Antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome

Antipsychotic Withdrawal Syndrome - Understanding the Hyperbolic Curve and Tapering Antipsychotic Treatment to Reduce the Risk of Relapse

We previously covered antidepressant withdrawal. Antipsychotic withdrawal can pose similar challenges. Despite the challenges and a serious risk of relapse, there are no clear guidelines on managing antipsychotic discontinuation and dose reduction. [Shimomura et al. 2020]

Most guidelines recommend continuous therapy after a first psychotic episode to prevent a recurrence; however, some studies have questioned this approach. [Wunderink et al 2013]; [Harrow et al 2017]

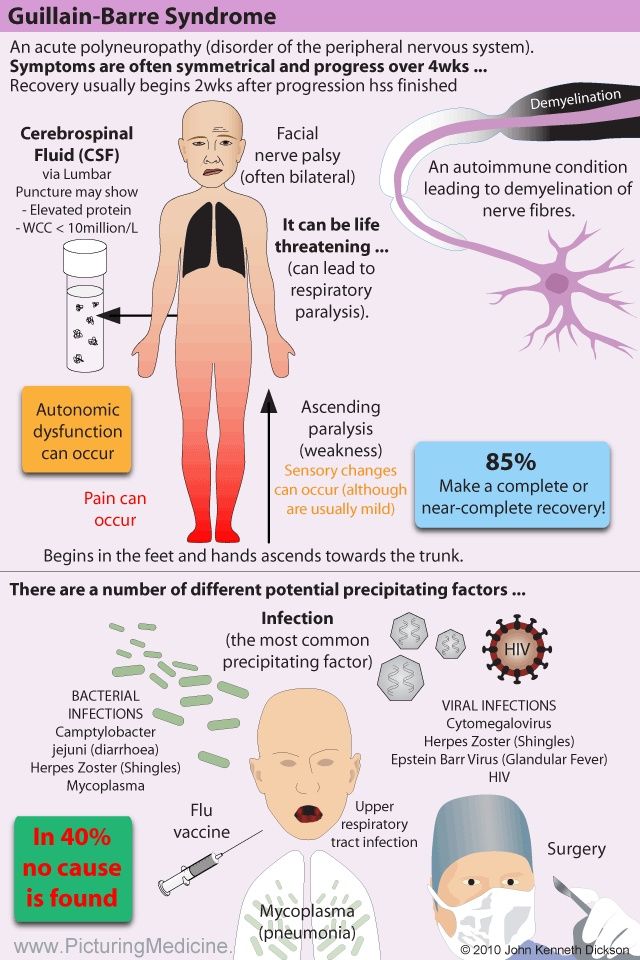

Abruptly stopping antipsychotic therapy comes with a high risk of withdrawal symptoms that include a variety of somatic, motor, and psychological symptoms. [Chouinard et al. 2017]

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF ANTIPSYCHOTIC WITHDRAWAL SYNDROME

