Articles on dysfunctional families

Dysfunctional Families and Their Psychological Effects

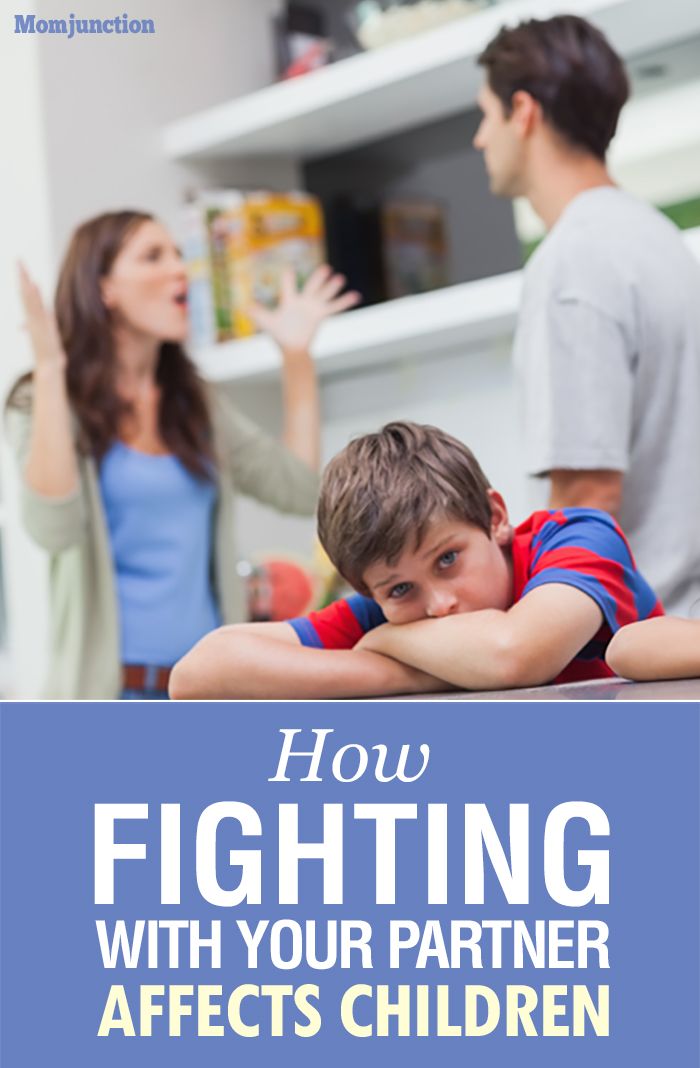

When the lockdown protocols were enforced earlier this year, our freedom, routine and responsibilities within households were disrupted. Along with this, increased uncertainty, financial stress and burden of care have lowered our window of tolerance. For many, it has opened old wounds and led to persistent conflict at home. Children are forced to experience strained family interactions, day in and day out, without the solace of distraction and distance.

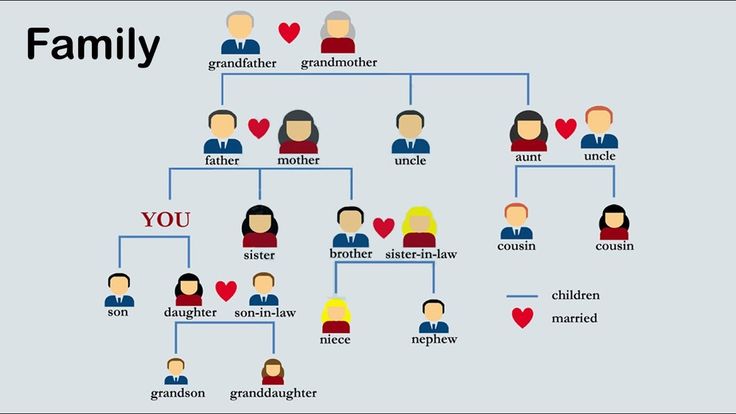

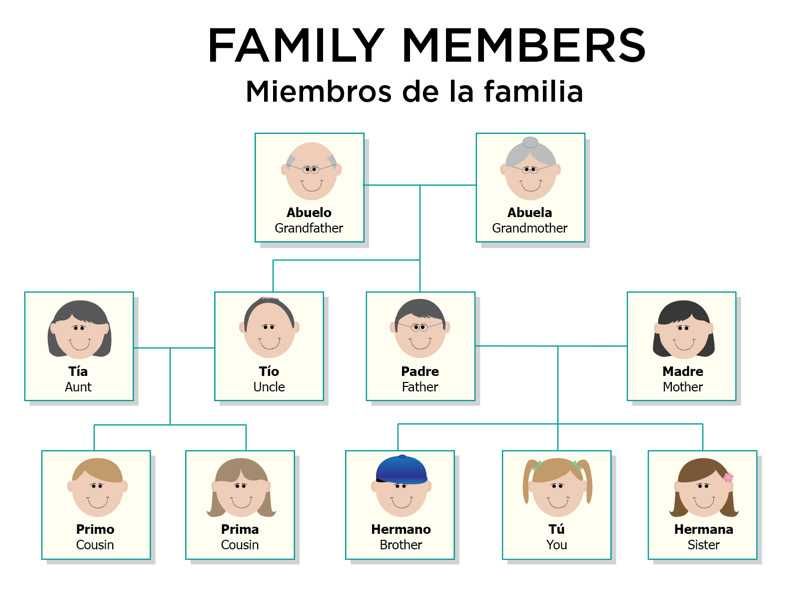

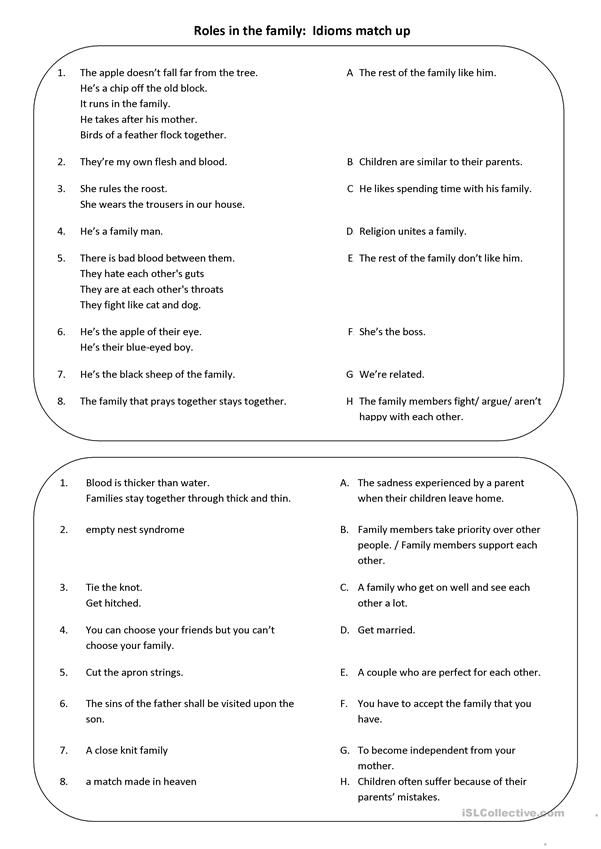

There is a great degree of variability in how interactions and behaviors occur within homes, and the pattern of these interactions form the core of our family dynamic (Harkonen, 2017). Families have a unique set of dynamics that affect the way each member thinks and relates to themselves, others and the world around them. Several factors including the nature of parent’s relationship, personality of family members, events (divorce, death, unemployment), culture and ethnicity (including beliefs about gender roles), influence these dynamics.

The list is endless, and it is no surprise that growing up in an open, supportive environment is the exception, rather than the norm.

It’s important to disclaim that the idea of a perfect parent/family is a myth. Parents are human, flawed and experiencing their own concerns. Most children can deal with an occasional angry outburst, as long as there is love and understanding to counter it. In “functional” families, parents strive to create an environment in which everyone feels safe, heard, loved and respected. Households are often characterized by low conflict, high levels of support and open communication (Shaw, 2014). This helps children navigate physical, emotional and social difficulties when they are young, and has lasting impacts as they transition into adulthood.

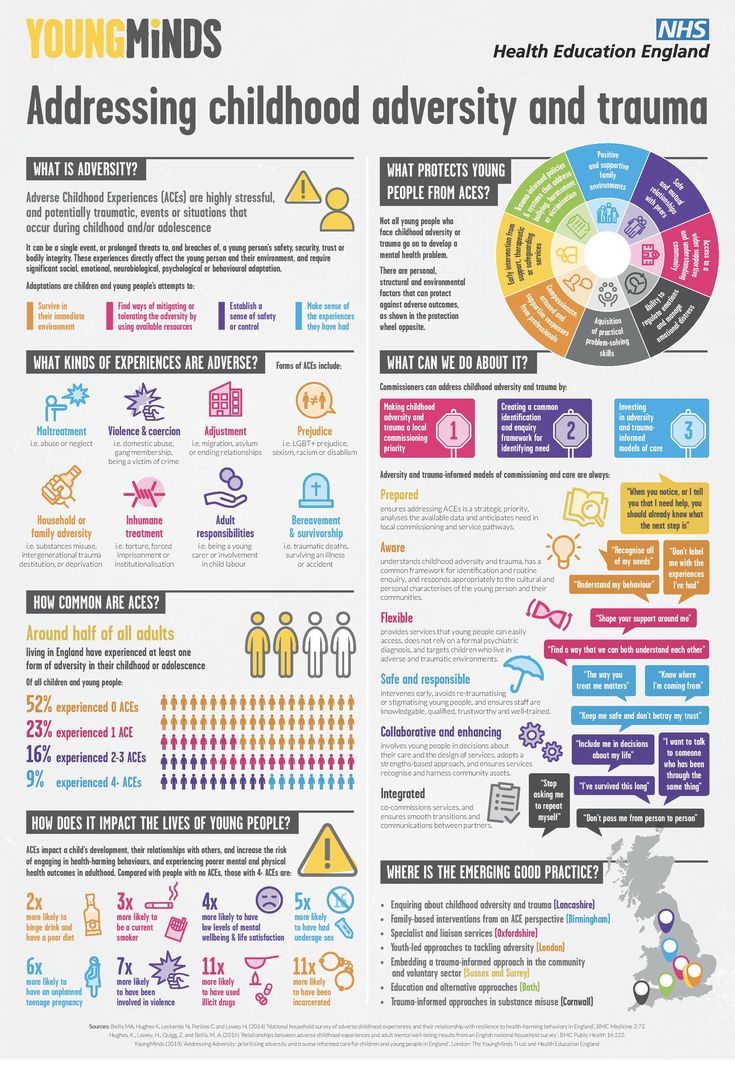

Alternatively, growing up in a dysfunctional family can leave children emotionally scarred, and affect them throughout their lives. Hurtful family environments may include the following (Hall, 2017):

- Aggression: Behaviors typified by belittlement, domination, lies and control.

- Limited affection: The absence of physical or verbal affirmations of love, empathy and time spent together.

- Neglect: No attention paid to another and discomfort around family members.

- Addiction: Parents having compulsions relating to work, drugs, alcohol, sex and gambling.

