What is the autism test called

Screening and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Diagnosing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can be difficult because there is no medical test, like a blood test, to diagnose the disorder. Doctors look at the child’s developmental history and behavior to make a diagnosis.

ASD can sometimes be detected at 18 months of age or younger. By age 2, a diagnosis by an experienced professional can be considered reliable [1]. However, many children do not receive a final diagnosis until much older. Some people are not diagnosed until they are adolescents or adults. This delay means that people with ASD might not get the early help they need.

Diagnosing children with ASD as early as possible is important to make sure children receive the services and supports they need to reach their full potential [2]. There are several steps in this process.

Developmental Monitoring

Developmental monitoring is an active, ongoing process of watching a child grow and encouraging conversations between parents and providers about a child’s skills and abilities. Developmental monitoring involves observing how your child grows and whether your child meets the typical developmental milestones, or skills that most children reach by a certain age, in playing, learning, speaking, behaving, and moving.

Parents, grandparents, early childhood education providers, and other caregivers can participate in developmental monitoring. CDC’s Learn the Signs. Act Early. program has developed free materials, including CDC’s Milestone Tracker app, to help parents and providers work together to monitor your child’s development and know when there might be a concern and if more screening is needed. You can use a brief checklist of milestones to see how your child is developing. If you notice that your child is not meeting milestones, talk with your doctor or nurse about your concerns and ask about developmental screening. Learn more about CDC Milestone Tracker app, milestone checklists, and other parent materials.

When you take your child to a well visit, your doctor or nurse will also do developmental monitoring. The doctor or nurse might ask you questions about your child’s development or will talk and play with your child to see if they are developing and meeting milestones.

The doctor or nurse might ask you questions about your child’s development or will talk and play with your child to see if they are developing and meeting milestones.

Your doctor or nurse may also ask about your child’s family history. Be sure to let your doctor or nurse know about any conditions that your child’s family members have, including ASD, learning disorders, intellectual disability, or attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Developmental Screening

Developmental screening takes a closer look at how your child is developing.

Developmental screening is more formal than developmental monitoring. It is a regular part of some well-child visits even if there is not a known concern.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental and behavioral screening for all children during regular well-child visits at these ages:

- 9 months

- 18 months

- 30 months

In addition, AAP recommends that all children be screened specifically for ASD during regular well-child visits at these ages:

- 18 months

- 24 months

Screening questionnaires and checklists are based on research that compares your child to other children of the same age. Questions may ask about language, movement, and thinking skills, as a well as behaviors and emotions. Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse, or other professionals in healthcare, community, or school settings. Your doctor may ask you to complete a questionnaire as part of the screening process. Screening at times other than the recommended ages should be done if you or your doctor have a concern. Additional screening should also be done if a child is at high risk for ASD (for example, having a sibling or other family member with ASD) or if behaviors sometimes associated with ASD are present. If your child’s healthcare provider does not periodically check your child with a developmental screening test, you can ask that it be done.

Questions may ask about language, movement, and thinking skills, as a well as behaviors and emotions. Developmental screening can be done by a doctor or nurse, or other professionals in healthcare, community, or school settings. Your doctor may ask you to complete a questionnaire as part of the screening process. Screening at times other than the recommended ages should be done if you or your doctor have a concern. Additional screening should also be done if a child is at high risk for ASD (for example, having a sibling or other family member with ASD) or if behaviors sometimes associated with ASD are present. If your child’s healthcare provider does not periodically check your child with a developmental screening test, you can ask that it be done.

View and print a fact sheet on developmental monitoring and screening pdf icon[657 KB, 2 Pages, Print Only]

