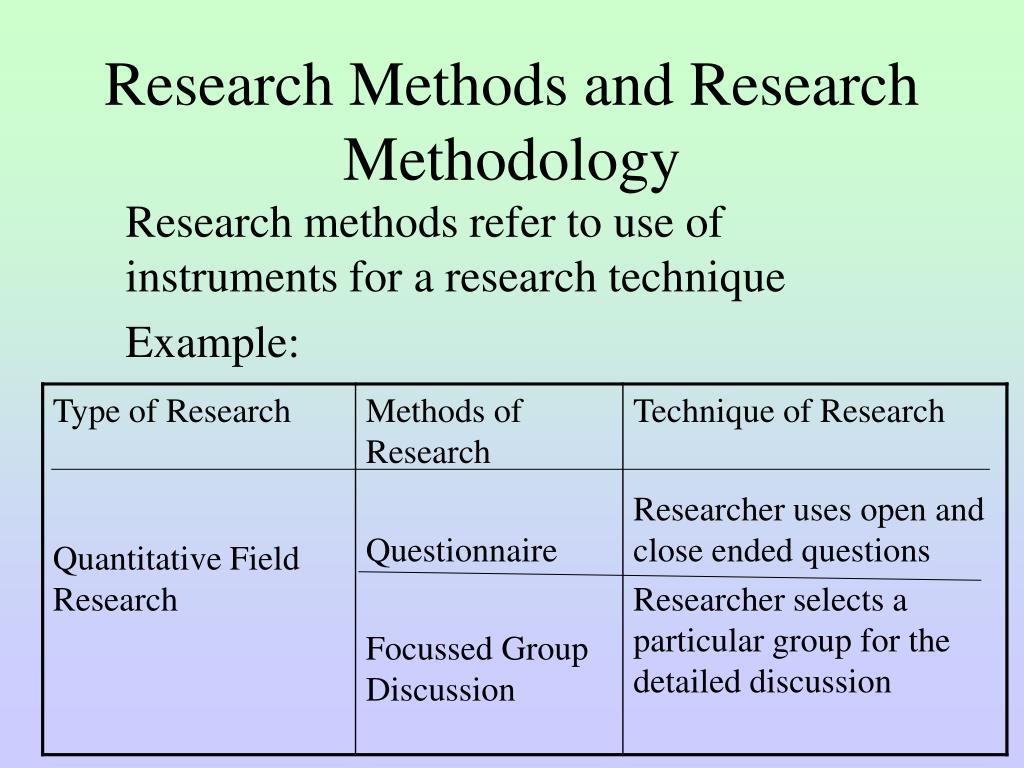

An is a definition of a variable in terms of precisely how it is to be measured. These measures generally fall into one of three broad categories. are those in which participants report on their own thoughts, feelings, and actions, as with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. are those in which some other aspect of participants’ behaviour is observed and recorded. This is an extremely broad category that includes the observation of people’s behaviour both in highly structured laboratory tasks and in more natural settings. A good example of the former would be measuring working memory capacity using the backward digit span task. A good example of the latter is a famous operational definition of physical aggression from researcher Albert Bandura and his colleagues (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961)[2]. They let each of several children play for 20 minutes in a room that contained a clown-shaped punching bag called a Bobo doll. They filmed each child and counted the number of acts of physical aggression he or she committed. These included hitting the doll with a mallet, punching it, and kicking it. Their operational definition, then, was the number of these specifically defined acts that the child committed during the 20-minute period. Finally, physiological measures are those that involve recording any of a wide variety of physiological processes, including heart rate and blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical activity and blood flow in the brain.

A good example of the latter is a famous operational definition of physical aggression from researcher Albert Bandura and his colleagues (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961)[2]. They let each of several children play for 20 minutes in a room that contained a clown-shaped punching bag called a Bobo doll. They filmed each child and counted the number of acts of physical aggression he or she committed. These included hitting the doll with a mallet, punching it, and kicking it. Their operational definition, then, was the number of these specifically defined acts that the child committed during the 20-minute period. Finally, physiological measures are those that involve recording any of a wide variety of physiological processes, including heart rate and blood pressure, galvanic skin response, hormone levels, and electrical activity and blood flow in the brain.

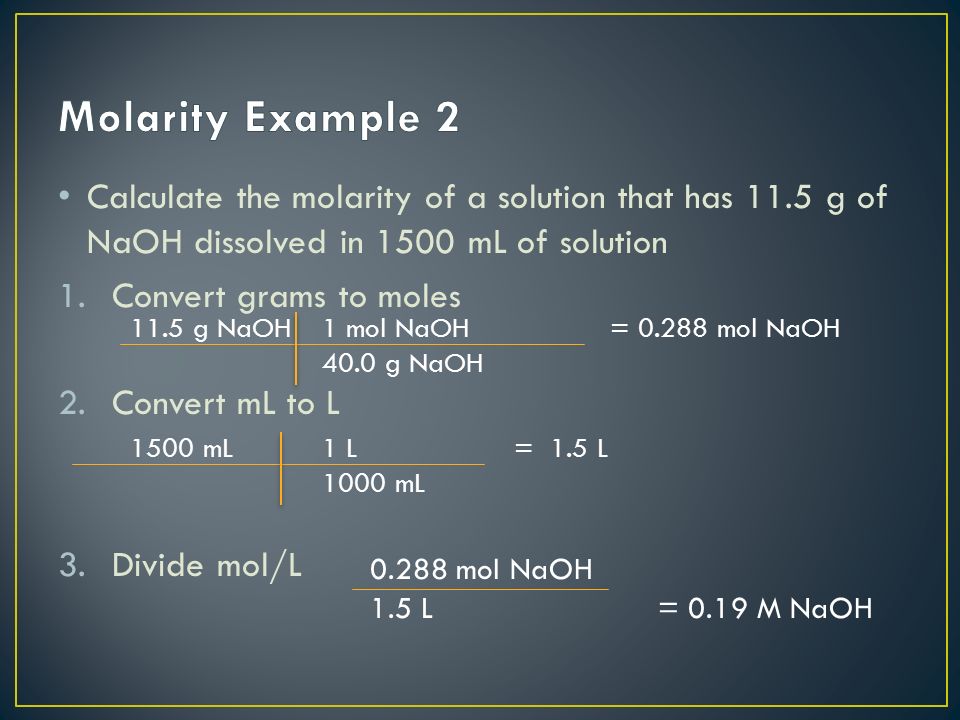

For any given variable or construct, there will be multiple operational definitions. Stress is a good example. A rough conceptual definition is that stress is an adaptive response to a perceived danger or threat that involves physiological, cognitive, affective, and behavioural components. But researchers have operationally defined it in several ways. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale is a self-report questionnaire on which people identify stressful events that they have experienced in the past year and assigns points for each one depending on its severity. For example, a man who has been divorced (73 points), changed jobs (36 points), and had a change in sleeping habits (16 points) in the past year would have a total score of 125. The Daily Hassles and Uplifts Scale is similar but focuses on everyday stressors like misplacing things and being concerned about one’s weight. The Perceived Stress Scale is another self-report measure that focuses on people’s feelings of stress (e.g., “How often have you felt nervous and stressed?”). Researchers have also operationally defined stress in terms of several physiological variables including blood pressure and levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

