Anxious when bored

What happens in the brain when we are bored?

By Maria Cohut, Ph.D. on July 9, 2019 — Fact checked by Paula Field

In people who are prone to boredom, this state can negatively affect their mental health. So, what happens in the brain when we get bored, and how can this help us find ways of dealing with boredom? A new study investigates.

Share on PinterestWhat happens in the brains of people who are prone to boredom? New research finds out.On average, adults in the United States experience 131 days of boredom per year — at least that is what a recent commercial survey suggests.

What matters, though, is not just how much time a person spends feeling bored, but also how they react to the state of boredom.

Traditionally, boredom gets a bad rap because many people believe that the state of boredom equates with a lack of productivity or focus on a given task.

However, some research has indicated that it is good to be bored because this state helps boost creativity.

One way or the other, boredom is something we all have experienced repeatedly throughout our lives, and according to some research, it seems that animals might share this experience with us, too.

“Everybody experiences boredom,” says Sammy Perone, who is an assistant professor at Washington State University in Pullman. However, he adds, “some people experience it a lot, which is unhealthy.”

For this reason, Perone and colleagues from Washington State University decided to conduct a study focusing on what boredom looks like in the brain.

The study findings — which now appear in the journal Psychophysiology — might help them identify the best ways of coping with boredom so that this state does not end up affecting mental health.

At the end of the day, “we wanted to look at how to deal with [boredom] effectively,” Perone explains.

To begin with, the research team believed there was a “hardwiring” difference in the brains of people who react negatively to boredom vs. those individuals who experience no ill effects when they are bored.

those individuals who experience no ill effects when they are bored.

However, initial tests — using electroencephalogram (EEG) caps to measure participants’ brain activity — proved them wrong.

“Previously, we thought people who react more negatively to boredom would have specific brain waves prior to being bored. But in our baseline tests, we couldn’t differentiate the brain waves. It was only when they were in a state of boredom that the difference surfaced,” Perone explains.

So, if there was no difference in terms of brain hardwiring, then what could explain why boredom affected some people more adversely than others? The researchers decided that the most likely explanation was individual response: some people simply reacted poorly to being bored, which could affect their well-being.

