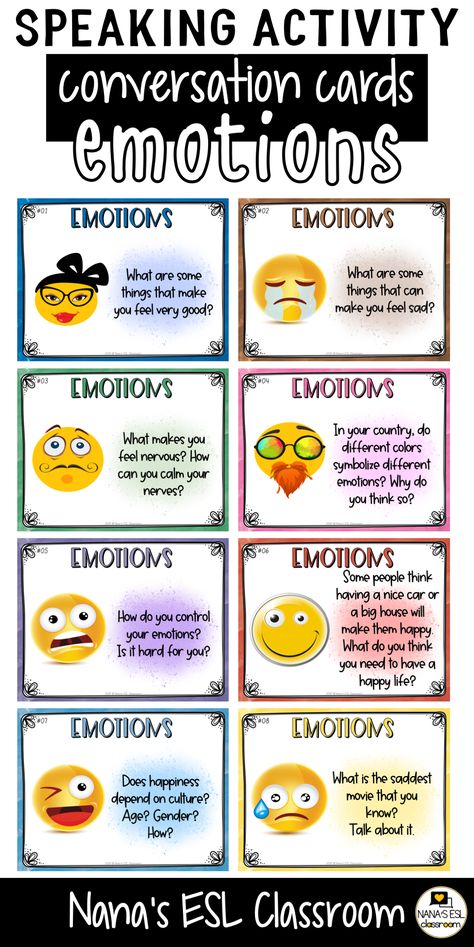

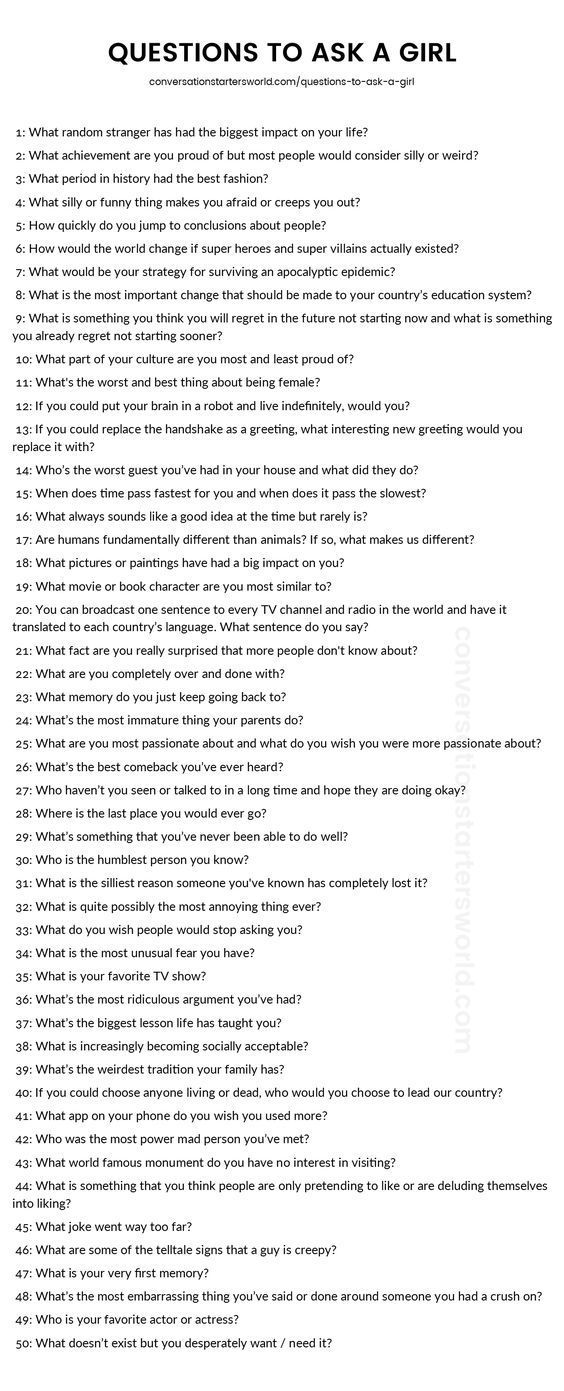

Discussion questions about stress

ESL Conversation Questions - Stress (I-TESL-J)

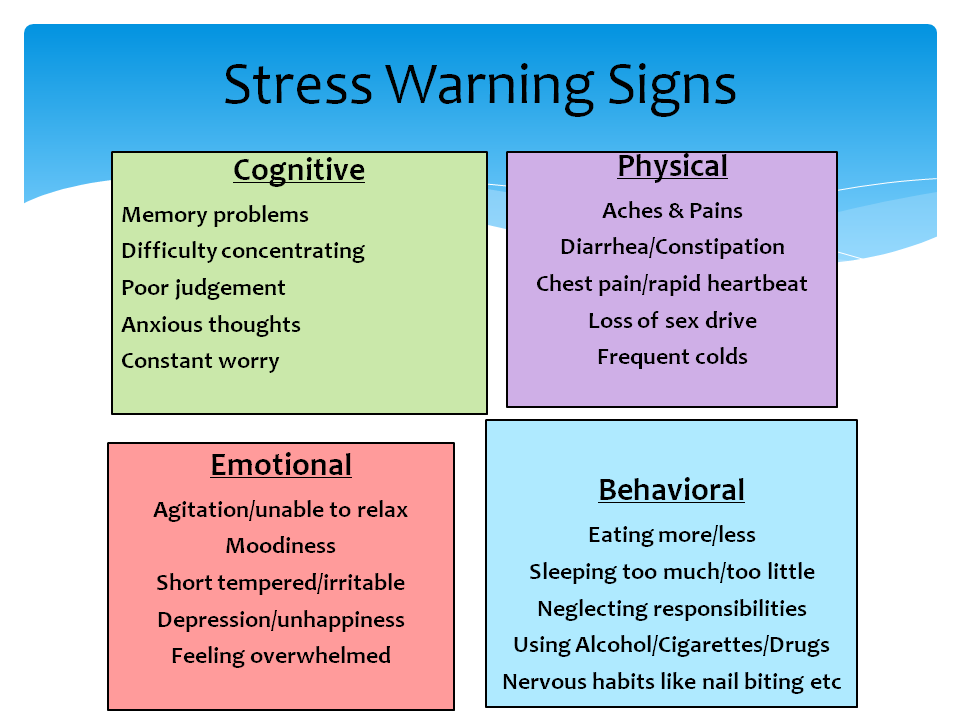

Recognizing Stress

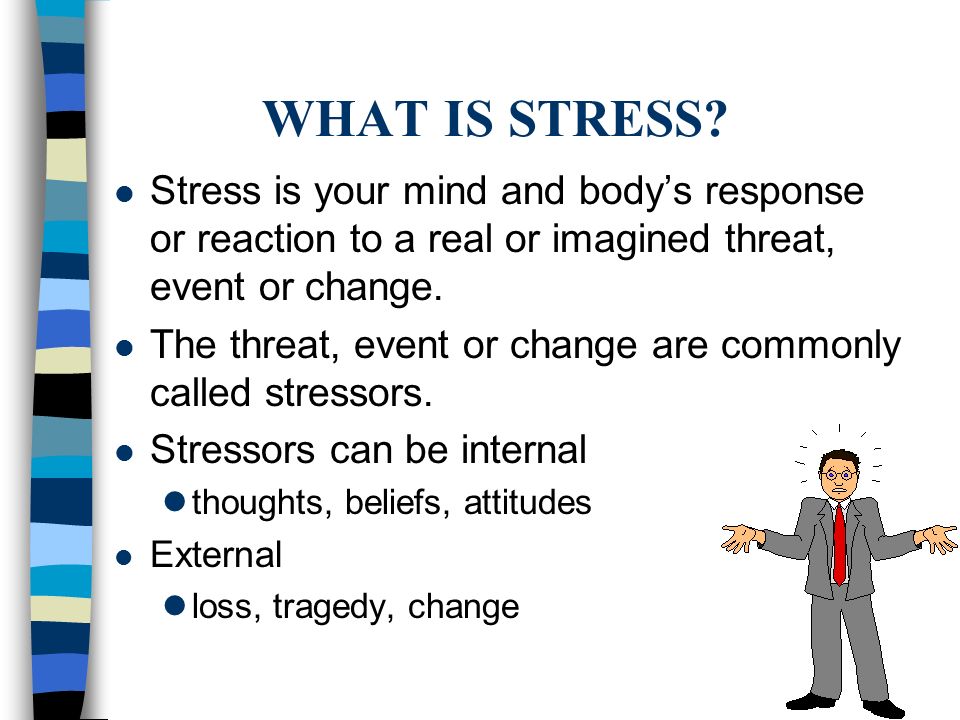

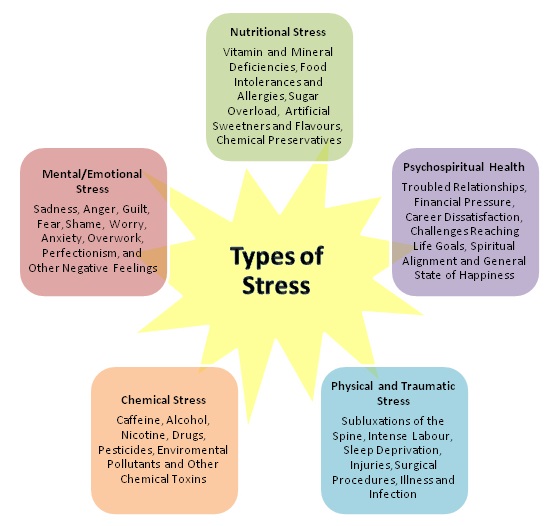

- What is stress?