A rough conceptual definition is that stress is an adaptive response to a perceived danger or threat that involves physiological, cognitive, affective, and behavioural components. But researchers have operationally defined it in several ways. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale is a self-report questionnaire on which people identify stressful events that they have experienced in the past year and assigns points for each one depending on its severity. For example, a man who has been divorced (73 points), changed jobs (36 points), and had a change in sleeping habits (16 points) in the past year would have a total score of 125. The Daily Hassles and Uplifts Scale is similar but focuses on everyday stressors like misplacing things and being concerned about one’s weight. The Perceived Stress Scale is another self-report measure that focuses on people’s feelings of stress (e.g., “How often have you felt nervous and stressed?”). Researchers have also operationally defined stress in terms of several physiological variables including blood pressure and levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

When psychologists use multiple operational definitions of the same construct—either within a study or across studies—they are using . The idea is that the various operational definitions are “converging” or coming together on the same construct. When scores based on several different operational definitions are closely related to each other and produce similar patterns of results, this constitutes good evidence that the construct is being measured effectively and that it is useful. The various measures of stress, for example, are all correlated with each other and have all been shown to be correlated with other variables such as immune system functioning (also measured in a variety of ways) (Segerstrom & Miller, 2004)

[3]. This is what allows researchers eventually to draw useful general conclusions, such as “stress is negatively correlated with immune system functioning,” as opposed to more specific and less useful ones, such as “people’s scores on the Perceived Stress Scale are negatively correlated with their white blood counts. ”

”

