What causes a laugh

What's So Funny? The Science of Why We Laugh

“How Many Psychologists Does It Take ... to Explain a Joke?”

Many, it turns out. As psychologist Christian Jarrett noted in a 2013 article featuring that riddle as its title, scientists still struggle to explain exactly what makes people laugh. Indeed, the concept of humor is itself elusive. Although everyone understands intuitively what humor is, and dictionaries may define it simply as “the quality of being amusing,” it is difficult to define in a way that encompasses all its aspects. It may evoke the merest smile or explosive laughter; it can be conveyed by words, images or actions and through photos, films, skits or plays; and it can take a wide range of forms, from innocent jokes to biting sarcasm and from physical gags and slapstick to a cerebral double entendre.

Even so, progress has been made. And some of the research has come out of the lab to investigate humor in its natural habitat: everyday life.

The greatest of them all: Charlie Chaplin was among the fathers of slapstick comedy, which relies on physical gags.Superiority and Relief

For more than 2,000 years pundits have assumed that all forms of humor share a common ingredient. The search for this essence occupied first philosophers and then psychologists, who formalized the philosophical ideas and translated them into concepts that could be tested.

Perhaps the oldest theory of humor, which dates back to Plato and other ancient Greek philosophers, posits that people find humor in, and laugh at, earlier versions of themselves and the misfortunes of others because of feeling superior.

The 18th century gave rise to the theory of release. The best-known version, formulated later by Sigmund Freud, held that laughter allows people to let off steam or release pent-up “nervous energy.” According to Freud, this process explains why tabooed scatological and sexual themes and jokes that broach thorny social and ethnic topics can amuse us. When the punch line comes, the energy being expended to suppress inappropriate emotions, such as desire or hostility, is no longer needed and is released as laughter.

When the punch line comes, the energy being expended to suppress inappropriate emotions, such as desire or hostility, is no longer needed and is released as laughter.

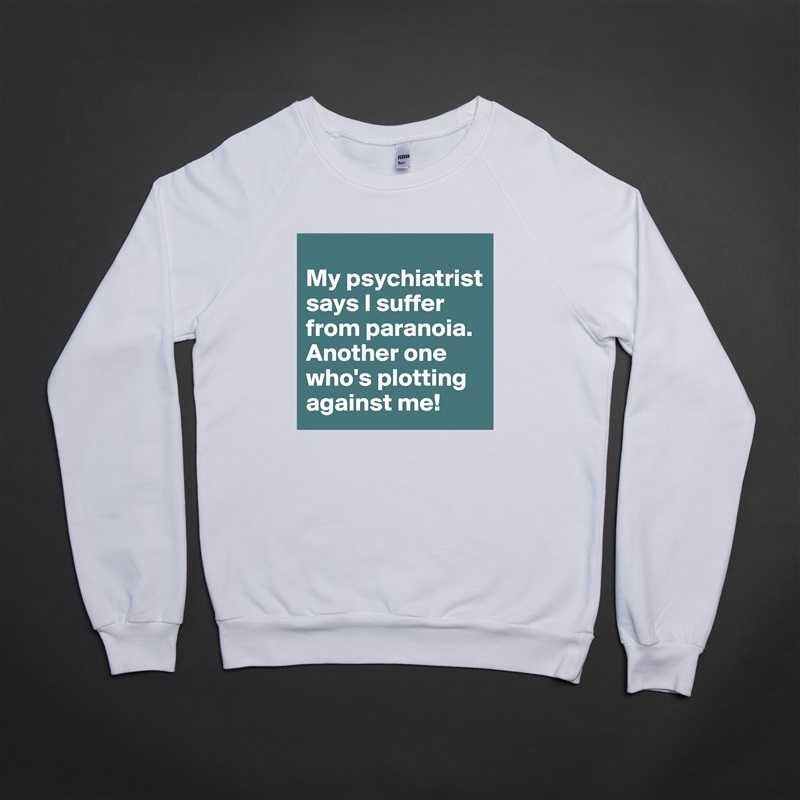

A third long-standing explanation of humor is the theory of incongruity. People laugh at the juxtaposition of incompatible concepts and at defiance of their expectations—that is, at the incongruity between expectations and reality. According to a variant of the theory known as resolution of incongruity, laughter results when a person discovers an unexpected solution to an apparent incongruity, such as when an individual grasps a double meaning in a statement and thus sees the statement in a completely new light.

Benign Violation

These and other explanations all capture something, and yet they are insufficient. They do not provide a complete theoretical framework with a hypothesis that can be measured using well-defined parameters. They also do not explain all types of humor. None, for example, seems to fully clarify the appeal of slapstick. In 2010 in the journal Psychological Science, A. Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren, both then at the University of Colorado Boulder, proposed a theory they call “benign violation” to unify the previous theories and to address their limits. “It’s a very interesting idea,” says Delia Chiaro, a linguist at the University of Bologna in Italy.