- What causes stress?

- How do you recognize stress in your life?

- Have you been under stress recently?

- How does stress affect you?

- Do you have a kind of red warning flag that indicates too much stress?

- When you are stressful, how do you feel physically?

- Do you feel tired during the day?

- Can you sleep well at night?

- Does your stomach hurt?

- How do you feel emotionally?

- Do you feel nervous or worried about stressful situations?

- Do you get angry easily?

Helping Others

- Have you ever helped someone who was feeling stressful?

- What did you do?

- Did you give them advice?

- Did you listen to them?

- Did you do most of the talking?

- Did you take some action to help them?

- Have you ever helped someone that you didn't know?

- What are characteristics of a good counselor?

- Is it necessary to have shared the same experience?

- Is it important to be an expert?

- Is it important to be patient?

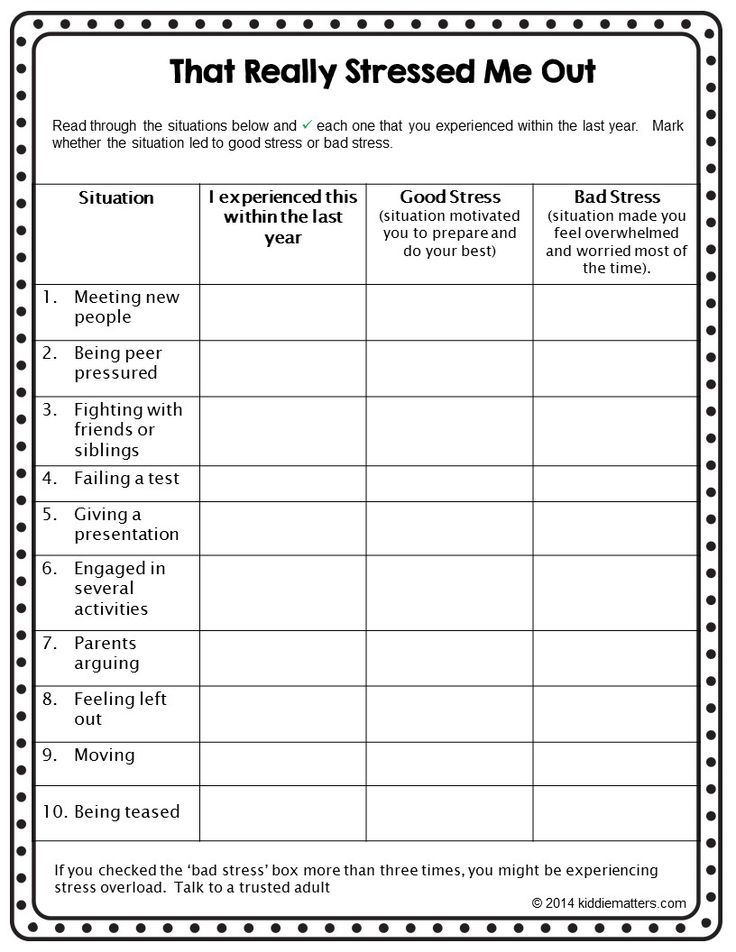

Healthy Stress

- Do you think stress is ever good, useful, or necessary?

- Why or why not?

- Do you play games or sports that are sometimes stressful?

- When can stress be a good thing?

- If you are playing a sport and your team is losing, does it give you extra energy?

- Does stress make you feel more alive?

- Is your home life stressful?

- Are you busy at home?

- Can you relax at home?

- Do you enjoy having discussions about politics with other people who have different opinions?

- Do you like to argue about different ways to do things at work or at home?

Personal

- Have you felt stress recently?

- Did the stressful feeling last a long time or a short time?

- Had the cause of the stress happened to you before or was this a new situation?

- How often do you think you feel too much stress?

- Do you feel too busy sometimes?

- In what way does a too full schedule lead to stress?

- Do you like being busy?

- If you are very busy at work or at school, do you have ways to balance your life?

- If you have nothing to do, do you enjoy yourself or do you get bored?

- Does stress make it hard for you to think or act?

- How can you judge what is the right amount of stress for you?

- Is your stress caused by relationships with other people?

- At work? At school?

- At home?

- With best friends?

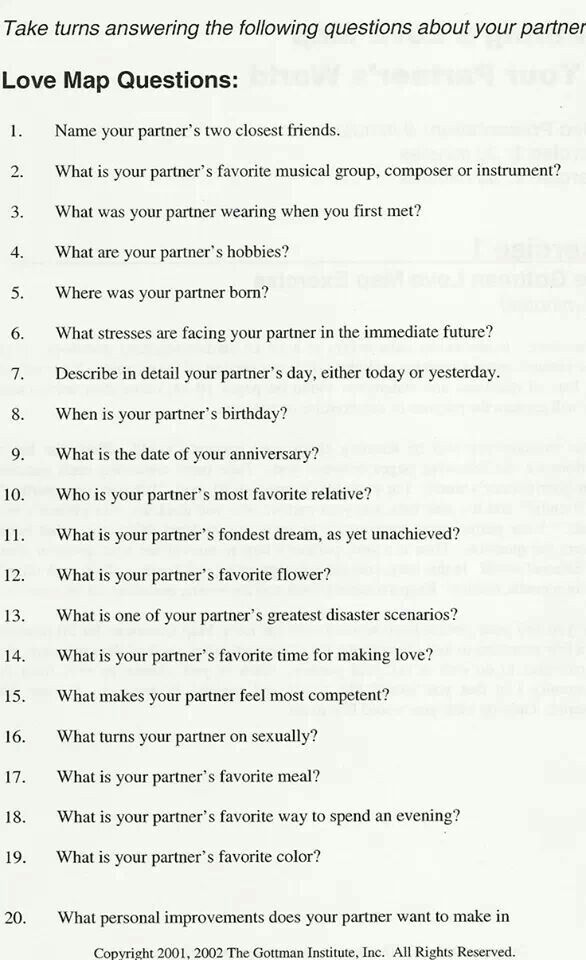

- With partners?

- Can you think of some examples?

- Does stress come when you worry about your life?

- Do you keep your worries a secret from other people?

- Do you have anyone you can talk to when you are worried?

- When did we start talking about stress as a psychological condition?

- What do you do when you have stress?

Stressful Situations

- Are there situations that you find stressful?

- Do you feel tense when you meet someone for the first time?

- Do you get nervous if you have to make a speech?

- Do you suffer from stress when you have too much work to do?

- Do you work or study for long hours under stressful conditions?

- Does the place you live have a low-stress environment?

- Can you be alone as much as you like?

- Can you be with friends as often as you like?

- Is it easy for you to make decisions about important things?

- Can you relax when you are sleeping away from home?

- In what kinds of situations do you observe other people feeling stressed?

- What are some situations that you enjoy?

- What are some situations that make you feel stressful?

- How can you eliminate stressful situations?

- Plan a low stress, cheap, one day holiday.

