Bowlby stages of grief

Bowlby's FOUR Stages of Grief

For further articles on these topics:

Grief Theory, Attachment

As you may or may not be aware, we’ve been covering some grief theory stuff around here for the past couple months. As a griever I realize it can be infuriating trying to imagine a bunch of stuffy academics sitting around generalizing and theorizing about the anguish of grief. They come up with stages and phases and tasks and labels that you may find totally foreign to your own experience. Someone tells you that you are in the “anger” stage and it makes you want to punch them in the face for thinking they know something about your grief. We get it. Theories have a place, and yet grief is as unique as the griever. The theories aren’t going to work for everyone at ever time (I mean, these academics don’t even agree with each other! We wouldn’t expect you to agree with all of them). So why bother talking about them?

Some of us are rational grievers and it is helpful to know what those academics think about grief. Sometimes just one little part of their theory resonates with us, or one phase they describe is something we are personally struggling with. So this series is our little corner of the internet where, between crazy posts on photography, journaling, baking, and other coping, you can learn a little bit about grief theory and decide whether any of it is helpful to you. It may not be, and that is okay.

Disclaimer: this series is NOT chronological! We started out with some of the grief theory household-names, like Kubler-Ross and Worden, and now we are going back to fill in some gaps. Because although Kubler-Ross gets all the glory for opening the death, dying, and grief dialogue, there were people before her talking about grief, even if it was on a much smaller scale. And they deserve a mention too.

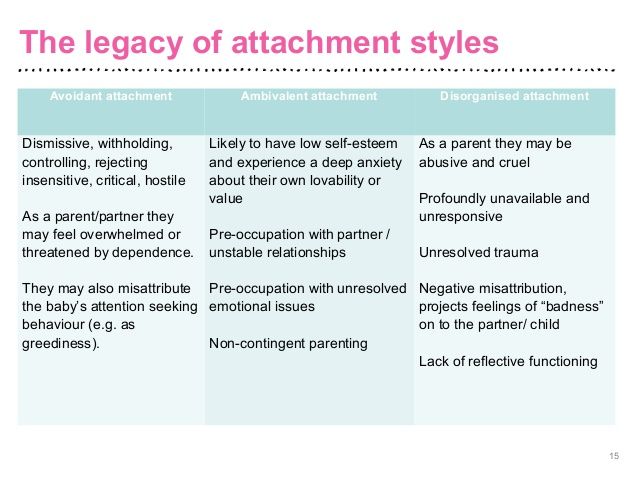

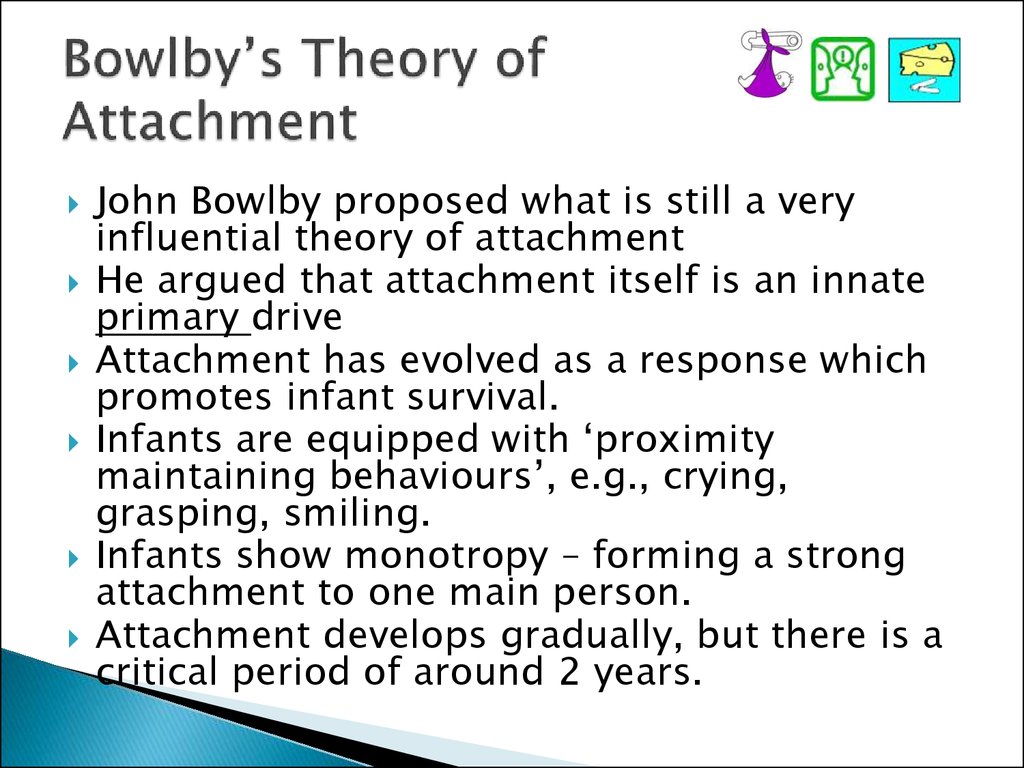

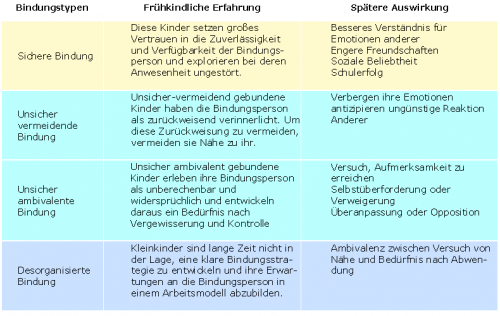

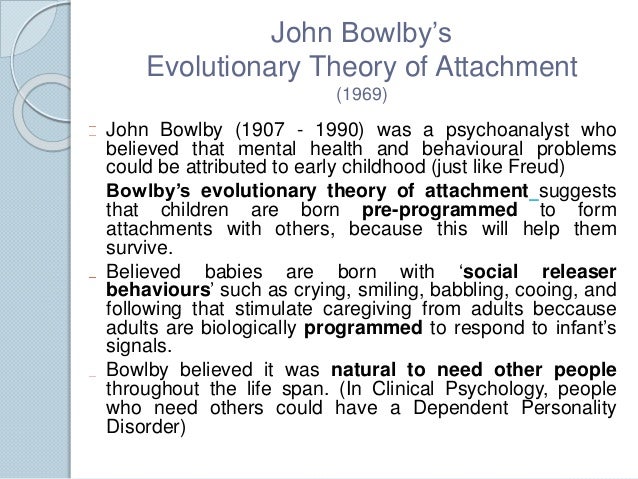

John Bowlby (1907-1990) was a British psychologist and psychiatrist who was a pioneer of attachment theory in children. Bowlby had a strong interest in troubled youth and in determining what family circumstances contributed to healthy versus unhealthy development of children. Working closely with student Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby speculated and tested theories that attachment was a survival mechanism in human evolution, and that children mourned separations from their primary caregivers. His theory of how children form concrete attachments based on actual relationships, rather than fantasies, was a break from the thinking of psychoanalysis of the time.

Working closely with student Mary Ainsworth, Bowlby speculated and tested theories that attachment was a survival mechanism in human evolution, and that children mourned separations from their primary caregivers. His theory of how children form concrete attachments based on actual relationships, rather than fantasies, was a break from the thinking of psychoanalysis of the time.

This was a crucial shift away from Freudian ideas, as well as a break from the idea that attachments developed only through rewards. Bowlby looked at evolutionary biology and other developing scientific study to explore his theory of attachment. He set out to establish a data-driven theory and in 1969 began release of his famous trilogy, Attachment and Loss. After observing the attachment and separation of children and parents, Bowlby asserted a new way of understanding these bonds and the implications of breaking these attachments based on a social system that develop simply by a parent and child being together.

