Treatment options for anorexia

Anorexia nervosa - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

If your doctor suspects that you have anorexia nervosa, he or she will typically do several tests and exams to help pinpoint a diagnosis, rule out medical causes for the weight loss, and check for any related complications.

These exams and tests generally include:

- Physical exam. This may include measuring your height and weight; checking your vital signs, such as heart rate, blood pressure and temperature; checking your skin and nails for problems; listening to your heart and lungs; and examining your abdomen.

- Lab tests. These may include a complete blood count (CBC) and more-specialized blood tests to check electrolytes and protein as well as functioning of your liver, kidney and thyroid. A urinalysis also may be done.

- Psychological evaluation. A doctor or mental health professional will likely ask about your thoughts, feelings and eating habits.

You may also be asked to complete psychological self-assessment questionnaires.

- Other studies. X-rays may be taken to check your bone density, check for stress fractures or broken bones, or check for pneumonia or heart problems. Electrocardiograms may be done to look for heart irregularities.

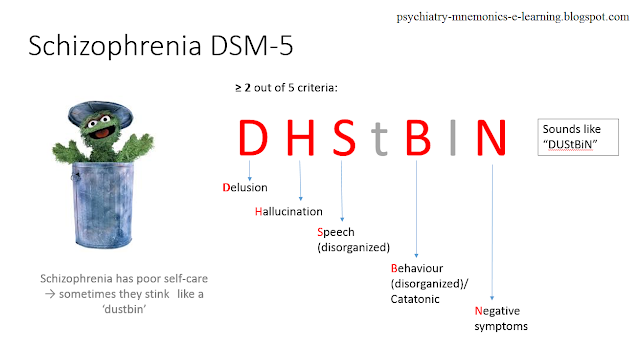

Your mental health professional also may use the diagnostic criteria for anorexia in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association.

More Information

- Bone density test

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

- Liver function tests

- Urinalysis

- X-ray

Treatment

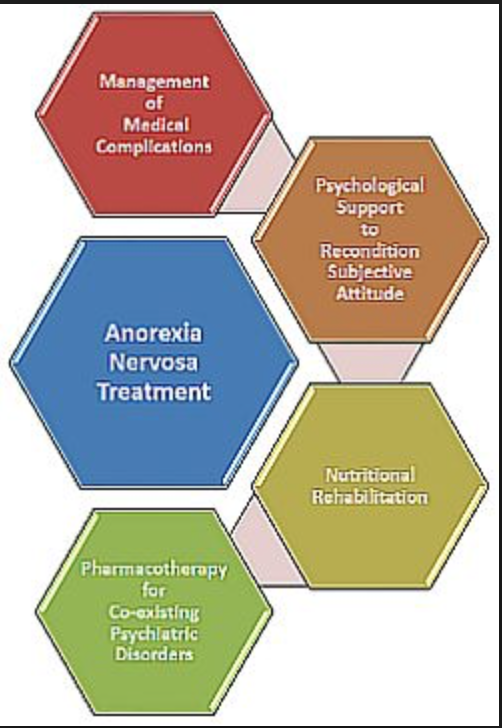

Treatment for anorexia is generally done using a team approach, which includes doctors, mental health professionals and dietitians, all with experience in eating disorders. Ongoing therapy and nutrition education are highly important to continued recovery.

Here's a look at what's commonly involved in treating people with anorexia.

Hospitalization and other programs

If your life is in immediate danger, you may need treatment in a hospital emergency room for such issues as a heart rhythm disturbance, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances or a psychiatric emergency. Hospitalization may be required for medical complications, severe psychiatric problems, severe malnutrition or continued refusal to eat.

Some clinics specialize in treating people with eating disorders. They may offer day programs or residential programs rather than full hospitalization. Specialized eating disorder programs may offer more-intensive treatment over longer periods of time.

Medical care

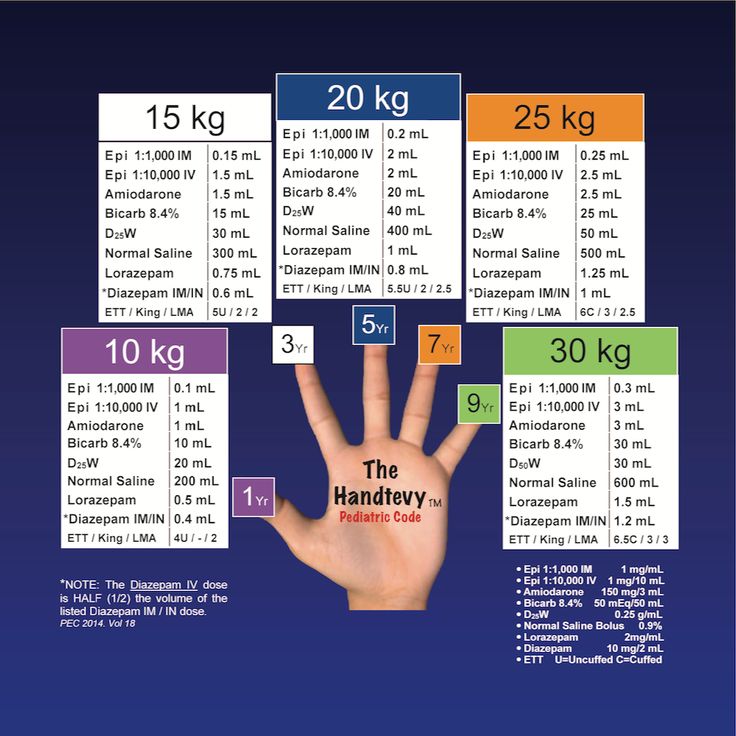

Because of the host of complications anorexia causes, you may need frequent monitoring of vital signs, hydration level and electrolytes, as well as related physical conditions. In severe cases, people with anorexia may initially require feeding through a tube that's placed in their nose and goes to the stomach (nasogastric tube).

Care is usually coordinated by a primary care doctor or a mental health professional, with other professionals involved.

Restoring a healthy weight

The first goal of treatment is getting back to a healthy weight. You can't recover from anorexia without returning to a healthy weight and learning proper nutrition. Those involved in this process may include:

- Your primary care doctor, who can provide medical care and supervise your calorie needs and weight gain

- A psychologist or other mental health professional, who can work with you to develop behavioral strategies to help you return to a healthy weight

- A dietitian, who can offer guidance getting back to regular patterns of eating, including providing specific meal plans and calorie requirements that help you meet your weight goals

- Your family, who will likely be involved in helping you maintain normal eating habits

Psychotherapy

These types of therapy may be beneficial for anorexia:

- Family-based therapy.

This is the only evidence-based treatment for teenagers with anorexia. Because the teenager with anorexia is unable to make good choices about eating and health while in the grips of this serious condition, this therapy mobilizes parents to help their child with re-feeding and weight restoration until the child can make good choices about health.

This is the only evidence-based treatment for teenagers with anorexia. Because the teenager with anorexia is unable to make good choices about eating and health while in the grips of this serious condition, this therapy mobilizes parents to help their child with re-feeding and weight restoration until the child can make good choices about health. - Individual therapy. For adults, cognitive behavioral therapy — specifically enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy — has been shown to help. The main goal is to normalize eating patterns and behaviors to support weight gain. The second goal is to help change distorted beliefs and thoughts that maintain restrictive eating.

Medications

No medications are approved to treat anorexia because none has been found to work very well. However, antidepressants or other psychiatric medications can help treat other mental health disorders you may also have, such as depression or anxiety.

Treatment challenges in anorexia

One of the biggest challenges in treating anorexia is that people may not want treatment. Barriers to treatment may include:

Barriers to treatment may include:

- Thinking you don't need treatment

- Fearing weight gain

- Not seeing anorexia as an illness but rather a lifestyle choice

People with anorexia can recover. However, they're at increased risk of relapse during periods of high stress or during triggering situations. Ongoing therapy or periodic appointments during times of stress may help you stay healthy.

More Information

- Acupuncture

- Family therapy

- Psychotherapy

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies testing new treatments, interventions and tests as a means to prevent, detect, treat or manage this condition.

Lifestyle and home remedies

When you have anorexia, it can be difficult to take care of yourself properly. In addition to professional treatment, follow these steps:

- Stick to your treatment plan.

Don't skip therapy sessions and try not to stray from meal plans, even if they make you uncomfortable.

Don't skip therapy sessions and try not to stray from meal plans, even if they make you uncomfortable. - Talk to your doctor about appropriate vitamin and mineral supplements. If you're not eating well, chances are your body isn't getting all of the nutrients it needs, such as Vitamin D or iron. However, getting most of your vitamins and minerals from food is typically recommended.

- Don't isolate yourself from caring family members and friends who want to see you get healthy. Understand that they have your best interests at heart.

- Resist urges to weigh yourself or check yourself in the mirror frequently. These may do nothing but fuel your drive to maintain unhealthy habits.

Alternative medicine

Dietary supplements and herbal products designed to suppress the appetite or aid in weight loss may be abused by people with anorexia. Weight-loss supplements or herbs can have serious side effects and dangerously interact with other medications. These products do not go through a rigorous review process and may have ingredients that are not posted on the bottle.

These products do not go through a rigorous review process and may have ingredients that are not posted on the bottle.

Keep in mind that natural doesn't always mean safe. If you use dietary supplements or herbs, discuss the potential risks with your doctor.

Anxiety-reducing approaches that complement anorexia treatment may increase the sense of well-being and promote relaxation. Examples of these approaches include massage, yoga and meditation.

