Autism obsessions list

Obsessions and repetitive behaviour - a guide for all audiences

Intense interests and repetitive behaviour can be a source of enjoyment for autistic people and a way of coping with everyday life. But they may be obsessions and limit people's involvement in other activities and cause distress or anxiety. Find out what you can do to help.

Intense interests

“My mind was constantly whirring with thoughts, worries and concerns. The time spent with my intense interest was the only time in which I had a clear mind – it gave me that much sought-after relaxation.” Autistic young person

Many autistic people have intense and highly-focused interests, often from a fairly young age. These can change over time or be lifelong. It can be art, music, gardening, animals, postcodes or numbers. For many younger children it's Thomas the Tank Engine, dinosaurs or particular cartoon characters.

Autistic people might also become attached to objects (or parts of objects), such as toys, figurines or model cars – or more unusual objects like milk bottle tops, stones or shoes. An interest in collecting is also quite common.

Autistic people often report that the pursuit of such interests is fundamental to their wellbeing and happiness, and many channel their interest into studying, paid work, volunteering, or other meaningful occupations. The interest can:

- provide structure, order and predictability, and help people manage the uncertainties of daily life

- give someone a way to start conversations and feel more self-assured in social situations

- help someone to relax and feel happy.

Is it an obsession or a hobby?

It is the intensity and duration of a person's interest in a particular topic, object, or collection that marks it out as an obsession.

- Is the person unable to stop the activity/interest independently?

- Is the interest impacting on the person's learning?

- Is the interest limiting the person's social opportunities?

- Is the interest causing significant disruption to other people, eg parents, carers and family?

If your answer to any of the questions above is 'yes', then their interest may have become an obsession which is affecting them, you and/or other people in their life.

Repetitive behaviour

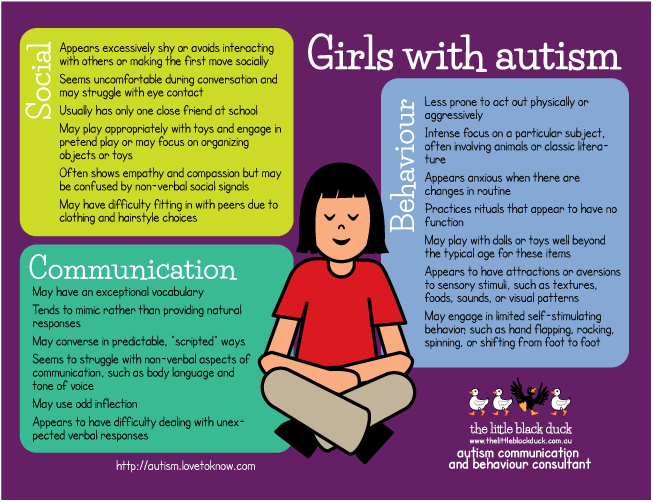

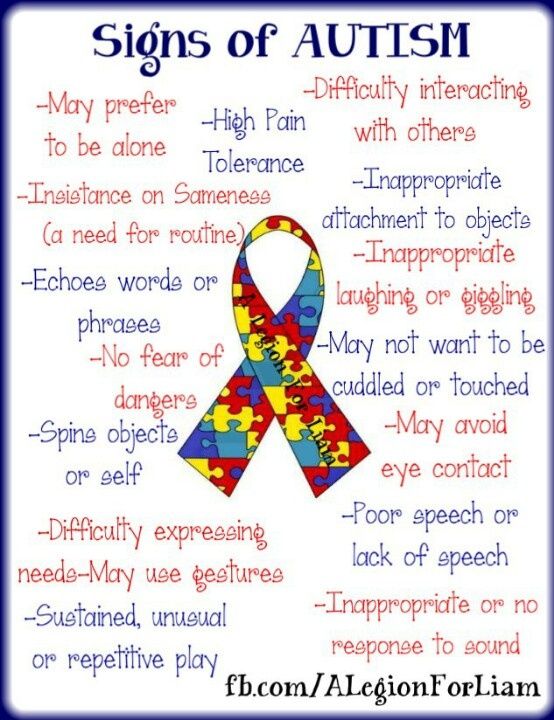

Repetitive behaviour may include arm or hand-flapping, finger-flicking, rocking, jumping, spinning or twirling, head-banging and complex body movements. This is known as 'stimming' or self-stimulating behaviour.

The reasons behind it include:

- for enjoyment

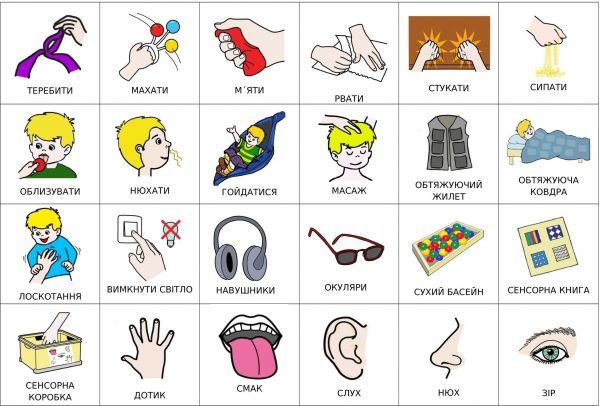

- an attempt to gain sensory input, eg rocking may be a way to stimulate the balance (vestibular) system; hand-flapping may provide visual stimulation

- an attempt to reduce sensory input, eg focusing on one particular sound may reduce the impact of a loud, distressing environment; this may particularly be seen in social situations

- to deal with stress and anxiety and to block out uncertainty.

Ask yourself if the repetitive behaviour restricts the person's opportunities, causes distress or discomfort, or impacts on learning?

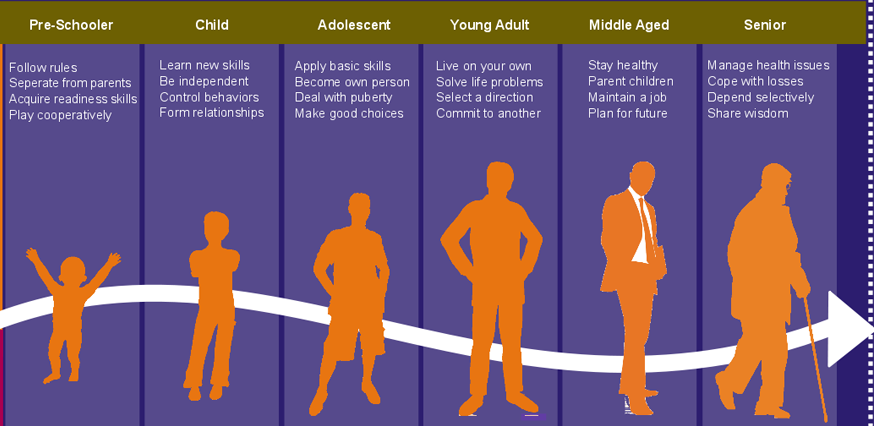

For instance, a behaviour that is perhaps acceptable in a young child may not be appropriate as they get older, eg stroking other people's hair, copying people's accents, or collecting shiny things - meaning they collect change that people leave around. If it is causing difficulties, or is in some way unsafe, they may need support to stop or change the behaviour, or reduce their reliance on it.

Strategies to use

Understand the function of the behaviour

Think about the function of the repetitive behaviour or obsession. What does the person get out of it? Does it reduce anxiety, or block out noise?

What does the person get out of it? Does it reduce anxiety, or block out noise?

Modify the environment

Does the person always seem to find a particular place like a classroom, hard to cope with? Is it too bright? You might find that modifying the environment (eg turning off strip lighting) can help to reduce sensory discomfort. If the behaviour is a way of getting sensory input, look for alternative ways of achieving the same sensation.

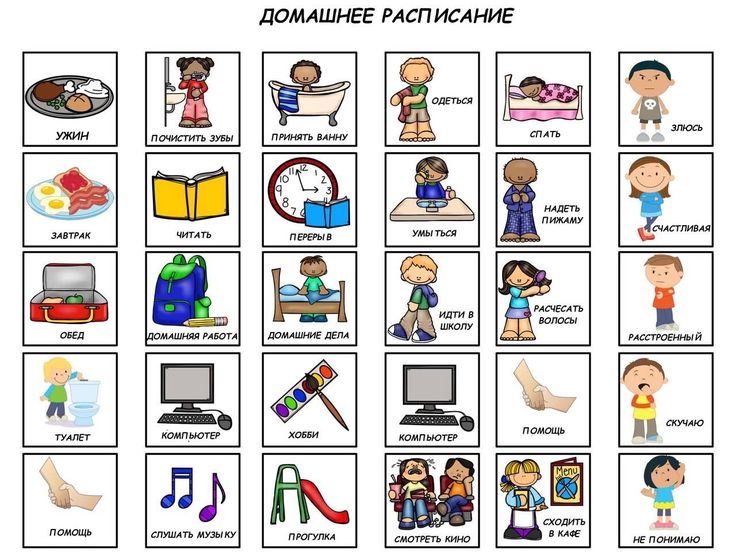

Increase structure

Make the world a more structured and predictable place. A more structured environment could reduce boredom, which is sometimes a reason for repetitive behaviour. You might prepare a range of enjoyable or calming activities to re-direct the person to if they seem bored or stressed.

