Video games help with depression

Do They Have Mental Health Benefits?

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

Medically Reviewed by Dan Brennan, MD on October 25, 2021

In this Article

- Benefits of Video Games

- Playing for Your Well-Being

- Limits of Video Games as a Mood Booster

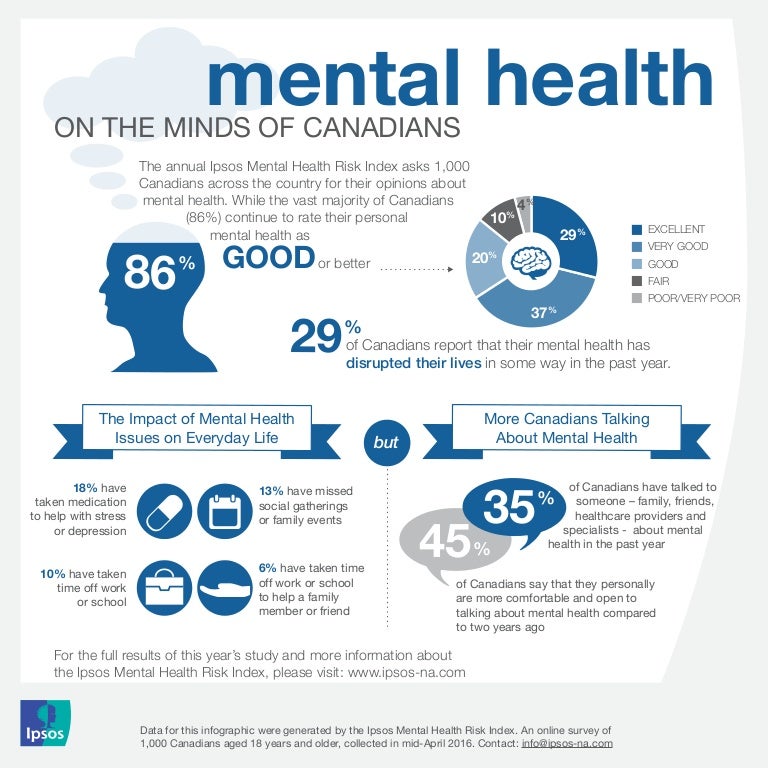

There are many misconceptions about video games and the impact they have on mental health. The truth is that video games have many benefits, including developing complex problem-solving skills and promoting social interaction through online gaming. Video games can be a great way to stimulate your mind and improve your mental health.

Benefits of Video Games

Playing video games has numerous benefits for your mental health. Video games can help you relieve stress and get your mind going. Some benefits include:

Mental stimulation. Video games often make you think. When you play video games, almost every part of your brain is working to help you achieve higher-level thinking. Depending on the complexity of the game, you may have to think, strategize, and analyze quickly. Playing video games works with deeper parts of your brain that improve development and critical thinking skills.

Feeling accomplished. In the game, you have goals and objectives to reach. Once you achieve them, they bring you a lot of satisfaction, which improves your overall well-being. This sense of achievement is heightened when you play games that give you trophies or badges for certain goals. Trying to get more achievements gives you something to work toward.

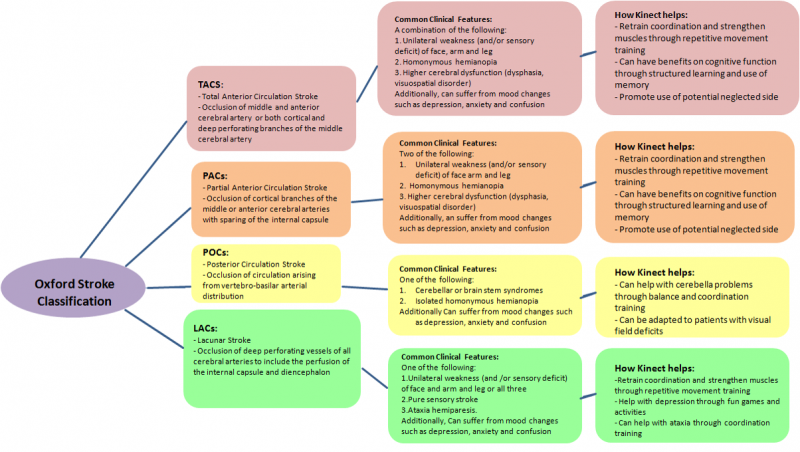

Mental health recovery. Regardless of the type, playing games can help with trauma recovery. Video games can act as distractions from pain and psychological trauma. Video games can also help people who are dealing with mental disorders like anxiety, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

