Antidepressants and breast feeding

Breastfeeding & Psychiatric Medications - MGH Center for Women's Mental Health

Given the prevalence of psychiatric illness during the postpartum period, a significant number of women may require pharmacological treatment while nursing. Appropriate concern is raised, however, regarding the safety of psychotropic drug use in women who choose to breastfeed while taking these medications. While many women with postpartum illness delay treatment because they are worried that the medications they take may harm the nursing infant, the accumulated data indicates that the risk of adverse events in the nursing infant is low.

General Principles

Given the many benefits of breastfeeding, some women taking psychiatric medications may wish to nurse their infants. When making this decision, several variables must be considered. These include the known and unknown risks of medication exposure for the baby via breast milk, the effects of untreated illness in the mother, and the benefits of and maternal preferences for breastfeeding.

There are established health benefits of breastfeeding for babies and mothers.

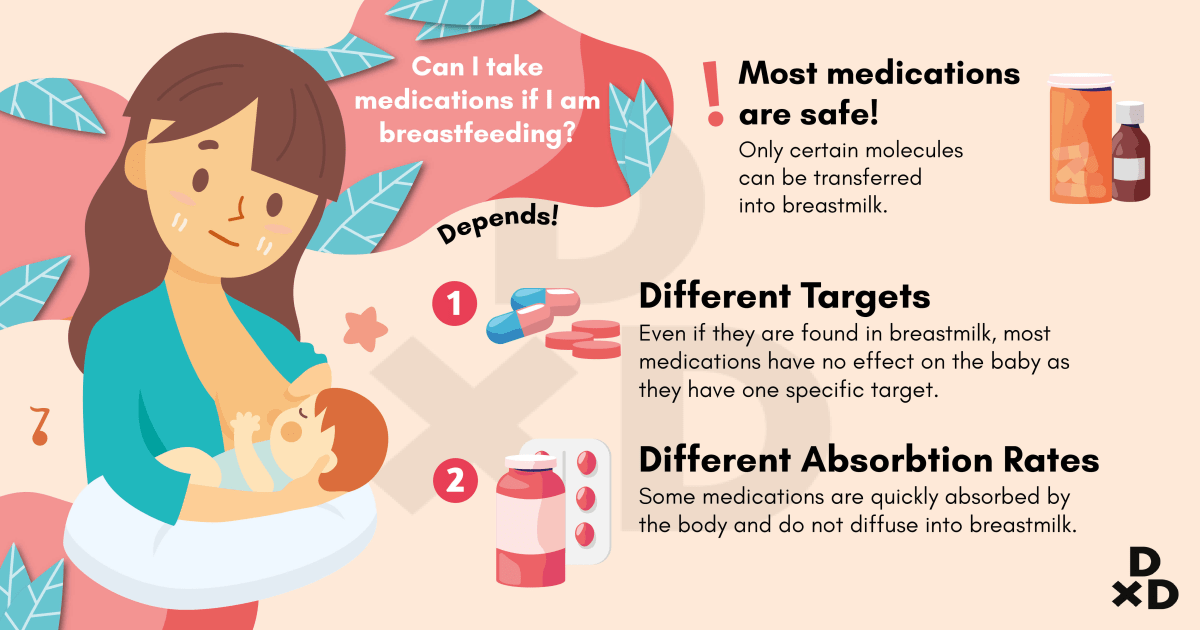

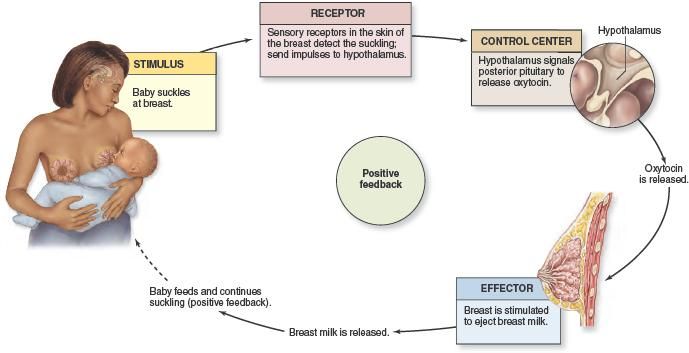

Efforts have been made to quantify the amount of psychotropic medications and their metabolites in the breast milk of nursing mothers. In order to more accurately measure the infant’s exposure to medication, serum drug levels in the infant have also been assessed. From the available data, it appears that all medications, including antidepressants, antipsychotic agents, mood stabilizers, and benzodiazepines, are secreted into the breast milk. However, concentrations of these agents in breast milk vary considerably. The amount of medication to which an infant is exposed depends on several factors: factors pertaining to the specific medication, the maternal dosage of medication, the frequency of dosing and infant feedings, and the rate of maternal drug metabolism.

The decision to breastfeed while taking medications is more complicated when a baby is premature or has medical complications. The nursing infant’s chances of experiencing toxicity are dependent not only on the amount of medication ingested but also on how well any ingested medication is metabolized. Most psychotropic medications are metabolized by the liver. During the first few weeks of a full-term infant’s life, there is a lower capacity for hepatic drug metabolism, which is about one-third to one-fifth of the adult capacity. Over the next few months, the capacity for hepatic metabolism increases significantly and, by about 2 to 3 months of age, it surpasses that of adults. In premature infants or in infants with signs of compromised hepatic metabolism (e.g., hyperbilirubinemia), breastfeeding typically is deferred because these infants are less able to metabolize drugs and may be more likely to experience adverse events.

Most psychotropic medications are metabolized by the liver. During the first few weeks of a full-term infant’s life, there is a lower capacity for hepatic drug metabolism, which is about one-third to one-fifth of the adult capacity. Over the next few months, the capacity for hepatic metabolism increases significantly and, by about 2 to 3 months of age, it surpasses that of adults. In premature infants or in infants with signs of compromised hepatic metabolism (e.g., hyperbilirubinemia), breastfeeding typically is deferred because these infants are less able to metabolize drugs and may be more likely to experience adverse events.