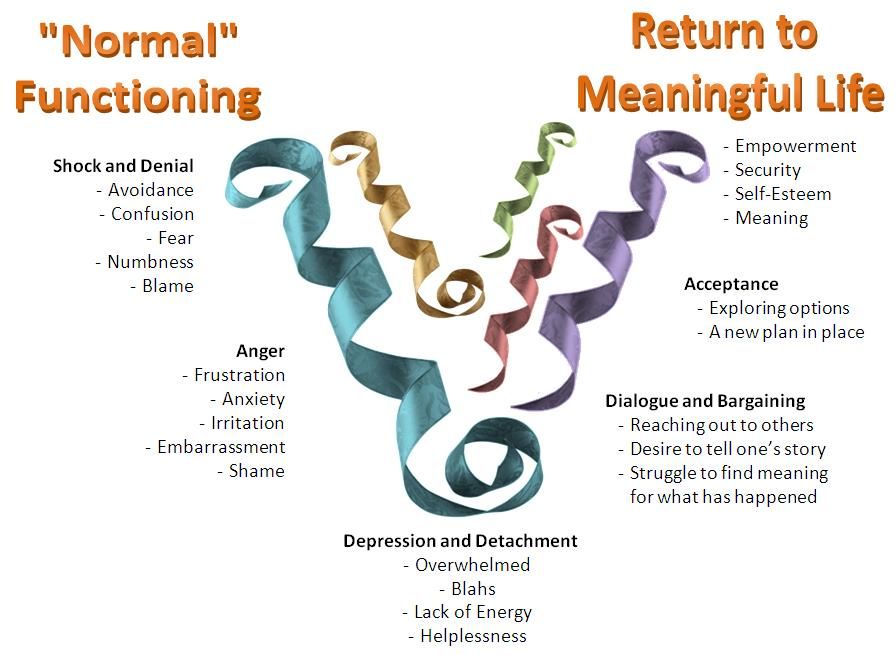

Alright, I know I am losing some of you here in abstract, academia land. I can practically hear people screaming “get to the point!” and “what does this have to do with grief?!?”. We are going to keep it really simple here: Bowlby ultimately took all his observations and theories about attachment and separation and applied them to grief and bereavement. He said there is a relational system in these attachment relationships. These attachments form a system in which the individuals are constantly impacting each other, trying to maintain their relationship in different ways. When a loss occurs Bowlby suggested that grief was a normal adaptive response. He felt the response was based on the environment and psychological make-up of the griever, and that there were normal reactions one might expect. The ‘affectional bond’ had been broken, which result in grief. He later, with his colleague Colin Murray Parkes, broke down this natural adaptive grief response into four phases or stages of grief (really Bowlby started with three and Parkes added a fourth, but whose counting):

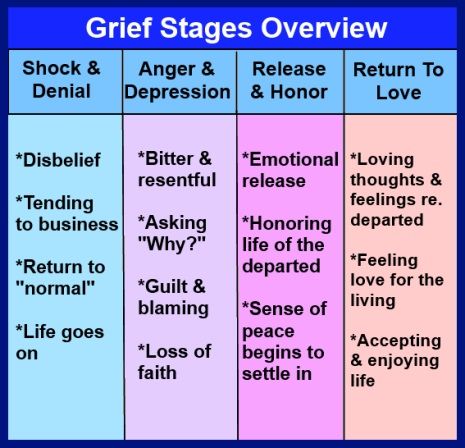

Shock and numbness.

This is the phase where there is a sense the loss is not real and seems impossible to accept. There is physical distress during this phase, which can result in somatic symptoms. If we do not progress through this phase we will struggle to accept and understand our emotions and communicate them. We will emotionally shut-down and not progress through the phases of grief.

Yearning and searching.

In this phase we are acutely aware of the void left in our life from the loss. The future we imagined is no longer a possibility. We search for the comfort we used to have from the person we have lost and we try to fill the void of their absence. We may appear preoccupied with the person. We continue identifying with the person who has died, looking for constant reminders of them and ways to be close to them. If we cannot progress through this phase Bowlby and Parkes feel we will spend our life trying to fill the void of the loss and remain preoccupied with the person we have lost.

Despair and disorganization.

In this stage we have accepted that everything has changed and will not go back to the way it was or the way we imaged. There is a hopelessness and despair that comes with this, as well as anger and questioning. Life feels as though it will never improve or make sense again without the presence of the person who died. We may withdraw from others. Bowlby and Parkes suggest that if we do not progress through this phase we will continue to be consumed by anger, depression, and that our attitude toward life will remain negative and hopeless.

Re-organization and recovery.

In this phase your faith in life starts to be restored. You establish new goals and patterns of day-to-day life. Slowly you start to rebuild and you come to realize that your life can still be positive, even after the loss. Your trust is slowly restored. In this phase your grief does not go away nor is it fully resolved, but for Bowlby the loss recedes and shifts to a hidden section of the brain, where it continues to influence us but is not at the forefront of the mind.

I spend a lot of time thinking about these theories, phases, stages, tasks, whatever and I don’t think any of them are perfect. I tend to pick and choose what works for me, descriptive and prescriptively, and leave the rest. On thing I love about this mode? Stage two – the pain of yearning and searching. If there is anything I relate to it is yearning – the overwhelming want to see someone you have lost again and the experience of trying to make sense of this tremendous void. Worden says we will have to work through the pain; Rando says we will have to react to the separation. But neither of these capture my experience as well as Parkes and Bowlby’s. I remember well seeking ways to be close to someone, seeking objects and reminders, and not being able to imagine a time I would not feel that need. Is the rest of this theory my favorite? Eh, not really. It was a great foundation, but there are a lot of other theories that built on this in ways I appreciate more. But that is okay! Because there is at least one thing in this that really resonates with me, and I certainly appreciate Bowlby and Parkes for their unique attachment perspective that paved the way for so many theories that followed.

One thing I know about grief theories is that they are never all right for all people. For some this theory may ring completely true, for others you may be thinking “thank goodness other theorists came along with their own theories”. But as a griever these theories all normalize in some small way our vast and unique grief experiences.

Missed our other posts in this series? No worries — you can find them all right here.

Wondering where this info came from and how you can do more research on your own?

Bowlby, J. (1961). Processes of mourning. International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 42, 317-339.

Love the Bowlby four stages of grief? Hate the Bowlby four stages of grief? Let us know! Have a grief theory your annoyed we haven’t covered yet? Don’t worry, there are more to come, so subscribe and leave us a comment to let us know what theory you want us to cover.

What Are Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages of Grief?