- Violence: Threat and use of physical and sexual abuse.

For children, families constitute their entire reality. When they are young, parents are godlike; without them they would be unloved, unprotected, unhoused and unfed, living in a constant state of terror, knowing they will be unable to survive alone. Children are forced to accommodate and enable chaotic, unstable/unpredictable and unhealthy behaviors of parents (Nelson, 2019).

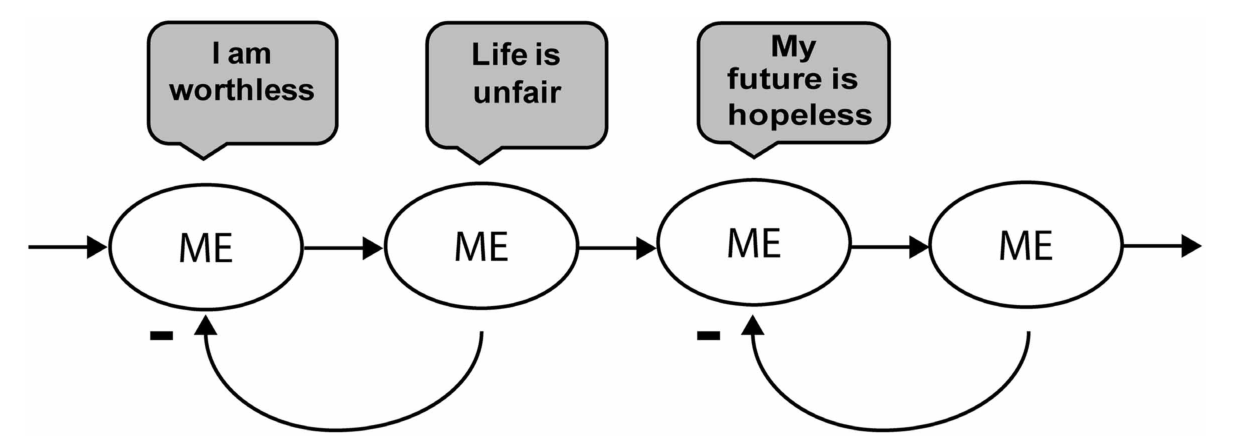

Unfortunately, children don’t have the sophistication to understand and verbalize their experiences, discriminate between healthy and unhealthy behaviors and make sense of it all. They may interpret the situation to fit the belief of normalcy, further perpetuating the dysfunction (e. g., “No, I wasn’t beaten. I was just spanked” or “My father isn’t violent; it’s just his way”). They may even accept responsibility for violence, to fit their reality. The more they do this, the greater is their likelihood of misinterpreting themselves and developing negative self-concepts (e.g., “I had it coming. I was not a good kid”).

g., “No, I wasn’t beaten. I was just spanked” or “My father isn’t violent; it’s just his way”). They may even accept responsibility for violence, to fit their reality. The more they do this, the greater is their likelihood of misinterpreting themselves and developing negative self-concepts (e.g., “I had it coming. I was not a good kid”).

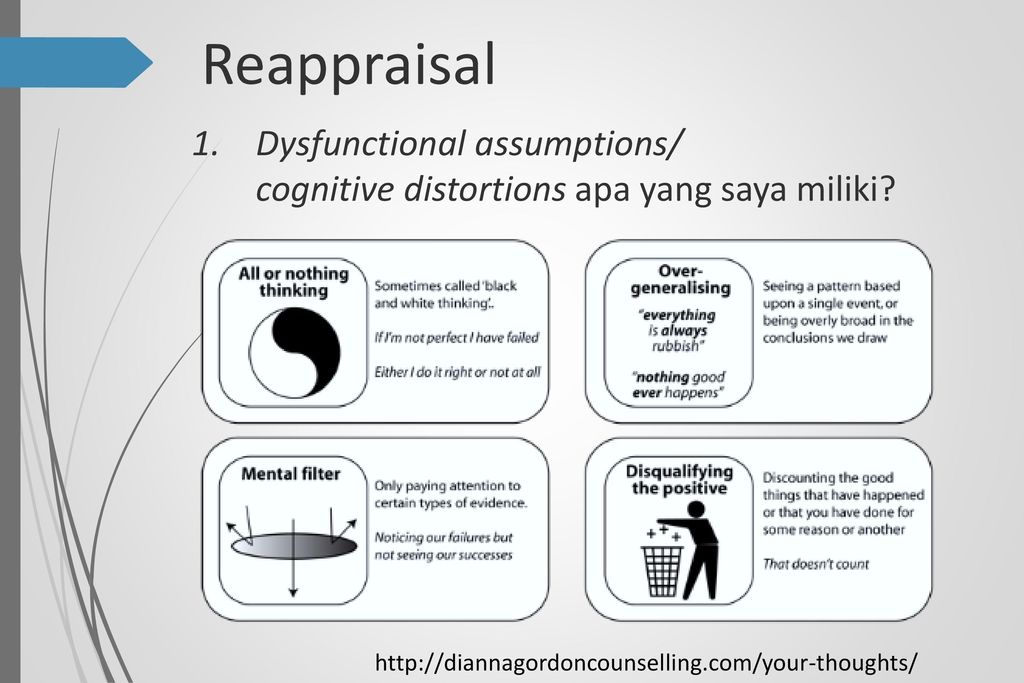

During their younger years, children form certain beliefs and carry them, unchallenged, into adulthood. These beliefs are influenced by their parents’ actions and statements and are often internalized, for instance, “children should respect their parents no matter what,” “it’s my way or no way” or “children should be seen, not heard.” This forms the soil from which toxic behavior grows and may be communicated directly or disguised as words of advice, expressed in terms of “shoulds”, “oughts” and “supposed tos.”

Spoken beliefs are tangible but can be wrestled with. For instance, a parental belief that divorce is wrong, might keep a daughter in a loveless marriage, however, this can be challenged. Unspoken beliefs are more complicated; they exist below our level of awareness and dictate basic assumptions of life (Gowman, 2018). They may be implied by childhood experiences, for example, how your father treated your mother or how they treated you, encouraging you to believe ideas such as “women are inferior to men” or “children should sacrifice themselves for their parents.”

Unspoken beliefs are more complicated; they exist below our level of awareness and dictate basic assumptions of life (Gowman, 2018). They may be implied by childhood experiences, for example, how your father treated your mother or how they treated you, encouraging you to believe ideas such as “women are inferior to men” or “children should sacrifice themselves for their parents.”

As with beliefs there are unspoken rules, pulling invisible strings and demanding blind obedience, e.g., “don’t lead your own life,” “don’t be more successful than your father,” “don’t be happier than your mother” or “don’t abandon me.” Loyalty to our family binds us to these beliefs and rules. There may be a marked gap between parents’ expectations/demands and what children want for themselves. Unfortunately, our unconscious pressure to obey almost always overshadows our conscious needs and desires, and leads to self-destructive and defeating behaviors (Forward, 1989).

There is variability in dysfunctional familial interactions — and in the kinds, severity and regularity of their dysfunction. Children may experience the following:

Children may experience the following:

- Being forced to take sides during parental conflict.

- Experiencing “reality shifting” (what is said contradicts what is happening).

- Being criticized or ignored for their feelings and thoughts.

- Having parents who are inappropriately intrusive/involved or distant/uninvolved.

- Having excessive demands placed on their time, friends or behaviors — or, conversely, receive no guidelines or structure.

- Experiencing rejection or preferential treatment.

- Being encouraged to use alcohol/drugs.

- Being physically beating.

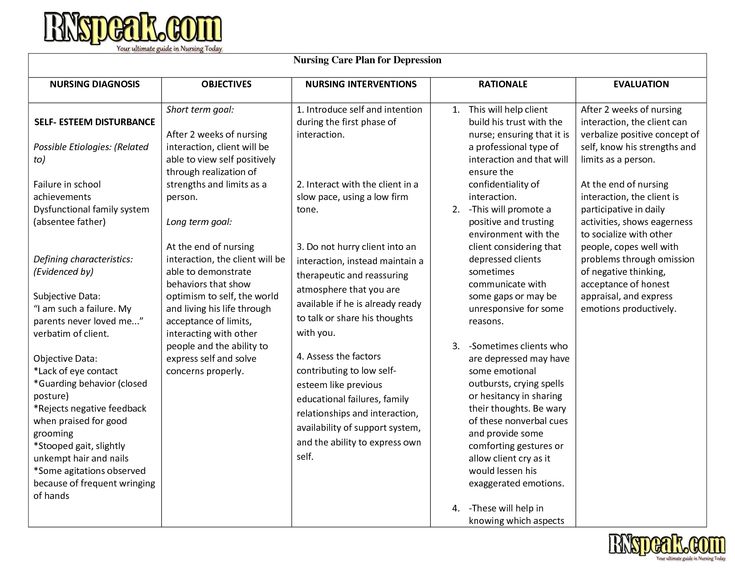

Abuse and neglect affect the child’s ability to trust the world, others and themselves. Additionally, they grow up without a frame of reference for what is normal and healthy. They may develop traits that they struggle with throughout their adult lives, and the effects are many. They may not know how to live without chaos and conflict (this becomes a lifestyle pattern) and get bored easily (Lechnyr, 2020). Children robbed of their childhood have to “grow up too fast.” As a result, they are disconnected from their needs and face difficulty asking for help (Cikanavicious, 2019). Children, who were constantly ridiculed, grow up to judge themselves harshly, lie and constantly seek approval and affirmation. Children may fear abandonment, believe they are unlovable/not good enough and feel lonely/misunderstood. As adults, they face difficulty with forming professional, social and romantic bonds, and are viewed as submissive, controlling, overwhelming or even detached in relationships (Ubaidi, 2016). To numb their feelings, they may abuse drugs or alcohol and engage in other risky behaviors (e.g., reckless driving, unsafe sex) (Watson et al., 2013).

Children robbed of their childhood have to “grow up too fast.” As a result, they are disconnected from their needs and face difficulty asking for help (Cikanavicious, 2019). Children, who were constantly ridiculed, grow up to judge themselves harshly, lie and constantly seek approval and affirmation. Children may fear abandonment, believe they are unlovable/not good enough and feel lonely/misunderstood. As adults, they face difficulty with forming professional, social and romantic bonds, and are viewed as submissive, controlling, overwhelming or even detached in relationships (Ubaidi, 2016). To numb their feelings, they may abuse drugs or alcohol and engage in other risky behaviors (e.g., reckless driving, unsafe sex) (Watson et al., 2013).

Perhaps most serious of all, these individuals continue the cycle by developing their own parenting problems and reinforcing the dysfunctional dynamic (Bray, 1995). Being aware of the dysfunctional patterns of our past and how they affect how we think and act in the present is the critical first step.