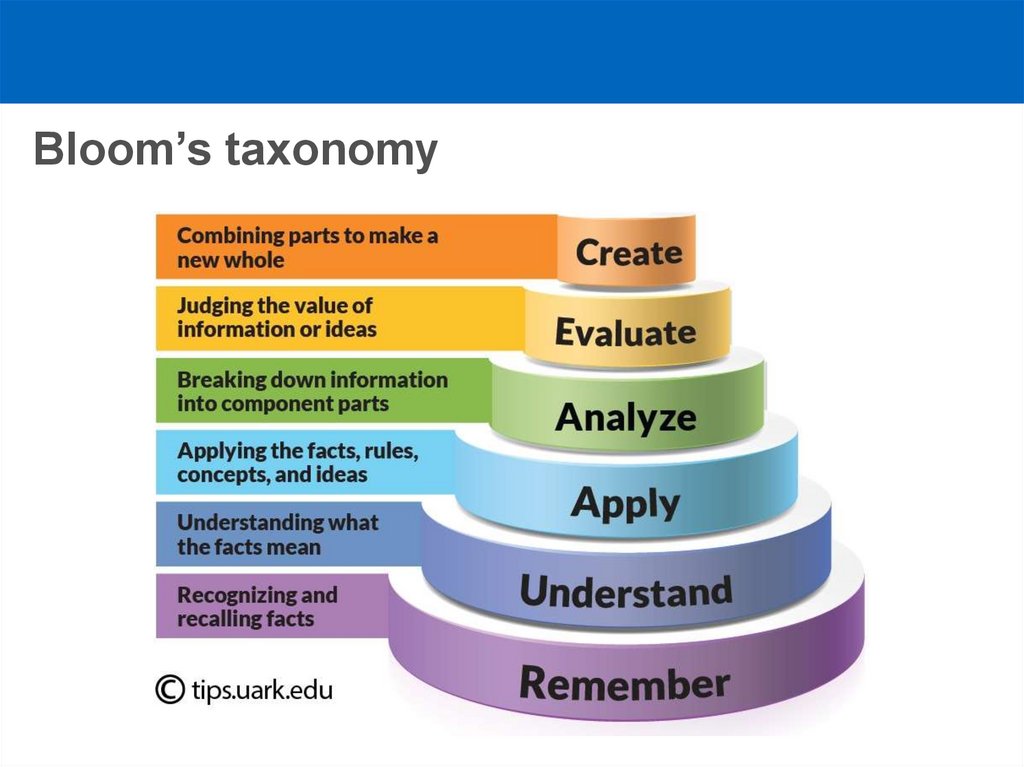

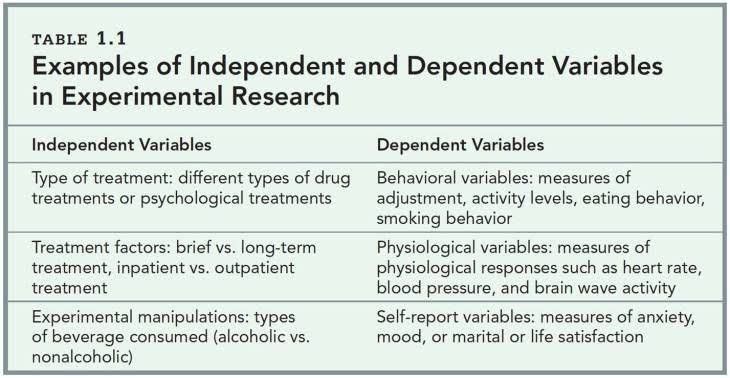

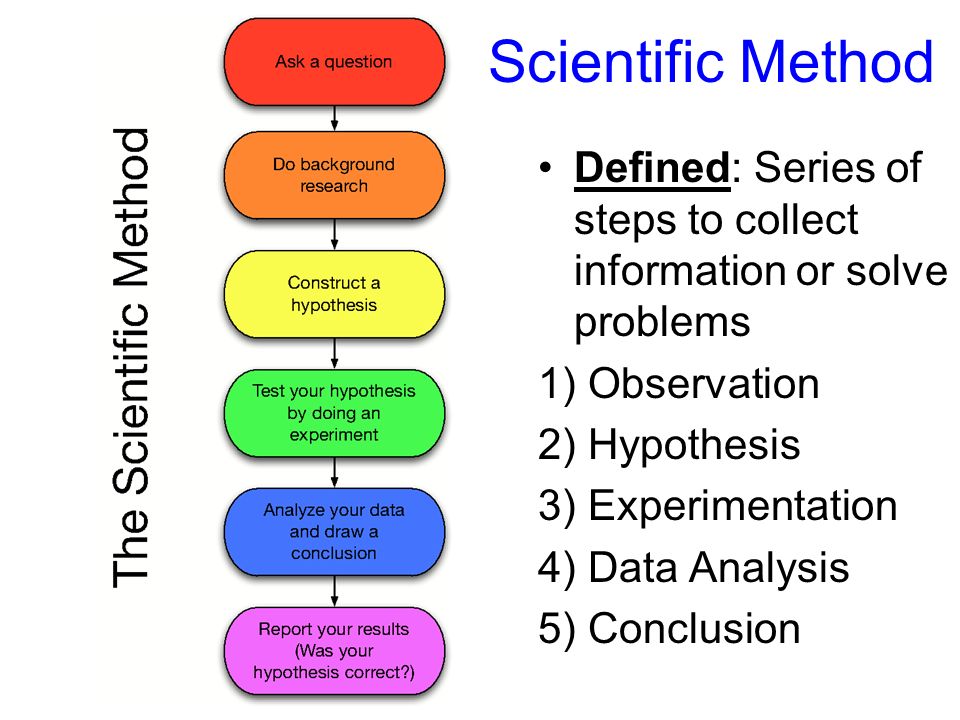

The psychologist S. S. Stevens suggested that scores can be assigned to individuals in a way that communicates more or less quantitative information about the variable of interest (Stevens, 1946)[4]. For example, the officials at a 100-m race could simply rank order the runners as they crossed the finish line (first, second, etc.), or they could time each runner to the nearest tenth of a second using a stopwatch (11.5 s, 12.1 s, etc.). In either case, they would be measuring the runners’ times by systematically assigning scores to represent those times. But while the rank ordering procedure communicates the fact that the second-place runner took longer to finish than the first-place finisher, the stopwatch procedure also communicates how much longer the second-place finisher took. Stevens actually suggested four different (which he called “scales of measurement”) that correspond to four different levels of quantitative information that can be communicated by a set of scores.

The of measurement is used for categorical variables and involves assigning scores that are category labels. Category labels communicate whether any two individuals are the same or different in terms of the variable being measured. For example, if you look at your research participants as they enter the room, decide whether each one is male or female, and type this information into a spreadsheet, you are engaged in nominal-level measurement. Or if you ask your participants to indicate which of several ethnicities they identify themselves with, you are again engaged in nominal-level measurement. The essential point about nominal scales is that they do not imply any ordering among the responses. For example, when classifying people according to their favourite colour, there is no sense in which green is placed “ahead of” blue. Responses are merely categorized. Nominal scales thus embody the lowest level of measurement[5].

The remaining three levels of measurement are used for quantitative variables. The of measurement involves assigning scores so that they represent the rank order of the individuals. Ranks communicate not only whether any two individuals are the same or different in terms of the variable being measured but also whether one individual is higher or lower on that variable. For example, a researcher wishing to measure consumers’ satisfaction with their microwave ovens might ask them to specify their feelings as either “very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” or “very satisfied.” The items in this scale are ordered, ranging from least to most satisfied. This is what distinguishes ordinal from nominal scales. Unlike nominal scales, ordinal scales allow comparisons of the degree to which two individuals rate the variable. For example, our satisfaction ordering makes it meaningful to assert that one person is more satisfied than another with their microwave ovens. Such an assertion reflects the first person’s use of a verbal label that comes later in the list than the label chosen by the second person.

The of measurement involves assigning scores so that they represent the rank order of the individuals. Ranks communicate not only whether any two individuals are the same or different in terms of the variable being measured but also whether one individual is higher or lower on that variable. For example, a researcher wishing to measure consumers’ satisfaction with their microwave ovens might ask them to specify their feelings as either “very dissatisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” “somewhat satisfied,” or “very satisfied.” The items in this scale are ordered, ranging from least to most satisfied. This is what distinguishes ordinal from nominal scales. Unlike nominal scales, ordinal scales allow comparisons of the degree to which two individuals rate the variable. For example, our satisfaction ordering makes it meaningful to assert that one person is more satisfied than another with their microwave ovens. Such an assertion reflects the first person’s use of a verbal label that comes later in the list than the label chosen by the second person.

On the other hand, ordinal scales fail to capture important information that will be present in the other levels of measurement we examine. In particular, the difference between two levels of an ordinal scale cannot be assumed to be the same as the difference between two other levels (just like you cannot assume that the gap between the runners in first and second place is equal to the gap between the runners in second and third place). In our satisfaction scale, for example, the difference between the responses “very dissatisfied” and “somewhat dissatisfied” is probably not equivalent to the difference between “somewhat dissatisfied” and “somewhat satisfied.” Nothing in our measurement procedure allows us to determine whether the two differences reflect the same difference in psychological satisfaction. Statisticians express this point by saying that the differences between adjacent scale values do not necessarily represent equal intervals on the underlying scale giving rise to the measurements. (In our case, the underlying scale is the true feeling of satisfaction, which we are trying to measure.)

(In our case, the underlying scale is the true feeling of satisfaction, which we are trying to measure.)

The of measurement involves assigning scores using numerical scales in which intervals have the same interpretation throughout. As an example, consider either the Fahrenheit or Celsius temperature scales. The difference between 30 degrees and 40 degrees represents the same temperature difference as the difference between 80 degrees and 90 degrees. This is because each 10-degree interval has the same physical meaning (in terms of the kinetic energy of molecules).

Interval scales are not perfect, however. In particular, they do not have a true zero point even if one of the scaled values happens to carry the name “zero.” The Fahrenheit scale illustrates the issue. Zero degrees Fahrenheit does not represent the complete absence of temperature (the absence of any molecular kinetic energy). In reality, the label “zero” is applied to its temperature for quite accidental reasons connected to the history of temperature measurement. Since an interval scale has no true zero point, it does not make sense to compute ratios of temperatures. For example, there is no sense in which the ratio of 40 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit is the same as the ratio of 100 to 50 degrees; no interesting physical property is preserved across the two ratios. After all, if the “zero” label were applied at the temperature that Fahrenheit happens to label as 10 degrees, the two ratios would instead be 30 to 10 and 90 to 40, no longer the same! For this reason, it does not make sense to say that 80 degrees is “twice as hot” as 40 degrees. Such a claim would depend on an arbitrary decision about where to “start” the temperature scale, namely, what temperature to call zero (whereas the claim is intended to make a more fundamental assertion about the underlying physical reality). In psychology, the intelligence quotient (IQ) is often considered to be measured at the interval level.