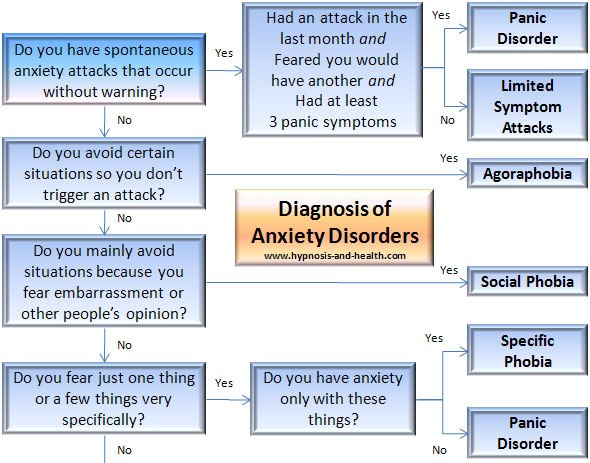

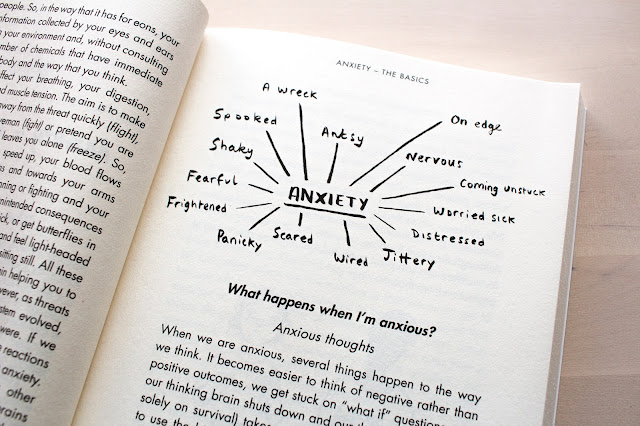

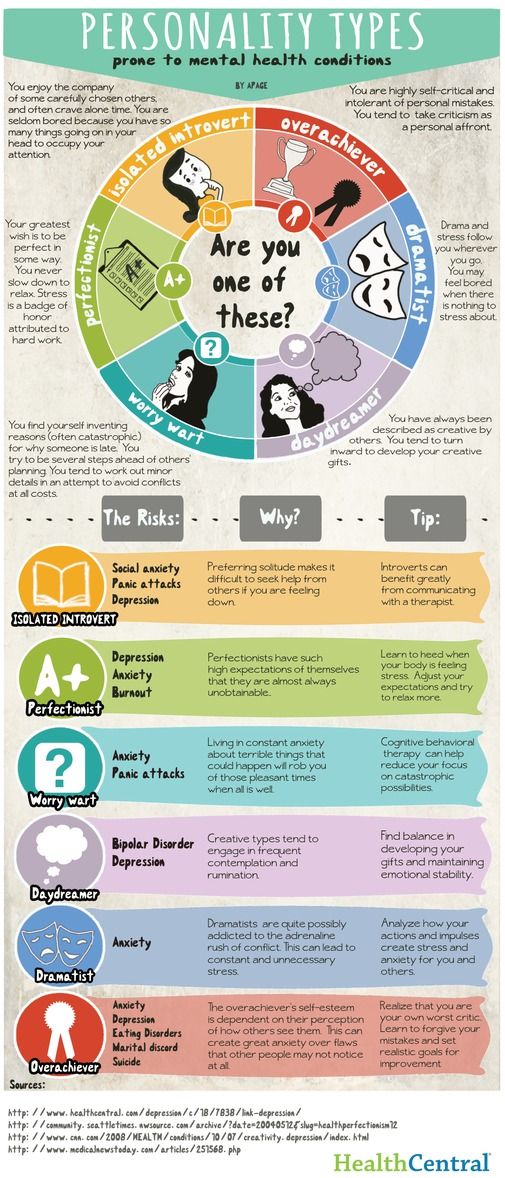

Previous research, the investigators report in their study paper, has actually suggested that individuals who are often bored are also more prone to poor mental health, and particularly to conditions such as anxiety and depression.

“People who report high levels of boredom propensity have an avoidant disposition. For example, these individuals are more likely to experience depression and anxiety,” the researchers write.

Based on these premises, the researchers argue that it is possible to find ways of coping with states of boredom so that they become less likely to affect mental health. But what might these strategies be? Before they could find out, Perone and team had to solve another mystery, namely what boredom looks like in the brain.

For their study, the researchers recruited 54 young adult participants. The researchers asked the volunteers to fill in a survey asking questions about boredom patterns and how they reacted to feeling bored.

Then, after a baseline EEG test measuring normal brain activity, the researchers assigned the participants a tedious task: they had to turn eight virtual pegs on a screen as the computer highlighted them. This activity lasted approximately 10 minutes, during which time the researchers used EEG caps to measure participants’ brain activity as they carried out the boring task.

“I’ve never done [this activity], it’s really tedious,” Perone admits. “But in researching previous experiments, this was rated as the most boring task tested. That’s what we needed,” he explains.

In assessing the brain wave “maps” obtained via the EEGs, the researchers looked specifically at activity levels in the right frontal and left frontal areas of the brain.

That was because these two regions become active for different reasons. The left frontal part, the researchers explain, becomes more active when an individual is looking for stimulation or distraction from a situation by thinking about something different.

Conversely, the right frontal part of the brain becomes more active when an individual experiences negative emotions or states of anxiety.

The researchers found that participants who had reported being more prone to boredom on a daily basis displayed more activity in the right frontal brain area during the repetitive task, as they became increasingly bored.

“We found that the people who are good at coping with boredom in everyday life, based on the surveys, shifted more toward the left. Those that don’t cope as well in everyday life shifted more right.”

Sammy Perone

The team’s next step is to identify clear strategies that will allow people to cope better with states of boredom. Clues have already emerged after asking participants in the current study how they dealt with the boring activity.

“We had one person in the experiment who reported mentally rehearsing Christmas songs for an upcoming concert. They did the peg turning exercise to the beat of the music in their head,” says Perone.

“Doing things that keep you engaged rather than focusing on how bored you are is really helpful,” he notes.

In other words, proactive thinking could be a good way of coping with boredom. The trick, however, is getting individuals to learn how to do more of this, and succumb to boredom less.

“The results of this paper show that reacting more positively to boredom is possible. Now we want to find out the best tools we can give people to cope positively with being bored,” explains Perone.

Now we want to find out the best tools we can give people to cope positively with being bored,” explains Perone.

“So,” in future studies, he adds, “we’ll still do the peg activity, but we’ll give [participants] something to think about while they’re doing it.”

“It’s really important to have a connection between the lab and the real world. If we can help people cope with boredom better, that can have a real, positive mental health impact,” the researcher contends.

