Infant attachment styles

Infant-parent attachment: Definition, types, antecedents, measurement and outcome

1. Dozier M, Stovall KC, Albus KA. Attachment and psychopathology in adulthood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 497–519. [Google Scholar]

2. Green J, Goldwyn R. Annotation: attachment disorganisation and psychopathology: new findings in attachment research and their potential implications for developmental psychopathology in childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2002;43:835–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Greenberg MT. Attachment and psychopathology in childhood. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 469–98. [Google Scholar]

4. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. Volume 1: Attachment. 2nd edn. New York: Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

5. Waters E, Cummings EM. A secure base from which to explore close relationships. Child Dev. 2000;71:164–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Klaus MH, Kennell JH. Maternal-Infant Bonding: The Impact of Early Separation or Loss on Family Development. St Louis: Mosby; 1976. [Google Scholar]

7. Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MD, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of Attachment. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

8. Sroufe LA. The role of infant-caregiver attachments in development. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical Implications of Attachment. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

9. van IJzendoorn MH, Schuengel C, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants and sequelae. Dev Psychopathol. 1999;11:225–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Lyons-Ruth K, Bronfman E, Atwood G. A relational diathesis model of hostile-helpless states of mind: Expressions in mother-infant interactions. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment Disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 33–70. [Google Scholar]

11. Schuengel C, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Blom M. Unresolved loss and infant disorganization: Links to frightening maternal behavior. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment Disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

Unresolved loss and infant disorganization: Links to frightening maternal behavior. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment Disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

12. Zeanah CH, Danis B, Hirshberg L, Benoit D, Miller D, Heller SS. Disorganized attachment associated with partner violence: A research note. Infant Ment Health J. 1999;20:77–86. [Google Scholar]

13. Main M, Solomon J. Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In: Brazelton TB, Yogman MW, editors. Affective Development in Infancy. Norwood: Ablex; 1986. pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

14. Main M, Solomon J. Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In: Greenberg MT, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the Preschool Years. Chicago: University Press; 1990. pp. 121–60. [Google Scholar]

15. Main M, Hesse E. Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening behavior the linking mechanism? In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the Preschool Years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 161–82. [Google Scholar]

Attachment in the Preschool Years. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 161–82. [Google Scholar]

16. Egeland B, Hiester M. The long-term consequences of infant day-care and mother-infant attachment. Child Dev. 1995;66:474–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. van IJzendoorn MH, Sagi A, Lambermon MWE. The multiple caretaker paradox: Data from Holland and Israel. In: Pianta RC, editor. New Directions for Child Development No 57 Beyond the Parent: The role of Other Adults in Children’s Lives. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1992. pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

18. Boris NW, Fueyo M, Zeanah CH. Clinical assessment of attachment in children under five. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:291–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Carlson EA. A prospective longitudinal study of attachment disorganized/disoriented. Child Dev. 1998;69:1107–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Lyons-Ruth K, Block D. The disturbed caregiving system: Relations among childhood trauma, maternal caregiving and infant affect and attachment. Infant Ment Health J. 1996;17:257–75. [Google Scholar]

Infant Ment Health J. 1996;17:257–75. [Google Scholar]

21. Lyons-Ruth K, Alpern L, Repacholi B. Disorganized infant attachment classification and maternal psychosocial problems as predictors of hostile-aggressive behavior in the preschool classroom. Child Dev. 1993;64:572–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Main M, Cassidy J. Categories of response to reunion with the caregiver at age six: Predictable from infant attachment classifications and stable over a one-month period. Dev Psychopathol. 1988;24:415–26. [Google Scholar]

23. Main M, Morgan H. Disorganization and disorientation in infant strange situation behavior: Phenotypic resemblance to dissociative states? In: Michelson LK, Ray WJ, editors. Handbook of Dissociation: Theoretical, Empirical and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 107–38. [Google Scholar]

24. Zeanah CH, Boris NW, Larrieu JA. Infant development and developmental risk: A review of the past 10 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:165–78. Erratum in: 1998;37:240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1997;36:165–78. Erratum in: 1998;37:240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Hertsgaard L, Gunnar M, Erickson MF, Nachmias M. Adrenocortical responses to the strange situation in infants with disorganized/disoriented attachment relationships. Child Dev. 1995;66:1100–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Splanger G, Grossmann KE. Biobehavioral organization in securely and insecurely attached infants. Child Dev. 1993;64:1439–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M. The role of attachment in the early development of disruptive behavior problems. Dev Psychopathol. 1993;3:413–30. [Google Scholar]

28. Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Lyons-Ruth K, Easterbrooks MA, Cibelli CD. Infant attachment strategies, infant mental lag, and maternal depressive symptoms: Predictors of internalizing and externalizing problems at age 7. Dev Psychol. 1997;33:681–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dev Psychol. 1997;33:681–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Solomon J, George C, De Jong A. Children classified as controlling at age six: Evidence of disorganized representational strategies and aggression at home and at school. Dev Psychopathol. 1995;7:447–63. [Google Scholar]

31. Speltz ML, Greenberg MT, Deklyen M. Attachment in preschoolers with disruptive behavior: A comparison of clinic-referred and nonproblem children. Dev Psychopathol. 1990;2:31–46. [Google Scholar]

32. Cicchetti D, Barnett D. Attachment organization in maltreated pre-schoolers. Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:397–411. [Google Scholar]

33. Lyons-Ruth K, Connell D, Zoll D, Stahl J. Infants at social risk: Relations among infant maltreatment, maternal behavior, and infant attachment behavior. Dev Psychol. 1987;23:223–32. [Google Scholar]