Since an interval scale has no true zero point, it does not make sense to compute ratios of temperatures. For example, there is no sense in which the ratio of 40 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit is the same as the ratio of 100 to 50 degrees; no interesting physical property is preserved across the two ratios. After all, if the “zero” label were applied at the temperature that Fahrenheit happens to label as 10 degrees, the two ratios would instead be 30 to 10 and 90 to 40, no longer the same! For this reason, it does not make sense to say that 80 degrees is “twice as hot” as 40 degrees. Such a claim would depend on an arbitrary decision about where to “start” the temperature scale, namely, what temperature to call zero (whereas the claim is intended to make a more fundamental assertion about the underlying physical reality). In psychology, the intelligence quotient (IQ) is often considered to be measured at the interval level.

Finally, the of measurement involves assigning scores in such a way that there is a true zero point that represents the complete absence of the quantity. Height measured in metres and weight measured in kilograms are good examples. So are counts of discrete objects or events such as the number of siblings one has or the number of questions a student answers correctly on an exam. You can think of a ratio scale as the three earlier scales rolled up in one. Like a nominal scale, it provides a name or category for each object (the numbers serve as labels). Like an ordinal scale, the objects are ordered (in terms of the ordering of the numbers). Like an interval scale, the same difference at two places on the scale has the same meaning. However, in addition, the same ratio at two places on the scale also carries the same meaning (see Table 5.2).

Height measured in metres and weight measured in kilograms are good examples. So are counts of discrete objects or events such as the number of siblings one has or the number of questions a student answers correctly on an exam. You can think of a ratio scale as the three earlier scales rolled up in one. Like a nominal scale, it provides a name or category for each object (the numbers serve as labels). Like an ordinal scale, the objects are ordered (in terms of the ordering of the numbers). Like an interval scale, the same difference at two places on the scale has the same meaning. However, in addition, the same ratio at two places on the scale also carries the same meaning (see Table 5.2).

The Fahrenheit scale for temperature has an arbitrary zero point and is therefore not a ratio scale. However, zero on the Kelvin scale is absolute zero. This makes the Kelvin scale a ratio scale. For example, if one temperature is twice as high as another as measured on the Kelvin scale, then it has twice the kinetic energy of the other temperature.

Another example of a ratio scale is the amount of money you have in your pocket right now (25 cents, 50 cents, etc.). Money is measured on a ratio scale because, in addition to having the properties of an interval scale, it has a true zero point: if you have zero money, this actually implies the absence of money. Since money has a true zero point, it makes sense to say that someone with 50 cents has twice as much money as someone with 25 cents.

Stevens’s levels of measurement are important for at least two reasons. First, they emphasize the generality of the concept of measurement. Although people do not normally think of categorizing or ranking individuals as measurement, in fact they are as long as they are done so that they represent some characteristic of the individuals. Second, the levels of measurement can serve as a rough guide to the statistical procedures that can be used with the data and the conclusions that can be drawn from them. With nominal-level measurement, for example, the only available measure of central tendency is the mode. Also, ratio-level measurement is the only level that allows meaningful statements about ratios of scores. One cannot say that someone with an IQ of 140 is twice as intelligent as someone with an IQ of 70 because IQ is measured at the interval level, but one can say that someone with six siblings has twice as many as someone with three because number of siblings is measured at the ratio level.

Also, ratio-level measurement is the only level that allows meaningful statements about ratios of scores. One cannot say that someone with an IQ of 140 is twice as intelligent as someone with an IQ of 70 because IQ is measured at the interval level, but one can say that someone with six siblings has twice as many as someone with three because number of siblings is measured at the ratio level.

| Level of Measurement | Category labels | Rank order | Equal intervals | True Zero |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOMINAL | X | |||

| ORDINAL | X | X | ||

| INTERVAL | X | X | X | |

| RATIO | X | X | X | X |

- Measurement is the assignment of scores to individuals so that the scores represent some characteristic of the individuals.

Psychological measurement can be achieved in a wide variety of ways, including self-report, behavioural, and physiological measures.

Psychological measurement can be achieved in a wide variety of ways, including self-report, behavioural, and physiological measures. - Psychological constructs such as intelligence, self-esteem, and depression are variables that are not directly observable because they represent behavioural tendencies or complex patterns of behaviour and internal processes. An important goal of scientific research is to conceptually define psychological constructs in ways that accurately describe them.

- For any conceptual definition of a construct, there will be many different operational definitions or ways of measuring it. The use of multiple operational definitions, or converging operations, is a common strategy in psychological research.

- Variables can be measured at four different levels—nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio—that communicate increasing amounts of quantitative information. The level of measurement affects the kinds of statistics you can use and conclusions you can draw from your data.

- Practice: Complete the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale and compute your overall score.

- Practice: Think of three operational definitions for sexual jealousy, decisiveness, and social anxiety. Consider the possibility of self-report, behavioural, and physiological measures. Be as precise as you can.

- Practice: For each of the following variables, decide which level of measurement is being used.

- An university instructor measures the time it takes her students to finish an exam by looking through the stack of exams at the end. She assigns the one on the bottom a score of 1, the one on top of that a 2, and so on.

- A researcher accesses her participants’ medical records and counts the number of times they have seen a doctor in the past year.

- Participants in a research study are asked whether they are right-handed or left-handed.

- Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory.

Psychological Assessment, 4, 5–13. ↵

Psychological Assessment, 4, 5–13. ↵ - Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63, 575–582. ↵

- Segerstrom, S. E., & Miller, G. E. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 601–630. ↵

- Stevens, S. S. (1946). On the theory of scales of measurement. Science, 103, 677–680. ↵

- Levels of Measurement. Retrieved from http://wikieducator.org/Introduction_to_Research_Methods_In_Psychology/Theories_and_Measurement/Levels_of_Measurement ↵

Psychological tests and measurements | SFU Library

- What are psychological tests?