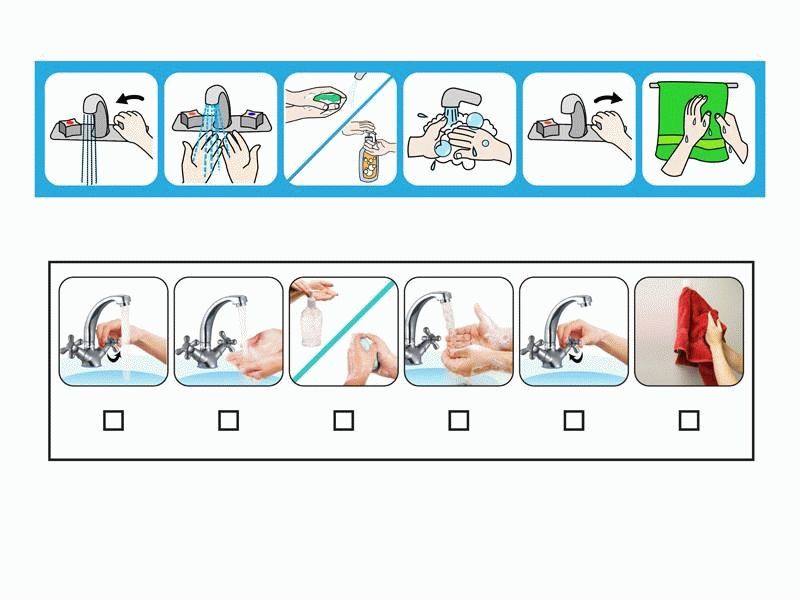

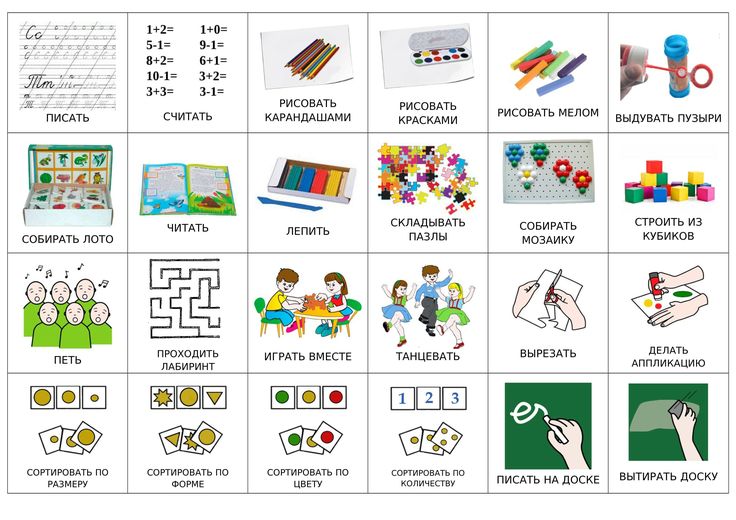

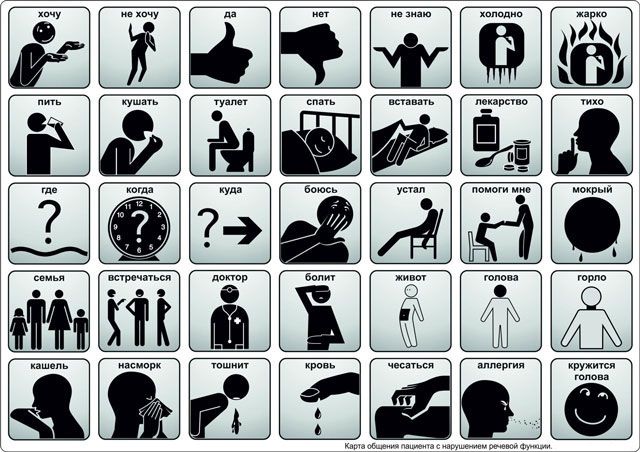

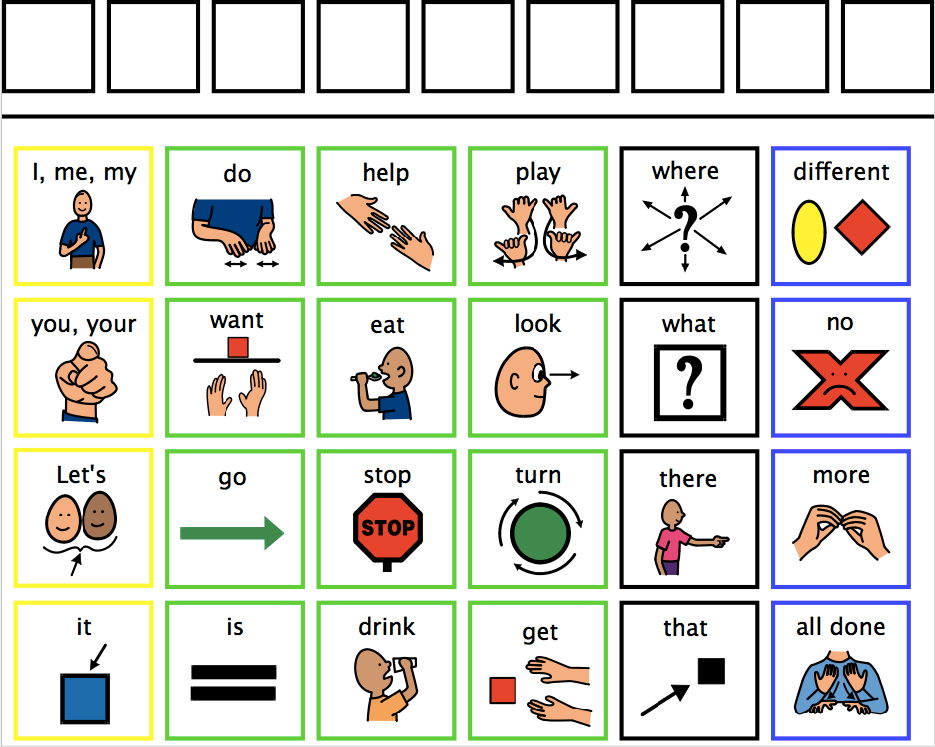

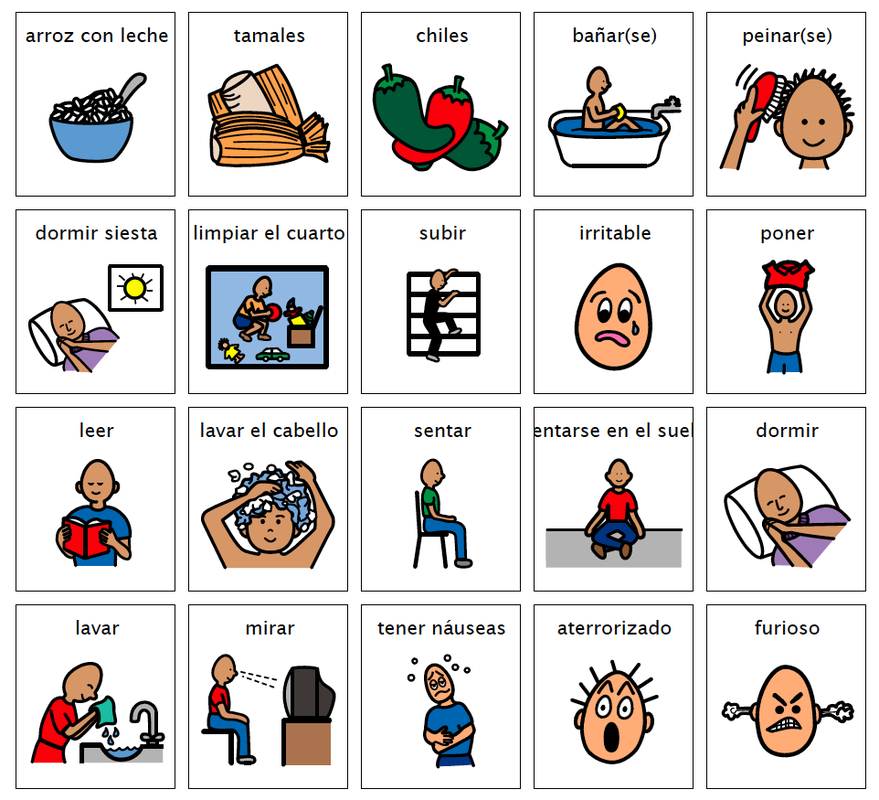

Try using visual supports (such as daily timetables), social stories™, or pre-plan strategies to prepare for change or events that might be stressful, or daily transition times. Egg timers or time timers can help someone to understand abstract concepts like time, plan what they need to do, in what order, and understand the concept of waiting.

Find product suppliers and picture symbols in our Autism Services Directory or find out about apps that you can use to structure time or build social stories™.

Learn more about how you can help with change, sequencing, transition and school break times.

Manage anxiety

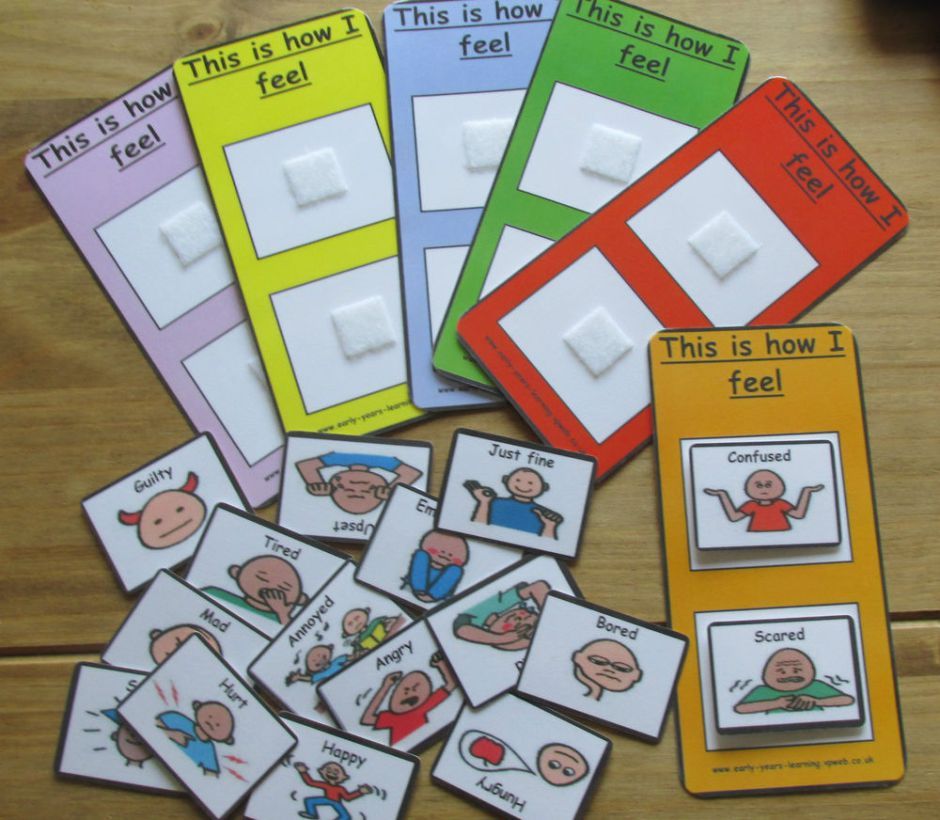

Self-regulation skills are any activities that help a person to manage their own emotions and behaviour.