Coping and support

You may find it difficult to cope with anorexia when you're hit with mixed messages by the media, culture, and perhaps your own family or friends. You may even have heard people joke that they wish they could have anorexia for a while so that they could lose weight.

Whether you have anorexia or your loved one has anorexia, ask your doctor or mental health professional for advice on coping strategies and emotional support. Learning effective coping strategies and getting the support you need from family and friends are vital to successful treatment.

Preparing for your appointment

Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment and know what to expect from your doctor or mental health professional.

You may want to ask a family member or friend to go with you. Someone who accompanies you may remember something that you missed or forgot. A family member may also be able to give your doctor a fuller picture of your home life.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you're experiencing, including any that may seem unrelated to the reason for the appointment. Try to recall when your symptoms began.

- Key personal information, including any major stresses or recent life changes.

- All medications, vitamins, herbal products, over-the-counter medications and other supplements that you're taking, and their dosages.

- Questions to ask your doctor so that you'll remember to cover everything you wanted to.

Some questions you might want to ask your doctor or mental health professional include:

- What kinds of tests do I need? Do these tests require any special preparation?

- Is this condition temporary or long lasting?

- What treatments are available, and which do you recommend?

- Is there a generic alternative to the medicine you're prescribing?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your doctor

Your doctor or mental health professional is likely to ask you a number of questions, including:

- How long have you been worried about your weight?

- Do you exercise? How often?

- What ways have you used to lose weight?

- Are you having any physical symptoms?

- Have you ever vomited because you were uncomfortably full?

- Have others expressed concern that you're too thin?

- Do you think about food often?

- Do you ever eat in secret?

- Have any of your family members ever had symptoms of an eating disorder or been diagnosed with an eating disorder?

Be ready to answer these questions to reserve time to go over any points you want to focus on.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

What It Is, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment

Overview

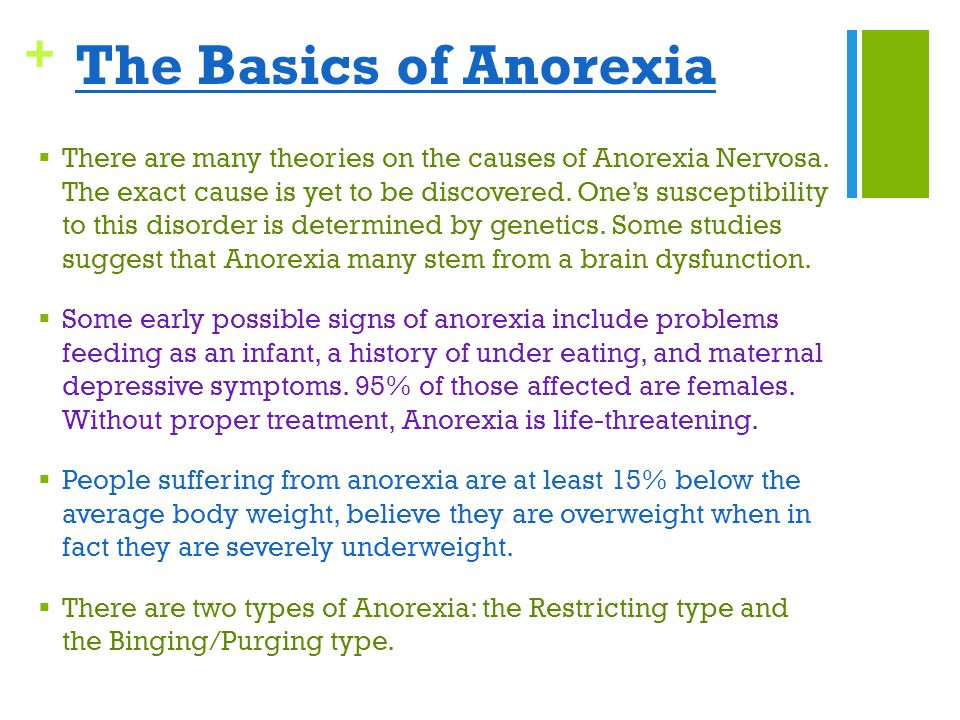

What is anorexia nervosa?

Anorexia, formally known as anorexia nervosa, is an eating disorder. People with anorexia limit the number of calories and the types of food they eat. Eventually, they lose weight or cannot maintain an appropriate body weight based on their height, age, stature and physical health. They may exercise compulsively and/or purge the food they eat through intentional vomiting and/or misuse of laxatives.

Individuals with anorexia also have a distorted self-image of their body and have an intense fear of gaining weight.

Anorexia is a serious condition that requires treatment. Extreme weight loss in people with anorexia can lead to malnutrition, dangerous health problems and even death.

Who does anorexia affect?

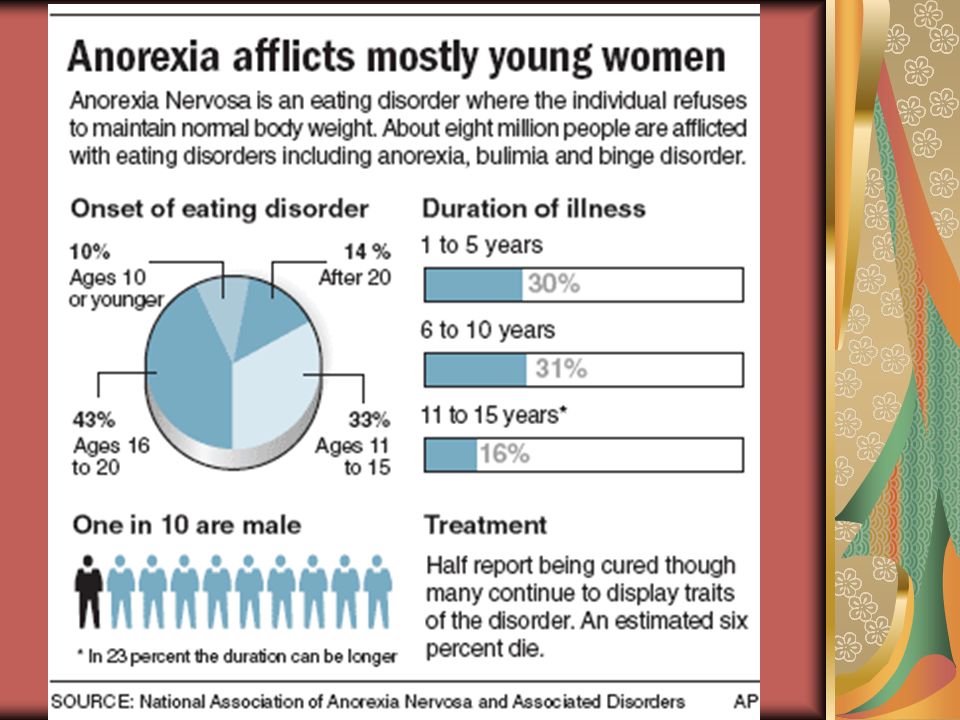

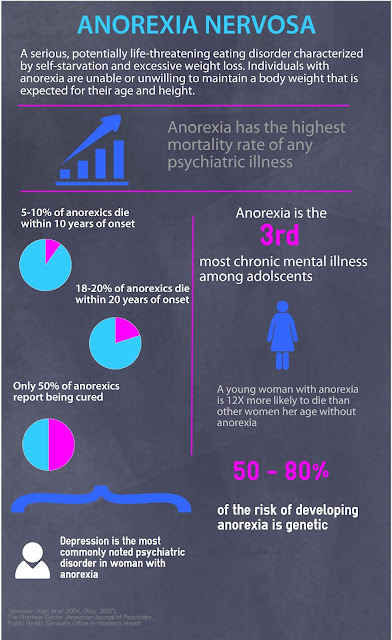

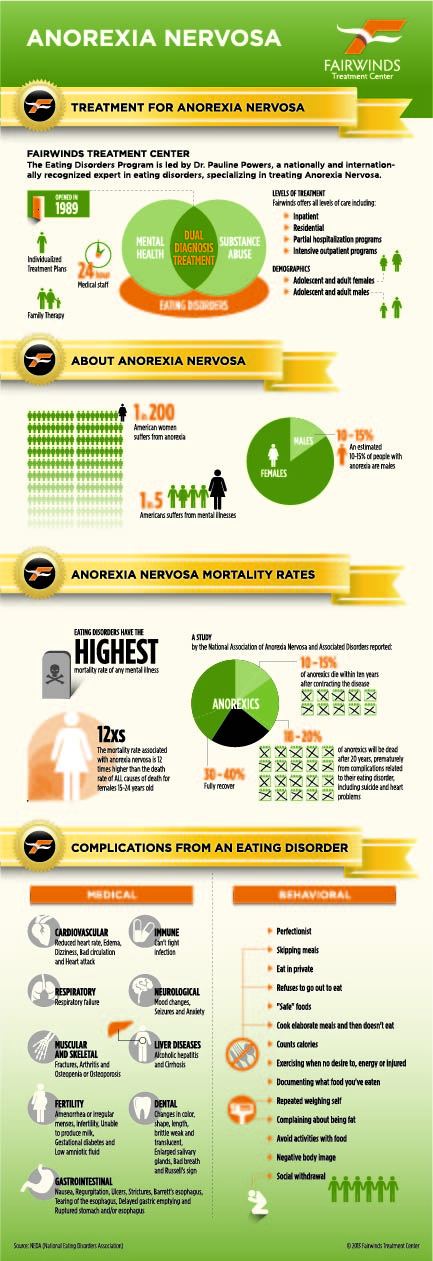

Anorexia can occur in people of any age, sex, gender, race, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation and economic status and individuals of all body weights, shapes and sizes. Anorexia most commonly affects adolescents and young adult women, although it also occurs in men and is increasing in numbers in children and older adults.