34. Lyons-Ruth K, Repacholi B, McLeod S, Silva E. Disorganized attachment behavior in infancy: Short-term stability, maternal and infant correlates, and risk-related subtypes. Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:377–96. [Google Scholar]

Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:377–96. [Google Scholar]

35. Shaw DS, Vondra JI. Infant attachment security and maternal predictors of early behavior problems: A longitudinal study of low-income families. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;23:335–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Lyons-Ruth K, Jacobvitz D. Attachment disorganization: Unresolved loss, relational violence and lapses in behavioral and attentional strategies. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of Attachment. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 520–54. [Google Scholar]

37. Jacobvitz D, Hazan N. Developmental pathways from infant disorganization to childhood peer relationships. In: Solomon J, George C, editors. Attachment Disorganization. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

38. Greenberg MT, Speltz ML, Deklyen M, Endriga MC. Attachment security in pre-schoolers with and without externalizing problems: A replication. Dev Psychopathol. 1991;3:413–30. [Google Scholar]

39. Moss E, Rousseau D, Parent S, St-Laurent D, Saintonge J. Correlates of attachment at school age: Maternal reported stress, mother-child interaction, and behavior problems. Child Dev. 1998;69:1390–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Correlates of attachment at school age: Maternal reported stress, mother-child interaction, and behavior problems. Child Dev. 1998;69:1390–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Goldwyn R, Stanley C, Smith V, Green JM. The Manchester Child Attachment Story Task: Relationship with parental AAI, SAT and child behavior. Attach Hum Dev. 2000;2:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Cassidy J. Child-mother attachment and the self in six-year-olds. Child Dev. 1988;59:121–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Verschueren K, Marcoen A. Representation of self and socioemotional competence in kindergartners: Differential and combined effects of attachment to mother and to father. Child Dev. 1999;70:183–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Verschueren K. Narratives in attachment research. Biennial meeting of the European Society of Developmental Psychology; Uppsala. 2001. [Google Scholar]

44. Jacobsen T, Edelstein W, Hofmann V. A longitudinal study of the relation between representations of attachment in childhood and cognitive functioning in childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychol. 1994;30:112–24. [Google Scholar]

Dev Psychol. 1994;30:112–24. [Google Scholar]

45. Hesse E, van IJzendoorn MH. Parental loss of close family members and propensities towards absorption in offspring. Dev Sci. 1998;1:299–305. [Google Scholar]

46. World Health Organization . International Classification of Diseases: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. 10th edn. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

47. American Psychiatric Association Diagnositic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th edn(DSM-IV)Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

48. Zeanah CH, Mammen OK, Lieberman AF. Disorders of Attachment Handbook of Infant Mental Health. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 332–49. [Google Scholar]

49. Zeanah CH, Boris NW. Disturbances and Disorders of Attachment in Early Childhood Handbook of Infant Mental Health. 2nd edn. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 358–81. [Google Scholar]

50. Ferber R. Solve Your Child’s Sleep Problems. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1985. [Google Scholar]

New York: Simon & Schuster; 1985. [Google Scholar]

The Four Types & Why They Matter – BabySparks

Parenting questions?

An expert-led class is just a click away

Browse Classes

Starting from 9.99$/mo (billed annually)

Unlimited live and on-demand classes & activities

New classes added every month.

A baby is upset and letting the world know through a bout of crying. Wow, a completely rare occurrence, right? What the baby’s caregiver does next is key to how she will relate to the world as she grows.

