Compulsive hoarding treatments

Hoarding disorder - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

People often don't seek treatment for hoarding disorder, but rather for other issues, such as depression, anxiety or relationship problems. To help diagnose hoarding disorder, it's best to see a mental health provider who has expertise in diagnosing and treating the condition. You'll have a mental health exam that includes questions about emotional well-being. You'll likely be asked about your beliefs and behaviors related to getting and saving items and the impact clutter may have on your quality of life.

Your mental health provider may ask your permission to talk with relatives and friends. Pictures and videos of your living spaces and storage areas affected by clutter are often helpful. You also may be asked questions to find out if you have symptoms of other mental health conditions.

Treatment

Treatment of hoarding disorder can be challenging but effective if you keep working on learning new skills. Some people don't recognize the negative impact of hoarding on their lives or don't believe they need treatment. This is especially true if the possessions or animals offer comfort. If these possessions or animals are taken away, people will often react with frustration and anger. They may quickly collect more to help satisfy emotional needs.

The main treatment for hoarding disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a skills-based approach to therapy. You learn how to better manage beliefs and behaviors that are linked to keeping the clutter. Your provider also may prescribe medicines, especially if you have anxiety or depression along with hoarding disorder.

CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the main treatment for hoarding disorder. Try to find a therapist or other mental health provider with expertise in treating hoarding disorder.

As part of CBT, you may:

- Learn to identify and challenge thoughts and beliefs related to getting and saving items.

- Learn to resist the urge to get more items.

- Learn to organize and group things to help you decide which ones to get rid of, including which items can be donated.

- Improve your decision-making and coping skills.

- Remove clutter in your home during in-home visits by a therapist or professional organizer.

- Learn to reduce isolation and increase opportunities to join in meaningful social activities and supports.

- Learn ways to increase your desire for change.

- Attend family or group therapy.

- Have occasional visits or ongoing treatment to help you keep up healthy habits.

Treatment often involves regular help from family, friends and agencies to help remove clutter. This is often the case for the elderly or those struggling with medical conditions that may make it difficult to keep up the effort and desire to make changes.

Children with hoarding disorder

For children with hoarding disorder, it's important to have the parents involved in treatment. Some parents may think that allowing their child to get and save countless items may help lower their child's anxiety and avoid family fights. This is sometimes called "family accommodation." This actually may do the opposite and strengthen the child's tendency to get and save items.

Some parents may think that allowing their child to get and save countless items may help lower their child's anxiety and avoid family fights. This is sometimes called "family accommodation." This actually may do the opposite and strengthen the child's tendency to get and save items.

In addition to therapy for their child, parents may find professional guidance helpful to learn how to respond to and help manage their child's hoarding behavior.

Medicines

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the first treatment recommended for hoarding disorder. There are currently no medicines approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat hoarding disorder. Medicines are used to treat other conditions such as anxiety and depression that often occur along with hoarding disorder. The medicines most commonly used are a type of antidepressant called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Research continues on the most effective ways to use medicines in the treatment of hoarding disorder.

More Information

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

Request an appointment

Lifestyle and home remedies

In addition to professional treatment, here are some steps you can take to help care for yourself:

- Follow your treatment plan. It's hard work, and it's common to have some setbacks over time. But treatment can help you feel better about yourself, improve your desire to change and reduce your hoarding. Have a daily schedule to work on reducing your clutter. Do this during times of the day when you have the most energy.

- Accept assistance. Local resources, professional organizers and loved ones can work with you to make decisions about how best to organize and unclutter your home and to stay safe and healthy. It may take time to get back to a safe home environment. Help is often needed to stay organized around the home.

- Reach out to others. Hoarding can lead to isolation and loneliness, which in turn can lead to more hoarding.

If you don't want visitors in your house, try to get out to visit friends and family. Joining a support group for people with hoarding disorder can let you know that you are not alone. These groups can help you learn about your behavior and available resources.

If you don't want visitors in your house, try to get out to visit friends and family. Joining a support group for people with hoarding disorder can let you know that you are not alone. These groups can help you learn about your behavior and available resources. - Try to keep yourself clean and neat. If you have possessions piled in your tub or shower, resolve to move them so that you can bathe or shower.

- Make sure you're getting proper nutrition. If you can't use your stove or reach your refrigerator, you may not be eating properly. Try to clear those areas so that you can prepare healthy meals.

- Look out for yourself. Remind yourself that you don't have to live in chaos and distress — that you deserve better. Focus on your goals and what you can gain by reducing clutter in your home.

- Take small steps. With a professional's help, you can tackle one area at a time. Small and consistent wins like this can lead to big wins.

- Do what's best for your pets. If the number of pets you have has grown beyond your ability to care for them properly, remind yourself that they deserve to live healthy and happy lives. That's not possible if you can't provide them with proper nutrition, clean living conditions and veterinary care.

Preparing for your appointment

If you or a loved one has symptoms of hoarding disorder, your health care provider may refer you to a mental health provider, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, with experience diagnosing and treating hoarding disorder.

Because some people with hoarding disorder symptoms don't recognize that their behavior is a problem, you as a friend or family member may experience more distress over the hoarding than your loved one does. If this is the case, you may want to first meet alone with a mental health provider with expertise in treating hoarding disorder. A provider can offer support and help on how to encourage your loved one to seek help.

To consider the possibility of seeking treatment, your loved one will likely need reassurance that no one is going to go into their house and start throwing things out.