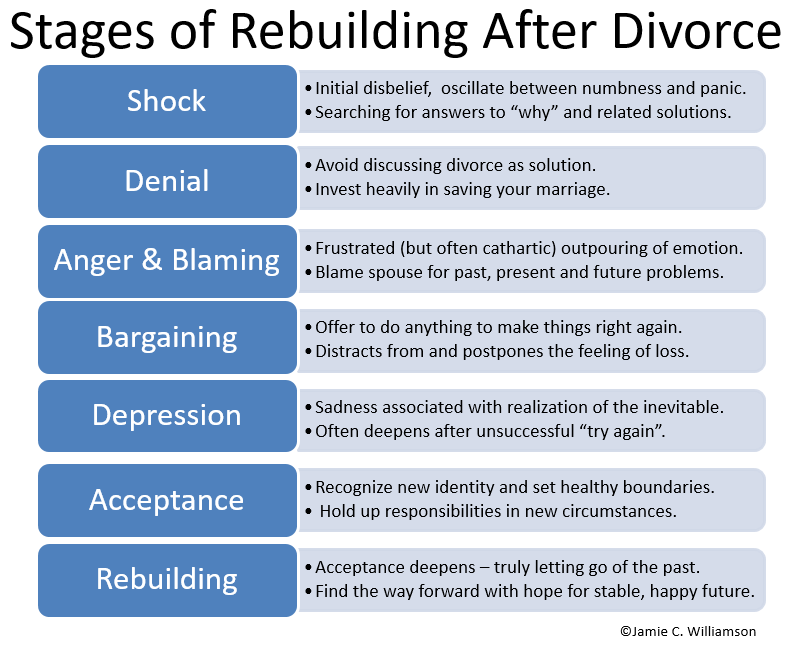

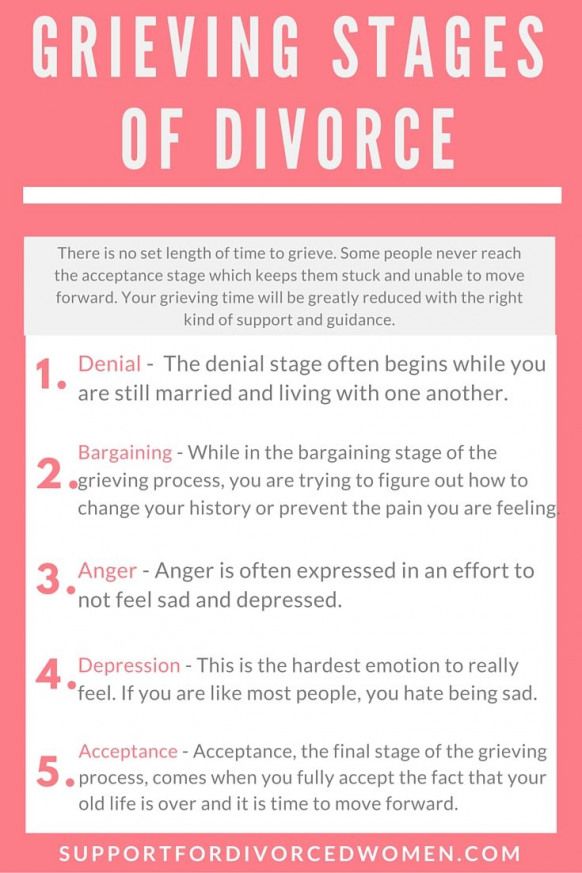

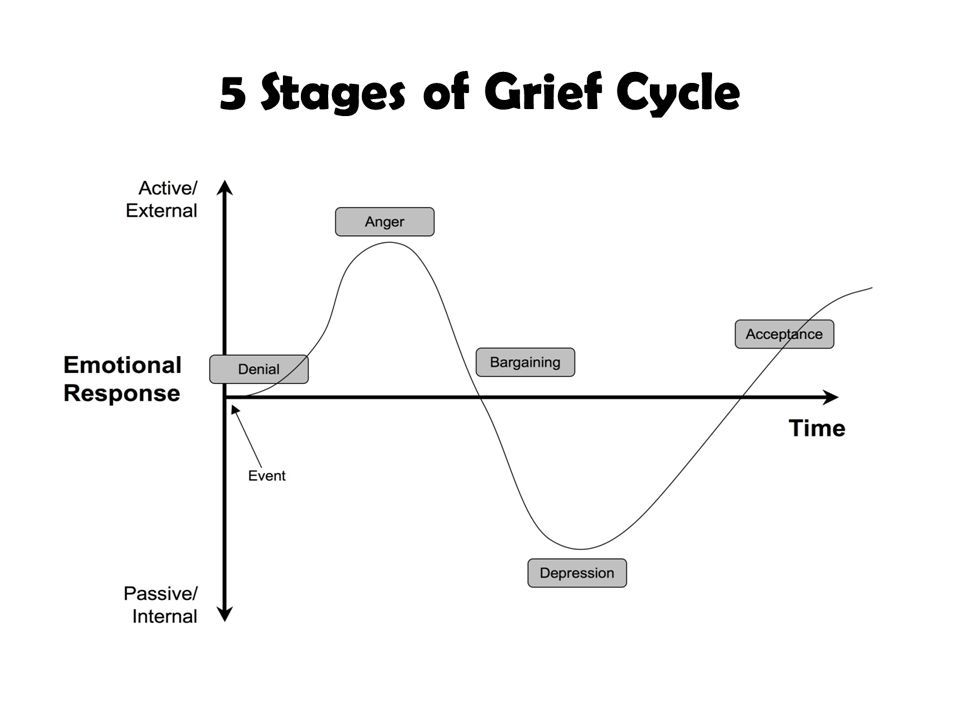

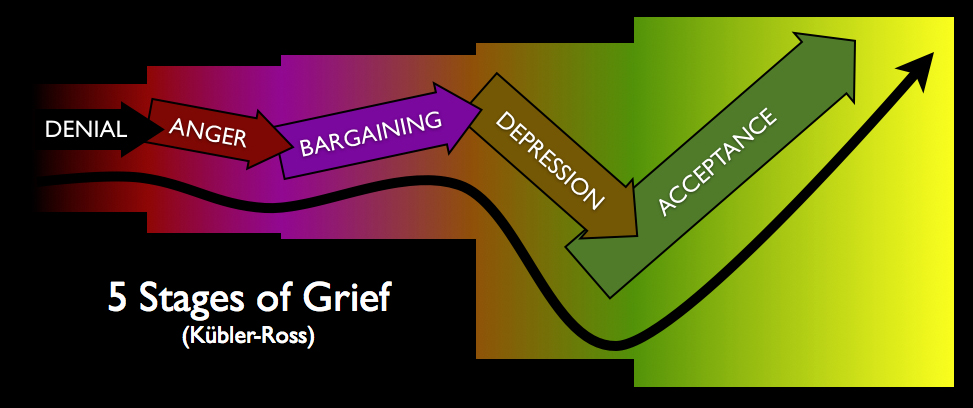

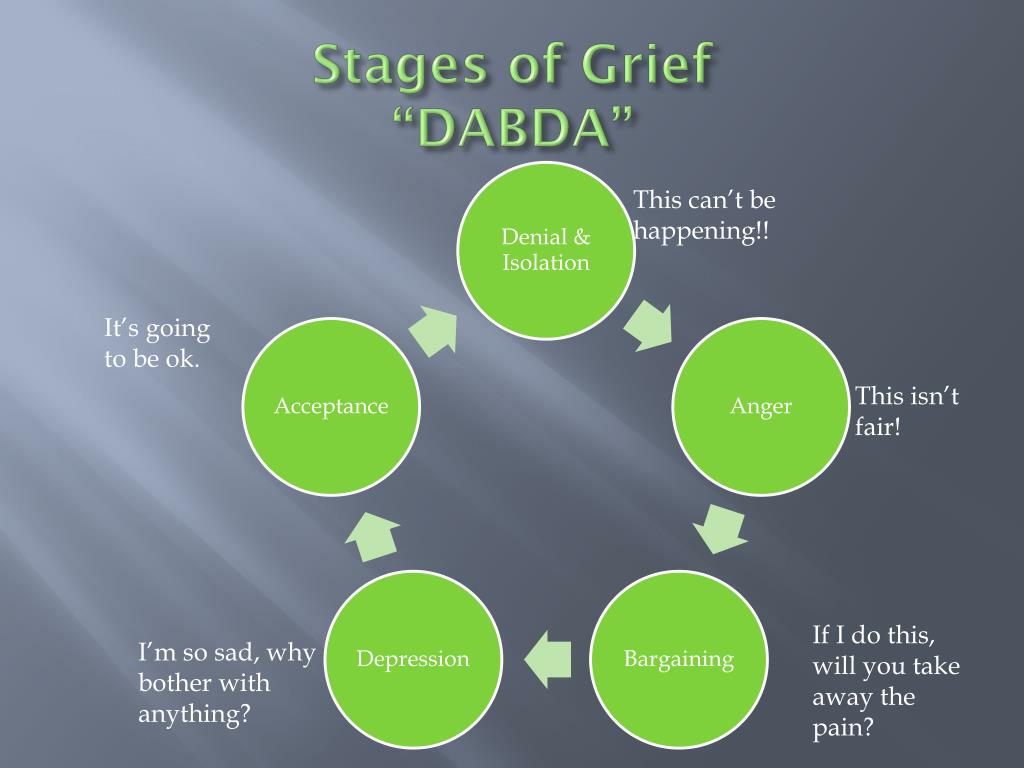

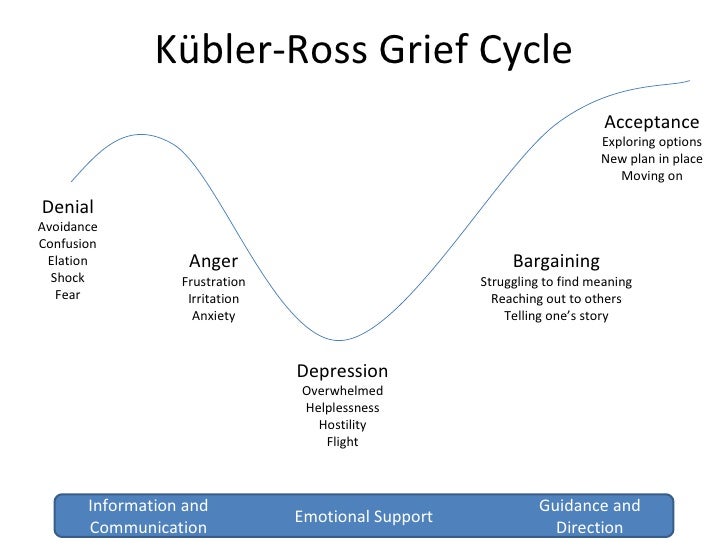

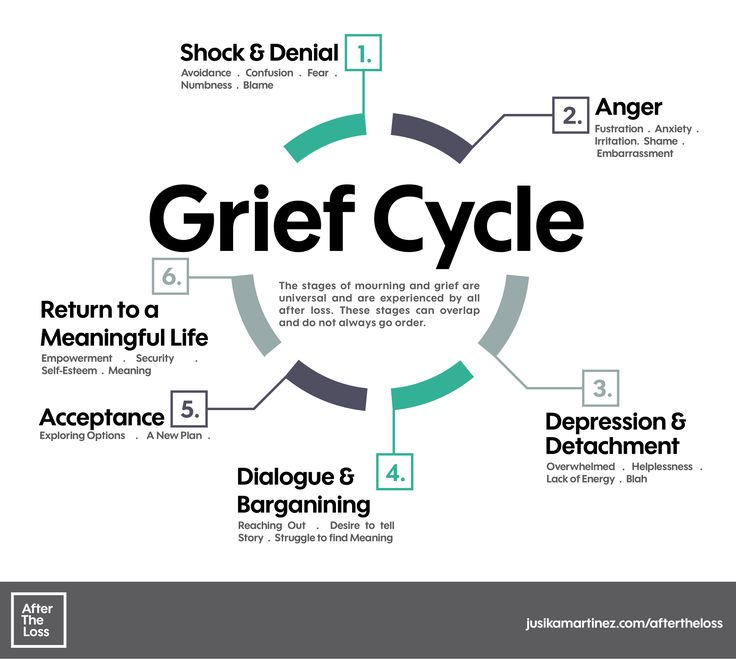

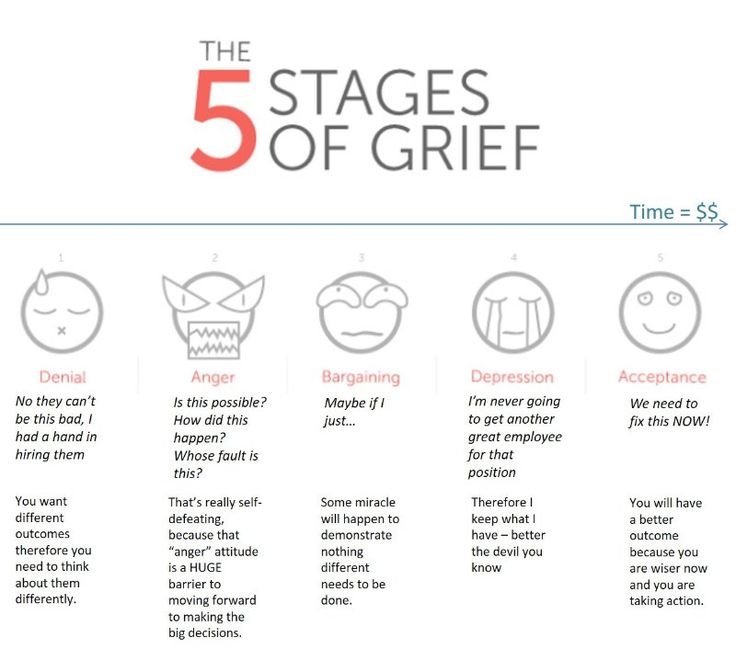

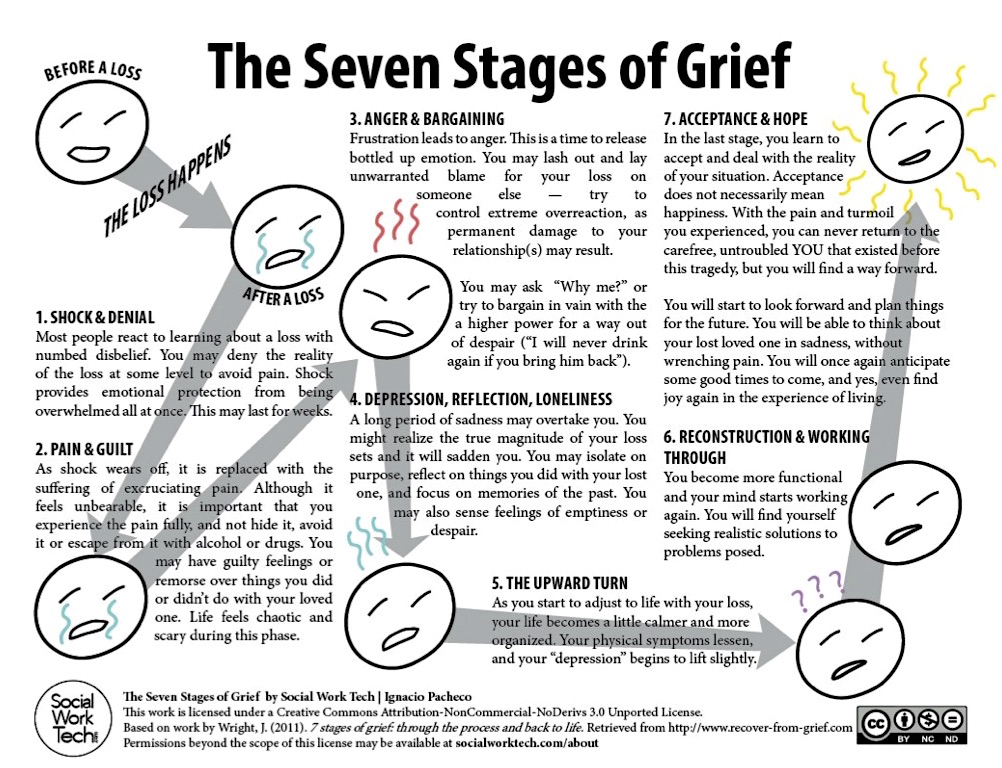

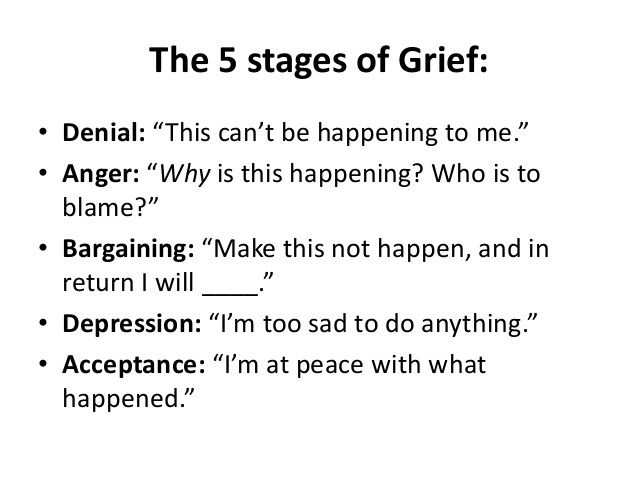

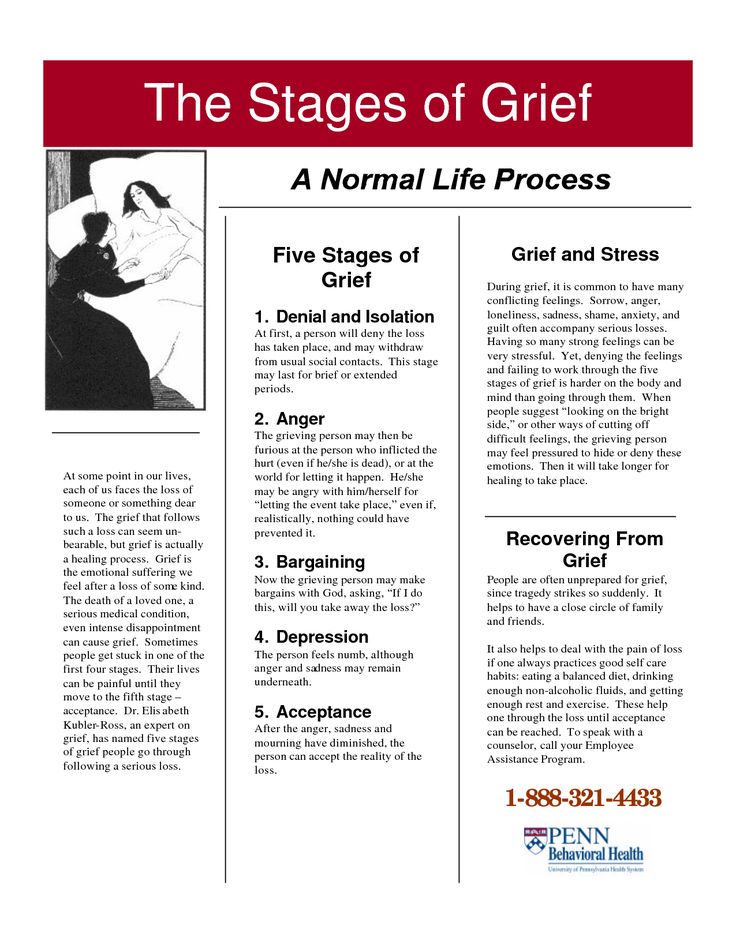

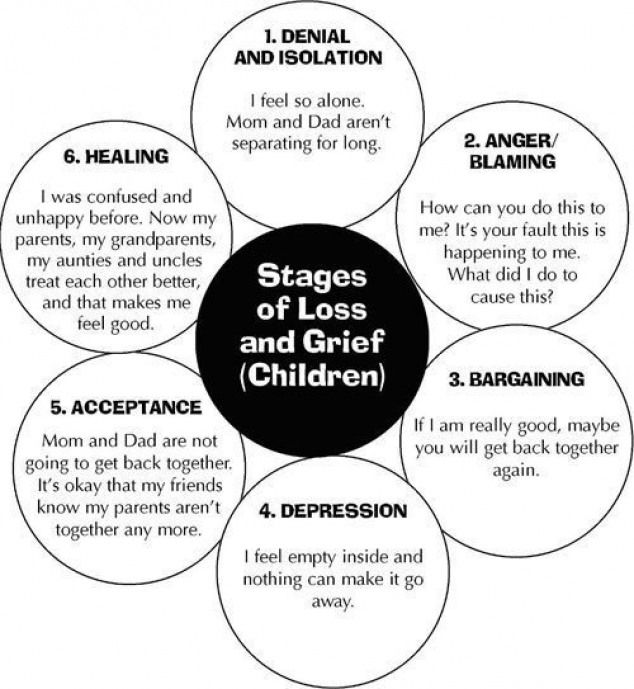

Grief is a universal reaction to loss, but everyone processes grief differently. Several theories exist about why and how individuals grieve certain losses more than others. One of the most well-known grief theories is the “five stages of grief” model by the late Swiss-American Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Her theory centers around how bereaved persons experience grief in sequential stages.

Several theories exist about why and how individuals grieve certain losses more than others. One of the most well-known grief theories is the “five stages of grief” model by the late Swiss-American Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Her theory centers around how bereaved persons experience grief in sequential stages.

Jump ahead to these sections:

- Origin of Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages of Grief

- Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages of Grief Explained

- How Does Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages Compare to Other Models of Grief?

Before Kübler-Ross's five stages of grief model, a British psychologist and psychiatrist named John Bowlby (1907-1990) introduced a four-stage model of grief known as the "grief process." His observations evolved out of an attachment theory in how children develop psychologically based on their family circumstances.

His attachment theory was that children form special bonds with their caregivers and mourn their losses once those bonds break. He then applied his findings to how individuals grieve, coming up with three separate stages. His colleague, Colin Murray Parkes, later added a fourth and final stage.

He then applied his findings to how individuals grieve, coming up with three separate stages. His colleague, Colin Murray Parkes, later added a fourth and final stage.

