What is the term for giving something human qualities

Personification vs. Anthropomorphism | YourDictionary

I love the sound of raindrops dancing on the roof.

DESCRIPTION

raindrops on window and roofs

PERMISSION

Used under license from Getty Images

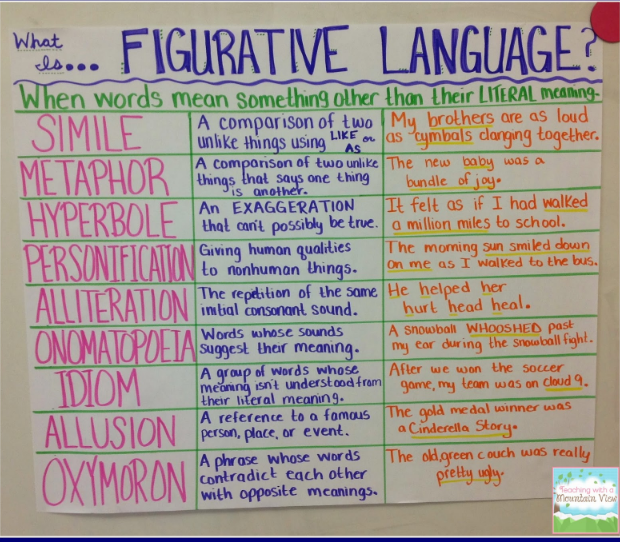

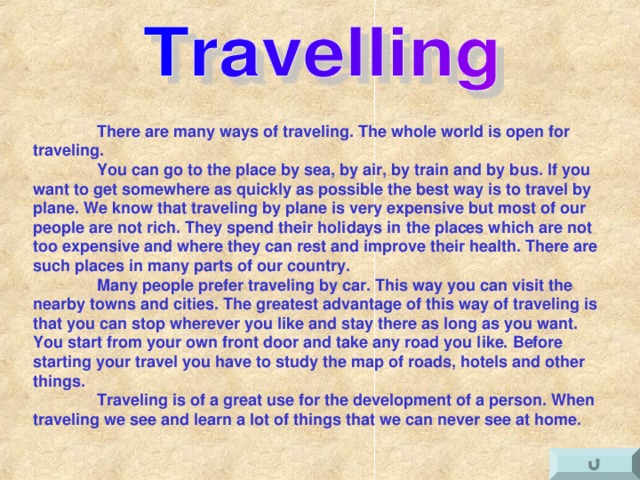

Personification and anthropomorphism are often confused because both terms have similar meanings. Anthropomorphism refers to something nonhuman behaving as human, while personification gives particular human traits to nonhuman or abstract things, or represents a quality or concept in human form. Understanding when to use personification vs. anthropomorphism will help you improve your use of figurative language.

About Personification

In classical rhetoric, personification is referred to as prosopopoeia. When a writer uses personification, he or she is applying human traits to objects. For example, people who are frustrated with technology often claim that their computer hates them, even though it's obvious a computer has no real emotions.

Personification is also sometimes used to represent an abstract concept in human form. For example, law enforcement officers and lawyers often say, "Justice is blind." Justice is a concept and obviously does not have eyes, but this phrase expresses the idea that all people are entitled to equal treatment under the law, regardless of characteristics such as skin color, gender, or financial status.

Other examples of personification you might hear in everyday language include:

- I love the sound of raindrops dancing on the roof.

- I'm on a diet, but that candy bar is calling my name.

- After a hard day at work, the couch is looking at me invitingly.

- The sun is smiling at me today.

- The angry clouds hint at the upcoming rainstorm.

- I wasn't looking for a new job, but opportunity knocked at my door.

- This novel speaks to me.

Personification is often found in popular music. Examples of personification in songs include:

Examples of personification in songs include:

Another turning point, a fork stuck in the road.

Time grabs you by the wrist, directs you where to go.

"Good Riddance," Green DayThe highway won’t hold you tonight

The highway don’t know you’re alive

The highway don’t care if you’re all alone

But I do, I do.

“Highway Don’t Care,” Tim McGraw/Taylor SwiftHere comes the sun, here comes the sun

And I say it’s all right.

"Here Comes the Sun," The Beatles,

Read our Humor Examples of Personification in Poetry to learn how this type of figurative language is used to comedic effect in verse for both children and adults.

About Anthropomorphism

When a writer uses anthropomorphism, he or she is applying human behaviors to animals, objects, or nonhuman entities. The thing is acting human rather than doing something like a human.

Anthropomorphism is often used in children's stories to teach concepts or make abstract ideas easier to understand. For example, a picture book about animals might draw an ant with visibly large muscles who is lifting weights at the gym to reinforce the idea that ants have tremendous strength relative to their body size. The characters in Thomas The Tank Engine, Clifford: The Big Red Dog, and Martha Speaks are all examples of anthropomorphism.

For example, a picture book about animals might draw an ant with visibly large muscles who is lifting weights at the gym to reinforce the idea that ants have tremendous strength relative to their body size. The characters in Thomas The Tank Engine, Clifford: The Big Red Dog, and Martha Speaks are all examples of anthropomorphism.

In literature or film, anthropomorphism can be used as a tool to explore controversial issues. For example, Animal Farm by George Orwell is a critique of the corruption of socialist ideals in the Soviet Union. Orwell was a socialist, but he believed the totalitarian regime in Stalinist Russia had betrayed the key principles of socialism. He conveyed this message through a story about farm animals rebelling against the oppression of their human caretakers.

Anthropomorphism is considered an innate tendency of human psychology. When we assign human characteristics to nonhuman entities, we are deciding what is worthy of our time and care. An example of anthropomorphism is describing pets as loving when they cuddle us after a bad day allows us to view them as members of the family. However, this tendency is not always helpful. Viewing pets as equal members of the family can be problematic if it means you fail to take precautions to protect others, such as infants or disabled adults, from an animal with the ability to cause physical harm.

