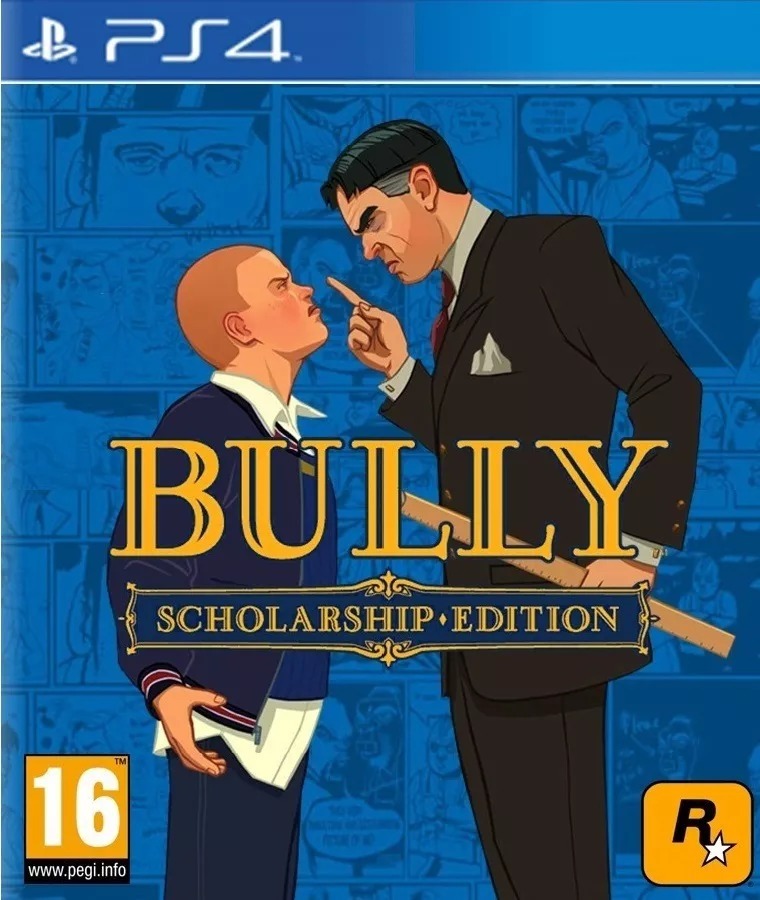

Work bully signs

Facts About Bullying | StopBullying.gov

This section pulls together fundamental information about bullying, including:

- Definition

- Research on Bullying

- Bullying Statistics

- Bullying and Suicide

- Anti-Bullying Laws

Definition of Bullying

In 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Department of Education released the first federal definition of bullying. The definition includes three core elements:

- unwanted aggressive behavior

- observed or perceived power imbalance

- repetition or high likelihood of repetition of bullying behaviors

This definition helps determine whether an incident is bullying or another type of aggressive behavior or both.

Research on Bullying

Bullying prevention is a growing research field that investigates the complexities and consequences of bullying. Important areas for more research include:

- Prevalence of bullying in schools

- Prevalence of cyberbullying in online spaces

- How bullying affects people

- Risk factors for people who are bullied, people who bully others, or both

- How to prevent bullying

- How media and media coverage affects bullying

What We’ve Learned about Bullying

- Bullying affects all youth, including those who are bullied, those who bully others, and those who witness bullying.

The effects of bullying may continue into adulthood.

- There is not a single profile of a young person involved in bullying. Youth who bully can be either well connected socially or marginalized, and may be bullied by others as well. Similarly, those who are bullied sometimes bully others.

- Solutions to bullying are not simple. Bullying prevention approaches that show the most promise confront the problem from many angles. They involve the entire school community—students, families, administrators, teachers, and staff such as bus drivers, nurses, cafeteria and front office staff—in creating a culture of respect. Zero tolerance and expulsion are not effective approaches.