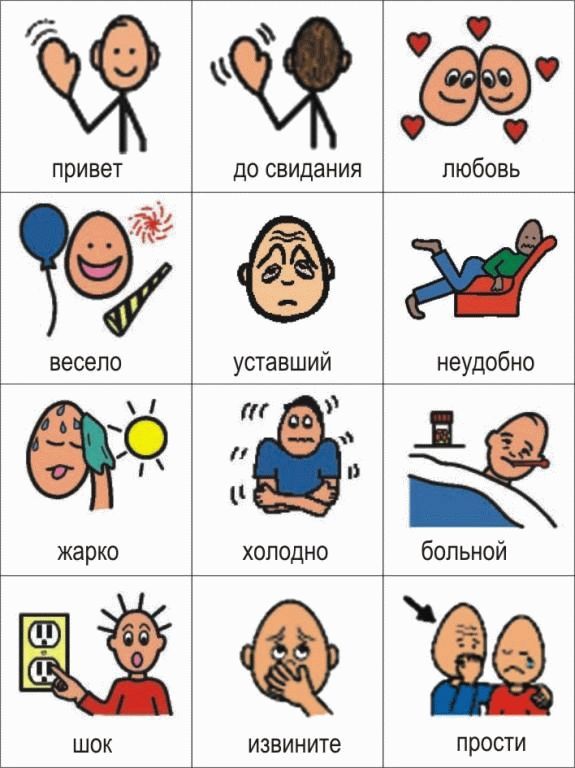

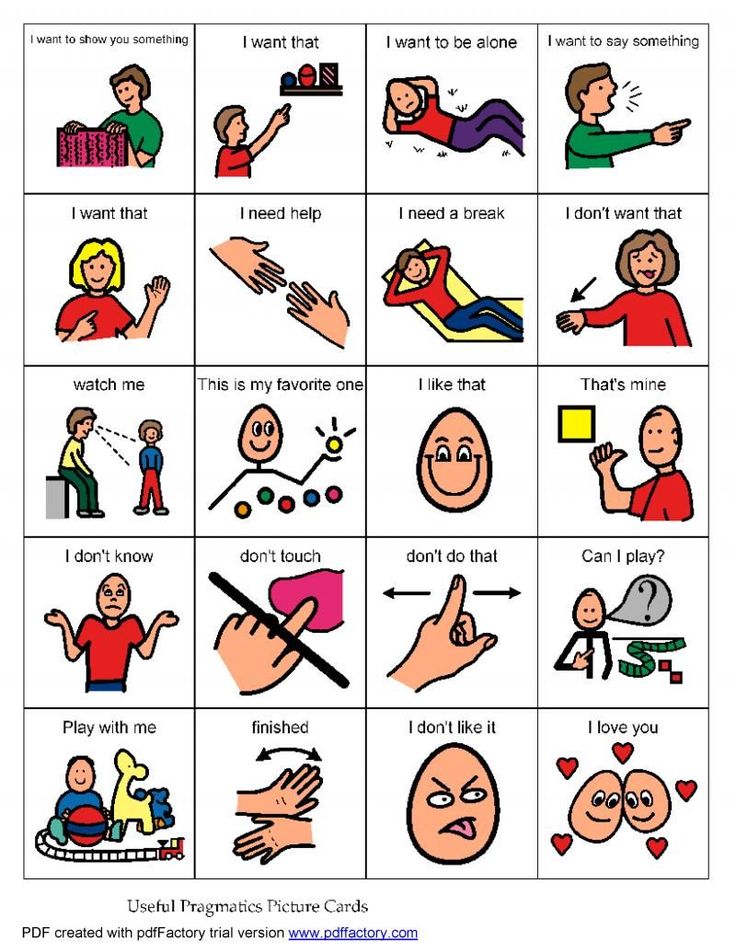

If you can help the person to identify when they are feeling stressed or anxious and help them learn alternative strategies to use, you may, in time, see less repetitive and obsessively habitual behaviour. Strategies to consider might be relaxation techniques such as taking 10 deep breaths or squeezing a stress ball, as well as finding ways to communicate their need for support either verbally or, if that is too difficult, by showing a red card or writing a note.

Many autistic people have difficulty with abstract concepts such as emotions, but there are ways to turn emotions into more 'concrete' concepts, eg stress scales.

You can use a traffic light system, visual thermometer, or a scale of 1-5 to present emotions as colours or numbers. For example, a green traffic light or a number 1 can mean 'I am calm'; a red traffic light or a number 5, 'I am angry'.

Develop other strategies to manage anxiety, such as the Brain in Hand digital self-management support system. Consider contacting a counsellor experienced in working with autistic people.

Intervene early

Repetitive behaviours and obsessions are generally harder to change the longer they continue. Behaviour that is perhaps acceptable in a young child may not be appropriate as they get older, eg obsession with stroking other people's hair. Autistic people should be encouraged to reduce or stop the behaviour before they reach an age where it’s not acceptable.

Set boundaries

If you need to, set clear, consistent limits - for example, ration an object, the time a person should spend talking about a subject, or the places where they can carry out a particular behaviour. Behavioural change is most likely to be successful and the person less likely to be distressed if you start small and go slowly. Increase time restrictions and introduce other limits gradually.

Behavioural change is most likely to be successful and the person less likely to be distressed if you start small and go slowly. Increase time restrictions and introduce other limits gradually.

Decide together a realistic target and put together a plan to reach that target over a period of time. It is important to set small, realistic goals to help build on success and increase confidence.

Think about whether the person would find it easier to engage in the interest for shorter periods throughout the day or for longer periods but less often.

Consider what needs to be changed. Are they unable to stop doing the activity? Work on reducing the time spent on it. Is the issue that they constantly start the activity throughout the day even when they are trying to focus on other things? Work on reducing the frequency. If it is a mixture of both, focus on one aspect to change at first, to increase the chance of success and reduce anxiety.

If it is a mixture of both, focus on one aspect to change at first, to increase the chance of success and reduce anxiety.

Example

- Week 1: decide on the plan and target, creating a visual support explaining the change.

- Week 2: Jane is allowed to talk about her favourite TV programme for 15 mins, every hour.

- Week 3: Jane is allowed to talk about her favourite TV programme for 10 mins, every hour.

- Week 4: Jane is allowed to talk about her favourite TV programme for 10 mins every two hours.

Continue in this way until you meet the goal, which is to find a balance between enjoying the interest and doing other activities.

Provide alternatives

Think of alternative activities the person could do. For example, if they have spoken to family about their interest for the set amount of time that day, consider directing them to record their thoughts on their phone or write them down in an interest book. While the family are no longer engaging in the activity, the thoughts are still expressed, hopefully meeting the person’s need and therefore lowering their anxiety. If they want to express their thoughts about their interest again before their next allotted time, they could write things down and let them know you will talk to them about their notebook thoughts later. You could use visual supports to explain these additional activities.

It might be possible for the person to engage in their interest in new ways, perhaps joining a club or group, or studying or working in a related area.

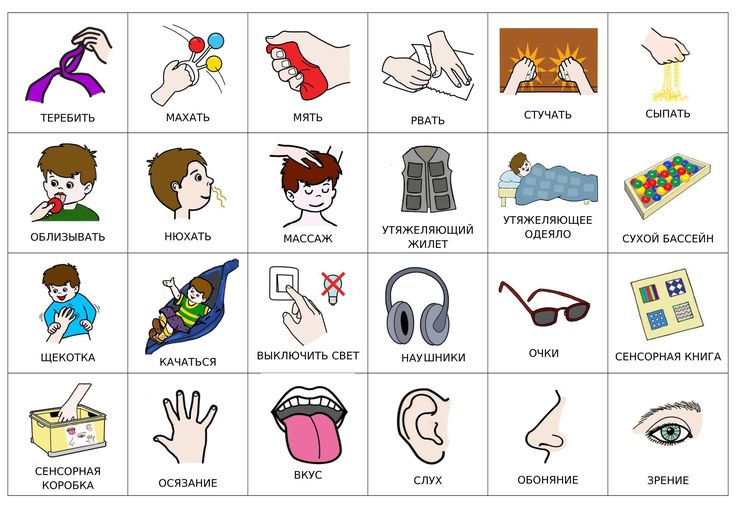

Where the activity relates to sensory needs, provide an alternative activity that has the same function, eg:

- someone who puts inedible objects in their mouth could have a bag with edible alternatives (that provide similar sensory experiences) such as raw pasta or spaghetti, or seeds and nuts

- a person who smears their poo could have a bag with play dough in it to use instead.

More from our charity

- Online Community

- Parent to Parent service

- Use our Autism Services Directory to find counsellors experienced in working with autistic people.

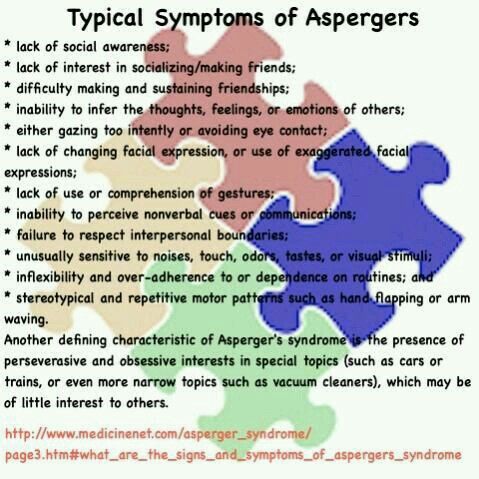

Obsession, Repetition, Routine – AUTISTIC ASPERGERS

Autistic Obsessions, Repetition, Routine

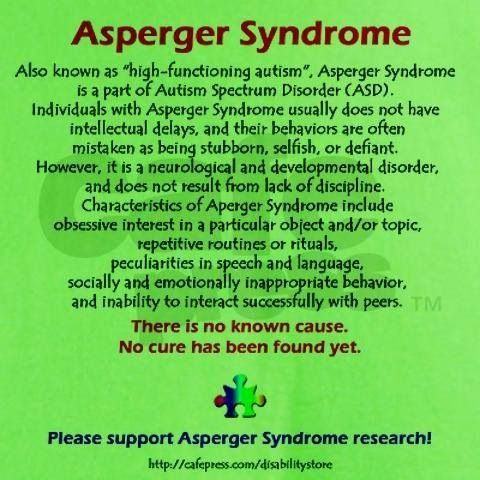

Obsessions, repetitive behavior and routines can be a source of enjoyment for people with autism and a way of coping with everyday life. But they may also limit people’s involvement in other activities and cause distress or anxiety. Repetitive behavior in people with autism is not the same as OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder), which is an anxiety disorder in which people experience repetitive thoughts and behaviors that are upsetting to them.

My mind was constantly whirring with thoughts, worries and concerns. The time spent with my obsession was the only time in which I had a clear mind – it gave me that much sought-after relaxation.

People with autism have many different obsessions but some of the more common ones include computers, trains, historical dates or events, science, or particular TV programs. Many younger children with autism like Thomas the Tank Engine, dinosaurs or particular cartoon characters. Sometimes, people develop obsessions with things like car registration numbers, bus or train timetables, postcodes, traffic lights, numbers, shapes or body parts such as feet or elbows. People with autism may also become attached to objects (or parts of objects), such as toys, figurines or model cars – or more unusual objects like milk bottle tops, stones or shoes. An interest in collecting is also quite common: it might be Star Trek DVDs, travel brochures, insects, leaves or bus tickets.