In 2010 in the journal Psychological Science, A. Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren, both then at the University of Colorado Boulder, proposed a theory they call “benign violation” to unify the previous theories and to address their limits. “It’s a very interesting idea,” says Delia Chiaro, a linguist at the University of Bologna in Italy.

McGraw and Warren’s hypothesis derives from the theory of incongruity, but it goes deeper. Humor results, they propose, when a person simultaneously recognizes both that an ethical, social or physical norm has been violated and that this violation is not very offensive, reprehensible or upsetting. Hence, someone who judges a violation as no big deal will be amused, whereas someone who finds it scandalous, disgusting or simply uninteresting will not.

Experimental findings from studies conducted by McGraw and Warren corroborate the hypothesis. Consider, for example, the story of a church that recruits the faithful by entering into a raffle for an SUV anyone who joins in the next six months. Study participants all judged the situation to be incongruous, but only nonbelievers readily laughed at it.

Study participants all judged the situation to be incongruous, but only nonbelievers readily laughed at it.

Levity can also partly be a product of distance from a situation—for example, in time. It has been said that humor is tragedy plus time, and McGraw, Warren and their colleagues lent support to that notion in 2012, once again in Psychological Science. The recollection of serious misfortunes (a car accident, for example, that had no lasting effects to keep its memory fresh) can seem more amusing the more time passes.

Geographical or emotional remoteness lends a bit of distance as well, as does viewing a situation as imaginary. In another test, volunteers were amused by macabre photos (such as a man with a finger stuck up his nose and out his eye) if the images were presented as effects created with Photoshop, but participants were less amused if told the images were authentic. Conversely, people laughed more at banal anomalies (a man with a frozen beard) if they believed them to be true. McGraw argues that there seems to be an optimal comic point where the balance is just right between how bad a thing is and how distant it is.

McGraw argues that there seems to be an optimal comic point where the balance is just right between how bad a thing is and how distant it is.

Evolutionary Theory

The idea of benign violation has limitations, however: it describes triggers of laughter but does not explain, for instance, the role humor has played in humanity’s evolutionary success. Several other theories, all of which contain elements of older concepts, try to explain humor from an evolutionary vantage. Gil Greengross, an anthropologist then at the University of New Mexico, noted that humor and laughter occur in every society, as well as in apes and even rats. This universality suggests an evolutionary role, although humor and laughter could conceivably be a byproduct of some other process important to survival.

In a 2005 issue of the Quarterly Review of Biology, evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson and his colleague Matthew Gervais, both then at Binghamton University, S.U.N.Y., offered an explanation of the evolutionary benefits of humor. Wilson is a major proponent of group selection, an evolutionary theory based on the idea that in social species like ours, natural selection favors characteristics that foster the survival of the group, not just of individuals

Wilson is a major proponent of group selection, an evolutionary theory based on the idea that in social species like ours, natural selection favors characteristics that foster the survival of the group, not just of individuals

Wilson and Gervais applied the concept of group selection to two different types of human laughter. Spontaneous, emotional, impulsive and involuntary laughter is a genuine expression of amusement and joy and is a reaction to playing and joking around; it shows up in the smiles of a child or during roughhousing or tickling. This display of amusement is called Duchenne laughter, after scholar Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne de Boulogne, who first described it in the mid-19th century. Conversely, non-Duchenne laughter is a studied and not very emotional imitation of spontaneous laughter. People employ it as a voluntary social strategy—for example, when their smiles and laughter punctuate ordinary conversations, even when those chats are not particularly funny.

Facial expressions and the neural pathways that control them differ between the two kinds of laughter, the authors say. Duchenne laughter arises in the brain stem and the limbic system (responsible for emotions), whereas non-Duchenne laughter is controlled by the voluntary premotor areas (thought to participate in planning movements) of the frontal cortex. The neural mechanisms are so distinct that just one pathway or the other is affected in some forms of facial paralysis. According to Wilson and Gervais, the two forms of laughter, and the neural mechanisms behind them, evolved at different times. Spontaneous laughter has its roots in the games of early primates and in fact has features in common with animal vocalizations. Controlled laughter may have evolved later, with the development of casual conversation, denigration and derision in social interactions.

Ultimately, the authors suggest, primate laughter was gradually co-opted and elaborated through human biological and cultural evolution in several stages. Between four and two million years ago Duchenne laughter became a medium of emotional contagion, a social glue, in long-extinct human ancestors; it promoted interactions among members of a group in periods of safety and satiation. Laughter by group members in response to what Wilson and Gervais call protohumor—nonserious violations of social norms—was a reliable indicator of such relaxed, safe times and paved the way to playful emotions.

Between four and two million years ago Duchenne laughter became a medium of emotional contagion, a social glue, in long-extinct human ancestors; it promoted interactions among members of a group in periods of safety and satiation. Laughter by group members in response to what Wilson and Gervais call protohumor—nonserious violations of social norms—was a reliable indicator of such relaxed, safe times and paved the way to playful emotions.