Controlling Stress

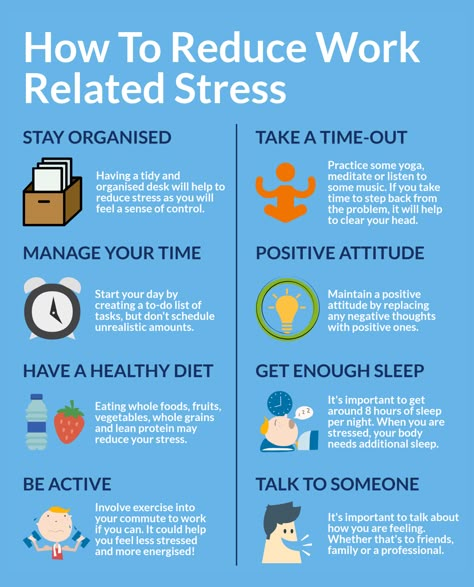

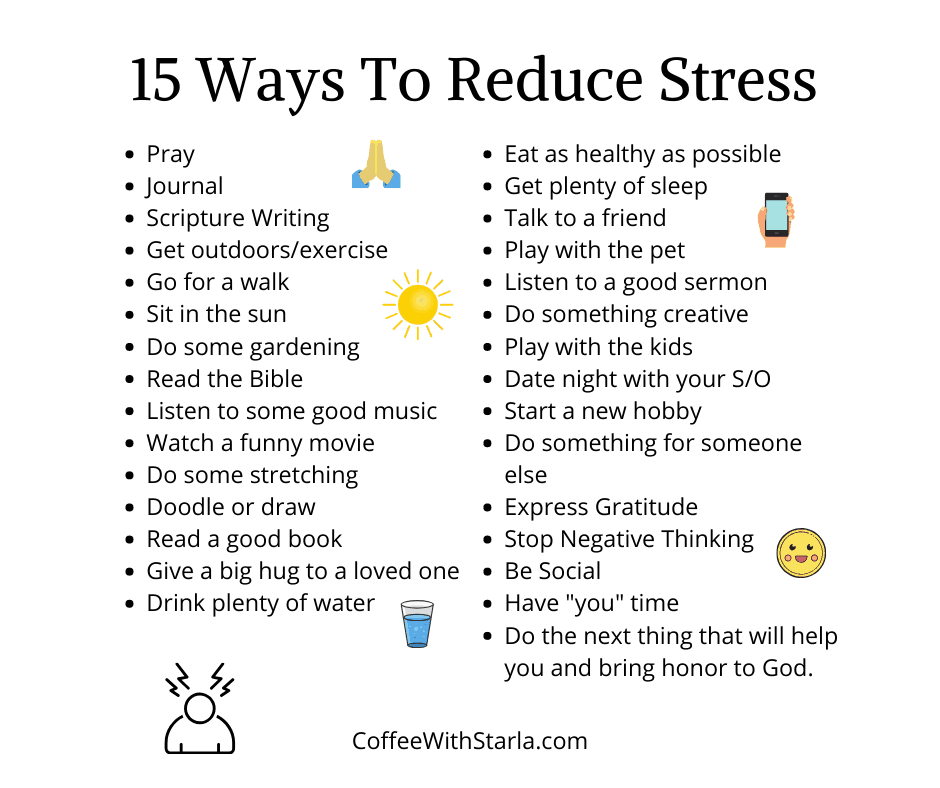

- How do you relieve stress?

- What stresses you out?

- Do you have a stressful lifestyle?

- How can you eliminate stressful situations?

- How do you get control of a stressful situation that is getting too tough?

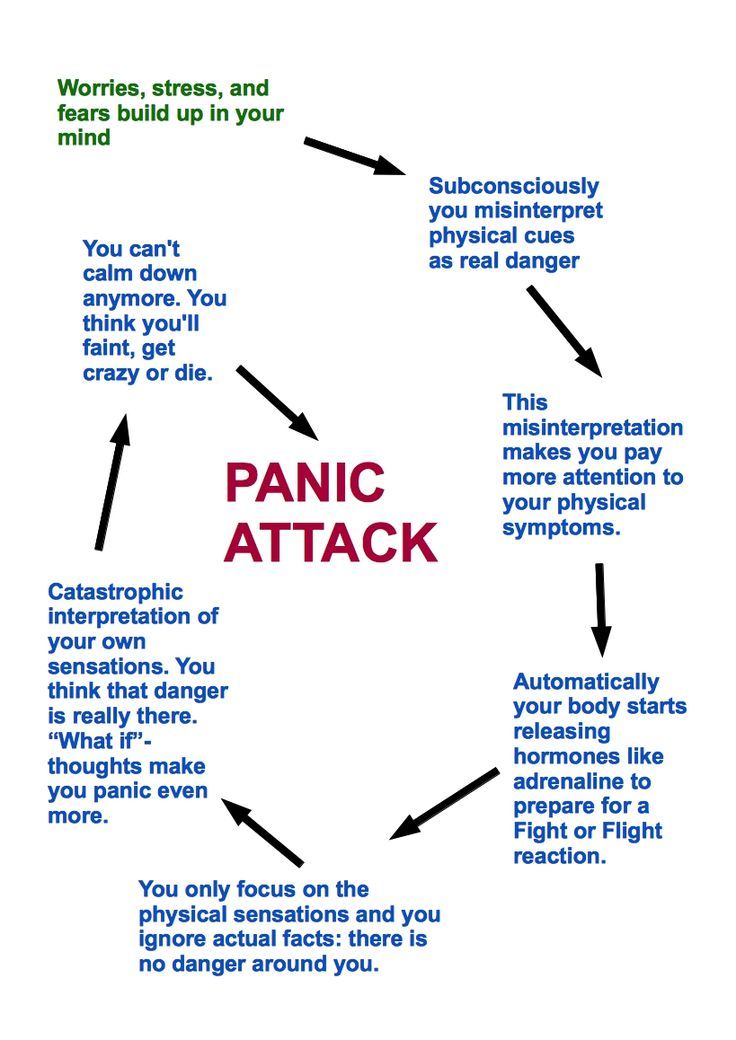

- What is the "fight or flight" response? How does it relate to stress?

- Do you enjoy the feeling of being stressed?

- If you are feeling stressed, what do you do?

- Do you like to relax or be active when stressful?

- Are you capable of relieving your stress or do you need help?

- Can alcohol cure stress temporarily?

Living Stress Free

- How can you live a stress free life?

- Can you give five suggestions that would be inexpensive?

- Can you give five suggestions for children?

- Can you give five suggestions for the wintertime?

- Give us suggestions for making school life less stressful.

- When stressful do you like to listen to a certain kind of music?

- Does it help to go shopping or take a long walk?

- Do you like to be alone or be with other people?

- Do you eat more or eat less?

- Do certain colors make you feel happier?

- Do you always follow the same pattern to relieve stress or do you try different things?

- What are some positive ways people deal with stress?

- What are some negative ways people deal with stress?

- How do you deal with stress?

- What is the most stressful experience you have ever had?

- When was the most stressful time of your life? Did you learn anything from that experience?

- What do you think is the greatest cause of stress for most people?

- What is your greatest cause of stress?

- Do you deal with stress differently that your parents do/did? If so, how?

- Do you know of anyone who likes to break things or become violent when they are stressed? What have they broken? What kind of violence do they do?

- What is the most stressful job you can think of?

- What is the least stressful job you can think of?

- Which would you choose: A stressful job with very high pay or a relaxing job with considerably low pay? Why?

- Is being single less stressful than married life? What are the advantages and disadvantages of each?

- How do you reduce stress in your life? Do you think they would be considered good or bad ways of dealing with stress?

If you can think of another good question for this list, please add it.

http://iteslj.org/questions/

Copyright © 1997-2010 by The Internet TESL Journal

Stress Discussion Questions - Making Sense of English

Contents

- Vocabulary and Idioms to Talk About Stress

- 16 questions for discussion that can be used in conversation classes or to practice English on your own or with a conversation partner

- A video for discussion by Arirang News about Korean children’s academic stress (학업 스트레스 최고지만 스스) followed by 3 questions for discussion

- A video with tips by BBC Brainsmart with 3 discussion questions

- 16 tips and tools and a link to an article with more tips and tools

- Time management tools by Francesco Cirillo, creator of the Pomodoro Technique

- Is Stress Good for You? vocabulary lesson by Shayna at Espresso English

Stress Is a Part of Life

Everyone has stress in their lives at some point or another. Some people have more than others. People deal with stress in different ways. Some ways are more beneficial than others. For some, talking with friends or family members is helpful. For others, writing in a diary provides insight and clarity when times are difficult.

People deal with stress in different ways. Some ways are more beneficial than others. For some, talking with friends or family members is helpful. For others, writing in a diary provides insight and clarity when times are difficult.

Many times, our attitude and thoughts about stress can determine how much it affects us. If we try to avoid it and hide from it, we often make whatever problem is causing it worse.

Procrastination can be helpful in small doses, but as a way of life, it can lead to more stress.

By facing our problems and dealing with them in a productive and healthy way, we can decrease our stress and start living more stress-free lives.

Vocabulary and Idioms to Talk About Stress

- I’m (so) stressed out.

- I need to de-stress.

- I have a lot on my plate.

- I’m at my wits end.

- I’m burned out.

- I’m at the end of my rope.

- I’ve been burning the candle at both ends.

- I don’t know whether I’m coming or going.

- I need to blow off some steam.

- I just want to kick back and relax.