Origin of Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages of Grief

In 1969, Bowlby began a series of studies on how family circumstances affected children from troubled backgrounds. His research wasn't originally based on grief and loss but strictly on a child's behavioral reactions to losing their attachments.

Bowlby soon discovered that children suffer from loss when separated from their parents and caregivers, which affects their psychological development. Because the child’s removal from the home breaks the affection bond, Bowlby observed that this loss resulted in grief. Only later did he and his colleague, Parkes, correlate how children grieve and mourn these losses.

Bowlby and Parkes's four stages of grief evolved from this study initially related to attachment theory. Bowles concluded that children's relationships with parents and caregivers have a lasting impact on how they grieve. He confirmed that whenever a child experiences the loss of a caregiver, the strength of the bond to that individual determines the child's grief reactions.

He confirmed that whenever a child experiences the loss of a caregiver, the strength of the bond to that individual determines the child's grief reactions.

Bowlby and Parkes further explored this theory from a grieving standpoint, realizing that loss leads to a natural grief response in children. From this research, they came up with the four stages of grief explained below.

LIMITED TIME OFFER: Get 50% off your online will using code FIFTYBLOG. Expires 10/23/2022.

Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages of Grief Explained

The four stages of grief developed and introduced by Bowlby and Parkes are some of the earliest findings on which Kübler-Ross and others base their grief model theories. Although they’re at opposite sides of the spectrum, there are many correlations to how bereaved individuals process their grief between the two theories.

One of the significant differences is that Kübler-Ross based her work on dying patients, while Bowlby and Parkes’s work related to studying mourning survivors. Here’s are the four stages of grief introduced by Bowlby and Parkes.

Here’s are the four stages of grief introduced by Bowlby and Parkes.

1. Shock and numbness