Many younger children with autism like Thomas the Tank Engine, dinosaurs or particular cartoon characters. Sometimes, people develop obsessions with things like car registration numbers, bus or train timetables, postcodes, traffic lights, numbers, shapes or body parts such as feet or elbows. People with autism may also become attached to objects (or parts of objects), such as toys, figurines or model cars – or more unusual objects like milk bottle tops, stones or shoes. An interest in collecting is also quite common: it might be Star Trek DVDs, travel brochures, insects, leaves or bus tickets.

It is the intensity and duration of a person’s interest in a particular topic, object or collection that marks it out as an obsession. People will often learn a lot about a thing they are obsessed with, be intensely interested in it for a long time, and feel strongly about it.

People with autism may develop obsessions for several reasons, including:

* obsessions may provide structure, order and predictability, and help people cope with the uncertainties of daily life

* people who find social interaction difficult might use their special interests as a way to start conversations and feel more self-assured in social situations

* obsessions may help people to relax and feel happy

* people can get a lot of enjoyment from learning about a particular subject or gathering together items of interest.

Is it an obsession or a hobby?

We all have hobbies and interests and – generally – a strong preference for routine. Here are five questions that can help us distinguish between hobbies and interests, and obsessive behavior.

* Does the person appear distressed when engaging in the behavior or does the person give signs that they are trying to resist the behavior? (that is, someone who flaps their hands may try to sit on their hands to prevent the behavior.)

* Can the person stop the behavior independently?

* Is the behavior impacting on the person’s learning?

* Is the behavior limiting the person’s social opportunities?

* Is the behavior causing significant disruption to other people, eg parents, carers and family? (Clements and Zarkowska, 2000)

If your answer to any of the questions above is ‘yes’, it may be appropriate to look at ways of helping to reduce obsessive or repetitive behavior. Think about whether, by setting limits around a particular behavior, you are really helping the person with autism. Is the behavior actually a real issue for them, for you, or for other people in their life? Focus on developing skills that the person with autism can use instead of repetitive or obsessive behavior. Try to understand the function of the behavior, then make small, gradual changes and be consistent.

Is the behavior actually a real issue for them, for you, or for other people in their life? Focus on developing skills that the person with autism can use instead of repetitive or obsessive behavior. Try to understand the function of the behavior, then make small, gradual changes and be consistent.

“I quickly become overwhelmed [in social situations]. Is it surprising that I then feel like blocking the world out and literally putting my thoughts back in order? That I start to rock to tell myself which feelings are mine? That I start speaking to myself or groaning to block out other sounds and so that I know which thoughts are mine? I think anyone experiencing life this way would do the same.” Adult with autism

Repetitive behavior may include arm- or hand-flapping, finger-flicking, rocking, jumping, spinning or twirling, head-banging and complex body movements. You may also see the repetitive use of an object, such as flicking a rubber band or twirling a piece of string, or repetitive activities involving the senses (such as repeatedly feeling a particular texture). Many people with autism have sensory sensitivity and may be over- or under-sensitive to sights, sounds, smells, taste and touch. This sensitivity can also affect people’s balance (‘vestibular’ system) and body awareness (‘proprioception’ – knowing where our bodies are and how they are moving). Repetitive behavior can be a way to deal with sensory sensitivity. Although repetitive behavior varies from person to person, the reasons behind it may be the same:

You may also see the repetitive use of an object, such as flicking a rubber band or twirling a piece of string, or repetitive activities involving the senses (such as repeatedly feeling a particular texture). Many people with autism have sensory sensitivity and may be over- or under-sensitive to sights, sounds, smells, taste and touch. This sensitivity can also affect people’s balance (‘vestibular’ system) and body awareness (‘proprioception’ – knowing where our bodies are and how they are moving). Repetitive behavior can be a way to deal with sensory sensitivity. Although repetitive behavior varies from person to person, the reasons behind it may be the same:

* an attempt to gain sensory input, like rocking may be a way to stimulate the balance (vestibular) system; hand-flapping may provide visual stimulation

* an attempt to reduce sensory input, like focusing on one particular sound may reduce the impact of a loud, distressing environment; this may particularly be seen in social situations

* a way to deal with stress and anxiety and to block out uncertainty. Some adolescents or adults may revert to old repetitive behaviors such as hand-flapping or rocking if anxious or stressed

Some adolescents or adults may revert to old repetitive behaviors such as hand-flapping or rocking if anxious or stressed

* a source of enjoyment and occupation.

“Reality to an autistic person is a confusing, interacting mass of events, people, places, sounds and sights… Set routines, times, particular routes and rituals all help to get order into an unbearably chaotic life. Trying to keep everything the same reduces some of the terrible fear.” Jolliffe (1992) in Howlin (2004), p.137.

Many people with autism have a strong preference for routines and sameness. Routines often serve an important function – they introduce order, structure and predictability and help to manage anxiety. Because of this, it can be very distressing if a person’s routine is disrupted. Sometimes minor changes such as moving between two activities can be distressing; for others big events like holidays, birthdays or Christmas, which create change and upheaval, can cause anxiety. Unexpected changes are often most difficult to deal with. Some people with autism have daily timetables so that they know what is going to happen, when. However, the need for routine and sameness can extend beyond this. You might see:

Unexpected changes are often most difficult to deal with. Some people with autism have daily timetables so that they know what is going to happen, when. However, the need for routine and sameness can extend beyond this. You might see:

* changes to the physical environment (such as the layout of furniture in a room), or the presence of new people or absence of familiar ones, being difficult to manage

* rigid preferences about things like food (only eating food of a certain color), clothing (only wearing clothes made from specific fabrics), or everyday objects (only using particular types of soap or brands of toilet paper)

* a need for routine around daily activities such as meals or bedtime. Routines can become almost ritualistic in nature, having to be followed precisely with attention paid to the tiniest details

* verbal rituals, with a person repeatedly asking the same questions and needing a specific answer

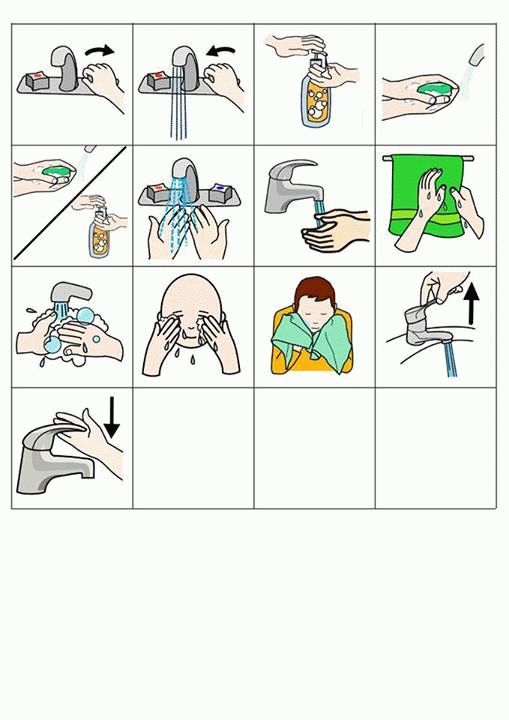

* compulsive behavior, for example a person might be constantly washing their hands or checking locks. This does not necessarily mean they have obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) but if you are concerned about this, speak to your GP in the first instance.

This does not necessarily mean they have obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) but if you are concerned about this, speak to your GP in the first instance.

People’s dependence on routines can increase during times of change, stress or illness and may even become more dominant or elaborate at these times (Attwood, 1998). Dependence on routines may increase or re-emerge during adolescence. Routines can have a profound effect on the lives of people with autism, their family and carers, but it is possible to make a person less reliant on them.

Setting limits

Here is an example of how to set limits.

* Identify the repetitive behavior, obsession or routine of concern. Jane likes to talk about train engines. Jane currently starts talking about train engines after about ten seconds of conversation for up to 15 minutes.

* Think about reasonable limits you can put in place that your child can manage. Behavioral change is most likely to be successful and your child less likely to be distressed if you start small and go slowly. Jane is allowed to talk about train engines after 20 seconds of conversation for five minutes only. She is also getting social skills training.

Jane is allowed to talk about train engines after 20 seconds of conversation for five minutes only. She is also getting social skills training.

* Gradually increase time restrictions and introduce other limits. Jane is first allowed to talk about train engines three times a day. Then, Jane is only allowed to talk about train engines with her family three times a day. The eventual goal is for Jane to speak about train engines to her family only for one minute, twice a day.

* If you place limits around obsessions or repetitive behavior, you might need to think about things your child can do instead: perhaps joining a club or group; taking up a sport or leisure activity; or entering further education, job preparation training or employment if possible.

People with autism might have obsessions, repetitive behaviors and routines for a variety of reasons. Some things to think about respond the behavior in a helpful way.

* Understand and intervene

* Increase structure

* Help with skills development

* Set limits

* Make use of obsessions

Understand and interveneUnderstand the function of the behavior

Obsessions, repetitive behavior and routines are frequently important and meaningful to people with autism, helping them to manage anxiety and have some measure of control over a confusing and chaotic world. For others, the behavior may help with sensory issues. Take a careful look at what you think might be causing the behavior and what purpose it might serve. For example, does the person with autism always seem to find a particular environment, like a classroom, hard to cope with? Is it too bright? Could you turn off strip lighting and rely on natural daylight instead?

For others, the behavior may help with sensory issues. Take a careful look at what you think might be causing the behavior and what purpose it might serve. For example, does the person with autism always seem to find a particular environment, like a classroom, hard to cope with? Is it too bright? Could you turn off strip lighting and rely on natural daylight instead?

Intervene early

Repetitive behaviors, obsessions and routines are generally harder to change the longer they continue. A behavior that is perhaps acceptable in a young child may not be appropriate as they get older and may, by this time, be very difficult to change. For example, a child who is obsessed with shoes and tries to touch people’s feet might not present too much of a problem, but an adolescent or adult doing the same thing – especially to strangers – will obviously be problematic. It will help if you can set limits around repetitive behaviors from an early age (see the section on setting limits) and look out for any new behavior that emerges as your child gets older.

Increase structure

Making the person with autism’s environment and surroundings (including social situations where possible) more structured can help them to feel more in control and may reduce anxiety. If anxiety is reduced, the need to engage in repetitive behavior and adhere strictly to routines may also, in time, be reduced. Here are some suggestions for creating a more structured environment.

