Treatment of compulsive hoarding

Hoarding disorder - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

People often don't seek treatment for hoarding disorder, but rather for other issues, such as depression, anxiety or relationship problems. To help diagnose hoarding disorder, it's best to see a mental health provider who has expertise in diagnosing and treating the condition. You'll have a mental health exam that includes questions about emotional well-being. You'll likely be asked about your beliefs and behaviors related to getting and saving items and the impact clutter may have on your quality of life.

Your mental health provider may ask your permission to talk with relatives and friends. Pictures and videos of your living spaces and storage areas affected by clutter are often helpful. You also may be asked questions to find out if you have symptoms of other mental health conditions.

Treatment

Treatment of hoarding disorder can be challenging but effective if you keep working on learning new skills. Some people don't recognize the negative impact of hoarding on their lives or don't believe they need treatment. This is especially true if the possessions or animals offer comfort. If these possessions or animals are taken away, people will often react with frustration and anger. They may quickly collect more to help satisfy emotional needs.

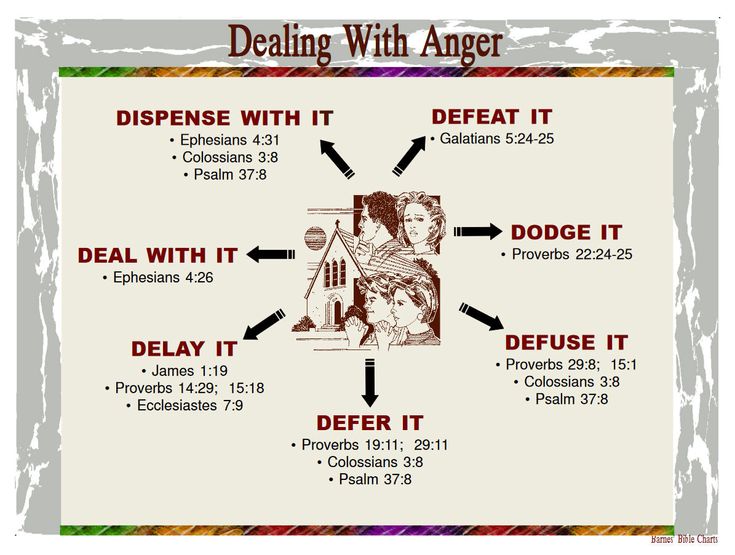

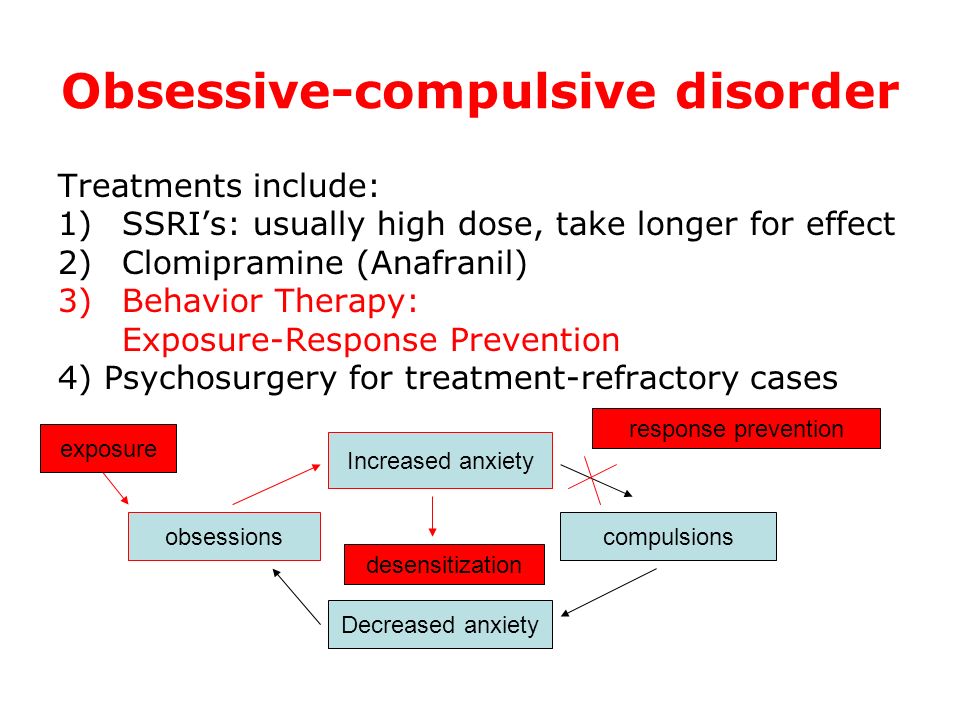

