Emdr therapy reviews

What the Heck Is EMDR Therapy? Can It Really Help Me?

Providing EMDR therapy is my ultimate passion. The often quick relief EMDR can provide clients has become my life's purpose. People often ask me how I got into EMDR. I’ve had my share of very difficult experiences in life. I grew up with a speech impediment and was bullied constantly in school as a child. In high school, I was also chronically teased because of acne, frequently called pizza-face. In around 2013, I noticed that this bullying affected my self-esteem, my sleep, appetite, well-being, and got in the way of my relationships. I finally went to an EMDR therapist.

Long story short, my experience receiving EMDR completely changed my life. Those past experiences don't bother me at all anymore (I guess this is why I can write about them publicly). In fact, I know how much wiser and stronger I've grown from these past struggles. It was intensely cathartic, emotionally draining, challenging, yet relieving and empowering.

After therapy, I knew I had to learn EMDR myself so I could help others effectively and efficiently.

The below represents the culmination of seven years of studying, writing about, and practicing EMDR. I am now fully certified in EMDR and train EMDR therapists as an EMDR Consultant. In the next years, my main purpose will be writing about, conducting, and teaching EMDR therapy.

What is EMDR Therapy?

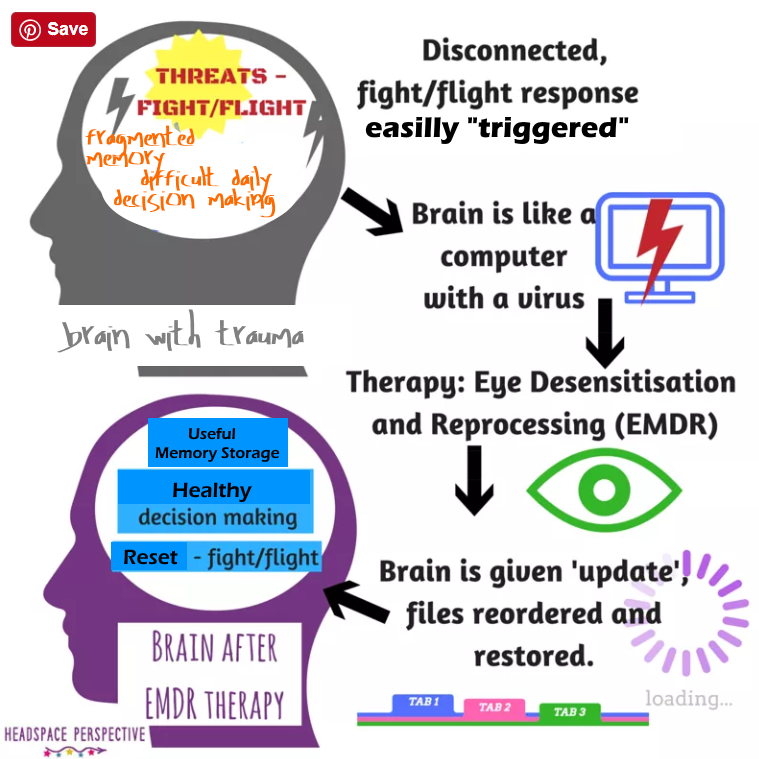

EMDR is not a traditional talk-therapy like most other psychotherapies; it's more of a mindfulness-based therapy, but that's not the full story. EMDR stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. You may have heard of EMDR through other therapists, friends, doctors, or even seen it featured in movies or television shows. It is an empirically supported (well-researched), and structured model of psychotherapeutic treatment that involves working with memories, body sensations, core-self beliefs, and emotions to eliminate the residential emotional, somatic, and cognitive remnants of painful past experiences.

Whereas a dentist would fill a cavity, or a surgeon would heal your injured wrist, EMDR is a form of emotional surgery to heal emotional wounds to help you "get past your past." Stay tuned below for the "pro-tips for clients" section if you want EMDR therapy for yourself.

Source: Pixabay / No Attribution Required

How Does EMDR Work?

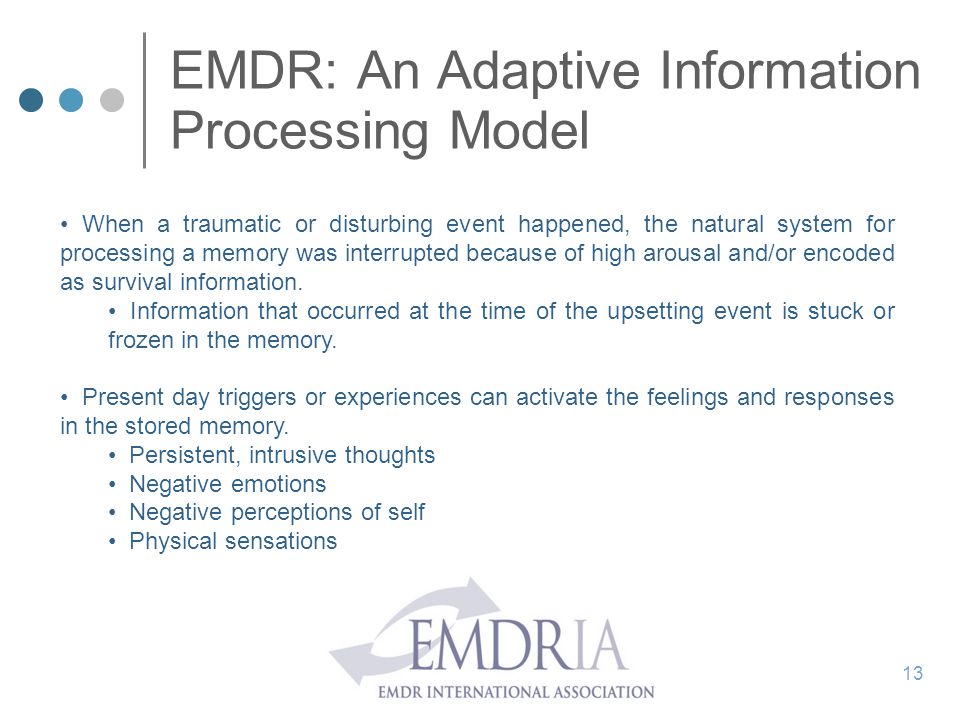

EMDR therapy is based on the adaptive information processing (AIP) model, which points to the strength-based notion that our minds have a natural capacity to process what happens to us in a healthy and adaptive way. However, significantly stressful experiences can overwhelm the brain’s natural processing and healing capacity. When the information related to a particularly stressful occurrence is ineffectually processed, the initial perceptions can be stored essentially as they were originally encoded, along with any distorted thoughts, images, sensations, or perceptions experienced when it happened (Shapiro, 2007). Thus, in EMDR, the culprit fueling mental health issues is unprocessed, inadequately digested memories stored in the brain and body. EMDR works by stimulating the brain in ways that lead it to process unprocessed or unhealed memories, leading to a natural restoration and adaptive resolution, decreased emotional charge (desensitization, or the “D” of EMDR), and linkage to positive memory networks (reprocessing, or the “R” of EMDR). EMDR helps people address and work through those memories, sensations, and emotions and resume normal, adaptive, and healthy processing. An experience that may have triggered a negative response may no longer affect them the way it used to after EMDR treatment. Difficult experiences will likely become less upsetting.

EMDR works by stimulating the brain in ways that lead it to process unprocessed or unhealed memories, leading to a natural restoration and adaptive resolution, decreased emotional charge (desensitization, or the “D” of EMDR), and linkage to positive memory networks (reprocessing, or the “R” of EMDR). EMDR helps people address and work through those memories, sensations, and emotions and resume normal, adaptive, and healthy processing. An experience that may have triggered a negative response may no longer affect them the way it used to after EMDR treatment. Difficult experiences will likely become less upsetting.