When later ancestors acquired more sophisticated cognitive and social skills, Duchenne laughter and protohumor became the basis for humor in all its most complex facets and for new functions. Now non-Duchenne laughter, along with its dark side, appeared: strategic, calculated, and even derisory and aggressive.

Over the years additional theories have proposed different explanations for humor’s role in evolution, suggesting that humor and laughter could play a part in the selection of sexual partners and the damping of aggression and conflict.

Spot the Mistake

One of the more recent proposals appears in a 2011 book dedicated to an evolutionary explanation of humor, Inside Jokes: Using Humor to Reverse-Engineer the Mind (MIT Press, 2011), by Matthew M. Hurley of Indiana University Bloomington, Daniel C. Dennett (a prominent philosopher at Tufts University) and Reginal Adams, Jr., of Pennsylvania State University. The book grew out of ideas proposed by Hurley.

Hurley was interested, he wrote on his website, in a contradiction. “Humor is related to some kind of mistake. Every pun, joke and comic incident seemed to contain a fool of some sort—the ‘butt’ of the joke,” he explained. And the typical response is enjoyment of the idiocy—which “makes sense when it is your enemy or your competition that is somehow failing but not when it is yourself or your loved ones. ” This observation led him to ask, “Why do we enjoy mistakes?” and to propose that it is not the mistakes per se that people enjoy. It is the “emotional reward for discovering and thus undoing mistakes in thought. We don’t enjoy making the mistakes, we enjoy weeding them out.”

” This observation led him to ask, “Why do we enjoy mistakes?” and to propose that it is not the mistakes per se that people enjoy. It is the “emotional reward for discovering and thus undoing mistakes in thought. We don’t enjoy making the mistakes, we enjoy weeding them out.”

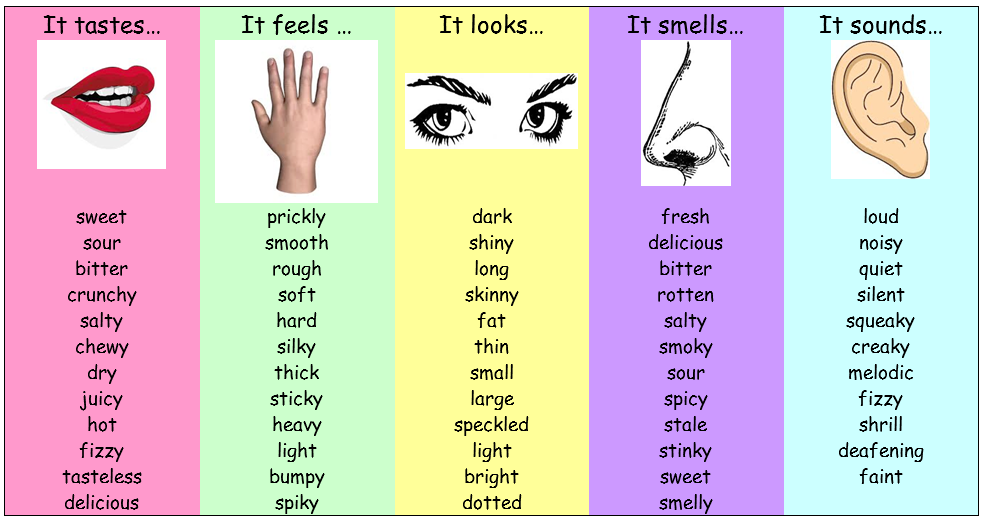

Hurley’s thesis is that our mind continuously makes rule-of-thumb conjectures about what will be experienced next and about the intentions of others. The idea is that humor evolved from this constant process of confirmation: people derive amusement from finding discrepancies between expectations and reality when the discrepancies are harmless, and this pleasure keeps us looking for such discrepancies. (To wit: “I was wondering why the Frisbee was getting bigger, and then it hit me.”) Moreover, laughter is a public sign of our ability to recognize discrepancies. It is a sign that elevates our social status and allows us to attract reproductive partners.

In other words, a joke is to the sense of humor what a cannoli (loaded with fat and sugar) is to the sense of taste. It is a “supernormal” stimulus that triggers a burst of sensual pleasure—in this case, as a result of spotting mistakes. And because grasping the incongruities requires a store of knowledge and beliefs, shared laughter signals a commonality of worldviews, preferences and convictions, which reinforces social ties and the sense of belonging to the same group. As Hurly told psychologist Jarrett in 2013, the theory goes beyond predicting what makes people laugh. It also explains humor’s cognitive value and role in survival.

It is a “supernormal” stimulus that triggers a burst of sensual pleasure—in this case, as a result of spotting mistakes. And because grasping the incongruities requires a store of knowledge and beliefs, shared laughter signals a commonality of worldviews, preferences and convictions, which reinforces social ties and the sense of belonging to the same group. As Hurly told psychologist Jarrett in 2013, the theory goes beyond predicting what makes people laugh. It also explains humor’s cognitive value and role in survival.

And yet, as Greengross noted in a review of Inside Jokes, even this theory is incomplete. It answers some questions, but it leaves others unresolved—for example, “Why does our appreciation of humor and enjoyment change depending on our mood or other situational conditions?”