An example of anthropomorphism is describing pets as loving when they cuddle us after a bad day allows us to view them as members of the family. However, this tendency is not always helpful. Viewing pets as equal members of the family can be problematic if it means you fail to take precautions to protect others, such as infants or disabled adults, from an animal with the ability to cause physical harm.

The opposite of anthropomorphism is dehumanization, which means describing human beings in non-human terms. Examples of dehumanization can be seen in Nazi propaganda. By portraying Jewish people as animals or savages, it became easier for citizens to look the other way during the horrors of the Holocaust.

What are the Key Differences?

When discussing the differences between personification and anthropomorphism, it may be helpful to remember the following:

- Personification gives a figurative meaning, while anthropomorphism gives a more literal meaning.

- Personification creates visual imagery, while anthropomorphism allows animals or objects to act like human beings.

- The most common synonym for personification is "representation," while the most common synonym for anthropomorphism is "humanization."

See our Examples of Figurative Language article for additional guidance on personification and other literary devices.

How to Use Personification vs anthropomorphism Correctly

Personification and anthropomorphism are two literary devices that are somewhat similar, but with a subtle difference. A literary device is a tool used by speakers and writers in order to produce a certain effect by manipulating words and using them in unique and unexpected ways. We will examine the definitions of the terms personification and anthropomorphism, their etymology and some examples of their use in sentences.

Personification is a literary device that ascribes human attributes to abstract ideas or inanimate objects. The attribution of human characteristics to non-human items through personification is a method of using figurative language to create imagery. Personification may attribute human traits and human qualities to an abstraction. For instance, a blindfolded woman holding balancing scales and a sword is a personification of justice. To describe a delicious dessert as “a piece of chocolate cake calling your name” is personification. The cake has no mouth or vocal chords and can not literally call someone’s name. Poets use the figurative language of personification when constructing a metaphor. “The pen danced across the page” is personification. Personification may also be used to describe something or someone who is the quintessential example of something. For instance, Audrey Hepburn is the personification of grace. Describing someone or something with personification is a method of appealing to emotions, and is not to be taken in a literal sense. The word personification is derived from the French word personnifier which means to represent. Related words are the verbs personify, personifies, personified, personifying.

Personification may attribute human traits and human qualities to an abstraction. For instance, a blindfolded woman holding balancing scales and a sword is a personification of justice. To describe a delicious dessert as “a piece of chocolate cake calling your name” is personification. The cake has no mouth or vocal chords and can not literally call someone’s name. Poets use the figurative language of personification when constructing a metaphor. “The pen danced across the page” is personification. Personification may also be used to describe something or someone who is the quintessential example of something. For instance, Audrey Hepburn is the personification of grace. Describing someone or something with personification is a method of appealing to emotions, and is not to be taken in a literal sense. The word personification is derived from the French word personnifier which means to represent. Related words are the verbs personify, personifies, personified, personifying.

Anthropomorphism is a literary device that ascribes human actions and attributes to animals or other objects. Anthropomorphism is used simply to make an animal or object behave as if it were a human being. For example, Winnie the Pooh and all of his friends are examples of anthropomorphism. All of the characters in the Disney movie Beauty and the Beast are examples of anthropomorphism. Talking animals are often depicted in a story such as a fable or a fairy tale, which is often told as an allegory. Ascribing human actions, qualities and attributes to a deity is also known as anthropomorphism. Greek and Roman philosophers in particular were known to ascribe human characteristics and traits to their non-human gods. The word anthropomorphism is derived from the Latin word anthropomorphus, which means having a human form. Related words are anthropomorphic, anthropomorphize, anthropomorphized, anthropomorphizes, anthropomorphizing, anthropomorphous.

Examples

Tracks such as “Sam,” which is about good ol’ Uncle Sam — the personification of the American tax system — showcase 2 Chainz’s economic growth. (The Daily Emerald)

The lyrics are the personification of encouragement, and Nelson delivers them gently, a reassuring presence alongside the chords of the piano. (Substream Magazine)

This kind of anthropomorphism isn’t new of course – some of the oldest known deities combine human and beast – but it has only been since Charles Darwin’s description of joy and love among animals that the debate has evolved on whether humans hold exclusivity over certain traits. (The Guardian)

Its marriage of dialogue and body language is exhilarating and its impeccably choreographed and edited action sequences are seriously thrilling with a reality that goes beyond anthropomorphism to give you a genuine sense of nature’s power. (The Sydney Morning Herald)

Use Shift+Tab to go back

what is the term for making something human

What is the term for making something human?

Personification is the use of figurative language to give inanimate objects or natural phenomena human characteristics in a metaphorical and representational manner. On the other hand, anthropomorphism includes non-human things that exhibit literal human traits and are capable of human behavior. 29September 2021

On the other hand, anthropomorphism includes non-human things that exhibit literal human traits and are capable of human behavior. 29September 2021

No mayonnaise! Salad ...

Please enable JavaScript

No mayonnaise! Chinese cabbage and corn salad

What is it called when you endow something with human qualities?

Personification is the attribution of human qualities, characteristics, or behaviors to non-human beings, be they animals, inanimate objects, or even intangible concepts.

What is similar to personification?

Synonyms of the word personification

- Abstract,

- avatar,

- incarnation,

- incarnation,

- incarnation,

- externalization,

- badge2

What is the difference between personification and anthropomorphism?

Anthropomorphism refers to something non-human behaving like a person , while personification gives certain human features to non-human or abstract things, or represents a quality or concept in human form.

When human features are given to non-human or inanimate things, what is it called?

impersonation . Giving human qualities to non-living or non-human living beings.