The first of the four stages relate to how the mind reacts to the news of the loss. Loss isn't always associated with the death of a loved one or the physical loss of material things. Sometimes loss occurs as a result of broken relationships and the loss of family and home. Bereaved individuals experience the initial stages of grief known as shock and disbelief when they first suffer through trauma.

In this stage, shared grief reactions include feeling numb, withdrawing emotionally, and becoming stuck in grief. It's especially hard for bereaved individuals coping with the first holiday season without a loved one, further aggravating the shock factor of their loss.

2. Yearning and searching

An individual who suddenly or violently loses someone or something they have a special attachment to often yearns for that person or thing to return. In adults and children alike, this stage of grief represents the acknowledgment of the loss of relationships resulting from a death or another tragedy. When a grieving person can't move past the unconscious yearning for loss, the grieving process is delayed and often exacerbated.

When a grieving person can't move past the unconscious yearning for loss, the grieving process is delayed and often exacerbated.

Many people will spend months, even years, yearning and searching. In this stage, it's typical for grieving individuals to experience other intense grief reactions, including preoccupation, anger, and hostility, especially at times when they remember deceased loved ones, such as at Christmas.

🎃 PROMO: Been waiting for a deal? Online wills are 50% off through 10/23/2022. Use code FIFTYBLOG.

3. Disorganization and despair

This stage is when changed behaviors become necessary for a suffering individual to progress through their grief. A person suffering through loss must learn to do away with old behavior patterns and ways of thinking. Survivors often experience feelings of disorganization while trying to accept that their life is no longer the same.

Despair is also a grief reaction that manifests during this stage, sometimes leading to depression and apathy. In time, those suffering through loss will begin to emerge from this stage with renewed hope and ideas on surviving their grief. This period is one of self-reflection, renewal, and reinvention.