Here's some information to help prepare for the first appointment and what to expect from the mental health provider.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you're experiencing, and for how long. It will help the mental health provider to know what kinds of items you feel you have to save and your personal beliefs about getting and keeping items.

- Challenges you have experienced in the past when trying to manage your clutter.

- Key personal information, including traumatic events or losses in your past, such as divorce or the death of a loved one.

- Your medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions.

- Any medicines, vitamins, herbal products or other supplements you take, and their doses.

- Questions to ask your mental health provider.

You may want to take a trusted family member or friend along, if possible. They can offer support and help remember the details discussed at the appointment. Bring pictures and videos of living spaces and storage areas affected by clutter.

Questions to ask your mental health provider include:

- Do you think my symptoms are cause for concern? Why?

- Do you think I need treatment?

- What treatments are most likely to be effective?

- How much can I expect my symptoms to improve with treatment?

- How much time will it take before my symptoms begin to improve?

- How often will I need therapy sessions, and for how long?

- Are there medicines that can help?

Feel free to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your mental health provider

To gain an understanding of how hoarding disorder is affecting your life, your provider may ask:

- What types of things do you tend to get and save?

- Do you avoid throwing things away?

- Do you avoid making decisions about your clutter?

- How often do you decide to get or keep things you don't have space or use for?

- How would it make you feel if you had to get rid of some things?

- Does the clutter in your home keep you from using rooms for their intended purpose?

- Does clutter prevent you from inviting people to visit your home?

- How many pets do you have? Are you able to provide proper care for them?

- Have you tried to reduce the clutter on your own or with the help of friends and family? How successful were those attempts?

- Have your family members expressed concern about the clutter?

- Are you currently being treated for any mental health conditions?

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Hoarding Disorder: Diagnosis and Treatment

US Pharm. 2015:40(11):60-62.

2015:40(11):60-62.

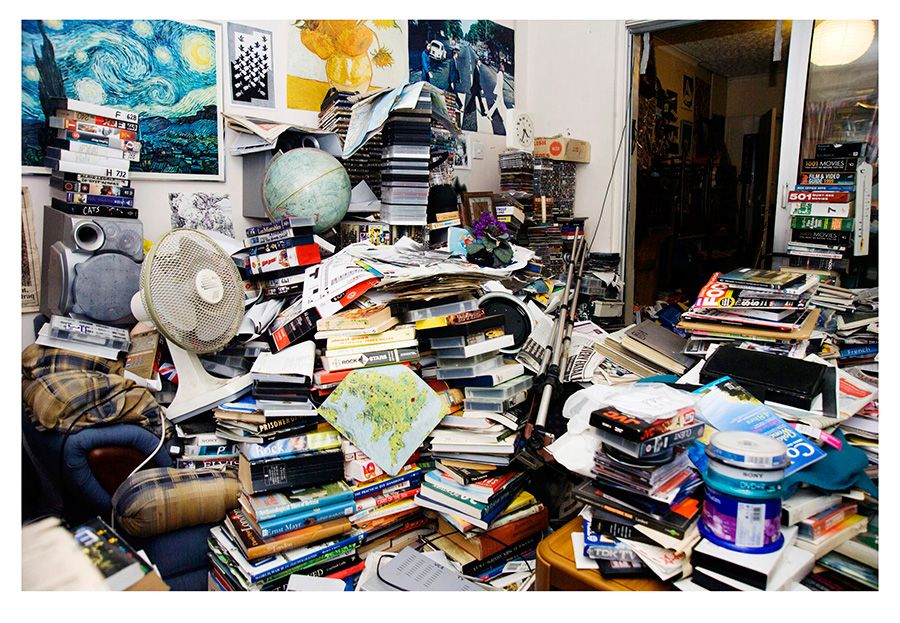

Hoarding disorder is common and potentially disabling. It is characterized by persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of the value others may attribute to these possessions. Hoarding often extends to the point that objects cover the living areas of the home and cause significant distress or impairment.1

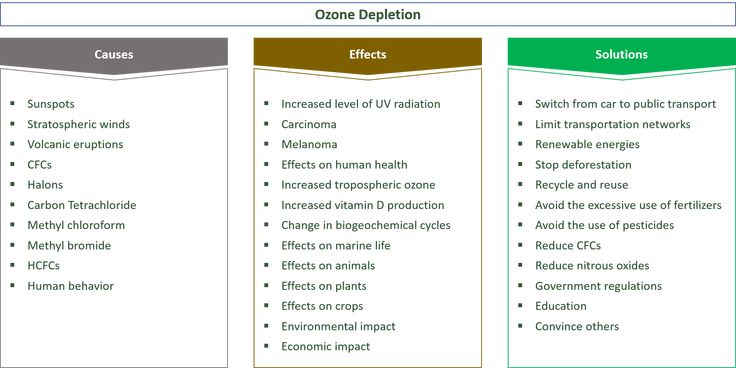

This behavior usually has harmful effects—emotional, physical, social, financial, and even legal—on the person who has the disorder and on family members. It can also potentially limit the living space and put the hoarder and others at risk for fires, falls, poor sanitation, and other health concerns. People who hoard are often conscious of their irrational behavior, but the emotional attachment to the hoarded objects far exceeds the motive to discard the items.1