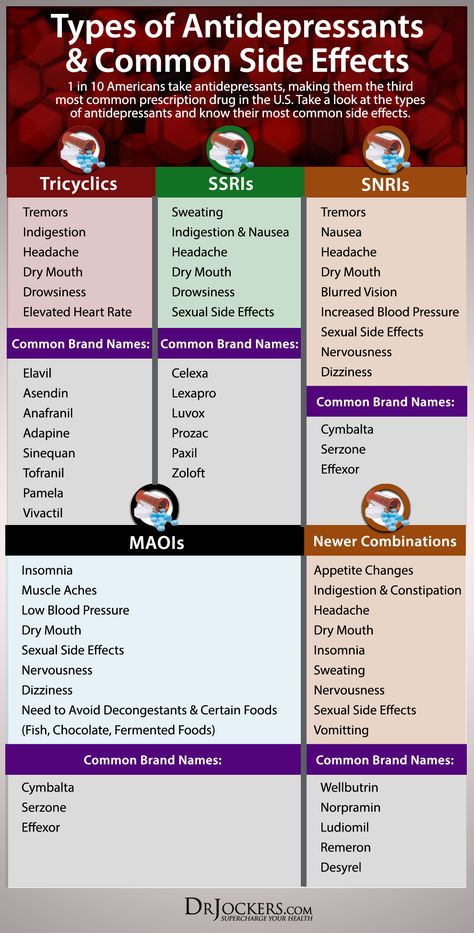

Antidepressants in general are considered to be relatively safe for use during breastfeeding when clinically warranted, and SSRIs in particular are one of the best studied classes of medications during breastfeeding. Excellent and thorough reviews on the topic of antidepressants and breastfeeding have been published (Burt 2001; Weissman 2004). In the most rigorous studies, nursing women have repeatedly provided breast milk samples and infant blood samples in order for investigators to quantify medication exposure to the infant.

In the most rigorous studies, nursing women have repeatedly provided breast milk samples and infant blood samples in order for investigators to quantify medication exposure to the infant.

Data have accumulated regarding the use of various antidepressant medications during breastfeeding. Available data on the use of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline during breastfeeding have been encouraging and suggest that the amounts of drug to which the nursing infant is exposed is low and that significant complications related to neonatal exposure to antidepressants in breast milk appear to be rare. Typically very low or non-detectable levels of drug have been detected in the infant serum, and one recent report indicates that exposure to medication in breast milk does not result in clinically significant blockade of serotonin (5-HT) reuptake in infants.

Although less information is available on other antidepressants, serious adverse events related to exposure to these medications have not been reported. There have been a small number of case reports of adverse events in infants exposed to antidepressants in breast milk, including jitteriness, irritability, excessive crying, sleep disturbance, and feeding problems. In many cases it has not been possible to establish a causal link between these events and exposure to drug.

There have been a small number of case reports of adverse events in infants exposed to antidepressants in breast milk, including jitteriness, irritability, excessive crying, sleep disturbance, and feeding problems. In many cases it has not been possible to establish a causal link between these events and exposure to drug.

Many clinicians and their patients ask which antidepressant is the “safest” for breastfeeding. It is somewhat misleading to say that certain medications are “safer” than others. All medications taken by the mother are secreted into the breast milk, and there is no evidence to suggest that certain antidepressants pose significant risks to the nursing infant.

In terms of selecting an appropriate antidepressant, one should try to choose an antidepressant for which there are data to support its safety during breastfeeding (i.e., sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine, tricyclic antidepressants). However, some situations may warrant the use of antidepressants with less available safety data. For example, if a woman has responded to a particular antidepressant in the past, it would be reasonable to consider using that antidepressant again. If she has been taking an antidepressant during the course of her pregnancy and has been doing well, it would be prudent to continue with that same antidepressant after delivery, as switching to another antidepressant may put her at increased risk for relapse.

For example, if a woman has responded to a particular antidepressant in the past, it would be reasonable to consider using that antidepressant again. If she has been taking an antidepressant during the course of her pregnancy and has been doing well, it would be prudent to continue with that same antidepressant after delivery, as switching to another antidepressant may put her at increased risk for relapse.

We do not regularly measure drug levels in the breastfeeding mother or baby; however, there may be certain situations where information on exposure to drug in the child may help make decisions regarding treatment. If there is a significant change in the child’s behavior (e.g., irritability, sedation, feeding problems, or sleep disturbance), an infant serum drug level may be obtained. If levels are high, breastfeeding may be suspended. Similarly if the mother is taking a particularly high dosage of medication, it may be helpful to measure drug levels in the infant to determine the degree of exposure.

Anti-Anxiety Agents

Given the prevalence of anxiety symptoms during the postpartum period, anxiolytic agents are often used in this setting. Data regarding the use of benzodiazepines have been limited; however, the available data suggest that amounts of medication to which the nursing infant is exposed are low. Case reports of sedation, poor feeding, and respiratory distress in nursing infants have been published; however, the data, when pooled, suggest a relatively low incidence of adverse events in infants exposed to benzodiazepines in the breast milk.

Mood Stabilizers

For women with bipolar disorder, breastfeeding may pose more significant challenges. First, on-demand breastfeeding may significantly disrupt the mother’s sleep and thus may increase her vulnerability to relapse during the acute postpartum period. Second, there have been reports of toxicity in nursing infants related to exposure to various mood stabilizers, including lithium and carbamazepine, in breast milk.

Lithium is excreted at relatively high levels in the mother’s milk, and infant serum levels are about one-third to one-half of the mother’s serum levels. Reported signs of toxicity in nursing infants have included cyanosis, hypotonia, and hypothermia. Although breastfeeding typically is avoided in women taking lithium, some women may choose to use lithium while nursing. In this setting, the lowest possible effective dosage should be used and both maternal and infant serum lithium levels should be followed. In collaboration with the pediatrician, the child should be monitored closely for signs of lithium toxicity, and lithium levels, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and creatinine should be monitored every 6-8 weeks while the child is nursing.

Several recent studies have suggested that lamotrigine reaches infants through breast milk in variable doses, with infant serum levels ranging from 20%-50% of the mother’s serum concentrations. In addition, maternal serum levels of lamotrigine increase significantly after delivery, which may contribute to the high levels found in nursing infants. None of these studies have reported any adverse events in breastfeeding newborns. To read more on the safety of lamotrigine versus lithium, please reference this past blog.