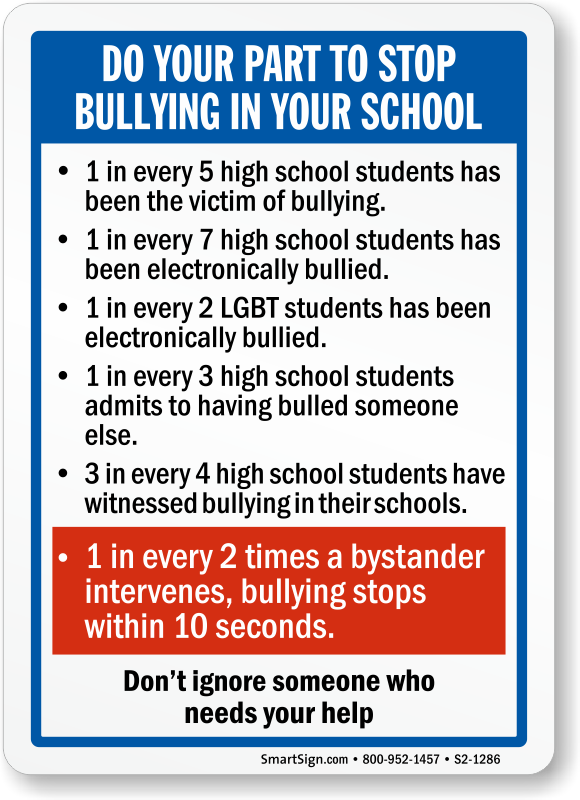

- Bystanders, or those who see bullying, can make a huge difference when they intervene on behalf of someone being bullied.

- Studies also have shown that adults can help prevent bullying by talking to children about bullying, encouraging them to do what they love, modeling kindness and respect, and seeking help.

Bullying Statistics

Here are federal statistics about bullying in the United States. Data sources include the Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2019 (National Center for Education Statistics and Bureau of Justice) and the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

How Common Is Bullying

- About 20% of students ages 12-18 experienced bullying nationwide.

- Students ages 12–18 who reported being bullied said they thought those who bullied them:

- Had the ability to influence other students’ perception of them (56%).

- Had more social influence (50%).

- Were physically stronger or larger (40%).

- Had more money (31%).

Bullying in Schools

- Nationwide, 19% of students in grades 9–12 report being bullied on school property in the 12 months prior to the survey.

- The following percentages of students ages 12-18 had experienced bullying in various places at school:

- Hallway or stairwell (43.

4%)

4%) - Classroom (42.1%)

- Cafeteria (26.8%)

- Outside on school grounds (21.9%)

- Online or text (15.3%)

- Bathroom or locker room (12.1%)

- Somewhere else in the school building (2.1%)

- Hallway or stairwell (43.

- Approximately 46% of students ages 12-18 who were bullied during the school year notified an adult at school about the bullying.

Cyberbullying

- Among students ages 12-18 who reported being bullied at school during the school year, 15 % were bullied online or by text.

- An estimated 14.9% of high school students were electronically bullied in the 12 months prior to the survey.

Types of Bullying

- Students ages 12-18 experienced various types of bullying, including:

-

- Being the subject of rumors or lies (13.

4%)

4%) - Being made fun of, called names, or insulted (13.0%)

- Pushed, shoved, tripped, or spit on (5.3%)

- Leaving out/exclusion (5.2%)

- Threatened with harm (3.9%)

- Others tried to make them do things they did not want to do (1.9%)

- Property was destroyed on purpose (1.4%)

- Being the subject of rumors or lies (13.

State and Local Statistics

Follow these links for state and local figures on the following topics:

- Bullied on School Property, Grades 9-12

- Cyberbullied, Grades 9-12

International Statistics

According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics:

- One third of the globe’s youth is bullied; this ranges from as low as 7% in Tajikistan to 74% in Samoa.

- Low socioeconomic status is a main factor in youth bullying within wealthy countries.

- Immigrant-born youth in wealthy countries are more likely to be bullied than locally-born youth.

Bullying and Suicide

The relationship between bullying and suicide is complex. The media should avoid oversimplifying these issues and insinuating or directly stating that bullying can cause suicide. The facts tell a different story. It is not accurate and potentially dangerous to present bullying as the “cause” or “reason” for a suicide, or to suggest that suicide is a natural response to bullying.

The media should avoid oversimplifying these issues and insinuating or directly stating that bullying can cause suicide. The facts tell a different story. It is not accurate and potentially dangerous to present bullying as the “cause” or “reason” for a suicide, or to suggest that suicide is a natural response to bullying.