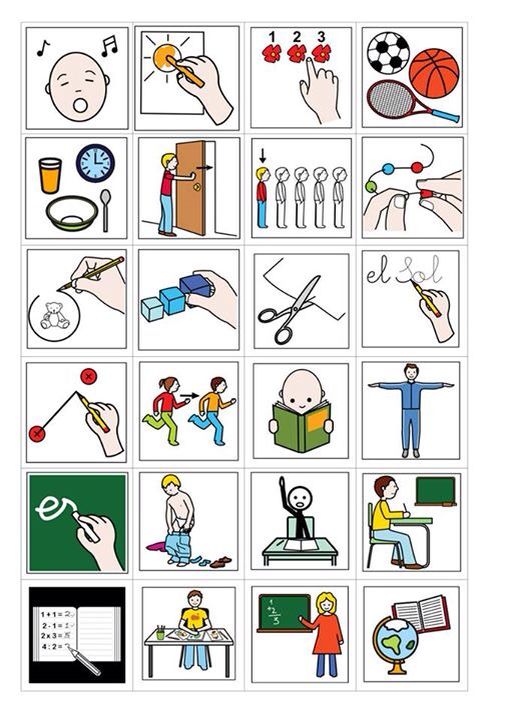

Visual supports

Visual supports such as photos, symbols, written lists or physical objects can really help people with autism.

* A visual timetable could help your child to see what is going to happen next (for example, across the course of a day). This makes things more predictable and helps them to feel prepared. It may lessen their reliance on strict routines of their own making.

* Visual supports like egg timers or ‘time timers’ (available online) can help some people with autism to understand abstract concepts like time, plan what they need to do, when in order to complete a task, and understand the concept of waiting.

* Visual supports can also be useful if your child asks the same question repeatedly. One parent wrote down the answer to a question, put it on the fridge and, whenever her son asked the question, told him to go to the fridge and find the answer. For children who can’t read, you could use pictures instead of words.

Pre-planning

You may be able to help someone with autism to cope with change, or activities and events that could be stressful, by planning for them in advance. Change is unavoidable but it can be really difficult for many people with autism. You may not always be able to prepare for change a long time in advance, but try to give the person as much warning as possible.

* Gradually introducing the idea of a new person, place, object or circumstance can help them cope with the change. Try to talk about the event or activity when everyone is fairly relaxed and happy.

* Presenting information visually can be a good idea, as the person with autism can refer to it as often as they need to.

* You could try using calendars so that the person knows how many days it is before an event – such as Christmas – happens. This can help them feel prepared. They might also like to see photos of places or objects in advance so they know what to expect, for example, a picture of their Christmas present (not all children with autism like surprises), or a photo of the building they are going to for an appointment.

* Using social stories could also be helpful. These are short stories, often with pictures, that describe different situations and activities so that people with autism know what to expect.

Pre-planning can also involve structuring the environment. For example, a pupil with autism might go to use a computer in the library at lunchtime if they find being in the playground too stressful. Or if a child has sensory sensitivity, minimizing the impact of things like noises (like school bells) or smells (eg perfumes or soaps) can help them to cope better. It is possible that more structured environments may reduce boredom, which is sometimes a reason for repetitive behavior. You might prepare a range of enjoyable or calming activities to re-direct the person with autism to if they seem bored or stressed.

You might prepare a range of enjoyable or calming activities to re-direct the person with autism to if they seem bored or stressed.

Skill development

Self-regulation skills

Self-regulation skills are any activities that help a person with autism to manage their own behavior and emotions. If you can help the person to identify when they are feeling stressed or anxious and use an alternative response (such as relaxation techniques or asking for help), you may, in time, see less repetitive and obsessively habitual behavior.

Research has also shown that increasing a person’s insight into an obsession or repetitive behavior can significantly reduce it. This includes people with quite severe learning disabilities (Koegel et al, 1995, in Howlin, 2004).

Social skills training

Teaching social skills such as how to start and end a conversation, appropriate things to talk about, and how to read other people’s ‘cues’ (eg, we sometimes raise our eyebrows slightly if we want to speak or say something like ‘Yes, but…’) may mean someone with autism feels more confident and doesn’t need to rely on talking about particular subjects, such as a special interest.

Coping with change

See the section above on pre-planning for information on this. However, if unexpected changes do happen and the person with autism is finding it hard to cope, try re-directing them to a calming activity, or encourage them to use simple relaxation techniques such as breathing exercises. You could use praise or other rewards for coping with change. In the long term, this may help make the person more tolerant of change.

Explore alternative activities

One way to interrupt repetitive behavior is for the person with autism to do another enjoyable activity that has the same function. Here are some examples:

* a person who rocks to get sensory input could go on a swing

* a person who flicks their fingers for visual stimulation could play with a kaleidoscope or a bubble gun

* a person who puts inedible objects in their mouth could have a bag with edible alternatives (that provide similar sensory experiences) such as raw pasta or spaghetti, or seeds and nuts

* a person who smears their poo could have a bag with play dough in it to use instead.

Set limits

Setting limits around repetitive behavior, routines and obsessions is an important and often essential way to minimize their impact on the person with autism’s life. You could set limits in a number of ways depending which behavior concerns you:

* ration objects (can only carry five pebbles in pocket)

* ration times (can watch Thomas the Tank Engine DVD for 20 minutes twice a day)

* ration places (spinning only allowed at home).

Everyone involved with the person should take the same consistent approach to setting limits. Have clear rules about where, when, with whom and for how long a behavior is allowed. You could present this information visually, with a focus on when the person can engage in the behavior. This may help if they feel anxious about restricted access to an obsession or activity. Read an example of setting limits.

Make use of obsessions

Obsessions can be used to increase a person’s skills and areas of interest, promote self-esteem, and encourage socializing. You may find you can look at a particular obsession and think of ways to develop it into something more functional. Here are some examples.

You may find you can look at a particular obsession and think of ways to develop it into something more functional. Here are some examples.

* An obsession with computers could be developed into someone studying or working in IT.

* A person with a special interest in historical dates could join a history group and meet people with similar interests.

* A person with knowledge of sport or music would be a valuable member of a pub quiz team.

* An obsession with rubbish could be used to develop an interest in recycling, and a child given the job of sorting items for recycling.

* An interest in particular sounds could be channeled into learning a musical instrument.

* A strong preference for ordering or lining up objects could be developed into housework skills.

You can also use obsessions to motivate and reward the person with autism. Follow a less desired activity (such as homework) by a chance to do something the person really loves (such as extra time on the computer). If you and other people the person knows can show an interest in their obsession this may be welcomed and help to boost their self-esteem. “Showing an interest in a child’s obsession can help a parent to enjoy a level of communication that had perhaps never seemed achievable before.” Young person with Asperger syndrome

If you and other people the person knows can show an interest in their obsession this may be welcomed and help to boost their self-esteem. “Showing an interest in a child’s obsession can help a parent to enjoy a level of communication that had perhaps never seemed achievable before.” Young person with Asperger syndrome

To sum up…

* Ask yourself if the obsession, routine or repetitive behavior restrict your child’s opportunities, cause distress or discomfort or impact on learning. If not, is it really necessary to intervene?

* Think about the function of the repetitive behavior, routine or obsession. What does your child get out of it?

* Intervene early: set limits around repetitive behavior and obsessions from a young age (and new ones if they emerge).

* Make the world a more structured and predictable place. Try using visual supports (such as daily timetables), social stories, or pre-planning strategies to prepare for change or events that might be stressful. This may limit reliance on routines or repetitive behavior.

This may limit reliance on routines or repetitive behavior.

* Help your child to develop skills where possible, for example social skills training, learning relaxation techniques or learning to identify emotions. These can all be ways of managing stress or uncertainty (which may lead to repetitive behavior).

* Look at things that your child can do instead of carrying out a repetitive behavior or focusing on an obsession.

* If you need to, set clear, consistent limits – for example, ration an object, the time your child is allowed to spend talking about it, or the places where they can carry out a particular behavior.

* Remember that obsessions and repetitive behavior can be therapeutic and help your child to relax, or calm down if agitated. Don’t take away all access to an obsession or try to change behavior overnight – this could be distressing. Make gradual changes.

* Make use of obsessions, they could be a way to socialize, learn a new skill or improve self-esteem. People may eventually be able to study or work in related areas.

People may eventually be able to study or work in related areas.

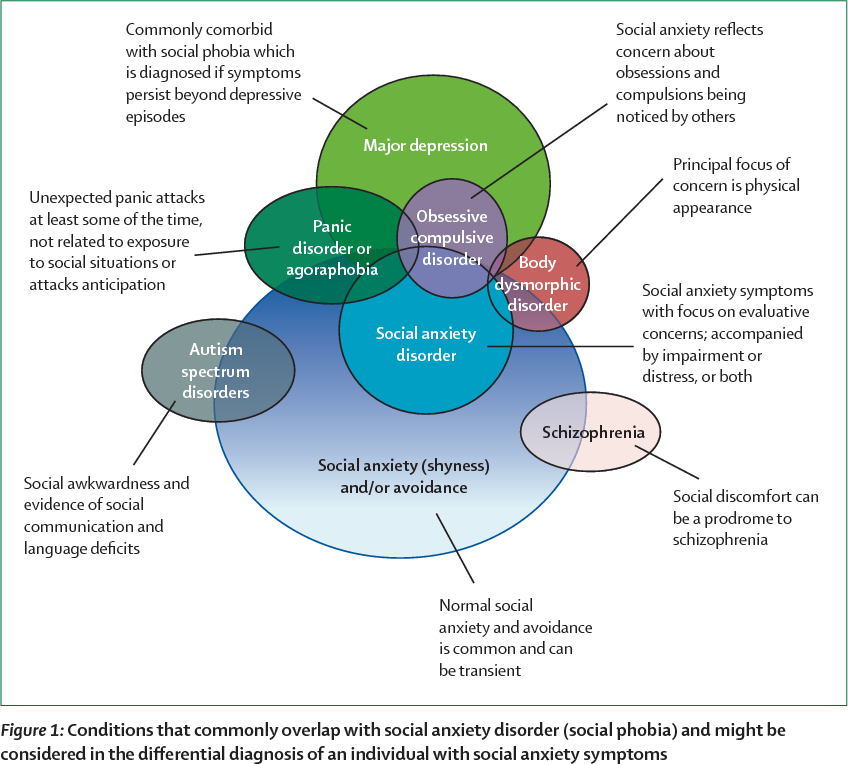

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism

03/05/19

Autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often coexist, scientists are trying to study both disorders in order to better differentiate them and determine more effective treatment

Author Daisy Yuhas

Source: Spectrum News

Steve Slavin was 48 years old when a visit to a psychologist forced him to dramatically change his ideas about his own life. He had a very difficult year. Slavin began to suffer from anxiety, which manifested itself in negative thoughts and repetitive actions, and this was not the first time he suffered from them.