Anorexia most commonly affects adolescents and young adult women, although it also occurs in men and is increasing in numbers in children and older adults.

How common is anorexia?

Eating disorders affect at least 9% of the worldwide population, and anorexia affects approximately 1% to 2% of the population. It affects 0.3% of adolescents.

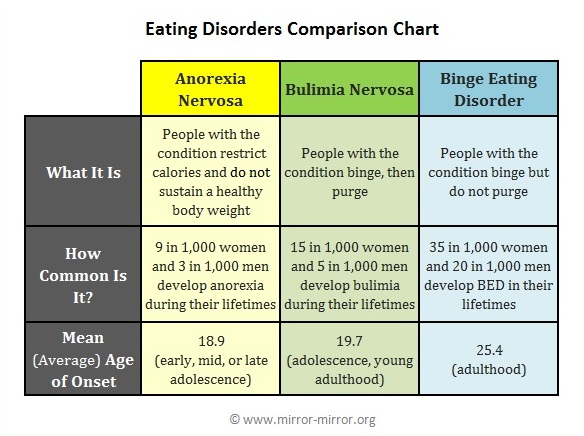

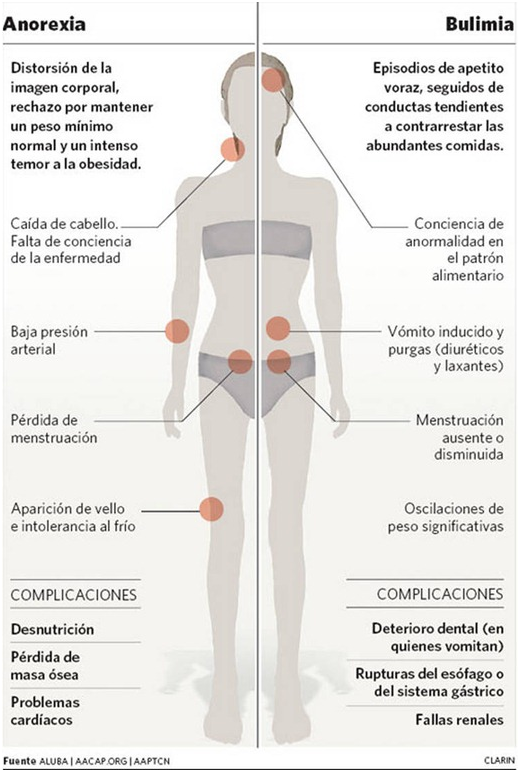

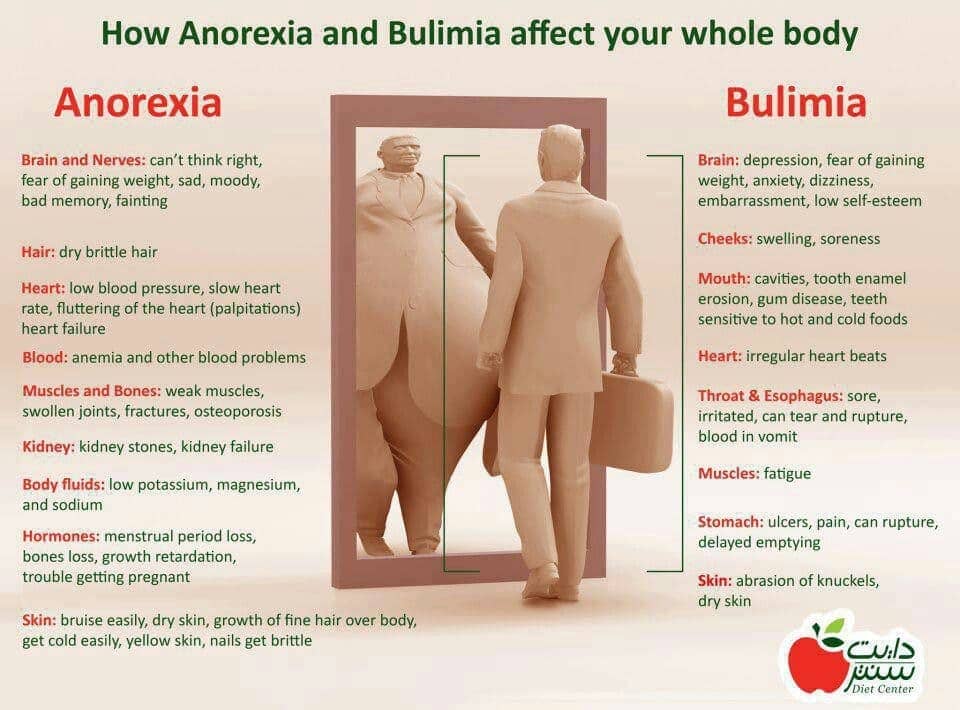

What is the difference between anorexia and bulimia?

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are both eating disorders. They can have similar symptoms, such as distorted body image and an intense fear of gaining weight. The difference is that they have different food-related behaviors.

People who have anorexia severely reduce their calorie intake and/or purge to lose weight. People who have bulimia eat an excessive amount of food in a short period of time (binge eating) followed by certain behaviors to prevent weight gain. Such behaviors include:

- Intentional (self-induced) vomiting.

- Misuse of medications such as laxatives or thyroid hormones.

- Fasting or exercising excessively.

People with bulimia usually maintain their weight at optimal or slightly above optimal levels whereas people with anorexia typically have a body mass index (BMI) that is below 18.45 kg/m2 (kilogram per square meter).

Symptoms and Causes

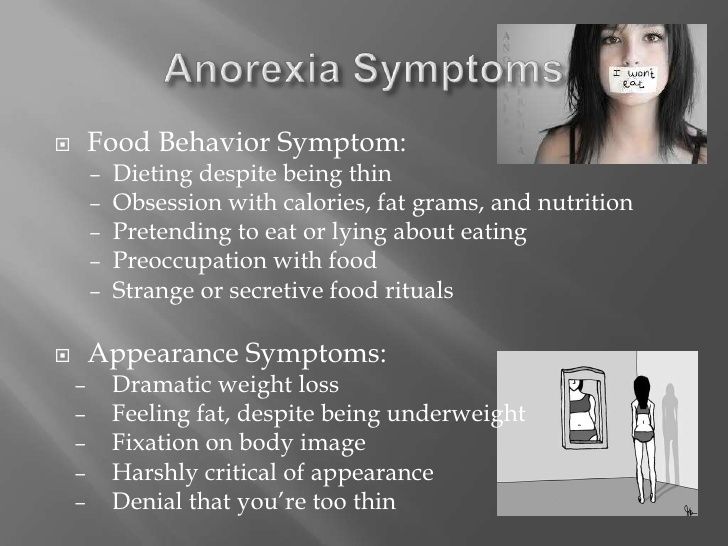

What are the signs and symptoms of anorexia?

You cannot tell if a person has anorexia just by their appearance because anorexia also involves mental and behavioral components — not just physical. A person does not need to be underweight to have anorexia. Larger-bodied individuals can also have anorexia. However, they may be less likely to be diagnosed due to cultural stigma against fat and obesity. In addition, someone can be underweight without having anorexia. Remember, anorexia also includes psychological and behavioral components as well as physical.

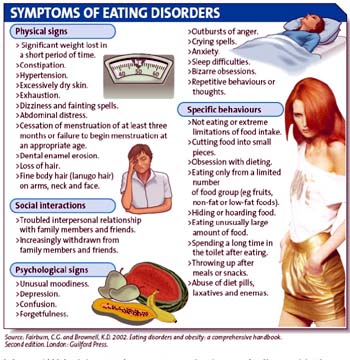

There are several emotional, behavioral and physical signs and symptoms of anorexia. If you or someone you know experiences the signs and symptoms of anorexia below, it’s important to seek help.

Emotional and mental signs of anorexia

Emotional and mental signs of anorexia include:

- Having an intense fear of gaining weight.

- Being unable to realistically assess your body weight and shape (having a distorted self-image).

- Having an obsessive interest in food, calories and dieting.

- Feeling overweight or “fat,” even if you’re underweight.

- Fear of certain foods or food groups.

- Being very self-critical.

- Denying the seriousness of your low body weight and/or food restriction.

- Feeling a strong desire to be in control.

- Feeling irritable and/or depressed.

- Experiencing thoughts of self-harm or suicide.

Behavioral signs of anorexia

Behavioral signs of anorexia include:

- Changes in eating habits or routines, such as eating foods in a certain order or rearranging foods on a plate.

- A sudden change in dietary preferences, such as eliminating certain food types or food groups.

- Making frequent comments about feeling “fat” or overweight despite weight loss.

- Purging through intentional vomiting and/or misusing laxatives or diuretics

- Going to the bathroom right after eating.

- Using diet pills or appetite suppressants.

- Compulsive and excessive exercising or extreme physical training.

- Continuing to diet even when your weight is low for your sex, height and stature.

- Making meals for others but not yourself.

- Wearing loose clothing and/or wearing layers to hide weight loss and stay warm.

- Withdrawing from friends and social events.