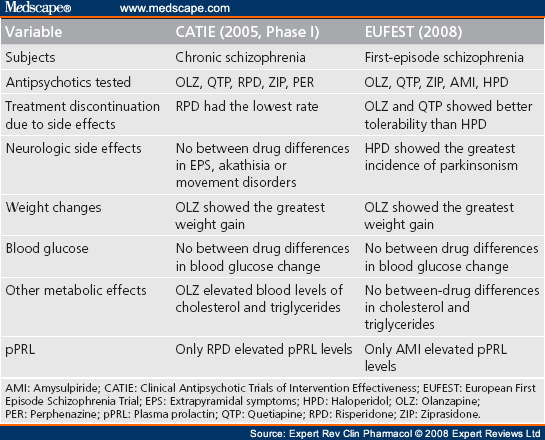

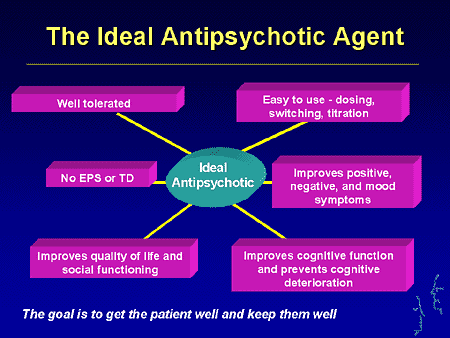

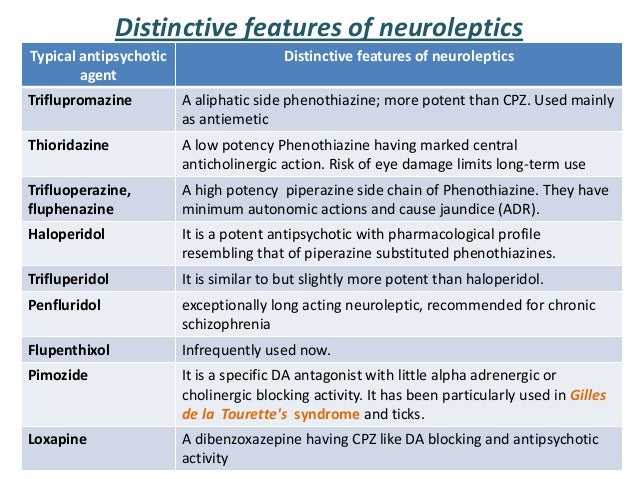

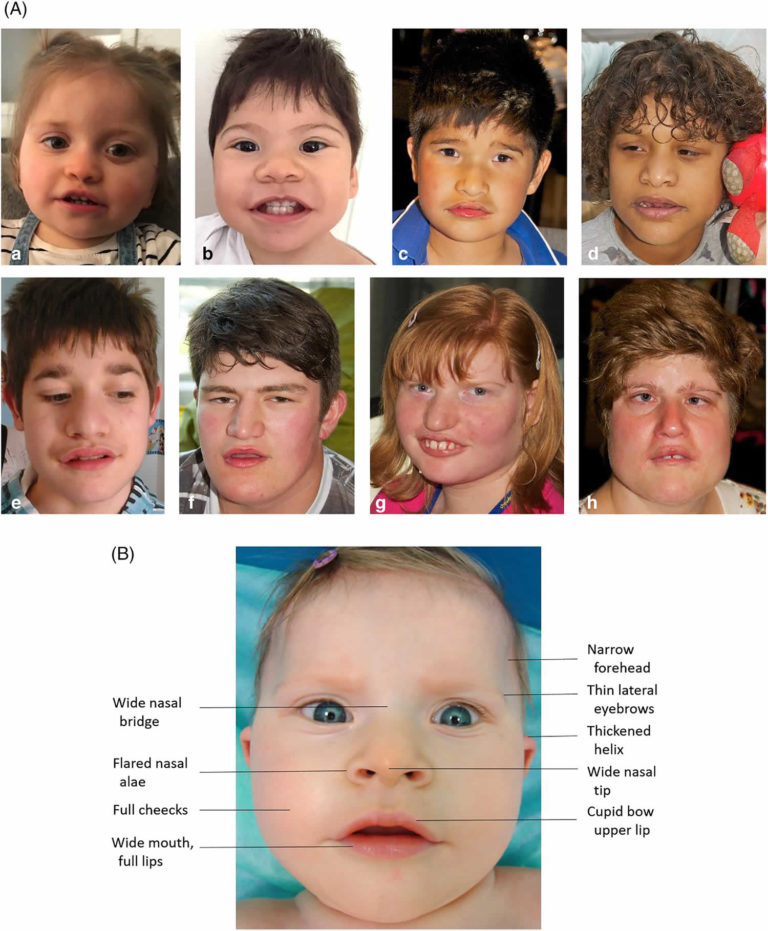

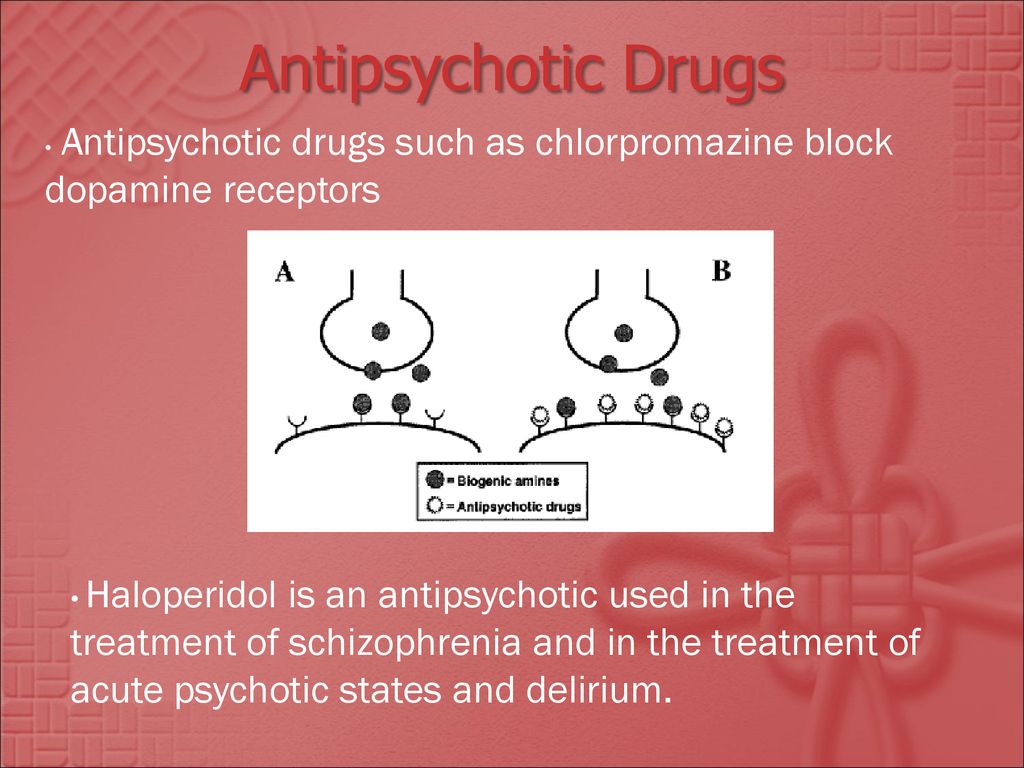

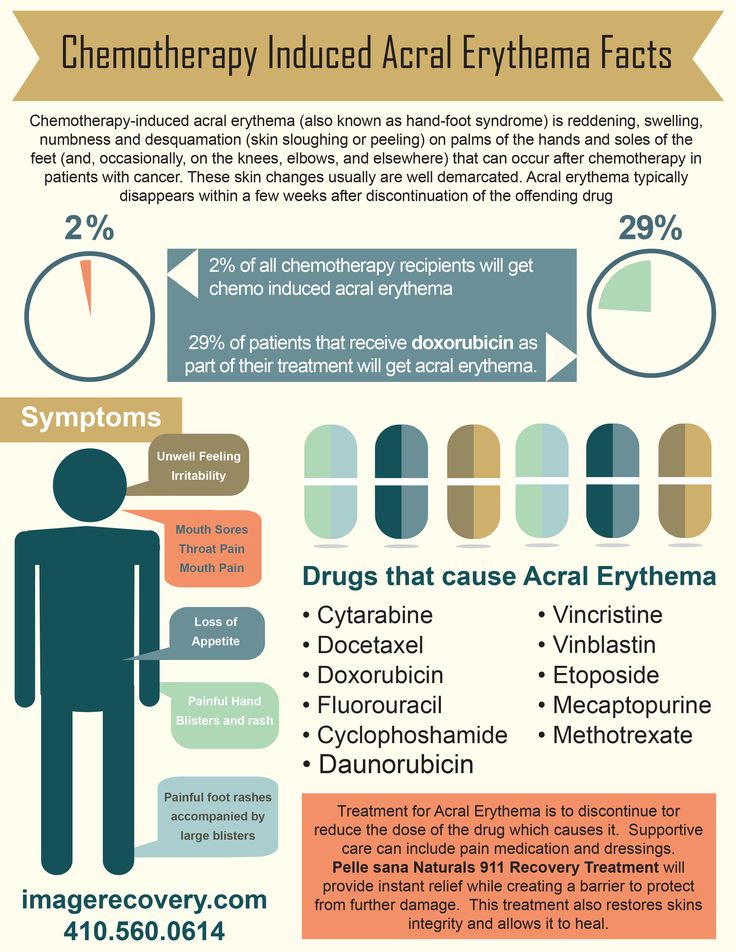

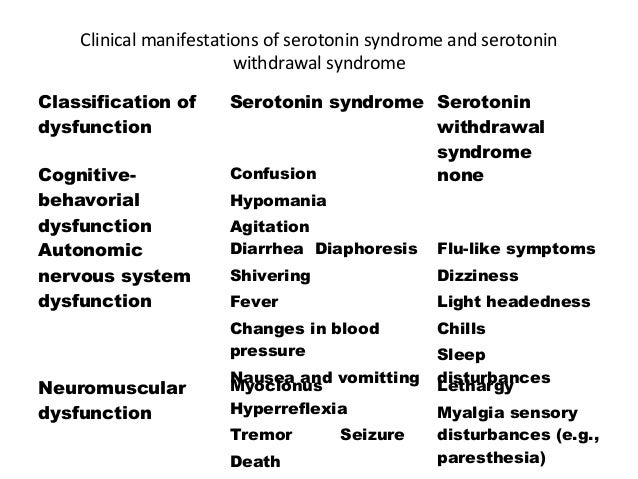

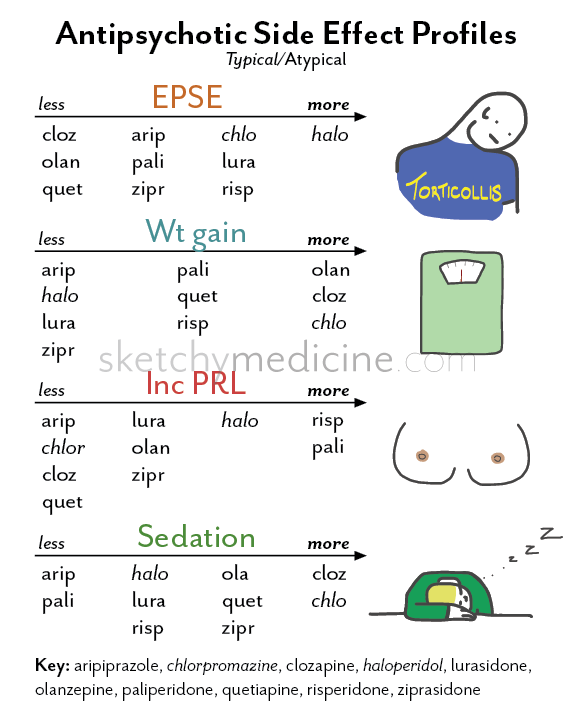

Depending on the antipsychotic drug’s target receptor, both first and second-generation antipsychotics [Read mechanisms of action of antipsychotics] can be associated with the following clinical features: [Horowitz et al 2021]