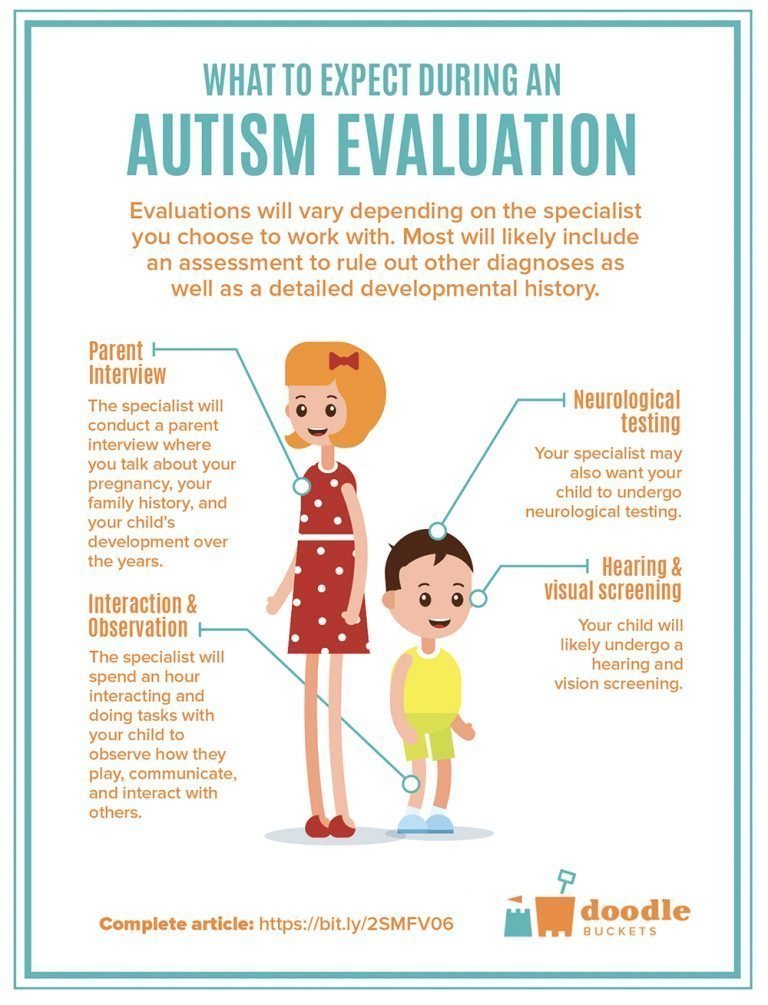

Developmental Diagnosis

A brief test using a screening tool does not provide a diagnosis, but it can indicate whether a child is on the right development track or if a specialist should take a closer look. If the screening tool identifies an area of concern, a formal developmental evaluation may be needed. This formal evaluation is a more in-depth look at a child’s development and is usually done by a trained specialist such as a developmental pediatrician, child psychologist, speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, or other specialist. The specialist may observe the child give the child a structured test, ask the parents or caregivers questions, or ask them to fill out questionnaires. The results of this formal evaluation highlight your child’s strengths and challenges and can inform whether they meet criteria for a developmental diagnosis.

If the screening tool identifies an area of concern, a formal developmental evaluation may be needed. This formal evaluation is a more in-depth look at a child’s development and is usually done by a trained specialist such as a developmental pediatrician, child psychologist, speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist, or other specialist. The specialist may observe the child give the child a structured test, ask the parents or caregivers questions, or ask them to fill out questionnaires. The results of this formal evaluation highlight your child’s strengths and challenges and can inform whether they meet criteria for a developmental diagnosis.