The main treatment for hoarding disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a skills-based approach to therapy. You learn how to better manage beliefs and behaviors that are linked to keeping the clutter. Your provider also may prescribe medicines, especially if you have anxiety or depression along with hoarding disorder.

CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the main treatment for hoarding disorder. Try to find a therapist or other mental health provider with expertise in treating hoarding disorder.

As part of CBT, you may:

- Learn to identify and challenge thoughts and beliefs related to getting and saving items.

- Learn to resist the urge to get more items.

- Learn to organize and group things to help you decide which ones to get rid of, including which items can be donated.

- Improve your decision-making and coping skills.

- Remove clutter in your home during in-home visits by a therapist or professional organizer.

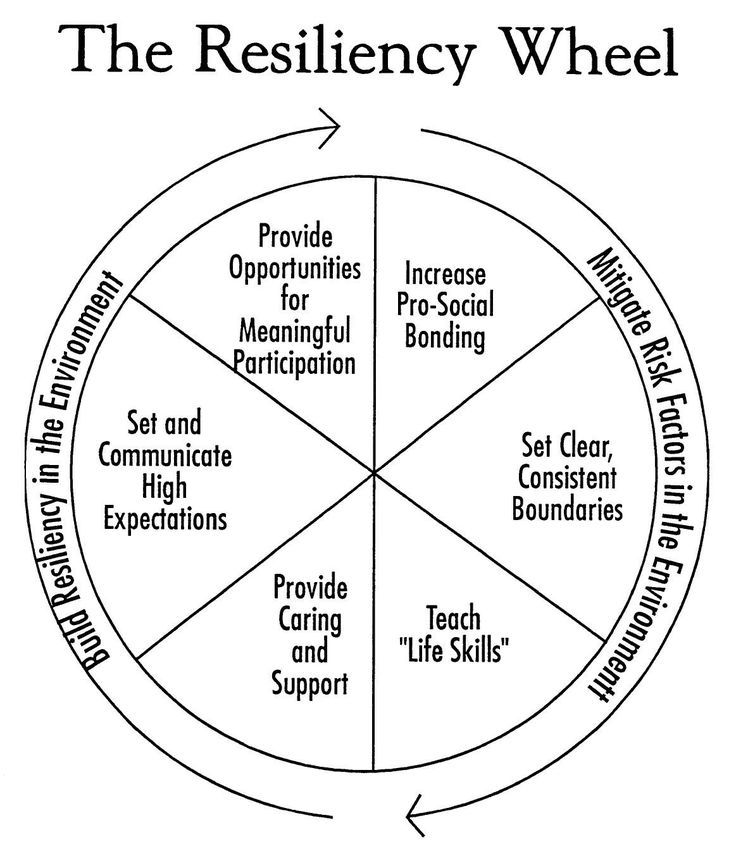

- Learn to reduce isolation and increase opportunities to join in meaningful social activities and supports.

- Learn ways to increase your desire for change.

- Attend family or group therapy.

- Have occasional visits or ongoing treatment to help you keep up healthy habits.

Treatment often involves regular help from family, friends and agencies to help remove clutter. This is often the case for the elderly or those struggling with medical conditions that may make it difficult to keep up the effort and desire to make changes.