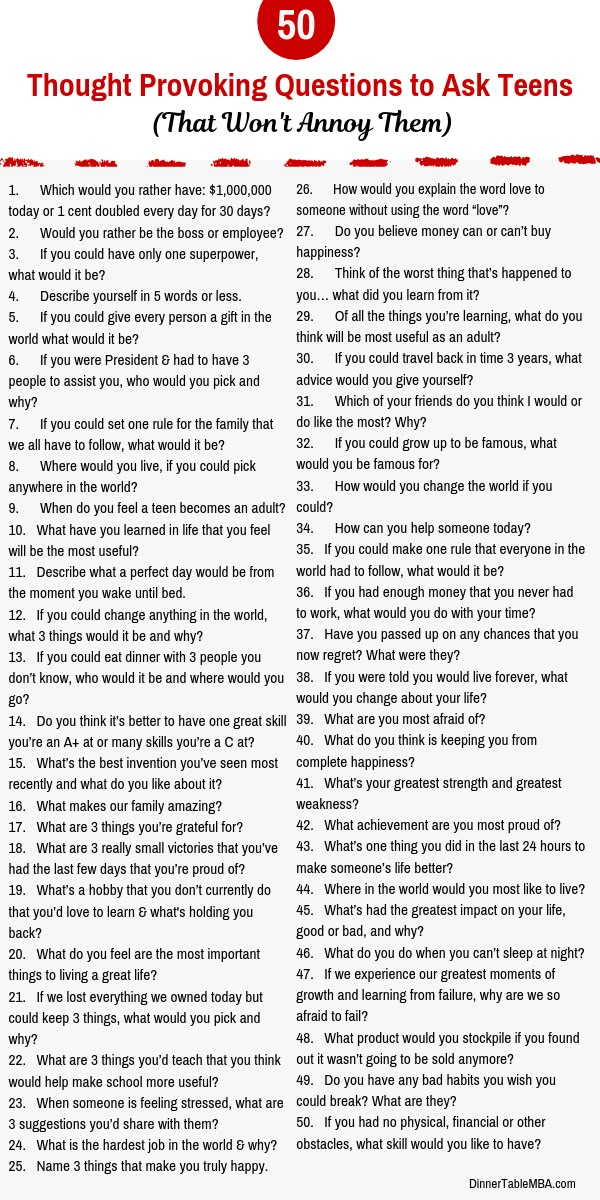

16 Questions for Discussing Stress

- What is stress?

- Is all stress bad?

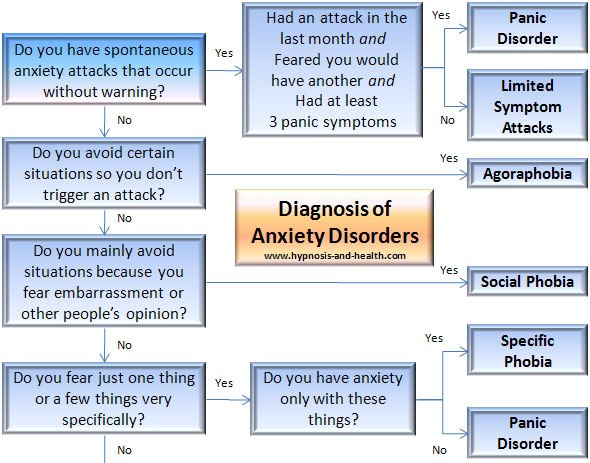

- What is the difference between stress and anxiety?

- What is the relationship between stress and sleep?

- What is the relationship between stress and food?

- What is the relationship between stress and money?

- What is the relationship between stress and technology?

- What are some examples of things that are stressful in life?

- How can stress be both positive and negative?

- What causes people the most stress?

- What are some ways people deal with stress?

- How do you usually cope with stress?

- What are some unhealthy ways that people try to relieve stress?

- What are some complications of stress?

- What are the healthiest ways to handle stress?

- What is your favorite way to de-stress?

Academic Stress in Korea

Watch the YouTube video “Korean children’s academic stress levels among world’s highest” by Arirang News. After watchin the video, discuss the three questions below.

After watchin the video, discuss the three questions below.

- What is your level of academic stress?

- Which is more stressful: high school or university? Why?

- If you could change the Korean education system, how would you change it?

BBC Brainsmart Video

Pre-read the questions below. Watch the YouTube video “Managing Stress – Brainsmart” by the BBC. Discuss the questions below.

- What is the purpose of stress and how has it changed in the 21st century?

- What 7 tips does the BBC give for managing stress? Can you think of additional tips?

- Which tips would you like to try?

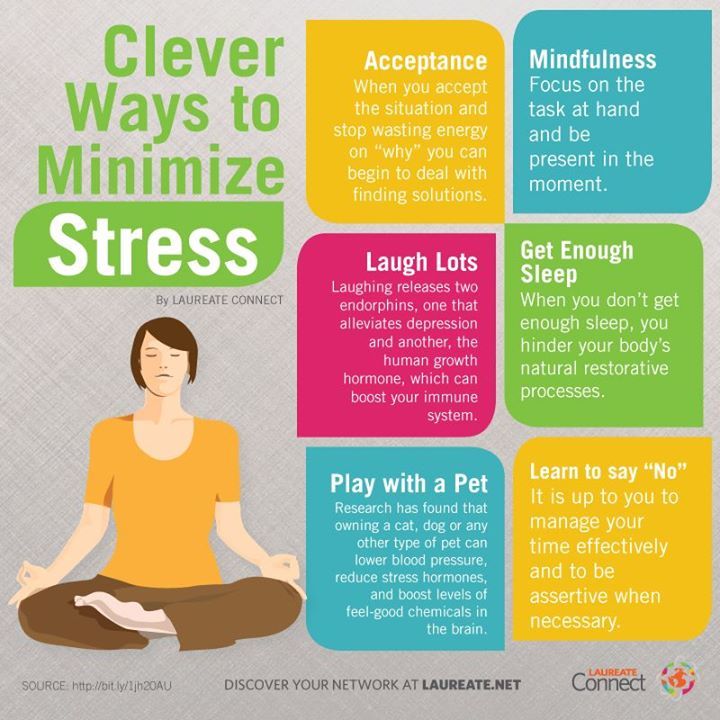

16 Tips and Tools for Dealing with Stress

- Exercise.

- Get adequate sleep.

- Take deep breaths.

- Identify the causes.

- Avoid unnecessary stress and learn to say no.

- Take control by taking steps to deal with whatever is causing you stress.

- Remember to take breaks. Make time for fun and relaxation.

- Talk to someone.

- Spend time in nature.

- Spend time with a pet.

- Try meditation. Even five minutes a day can be beneficial.

- Write in a diary.

- Keep a gratitude journal.

- Create opportunities for laughter.

- Sing!

- Dance!

For more tips and tools check out this article on stress management.

Time Management Tools

Check out the Pomodoro Technique.

Read books like Wait: The Art and Science of Delay

Espresso English Lesson

For a free English lesson, check out Is Stress Good for You by Shayna at Espresso English. The information there is free, but if you decide to purchase one of Shayna’s courses or e-books, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. I only recommend products and services that I trust and wish I had created myself.

Shayna’s lesson includes a reading, 12 vocabulary words, and a quiz to test yourself on the meaning of the 12 words.

Ready for a new topic? Check out ESL Conversation Topic: Creativity next.

Never stop learning!

Some debatable issues of clinical diagnostics of post-traumatic stress disorders

Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko, 2014 UDC 616.895

Correspondence

Lytkin Vladimir Mikhailovich - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Psychiatry, Military Medical Academy named after A.I. CM. Kirov» Ministry of Defense of Russia Address: 194044, St. Petersburg, st. Botkinskaya, 17 Phone: (812) 329-71-89 E-mail: [email protected]

V.M. Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko

Some controversial issues of posttraumatic stress disorder clinical diagnosis

V.M. Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko

Ever since PTSD's inclusion in DSM-III the diagnostic criteria of post-traumatic stress disorders continue to be the subject of intense study and heated debate. Lack of unified approach to understanding the PTSD and the uncertainty about current clinical criteria significantly complicate the practical activity of specialists in "disaster psychiatry". Bringing up for discussion a number of controversial issues relevant to the PTSD problem and their subsequent solution will contribute to improved delivery of psychological and mental health services to victims of disasters. Key words: posttraumatic stress disorders, clinical diagnosis, debatable points of clinical relevance

Bringing up for discussion a number of controversial issues relevant to the PTSD problem and their subsequent solution will contribute to improved delivery of psychological and mental health services to victims of disasters. Key words: posttraumatic stress disorders, clinical diagnosis, debatable points of clinical relevance

FSBEI HPE "Military Medical Academy. CM. Kirov

Ministry of Defense of Russia, St. Petersburg

S.M. Kirov Military Medical Academy, St. Petersburg

Since the DSM-III definition of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), diagnostic criteria for stress disorders have continued to be intensively studied and discussed. The lack of a unified approach to understanding the nature of PTSD and the problematic nature of modern clinical criteria significantly complicate the practice of specialists in the field of disaster psychiatry. The formulation of a number of debatable questions in the problem of PTSD and their subsequent solution will contribute to the further improvement of the provision of psychological and psychiatric care to victims in emergency situations. Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder,

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder,

clinical diagnostics, debatable moments of clinical interpretation

The results of numerous neurophysiological and biochemical studies of a fairly representative contingent of people affected by emergency situations (ES), which led to the creation of a number of biological models of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as the long-term development of psychodynamic , cognitive and psychosocial concepts in line with the psychological models of this disorder have not yet led to the creation of a single generally accepted theoretical approach explaining the etiology and mechanisms of the onset and development of PTSD [19, 26].