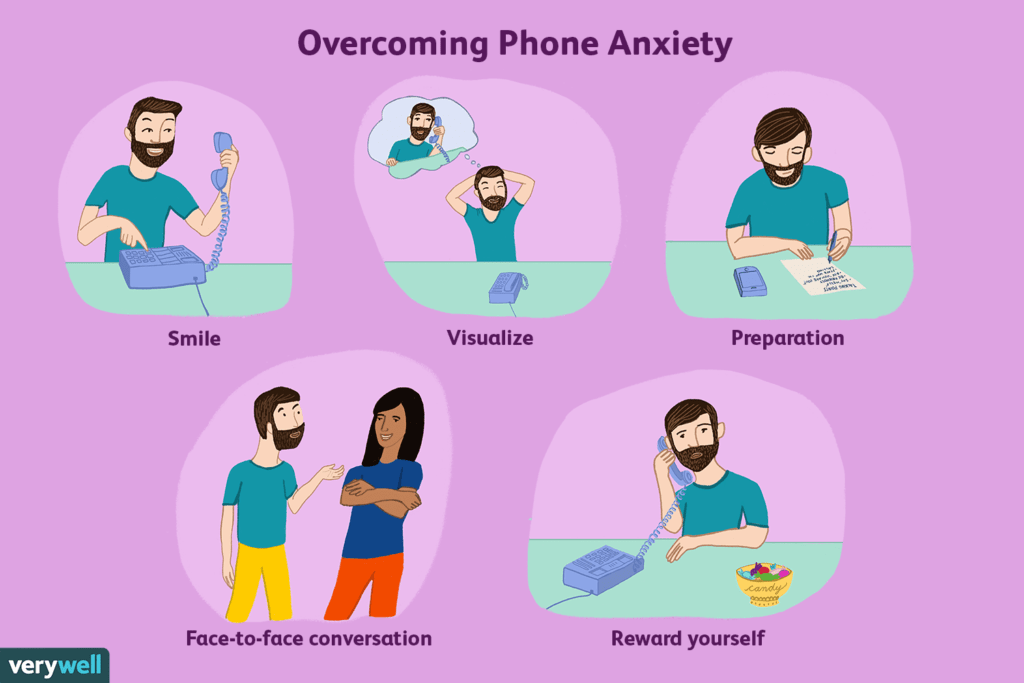

Social interaction. Multiplayer and online games are good for virtual social interaction. In fast-paced game settings, you’ll need to learn who to trust and who to leave behind within the game. Multiplayer games encourage cooperation. It’s also a low-stakes environment for you to test out talking to and fostering relationships with new people.

Multiplayer and online games are good for virtual social interaction. In fast-paced game settings, you’ll need to learn who to trust and who to leave behind within the game. Multiplayer games encourage cooperation. It’s also a low-stakes environment for you to test out talking to and fostering relationships with new people.

Emotional resilience. When you fail in a game or in other situations, it can be frustrating. Video games help people learn how to cope with failure and keep trying. This is an important tool for children to learn and use as they get older.

Despite what people may think, playing video games boosts your mood and has lasting effects. Whether you’re using gaming to spend time with your friends or to release some stress, it's a great option.

Playing for Your Well-Being

Playing video games has been linked to improved moods and mental health benefits. It might seem natural to think that violent video games like first-person shooters aren’t good for your mental health. However, all video games can be beneficial for different reasons.

However, all video games can be beneficial for different reasons.

Try strategic video games. Role-playing and other strategic games can help strengthen problem-solving skills. There’s little research that says violent video games are bad for your mental health. Almost any game that encourages decision-making and critical thinking is beneficial for your mental health.

Set limits. Though video games themselves aren’t bad for your mental health, becoming addicted to them can be. Spending too much time gaming can lead to isolation. You may also not want to be around people in the real world. When you start to feel yourself using video games as an escape, you might need to slow down.

If you can’t stop playing video games on your own, you can contact a mental health professional.

Play with friends. Make game time fun by playing with friends. There are online communities you can join for your favorite games. Moderate gaming time with friends can help with socialization, relaxation, and managing stress.

Limits of Video Games as a Mood Booster

Video games stop being good for you when you play an excessive amount. More than 10 hours per week is considered “excessive.” In these cases, you may:

- Have anxious feelings

- Be unable to sleep

- Not want to be in social settings

Another troubling sign is using video games to escape real life. As noted above, this type of behavior can lead to video game addiction, which then leads to other negative behaviors. Too much gaming can become a problem, but in moderation, it can do great things for your mental health.