The Surprising Link Between Anxiety and Boredom

Anxiety is probably the most common presenting issue among my client base. One of my clients stands out as having a particularly long history of it; she doesn't remember a time when anxiety wasn't a feature of her life. Over the years I've worked with her, she has gained a lot of understanding as to what lies behind her anxiety to the extent that it no longer derails her. Though still prone to anxiety in certain situations, like most of us, her baseline state is a lot calmer. In the initial stages of our work together, I would try to get her to imagine what life without anxiety might look like, how she might feel in its absence. She confessed that one of her fears was that once the anxiety faded away, boredom would loom large in the foreground. Over her decades-long acquaintance with anxiety, she knew and had become accustomed to it, but boredom inspired a real sense of dread in her.

In the initial stages of our work together, I would try to get her to imagine what life without anxiety might look like, how she might feel in its absence. She confessed that one of her fears was that once the anxiety faded away, boredom would loom large in the foreground. Over her decades-long acquaintance with anxiety, she knew and had become accustomed to it, but boredom inspired a real sense of dread in her.

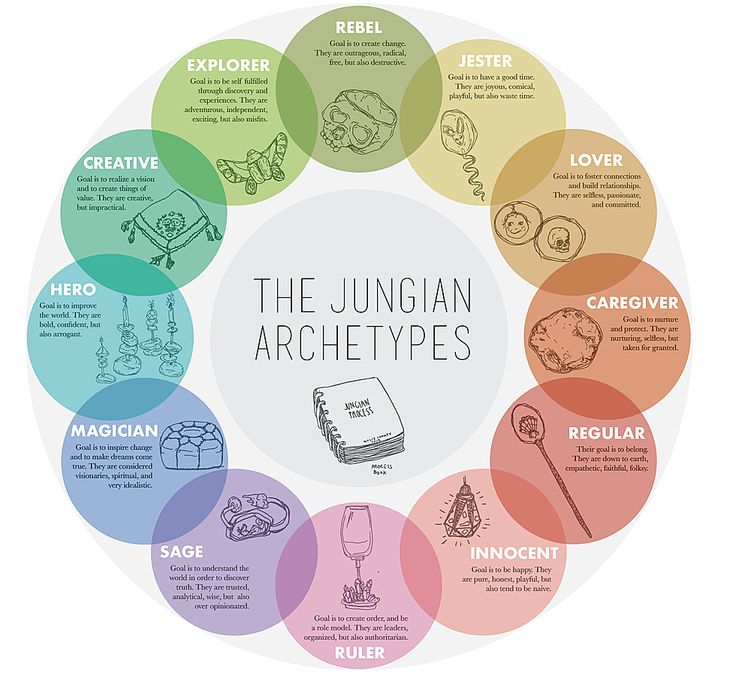

Sure enough, as her anxiety lessened, boredom did start to make its presence felt in her life. However, over time, my client came to embrace this new state. She labeled it "a privilege" and a sign that anxiety had released its stranglehold over her life. Interestingly, when she stopped reacting to and judging her boredom, it started to ease. Different things came to occupy the void previously occupied by her anxiety and fear. She started writing and engaging in creative pursuits again. For this client, boredom was the vacuum left by her anxiety. Perhaps her case is not that unusual. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer asserted that as humans we are "doomed to vacillate between the two extremities of distress and boredom."

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer asserted that as humans we are "doomed to vacillate between the two extremities of distress and boredom."

Boredom and anxiety are curious bedfellows. On the surface, they have little in common. The former suggests disengagement, a lack of arousal. Anxiety, on the other hand, is denoted by alertness, our antennae up and monitoring for potential threat or danger. But both are uncomfortable states for many of us.

My client's attitude toward boredom taught me a lot. It led me to reflect upon the taboo around boredom. Many of us will gladly profess to be busy and stressed as these states confer a sense of industriousness and purpose, suggest that we're important, we're needed! But boredom? Broadly speaking, it's not perceived as a particularly adult emotion. In spite of this, a recent Gallup poll found that 70 percent of Americans find their work boring. Considering that the average American spends an estimated 40 hours per week at work, that's a lot of bored Americans!

If we go with it rather than distract ourselves from it, we can learn a lot about being still and patient.

Much consumer marketing, advertising, and product development is designed to address boredom. Indeed, if we were more comfortable being bored or sufficiently creative to amuse ourselves without the aid of consumer goods, then our capitalist society would probably collapse. Some advertising explicitly pitches to bored consumers. In a recent search for a tablet computer, I read in one product blurb that with the purchase of said device one "need never be bored again."