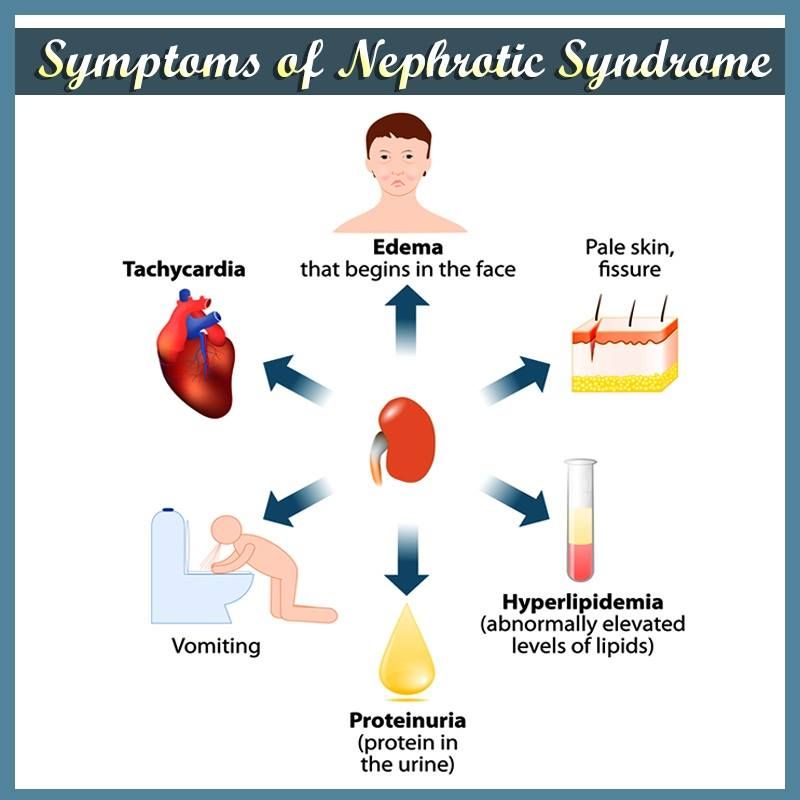

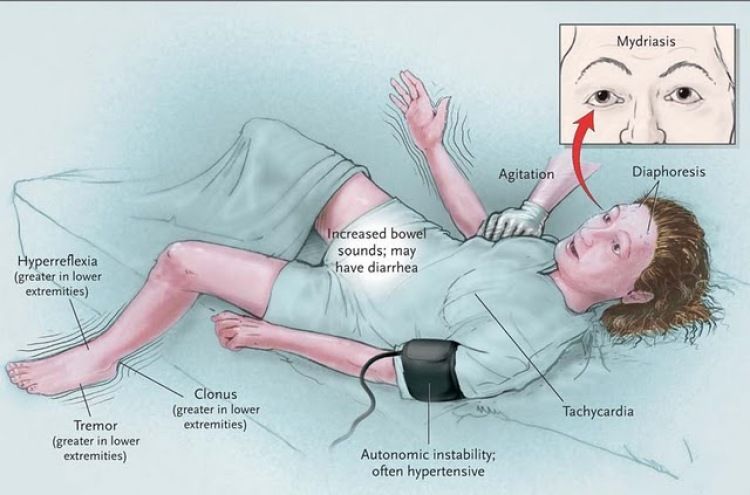

- Adrenergic: Headache, anxiety or agitation, hypertension, tachycardia, angina, palpitations, pre-syncope, tremulousness, sweating, and risk of myocardial infarction.

- Cholinergic: Agitation, insomnia, anxiety or depression, dizziness, tachycardia, nausea, diarrhoea, tremors, restlessness, myalgia, paraesthesia, hallucinations, confusion, hypothermia, sweating.

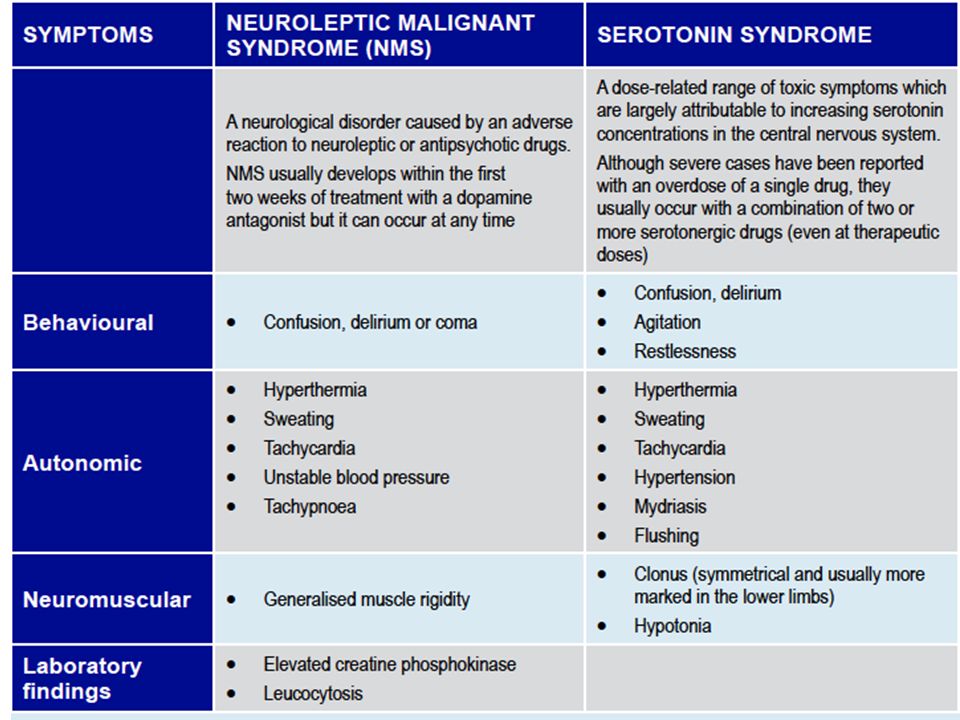

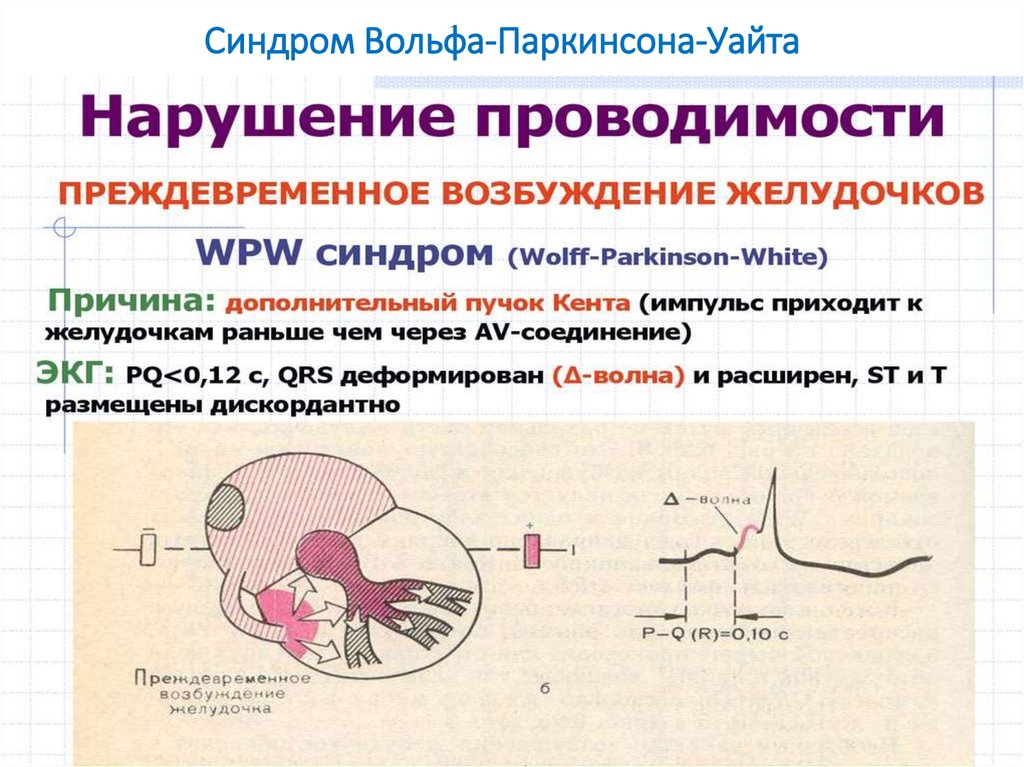

- Dopaminergic (nigrostriatal): Withdrawal dyskinesia, parkinsonism, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and akathisia.

- Dopaminergic (mesolimbic/striatal): Auditory hallucinations, persecutory delusions, and other psychotic symptoms.

- Histaminergic: Irritability, insomnia, agitation, loss of appetite or nausea, tremulousness, incoordination, lethargy, and amnesia.

- Serotonergic: Flu-like symptoms, dizziness, tachycardia, paraesthesia, anxiety, agitation, low mood, insomnia, nausea, diarrhoea, confusion, and lack of concentration.

PHARMACOLOGY OF ANTIPSYCHOTIC WITHDRAWAL

Research shows that the longer the exposure to antipsychotics the higher the risk of developing withdrawal-associated psychosis on discontinuation. [Robinson et al 1999]; [Tiihonen et al 2018]

Tiihonen et al showed that the risk of relapse doubles after 1–2 years, triples after 2–5 years and increases 7 times after 8 years of antipsychotic exposure. This correlation may not be causal as patients with more severe illnesses are likely to be on antipsychotics for longer periods. [Tiihonen et al 2018]

One study reported that 48% of relapses occur in the first 12 months after antipsychotic discontinuation (40% in the first 6 months), with only 2% per year after this period. [Viguera et al., 1997]

[Viguera et al., 1997]

- Furthermore, patients who show tolerance to antipsychotic dose increases are also more likely to have withdrawal symptoms. [Chouinard et al 2017]

- This type of drug tolerance occurs due to the lessening of the drug’s therapeutic effect with continued treatment and the need for an increased dose to achieve the same beneficial effect.

Neurobiology of Withdrawal:

There is evidence of people with no previous history of psychosis who can develop psychotic symptoms after abrupt cessation of dopamine antagonists in a non-psychiatric setting (e.g reserpine, metoclopramide, domperidone).

- Antipsychotic dopamine antagonism over prolonged periods leads to hypersensitivity of dopamine receptors.

- When the antagonist is abruptly withdrawn, physiological levels of dopamine can cause overstimulation of the sensitised receptors, leading to withdrawal or rebound symptoms.