Winning The Game Against Depression: A Systematic Review of Video Games for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders

1. Depression WH. Other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

2. Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Porras-Segovia A, Dunne H, Andrade-González N, Cervilla JA. Prevalence and correlates of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(6):657–672. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42(6):657–672. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-0650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Short NA, Boffa JW, Clancy K, Schmidt NB. Effects of emotion regulation strategy use in response to stressors on PTSD symptoms: An ecological momentary assessment study. J Affect Disord. 2018;1(230):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.063. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. McHugh RK, Weiss RD. Alcohol use disorder and depressive disorders. Alcohol research: current reviews. 2019;40(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

5. Rivera M, Porras-Segovia A, Rovira P, Molina E, Gutiérrez B, Cervilla J. Associations of major depressive disorder with chronic physical conditions, obesity and medication use: Results from the PISMA-ep study. Eur Psychiatry. 2019;60:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.04.008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Meister R, Jansen A, Berger M. Psychotherapie depressiver Störungen-Verfahren. Evidenz und Perspektiven Nervenarzt. 2018;89(3):241–251. doi: 10.1007/s00115-018-0484-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2018;89(3):241–251. doi: 10.1007/s00115-018-0484-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Britt TW, Greene-Shortridge TM, Brink S, Nguyen QB, Rath J, Cox AL, Hoge CW, Castro CA. Perceived stigma and barriers to care for psychological treatment: Implications for reactions to stressors in different contexts. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2008;27(4):317–335. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.4.317. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Howard I, Julian L, Vella L, Catledge C, Feldman MD. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32(3):254–258. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3203_12. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Davies EB, Morriss R, Glazebrook C. Computer-delivered and web-based interventions to improve depression, anxiety, and psychological well-being of university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e130. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

10. Sztein DM, Koransky CE, Fegan L, Himelhoch S. Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy delivered over the Internet for depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(8):527–539. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17717402. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy delivered over the Internet for depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24(8):527–539. doi: 10.1177/1357633X17717402. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Price M, Yuen EK, Goetter EM, Herbert JD, Forman EM, Acierno R, Ruggiero KJ. mHealth: a mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2014;21(5):427–436. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1855. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Porras-Segovia A, Díaz-Oliván I, Gutiérrez-Rojas L, Dunne H, Moreno M, Baca-García E. Apps for Depression: Are They Ready to Work? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(3):11. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-1134-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Abd El-Sattar HK. A Novel Interactive Computer-Based Game Framework: From Design to Implementation. In2008 International Conference Visualisation 2008 Jul 9 (pp. 123-128). IEEE.

14. Lumsden J, Edwards EA, Lawrence NS, Coyle D, Munafò MR. Gamification of cognitive assessment and cognitive training: a systematic review of applications and efficacy. JMIR serious games. 2016;4(2):e11. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Gamification of cognitive assessment and cognitive training: a systematic review of applications and efficacy. JMIR serious games. 2016;4(2):e11. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

15. Gamify. What is Gamification? Education, Business & Marketing (2021 Examples). Gamify.com. https://www.gamify.com/what-is-gamification. Published 2021. Accessed November 13, 2021.

16. Penuelas-Calvo I, Jiang-Lin LK, Girela-Serrano B, Delgado-Gomez D, Navarro-Jimenez R, Baca-Garcia E, Porras-Segovia A. Video games for the assessment and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review. European child & adolescent psychiatry. 2020 May 18:1-6. [PubMed]

17. Fang Q, Aiken CA, Fang C, Pan Z. Effects of exergaming on physical and cognitive functions in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Games for health journal. 2019;8(2):74–84. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2018.0032. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Barnes S, Prescott J. Empirical evidence for the outcomes of therapeutic video games for adolescents with anxiety disorders: systematic review. JMIR serious games. 2018;6(1):e3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

JMIR serious games. 2018;6(1):e3. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

19. Primack BA, Carroll MV, McNamara M, Klem ML, King B, Rich M, Chan CW, Nayak S. Role of video games in improving health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(6):630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.023. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Li J, Theng YL, Foo S. Effect of exergames on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19(1):34–42. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0366. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Pine R, Fleming T, McCallum S, Sutcliffe K. The effects of casual videogames on anxiety, depression, stress, and low mood: A systematic review. Games Health J. 2020. [PubMed]

22. Fleming TM, Bavin L, Stasiak K, Hermansson-Webb E, Merry SN, Cheek C, Lucassen M, Lau HM, Pollmuller B, Hetrick S. Serious games and gamification for mental health: current status and promising directions. Front Psych. 2017;10(7):215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart L, PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349(jan02 1):g7647. [PubMed]

24. Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011; 343(7829). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

25. • Cheek C, Bridgman H, Fleming T, Cummings E, Ellis L, Lucassen MF, Shepherd M, Skinner T. Views of young people in rural Australia on SPARX, a fantasy world developed for New Zealand youth with depression. JMIR Serious Games. 2014;2(1):e3. In this study, they explored the acceptability of SPARX in the youth rural Australian population and found positive attitude for the use of this video game. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

26. Grant S, Spears A, Pedersen ER. Video Games as a Potential Modality for Behavioral Health Services for Young Adult Veterans: Exploratory Analysis. JMIR serious games. 2018;6(3):e15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Video Games as a Potential Modality for Behavioral Health Services for Young Adult Veterans: Exploratory Analysis. JMIR serious games. 2018;6(3):e15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

27. Knox M, Lentini J, Cummings TS, McGrady A, Whearty K, Sancrant L. Game-based biofeedback for paediatric anxiety and depression. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011;8(3):195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Kühn S, Berna F, Lüdtke T, Gallinat J, Moritz S. Fighting depression: action video game play may reduce rumination and increase subjective and objective cognition in depressed patients. Front Psychol. 2018;12(9):129. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Merry SN, Stasiak K, Shepherd M, Frampton C, Fleming T, Lucassen MF. The effectiveness of SPARX, a computerised selfhelp intervention for adolescents seeking help for depression: randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Bmj. 2012;344:e2598. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

30. Nouchi R, Saito T, Nouchi H, Kawashima R. Small acute benefits of 4 weeks processing speed training games on processing speed and inhibition performance and depressive mood in the healthy elderly people: evidence from a randomized control trial. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2016;23(8):302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nouchi R, Saito T, Nouchi H, Kawashima R. Small acute benefits of 4 weeks processing speed training games on processing speed and inhibition performance and depressive mood in the healthy elderly people: evidence from a randomized control trial. Frontiers in aging neuroscience. 2016;23(8):302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. • Rodrigues EV, Gallo LH, Guimarães AT, Melo Filho J, Luna BC, Gomes AR. Effects of dance exergaming on depressive symptoms, fear of falling, and musculoskeletal function in fallers and nonfallers community-dwelling older women. Rejuvenation research. 2018;21(6):518–26. This study testes the effect of physical activity in the elderly by using dance video game and founded positive results for both their fitness and depressives symptoms. [PubMed]

32. Rosenberg D, Depp CA, Vahia IV, Reichstadt J, Palmer BW, Kerr J, Norman G, Jeste DV. Exergames for subsyndromal depression in older adults: a pilot study of a novel intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):221–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(3):221–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

33. Russoniello CV, Fish M, O'Brien K. The efficacy of casual videogame play in reducing clinical depression: a randomized controlled study. GAMES FOR HEALTH: Research, Development, and Clinical Applications. 2013;2(6):341–346. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2013.0010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