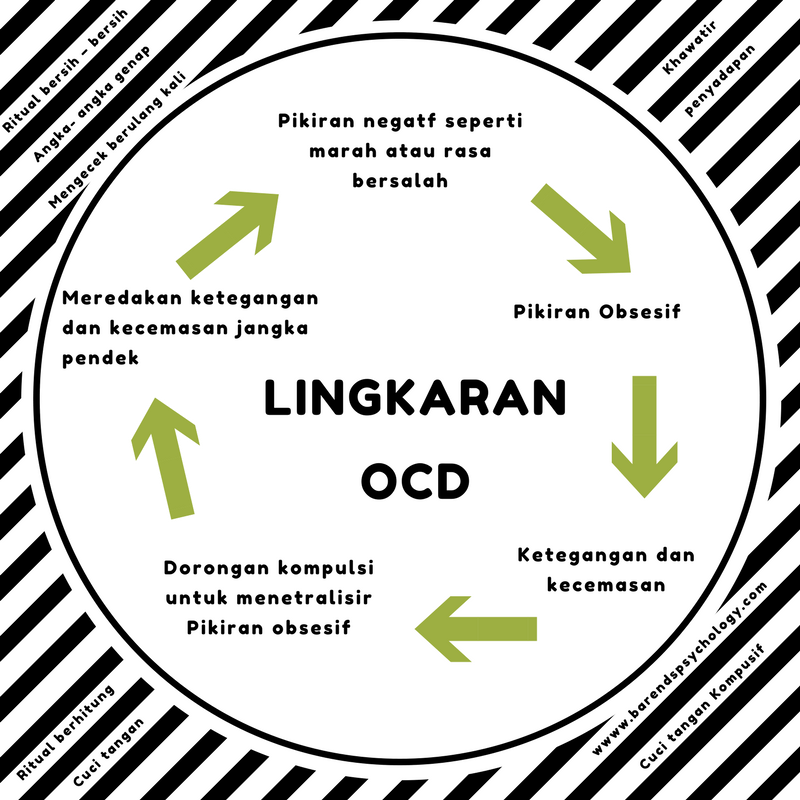

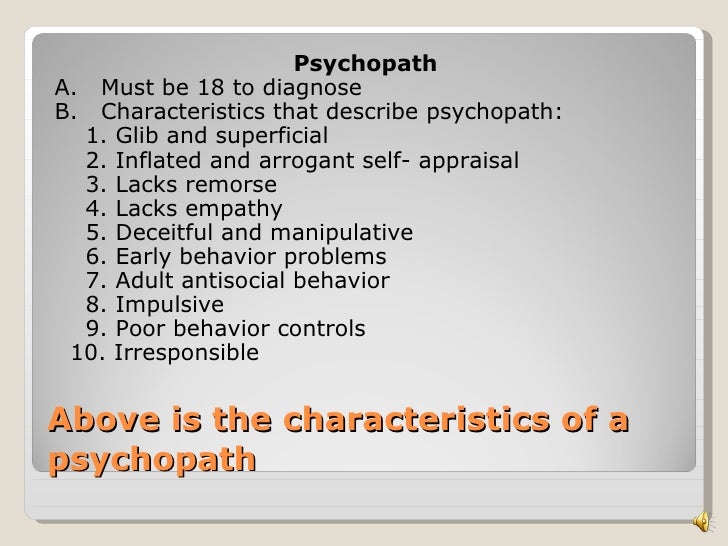

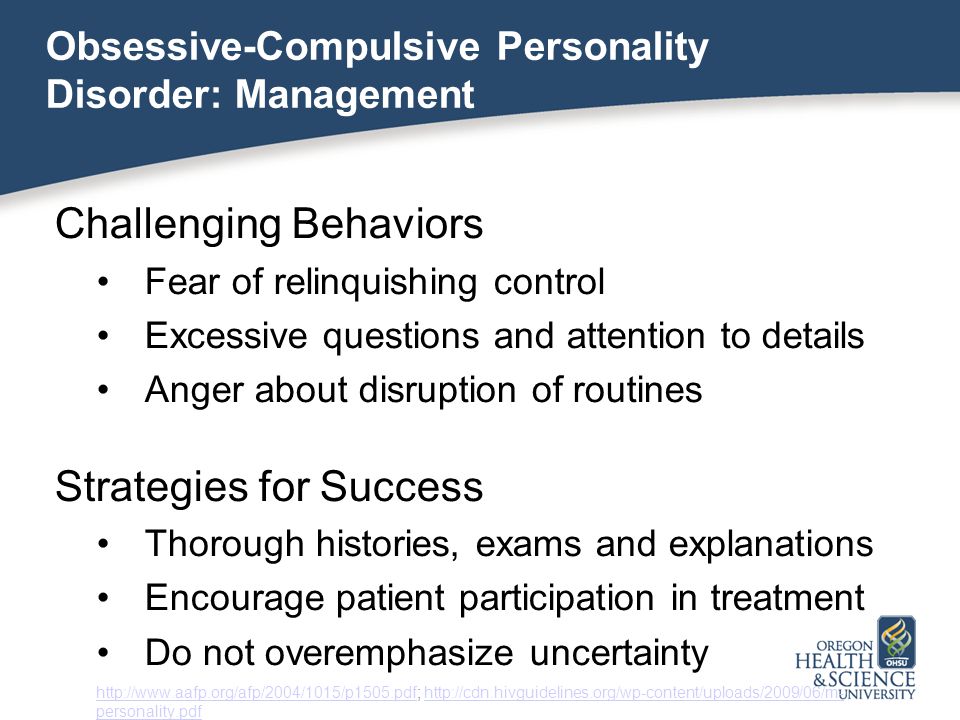

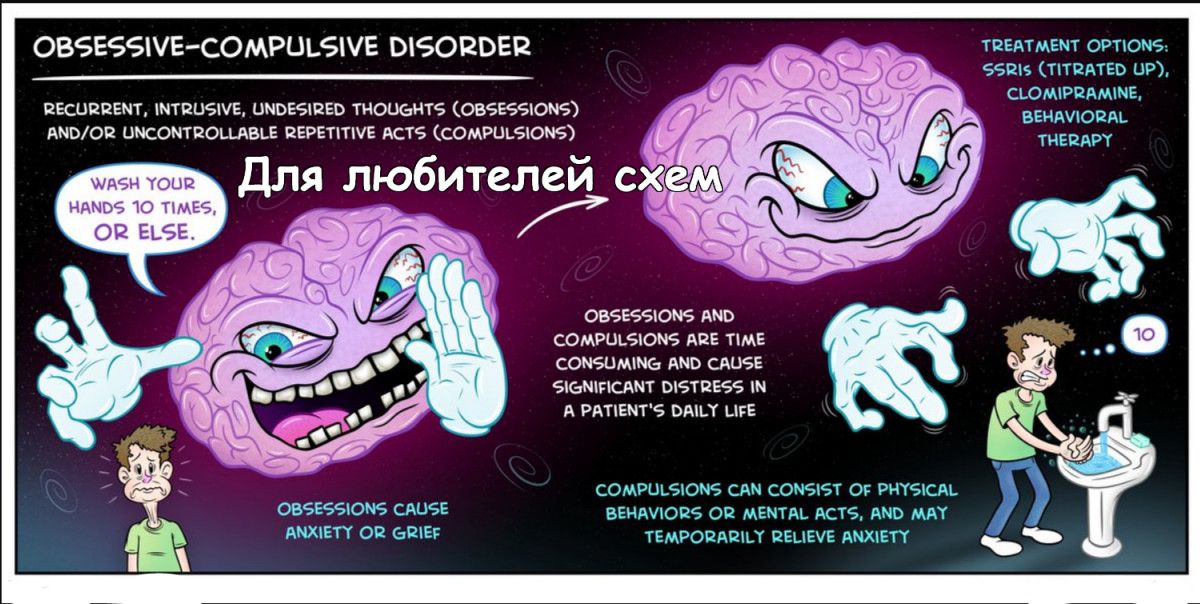

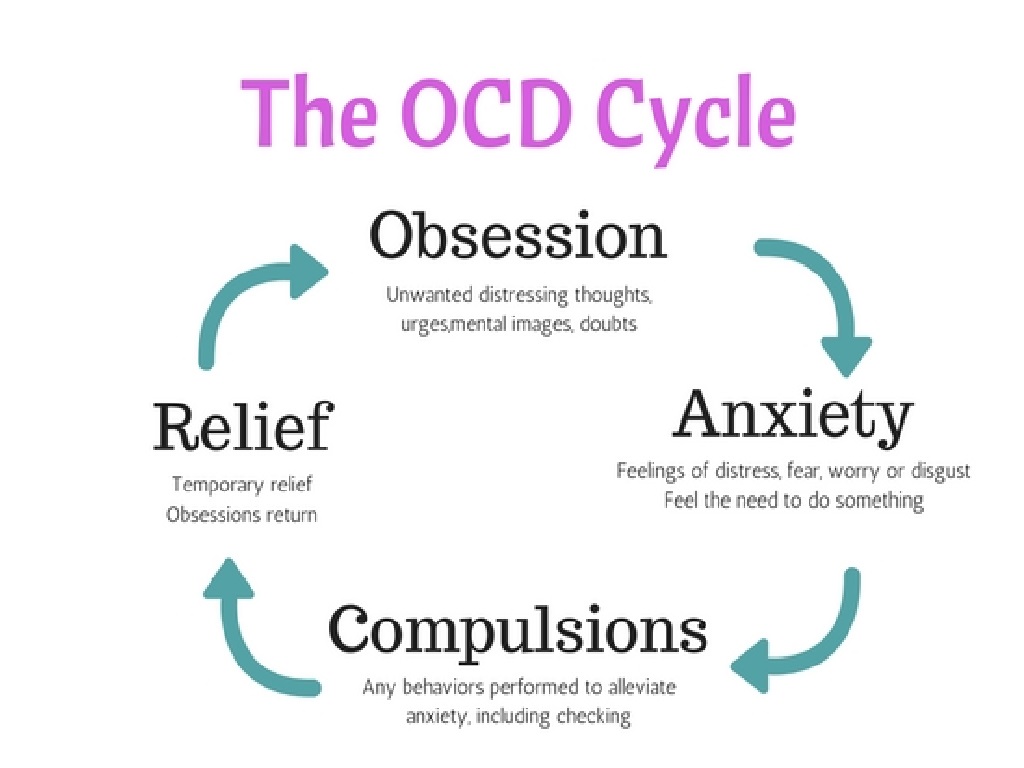

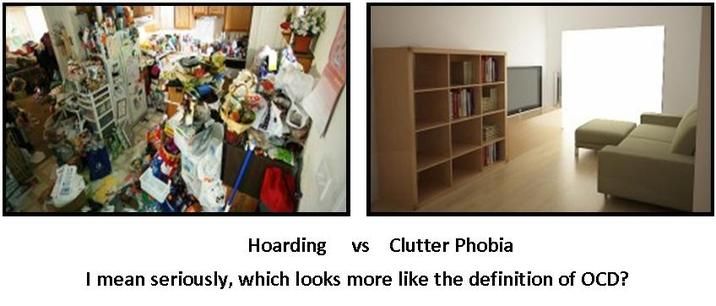

In some studies, hoarding has been listed as one of the diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD), and clinicians may consider extreme hoarding a diagnostic marker for OCPD. 2 However, regardless of the historical link between hoarding, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and OCPD, hoarding behavior frequently seems to be independent of the above neurologic and psychiatric disorders.2