As a child, he could not enter a room unless he had swallowed an even number of times beforehand, and he had to swallow and count to four, six, or eight with one foot up before stepping on a stone in the pavement. As an adult, he often experienced a lot of stress around other people, and he washed his hands again and again because he was terrified of catching something from other people. He also often suffered from depression, due to which he began to avoid acquaintances and friends.

As an adult, he often experienced a lot of stress around other people, and he washed his hands again and again because he was terrified of catching something from other people. He also often suffered from depression, due to which he began to avoid acquaintances and friends.

This time his depression and anxiety got worse and his doctor referred him to a psychologist. “I spent weeks, if not months, trying to get an appointment with him,” he recalls. However, within the first 10 minutes of the meeting, the psychologist suddenly stopped asking him about his childhood and current mental health issues, and instead asked him what he knew about autism.

Coincidentally, a relative had spoken to Slavin about autism just two days earlier, suggesting that this might explain his dislike of social situations. Slavin knew almost nothing about autism, but suggested that it was possible. By the end of the consultation, the psychologist was practically certain that “I either have high-functioning autism or some kind of brain damage,” Slavin recalls, chuckling. Only a few years later, the doctor gave him an official diagnosis - obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). He was also confirmed to have autism.

Only a few years later, the doctor gave him an official diagnosis - obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). He was also confirmed to have autism.

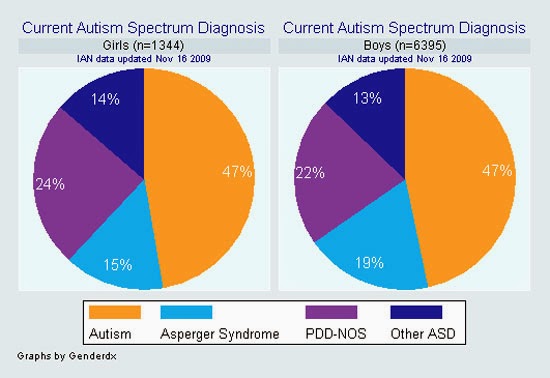

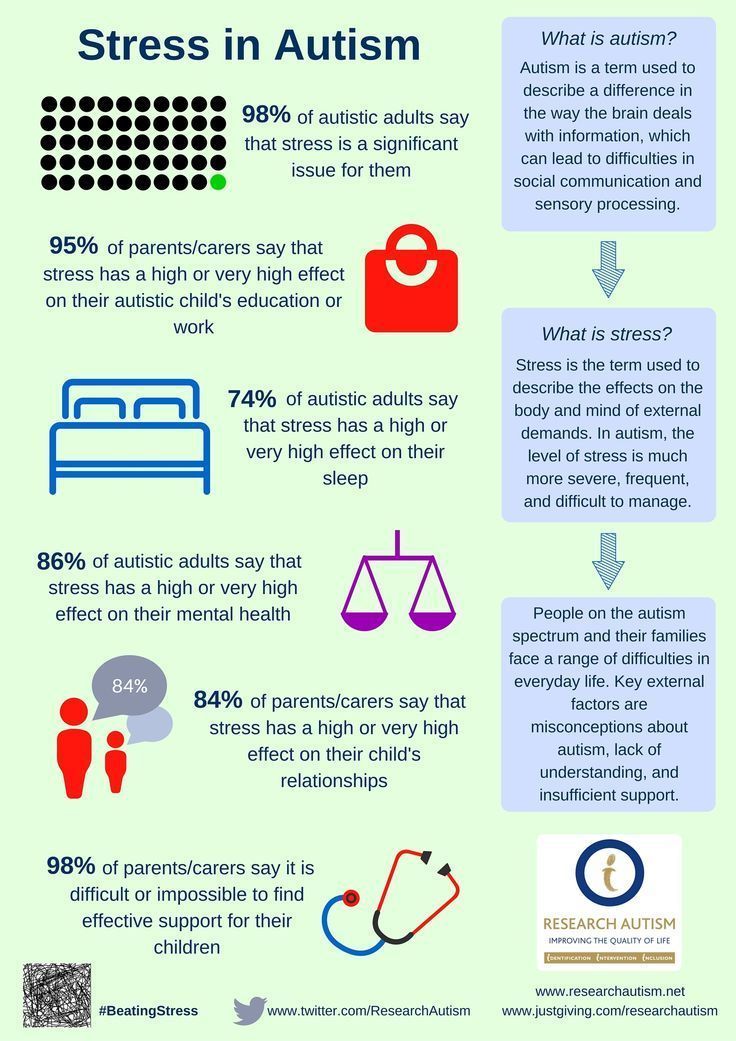

At first glance, autism and obsessive-compulsive disorder seem to have nothing in common. However, doctors and researchers talk about the intersection of these two disorders. Research data indicate that up to 84% of autistic people suffer from some type of anxiety disorder, and up to 17% of people with autism have OCD. And according to one 2017 study, even more people with OCD have undiagnosed autism.

Part of this overlap may be due to misdiagnosis: OCD-induced rituals may resemble repetitive behaviors in autism, and vice versa. However, there is growing evidence that many people, like Slavin, have both disorders. A 2015 study that analyzed the health records of 3.4 million Danish people over 18 years found that as adults, people with autism are twice as likely to be diagnosed with OCD than people without autism. Similarly, the same study found that people with OCD were four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism as adults than people without OCD.

Over the past ten years, researchers have begun to study the combination, interaction, and differences between these two disorders. Understanding these differences is important not only for making a correct diagnosis, but also for choosing an effective treatment. It appears that the experience of people with OCD and autism is unique, different from that of people with one of these disorders. And for these people, standard OCD treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), may not be effective.

Missed diagnoses

Anyone can develop obsessive thoughts (obsessions) or obsessive actions (compulsions). Many people start worrying about not turning off the stove at home, or checking again that they took their keys with them. "It's part of a normal life experience," says Ailsa Russell, a clinical psychologist at the University of Bath in the UK.

Most people can get over these unpleasant obsessions and go on with their normal lives. However, with obsessive-compulsive disorder, such anxiety becomes stronger and begins to interfere with normal daily functioning.

Some people with OCD, like Slavin, count steps or breaths or perform other meaningless actions because they feel that without these actions, something terrible is bound to happen. Other people call themselves "inspectors" - they check again and again that they have done a task correctly, and this prevents them from doing other things. Other people with OCD are constantly bathing or scrubbing because they are afraid of dirt or contamination.

"Typically, people with OCD are aware that their fears and behavior are irrational," says Russell, despite this OCD sufferer is trapped in intense anxiety and compulsive rituals.

The intersection between OCD and autism is still poorly understood. According to a 2015 analysis, people with both disorders are characterized by non-standard sensory responses. For some autistic people, sensory overload is the main source of stress and anxiety. For example, Slavin is terrified of police sirens and doorbells, he says that for his nervous system they are like bomb explosions.

Some researchers say that the social problems of people with autism can increase their anxiety, which in turn can lead to OCD. Failure to interpret social cues can lead to social isolation or bullying by others, which increases anxiety. “Separating anxiety from autism is extremely difficult,” says Roma Vasa, director of mental health services at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, USA.

These commonalities can make it difficult to distinguish between symptoms of autism and OCD. Even for an experienced clinician, OCD compulsions can resemble the “sameness seeking” or repetitive behaviors of autistic people, which may include tapping, lining up objects, or striving to always walk in the same path. Separating the two states can be a daunting task.

As the 2015 analysis showed, the key difference is that obsessive thoughts (obsessions) lead to obsessive actions (compulsions), but not to autistic symptoms. Another feature is that people with OCD cannot, in principle, replace their rituals with other actions. In Vasa's words: "They need to do everything in a certain way, otherwise they experience anxiety and discomfort."

In Vasa's words: "They need to do everything in a certain way, otherwise they experience anxiety and discomfort."

At the same time, autistic people tend to have a repertoire of different repetitive behaviors that serve a similar function and from which to choose. “They just go for any behavior that helps them calm down, it doesn’t really matter to them any particular action,” says Jeremy Winstra-Vanderviel, professor of psychiatry at Columbia University, USA.

Thus, doctors need to determine why a person performs a particular action. But this task becomes difficult if it is difficult for the patient to describe his experience in words. Autistic people may have speech, communication, or intellectual impairments and often have significant difficulty identifying and understanding their inner experience. This can lead to misdiagnosis, as happened in the case of Slavin.

As a child, Slavin often visited a psychologist's office in the suburbs of London. However, the experts who examined him missed both OCD and autism. Slavin did not speak until the age of 6. According to him, his first childhood memories are classes with a speech therapist and a child psychologist. Even after he started talking, he avoided other people and didn't like making eye contact. He suffered from severe anxiety and abdominal pain.

Slavin did not speak until the age of 6. According to him, his first childhood memories are classes with a speech therapist and a child psychologist. Even after he started talking, he avoided other people and didn't like making eye contact. He suffered from severe anxiety and abdominal pain.

At about 11 years of age, he was diagnosed with "childhood schizophrenia" and was prescribed Valium and lithium. Doctors warned his parents that he might need a lifelong stay in a medical facility. Instead, he was able to attend a prestigious high school, get a degree and become, in his words, a "slightly more functional" person, and thanks to his passion for music, he was able to launch a career as a professional composer.

Being diagnosed with autism many years later brought him great relief, but it was also associated with new problems. During conversations with specialists, for example, they began to attribute any of his complexities to autism, including problems with the perception of auditory information. “Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it.

“Once you get this diagnosis, the doctors start saying, ‘Well, it’s because of autism,’ they don’t pay attention to the nuances,” he says. Slavin found that no one can say for sure whether a particular behavior is the result of OCD or autism, or what exactly can be done about it.

General Biology

Slavin's questions may be answered soon as more researchers look at the combination of autism and OCD. Until 10 years ago, research on this topic was practically non-existent, says Suma Jacob, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, USA. When she said she was interested in studying the two disorders, "the main experts in the field said to pick one disorder," she says. This situation is starting to change, in part because researchers have begun to realize how common it is to combine autism and OCD.

Jacob and colleagues have been tracking repetitive behaviors (which may be associated with autism or OCD) in thousands of children as young as 3 years old. “From a brain perspective, all these disorders are connected,” she says.

“From a brain perspective, all these disorders are connected,” she says.