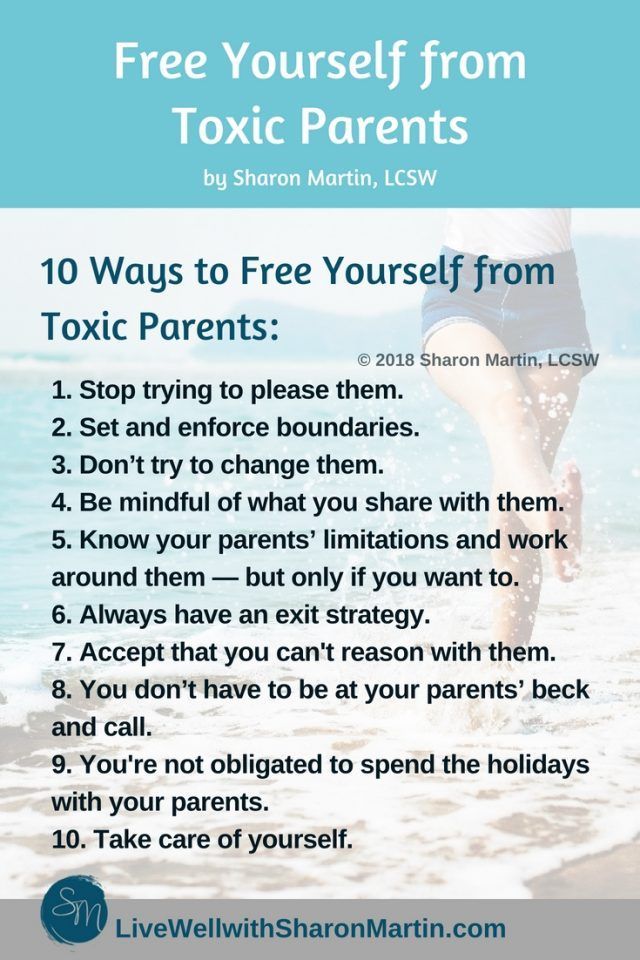

- Name painful or difficult childhood experiences.

- Recognize you have power over your life.

- Identify behaviors and beliefs you would like to change.

- Be assertive, set boundaries and practice non-attachment.

- Find a support network.

- Seek psychological help.

For parents:

- Heal from your own trauma.

- Be kind, honest and open-minded — and listen.

- Create an environment of respect, safety and privacy.

- Model healthy behavior and practice accountability.

- Give clear guidelines and factual information.

- Learn how to apologize.

- Be gentle with teasing, sarcasm, etc.

- Allow children to change and grow.

- Enforce rules that guide behavior but do not regulate one’s emotional and intellectual life.

- Spend time together as a family.

- Know when to ask for help.

References:

- Härkönen, J., Bernardi, F. & Boertien, D. (2017). Family Dynamics and Child Outcomes: An Overview of Research and Open Questions.

Eur J Population 33, 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9424-6

Eur J Population 33, 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-017-9424-6 - Shaw, A. (2014). The Family Environment and Adolescent Well-Being [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/publications/the-family-environment-and-adolescent-well-being-2

- Dorrance Hall, E. (2017). Why Family Hurt Is So Painful Four reasons why family hurt can be more painful than hurt from others [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/conscious-communication/201703/why-family-hurt-is-so-painful

- Nelson, A. (2019). Understanding Fear and Self-Blame Symptoms for Child Sexual Abuse Victims in Treatment: An Interaction of Youth Age, Perpetrator Type, and Treatment Time Period. Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 89. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/89

- Gowman, V. (2019). When Children Believe “I Am Wrong”: The Impact Developmental Trauma Has on Belief Systems and Identity [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.vincegowmon.

com/when-children-believe-i-am-wrong/

com/when-children-believe-i-am-wrong/ - Forward, S., & Buck, C. (1989). Toxic Parents: Overcoming Their Hurtful Legacy and Reclaiming Your Life. NY, NY: Bantam.

- Cikanavicius, D. (2019). The Effects of Trauma from “Growing up Too Fast” [blog post]. Retrieved from https://blogs.psychcentral.com/psychology-self/2019/12/trauma-growing-up-fast/

- Al Ubaidi, B.A. (2017). Cost of Growing up in Dysfunctional Family. J Fam Med Dis Prev, 3(3): 059. doi.org/10.23937/2469-5793/1510059

- Lechnyr, D. (2020). Wait, I’m not Crazy?! Adults Who Grew Up in Dysfunctional Families [blog post]. Retrieved from https://www.lechnyr.com/codependent/childhood-dysfunctional-family/

- Al Odhayani, A., Watson, W. J., & Watson, L. (2013). Behavioural consequences of child abuse. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien, 59(8), 831–836.

- Bray, J.H. (1995). 3. Assessing Family Health And Distress: An Intergenerational-Systemic Perspective [Family Assessment].

Lincoln, NB: Buros-Nebraska Series on Measurement and Testing. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=burosfamily

Lincoln, NB: Buros-Nebraska Series on Measurement and Testing. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1006&context=burosfamily

Cost of Growing up in Dysfunctional Family

*Corresponding author: Basem Abbas Al Ubaidi, Consultant Family Physician, Ministry of Health; Assistant Professor, Arabian Gulf University, Kingdom of Bahrain, E-mail: [email protected]

Citation: Al Ubaidi BA (2017) Cost of Growing up in Dysfunctional Family. J Fam Med Dis Prev 3:059. doi.org/10.23937/2469-5793/1510059

Copyright: © 2017 Al Ubaidi BA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

The definition of a family dynamic is the scheme of family members' relations and interactions including many prerequisite elements (family arrangements, hierarchies, rules, and patterns of family interactions). Each family is unique in its characteristics; having several helpful and unhelpful dynamics. Family dynamics will ultimately influence the way young people view themselves/others and the world. It will also impact their relationships/behaviors and their future wellbeing. The victims of dysfunctional families may have determined deprived guilty feelings.

Each family is unique in its characteristics; having several helpful and unhelpful dynamics. Family dynamics will ultimately influence the way young people view themselves/others and the world. It will also impact their relationships/behaviors and their future wellbeing. The victims of dysfunctional families may have determined deprived guilty feelings.

Victimized children growing up in a dysfunctional family are innocent and have absolutely no control over their toxic life environment; they grew up with multiple emotional scarring caused by repeated trauma and pain from their parents' actions, words, and attitudes. Ultimately, they will have a different growth and nurture of their individual self. The influenced individuals will resume various parenting roles rather than enjoying their childhood, vital parts of their childhood are missing, which will eventually have a harmful effect that extends to their adult life. Victimized adults tend to attempt escaping their past pain, trauma by practicing more destructive behaviors such as increase dues of alcohol, drug abuse or forced to repeat the mistreatment that was done to them. Others had felt inner nervousness or temper and feelings without realizing the reasons behind it [1]. They frequently reported difficulties in forming and sustaining friendly relationships, keeping a positive self-esteem, struggling in trusting others, distress in control loss, and denying their own feelings/reality [2]. Frequently, healthy families tend to return to their normal functioning after the life/family crisis passes. Conversely, in a dysfunctional family, problems tend to be long-lasting because children do not get their previous needs; therefore the negative, pathological parental behavior tends to be dominant even in their adult's lives [2].

Others had felt inner nervousness or temper and feelings without realizing the reasons behind it [1]. They frequently reported difficulties in forming and sustaining friendly relationships, keeping a positive self-esteem, struggling in trusting others, distress in control loss, and denying their own feelings/reality [2]. Frequently, healthy families tend to return to their normal functioning after the life/family crisis passes. Conversely, in a dysfunctional family, problems tend to be long-lasting because children do not get their previous needs; therefore the negative, pathological parental behavior tends to be dominant even in their adult's lives [2].

Healthy families are not always ideal or perfect. They may infrequently possess some of the characteristics of a dysfunctional family; but not all the time [3].

The dysfunctional family is an important topic in the field of sociology facing many Primary Care Physicians (PCPs), while there is little training in family therapy on how PCPs could and should deal with family conflicts [3].

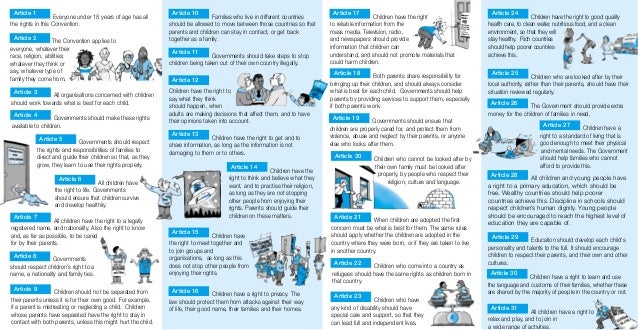

1) Allow and accept emotional expressions of an individual's character and interests [3].

2) Obvious and consistent rules in the family and boundaries between individuals are honored.

3) Consistently treating members with respect and build a level of flexibility to meet the individual’s needs.

4) All family members feel safe and secure (no fear from emotional, verbal, physical, or sexual abuse).

5) Parents provide care for their children (not expecting their children to take their parental responsibilities).

6) Responsibilities given are appropriate to their age, flexible and forgiving to a child's mistakes.

7) Perfection is unattainable, unrealistic, besides potentially dull and sterile.

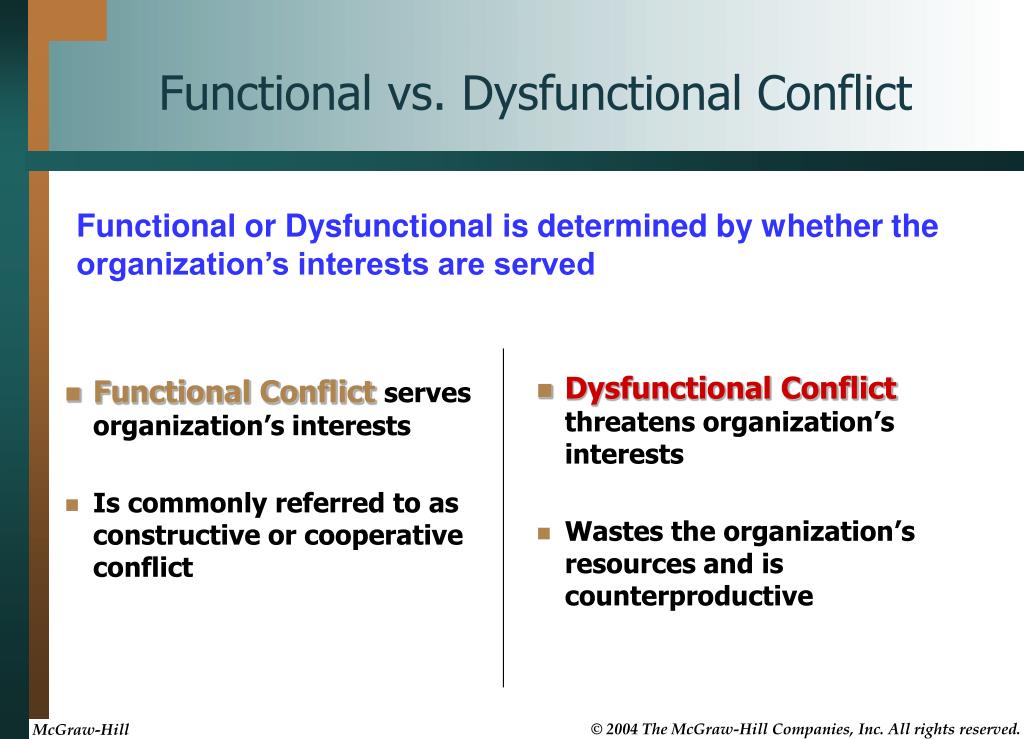

"Family Systems Theory", in contrast to the "Traditional Individual Therapy", views problems in a more circular manner. This theory has a 'systemic perspective' rather than a 'linear manner', in which each individual in the family influences the others. Each family member's viewpoint is valid in their perceptions [4].

