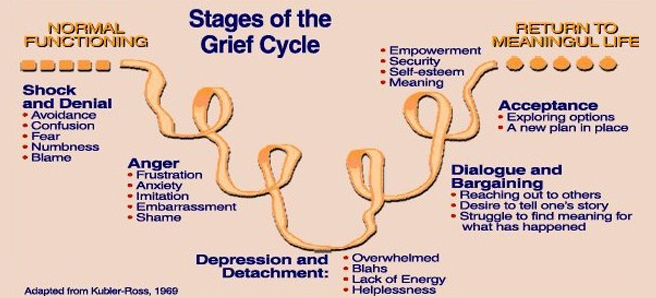

5 step grieving process

Five Stages of Grief by Elisabeth Kubler Ross & David Kessler

A Message from David Kessler

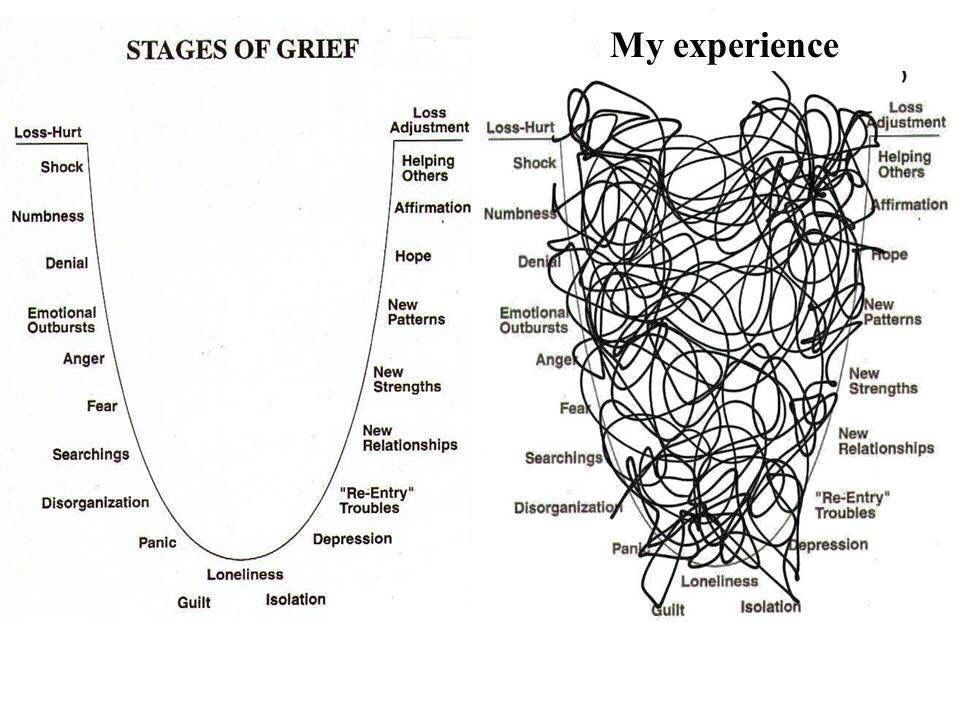

I was privileged to co-author two books with the legendary, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, as well as adapt her well-respected stages of dying for those in grief. As expected, the stages would present themselves differently in grief. In our book, On Grief and Grieving we present the adapted stages in the much needed area of grief. The stages have evolved since their introduction and have been very misunderstood over the past four decades. They were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss as there is no typical loss.