- Access to psychological tests

- Tests at SFU Library

- Departmental collections

- Administering psychological tests

- Citing psychological tests

If you need help, please contact Yolanda Koscielski, Liaison Librarian for Criminology, Psychology & Philosophy at 778. 782.3315 or [email protected] or Ask a librarian.

782.3315 or [email protected] or Ask a librarian.

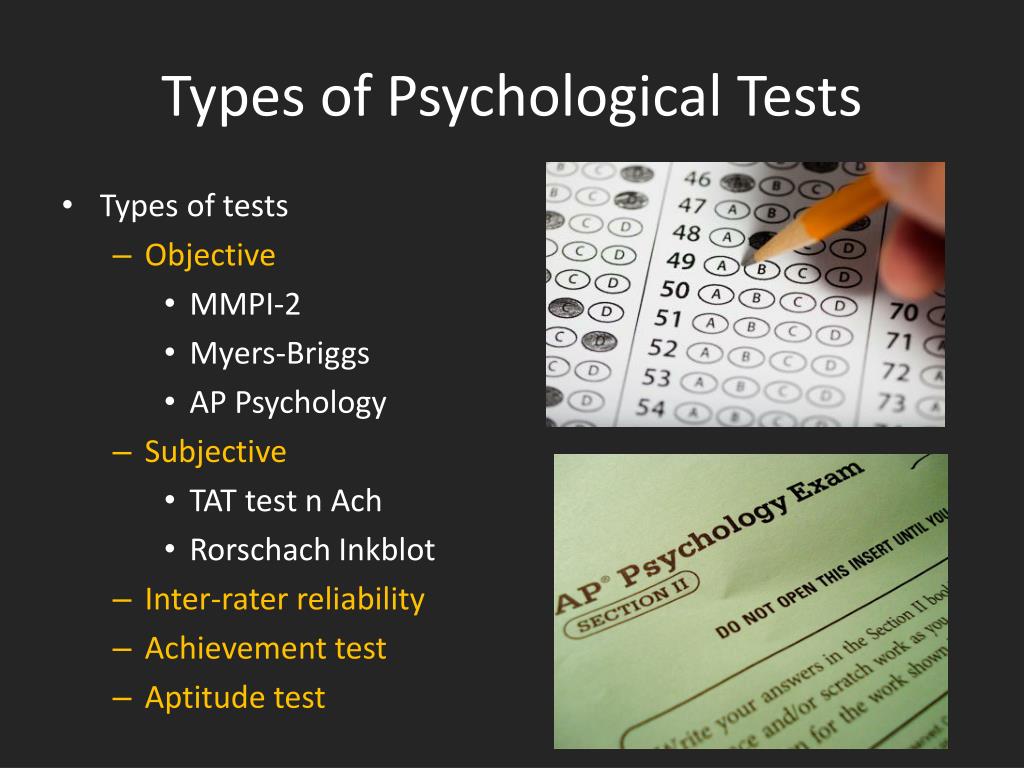

Psychological tests (also known as mental measurements, psychological instruments, psychometric tests, inventories, rating scales) are standardized measures of a particular psychological variable such as personality, intelligence, or emotional functioning. They often consist of a series of questions that subjects rank as true or false, or according to a Likert-type scale (agree, somewhat agree...), however tests can use written, visual or verbal methods.

Many tests are commercially published. One well-known commercial test is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Commercial or published tests may need to be purchased from the publisher, and publishers may require proof that users have the professional credentials to administer the test.

In addition to commercial tests, there are countless unpublished tests that researchers design for particular studies in psychology, education, business and other fields.

Note: The SFU Library does not maintain a print or online collection of standardized tests.

Please note that full access (the measurement + scoring key and/or manual) to most clinical Psychological measures is not available to student researchers. Access to clinical tests is often restricted to Registered Psychologists only (those with a PhD in Psychology), to the clinical Psychology graduate students they supervise, and other professionals in health and counselling fields. Restricting access to tests helps ensure the validity of tests, including their persuasiveness when reported upon in a legal context, and reduces false diagnoses and misapplications by non-professionals.

In addition, there are also often publisher-imposed copyright and licensing restrictions (e.g., prohibitions on reproducing tests) which further restrict access.

Commercial psychological tests/measures require a fee to access them, and some (particularly in Business) may be prohibitively expensive for students. You will also likely require professional credentials to access them. However, library resources provide helpful descriptive and evaluative information about commercial tests.

You will also likely require professional credentials to access them. However, library resources provide helpful descriptive and evaluative information about commercial tests.

Unpublished/non-commercial tests are free to access, but you may require permission from the test creator(s) to use or obtain the test, and access may be restricted, depending on your credentials.

Information about both specific commercial and unpublished and psychological tests is amply available, including journal articles that discuss the application and scoring of a particular test. In many cases, you may be able to track down the test or measure itself of unpublished tests, but without the scoring key or manual. And indeed there still exists a selection of tests with scoring keys that are available to general researchers.

It can be helpful to look at tests (even those without a scoring manual), such as those indexed in PsycTESTS, and reviews of commercially available psychological tests, to see how other researchers have measured a construct. This can inform you own research methods.

This can inform you own research methods.

Search these databases to find:

- Descriptive information and reviews of both commercially published and unpublished tests

- The full text of a unpublished psychological test or measure (usually without the scoring key, with a few exceptions)

PsycTESTS (APA)

PsycTESTS provides information on over 27,000 psychological tests, measures, and other assessment tools. In many cases, the full-text of test instrument is provided. However, scoring materials are rarely provided. PsycTESTS provides information on both commercial and unpublished tests. For non-commercial tests, you may wish to contact the test creator directly to inquire if further information can be provided directly to you. Contact information is often available via PsycTESTS.

Mental Measurements Yearbook with Tests in Print

Mental Measurements Yearbook with Tests in Print (TIP) Tests In Print "serves as a comprehensive bibliography to all known commercially available tests that are currently in print in the English language".