This theory has a 'systemic perspective' rather than a 'linear manner', in which each individual in the family influences the others. Each family member's viewpoint is valid in their perceptions [4].

Understanding family problems requires the assessment of several patterns of family interactions in context of their family system, with an emphasis on what is happening, rather than why it’s occurring. PCPs should move away from blaming one person for the dysfunctional dynamic, and attempt to find alternative solutions [5].

PCPs should be able to identify and manage early signs of a dysfunctional family too, by focusing on families that submerged in child abuse and neglect or domestic violence. However, many families are reluctant to believe or accept that they are a part of what is classified as a dysfunctional family [6].

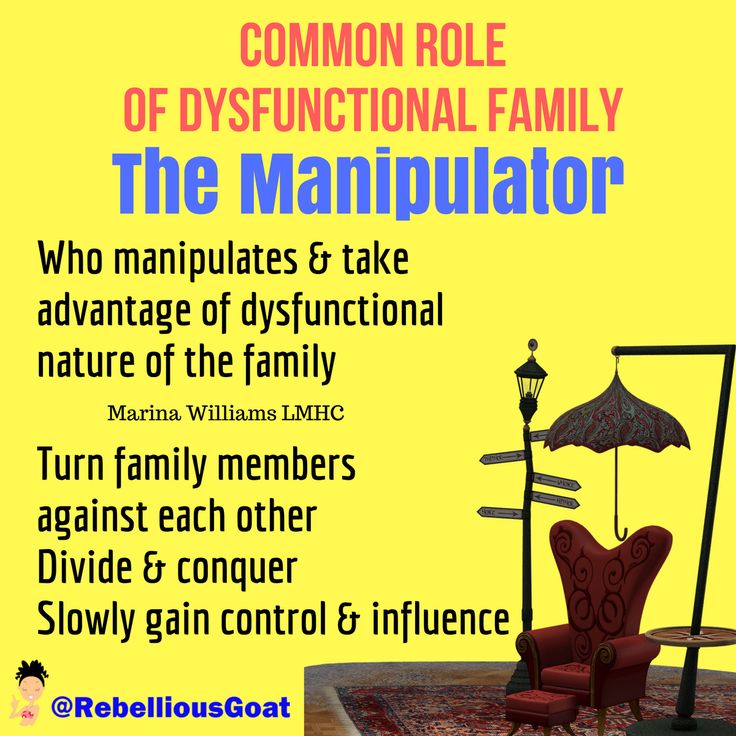

The Abusive Parent

One or both parents have a history of an offending (words and action) form of child abuse. The abusive behaviors are either physical (beating, slapping, punching or sexual) or non-physical (verbal and emotional abuse) [3-9].

The abusive behaviors are either physical (beating, slapping, punching or sexual) or non-physical (verbal and emotional abuse) [3-9].

The Strict Controlling and or Authoritarian Parent

One or both parents have a history of being a controlling parent (fails or refuses to give their children space to flourish) by not allowing them to make their own choices or decisions appropriate to their age. The parents are usually driven and motivated by unexplained horror and refute any children choices and decision for themselves.

The children will eventually feel resentful and hold inadequate power to think appropriately or make their own personal decisions.

The Soft Parent

One or both parents are intentionally or unintentionally soft parents (Unsuccessful in setting rules, regulations and boundaries in the household).

The large and Extended Families

A parent can't give attention to cover all the family’s wants and needs; correspondingly they will have conflicting guidance from extended families.

Personality Disorder in Family Members

Late diagnosed personality disorder in one or both parents will eventually affect normal family dynamics.

A chronically Sick or Disabled Child in the Family

Any sick child in a family will have a detrimental effect on all family members, and then family care automatically shifts to sick children, whereas the needs of others are ignored.

Unfortunate Life Events

Events that negatively influence family dynamics are a parent's affair, divorce, trauma, death and sudden job termination.

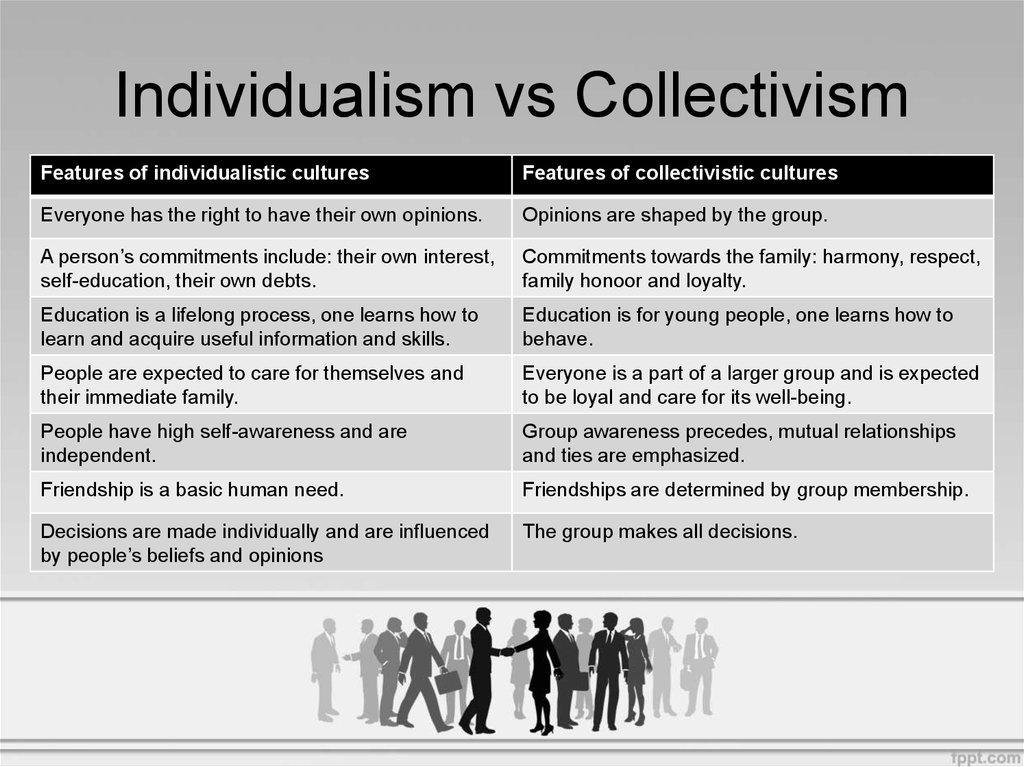

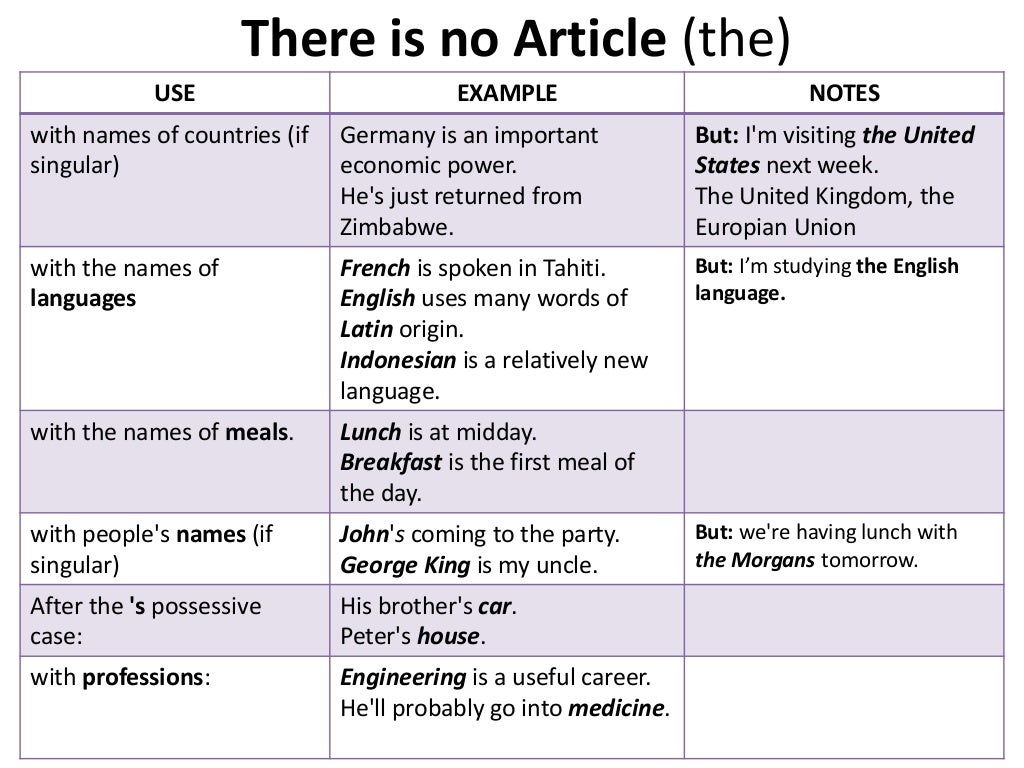

Family Values, Culture and Ethnicity

This usually causes negative effects on the beliefs of families in cases such as gender roles, parenting practices, and the power of each individual family member.

Insecure Nature of Family Attachments

Secure feelings have a positive effect on the family dynamic; in contrary, insecure feelings will harmfully affect family dynamics.

Dynamics of Previous Dysfunctional Generation

Previous dysfunctional families always have a toxic effect other family generations.

Systematic Stability and or Instability

Such as social, economic, political and financial factors, these factors positively or negatively influence the nature of the family dynamic.

The Deficient or Absent Parent (Parental In adequacy)

One or both parents are purposefully or in advertently deficient, parents as they fail to act appropriately or neglecting their children's physical or emotional needs (e.g. parent suffering from mental/psychological disease and not capable to provide the child’s needs) [6,10].

The children will, ultimately, take a parent' role and the responsibilities (unofficial caretaker) of their younger siblings.

Substance Abuse and or Addicted Parent

One or both are intentionally or involuntarily have a substance abuse or addiction. The family’s life is usually unpredictable and unsuccessful by addicted parents. The hazy rules of the addicted parent will weaken his ability to fulfill promises so the parent will neglect both the physical and emotional needs of their children. The affected vulnerable children from addicted parents are at high risk of either child abuse or future sexual exploitation.

The family’s life is usually unpredictable and unsuccessful by addicted parents. The hazy rules of the addicted parent will weaken his ability to fulfill promises so the parent will neglect both the physical and emotional needs of their children. The affected vulnerable children from addicted parents are at high risk of either child abuse or future sexual exploitation.