Giovannantonio Forabosco, a psychologist and an editor at an Italian journal devoted to studies of humor (Rivista Italiana di Studi sull’Umorismo, or RISU), agrees: “We certainly haven’t heard the last word,” he says.

Unanswered Questions

Other questions remain. For instance, how can the sometimes opposite functions of humor, such as promoting social bonding and excluding others with derision, be reconciled? And when laughter enhances feelings of social connectedness, is that effect a fundamental function of the laughter or a mere by-product of some other primary role (much as eating with people has undeniable social value even though eating is primarily motivated by the need for nourishment)?

There is much evidence for a fundamental function. Robert Provine of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, showed in Current Directions in Psychological Science, for example, that individuals laugh 30 times more in the company of others than they do alone. In his research, he and his students surreptitiously observed spontaneous laughter as people went about their business in settings ranging from the student union to shopping malls.

Forabosco notes that there is also some confusion about the relation between humor and laughter: “Laughter is a more social phenomenon, and it occurs for reasons other than humor, including unpleasant ones. Moreover, humor does not always make us laugh.” He notes the cases where a person is denigrated or where an observation seems amusing but does not lead to laughter.

Moreover, humor does not always make us laugh.” He notes the cases where a person is denigrated or where an observation seems amusing but does not lead to laughter.

A further lingering area of debate concerns humor’s role in sexual attraction and thus reproductive success. In one view, knowing how to be funny is a sign of a healthy brain and of good genes, and consequently it attracts partners. Researchers have found that men are more likely to be funny and women are more likely to appreciate a good sense of humor, which is to say that men compete for attention and women do the choosing. But views, of course, differ on this point.

Even the validity of seeking a unified theory of humor is debated. “It is presumptuous to think about cracking the secret of humor with a unified theory,” Forabosco says. “We understand many aspects of it, and now the neurosciences are helping to clarify important issues. But as for its essence, it’s like saying, ‘Let’s define the essence of love. ’ We can study it from many different angles; we can measure the effect of the sight of the beloved on a lover’s heart rate. But that doesn’t explain love. It’s the same with humor. In fact, I always refer to it by describing it, never by defining it.”

’ We can study it from many different angles; we can measure the effect of the sight of the beloved on a lover’s heart rate. But that doesn’t explain love. It’s the same with humor. In fact, I always refer to it by describing it, never by defining it.”

Still, certain commonalities are now accepted by almost all scholars who study humor. One, Forabosco notes, is a cognitive element: perception of incongruity. “That’s necessary but not sufficient,” he says, “because there are incongruities that aren’t funny.” So we have to see what other elements are involved. To my mind, for example, the incongruity needs to be relieved without being totally resolved; it must remain ambiguous, something strange that is never fully explained.”

Other cognitive and psychological elements can also provide some punch. These, Forabosco says, include features such as aggression, sexuality, sadism and cynicism. They don’t have to be there, but the funniest jokes are those in which they are. Similarly, people tend to see the most humor in jokes that are “very intelligent and very wicked. ”

”

“What is humor? Maybe in 40 years we’ll know,” Forabosco says. And perhaps in 40 years we’ll be able to explain why he laughs as he says it.

MORE TO EXPLORE

Laughing, Tickling, and the Evolution of Speech and Self. Robert R. Provine in Current Directions in Psychological Science, Vol. 13, No. 6, pages 215–218; December 2004.

The Evolution and Functions of Laughter and Humor: A Synthetic Approach. Matthew Gervais and David Sloan Wilson in Quarterly Review of Biology, Vol. 80, No. 4; pages 395–430; December 2005.

Benign Violations: Making Immoral Behavior Funny. A. Peter McGraw and Caleb Warren in Psychological Science, Vol. 21, No.8, pages 1141–1149; August 2010.

Too Close for Comfort, or Too Far to Care? Finding Humor in Distant Tragedies and Close Mishaps. A. Peter McGraw et al. in Psychological Science, Vol. 23, No. 10; pages 1215–1223; October 2012.

23, No. 10; pages 1215–1223; October 2012.

How Many Psychologists Does It Take ... to Explain a Joke? Christian Jarrett in The Psychologist, Vol. 26, pages 254–259; April 2013.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Giovanni Sabato trained as a biologist and is now a freelance science writer based in Rome. Beyond psychology, biology and medicine, he is interested in the links between science and human rights.

Why We Laugh

Whether it's the giggling of your child or the enthusiastic hollers of a talk show's studio audience, we hear laughter every day. Nothing could be more common. But just because it's common doesn't make laughter any less strange.

For instance, the next time you're at the movies enjoying some comedy blockbuster, listen hard to the laughter around you. Why are all these strangers, in unison, exploding into such weird, gasping, grunting noises? Their laughs may suddenly stop seeming familiar, and more like the inhuman chatter of birds or the screeches of monkeys at the zoo.