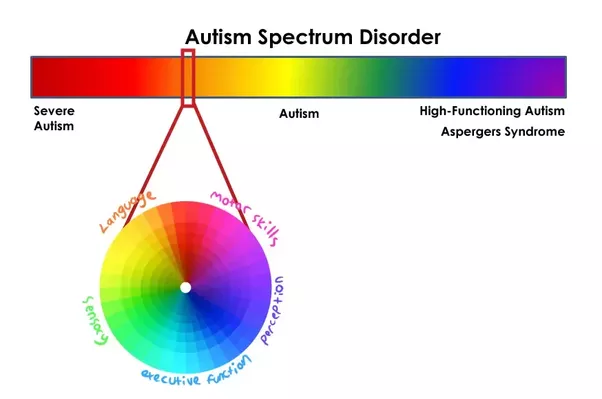

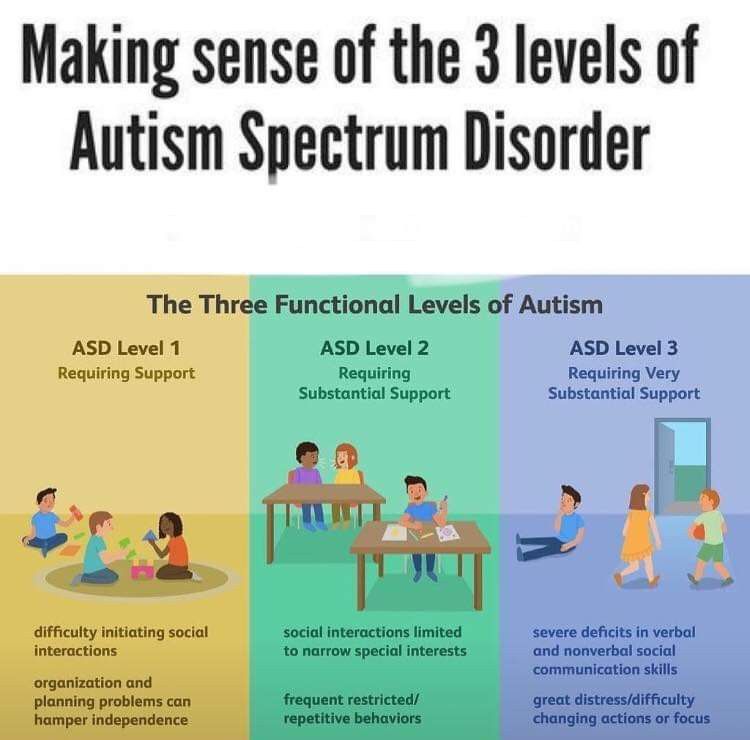

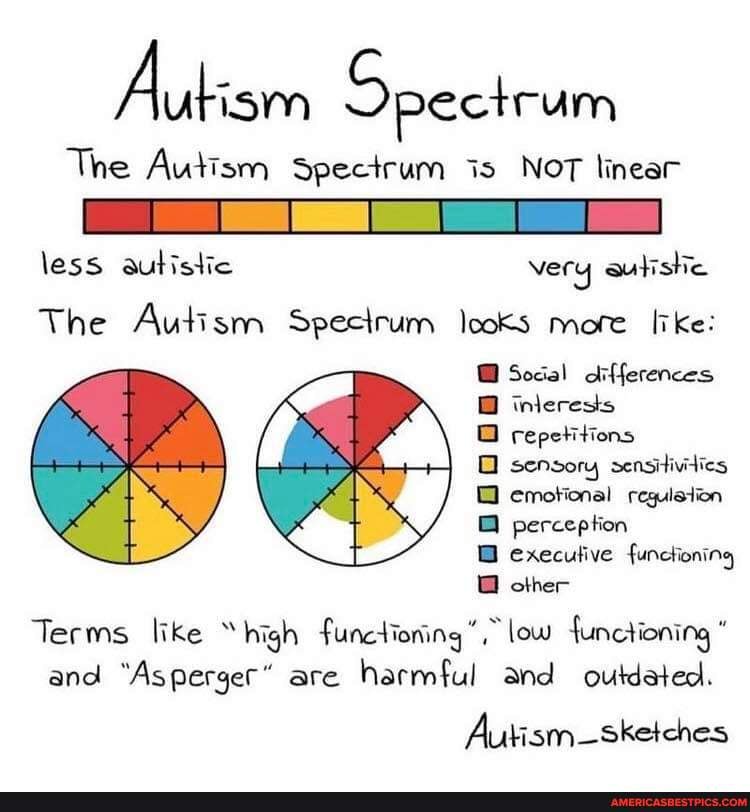

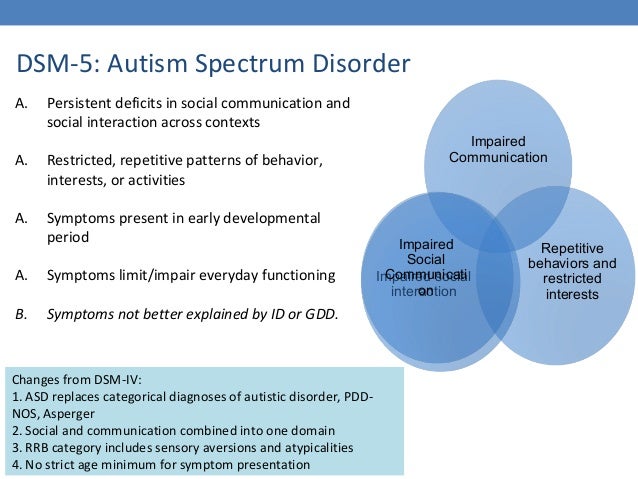

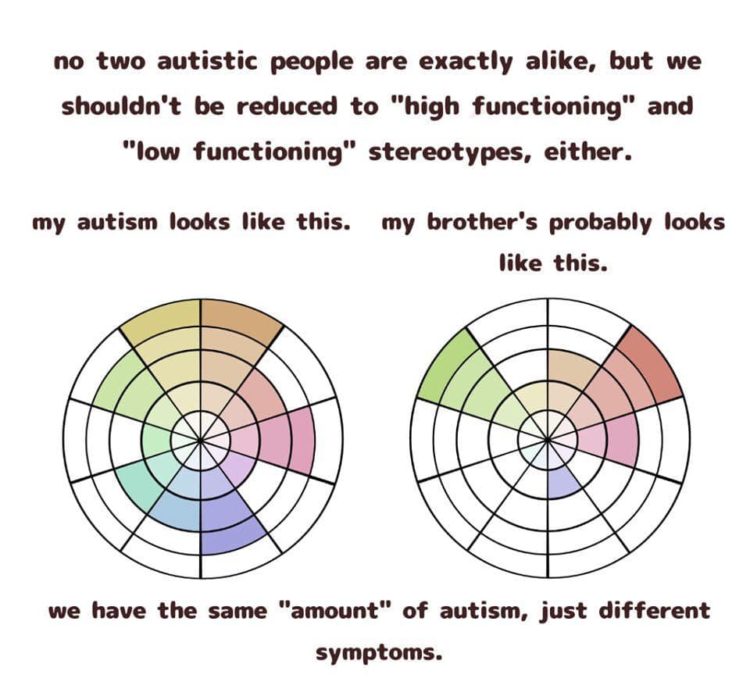

A diagnosis of ASD now includes several conditions that used to be diagnosed separately; autistic disorder, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and Asperger syndrome. Your doctor or other healthcare provider can help you understand and navigate the diagnostic process.

The results of a formal developmental evaluation can also inform whether your child needs early intervention services. In some cases, the specialist might recommend genetic counseling and testing for your child.

In some cases, the specialist might recommend genetic counseling and testing for your child.

References

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A. Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Jun;63(6):694-701.

- Hyman SL, Levey SE, Myers SM, Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Identification, Evaluation, and Management of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Pediatrics. 2020 Jan;145(1).

Screening and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder for Healthcare Providers

- Screening Recommendations

- Developmental Screening Tools

- Diagnostic Tools

- Myths About Developmental Screening

Developmental screening can be done by a number of professionals in health care, community, and school settings. However, primary health care providers are in a unique position to promote children’s developmental health.

Primary care providers have regular contact with children before they reach school age and are able to provide family-centered, comprehensive, coordinated care, including a more complete medical assessment when a screening indicates a child is at risk for a developmental problem.

Research has found that ASD can sometimes be detected at 18 months or younger. By age 2, a diagnosis by an experienced professional can be considered very reliable.[1] However, many children do not receive a final diagnosis until they are much older. This delay means that children with an ASD might not get the help they need. The earlier an ASD is diagnosed, the sooner treatment services can begin.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that all children be screened for developmental delays and disabilities during regular well-child doctor visits at:

- 9 months

- 18 months

- 30 months

Additional screening might be needed if a child is at high risk for developmental problems because of preterm birth or low birth weight.

In addition, all children should be screened specifically for ASD during regular well-child doctor visits at:

- 18 months

- 24 months

Additional screening might be needed if a child is at high risk for ASD (e. g., having a sibling with an ASD) or if symptoms are present.

g., having a sibling with an ASD) or if symptoms are present.

It is important for doctors to screen all children for developmental delays, but especially to monitor those who are at a higher risk for developmental problems due to preterm birth, low birth weight, or having a sibling or parent with an ASD.

Read more about the recommendations for screening »

In February 2016, the United States Preventive Services Task Force released a recommendation regarding universal screening for ASD among young children. This final recommendation statement applies to children ages 3 and younger who have no obvious signs or symptoms of ASD or developmental delay and whose parents, caregivers, or doctors have no concerns about the child’s development. The Task Force reviewed research studies on the potential benefits and harms of ASD screening in young children who do not have obvious signs or symptoms of ASD. They looked at whether screening all children for ASD helps with their development or quality of life. The final recommendation statement summarizes what the Task Force learned: There is not enough evidence available on the potential benefits and harms of ASD screening in all young children to recommend for or against this screening. This recommendation statement is not a recommendation against screening; it is a call for more research. For more information, please visit www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-young-children-screeningexternal icon.