None of these studies have reported any adverse events in breastfeeding newborns. To read more on the safety of lamotrigine versus lithium, please reference this past blog.

One worry shared by clinicians and new mothers is the risk for Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). This is a severe, potentially life-threatening rash, most commonly resulting from a hypersensitivity reaction to a medication, which occurs in about 0.1% of bipolar patients treated with lamotrigine. Thus far, there have been no reports of SJS in infants associated with exposure to lamotrigine. In fact, it appears that cases of drug-induced SJS are extremely rare in newborns. Despite the variable levels of medication found in infants in studies to date, none of these studies have reported any adverse events in the breastfeeding newborns. More research is required to assess the safety of lamotrigine in nursing infants, and decisions regarding the use of this drug in breastfeeding women involves a careful consideration of the risks and benefits of using this medication.

Although the American Academy of Pediatrics has deemed both carbamazepine (Tegretol) and valproic acid (Depakote) to be appropriate for use in breastfeeding mothers, few studies have assessed the impact of these agents on infant well-being. Both of these mood stabilizers have been associated in adults with abnormalities in liver function and fatal hepatotoxicity. Hepatic dysfunction secondary to carbamazepine exposure in breast milk has been reported several times. Most concerning is that the risk for hepatotoxicity appears to be greatest in children younger than 2 years of age; thus, nursing infants exposed to these agents may be particularly vulnerable to serious adverse events. In those women who choose to use valproic acid or carbamazepine while nursing, routine monitoring of drug levels and liver function tests in the infant is recommended. In this setting, ongoing collaboration with the child’s pediatrician is crucial.

Antipsychotic Agents

Information regarding the use of antipsychotic drugs is limited and is particularly lacking for the newer atypical agents. While the use of chlorpromazine has been associated with adverse events including sedation and developmental delay, adverse events appear to be rare when medium- or high-potency agents are used.

While the use of chlorpromazine has been associated with adverse events including sedation and developmental delay, adverse events appear to be rare when medium- or high-potency agents are used.

Less data, however, is available on the atypical antipsychotic agents. Data on clozapine suggest that it may be concentrated in the breast milk; however, there are no data on infant serum levels, making it difficult to interpret the relevance of this finding. Given the severity of adverse events associated with clozapine exposure in adults (i.e., decreased white blood cell count), the use of this medication should be reserved for those with treatment-refractory illness, and monitoring of white blood cell counts in the nursing infant is mandatory.

There is very limited data on the use of other atypical antipsychotic agents during lactation; however, limited data available on olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine suggest that the excretion of these medications in breast milk is low and that adverse effects appear to be rare. Monitoring of the infant is encouraged, as there has been one report of an infant who had sedation on a higher dose of olanzapine, which resolved after the mother’s dose was halved to 5mg/day. To date, there have been no reports on the use of the antipsychotic medications, ziprasidone (Geodon) and aripiprazole (Abilify) while breastfeeding.

Monitoring of the infant is encouraged, as there has been one report of an infant who had sedation on a higher dose of olanzapine, which resolved after the mother’s dose was halved to 5mg/day. To date, there have been no reports on the use of the antipsychotic medications, ziprasidone (Geodon) and aripiprazole (Abilify) while breastfeeding.

Treatment Guidelines

Consultations regarding the safety of psychiatric medications in breastfeeding women should include a discussion of the known benefits of breastfeeding to mother and infant and the possibility that exposure to medications in the breast milk may occur. Although routine assay of infant serum drug levels was recommended in earlier treatment guidelines, this procedure is probably not warranted; in most instances low or non-detectable infant serum drug levels will be evident and serious adverse side effects are rarely reported. This testing is indicated, however, if neonatal toxicity related to drug exposure is suspected. Infant serum monitoring is also indicated when the mother is nursing while taking lithium, valproic acid, carbamazepine, or clozapine.

Infant serum monitoring is also indicated when the mother is nursing while taking lithium, valproic acid, carbamazepine, or clozapine.

We have varying amounts of study pertaining to individual medications, with SSRIs being among the best studied medications in breastfeeding. Also, data that is available informs most specifically on the short-term safety of these medications, and long term systematic data are unavailable. Therefore, in each individual case, the known and unknown risks of exposure must be balanced with the risks of untreated maternal illness in the mother and her desire to breastfeed.

For the latest information on breastfeeding and psychiatric medication, please visit our blog.

How do I get an appointment?

Despite the high rate of postpartum depression seen in women after childbirth, the illness is frequently not treated because of women’s wish to breastfeed. Clinical consultation is offered to women who may benefit from use of medication while breastfeeding, taking into account all available information regarding the safety of this practice during lactation. Consultations regarding treatment options can be scheduled by calling our intake coordinator at 617-724-7792.

Consultations regarding treatment options can be scheduled by calling our intake coordinator at 617-724-7792.

At this time the Center does not have any active studies investigating breastfeeding and psychiatric medications. New studies may become active in the near future. In order to remain informed about any studies for which you may be eligible, click here

Antidepressant Use in the Breastfeeding Patient

US Pharm. 2021;46(5):17-22.

ABSTRACT: It is well known that the peripartum period carries an increased risk of psychiatric disorders in the mother, and treatment is often necessary; however, given concerns about medication exposure in infants, uncertainty exists on how to safely manage treatment in breastfeeding patients with psychiatric illnesses. Additionally, the impact of the drug on milk production should be considered. However, pharmacologic treatment is not always incompatible with breastfeeding. As patients and providers may seek information on the use of antidepressants and other psychotropics while breastfeeding, pharmacists must consult current resources to keep abreast of risks, benefits, and treatment guidelines. By optimizing care for breastfeeding patients, pharmacists can help prevent adverse outcomes in both mother and baby.

By optimizing care for breastfeeding patients, pharmacists can help prevent adverse outcomes in both mother and baby.