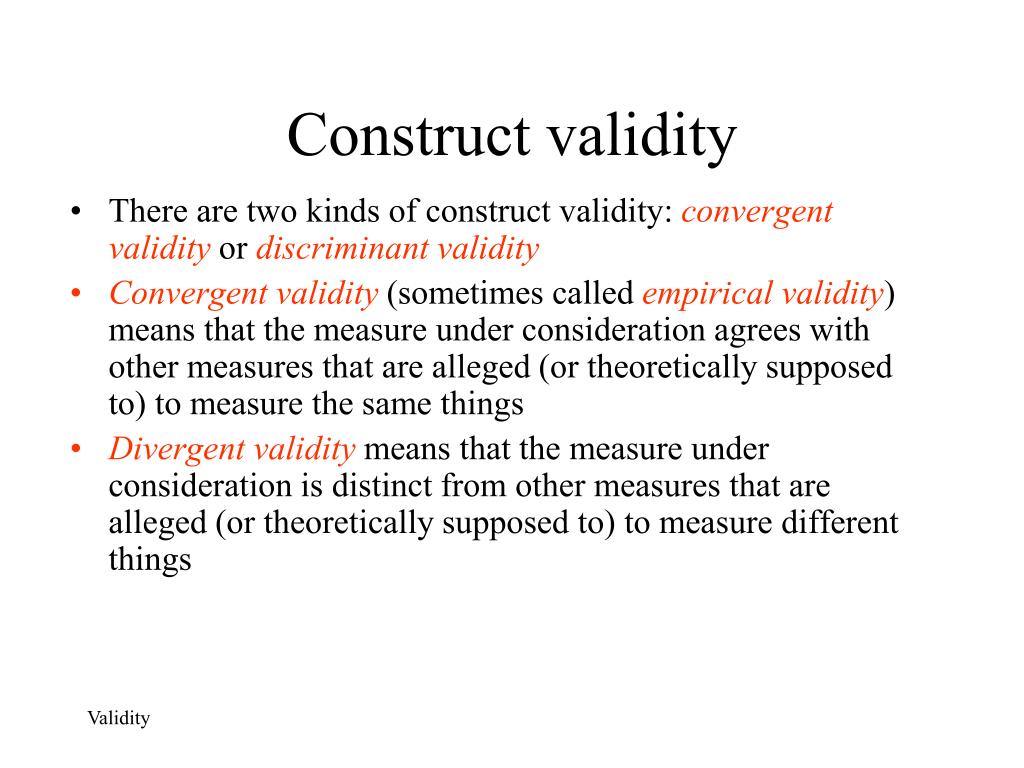

Mental Measurements Yearbook with Tests in Print offers comprehensive details about commercial psychological tests, for example, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and the Strong-Campbell Interest Inventory. The Yearbook also includes information on obtaining a test, as well as insightful reviews about a test, such as its construct validity and reliability.

- Tests in print: Descriptive information on all known commercially available tests in English (also in print)

- Mental measurements yearbook: Descriptive and evaluative information about tests (also in print)

Psychological Test Adaptation and Development

This new open access journal, Psychological Test Adaptation and Development, publishes papers "on adaptations of tests to specific cultural needs, test translations, and the development of existing measures. The journal will focus on the empirical testing of the psychometric quality of these measures".

Health and Psychosocial Instruments

Health and Psychosocial Instruments includes information on measurement instruments (commercial or unpublished) in the health fields, psychosocial sciences, organizational behavior, and library and information science. Links to journal articles that discuss a particular test.

Free tests in journal articles and books

Tests that have been published within books or journal articles are readily available and may meet your research needs. Note that many articles and books provide information about tests, but only some of them may include the actual test instruments.

Journal articles

- PsycINFO: Type "appended" in one of the search boxes and select Tests & Measures from the drop-down menu to the right of the search box. This will narrow your search to articles with tests appended. Use additional search boxes to add keywords.

- ERIC (EBSCO): Type "tests/questionnaires" in one of the search boxes.

and select Publication Type from the drop-down menu to the right of the search box to search for tests. Add keywords via additional search boxes.

and select Publication Type from the drop-down menu to the right of the search box to search for tests. Add keywords via additional search boxes.

Open Access

Open access repositories are a growing resource for accessing test measures, for example:

- Zenodo - e.g., the PsycTEL online community

You might also want to check:

- Medline

Useful MeSH (medical subject headings) include questionnaires, psychological tests, health status rating scales, psychiatric status rating scales, and personality inventory. You can also keyword search, e.g., depression and questionnaire. - CINHAL

Enter an instrument name in the search box and select IN Instrumentation from drop-down menu for articles that used a particular test - ProQuest Dissertations

Tests may be included as appendices to dissertations - Health and psychosocial instruments

Links to journal articles that discuss a particular test (commercial or unpublished). Select Primary Source for citation to the original source for the instrument.

Select Primary Source for citation to the original source for the instrument. - Directory of unpublished experimental mental measures. 8 vols, 1997 (print)

Check index to find journal articles that describe tests of a particular variable, actual test may or may not be included in article.

For more detailed information on identifying tests on specific subjects see the American Psychological Association's guide: Testing and Assessment.

Books

Some examples of SFU Library books that include tests

- Marketing scales handbook: a compilation of multi-item measures for consumer behavior & advertising research. Volume 5, 2009

Includes many examples of tests about consumer behaviour - Measuring health: A guide to rating scales and questionnaires, 2006

Some tests included - Handbook of research design and social measurement, 2002

Some tests included - Handbook of Psychiatric Measures, 2008 [print and CD-ROM]

Sample items provided for most measures, many actual measures included in CD ROM - Communication research measures: a sourcebook, 1994 edition [print], and 2009 edition [print)

Descriptive summaries of measures, most measures also provided - Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes, 1991 [print]

Contains many tests related to personality, self-esteem, and other social attitudes - Essentials of Psychological Assessment Series, 1999 - [various titles, print and online]

Search for this title in the Catalogue's Browse Search to view full series. Some tests may be included

Some tests may be included

Note: There is no straightforward way to identify books in the Library Catalogue that include tests, but a subject search for either Psychological Tests or Psychological Testing is a good start.

University of British Columbia holds a collection of standardized tests at the Psychoeducational Research and Training Centre (PRTC) within the Faculty of Education. Members of the SFU community can use this collection under some circumstances, but it is advisable to call first (604) 822-5384.

Many online and print books are available at SFU Library to give you background information on using tests and measures. Below are just a few examples:

- Sage research methods online Includes over 600 books

- An introduction to Psychological Tests and Scales, 2021

- Measurement models for psychological attributes, 2021 [print]

- Handbook of Psychological Assessment, 2016

- Tests: a comprehensive reference for assessments in psychology, education, and business, 2008 (print)

- Comprehensive handbook of psychological assessment, 2004 (print, Vols 1-4)

- Encyclopedia of social measurement, 2005

- Dictionary of psychological testing, assessment and treatment, 2007

- The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment, 2004 (print)

The APA blog outlines the format for citing a Psychological test or measure. APA prescribes the general APA syntax for citing a test or measure:

APA prescribes the general APA syntax for citing a test or measure:

Who (Author) - When (Date) - What (Title) [format note] - Where (Place)

A distinction on whether you are citing the database record for a test, or the test itself is made by writing [Database record] or [Measurement instrument] in square brackets after the test's title.