The final recommendation statement summarizes what the Task Force learned: There is not enough evidence available on the potential benefits and harms of ASD screening in all young children to recommend for or against this screening. This recommendation statement is not a recommendation against screening; it is a call for more research. For more information, please visit www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/autism-spectrum-disorder-in-young-children-screeningexternal icon.

Top of Page

Developmental Screening in Pediatric and Primary Care Practice

Integrating routine developmental screening into the practice setting can seem daunting. Following are suggestions for integrating screening services into primary care efficiently and at low cost, while ensuring thorough coordination of care.

An example of how developmental screening activities might flow in your clinic:

View and Print this flowchart from a PDF pdf icon[PDF – 863K]

resize iconView Larger

D

For information on reimbursement for developmental screening:

- AAP Coding Fact Sheetsexternal icon

Involving Families in Screening

Research indicates that parents are reliable sources of information about their children’s development. Evidence-based screening tools that incorporate parent reports (e.g., Ages and Stages Questionnaire, the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status, and Child Development Inventories) can facilitate structured communication between parents and providers to discover parent concerns, increase parent and provider observations of the child’s development, and increase parent awareness. Such tools can also be time- and cost-efficient in clinical practice settings.2,3,4 A 1998 analysis found that, depending on the instrument, the time for administering a screening tool ranged from about 2 to 15 minutes, and the cost of materials and administration (using an average salary of $50/hour) ranged from $1.19 to $4.60 per visit.5

Evidence-based screening tools that incorporate parent reports (e.g., Ages and Stages Questionnaire, the Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status, and Child Development Inventories) can facilitate structured communication between parents and providers to discover parent concerns, increase parent and provider observations of the child’s development, and increase parent awareness. Such tools can also be time- and cost-efficient in clinical practice settings.2,3,4 A 1998 analysis found that, depending on the instrument, the time for administering a screening tool ranged from about 2 to 15 minutes, and the cost of materials and administration (using an average salary of $50/hour) ranged from $1.19 to $4.60 per visit.5

Screening children and providing parents with anticipatory guidance―that is, educating families about what to expect in their child’s development, how they can promote development, and the benefits of monitoring development―can also improve the relationship between the provider and parent. 6 By establishing relationship-based practices, providers promote positive parent-child relationships, while building the strongest possible relationship between the parent and provider. Such practices are fundamental to quality services.

6 By establishing relationship-based practices, providers promote positive parent-child relationships, while building the strongest possible relationship between the parent and provider. Such practices are fundamental to quality services.

Developmental Screening Tools

Screening tools are designed to help identify children who might have developmental delays. Screening tools can be specific to a disorder (for example, autism) or an area (for example, cognitive development, language, or gross motor skills), or they may be general, encompassing multiple areas of concern. Some screening tools are used primarily in pediatric practices, while others are used by school systems or in other community settings.

Screening tools do not provide conclusive evidence of developmental delays and do not result in diagnoses. A positive screening result should be followed by a thorough assessment. Screening tools do not provide in-depth information about an area of development.

Selecting a Screening Tool

When selecting a developmental screening tool, take the following into consideration:

- Domain(s) the Sreening Tool Covers

What are the questions that need to be answered?

What types of delays or conditions do you want to detect? - Psychometric Properties

These affect the overall ability of the test to do what it is meant to do.

- The sensitivity of a screening tool is the probability that it will correctly identify children who exhibit developmental delays or disorders.

- The specificity of a screening tool is the probability that it will correctly identify children who are developing normally.

- Characteristics of the Child

For example, age and presence of risk factors. - Setting in which the Screening Tool will be Administered

Will the tool be used in a physician’s office, daycare setting, or community setting? Screening can be performed by professionals, such as nurses or teachers, or by trained paraprofessionals.

Types of Screening Tools

There are many different developmental screening tools. CDC does not approve or endorse any specific tools for screening purposes. This list is not exhaustive, and other tests may be available.

Selected examples of screening tools for general development and ASD:

- Ages and Stages Questionnaires (ASQ)external icon

This is a general developmental screening tool. Parent-completed questionnaire; series of 19 age-specific questionnaires screening communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving, and personal adaptive skills; results in a pass/fail score for domains. - Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales (CSBS)pdf iconexternal icon

Standardized tool for screening of communication and symbolic abilities up to the 24-month level; the Infant Toddler Checklist is a 1-page, parent-completed screening tool. - Parents’ Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS)external icon

This is a general developmental screening tool. Parent-interview form; screens for developmental and behavioral problems needing further evaluation; single response form used for all ages; may be useful as a surveillance tool.

Parent-interview form; screens for developmental and behavioral problems needing further evaluation; single response form used for all ages; may be useful as a surveillance tool. - Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (MCHAT)external icon

Parent-completed questionnaire designed to identify children at risk for autism in the general population. - Screening Tool for Autism in Toddlers and Young Children (STAT)external icon

This is an interactive screening tool designed for children when developmental concerns are suspected. It consists of 12 activities assessing play, communication, and imitation skills and takes 20 minutes to administer.

A more comprehensive list of developmental screening toolspdf iconexternal icon is available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), including descriptions of the tools, sensitivity and specificity. The list includes general screening tools, as well as those for ASD.

Diagnostic Tools

There are many tools to assess ASD in young children, but no single tool should be used as the basis for diagnosis. Diagnostic tools usually rely on two main sources of information—parents’ or caregivers’ descriptions of their child’s development and a professional’s observation of the child’s behavior.