"Chronic conflict family"

When every member in the family argues with the other in harmful ways that leaves wounds to fester. The causes come from corrupt parenteral style (abusive, authoritarian). Prolonged conflict can damage a child's neurochemistry (breeds stress/insecurity and loss of a child's attachment) [11].

"Pathological households"

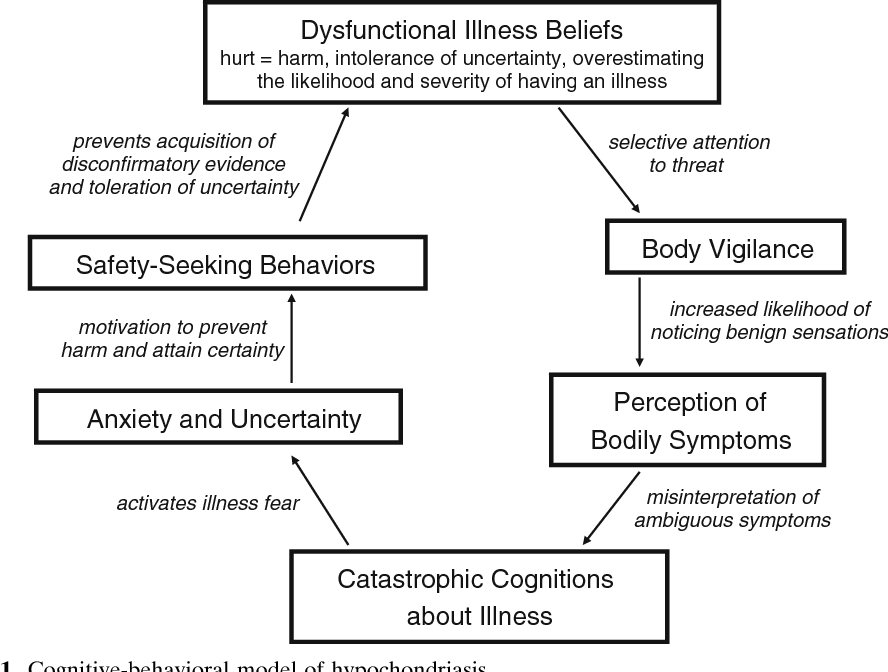

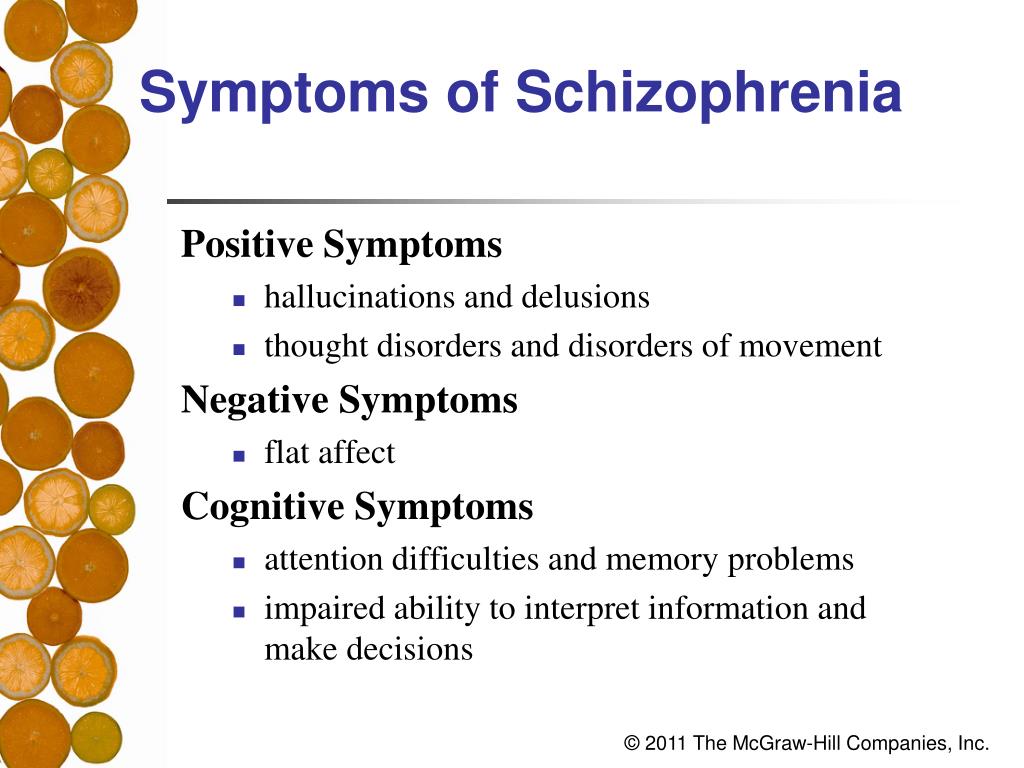

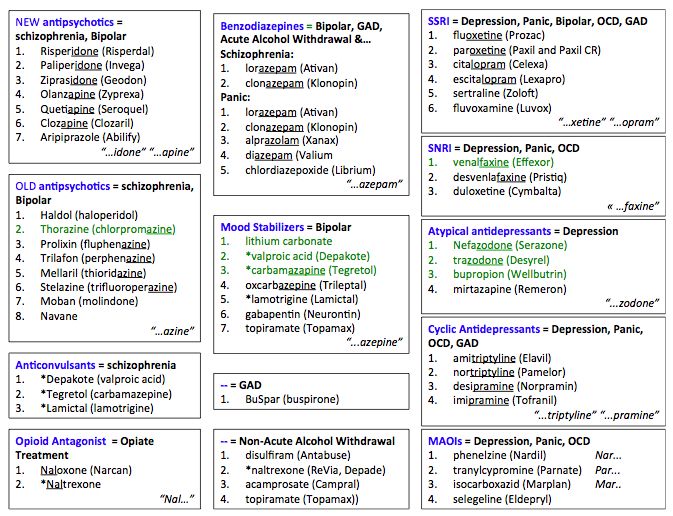

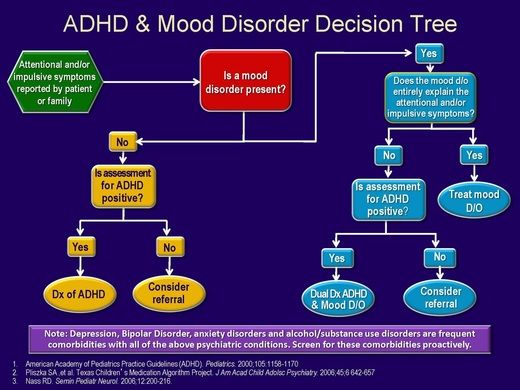

It is one where severe psychological, mental health disorders and/or impaired parent from substance abuse/drug addiction; is present over one or both parents (having a diagnosable schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) or there is a personality disorder in the parent. The family roles are usually reversed (children are more responsible and in charge of daily functioning) because of their one or two impaired parents. Unhealthy pathology is sometimes contagious (breeds problems or social deficiencies in the children).

The family roles are usually reversed (children are more responsible and in charge of daily functioning) because of their one or two impaired parents. Unhealthy pathology is sometimes contagious (breeds problems or social deficiencies in the children).

"The chaotic household''

It is a place where children are poorly looked after with the busy and non-present parents or parental inadequacy. It has no clear regulation/rules or expectations, and no consistency. Parents may be moving in and out of the house and their traditional caretakers are inconsistent. Older siblings often develop early parental figures; therefore family attachment and security is often severely threatened. School age group victims usually have concentration problems and discipline difficulties. Many future secondary abuse & neglect issues commonly arise in adult age group.

''The dominant-submissive household''

It is one ruled by a dictator parent, with no consideration to the wishes or feelings of the other family members. The other partner is usually depressed, with a lot of negative, angry emotions (one parent strict, controlling, the other is soft, passive). All family members are extremely unhappy and dissatisfied with life from an unhealthy relationship, but are passively obedient to the dominant adult and show little open revolt. This shows severe long-term negative consequences; as one parent tries to control others without considering their personal needs.

The other partner is usually depressed, with a lot of negative, angry emotions (one parent strict, controlling, the other is soft, passive). All family members are extremely unhappy and dissatisfied with life from an unhealthy relationship, but are passively obedient to the dominant adult and show little open revolt. This shows severe long-term negative consequences; as one parent tries to control others without considering their personal needs.

"Emotionally distant families"

It is families with social/cultural background which don't know how to show love and affection (show little or no warmth towards each other). Children learn from their parents that feelings should be repressed (seem uncomfortable opening up to each other). It brings insecure or non-existent attachment, difficulties in child's identity and self-esteem issues. Emotionally Distant Families may be one of the least obvious dysfunctional family settings.

1) Lack of empathy, respect and boundaries towards family members [7].

2) Borrowing or destroying personal possessions without consent.

3) Invading personal privacy without permission.

4) Extreme conflict and hostility in the family environment (verbal and physical assault) between parent-child or sibling-sibling assaults against each other.

5) Role reversal or role confusion: both parent and child change their roles (early paternalism).

6) Restricted friendships and relationships with outsiders lead to family isolation.

7) Secrecy, denial, rigid rules from extremist (religious fundamentalist).

8) Perfectionism and unrealistic expectations to their children (parent's expectation beyond their child's skills, abilities and development).

9) Emotional, verbal abuse, ridicules behavior and blaming each family member.

10) Stifled speech and emotion (Not allowing their children to have own opinions and neither accepted sadness or happiness emotion).

11) Using children as weapons against each other for revenge attitude.

12) Conditional emotional love and support are always pathological.

All families have had some element of family dysfunction from time to time; this is perfectly true as no family can be perfect all the time. PCPs should become concerned when a multitude of negative signs of a dysfunctional family exists without any proper action that ultimately lead to significant harm to family members [7].

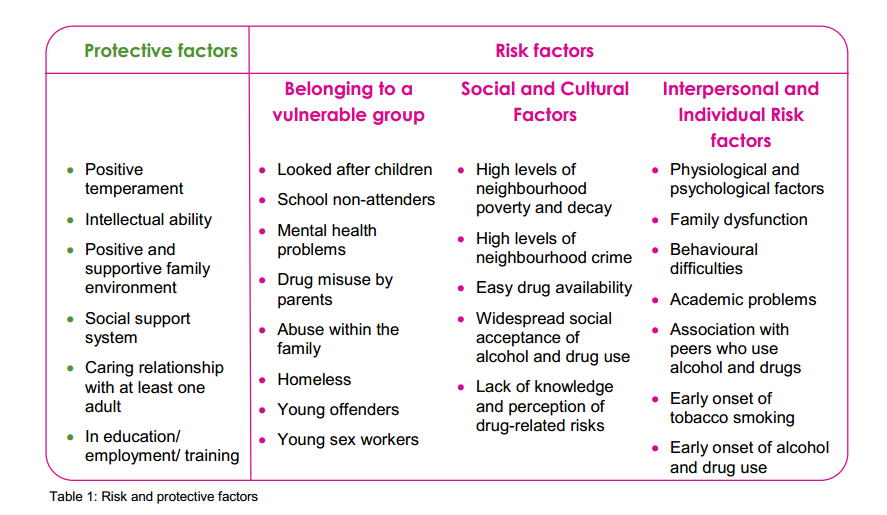

Individuals from dysfunctional families tend to have a higher incidence of behavioral disorder, so PCPs should identify the early signs and symptoms of dysfunctional family such as [12]:

1. Low self-esteem and uncompassionate judgment of others and themselves, so family members try to obscure pain by being controlling and disrespectful.