What does personification do?

Personification is a literary device that uses a non-literal use of language to convey concepts in a related form. Writers use the personification to give human qualities, such as emotions and behavior, to non-human things, animals, and ideas.

What is the effect of personification?

Personification links the reader to the object that personifies . Impersonation can make descriptions of non-human beings more vivid, or can help readers understand, empathize with, or respond emotionally to non-human characters.

What is it called when you give an animal quality to an object?

What Anthropomorphism ? Anthropomorphism (pronounced ann-throw-poe-MORPHism) is the giving of human features or attributes to animals, inanimate objects, or other non-human things.

What is the poetic device of anaphora?

Anaphora is a rhetorical device in which a word or expression is repeated at the beginning of a series of sentences, sentences or phrases .

What do you call that which is not human?

Words that rhyme with Inhuman

See also, how often did most eighteenth century colonists go to church?

superhuman . subhuman . inhuman . albumin .

What is the difference between personification and pathetic delusion?

A pitiful delusion is always connected with the emotions of something inhuman. Impersonation is the giving of an object some human property. .

What is the difference between an apostrophe and personification?

What is an apostrophe? Another literary device used by writers is the apostrophe. … The difference between personification and apostrophe is that personification gives a human quality to animals, objects and ideas , and in the apostrophe characters speak loudly to objects and ideas as if they were people.

A talking dog personification?

Well, you attributing human character to a dog which is a personification. … (However, if your dog starts talking to you, you may want to see a professional.)

What non-human thing is endowed with human qualities?

Personification Personification is the giving of human qualities, feelings, actions or characteristics to inanimate (non-living) objects.

What is reverse personification?

Inanimate inverse impersonation is when a person is assigned the inanimate attribute . Standing like a tree or moving like sand are examples of this. Meanwhile, living reverse personification is when a person is assigned a living attribute, such as a social butterfly.

What is synonymous with anthropomorphism?

On this page you can find 12 synonyms, antonyms, idiomatic expressions and related words for anthropomorphic, for example: humanoid , humanoid, humanoid, anthropoid, anthropomorphic, archetypal, humanoid, allegorical, mythological, cultural and idealizing.

What is the purpose of the hyperbole?

Hyperbole is effective when the audience understands that you are using hyperbole. The purpose of the hyperbole is not to deceive the reader, but to0007 emphasize the importance of something through exaggerated comparison .

What is the effect of hyperbole?

Many people use hyperbole as a figure of speech to make something seem bigger or more important than it really is. Such exaggeration or misrepresentation can help express strong emotions , emphasize a point, or even evoke humor.

What is an example of a synecdoche?

Here's a quick and easy definition: a synecdoche is a figure of speech in which, most often, a part of something is used to represent the whole. For example, " The captain commands a hundred sails. is a synecdoche in which the word "sail" is used to refer to ships - ships that are the thing of which the sail is a part.

What is the effect of alliteration?

Alliteration creates a hard and fast rhythm that moves the text forward . Alliteration can help set the pace of a work, speed it up or slow it down, depending on what sounds are used, how many words are included in the alliteration, and what other literary devices are used.

Alliteration can help set the pace of a work, speed it up or slow it down, depending on what sounds are used, how many words are included in the alliteration, and what other literary devices are used.

What does anaphora do in speech?

Anaphora is the repetition of a word or sequence of words at the beginning of successive sentences, phrases or sentences . This is one of the many rhetorical devices used by speakers and writers to emphasize their message or make their words memorable.

What is the poetic device of alliteration?

alliteration, prosody, repetition of consonants at the beginning of words or stressed syllables . Sometimes the repetition of initial vowel sounds (head rhyme) is also called alliteration. As a poetic device, it is often discussed with assonance and consonance.

Is giving an object a personification of a name?

is not a personification of or an anthropomorphism, because they give human characteristics to inanimate objects.

What does it mean if you personify inanimate objects?

When we personify, we apply human qualities to inanimate objects , to nature, to animals or to abstract concepts, sometimes supplemented by dramatic stories about their social roles, emotions and intentions.

What is anthropomorphism in psychology?

Anthropomorphism is defined as the attribution of human characteristics or behavior to any other non-human being in the environment and includes phenomena as diverse as the attribution of thoughts and emotions to both domestic and wild animals, the dressing of a Chihuahua dog as an infant, or the interpretation of deities as human beings.

See also how the houses of slaves were called.

What is Antipophora?

A hypophora, also called an antipophora or antipophora, is a figure of speech in which the speaker asks a question and then answers the question .

Which epithet is transferred?

Transferred epithet when an adjective normally used to describe one thing is transferred to another . An epithet is a word or phrase that describes the basic quality of someone or something. For example: "happy person". Epithets are usually adjectives such as "happy" that describe a noun such as "man".

An epithet is a word or phrase that describes the basic quality of someone or something. For example: "happy person". Epithets are usually adjectives such as "happy" that describe a noun such as "man".

What is an example of Epistrophe?

An epistrophe is the repetition of words at the end of a sentence or sentence. ... Brutus's speech in "Julius Caesar" includes examples of epistrophes: There are tears for his love, joy for his luck, honor for his valor and death for his ambition.

When a person behaves like an animal, his behavior is called?

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human traits, emotions, or intentions to non-human entities. … People also commonly attribute human emotions and behavioral traits to both wild and domesticated animals.

What does Gijinka mean?

Instead of referring to a simple animal with human characteristics, the gijinka is most often a fan-made redesign of an animal-like character into human or humanoid form , (for example: digimon or pokemon).

What does it mean to be an animal?

noun. preoccupation or motivation with sensual, physical or carnal appetites and not with moral, spiritual or intellectual powers.

What is the difference between anthropomorphism and pathetic delusion?