It is well known that the first few months postpartum carry an increased risk of onset or worsening of mental illness in the mother. Mental-health conditions that may be experienced during this period include depressive and anxiety disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, eating disorders, and (more rarely) psychotic disorders.1 Major risk factors for the development of depressive and anxiety disorders in the peripartum period include a history of psychiatric illness, an insufficient support network, and prior adverse life events. Additionally, during the postpartum period, several other elements may contribute to the onset or worsening of mental disorders, including reduced quality and quantity of sleep, postpartum hormonal fluctuations, and genetic factors.1 Many women choose to breastfeed, resulting in the necessity to address the safety of psychotropics use with regard to infant exposure. This article will chiefly discuss the use of antidepressants in breastfeeding women.

This article will chiefly discuss the use of antidepressants in breastfeeding women.

It is recommended that breastfeeding women with milder psychiatric symptoms engage in lower-risk treatment such as psychological interventions; however, those with more severe symptoms may require pharmacologic treatment.1 As with any clinical decision, the risks and benefits of continuing or initiating a medication should be carefully weighed against the risks and benefits of discontinuing or avoiding medications during breastfeeding.

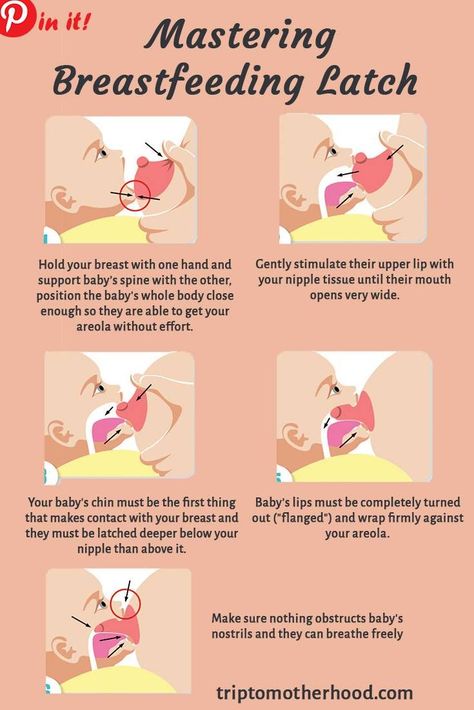

Although breastfeeding is generally recommended for its benefits to the baby, many women experience challenges with latching, milk supply, and sleep disruption, so these factors should be assessed in order to limit resultant distress.1,2 If sleep disruption caused by late-night breastfeeding sessions is having a significant negative impact on psychiatric symptoms, a discussion could be initiated about switching to formula feeding at night or pumping breast milk so that the partner or spouse can handle nighttime feedings. 1 A patient already taking an antidepressant may either choose to continue it and switch to formula feeding if adverse effects (AEs) on the newborn become a concern or opt to forego the medication and try nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy. It is important to recognize, however, that pharmacologic treatment is not always incompatible with breastfeeding.

1 A patient already taking an antidepressant may either choose to continue it and switch to formula feeding if adverse effects (AEs) on the newborn become a concern or opt to forego the medication and try nonpharmacologic treatments, such as psychotherapy. It is important to recognize, however, that pharmacologic treatment is not always incompatible with breastfeeding.

The risks of remaining on medications while breastfeeding vary, but the main risks related to switching or discontinuing pharmacologic treatment during this period involve suboptimal outcomes including relapse, uncontrolled psychiatric symptoms, and adverse outcomes such as death from suicide.3 The patient’s mental-illness history, including symptom severity, history of suicidality, and history of impaired quality of life due to symptoms, should be considered. It should be kept in mind that untreated maternal mental illness can also affect the infant if it impairs the mother’s ability to take care of the child properly or—in more severe cases—results in direct harm to the child. Additionally, the potential impact of the drug on milk production should be considered.

Additionally, the potential impact of the drug on milk production should be considered.

Finally, the infant’s age must be taken into account. Hepatic functionality is still developing at age 3 to 6 months, so babies of this age may be unable to efficiently metabolize any medications they are exposed to via breast milk, which may result in elevated plasma concentrations beyond what is anticipated. This decreased ability to metabolize drugs may be even more pronounced in preterm infants.4 Another consideration is whether the infant is taking any medications, as there may be interactions between the infant’s medications and the mother’s. Finally, the amount of milk the infant is consuming may also impact treatment decisions because, compared with partially breastfed infants, an exclusively breastfed infant is at higher risk for medication exposure. These factors must be considered on a case-by-case basis, with the healthcare team and the patient engaging in shared decision making. Breastfed infants of mothers who continue a medication from pregnancy into the postpartum period may be less likely to experience neonatal adaptation compared with formula-fed infants.5 Treatment goals for postpartum psychiatric disorders are to reduce the psychiatric symptoms and support the relationship between mother, child, and family unit.1

Breastfed infants of mothers who continue a medication from pregnancy into the postpartum period may be less likely to experience neonatal adaptation compared with formula-fed infants.5 Treatment goals for postpartum psychiatric disorders are to reduce the psychiatric symptoms and support the relationship between mother, child, and family unit.1

To estimate an infant’s potential exposure to medication during breastfeeding, the milk-to-plasma (M/P) concentration ratio is often used. The most common cutoff point for concern over drug accumulation in breast milk is when the M/P ratio exceeds 1.6 Another way to measure exposure is the relative infant dose (RID) or percent maternal dose, which is calculated by dividing the mg/kg/day ingested via breast milk by the mg/kg/day maternal dose. It is generally accepted that an RID of 10% or more of the maternal dose is clinically significant and potentially concerning.7-9

Drug Passage Into Breast MilkMultiple factors can affect a medication’s ability to pass into breast milk. 9,10 For example, in the first 3 days postpartum, spaces between the mammary epithelial cells allow larger molecules to penetrate the milk. The amount of drug that the newborn may be exposed to during this time is limited owing to the small volume consumed.9,10 Following this phase, milk production increases, and the spaces between the mammary epithelial cells close over a 1- to 2-week period. Subsequently, medications are able to penetrate breast milk primarily by passive diffusion across the mammary epithelium, which acts as a semipermeable lipid barrier. An exception occurs in the event of maternal infections such as mastitis, wherein the passage of drug molecules may generally increase and larger molecules again may be able to pass through.10