2 However, regardless of the historical link between hoarding, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and OCPD, hoarding behavior frequently seems to be independent of the above neurologic and psychiatric disorders.2

Whether hoarding would continue to be described as a symptom of another disorder such as OCD or OCPD, or classified as a separate disorder in the 2013 edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) was the subject of discussion for several years. It was determined that there was sufficient evidence to recommend the creation of a new disorder called hoarding disorder. It was anticipated that the creation of this new diagnosis in the DSM-5 would, over the years, be likely to increase public awareness, improve identification of cases, and stimulate both research and the development of specific treatments for hoarding disorder.2, 3

This article takes a closer look at hoarding signs and symptoms, etiology, and possible treatments.

It has been estimated that 2% to 5% of adults exhibit hoarding behaviors. Hoarding behaviors can begin as early as the teenage years, although the average age of a person seeking treatment for hoarding is about 50 years. People who hoard often endure a lifelong struggle, and patients tend to live alone or with family members with the same problem. In certain populations, hoarding problems are present in at least 1 in 20 people.3

The inability to get rid of items is the main symptom of hoarding (Sidebar, Hoarding vs. Collecting). Other signs and symptoms include having a large amount of clutter in the office, at home, in the car, or in other spaces that makes it difficult to use furniture or appliances or move around easily; losing important items like money or bills in the clutter; feeling overwhelmed by the volume of possessions that has taken over the house or work space; being unable to stop taking free items, such as advertising flyers or sugar packets from restaurants; buying things because they are a bargain; not inviting family or friends into the home out of shame or embarrassment; and refusing to let people into the house to help or make repairs. Some hoarders keep a large number of animals, such as cats or birds, and fail to provide them with proper care.3

Some hoarders keep a large number of animals, such as cats or birds, and fail to provide them with proper care.3

Other signs and symptoms include difficulty organizing possessions, unusually strong positive feelings of delight when getting new items, strong negative feelings of fear and anger when considering getting rid of items, and strong beliefs that items are “valuable” or “useful” even when other people do not want them. Hoarders commonly deny any problems, even when clutter clearly interferes with their life.3

Hoarding appears to be more common in people with psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, alcohol dependence, and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). People who hoard often do not recognize their behavior as a problem, which makes it harder for therapists to successfully treat hoarding behavior. Study results show that hoarders are significantly less likely to see a problem in a hoarding situation than a friend or relative might. This is independent of OCD symptoms, as OCD patients are often very aware of their disorder.4

This is independent of OCD symptoms, as OCD patients are often very aware of their disorder.4

People who hoard may think that their behavior comes from having lived through a period of poverty or hardship during their lives. Research to date has not supported this idea. However, experiencing a traumatic event or serious loss, such as the death of a spouse or parent, may lead to a worsening of hoarding behavior.4

Severe clutter threatens the health and safety of those living in or near the home, causing health problems, structural damage, fire, and even death. Hoarding also causes conflicts with family members and friends who are frustrated and concerned about the state of the hoarder’s home.4

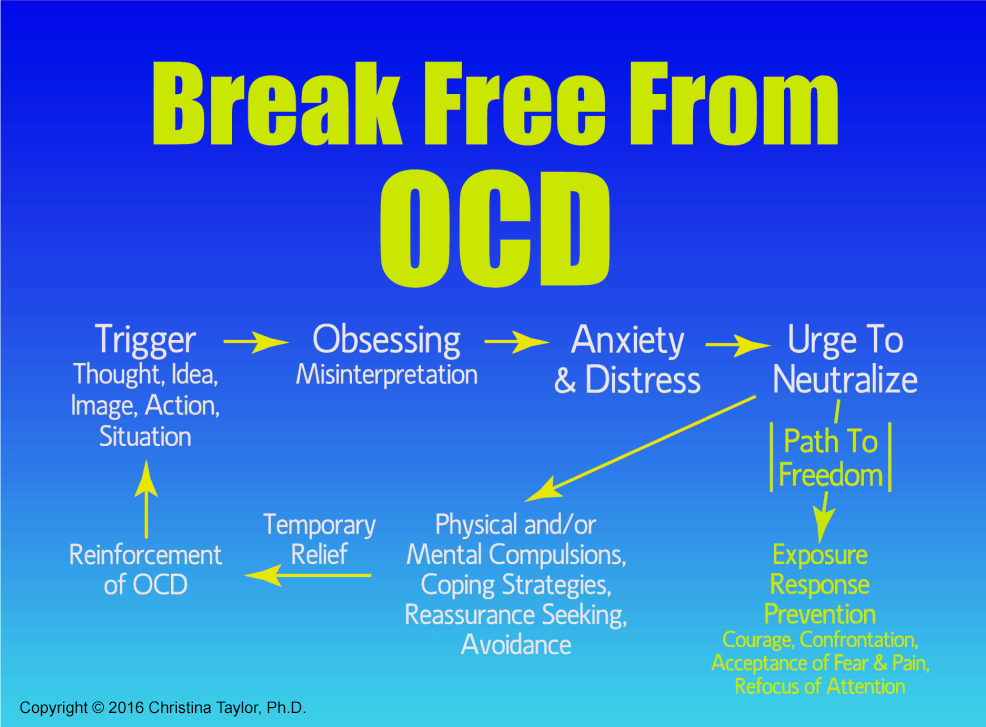

Successful hoarding treatment requires the patient to have a high degree of motivation and commitment. Attempts to clean out the homes of people who hoard without treating the underlying problem usually fail. Families and community agencies may spend many hours clearing a home only to find that the problem recurs, often within just a few months. Hoarders whose homes are cleared without their consent often experience extreme distress and may become further attached to their possessions; this may lead to the refusal of help in the future.5

Hoarders whose homes are cleared without their consent often experience extreme distress and may become further attached to their possessions; this may lead to the refusal of help in the future.5

The primary treatments for compulsive hoarding include psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and a combination of both.