Note that older citations for print tests (pre-internet) can look exactly like the citation for a book. This can be confusing when tracking down citations. If unclear, you can trying search PsycTESTS or WorldCat to elicit more information.

Owned by: Yolanda Koscielski

Last revised: 2021-11-02

Measurements in psychology | Psylist.net

Dictionaries ↓

A B C D E F G I K L M N O P R S T U V W Y Z

Measurements in psychology are procedures for obtaining numerical characteristics for the properties of phenomena studied in psychology, for example. motor and speech reactions, sensations, abilities, motives, attitudes and actions of the individual, his status in the group.

motor and speech reactions, sensations, abilities, motives, attitudes and actions of the individual, his status in the group.

Various types of measurement are theoretically formalized using the concepts of numerical representation and scale. Numeric representation is a function that homomorphically maps an empirical relational system to a relational number system. The scale is a set of numbers, the relationships between which reflect the relationships between the objects of the empirical system. Scales are classified by type according to which relationships they reflect and, equivalently, to those admissible (mathematical) transformations that leave the corresponding relationships invariant. The typology of scales is complex and limitless. The simple typology proposed by the American psychologist and psychophysicist S. Stevens is widely known (1946). ratio scale, interval, ordinal and nominal scales.

The nominal scale (or name scale) displays only an equivalence relation, by which objects are grouped into separate non-overlapping classes, and the class number actually has no quantitative content and can be replaced by a name, cipher, etc. An example of this kind of scale is the numbering of players in sports teams.

An example of this kind of scale is the numbering of players in sports teams.

Ordinal (or ranked) scale displays, in addition to the equivalence relation, also the order relation; any monotonic transformation will be admissible for it. Examples: school performance scores, mineral hardness scale (Moss scale).

Interval scale , in addition to the ratios specified for the scales of names and order, displays the ratio of distances (differences) between pairs of objects. A positive linear transformation is admissible for it. The Celsius and Fahrenheit scales, which measure physical temperature, are examples of boarding scales. In psychology, these scales include measurement scales for various subjective phenomena obtained by pairwise comparison.

Ratio scale (proportional scale) only allows scale values to be multiplied by a constant (similarity transformation). In physics, this type of scale is satisfied by many measurement procedures, e. g. masses in kilograms, lengths in meters, temperatures in degrees Kelvin.

g. masses in kilograms, lengths in meters, temperatures in degrees Kelvin.

Of the other types, we note the absolute scale , which allows only identical transformations and displays the number of indivisible and homogeneous objects, for example. the number of inhabitants of the city N, the number of teeth, the amount of short-term memory, etc.

The problem of the adequacy (correctness) of methods for mathematical processing of measurement results is directly related to the question of the type of scale. In the general case, adequate statistics are those that are invariant under the admissible transformations of the measurement scale used.

Experimental psychology was born out of not just a laboratory experiment, but an experiment involving measurements (intensity of sensations, reaction time, memory capacity, etc.). At first, psychologists sought to create procedures and measurement scales comparable in type to proportional measurements generally accepted in the natural sciences. However, the real expansion of the methods of psychological measurement occurred to a greater extent not at the expense of methods of the highest standard, and this gave cause for concern. Some relief was brought by an unconventional interpretation of measurement “as the assignment of numbers to objects or events according to the rules” (S. Stephens). In fact, it turned out that in psychology it is incomparably easier to find methods for ascribing numbers than to determine the rules for this activity. Measuring procedures for psychic phenomena are no better known than what they measure. As W. Thorgerson frankly remarked (1958), most measurements in the social and behavioral sciences are based on the conventions and intuitions of experimenters. From the recognition of this fact, it does not in any way follow the need to abandon existing measurement methods (as well as methods for processing initial data), since their value is determined not only by the expected accuracy and level of measurement (scale type), but by the ability to predict other observable facts, in including and purely practical.

However, the real expansion of the methods of psychological measurement occurred to a greater extent not at the expense of methods of the highest standard, and this gave cause for concern. Some relief was brought by an unconventional interpretation of measurement “as the assignment of numbers to objects or events according to the rules” (S. Stephens). In fact, it turned out that in psychology it is incomparably easier to find methods for ascribing numbers than to determine the rules for this activity. Measuring procedures for psychic phenomena are no better known than what they measure. As W. Thorgerson frankly remarked (1958), most measurements in the social and behavioral sciences are based on the conventions and intuitions of experimenters. From the recognition of this fact, it does not in any way follow the need to abandon existing measurement methods (as well as methods for processing initial data), since their value is determined not only by the expected accuracy and level of measurement (scale type), but by the ability to predict other observable facts, in including and purely practical. Nevertheless, this recognition is necessary in order to avoid naive mistakes.

Nevertheless, this recognition is necessary in order to avoid naive mistakes.

Similar items in the Dictionaries section:

- Disharmonious Barre syndrome

- Empathy

- Attention violations

- Psychophysiology of local brain lesions

- Association

- Masturbation

- Electromyography

- Psychophysiology

- Live movement

- Time allocation method

| Psychodiagnostics. Psychological research. Psychological dimension. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lectures and workshop on psychology - Psychodiagnostics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

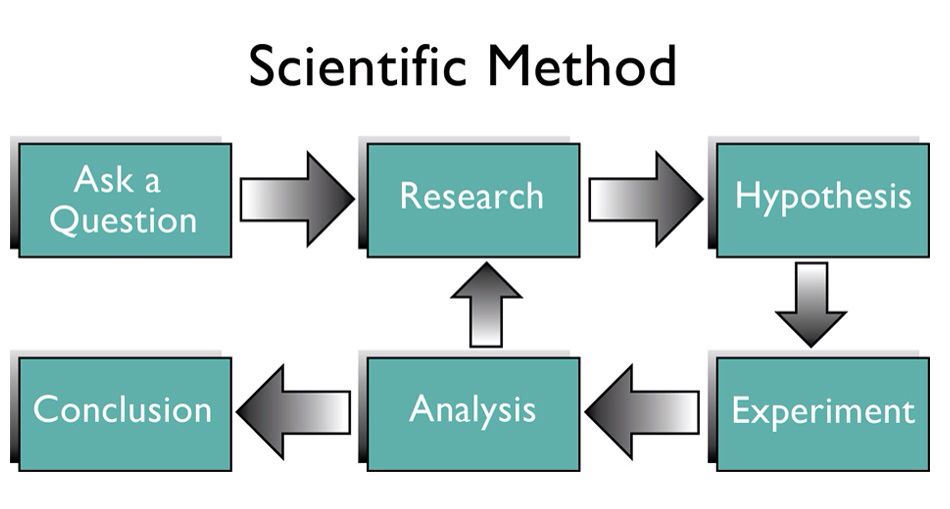

System of problems of psychodiagnostics For conducting psychodiagnostic studies after answering the question "Why?", i.e. after concretizing the purpose of the study, it is necessary to formulate the answer to three questions: "What?", "When?" And How?" will be studied.