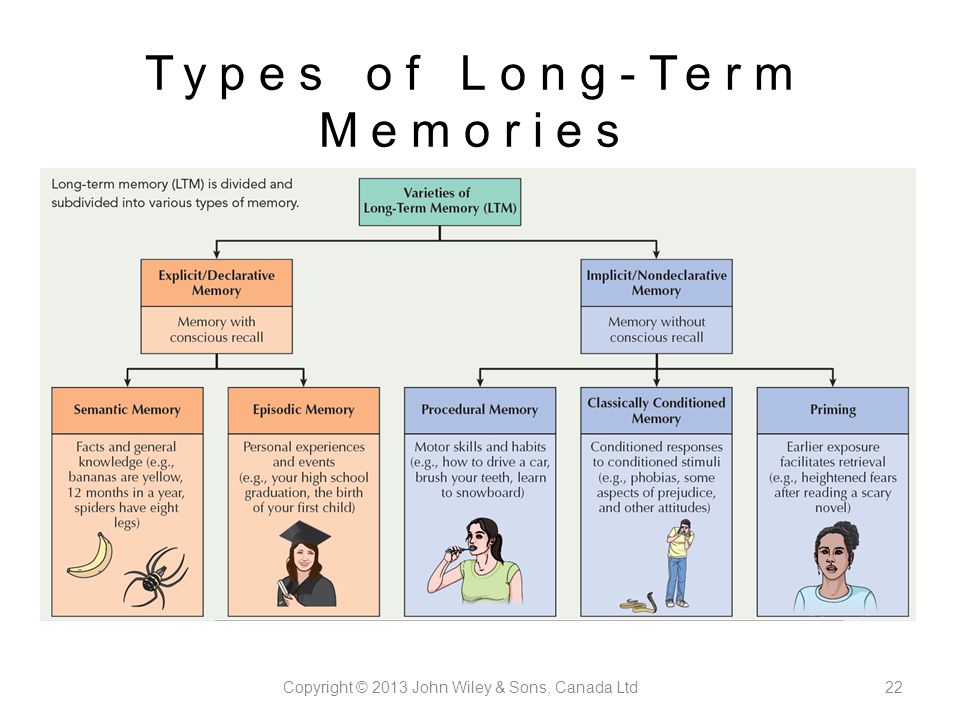

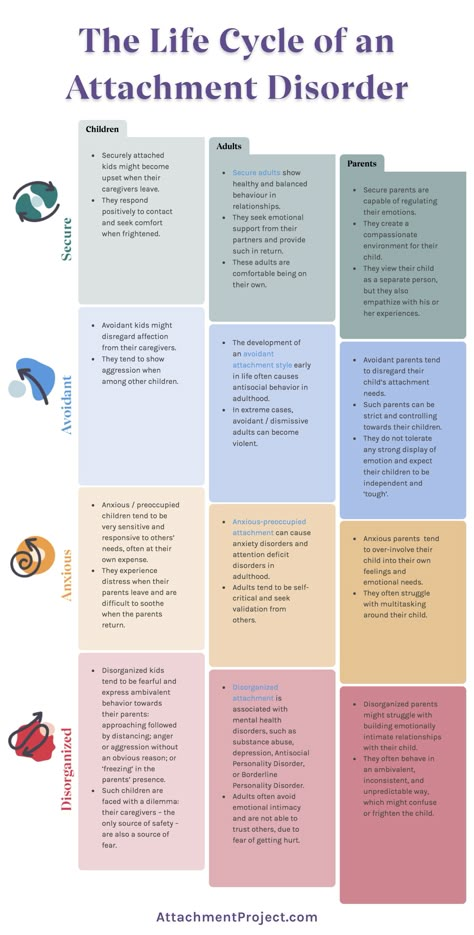

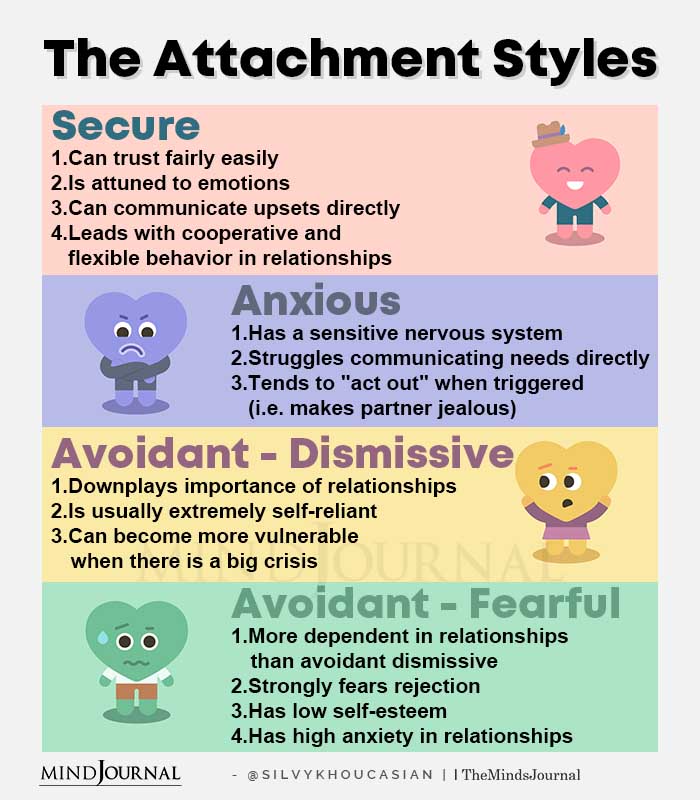

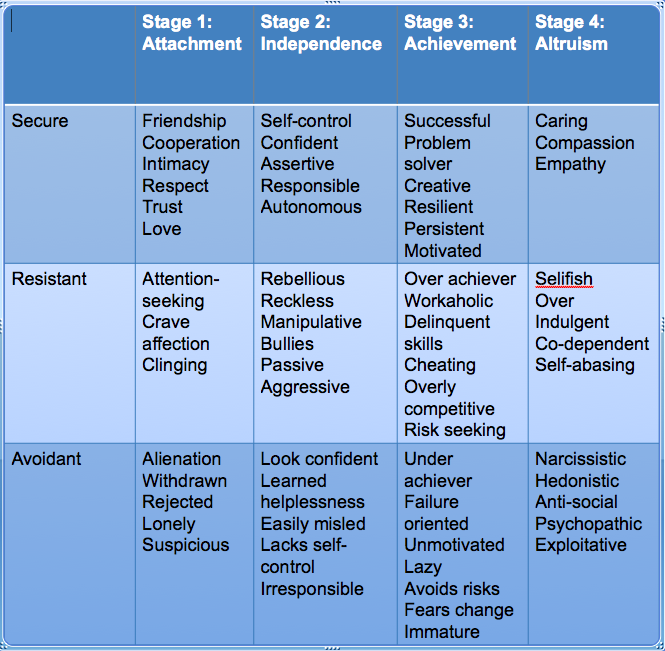

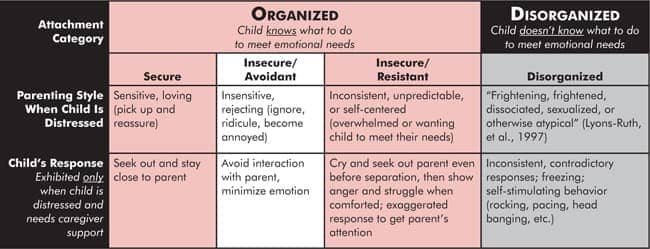

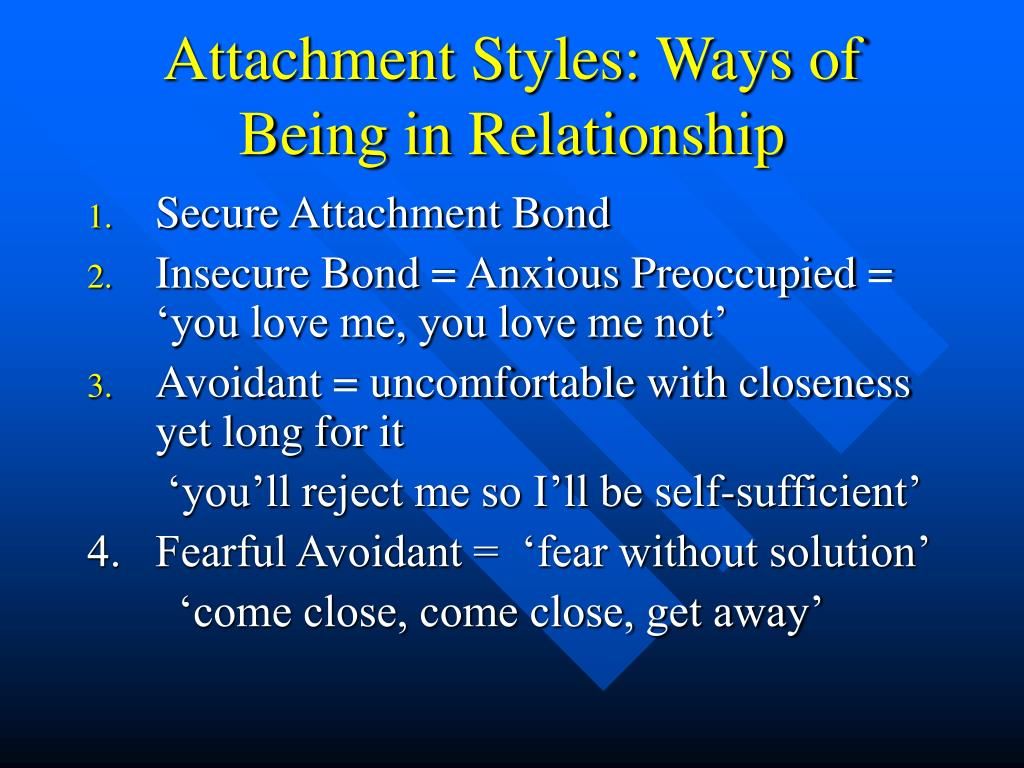

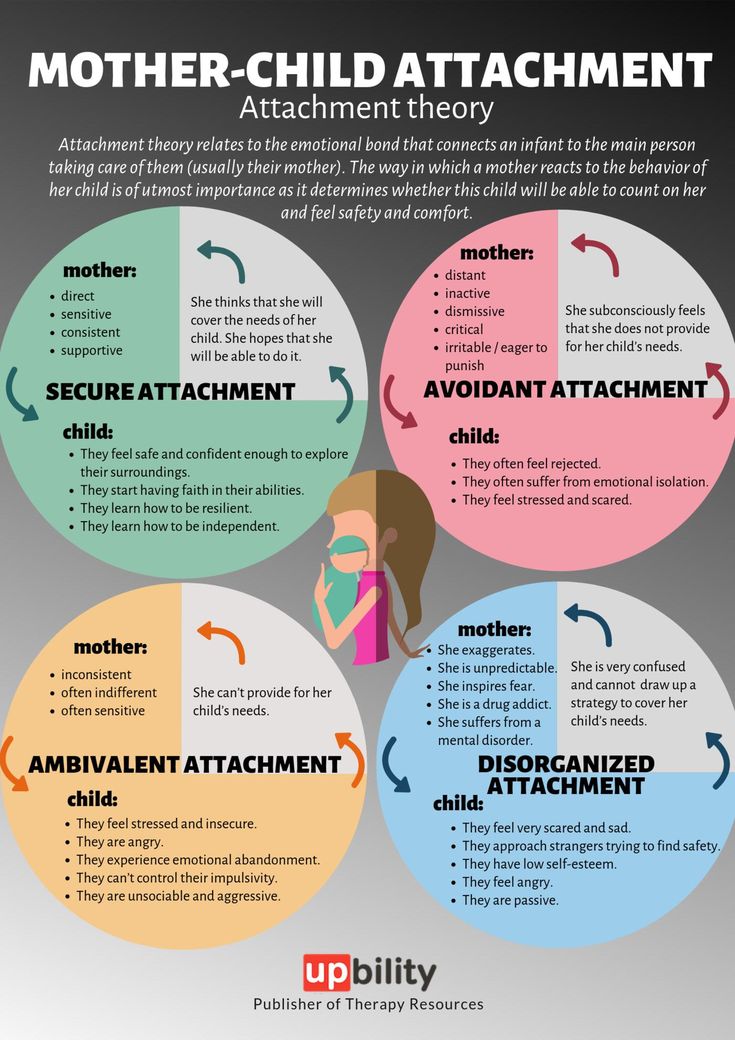

We’ve entered the realm of infant-parent attachment theory, which looks at whether a child feels safe, secure, and protected with a parent or caregiver. Some form of attachment will happen with a caregiver—it’s just a matter of quality. Attachment theory has established four types of attachment: secure, avoidant, ambivalent, and disorganized.