Diagnostic tools usually rely on two main sources of information—parents’ or caregivers’ descriptions of their child’s development and a professional’s observation of the child’s behavior.

In some cases, the primary care provider might choose to refer the child and family to a specialist for further assessment and diagnosis. Such specialists include neurodevelopmental pediatricians, developmental-behavioral pediatricians, child neurologists, geneticists, and early intervention programs that provide assessment services.

Selected examples of diagnostic tools:

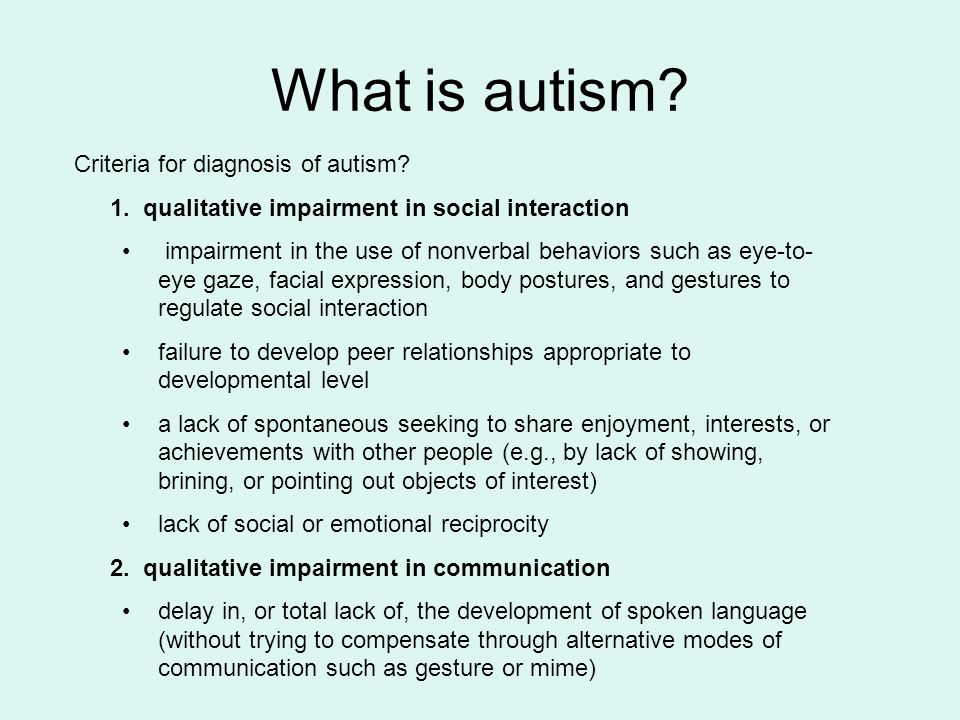

- Autism Diagnosis Interview – Revised (ADI-R)external icon[7]

A clinical diagnostic instrument for assessing autism in children and adults. The instrument focuses on behavior in three main areas: reciprocal social interaction; communication and language; and restricted and repetitive, stereotyped interests and behaviors. The ADI-R is appropriate for children and adults with mental ages about 18 months and above.

- Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule – Genericexternal icon (ADOS-G)[8]

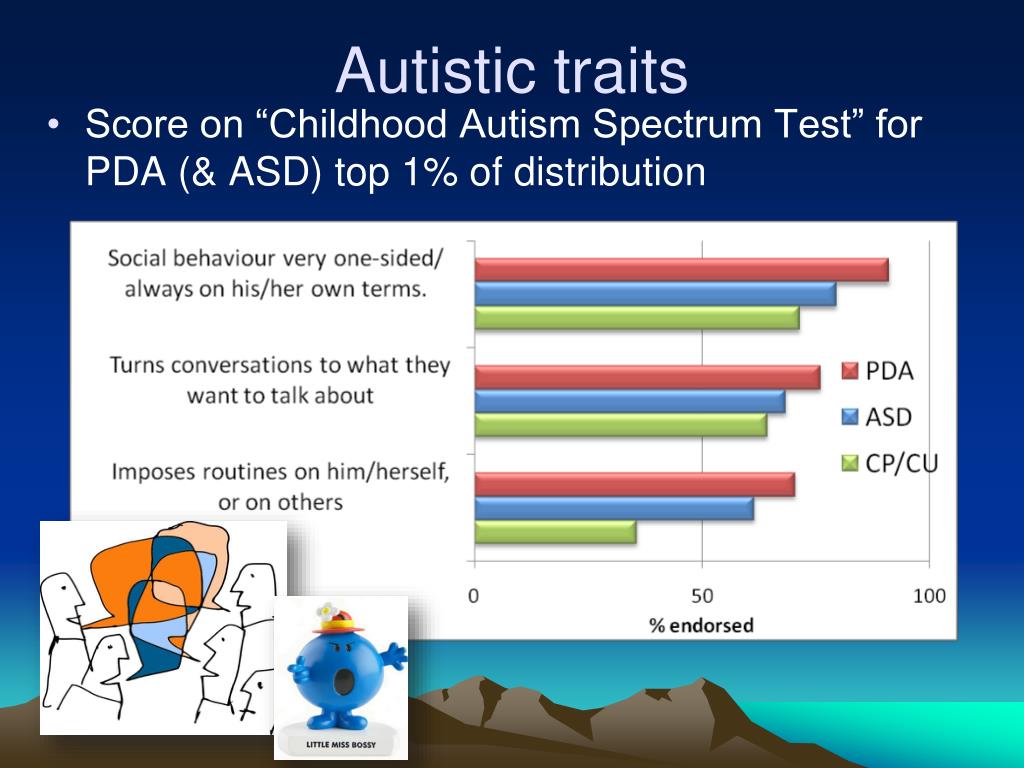

A semi-structured, standardized assessment of social interaction, communication, play, and imaginative use of materials for individuals suspected of having ASD. The observational schedule consists of four 30-minute modules, each designed to be administered to different individuals according to their level of expressive language. - Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS)[9]

Brief assessment suitable for use with any child over 2 years of age. CARS includes items drawn from five prominent systems for diagnosing autism; each item covers a particular characteristic, ability, or behavior. - Gilliam Autism Rating Scale – Second Edition (GARS-2)external icon[10]

Assists teachers, parents, and clinicians in identifying and diagnosing autism in individuals ages 3 through 22. It also helps estimate the severity of the child’s disorder.