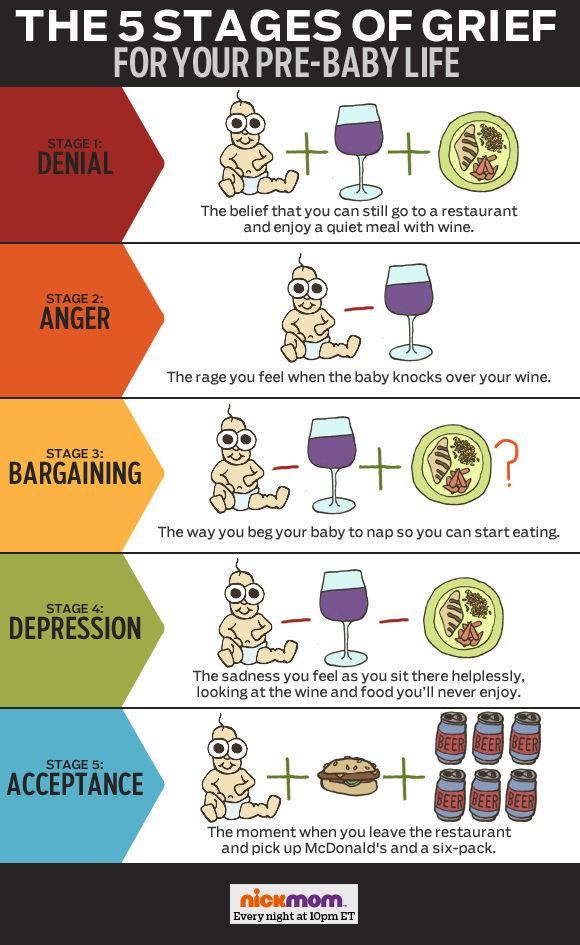

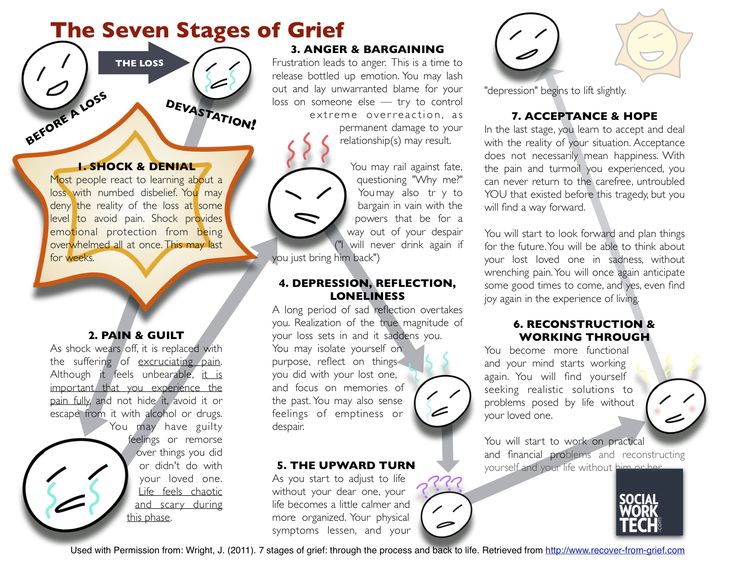

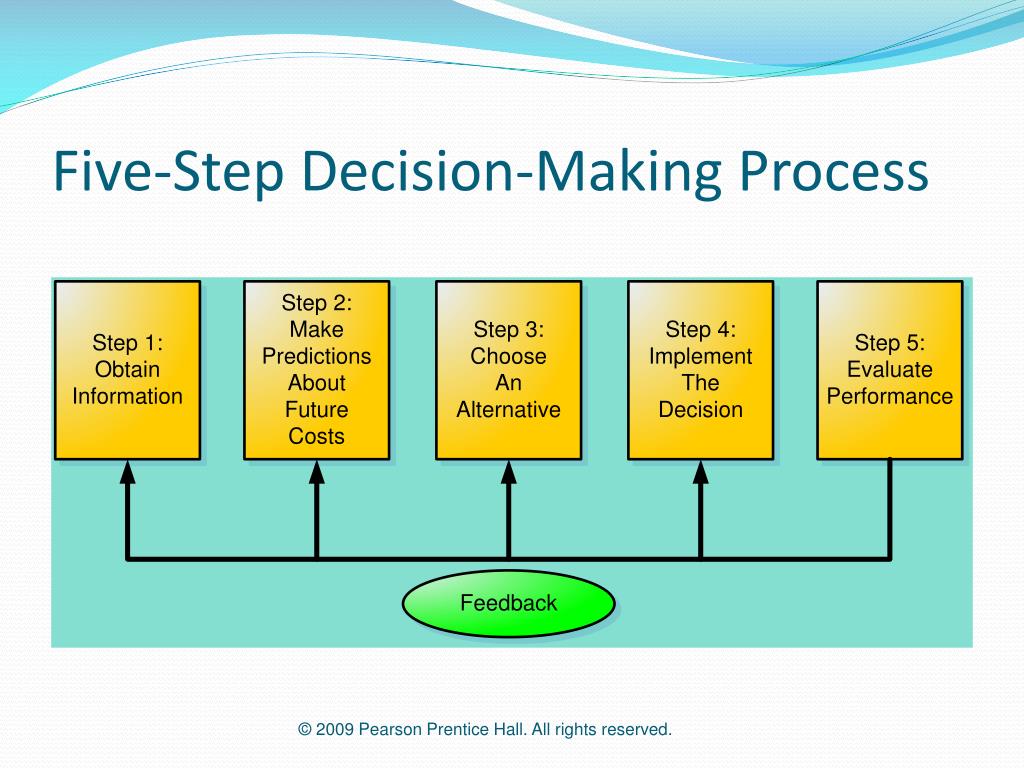

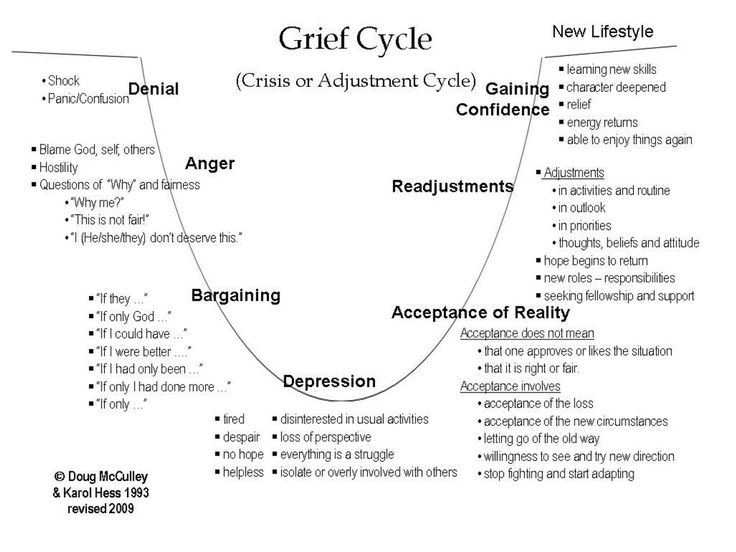

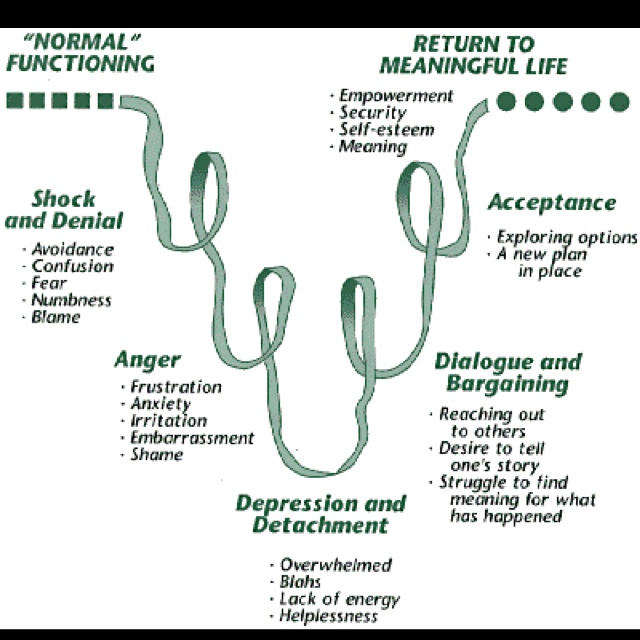

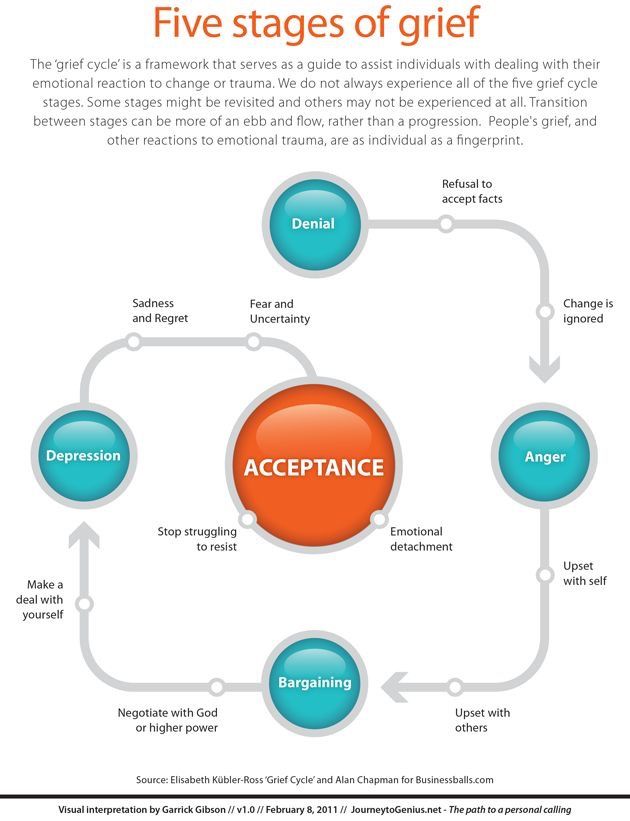

The five stages, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance are a part of the framework that makes up our learning to live with the one we lost. They are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief.

Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order. Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief ‘s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss. At times, people in grief will often report more stages. Just remember your grief is an unique as you are.

NEW BOOK

Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

In this groundbreaking new work, David Kessler—an expert on grief and the coauthor with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross of the iconic On Grief and Grieving—journeys beyond the classic five stages to discover a sixth stage: meaning.

In this book, Kessler gives readers a roadmap to remembering those who have died with more love than pain; he shows us how to move forward in a way that honors our loved ones. Kessler’s insight