In patients with schizophrenia, the preexisting increased presynaptic dopaminergic synthesising capacity (DSC) combined with post antipsychotic cessation elevated post-synaptic dopamine sensitivity can increase the risk of relapse. [Chouinard et al 2017]

During the phase of post antipsychotic cessation, relapses occur due to a rebound effect which is a combination of neuroadaptations that take months and years to resolve combined with an increased vulnerability to life events and other stressors.

THE HYPERBOLIC CURVE AND MITIGATING ANTIPSYCHOTIC WITHDRAWAL SYMPTOMS

Linear dose reductions produce hyperbolic changes in D2 receptor occupancies, i.e. the reductions at lower doses tend to have the most significant drops in D2 receptor occupancies, increasing the propensity for withdrawal symptoms.

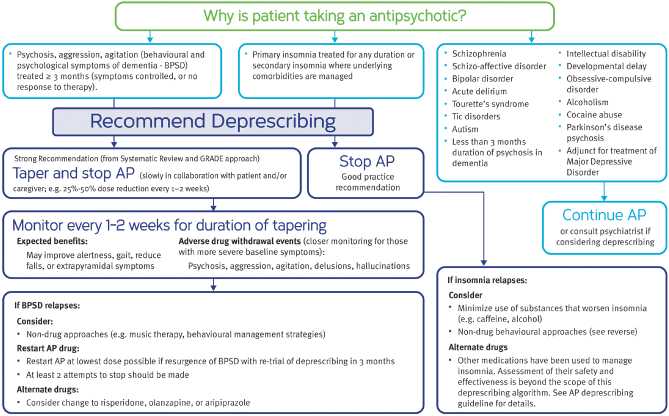

To mitigate the symptoms of antipsychotic withdrawal, the dose is gradually reduced or tapered to the minimum effective dose.

Gradual tapering involves a slow tapering in dose to allow drug-induced neuroadaptations to return to baseline.

However, given it can take 2–5 years for 60-90% of symptoms associated with TD to resolve, it has also been suggested that tapering periods also need to be as prolonged. [Horowitz et al. 2021]

A recent meta-analysis showed that the tapering period had an inverse relationship with the rate of relapse over 12 months: no tapering, 77% of patients relapsed; 1–2 week taper, 57% of patients relapsed; 3–10 week taper, 47% of patients relapsed; and > 10-week taper, 31% of patients relapsed. [Bogers et al. 2020]

Furthermore, the relationship between the dose of antipsychotic and its effect at the receptor may also be informative for creating a tapering schedule.

Here, receptor occupancy calculations at a given dose can provide insights into the effect a linear or hyperbolic reduction in dose has on receptor occupancy. [Lako et al. 2013]

[Lako et al. 2013]

When using haloperidol as an example:

- Linear dose reductions: 4 mg (79% D2 occupancy), 3 mg (76% D2 occupancy), 2 mg (69% D2 occupancy), 1 mg (55% D2 occupancy), 0.5 mg (40% D2 occupancy), and 0.25 mg (25.5% D2 occupancy.

- Hyperbolic dose reductions: 4.4 mg (80% D2 occupancy), 1.2 mg (60% D2 occupancy), 0.50 mg (40% D2 occupancy), and 0.18 mg (20% D2 occupancy).

Here, it can be seen that a linear dose reduction schedule produces an increasingly more significant reduction in percentage points of D2 dopamine antagonism, i.e., there is a greater risk of dopaminergic rebound. It is also worth noting that the smallest tablet is 0.5 mg for haloperidol, and the step down from half of this tablet (0. 25 mg) to 0 mg will produce a perilously considerable 25.5% point reduction.

25 mg) to 0 mg will produce a perilously considerable 25.5% point reduction.

To overcome this significant drop, liquid formulations and tapering strips have recently been developed to provide small tablet formulations and intermediate doses between commonly prescribed dosages. [Groot and van Os 2020]

Olanzapine Dose and Hyperbolic curve:

Risperidone dose and Hyperbolic curve:

APPLYING AN ANTIPSYCHOTIC TAPERING REGIMEN

Horowitz et al. recently published a method for tapering antipsychotics to minimise the risk of relapse. It was suggested that this should be done gradually over months, even years, and should incorporate hyperbolic dose reductions where necessary to provide a more even reduction of D2 blockade. [Horowitz et al. 2021]

Overall, intervals of 3-6 months are suggested with the aim of reducing by ¼ or ½ of the most recent dose, which should be equal to a reduction of 5 or 10 percentage points of D2 occupancy. The following table provides a pharmacologically informed tapering regimen over 10 steps for 6 antipsychotics, with the starting dose representing the lowest recommended dose for multiple episodes of psychosis:

The following table provides a pharmacologically informed tapering regimen over 10 steps for 6 antipsychotics, with the starting dose representing the lowest recommended dose for multiple episodes of psychosis:

Finally, as there are likely to be several demographic and clinical variables that affect this tapering process, it is suggested that the process is personalised by observing the patients response to tapering. However, given any dose reduction is likely to have side effects, these should resolve over time as the underlying neuroadaptations slowly resolve back to baseline. [Gupta et al. 2018]

The final dose of medication before complete cessation may also predict relapse because it might represent a large “step down” in dopaminergic (or other targets) blockade. Thus, final doses before complete cessation may need to be as small as 1/40th a therapeutic dose to prevent a significant decrease in D2 blockade when stopped.

According to Horowitz et al.:

Many patients may tolerate dose reductions of 25%–50% of the most recent dose (corresponding approximately to 5–10 percentage point decrements of D2 occupancy) every 3–6 months. Smaller reductions (such as 10% of the most recent dose) made every month may be more tolerable in the aim of producing more “evenly spread” perturbation to the equilibrium.

Smaller reductions (such as 10% of the most recent dose) made every month may be more tolerable in the aim of producing more “evenly spread” perturbation to the equilibrium.

Due to their long half-life and therefore long duration in reaching steady-state levels, Depot medications provide a form of “in-built” tapering.

For example, 3-monthly paliperidone depot takes 52 weeks to reach a steady-state and may be tapered over 3 years by yearly dose reductions equivalent to approximately 30% D2 occupancy (equivalent to reducing by 10 percentage points of D2 occupancy every 4 months), with the time taken to reach a steady-state providing time for neural adaptation. Very small doses of the depot would be required for final dosing (eg, 90 mg, equivalent to 30% D2 occupancy).

More caution may be required for drugs with short half-lives or ‘hit and run’ characteristics, like clozapine or quetiapine, which can lead to rebound psychosis following withdrawal. It may be necessary to reduce doses by 2.5–5 percentage points of D2 (or cholinergic or histaminergic) occupancy every 6–12 weeks, depending on individual responses.

It may be necessary to reduce doses by 2.5–5 percentage points of D2 (or cholinergic or histaminergic) occupancy every 6–12 weeks, depending on individual responses.

Recent evidence shows that drugs like aripiprazole that are partial agonists at the D 2 receptor are less likely to induce dopaminergic hypersensitivity and thus less likely to lead to a relapse post discontinuation.

SWITCHING PRINCIPLES AND STRATEGIES

In contrast to switching antidepressants, a drug-free period between stopping the first antipsychotic and starting the second is not recommended due to the risk of relapse.

Switching Strategies: [Keks et al, 2019]

Refer to the interactive switching tool

1.Direct Switch:

- The first AP is stopped abruptly and the second AP started the next day.

- Quick but expertise is required.

- Discontinuation symptoms risk is present depending on the choice of the second AP.

- Half-lives of each agent should be taken into account.

- Avoid this strategy when stopping clozapine, olanzapine or quetiapine due to the high risk of anticholinergic and antihistaminergic rebound.

- A possible strategy for switching one partial agonist to another partial agonist, e.g. Aripiprazole to Brexpiprazole (dose adjustments are required for the second AP added)

- Also applicable to switching from Aripiprazole or Brexpiprazole to Cariprazine. (Dose adjustments and monitoring of side effects if recommended due to the overlap of the two medications when using this strategy)

2.Cross Titration / Cross Taper Switch:

- The first AP is gradually reduced and stopped

- The second AP is introduced at a low dose at some stage during the reduction of the first AP so that the patient is taking both AP simultaneously.

- The dose of the second AP is gradually increased to the therapeutic dose when the first AP has been stopped.

- Considered in patients with a high risk of relapse

- Risk of medication interactions

- Increased risk of adverse reactions due to combinations

- Consider the pharmacokinetics of each medication

- Clinicians should base cross-tapering based on the half-lives of the APs.

- Cross-taper and reduction in a short period should be avoided with clozapine, olanzapine or quetiapine.