Currently, the legitimacy of classifying PTSD as a mental disorder is questioned. According to S.Yu. Tsirkin [29], the triad characteristic of PTSD in the presentation of the ICD-10 is a purely psychological formation. The problem of nosological independence of PTSD is also discussed in the works of E. V. Snedkov [13, 23]. Diagnostic criteria for PTSD,

V. Snedkov [13, 23]. Diagnostic criteria for PTSD,

62

V.M. Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko

for the first time set out in the DSM-III classification (1980), were subsequently subjected and are subjected (up to the present time) to refinement and differentiation [9].

According to the DSM-III, the first diagnostic category includes the etiological factor, the second, re-experiencing symptoms, the third, emotional withdrawal, and the fourth, the appearance of previously unobserved symptoms. According to these criteria, the diagnosis of PTSD was considered legitimate in the presence of an etiological factor and at least one symptom from the second and third groups and two from the fourth. It was this interpretation that, along with brevity, differed in clinical specificity and psychopathological orientation.

In DSM-III-R (1987), the number of symptoms required for verification increased from 4 to 7, the criterion “E” (“duration”) was added to the criteria that received letters, the features of PTSD in children were clarified and supplemented.

The DSM-IV (1994) classification for the first time includes the diagnostic term "acute stress disorder" (ASD), which refers to the initial stage of PTSD. Also, for the first time, "acute" and "chronic" types of the course were distinguished, as well as PTSD with a delayed onset of the disease. In accordance with this classification, all stress-related disorders were combined into 3 stages: ASD, acute PTSD and chronic PTSD. Along with psychopathological symptoms, some psychological concepts have also been introduced into the diagnostic framework of PTSD. With minor amendments, such an interpretation of PTSD with a tendency to psychologization is given in DSM-IV-R (2000).

Certain differences also exist in various classification and diagnostic approaches to PTSD. So, in the ICD-10, in contrast to the DSM, the presence of a latent period for the verification of a disorder becomes mandatory; during PTSD, acute and chronic stages are not distinguished; impaired social functioning as a manifestation of PTSD is not reflected in the European classification of diseases. The final attitude to OSR according to DSM-IV has not been determined: if a tendency to a protracted course is detected, it is probably not a reaction as such to stress, but the formation of a certain disorder in the so-called transitional period (according to Z.I. Kekelidze) (cited according to [16]). In this situation, it was noted that in 37% of patients who were diagnosed with PTSD in accordance with the ICD-10, it was not confirmed by DSM-IV. 448 experts from the American centers of the Veterans Aid Association [24] took part in the development of the criteria for PTSD, and the inclusion of this category of disorders in the ICD-10 was facilitated by many years of research conducted by 110 institutes in 40 countries under the auspices of WHO [21].

The final attitude to OSR according to DSM-IV has not been determined: if a tendency to a protracted course is detected, it is probably not a reaction as such to stress, but the formation of a certain disorder in the so-called transitional period (according to Z.I. Kekelidze) (cited according to [16]). In this situation, it was noted that in 37% of patients who were diagnosed with PTSD in accordance with the ICD-10, it was not confirmed by DSM-IV. 448 experts from the American centers of the Veterans Aid Association [24] took part in the development of the criteria for PTSD, and the inclusion of this category of disorders in the ICD-10 was facilitated by many years of research conducted by 110 institutes in 40 countries under the auspices of WHO [21].

The relevance of identifying this form of mental disorders for domestic psychiatry is obvious: numerous local conflicts, repeated terrorist attacks, natural and man-made disasters have led to a wide diagnostic prevalence of PTSD, although the ambiguity of the clinical interpretation of PTSD often leads to a significant statistical spread in terms of its detection: from 2, 6% of the total number of the surveyed population to 73-92% in risk groups (A. A. Churkin, cited in [16]). As J.Ch. Tsutsiev [30], according to foreign data, the number of countries using the diagnosis of PTSD in clinical practice, from 1998 to 2002 increased from 7 to 39. It is obvious that the identified trend of growth in research in the field of PTSD is associated primarily with the growth of international terrorist activity.

A. Churkin, cited in [16]). As J.Ch. Tsutsiev [30], according to foreign data, the number of countries using the diagnosis of PTSD in clinical practice, from 1998 to 2002 increased from 7 to 39. It is obvious that the identified trend of growth in research in the field of PTSD is associated primarily with the growth of international terrorist activity.

Various approaches to the clinical understanding of PTSD in domestic psychiatry reveal a number of fundamental provisions that suggest the substantiation of certain author's positions: 1) is the introduction of diagnostic criteria for PTSD fundamentally new in the theory of psychogenies; 2) what is the clinical level of PTSD, its mono- or polysyndromicity; 3) PTSD is an independent taxon or stage of a single disease process; 4) PTSD comorbidity, etc.

It is generally accepted that the inclusion of a diagnostic description of PTSD in DSM-III (1980) by the American Psychiatric Association was primarily of high social significance due to the fact that by that time extensive factual material had accumulated on the development of psychogenic disorders of a special type in veterans, primarily Vietnam War. These clinically well-defined disorders, however, did not fit into any of the previously known nosological forms. However, according to E.V. Snedkova (2009) [23], the diagnostic criteria for PTSD introduced in the DSM-III, DSM-IV and ICD-10 can hardly be regarded as a significant progress in the theoretical understanding of psychogeny: in essence, they are identical to the criteria for diagnosing reactive states, formulated by K. Jaspers in 1913. Already at that time, both the option of a delayed response to psychotrauma and descriptions of the extraordinary nature of the event in terms of its significance and severity for a particular individual were known. According to E.V. Snedkov [23], in the official description of PTSD, nothing more than a syndrome - a typical non-specific pathological condition, in which, by the way, "axial" symptoms are not included in the diagnostic list. This syndrome can occur in the structure of various mental disorders.

These clinically well-defined disorders, however, did not fit into any of the previously known nosological forms. However, according to E.V. Snedkova (2009) [23], the diagnostic criteria for PTSD introduced in the DSM-III, DSM-IV and ICD-10 can hardly be regarded as a significant progress in the theoretical understanding of psychogeny: in essence, they are identical to the criteria for diagnosing reactive states, formulated by K. Jaspers in 1913. Already at that time, both the option of a delayed response to psychotrauma and descriptions of the extraordinary nature of the event in terms of its significance and severity for a particular individual were known. According to E.V. Snedkov [23], in the official description of PTSD, nothing more than a syndrome - a typical non-specific pathological condition, in which, by the way, "axial" symptoms are not included in the diagnostic list. This syndrome can occur in the structure of various mental disorders.

Critically evaluates the well-known criteria for PTSD and V. M. Garnov [6]. In his opinion, of all the listed groups, only group D contains signs that can be confidently attributed to clinical signs. They include symptoms such as disturbed sleep, increased irritability, and increased fearfulness. The remaining 4 groups of signs cannot be fully called clinical symptoms. So, the signs that make up group A indicate an etiological factor. The signs of “re-experiencing the psychological trauma by the victims” that make up group B, as follows from the literary sources, denote “the mechanism of fixation on the trauma, which indicates the unsuccessful integration of traumatic experience into the integral structure of the life experience of the individual.” The "persistent avoidance of trauma-related stimuli" features in group C are commonly described as "a mechanism designed to provide protection against anxiety-producing stimuli". The presented categories, according to V.M. Garnov, rather point to the pathoplastic mechanisms of the formation of psychopathology, and not to formalized clinical signs.

M. Garnov [6]. In his opinion, of all the listed groups, only group D contains signs that can be confidently attributed to clinical signs. They include symptoms such as disturbed sleep, increased irritability, and increased fearfulness. The remaining 4 groups of signs cannot be fully called clinical symptoms. So, the signs that make up group A indicate an etiological factor. The signs of “re-experiencing the psychological trauma by the victims” that make up group B, as follows from the literary sources, denote “the mechanism of fixation on the trauma, which indicates the unsuccessful integration of traumatic experience into the integral structure of the life experience of the individual.” The "persistent avoidance of trauma-related stimuli" features in group C are commonly described as "a mechanism designed to provide protection against anxiety-producing stimuli". The presented categories, according to V.M. Garnov, rather point to the pathoplastic mechanisms of the formation of psychopathology, and not to formalized clinical signs. OK. Khokhlov [28] notes that in PTSD, a constellation of pathogenic factors (psychogenic, exogenous, exogenous-organic, personal-endogenous) is stated. PTSD is considered by the author as a combined comorbid pathology, which is not entirely legitimate to define mainly as a mental pathology, since sometimes comorbid pathology even masks PTSD itself. A.B. Smulevich [22] considers PTSD in relation to protracted nosogenic depressions. He points out that PTSD in patients of general medical practice is most often associated with the psycho-traumatic effect of a serious illness (myocardial infarction, bronchial asthma), abdominal operations or oncological pathology.