Studies have shown that how a child first attaches to her caregivers has a lasting impact on how she relates to other people as she gets older.

| Highlights:

|

Four Types of Attachment

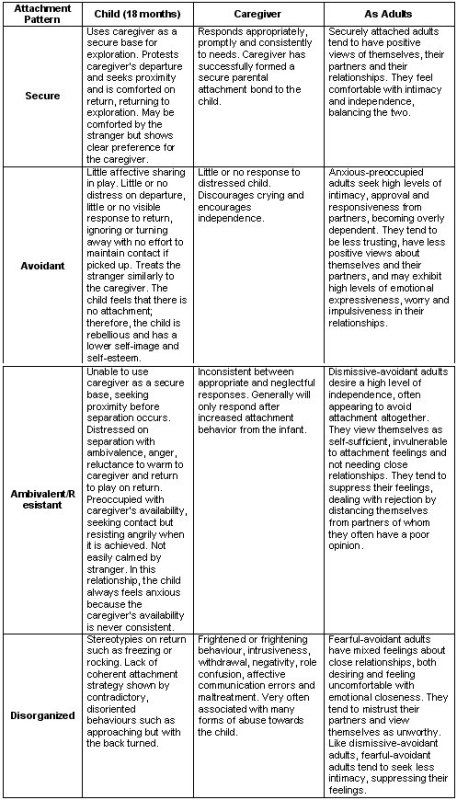

To illustrate the four types of attachment—and their consequences—let’s take a look at the different reactions a child can have as determined in research performed by Mary Ainsworth. Ainsworth’s experiments involved leaving a child alone as well as with a stranger and having an observer write down the child’s reactions.

Sam (Secure)

Sam has been fine with a stranger in the room until his mother leaves, because he is able to look back at her to make sure it’s safe to explore. Now that his mother has left the room, he is agitated and staying away from the stranger. When his mother comes back, he is delighted. This is because when he has shown uncertainty and concern in the past, his mother has responded comfortingly and consistently.

Anne (Avoidant)

Anne is upset upon seeing the stranger in the room and avoids interactions with her. But when her father leaves for a bit and then comes back again, Anne avoids him as well and fails to cling to him when he picks Anne up. This is because when she has shown uncertainty and concern, her father has ignored or been annoyed by the behavior, making Anne less likely to bother to seek comfort from him.

This is because when she has shown uncertainty and concern, her father has ignored or been annoyed by the behavior, making Anne less likely to bother to seek comfort from him.

Allen (Ambivalent)

When Allen sees the stranger, he clings to his mother and then pushes her away. He shows a similar back-and-forth pattern when his mother comes back to the room after leaving for a bit. This is because when he has shown uncertainty or concern, his mother has been inconsistent—sometimes caring, sometimes annoyed. Thus, his reactions to her are equally inconsistent.

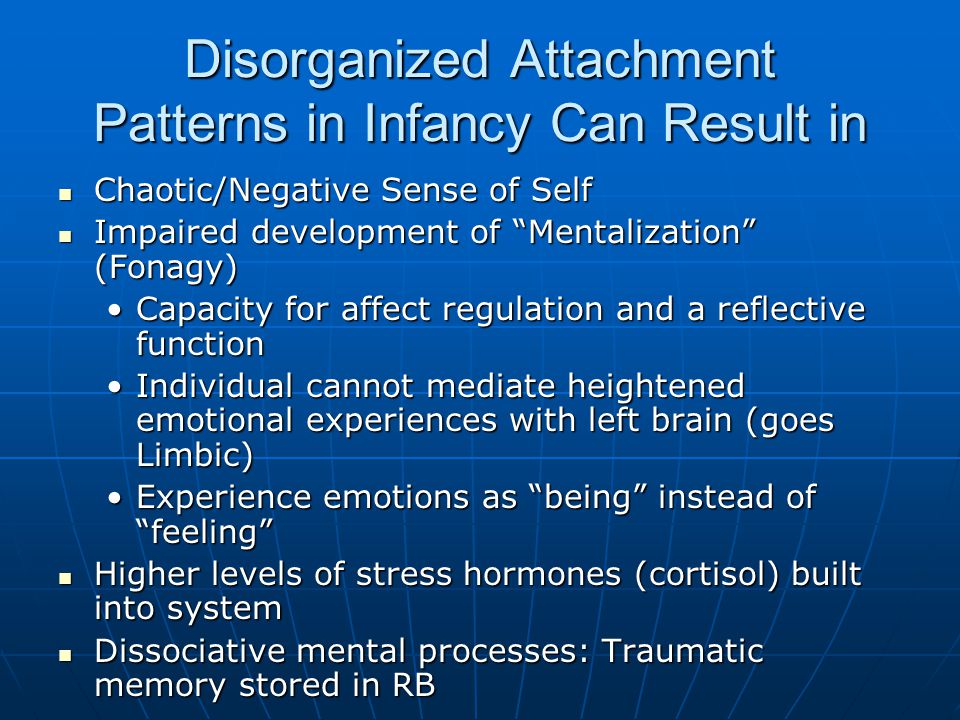

Debby (Disorganized)

Debby avoids interacting with others and becomes extremely fearful at times, which doesn’t change whether her father is in the room with her or not. This is because when she has shown uncertainty or concern, her father has neglected her, so she has come to the conclusion that she can’t depend on anyone.

When is Attachment Established?

The phases of attachment are:

Preattachment—from birth to about 6 weeks of age: An infant’s attachment to a caregiver is just beginning, so they are okay being left with strangers.

Attachment in the making—from 6 weeks to 6-8 months of age: An infant will react differently to a caregiver than to strangers but is still normally okay being left with strangers.

Clear-cut attachment—from 6-8 months of age to 18 months of age: When separated from a caregiver, an infant will start fussing. Attachment is in place!

Formation of reciprocal relationship—from 18 months to 2 years: An infant is starting to grasp the concept of a caregiver’s coming and going, so let the negotiations begin —“Just one more story?”

The Consequences of Secure versus Insecure Attachment

The many benefits of secure attachment are integral to a healthy life. They include, among others:

• More autonomy

• More willingness to explore

• More playfulness

• More successful interaction with their peers

• Less conflict with their parents

• Less aggression

• Less anxiety

And they end up being more responsive parents themselves. Secure attachment is a gift to future generations!

Secure attachment is a gift to future generations!