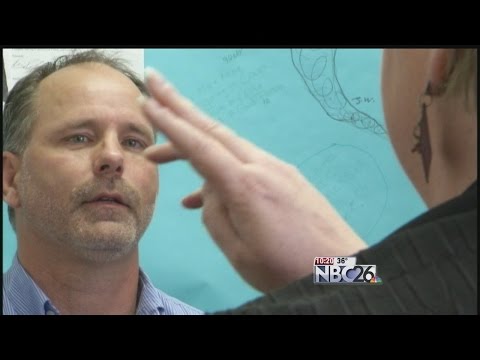

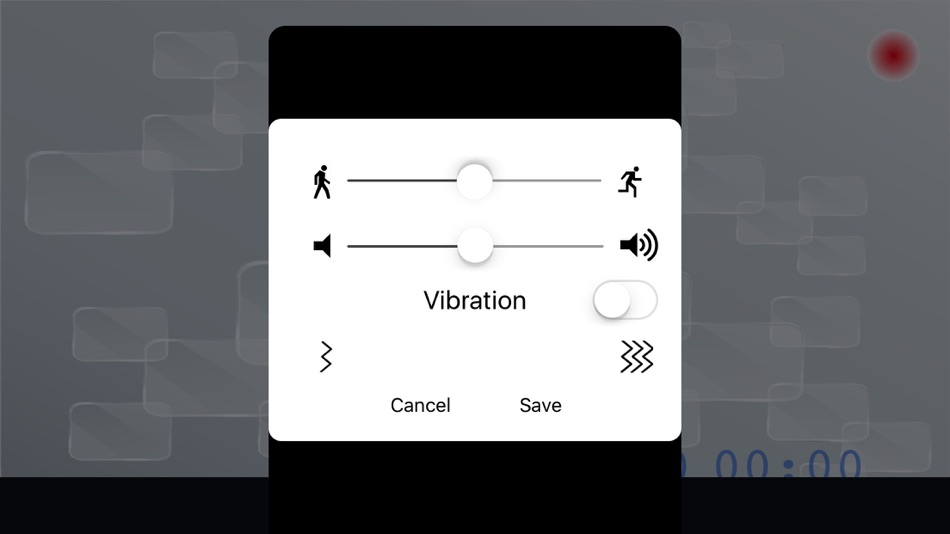

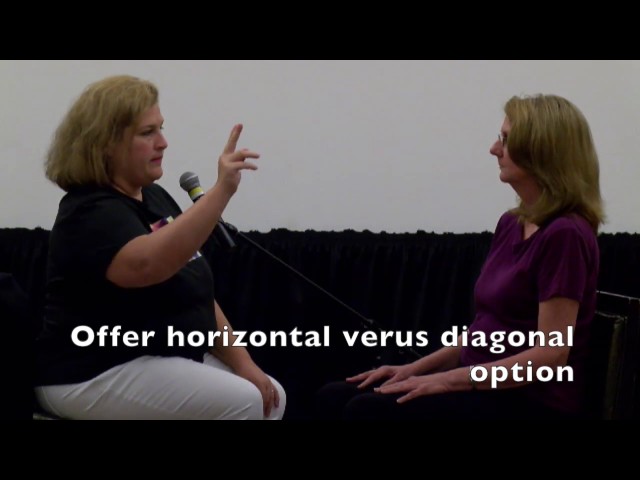

EMDR appears to have similar effects of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in which the mind and body integrates information during sleep. Much like in REM, during EMDR your brain will go wherever it needs to go to heal. EMDR uses dual stimulation to help clients process difficult memories. Using the light bar, clients track the blue lights left and right with their eyes. Clients hold hand buzzers that send gentle oscillating vibrations to the hands.

Clients hold hand buzzers that send gentle oscillating vibrations to the hands.

What's the Story Behind EMDR Therapy and Its Creation?

EMDR began as a trauma treatment meant to reduce symptoms such as hyper-vigilance, intrusive memories, and related disturbances for returning soldiers from the Vietnam war and women who had been raped. It achieved timely results in its original clinical trials in the late 1980s that withstood six-month follow-ups (Shapiro, 1989). It was originally called eye movement desensitization (EMD) until 1990, when the “R,” which stands for reprocessing, was added to convert EMD into EMDR, the comprehensive psychotherapy treatment approach it has become.

Francine Shapiro, creator of EMDR, transformed EMD from its initial conceptualization as a basic trauma symptom desensitization to a more integrative information processing paradigm now known as EMDR. EMDR is now used regularly by myriad clinicians to evoke positive affect and profound shifts in core-beliefs and related behaviors, as opposed to merely symptom alleviation.

Now, after 32 years of research progress and clinical development, EMDR therapists treat a variety of mental health issues and adverse life experiences (Shapiro, 2012). Shapiro (2017) also asserted that EMDR can work on issues many clinicians have come to view as intractable, such as personality disorders, by reprocessing the memories underlying the present dysfunction.

What Can You Expect During an EMDR Session?

EMDR sessions may be longer than standard therapy sessions: 50-180 minutes. I often check in with my clients to identify a specific problem and related memories it's based on to focus on. The therapist will ask you to recall the details of a disturbing experience, such as sights, sounds, sensations, thoughts, and emotions. Then, you'd be guided through several sets of dual stimulation through eye movements via light bar, alternating audio stimulation, or oscillating vibrations in your hands via hand buzzers.

I would ask you to focus on a certain aspect of the disturbing event and just let your mind float as it focuses on how the distance is stored in your body and mind. Dual stimulation would continue until the thoughts and beliefs about yourself become less disturbing and more positive, similar to how a physical cut heals with time. A client might start with, “I was helpless.” And end with, “I am a strong survivor.” During sessions of EMDR, clients may experience strong images, sensations, and emotions related to their disturbing memories, but most clients report a significant reduction in the intensity of the disturbance.

Dual stimulation would continue until the thoughts and beliefs about yourself become less disturbing and more positive, similar to how a physical cut heals with time. A client might start with, “I was helpless.” And end with, “I am a strong survivor.” During sessions of EMDR, clients may experience strong images, sensations, and emotions related to their disturbing memories, but most clients report a significant reduction in the intensity of the disturbance.

How Many EMDR Sessions Will it Take to Get Results?

Like most other psychotherapy approaches, EMDR should produce results in one or more sessions. The type of problem, severity and amount of trauma, and life circumstances are factors that may affect how many treatment sessions would be required. In my practice, clients may choose to use only EMDR as a primary source of treatment, or to integrate EMDR into their regular sessions of talk therapy.

Is EMDR Right for You?

I tend to tell my clients that all roads may lead to Rome, but many factors can affect which path is the right one for you. While EMDR has had such a positive impact on many of my clients, it may not be for everyone.

While EMDR has had such a positive impact on many of my clients, it may not be for everyone.

Often, your EMDR therapist might recommend meeting for one or more sessions to understand the source and nature of the issue before deciding to use EMDR as a treatment. During those sessions, they'll provide more information on EMDR, answer questions, and explain the process. Then, you and your therapist will decide mutually if EMDR is the right approach to address the specific problems that led you to treatment.

Yeah, But Does EMDR Actually Work?

According to over 20+ controlled studies exploring the effects of EMDR, yes EMDR does work. Studies show that EMDR therapy effectively eliminates or decreases symptoms of many mental health issues in the majority of those who received it. Clients reported improvement in related symptoms such as anxiety.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) have identified EMDR as a treatment that is effective for post-traumatic stress and other issues too. EMDR is also found effective by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, the Israeli National Council for Mental Health, the United Kingdom Department of Health, and many other governmental and health agencies over the world. Other research has also indicated that EMDR is a rapid and effective treatment. For more information on these studies, please visit the EMDR International Association’s website.

EMDR is also found effective by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, the Israeli National Council for Mental Health, the United Kingdom Department of Health, and many other governmental and health agencies over the world. Other research has also indicated that EMDR is a rapid and effective treatment. For more information on these studies, please visit the EMDR International Association’s website.

Aside from the research, here's Jameela Jamil's perspective from Russell Brand's podcast.

What Kind of Problems Can EMDR Treat?

EMDR is established as a well-researched and effective treatment approach for not only post-traumatic stress, but many mental health issues like anxiety, depression, poor job performance, sexual dysfunction, low self-esteem, among others. Therapists have also reported significant success in treating pain disorders, panic attacks, sexual and physical abuse, body dysmorphic issues, PTSD, trauma, performance anxiety, stress management, eating disorders, phobias, disturbing memories, dissociative disorders, personality disorders, addictions, and complicated grief.