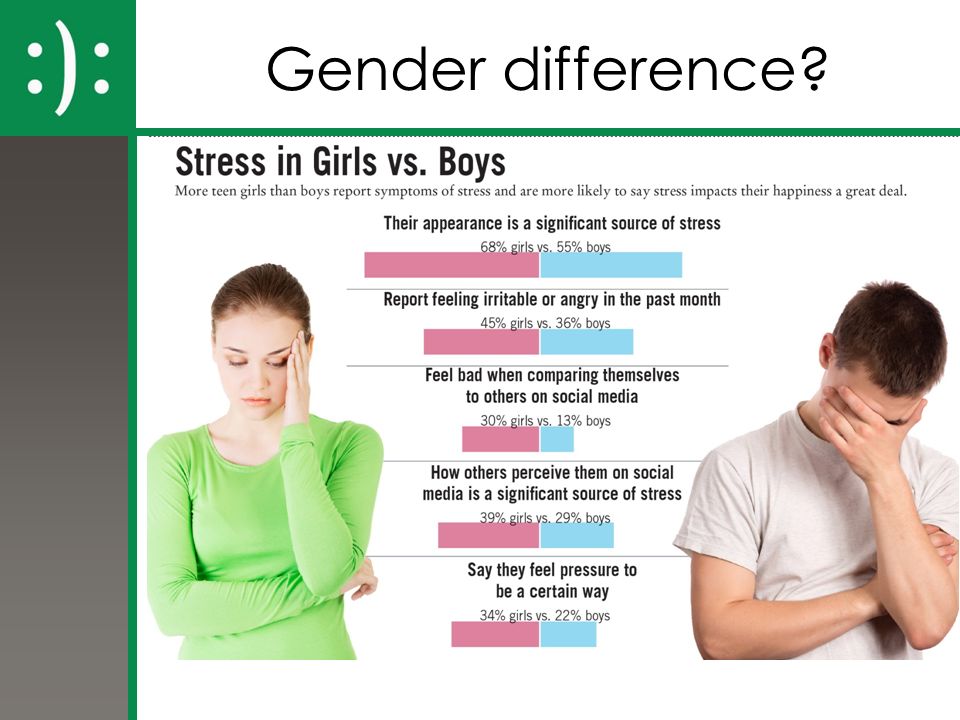

People will go to great lengths to escape boredom. Many of us would rather feel pain or discomfort than nothing at all. In 2014, Harvard psychologists found that faced with spending 15 minutes alone in a room with no stimulation (read: no smartphone!), two-thirds of men pressed a button in the knowledge that it would deliver a painful jolt. One man found being left alone in his own company so disagreeable he opted to be shocked 190 times. Under the same conditions, a quarter of women pressed the shock button. The scientists attributed the difference in self-shocking levels between the men and women to the fact that men tend to be more sensation-seeking. Timothy Wilson, who led the research, attributed the findings to humans' "constant urge to do something rather than nothing."

The scientists attributed the difference in self-shocking levels between the men and women to the fact that men tend to be more sensation-seeking. Timothy Wilson, who led the research, attributed the findings to humans' "constant urge to do something rather than nothing."

For many of us, boredom can feel like nothingness, a void where we're not feeling much, not doing much. As a child, probably the worst thing I could say to my mom was "I'm bored." I was looking for a solution to this dilemma, something to do, some entertainment. Maybe children no longer get bored, or if they do, perhaps they're pawned off with a parent's smartphone. As adults we've learned to digitally self-soothe, pulling out our smartphones for pretty much the same reason people might have lit up a cigarette a few decades ago: something to kill time with. Our smartphones are the ultimate one-stop boredom reliever. No wonder we cannot put them down. We may not admit to being bored, but why else can't we go 12 minutes without checking our devices? If being glued to one's smartphone can be taken as a gauge of boredom levels, it seems a lot of us are bored a lot of the time!

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

Boredom and addiction.

"The truth is, many people fall into drug and alcohol addiction because of boredom. It's something to do." I read this on the website of Raleigh House, a rehab center in Colorado, recently. I believe the same principle applies to our smartphone addictions. Being constantly on our phones keeps boredom at bay.

Several key features of our smartphones can be very magnetic to the bored mind. Take, for instance, messaging (including texting, WhatsApp, Telegram, etc.), which remains the most popular smartphone function. We expect replies more quickly than ever before. When email was introduced, traditional mail was dubbed "snail mail." Now email has been consigned to the same category. On our chat apps, we can see if the recipient has read our message and whether they're replying in real time or not. Natasha Dow Schüll, a cultural anthropologist who has researched gambling addiction, likens "the roller-coaster ride of texting" to playing slot machines. Quoted in a Financial Times article on modern dating, she compares leaving a message on an answering machine to buying a lottery ticket because you don't expect an immediate payoff. But texting taps into what Schüll dubs the "ludic loop" of the slot-machine experience. "The possibility of instant gratification coupled with reward uncertainty draws us into the game, and the absence of built-in stopping mechanisms makes us keep playing," she says. These ups and downs, highs and lows, are the antidote to boredom, a roller-coaster ride for our jaded, bored selves.