As for those infants who form insecure attachments, low self-esteem is common, and they are more likely to exhibit anxiety, depression, and withdrawal. In interactions with others, they may be more aggressive.

What This Means for You

Of course steps can be taken in the future to help Anne, Allen, and Debby find the ability to form trusting and secure relationships, but it can be a difficult path. So if you want to help your child form a secure attachment like Sam did, here’s help to set her on the road toward a healthy relationship with you and others.

BabySparks

4 Styles of Attachment - Institute for Family Development

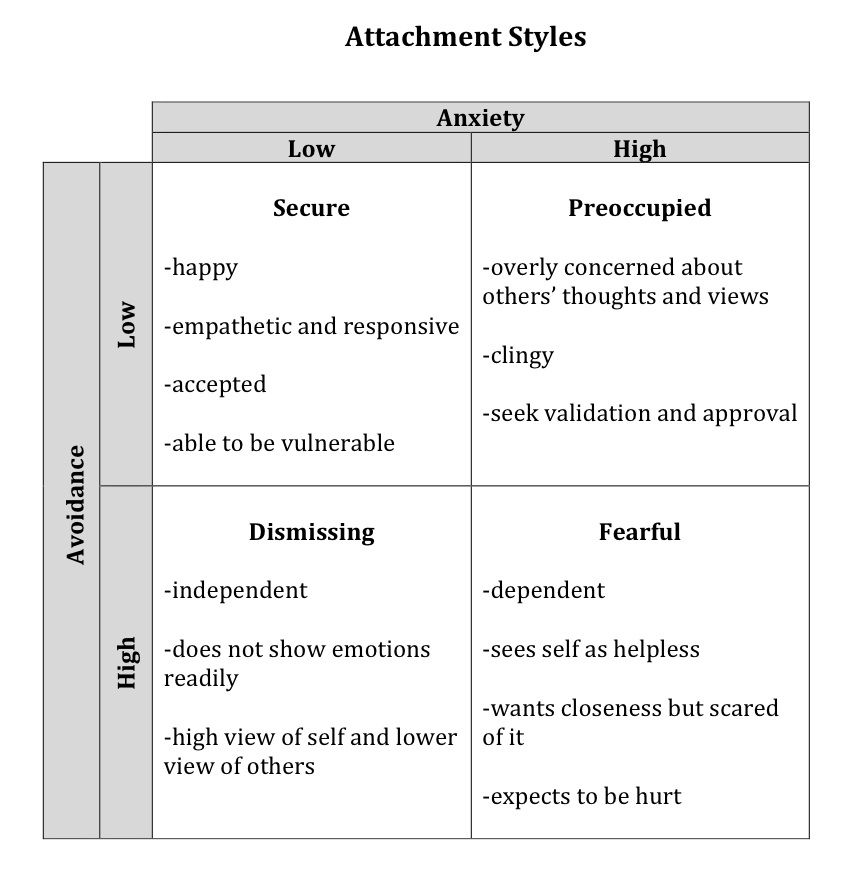

Does your partner avoid intimacy? On the contrary, obsessive? Or perhaps inconsistent and unpredictable? Or is he reliable, gentle, and relationships with him bring peace and satisfaction? One approach to explaining the reasons for such behavior is to determine the attachment style that a person developed in childhood.

We continue to introduce you to psychologists who have studied attachment. It's about Mary Ainsworth. It was she who described 4 styles of attachment.

Born in the USA in 1913, Mary Ainsworth is one of the 100 most influential psychologists of the 20th century. Ainsworth is an American-Canadian scientist who worked, among other things, with John Bowlby. Ainsworth expanded his attachment theory substantially in the 1970s. Her innovation is especially evident in the development of a method for assessing attachment in infants aged one to one and a half years to a significant adult - the so-called "Strange Situation" procedure

During the procedure, the mother and child are placed in an unfamiliar playroom with toys. At the same time, the researcher observes them through a one-way mirror. The procedure consists of eight successive stages in which the child experiences a short-term separation from and reunion with the mother, as well as the presence of an unfamiliar adult. (here is an example on the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU)

(here is an example on the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU)

Based on the children's reactions during the experiment, Ainsworth described three main attachment styles: secure, anxious, and avoidant. Ainsworth's colleague, Mary Maine, later described a fourth as disorganized.

RELIABLE. In the experiment, after the departure of the mother, the child is upset, but quickly calms down when she appears, calmly interacts with strangers in the presence of the mother, looks at the mother during the game and smiles, is proactive and inquisitive.

Secure attachment is formed in children who grow up in close-knit families, where parents constantly maintain emotional contact with their children. The parent is available and able to meet the needs of the child in an appropriate way. Securely attached children feel secure and are more likely to explore their environment.

In adulthood, securely attached people do not alienate their loved ones and become dependent on them. They trust loved ones, feel worthy of love, respect a partner and are ready to seek a compromise. Of course, such people also have problems in relationships, but their cause should not be sought in childhood. The secure type is considered the most adaptive attachment style.

They trust loved ones, feel worthy of love, respect a partner and are ready to seek a compromise. Of course, such people also have problems in relationships, but their cause should not be sought in childhood. The secure type is considered the most adaptive attachment style.