In time, those suffering through loss will begin to emerge from this stage with renewed hope and ideas on surviving their grief. This period is one of self-reflection, renewal, and reinvention.

4. Reorganization and repair

The final stage in the grief process involves the restoration of hope and a renewed sense of purpose in life. After coming to terms with loss, bereaved individuals slowly realize that life is worth living once more. They begin to find joy and even start new holiday traditions.

To get to this phase of reorganization and repair, a person must first go through the process of breaking who they used to be. They must learn to consolidate the roles they filled within their past relationships and who they are now. Only after they undergo this realization can they begin the transformative process of resolving their grief.

How Does Bowlby and Parkes’s Four Stages Compare to Other Models of Grief?

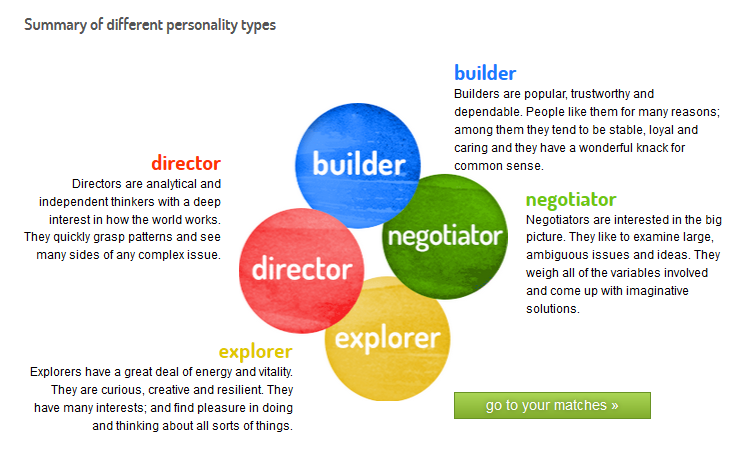

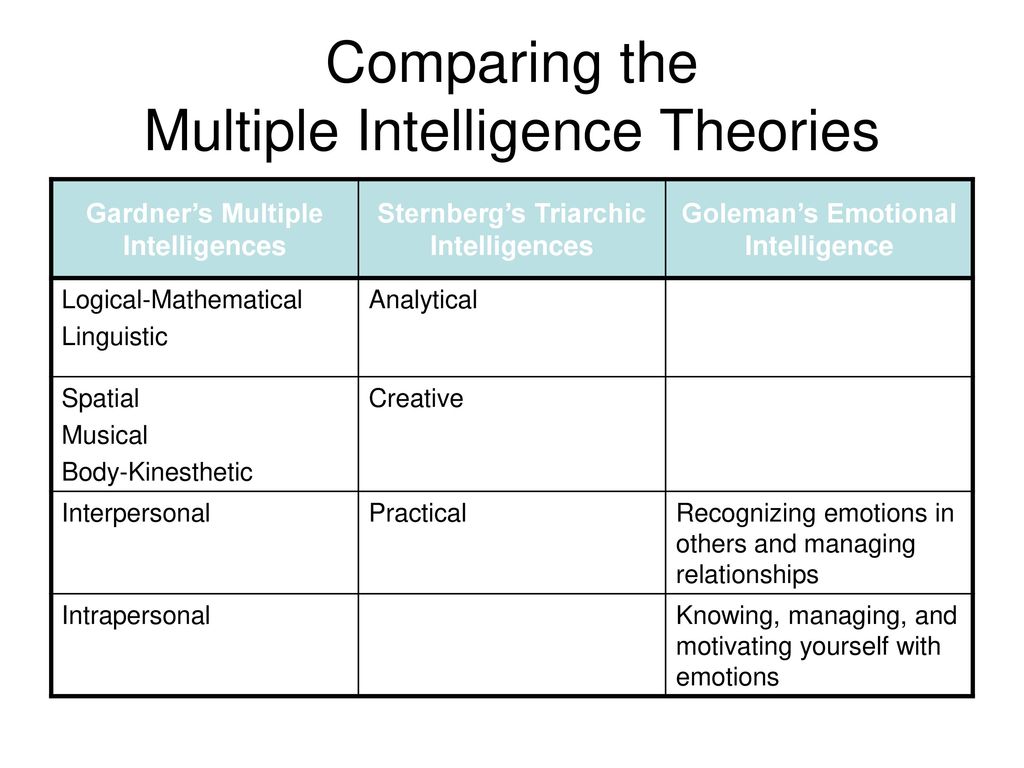

Through the past several decades, psychologists have introduced different models of grief to explain the grieving process according to their research and findings. The following models are some of the more widely referenced in the fields of grief and bereavement.

The following models are some of the more widely referenced in the fields of grief and bereavement.

Although there are many differing views on how to heal from grief, the basic premise of each of these models is that to heal from grief, you must first acknowledge it to begin working toward healing.

Not ready to start your will?

It's a big step and we get it! Share your email and we'll remind you in a few days.

Thank you for subscribing. Expect an email soon!