OK. Khokhlov [28] notes that in PTSD, a constellation of pathogenic factors (psychogenic, exogenous, exogenous-organic, personal-endogenous) is stated. PTSD is considered by the author as a combined comorbid pathology, which is not entirely legitimate to define mainly as a mental pathology, since sometimes comorbid pathology even masks PTSD itself. A.B. Smulevich [22] considers PTSD in relation to protracted nosogenic depressions. He points out that PTSD in patients of general medical practice is most often associated with the psycho-traumatic effect of a serious illness (myocardial infarction, bronchial asthma), abdominal operations or oncological pathology.

At the same time, according to the positions of the State Scientific Center for Social and Forensic Psychiatry. V.P. Serbsky, the basic principles of diagnosing PTSD have remained the same for more than 20 years, which proves the clinical reality of the identified form of mental disorder. According to Yu.A. Aleksandrovsky (2005) [2], PTSD, in essence, is a modern definition of psychogenies known in the past in people who experienced emergencies, described in terms of psychogenic reactions, states and personal developments. Comparison of the characteristics of psychogenic disorders during a life-threatening situation and immediately after its completion with the options for the subsequent development of PTSD allows us to answer, according to Yu.A. Aleksandrovsky, to the question about the "novelty" and "independence" of the diagnosis of PTSD and various evaluative formulations of the stages of its development. At the same time, PTSD is one of the remote stages of the dynamic development of psychogenetically provoked disorders, PTSD is

Comparison of the characteristics of psychogenic disorders during a life-threatening situation and immediately after its completion with the options for the subsequent development of PTSD allows us to answer, according to Yu.A. Aleksandrovsky, to the question about the "novelty" and "independence" of the diagnosis of PTSD and various evaluative formulations of the stages of its development. At the same time, PTSD is one of the remote stages of the dynamic development of psychogenetically provoked disorders, PTSD is

part of socially provoked as a result of stressful mental disorders. Highlighting the main criteria that unite PTSD and separate it from other borderline conditions (the fact of a stressful state during an emergency, flashes of memories, avoidance, a complex of neurasthenic disorders and stigmatization of individual symptoms), the author notes that each of the listed criteria is not specific only for PTSD , however, combined together, they constitute a fairly typical clinical picture. At the same time, it should be taken into account that the occurrence of PTSD in each particular person is determined by the mutual influence of factors called predictors of personal vulnerability, which include unpreparedness for the impact of trauma, previous negative experience, passivity of coping strategies developed during life, mental and somatic diseases. According to V.G. Vasilevsky, G.A. Fastovtsov (quoted from [16]), the nosological independence of PTSD is a clinical reality and is confirmed not only by the inclusion of this pathology in the ICD-10, but also by the specific features of the phenomenology of combat PTSD. The real clinical picture of combat PTSD, according to these authors, is much richer and more complex than that outlined in the ICD-10. For the clinical picture of combat PTSD, the presence of inversion symptoms is specific, which move between the poles of the neurotic and psychotic register from minimal to maximum severity. In practice, there are transitions from episodic hypothymia to persistent depression, from obsessive memories of combat impressions to painful eidetic echomnesia, from anxiety to diffuse, unmotivated fear, from alertness to suspicion, from overvalued fears to paranoid mood, etc.

At the same time, it should be taken into account that the occurrence of PTSD in each particular person is determined by the mutual influence of factors called predictors of personal vulnerability, which include unpreparedness for the impact of trauma, previous negative experience, passivity of coping strategies developed during life, mental and somatic diseases. According to V.G. Vasilevsky, G.A. Fastovtsov (quoted from [16]), the nosological independence of PTSD is a clinical reality and is confirmed not only by the inclusion of this pathology in the ICD-10, but also by the specific features of the phenomenology of combat PTSD. The real clinical picture of combat PTSD, according to these authors, is much richer and more complex than that outlined in the ICD-10. For the clinical picture of combat PTSD, the presence of inversion symptoms is specific, which move between the poles of the neurotic and psychotic register from minimal to maximum severity. In practice, there are transitions from episodic hypothymia to persistent depression, from obsessive memories of combat impressions to painful eidetic echomnesia, from anxiety to diffuse, unmotivated fear, from alertness to suspicion, from overvalued fears to paranoid mood, etc.

There are different points of view regarding the staging of PTSD itself and its place within the framework of a single pathological process (from the moment of psychogenic impact to the formation of a characteristic disease state, according to Yu.A. Aleksandrovsky) [2]. A number of authors also describe specific stages in the development of PTSD. So, T.B. Dmitrieva, B.S. Polozhiy (2002) [7] single out the initial (preclinical) stage, the stage of neurotic disorders, and the stage of patho-characterological personality changes (after 2 years) with a number of clinical variants in each of the stages. I.G. Malkina-Pykh (2005) [15] believes that the development of PTSD in war veterans is characterized by 5 phases: initial exposure, resistance-denial, acceptance-suppression, decompensation, coping with trauma, and recovery. It is noted that almost all combatants have a long

64

V.M. Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko

some time after the war, pronounced primary symptoms of PTSD appear, which include re-experiencing the trauma (recurring nightmares, psychological distress arising from certain combat associations, obsessive memories of military events), emotional impoverishment with avoidance of stimuli associated with trauma and symptoms of increased excitability (sleep disorders, increased irritability, anger, rage, a tendency to violence). Secondary symptoms of PTSD in combatants include depression, anxiety, impulsive behavior, substance abuse, somatic problems, and impaired ego functioning. N.L. Bundalo (2008) [3] in the dynamics of PTSD describes the stage of initial clinical manifestations, the neurotic stage and the stage of psychotism. V.G. Vasilevsky, G.A. Fastovtsov (quoted from [16]) indicate a certain staging of the pathogenesis of combat PTSD: "acute reaction to stress" - "neurotic disorders" corresponding to adjustment disorders with a predominance of emotions, - "pathocharacterological manifestations" corresponding to combatant accentuation, - PTSD corresponding to the requirements of section F 43.1 of the ICD-10 with clinically unfolded protracted forms of "chronic personality changes after experiencing a catastrophe." Based on the model of combat veterans, the following types of PTSD course were proposed (Nash W.P., 2011, cited from [18]): chronic, delayed, regenerative, inoculative, resistant, as well as a type of course with personal growth.

Secondary symptoms of PTSD in combatants include depression, anxiety, impulsive behavior, substance abuse, somatic problems, and impaired ego functioning. N.L. Bundalo (2008) [3] in the dynamics of PTSD describes the stage of initial clinical manifestations, the neurotic stage and the stage of psychotism. V.G. Vasilevsky, G.A. Fastovtsov (quoted from [16]) indicate a certain staging of the pathogenesis of combat PTSD: "acute reaction to stress" - "neurotic disorders" corresponding to adjustment disorders with a predominance of emotions, - "pathocharacterological manifestations" corresponding to combatant accentuation, - PTSD corresponding to the requirements of section F 43.1 of the ICD-10 with clinically unfolded protracted forms of "chronic personality changes after experiencing a catastrophe." Based on the model of combat veterans, the following types of PTSD course were proposed (Nash W.P., 2011, cited from [18]): chronic, delayed, regenerative, inoculative, resistant, as well as a type of course with personal growth. The degree of clinical severity of PTSD is also quite variable. The “F” criterion introduced in DSM-IV, which determines this degree, suggests the diagnosis of PTSD as a “clinically significant, severe emotional state”, to which the so-called prenosological forms of this disorder cannot be attributed. N.L. Bundalo (2008) [3] identifies mild, moderate, and severe PTSD based on the intensity of distress. At the same time, in military psychiatry there is the concept of "combatant accentuation" [14], which is dynamic-situational in nature and is understood as a set of personality-character-logical features acquired as a result of direct participation in hostilities, the dynamics of which is determined by the specifics of combat and peaceful conditions. existence, and manifestations - by various options for the interaction of combatants themselves, which determine their different social adaptation. The very fact of their verification can be considered as a kind of "background" ("soil") for the possibility of polynosological neuropsychiatric disorders.