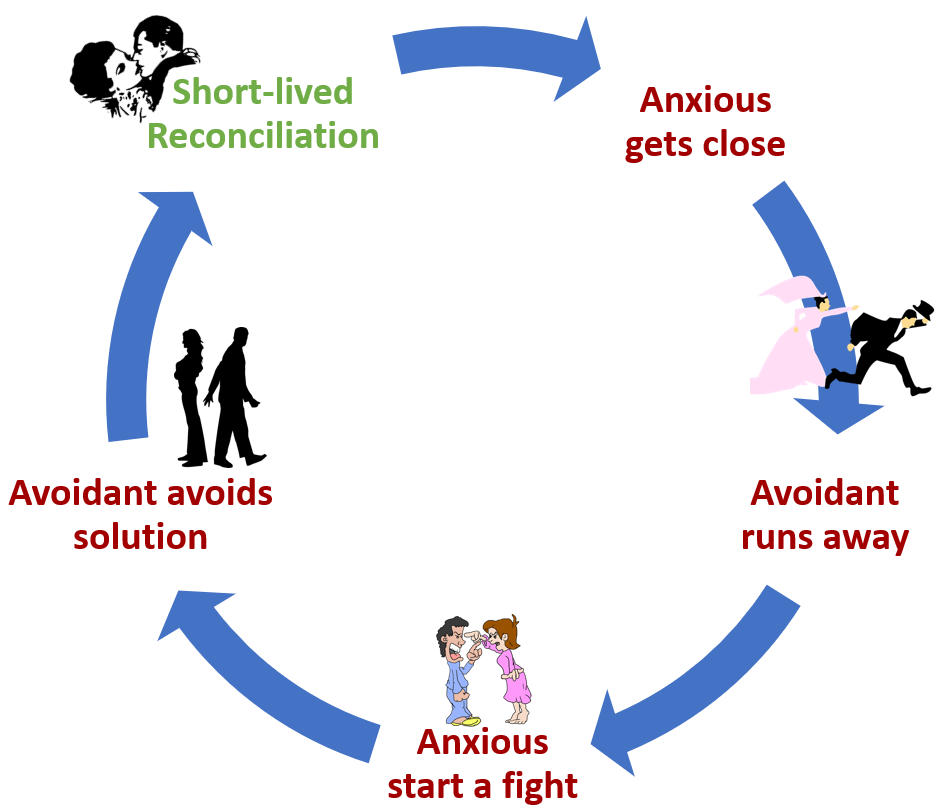

ANXIETY attachment is manifested in the strong grief of the child after the departure of the mother, crying, hysterics, which do not stop even after her return. Sometimes aggression towards the mother is manifested, refusal to communicate with strangers. The child explores little, is wary of strangers, even in the presence of a parent.

Anxious attachment is a consequence of the adult's inconsistent behavior, his anxiety about initiatives or the child's health. This type of attachment is formed when parents are unpredictable. They either allow or forbid. Either nearby or not. And the child begins to cling to them, so as not to lose.

People with this type of attachment have low self-esteem. They are dependent, react painfully to changes in relationships, are afraid to be alone and therefore constantly require confirmation of love.

AVOIDING attachment manifests itself in the child's indifference to the care of the mother, the absence of fear of strangers, a low level of initiative and response behavior. Ainsworth suggested that the deadpan behavior of infants is a disguise for grief. This happens when the child's needs have not been taken into account, and he comes to the conclusion that the satisfaction of his needs does not matter to the significant adult.

Avoidant attachment is formed when a child has experienced attachment denial, when parents reject the child, do not respond to his needs, do not support him emotionally, or when prohibitive forms of upbringing prevail.

Then a person in adult life usually avoids close relationships, keeps a partner at a distance, and also, as a rule, hides his feelings. Moreover, despite the closed behavior, such a person really needs relationships and support. Without them, he feels lonely.

DISORIENTED attachment is expressed in the absence of connection of behavior with the stages of achieving intimacy. Such attachment includes overt manifestations of fear; conflicting behaviour. Children may run to hide when they see a significant adult, or exhibit avoidant or ambivalent strategies when reunited with a parent. This is an indication that the attachment system has been disturbed (for example, by fear or anger)

Such attachment includes overt manifestations of fear; conflicting behaviour. Children may run to hide when they see a significant adult, or exhibit avoidant or ambivalent strategies when reunited with a parent. This is an indication that the attachment system has been disturbed (for example, by fear or anger)

Disoriented attachment is often formed in families where the child is exposed to violence. These children break the rules of human relations by forgoing attachment in favor of power: they don't need to be loved, they prefer to be feared. Their behavior is inconsistent and often change. A person with a disoriented sense of attachment can seek a relationship for a long time, and having achieved it, immediately drop everything and break it off.

***

According to Ainsworth, attachment style is not so much a part of a child's thinking as a characteristic feature of relationships. A child may have a different type of attachment to each of the parents, as well as to any significant adult. However, after about five years of age, children tend to show one consistent pattern of attachment in a relationship.

However, after about five years of age, children tend to show one consistent pattern of attachment in a relationship.

Although attachment style in infancy will not necessarily become the leading attachment style in adulthood, it does have an impact on later intimacy. Insecure attachment styles negatively impact behavior both in childhood and later in life. People with secure attachments are more likely to have adequate self-esteem, independence, strong romantic relationships and self-presentation confidence, and experience less depression and anxiety.