Quoted in a Financial Times article on modern dating, she compares leaving a message on an answering machine to buying a lottery ticket because you don't expect an immediate payoff. But texting taps into what Schüll dubs the "ludic loop" of the slot-machine experience. "The possibility of instant gratification coupled with reward uncertainty draws us into the game, and the absence of built-in stopping mechanisms makes us keep playing," she says. These ups and downs, highs and lows, are the antidote to boredom, a roller-coaster ride for our jaded, bored selves.

The human brain produces more dopamine when it anticipates a reward but doesn't know when it will arrive. Most of the alluring apps and websites in wide use today were engineered to exploit this habit-forming loop.

Boredom and meaninglessness.

In an article for the Atlantic based on her book Yawn: Adventures in Boredom, author Mary Mann says, "It's easier to label that itchy sensation 'boredom' than it is to consider the feeling one gets sometimes that the train of life is stopped on its tracks, that the narrative is going nowhere. " She adds, "Because boredom is such a motivating, annoying, irritating force, boredom can be kind of useful."

" She adds, "Because boredom is such a motivating, annoying, irritating force, boredom can be kind of useful."

Existential therapist, neurologist, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl wrote in Man's Search for Meaning, "Boredom is now causing more problems to solve than distress. And these problems are growing increasingly crucial, for progressive automation will probably lead to an enormous increase in the leisure hours available to the average worker. The pity of it is that many of these will not know what to do with all their newly acquired free time." Frankl wrote his book half a century before the invention of the smartphone and obviously hadn't reckoned on a portable device that would act as a gateway to every possible type of entertainment! Frankl asserted that in the postwar years, the mass of people living lives without meaning led to the rise of what he termed the "mass neurotic triad"—namely depression, aggression, and addiction.

Frankl was imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp for one and a half years. "Distressing" seems a gross understatement to describe what he lived through. But rather than focus on this traumatic experience, what he was drawn to amid the environment of loss and despair was the role finding a sense of meaning played in his survival. In the bleakness of Dachau he was able to find something of value within himself that he could connect with: namely, the love he felt for his wife. The acknowledgment of this love acted like a touchstone for Frankl and gave him the power and sense of purpose he needed to survive.

"Distressing" seems a gross understatement to describe what he lived through. But rather than focus on this traumatic experience, what he was drawn to amid the environment of loss and despair was the role finding a sense of meaning played in his survival. In the bleakness of Dachau he was able to find something of value within himself that he could connect with: namely, the love he felt for his wife. The acknowledgment of this love acted like a touchstone for Frankl and gave him the power and sense of purpose he needed to survive.

Frankl's belief was that no matter what life serves up, if one takes appropriate action and adopts the right attitude to the situation, a meaningful existence can be realized. His experience of transcending the conditions of Dachau would certainly attest to this. To extrapolate Frankl's philosophy, the antidote to boredom and boredom-induced addiction is to find a meaning, a sense of purpose to our lives. If we have that, we are insulated from the "What does it matter; why should I bother?" despondency that is the breeding ground for boredom and also addiction.

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

Enduring, persistent boredom, underpinned by a sense that one’s contribution doesn’t make a difference, can be a powerful catalyst for change when faced without judgment.

Many of us need to go through years of doing things that feel unimportant, unstimulating—in short, boring—until we can bear no more and are pushed to develop a sense of what we were put on this Earth to do. That was certainly my experience. For half a decade, I plodded along in a fog knowing that I wasn't fulfilled in my career. I was making just enough effort to keep my slate clean and my boss off my back. I felt stuck but lacked the energy required to make the jump to something else. I had an aptitude for what I was doing, which allowed me to coast, a particularly deadening state for me. I had my epiphany moment in the middle of a conference on some hard-core technology in Washington. The fact that I didn't understand what was being discussed was the least of my worries. I felt I was in the wrong place. I had no business being there.

The fact that I didn't understand what was being discussed was the least of my worries. I felt I was in the wrong place. I had no business being there.

This was 15 years ago, well before the iPhone hit Apple store shelves. If I had a smartphone then, I might not have had this moment of realization and failed to hear the internal voice screaming, "Get the hell out of this job, this career. Do something, do anything, but don't do this!" Instead, I would have been busy distracting myself, messaging my friends, perhaps even watching something on YouTube, putting off the inevitable point when I would finally have said, "Enough, no more."

Listen to your boredom—it might have something to tell you.