Pro-tips for Prospective EMDR Clients:

It's a lot like putting a cast on a broken bone: parts of the process will feel very uncomfortable, unpleasant, and downright painful. I know it takes courage to trust the process. Prepare to feel emotionally drained after sessions. Don't schedule important tasks like job interviews after sessions. Prepare an after-therapy playlist and give yourself time to recharge and regroup. What helps you relax? Netflix? Exercise? Family time? Try to schedule those when possible after sessions.

Also, when you have a therapist in mind, consider requesting a free 10-15 minute phone consultation to ensure it feels like the right fit for you. EMDR works best when you feel safe, listened to, and supported by your EMDR therapist. Here's a 10-minute summary of more information and here's a free sample of a full EMDR session with Dr. Jaime Marich. I also recommend seeing an EMDRIA-certified therapist.

Why Is It Important to Go With a Certified EMDR Therapist?

A certified therapist has met a high standard of quality of training and experience in EMDR. The certification process requires many hours of supervision, training, and delivery of EMDR. It’s important to have a therapist with strong knowledge and training, especially given how important it is for you to heal some of the most difficult experiences in your life.

The certification process requires many hours of supervision, training, and delivery of EMDR. It’s important to have a therapist with strong knowledge and training, especially given how important it is for you to heal some of the most difficult experiences in your life.

This post is not meant to substitute for treatment with a qualified professional. If you’re looking for an EMDR therapist, I recommend checking the EMDR International Association (EMDRIA) website to ensure the therapist is certified (ideally), or minimally, was trained by an approved EMDR training provider.

To find a therapist near you, you can also visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.

How It Works, Benefits, Uses, and Side Effects

Developed by trauma therapists, EMDR helps your brain process and release traumatic memories in an unusual way — through your eye movements.

If you’ve experienced trauma, you’ll know just how much hold it can have over you. Intense dreams, flashbacks, and anxiety-induced isolation can bring your daily life to a halt. Sometimes, it can be a challenge to leave your home at all.

Sometimes, it can be a challenge to leave your home at all.

While traditional talk therapy and medications are the main treatments for post-traumatic stress, you might be wondering what other options are out there.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy was developed by Dr. Francine Shapiro in 1987 to treat post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This therapy uses eye movements (or sometimes rhythmic tapping) to change the way a memory is stored in the brain, allowing you to process it.

This therapy aims to help you work through painful memories with your body’s natural functions to recover from the effects of trauma.

EMDR therapy is considered a new, nontraditional form of psychotherapy. Therapists mostly use it to treat PTSD or trauma responses.

This therapy is based on the theory that traumatic events aren’t properly processed in the brain when they happen. This is why they continue to affect us — with nightmares, flashbacks, and feelings of the trauma happening again — long after the actual trauma is over.

When something reminds you of the trauma, your brain and body react as though it’s happening again. The brain isn’t able to tell the difference between the past and the present.

This is where EMDR comes in. The idea, known as the adaptive information processing model, is that you can “reprocess” a disturbing memory to help you move past it.

This therapy aims to change the way that the traumatic memories are stored in your brain. Once your brain properly processes the memory, you should be able to remember the traumatic events without experiencing the intense, emotional reactions that characterize post-traumatic stress.

During an EMDR therapy session, your therapist will ask you to briefly focus on a trauma memory. Then, they’ll instruct you to perform side-to-side eye movements while thinking of the memory. This engages both sides of your brain and is termed bilateral stimulation.

If you have visual processing issues, your therapist may use rhythmic tapping on both of your hands or play audio tones directed towards both ears.

One theory behind how EMDR works is that it helps the two sides of the brain to communicate with one another — the left side, which specializes in logic and reason, and the right side, which specializes in emotion.

Experts don’t know exactly how EMDR works. Ongoing investigations point out that it’s a complex form of therapy and likely has many mechanisms of action.

A review of 87 studies on EMDR found that two theories held the most promise: the working memory theory and the physiological changes theory.

Working memory theory

According to this theory, EMDR works through competition between where the brain stores information on sight and sound and where it processes working memory.

In this theory, recalling a memory at the same time your eyes are moving back and forth forces your brain to split its resources. You can’t dedicate all of your focus to memory recall because you’re also focusing on visual stimulation.

This split-focus can make any disturbing images you recall less vivid, and you may feel comfortably distanced from them. In this way, you might feel the emotional impact of the memories less strongly.

In this way, you might feel the emotional impact of the memories less strongly.

The bilateral brain stimulation might also help you feel more relaxed. As the memories grow less and less vivid, your brain might start to associate the memory recall with relaxation rather than emotional shock, which results in desensitization.

Physiological changes theory

Some researchers have found that performing eye movements in EMDR can invoke physiological changes in your body — a lowered heart rate, slower breathing, and decreased skin conductance — all of which are markers of relaxation.

This suggests that something about bilateral eye movements can alter how your nervous system is responding, allowing you to move away from an anxious fight, flight, or freeze response and toward nervous system regulation.

Other theories

Other theories about the way EMDR therapy works include:

- Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep phase replication. Back-and-forth eye movements may help the brain consolidate memories in the same way it does during REM sleep.

- Thalmo-cortical binding. Eye movements may directly impact a brain region called the thalamus, which may cause a cascade of cognitive processes that allow greater control over emotional distress.

- Structural brain differences. Structural and functional brain differences may exist in people who respond well to EMDR therapy.

With EMDR, you’ll usually have one or two sessions per week, about 6 to 12 sessions in total. You may require more or fewer sessions depending on your individual response to therapy.

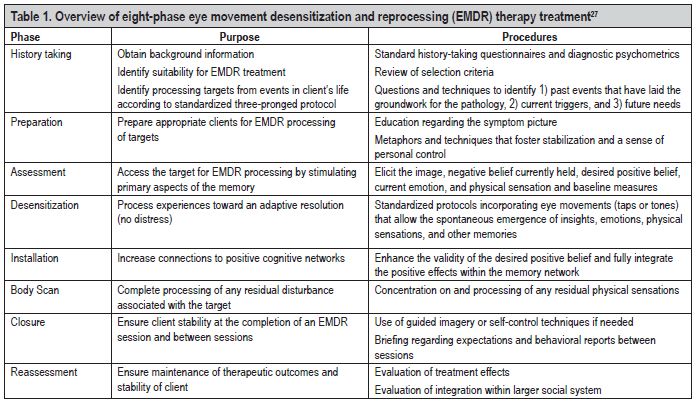

There are eight phases to EMDR therapy. Here’s what to expect:

Phase 1: History taking

First, you’ll work with your therapist to develop a treatment plan and treatment goals. This might include talking about your history, what emotional triggers and symptoms you experience, and what you’d like to achieve from therapy.

Your therapist might also determine whether you’d benefit from therapies or treatments alongside EMDR.

Phase 2: Preparation

Your therapist will then walk you through the therapeutic process, explain how EMDR works, and answer any questions.

EMDR therapy often takes multiple sessions to see progress. Your therapist can help you develop coping methods to help you manage your emotions both during and between sessions. This can include stress reduction techniques, such as breathing exercises and resourcing techniques.

Phase 3: Assessing the target memory

The goal of phase 3 is to identify and evaluate the memory causing your emotional distress.

Imagery, cognition, affect, and body sensation related to the memory are all assessed on diagnostic scales. Your therapist will use this as a starting point to track your progression through the EMDR treatments.

Phase 4–7: Treatment (desensitization, reaction, installation, closure)

Phase 4 marks the beginning of the memory desensitization process.

During your session, you’ll be asked to recall parts of a distressing memory. As you do this, your therapist will cue you to perform specific eye movements.

As you do this, your therapist will cue you to perform specific eye movements.

Once you’ve finished recalling the memory or feeling, you may be asked about the thoughts, feelings, and reactions you experienced during the recall.

Noting these responses is another means of helping track the progress of your EMDR therapy. The goal is to “install” improved emotional responses and positive beliefs within each session.

Remember, your mental health team has your best interests in mind at all times during your therapy session. If you experience distress, your therapist can help you work through those feelings and come back to the present.

At the end of your session, your therapist will determine whether the memory was fully reprocessed based on your responses. If the reprocessing is incomplete, they’ll do a resource or stress-reduction exercise with you in order to ensure that you feel OK before ending the session.

They’ll also review which coping strategies you can use to manage your emotions and keep yourself safe until the next session. Not all memories can be processed in one session.