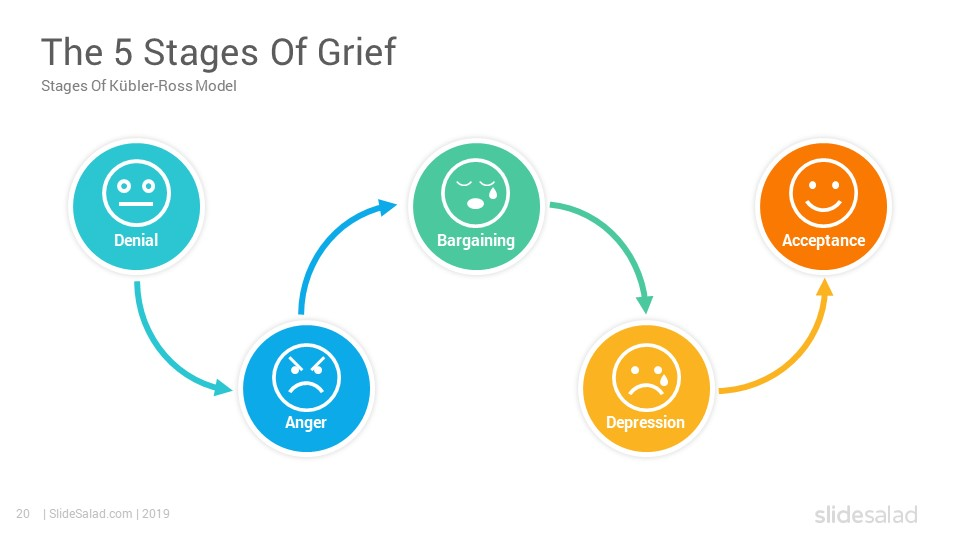

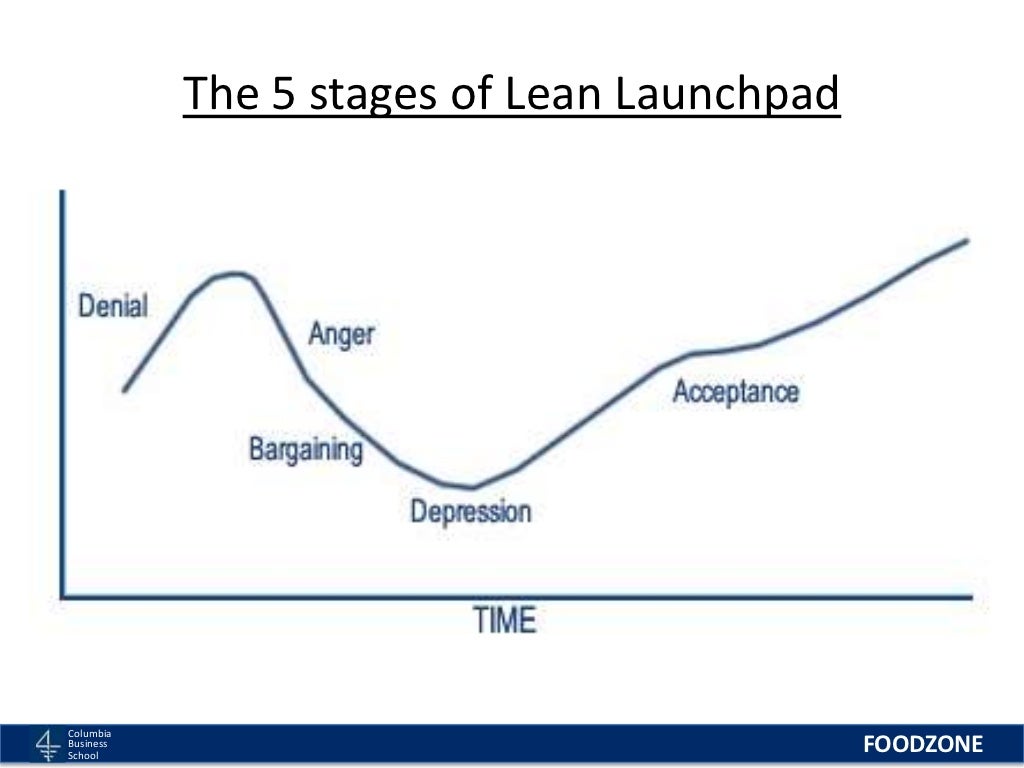

Kübler-Ross’s Five Stages of Grief

Kübler-Ross developed her Five Stages of Grief model after conducting clinical research on terminally ill patients. She first introduced her grief model in her book On Death and Dying, initially published in 1969.

At the time, her findings were and remain somewhat controversial. She introduced the concept of a linear grief experience that goes through the stages of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. While not everyone will experience all of these stages of grief, many bereaved individuals have many of these shared grief reactions. The Kübler-Ross model remains one of the most referenced grief models to date despite its controversies.

The Kübler-Ross model remains one of the most referenced grief models to date despite its controversies.

One of the most significant differences between the Bowlby and Parkes's and Kübler-Ross models is that Bowlby and Parkes studied grief's effects on trauma survivors while Kübler-Ross focused on the impact of grief on dying individuals.

Worden’s Four Tasks of Mourning

Psychologist William Worden authored the book Grief Counselling and Grief Therapy, in which he first outlined the Four Tasks of Mourning. In his book, Worden suggests that for bereaved individuals to heal from grief, they must first accomplish four grief-related tasks. He bases his grief model on having the flexibility to adapt to any grief situation. The tasks include:

- Accepting the reality of the loss

- Working through the pain and grief

- Adjusting to the new environment

- Finding a connection to the deceased while moving forward in life

Unlike Bowley and Parkes’s grief model, Worden doesn’t link the success of his model with an attachment theory. Worden suggests that these tasks of mourning are adaptable to any grief situation, and once completed, the bereaved can revisit any or all of the functions to make adjustments as needed.

Worden suggests that these tasks of mourning are adaptable to any grief situation, and once completed, the bereaved can revisit any or all of the functions to make adjustments as needed.

Rando’s Six R Process of Mourning

Dr. Theresa Rando’s six-step process to healing from grief is a three-stage process. Her model relies on bereaved individuals working through their grief toward healing.

Her grief model breaks down as follows:

Phase One: Avoidance

There’s only one task to accomplish in this first phase: recognizing the loss. According to Rando’s theory, until bereaved individuals learn to accept their loss, they can’t move forward from their grief and begin the second phase of the healing process. The task associated with this phase is:

- Recognizing the loss

Phase Two: Confrontation

During this phase, the bereaved come to terms with their grief reactions and feelings of loss and mourning. Here, the grieving individual must learn ways to process their grief. The tasks associated with this phase include:

The tasks associated with this phase include:

- Reacting to the loss

- Recollecting and re-experiencing the relationship with the deceased

- Relinquishing old attachments

Phase Three: Accommodation

This final phase is about finding new meaning in life after loss and rebuilding. Loss survivors might consider new hobbies, moving to a different house or city, and taking the time to learn about themselves post-loss. This phase includes:

- Readjusting to life

- Reinvesting of emotional energy

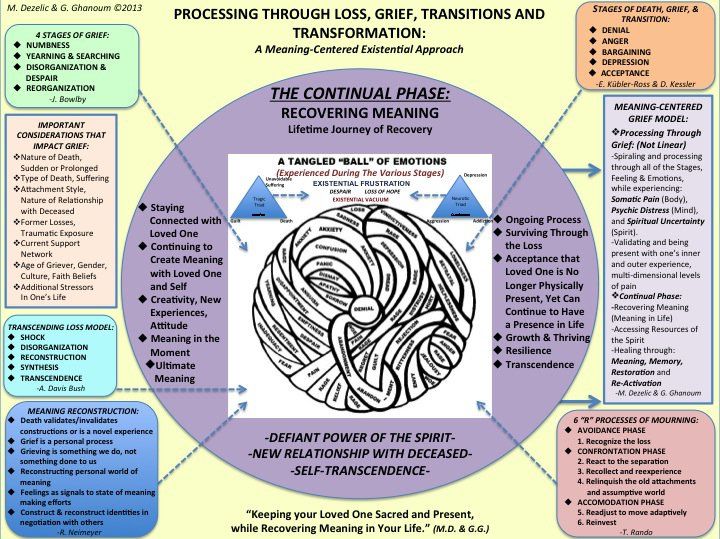

Rando’s and Bowley’s and Parkes’s models for understanding the grief process have similarities in that they both rely on integration and processing, leading to adaptation. They both recognize the need for a period of disorganization before reorganization can take place. The differences between the two are that Rando paints a much broader picture of the grief process while Bowley and Parkes have a more limiting feelings-based view of how individuals react to grief.

How the Four Stages of Grief Impact Healing

With so many differing views and opinions on what makes up a more profound healing experience for grieving individuals, it’s easy to get lost in the theories. As you learn and discover more about your grief, keep in mind that there isn’t any wrong way to grieve. Your grief experience remains unique to you, and the path to healing is also yours to discover.

Sources:

- Maciejewski PK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. An Empirical Examination of the Stage Theory of Grief. JAMA. 2007;297(7):716–723. doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.716 jamanetwork.com

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a seminar with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption,Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