The degree of clinical severity of PTSD is also quite variable. The “F” criterion introduced in DSM-IV, which determines this degree, suggests the diagnosis of PTSD as a “clinically significant, severe emotional state”, to which the so-called prenosological forms of this disorder cannot be attributed. N.L. Bundalo (2008) [3] identifies mild, moderate, and severe PTSD based on the intensity of distress. At the same time, in military psychiatry there is the concept of "combatant accentuation" [14], which is dynamic-situational in nature and is understood as a set of personality-character-logical features acquired as a result of direct participation in hostilities, the dynamics of which is determined by the specifics of combat and peaceful conditions. existence, and manifestations - by various options for the interaction of combatants themselves, which determine their different social adaptation. The very fact of their verification can be considered as a kind of "background" ("soil") for the possibility of polynosological neuropsychiatric disorders. At the same time, it is noted that the change in the functioning of the personality after leaving the extreme situation can go both regressively and

At the same time, it is noted that the change in the functioning of the personality after leaving the extreme situation can go both regressively and

and in a progressive (positive) direction, and depending on individual constellations of biological, personal factors, the severity of acquired, acquired personality changes can vary from hidden accentuation to gross psychopathization. In general, with combatant accentuation, we are talking about manifestations of PTSD at the pre-nosological level. Research by I.V. Shadrina et al. [31] supplemented this concept with the fact that within the framework of the so-called predisposition to the formation of accentuations, the factor of residual organic cerebral insufficiency is also very significant. The organic combatant personality they single out is seen as a threat to the stability of society.

N.V. Tarabrin [25], S.A. Solovieva [27] believe that PTSD is a non-psychotic delayed reaction to traumatic stress that can cause mental disorders in almost any person (such as natural and man-made disasters, military operations, torture, rape, etc. ). According to N.V. Tarabrina [26], at the psychological level, the symptoms of PTSD represent a set of interrelated psychological characteristics (symptom complex), which is included in the semantic field of the concept of "post-traumatic stress".

). According to N.V. Tarabrina [26], at the psychological level, the symptoms of PTSD represent a set of interrelated psychological characteristics (symptom complex), which is included in the semantic field of the concept of "post-traumatic stress".

VG Rothstein (cited in [20]) considers PTSD as a complex of mental disorders arising in connection with extreme situations. Its clinical picture appears to the author as a combination of psychopathic behavioral disorders (asocial, explosive, hysterical), aggravated by alcoholism, drug use, and severe neurosis-like symptoms. According to military psychiatrists [13], combat PTSD is a protracted or delayed conditionally adaptive mental changes and mental disorders that occur as a result of exposure to combat environment factors. It is noted that some of these mental changes in war may be of an adaptive nature, and in civilian life they sometimes lead to various forms of social maladaptation.

According to V.K. Shamrey et al. (2013) (quoted from [18]), establishing the correct syndromic, and even more so clinical diagnosis at the primary stages of medical care, as a rule, is impossible. That is why it is advisable to attribute the victim to one of the following groups according to the level of mental disorders, namely: the level of mental health, psychological (preclinical), borderline (neurotic) and psychotic levels.

That is why it is advisable to attribute the victim to one of the following groups according to the level of mental disorders, namely: the level of mental health, psychological (preclinical), borderline (neurotic) and psychotic levels.

According to some authors, the clinical picture of PTSD is characterized by polymorphism and polysyndromicity. So, V.M. Voloshin [5] believes

F

Russian Psychiatric Journal No. 1, 2014

65

THERAPY OF THE MENTALLY Ill

avoidance disease. At the same time, the different psychopathological structure of depression in PTSD and its correlation with other symptoms allow the author to speak about the syndrome-forming role of the dominant depressive affect in PTSD and to identify various types of chronic PTSD at the early stages of the development of psychogenic disorders: anxious, dysphoric, apathetic and somatoform. According to N.L. Bundalo (2008) [3], the polymorphic picture of PTSD includes manifestations of a neurotic level, psychotism, dissociative disorders, psychological disorders, and personality level disorders. In the clinical structure of PTSD, the author identified obligate (primary) and facultative (secondary) syndromes. Obsessive-compulsive, anxious and derealization-depersonalization syndromes were classified as obligate, phobic, depressive, paranoid and somatization syndrome were classified as facultative.

In the clinical structure of PTSD, the author identified obligate (primary) and facultative (secondary) syndromes. Obsessive-compulsive, anxious and derealization-depersonalization syndromes were classified as obligate, phobic, depressive, paranoid and somatization syndrome were classified as facultative.

At present, the clinical characterization of PTSD is carried out mainly in line with the concept of a single psychogenic disease process developed in recent years in domestic psychiatry of catastrophes [1, 2], according to which, within the framework of this process in emergencies, there is an inseparable connection of all mental disorders, and in the long-term period, the validity of the general theoretical concept of A.D. Speransky about the "second blow" in the nervous and mental activity, causing "trace irritation" of the previous impact. In particular, A.O. Bukhanovsky, K.Yu. Galkin (2001) [4] describe the model of a "single psychogenic post-traumatic disorder", which has a peculiar periodization of development. The authors identify different stages in this model, which are represented by independent taxa ICD-10 and DSM-IV: acute reaction to stress - acute stress disorder - PTSD - stable personality changes after a catastrophe. In the same period, V.M. Garnov [6] described the following stages of the formation of psychopathology in emergencies: an acute reaction to stress - the stage of polymorphic psychopathological symptoms - the stage of structuring, i.e. the formation of a certain direction of mental response - the stage of relative stabilization of the psychopathological manifestations that have arisen, i.e. development of PTSD itself.

The authors identify different stages in this model, which are represented by independent taxa ICD-10 and DSM-IV: acute reaction to stress - acute stress disorder - PTSD - stable personality changes after a catastrophe. In the same period, V.M. Garnov [6] described the following stages of the formation of psychopathology in emergencies: an acute reaction to stress - the stage of polymorphic psychopathological symptoms - the stage of structuring, i.e. the formation of a certain direction of mental response - the stage of relative stabilization of the psychopathological manifestations that have arisen, i.e. development of PTSD itself.

According to S.A. Kolov [11], in the modern concept of PTSD there is no clear differentiation between normal functioning and pathology, such clinical symptoms of PTSD in combat veterans, for example, as hyperreactivity, are more adaptive than painful. There are no clearly defined boundaries for all symptomatic clusters of PTSD, their identity with other psychopathological categories is noted: depression, obsessions, etc. The description of PTSD according to ICD-10 emphasizes the clearly exogenous nature of this disease, but there is absolutely no characteristic of the dynamics of the disease, the features of its course. According to the author, the principle of direct determinism used in the diagnostic category of PTSD according to ICD-10 is poorly consistent with the modern biopsychosocial scientific approach, in which specific causes are replaced by complex chains of events and consequences that are in constant interaction. Previously, it was suggested that the isolation of PTSD should be considered as the next stage in the study of the impact of extraordinary mental trauma on a person's mental health [8].

The description of PTSD according to ICD-10 emphasizes the clearly exogenous nature of this disease, but there is absolutely no characteristic of the dynamics of the disease, the features of its course. According to the author, the principle of direct determinism used in the diagnostic category of PTSD according to ICD-10 is poorly consistent with the modern biopsychosocial scientific approach, in which specific causes are replaced by complex chains of events and consequences that are in constant interaction. Previously, it was suggested that the isolation of PTSD should be considered as the next stage in the study of the impact of extraordinary mental trauma on a person's mental health [8].

In the perspective of the upcoming revision of the current classification of mental and behavioral disorders, we should focus on the fact that, as quite rightly noted by V.N. Krasnov [12], the majority of Russian-speaking psychiatrists, especially those who have significant experience in treating victims of large-scale disasters, military operations or terrorist acts, are critical of the too wide distribution of the clinical diagnosis of PTSD. In his opinion, a significant part of the conditions referred to in English-language publications as PTSD are interpreted in Russian sources in a different way: as prolonged depression or polymorphic conditions, as combinations of dysthymic disorders, mild cognitive impairment, personality deviations and psychosomatic dysfunctions, sometimes with excessive alcohol consumption. or taking drugs. The nature of these disorders can be understood as multifactorial rather than exclusively psychotraumatic.

In his opinion, a significant part of the conditions referred to in English-language publications as PTSD are interpreted in Russian sources in a different way: as prolonged depression or polymorphic conditions, as combinations of dysthymic disorders, mild cognitive impairment, personality deviations and psychosomatic dysfunctions, sometimes with excessive alcohol consumption. or taking drugs. The nature of these disorders can be understood as multifactorial rather than exclusively psychotraumatic.

In addition, it is noted that at present this heading F43.1 in the ICD-10 is allocated not on the basis of the etiopathogenetic principle, but by combining the stable constellations of clinical signs established as a result of the studies and the alleged cause of the disorder [10]. According to the authors, the not entirely successful name “post-traumatic” does not correspond to its clinical essence; in the author’s practice, there have been observations showing the presence of this symptom complex without the criterion “A” - a direct threat to life, while simultaneously expansive interpretation of it by Western colleagues, which leads to the overdiagnosis of this disorder. In settlement

In settlement

66

V.M. Lytkin, V.V. Nechiporenko

Russian Manual of Psychiatry (edited by Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences A.S. Tiganov, 2012) [17] post-traumatic stress syndrome (or post-traumatic stress disorder) is defined as a delayed protracted reaction to a stressful event or situation (short or long) threatening or catastrophic.