Not all memories can be processed in one session.

Phase 8: Re-evaluation

At the end of each therapy session, both you and your therapist will evaluate the effects of the treatments, what memories have been uncovered, and which memories to target next time.

At the end of your therapy program, after you’ve targeted all the memories you’ve wished to, your therapist will complete a Future Template. In this exercise, they’ll use the bilateral stimulation again as you walk through an imagined future scenario of handling any previously triggering situations.

While the exact mechanisms behind EMDR remain up for debate, this therapy is recognized as an effective treatment by a number of national and international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

A 2018 review provides supportive evidence for the mechanisms behind EMDR, and other research continues to support this therapy’s effectiveness.

In 2019, a narrative review looked into the results of seven randomized controlled trials that involved early EMDR interventions. The researchers concluded that EMDR early interventions significantly reduced symptoms of traumatic stress and prevented symptoms from becoming worse.

The researchers concluded that EMDR early interventions significantly reduced symptoms of traumatic stress and prevented symptoms from becoming worse.

Other review studies have also found positive results from EMDR therapy:

- A 2018 review, conducted using eight databases of current studies, found that EMDR improved PTSD symptoms and was more effective compared to some traditional trauma therapies. However, they noted that much of the current evidence relies on small sample sizes.

- A 2018 review focused on 15 studies involving the use of EMDR therapy for children with PTSD. Researchers found that all studies in the review showed reduced PTSD symptoms, as well as other trauma-related symptoms, in children.

- A 2017 review looked at how EMDR therapy could impact conditions outside of PTSD. The results showed that EMDR therapy was a promising option for trauma-related symptoms in psychotic, affective, and chronic pain conditions.

- A 2017 review suggested that, though the research is currently limited, EMDR could have potential as a treatment for depression.

Most forms of therapy can have side effects. These secondary reactions can range from mild to severe, even with EMDR therapy.

Before you start an EMDR program, a mental health professional may warn you about potential side effects, such as:

- strong emotional fluctuations

- increased recall of traumatic or distressing memories

- vivid, intense dreams

- feelings of vulnerability

- lightheadedness

- physical stress responses (nausea, headache)

Part of your EMDR therapy plan will may include developing ways to manage these challenges if they arise.

Your healthcare team can recommend focus and relaxation methods or prescribe medications to help manage symptoms during treatment.

Past memories can do far more than just create feelings of sadness. If you’ve experienced trauma, these memories can impair your daily functioning.

Sometimes memories are so painful that they “freeze” you in that moment. You’re unable to get out, and it may feel easier to avoid those thoughts completely.

When this happens, people, places, and events, continue to bring out the emotions of trauma long after it’s passed.

EMDR therapy can help you break the freeze cycle by allowing your brain to process memories in a less painful way.

EMDR can be an emotional process, but you’re never alone. If you’re considering self-harm or suicide, help is available right now:

- Call a crisis hotline, such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255.

- Text HOME to the Crisis Text Line at 741741.

To learn more about EMDR or to access online support networks, publications, therapist finders, and other resources, visit The EMDR International Association (EMDRIA).

EMDR THERAPY: A Review of Development and Mechanisms of Action

Udy Oren, Roger Solomon

This article presents the history and development of EMDR from the original discovery of Dr. Francine Shapiro in 1987 to current results, as well as future directions for research and clinical practice. . EMDR is an integral psychotherapy that considers dysfunctionally stored memories as a core element in the development of psychopathology.

. EMDR is an integral psychotherapy that considers dysfunctionally stored memories as a core element in the development of psychopathology.

Key words: psychotherapy method, EMDR, eye movement desensitization and processing, effective psychotherapy.

Eye Movement Densitization and Processing (EMDR) is a therapeutic approach based on the Adaptive Information Processing (API) model. From the point of view of this integrative psychotherapeutic approach, dysfunctionally stored memories are considered to be the primary basis of clinical pathology. Processing these memories and integrating them into larger adaptive networks of memories allows them to be transformed and the system to function again.

Over the past 25 years, enough clinical research has been conducted on EMDR therapy to lead to widespread acceptance of this approach as an effective treatment for psychic trauma. The history of therapy, the API model, clinical application and elements of the procedure itself are described in various literature (European EMDR Association: http://www. emdr-europe.org/), which also describes studies confirming two main theories explaining the mechanisms of action of bilateral stimulation (BLS) used during EMDR therapy.

emdr-europe.org/), which also describes studies confirming two main theories explaining the mechanisms of action of bilateral stimulation (BLS) used during EMDR therapy.

EMDR is an integrative psychotherapeutic approach whose procedural elements fit well with most other types of psychotherapy (F. Shapiro, 2001, 2002). The therapy is based on the API model, which emphasizes the role of our brain's information processing system in the development of both healthy human functioning and pathology. Within the IPA model, insufficiently processed memories of uncomfortable or traumatic experiences are considered as the primary source of any psychopathology not caused by organic disorders. The processing of these memories leads to a resolution of the problem by rebuilding the system and assimilating the memory data into larger adaptive memory networks. EMDR is an 8-phase therapy that includes a three-part protocol focusing on:

- memories behind current problems;

– situations in the present and triggers that need to be dealt with separately in order to bring the client into a stable state of psychological health;

- as well as the integration of positive memory scripts for more adaptive behavior in the future.

One of the distinguishing features of EMDR is the use of bilateral stimulation, in particular side-to-side eye movements, alternating knee tapping, or alternating auditory stimulation, using standardized procedures and protocols to work with all aspects of the target memory network.

History of occurrence.

The history of EMDR began in 1987 when F. Shapiro discovered the effects of eye movements on disturbing memories. Based on this, she developed a therapy protocol she called Eye Movement Desensitization (EMD). Since initially F. Shapiro adhered to behavioral views, she first decided that the effect of eye movements was similar to systematic desensitization, and decided that it was based on the body's natural relaxation reaction.

She also suggested that the EMD process is related to the phenomenon of REM sleep and its effects on humans.

Shapiro's first studies were randomized clinical trials and showed promising results in the treatment of victims of sexual violence and war veterans (Shapiro, 1989).

Shapiro continued to develop and improve EMD procedures beyond the behavioral paradigm and in 1991 changed the name of the therapy to EMDR. The decision to add the word "processing" was due to the realization that desensitization is only one of the results of therapy, in fact, has a deeper effect, which can be better understood from the theory of information processing.

Early 1990s EMDR is experiencing a period of rapid growth and, at the same time, fierce discussions. The support of Joseph Wolpe, author of the method of systematic desensitization, as well as the publication of the results of several studies (Marquis, 1991; Wolpe & Abrams, 1991) led to the assertion that EMDR is a very promising form of psychotherapy. On the other hand, opponents of EMDR questioned the role of eye movements themselves (Lohr et al., 1992) and saw no scientific reason to add them to what they considered to be a type of exposure therapy (McNally, 1999). This criticism was recognized as erroneous (see review in Perkins & Rouanzoin, 2002), but the presence of opponents did not prevent F. Shapiro and her colleagues from continuing their work and conducting additional research. As empirical data was collected, EMDR therapy training programs began throughout the US, as well as in Europe, Australia, and Central and South America.

Shapiro and her colleagues from continuing their work and conducting additional research. As empirical data was collected, EMDR therapy training programs began throughout the US, as well as in Europe, Australia, and Central and South America.

The faculty of the EMDR Institute (www.emdr.com) have made a commitment from the very beginning to provide philanthropic education in hot spots and disaster areas around the world. At 1995 after the Oklahoma bombing, the EMDR community responded by creating the EMDR Humanitarian Assistance Program (EMDR-HAP).

The EMDR-HAP Program (www.emdrhap.org) and its affiliates around the world have continued to run hundreds of charity trainings in areas such as war-torn Bosnia, Nicaragua, Northern Ireland, Mexico City, post-quake Istanbul, Southeast Asia after the tsunami, in Israel, Palestine, Haiti after the earthquake, and at the request of many US government agencies.