Once you start looking at laughter as behavior, it can lead to some odd questions. Why do we do it? Do animals laugh? And why do we expect that any decent James Bond villain will cackle diabolically when revealing his plan for world domination? What's so funny?

To answer these and other mysteries of laughter, WebMD delved into the surprisingly contentious world of laughter research.

Why Do We laugh?

The answer may seem obvious: We laugh when we perceive something funny. But the obvious answer is not correct, at least most of the time.

"Most laughter is not in response to jokes or humor," says Robert R. Provine, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of Maryland Baltimore County. Provine should know. He has conducted a number of studies of laughter and authored the book Laughter: a Scientific Investigation. One of his central arguments is that humor and laughter are not inseparable.

Provine did a survey of laughter in the wild -- he and some graduate students listened in on average conversations in public places and made notes. And in a survey of 1,200 "laugh episodes," he found that only 10%-20% of laughs were generated by anything resembling a joke.

And in a survey of 1,200 "laugh episodes," he found that only 10%-20% of laughs were generated by anything resembling a joke.

The other 80%-90% of comments that received a laugh were dull non-witticisms like, "I'll see you guys later" and "It was nice meeting you, too." So why the laughs?

Provine argues it has to do with the evolutionary development of laughter. In humans, laughter predates speech by perhaps millions of years. Before our human ancestors could talk with each other, laughter was a simpler method of communication, he tells WebMD.

It's also instinctual. "Infants laugh almost from birth," says Steve Wilson, MA, CSP, a psychologist and laugh therapist. "In fact, people who are born blind and deaf still laugh. So we know it's not a learned behavior. Humans are hardwired for laughter."

But perhaps because laughter is so ancient, it's much less precise than language.

"Laughter isn't under our conscious control," says Provine. "We don't choose to laugh in the same way that we choose to speak. " If you've ever had an inopportune laughing fit -- in a lecture, during a high school play, or at a funeral, for instance -- you know that laughter can't always be tamed.

" If you've ever had an inopportune laughing fit -- in a lecture, during a high school play, or at a funeral, for instance -- you know that laughter can't always be tamed.

Laughing Is Contagious

The cynical answer is that sitcoms are so witless and unfunny that we need to be told where the jokes are. But this misses the point. Why does hearing other people laugh make us more likely to laugh ourselves?

Everyone's experienced this on a small scale. Seeing someone in hysterics -- even if you don't know who the person is or why she's laughing -- can set you laughing too. Why?

The answer lies in the evolutionary function of laughter. Laughter is social; it's not a solo activity, says Provine.

"We laugh 30 times as much when we're with other people than we do when we're alone," says Provine.

You might assume that the 'purpose' of a laugh is to express yourself -- to let people know that you think something is funny. But according to a 2005 article published in the Quarterly Review of Biology, the primary function of laughter may not be self-expression. Instead, the purpose of a laugh could be to trigger positive feelings in other people. When you laugh, the people around you might start laughing in response. Soon, the whole group is cheerful and relaxed. Laughter can ease tension and foster a sense of group unity. This could have been particularly important for small groups of early humans.

Instead, the purpose of a laugh could be to trigger positive feelings in other people. When you laugh, the people around you might start laughing in response. Soon, the whole group is cheerful and relaxed. Laughter can ease tension and foster a sense of group unity. This could have been particularly important for small groups of early humans.

In some cases, laughter can in fact become literally contagious. History is dotted with accounts of laughter epidemics. In 1962, in the African country that is now Tanzania, three school girls began to laugh uncontrollably. Within a few months, about 2/3 of the school's students had the symptoms, and the school closed. The contagion spread, and eventually affected about a thousand people in Tanzania and neighboring Uganda. There were no long-lasting effects, but it shows how responsive people can be to seeing another person laugh.

So sitcoms -- or anything else -- seem funnier to us when we hear other people laughing at them. We've evolved to be that way.

Why Do Villains Laugh Diabolically?

Clearly, there are many different types of laughter. The explosion of laughter after being tickled is obviously different from the tight-lipped chuckle you force out of yourself when your boss tells a bad joke.

To account for the differences, some researchers divide laughter into two groups. The first includes spontaneous laughter. The other group includes laughter that is less spontaneous: it includes fake laughter, nervous laughter, and other social laughter that is unconnected to humor.

Some argue that this nonspontaneous laughter might also include a diabolical cackle or the cruel, jeering laughter that we once heard on the playground.

"Laughter does have a dark side," says Provine. "When gangs or groups of militants attack someone, they are often reported to laugh while doing it." It's the sinister aspect of laughter's power to form group cohesion. Sometimes, those bonds can be used to exclude or persecute others.

According to some researchers, these two types of laughter -- spontaneous and nonspontaneous -- actually have different origins in the brain. The spontaneous laughter originates in part from the brainstem, an ancient part of the brain. So it might be a more original form of laughter. The other type of laughter comes from parts of the brain that developed more recently, in evolutionary terms.

Do Animals Laugh?