When I work with boredom, I take a similar approach as when addressing anxiety. Rather than reacting to it, trying to suppress it, distract from it, I encourage my clients to treat it with curiosity (curiosity being another natural antidote to boredom!). Being bored, feeling unstimulated is certainly part of the ebb and flow of life, and if we go with it rather than distract ourselves from it, we can learn a lot about being still and patient.

But there are times when prolonged enduring boredom can be a signal that we're not using our skills and talents, we're not channeling our creativity. In short, that we've stalled and have become stuck, like I was at the tech conference.

Like anxiety, this brand of enduring, persistent boredom underpinned by a sense that one's contribution doesn't make a difference can be a powerful catalyst for change when faced without judgment. Ask yourself, what is boredom trying to tell you? Mine was like a hacked, belligerent GPS shouting, "Stop! This is a dead end. Turn around and go back. Find another route!" Listening to that voice formed the first step in embarking on a career that I find very fulfilling. Had I not had that intense moment of boredom at the tech conference and felt my body, soul, and mind's strong reaction to it, I doubt I'd now be a qualified therapist writing this book.

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

Embrace the void.

If you're on a journey to cut back on your digital addictions, perhaps you've noticed your phone use dipping. Maybe you feel bored, and you don't know what to do with the free time you've created; welcome to "the void." This is a good place to be.

Adapted and excerpted from The Phone Addiction Workbook: How To Identify Smartphone Dependency, Stop Compulsive Behavior, and Develop a Healthy Relationship With Your Devices. Copyright © 2019 by Hilda Burke. Reprinted with permission of Ulysses Press. All rights reserved.

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

What's the point of living! .. Without adventures ... - Lermontov. Full text of the poem - What's the point of living! adventures

And with adventures - melancholy

Everywhere, like a restless genius,

Like a faithful wife, close;

It's great to be with a noisy crowd,

To sit behind a stone wall,

To recognize love and hate,

To chat about it once;

Involuntarily recognize everywhere

Under the proud gravity of the face

In a man a stupid flatterer

And in every woman Judas.

And take the trouble to consider -

It's more fun to die.

End! How sonorous this word is,

How many - few thoughts in it;

The last groan - and everything is ready,

Without further inquiries - and then?

Then they will sedately put you in a coffin,

And the worms will gnaw at your skeleton,

And there is an heir at a good hour

Will crush you with a monument.

He will forgive you every offense

Out of the goodness of his soul,

For your benefit (and the churches)

Serve, right, a memorial service,

Which (I'm afraid to say)

You are not destined to hear.

And if you died in the faith,

As a Christian, then granite

For forty years, at least

Your name will be preserved;

When the cemetery is already embarrassed,

That narrow dwelling of yours

Will be torn open by a bold hand...

And another coffin will be placed next to you.

And silently lie next to you

Tender girl, alone;

Mila, submissive, though pale;

But neither breath nor glance

Your peace will not be disturbed -

What bliss, my God!

1832

Long

Golden Age

Poems by Mikhail Lermontov-Long

Poems by Mikhail Lermontov-Golden Age

Other verses of this author

Borodino

-Slease, Uncle, because it is not without reason

Moscow burned by fire,

About the war

Death of a poet

Vengeance, my lord, vengeance!

I will fall at your feet:

Long

Motherland

I love my homeland, but with a strange love!

My mind will not defeat her.

About the motherland

Sail (A lonely sail turns white)

A lonely sail turns white

In the blue mist of the sea!

Azure steppe, pearl chain

About the homeland

to myself

How I wanted to assure myself,

What I do not like it, I wanted

Golden Age

how to read

Publication

How to read Dostoevsky

about a large -scale psychological study of the Russian classic

Publication

How to read Bulgakov's The White Guard

Literary tradition, Christian images and reflections on the end of the world

Publication

How to read "The Enchanted Wanderer" by Leskov

Why Ivan Flyagin turns out to be a righteous man, despite his far from sinless life

Publication

How to read poetry: the basics of versification for beginners poems to be without rhyme

Publication

How to read Shmelev's "Summer of the Lord"

Why religious images play an important role in a work about childhood

Publication

How to read "The Twelve" by Blok

What details you need to pay attention to in order not to miss the hidden meanings in the poem

Publication

How to read "Dark Alleys" by Bunin

What to look for in order to understand the famous story of Ivan Bunin

Publication

How to read Kuprin's "Garnet Bracelet"

What the modern reader needs to know in order to truly understand the tragedy of an official in love

Publication

How to read Pasternak's Doctor Zhivago

We talk about the key themes, images and conflicts of Pasternak's novel

Publication

How to read Nabokov

Homeland, chess, butterflies and color in his novels 9002 - Cultural Humanities 9002 educational project dedicated to the culture of Russia. We talk about interesting and significant events and people in the history of literature, architecture, music, cinema, theater, as well as folk traditions and monuments of our nature in the format of educational articles, notes, interviews, tests, news and in any modern Internet formats.