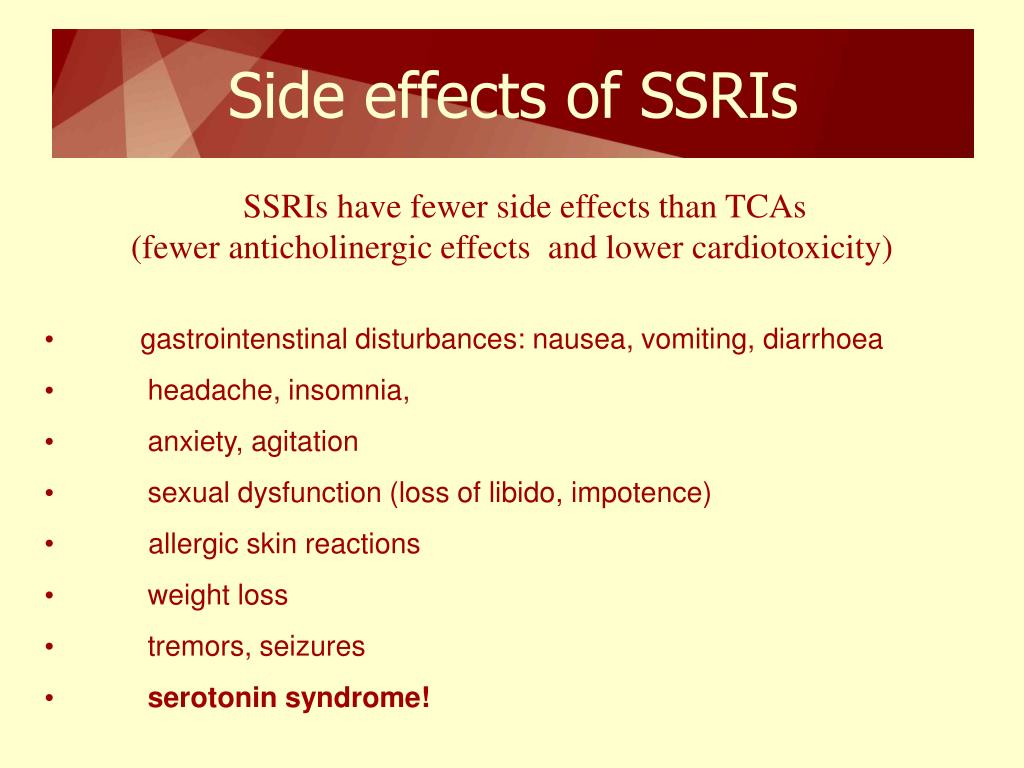

34. • Russoniello CV, Fish MT, O'Brien K. The efficacy of playing videogames compared with antidepressants in reducing treatment-resistant symptoms of depression. Games health J. 2019;8(5):332–8. In this study, they used a casual game for the reduction of treatment resistant depression symptoms and found significant improvement in comparison to those with pharmacotherapy only. [PubMed]

35. • Shepherd M, Fleming T, Lucassen M, Stasiak K, Lambie I, Merry SN. The design and relevance of a computerized gamified depression therapy program for indigenous Māori adolescents. JMIR serious games. 2015;3(1):e1. In this study, they testes whether indigenous community would positively asses the use of video games as a psychotherapeutic treatment for depressives symptoms. Results showed high engagement and acceptability. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

In this study, they testes whether indigenous community would positively asses the use of video games as a psychotherapeutic treatment for depressives symptoms. Results showed high engagement and acceptability. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

36. Tark R, Metelitsa M, Akkermann K, Saks K, Mikkel S, Haljas K. Usability, Acceptability, Feasibility, and Effectiveness of a Gamified Mobile Health Intervention (Triumf) for Pediatric Patients: Qualitative Study. JMIR serious games. 2019;7(3):e13776.) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

37. Zhang A, Borhneimer LA, Weaver A, Franklin C, Hai AH, Guz S, Shen L. Cognitive behavioral therapy for primary care depression and anxiety: a secondary meta-analytic review using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. J Behav Med. 2019;42(6):1117–1141. doi: 10.1007/s10865-019-00046-z. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Christ C, Schouten MJ, Blankers M, van Schaik DJ, Beekman AT, Wisman MA, Stikkelbroek YA, Dekker JJ. Internet and computer-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e17831. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e17831. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

39. Galper DI, Trivedi MH, Barlow CE, Dunn AL, Kampert JB. Inverse association between physical inactivity and mental health in men and women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(1):173–178. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000180883.32116.28. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Pereira SM, Geoffroy MC, Power C. Depressive symptoms and physical activity during 3 decades in adult life: bidirectional associations in a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71(12):1373–1380. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1240. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Porras-Segovia A, Rivera M, Molina E, López-Chaves D, Gutiérrez B, Cervilla J. Physical exercise and body mass index as correlates of major depressive disorder in community-dwelling adults: Results from the PISMA-ep study. J Affect Disord. 2019;15(251):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.01.050. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Morres ID, Hatzigeorgiadis A, Stathi A, Comoutos N, Arpin-Cribbie C, Krommidas C, Theodorakis Y. Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(1):39–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22842. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Aerobic exercise for adult patients with major depressive disorder in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2019;36(1):39–53. doi: 10.1002/da.22842. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Carson V, Hunter S, Kuzik N, Gray CE, Poitras VJ, Chaput JP, Saunders TJ, Katzmarzyk PT, Okely AD, Connor Gorber S, Kho ME. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: an update. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(6):S240–S265. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0630. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Rodriguez-Ayllon M, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Estevez-Lopez F, Munoz NE, Mora-Gonzalez J, Migueles JH, Molina-Garcia P, Henriksson H, Mena-Molina A, Martinez-Vizcaino V, Catena A. Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;1:1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Russo-Neustadt AA, Alejandre H, Garcia C, Ivy AS, Chen MJ. Hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression following treatment with reboxetine, citalopram, and physical exercise. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(12):2189–2199. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300514. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Hippocampal brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression following treatment with reboxetine, citalopram, and physical exercise. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(12):2189–2199. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300514. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Winter B, Breitenstein C, Mooren FC, Voelker K, Fobker M, Lechtermann A, Krueger K, Fromme A, Korsukewitz C, Floel A, Knecht S. High impact running improves learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87(4):597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.11.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Palmefors H, DuttaRoy S, Rundqvist B, Börjesson M. The effect of physical activity or exercise on key biomarkers in atherosclerosis–a systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2014;235(1):150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.04.026. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Kayambu G, Boots R, Paratz J. Early physical rehabilitation in intensive care patients with sepsis syndromes: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(5):865–874. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3763-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3763-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Gelenberg AJ. A review of the current guidelines for depression treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):e15. doi: 10.4088/JCP.9078tx1c. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Tuerk PW, Yoder M, Ruggiero KJ, Gros DF, Acierno R. A pilot study of prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder delivered via telehealth technology. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2010;23(1):116–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Cheung YTD, Spittal M, Pirkis J. Spatial analysis of suicide mortality in Australia: Investigation of metropolitan-rural-remote differentials of suicide risk across states/territories. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1460–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026.[PubMed:22771036][CrossRef:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026]. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Hollis C, Falconer CJ, Martin JL, et al. Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):474–503. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12663. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Annual Research Review: Digital health interventions for children and young people with mental health problems - a systematic and meta-review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):474–503. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12663. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Ma Y. The Discrepancy Between Video Game Purchase and Consumption in A Content Distribution Network. InProceedings Of The 2015 Dec.