Pathetic delusion, like personification, is a type of figurative language. This attribution of emotions to non-human beings is non-literal. … Anthropomorphism, on the contrary, the literal assignment of human characteristics to animals and other non-human things .

See also what does ivpb mean

When does nature reflect the main character's mood?

Pathetic delusion is a literary device in which human emotions are attributed to aspects of nature such as the weather. For example, weather can be used to reflect a person's mood when dark clouds or rain are present in a sadness-related scene. This is a form of personification.

Is anthropomorphism a type of personification?

Personification is the use of figurative language to give human characteristics to inanimate objects or natural phenomena in a metaphorical and representational manner. On the other hand, anthropomorphism includes non-human things that display literal human traits and be capable of human behavior.

On the other hand, anthropomorphism includes non-human things that display literal human traits and be capable of human behavior.

The 10 Most Important Human Values - Fearless Soul

How to Describe Personality and Character in English (with Pronunciation)

50 Advanced Personality Adjectives | Positive and negative English vocabulary

10 immeasurable human qualities

| Types of philosophizing are characterized by three main stages in the development of philosophical thought:

The starting point in this series is the concept of classical philosophy (see Philosophy), since it is associated with ideas about the patterns of philosophizing, the corresponding names, personalities and texts, as well as about the patterns offered by philosophy to people as guidelines for their life and activity . The classical type of philosophizing presupposes the presence of a system of samples that determine the commensuration and understanding of the main aspects and spheres of being: nature, society, people's lives, their activities, knowledge, thinking. The corresponding mode of implementation of samples is also implied: their deduction, distribution, consolidation in specific forms of spiritual, theoretical, practical activity of people. So, for example, a generalized idea of a person is included in specific descriptions of human individuals, explanations of their actions, assessments of their situations. In this model, the form of description and explanation is predetermined, and when it comes into contact with "human material", it singles out certain qualities in it and measures them. Accordingly, some qualities of people and things are not taken into account by the model, remain in the "shadow" or are simply cut off by it. This aspect of the work of a generalized idea of a person as a methodological model indicates its relationship with the canons of traditional common sense. The connection of classical philosophy with science (see Science) is primarily a connection with logic (see Logic), which initially developed as part of philosophy itself, and then worked within the framework of individual sciences, mainly natural sciences and mathematics. This is the logic that provides classifications of generalization, reduction, matching and measurement procedures. As for the generalization itself, in classical philosophy very sophisticated and methodologically promising concepts of deploying general concepts into specific characteristics of being were developed. The impact of science on the philosophy of the 19th century, on its models and on the methods of their use, was explicitly or implicitly corrected by the development of the economy, industry, technology. The generalized image of a person as a measure of people's activity in the characteristics of human interactions revealed the significance of the norm. In this sense, the samples of philosophical classics fully corresponded to the canons of classical aesthetics; they were quite clear, simple, stable in relation to individual originality and dynamics of natural phenomena and social life. Their stability is akin to the colonnade of a classical temple, setting the invariable order of passage of space, turning an ordinary walk of people into a cultural event, into a ritual or its imitation; wayward and assertive time thus acquired a canonical measure. The seemingly natural stability of classical models (their totality) became one of the important prerequisites for their collapse, because it was precisely the impossibility of using the classical picture of the world in working with peculiar and dynamic systems that made people doubt its reliability, and then give it criticism and revision . However, the crisis of classical models that began in the second half of the 19th century revealed another important, previously hidden, feature: as their methodological limitations became clear, their role in the reproduction of cultural forms (see Culture), in the transmission of human experience through space and time. Non-classical philosophizing is not a direction, it is a type of thinking and action associated with a reaction to classical models, with the crisis of the classics and its overcoming. This is a reaction to the disproportion between the abstract subject of classics and concrete individuals, the abstract object - the evolution of nature, its methodology - the search for resources of intensive activity in all areas of practice. The situation, which is commonly called non-classical , is not at first revealed in philosophy or philosophy; it finds itself on the borders of philosophy and science, when classical theories of knowledge collide with objects that do not "fit" into the usual cognitive forms. The non-classical situation grew from the periphery - that is, from the boundaries outlined by the problems of science and practice - to the center, that is, to the concentration of worldview and methodological forms concentrated "around" classical philosophical samples. Tradition firmly linked the existence of patterns with their inviolability and immutability. Therefore, the threat to their stationary state was almost always perceived as a threat to their destruction. But it was precisely the regime of stationary existence of samples that came to an end. And the point is not even that they have been subjected to more and more massive criticism from different positions and points of view. The fact is that mastering a non-classical situation became possible only if the mode of their work changed. This condition, however, under the pressure of a powerful critical mass, was noticeably simplified and interpreted in terms of the rejection of samples as methodological and worldview norms. Classical models, having lost their privileged position, moved to the position of ordinary means of human activity; they came at the complete disposal of those individual subjects whose behavior they had previously regulated and directed. As the field of action of classical models was reduced, the zone of manifestation of human subjectivity became wider and wider. Subjectivity was freed from epistemological assessments that brought it closer to distorted knowledge, and revealed ontological aspects of the life and actions of human individuals. This shift in the manifestations of human subjectivity was initially recorded by psychological research. Psychology actually "rehabilitated" subjectivity and at the same time itself shifted the focus of interests from the characteristics of a person's cognitive capabilities to the interpretation of the emotional-volitional and non-rational spheres of his being. In terms of cultural and philosophical change in the status of subjectivity for a long time (until the middle of the 20th century) was assessed in accordance with classical models, that is, negatively - as the onset of subjectivism, irrationalism, nihilism. In this regard, the space of culture also seemed to be more and more fragmented , losing its stable dimensions and correspondences. From this point of view, the field of society was seen as a set of interactions of different subjects, kept from complete arbitrariness only by rigid structures of sociality. From about the second quarter of the 20th century, the question of subjectivity enters into "resonance" with the problem of finding the actual human resources for the