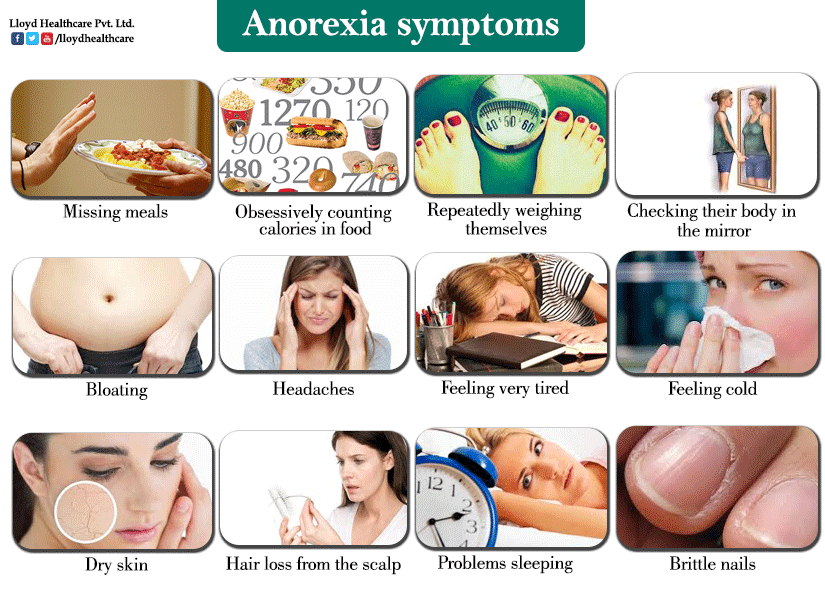

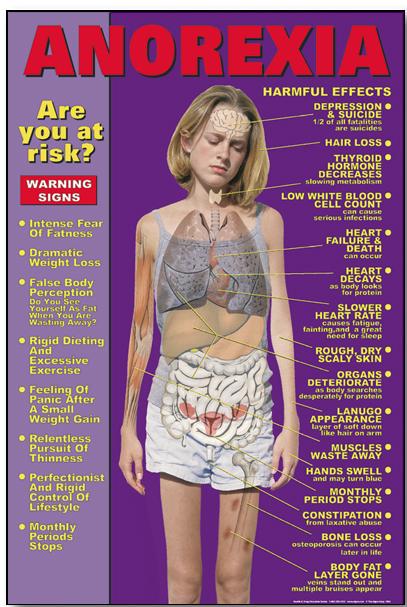

Physical signs and symptoms of anorexia

The most well-known physical sign of anorexia is low body weight for a person’s height, sex and stature. However, it’s important to remember that someone can have anorexia without being underweight. In addition to weight-related signs of anorexia, there are also physical symptoms that are actually side effects of starvation and malnutrition.

Physical signs of anorexia include:

- Significant weight loss over several weeks or months.

- Not maintaining an appropriate body weight based on your height, age, sex, stature and physical health.

- Unexplained change in growth curve or body mass index (BMI) in children and still growing adolescents.

Physical symptoms of anorexia that are side effects of starvation and malnutrition include:

- Dizziness and/or fainting.

- Feeling tired.

- Slow heartbeat (bradycardia) or irregular heartbeat (arrhythmia).

- Low blood pressure (hypotension).

- Poor concentration and focus.

- Feeling cold all the time.

- Absent periods (amenorrhea) or irregular menstrual periods.

- Shortness of breath.

- Bloating and/or abdominal pain.

- Muscle weakness and loss of muscle mass.

- Dry skin, brittle nails and/or thinning hair.

- Poor wound healing and frequent illness.

- Bluish or purple coloring of the hands and feet.

What causes anorexia?

Anorexia and all eating disorders are complex conditions. For this reason, the exact cause of anorexia is unknown, but research suggests that a combination of certain genetic factors, psychological traits and environmental factors, especially sociocultural factors, might be responsible.

Factors that may be involved in developing anorexia include:

- Genetics: Research suggests that approximately 50% to 80% of the risk of developing an eating disorder is genetic. People with first-degree relatives (siblings or parents) with an eating disorder are 10 times more likely to develop an eating disorder, which suggests a genetic link. Changes in brain chemistry may also play a role, particularly changes to the brain reward system and neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, which can affect appetite, mood and impulse control.

- Trauma: Many experts believe that eating disorders, including anorexia, are caused by people attempting to cope with overwhelming feelings and painful emotions by controlling food.

Physical abuse or sexual assault, for example, can contribute to some people developing an eating disorder.

- Environment and culture: Cultures that idealize a particular body type — usually “thin” bodies — can place unnecessary pressure on people to achieve unrealistic body standards. Popular culture and images in media and advertising often link thinness to popularity, success, beauty and happiness. This may contribute to someone developing anorexia.

- Peer pressure: Particularly for children and adolescents, peer pressure can be a very powerful force. Experiencing teasing, bullying or ridiculing because of appearance or weight can contribute to the development of anorexia.

- Emotional health: Perfectionism, impulsive behavior and difficult relationships can all play a role in lowering a person’s self-esteem and perceived self-worth. This can make them vulnerable to developing anorexia.

It’s important to note that there’s no single path to an eating disorder or anorexia. For many people, irregular eating behaviors (also called “disordered eating”) represent an inappropriate coping strategy that becomes permanent over time. This pathway to disordered eating is true for some, but not all, who develop anorexia.

For many people, irregular eating behaviors (also called “disordered eating”) represent an inappropriate coping strategy that becomes permanent over time. This pathway to disordered eating is true for some, but not all, who develop anorexia.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is anorexia diagnosed?

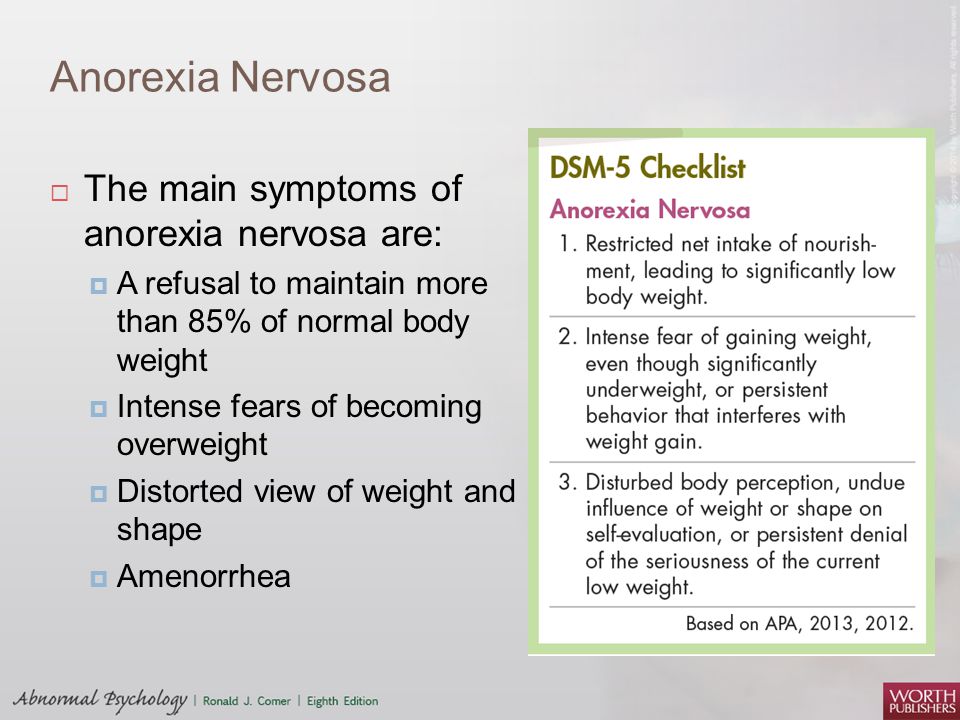

A healthcare provider can diagnose a person with anorexia based on the criteria for anorexia nervosa listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association. The three criteria for anorexia nervosa under the DSM-5 include:

- Restriction of calorie consumption leading to weight loss or a failure to gain weight resulting in a significantly low body weight based on that person’s age, sex, height and stage of growth.

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming “fat.”

- Having a distorted view of themselves and their condition. In other words, the individual is unable to realistically assess their body weight and shape believes their appearance has a strong influence on their self-worth and denies the medical seriousness of their current low body weight and/or food restriction.

Even if all of the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia aren’t met, a person can still have a serious eating disorder. DSM-5 criteria classifies the severity of anorexia according to body mass index (BMI). Individuals who meet the criteria for anorexia but who aren’t underweight despite significant weight loss have what’s known as atypical anorexia.

Diagnostic guidelines in the DSM-5 also allow healthcare providers to determine if a person is in partial remission (recovery) or full remission as well as to specify the current severity of the condition based on body mass index (BMI).

If signs and symptoms of anorexia are present, a healthcare provider will begin an evaluation by performing a complete medical history and physical examination. The provider or a mental health professional will likely ask questions about the following topics:

- Dietary history (attitudes about food, dietary restriction).

- Exercise history.

- Psychological history.

- Body image (this includes behaviors such as how often you weigh yourself).

- Bingeing and purging frequency and elimination habits (use of diet pills, laxatives and supplements).

- Family history of eating disorders.

- Menstrual status (if your periods are regular or irregular).

- Medication history.

- Prior treatment.

It’s important to remember that a person with anorexia or any eating disorder will have the best recovery outcome if they receive an early diagnosis. If you or someone you know is experiencing signs and symptoms of anorexia, be sure to talk to a healthcare provider as soon as possible.

What tests are used to diagnose or assess anorexia?