is both professional and intensely personal. His journey with grief began when, as a child, he witnessed a mass shooting at the same time his mother was dying. For most of his life, Kessler taught physicians, nurses, counselors, police, and first responders about end of life, trauma, and grief, as well as leading talks and retreats for those experiencing grief. Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

How does the grief expert handle such a tragic loss? He knew he had to find a way through this unexpected, devastating loss, a way that would honor his son. That, ultimately, was the sixth state of grief—meaning. In Finding Meaning, Kessler shares the insights, collective wisdom, and powerful tools that will help those experiencing loss. Read More

DENIAL Denial is the first of the five stages of grief™️. It helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle. As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

ANGERAnger is a necessary stage of the healing process. Be willing to feel your anger, even though it may seem endless. The more you truly feel it, the more it will begin to dissipate and the more you will heal. There are many other emotions under the anger and you will get to them in time, but anger is the emotion we are most used to managing. The truth is that anger has no limits. It can extend not only to your friends, the doctors, your family, yourself and your loved one who died, but also to God. You may ask, “Where is God in this? Underneath anger is pain, your pain. It is natural to feel deserted and abandoned, but we live in a society that fears anger. Anger is strength and it can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

BARGAININGBefore a loss, it seems like you will do anything if only your loved one would be spared. “Please God, ” you bargain, “I will never be angry at my wife again if you’ll just let her live.” After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others. Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream?” We become lost in a maze of “If only…” or “What if…” statements. We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

DEPRESSIONAfter bargaining, our attention moves squarely into the present. Empty feelings present themselves, and grief enters our lives on a deeper level, deeper than we ever imagined. This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

ACCEPTANCEAcceptance is often confused with the notion of being “all right” or “OK” with what has happened. This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies.