While humans might fancy themselves as the only animal capable of laughter, evidence suggests otherwise. In fact, apes seem to laugh after a fashion. They make a distinctive open-mouthed 'play face' and pant rapidly.

"The 'ha, ha' noise of human laughter," Provine tells WebMD, "ultimately has its origins in the ritualized panting laughter of our primate ancestors." Some researchers have found laugh-like behavior in other animals, even in the rat.

But it's not just coincidence that all stand-up comics have been human. While they may laugh, animals -- with the possible exceptions of some primates -- don't seem to have a sense of humor.

So if not at jokes, what do animals -- and what did our ancestors -- laugh at? According to Provine, animal "laughter" follows tickling, rough and tumble play, or chasing games. Apes laugh at some of the same things that make infants laugh. While babies aren't known for subtle wit, they will squeal and laugh when you chase them or tickle them. In all likelihood, early adult humans -- before they started telling jokes -- laughed at the same sort of thing.

Which leads us to an interesting conclusion: Since laughter predates speech, the first human laugh predated the first joke by hundreds of thousands or years, if not millions. It's a long time to wait for a punch line.

Dying Laughing

Happily, laughing itself is seldom lethal. But in some people with underlying health conditions, occasionally, jokes can kill. For instance, some unlucky laughers have had heart attacks, strokes, and embolisms when cracking up.

According to Provine, there is some historical evidence that tickling was used as a method of torture and execution in centuries past. In one reported and exceedingly bizarre technique, a victim was tied up and the soles of his feet were covered with salt. A goat was then brought in to lick the salt, causing intense tickling. If kept up for long enough, the stress and exertion of laughing -- and squirming -- could have eventually brought on cardiac arrest or a brain hemorrhage.

In one reported and exceedingly bizarre technique, a victim was tied up and the soles of his feet were covered with salt. A goat was then brought in to lick the salt, causing intense tickling. If kept up for long enough, the stress and exertion of laughing -- and squirming -- could have eventually brought on cardiac arrest or a brain hemorrhage.

Using 'Laugh Therapy'

We've all heard the claim that 'laughter is the best medicine.' And according to many media reports, laughter is a panacea that will heal your immune system, dull your pain, improve your memory, lower blood pressure, and perform other wondrous feats.

But does this mean that, soon, insurance companies will start covering your movie tickets to HMO-approved comedies? Is laughter really the best, or for that matter, any kind of medicine?

The research isn't clear. But nonetheless, the last few decades have witnessed the rise of "laugh therapy" and other approaches that are based on the notion that laughter is healing.

Wilson is a proponent. He calls himself a "joyologist" and teaches people, business groups, and aspiring laugh therapists how to laugh.

Some other laugh therapists might dress as clowns or sell CDs of themselves telling jokes to the laughless. Of course, if being hilarious is so easy for anyone with a certificate in laugh therapy, why do professional comics like Dave Chappelle get $50 million contracts?

This hits on one problem with a treatment based on humor -- it doesn't account for taste. Some people like Adam Sandler; others would rather put their heads in a vise than see one of his films. Humor is a very subjective thing.

Wilson gets around the troublesome issue of taste by skipping the jokes.

"I don't use humor," he says. Instead, he just starts encouraging people to laugh. And because laughter is contagious, they do.

When Wilson leads a group, he aims to produce a spontaneous, unforced mirthful laugh, which he believes may have health benefits. "It can be almost trance-like," he says. He fuses his approach with some eastern, yoga-like traditions that he claims are "probably about 5,000 years old." He says that people in his class can laugh for as long as two to three hours.

"It can be almost trance-like," he says. He fuses his approach with some eastern, yoga-like traditions that he claims are "probably about 5,000 years old." He says that people in his class can laugh for as long as two to three hours.

Laughter for Your Health

However, Provine says he is skeptical about the health benefits of laughter. "I don't mean to sound like a curmudgeon," says Provine, "but the evidence that laughter has health benefits is iffy at best."

He says most studies of laughter have been small and problematically conducted. He also says that the bias of the researchers is too evident; they want to prove that laughter has benefits. After all, we'd all like to believe that good-humored, happy people are rewarded with long lives. Who wants to believe that being a boring, mirthless jerk is the surefire way to live past 100?

Provine also points out that it's difficult to separate the effects of laughter, specifically, from all of the other things that go with it.

"It's part of a larger picture," says Provine. "Laughter is social, so any health benefits might really come from being close with friends and family, and not the laughter itself."

Wilson agrees that there are limits to what we know about the benefits of laughter.

"Laughing more could make you healthier, but we don't know," he says. "I certainly wouldn't want people to start laughing more just to avoid dying -- because sooner or later, they'll be disappointed."

But he and Provine agree that whether laughter actually improves your health or not, it undeniably improves your quality of life.

"Obviously, I'm not antilaughter," says Provine. "I'm just saying that if we enjoy laughing, isn't that reason enough to laugh? Do you really need a prescription?"