2. Isolated feelings and uneasy around authority figures.

3. Need for approval enquirers to satisfy their deficit.

4. Intimidated feelings towards any angry situation and personal criticism (feel anxious and overly sensitive).

5. Less attracted to healthy, caring people; instead they are more apt to unconsciously seek out another "dysfunctional family" (select to have relationships with emotionally detached people/attracted to other victims in their love and friendship relationships).

6. Less responsible for their own problems, so they are behaving with super-responsibility or super-irresponsibility. They tried to solve others’ problems/expected others to be responsible for their own problems.

7. Guilty feeling when devoting care to themselves; instead they are over caring for others.

8. Difficulties in expressing of their children feelings (denied, minimized or repressed feelings) and are usually unaware of the unhealthy future impact.

9. Dependent personalities/with a feeling of irrational fear of terrified rejection or abandonment; so they stay in harmful jobs/relationships and accompanied by the inability end hurtful relationships or prevent them from entering healthy and rewarding ones.

10. Hopelessness and helplessness feelings because of persistent denial, isolation, uncontrolled and misplaced guilt.

11. Difficulties in intimate relationships (insecure and lacked of trust in others, no clear boundaries and have become trapped with their partner’s needs and emotions).

12. Difficulties in following tasks from beginning to end and having a strong need to be in control (over-reacted in uncontrolled change), they tend to have impulsive action before considering alternative behaviors or possible consequences.

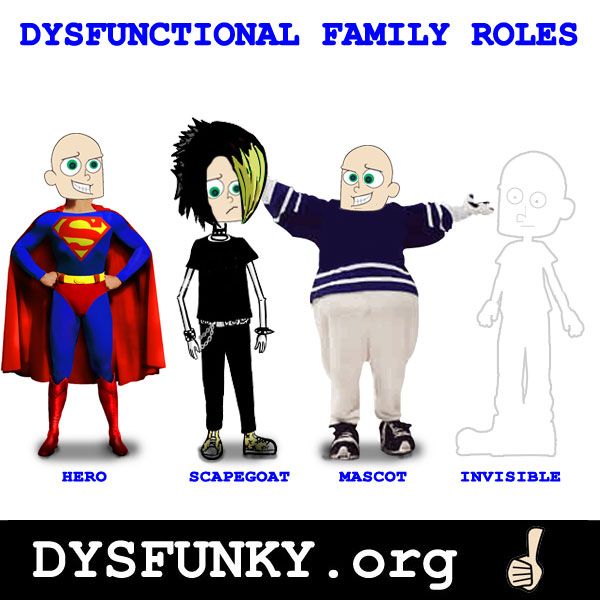

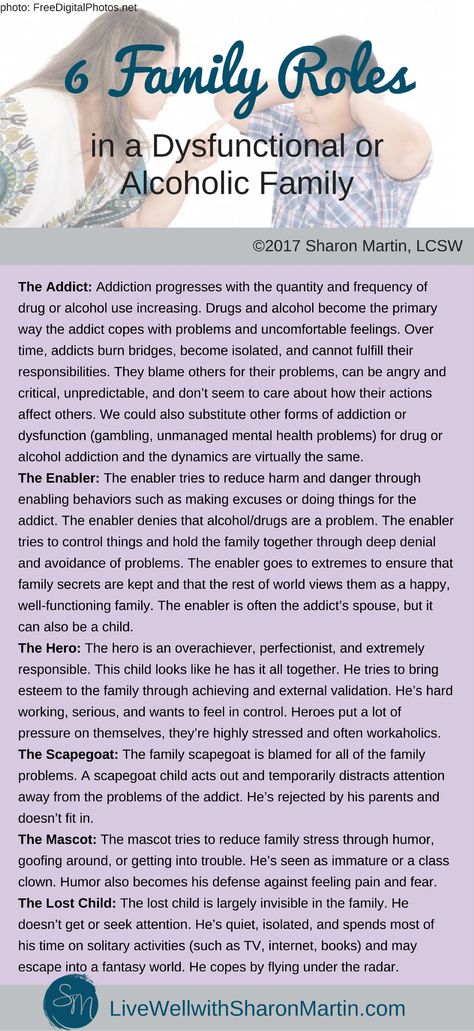

The good child (also known as the 'Hero'/'Peacekeepers' role)

A child who assumes the parental role or in advertent playing the role of the 'peacekeeper', to mediate and reduce tension between conflicting parents Their behavior may be reacting to their unconscious anxiety about family collapse [9,13].

The problem child or rebel (the 'Deviant' role)

A young person may be inadvertent playing a 'distracting family role' to attract attention and keep the family busy from their own relationship difficulties, thereby keeping the family altogether.

The 'Scapegoat' role

The child is seen as the black sheep who is blamed for most problems related to the family's dysfunction, while other children are seen as good children. Sometimes they may label the young child as 'mentally ill'; despite often being the only emotionally stable one in the family (with adaptive function enabling them to handle appropriately in the toxic environment).

The lost child

The inconspicuous, quiet one, whose needs are usually ignored.

The mascot/charm child

Uses comedy to divert attention away from the increasingly dysfunctional family system.

The mastermind child

The opportunist who capitalizes on the other family members' faults to get whatever he or she wants (Table 1).

Table 1: Screening questionnaire for long term effect of living in a dysfunctional family [3]. View Table 1

While, children who survive usually have three qualities that make it possible to mature properly or to survive the disadvantages of a dysfunctional family [10].

Either, children have a worthy focused quality for themselves and could easily grow up internally and not to meet everyone else's needs or children have a well-intentioned, unlimited energy with the plan to work hardly. And lastly, children might have an adaptable maturation process that requires constant adjusting and change.

Management of dysfunctional family need to be appropriate to cultural/religious and social background with respect to local raising attitude and behavior

Primary care assistance

Should be well trained, certified primary care physician with vast experience in solving family problems [3,9,14].

1. PCPs should use "Family Systems Theory" instead of "linear manner" which aims to strengthen both the individual and the family by passing into Therapeutic Alliance Management. PCPs using ''Family-Based Approaches" through facilitating change and growth for each family member (building self-confidence, optimizing motivation and a sense of empowerment).

2. Using warmth with clear, firm boundaries "Strengths-Based Approach" is helpful to all family members via improving their strengths in coping capacities.

3. PCPs need to "Reframing Family Feelings" and "Set Healthy Boundaries" try to not allow you to get sucked back in and supply family with love and wish them the best from a distance.

4. PCPs need to "Change Family's Attitude" towards a young person that has a negative influence on their self-identity/self-worth.

5. PCPs need to avoid "Reinforcing Patterns" in the family, which inadvertently serve to reinforce or encourage problematic behaviors that may unintentionally encourage preventing them from experiencing and learning from the consequences of their actions.

Specialist care service

Should be cultural/religious oriented with broad expertise in family therapy and counseling to prevent future family conflict.

1. "Get Proper Help" alignments from closer connections/hierarchies (positions of power) or from individual/family group counseling services.

2. "Seek Guidance" from specialist counselor, a life coach, yoga teacher; anyone who will listen, someone you feel comfortable with.

Individual care support

Should be appropriate to traditional patient circumstance.

1. "Learn Protective Ways" by practicing meditation and being patient with yourself and others.

2. Become "Self-Aware of Your Reaction" to break negative patterns as much as you can.

3. "Limit Your Time" spent with the toxic family/family member. Limit visits, holidays, do what you can to prevent as much conflict as possible.

4. "Accept your Parents or Family Member’s Limitation" and don’t have to repeat their behavior.

5. Learn to "Identify and Express Emotions" by accepting your own feelings/experiences and avoiding exaggerated consideration to others' feelings.

6. "Try to Vent your Anger" in productive ways (exercise, sports, use art and creative expression) and not destructive ways; don’t withhold your emotions.

7. Avoid "Chronic Guilty, Shame Feeling" that led to low self-esteem for their parents' mistakes.

8. Begin "Individual Long Learning Practice" to know whom do you trust and how much to trust by avoiding in an all-or-nothing manner and avoid seeking approval/acceptance from their others. Practice saying how you feel and asking for what you need.

9. Practice "Taking Good Care" of yourself by exercising, maintaining a healthy diet and trying to identify enjoyable things to be done.

10. Begin to have "Good Family Relationship" by focusing on yourself and your behavior and reactions.

11. "Take Charge of Your Life/Happiness" and don’t wait for others to give it to you.

12. At the end "Move Out" if meet patient cultural/religious customs and tradition (with friend, an extended family member) to a nurturing environment.

13. ''Read Helpful Books'' that provided strategies for recovering from dysfunctional family effects such as:

i. Toxic parents: Overcoming their hurtful legacy and reclaiming your life. New York: Bantam Books [8].

ii. Guide to recovery: A book for adult children of alcoholics. Holmes Beach, FL: Learning Publications [15].

iii. Codependent no more: How to stop controlling others and start caring for yourself. New York: Harper and Row [16].

iv. Outgrowing the pain: A book for and about adults abused as children. San Francisco: Launch Press [17].

San Francisco: Launch Press [17].

v. The courage to heal: A guide for women survivors of child sexual abuse. New York: Harper & Row [18].

vi. If You Had Controlling Parents: How to Make Peace with Your Past and Take Your Place in the World. DIANE Publishing Company [19].

vii. Praise, encouragement and rewards. Raising Children Network [20].

1. Exploring family dynamics with a young person helps PCPs to understand family behavior and difficulties in context.

2. PCPs need to explore individual distort characteristics such as invaluable, vulnerable, imperfect, dependent, and immature behaviors.

3. Where possible, use a "Strengths-Based Approach" when PCPs are exploring family dynamics, and identify family strengths, similarly, identify patterns that are problematic and may need to be challenged.

4- Listen to both sides of the coin (young person's perspective and the family's story) about their family dynamics, besides PCPs should be attentive to the family relationship patterns and interpretations.

None

None

None

- http://www.mudrashram.com/dysfunctionalfamily2.html.

- Vannicelli M (1989) Group psychotherapy with adult children of alcoholics: treatment techniques and countertransference. Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- http://www.k-state.edu/counseling/topics/relationships/dysfunc.html.

- Becvar D, Becvar R (2002) Family Therapy: A Systemic Integration. Pearson Education, Australia.

- Minuchin S (1974) Families and Family Therapy. Tavistock Publications, London.

- Minuchin S (1974) Families and Family Therapy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- http://www.understanding-child-abuse.com/dysfunctional-family.html.

- Forward S (1989) Toxic parents: Overcoming their hurtful legacy and reclaiming your life. Bantam Books, New York, USA.