This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies. Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Learn More About The Five Areas of Grief

Watch The FREE Video Now Click Here

Books About the Five Stages by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler

Download Chapter One Click Here

Download Chapter One Click Here

The Stages of Grief: Accepting the Unacceptable

June 8, 2020

Posted by Caitlin Stanaway, Psy.D., Licensed Psychologist, UWCC

The pandemic has impacted our routines, social lives, school, work, and more. It has caused the loss of lives around the globe, as well as the loss of normalcy. The recent death of George Floyd has put police brutality, murders of Black and Brown people, racial and social injustice into the spotlight. There are many losses to grieve amidst the intensity of civil unrest, on top of more typical stressors like taking finals and looking for a job.

There are many losses to grieve amidst the intensity of civil unrest, on top of more typical stressors like taking finals and looking for a job.

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross developed the five stages of grief in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. Grief is typically conceptualized as a reaction to death, though it can occur anytime reality is not what we wanted, hoped for, or expected.

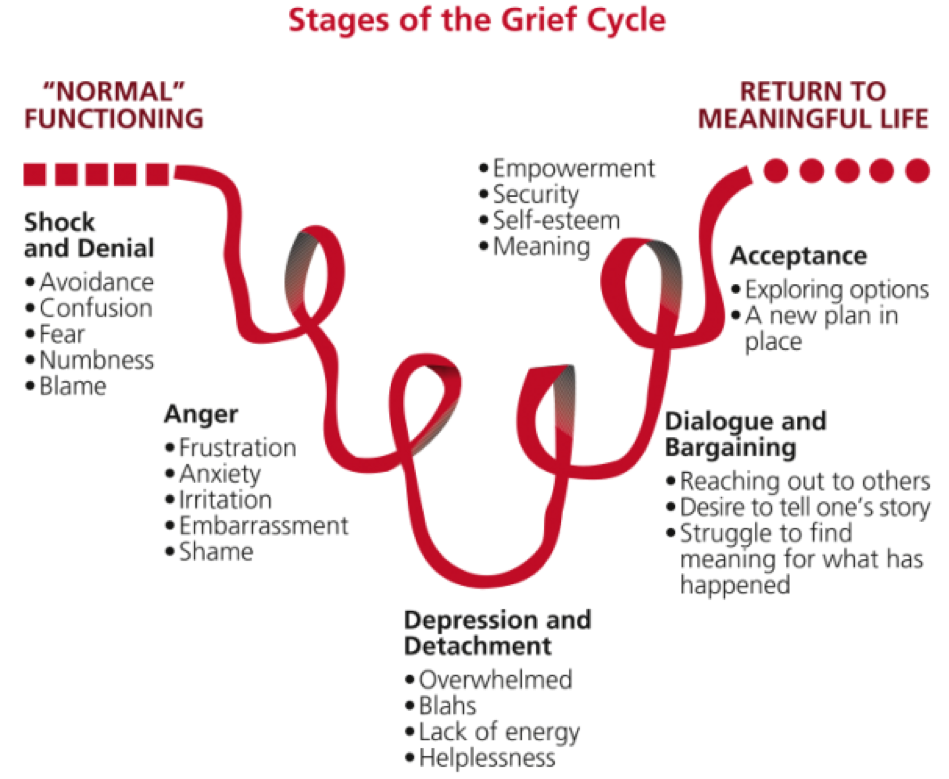

Persistent, traumatic grief can cause us to cycle (sometimes quickly) through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. These stages are our attempts to process change and protect ourselves while we adapt to a new reality. While there are consistent elements within each stage, the process of grieving looks different for everyone.