Since 1995, when the first EMDR association (www.emdria.org) was founded in the USA, many other state and regional associations have appeared, including EMDR Asia (www. emdr-asia.org), EMDR Ibero-America (www.emdria.org). .emdriberoamerica.org), as well as the EMDR Europe Association (www.emdreurope.org), which has over 20 national associations and over 8,000 members (24,000 members in 2017. editor's note).

emdr-asia.org), EMDR Ibero-America (www.emdria.org). .emdriberoamerica.org), as well as the EMDR Europe Association (www.emdreurope.org), which has over 20 national associations and over 8,000 members (24,000 members in 2017. editor's note).

Due to the large amount of empirical research accumulated over the past 20 years, EMDR therapy is recognized as an effective therapy for trauma and is included in the clinical guidelines of many professional organizations and recommended by the ministries of health in different countries. In Europe, these include the Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Committee of the Department of Health Northern Ireland (CREST, 2003), the Guidance for the Delivery of Mental Health Services of the National Committee of the Netherlands (2003), the Study of the French State Institute of Medicine and Health (INSERM, 2004), UK Government Collaborating Center for Mental Health (NICE, 2005), Swedish Council for Technology Evaluation (2001), and UK Department of Health. In the United States, such organizations include the American Psychiatric Association (2004), the American Psychological Association (Chambles et al., 1998), State Institute of Mental Health (2007), and Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2004). EMDR is also included in the recommendations of the International Traumatic Stress Society (ISTSS) (Foa, Keane & Friedman, 2009) (http://www.emdreurope.org/info.asp?CategoryID=15).

In the United States, such organizations include the American Psychiatric Association (2004), the American Psychological Association (Chambles et al., 1998), State Institute of Mental Health (2007), and Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense (2004). EMDR is also included in the recommendations of the International Traumatic Stress Society (ISTSS) (Foa, Keane & Friedman, 2009) (http://www.emdreurope.org/info.asp?CategoryID=15).

Clinical studies.

Numerous practice guidelines and meta-analyses (Bisson & Andrew, 2007) show that EMDR has a therapeutic effect that is equal in strength and duration to that of the most extensively studied CBT techniques. The results of about 20 controlled studies have confirmed the effectiveness of EMDR therapy: for the treatment of PTSD; in the treatment of a wide range of disorders, including phobias (de Jongh, Ten Broeke & Renssen, 1999; de Jongh, van den Oord & Ten Broeke, 2002), panic disorder (Goldstein et al., 2000; Fernandez & Faretta, 2007), generalized anxiety disorder (Gauvreau & Bouchard, 2008), problems with self-control and self-esteem (Soberman, Greenwald & Rule, 2002), complicated cases of mourning (Solomon & Rando, 2007), dysmorphia (Brown, McGoldrick & Buchanan, 1997), olfactory disorder syndrome (McGoldrick, Begum & Brown, 2008), sexual dysfunction (Wernik, 1993), pedophilia (Ricci et al. , 2006), fear of failure (Barker & Barker, 2007), chronic pain (Grant & Threlfo, 2002), migraines (Marcus, 2008), and phantom pain in amputees (Schneider et al., 2008; Tinker & Wilson, 2006; de Roos, Veenstra et al., 2010). Most studies evaluate the effectiveness of EDMR with adults, however, there are several studies showing unusually positive results with children (Greenwald, 1998; Ahmad & SundelinWahlsten, 2008; Chemtob, Nakashima & Carlson, 2002; de Roos & de Jongh, 2008; Jaberghaderi, Greenwald, Rubin, Dolatabadim & Zand, 2004).

, 2006), fear of failure (Barker & Barker, 2007), chronic pain (Grant & Threlfo, 2002), migraines (Marcus, 2008), and phantom pain in amputees (Schneider et al., 2008; Tinker & Wilson, 2006; de Roos, Veenstra et al., 2010). Most studies evaluate the effectiveness of EDMR with adults, however, there are several studies showing unusually positive results with children (Greenwald, 1998; Ahmad & SundelinWahlsten, 2008; Chemtob, Nakashima & Carlson, 2002; de Roos & de Jongh, 2008; Jaberghaderi, Greenwald, Rubin, Dolatabadim & Zand, 2004).

When looking at the results of studies comparing the effectiveness of EMDR and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), it is important to remember that EMDR therapy does not require the 30 to 100 hours of homework that most forms of cognitive behavioral therapy do. However, with EMDR it is possible to achieve the same therapeutic effect with less psychological trauma to the client, as well as by working exclusively in sessions. As a result, the therapy is gentler, more tolerable by both clients and therapists (Arabia, Manca & Solomon, 2011), and is also able to produce positive results when sessions are carried out over several days in a row (Wesson & Gould, 2009).

One of the elements of EMDR, bilateral stimulation, has attracted the most attention from both clinicians and scientists. Several theories have been put forward to explain the action of BLS, but the mechanisms of action are still being studied. An early component analytic study assessing the role of eye movements produced conflicting results. However, critics have found a flaw in this study due to the use of an incorrectly selected patient group and insufficient duration of therapy (Chemtob, Tolin, van der Kolk & Pitman, 2000). On the other hand, specific physiological effects of eye movement during EMDR therapy sessions have been identified (Propper et al., 2007; Elofsson, von Scheele, Theorell & Sondergaard, 2008; Sack, Lempa, Steinmetz, Lamprecht & Hofmann, 2008; Wilson , Silver, Covi & Foster, 1996). Scientists believe that eye movements lead to an increase in parasympathetic activity and a decrease in psychophysiological arousal. Similar physiological results were obtained in a study where a patient experienced a decrease in pulse rate and galvanic skin reflex after one session of EMDR (Aubert-Khalfa, Roques & Blin, 2008).

Two theories enjoy the greatest support from scientists. One concerns the orienting reflex, which, in their opinion, is directly related to the processes that take place during REM sleep (Stickgold, 2002, 2008). This theory is also supported by those randomized studies in which it was found that eye movements improve the functioning of event memory (Christman, Garvey, Propper & Phaneuf, 2003), increase the flexibility of attention focus (Kuiken, Bears, Miall & Smith, 2002; Kuiken, Chudleigh & Racher, 2010) and enhance the ability to recognize true information (Parker & Dagnall, 2007; Parker, Relph & Dagnall, 2008; Parker, Buckley & Dagnall, 2009). The orienting reflex hypothesis has also been evaluated in studies showing decreased levels of arousal (MacCulloch & Feldman, 1996; Barrowcliff, Gray, MacCulloch, Freeman & MacCulloch, 2003; Barrowcliff, Gray, Freeman & MacCulloch, 2004; Schubert, Lee & Drummond, 2011).

The second dominant hypothesis is that eye movements and other forms of dual focus stimulation (such as tapping and auditory stimulation) disrupt the habitual functioning of short-term memory. Randomized trials of this theory show that eye movements reduce the saturation and/or emotional charge of memories and frightening images (Andrade, Kavanagh & Baddeley, 1997; Engelhard, van Uijen & van den Hout, 2010; Engelhard et al., 2011; Gunter & Bodner, 2008; Kavanagh, Freese, Andrade & May, 2001; Maxfield, Melnyk & Hayman, 2008; Sharpley, Montgomery & Scalzo, 1996; van den Hout, Muris, Salemink & Kindt, 2001; van den Hout et al., 2011). At the moment, it is not known when exactly the change in saturation and emotional charge occurs - before or after the decrease in physiological arousal, whether these two phenomena are closely related or whether they represent independent elements of the process (Sack et al., 2007, 2008a, b).

Randomized trials of this theory show that eye movements reduce the saturation and/or emotional charge of memories and frightening images (Andrade, Kavanagh & Baddeley, 1997; Engelhard, van Uijen & van den Hout, 2010; Engelhard et al., 2011; Gunter & Bodner, 2008; Kavanagh, Freese, Andrade & May, 2001; Maxfield, Melnyk & Hayman, 2008; Sharpley, Montgomery & Scalzo, 1996; van den Hout, Muris, Salemink & Kindt, 2001; van den Hout et al., 2011). At the moment, it is not known when exactly the change in saturation and emotional charge occurs - before or after the decrease in physiological arousal, whether these two phenomena are closely related or whether they represent independent elements of the process (Sack et al., 2007, 2008a, b).

Ten randomized trials support both hypotheses. Therefore, there is good reason to believe that both theories are correct and that both processes described contribute to the therapeutic effect of EMDR. All of these findings collectively tell us that while previous component analyzes have failed to confirm the importance of bilateral pacing for EMDR, there is little doubt that the next generation of component analyzes of diagnosed patients will add to our knowledge base—provided, of course, that they are done well. research work (F. Shapiro, 2001).

research work (F. Shapiro, 2001).