3. Continuation with slower titration and subsequent discontinuation:

- First antipsychotic is continued at the usual dose or slightly reduced dose while the second AP is gradually titrated up to near therapeutic dose.

- Then, first AP is gradually reduced and stopped, while dose of the second AP is increased to its therapeutic dose.

- Most conservative strategy suitable for patients with a high risk of relapse.

- Significant overlap of the two APs with a likelihood of adverse effects during the switch.

- Risk that the planned discontinuation of the first antipsychotic never takes place or the therapeutic dose of the second antipsychotic is not reached.

- Strategy may be applicable to switch from Olanzapine, Risperidone or Lurasidone to a Pip.

- In switching from Pine or Done to a Pip, clinicians should recognise that based on the hyperbolic curve reductions of Pine’s should be done gradually and over a longer period than shown in the diagrams. This reduction should be individualised to the patient.

4. Stop and Start Second AP at Middle Dose:

- Can be used when switching from a long half-life agent (e.g Aripiprazole, Brexpiprazole or Cariprazine) to a Pine or Done.

- Can be used in the case of Depot to Oral transition.

- Start the oral drug (except clozapine) when the depot antipsychotic was next due.

- Clozapine requires a very slow titration at the start of therapy. Continue the depot antipsychotic until clozapine has reached therapeutic plasma concentrations or has shown a significant clinical effect.

SUMMARY

The risk of relapse after discontinuation of antipsychotic therapy may be reduced by gradual dose tapering over a prolonged period.

The tapering process should be in linear increments, to begin with, but then in a hyperbolic manner to evenly reduce D2 receptor blockade; this process should allow sufficient time for the underlying neuroadaptations to resolve.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS

Antipsychotic Withdrawal Symptoms, Signs, and Detoxification

Antipsychotic abuse has increased as benzodiazepine prescription numbers drop. Learn the common symptoms of abuse and withdrawal for antipsychotics here.

Edited by: Editorial Staff

Last updated on June 8, 2022

When you think about substance abuse, you probably think of substances such as heroin, cocaine, and alcohol—not psychiatric medications. Although they aren’t abused as commonly as illicit drugs, antipsychotics can be abused, and are in fact-finding their way onto the streets.

The lure of antipsychotics may be different from other types of substances that come to mind. Growing research suggests that antipsychotic misuse is attributed to its calming effects on the brain and body as opposed to causing feelings of euphoria. 1 People who struggle with anxiety and sleep disorders may be prone to misusing antipsychotics because of this.1

1 People who struggle with anxiety and sleep disorders may be prone to misusing antipsychotics because of this.1

Medical professionals are becoming increasingly concerned about the potential for misuse of antipsychotics including quetiapine (often referred to by the brand name Seroquel). Changes in prescribing practices over the past century may shed light on the increase in antipsychotic use.1 As awareness has spread about the potential dangers of benzodiazepines and barbiturates, practitioners have changed their prescribing practices, which has led to the prescribing of more antipsychotics.1

What Are Antipsychotics?

Antipsychotics are mainly prescribed to treat mental health disorders that have psychosis as a main symptom, such as bipolar disorder, severe depression, and schizophrenia.2 Antipsychotics do not cure mental health disorders, rather they help alleviate certain symptoms.

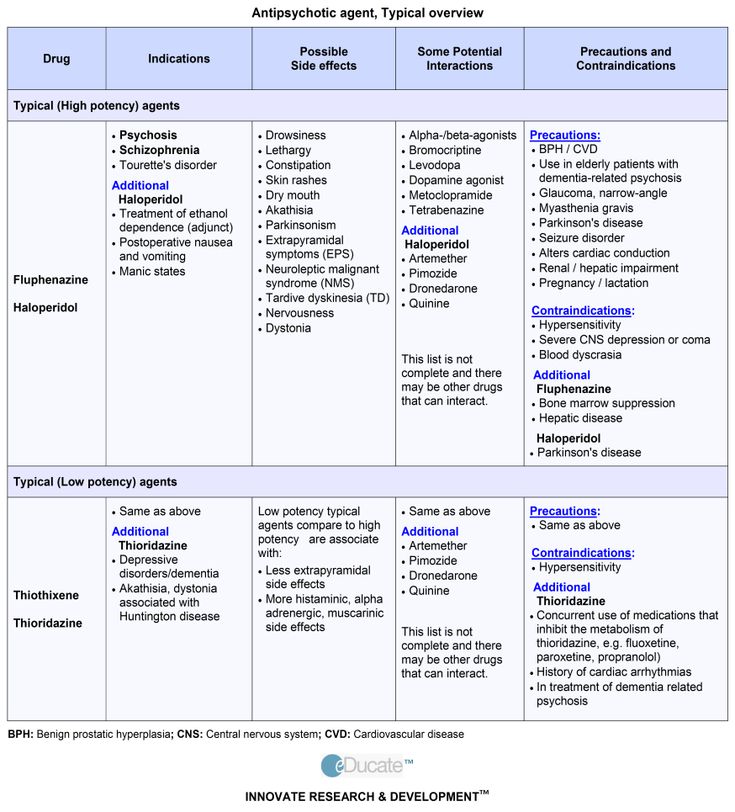

There are two categories of antipsychotics: first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics. First-generation antipsychotics are also called typical antipsychotics or neuroleptics and include medications such as fluphenazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, and chlorpromazine.2

First-generation antipsychotics are also called typical antipsychotics or neuroleptics and include medications such as fluphenazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, and chlorpromazine.2

Second-generation antipsychotics, also known as atypical antipsychotics, were developed after first-generation antipsychotics, and several can treat a broader range of disorders.2 Some common second-generation antipsychotics include risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and olanzapine. Quetiapine, also known by the brand name Seroquel, is a medication that can be used to treat schizophrenia, bipolar depression, mania, and unipolar depression; it can be used alone or combined with other medications. It also can be used to help prevent manic or depressive episodes in people with bipolar disorder.3

Antipsychotics are sometimes used with a combination of other medications to treat various other mental health disorders. These can include depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), eating disorders, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). 2 In fact, growing research is suggesting that atypical antipsychotics combined with antidepressants (especially SSRIs) can help improve the symptoms of drug-resistant depression. Low doses of second-generation antipsychotics combined with SSRIs can improve the antidepressant effects of SSRIs.4 Risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, has been shown to be an effective adjunct treatment for PTSD and OCD.5

2 In fact, growing research is suggesting that atypical antipsychotics combined with antidepressants (especially SSRIs) can help improve the symptoms of drug-resistant depression. Low doses of second-generation antipsychotics combined with SSRIs can improve the antidepressant effects of SSRIs.4 Risperidone, an atypical antipsychotic, has been shown to be an effective adjunct treatment for PTSD and OCD.5

Like most medications that treat mental health disorders, antipsychotics influence various chemical transmitter systems in the brain. First-generation antipsychotics block a certain type of dopamine receptor, specifically the D2 receptors. Second-generation antipsychotics also block the D2 receptors, but, in addition, they block certain serotonin receptors. Some newer second-generation antipsychotics actually partially activate the D2 receptor rather than blocking it.6

Individuals can respond differently to the same medication, so it may take trials with different antipsychotics to find the right fit for an individual. 2

2

Are Antipsychotics Abused?

Studies suggest that the most commonly abused antipsychotic is the atypical antipsychotic quetiapine (also known by the brand name Seroquel).1 Misuse of a prescription drug includes when a person obtains a prescription medication off the streets or from a friend or family member (as opposed to obtaining their own prescription from a medical provider), faking symptoms to obtain a prescription, using medication more than directed by the prescriber, or otherwise using it in a way that was not directed. Signs that quetiapine is the most commonly misused atypical antipsychotic include that it has street names and black market value, that individuals will fake symptoms to obtain it, and that individuals will snort quetiapine or inject it into their veins.1

Atypical antipsychotics are sometimes used to treat withdrawal symptoms from substances such as cocaine, alcohol, opioids, and benzodiazepines. However, research has not found consistent evidence that this is successful. Furthermore, some case studies suggests that quetiapine can cause drug-seeking behaviors. 1

Furthermore, some case studies suggests that quetiapine can cause drug-seeking behaviors. 1

Individuals may be more likely to abuse antipsychotics in restrictive environments such as jails and prisons since obtaining drugs off the street and obtaining controlled substances like opioids and benzodiazepines from medical providers generally aren’t options.1

Do Antipsychotics Cause Withdrawal?

Although you may have heard the term “withdrawal,” the term “antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome” may be new to you. Antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome is a name for the collection of symptoms that may occur when someone suddenly stops an antipsychotic or drastically lowers their dose.