Children with hoarding disorder

For children with hoarding disorder, it's important to have the parents involved in treatment. Some parents may think that allowing their child to get and save countless items may help lower their child's anxiety and avoid family fights. This is sometimes called "family accommodation." This actually may do the opposite and strengthen the child's tendency to get and save items.

Some parents may think that allowing their child to get and save countless items may help lower their child's anxiety and avoid family fights. This is sometimes called "family accommodation." This actually may do the opposite and strengthen the child's tendency to get and save items.

In addition to therapy for their child, parents may find professional guidance helpful to learn how to respond to and help manage their child's hoarding behavior.

Medicines

Cognitive behavioral therapy is the first treatment recommended for hoarding disorder. There are currently no medicines approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat hoarding disorder. Medicines are used to treat other conditions such as anxiety and depression that often occur along with hoarding disorder. The medicines most commonly used are a type of antidepressant called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Research continues on the most effective ways to use medicines in the treatment of hoarding disorder.

More Information

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

Request an appointment

Lifestyle and home remedies

In addition to professional treatment, here are some steps you can take to help care for yourself:

- Follow your treatment plan. It's hard work, and it's common to have some setbacks over time. But treatment can help you feel better about yourself, improve your desire to change and reduce your hoarding. Have a daily schedule to work on reducing your clutter. Do this during times of the day when you have the most energy.

- Accept assistance. Local resources, professional organizers and loved ones can work with you to make decisions about how best to organize and unclutter your home and to stay safe and healthy. It may take time to get back to a safe home environment. Help is often needed to stay organized around the home.

- Reach out to others. Hoarding can lead to isolation and loneliness, which in turn can lead to more hoarding.

If you don't want visitors in your house, try to get out to visit friends and family. Joining a support group for people with hoarding disorder can let you know that you are not alone. These groups can help you learn about your behavior and available resources.

If you don't want visitors in your house, try to get out to visit friends and family. Joining a support group for people with hoarding disorder can let you know that you are not alone. These groups can help you learn about your behavior and available resources. - Try to keep yourself clean and neat. If you have possessions piled in your tub or shower, resolve to move them so that you can bathe or shower.

- Make sure you're getting proper nutrition. If you can't use your stove or reach your refrigerator, you may not be eating properly. Try to clear those areas so that you can prepare healthy meals.

- Look out for yourself. Remind yourself that you don't have to live in chaos and distress — that you deserve better. Focus on your goals and what you can gain by reducing clutter in your home.

- Take small steps. With a professional's help, you can tackle one area at a time. Small and consistent wins like this can lead to big wins.

- Do what's best for your pets. If the number of pets you have has grown beyond your ability to care for them properly, remind yourself that they deserve to live healthy and happy lives. That's not possible if you can't provide them with proper nutrition, clean living conditions and veterinary care.

Preparing for your appointment

If you or a loved one has symptoms of hoarding disorder, your health care provider may refer you to a mental health provider, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, with experience diagnosing and treating hoarding disorder.

Because some people with hoarding disorder symptoms don't recognize that their behavior is a problem, you as a friend or family member may experience more distress over the hoarding than your loved one does. If this is the case, you may want to first meet alone with a mental health provider with expertise in treating hoarding disorder. A provider can offer support and help on how to encourage your loved one to seek help.

To consider the possibility of seeking treatment, your loved one will likely need reassurance that no one is going to go into their house and start throwing things out.

Here's some information to help prepare for the first appointment and what to expect from the mental health provider.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Any symptoms you're experiencing, and for how long. It will help the mental health provider to know what kinds of items you feel you have to save and your personal beliefs about getting and keeping items.

- Challenges you have experienced in the past when trying to manage your clutter.

- Key personal information, including traumatic events or losses in your past, such as divorce or the death of a loved one.

- Your medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions.

- Any medicines, vitamins, herbal products or other supplements you take, and their doses.

- Questions to ask your mental health provider.