Model of adaptive information processing (API).

Behind the transformation of EMD into EMDR was primarily the API model, which is the theoretical basis for the entire clinical practice of EMDR (F. Shapiro, 1995, 2001). According to this model, networks of memories that store all previous experience are the basis for both human health and the emergence of pathology. New experience is an endless stream of conscious and unconscious elements of information that are processed by the brain with the help of an information processing system within these networks of memories. This system is inherently adaptive in that it is capable of using information to support human growth and development through learning when it functions normally. Relevant sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information is stored in memory networks, which in the future will be used to enable a person to adaptively respond to the world around him.

Apparently, some stressful negative events lead to an overload of the information processing system, as a result of which they cannot be assimilated adaptively. Such an event is stored in memory along with disturbing emotions, physical sensations and fears experienced at the time of the event. These situations can sometimes represent serious traumas, but more often they are everyday negative events that happen to people at home, in relationships, at school, at work, and so on, such as humiliation, rejection, and failure. In such situations, information regarding the negative event is stored in isolation from adaptive memory networks. Current situations in the present may trigger earlier memories, whereby the individual may experience some or all of the sensory, cognitive, emotional, and somatic aspects of events, resulting in maladaptive or symptomatic behavior.

Such an event is stored in memory along with disturbing emotions, physical sensations and fears experienced at the time of the event. These situations can sometimes represent serious traumas, but more often they are everyday negative events that happen to people at home, in relationships, at school, at work, and so on, such as humiliation, rejection, and failure. In such situations, information regarding the negative event is stored in isolation from adaptive memory networks. Current situations in the present may trigger earlier memories, whereby the individual may experience some or all of the sensory, cognitive, emotional, and somatic aspects of events, resulting in maladaptive or symptomatic behavior.

The API model considers negative beliefs, behaviors, and personality traits as a consequence of dysfunctionally stored memories (F. Shapiro, 2001). From this point of view, any negative self-belief (e.g., "I'm stupid"), any negative emotional reaction (e.g., fear in the presence of an authority figure), any negative somatic reaction (e. g., abdominal pain before an exam) are symptoms rather than the cause of current problems. The reason is considered to be memories of unprocessed events from the patient's life that are activated in the present. This view of psychological pathology is the main theoretical basis of EMDR therapy and helps the clinician understand the client, formulate a treatment plan, and select appropriate therapeutic interventions.

g., abdominal pain before an exam) are symptoms rather than the cause of current problems. The reason is considered to be memories of unprocessed events from the patient's life that are activated in the present. This view of psychological pathology is the main theoretical basis of EMDR therapy and helps the clinician understand the client, formulate a treatment plan, and select appropriate therapeutic interventions.

During an EMDR session, standardized procedures and protocols are used to access the memory associated with the current difficulty, which also uses brief bilateral stimulation (eye movements, tactile and auditory stimulation). Recordings of sessions (F. Shapiro, 2001, 2002; Shapiro & Forrest, 1997) show that processing mainly occurs due to the rapid establishment of intrapsychic connections between emotions, insights, sensations and memories that arise during the session, which change after each next set of bilateral stimulation. According to the API model, this process is seen as establishing a connection between the target memory and adaptive information, which allows the client to move forward, passing through the necessary stages of affect and awareness related to topics such as (1) the right degree of responsibility, (2) safety in present moment, and (3) the possibility of making choices in the future.

EMDR processing is understood as an inducement to the emergence of new associations and connections, which makes further learning possible and leads to the preservation of memories in a new, adaptive form. Once this has happened, the client can look at the disturbing event and at himself from a new, adaptive perspective. This new point of view does not carry the negative cognitions, affect and somatic sensations that were previously at the center of his maladaptive perception of this event. Consequently, the event ceases to have a negative impact on the client's personality, his worldview, as well as his emotional and somatic experience. This reworking, leading to new learning, is a central element of the EMDR model and therapy. The three-part protocol used in EMDR therapy works and recycles the positive experiences and new information/education needed to overcome any lack of knowledge or skills.

8-phase therapeutic approach.

EMDR Integrative Psychotherapy uses an 8-phase protocol to guide the therapist in dealing with current psychological difficulties stemming from past negative events.

Phase 1 - History taking. The therapist collects general psychological data, focusing on current strengths and difficulties, past events that are related to current problems, present situations that cause problems, and positive goals for the future.

Phase 2 - Preparation. The therapist prepares the client for reprocessing by establishing a therapeutic alliance, providing psychological preparation for the client's difficulties, as well as explaining the EMDR process, and teaching the client specific types of relaxation techniques to help the client maintain a "dual focus" during a series of reprocessing sessions.

Phase 3 – Evaluation. The therapist will help the client clarify the details of the target memory, including the central picture, current negative cognition, desired positive cognition, current emotions and physical sensations, and some basic scale measurements.

Phase 4 - Desensitization. The therapist follows the client in guiding the processing of a disturbing memory from a past or current target event. At a later stage, positive scenarios for future behavior are also processed. Processing includes changes in sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information. The purpose of this phase is to reduce the anxiety associated with the memory to the lowest possible level and to promote personal growth through gaining insight and new perspectives, resulting in a new sense of self and worldview.

At a later stage, positive scenarios for future behavior are also processed. Processing includes changes in sensory, cognitive, emotional and somatic information. The purpose of this phase is to reduce the anxiety associated with the memory to the lowest possible level and to promote personal growth through gaining insight and new perspectives, resulting in a new sense of self and worldview.

Phase 5 - Installation. The therapist helps the client identify the currently desired positive self-belief about the processed memory and reinforces it, facilitating the integration of the memory into adaptive memory networks.

Phase 6 - Body scan. The therapist helps the client to discover and process any residual somatic sensations, striving for a complete somatic resolution.

Phase 7 - Completion. The therapist gives the client feedback about the session and what to expect after the session is over. The client is asked to keep brief notes of psychological reactions between sessions. If necessary, the therapist may use relaxation techniques to help the client stabilize before the session ends.

If necessary, the therapist may use relaxation techniques to help the client stabilize before the session ends.

Phase 8 - Reassessment. The therapist evaluates the client at the start of the next session, paying special attention to the effect of the therapy and assessing what has happened between sessions. This step also includes a re-evaluation of the previously redesigned target to assess the persistence of the therapy effect, as well as to identify other aspects that potentially need further processing. The therapist uses this information to determine the next step(s) in the course of therapy.

Three-part protocol (past, present, future).

Upon completion of therapy planning (Phase 1) and preparation and stabilization (Phase 3), EMDR therapy includes a three-part protocol that addresses past, present, and future relevant memories/scripts. In this approach, the therapist helps the client identify the details of each memory/script (phase 3) and process it (phases 4, 5, 6). Based on the API model, the client is first asked to process past experiences (both earlier and more recent) related to current difficulties. Reprocessing then focuses on current situations that are causing maladaptive responses in the present (including negative thoughts, emotions, feelings, and behaviors). Once memories from the past and present have been processed, the client is asked to imagine adaptive behaviors that will be used as a memory script for the future. This is done in relation to each of the previously identified situations in the present that cause dysfunctional reactions. Then the scenarios, which include cognitive, somatic and behavioral information, are processed, which contributes to their integration into the adaptive network of memories. The client may then be asked to face a particular problematic situation and then provide the therapist with feedback that will help him decide whether to continue therapy.

Based on the API model, the client is first asked to process past experiences (both earlier and more recent) related to current difficulties. Reprocessing then focuses on current situations that are causing maladaptive responses in the present (including negative thoughts, emotions, feelings, and behaviors). Once memories from the past and present have been processed, the client is asked to imagine adaptive behaviors that will be used as a memory script for the future. This is done in relation to each of the previously identified situations in the present that cause dysfunctional reactions. Then the scenarios, which include cognitive, somatic and behavioral information, are processed, which contributes to their integration into the adaptive network of memories. The client may then be asked to face a particular problematic situation and then provide the therapist with feedback that will help him decide whether to continue therapy.

Mechanisms of action.