9,10 For example, in the first 3 days postpartum, spaces between the mammary epithelial cells allow larger molecules to penetrate the milk. The amount of drug that the newborn may be exposed to during this time is limited owing to the small volume consumed.9,10 Following this phase, milk production increases, and the spaces between the mammary epithelial cells close over a 1- to 2-week period. Subsequently, medications are able to penetrate breast milk primarily by passive diffusion across the mammary epithelium, which acts as a semipermeable lipid barrier. An exception occurs in the event of maternal infections such as mastitis, wherein the passage of drug molecules may generally increase and larger molecules again may be able to pass through.10

The rate of passage from maternal plasma into breast milk is determined both by medication lipid solubility and by molecular weight, with smaller-molecular-weight molecules having increased passage. Psychotropic drugs are generally lipophilic, which permits them to dissolve in the mammary epithelial cell membrane and pass more easily into breast milk. It also allows the drug to concentrate in the milk fat, which ranges from 10% in hindmilk to 2% to 3% in foremilk.9,10

It also allows the drug to concentrate in the milk fat, which ranges from 10% in hindmilk to 2% to 3% in foremilk.9,10

Medications that enter the milk compartment quickly will achieve a greater initial concentration, resulting in a higher M/P ratio. Those that enter the milk compartment slowly may not achieve concentrations as high as those in the maternal plasma, as the compartment is emptied at each nursing session, thus requiring new transport of the drug.9,10

Protein-binding also has an impact on medication passage into breast milk, as highly protein-bound drugs are less able to penetrate the milk compartment.9,10 Additionally, the drug’s pH has an effect on passage into breast milk. According to the pH partition theory, ionized forms of weak bases concentrate in the milk, whereas weak acids are trapped in the plasma.9 To summarize, the ideal medication for passing into breast milk is nonionized and has a lower molecular weight, high lipophilicity, low protein-binding, and high pKa. (pKa, the negative log of the acid dissociation constant Ka, expresses the acidity of a weak acid, whereas a lower pKa denotes a stronger acid.9,10)

(pKa, the negative log of the acid dissociation constant Ka, expresses the acidity of a weak acid, whereas a lower pKa denotes a stronger acid.9,10)

All antidepressants pass into the breast milk to some degree.2 Therefore, clinical-treatment guidelines for depression in postpartum breastfeeding mothers often recommend psychotherapy first-line, with second-line therapy including agents such as citalopram, escitalopram, and sertraline.2,11 Other options may be considered in patients who have responded well to other agents in the past. In a pooled analysis of antidepressant concentrations in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants, infants who were exposed to nortriptyline, paroxetine, or sertraline were least likely to have detectable or elevated serum drug concentrations (>10% of maternal level).8 In the same analysis, citalopram or fluoxetine use in a nursing mother often resulted in elevated serum drug concentrations in the infant. 8

8

Although citalopram use sometimes leads to elevated serum drug concentrations in the infant that are beyond the 10% threshold, the reported AEs for infants are relatively mild and include drowsiness, weight loss, restlessness, irritability, and uneasy sleep.5 Neonatal adaptation syndrome and withdrawal effects from citalopram have also been reported, including irregular breathing, apnea, disordered sleep, and hypotonia.12

Case reports have identified potential AEs associated with fluoxetine during breastfeeding, including fussiness, drowsiness, and impaired infant weight gain.5 For this reason and because of the higher concentrations in infant serum, it is often recommended that an antidepressant with less excretion into the milk compartment be used when feasible.

Although escitalopram passes into breast milk only in low concentrations, there have been a few cases of AEs, including irritability, in nursing infants.5 There has been a single case report of necrotizing enterocolitis in an infant exposed to escitalopram via breast milk, but causality was not determined. 13 Additionally, in one report, seizure activity occurred in an infant exposed to both escitalopram and bupropion via breast milk, but this was thought to be related to the bupropion exposure.14

13 Additionally, in one report, seizure activity occurred in an infant exposed to both escitalopram and bupropion via breast milk, but this was thought to be related to the bupropion exposure.14

Because sertraline passes into breast milk in low concentrations, it is considered a preferred agent for breastfeeding women.2,10 AEs in breastfed infants exposed to sertraline are rare, but diarrhea, drowsiness, restlessness, insomnia, and poor neonatal adaptation have been noted.5 In one case report, an infant exposed to sertraline via breast milk who was later determined to have genetic polymorphisms of the CYP450 enzymes involved in sertraline metabolism experienced hyperthermia, alterations in muscle tone, and high-pitched crying related to elevated sertraline concentrations.15 This case illustrates that medications can affect all infants slightly differently owing to individual characteristics.

Paroxetine is not recommended in pregnancy based on the risk of cardiovascular malformations if used in the first trimester; however, because it has been shown to pass into breast milk only in low concentrations, it may be more acceptable for use during lactation. 8 AEs in nursing infants exposed to paroxetine through breast milk are rare and generally mild; restlessness, constipation, insomnia, poor neonatal adaptation, alertness, agitation, and poor feeding have been reported.5

8 AEs in nursing infants exposed to paroxetine through breast milk are rare and generally mild; restlessness, constipation, insomnia, poor neonatal adaptation, alertness, agitation, and poor feeding have been reported.5

Venlafaxine and its active metabolite have been shown to pass into breast milk in higher concentrations (M/P ratio >1).16 The literature notes several cases of suspected withdrawal in breastfeeding newborns whose mothers were taking venlafaxine during pregnancy and postpartum.5

Not much literature is available on nursing mothers taking mirtazapine, but there is one report of infant restlessness in a breastfeeding mother who was taking both mirtazapine and paroxetine.5,17 Similarly, few studies exist on bupropion use in breastfeeding women; however, two cases of seizures in infants exposed to bupropion via breast milk have been reported.14,18 There are no published reports on mother and nursing infant pairs for newer antidepressants such as vortioxetine and vilazodone, so little is known about their effects; therefore, it may be best for patients who are planning to breastfeed to opt for an alternative agent. 5