You may want to take a trusted family member or friend along, if possible. They can offer support and help remember the details discussed at the appointment. Bring pictures and videos of living spaces and storage areas affected by clutter.

Questions to ask your mental health provider include:

- Do you think my symptoms are cause for concern? Why?

- Do you think I need treatment?

- What treatments are most likely to be effective?

- How much can I expect my symptoms to improve with treatment?

- How much time will it take before my symptoms begin to improve?

- How often will I need therapy sessions, and for how long?

- Are there medicines that can help?

Feel free to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your mental health provider

To gain an understanding of how hoarding disorder is affecting your life, your provider may ask:

- What types of things do you tend to get and save?

- Do you avoid throwing things away?

- Do you avoid making decisions about your clutter?

- How often do you decide to get or keep things you don't have space or use for?

- How would it make you feel if you had to get rid of some things?

- Does the clutter in your home keep you from using rooms for their intended purpose?

- Does clutter prevent you from inviting people to visit your home?

- How many pets do you have? Are you able to provide proper care for them?

- Have you tried to reduce the clutter on your own or with the help of friends and family? How successful were those attempts?

- Have your family members expressed concern about the clutter?

- Are you currently being treated for any mental health conditions?

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

What It Is, Causes, Symptoms & Treatment

Overview

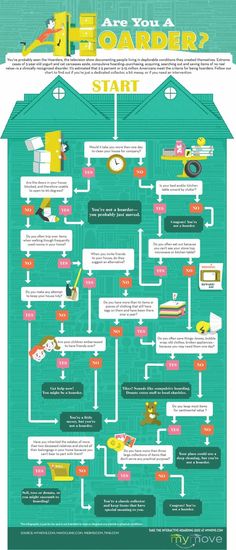

What is hoarding disorder?

Hoarding disorder is a mental health condition in which a person feels a strong need to save a large number of items, whether they have monetary value or not, and experiences significant distress when attempting to get rid of the items. The hoarding impairs their daily life.

The hoarding impairs their daily life.

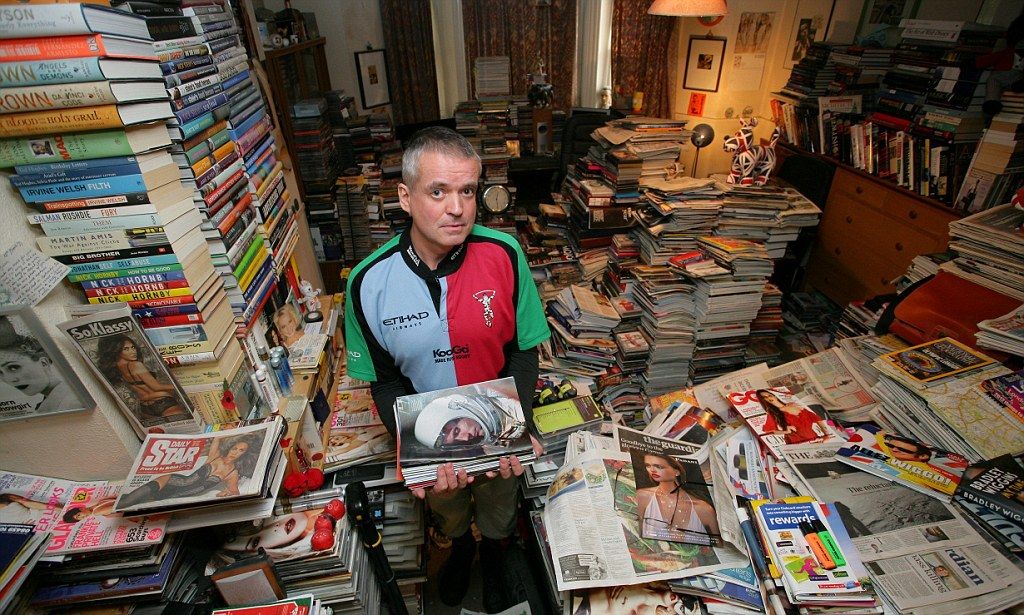

Typical hoarded items include newspapers, magazines, household goods and clothing. Sometimes, people with hoarding disorder accumulate a large number of animals, which are often not properly cared for.