We talk about interesting and significant events and people in the history of literature, architecture, music, cinema, theater, as well as folk traditions and monuments of our nature in the format of educational articles, notes, interviews, tests, news and in any modern Internet formats.

- About the project

- Open data

© 2013–2022, Ministry of Culture of Russia. All rights reserved

Contacts

- E-mail: [email protected]

- Found a typo? Ctrl+Enter

Materials

When quoting and copying materials from the portal, an active hyperlink is required

Your child is bored, and that's great. Benefits of doing nothing for children

Image of Yassay from Pixabay

A modern parent knows well (and at the same time repeats to himself and his relatives like a mantra): “A child's abilities and skills must be developed from an early age.

” This knowledge soon turns into endless attempts to use children's time as efficiently as possible. As a result, children are rarely left alone with themselves. Using case studies as an example, we will understand why it is sometimes useful to put gadgets aside and let the child get bored a little.

” This knowledge soon turns into endless attempts to use children's time as efficiently as possible. As a result, children are rarely left alone with themselves. Using case studies as an example, we will understand why it is sometimes useful to put gadgets aside and let the child get bored a little. Boredom will help with lessons

So what benefit does a child get when they do nothing? Researchers Karen Gasper and Brianna Middlewood from Pennsylvania found that bored people cope with creative tasks better than those who are simply relaxed or, conversely, concentrated. A "bored" brain finds more unusual solutions even for simple tasks, processes information more efficiently - this is exactly what is useful during lessons, tests, creative music or drawing.

Although it seems to many that multitasking is something that a modern person cannot do without, it is not entirely true. In 2010, scientists at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research in Paris found that without sacrificing quality, we can only handle two tasks at a time. But even such activity leads to unpleasant consequences in the form of stress and fatigue.

But even such activity leads to unpleasant consequences in the form of stress and fatigue.

What is really important and necessary to be able to do is switch between different activities, immersing yourself and thoroughly delving into each separately. And for this it is important to leave space for rest and boredom.

Doing nothing helps you understand yourself

When a child does not have a gadget in his hands, before his eyes there is a colorful cartoon, and his head is not busy solving math examples, he finally starts to think about himself - does he really like ballet and specialized mathematics; why he is more interested in Venya than with Kolya; how can I persuade my mother to go to the new "adult" film in the cinema. Simply put, the child reflects when he has free time from worries. Left alone with their own thoughts, children also consider their relationship with their parents. In addition, as children's doctors say, at this time a sense of belonging to the family and home is formed.

A bored child learns to play by his own rules

To comprehend their relationship with mom, dad, relatives and friends, children come up with all kinds of role-playing games. At preschool age, this is the leading type of activity, through which the child begins to navigate in interpersonal relationships, understands the cause-and-effect relationships of various phenomena, and tries on various social roles.

It is boredom that prompts a child to experiment and invent new games, because gadgets and desktop entertainment already have clear rules that must be followed. And when you get bored, you have to come up with your own - just such a game, says the pediatrician Kenneth Ginzburg helps develop the most useful and important skills: memory, thinking, attention, emotional, practical and social intelligence.

It is through playing by their own rules that children learn to solve problems, and often in the face of uncertainty - an certainly useful skill that will come in handy at any age. He is responsible for the reaction of children to unfamiliar situations and the ability to split complex situations into small subtasks.

He is responsible for the reaction of children to unfamiliar situations and the ability to split complex situations into small subtasks.

Parents at this time have the opportunity to get acquainted with the children's world and strengthen relationships by joining the game. The most important thing is to follow the rules already established by the child. Remember that an adult here is just a guest and an attentive observer.

Children's games help prevent anxiety and depression

“The amount of time that children play freely is reduced due to pervasive parental control,” writes pediatrician Esten Entin in her study on childhood mental illness. Through the game, the child learns to follow the rules, control their emotions and recognize others. Including anger and fear, resistance to which reduces the risk of a number of anxiety disorders.

If children play a lot for their own pleasure and by their own rules, they are much less prone to depression.

At an early age, social play is one of the most important elements of development for children, therefore, in kindergarten and elementary school, it is the children who are well acquainted with free play and playing by the rules that make better friends and have less conflict with their peers. And children who play more often are happier - their brain produces more endorphins. The opportunity to play freely is a major investment in a child's emotional and mental health, Esther concludes.