- http://www.

strongbonds.jss.org.au/workers/families/familydynamics.pdf.

strongbonds.jss.org.au/workers/families/familydynamics.pdf. - http://www.dtl.org/cults/article/dysfunctional.htm.

- http://keepyourchildsafe.org.

- http://serenityseekers.org/meetings/symptoms-of-family-dysfunction.

- Dwight Lee Wolter c (1995) Forgiving Our Parents: For Adult Children from Dysfunctional Families.

- http://www.elephantjournal.com/2012/05/12-ways-to-deal-with-a-toxic-familyfamily-member.

- Gravitz HL, Bowden JL (1987) Guide to recovery: A book for adult children of alcoholics. Holmes Beach, FL: Learning Publications.

- Beattie M (1987) Codependent no more: How to stop controlling others and start caring for yourself. New York: Harper and Row.

- Gil E (1983) Outgrowing the pain: A book for and about adults abused as children. San Francisco: Launch Press.

- Bass E, Davis L (1988) The courage to heal: A guide for women survivors of child sexual abuse.

New York: Harper & Row.

New York: Harper & Row. - Dan Neuharth (1999) If You Had Controlling Parents: How to Make Peace with Your Past and Take Your Place in the World. DIANE Publishing Company.

- (2011) Praise, encouragement and rewards. Raising Children Network.

The impact of a dysfunctional family on the development and upbringing of a child

The article discusses the problems of parenting and its impact on the psychological state of the child. The factors influencing the troubles of families are identified and described.

Key words: family, alcoholism, upbringing, dysfunctional family, psychological characteristics, parent-child problems, prosperous family, family system.

The family is the first and most important social institution in a child's life. We are used to hearing that the family is where it is warm, where mutual understanding and mutual respect reign. The place where you want to come and return. However, if you look closely, it turns out that this is not entirely true. There are no perfect families. This is a pink veil that people came up with to advertise delicious yogurt, where everyone in the family always smiles and eats healthy food for breakfast.

The place where you want to come and return. However, if you look closely, it turns out that this is not entirely true. There are no perfect families. This is a pink veil that people came up with to advertise delicious yogurt, where everyone in the family always smiles and eats healthy food for breakfast.

The family is more like a drama theater with its beginning, climax and denouement. Not all families have arguments, accusations and threats every day. Due to the deterioration of the socio-economic factor of the country and uncertainty about the next day, parents often put in the forefront not the upbringing of their child, but the increase in the material condition of their family, which adversely affects the formation of the child's personality.

Also, due to the increase in the number of divorces, more than one fourth of the children are left without the care of one of their parents. Parental termination lawsuits are on the rise, and parents who are a negative influence on their children are being reported to the police.

Children fall into the “risk group” category, i.e. children from a dysfunctional family. What happens to a child if he ends up in a dysfunctional family. And what is a dysfunctional family and how does it affect the development of the child and his future? There is no single answer. After all, everything in our world is relative.

Everyone considers well-being and trouble from their own point of view. And children are all different, some are more enduring, while others are very vulnerable, and every raised voice from adults is perceived painfully for them.

If we talk about a child from a dysfunctional family, this does not mean that we are equal to an antisocial or asocial family. We are surrounded by many families that are dysfunctional, but at first glance it is impossible to say so about them. Naturally, a family in which parents abuse alcohol or have signs of violence against a child falls into the category of “risk group”. However, trouble can arise only in relation to a particular child. So only the system of relations between parents and the child can be considered as well-being or disadvantage.

So only the system of relations between parents and the child can be considered as well-being or disadvantage.

There are incomplete and complete families. On the one hand, the question immediately arises why a complete family can be dysfunctional. In a complete family, there may be a conflicting upbringing or upbringing where the child is suppressed. Sometimes an incomplete one is more useful for a child than an inferior one (the father drinks and terrorizes his family every day, one day he decides to leave, and the family lives in peace and harmony in the future).

However, families are not always dysfunctional if parents drink. There are also families that at first glance look like a prosperous family, but inwardly parents forget about raising children, and direct all their attention to material values. Such children lack attention and care from their parents. Such behavior on the part of the mother is especially bad for a child from an early age.

The lack of education is the most important indicator of a dysfunctional family. The household factor and prestigious things are not an indicator of family well-being or trouble, only the attitude towards the child.

The household factor and prestigious things are not an indicator of family well-being or trouble, only the attitude towards the child.

Trouble in the family leads to a violation of the child's mental development. This does not mean that the child will become stupid or there will be other intellectual impairments, but disharmony will occur in the formation of the emotional sphere, that is, it will affect the future character. In the future, it affects the relationship of a person with other people.

The most important factor that destroys not only the family, but also the mental balance of the child himself, is the drunkenness of one of the parents or both. This factor can have an adverse effect not only at the time of upbringing and growing up of the child, but also during the conception of the fetus.

The psychological characteristics of children who have drunkenness in the family looks like this. The child hides information about the parents, because he knows that people condemn such behavior and blame such parents for not doing their job. The habit of hiding, deceiving, evading the answer and not finishing it remains with the child for life. In the future, the child becomes suspicious and vicious. In the future, it is difficult for a child to openly communicate with others. Such children are more prone to jealousy, distrust and envy. The more secrecy there was in the family, the more it prompted confusion and loneliness in the child.

The habit of hiding, deceiving, evading the answer and not finishing it remains with the child for life. In the future, the child becomes suspicious and vicious. In the future, it is difficult for a child to openly communicate with others. Such children are more prone to jealousy, distrust and envy. The more secrecy there was in the family, the more it prompted confusion and loneliness in the child.

In such families, parents often do not fulfill their promises. It depresses the child. Since everyone keeps everything a secret, it provokes not to share their emotional experiences with parents. And as an adult, they continue to repeat their habits of not trusting anyone, problems appear in intimate relationships.

Often children have to become adults, despite the fact that they themselves are still children. They feel deprived of care and attention from their parents. They have to play the role of "parent" for their own. Listen, approve and make their lives more comfortable.

In the future, they get the feeling that they missed something and they didn’t get something that they deserved. Throughout their lives, they continue to struggle to regain that share of attention that they were deprived of in childhood. Often such people do not know how to enjoy life.

In an alcoholic family, a child often hears that dad should work and bring money into the house. So the child can begin to confuse money with love and attention. And when friends need help or attention, such children can get rid of them with gifts.

The emotional needs of children in alcoholic families are also not given due attention. And kids don't understand how to empathize with other people. They do not know the elementary duties of parents, which in the future has a negative impact on their own family.

If the child is a “girl” in such a family, and the mother suffers from alcohol, then the child increasingly has to replace her role in household chores, in caring for the younger ones, and one day it may happen that she replaces the role of wife in the eyes of her father .

Children from dysfunctional families became independent very early and they need help. The main task is to form in them the right idea about life. But this problem must be approached differently, according to age. Until adolescence, it is still possible to influence the mind of a child, but for older ones it is almost impossible.

But, once in a prosperous social circle, they need to follow the rules of this group, and often "inveterate scammers" gradually forget their "habits".

Such children need help in choosing a profession, housing and arranging their future life. And if they are left alone, then certainly a difficult future awaits them. Too much is lost in childhood, and it is doubly difficult for them.

Literature:

- Efremova OI, Kobysheva LI Pedagogical psychology. - M.-Berlin: Direct-Media, 2017. - 171 p.

- Efremova OI, Kobysheva LI Development Psychology. - M.-Berlin: Direct-Media, 2018. - 193 p.

- Kobysheva L. I. Psychological and pedagogical features of psycho-correctional work with children and adolescents [Electronic resource] // Internet journal "World of Science" 2016, Volume 4, Number 4 http://mir-nauki.com/PDF/43PSMN416.pdf . Access date: 05/20/2018.

- Project activity in library format: how to write grant applications correctly: method. recommendations [Electronic resource] / Novosib. state region scientific b-ka; comp. I. M. Khvostenko; resp. for the issue of S. A. Tarasov. - Novosibirsk: Publishing House of NGONB, 2016. - 62 p. — Access mode: http://www.ngonb.ru/activities/librarianship/izdaniya-i-publikatsii-nauchno-metodicheskogo-otdela/2014/

- Skudnova T. D., Kobysheva L. I., Shalova S. Yu. Psychological and pedagogical anthropology: a textbook for universities. - Moscow; Berlin: Direct-Media, 2018. - 356 p.

- Buyanov M. I. "A child from a dysfunctional family: notes of a child psychologist." - Moscow: Education, 2018.

- 167 p.

- 167 p. - Belicheva S. A. "Fundamentals of preventive psychology" - M.: Social health of Russia, 2017.-224 p.

- Bim-Bad B. M. "The nature of the child in the mirror of autobiography" - M .: URAO, 2017.-431 p.

- Korolenko Ts. P., Donskikh T. A. "Seven ways to disaster" - Novosibirsk, 2019. - 97 p.

- Eidemiller E. G., Yustitsky V. V. "Psychology and psychotherapy of the family." -SPb., 2018. - 652 p.

Basic terms (automatically generated) : family, dysfunctional family, child, parent, successful family, future, attention, complete family, parents' side.

Missing girl and drinking parents. How do children live in dysfunctional families | Article

First family. Where is the girl?

I went on a raid with a check of families registered with the police with the senior inspector for juvenile affairs of the 9th police department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia for Irkutsk Evgenia Tykmanova . The girl has been working in the PDN since December last year, before that she was an inspector for administrative supervision of former repeat offenders, among whom were murderers and rapists. When asked why she changed the department, she answers briefly: “I always wanted to be useful through my work, that’s why I went to PDN - children can still be helped.”

The girl has been working in the PDN since December last year, before that she was an inspector for administrative supervision of former repeat offenders, among whom were murderers and rapists. When asked why she changed the department, she answers briefly: “I always wanted to be useful through my work, that’s why I went to PDN - children can still be helped.”

Evgeniya Tykmanova, Senior Inspector for Juvenile Affairs of the 9th Police Department in Irkutsk

More often, inspectors go with checks after six in the evening to make sure to find parents at home, or immediately, as soon as a message is received about a violation of the rights of the child - and today as once such a case. A woman who lives in Bolshoy Luga called the police and said that her daughter Ekaterina and her partner often drink, do not work, and she is very worried about her seven-year-old granddaughter - the girl is left to her own devices. It turned out that in 2018, the daughter and granddaughter moved to their grandmother in the village, but two years later they returned to Irkutsk, since then the family has been registered with the PDN.

We call the intercom, no one answers. We are recruiting an apartment of neighbors - we go in. We knock on the door. Silence. We knock again. Behind the door we hear a rustle, then silence again. Evgenia knocks on the neighbors, the door is opened by a sleepy man. When asked if his neighbors are at home, he replies:

— I've been sleeping since the shift, I don't know.

— Drinking?

“It happens,” he replies, bewildered.

Noisy?

- Yes, often.

The inspector could not get through to Ekaterina. Then Evgenia dialed the number of her grandmother from Bolshoy Lug. The woman said that in the morning she talked with her daughter on the phone, she told her that she took her daughter to the kindergarten and went to get a job. And the inspector and I go to the kindergarten to make sure that the girl is all right.