Where does laughter come from and why do people laugh at all

Why do we laugh? How is laughter born? Can it be controlled? On April Fool's Day, we asked MD, Professor of the Department of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Medical Genetics, Faculty of Pediatrics, Russian National Research Medical University. N. I. Pirogov Khondrakyan Garegin to answer these questions.

N. I. Pirogov Khondrakyan Garegin to answer these questions.

Laughter is a physiological feature inherent in every person from his very birth. This is one of our distinguishing features. Laughter is an indicator of positive emotions, a symptom of good mood. The mechanism of laughter is triggered not only by a joke heard or the realization that the situation is funny, but also by the desire to get closer to a person or show that we understand each other and we are pleased with the interlocutor. Laughter is a universal way of communication, understandable to everyone and having no speech barrier. nine0003

What happens in the brain during laughter

From the point of view of physiology, laughter is a motor act that involves contraction of the diaphragm and is accompanied by the work of a vocal phenomenon (vocalization). Laughter is localized in the trunk (in other words, in the bridge) of the brain. The organization of laughter involves the cerebellum, which coordinates any movement of a person, the midbrain and such a complex structure of the brain as the hypothalamus (regulates the neuroendocrine activity of the brain and homeostasis of the body). The hypothalamus is connected by nerve pathways to the entire central nervous system. The command to laugh is formed in the cerebral cortex - with the participation of the frontal and temporal lobes. The temporal lobe is responsible for instinctive behavior, for recognition. Thus, we can conclude: the physiology of laughter is a simultaneous inseparable coordinated work of the entire brain, which cannot be divided. nine0003

The hypothalamus is connected by nerve pathways to the entire central nervous system. The command to laugh is formed in the cerebral cortex - with the participation of the frontal and temporal lobes. The temporal lobe is responsible for instinctive behavior, for recognition. Thus, we can conclude: the physiology of laughter is a simultaneous inseparable coordinated work of the entire brain, which cannot be divided. nine0003

Laughter is directly controlled by emotions, their modulation. The limbic system (from lat. limbus - “border, edge”) is responsible for instinctive behavior and for our mood level, it is localized in the temporal lobe. The mechanism responsible for emotions is scattered throughout the brain: partly in the cortex, partly in the temporal lobe. Emotions or instinctive behavior have been passed down to us from the animal world. Memories that are emotionally charged are remembered best, so we can laugh in private by recalling them with memory. nine0003

Why laughter happens through tears

A phenomenon close to laughter is crying. So, the baby at the initial stage of his life cries easily and laughs easily. The rapid triggering of these similar mechanisms in a child can easily be explained by an immature brainstem system that is poorly controlled by the cerebral cortex. With strong laughter, there is a great activity of this zone, the structure of tears lying next to it is affected, and in this case, the lacrimal canal opens through the large stony nerve. Therefore, it is quite physiological to laugh and cry at the same time. Convulsive vocal movements are also similar: laughter has laughter, crying has sobs. nine0003

So, the baby at the initial stage of his life cries easily and laughs easily. The rapid triggering of these similar mechanisms in a child can easily be explained by an immature brainstem system that is poorly controlled by the cerebral cortex. With strong laughter, there is a great activity of this zone, the structure of tears lying next to it is affected, and in this case, the lacrimal canal opens through the large stony nerve. Therefore, it is quite physiological to laugh and cry at the same time. Convulsive vocal movements are also similar: laughter has laughter, crying has sobs. nine0003

When we realize we need to stop laughing

The most important role is played by the brake mechanism, which gives a command about the appropriateness of laughter and keeps it under control. When we understand humor or a joke, the brain gives the command to laugh, but at the same time it can slow down this laughter. Damage in any part of the brain gives an instant failure in the mechanism of inhibition. Then there is inappropriate laughter - violent. Disinhibition of reflexes causes violent (pathological) laughter, for example, with damage to the cerebellum (stroke). It is interesting to note that with age we laugh less - as in any mechanical act, year after year, the braking system works more and more. This pattern concerns not only laughter. For example, in the prime of life, we move a lot, the body performs a lot of movements, even if they are not required, but an elderly person spends his strength economically and accurately. nine0003

Then there is inappropriate laughter - violent. Disinhibition of reflexes causes violent (pathological) laughter, for example, with damage to the cerebellum (stroke). It is interesting to note that with age we laugh less - as in any mechanical act, year after year, the braking system works more and more. This pattern concerns not only laughter. For example, in the prime of life, we move a lot, the body performs a lot of movements, even if they are not required, but an elderly person spends his strength economically and accurately. nine0003

Why do we find it funny when others laugh

Often we see the mechanism of contagious laughter, in which a group of people laughs, but each individual person cannot understand what the humor is. In this case, the so-called induction behavior of the crowd is triggered, which activates the systems of the brain responsible for laughter.

Do we enjoy laughter? No, we get pleasure from a joke, from humor, from an absurd situation that raise our mood. Actually, high spirits is pleasure. nine0003

Actually, high spirits is pleasure. nine0003

Low mood (dysthymia) or a state of mild depression is a feature of a particular person associated with a personality type. It can accompany him through life without connection with the environment and for obvious reasons.