Psychotherapy

Strategies to treat hoarding include challenging the hoarder’s thoughts and beliefs about the need to keep items and about collecting new things; going out without buying or picking up new items; and getting rid of and recycling clutter. The first step is to practice the removal of clutter with the help of a clinician or coach. Second, hoarders may wish to find and join a support group or team up with a coach to sort and reduce clutter. The final step is to understand that relapses can occur and develop a plan to prevent future clutter.5

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one treatment strategy for hoarding. CBT looks at four main problem areas: information-processing deficits, problems in forming emotional attachments, behavioral avoidance, and erroneous beliefs about the nature of possessions. CBT for compulsive hoarding is then directed toward decreasing clutter, improving decision-making and organizational skills, and strengthening resistance to urges to save.5

CBT for compulsive hoarding is then directed toward decreasing clutter, improving decision-making and organizational skills, and strengthening resistance to urges to save.5

Time-limited group cognitive-behavioral therapy (GCBT), which has demonstrated improvement for people with OCD, has also shown benefits for hoarders. This has become a significant psychological therapy in recent years, with research studies demonstrating the feasibility and modest success of GCBT methods in improving hoarding symptoms. Group treatment may be especially valuable because of its cost-effectiveness, greater client access to trained clinicians, and reduction in social isolation and stigma linked to this problem. Further research is needed to improve the efficacy of GCBT methods for hoarding and to examine durability of change, predictors of outcomes, and processes that influence change.6

Behavioral counselors typically use the following guidelines when a person is willing to talk about a hoarding problem: Acknowledge that people have a right to make their own decisions at their own pace; remember that everyone has some attachment to the things they own; and offer ideas to make the home safer, such as moving clutter from doorways and halls. Counselors team up with clients who hoard and refrain from arguing about whether to keep or discard an item. Instead, counselors identify what will help motivate the person to discard items and organize. Developing trust and having sympathy and respect for the person who hoards are critical.5

Counselors team up with clients who hoard and refrain from arguing about whether to keep or discard an item. Instead, counselors identify what will help motivate the person to discard items and organize. Developing trust and having sympathy and respect for the person who hoards are critical.5

Attempts by family and friends to help with decluttering may not be well received by a hoarder. It is important to know that until the person is internally motivated to change, he or she may not accept any offer for help. Motivation cannot be forced, and everyone, including people who hoard, has a right to make choices about their objects and how they live.5,6

People who hoard can be encouraged to recognize that hoarding behavior interferes with the goals or values they have. For instance, if a person who hoards desires a richer social life, decluttering the home may enable the person to host social gatherings.

The combination of cognitive rehabilitation and exposure therapy is also a promising approach in the treatment of hoarding in older adults. 6

6

Pharmacotherapy

Studies have shown that OCD patients will respond well to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications, and some of these drugs have also been found effective in patients with hoarding behavior.7

In a 2011 study by Sanjaya Saxena, MD, that included 79 OCD patients, of 32 of whom had compulsive hoarding syndrome, all participants received paroxetine 20 mg (Paxil) alone for a mean of 80 days. Both groups improved significantly with treatment of OCD symptoms, hoarding, depression, and anxiety; this result contradicts the results of previous studies that indicated compulsive hoarding does not respond well to SSRI treatment.8 The study concluded that SSRIs appear to be as effective for hoarders as for non-hoarding OCD patients.9

Venlafaxine is an SSRI as well as a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor at higher doses. Preliminary results with venlafaxine suggest a good response with hoarding behaviors in some individuals, with a trend for greater reduction in hoarding symptoms than that seen with paroxetine. 7

7

New treatment strategies might include cognitive enhancers such as donepezil or galantamine, which increase cholinergic neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex. Stimulant medications can increase the functioning of medial prefrontal cortical areas involved in attention and executive functioning.8

Symptom improvement from pharmacotherapy for compulsive hoarding appears to be at least as good as that resulting from CBT.8 It is now thought that the combination of pharmacotherapy and CBT for compulsive hoarding is likely more effective than either treatment alone.8

In addition to the above treatment strategies, research is focused on finding functional brain abnormalities and information-processing deficits that appear to underlie hoarding disorder. A new type of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which is a noninvasive magnetic field to stimulate nerve cells in certain regions of the brain to treat mood control and depression, may work for people with hoarding disorder. 9

9

Other clinicians have sought new approaches to identify cerebral metabolic patterns specifically associated with compulsive hoarding syndrome using positron emission tomography (PET). This research has compared regional cerebral glucose metabolism between OCD patients with and without compulsive hoarding, as well as normal subjects. OCD patients with compulsive hoarding had a different pattern of cerebral glucose metabolism (significantly lower glucose metabolism) than nonhoarding OCD patients (significantly higher glucose metabolism) in relation to comparison subjects. Across all OCD patients, hoarding severity was negatively correlated with glucose metabolism in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex.10

Hoarding disorder can occur in the context of several developmental, neurologic and psychiatric behaviors. Clinically significant hoarding is prevalent and can vary from mild to life-threatening. Hoarding recently met the criteria to qualify as a new disorder in DSM-5 called hoarding disorder in order to remove any ambiguities and clearly separate it from hoarding as a compulsion in OCD and or OCPD. This condition was previously classified as a symptom of OCD and patients received treatments designed for OCD.