5

One important factor to consider regarding medication use during breastfeeding is the agent’s impact on milk production. It has been observed that increases in serotonin levels cause early involution of mammary glands, thereby reducing milk production, which has led to theoretical concerns about milk supply in nursing mothers taking antidepressants with serotonergic properties.19 Additionally, postmarketing reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have identified proposed “dopamine-dependent” AEs that may affect milk production, such as galactorrhea, mammary-gland hypertrophy, and hyperprolactinemia.20 However, in a retrospective cohort study that used the galactogogue domperidone as a marker of low milk supply, no association was found between late-pregnancy serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) use and domperidone use, indicating that SRIs do not adversely affect milk supply.19

Resources for Drugs in LactationSeveral rating scales exist for determining risks of medications used in lactation. The most widely used resources include Briggs and colleagues’ Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation, which rates drugs according to seven risk categories, and Hale’s Medications and Mothers’ Milk, which uses five lactation-risk categories.9,21,22 Categories range from “contraindicated in breastfeeding” to “compatible/safest,” which is reserved for agents that have been studied in breastfeeding humans and have not demonstrated any AEs in infants.9,21 Uguz recently proposed a third scoring system specifically for psychotropic medications that rates each agent on a 10-point scale incorporating data on six items: reported total sample, reported maximum RID, reported sample size for RID, infant plasma drug concentrations, prevalence of observed AEs, and reported serious AEs.22

The most widely used resources include Briggs and colleagues’ Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation, which rates drugs according to seven risk categories, and Hale’s Medications and Mothers’ Milk, which uses five lactation-risk categories.9,21,22 Categories range from “contraindicated in breastfeeding” to “compatible/safest,” which is reserved for agents that have been studied in breastfeeding humans and have not demonstrated any AEs in infants.9,21 Uguz recently proposed a third scoring system specifically for psychotropic medications that rates each agent on a 10-point scale incorporating data on six items: reported total sample, reported maximum RID, reported sample size for RID, infant plasma drug concentrations, prevalence of observed AEs, and reported serious AEs.22

Although these categorical ratings are important to keep in mind and may be a good starting point for researching the effects of medications during breastfeeding, more in-depth resources should be consulted in order to fully inform clinical decisions. Other resources include the drug’s package insert (PI), the LactMed online database, MotherToBaby, and the InfantRisk Center.5,23,24 Each PI contains a lactation section organized into three distinct topics: risk summary, clinical considerations, and data. LactMed, which is maintained by the National Library of Medicine, includes information on medication concentrations in breast milk as well as summaries of AEs noted in the literature and any effects on milk production.5 MotherToBaby is a telephone- and Web-based service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists that is available to both patients and healthcare providers.23 The InfantRisk Center, a global call center located at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, helps providers and patients evaluate the risk of multiple drug exposure to the infant.24

Other resources include the drug’s package insert (PI), the LactMed online database, MotherToBaby, and the InfantRisk Center.5,23,24 Each PI contains a lactation section organized into three distinct topics: risk summary, clinical considerations, and data. LactMed, which is maintained by the National Library of Medicine, includes information on medication concentrations in breast milk as well as summaries of AEs noted in the literature and any effects on milk production.5 MotherToBaby is a telephone- and Web-based service of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists that is available to both patients and healthcare providers.23 The InfantRisk Center, a global call center located at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, helps providers and patients evaluate the risk of multiple drug exposure to the infant.24

During the postpartum period, mothers may be seeking information regarding the compatibility of their medications with lactation. Likewise, patients’ healthcare providers may seek input from the pharmacist on this issue. Although many resources are available, much remains unknown about the passage of specific drugs into breast milk and about related AEs. In determining the safety of any medication in a breastfeeding woman, it is important for the pharmacist to keep in mind that there are essentially two patients: the mother and the infant. Information gathered should include not only the mother’s health conditions and current medications, including indications, dosing, and anticipated duration of therapy, but also the infant’s age, weight, preterm/term status, current health conditions, current medications, and percentage of breast milk in the diet.22 The use of evidence-based resources will help the pharmacist evaluate and share the most up-to-date information regarding medication use in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding women who are thinking about discontinuing maintenance antidepressant therapy should be encouraged to discuss their concerns with the prescriber in order to avoid any risk of relapse, withdrawal, or other unintended harmful effects.

Likewise, patients’ healthcare providers may seek input from the pharmacist on this issue. Although many resources are available, much remains unknown about the passage of specific drugs into breast milk and about related AEs. In determining the safety of any medication in a breastfeeding woman, it is important for the pharmacist to keep in mind that there are essentially two patients: the mother and the infant. Information gathered should include not only the mother’s health conditions and current medications, including indications, dosing, and anticipated duration of therapy, but also the infant’s age, weight, preterm/term status, current health conditions, current medications, and percentage of breast milk in the diet.22 The use of evidence-based resources will help the pharmacist evaluate and share the most up-to-date information regarding medication use in breastfeeding. Breastfeeding women who are thinking about discontinuing maintenance antidepressant therapy should be encouraged to discuss their concerns with the prescriber in order to avoid any risk of relapse, withdrawal, or other unintended harmful effects.

1. Meltzer-Brody S, Howard LM, Bergink V, et al. Postpartum psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18022.

2. Sriraman NK, Melvin K, Meltzer-Brody S. ABM clinical protocol #18: use of antidepressants in breastfeeding mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2015;10(6):290-299.

3. Johannsen BM, Larsen JT, Laursen TM, et al. All-cause mortality in women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(6):635-642.

4. Berle JØ, Spigset O. Antidepressant use during breastfeeding. Curr Womens Health Rev. 2011;7(1):28-34.

5. Drugs and lactation database (LactMed) [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2021. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/. Accessed April 2, 2021.

6. Ito S. Mother and child: medication use in pregnancy and lactation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100(1):8-11.

7. Sachs HC, Committee on Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e796-e809.

8. Weissman AM, Levy BT, Hartz AJ, et al. Pooled analysis of antidepressant levels in lactating mothers, breast milk, and nursing infants. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):1066-1078.

9. Berens PD, Hale TW. Principles of drug therapy in pregnancy and lactation. In: O’Connell MB, Smith JA, eds. Women’s Health Across the Lifespan: A Pharmacotherapeutic Approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2019.