- Research indicates that persistent bullying can lead to or worsen feelings of isolation, rejection, exclusion, and despair, as well as depression and anxiety, which can contribute to suicidal behavior.

- The vast majority of young people who are bullied do not become suicidal.

- Most young people who die by suicide have multiple risk factors.

- For more information on the relationship between bullying and suicide, read “The Relationship Between Bullying and Suicide: What We Know and What it Means for Schools” from the CDC.

Anti-Bullying Laws

All states have anti-bullying legislation. When bullying is also harassment and happens in the school context, schools have a legal obligation to respond to it according to federal laws.

20 Subtle Signs of Bullying at Work

If you think workplace bullying doesn’t affect some of your employees, you're mistaken. One in four employees is affected by it. There is a misconception that bullying is overt. Rather, it’s often subtle, slow, and insidious mistreatment that passes over the radar screen.

Rarely can bullying be identified based on one action, but rather a pattern of actions over a long period of time. This is why it so often goes undetected in the workplace, and your employees could be suffering because of it.

Bullying Defined

The Workplace Bullying Institute defines bullying as “repeated, health-harming mistreatment of one or more persons (the targets) by one or more perpetrators that takes one or more of the following forms: verbal abuse, offensive conduct/behaviors (including nonverbal) which are threatening, humiliating, or intimidating; or work interference – sabotage – which prevents work from getting done.”

The primary issue with bullying is that the perpetrator desires to control the other person’s behavior, usually for his or her own needs, personal agenda, or self-serving motives. Bullies use a variety of subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle ways to control others emotionally, psychologically, and even physically.

Bullies use a variety of subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle ways to control others emotionally, psychologically, and even physically.

Adept bullies and manipulators are often extremely controlling people who are attuned to certain personality traits to exploit others. They are skilled “people readers” and make it their task to understand someone’s flaws to determine what techniques can be used against them. Some even go a step further and mask their bullying behind a charming and nice demeanor and even a noble cause.

Subtle Signs of Bullying

Bullying often goes unnoticed in the workplace because it is a slow process of emotional and psychological manipulation that is hard to prove and detect. It is also not protected under law. Technically, bullying is not considered harassment, so legally, people can get away with doing it in the workplace if a policy isn’t in place.

Here are twenty (20) signs of bullying at work that you may be missing, but when a pattern emerges of multiple behaviors over a long period of time, can be a classic bullying situation. These subtle signs are all used to create an emotional reaction, usually anxiety, which establishes greater control and power over the victim.

These subtle signs are all used to create an emotional reaction, usually anxiety, which establishes greater control and power over the victim.

- Deceit. Repeatedly lying, not telling the truth, concealing the truth, deceiving others to get one’s way, and creating false hopes with no plans to fulfill them

- Intimidation. Overt or veiled threats; fear-inducing communication and behavior

- Ignoring. Purposefully ignoring, avoiding, or not paying attention to someone; “forgetting” to invite someone to a meeting; selectively greeting or interacting with others besides a victim

- Isolation/exclusion. Intentionally excluding someone or making them feel socially or physically isolated from a group; purposefully excluding someone from decisions, conversations, and work-related events

- Rationalization. Constantly justifying or defending behavior or making excuses for acting in a particular manner

- Minimization.

Minimizing, discounting, or failing to address someone’s legitimate concerns or feelings

Minimizing, discounting, or failing to address someone’s legitimate concerns or feelings - Diversion. Dodging issues, acting oblivious or playing dumb, changing the subject to distract away from the issue, canceling meetings, and avoiding people

- Shame and guilt. Making an employee constantly feel that they are the problem, shaming them for no real wrongdoing, or making them feel inadequate and unworthy

- Undermining work. Deliberately delaying and blocking an employee’s work, progress on a project or assignment, or success; repeated betrayal; promising them projects and then giving them to others; alternating supportive and undermining behavior

- Pitting employees against each other. Unnecessarily and deliberately pitting employees against one another to drive competition, create conflict, or establish winners and losers; encouraging employees to turn against one another

- Removal of responsibility.