In conclusion, it should be emphasized once again that the problem of PTSD is now becoming,

Information about the authors

Taking into account the steady growth of various kinds of emergency situations, more and more relevant not only in medical but also in social aspects, and its development is one of the promising areas of modern clinical psychiatry and medical psychology. As noted by Edna B. Foa, Terence M. Keene, Matthew J. Friedman [32], there is now “a growing conviction that PTSD is a universal response to traumatic events that occurs in many cultures and societies.”

Lytkin Vladimir Mikhailovich - Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Department of Psychiatry, Military Medical Academy named after A. I. CM. Kirov” of the Ministry of Defense of Russia (St. Petersburg) E-mail: [email protected]

I. CM. Kirov” of the Ministry of Defense of Russia (St. Petersburg) E-mail: [email protected]

Nechiporenko Valery Vladimirovich - Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Department of Psychiatry, FSBEI HPE “Military Medical Academy named after M.V. CM. Kirov» Ministry of Defense of Russia (St. Petersburg) E-mail: [email protected]

Literature

1. Aleksandrovsky Yu.A. Borderline mental disorders. - Rostov n/a, 1997. - P. 412.

2. Aleksandrovsky Yu.A. // Ros. psychiatrist. magazine - 2005. - No. 1. - S. 4-12.

3. Bundalo N.L. Post-traumatic stress disorder: Abstract of the thesis. dis. ... Dr. med. Sciences. - St. Petersburg, 2008.

4. Bukhanovsky A.O., Galkin K.Yu. Materials of the 3rd scientific. conf. Serial killings and social aggression: what awaits us in the 21st century? - Rostov n / D, 2001. - S. 97-100.

5. Voloshin V.M. Post-traumatic stress disorder. - M., 2005. - S. 200.

6. Garnov V.M. War and Mental Health / Ed. VC. Shamrey. - St. Petersburg, 2002. - S. 172-183.

VC. Shamrey. - St. Petersburg, 2002. - S. 172-183.

7. Dmitrieva T.B. Polozhiy B.S. War and Mental Health / Ed. VC. Shamrey. - SPb., 2002. - S. 183-189.

8. Kamenchenko P.B. Mental disorders in traumatic limb amputations: Abstract of the thesis. dis. . cand. honey. Sciences. - M., 1992.

9. Kekelidze Z.I., Portnova A.A. // Journal. nevrol. and a psychiatrist. them. S.S. Korsakov. - 2009. - No. 12. - S. 4-7.

10. Koren E.V., Tatarova I.N., Marchenko A.M. etc. // Sots. and wedge. psychiatrist. - 2009. - No. 4. - S. 34-41.

11. Kolov S.A. Actual problems of clinical, social and military psychiatry / Ed. VC. Shamrey. - St. Petersburg, 2013. - S. 95-105.

12. Krasnov V.N. Affective spectrum disorders. - M., 2011. - P. 432.

13. Litvintsev S.V., Snedkov E.V., Reznik A.M. Combat psychic trauma: A guide for physicians. - M., 2005. - S. 432.

14. Lytkin V.M. Problems of rehabilitation / Ed. IN AND. Zakharov. - SPb., 2001. - S. 50-56.

15. Malkina-Pykh IG. extreme situations. - M., 2005. - S. 960.

16. Post-traumatic stress disorder / Ed. T.B. Dmitrieva. - M., 2005. - S. 204.

17. Psychiatry: A guide for doctors / Ed. A.S. Tiganova. - M., 2012. - V. 2. - S. 896.

18. Psychiatry of wars and catastrophes: a guide for doctors / Ed. VC. Shamreya - St. Petersburg, 2013. - P. 194.

19. Psychology of post-traumatic stress / Ed. N.V. Tarabrina. - M., 2007. - S. 208.

20. Guide to psychiatry / Ed. A.S. Tiganova. -M., 1999. - T. 2. - S. 784.

21. Sidorov P.I. Mental health among veterans of the Afghan war. - Arkhangelsk, 1999. - S. 384.

22. Smulevich A.B. Depression in somatic and mental illnesses. - M. 2007. - S. 432.

23. Snedkov E.V. // Journal. nevrol. and a psychiatrist. them. S.S. Korsakov. - 2009. - No. 12. - S. 8-12.

24. Tarabrina N.V., Lazebnaya E.O. // Psych. magazine - 1992. - T. 13, No. 2. - S. 14-29.

25. Tarabrina N.V. Workshop on the psychology of post-traumatic stress. - SPb., 2001. - S. 272.

- SPb., 2001. - S. 272.

26. Tarabrina N.V. Psychology of post-traumatic stress: an integrative approach: Abstract of the thesis. dis. ... Dr. psikhol. Sciences. - SPb., 2008.

27. Traumatic stress. Etiology. Pathogenesis. Diagnostics. Psychotherapy / Ed. S.L. Solovieva, S.V. Chermya-nina. - St. Petersburg, 2011. - P. 152.

28. Khokhlov L.K. // Soc. and wedge. psychiatry. - 1998. - No. 2. -S. 116-122.

29. Tsirkin S.Yu. Analytical psychopathology. - M., 2012. -S. 288.

30. Tsutsieva Zh. Ch. Psychology of post-traumatic stress disorder in children, victims of terrorist acts: Abstract of the thesis. dis. ... Dr. psikhol. Sciences. - St. Petersburg, 2010.

31. Shadrina I.V., Pirogova M.Yu., Pugachev A.N. Vseros. scientific-practical. conf. "Mental health of the population as the basis of Russia's national security". - Kazan, 2012. -S. 262-100.

32. Effective therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder / Ed. Edna B. Foa, Terence M. Keane, Matthew J. Friedman. - M., 2005. - P. 467.

Friedman. - M., 2005. - P. 467.

F

Russian Psychiatric Journal No. 1, 2014

67

How to learn to live without stress and cope with burnout - RBC Pro 9 online course0001

Pro Project partner

TV channel

Newspaper

Pro

Investments

RBC+

New economy

Trends

Real estate

Sport

Style

National projects

City

Crypto

Debating club

Research

Credit ratings

Franchises

Conferences

Special projects St. Petersburg

Petersburg

Conferences St. Petersburg

Special projects

Checking counterparties

RBC Library

Podcasts

ESG index

Politics

Economy

Business

Technology and media

Finance

RBC CompanyRBC Life

Soft skills

About 90% of people give the advice “not to worry” in a stressful situation, but in practice this rarely works. Okay, there are other ways to prevent stress and burnout. Suitable for those who want to get more pleasure from life and work.

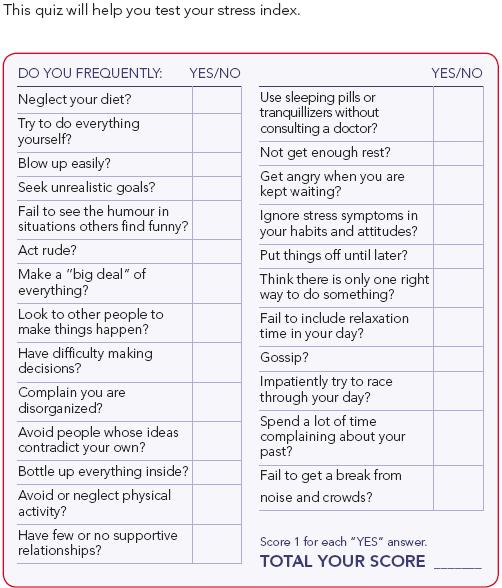

- Understand what causes stress and what level of stress you are currently experiencing

- Learn about the causes and signs of burnout,

- You will be able to support yourself in a difficult situation

The course is based on Russian and foreign research, self-support tools and stress management techniques from leading business coaches and coaches. You will learn how to manage your condition, get acquainted with various supportive exercises, self-regulation practices and coaching. After the intensive, you will have tools with which you can maintain work life balance and prevent burnout in the future.

You will learn how to manage your condition, get acquainted with various supportive exercises, self-regulation practices and coaching. After the intensive, you will have tools with which you can maintain work life balance and prevent burnout in the future.

Program

- Where does stress come from

- Causes and symptoms of burnout at work

- Helping ourselves in the moment: self-regulation practices

- How to relax during the day, at night, on weekends

- Getting ahead of the curve: self-coaching

- Five Flexible Habits for Workaholics

- Wrapping Up: How to Balance and Make Feeling Good Normal

How is the training going?

The intensive is available in two formats - you can get all the materials by email or go through the program with a Telegram bot. You can start learning at a convenient time.

Who will benefit from this intensive?

Entrepreneurs, managers and all those who want to be less irritated and get more pleasure from life and work.