video games help treat anxiety and depression

June 18, 2021 17:46

pexels.com

Video games such as Team Fortress 2 and Mario Kart are an inexpensive and effective way to help alleviate a range of mental health problems. This conclusion was made by the specialists of the Research Center of the Science Foundation of Ireland Lero

A new study has disproved the conventional wisdom that video games harm social activity, lead to withdrawal, aggression, anxiety and feelings of loneliness. Fears in this regard only intensified with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many people who found themselves in self-isolation were forced to reduce contact with the outside world.

Fears in this regard only intensified with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many people who found themselves in self-isolation were forced to reduce contact with the outside world.

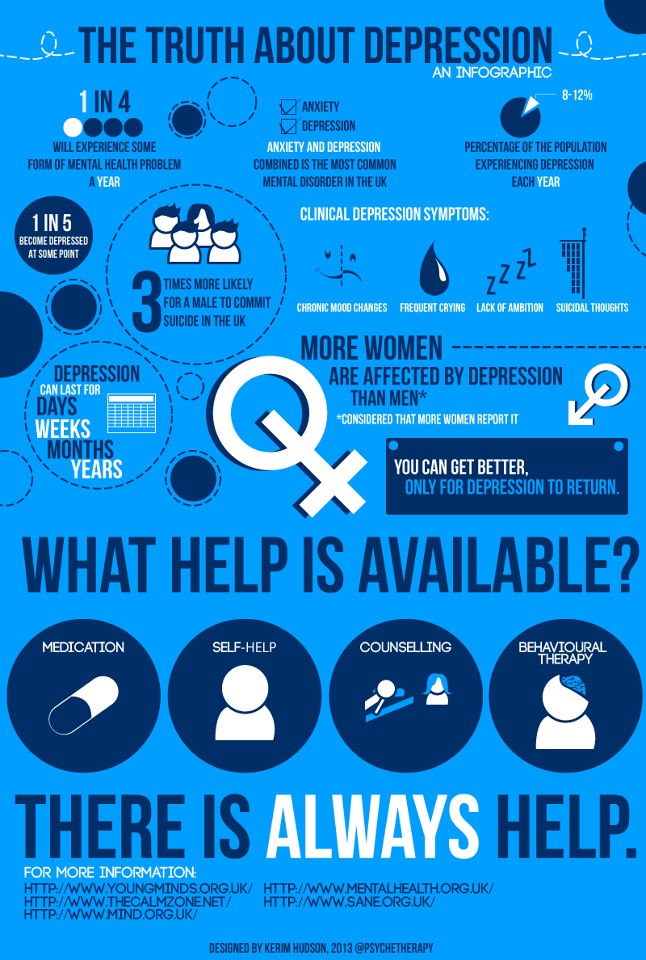

According to the forecast of the World Health Organization (WHO), it is depression that will become the leader among diseases over the next ten years. Already today, more than 350 million people suffer from this disease on the planet. nine0003