When you combine experiences of stress and trauma to grief, it is overwhelming. It takes a toll on our mental and physical health. Our minds and bodies are consistently being impacted by the stress response, a nervous system reaction to feeling threatened. It triggers the release of adrenaline and cortisol, impacting sleep, appetite, making it difficult to function at your best.

It triggers the release of adrenaline and cortisol, impacting sleep, appetite, making it difficult to function at your best.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression may develop, as well as trauma symptoms like intrusive thoughts, nightmares, feeling disconnected from self. Trauma related to racial injustice is chronic. Resources for Black healing, including crisis support, self-care, and reducing cortisol levels in response to racial stressors can be found here.

Being aware of the grief stages and how you uniquely experience them can increase self-understanding and compassion. It can help you better understand your needs and prioritize getting them met.

Denial

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| avoidance | shock |

| procrastination | numbness |

| forgetting | confusion |

| easily distracted | shutting down |

| mindless behaviors | |

| keeping busy all the time | |

| thinking/saying, “I’m fine” or “it’s fine” |

Anger

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| pessimism | frustration |

| cynicism | impatience |

| sarcasm | resentment |

| irritability | embarrassment |

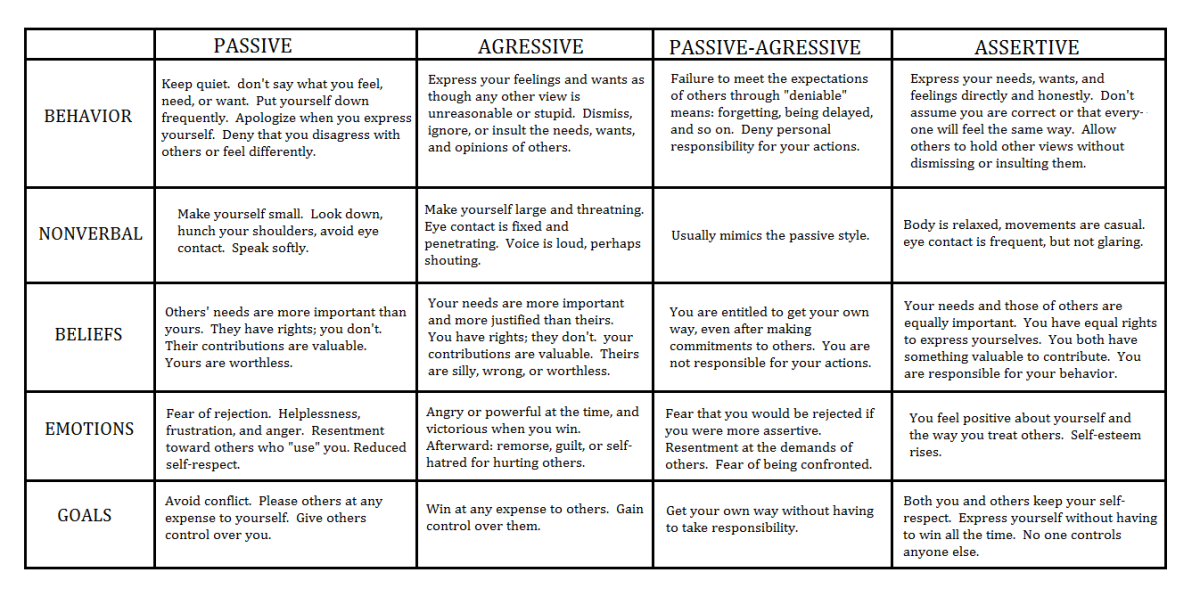

| being aggressive or passive-aggressive | rage |

| getting into arguments or physical fights | feeling out of control |

| increased alcohol or drug use |

Bargaining

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| ruminating on the future or past | guilt |

| over-thinking and worrying | shame |

| comparing self to others | blame |

| predicting the future and assuming the worst | fear, anxiety |

| perfectionism | insecurity |

| thinking/saying, “I should have…” or ”If only…” | |

| judgment toward self and/or others |

Depression

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| sleep and appetite changes | sadness |