development of society. The extensive path, in principle, turns out to be a dead end; the productivity of the economy, the prospects of technology, the renewal of science and culture turn out to be dependent on the energy and quality of the activity of individual subjects. The field of sociality appears to be divided among many subjects, and these are no longer individual subjects with their psychologized subjectivity, but "composite" - group subjects, for example, subjects realizing their images of the world, their models of activity. This production, in fact, turns out to be an ontologization of models embodied in schemes and technologies. The space of society is gradually filled with such ontologized models. From a point of view that accepts the usual logic of things, there seems to be nothing strange in this. However, the fact of the matter is that such modeling of being comes into conflict with the logic of things, since it replaces with one-sided schemes (and their ontologizations) the own being of natural objects with their inherent rhythms and laws. The theme of the interaction of different models that shape the positions and behavior of social subjects grows out of the theme of their collision. Conflict situations just reveal the fact that subjects have different images of the world and models of activity. The crisis forms of relations between people and natural systems in a certain sense speak of the same thing: the ways people act are not commensurate with the ways - which can be interpreted as a kind of "model" - of the reproduction of natural complexes. This is how a group of methodological tasks is revealed to identify models, their deontologization, limitation and processing. The solution of these problems involves the choice of a strategy aimed at removing ontologized models from the automatic mode of operation, determining their boundaries and capabilities; their adjustment or processing according to results under control for people. However, this kind of strategy is not immediately formulated, in fact, it - as a reasonable and detailed concept - does not exist until now. It "hints" at its still latent existence as a set of scientific and methodological, philosophical, ideological, socio-political movements that manifested themselves in various spheres of public life, but united by the type of tasks being solved. Moreover, in the course of the solution, the necessary means are divided and become independent goals: one group of movements insists on the dismantling of automated models up to their liquidation; the other is on the construction of new interaction models that correspond to the context of their use, the capabilities of the human individuals controlling them. In various variations, the implementation of these goals leads to the gradual formation of the principle that characterizes this type of task. It can be called the "principle of the other." “Other” turns out to be a conventional designation of that potentially multidimensional object, according to the standards of which models of interaction of people with each other and with natural systems are built. This principle points to a paradoxical task: to form interaction according to the standards of an object, the measures of which are not fixed, that is, the measures of an object do not depend on the subject, but on the way the object exists, its state, the specific nature of the interaction. In the classical situation, when the privileges of objectivity (and objectivity) were emphasized in every way, its significance, the need to reckon with it and comply with it, the measure-creating function essentially remained completely in the hands of the subject. The image of the “other” is at first anthropomorphic and personological: models of interaction with the “other” are therefore characterized in accordance with ideas about interpersonal communication between people; it is enough to recall the first attempts to substantiate the methodology of humanitarian knowledge, the "sciences of the spirit", the procedure of understanding (W. Dilthey). But the continuation of these attempts gradually leads to the conviction that in order to understand another, personal sympathy, co-understanding, co-action is not enough: this is the task, and this is its difficulty, that it is necessary to go beyond the existing personal, subjective, subjective representations and concepts, transform and reformulate them in order to determine a productive order of interaction. For philosophy (and for everyday consciousness), understanding this situation is given with great difficulty. First of all, apparently, because it is necessary to overcome not so much logical and methodological difficulties as difficulties of a moral and psychological nature: in fact, it is necessary to make the practice of going beyond the boundaries of ordinary ideas and concepts, beyond the limits of personal experience, beyond the limits of individual subjectivity. Overcoming these personal-psychological barriers, which were hidden in the philosophical and methodological work, actually means the onset of the post-classical stage and the formation of the post-classical type of philosophizing. The difficulties and complexities of this transitive situation, of course, are expressed primarily through reactions that fix the insufficiency of individual psychological forms for the work of a philosophizing subject. Therefore, the interpretation of overcoming these forms often develops into theses about the destruction or annihilation of the subject, about the disappearance of the author, about the dehumanization of philosophy, and so on. The logic of philosophy's transition to the postclassical stage and type of work is determined not only by philosophy, but by the "internal plots" of its evolution over the past century and a half. The problem of samples returns to philosophy, but it returns as a setting for changing philosophy itself, for the formation of philosophical concepts of the formation and functioning of samples , the corresponding structuring of sociality, subjects of interactions, schemes for the self-development of human individuals. The dynamics of samples and their stable functioning is, in fact, the task, on the specific solution of which other interpretations of traditional philosophical concepts and procedures depend: subject, object, measure, measurement system, generalization, concretization - all of them are rediscovered "from outside" their formation, in the aspect of interaction, in terms of self-change of social subjects. Thus, the concept of the general is less and less interpreted as the result of abstraction from individual subjects; more significant is its function of the result of the interaction of specific subjects and the scheme of their co-change. In this aspect, it indicates a form that balances the processes of being of various subjects, systems, objects, a dynamic form, becoming and changing. Such a form naturally turns out to be an element of social ties, ensures the reproducibility of social space, but obviously does not coincide with the standards of other systems of being "drawn" by a person into his activity. |

From a historical point of view, each era presents its own philosophical patterns that retain cultural significance to the present. In this sense, we should talk about the philosophical classics of Antiquity, the Middle Ages and others. In a narrower view, philosophical classics can be limited to the 17th-19th centuries and in the main space of the European region, since it was in this chronotope that the idea of classicism received a detailed justification and development. Such a narrowing of the "field" of philosophical classics makes the comparison of the classical, non-classical and post-classical more clear. Then the end of the classical stage is fixed in the middle of the 19th century, the non-classical stage - from K. Marx to E. Husserl - unfolds until the middle of the 20th century, and the postclassical stage takes shape and lasts in the second half of the 20th century with the prospect of continuing into the next century. At this stage, the “narrow” meaning of the classical is practically lost, because the inclusion of the classics in new methodological, cultural and practical contexts turns out to be significant.