Forced triggering of the nervous system through activities such as running, fighting, fear and sex prevents triggering the laughter mechanism.

Is it true that laughter prolongs life

The stereotype that laughter supposedly prolongs life has no evidence base. Often we hear that some mythical British scientists have proven something, but this is only a crude and unproven theory. Such serious statements can be made only after a long study. You need to take a group of people of the same age, the same sex, divide it into two subgroups - just mix some, and not others. And only at the end of the life of the participants in the experiment, comparing the years of their life, calculate by what coefficient their life has increased and whether it has increased. So far, no research institute has conducted such a study. nine0003

So far, no research institute has conducted such a study. nine0003

Subscribe to The Challenger!

Why do we laugh? - TV channel "Nauka"

How and why man learned to laugh

Man is the only one among primates who laughs only when he exhales. Scientists believe that this is the result of speech control, which develops in people with age. But why do we even need to laugh? What is laughter in terms of evolution and physiology? Let's figure it out with the help of scientists. nine0072

The evolution of laughter

Biologists at Binghamton University believe that human laughter originated from monkeys' playful panting, a social habit that primates developed between 4 and 2 million years ago. Shared laughter became a way of community play during our ancestors' fleeting periods of security. Experts believe that this was the era of the birth of humor.

Shared laughter became a way of community play during our ancestors' fleeting periods of security. Experts believe that this was the era of the birth of humor.

A recent study by the American Acoustic Society found that babies and chimpanzees still laugh in the same way: making sounds both inhaling and exhaling. When children grow up and learn to speak, they begin to laugh only on the exhale, as their parents do. nine0003

Neuropsychological and behavioral research has shown that laughter is more than just a spontaneous response to stimuli. About 2 million years ago, human ancestors developed the ability to consciously control the motor systems of the face. As a result, laughter began to perform various functions: it serves to convey feelings, helps to place accents in speech, express embarrassment, friendliness, and set the interlocutor in a benevolent mood. A nervous laugh occurs in an uncomfortable situation: with its help, a person tries to get out of a difficulty, relieve tension. At the same time, laughter can be mocking or threatening, serving to ridicule the interlocutor. nine0003

At the same time, laughter can be mocking or threatening, serving to ridicule the interlocutor. nine0003

The reasons why people laugh change with age. In infants and young children, as in non-human primates, laughter is born as a result of physical play such as tickling. From being tickled, not only all monkeys laugh, but even rats - however, we do not hear their laughter: this is an ultrasonic signal with a frequency of 50 kHz.

As a person grows older, his laughter also matures: it can arise not only as a result of physical play, but also social interactions, understanding jokes - from anecdotes to subtle intellectual humor. Laughing alone is not at all as fun as sitting in the hall at a comedy show, where every joke causes an explosion of laughter and the audience goes into a general hysteria. Scientists have calculated that in the presence of other people, a person laughs 30 times more. nine0003

Sharing laughter releases endorphins in the brain, which promotes social bonding, togetherness and security. This conclusion was recently reached by researchers from the Finnish University of Turku. During the experiment, they noticed that participants who had more opioid receptors in their brains laughed more often and more readily than others.

This conclusion was recently reached by researchers from the Finnish University of Turku. During the experiment, they noticed that participants who had more opioid receptors in their brains laughed more often and more readily than others.

Man is a social being. He is easily "infected" with other people's laughter, and this leads to a similar reaction in the brain, and therefore people who laugh together experience the same emotions, which contributes to the formation of friendship, affection, and love. nine0003

Physiology of laughter

From the point of view of physiology, laughter is a motor act during which the diaphragm contracts and characteristic vocalization occurs. It involves several areas of the brain at once: the temporal lobe, cerebellum, midbrain, hypothalamus, brain stem and cortex. In this complex mechanism, some zones are responsible for processing information that seems funny, others send signals for a reaction, and still others allow you to inhibit laughter activity if it is inappropriate or dangerous. Certain disorders in the brain can interfere with the ludicrous process. For example, disinhibitory damage to the corticobulbar tract leads to pathological laughter when the person cannot stop. nine0003

Certain disorders in the brain can interfere with the ludicrous process. For example, disinhibitory damage to the corticobulbar tract leads to pathological laughter when the person cannot stop. nine0003

Laughter and crying are of a similar nature: they are accompanied by respiratory spasms and convulsive vocal movements. With strong laughter, brain signals affect the area responsible for tears: the lacrimal canal opens through the large stony nerve, and in this case we cry and laugh at the same time.

Laughing is useful not only because of the production of endorphins and getting positive emotions, but also because at this time there is an active saturation of the body with oxygen, metabolic processes are accelerated, and the level of stress hormones decreases. Scientists have experienced that even the anticipation of a comedy show or a funny movie affects the level of cortisol, adrenaline and dopamine, reducing them by 39%, 70% and 38% respectively. That's why laughter is really good for your health and why it's so important to be non-serious.