Removing someone’s responsibilities, changing their role, or replacing aspects of their job without cause

Removing someone’s responsibilities, changing their role, or replacing aspects of their job without cause - Impossible or changing expectations. Setting nearly impossible expectations and work guidelines; changing those expectations to set up employees to fail

- Constant change and inconsistency. Constantly changing expectations, guidelines, and scope of assignments; constant inconsistency of word and action (e.g. not following through on things said)

- Mood swings. Frequently changing moods and emotions; sharp and sudden shifts in emotions

- Criticism. Constantly criticizing someone's work or behavior, usually for unwarranted reasons

- Withholding information. Intentionally withholding information from someone or giving them the wrong information

- Projection of blame. Shifting blame to others and using them as a scapegoat; not taking responsibility for problems or issues

- Taking credit.

Taking or stealing credit for other people’s ideas and contributions without acknowledging them

Taking or stealing credit for other people’s ideas and contributions without acknowledging them - Seduction. Using excessive flattery and compliments to get people to trust them, lower their defenses, and be more responsive to manipulative behavior

- Creating a feeling of uselessness. Making an employee feel underused; intentionally rarely delegating or communicating with the employee about their work or progress; persistently giving employees unfavorable duties and responsibilities

Not-So-Subtle Signs of Bullying

Bullying can also be more obvious. These signs tend to be more commonly associated with bullying.

- Aggression. Yelling or shouting at an employee; exhibiting anger or aggression verbally or non-verbally (e.g. pounding a desk)

- Intrusion. Tampering with someone’s personal belongings; intruding on someone by unnecessarily lurking around their desk; stalking, spying, or pestering someone

- Coercion.

Aggressively forcing or persuading someone to say or do things against their will or better judgment

Aggressively forcing or persuading someone to say or do things against their will or better judgment - Punishment. Undeservedly punishing an employee with physical discipline, psychologically through passive aggression, or emotionally through isolation

- Belittling. Persistently disparaging someone or their opinions, ideas, work, or personal circumstances in an undeserving manner

- Embarrassment. Embarrassing, degrading, or humiliating an employee publically in front of others

- Revenge. Acting vindictive towards someone; seeking unfair revenge when a mistake happens; retaliating against an employee

- Threats. Threatening unwarranted punishment, discipline, termination, and/or physical, emotional, or psychological abuse

- Offensive communication. Communicating offensively by using profanity, demeaning jokes, untrue rumors or gossip, or harassment

- Campaigning.

Launching an overt or underhanded campaign to “oust” a person out of their job or the organization

Launching an overt or underhanded campaign to “oust” a person out of their job or the organization - Blocking advancement or growth. Impeding an employee’s progression, growth, and/or advancement in the organization unfairly

Why Bullying is so Bad

Bullying and manipulation of this nature can affect our employees physically, emotionally, and psychologically. Employees may experience a great deal of distress as a result of their perpetrator’s behavior, which can manifest itself in frustration, anger, anxiety, insomnia, inability to concentrate, performance and productivity issues, and other physical and emotional symptoms. The treatment they experience also tends to influence their lives outside of work.

Oftentimes, employees don’t recognize bullying.

Some may feel a vague discomfort at work towards their perpetrator that they cannot recognize. Others may feel that they are on an emotional rollercoaster with the person. Some may sense that they are experiencing toxic, unfair, or disrespectful treatment at times, but can't understand why. Employees may dread or fear seeing the individual, not enjoy tasks or activities they liked before, and can even become physically ill from the stress of these actions.

Some may sense that they are experiencing toxic, unfair, or disrespectful treatment at times, but can't understand why. Employees may dread or fear seeing the individual, not enjoy tasks or activities they liked before, and can even become physically ill from the stress of these actions.

What HR Needs to Do

Not everyone plays fair and nice at work, so unfortunately, you need to make sure you protect your employees from disrespectful and unfair treatment in the workplace. No employee deserves to feel uncomfortable at work. Here are some steps to take.

- Create a policy. Devise a policy that protects employees from bullying behavior in the workplace. While the law doesn’t protect employees, you can.

- Establish a code of conduct. Your organization should have a code of conduct in its employee handbook, which includes respectful behavior from all employees and sets the tone for a professional work environment.

- Train managers.