how to adjust your own parenting habits based on your child's attachment style

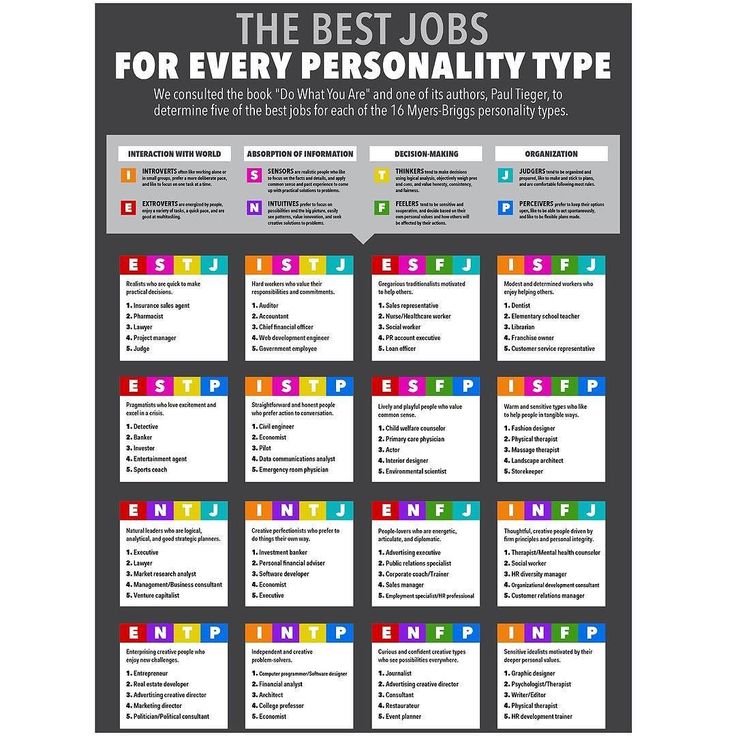

Ronald Stolberg, Ph.D., clinical psychologist and professor at the California School of Professional Psychology at International University, notes that an important component of parenting is the development of a secure attachment style between parent and child. His understanding helps to determine the style of behavior of the father and mother in communicating with their offspring. And matching a child's temperament to a particular learning style can improve school outcomes.

And matching a child's temperament to a particular learning style can improve school outcomes.

John Bowlby's experiment

Attachment theory began with the research of British psychologist John Bowlby. One of them involved children aged 12 to 18 months. A situation was created in which children were briefly separated from their parents and then reunited with them. The scientist called it "a strange situation."

By observing hundreds of similar scenarios, his team was able to identify three basic styles of attachment. The fourth was introduced and widely accepted decades later, including with the participation of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget.

Four types of childhood attachments

They include:

"We stormed Elbrus on an empty stomach": Etush's memories of the war

Studies show that distance learning students do not sleep longer

"The soldiers could not see enough of us" : a love story of a veteran and a nurse

- Ambivalent affection.

It is characterized by a state of distress, that is, the suffering associated with separation from the parent. This is because there was no consistency in the upbringing of these children, so they are not sure that their parents will always be there when needed.

It is characterized by a state of distress, that is, the suffering associated with separation from the parent. This is because there was no consistency in the upbringing of these children, so they are not sure that their parents will always be there when needed. - Avoidant attachment. It is observed in children who tend to avoid parents and to a small extent show preference for father and mother over strangers when they need comfort. It is assumed that in such boys and girls this style is formed as a result of a casual approach to their upbringing, in which their needs are not met, but ignored.

- Unorganized affection. When present, children feel confused and inconsistent when they are separated from their parents. According to researchers, this is a consequence of inconsistent upbringing, when parents sometimes show warmth and affection, and sometimes neglect children, becoming inaccessible to them.

- Secure attachment. It is desirable for all children. It is observed when children demonstrate confidence that their separation from their father or mother will not be long, and reunion brings joy and happiness.

This is because it has always been so in the past, these children have always been surrounded by warmth and care.

This is because it has always been so in the past, these children have always been surrounded by warmth and care.

One of the reasons why it is so important to form a secure attachment between children and parents is that its absence affects the rest of life in a negative way, including personal relationships with a partner and the need to care for one's own children.

Ingenuity Mars Helicopter Set Speed Record: What More Can You Expect? How to test her for palm oil at home

Transportation and the parade schedule: how to celebrate Victory Day in Moscow

New research

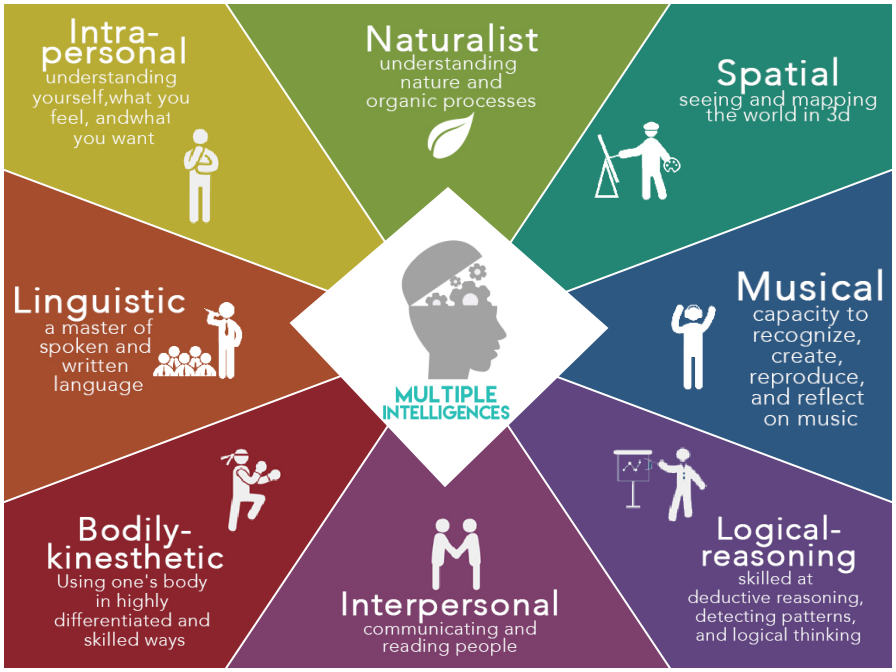

An interesting addition to the conversation about attachment styles of children and caregivers is the study by Thomas and Chess, who found that the formation of personality The child is affected by nine characteristics of temperament, including such as the level of activity, adaptability and perseverance.

Researchers have found that most children fall into one of the following three categories: easy, difficult, and slow to adjust.