From a historical point of view, each era presents its own philosophical patterns that retain cultural significance to the present. In this sense, we should talk about the philosophical classics of Antiquity, the Middle Ages and others. In a narrower view, philosophical classics can be limited to the 17th-19th centuries and in the main space of the European region, since it was in this chronotope that the idea of classicism received a detailed justification and development. Such a narrowing of the "field" of philosophical classics makes the comparison of the classical, non-classical and post-classical more clear. Then the end of the classical stage is fixed in the middle of the 19th century, the non-classical stage - from K. Marx to E. Husserl - unfolds until the middle of the 20th century, and the postclassical stage takes shape and lasts in the second half of the 20th century with the prospect of continuing into the next century. At this stage, the “narrow” meaning of the classical is practically lost, because the inclusion of the classics in new methodological, cultural and practical contexts turns out to be significant.

Like traditional ideas about human nature, it can be broadcast as an unchanging scheme of experience from generation to generation, move in social time, maintain its continuity, serve as a means of reproduction and organization of social ties. But in one essential point it differs from traditional schemes: it is not "attached" to a certain zone of social space, it is no longer associated with the peculiarities and restrictions of the estate character. Here the historical background of his logical "insight" (and seeming universality) is revealed. By the very process of history, he is cut off from concrete soil; religious, legal, economic, technological, scientific changes, it is abstracted from the ethnic, social, cultural characteristics of human communities. This feature of the classical model is reinforced by its reliance (which is often just a reference) to scientific justifications. Classical philosophy uses the authority and arguments of science to give its models a special social significance.

Like traditional ideas about human nature, it can be broadcast as an unchanging scheme of experience from generation to generation, move in social time, maintain its continuity, serve as a means of reproduction and organization of social ties. But in one essential point it differs from traditional schemes: it is not "attached" to a certain zone of social space, it is no longer associated with the peculiarities and restrictions of the estate character. Here the historical background of his logical "insight" (and seeming universality) is revealed. By the very process of history, he is cut off from concrete soil; religious, legal, economic, technological, scientific changes, it is abstracted from the ethnic, social, cultural characteristics of human communities. This feature of the classical model is reinforced by its reliance (which is often just a reference) to scientific justifications. Classical philosophy uses the authority and arguments of science to give its models a special social significance. The similarity of these samples both with traditional canons and with scientific standards indicates that they “claim” for the very role that the traditional canons of behavior and thinking played. However, the displacement of traditional schemes and the occupation of their functional "cell" by samples is carried out by philosophy based on scientific standards and by comparing philosophical samples and scientific standards as tools of human activity.

The similarity of these samples both with traditional canons and with scientific standards indicates that they “claim” for the very role that the traditional canons of behavior and thinking played. However, the displacement of traditional schemes and the occupation of their functional "cell" by samples is carried out by philosophy based on scientific standards and by comparing philosophical samples and scientific standards as tools of human activity.  It suffices to recall G. W. F. Hegel’s position on singularity as a true realization of the universal, his reasoning about individuality as the spiritual center of tribal life and its living concrete incarnation. But, firstly, Hegel himself formulated these provisions on the "margins" of his main works or in such a clearly non-methodological work as Aesthetics, and secondly, the attention of the reading public (and in this sense, society) was fixed on generalization as on the procedure of applying the pattern to different spheres of human existence, on the functioning of the pattern as a measure of various human manifestations and interactions. Eastern classics do not give examples of such a severe break of philosophy with the forms of everyday experience and, accordingly, such mutual influence of philosophy and science as European philosophy of the 19th century; the latter is especially important to understand. the soil on which 9 grows0264 postclassical philosophy.

It suffices to recall G. W. F. Hegel’s position on singularity as a true realization of the universal, his reasoning about individuality as the spiritual center of tribal life and its living concrete incarnation. But, firstly, Hegel himself formulated these provisions on the "margins" of his main works or in such a clearly non-methodological work as Aesthetics, and secondly, the attention of the reading public (and in this sense, society) was fixed on generalization as on the procedure of applying the pattern to different spheres of human existence, on the functioning of the pattern as a measure of various human manifestations and interactions. Eastern classics do not give examples of such a severe break of philosophy with the forms of everyday experience and, accordingly, such mutual influence of philosophy and science as European philosophy of the 19th century; the latter is especially important to understand. the soil on which 9 grows0264 postclassical philosophy.  A special social significance was attached to the schemes of activity and thinking that served the expanding production, mass production of things devoid of individual characteristics. The stability of these schemes was given by the corresponding image of a person, which is quite consistent with the model present in the philosophical classics. The abstractness of the model stimulated the consideration of human subjects, their qualities and relationships through the summation, subtraction, multiplication and division of their forces. Moreover, these forces essentially turned out to be abstracted from their individualized carriers. In the generalized image of a person, not only the individual characteristics of people were lost, but also their own process of being, the dynamics of their self-change, self-realization. self-development.