Train everyone (particularly managers) on soft skills and specifically workplace bullying. Make sure they recognize the right and wrong ways to treat each other on the job. Likewise, teach managers constructive ways to drive behavior and results they want.

Train everyone (particularly managers) on soft skills and specifically workplace bullying. Make sure they recognize the right and wrong ways to treat each other on the job. Likewise, teach managers constructive ways to drive behavior and results they want. - Monitor behavior. Monitor behavior throughout the workplace. When you notice signs of bullying or manipulation, address the situation directly with the person.

- Watch controlling people. Some people who constantly talk about control and exert it should be watched closely. Most are harmless, just perfectionists trying to control results and work, but some people take control to a whole different (and harmful) level.

- Have a confidential way for employees to report a bullying problem. Create a mechanism for employees to confidentially report bullying issues in the workplace without fear or retaliation.

- Educate everyone on respect. Everyone in your workplace should be trained on and held accountable for respect.

While it sounds like common sense, respect is unfortunately lacking in many workplaces.

While it sounds like common sense, respect is unfortunately lacking in many workplaces. - Recognize employees’ distress. Look for confusion, frustration, discomfort, fear, overt emotional displays, and avoiding one’s boss, which are all signs that an employee is in distress at work and uncomfortable in their situation.

- Don’t sweep complaints under the rug. Treat every complaint about bullying behavior seriously and fairly and investigate it. Your employees need someone to trust.

- Document. Be sure to document any behavior incidents you hear about from employees or witness.

“While bullying behavior is often difficult to recognize, investigate and address, the tangible and intangible costs to the employer (e.g., financial, interpersonal, productivity) can be huge. And, left unaddressed, bullying concerns quickly can escalate. Employers need to aggressively reinforce and consistently enforce their codes of conduct and standards of professionalism through training; empowering and requiring supervisors to proactively identify issues; on site monitoring of behavior; and prompt and thorough investigations into allegations of bullying and other misconduct,” says Meg Matejkovic, Employment Attorney and ERC Trainer.

If you are an individual or manager doing any of the above, either knowingly or unknowingly, it’s critical that you stop your actions. They are harmful and destructive. If you are the coworker of an individual experiencing mistreatment, question it and tell someone. Likewise, if you are in HR, it is imperative that you take bullying seriously and follow the guidance above to protect and help your employees who may be affected by manipulative and bullying behavior.

Our employees deserve to work in a respectful, fair, and comfortable work environment where others around them, particularly those of authority, aren’t trying to control them or manipulate their behavior. It’s all of our responsibilities to make sure they leave everyday, at a minimum, with their self-respect, dignity, and well-being intact and unscathed by our actions. If they aren’t, we’re not doing our jobs and we risk good employees eventually walking away when they realize they don't need to be treated this way anymore.

Bullying in the Workplace Training

This training covers the basics of professional behavior in the workplace.

Request More Information

Muzhitskaya Tatyana Vladimirovna, Tatyana Muzhitskaya: Signs of the universe. 40 hooligan cards that will help you look into the future

SKU: p6044648

Bought 357 times

- 18th place in the Esoteric category. Parapsychology

All ratings

About the product

The universe always answers if you ask it a question. True, sometimes quite abruptly. If you're the kind of person who isn't afraid to get an answer too straight forward, this deck is for you!

Made on the principle of metaphorical cards, a deck of hooligan cards by Tatyana Muzhitskaya can help you find a solution when you are in doubt about what to do next or whether you are on the right path. Tatyana collected these signs all over the country so that now you can relax and talk with the Universe. A graffiti on a wall, a t-shirt, a random advertising slogan, the Universe has many ways to give you a sign.

A graffiti on a wall, a t-shirt, a random advertising slogan, the Universe has many ways to give you a sign.

How to use the deck:

• Think about what is very important to you at the moment and ask the Universe a question.

• Shuffle the deck and draw one card.

• Look at the map and listen to your very first impressions.

• Tie together your thoughts and feelings and give the answer to yourself.

Contents: 39 cards + instructions.

- Tarot cards

- Secrets of the future

- Interpretation of fate

Characteristics0002

13 kg

13 kg Give up to 50 bonuses for a review

Daria Zakatova