Although there are no laboratory tests to specifically diagnose anorexia, a healthcare provider may use various diagnostic tests, such as blood tests, to rule out any medical conditions that could cause weight loss and to evaluate the physical damage weight loss and starvation may have caused.

Tests to rule out weight-loss causing illness or to assess anorexia side effects may include:

- Complete blood count to assess overall health.

- An electrolyte blood panel to check for dehydration and your blood’s acid-base balance.

- Albumin blood test to check for liver health and nutrient deficiency.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG) to check heart health.

- Urinalysis to check for a wide range of conditions.

- Bone density test to check for weak bones (osteoporosis).

- Kidney function tests.

- Liver function tests.

- Thyroid function tests.

- Vitamin D levels.

- A pregnancy test in people assigned female at birth who are of childbearing age.

- Hormone tests if evidence of menstrual problems in people assigned female at birth (to rule out other causes) and measuring testosterone in people assigned male at birth.

Management and Treatment

How is anorexia treated?

The biggest challenge in treating anorexia is helping the person recognize and accept that they have an illness. Many people with anorexia deny that they have an eating disorder. They often seek medical treatment only when their condition is serious or life-threatening. This is why it’s important to diagnose and treat anorexia in its beginning stages.

They often seek medical treatment only when their condition is serious or life-threatening. This is why it’s important to diagnose and treat anorexia in its beginning stages.

The goals of treatment for anorexia include:

- Stabilizing weight loss.

- Beginning nutrition rehabilitation to restore weight.

- Eliminating binge eating and/or purging behaviors and other problematic eating patterns.

- Treating psychological issues such as low self-esteem and distorted thinking patterns.

- Developing long-term behavioral changes.

People with eating disorders, including anorexia, often have additional mental health conditions, including:

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorders.

- Borderline personality disorder.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Substance use disorders.

These conditions can further complicate anorexia, so if an individual has one or more of these conditions, their healthcare team will likely recommend treatment for the condition(s) as well.

Treatment options will vary depending on the individual’s needs. A person may receive treatment through residential care (outpatient care) or hospitalization depending on their current medical and mental health state. Treatment for anorexia most often involves a combination of the following strategies:

- Psychotherapy.

- Medication.

- Nutrition counseling.

- Group and/or family therapy.

- Hospitalization.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is a type of individual counseling that focuses on changing the thinking (cognitive therapy) and behavior (behavioral therapy) of a person with an eating disorder. Treatment includes practical techniques for developing healthy attitudes toward food and weight, as well as approaches for changing the way the person responds to difficult situations. There are several types of psychotherapy, including:

- Acceptance and commitment therapy: This therapy’s goal is to develop motivation to change actions rather than your thoughts and feelings.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): This therapy’s goal is to address distorted views and attitudes about weight, shape and appearance and to practice behavioral modification (if “X” happens, I can do “Y” instead of “Z”).

- Cognitive remediation therapy: This therapy uses reflection and guided supervision to develop the capability of focusing on more than one thing at a time.

- Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT): This therapy helps you not just develop new skills to handle negative triggers but also helps you develop insight to recognize triggers or situations where a non-useful behavior might occur. Specific skills include building mindfulness, improving relationships through interpersonal effectiveness, managing emotions and tolerating stress.

- Family-based therapy (also called the Maudsley Method): This therapy involves family-based refeeding, which means putting the parents and family in charge of getting the appropriate nutritional intake consumed by the person with anorexia.

It’s the most evidence-based method to physiologically restore health to an individual with anorexia who is under 18 years of age.

It’s the most evidence-based method to physiologically restore health to an individual with anorexia who is under 18 years of age. - Interpersonal psychotherapy: This therapy is aimed at resolving an interpersonal problem area. Improving relationships and communications and resolving identified problems may reduce eating disorder symptoms.

- Psychodynamic psychotherapy: This therapy involves looking at the root causes of anorexia as the key to recovery.

Medication

Some healthcare providers may prescribe medication to help manage anxiety and depression that are often associated with anorexia. The antipsychotic medication olanzapine (Zyprexa®) may be helpful for weight gain. Sometimes, providers prescribe medications to help with period regulation.

Nutrition counseling

Nutrition counseling is a strategy to help treat anorexia that involves the following:

- Teaching a healthy approach to food and weight.

- Helping restore normal eating patterns.

- Teaching the importance of nutrition and a balanced diet.

- Restoring a healthy relationship with food and eating.

Group and/or family therapy

Family support is very important to anorexia treatment success. Family members must understand the eating disorder and recognize its signs and symptoms.

People with eating disorders might also benefit from group therapy, where they can find support and openly discuss their feelings and concerns with others who share common experiences.

Hospitalization

Hospitalization might be needed to treat severe weight loss that has resulted in malnutrition and other serious mental or physical health complications, such as heart disorders, serious depression and suicidal thoughts or behaviors.

The most serious complication of treating anorexia is a condition called refeeding syndrome. This life-threatening condition can occur when a seriously malnourished person begins to receive nutrition again. Basically, their body cannot properly restart the metabolism process.

Basically, their body cannot properly restart the metabolism process.

People experiencing refeeding syndrome can develop the following conditions:

- Whole-body swelling (edema).

- Heart failure and/or lung failure.

- Gastrointestinal problems.

- Extensive muscle weakness.

- Delirium.

- Death.

Since refeeding syndrome can have serious and life-threatening side effects, it’s essential for people with anorexia to receive medical treatment and/or guidance.

People who have one or more of the following risk factors for developing refeeding syndrome may need to be treated in a hospital:

- Are severely malnourished (less than 70% median BMI in adolescents; a BMI of less than 15 in adults).

- Have had little or no calorie intake for more than 10 days.

- Have a history of refeeding syndrome.

- Have lost a lot of weight in a very short period of time (10% to 15% of total body mass within three to six months).

- Drink significant amounts of alcohol.

- Have a history of misusing laxatives, diet pills, diuretics, or insulin (if they have diabetes).

- Have abnormal electrolyte levels before starting refeeding.

How long does it take to recover from anorexia?

Every person’s anorexia recovery journey is different. The important thing to remember is that it is possible to recover from anorexia. Treatment for anorexia often involves many components, such as psychological therapy, nutritional counseling and addressing the cause of the person’s anorexia, if possible, and each of these components can take different amounts of time.

No matter where you or a loved one are in their journey of recovery, it’s essential to continue working toward recovery.

Prevention

What are the risk factors for developing anorexia?

Anorexia can affect anyone, no matter their gender, age or race. However, certain factors put some people at greater risk for developing anorexia, including:

- Age: Eating disorders, including anorexia, are more common in adolescents and young adults, but young children and older adults can still develop anorexia.

- Gender: Women and girls are more likely to be diagnosed with anorexia. However, it’s important to know that men and boys can have anorexia and may be under-diagnosed due to differences in seeking treatment.

- Family history: Having a parent or sibling (first-degree relative) with an eating disorder increases your risk of developing an eating disorder, such as anorexia.

- Dieting: Dieting taken too far can develop into anorexia.

- Changes and trauma: Big changes in your life, such as going to college, starting a new job or going through a divorce, and/or trauma, such as sexual assault or physical abuse, may trigger the development of anorexia.

- Certain careers and sports: Eating disorders are especially common amongst models, gymnasts, runners, wrestlers and dancers.

Can anorexia be prevented?

Although it might not be possible to prevent all cases of anorexia, it’s helpful to start treatment as soon as someone begins to have symptoms.

In addition, teaching and encouraging healthy eating habits and realistic attitudes about food and body image also might help prevent the development or worsening of eating disorders. If your child or family member decides to become vegetarian or vegan, for instance, it’s worth seeing a dietitian versed in eating disorders and touching base with your pediatrician or healthcare provider to make sure that this change occurs without a loss in nutrients.

Outlook / Prognosis

What is the outlook (prognosis) for people with anorexia?

The prognosis for anorexia varies depending on certain factors, including:

- How long the person has had anorexia.

- The severity of the condition.

- The type of treatment and adherence to treatment.

Anorexia, like other eating disorders, gets worse the longer it’s left untreated. The sooner the disorder is diagnosed and treated, the better the outcome. However, people with anorexia often will not admit they have a problem and might resist treatment or refuse to follow the treatment plan.

Anorexia is a serious and potentially life-threatening eating disorder if it’s left untreated. Eating disorders, including anorexia, are among the deadliest mental health conditions, second only to opioid addiction. Individuals with anorexia are 5 times more likely to die prematurely and 18 times more likely to die by suicide.

The good news is that anorexia can be treated, and someone with anorexia can return to a healthy weight and healthy eating patterns. Unfortunately, the risk of relapse is high, so recovery from anorexia usually requires long-term treatment as well as a strong commitment by the individual. Support of family members and friends can help ensure that the person receives and adheres to their needed treatment.

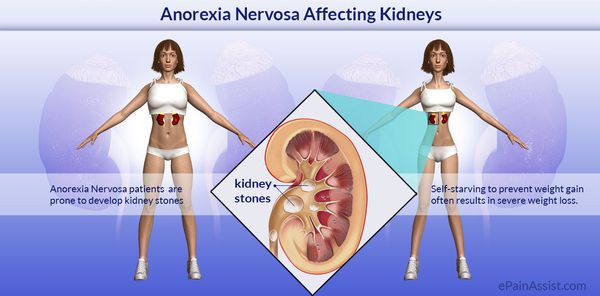

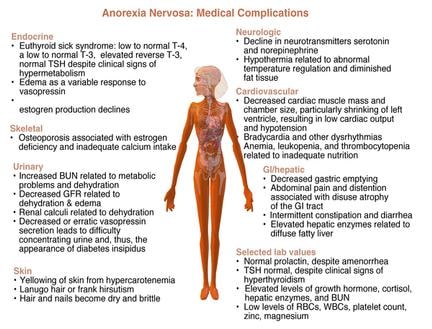

What are the complications of anorexia?