This condition was previously classified as a symptom of OCD and patients received treatments designed for OCD.

The public and personal health consequences of hoarding are substantial, and the disorder is generally considered difficult to treat. However, hoarding disorder in highly motivated patients can be improved by pharmacologic (SSRIs) and psychological therapies or a combination of both.

REFERENCES

1. Pertusa A, Frost RO, Fullana MA, et al. Refining the boundaries of compulsive hoarding: a review. Clin Psychol Rev, 2010;30:371-386.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington,VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Mataix-Cole D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, et al. Hoarding disorder: a new diagnosis for DSM-V. Depress Anxiety, 2010;27:556-572.

4. Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ, Grados MA, et al. Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sample. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(7):836-844.

Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(7):836-844.

5. Grisham JR, Brown TA, Savage CR, et al. Neuropsychological impairment associated with compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1471-1483.

6. Muroff J, Steketee G, Rasmussen MA, et al. Group cognitive and behavioral treatment for compulsive hoarding: a preliminary trial. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:(7)634-640

7. Saxena S, Summer J. Venlafaxine extended-release treatment of hoarding disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;5:266-273.

8. Saxena S. Pharmacotherapy of compulsive hoarding. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(5):477-484.

9. Saxena S. Pharmacotherapy of compulsive hoarding. In: RO Frost, Steketee G, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Hoarding and Acquiring. New York, NY: The Oxford University Press; 2014.

10. Saxena S, Brody AL, Maidment KM, et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoarding, Am. J Psychiatry. 2004;161:(6)1038-1048.

11. Nordsletten AE, Mataix-Cols D. Hoarding versus collecting: where does pathology diverge from play? Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32-165-176.

Hoarding versus collecting: where does pathology diverge from play? Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32-165-176.

To comment on this article, contact [email protected]

Scientists told how to treat pathological hoarding

Breaking news

Applications for the Film Science!

Applications are open for the Film Science!

Plushkin's syndrome is a much more common thing than it might seem.

In a new study, Australian scientists have formulated strategies for treating pathological hoarding, which was recognized as a mental disorder in 2013.

Work published in Prescriber magazine, Science Alert talks about it briefly.

Despite the image we are accustomed to from books and films, most "hoarders" do not correspond to the dramatic stereotype of life in poverty.

Researchers report that 2-6% of people suffer from hoarding disorder. This mental disorder often manifests itself as a coping mechanism when a person struggles with other conditions, from grief and depression to recovering from traumatic brain injury. In other words, pathological hoarding is much more common than we are used to thinking and can happen to anyone.

This mental disorder often manifests itself as a coping mechanism when a person struggles with other conditions, from grief and depression to recovering from traumatic brain injury. In other words, pathological hoarding is much more common than we are used to thinking and can happen to anyone.

The patient has difficulty throwing away or parting with things, regardless of their value. In his picture of the world, there is a conscious need to save objects, and when throwing them away, a person experiences suffering.

Hoarding behavior becomes a disorder when the things a person keeps begin to interfere with his own life or the lives of others. At first, many gatherers are socially active members of society. The development of the disease leads to the accumulation of things that increasingly clutter up the house up to the complete impossibility of using this room. Some patients spend the night in the car or on the street because of the inability to enter the house filled with things.

“One of the main hallmarks of this condition is denial of care, so clinicians are in the unique position of not immediately agreeing with a patient's desire to remain untreated,” the scientists explained. “Instead, gentle, persistent attempts to help should be made, combined with emotional support, even if the person refuses to open the door.”

The researchers emphasize that once help has been accepted, physicians must first address other problems that may worsen accumulation. In more than 50% of cases, hoarding coexists with other conditions such as mental disorders (depression or alcohol abuse) or physical ailments (arthritis).

MRI scans have shown that people with storage disorders tend to have fewer neural connections in areas of the brain associated with cognitive control, but more connections in parts of the brain that focus on the inner world. This explains the inability of patients to comprehend the real value and meaning of the collected things.

Researchers recommend CBT. In some cases, drugs used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder are effective.

In some cases, drugs used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder are effective.

Scientists emphasize that a multidisciplinary approach is required in the treatment of pathological hoarding. Such patients need emotional support and a sense of security.

Photo: Shutterstock

Hallucinations in mice helped to understand the cause of psychosis

Researchers have found that money really makes people happier

Materials from Facebook and Instagram Internet resources owned by Meta Platforms Inc. banned on the territory of the Russian Federation

Tell a friend

-

Shutterstock

A new study by Russian scientists confirms the theory of where water came from on Earth

-

Science / Midjourney

What will happen if artificial intelligence becomes a rival to humans

-

Midjourney

How to use the energy of the Sun for human needs: a possible future

-

Shutterstock

The universe may be shaped like a donut, not a pancake, scientists say

-

Shutterstock

Historian: Leonardo da Vinci's mother is a slave taken from the territory of modern Russia

Do you want to be aware of the latest developments in science?