A person may stop taking their antipsychotic medication for various reasons, such as because the medication is (or is perceived to be) not effectively treating symptoms, because it is causing unbearable side effects, or because the person does not think they should be taking the medication or do not agree with how they were instructed to take it. 7

7

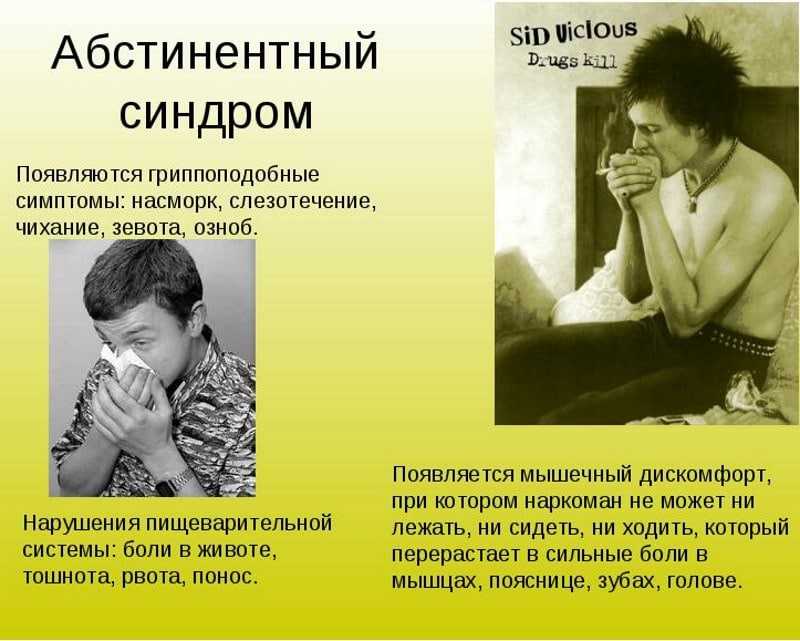

Symptoms that may be experienced during antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome include:7

- Vomiting, nausea, and/or diarrhea

- Difficulty sleeping, restlessness, anxiety, and/or agitation

- Dizziness

- Runny nose

- Problems with muscle movement including involuntary muscle contractions, inability to stay still, and/or uncontrollable movements

Antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome symptoms generally appear within the first few days after you stop use or significantly reduce use.7 The symptoms tend to be the most severe around the one-week mark and subside after that.7

The limited research that does exist suggests that up to 40% of the people who stop taking antipsychotics, including first- and second-generation, may experience antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome.7

Discontinuation of clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has been shown to have more severe symptoms, including rebound psychosis, than discontinuation of other types of antipsychotics. Clozapine discontinuation is also associated with more rapid onset of symptoms.7

Clozapine discontinuation is also associated with more rapid onset of symptoms.7

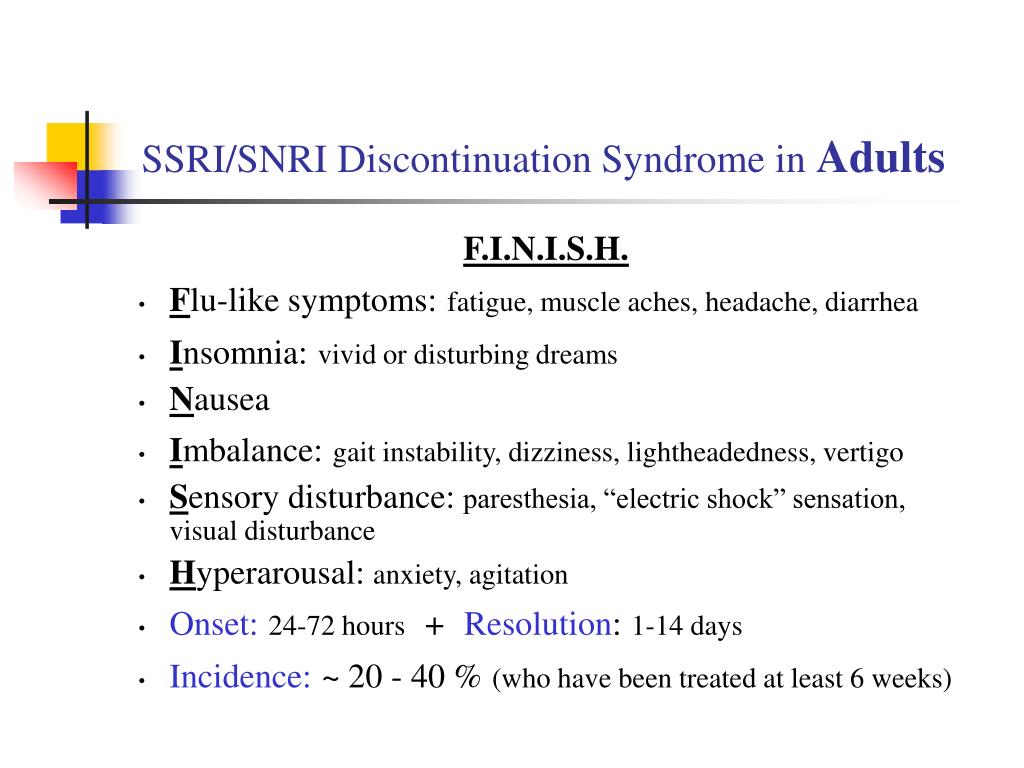

As previously mentioned, antipsychotics are sometimes prescribed with other types of medication, such as antidepressants. Suddenly stopping or significantly decreasing an antidepressant can cause an antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. Therefore, if an individual suddenly stops both an antidepressant and an antipsychotic medication, they may experience additional withdrawal symptoms or more severe symptoms. Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome symptoms may include:10

- Dysphoria.

- Gastrointestinal issues.

- Sensory disruptions.

- Dizziness and/or trouble with balance.

- Fatigue.

- Anxiety and/or hyperarousal

- Trouble sleeping.

- Headache.

- Flu-like symptoms

When people who are prescribed antipsychotics for psychotic disorders stop taking them, some relapse, meaning that their psychosis returns. However, some patients are able to sustain a psychosis-free existence after the cessation of antipsychotics. Several studies show that only 25%–55% of patients with schizophrenia who stopped taking antipsychotic medication experienced the relapse of symptoms in the first 6 to 10 months after they stopped taking them.9

However, some patients are able to sustain a psychosis-free existence after the cessation of antipsychotics. Several studies show that only 25%–55% of patients with schizophrenia who stopped taking antipsychotic medication experienced the relapse of symptoms in the first 6 to 10 months after they stopped taking them.9

How to Safely Stop Taking Antipsychotics

You may wonder if you should stop taking antipsychotics. Beginning and discontinuing the use of antipsychotics is a quandary faced by doctors treating patients with psychosis. Research has yet to determine the best practices for the management of schizophrenia over the long term.

You should never stop or change how you take your medication on your own. Talk to your medical provider prior to any medication changes or cessation of use. If it’s an emergency, such as if you are having severe side effects, call 911. Medical professionals can monitor your symptoms as well as provide guidance on safely titrating your dose. Research indicates that gradually lowering the dose of antipsychotics can decrease antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome symptom severity.7

Research indicates that gradually lowering the dose of antipsychotics can decrease antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome symptom severity.7

When stopping or switching antipsychotics, medical providers may prescribe additional medication to help prevent or lessen the symptoms of withdrawal.11 Keep in mind that there is no “one-size-fits-all” when it comes to safely and effectively stopping or switching antipsychotics. Symptoms that were being treated with the antipsychotic, such as psychosis, depression, and agitation, can re-emerge after you stop taking the antipsychotic medication. Discuss any symptoms that develop with your healthcare provider.11

Short-term risks of stopping your antipsychotic medication include antipsychotic discontinuation syndrome and the return of symptoms that were being treated. Long-term risks can also include the return of symptoms.

Treatment Options for Antipsychotics

If you are using an antipsychotic as prescribed by a medical professional but would like to stop it or switch to something else, talk with your healthcare provider. If you struggle with misusing antipsychotics, you may need substance use disorder treatment. Options for treatment providers include general mental health care providers and providers that specialize in substance use disorders specifically. Treatment may be offered in an inpatient and/or outpatient setting.

If you struggle with misusing antipsychotics, you may need substance use disorder treatment. Options for treatment providers include general mental health care providers and providers that specialize in substance use disorders specifically. Treatment may be offered in an inpatient and/or outpatient setting.