The medical complications and health risks of malnutrition and starvation, which are common in people who have anorexia, can affect nearly every organ in your body. In severe cases, vital organs such as your brain, heart and kidneys can sustain damage. This damage may be irreversible even after a person has recovered from anorexia.

This damage may be irreversible even after a person has recovered from anorexia.

Severe medical complications that can happen from untreated anorexia include:

- Irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia).

- Loss of bone mass (osteoporosis) and tooth enamel erosion.

- Kidney and liver damage.

- Fatty liver disease (steatosis).

- Seizures caused by extremely low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).

- Rhabdomyolysis (rapid breakdown of skeletal muscle) due to loss of water and electrolyte/acid-base imbalances.

- Delayed puberty and physical growth.

- Infertility and menstrual problems.

- Insomnia.

- Anemia.

- Ventricular arrhythmia, a heart rhythm disorder.

- Mitral valve prolapse (caused by loss of heart muscle mass).

- Cardiac arrest.

- Death.

In addition to physical complications, people with anorexia also commonly have other mental health conditions, including:

- Depression, anxiety and other mood disorders.

- Personality disorders.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorders.

- Alcohol use disorder and substance misuse.

If these mental health conditions are left untreated, they could lead to self-injury, suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts.

If you’re having suicidal thoughts, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Someone will be available to talk with you 24/7.

Living With

How do I take care of myself if I have anorexia?

It can be uncomfortable and scary, but it’s important to tell a loved one and/or your healthcare provider if you have anorexia.

If you have already been diagnosed with anorexia, there are some things you can do to manage your condition and stay committed to recovery, including:

- Get enough sleep.

- Don’t abuse alcohol or drugs.

- If you take prescribed medication, be sure to take it regularly and do not miss doses.

- If you are participating in talk therapy to treat your anorexia, be sure to see your therapist regularly.

- Reach out to family and friends for support.

- Consider joining a support group for people who have anorexia.

- See your healthcare provider regularly.

How can I care for a loved one who has anorexia?

There are multiple things you can do to help and support someone with anorexia, including:

- Learn about anorexia: Educate yourself about anorexia to better understand what they are going through. Don’t assume you know what they are experiencing.

- Be empathetic: Don’t downplay or dismiss their feelings and experiences. Let them know that you are there to listen and support them. Try to put yourself in their shoes.

- Encourage them to seek help and/or treatment: While having an understanding and supportive friend or family member is helpful to a person with anorexia, anorexia is a medical condition. Because of this, people with anorexia need treatment such as therapy and nutritional counseling to manage their condition.

Encourage them to talk to their healthcare provider if they are experiencing the signs and symptoms of anorexia.

Encourage them to talk to their healthcare provider if they are experiencing the signs and symptoms of anorexia. - Be patient: It can take a while for someone with anorexia to get better once they’ve started treatment. Know that it is a long and complex process and that their symptoms and behaviors will eventually improve.

When should I see my healthcare provider?

If you or someone you know is experiencing signs and symptoms of anorexia, be sure to talk to a healthcare provider as soon as possible.

When should a person with anorexia go to the emergency room?

Someone with anorexia should go to the emergency room (ER) if they’re experiencing any of the following physical symptoms:

- Unusually low blood pressure.

- Decreased heart rate or irregular heartbeat.

- Chest pain.

- Seizures (due to extremely low blood sugar levels).

If you’re having thoughts of harming yourself, get to the nearest hospital as soon as possible or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. Someone will be available to talk with you 24/7.

Someone will be available to talk with you 24/7.

If you recognize suicidal behaviors in someone with anorexia, get them care as soon as possible.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Anorexia is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition. The good news is that recovery is definitely possible. If you or someone you know is experiencing signs and symptoms of anorexia, it’s essential to seek help and care as soon as possible. It’s never too late to seek treatment, but getting help early improves the chance of a lasting recovery.

Psychiatric treatment of anorexia - description and classification of the disease

Anorexia is a mental disorder that manifests itself in a violation of healthy eating behavior. A person with a similar disease has distorted ideas about his body, there is a syndrome of dysmorphomania, there are negative emotions in relation to food. He clearly controls the process of eating or even completely refuses it. It is impossible to cope with anorexia without the help of a psychotherapist.

The complexity of diagnosis, treatment lies in the fact that the sick person carefully hides the symptoms from others. Many patients, only after long-term work with a psychiatrist, admit that they need help. Patients with RPP do not realize the severity of their condition, even when the body mass index reaches a critical point and becomes life-threatening.

Article content:

- Disease description

- Classification of anorexia

- Varieties according to clinical signs

- Disease stages

- Methods of treatment

Description of the disease

Anorexia begins with a reduction in portions, fad diets or the exclusion of fatty, high-calorie foods. Over time, nutritional rules may appear. At first, talk about diets, exercise, excess weight often pops up, but over time they subside. Further, joint dinners and holidays are avoided, where it becomes more and more difficult to hide the refusal to eat. Over time, the weight decreases to life-threatening levels, which complicates the treatment.

Over time, the weight decreases to life-threatening levels, which complicates the treatment.

Anorexia nervosa is accompanied by the following symptoms:

- panic fear of gaining weight;

- fixation on maintaining a minimum weight;

- disruption of normal sleep patterns;

- general lethargy, weakness;

- punishing oneself with exhausting physical activity in case of increasing portions or eating “forbidden” foods;

- change in eating habits - cutting food into pieces, eating only liquid dishes;

If we are talking about a teenager, then there is a sudden interest in fashion, diets. The child may begin to wear baggy clothes to hide his body, refuse favorite treats, avoid lunches, dinners with adults.

Classification

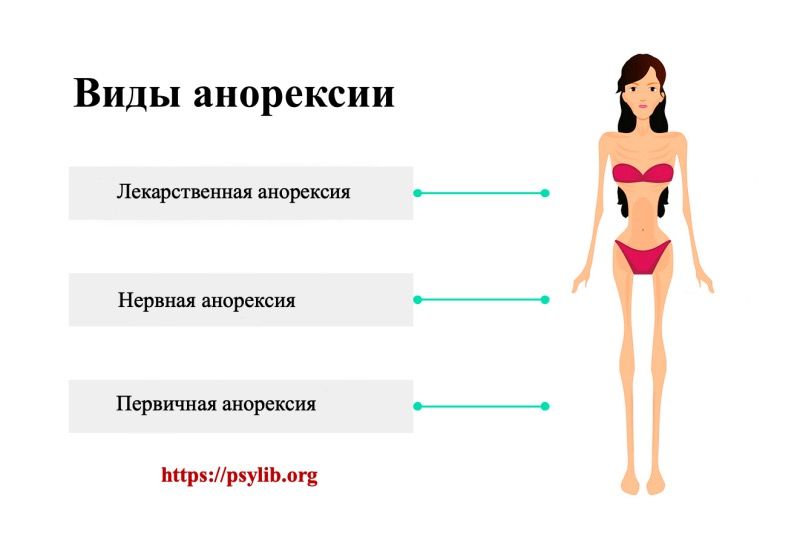

Mental anorexia can be of the following types, depending on the causes:

- primary - is a consequence of neurology, malignant tumors or a violation of hormone production;

- medicinal - symptoms appear on the background of taking drugs;

- mental - develops due to schizophrenia or other serious illness, treated by a psychiatrist;

- nervous - a common form of the disorder in which eating disorders occur without objective reasons.

Severe weight loss, refusal to eat suggest examination. Based on all the data obtained, interviews, the patient is given an accurate diagnosis before treatment.

Varieties of anorexia according to clinical signs

When classifying nervous disorders, psychiatrists take into account clinical manifestations. According to this criterion, three types of anorexia are distinguished. First, an eating disorder with monothematic dysmorphophobia. In this case, the patient really wants to lose weight, uses any means for this: diets, sports, eating only low-calorie foods, abuse of laxatives, diuretics, appetite suppressants.

Secondly, there is a disturbed eating behavior, when periods of anorexia are replaced by bulimia. For treatment to a psychiatrist, such patients do not get soon, because due to bouts of overeating, critical weight loss is not observed for a long time.

Thirdly, the disease can be combined with bulimia, vomitomania. After the overeating stage, the person induces vomiting as a weight correction measure. This greatly depletes the body.

After the overeating stage, the person induces vomiting as a weight correction measure. This greatly depletes the body.

Disease stages

There are three stages of anorexia:

- Pre-anorexic or dysmorphophobic. At this stage, the symptoms are expressed by thoughts of completeness, rejection of one's body. There is shame in front of others for their appearance.

- Anorexic or dysmorphic. At this stage, hunger strikes are practiced. Medications may be taken to reduce appetite or increase metabolism. Ordinary food is sometimes replaced with inedible items to fill the stomach.

- Cachectic. This is a severe anorexia, which carries a direct threat to life. Appetite is completely absent, problems with internal organs appear, etc., therefore, an immediate appeal to a psychiatrist is required.

Methods of treatment

Treatment of anorexia should be carried out under the supervision of doctors, it is impossible to cope with the disorder on your own.