In fact, scientists have found that the same brain regions and neural pathways play an important role in both autism and OCD. Brain scans point to a special role for the striatum, an area of the brain that is associated with motor functions and rewards. Some research suggests that in people with autism and people with OCD, one structure within the striatum, the caudate nucleus, is larger than normal.

Animal models also suggest a role for the striatum. Winstra-Vanderwil studies autism and OCD with repetitive behavior rodents. He and other scientists found that in both disorders, the animals show abnormalities in the neural circuitry that runs through the striatum and plays a key role in how we start and stop behavior, as well as influencing habit formation.

Another area of research is related to interneurons, which often suppress impulses between cells. If the interneurons in the striatum of mice are disrupted, this leads to twitching, anxiety, and repetitive behavior that resembles OCD and Tourette's syndrome.

In male mice, the impact on the functioning of interneurons also leads to a sharp decrease in sociability, which, to some extent, may resemble autism. "Unexpectedly, mice also developed social deficits identical to those we see in animal models of autism," says Christopher Pittenger, director of the OCD Research Clinic at Yale University, who led the work. For this reason, he says, interneurons could be a target for both OCD and autism treatments.

This connection at the level of neural pathways may reflect common genetic causes. A 2015 Danish study found that people with autism were more likely to have relatives with OCD than people in a control group. However, genetic comparisons of the two disorders have shown conflicting results at this stage, which may be due to the fact that very little is known about genetic factors in OCD. “As embarrassing as it is to admit, we know a lot more about the genetics of autism than we do about the genetics of OCD,” says Pittenger. A similar gap may explain why a 2018 meta-analysis of genome studies of more than 200,000 people with 25 disorders, including autism and OCD, found no common gene variants for OCD and autism.

Unpublished work by another research group suggests that rare “de novo mutations,” that is, spontaneous mutations that neither parent has, significantly increase the risk of autism and OCD. Some of the genes that researchers have linked to both diagnoses are related to the immune system. This suggests that interactions between environmental factors and the immune system may play a role. Another gene from the general list, CHD8, regulates gene expression.

Treatment adaptation

Until scientists can combine all the data from the preliminary studies, no new drugs can be expected. But there are other methods that can help people with both disorders.

On a chilly December evening, people from all over the UK join the OCD & Autism Support Group, a monthly online conference organized by OCD Action, a British charity that helps people with OCD. The number of group members varies greatly during each meeting, but this evening, a few days before Christmas, only four people called.

During the meeting, a woman named Michelle (only given names in the group) explains that she cannot leave the house unless she makes sure all the lights and appliances are turned off. Thomas spends several hours a day showering. Both of them talk about social difficulties and how they make them anxious. They often worry about what other people think of them, and whether others find their behavior related to OCD or autism strange.

Like most support groups, calling together helps participants feel they are not alone. They also share new information and tips, such as how to use a timer to reduce the time spent washing your hands. Three of the participants mention cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which can help people better understand and manage their obsessive thoughts and actions. As with other forms of psychotherapy that rely on dialogue, it may not be effective for people with autism. For example, such psychotherapy did not help Slavin.

He suspects that he was unable to follow the therapist's methods because of his difficulty with listening to speech and lack of mental flexibility, which he attributes to autism. “Many people on the autism spectrum find it difficult to imagine the situation and how it could lead to a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn't always work,” he says. Instead, Slavin controls OCD with varying degrees of success with antidepressants.

“Many people on the autism spectrum find it difficult to imagine the situation and how it could lead to a different outcome, so traditional CBT doesn't always work,” he says. Instead, Slavin controls OCD with varying degrees of success with antidepressants.

Some researchers are trying to adapt CBT for people with autism, such as "making sure everyone can see and appreciate their own emotional state," says Russell. Together with her colleagues at King's College London, Russell found in a preliminary study that modified methods may help some adults with autism and OCD manage their anxiety. In January of this year, she and her colleagues, building on the success of the subsequent larger study, developed a clinical guideline.

People with autism and OCD can also benefit from a more personalized approach to cognitive behavioral therapy. For example, possible schemes might include parent participation in counseling, language facilitation according to the person's language ability, use of visual support and rewards. One clinical trial compared this adapted therapy with standard CBT in more than 160 children with autism and OCD. As yet unpublished results suggest that standard CBT may be beneficial, but an individualized approach works best.

One clinical trial compared this adapted therapy with standard CBT in more than 160 children with autism and OCD. As yet unpublished results suggest that standard CBT may be beneficial, but an individualized approach works best.

It seems to Slavin that a more individual approach to treatment can be successful, but he himself has not tried such approaches. Working with organizations that help people with OCD and people with autism, he began to appreciate the diversity of people with both disorders. “It feels like every single person needs their own diagnosis, their own category, because everyone is so different,” he says.

Ten years after being diagnosed with autism, Slavin wants to share his experience, also in order to combat the lack of resources he has faced. In 2010, he opened a website and started a YouTube channel where he talks about what he has learned about living with autism.

“I just think of autism as a certain set of circumstances that you can use to your advantage and say, 'OK, I'm going to forgive myself if I don't quite understand how other people act,'” says Slavin. “You can even find joy in your oddities and differences from others ... But OCD, there is nothing good about it at all.”

“You can even find joy in your oddities and differences from others ... But OCD, there is nothing good about it at all.”

In October he published a book on his progress. So far, the title of the book sounds like "The search for the norm."

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

Research, Psychiatry, Comorbidities

Obsessions, repetitive behaviors and routines

Obsessions, repetitive behaviors and routines can be a source of joy and enjoyment for people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and a way to cope with the demands of everyday life. However, they can also limit people's participation in other activities and cause a lot of stress.

This article, which is primarily intended for parents of children with ASD, addresses the following questions:

- definition of obsessions, repetitive behaviors and routines

- the functions they perform

- how you can respond to them.

The article says "child", but it can refer to a person of any age, including your adult children, as long as it does not specifically mention small children.

Obsessive interests

"My mind is constantly overflowing with thoughts, worries and fears. The time devoted to my obsessive interest is the only time in my life when I can clear my mind, it brings me much desired relaxation" - a young man with Asperger's syndrome.

People with ASD may be obsessed with a wide variety of topics, including common ones such as computers, trains, historical dates or events, science, or a particular television program. Many young children with ASD love Thomas the Tank Engine, dinosaurs, or specific cartoon characters. Sometimes people with ASD develop an obsessive interest in objects such as car numbers, bus or train timetables, zip codes, traffic lights, numbers, or specific body parts such as feet or elbows.

People with ASD can also become very attached to specific objects (or parts of objects), such as toys, action figures, or toy cars. It can be more unusual items - milk bottle caps, stones or shoes. Collectibles are no less common, such as Star Trek DVDs, travel brochures, insects, leaves, or bus tickets.

It can be more unusual items - milk bottle caps, stones or shoes. Collectibles are no less common, such as Star Trek DVDs, travel brochures, insects, leaves, or bus tickets.

Interest in a particular topic, subject, or collection can be considered obsessive when of unusual intensity and duration. People with ASD very often have comprehensive information about the subject of their obsession, they can be interested in this subject for a very long time and experience very strong emotions about it.

There are several reasons why people with ASD may develop obsessions, including:

- obsessions provide structure, order, and predictability to help deal with the uncertainty of everyday life

- People who find social interaction too difficult may use special interests as an excuse to talk and increase self-confidence in social situations.

- obsessions help people relax and feel happy

- people can have a lot of fun learning new information about a particular subject or expanding their collection.

Repetitive behavior

"I quickly panic [in social situations]. And is it any wonder that in this case I want to isolate myself from the outside world in order to literally put my thoughts in order? That I start to sway to say myself to myself that my body still belongs to me? That I start talking to myself or moaning to block out external sounds and find out which thoughts belong to me? It seems to me that any person who perceives life in this way will do this, "adult person with autism.

Repetitive behaviors may include arm or hand swinging, finger movements, torso rocking, jumping, spinning and circling, head banging on floors or walls, and highly complex body movements.

Repetitive handling of an object, such as clicking a rubber band or fiddling with a piece of string, and repetitive motions combined with sensory experiences (eg, repetitive touching of a particular fabric or surface) are also common.

Many people with ASD have sensory sensitivity that is above or below normal in terms of sight, sound, smell, taste and touch. This sensitivity can also relate to balance (vestibular system) and perception of one's own body (proprioception - knowledge of the position of parts of one's body and their movements). Repetitive behavior can be a way to deal with sensory sensitivity. For more information on this subject, see the article "The Sensory World of Autism".

This sensitivity can also relate to balance (vestibular system) and perception of one's own body (proprioception - knowledge of the position of parts of one's body and their movements). Repetitive behavior can be a way to deal with sensory sensitivity. For more information on this subject, see the article "The Sensory World of Autism".

Although the repetitive behavior varies from person to person, the reasons for this behavior can be the same:

- trying to get sensory input, eg rocking can be a way to stimulate the vestibular system; arm waving can provide visual stimulation

- an attempt to reduce sensory input, such as focusing on a particular sound to help disconnect from a noisy, highly stressful environment; This is most often seen in social situations.

- way to cope with stress and anxiety, disconnect from the uncertain reality. Some adolescents and adults may suddenly develop old repetitive behaviors, such as arm waving or rocking, if they are experiencing severe anxiety or stress.

- a source of pleasure and a way to pass the time.

Prone to routine and resistance to change

"The reality of an autistic person is a confusing, interconnected mass of events, people, places, sounds and pictures... Establishing a routine, a specific time, the same routes and rituals - all this helps to bring an unbearably chaotic life in order . Attempts to keep uniformity in everything reduce the monstrous fear a little" (Jolliffe (1992) in Howlin (1998), pp.201-202).

Many people with ASD have a very strong propensity for routine and monotony. Routines serve a very important function—they bring order, structure, and predictability to help manage anxiety. For this reason, disruption of a person's habitual routine can cause a lot of stress.

Sometimes even small changes cause great stress, such as moving from one activity to another. For other people, big events such as holidays, birthdays, or Christmas, which are associated with change and confusion, cause great anxiety. Unexpected changes are usually the hardest to deal with.

Unexpected changes are usually the hardest to deal with.

Some people with ASD have a daily routine that allows them to know exactly what is going to happen and when. However, the need for routine and monotony can go much further.

- Difficulty due to any change in the physical environment (for example, the arrangement of furniture in the room), the presence of new people, or the absence of familiar people

- Strong preferences for food (eg, only eats one particular color), clothing (wears only certain fabrics), or everyday objects (uses only one brand of soap or only one brand of toilet paper)

- the need for a rigid routine in relation to daily events, such as during meals or when going to bed. Such a routine can turn into real rituals when a person requires very detailed compliance with all the conditions and sequence of actions.