If you suffer from a mental illness and also struggle with misusing antipsychotic medication, you may want to consider a treatment setting that specializes in integrated care for co-occurring disorders. Co-occurring disorders are when a person has both a substance use disorder and a mental health disorder. For individuals with co-occurring disorders, integrated treatment that addresses all psychiatric disorders provides better results.12

Severe depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia can have severe symptoms. Those symptoms combined with withdrawal symptoms can be especially challenging. Staff in facilities offering integrated treatment should have specialized training in treating mental health and substance use disorders and the symptoms that accompany both. If you have been misusing antipsychotics and are addicted to other substances, substance use disorder treatment is especially important.

If you have been misusing antipsychotics and are addicted to other substances, substance use disorder treatment is especially important.

Antipsychotic Treatment Resources:

Antipsychotic withdrawal syndrome | is... What is Antipsychotic Withdrawal Syndrome?

Antipsychotic withdrawal syndrome (neuroleptics) - mental, neurological, etc. disorders that develop within days or weeks after cessation of antipsychotic treatment or dose reduction. It is characteristic primarily for typical antipsychotics. [1]

|

Contents

|

General characteristics

The maximum severity of withdrawal symptoms usually occurs within 1-4 days, followed by resolution in 7-14 days, in some cases up to 3-4 weeks. Symptoms are more pronounced with a sharp break in therapy, transfer from a low-potency antipsychotic to another antipsychotic, and while stopping the use of correctors. The mechanism of the withdrawal syndrome is based on the development of pharmacodynamic stress against the background of adaptation and hypersensitivity of mediator systems, mainly dopaminergic and cholinergic. In addition, the termination of the antiemetic and sedative effect of neuroleptics also plays a certain role. [2]

Symptoms are more pronounced with a sharp break in therapy, transfer from a low-potency antipsychotic to another antipsychotic, and while stopping the use of correctors. The mechanism of the withdrawal syndrome is based on the development of pharmacodynamic stress against the background of adaptation and hypersensitivity of mediator systems, mainly dopaminergic and cholinergic. In addition, the termination of the antiemetic and sedative effect of neuroleptics also plays a certain role. [2]

To avoid this syndrome, withdrawal of neuroleptics should be carried out gradually under medical supervision. [3]

Varieties of withdrawal syndrome

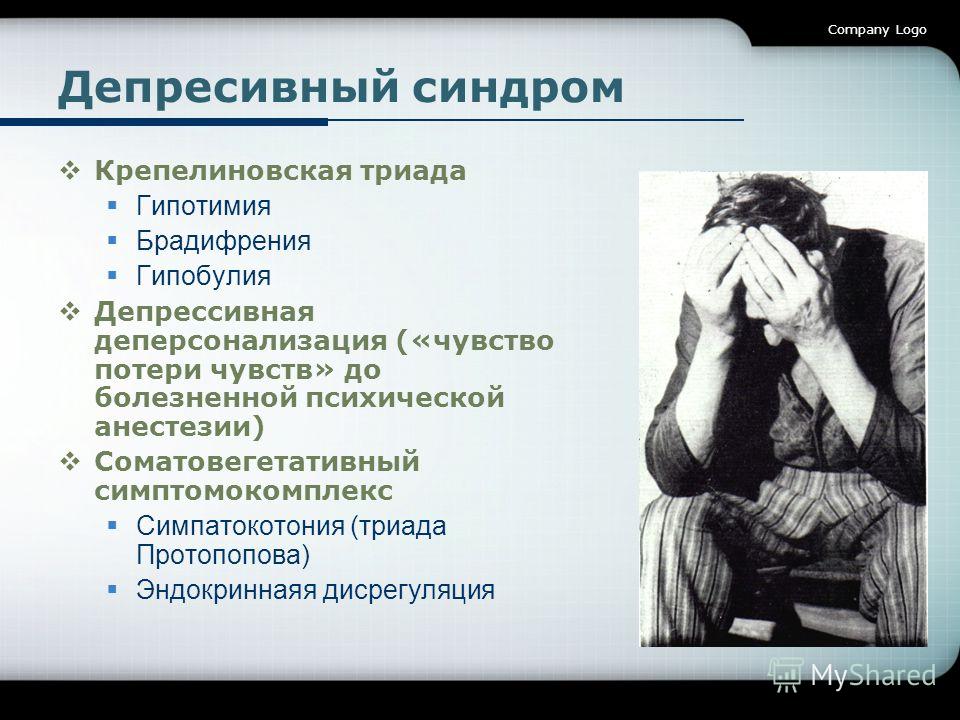

Hypersensitivity or "rebound" psychosis

Main article: Hypersensitivity psychoses

Clinical manifestations: return of the previous or even the appearance of a new psychotic symptomatology or shortly after the start of a dose reduction of the neuroleptic . Often psychoses of hypersensitivity may be accompanied by other symptoms of dopamine hypersensitivity (development of tardive dyskinesia), they may be accompanied by an increase in the level of prolactin in the blood.

It is assumed that long-term administration of typical antipsychotics leads to an increase in the density of postsynaptic dopamine receptors in the CNS, including in the mesolimbic region. The phenomenon of hypersensitivity of dopamine structures in the mesolimbic region that develops in this way can manifest itself as a result of the abolition or reduction of doses of antipsychotics. [1]

Hypersensitivity psychosis should be differentiated from an exacerbation of a mental disorder for which neuroleptic therapy was performed. The risk of exacerbation in stable patients is low in the first 2–3 weeks after discontinuation of the antipsychotic and increases in subsequent months. [2] Hypersensitivity psychoses have been reported in people without a history of mental disorders. [4]

Rebound dyskinesia, or unmasked dyskinesia

See also: Tardive dyskinesia

weeks after the abolition of the neuroleptic or a decrease in its dose and completely regressing in the next 3 months. Clinically, recoil dyskinesia can manifest itself with symptoms characteristic of tardive dyskinesia: choreiform or dystonic hyperkinesis or a combination of them, withdrawal akathisia, etc. As with tardive dyskinesia, tongue movements, chewing movements, frequent blinking, choreiform or ballistic movements of the limbs, spastic torticollis can be observed , unusual vocalizations. [5]

Clinically, recoil dyskinesia can manifest itself with symptoms characteristic of tardive dyskinesia: choreiform or dystonic hyperkinesis or a combination of them, withdrawal akathisia, etc. As with tardive dyskinesia, tongue movements, chewing movements, frequent blinking, choreiform or ballistic movements of the limbs, spastic torticollis can be observed , unusual vocalizations. [5]

The reason for the development of recoil dyskinesia is hypersensitivity of dopamine receptors in the nigrostriatal region, which develops as a result of long-term use of the neuroleptic [1] . Also, cholinergic hyperactivity and an imbalance between the level of dopamine and acetylcholine in the basal ganglia can be causes. [6]

With simultaneous withdrawal of antipsychotics and anticholinergics, the risk of developing dyskinesias increases. Taking anticholinergics within 1-2 weeks after the withdrawal of antipsychotics significantly reduces the risk of developing dyskinetic disorders. [1]

[1]

Treatment. Mild cases generally do not require special treatment. With severe dyskinesia, anxiety, nausea, disrupting the daily activity of patients, it is possible to re-administer the antipsychotic, the cancellation of which caused dyskinesia, at a lower dose, followed by its slow withdrawal. Sometimes an atypical antipsychotic is prescribed instead. Additionally, benzodiazepines are used, and with dystonic hyperkinesis - anticholinergics. In severe cases, the use of lithium and valproic acid preparations is also recommended. [5]

Cholinergic Rebound Syndrome

See also: Clozapine

Includes flu-like symptoms, insomnia, agitation, confusion [1] , restlessness, anxiety, extrapyramidal disorders [02.06]

Apparently, the mechanism of neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome is based on hypersensitivity not only of dopamine, but also of muscarinic cholinergic receptors. Especially often, symptoms of cholinergic hypersensitivity develop after the withdrawal of low-potency antipsychotics, such as chlorpromazine (chlorpromazine), since drugs in this group have a greater affinity for muscarinic receptors compared to high-potency antipsychotics. [1] High affinity for cholinergic receptors is also characteristic of clozapine and olanzapine, drugs among atypical antipsychotics that are characterized by the greatest risk of developing this syndrome. It can also occur with the abolition of anticholinergics taken simultaneously with antipsychotics (correctors for neuroleptic therapy). [2]

[1] High affinity for cholinergic receptors is also characteristic of clozapine and olanzapine, drugs among atypical antipsychotics that are characterized by the greatest risk of developing this syndrome. It can also occur with the abolition of anticholinergics taken simultaneously with antipsychotics (correctors for neuroleptic therapy). [2]

"Early activation"

"Early activation" refers to the development of excess energy, increased activity, and insomnia in a patient after the withdrawal of an antipsychotic. Traditionally, these symptoms have been viewed as a stimulant effect of a new drug due to switching the patient to another antipsychotic, as an adverse event in psychotic patients, or as signs of worsening psychosis. In fact, the clinical phenomenon of "early activation" should be considered solely as a withdrawal effect.