Hoarding disorder can lead to dangerous clutter. The condition can interfere with your quality of life in many ways. It can cause people stress and shame in their social, family and work lives. It can also create unhealthy and unsafe living conditions.

Is hoarding an anxiety disorder?

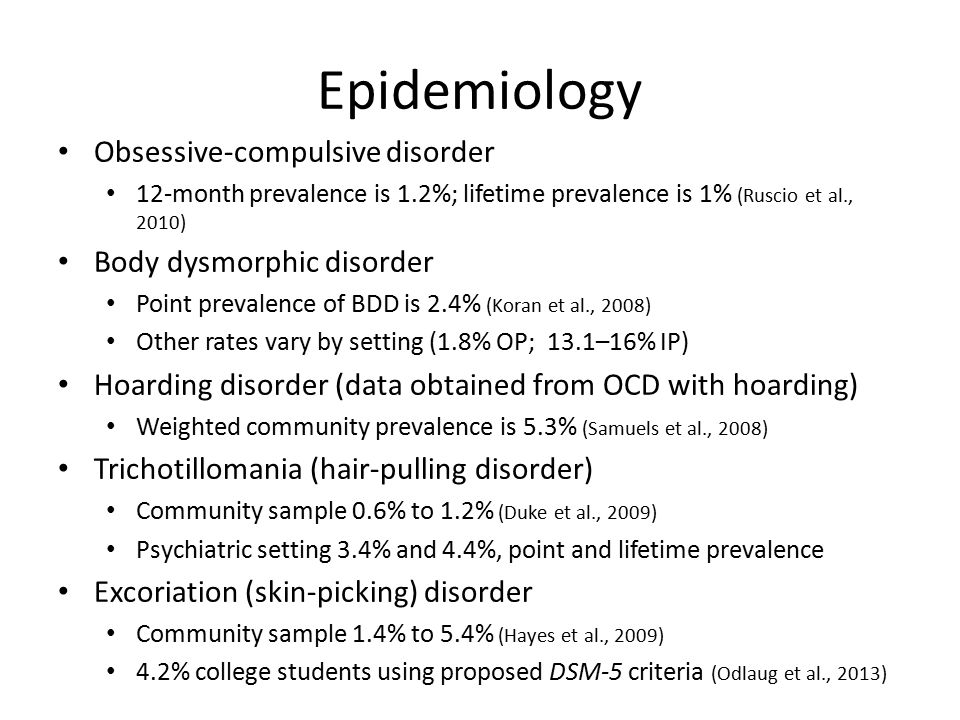

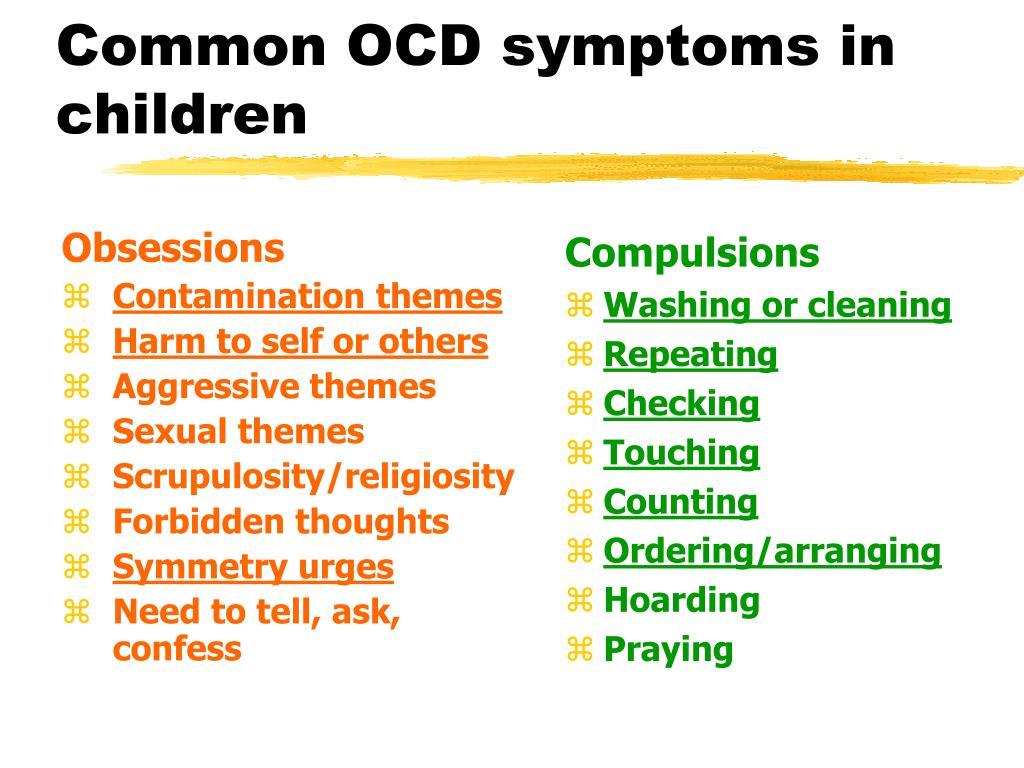

While hoarding disorder is classified as being part of the obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) spectrum, which is an anxiety disorder, hoarding disorder is a distinct condition.

Previously, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the standard classification of mental disorders produced by the American Psychiatric Association, classified hoarding as a subtype of OCD.

However, healthcare providers were encountering people with hoarding behaviors who didn’t have any other mental health conditions. After more research, hoarding disorder was included as an isolated condition, in the OCD spectrum, in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), which is the most recent edition.

After more research, hoarding disorder was included as an isolated condition, in the OCD spectrum, in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), which is the most recent edition.

What is the difference between hoarding and collecting?

Hoarding items and collecting items are distinct behaviors.

Collecting normally involves saving certain types of items, such as comic books, currency or stamps. You’d carefully choose these items and typically organize them in a certain way. Collecting items in this way doesn’t negatively impact your daily life.