| reduced energy | despair |

| reduced social interest | helplessness |

| reduced motivation | hopelessness |

| crying | disappointment |

| increased alcohol or drug use | overwhelmed |

Acceptance

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| mindful behaviors | “good enough” |

| engaging with reality as it is | courageous |

| “this is how it is right now” | validation |

| being present in the moment | self-compassion |

| able to be vulnerable & tolerate emotions | pride |

| assertive, non-defensive, honest communication | wisdom |

| adapting, coping, responding skillfully |

Generally, if we are not in the stage of acceptance then we are in some way fighting against or avoiding reality. We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

Acceptance doesn’t mean not experiencing distress, emotions or trauma. It does not mean you condone what is happening. It means noticing what you are fighting against, validating your desire to fight against it, and re-orienting yourself to the reality of the moment you are in. It means not getting stuck, or getting un-stuck, from other stages. Mindfulness and a non-judgmental, curious attitude can be a big help.

Acceptance might look like saying to yourself: “If I sleep too long today I’ll keep sleeping through the mornings. I’m going to prioritize getting my schedule regulated.” It might look like noticing: “I’m directing my anger and sadness about what’s going on toward myself and ruminating on self-criticisms. I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

It is rare to move through the stages in a linear way. It is normal to experience ups and downs in mood, thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. It can be difficult maintaining acceptance while things feel so unacceptable.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by grief, loss, trauma you do not have to go through it alone. The Counseling Center can offer culturally-sensitive support and guidance through the grieving process.

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a workshop with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption,Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

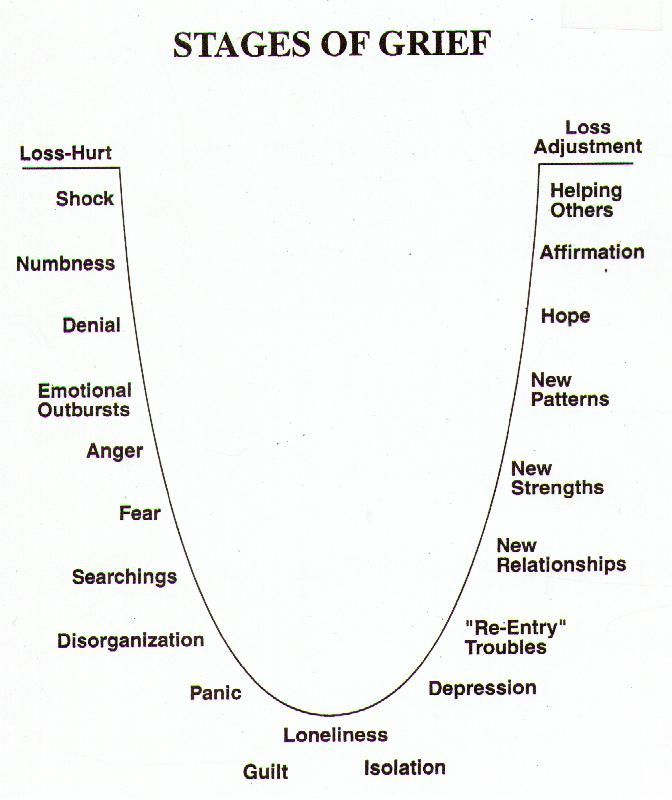

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief. ” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

Five stages of grief - truth or myth?

- Claudia Hammond

- BBC Future

Denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance. Is it true that a person experiencing the pain of loss goes through certain stages? Let's look at the research data.

image copyrightMilan Popovic / Unsplash

"Tosca is a place we don't know until we've been there ourselves. We realize that loved ones can die, but we don't know exactly what awaits us in the first days and weeks after losses".

These are the words of the American writer Joan Didion, who described her feelings in the first year after the death of her husband in an extremely emotional confession "The Year of Magical Thinking".