- verbal rituals where a person constantly asks the same questions and needs the same specific answer

- compulsive behavior, such as constantly washing hands or checking door locks.

This doesn't always mean you have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), but if you're concerned about this possibility, you should discuss it with your doctor.

This doesn't always mean you have obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), but if you're concerned about this possibility, you should discuss it with your doctor.

A person's dependence on routine can increase dramatically during times of life change, stress, or illness. During these periods, routines may become more detailed and ritualistic, as well as more meaningful (Attwood, 1998). In some cases, addiction to routines increases dramatically or reappears during adolescence.

Routines can have a huge impact on the lives of people with ASD, their families and loved ones, but it is possible to reduce a person's dependence on them.

Is it an obsession or just a hobby?

We all have hobbies or interests and (for the most part) we prefer to follow a certain routine. Here are five questions to help you distinguish between ordinary hobbies and interests and obsessive behavior:

- Does the person engage in this behavior when under extreme stress? Are there signs that the person is trying to resist this behavior? (For example, a person who is waving his arms tries to sit on his hands so that he does not wave them anymore).

- Can a person stop this behavior on their own?

- Does behavior affect a person's learning?

- Behavior limits a person's social opportunities?

- Does the behavior cause problems for other people, such as parents and family members? (Clements and Zarkowska, 2000)

If you answered yes to any of the above questions, it may be worth considering helping your child reduce their obsessive or repetitive behavior.

However, think about whether you will really help the child if you start to limit a particular type of behavior. Does this behavior really create serious problems for the child, you, or other family members?

Focus on developing skills that your child can use instead of repetitive or compulsive behavior. Try to understand the function of this behavior, and then make small, very gradual changes with consistency and persistence. Here are some ideas that might help you.

How to respond: understanding and intervention

Understanding the function of this behavior

Obsessions, repetitive behaviors and routines are often very important and meaningful for people with ASD - they help them cope with anxiety and gain some control over confusing and chaotic world. Other people need this behavior to cope with sensory problems. Try to identify what you think is causing this behavior and what purpose it serves.

Other people need this behavior to cope with sensory problems. Try to identify what you think is causing this behavior and what purpose it serves.

For example, is it difficult for your child to be in certain environments, such as the classroom at school? Maybe it's too bright in here? Can you turn off the lights and rely only on daylight?

Early Intervention

Repetitive behaviors, obsessions and routines are harder to change the longer they last. Behavior that may be acceptable for a young child may be unacceptable for an adult, but by then, it may no longer be amenable to change. For example, if a very young child is obsessed with shoes and touches shoes on strangers, then this is a small problem, but if a teenager or adult does the same, especially if it is about strangers, then obviously this will lead to trouble.

It is advisable that you start setting limits on repetitive behavior from an early age. Continue to monitor for new behaviors as your child grows.

How to respond: increase the structure of the environment

Try to make the child's environment and life (including social situations as possible) as structured as possible. This will increase the child's sense of control and reduce his anxiety. If anxiety decreases, then the need for repetitive behavior and routine will decrease over time. Here are some tips to help improve the structure of a child's life.

Visual support

Visual support, such as photographs, symbols, written lists, or objects, can be of great help to people with ASD.

A visual routine will help your child always see what is going to happen next (eg what is going to happen during the day). This routine increases predictability and helps the child feel ready for future events. A visual routine can reduce a child's dependence on routines they create on their own.

Visual aids such as timers, alarm clocks, and "timers" can help people with ASD understand the abstract concept of time, plan what they need to do and when to end an activity, and better understand the concept of waiting.

Visual support can also be helpful if your child is constantly asking the same question. One mother wrote down the answer to a question on paper, pinned it to the refrigerator, and every time her son asked a question, she told him to look at the refrigerator and read the answer. If your child can't read, you can use pictures instead of words.

Planning ahead

You can help your child cope with changes, stressful events or activities by planning ahead.

Life changes are inevitable, but people with ASD can take them very hard. It is not always possible to prepare for changes in advance, but try to warn your child about them as early as possible. Gradually introduce the idea of a new person, place, thing, or circumstance to help your child cope better with change. Try to talk about an upcoming event or activity when everyone is relatively relaxed and content. Visual presentation of this information can be a good idea, as your child can refer to it as often as needed.

Calendars can be used so that the child always knows how many days are left until an event such as New Year's Eve. This will help him feel ready. It is advisable to show the child photos of new places, objects or people in advance - so the child will know what to expect. For example, you can show a photo of his New Year's gift (children with ASD don't always like surprises), and if you go to an institution, you can show a photo of the building in which it is located.

Social stories can also be helpful. These are short stories, often with pictures, that describe different situations or activities. The use of social stories allows people with ASD to know in advance what to expect.

Pre-planning also includes the structuring of the environment. For example, a student with ASD may sit at the computer in the library if it is too difficult for him to be on the playground. And if the child suffers from sensory hypersensitivity, then exposure to sensory stimuli, such as loud noises (school bell) or smells (perfume or soap), can be minimized in advance.

In addition, a more organized environment reduces boredom, which can be one of the causes of repetitive behavior. You can prepare pleasant and soothing activities for your child in advance to switch to them if he starts to show signs of boredom or stress.

How to Respond: Skill Development

Self-Regulation Skills

Self-Regulation Skills are any activities that allow your child to manage their emotions and behavior.

If you help your child recognize when they are feeling stressed or anxious and use alternative actions (eg, relaxation exercises, seeking parental help), repetitive and ritualistic behavior will decrease over time.

Research shows that if a person becomes more aware of their obsessive or repetitive behavior, then it is significantly reduced. The same applies to people with severe intellectual disabilities (Koegel et al, 1995 in Howlin, 1998).

Social skills training

Social skills training, such as how to start and end a conversation, what to talk about with other people, and how to identify “cues” in another person’s behavior (for example, if another person raises their eyebrows, it means they are wants to say something or object to your words), helps a person with ASD to become more confident in communicating with other people. Such confidence reduces the need for intrusive talk about the same subject or special interest.

Such confidence reduces the need for intrusive talk about the same subject or special interest.

Coping with change

We have already discussed how you can prepare your child for change. However, if unexpected changes occur and your child finds it difficult to cope, try to switch him to a calming activity, or encourage him to use simple calming techniques, such as breathing exercises.

You can use praise and rewards each time your child copes well with change. In the long run, this will help the child increase their tolerance for change.

Try alternative activities

One way to stop a child's repetitive behavior is to find another, equally enjoyable activity that will perform the same function. Here are some examples:

- If your child is rocking for sensory stimulation, you might want to try the swing.

- If a child waves his fingers in front of his face for visual stimulation, he can play with a kaleidoscope and a bubble gun.

- If the child puts non-edible objects in his mouth, you can give him a bag of edible alternatives (which provide a similar sensory experience), such as raw pasta or vermicelli, seeds or nuts.

- If a child smears his feces, you can give him plasticine as a substitute.

How to Respond: Set Limits

Setting limits on repetitive behaviors, routines and obsessions is a very important and often critical way to minimize their impact on your child's life. There are several types of restrictions:

- restrict objects (you can only carry five stones in your pocket)

- limit time (you can only watch Thomas the Tank Engine DVD for 20 minutes twice a day)

- limit places (you can rotate in one place only at home).

All people involved in your child's life should be consistent in setting limits. Develop the most specific rules: when, where, with whom and for how long this or that behavior is allowed. You can present this information visually. The main focus should be on when your child can practice this behavior - this will reduce anxiety associated with accessing obsessions or favorite activities.

The main focus should be on when your child can practice this behavior - this will reduce anxiety associated with accessing obsessions or favorite activities.

Here is one example of setting limits:

Identify a repetitive behavior, obsession, or routine that makes you anxious. Jane loves to talk about trains. Jane now starts talking about trains within the first ten seconds of any conversation, and continues to talk about trains for an average of 15 minutes.

Think about what reasonable limits your child can handle for this behavior. Behavioral changes will succeed and not cause much stress to your child only if you start small and progress very slowly. Jane is allowed to talk about trains no earlier than 20 seconds after the start of the conversation and no longer than 5 minutes. She is also undergoing social skills training.

Gradually increase limits and set new limits. Jane can talk about trains no more than three times a day. Then, Jane is only allowed to talk about trains three times a day with her family members. The ultimate goal is for Jane to only talk about trains with family members, no longer than one minute and no more than twice a day.

The ultimate goal is for Jane to only talk about trains with family members, no longer than one minute and no more than twice a day.

If you are limiting obsessions or repetitive behaviors, then you need to think about what your child will do instead of this behavior: maybe he should join a hobby group or club; start going to the sports section; enroll in training courses.

How to respond: use obsessions

Obsessions can be used to enhance a child's skills and interests, increase their self-esteem and motivate them to interact with others. You can analyze this or that obsession and think about how to make it more functional. Here are a few examples:

- An obsessive interest in computers can develop into an education and a successful job in the IT field.

- If a person's special interest is historical dates, then he can join a history club and meet people who have similar interests.

- A person with comprehensive knowledge of a sport or music can become a "star" in a fan club.

- An obsessive interest in garbage can develop into an interest in waste disposal and the problem of sorting garbage, the child may begin to sort garbage and take it to recycling.

- An interest in a certain kind of sound can be reborn as an interest in playing a musical instrument.

- A strong passion for order and arranging objects in one line can develop into housekeeping skills.

You can also use obsessions to motivate and reward your child. For example, after the least favorite activity (doing homework), the child gets the opportunity to do what he loves (for example, extra time at the computer).

If you and other people in the child's environment begin to show interest in his favorite topic or activity, this will help build relationships and increase the child's self-esteem.

"Attention to the special interest of the child will allow parents to improve communication, and to a degree that previously seemed impossible" - a young man with Asperger's syndrome.

How to Respond: Summary

- Ask yourself if this obsession, routine or repetitive behavior is really limiting the child's life opportunities, causing stress or discomfort and interfering with learning. If not, why interfere?

- Think about the function of a repetitive behavior, routine, or obsessive interest. What does your child get from them?

- Intervene early: Establish gradual limits on repetitive behaviors or compulsive interests from an early age (and watch for new types of such behaviors).

- Try to make the child's world as structured and predictable as possible. Try to use visual support (such as a daily routine), social stories, and pre-planning strategies to prepare your child for a potentially stressful event. These strategies can reduce dependence on routines and repetitive behaviors.

- Help your child develop new skills, such as learning social skills, applying relaxation techniques, or recognizing one's own emotions.