As with any form of psychotherapy, the neurophysiological nature of the effects of EMDR is currently unknown, but several mechanisms of action may contribute to the therapeutic effect. Scientists propose a range of possible mechanisms of action that distinguish EMDR from traditional CBT practices. One of these mechanisms concerns "suppression" (extinction) and "recovery" (reconsolidation). EMDR therapy proposes, among other mechanisms of action, the assimilation of adaptive information found in other memory networks that come into contact with the network containing the previously isolated anxiety event (Solomon & Shapiro, 2008). After the successful completion of therapy, it is assumed that the memory is no longer isolated, as it appears to be properly integrated into the larger memory network. This idea is quite consistent with recent neurobiological theories about memory retrieval (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004) who suggest that once a memory is accessed, it can become labile and then re-stored in an altered form. The process of EMDR associated with the attachment of new associations to previously isolated memory networks can indeed activate the recovery process.

Scientists propose a range of possible mechanisms of action that distinguish EMDR from traditional CBT practices. One of these mechanisms concerns "suppression" (extinction) and "recovery" (reconsolidation). EMDR therapy proposes, among other mechanisms of action, the assimilation of adaptive information found in other memory networks that come into contact with the network containing the previously isolated anxiety event (Solomon & Shapiro, 2008). After the successful completion of therapy, it is assumed that the memory is no longer isolated, as it appears to be properly integrated into the larger memory network. This idea is quite consistent with recent neurobiological theories about memory retrieval (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004) who suggest that once a memory is accessed, it can become labile and then re-stored in an altered form. The process of EMDR associated with the attachment of new associations to previously isolated memory networks can indeed activate the recovery process. Therefore, EMDR may have different mechanisms of action than the main mechanism of action of various types of exposure therapy, namely "repression" (Craske, 1999; Lee, Taylor & Drummond, 2006; Rogers & Silver, 2002). It is believed that "restoration" changes the original memory, and "stopping", in turn, creates a new memory that begins to compete with the old one.

Therefore, EMDR may have different mechanisms of action than the main mechanism of action of various types of exposure therapy, namely "repression" (Craske, 1999; Lee, Taylor & Drummond, 2006; Rogers & Silver, 2002). It is believed that "restoration" changes the original memory, and "stopping", in turn, creates a new memory that begins to compete with the old one.

During the evaluation phase of EMDR therapy, there are also additional mechanisms that help bring together the various fragments of memory. When undergoing exposure therapy, the client is asked to describe the memory in the most detailed way, while in EMDR therapy there are no such requirements. Rather, during the appraisal phase, the therapist helps the client isolate the negative memory image, identify the current negative belief and desired positive belief, associated emotions, and bodily sensations. Experience that has not been reworked enough can be stored in fragments (van der Kolk & Fisler, 1995). Therefore, the systematization of memory components as an element of the procedure stimulates the process of processing. This procedure activates memory networks containing other aspects of the negative experience, potentially enabling the client to reconnect parts of the experience, make sense of it, and facilitate the process of retaining the memory in narrative memory.

This procedure activates memory networks containing other aspects of the negative experience, potentially enabling the client to reconnect parts of the experience, make sense of it, and facilitate the process of retaining the memory in narrative memory.

Cognitive restructuring is another element of the procedure that can explain the effectiveness of EMDR. However, in traditional types of cognitive therapy, it is customary to identify some irrational belief about oneself (negative cognition), and then deliberately question it, restructure and reframe this belief, turning it into an adaptive belief about oneself (positive cognition) (Beck, Rush, Shaw & Emery, 1979). The assessment phase in EMDR differs from cognitive restructuring methods in that there is no deliberate attempt by the therapist to change or reframe the client's current belief. It is assumed that the belief will change spontaneously in the process of subsequent processing. However, from the point of view of the API, the preliminary formation of an association between negative cognition and more adaptive information that contradicts negative experiences can contribute to further processing, since it activates the corresponding adaptive networks.

The desensitization and installation phases have different mechanisms of action. One of the possible mechanisms of action is awareness. During the desensitization phase of EMDR, clients are instructed to "let whatever happens" and "just pay attention" to whatever comes up (F. Shapiro, 1989, 1995, 2001). This is quite consistent with the principles of mindfulness practice (Siegel, 2007). Instructions like this reduce excessive demands on themselves and perhaps help clients to observe without judgment what they are feeling and thinking. Research confirms that the adoption of the paradigm that sees negative thoughts and feelings as transient mental phenomena rather than as aspects of the personality (Teasdale, 1997; Teasdale et al., 2002) has a beneficial therapeutic effect. However, while meditation techniques most often ask participants to return to their original focus of attention (Tzan-Fu, Ching-Kuan & Nien-Mu, 2004), in EMDR therapy clients are asked to simply "notice" various associations as they occur.

Perceived mastery may be another important procedural element that makes EMDR an effective therapy. Whereas exposure techniques require concentration and do not encourage distraction from the incident in order to prevent avoidance, EMDR therapy uses only momentary attention to the various associations that occur within the client during sets of eye movements. Therefore, during EMDR, clients may experience an increase in the sense of being able to switch between experiencing the event, paying attention to what is happening, and communicating the change to the therapist. The client's ability to use coping strategies more effectively can improve along with their ability to cope with stress, anxiety and depression in dangerous situations. (Bandura, 2004). From an API perspective, this sense of ability and efficiency is encoded in the brain as adaptive information available to connect with memory networks containing dysfunctionally stored information.

Finally, exposure therapy maintains a high level of anxiety by initially focusing on the disturbing event, as mentioned above, while the eye movements used in EMDR seem to increase parasympathetic arousal and reduce the intensity and emotionality of negative material, as well as to increase the flexibility of attention. It is possible that such effects allow information from other memory systems to connect to a target network that contains dysfunctionally stored information (Shapiro, 1995, 2001) leading to transformation and then retrieval of the memory (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004). Further clinical studies are required to explore these hypotheses and better understand the specific, side-effects, and interactive effects of different factors on EMDR performance.

It is possible that such effects allow information from other memory systems to connect to a target network that contains dysfunctionally stored information (Shapiro, 1995, 2001) leading to transformation and then retrieval of the memory (Cahill & McGaugh, 1998; Suzuki et al., 2004). Further clinical studies are required to explore these hypotheses and better understand the specific, side-effects, and interactive effects of different factors on EMDR performance.

Conclusions.

EMDR is one of the pioneering arts of psychotherapy. Primarily, this therapy is part of the evidence-based therapy group, which combines the clinical and scientific aspects of psychotherapy for decades after the establishment of recommendations for evidence-based treatments according to the Boulder Model (Fagan & Warden, 1996). Since the inception of EMDR, practitioners have always supported the development of clinical research, as evidenced by more than 30 randomized trials of trauma therapy. The API model forms the theoretical basis for EMDR, however, it is clear that the answers to the questions surrounding EMDR (and other therapies) lie in the human brain. As a result, more than ten studies have been devoted to the study of the neurobiological aspects of therapy, and their results indicate that psychotherapy and brain research should develop in tandem (Bossini, Fagiolini & Castrogiovanni, 2007; Pagani et al., 2007; Richardson et al. ., 2009).

As a result, more than ten studies have been devoted to the study of the neurobiological aspects of therapy, and their results indicate that psychotherapy and brain research should develop in tandem (Bossini, Fagiolini & Castrogiovanni, 2007; Pagani et al., 2007; Richardson et al. ., 2009).

EMDR is an integrative form of psychotherapy that includes elements that are compatible with a variety of approaches. The central place in therapy here is occupied by the body, however, the cognitive, emotional and behavioral aspects retain their importance. One of the most important advantages of EMDR is that it can also be used as a highly focused, short-term form of psychotherapy (in cases of single trauma: Shapiro, 1989; Jarero, Artigas & Luber, 2011; Kutz, Resnik & Dekel, 2008), and as a long-term, integrative, more widely applicable form of therapy (in cases of complex trauma, Korn, 2009). Along with positive psychology, EMDR is a form of humanistic therapy that believes in the client's inner resources and their ability to use those resources for personal growth. The working premise of EMDR is that the client heals himself with proper stimulation from the therapist, which leads to improved functioning of the internal information processing system (Shapiro, 1995, 2001). And finally, in all corners of the world, in dozens of countries, therapists of all cultures and professional orientations are successfully trained in EMDR. The very fact that EMDR has been successfully used in various cultures (Kim et al., 2010; Kavakcı, Kaptanog lu, Kug u & Dog an, 2010; Konuk et al., 2006; Uribe & Ramirez, 2006) indicates that EMDR makes a huge contribution to the development of the world of psychotherapy and to the well-being of mankind.