A special social significance was attached to the schemes of activity and thinking that served the expanding production, mass production of things devoid of individual characteristics. The stability of these schemes was given by the corresponding image of a person, which is quite consistent with the model present in the philosophical classics. The abstractness of the model stimulated the consideration of human subjects, their qualities and relationships through the summation, subtraction, multiplication and division of their forces. Moreover, these forces essentially turned out to be abstracted from their individualized carriers. In the generalized image of a person, not only the individual characteristics of people were lost, but also their own process of being, the dynamics of their self-change, self-realization. self-development.  In fact, it was in this function that he was included in the legal and moral regulators of social relations (see Society). Its abstraction from the individual characteristics and processuality of people's lives created reliable conditions for measuring the behavior of people as abstract individuals. The abstractness of the model created opportunities for its use in assessing various human situations - no matter how far people go in their actions and misdeeds, a model (set of samples) for characterizing and evaluating their actions already existed. The generalized image of a person acted in philosophy and beyond in explicit or indirect coordination with the generalized images of nature, history, culture, activity, science, law, politics, and so on. All these concepts (and instruments of action) were formed according to the same type. Therefore, they constituted a coherent classical picture of the world and implemented the methodology corresponding to it, more precisely, they were clear and rather rigid means of its implementation.

In fact, it was in this function that he was included in the legal and moral regulators of social relations (see Society). Its abstraction from the individual characteristics and processuality of people's lives created reliable conditions for measuring the behavior of people as abstract individuals. The abstractness of the model created opportunities for its use in assessing various human situations - no matter how far people go in their actions and misdeeds, a model (set of samples) for characterizing and evaluating their actions already existed. The generalized image of a person acted in philosophy and beyond in explicit or indirect coordination with the generalized images of nature, history, culture, activity, science, law, politics, and so on. All these concepts (and instruments of action) were formed according to the same type. Therefore, they constituted a coherent classical picture of the world and implemented the methodology corresponding to it, more precisely, they were clear and rather rigid means of its implementation.

The collapse of exemplary classical forms was not only a crisis in the knowledge of nature and man, it threatened the existence of fundamental structures for storing and transmitting human experience. Classical models revealed their significance as forms of social reproduction and their inability to continue to live up to this purpose.

The collapse of exemplary classical forms was not only a crisis in the knowledge of nature and man, it threatened the existence of fundamental structures for storing and transmitting human experience. Classical models revealed their significance as forms of social reproduction and their inability to continue to live up to this purpose.  At the end of the 19th century, such objects are perceived as exceptions to the rules, as exotic representatives of micro- and mega-worlds, however, the number of such objects is steadily increasing, and one has to put up with the fact that quite recently "simple and clear nature" (which should be "imitated" ) surrounds a person with an intricacies of unobservable and clearly not fixed objects. Moreover, by the middle of the 20th century, it turns out that society, the system of people's life with its conditions, means, products, also belongs to the world of non-classical objects, cannot be reduced to things, to tools, mechanisms, machines that work with things. The classical attitude towards stable natural and mental patterns and the positivist orientation towards the "logic of things" that followed it in this regard turn out to be untenable.

At the end of the 19th century, such objects are perceived as exceptions to the rules, as exotic representatives of micro- and mega-worlds, however, the number of such objects is steadily increasing, and one has to put up with the fact that quite recently "simple and clear nature" (which should be "imitated" ) surrounds a person with an intricacies of unobservable and clearly not fixed objects. Moreover, by the middle of the 20th century, it turns out that society, the system of people's life with its conditions, means, products, also belongs to the world of non-classical objects, cannot be reduced to things, to tools, mechanisms, machines that work with things. The classical attitude towards stable natural and mental patterns and the positivist orientation towards the "logic of things" that followed it in this regard turn out to be untenable.  The stability of patterns seemed to be the last stronghold of culture, and therefore of science, and morality, and, in general, a normally functioning sociality.

The stability of patterns seemed to be the last stronghold of culture, and therefore of science, and morality, and, in general, a normally functioning sociality.  The generalized image of a person, previously placed above the concrete being of people, turned into one of the methodological forms for solving some particular problems of cognition and practice. Now separate subjects, independently determining behavioral guidelines, modeling various interactions, adapted classical schemes to the implementation of their individual projects.

The generalized image of a person, previously placed above the concrete being of people, turned into one of the methodological forms for solving some particular problems of cognition and practice. Now separate subjects, independently determining behavioral guidelines, modeling various interactions, adapted classical schemes to the implementation of their individual projects.

The problem of subjectivity is gradually turning into the problem of the subjectivity of individuals as a force and form of development of sociality. Individuals "enter" the consideration of this problem first as carriers of physical and nervous energy, that is, mainly as natural bodily objects equated with other resources of social reproduction. But this move does not promise qualitative changes. There is a need to include individuals in economic, technological, managerial schemes and chains in all possible fullness of their social subjectivity, that is, with all their possibilities of self-realization and productive interaction. There is a tendency to identify and combine models that individuals operate in the organization of their acts and contacts, models implemented in the means and results of activity, in other words, models, ontologized in the practice of people turning into elements of the structures of social life.

The problem of subjectivity is gradually turning into the problem of the subjectivity of individuals as a force and form of development of sociality. Individuals "enter" the consideration of this problem first as carriers of physical and nervous energy, that is, mainly as natural bodily objects equated with other resources of social reproduction. But this move does not promise qualitative changes. There is a need to include individuals in economic, technological, managerial schemes and chains in all possible fullness of their social subjectivity, that is, with all their possibilities of self-realization and productive interaction. There is a tendency to identify and combine models that individuals operate in the organization of their acts and contacts, models implemented in the means and results of activity, in other words, models, ontologized in the practice of people turning into elements of the structures of social life.  These are subjects that accumulate the energy and organization of social communities, branches of activity, cognitive disciplines, use their means and resources, affirm their subjectivity and egoism. In the limit, these are social machines that not only occupy important positions in social space, but also reproduce this space, ontologize their models and tools, form the objectivity of social life and the types of behavior of the people themselves.