10. Anderson PO, Sauberan JB. Modeling drug passage into human milk. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;100(1):42-52.

11. MacQueen GM, Frey BN, Ismail Z, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 6. Special populations: youth, women, and the elderly. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(9):588-603.

12. Franssen EJF, Meijs V, Ettaher F, et al. Citalopram serum and milk levels in mother and infant during lactation. Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(1):2-4.

Ther Drug Monit. 2006;28(1):2-4.

13. Potts AL, Young KL, Carter BS, Shenal JP. Necrotizing enterocolitis associated with in utero and breast milk exposure to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, escitalopram. J Perinatol. 2007;27(2):120-122.

14. Neuman G, Colantonio D, Delaney S, et al. Bupropion and escitalopram during lactation. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(7):928-931.

15. Müller MJ, Preuss C, Paul T, et al. Serotonergic overstimulation in a preterm infant after sertraline intake via breastmilk. Breastfeed Med. 2013;8(3):327-329.

16. Schoretsanitis G, Augustin M, Sassmannshausen H, et al. Antidepressants in breastmilk; comparative analysis of excretion ratios. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2019;22(3):383-390.

17. Uguz F. Short-term safety of paroxetine plus low-dose mirtazapine during lactation. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(2):131-132.

18. Chaudron LH, Schoenecker CJ. Bupropion and breastfeeding: a case of a possible infant seizure. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(6):881-882.

J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(6):881-882.

19. Grzeskowiak LE, Leggett C, Costi L, et al. Impact of serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on breast milk supply in mothers of preterm infants: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(6):1373-1379.

20. Damsa C, Bumb A, Bianchi-Demicheli F, et al. “Dopamine-dependent” side effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a clinical review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1064-1068.

21. Instructions for use of the reference guide. In: Briggs GC, Freeman RK, Towers CV, Forinash AB, eds. Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: a Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

22. Uguz F. A new safety scoring system for the use of psychotropic drugs during lactation. Am J Ther. 2021;28(1):e118-e126.

23. MotherToBaby. Is it safe for me and my baby? https://mothertobaby.org/. Accessed February 28, 2021.

24. InfantRisk Center. About the InfantRisk Center. www.infantrisk.com/about-infantrisk-center. Accessed February 28, 2021.

About the InfantRisk Center. www.infantrisk.com/about-infantrisk-center. Accessed February 28, 2021.

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

To comment on this article, contact [email protected].

Can I take antidepressants while breastfeeding? - Empathy

At the beginning of August, WHO initiated the Breastfeeding Support Week around the world, the purpose of which is to remind women about the benefits of natural breastfeeding. We will touch upon such an urgent issue as the treatment of depression in nursing mothers.

Is it safe to take antidepressants while breastfeeding? Should breastfeeding mothers stop taking drugs? nine0006 The Deputy Chief Physician of the Empathy Center, Candidate of Medical Sciences, psychiatrist Irina Valerievna Gorshkova answers:

“The desire to continue breastfeeding is often the main reason women refuse to see a psychiatrist. This is not at all surprising, because the instructions for prescribed drugs may indicate that there is no data on their safety for nursing mothers, or it is written that the drug passes into breast milk. In this regard, there is often an opinion that taking antidepressants by a young mother is not safe for a child. However, this statement can be disputed. nine0003

This is not at all surprising, because the instructions for prescribed drugs may indicate that there is no data on their safety for nursing mothers, or it is written that the drug passes into breast milk. In this regard, there is often an opinion that taking antidepressants by a young mother is not safe for a child. However, this statement can be disputed. nine0003

For more than 10 years, studies have been conducted and published that prove the safety of using antidepressants during breastfeeding (mainly SSRIs). There are also many studies confirming the need to treat depression in a woman in the postpartum period, which directly affects the health of not only the mother, but also the baby. In simple terms, sometimes prescribing antidepressants while breastfeeding is a much smarter and safer decision than leaving a woman in a depressed state. nine0003

Breastfeeding is very important for the full development of the child, moreover, its beneficial effect on the health of both the baby and the mother has long been known. Therefore, unjustified cancellation of breastfeeding due to fear of antidepressants can negatively affect both the condition of the child and the psycho-emotional state of the woman, cause her to feel guilty and inferior.

Therefore, unjustified cancellation of breastfeeding due to fear of antidepressants can negatively affect both the condition of the child and the psycho-emotional state of the woman, cause her to feel guilty and inferior.

Prescribing antidepressants during breastfeeding is not only possible but necessary , provided that the doctor correlates the expected benefits and possible risks of taking the drug. And let's not forget that the treatment of depression involves not only medication, but also psychotherapy. With a mild degree of severity of a depressive episode, preference is given precisely to psychotherapeutic methods. Medication support is most often prescribed in combination with psychotherapy.”

How can we help?

nine0002 If you have found some of the described symptoms in yourself or your loved ones, this may indicate the development of a mental disorder. In this case, it is worth contacting a psychiatrist for diagnosis and initiation of timely treatment. In addition to face-to-face communication , we offer remote consultation service (online reception) , which is not inferior to a face-to-face meeting in terms of quality. Thus, you can get qualified help from a high-level specialist , no matter where you are located. nine0036 In addition to face-to-face communication , we offer remote consultation service (online reception) , which is not inferior to a face-to-face meeting in terms of quality. Thus, you can get qualified help from a high-level specialist , no matter where you are located. nine0036 |

In our center for mental health and psychological assistance, within walking distance from the Elektrozavodskaya metro station (Moscow) and the Novokosino metro station (Reutov), specialists who have extensive experience in treating mental disorders work. We use the most modern and advanced techniques, guided by the principles of evidence-based medicine. Effective assistance and confidentiality of information constituting a medical secret are guaranteed. nine0003