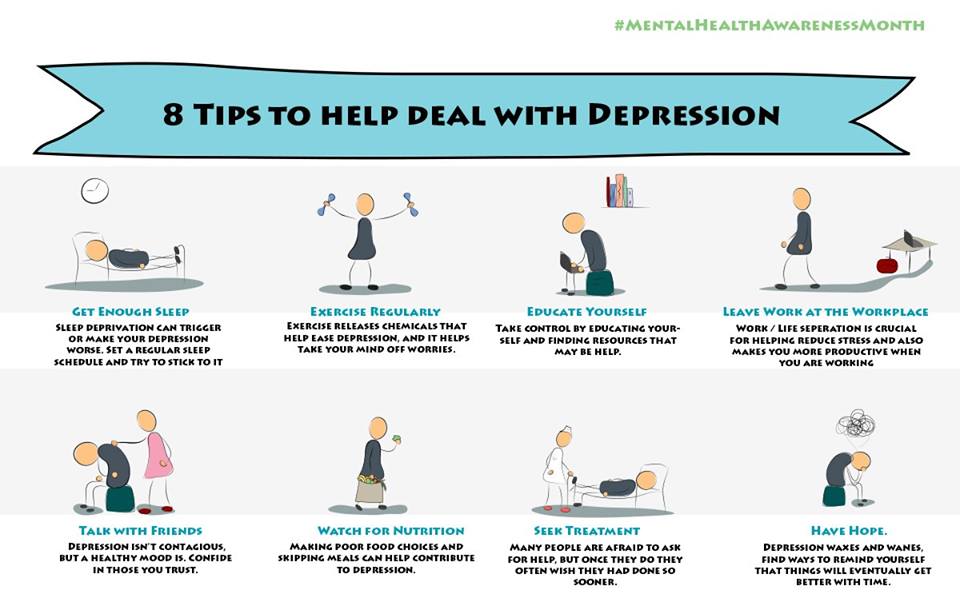

Video games can help with mental illness. Moderate gaming is an inexpensive and effective way to "alleviate a range of mental health problems in the absence of, or in addition to, traditional therapies," Lero, a research center at the Science Foundation of Ireland, found.

The study highlights the benefits of commercial video games (as opposed to those specifically designed to treat depression and neurosis). Such games are widely available and relatively inexpensive, promote socialization and regulation of emotions, increase concentration and craving for new knowledge, and also have a beneficial effect on improving mental health in general. nine0003

nine0003

Strategies, shooters, role-playing and casual games were named ideal for relieving depressed mood. In particular, Team Fortress 2, Mario Kart, Limbo, Rayman, and Candy Crush may be effective in treating mental illness. In general, the scientists concluded, games of any genre can alleviate the symptoms of many mental illnesses and improve the quality of life.

technologies depression psychological help games hi-tech news

Previously related

-

Sony and Honda will release an electric car with a built-in PlayStation 5

-

Chernyshenko instructed to formulate new measures to support the video game industry

-

Russian gamers want to be identified

nine0027 -

Xbox games will become much more expensive

-

PlayStation 5 with Rostest certification appeared on

marketplaces -

A study on the effects of video games on children yielded an unexpected result

nine0048

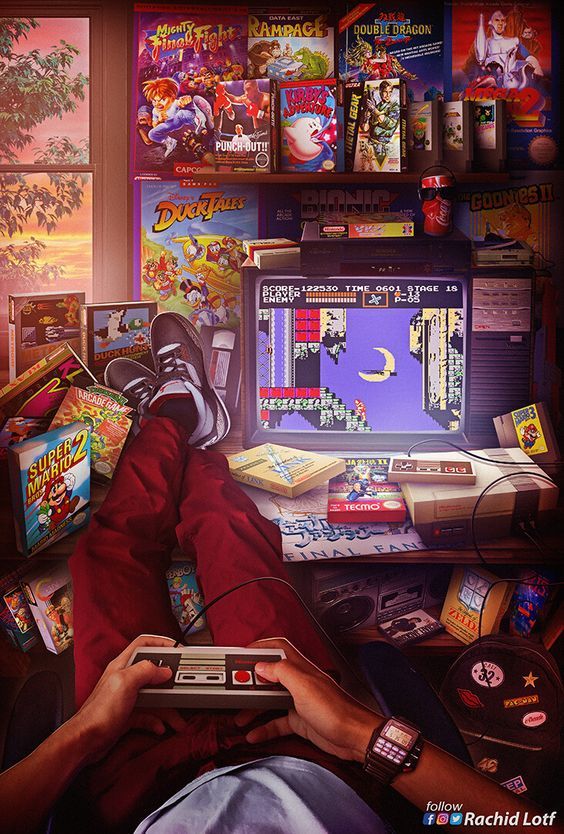

How video games help to avoid depression and develop useful skills

November 19, 2015 Life

Gamers can be proud of themselves: science has proven that games are good for our mind and consciousness. It turns out that with the help of such entertainment, one can reach notable heights in self-development. More importantly, video games stimulate our brain and minimize our chances of developing depression.