These are subjects that accumulate the energy and organization of social communities, branches of activity, cognitive disciplines, use their means and resources, affirm their subjectivity and egoism. In the limit, these are social machines that not only occupy important positions in social space, but also reproduce this space, ontologize their models and tools, form the objectivity of social life and the types of behavior of the people themselves.  This essentially gives rise to, and then makes more and more threatening the environmental problem and a number of other problems of modern society associated with the huge social inertia of extensive types of activity. The problem arises not only of limiting this type of activity, but also of coordinating different models of the world, determining the mode of their interaction, the needs and conditions for their processing.

This essentially gives rise to, and then makes more and more threatening the environmental problem and a number of other problems of modern society associated with the huge social inertia of extensive types of activity. The problem arises not only of limiting this type of activity, but also of coordinating different models of the world, determining the mode of their interaction, the needs and conditions for their processing.  And above all, this is task de-automation of models that "reborn" into large-scale production, management structures, institutionalized forms of scientific activity, "capturing" huge natural and human resources into the orbit of their functioning.

And above all, this is task de-automation of models that "reborn" into large-scale production, management structures, institutionalized forms of scientific activity, "capturing" huge natural and human resources into the orbit of their functioning.  For the first - and these include supporters of methodological and ethical anarchism, extreme deconstructivism and postmodernism, as well as the most aggressive representatives of ecological and cultural-religious anti-modernism - it is important to show the repressive function of the models, the social and technological forms they masked, to make the very process of them " disassembly" means of liberation of the multidimensional existence of people, things and texts. For the second - they include supporters of the concept of "small science", phenomenological and microsociology, ethnomethodology, social history, developmental upbringing and education, unifying (ecumenical) religious trends - the fundamental question is about formation and reproduction normative and regulatory models by specific social subjects in certain spatial and temporal conditions, about the forms of fixing the socio-spatial and temporal organization in the interactions of the people themselves.

For the first - and these include supporters of methodological and ethical anarchism, extreme deconstructivism and postmodernism, as well as the most aggressive representatives of ecological and cultural-religious anti-modernism - it is important to show the repressive function of the models, the social and technological forms they masked, to make the very process of them " disassembly" means of liberation of the multidimensional existence of people, things and texts. For the second - they include supporters of the concept of "small science", phenomenological and microsociology, ethnomethodology, social history, developmental upbringing and education, unifying (ecumenical) religious trends - the fundamental question is about formation and reproduction normative and regulatory models by specific social subjects in certain spatial and temporal conditions, about the forms of fixing the socio-spatial and temporal organization in the interactions of the people themselves.

In a postclassical situation, when the image of an object seems to be completely lost, it is the way of being of the object (objects) that becomes the most important factor in determining the models that build interaction with it. Accounting for this factor turns out to be an essential moment in the reproduction of the subject itself, its preservation and construction. The subject in this situation can be neither abstract nor "monolithic": its identity is confirmed by the constantly renewed ability to develop and reproduce interaction models.

In a postclassical situation, when the image of an object seems to be completely lost, it is the way of being of the object (objects) that becomes the most important factor in determining the models that build interaction with it. Accounting for this factor turns out to be an essential moment in the reproduction of the subject itself, its preservation and construction. The subject in this situation can be neither abstract nor "monolithic": its identity is confirmed by the constantly renewed ability to develop and reproduce interaction models.

Similarly, the multidimensionality of the “other”, the “non-classical” nature of objects and the ways of fixing them give rise to the ideas of the decay of objectivity and the destruction of reality. But reactions are followed by a stage of awareness of difficulties methodological work associated with the construction of a new form of subjectivity, with the definition of the mode of functioning of interaction schemes, with the technique of reconstructing object situations and forms of their development. In philosophy, there are still many barriers to the transition to this kind of activity: one of them is the orientation of the philosophy of the 20th century to the microanalysis of interactions, in which subject-subject relations (and contacts with the “other”) are modeled in the spirit of disciplinary-psychological, microsociological, linguistic schemes .

Similarly, the multidimensionality of the “other”, the “non-classical” nature of objects and the ways of fixing them give rise to the ideas of the decay of objectivity and the destruction of reality. But reactions are followed by a stage of awareness of difficulties methodological work associated with the construction of a new form of subjectivity, with the definition of the mode of functioning of interaction schemes, with the technique of reconstructing object situations and forms of their development. In philosophy, there are still many barriers to the transition to this kind of activity: one of them is the orientation of the philosophy of the 20th century to the microanalysis of interactions, in which subject-subject relations (and contacts with the “other”) are modeled in the spirit of disciplinary-psychological, microsociological, linguistic schemes .  Important incentives are provided by the development of such scientific areas as evolutionary universalism, biology and physiology of activity, synergetics, and the world-system approach. In this sense, we can say that N. Moiseev, L. von Bertalanffy, I. Prigogine, F. Braudel, I. Wallerstein and some other researchers did no less than famous philosophers of the second half of the 20th century to form the style of postclassical philosophizing. Their efforts are associated with a number of practical environmental, political, economic, technical and scientific problems that clearly indicate the need for the formation of samples , and most importantly, the creation of modes of operation of samples that ensure the co-existence of social systems and their co-existence with natural systems.

Important incentives are provided by the development of such scientific areas as evolutionary universalism, biology and physiology of activity, synergetics, and the world-system approach. In this sense, we can say that N. Moiseev, L. von Bertalanffy, I. Prigogine, F. Braudel, I. Wallerstein and some other researchers did no less than famous philosophers of the second half of the 20th century to form the style of postclassical philosophizing. Their efforts are associated with a number of practical environmental, political, economic, technical and scientific problems that clearly indicate the need for the formation of samples , and most importantly, the creation of modes of operation of samples that ensure the co-existence of social systems and their co-existence with natural systems.  A feature of this regime is the combination of the stability of samples as norms with their functions of regulators that ensure co-change and self-change of human subjects.

A feature of this regime is the combination of the stability of samples as norms with their functions of regulators that ensure co-change and self-change of human subjects.