Fig. Each of the branches of this scheme is specified for the current task, and the entire procedure of diagnostic research can be divided into separate stages, each of which has an independent goal and significance for the final result. Stages of psychodiagnostic research

The general goal of the study is formulated and its organizational and empirical methods are determined.

A set of properties for study is determined, a possible image of the result is created, a hypothesis is formulated.

Techniques are specified, adequate conditions are created for their use in experiments.

Direct performance of research work, collection of empirical data.

Processing of the obtained results, their explanation from the point of view of a specific scientific and theoretical concept, development of recommendations for practical use. Understanding the psychological dimensionAt present, testology is turning into a science, concentrating more problems than ways to solve them. When developing a test and psychological assessment, five basic requirements are usually taken into account: 1) selection of test items, In other words, measurement in psychodiagnostics is associated with a quantitative assessment of properties. The measurement is based on the comparison operation. Features of the psychological dimension allow us to distinguish three of its types and four levels.

Normative at the ordinal (rank) level. The so-called percentile (percentile) scale is used, the construction of which is not determined by the type of distribution of test scores. The only condition is the possibility of ranking indicators by magnitude. Percentile scale units differ in that arithmetically identical differences in percentile test scores may not correspond to equal differences in the intensity of the property being assessed.

Information received as a result of psychological testing is scaled (S. Stevens, 1939; 1946). "The scaling model determines how scores are derived, the level of measurement obtained (scale type), and the choice of ways to evaluate the functional unity of the resulting measurement tool.

1. Description in natural language. An example of the practical application of this scale of measurement is the compilation of the psychological characteristics of a person who has sought advice or undergoes a psychological examination in the process of solving personnel problems. As a rule, it contains textual material that characterizes this client and distinguishes him from other people. This description of the characterological and behavioral characteristics of the subject makes it possible to speculatively compare his psychological characteristics with those of another person. Strictly speaking, at this point the measurement begins. Psychological measurement is based on the methods of parametric and non-parametric statistics. Nonparametric scales are already actively using mathematical methods. Non-parametric scales 2. Parametric scales When a researcher can measure a psychological attribute, saying that these phenomena differ from each other by such and such a number of arbitrary units, then a new level of measurement based on the parameter appears. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Figure 2 shows a diagram of the tasks of psychodiagnostics from this position.

Figure 2 shows a diagram of the tasks of psychodiagnostics from this position.  2. Scheme of tasks of psychodiagnostics

2. Scheme of tasks of psychodiagnostics

If the empirical distribution differs from the normal one, in most cases it can be artificially normalized (standardized).

If the empirical distribution differs from the normal one, in most cases it can be artificially normalized (standardized).  " In practical psychology, scaling is accepted on four main scales, although there are more of them. Consider six scales of psychological measurement.

" In practical psychology, scaling is accepted on four main scales, although there are more of them. Consider six scales of psychological measurement.  Fuzzy (fuzzy) classification. The content of this scale is the comparison of the features of real objects with the "standard". The standard can be an ideal object (for example, a list of professionally significant qualities of specialists) or a real object (the best in the profession), that is, a similarity to the standard (A). Absolute similarity (identity) to the standard does not exist. Therefore, similarity is determined by the degree of coincidence of features. In practice, the following situation is common: "B is like A; C is like A; but B is not like C." If in the process of psychodiagnostics the evaluation of the "similarity" of the psychological characteristics of people with the help of mathematical calculations is rare, then in the psychology of professions the identity of specialties is determined using the contingency coefficient.

Fuzzy (fuzzy) classification. The content of this scale is the comparison of the features of real objects with the "standard". The standard can be an ideal object (for example, a list of professionally significant qualities of specialists) or a real object (the best in the profession), that is, a similarity to the standard (A). Absolute similarity (identity) to the standard does not exist. Therefore, similarity is determined by the degree of coincidence of features. In practice, the following situation is common: "B is like A; C is like A; but B is not like C." If in the process of psychodiagnostics the evaluation of the "similarity" of the psychological characteristics of people with the help of mathematical calculations is rare, then in the psychology of professions the identity of specialties is determined using the contingency coefficient.  The scale strictly defines the difference of one measured feature (or subject) from another. Often in the questionnaires, a dichotomous scale "works" - "yes-no", which is interpreted in the form of the presence / absence of the trait under study, that is, "the given trait is present or not." For example, the differential diagnostic questionnaire of E. Klimov is interpreted within the framework of this scale as the presence in the subject of signs belonging to five categories (types of activity): "man", "technology", "sign system", "nature" and "artistic image" . The nominal affiliation of the subject to one of the areas determines the absence of signs of other categories in him.

The scale strictly defines the difference of one measured feature (or subject) from another. Often in the questionnaires, a dichotomous scale "works" - "yes-no", which is interpreted in the form of the presence / absence of the trait under study, that is, "the given trait is present or not." For example, the differential diagnostic questionnaire of E. Klimov is interpreted within the framework of this scale as the presence in the subject of signs belonging to five categories (types of activity): "man", "technology", "sign system", "nature" and "artistic image" . The nominal affiliation of the subject to one of the areas determines the absence of signs of other categories in him.  It is on the parametric level of measurement that mathematical statistics is based. The parametric ones include the interval scale, the ratio scale and the absolute scale.

It is on the parametric level of measurement that mathematical statistics is based. The parametric ones include the interval scale, the ratio scale and the absolute scale.  In practice, temperature measurement (in Celsius) occurs on a scale of intervals, since, firstly, zero temperature does not mean that there is no temperature at all, and secondly, intervals expressed in degrees are relative division.

In practice, temperature measurement (in Celsius) occurs on a scale of intervals, since, firstly, zero temperature does not mean that there is no temperature at all, and secondly, intervals expressed in degrees are relative division.