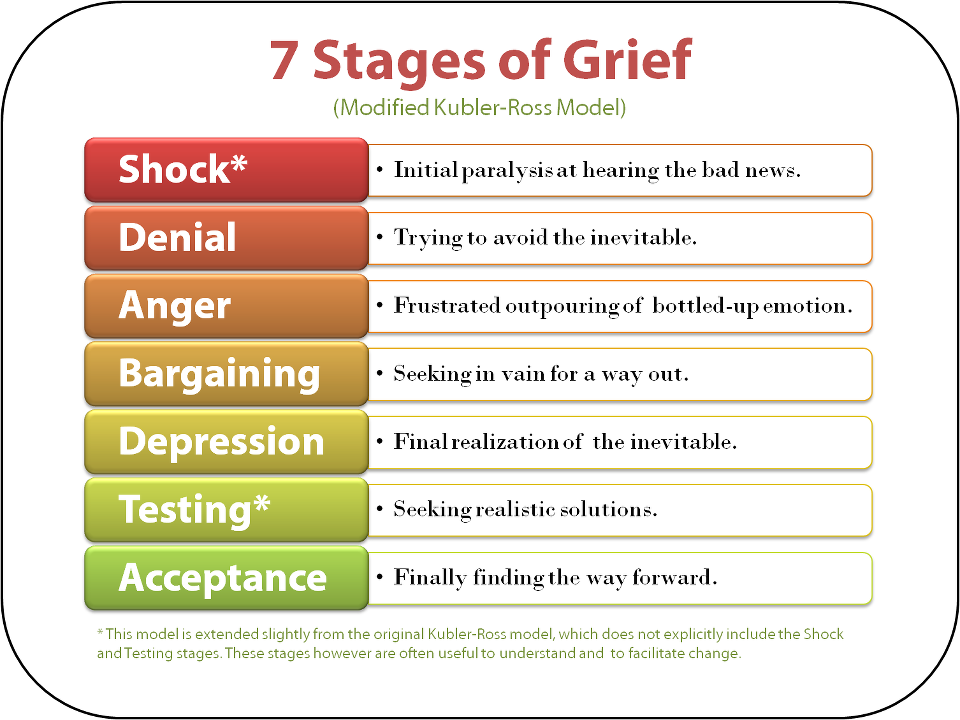

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

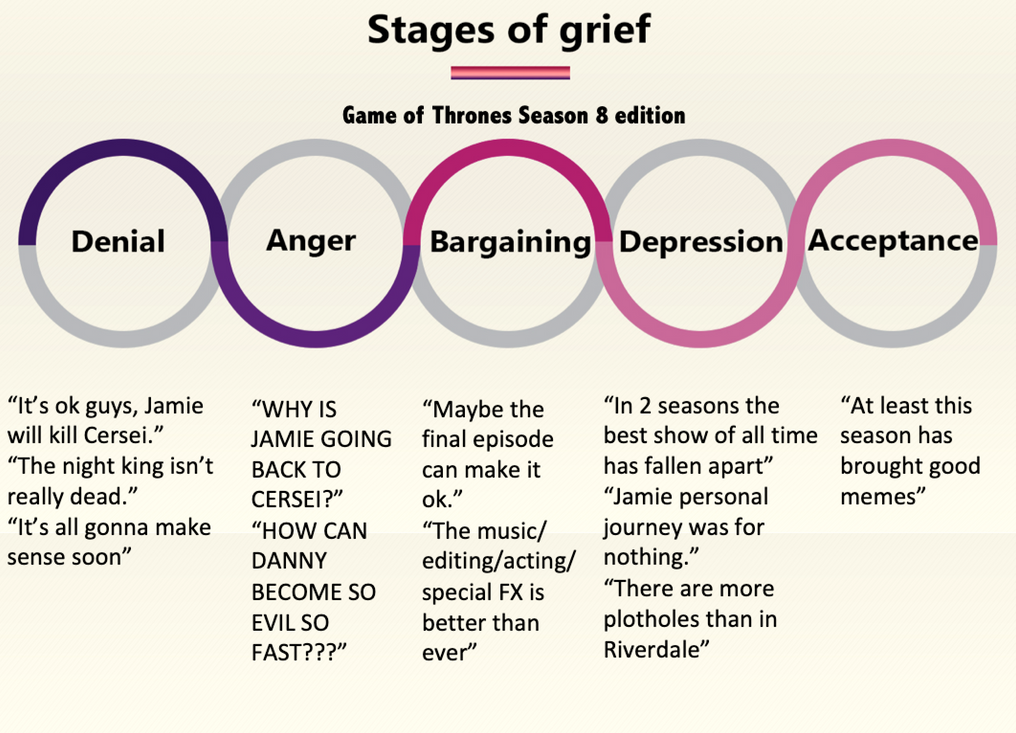

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief. ” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

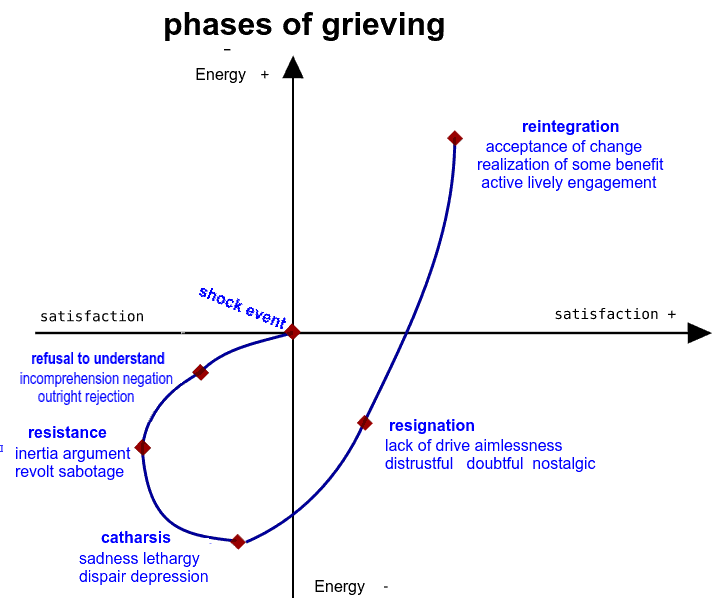

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

5 stages of grief | Dmitry Ustinov

The word "experience" has a double meaning. The first is a strong negative feeling. The second one is from the word “survive”, i.e. to pass, to advance along the path, through life. During the "experience" it is important not to get stuck and, indeed, to move on. Grief is something that happens to everyone, sooner or later, tomorrow or years from now.

Grief is something that happens to everyone, sooner or later, tomorrow or years from now.

This is how life works. It happens that we lose something very expensive, sometimes the loss of a beloved job, the departure of a loved one, the loss of a large amount of money is comparable to grief. Loved ones die. Finally, we stand on the threshold of eternity, having read the diagnosis on the official letterhead. We strive not to think about grief in advance, we drive thoughts away, the psychoprotective mechanism “repression” works, as they say in psychology. But this method is not always optimal. It is important to be prepared before the thunder strikes.

Psychology is a cynical science. Knowing the basic stages of grief helps you move forward and cope. Elemental grief is the most destructive. If we know how it works, we know how the mechanisms of our psyche work, we can approach such situations not spontaneously, but consciously, i.e. with an understanding of what is happening. So, there is an opportunity to influence these experiences.

So, there is an opportunity to influence these experiences.

This cup did not pass me by either, and I clearly understand that it will not pass in the future either. And I know these stages well from my own experience. What exactly?

1. Stage of denial

The person refuses to acknowledge the traumatic situation. The main thought beats in my head: “No! It's not with me! This can't happen to me!" The man refuses to accept the facts. Death of a loved one. Losing a child. Doesn't trust doctors. Refuses himself and those around him. It cannot be said that he has gone crazy, but temporarily his psyche is not consistent with reality. Although there are extreme cases when this temporary insanity becomes permanent. Then for the human psyche, reality and his very personality become incompatible things - and consciousness goes into a less traumatic world of other dreams. Then really those around you have to admit that the person "has gone crazy with grief."

2. Stage of anger and aggression

A person in anger blames and attacks everything that he thinks is relevant and may be the cause of his grief. On the deceased loved one, who was inattentive. On himself, who did not foresee and did not warn. The doctors who misdiagnosed the child. On the doctors who made the correct diagnosis. On medicine, which is powerless. On a mediocre government that does not know what is happening in his country. We can say that this is the stage of searching for the enemy.

On the deceased loved one, who was inattentive. On himself, who did not foresee and did not warn. The doctors who misdiagnosed the child. On the doctors who made the correct diagnosis. On medicine, which is powerless. On a mediocre government that does not know what is happening in his country. We can say that this is the stage of searching for the enemy.

My friend worked as an ambulance doctor. Most often, in such situations, it is the doctor who gets it, less often the driver, and there is always a reason - they drove for a long time, they didn’t treat it the last time, they studied poorly at the institute, three students. Although introverts are characterized by simply quiet or even silent condemnation and accusation. But this is also a stage of aggression.

3. The stage of compromise and trade

At this stage, a person tries to negotiate with fate and God, looks for a compromise, looks for an opportunity to somehow pay off this difficult situation. It seems to him that it is not too late to fix everything. Believers read prayers. Unbelievers also turn to higher powers:

Believers read prayers. Unbelievers also turn to higher powers:

I promise, Universe, if you help, I'll be good! I will believe in God. I will go to church. I will help my neighbor. I'll quit drinking. I will live a new life. Just do something!

At this stage, there are also cases of conversion to faith, although more often it is the other way around. Having received healing or returning a child from intensive care, a person thanks heaven and returns to his former life.

4. Stage of depression and apathy

In it, a person loses interest in life, loses all meaning. Nothing pleases him, he can look at one point for hours. Necessary to maintain the physiology of the case, he performs on the machine. Depression and indifference to the outside world is the dominant state. In psychology, this is sometimes referred to as the "victim" state. Often the most protracted stage. A close friend of mine, who suffered from a stroke, has been in a stage of depression for many years, sometimes again briefly replaced by a stage of condemnation of the world.