Leave your email and subscribe to our newsletter

Your e-mail

By clicking on the "Subscribe" button, you agree to the processing of personal data

Pathological accumulation.

Why is it difficult for people to part with things. Society news

Why is it difficult for people to part with things. Society news This phenomenon has many names: Plyushkin's syndrome in honor of the famous character of "Dead Souls", hoarding, syllogomania. But the essence is the same: a person accumulates a huge amount of things, keeps them at his place, littering his home.

Since January 1, 2022, the World Health Organization has included pathological hoarding in the list of mental disorders in the new classifier of diseases ICD-11. There is no golden pill for him.

They missed their grandfather

“My grandfather was a pathological hoarder,” says Alexander . - Lived in Khrushchev. He collected things from the nearest trash can that he thought would definitely come in handy: wires, screwdrivers, cans, egg containers. Neither persuasion nor intimidation helped. Fortunately, there was no stench, and neither were rats. Just in case, we threw a remedy for cockroaches every time we entered the apartment.

The neighbors didn't complain. They just thought he was a strange old man. Problems arose when the renovation began in the house. Grandfather did not let anyone into the apartment - neither workers, nor the police, not even us. He died alone, in a cluttered apartment.

Read also

Cleaning of cemeteries has started in Belgorod 05 Apr 2023 15:55

More than 200 unauthorized dumps remain uncleaned in the Belgorod region 05 Apr 2023 10:05

The old man and grief. Who helps the elderly in difficult situations

At what point we missed grandfather, I don't know. Probably, it all started after the death of his grandmother, he began to greatly value her things. Although no one was going to throw them away. Grandfather and grandmother were happy, they lived together for almost 50 years. After his death, we threw trash out of the apartment just in bags. Among the garbage, they really found a treasure - his accordion. When he was healthy, he liked to play on it. They also found a box of his working tools.

Although no one was going to throw them away. Grandfather and grandmother were happy, they lived together for almost 50 years. After his death, we threw trash out of the apartment just in bags. Among the garbage, they really found a treasure - his accordion. When he was healthy, he liked to play on it. They also found a box of his working tools.

An ancient phenomenon

Hoarding in itself is not a bad process. It’s also profitable to buy a couple of packs of pasta in reserve at a good discount. And just in case, keep several sets of socks and T-shirts in the closet.

“This behavior is typical of each of us, and probably everyone has a supply of food in the refrigerator, clothes. And that's okay. Hoarding is a very ancient phenomenon. Those of our ancestors survived who could make supplies, for example, for a period of bad weather, when it was impossible to hunt, or some unfavorable circumstances, ”explains the psychologist of the regional Center for Public Health and Medical Prevention Ruslana Todorova .

Photo: fb.ru

Apply

If usually a sick person is pitied and sympathized with, then hoarders cause irritation and even hatred.

“Sometimes, depending on the circumstances, hoarding begins to turn into a pathological form of behavior,” says Ruslana Gennadievna. - It goes beyond the norm when people collect garbage and unnecessary things in landfills, sometimes at night, bring huge packages home. They litter the dwellings and are no longer able to give what they collect the proper form or find a use for.

The fact that the bags brought into the house are full of rubbish is understandable to a healthy person. For the hoarder, all this has value.

“They fantasize that the collected things can be useful to them for a rainy day, something useful can be made from them. But in reality, a person never finds a use for them, - Todorova explains.

- This can also include the syndrome of material accumulation. We know stories about billionaires who seek to maximize their material wealth instead of rationally spending the money they earn. The meaning of their life is accumulation.

Photo: wisto.ru

In the mountains of garbage

“Plyushkin's syndrome is a manifestation of many diseases, most often obsessive-compulsive disorder,” says Ruslana Gennadievna. - Often the impetus for the disease is some kind of problem with physical or mental health. For example, a transferred infectious disease, the same coronavirus.

And here it is important to understand, the specialist believes that a lot depends on the sensitivity of a person, his nervous system. An eternal optimist may not attach much importance to some unpleasant incident, but an anxious person will withdraw into himself, and the disease will begin to develop.

« Obsessive-compulsive disorder also occurs as a result of post-traumatic stress disorder: in case of loss of loved ones, life threat, detection of a serious illness, surgical interventions. Plyushkin's syndrome can be a consequence or a form of manifestation of schizophrenia, an intellectual disorder, Ruslana Todorova explains. “A complex impact, psychotherapy, therapy is needed to control these processes.”

Photo: pixabay.com

Animal hoarding

“In the house where my parents lived, an elderly woman was collecting cats. They said that she had about a hundred of them, - says Natalya . - She did not let anyone into the apartment, but from the street it was clear that the cats were lying in piles on the windows. You can imagine what a stench was on the landing. The neighbors were indignant, tried to take action, but, as far as I know, the battle with the animal lover was lost.

”

Indeed, in stories with hoarding of cats and dogs, neighbors rarely manage to solve the problem peacefully. And even with the involvement of the police, firefighters, administration. Meanwhile, very real threats come from bad apartments - an unpleasant smell, fleas, skin and respiratory diseases.

“Man is a social being, he needs to take care of someone and feel love and gratitude in return,” says Ruslana Gennadievna. - People who have not received a response from loved ones, single residents can transfer this form of affection to animals that are easier to control than, for example, grown children. It seems to the patient that cats and dogs are in dire need of him and will be grateful for their care all their lives. Man is not aware of what often makes animals sick and unhappy."

Photo: from the editorial archive

Difficult question

Article 91 of the Housing Code of the Russian Federation regulates the process of evicting a tenant from a dwelling.