Managing anorexia requires a holistic approach. Diagnostics of the body is carried out to exclude pathologies. After the diagnosis is made, it is necessary to normalize the patient's weight.

The applied methods of treatment in CIRP allow for psychotherapy, restoration of normal weight at the same time.

Medical care for patients with anorexia

Hospitalization and drug treatment are required if weight loss is more than 50% of normal body weight, the patient refuses to eat, the work of internal organs is disrupted. Depending on the symptoms, medicines are selected for each patient. With anorexia, drugs are used to combat vomiting, dehydration, as well as to improve fat and protein metabolism.

To cope with the disorder and normalize the emotional background, antidepressants, tranquilizers and other drugs prescribed by a psychiatrist are used.

Psychiatric help

Anorexia needs help. His participation is necessary for relatives of patients, building healthy family relationships, and forming self-esteem. Only a psychiatrist can prescribe medication. He decides on the appointment of drug therapy. Even at the initial stage of treatment, it is important to consult a psychiatrist. There is always a risk that another disease is hiding behind the struggle with weight. The psychiatrist conducts diagnostics to exclude such a possibility.

Only a psychiatrist can prescribe medication. He decides on the appointment of drug therapy. Even at the initial stage of treatment, it is important to consult a psychiatrist. There is always a risk that another disease is hiding behind the struggle with weight. The psychiatrist conducts diagnostics to exclude such a possibility.

Treatment of psychic anorexia

The help of a psychologist in the treatment of anorexia is necessary, because patients have not only low weight, but also problems with self-esteem, thoughts of inferiority. The doctor will help to work out fears, get rid of the imposed standards of beauty, learn to love and accept yourself, change your behavior, attitude towards the disease.

Depending on the cause of the disorder, a treatment option is selected. There are schools and directions that show the effectiveness of dealing with the problem. The patient will:

- individual treatment – he communicates face-to-face with the doctor;

- group classes are a great way to see how others are struggling with the disorder, to get support, understanding;

- multifamily psychotherapy.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychiatrist help with anorexia is to use cognitive behavioral therapy

It allows you to work out two factors:

- restoration of conditioned reflexes - the patient must learn to eat when he feels hungry;

- correction of erroneous ideas about one's weight and appearance - a psychiatrist works with settings that provoke passion for diets, hunger strikes.

In the process of therapy, the patient gets rid of the fear of fullness, obsessive thoughts, learns not to associate success, happiness with the standards of beauty.

Body-oriented method

This approach to treatment allows the psychotherapist to teach how to avoid potentially "dangerous" situations for the patient: to overcome the fear of having dinner together, not to strive for social isolation.

In recent years, psychiatrists have been actively using a body-oriented method of treatment aimed at accepting oneself.

Clamps in the body, habits speak of a person’s fears, self-doubt.

The “mirror” exercise is also considered effective. The patient, along with the psychiatrist, is in a room with mirrors. He examines, studies his body, talks about bodily, emotional sensations. All impressions are discussed and worked out with a specialist. The approach helps the patient to accept himself as he is. Therapy teaches you to find beauty in yourself and others, regardless of physical form, conformity to standards or norms.

Art therapy

Creative sessions with a psychotherapist are very useful for treating patients with ED. This approach allows:

- the doctor to understand the internal state of the patient, because not always a person can explain his condition with the help of words;

- prepare operational data for the appointment of further therapy;

- release the patient from blocked emotions, feelings - through creativity, it is easiest to open anger, resentment;

- to look at the patient's inner world from the outside.

Art therapy is useful if the patient refuses direct contact with a psychiatrist, rejects help. Veiled tests make it possible to assess the state of the psyche, to find an approach to the patient.

Recommendations

If anorexia nervosa is diagnosed, psychotherapists advise:

- to be treated in a hospital, if possible;

- involve the family - it is important to tell relatives how to properly provide support, teach them not to devalue the problems of another person;

- do not be afraid of antidepressants, drugs - they simplify and speed up recovery;

- do not give up psychotherapy immediately after normalization of weight - working on mental health is a long process.

Being a psychiatric patient is not scary. This doctor knows everything about the work of the psyche, will help you choose the right tools to deal with eating disorders. To learn more about eating disorders and start treatment, make an appointment at the Center for the Study of Eating Disorders in Moscow. You can apply by phone +7(499) 703-20-51 or through the form on the site.

You can apply by phone +7(499) 703-20-51 or through the form on the site.

Author: Korshunova Anna Aleksandrovna

Head of the Center for the Study of Eating Disorders,

psychiatrist, psychotherapist.

FGBNU NTSPZ. ‹‹Dysmorphomania in adolescence and youth ››

Treatment of patients with nervous (mental) anorexia also presents difficulties, because they are extremely resistant to any type of therapy. The methods of treatment of mental anorexia described in the world literature include insulin shock therapy in combination with antidepressants, loading doses of antipsychotics, ECT, hormone therapy, psychoanalysis, as well as the so-called behavioral therapy and even lobotomy.

Patients with anorexia nervosa can be treated on an outpatient and inpatient basis. However, most researchers believe that for the successful treatment of these patients, especially those with severe physical exhaustion, they must be hospitalized. Stationing pursues the goal of "separating the patient from the previous pathogenic situation" and, above all, "withdrawal from the family."

Stationing pursues the goal of "separating the patient from the previous pathogenic situation" and, above all, "withdrawal from the family."

Inpatient treatment, as a rule, was carried out by us in cases of severe anorexia, when patients were hospitalized for health reasons. Outpatient treatment was possible only when secondary somatoendocrine disorders did not reach the degree of severe cachexia and did not threaten the lives of patients.

First of all, let us dwell on the features of treatment in a hospital setting.

Schematically, the treatment program can be divided into two stages: 1) the stage of non-specific treatment aimed at improving the somatic condition; 2) the stage of specific treatment - the treatment of the underlying disease in accordance with its nosological affiliation. Nonspecific treatment was the same for all patients.

The goal of the first stage of treatment is to stop weight loss, strengthen the somatic condition and prepare patients for subsequent specific treatment.

In the first days of patients' stay in the clinic, the greatest attention should be paid to the state of the cardiovascular system, since patients with anorexia had dystrophic changes in the myocardium and severe hypotension. Often, hypotension (especially with a sharp transition from a horizontal to a vertical position) led to the development of collaptoid states with possible skull injuries (we observed such a case). Cardiac and vascular drugs were given to patients daily along with the introduction of a sufficient amount of fluids (40% glucose solution intravenously, 5% glucose solution and Ringer's solution subcutaneously) and vitamins (especially from groups A, B, C).

From the very first days, patients should be prescribed fractional, in small portions, nutrition, taking into account the state of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and pancreas. Only liquid food should be given 6 times a day.

The greatest difficulties arise, as a rule, during the first feedings of patients, when it is necessary to follow literally every spoonful of food, making sure that the patient swallows it. Feeding of such patients should be carried out by the attending physician or specially instructed personnel familiar with the peculiarities of the "eating behavior" of patients with anorexia nervosa. After each meal, patients should be on strict bed rest for 2 hours under the supervision of a nurse. Given the constant desire of patients for physical hyperactivity, in the first days after hospitalization, they need absolute bed rest. 24-hour supervision helps to prevent attempts to induce vomiting at night.

Feeding of such patients should be carried out by the attending physician or specially instructed personnel familiar with the peculiarities of the "eating behavior" of patients with anorexia nervosa. After each meal, patients should be on strict bed rest for 2 hours under the supervision of a nurse. Given the constant desire of patients for physical hyperactivity, in the first days after hospitalization, they need absolute bed rest. 24-hour supervision helps to prevent attempts to induce vomiting at night.

It should be said that patients almost always respond to such measures with hostility and a pronounced negative attitude towards the staff. To relieve internal stress and negativism in patients, sedatives should be prescribed (in particular, Elenium - 10 mg at night) or antipsychotics with a mild spectrum of action in small doses (frenolon 5-10 mg per day). In addition, these drugs are known to be certain appetite stimulants.

Given one of the basic rules for the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa, which is isolation from parents, visits to patients by parents and other relatives should be sharply limited (up to 1 time in 7-10 days). Often visits with relatives were used as a psychotherapeutic tool to encourage the correct "eating behavior" of patients. It is also advisable to warn patients at the time of hospitalization about the need for an increase in body weight of at least 10 kg.

Often visits with relatives were used as a psychotherapeutic tool to encourage the correct "eating behavior" of patients. It is also advisable to warn patients at the time of hospitalization about the need for an increase in body weight of at least 10 kg.

Non-specific treatment, which was based on the achievement of normalization of body weight, should last 1-3 weeks. During this period, you can achieve an increase in body weight by 2-4 kg. It should be noted that all the measures described above make it possible to avoid feeding patients through a tube, although in isolated cases this measure is still necessary.

For the first time we used domestic drugs carnitine and cobamamide to remove patients from the state of cachexia.

Carnitine (vitamin W) is an active metabolite. By participating in transmethylation, it stimulates protein biosynthesis. It plays an important role in the processes of acetylation during the oxidation of fatty acids, being an acyl radical acceptor. Participates in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, in the formation of acetyl-CoA.

Participates in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, in the formation of acetyl-CoA.

Treatment started in a clinical setting was continued on an outpatient basis, and half of the patients had repeated courses.

Patients were prescribed carnitine in the form of a 20% aqueous solution of carnitine hydrochloride. The dose of the drug was individual - from 0.75 to 1.5 g, the duration of treatment - from 45 to 120 days. 20 patients were prescribed the drug at a dose of 3-5 tablespoons per day for 25-60 days.