In the kindergarten we were met by the principal. The woman checked the lists of pupils - there was no such girl in any of the groups of the institution. However, the head of the child's surname seemed familiar, and she decided to open the archives. It turned out that the girl really attended this kindergarten until 2018, then her mother transferred the child to a preschool in Bolshoy Luga, but, returning to the city, did not arrange the girl in the kindergarten.

However, the head of the child's surname seemed familiar, and she decided to open the archives. It turned out that the girl really attended this kindergarten until 2018, then her mother transferred the child to a preschool in Bolshoy Luga, but, returning to the city, did not arrange the girl in the kindergarten.

Now the inspector will have special control over this family: Evgenia will have to find out where the girl is, how she spends her time and whether she is in danger.

By the way, most messages come from watchful grandparents. They leave applications at the duty station or, if the family is already registered, they call the inspector directly. Evgenia recalls a case: a woman recently called her and complained about her drinking daughter, who constantly leaves her son to her. However, she refused to write an application for her daughter, fearing that she would be deprived of parental rights, and asked the inspector to talk to her daughter - in the hope that she would come to her senses. Evgenia managed to contact the girl only through her roommate. The inspector explained to the negligent mother that if she did not return home and take care of raising her son, the child would be taken away from her. And it helped: she returned home and even got coded.

Evgenia managed to contact the girl only through her roommate. The inspector explained to the negligent mother that if she did not return home and take care of raising her son, the child would be taken away from her. And it helped: she returned home and even got coded.

Parents react differently to the arrival of inspectors: some calmly, others aggressively. As a rule, they believe that they live well, the children are in normal conditions and they do not need help.

But there are times when the guardian has to deprive the mother of her parental rights. Evgenia spoke about a girl who gave birth to a son early. She didn’t have a mother, and she didn’t want to live with her father, so she wandered around friends with a baby in her arms. She could not get a job and went into prostitution. Once, leaving the child with her friend, she left to “work”. The guy sat with the baby for three days, and then left him in the apartment and left. A day later, the owner of the rented apartment found the child - dehydrated, in diaper rash - and called the police. The young man was found, he said that when the diapers ran out, he stopped drinking the child so that he would not go to the toilet, and when the food ran out, he packed his things and left on his own. The mother did not want to take the child from the hospital, and after a while she was deprived of parental rights.

The young man was found, he said that when the diapers ran out, he stopped drinking the child so that he would not go to the toilet, and when the food ran out, he packed his things and left on his own. The mother did not want to take the child from the hospital, and after a while she was deprived of parental rights.

Second family. Dirt and three children

We are going to the second address. The family, which is registered with the police, lives on Deputatskaya Street in a wooden two-story house. As Evgenia said, this is a family with three children: girls are 4 years old and 14 years old, the boy is nine months old. The family was registered, as parents drink, and often the children were left to their own devices.

The entrance door is closed, there is no intercom. Evgenia knocked on the window of the ground floor apartment, and a couple of minutes later we were let in by an elderly woman who lives next door to a dysfunctional family.

- Do your neighbors drink? the inspector asks the pensioner.

— No, they've been quiet lately. So now she lives alone with the children, so it has become calmer, ”she answers.

Evgenia knocks on the door. We were opened by the owner of the apartment. Seeing the inspector, the woman was not surprised, but calmly invited us to go inside. A girl with tangled dark hair and a dress that was several sizes too big ran out to meet her.

— Hello! she shouted joyfully in a ringing voice.

The apartment is dirty, smells like cigarettes and cat urine. The repair was done a long time ago: in some places there is linoleum on the floor in the corridor, in some places there is laminate, the paint on the walls and floor in the rooms has peeled off, lime is falling off the ceiling. At the entrance, children's clothes are on the bench, jackets are hanging on carnations nearby. We go into the room, which is illuminated only by a working TV. There is a table, a workplace for an older girl, a sofa with crumpled linens and a crib on which, standing on tiptoe, a thin boy stands and looks at us with curiosity.

– My son was born at the age of seven months, he has a developmental delay – that's what the doctors say, – the mother immediately explained.

– And what do you feed the little one?

- Porridges and mixtures. Everything is there,” the woman says.

An average girl is spinning next to me - she is cheerful and cheerful, but she speaks badly, mainly explains by gestures.

– Why doesn't she talk? I'm interested.

- She was also born prematurely, the doctors say she will speak soon, she should speak from the age of five. They gave me a referral to a defectologist, we'll go in July, - the woman calmly explains.

We go into the kitchen. The eldest daughter came out of a small room, seeing the inspector, immediately began to remove the dirty dishes from the table.

“Show me the mixtures,” Evgenia asked. The girl took out a baby bottle and a jar, which turned out to be empty. Confused, she looked from the inspector to her mother and back. The woman assured that her son was not hungry, the mixture was just over, and today she goes to the store to get it.

The woman assured that her son was not hungry, the mixture was just over, and today she goes to the store to get it.

– Who smokes? Evgenia asks.

Silence.

- Don't drink? And the daughter? Girlfriends with moonshine don't come anymore?

Silence.

It turned out that recently the husband left the family, the woman was left alone with the children. They live only on benefits, since the man does not pay alimony.

The inspector examined the children, checking whether they had toys according to their age, clothes according to the season and food in the refrigerator. And it's time for us to go to another family. Promising that she would not drink anymore, the woman closed the door behind us. I would like to believe that the mother will fulfill her promise, then, perhaps, the children will not repeat the fate of their parents.

As Evgenia explained to me later, if parents drink, they have a preventive conversation with them; if this does not help and it becomes obvious that children are in danger, they are removed from the family and placed in a special rehabilitation center, and babies, children under three years old , - to the Ivano-Matreninsky hospital. They continue to work with parents and give them the opportunity to improve. If they do not take any measures to return the children, guardianship is involved, and they may be deprived of parental rights.

They continue to work with parents and give them the opportunity to improve. If they do not take any measures to return the children, guardianship is involved, and they may be deprived of parental rights.

- It happens that drinking parents pull themselves together, but not often. More often, unfortunately, they are eventually deprived of parental rights, since sooner or later many of them start drinking alcohol anyway, says Evgenia.

Parents' drunkenness and upbringing through beatings often lead to tragic consequences.

But alcohol does not always cause problems with children in the family: sometimes parents' indifference to their fate leads to the fact that they end up in shelters. There was a case when a woman turned to the police with a statement that her ten-year-old daughter had run away from her when they were in a store together. The girl was searched with dogs all over the city and was found a day later in one of the hostels. When she saw the police, she huddled in a corner in fear. Having calmed down, the child said that she could not be at home: her mother did not give a damn about her, she did not pay attention to her daughter, so she would be better off in an orphanage - and the girl was placed in a children's center.

Having calmed down, the child said that she could not be at home: her mother did not give a damn about her, she did not pay attention to her daughter, so she would be better off in an orphanage - and the girl was placed in a children's center.

— During preventive conversations with children at schools, I always tell them: if there is a conflict with parents, you need to turn to the school for help, and not run away, because sometimes it ends badly for the children, says Evgenia.

Third family. Bad company

Then we go to Dybowski. A woman lives in a one-room apartment, who alone brings up three children. The family was registered because of the periodic drunkenness of the mother, and also because of the middle son, who contacted a bad company and began to steal. They live on allowances and alimony, which are paid only from time to time by the father of the children.

According to the inspector, the 10-year-old boy is good, he studies well, but, having moved to the area, he contacted a local gang of juvenile hooligans, who are registered with the PDN. All the guys with whom he began to communicate are from dysfunctional families - their names are well known to the police. Their parents force their children to steal in order to sell stolen things later - they live on the proceeds.

All the guys with whom he began to communicate are from dysfunctional families - their names are well known to the police. Their parents force their children to steal in order to sell stolen things later - they live on the proceeds.

— If he is removed from this bad company, then everything will be fine with him, Evgenia suggests.

No one answered the call to the intercom. One of the residents of the house let us into the entrance. We rise to the fifth floor and ring the doorbell. Just a few seconds later, a woman opened the door for us. Seeing the inspector, she hurried to invite us to the apartment, warning that two children were sleeping.

There are children's shoes in a row in the hallway, scooters and sandbox toys nearby. Children's clothes are lined up in the closet. “These are girls, and these are the things of the elder,” the woman explains.

- Did you return the bike? the inspector asks, recalling a recent incident in which a boy stole a bicycle from a playground.

— Yes, he gave it to the boy himself. I don’t know why he took someone else’s bike, I offered him to buy his own, but he doesn’t want to, the woman explains.

The apartment is small: a hall combined with a kitchen, a small room and a bathroom. There is not much furniture, but everything you need is there: two children's beds, a sofa, a desk. From equipment - TV, kettle, microwave and refrigerator. The woman hurried to show that the food is there - the children do not go hungry.

The apartment is smoky. Even the hastily opened balcony did not help to ventilate the room. But the woman is sober, the children are fine, the rooms are clean, and here the inspector has nothing more to do for now.

When children engage in petty theft, they are registered with the police. However, if they commit particularly serious crimes, such as murder, the PDN inspectors go to court and the child ends up in a temporary detention center for minors. “But in my practice this has not happened,” adds the inspector.

But there were two cases that Yevgenia remembers most of all for their cruelty: when one boy severely beat a classmate, breaking his jaw, and the other first mocked his peer, then beat him with a wire, then cut him with a knife. All crimes committed by children, the inspector notes, are especially cruel, as teenagers do not realize that their actions can lead to serious consequences, including for themselves.

A teenager can be registered not only for crimes (fights with peers and petty theft), but also for not attending school, drinking alcohol or drugs.

According to Yevgenia, sometimes the reason for the aggressive behavior of children (for example, they run away from home and, as a result, fall under police surveillance) lies in the family. Recently, she recalls, a woman called the emergency department asking for help with her 12-year-old son, who behaves aggressively, does not obey her and refuses to do his homework. Arriving at the call, Evgenia talked to the teenager and found out that he has problems with classmates who bully him, and he would like to go to another school. Evgenia tried to explain this to his mother, but she did not want to listen. The woman was sure that her son was doing well, the school was excellent, and she did not intend to transfer him to another institution. Only after a long conversation with the parents was it possible to come to a compromise: this academic year the child completes his studies as is, then he moves to another class or even changes schools.

Evgenia tried to explain this to his mother, but she did not want to listen. The woman was sure that her son was doing well, the school was excellent, and she did not intend to transfer him to another institution. Only after a long conversation with the parents was it possible to come to a compromise: this academic year the child completes his studies as is, then he moves to another class or even changes schools.

— Often parents do not listen and do not hear their children. They are sure that they know better what to do, and all the problems that children have are not serious, you don’t need to pay attention to them. But the conflict in the family and misunderstanding between parents and children sometimes lead to children's suicides. And our main task is to prevent such cases,” says Evgenia.

***

Often, dysfunctional families have not one or two children, but five or more children. Many of the negligent parents consider children as bread cards: the more there are, the higher the allowance and the more substantial assistance from the state.