Antidepressant treatment for pregnant and lactating mothers

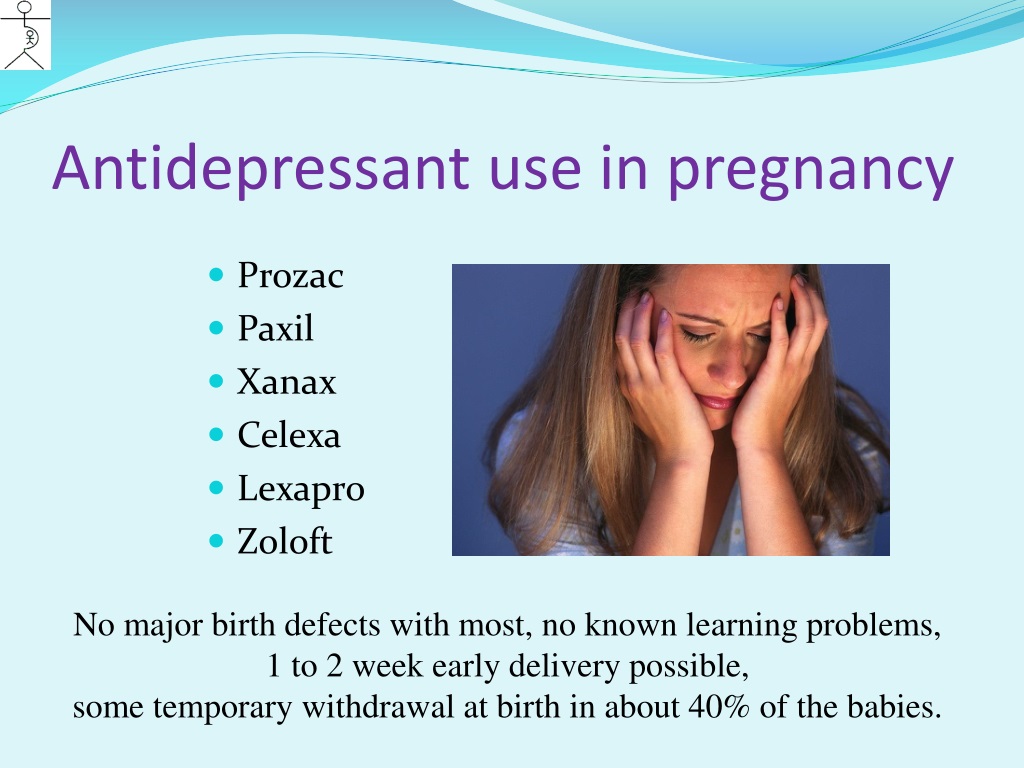

The potential risks of taking antidepressants during pregnancy and lactation have been much discussed recently. Some studies conclude that antidepressants increase the risk of birth defects. Proponents of antidepressants are careful to note that depression during pregnancy is also a risky condition, it can lead to premature birth and other troubles.

Some studies conclude that antidepressants increase the risk of birth defects. Proponents of antidepressants are careful to note that depression during pregnancy is also a risky condition, it can lead to premature birth and other troubles.

no fax cash advance loans

Professionals often decide on the treatment of certain drugs, carefully weighing both the possible benefits and possible risks. There are a number of antidepressants that can be used during pregnancy and lactation, but with some potential for side effects. In any case, the risk of prescribing the drug must be weighed against the effects of prolonged depression or the risks of not breastfeeding for mother and child. (Alternative treatments for depression are described in Non-Medication Treatments for Depression During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding.) Below is a brief overview of studies on how drugs reach and affect the baby during pregnancy and lactation. nine0003

Transfer of drugs to the baby during pregnancy and breastfeeding

The baby may receive various doses of drugs that the mother takes during pregnancy or breastfeeding. This is a review of the literature on the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). It will help you better understand what we know about the use of drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

This is a review of the literature on the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). It will help you better understand what we know about the use of drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Intrauterine exposure

During pregnancy, medicines pass to the baby through the placenta or through the amniotic fluid. The amount of the drug that the child will receive through the placenta is directly proportional to the dose that the mother takes. But the ability of drugs to cross the placental barrier is different, and one of the treatment strategies during pregnancy is the selection of drugs with the least ability to transfer to the fetus. For example, in an experiment with 38 pregnant women who were taking SSRIs, the concentration of antidepressants and metabolites in umbilical cord assays was 87%. Plasma level - from 0.29up to 0.89. Sertalizin (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil) had the lowest penetration, while citalopram (Celexa) and fluoxetine (Prozac) had the highest penetration (Data from Hendrick, 2003).

Regarding the ability of SSRIs to cause birth defects when taken during pregnancy, the Sloane Center for the Study of Birth Defect Epidemiology recently confirmed that the overall risk of having a baby using SSRIs is only 0.2% (Louik et al., 2007). They noted an increased risk of three birth defects with SSRIs in the first trimester of pregnancy: umbilical hernia and septal defects with sertraline, and right ventricular heart disease with paroxetine. But only 2% to 5% of all children born with these defects were exposed to SSRIs in utero. nine0003

Taking drugs in the third trimester may lead to discontinuation syndrome (withdrawal*) in newborns due to the withdrawal of SSRIs. The withdrawal syndrome includes acrocyanosis, apnea, temperature instability, irritability (Oberlander et al., 2004). Fortunately, these symptoms are usually mild, limited, and manageable with supportive infant care. Serious symptoms are rare, and there has not been a single reported case of neonatal death associated with intrauterine use of SSRIs. Withdrawal can be stressful for mother and baby, but symptoms are usually limited to 24-48 hours and do not require special treatment. nine0003

Withdrawal can be stressful for mother and baby, but symptoms are usually limited to 24-48 hours and do not require special treatment. nine0003

Exposure through breast milk

Antidepressants can pass to the baby through breast milk, but in much smaller amounts than in utero. Some drugs are more compatible with breastfeeding, while others pass into milk in higher concentrations.

A recent meta-analysis of 67 studies on the level of antidepressants given to a child with milk systematized 337 experimental cases, where 238 children were studied (Weissman et al., 2004). The study included 15 antidepressants. nine0003

Traces of all drugs were found in breast milk. Fluoxetine has been found in children at the highest concentration. The content of citalopram was also found to be quite high. Only one child in the various studies had an elevated paroxetine level and this child had previously been exposed to the drug in utero. All other infants had zero levels of paroxetine, including three other infants treated with paroxetine in utero.