The working premise of EMDR is that the client heals himself with proper stimulation from the therapist, which leads to improved functioning of the internal information processing system (Shapiro, 1995, 2001). And finally, in all corners of the world, in dozens of countries, therapists of all cultures and professional orientations are successfully trained in EMDR. The very fact that EMDR has been successfully used in various cultures (Kim et al., 2010; Kavakcı, Kaptanog lu, Kug u & Dog an, 2010; Konuk et al., 2006; Uribe & Ramirez, 2006) indicates that EMDR makes a huge contribution to the development of the world of psychotherapy and to the well-being of mankind.

In summary, EMDR sees current problems as primarily related to dysfunctionally stored memories. There is direct work with past experience that has not been adequately processed and integrated into adaptive networks. EMDR is an evidence-based psychotherapeutic approach effective in trauma therapy. However, EMDR can be used to treat a wide range of disorders due to the fact that dysfunctionally stored memories are present in clients with all kinds of clinical diagnoses. (Mol et al., 2005; Obradovicˇı, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler & Boyce, 2010). The EMDR integrative psychotherapeutic approach uses an eight-phase, three-stage (past, present, future) protocol that aims to free the client from the influence of experience that lays the foundation for the current pathology, as well as embedding a wide variety of elements of experience and memories into a common system in order to lead the client to a state of mental health.

(Mol et al., 2005; Obradovicˇı, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler & Boyce, 2010). The EMDR integrative psychotherapeutic approach uses an eight-phase, three-stage (past, present, future) protocol that aims to free the client from the influence of experience that lays the foundation for the current pathology, as well as embedding a wide variety of elements of experience and memories into a common system in order to lead the client to a state of mental health.

Although the exact mechanisms behind these changes are unknown to us, a large number of randomized trials confirm that the eye movements used in EMDR correlate with the desensitization effect. Given the results of studies that show that eye movements per se lead to increased attentional flexibility and memory retrieval, it can be hypothesized that decreased arousal levels allow adaptive information from other memory networks to connect with the network that stores dysfunctionally stored information. This may lead to adaptive memory retrieval. However, as with other forms of psychotherapy, further brain research is needed to determine the exact biological basis for the therapeutic effect. Additional research is also needed to determine the neurobiological basis of eye movements and the interactive effects of various components of the EMDR therapy process. Given that homework is not used in EMDR therapy, daily therapy can easily validate the results of these studies, reducing the time frame that is usually required for other forms of therapy.

However, as with other forms of psychotherapy, further brain research is needed to determine the exact biological basis for the therapeutic effect. Additional research is also needed to determine the neurobiological basis of eye movements and the interactive effects of various components of the EMDR therapy process. Given that homework is not used in EMDR therapy, daily therapy can easily validate the results of these studies, reducing the time frame that is usually required for other forms of therapy.

Literature

1. Besser-Siegmund, K. EMDR in coaching / K. Besser-Siegmund, X Siegmund; per. with him N. Gust. - St. Petersburg: Werner Regen Publishing House, 2007. - 160 p.

2. Shapiro, F. Psychotherapy of emotional trauma using eye movements: basic principles, protocols and procedures /F. Shapiro; per. from English. A.S. Rigina - M .: Independent firm "Class" - 1998 - 496 p.

3. Perkins, B.R., & Rouanzoin, C.C. A critical evaluation of current views regarding eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Clarifying points of confusion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58 - 2002 - pp. 77–97.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58 - 2002 - pp. 77–97.

4. Shapiro, F. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press - 2001 - 450 p.

5. Shapiro, F. Paradigms, processing, and personality development. In F. Shapiro (Ed.), EMDR as an integrative psychotherapy approach: Experts of diverse orientations explore the paradigm prism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books - 2002 - pp. 3–26

6. Shapiro, F. EMDR, Adaptive Information Processing, and Case Conceptualization / F. Shapiro // Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, Volume 1, Number 2 – 22007 – pp. 68-87

EMDR method

EMDR Latvija

professional association of EMDR therapists

Description of the EMDR method

EMDR eye) is a new unique technique of psychotherapy, extremely effective in the treatment of emotional trauma. All psychotherapists world today, in addition to classical methods, it is used in working with those who have experienced emotional trauma, because with the help of EMDR can solve psychological problems much faster, than traditional forms of psychotherapy.

Discovery of the method:

The emergence of the EMDR technique is associated with random observation calming effects of spontaneously repetitive eye movements to bad thoughts.

EMDR was created by psychologist-psychotherapist Francine Shapiro in 1987. One day, while walking in the park, she noticed that the thoughts that had been troubling her suddenly vanished. Francine noted also, that if these thoughts are again called into the mind, they no longer have such a negative effect and do not seem so real as before. She noted that when disturbing thoughts, her eyes would spontaneously move rapidly side to side and up and down diagonally. Then disturbing thoughts disappeared, and when she deliberately tried remember them, then the negative charge inherent in these thoughts was significantly reduced.

Noticing this, Francine began to move her eyes intentionally, focusing on various unpleasant thoughts and memories. these thoughts also disappeared and lost their negative emotional coloring.

Shapiro asked her friends, colleagues and participants psychological seminars to do the same exercise. results were striking: the level of anxiety was reduced and people could more calmly and realistically perceive what bothered them.

This new psychotherapy technique was discovered by accident. In less than 20 years, Shapiro and her colleagues have specialized in more than 25,000 psychotherapists from various countries, which brought the method among the most rapidly spreading in around the world of psychotechnology.

Francine Shapiro now works at the Institute for Brain Research in Palo Alto (USA). In 2002 she was awarded the Sigmund Freud - the most important world award in the field psychotherapy.

How does EMDR work?

Each of us has an innate physiological mechanism information processing that keeps our mental health at the optimum level. Our natural inner information processing system is organized in such a way that that it allows her to restore mental health so much like how the body naturally recovers from injury. So, for example, if you cut your hand, then the forces of the body will focus on healing the wound. If something prevents such healing - some external object or repeated trauma - the wound begins to fester and causes pain. If the obstacle is removed, the healing will be completed.

So, for example, if you cut your hand, then the forces of the body will focus on healing the wound. If something prevents such healing - some external object or repeated trauma - the wound begins to fester and causes pain. If the obstacle is removed, the healing will be completed.

The balance of our natural processing system information at the neurophysiological level may be disturbed during trauma or stress arising in the course of our life. This blocks the natural tendency information processing system of the brain to provide state of mental health. As a result, there are various psychological problems psychological problems are the result of accumulated nervous system of negative traumatic information. key to psychological change is the ability perform the necessary information processing.

EMDR is an accelerated recycling method information. The technology is based on a natural process tracking eye movements that activate the internal mechanism processing of traumatic memories in the nervous system. Certain eye movements lead to involuntary connection to the innate physiological mechanism processing of traumatic information, which creates psychotherapeutic effect. As you transform traumatic information there is a concomitant change in thinking, behavior, emotions, sensations, visual images of a person. Metaphorically speaking, we can consider the recycling mechanism as a kind of process "digestion" or "metabolism" of information so that it could be used for healing and quality improvement human life.

Certain eye movements lead to involuntary connection to the innate physiological mechanism processing of traumatic information, which creates psychotherapeutic effect. As you transform traumatic information there is a concomitant change in thinking, behavior, emotions, sensations, visual images of a person. Metaphorically speaking, we can consider the recycling mechanism as a kind of process "digestion" or "metabolism" of information so that it could be used for healing and quality improvement human life.

Technique assisted EMDR trauma information becomes accessible, recyclable and adaptive allowed. Our negative emotions are processed to gradual weakening, while there is a kind of learning to help integrate these emotions and use them in the future.

The recycling process can take place using not only eye movements, but also with the help of other external stimuli, such as tapping the client's palm, flashes of light or auditory stimuli.

After just one session EMDR a person can recall the traumatic event in a more neutral way, without the occurrence of intense emotions.