This effect is associated with the cessation of the blockade of type 1 histamine receptors (H 1 ) and develops with a sharp withdrawal of drugs characterized by a high affinity for these receptors. These drugs include most sedative (low-potency) antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, tizercin, etc.), as well as olanzapine and clozapine.

These drugs include most sedative (low-potency) antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, tizercin, etc.), as well as olanzapine and clozapine.

In each specific case, a differential diagnosis of "early activation" with akathisia, agitation and a reduction in the sedative effect is necessary. [2]

Other symptoms

Non-specific disorders: gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, diarrhea), sweating, headache, etc. [1]

Notes

- ↑ 9000 2 3 4 5 9000 9000

137

7 8 Zharkova N.B. Transition to therapy with atypical antipsychotics - a question of strategy or tactics of psychopharmacotherapy? // Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy . - 2001. - Vol. 3. - No. 1. - ↑ 1 2 3 4

004

Tsukarzi E. E. Optimization of tactics for changing antipsychotic therapy on the quetiapine model // Psychiatry, psychotherapy and clinical psychology . - 2011. - No. 2. - S. 76-85.

E. Optimization of tactics for changing antipsychotic therapy on the quetiapine model // Psychiatry, psychotherapy and clinical psychology . - 2011. - No. 2. - S. 76-85. - ↑ Reference guide to psychopharmacological and antiepileptic drugs approved for use in Russia / Ed. S. N. Mosolova. - Ed. 2nd, revised. - M .: "Publishing house BINOM", 2004. - S. 25. - 304 p. - 7000 copies. — ISBN 5-9518-0093-5

- ↑ Moncrieff J Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse // Acta Psychiatr Scand . — 2006 Jul. - T. 114. - No. 1. - S. 3-13. — DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x — PMID 16774655.

- ↑ 1 2 3 3 V. N. Shtok, I. A. Ivanova-Smolenskaya, O. S. Levin. - Moscow: MEDpress-inform, 2002. - S. 418-419. - 608 p.

— ISBN 5-2-29-3

— ISBN 5-2-29-3 - ↑ Gardos G, Cole JO, Tarsy D Withdrawal syndromes associated with antipsychotic drugs // Am J Psychiatry . — 1978 Nov. - T. 135. - No. 11. - S. 1321-4. — PMID 30287.

See also

- Withdrawal

- Antipsychotic extrapyramidal disorders

- Neuroleptic deficient syndrome

Antipsychotic withdrawal syndrome - articles "Verimed"

Contents:

- Causes of withdrawal symptoms

- Symptoms of neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome

2.1. Hypersensitivity psychosis

2.2. Unmasked dyskinesia

2.3. Cholinergic return

2.4. Early activation - Coping with symptoms of withdrawal from antipsychotics

Antipsychotics or antipsychotics are a group of drugs that have the property of inhibiting the functions of the central nervous system. They are used in the treatment of various neuropsychiatric disorders. But in case of exceeding the permissible dosage or prolonged use after a sharp refusal, an unpleasant neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome develops.

Consultation around the clock!

We know about all the effective methods of getting rid of addiction!

+7 (495) 792-03-93 8 (800) 600-63-23 free call

Request a call

Causes of withdrawal symptoms

Psycho-emotional, neurological, somatic abnormalities often occur after the end of antipsychotic therapy or when the amount consumed is reduced. Syndrome of withdrawal of neuroleptics or brittle is called the totality of such manifestations. Most often, these disorders are caused by typical drugs, and much less often by atypical analogues.

Such changes are formed under the influence of the following factors:

- prolonged use of antipsychotics;

- wrong initial therapeutic dose;

- discontinuation of medication;

- reduction in accepted volumes;

- suspension of parallel application of correctors;

- replacement of the used one with another medication.

Withdrawal rates are essentially a pharmacodynamic stress for the body. It arises due to increased sensitivity of mediator systems: dopamine, cholinergic and others.

Start Your Treatment Now!

Leave a request for treatment and you will have time to save your health or a loved one!

+7 (495) 792-03-93 8 (800) 600-63-23free call

Request a call

Symptoms of neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome

The severity and duration of withdrawal after antipsychotics depend on the type of withdrawal. The most pronounced signs are non-specific hypersensitivity psychoses, unmasked dyskinesia, cholinergic recoil, etc.

How long neuroleptic withdrawal lasts depends on many aspects. This is the name of the pharmacological compound, the duration of the prescribed course, the causes of withdrawal, the presence of concomitant or provoked by intoxication psycho-emotional disorders and physical ailments in the patient. The first signs usually appear 1-4 days after using the drug, and the duration of the neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome is from 7 to 14 days, in especially severe cases - up to one month.

The first signs usually appear 1-4 days after using the drug, and the duration of the neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome is from 7 to 14 days, in especially severe cases - up to one month.

Hypersensitivity psychosis

Often these manifestations are associated with an increase in the susceptibility of dopamine receptors to the effects of antipsychotics. Prolonged inhibition of receptors causes blockage of cholinergic connections, which provokes the desire to increase their number and restore neural transmission.

With psychotic hypersensitivity, the following symptoms are possible:

- visual, auditory and tactile hallucinations;

- delusional states, various manias;

- variations of mental automatism;

- involuntary and unexplained movements of the facial muscles and tongue;

- spasms and twitches of limbs and trunk.

Such complications do not require special treatment: a return to the original dosage or the use of correctors will help.

Leave a request for a free consultation or call a doctor

and we will contact you within 5 minutes!

+7 (495) 792-03-93 8 (800) 600-63-23 free call

Request a call

Aleksey Vladimirovich Bulkin

General Director of the VERIMED Clinic, Psychiatrist-narcologist

Unmasked dyskinesia

limbs, curvature of the neck, unusual sounds.

This is due to a change in the established ratio of dopamine and acetylcholine in certain parts of the central nervous system and cholinergic hyperactivity formed against this background. To get rid of negative indicators in especially difficult situations, benzodiazepine and anticholinergic drugs are prescribed.

Cholinergic response

The risk of developing such dysfunctions increases with the use of low potency antipsychotics and the use of atypical drugs. As a result, the patient experiences:

- dizziness and migraine;

- increased drowsiness and lethargy;

- difficulty urinating;

- relaxation of the muscles of the gastrointestinal tract;

- dilated pupils and redness of the eyes;

- complication of swallowing functions;

- problems with memory and attention;

- clouding of consciousness.

How to alleviate neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome in the development of cholinergic rebound? To do this, you will need to adjust the dose or prescribe a substance with a milder effect. In parallel, symptomatic drug therapy is needed to cure somatic and mental disorders.

Early activation

At the end of the blocking effect of neuroleptic substances, signs of refusal appear, which are accompanied by headaches, the appearance of excessive psycho-emotional and physical activity, sleep disturbances, uncontrolled movements.

A similar clinical picture was previously considered as pathological deviations of the underlying ailment or side effects of a neuroleptic pharmaceutical preparation. However, at this stage, the formation of signs of early activation signals the onset of withdrawal after stopping the medication.

Do you want to know all options for the cost of services?

Contact our specialist:

+7 (495) 792-03-93 8 (800) 600-63-23 free call

Order a call

Ways to overcome the symptoms of withdrawal from antipsychotics

It is better to entrust the choice of methods and duration of treatment to specialists. Attempts to independently get out of the withdrawal trap can result in irreversible consequences for the psyche and physical health.

Attempts to independently get out of the withdrawal trap can result in irreversible consequences for the psyche and physical health.

Based on the collected history and the results of the examination, only a doctor is able to expertly suggest how to survive the neuroleptic withdrawal syndrome and develop an individual medication program. The patient, depending on the severity of the disease, personal indicators and the clinical picture, may need:

- dosage adjustment;

- return to the previous scheme with a subsequent decrease in the amount received;

- substitution of a drug for a drug with a milder effect;

- infusion-drip therapy;

- drug course to relieve painful manifestations;

- psychotherapeutic sessions.

Even if you know all the symptoms and duration of antipsychotic withdrawal syndrome, give up the intention to cope with problems at home. With the best outcome, you will simply lose time, and with the worst, you will get a whole bunch of severe and sometimes irreversible complications and adverse reactions.