The theory of the five stages of grief - denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance - is firmly rooted in popular culture.

Articles are written about her and remembered in serials, and the artist Damien Hirst created a series of paintings, calling them the acronym "DABDA" (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance).

How long each stage lasts is not specified, but it is believed that all of them must pass in a certain sequence.

- Regular exercise saves you from depression.

But not always

But not always - How hormones, immunity, microbes and pulse affect our character

- How parents' quarrels affect children's health

The concept of the stages of mourning originated in research conducted in the 1960s by psychologists John Bowlby (who also studied children's affection for parents) and Colin Murray-Parks.

Researchers interviewed 22 widows and identified four stages of grief: numbness, searching and longing, depression and rethinking.

The modern classification was developed by psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who worked with terminally ill patients and asked about their near-death experiences.

Kubler-Ross, by the way, radically changed the attitude towards palliative care and raised the question of the doctor's responsibility not only for the health of patients, but also for how they live their last days.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,How does a terminally ill person feel?

Skip the podcast and continue

podcast

What did it cost

The main story of today, how our journalists explain

Releases

End podcast

However, the concept of five stages of grief did not pass the system test, and only in the early 2000s did Yale University researchers first tackle this topic.

Over the course of three years, they interviewed 233 bereaved people (usually a wife or husband). The interviews were conducted approximately six, eleven and nineteen months after death.

The researchers did not look at cases of violent death of a relative or complex grief reactions.

The picture they got was more complex than the five-stage hypothesis. The researchers found that the most common emotion was acceptance, while denial was not experienced by everyone or to the same extent.

The second strong emotion was melancholy, and a depressed state accompanied all stages, and it was more pronounced than anger.

In addition, the emotional stages did not change each other in a clear sequence. A person in the third stage of grief could, for example, experience acceptance rather than anger.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption, A popular theory is that when we experience grief, we go through five successive stages.

After about six months, almost all study participants noted a decrease in negative emotions, but this did not mean complete recovery.

Longing for the deceased can last for years, but in the end, most people cope with grief.

For ethical reasons, the first interviews were conducted only a month after death, and therefore the researchers did not have an accurate picture of what a person feels in the first days and weeks after the loss.

Later, a study of people's reactions to violent death was conducted, but the participants were mostly students who lost more distant relatives than their spouse.

A strict sequence of stages was also not confirmed, although acute mental pain was more characteristic of the first stage, and acceptance - the last. However, unlike in the previous study, the scientists did not follow the reactions of one person over a long period of time.

Another study found that older people experience loss differently.

George Bonanno of Columbia University observed elderly couples before and after the death of one of their spouses. He found that 45% of people did not feel severe pain either immediately after the death of their other half, or later.

10% of widowers and widows even felt some relief. People showed resilience and were able to cope with grief.

Bonanno's latest study in 2012 also disproved the idea of stages of grief.

However, whatever the results of the research, the theory of five stages of grief is attractive in a certain sense, because it gives people hope for gradual relief.

Ruth David Koenigsberg, author of The Truth About Grief, notes that the five-stage theory forces certain feelings on people.

"It calms those who have similar emotions, but makes those who experience the death of loved ones differently feel guilty," writes Koenigsberg.

Image copyright, Unsplash

Image caption,Everyone experiences loss in their own way

"A person may think that something is wrong with him, that he does not feel what he should feel," the author adds.

However, research clearly shows that there is simply no "correct" way to mourn a loved one. Everyone experiences grief differently, and that's natural.

The feeling of loss remains, but the longing passes with time, at least for most people.

Some "scenario" of what you will experience next can be somewhat reassuring, but, unfortunately, real experience often differs from theory.

After all, life is much more complicated.

The purpose of the article is general information. It cannot replace the medical advice of a specialist. The BBC is not responsible for any diagnosis made by a reader based on information from the site. The BBC is not responsible for the content of any external Internet sites linked to by the authors of the article, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned by on on any site. Always consult your doctor if you have questions related to your health.