A comparative study showed that patients who received carnitine as part of complex treatment improved their somatic condition earlier than patients in the control group. The effectiveness of the treatment was manifested in an increase in body weight (on average by 6-10 kg), the appearance of a subcutaneous fat layer. Trophic disorders disappeared, the activity of the gastrointestinal tract improved, the menstrual cycle was restored, the level of hemoglobin increased, the metabolism of proteins, lipids and carbohydrates normalized.

It is recommended to prescribe carnitine from 0.75 to 1.5 g per day with a course of treatment up to 60 days (one course). If necessary, you can continue the course of treatment after 6 months for up to 45 days.

A contraindication, according to our data, is hyperacid gastritis, therefore, in the treatment with carnitine, a thorough dynamic laboratory study of gastric secretion is necessary.

In general, the drug is well tolerated both in the form of tablets and in the form of a solution in both clinical and outpatient settings. However, a more convenient form, according to our data, is a carnitine solution.

Cobamamide was prescribed from the first days of treatment of a cachectic state in increasing doses, starting from 0.0005 to 0.003 g (tablets) per day and in the form of daily intramuscular injections of 1 ml. The duration of treatment with cobamamide in tablets ranged from 1 to 3 months, and in injections - from 1 to 1/2 months.

The effectiveness of cobamamide was assessed by the degree of clinical reduction of dystrophic disorders, improvement of blood biochemical parameters, general blood and urine tests, ECG data, etc.

Clinical experience of treatment with cobamamide in patients with anorexia nervosa (compared to patients in the control group) indicates that the drug (especially its injectable form) by the end of the 2nd week of treatment causes a marked improvement in the activity of the gastrointestinal tract. In the future, one can note a gradual increase in the acidity of gastric juice, which by the 2nd month of treatment approached the norm, normalization of the evacuation function, reduction of constipation, and pain along the intestines. All this contributed to an increase in body weight by an average of 7-9kg by the end of the 3rd month of treatment.

In patients, biochemical parameters improved earlier than in the control group: blood sugar returned to normal (80–90 mg%), hemoglobin increased to 120–140 g/l, the number of erythrocytes reached the norm (4.5–1012/l–5– 1012/l), the level of beta-lipoproteins and cholesterol approached the norm. Along with this, the protein in the urine disappeared.

In the process of treatment, the condition of the skin improved significantly: its color and turgor returned to normal, a subcutaneous fat layer appeared, and hair loss stopped. Myocardial trophism improved, although bradycardia persisted for several months. Blood pressure increased (up to 100/60 mm Hg).

Thus, clinical data indicate that cobamamide, as a drug with pronounced anabolic properties, is effective in the treatment of somatic distress resulting from prolonged fasting in patients with anorexia nervosa.

The good tolerability of cobamamide and the absence of complications give reason to recommend it for the complex treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa in clinical practice. Cobamamide is recommended to be prescribed in tablets from 0.0005 to 0.003 g per day for up to 3 months for the first course of treatment. Maintenance doses (outpatient) - 0.0005 g 3 times a day (duration - up to 1/2 month). Intramuscular injections - 1 ml daily for 1/2 month (first course of treatment) and a second course of treatment - after 3-4 months.

The second (specific) stage is the most difficult, since the therapy here is aimed at the disease as a whole. The choice of treatment method depends on the nosological affiliation of the syndrome. However, it is necessary to take into account the special somatic condition of patients.

In the treatment of patients with schizophrenia against the background of ongoing restorative therapy, we gradually increased the doses of neuroleptics under close supervision and control of the somatic state.

Patients with schizophrenia with anorexia syndrome (considering some of their lethargy after recovery from cachexia) were prescribed frenolon (20-30 mg in the morning and afternoon) and tizercin (25-50 mg at night). The choice of frenolone is due to its low toxicity, as well as sedative, anti-anxiety and appetite-stimulating effects.

Sometimes a course of insulin therapy is indicated. This method is more difficult for practical implementation, since patients often try to induce vomiting after stopping the state of hypoglycemia (breakfast), and thus there is a risk of repeated shocks.

For patients with schizophrenia with perverted "eating behavior" (the desire to eat as many foods as possible for "a more complete and pleasant vomiting", caused arbitrarily), fractional doses of chlorpromazine or stelazine (intramuscularly) in combination with insulin proved to be effective. The choice of chlorpromazine or stelazine was determined, on the one hand, by their antiemetic and, on the other hand, by their anorectic action. Apparently, these drugs stabilized to some extent the so-called level of food saturation.

Attempts to use psychotherapy in patients with schizophrenia have not been successful.

The duration of treatment for schizophrenia varied from 2 to 7 months. The body weight of patients increased by an average of 9 kg, their somatic condition returned to normal, but there was no complete criticism of the disease. As before, they carefully dissimulated their condition, they were extremely burdened by being in the hospital. Being discharged for outpatient monitoring and treatment, after some time (4 months - 1 year) they were re-inpatiented in a psychiatric clinic, sometimes in a state of severe cachexia. An analysis of repeated hospitalizations allows us to conclude that rehospitalization is especially necessary for patients with so-called vomiting behavior, since they are the most resistant to various therapeutic effects.

An analysis of repeated hospitalizations allows us to conclude that rehospitalization is especially necessary for patients with so-called vomiting behavior, since they are the most resistant to various therapeutic effects.

The leading method of treating patients with borderline conditions was a combination of drug therapy with various types of psychotherapy. Taking into account the fact that in the first days of their stay in the hospital, patients of this group experienced pronounced protest reactions, that they reacted violently to the very fact of hospitalization, all of them were given small doses of neuroleptics (10 mg of frenolon) or tranquilizers (10 mg of elenium) already at the stage of non-specific treatment. ). In addition, these patients received therapeutic doses of insulin (8-16 IU) throughout the course of treatment.

At the stage of specific treatment, in addition to restorative therapy, patients were prescribed higher doses of neuroleptics, in particular, up to 20-30 mg per day of frenolon. Frenolon not only relieved emotional stress and slightly increased appetite, but also contributed to a more effective psychotherapy. The methods of psychotherapy, carried out by absolutely all patients in this group, varied from rational and suggestive to auto-training. At the same time, the personal characteristics of patients were necessarily taken into account.

Frenolon not only relieved emotional stress and slightly increased appetite, but also contributed to a more effective psychotherapy. The methods of psychotherapy, carried out by absolutely all patients in this group, varied from rational and suggestive to auto-training. At the same time, the personal characteristics of patients were necessarily taken into account.

In the presence of hysterical traits, in accordance with the opinion of most psychotherapists, suggestive methods of psychotherapy are most indicated. That is why we administered suggestion to patients with anorexia nervosa with hysterical character traits in a hypnotic dream or in a waking state. In all cases fairly good results were obtained.

Patients with a predominance of asthenic or psychasthenic character traits are shown the so-called rational psychotherapy according to Dubois-Dejerine. The meaning of this approach was to carefully explain to patients the essence of their disease every day. The main objective of this method of treatment was to make patients realize that their illness is a temporary, transient condition.

Four patients, whose premorbid had hysterical and psychasthenic features, turned out to be resistant to both suggestive and rational psychotherapy. With these patients, a session of auto-training was carried out in the modification of Lebedinsky - Bortnik. This method of treatment made it possible not only to significantly reduce the affective tension of patients, but also to remove various unpleasant vegetative sensations, which are so characteristic of anorexia nervosa.

The listed psychotherapeutic methods were used as part of the complex treatment of patients not only in the hospital, but also in the future - at the stage of their readaptation outside the hospital.

In patients who were in the hospital for an average of 2-3 months, body weight usually increased by 10-11 kg, their somatic condition improved significantly. However, after discharge from the hospital, all of them needed supportive medication and psychotherapy due to the possibility of their recurrence of a tendency to restrict food.

As already mentioned, outpatient treatment was carried out with relatively favorable forms of the disease. In most patients, the syndrome of anorexia nervosa developed within the framework of borderline conditions, the rest suffered from schizophrenia.

Outpatient treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa was carried out according to the same scheme (with slight variations) as in the hospital. But there was no need to carry out all the measures in full at the stage of non-specific treatment. The best results were obtained from the use of fractional doses of frenolon, chlorpromazine and triftazine in combination with psychotherapy. When carrying out the latter, much attention was paid to working not only with patients, but also with their parents, in order to create the most acceptable “family climate” and the correct regimen for patients. The recovery period in these cases was longer than in hospital treatment, and largely depended on the attitude of those close to the disease and the degree of their participation in the treatment.

Summarizing, we can say that the syndrome of anorexia nervosa within the framework of schizophrenia, especially in the presence of ridiculous, frilly "vomiting behavior", is resistant to all types of therapy. These patients are in great need not only of inpatient treatment, but also of carefully considered supportive care. In the treatment of patients with anorexia nervosa of a non-schizophrenic nature, it is necessary to widely use various psychotherapeutic methods (in combination with drug treatment), which is possible both in inpatient and outpatient settings. Among patients of this group, the best therapeutic effect is observed in patients with hysterical character traits, while patients with psychasthenic features show a significantly lower curability.

Family psychotherapy occupies a special place in psychocorrectional work with patients with anorexia nervosa, regardless of its nosological affiliation. Almost all authors of works devoted to the problem of anorexia nervosa note the unfavorable situation in the families of these patients (lack of proper contact with parents, especially the mother, parents' misunderstanding of the condition of the sick teenager, unsettled relations between parents).