It turns out that with the help of such entertainment, one can reach notable heights in self-development. More importantly, video games stimulate our brain and minimize our chances of developing depression.

"All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy," the main character of The Shining typed on a typewriter. Indeed, the concept of "work" is often seen as the antonym of the word "entertainment". However, recent scientific research has proven that the opposite of gaming is depression. nine0003 JD Hancock/Flickr.com

This idea was first proposed by Brian Sutton-Smith, a scientist who devoted his life to studying the psychological aspect of the game. He became famous in the 1950s and 60s when he studied the influence of entertainment on children and adults. Sutton-Smith learned that while playing, people become more confident and energetic, and experience strong positive emotions. In fact, all this is a description of a state that is exactly the opposite of depression, when a person is incredibly pessimistic, especially about his own talents, opportunities and prospects. nine0003

nine0003

Sutton-Smith did most of his research long before scientists were using high-tech brain scan machines to track blood circulation and thus diagnose mental illness. He also worked without knowing that video games would take over our world.

According to statistics, more than 1.23 billion people are addicted to computer games, but, most importantly, we now know what exactly goes on in the minds of these people.

Over the past few years, there have been many studies using functional magnetic resonance therapy. The most notable of these was carried out by Stanford University, which "looked" into the minds of gamers.

The results showed that when we play video games, two areas of our brain are constantly stimulated: the one responsible for motivation and the one that makes us want to achieve new goals.

After all, during such entertainment, we are incredibly focused on the task. It doesn't matter if we are solving difficult problems, trying to find hidden objects, aiming for the finish line or scoring maximum points. Any of these goals completely captures our attention, motivates and forces us to focus. We expect that we will succeed - and the corresponding part of the brain begins to work actively, making us want to win. nine0003 JD Hancock/Flickr.com

Any of these goals completely captures our attention, motivates and forces us to focus. We expect that we will succeed - and the corresponding part of the brain begins to work actively, making us want to win. nine0003 JD Hancock/Flickr.com

Meanwhile, all games (not just educational ones) are designed for people to learn. The first level is always simple, the player is easily drawn into the process, testing various action strategies and his own skills. With each level, the tasks become more difficult, and most games are designed so that the person continues to learn throughout the scenario.

It is the acquisition of new experiences that is the key to the growing interest of the player, and this is the secret of the pleasure of video games. When nothing happens and you are not pushed to learn, the excitement is gone. The person stops playing. nine0003

So, few adults like the classic "tic-tac-toe" - all the winning strategies have already been learned by heart.

But as long as the game requires diligence and diligence from you, the hippocampus will be included in the process, and the player himself will enjoy the passage.

JD Hancock/Flickr.comIf you've ever wondered why, after failing the same level 20 times in a row in Angry Birds, you keep trying again and again, then there is a scientific explanation for this phenomenon. Such enthusiasm is the result of a neurological activation script. For non-gamers, this behavior may seem irrational and intrusive. But this is exactly the kind of steady state that one would expect from a person whose brain is completely focused on achieving the goal. In addition, after passing the level, the gamer becomes more confident, thanks to the knowledge and experience gained. nine0003

And here's the most interesting thing: if a person is clinically depressed, two areas of his brain are understimulated, and these are the same regions that are well stimulated when we play video games.

In a neurological sense, play is the exact opposite of depression.

When the area of the brain responsible for motivation is not active enough, we do not expect any rewards and success. As a result, we stop believing in ourselves, become pessimistic and lose the desire to do at least something. Small stimulation of this area of the brain means that there is no active blood circulation in it. Thus, a prolonged state of depression or lack of motivation can lead to the fact that we lose the ability to learn. nine0003 JD Hancock/Flickr.com

The most common interpretation of the research findings is that depression can be treated with video games. Apparently, those players who are in such a clinical condition can self-medicate with games. Gamers often experience a sense of relief, relief from depression symptoms, and enjoyment.

But, of course, no one suggests treating depression with video games - this is a rather dangerous path. The player can distance themselves from their own problems or engage in suppression of unpleasant emotions.