In addition to the tools above, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) provides standardized criteria to help diagnose ASD.

See DSM-5 diagnostic criteria » Top of Page

Myths About Developmental Screening

| Myth #1 | There are no adequate screening tools for preschoolers. |

| Fact | Although this may have been true decades ago, today sound screening measures exist. Many screening measures have sensitivities and specificities greater than 70%. [5], [11] |

| Myth #2 | A great deal of training is needed to administer screening correctly. |

| Fact | Training requirements are not extensive for most screening tools. Many can be administered by paraprofessionals. |

| Myth #3 | Screening takes a lot of time. |

| Fact | Many screening instruments take less than 15 minutes to administer, and some require only about 2 minutes of professional time. [5], [12] [5], [12] |

| Myth #4 | Tools that incorporate information from the parents are not valid. |

| Fact | Parents’ concerns are generally valid and are predictive of developmental delays. Research has shown that parental concerns detect 70% to 80% of children with disabilities.[13],[14] |

References

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, Pickles A.external icon Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry 2006;63(6):694-701.

- Regalado M, Halfon N. Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2001;155:1311-1322.

- Skellern C, Rogers Y, O’Calaghan M. A parent-completed developmental questionnaire: follow up of ex-premature infants. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2001;37(2):125-129.

- Glascoe FP. Parents’ evaluation of developmental status: how well do parents’ concerns identify children with behavioral and emotional problems? Clinical Pediatrics 2003;42(2):133-138.

- Glascoe FP. Collaborating with Parents. Nashville, TN: Ellsworth & Vandermeer Press, Ltd.; 1998.

- Nelson CS, Wissow LS, Cheng TL. Effectiveness of anticipatory guidance: recent developments. Current Opinions in Pediatrics 2003;15:630-635.

- Tadevosyan-Leyfer O, Dowd M, Mankoski R, Winklosky B, Putnam S, McGrath L, et al. A principal components analysis of the Autism Diagnostic Interview–Revised. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2003;42(7):864-872.

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, DiLavore PC, et al. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2000;30(3):205-230.

- Van Bourgondien ME, Marcus LM, Schopler E. Comparison of DSM-III-R and Childhood Autism Rating Scale diagnoses of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 1992;22(4):493-506.

- Gilliam JE. Gilliam Autism Rating Scale – Second Edition (GARS-2). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 1995.

- Committee on Children and Disabilities, American Academy of Pediatrics. Developmental surveillance and screening for infants and young children. Pediatrics 2001;108(1):192-195.

- Dobrez D, Sasso A, Holl J, Shalowitz M, Leon S, Budetti P. Estimating the cost of developmental and behavioral screening of preschool children in general pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2001;108:913-922.

- Glascoe FP. Evidence-based approach to developmental and behavioral surveillance using parents’ concerns. Child: Care, Health, and Development 2000;26:137-149.

- Squires J, Nickel RE, Eisert D. Early detection of developmental problems: strategies for monitoring young children in the practice setting. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 1996;17:420-427.

- Child Development

- Developmental Disabilities

- “Learn the Signs.

Act Early.” Campaign

Act Early.” Campaign - CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities

A diagnostic test that allows you to independently track the dynamics of a child's development - NGO of assistance to children with ASD "Contact"

ATEC Autism Test to assess progress and identify problems

TheAutism Test, ATEK, is used to assess progress in children with autism. Scoring is automatic.

I. Speech/Language/Communication Skills

| 1. Knows own name: YesSometimesNo | 2. Responds to 'no' or 'stop': YesSometimesNo |

| 3. Can execute some commands: YesSometimesNo | 4. Can say one word: YesSometimesNo |

| 5. Can say 2 words in a row: YesSometimesNo | 6. Can say 3 words in a row: YesSometimesNo |

| 7. Knows 10 or more words: YesSometimesNo | 8. Uses sentences of 4 or more words in speech: YesSometimesNo Uses sentences of 4 or more words in speech: YesSometimesNo |

| 9. Explains what he/she wants: YesSometimesNo | 10. Asks meaningful questions: YesSometimesNo |

| 11. Speech is most often meaningful/logical: YesSometimesNo | 12. Often uses sentences arranged in a logical sequence: YesSometimesNo |

| 13. Maintains a conversation: YesSometimesNo | 14. Has normal communication skills for her age: YesSometimesNo |