Boredom trains parental patience

All previous advice will seem useless to parents who have ever found themselves in a situation where a child left without a tablet complains that he has nothing to do. He becomes restless and irritable because he is used to mobile games and endless circles. So, it will take time for him to get used to the long-forgotten feeling of boredom again.

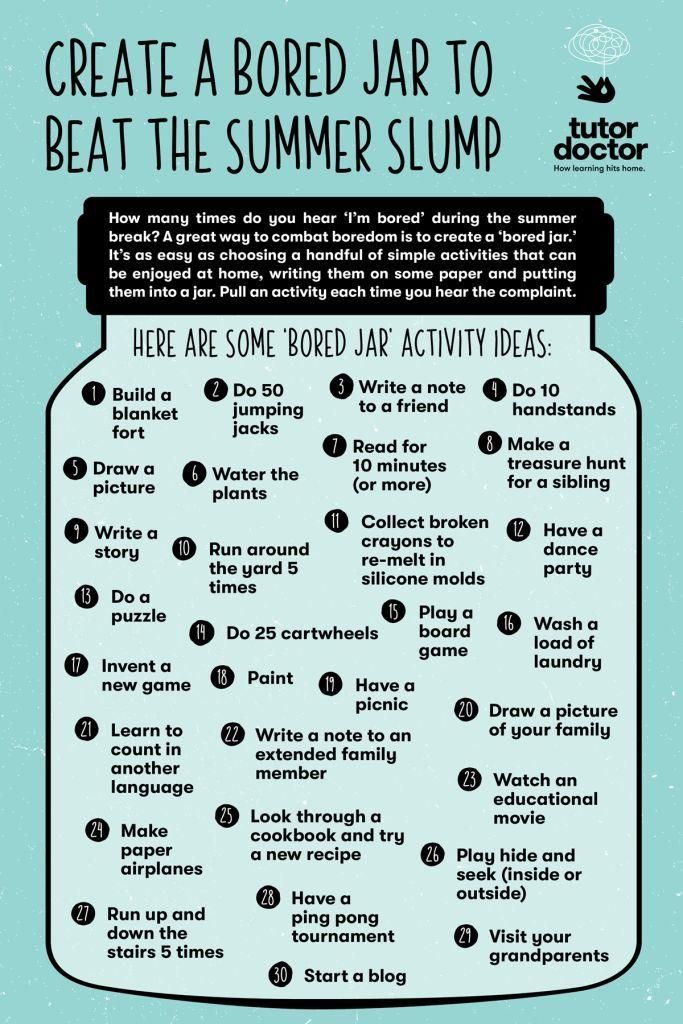

Child psychologist Melissa Bernstein talks about several ways to help your child not be afraid of boredom. Draw his attention to those toys that he already has - "old" things can be found in an unusual, new use. Melissa also advises that together with the child, make a list of activities that he can do. It doesn’t have to be useful things like cleaning or doing homework - it’s enough that it will help him stop worrying and find leisure for himself.

Draw his attention to those toys that he already has - "old" things can be found in an unusual, new use. Melissa also advises that together with the child, make a list of activities that he can do. It doesn’t have to be useful things like cleaning or doing homework - it’s enough that it will help him stop worrying and find leisure for himself.

Melissa calls inactivity the most effective method. Do not be nervous with the child, but rather relax, let him figure out for himself what to do.

As the son or daughter develops their approach to coping with boredom, the parent is learning patience.

The ability to observe a child instead of controlling him is a key parenting skill, and childish boredom is one of the easiest and safest ways to develop it. Learning to make choices and accept their consequences in middle and high school is going to be a lot harder—and a lot more exciting.

Long winter holidays are ahead, when both children and adults can easily get bored. Here is what psychologist Katerina Dyomina advises all parents: Here is what psychologist Katerina Dyomina advises all parents: “A roaming around the house, whining, whining, some kind of inflamed child is just a time bomb. Therefore, parents try to draw up an entertainment program for the holidays as tightly as possible: two Christmas trees, a play, a movie, a trip, visits to relatives. By the end of this, so to speak, "rest", both the child and the parents are already completely exhausted. And they curse in every way the legislators who invented these (wee-and-and-p) holidays. I want to ask parents: why not let the child live his boredom from beginning to end? Do not rush to entertain him, do not come up with options, do not turn on the electronics. After all, it is in these, in the opinion of an external observer, empty hours that the maturation of the soul takes place, ideas arise, ideas crystallize. The creator is manifested in the child. |

This material is part of a large project dedicated to the development of children's personal potential and key competencies of the 21st century.