II. Socialization

| 1. Seems to be in a shell - you can't reach him/her: YesSometimesNo | 2. Ignores other people: YesSometimesNo |

| 3. Doesn't pay much attention when he/she is spoken to: YesSometimesNo | 4. Not willing to work together: YesSometimesNo |

| 5. No eye contact: YesSometimesNo | 6. Prefers to be alone: YesSometimesNo |

7. Shows no affection: YesSometimesNo Shows no affection: YesSometimesNo | 8. Doesn't greet parents: YesSometimesNo |

| 9. Avoids contact with others: YesSometimesNo | 10. No simulation: YesSometimesNo |

| 11. Dislikes touching/hugs: YesSometimesNo | 12. Not divided, no pointing gesture: YesSometimesNo |

| 13. Does not wave goodbye: YesSometimesNo | 14. Naughty/Naughty: YesSometimesNo |

| 15. Has fits of anger, irritability: YesSometimesNo | 16. Lack of friends/no company: YesSometimesNo |

| 17. Rarely smiles: YesSometimesNo | 18. Doesn't understand other people's feelings: YesSometimesNo |

| 19. Indifferent if sympathy is expressed to him: YesSometimesNo | 20. Does not respond to parental care: YesSometimesNo |

III. Sensory/Cognitive Skills

1. Responds to own name: YesSometimesNo Responds to own name: YesSometimesNo | 2. Responds to praise: YesSometimesNo |

| 3. Looks at people and animals: YesSometimesNo | 4. Looks at pictures (and TV): YesSometimesNo |

| 5. Can draw, paint, craft: YesSometimesNo | 6. Plays with toys correctly: YesSometimesNo |

| 7. Facial expression appropriate to the situation: YesSometimesNo | 8. Understands what is happening on the TV screen: YesSometimesNo |

| 9. Understands explanations: YesSometimesNo | 10. Is aware of the environment: YesSometimesNo |

| 11. Recognizes danger: YesSometimesNo | 12. Shows imagination: YesSometimesNo |

| 13. Shows initiative: YesSometimesNo | 14. Knows how to dress himself: YesSometimesNo |

| 15. Shows curiosity, interest: YesSometimesNo | 16. Courageous - explores surroundings: YesSometimesNo |

17. Adequately perceives the environment, does not withdraw into himself: YesSometimesNo Adequately perceives the environment, does not withdraw into himself: YesSometimesNo | 18. Looks where others are looking: YesSometimesNo |

IV. Health / Growth / Behavior

| 1. Bedwetting: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 2. Peeing in pants/diapers: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 3. Pooping in pants/diapers: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 4. Diarrhea: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 5. Constipation: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 6. Sleep problems: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 7. Eating too much/too little: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 8. Eats a very limited set of foods: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

9. Hyperactivity: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem Hyperactivity: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 10. Apathy: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 11. Hits or injures himself: No problem Minor problem Medium problem Serious problem | 12. Hitting or injuring others: No problem Minor problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 13. Breaks and throws everything around: No problem Minor problem Medium problem Serious problem | 14. Sound Sensitivity: No Problem Mild Problem Moderate Problem Serious Problem |

| 15. Anxiety/fear: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 16. Depression/tears: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 17. Seizures: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 18. Obsessive Speech: Not a Problem Mild Problem Medium Problem Serious Problem |

| 19. Same procedure: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 20. Screams and Shouts: No Problem Minor Problem Medium Problem Serious Problem Screams and Shouts: No Problem Minor Problem Medium Problem Serious Problem |

| 21. Need for uniformity: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 22. Persistent agitation: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 23. Insensitivity to pain: No problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem | 24. Concentration on certain subjects/topics: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

| 25. Repetitive movements: Not a problem Mild problem Medium problem Serious problem |

Outcome scale:

- 10-15 non autistic child, completely normal, well developed child

- 16-30 non-autistic child, slight developmental delay

- 31-40 mild or moderate autism

- 41-60 moderate autism

- 61 and above severe autism

The ATEC test is not a diagnostic test, but serves to evaluate progress. The test is not intended to confirm the presence of autism, for an accurate diagnosis, you must contact a specialist.

The test is not intended to confirm the presence of autism, for an accurate diagnosis, you must contact a specialist.

Autism Laboratory Diagnostics - Medical Tests and Laboratories

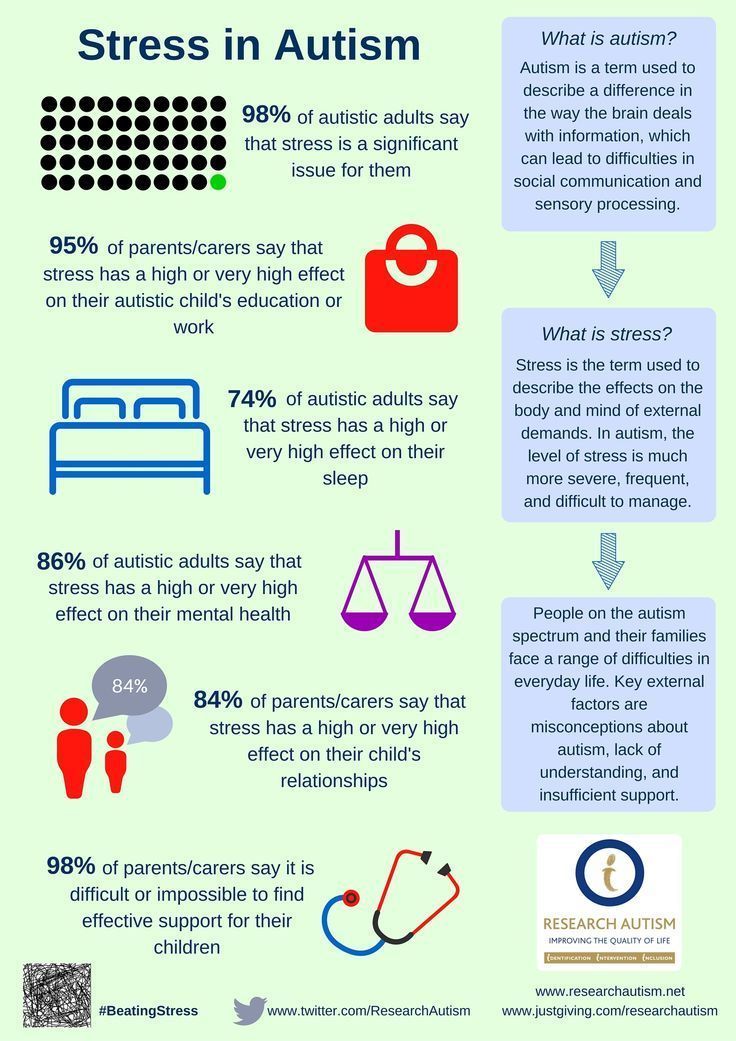

It should be noted right away that blood tests for autism (autism spectrum disorder, ASD), and any other laboratory tests are not the basis for making a diagnosis . Currently there is no such laboratory test that would unequivocally allow the diagnosis, although scientists around the world are looking for such "biomarkers", including including genetic tests, MRI, amino acid research.

Diagnosis of ASD, autism, Asperger's, etc. puts only a psychiatrist. In the diagnosis of autism and other diseases of the ASD group, in addition to clinical examination methods (somatic and neurological), an important role is played by neuroimaging (MRI), electroencephalography, video EEG, consultation of a pediatrician, neuropathologist, ophthalmologist, neuropsychologist, etc.

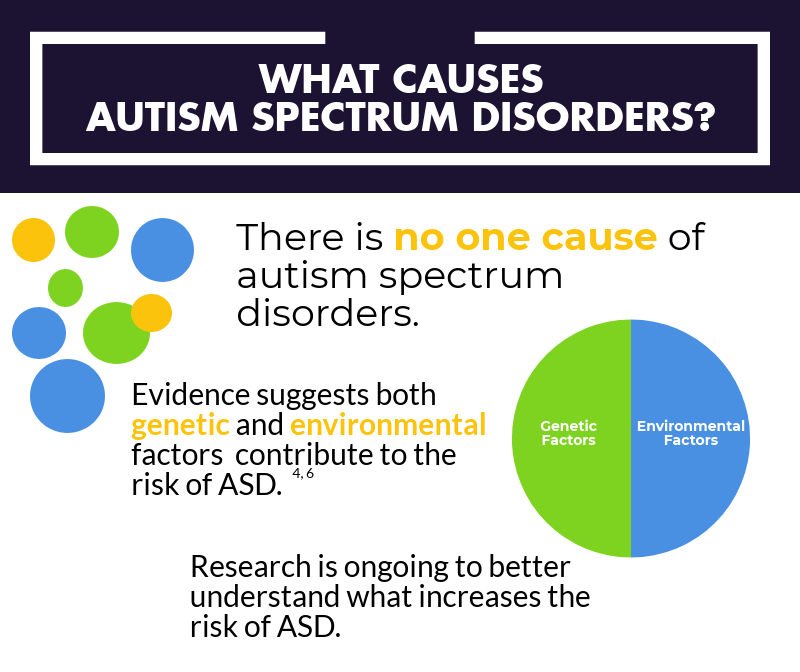

Autism is a heterogeneous disease that can have many causes, but genetic factors in combination with external influences play an important role in its development. About 30-35 percent of ASD cases are associated with genetic changes, but there is no accurate data to predict the development of autism in a child. Scientists trace the connection between autism spectrum disease and some other genetically determined diseases (such as phenylketonuria, neurofibromatosis). In recent years, several dozen candidate genes and several hundred chromosomal abnormalities have been identified in children with autism. But because of the high variability in genetic changes, it is unlikely that genetic studies will be used for routine diagnosis of autism in the coming years, as long as these studies are of more scientific interest. Doctors around the world are trying to use the latest technology - artificial intelligence - to predict autism disorders. For example, AI Predicts Autism From Infant Brain Scans (AI Predicts Autism From Infant Brain Scans)

The doctor may prescribe the following types of laboratory tests that play an auxiliary role and the purpose of which is to identify the possible cause of neuropsychiatric disorders and differential diagnosis, for example, with other genetic diseases or hereditary metabolic diseases (HMD):

- amino acid test in the blood

- test for organic acids in urine

- karyotyping - cytogenetic analysis

- DNA test

- tests for heavy metals and microelements

In addition, in order to identify concomitant pathology and prescribe symptomatic treatment, the doctor may prescribe a blood and urine biochemistry study to determine the function of the liver and kidneys, an immunogram, a hormone test, a general analysis of feces and urine. These studies will help prescribe the correct symptomatic therapy and improve the quality of life of a child with autism.

These studies will help prescribe the correct symptomatic therapy and improve the quality of life of a child with autism.

Below is a selection of links to the websites of medical laboratories that perform such rare research.

I take data for Moscow, so it is advisable to clarify in advance whether these tests are carried out in your city.

Laboratory Genomed

- Chromosomal microarray analysis is a special research method that allows to detect chromosomal anomalies, including submicroscopic ones, which are so small that they cannot be detected by standard karyotyping.

- Karyotype, expert analysis

- Panel "Mental retardation and autism spectrum disorders" - 211 genes

- Fragile X syndrome: methylation analysis (Martin-Bell syndrome)

Laboratories TsIR

- Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA)

- Determination of abnormal FMR1 gene methylation in male patients

- CGG repeat polymorphism study in the FMR1 gene (fragile X syndrome gene)

Helix Laboratory

- "Diagnosis of disorders of the metabolism of purines and pyrimidines in the blood",

- "Diagnosis of disorders of the metabolism of purines and pyrimidines in the urine"

- "Urine analysis for organic acids"

- "Toxic trace elements and heavy metals (Hg, Cd, As, Li, Pb, Al)"

- Karyotype test

- detection of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) gene mutations, ITGB3 gene

Citylab laboratory

- https://citilab.