Hoarding doesn't involve organization of the items in a way that makes them easy to access or use. People with hoarding disorder often hoard items that have little or no monetary value, such as pieces of paper or broken toys. The hoarding also negatively impacts their daily life.

Who does hoarding disorder affect?

Hoarding disorder often begins during adolescence and gradually worsens with age, causing significant issues by the mid-30s.

Hoarding disorder is more likely to affect people over 60 years old and people with other mental health conditions, especially anxiety and depression.

How common is hoarding disorder?

Approximately 2% to 6% of people in the United States have hoarding disorder.

Symptoms and Causes

What are the symptoms of hoarding disorder?

Some people with hoarding disorder recognize that their hoarding-related beliefs and behaviors are problematic, but many don’t. In many cases, stressful or traumatic events, such as divorce or the death of a loved one, are associated with the onset of hoarding symptoms.

People with hoarding disorder feel a strong need to save their possessions. Other symptoms include:

- Inability to get rid of possessions.

- Experiencing extreme stress when attempting to throw out items.

- Anxiety about needing items in the future.

- Uncertainty about where to put things.

- Distrust of other people touching possessions.

- Living in unusable spaces due to clutter.

- Withdrawing from friends and family.

People with hoarding disorder may hoard items for any of the following reasons:

- They believe that an item will be useful or valuable in the future.

- They feel an item has sentimental value, is unique and/or irreplaceable.

- They think an item is too great of a bargain to throw away.

- They think an item will help them remember an important person or event.

- They can’t decide where an item belongs, so they keep it instead of throwing it away.

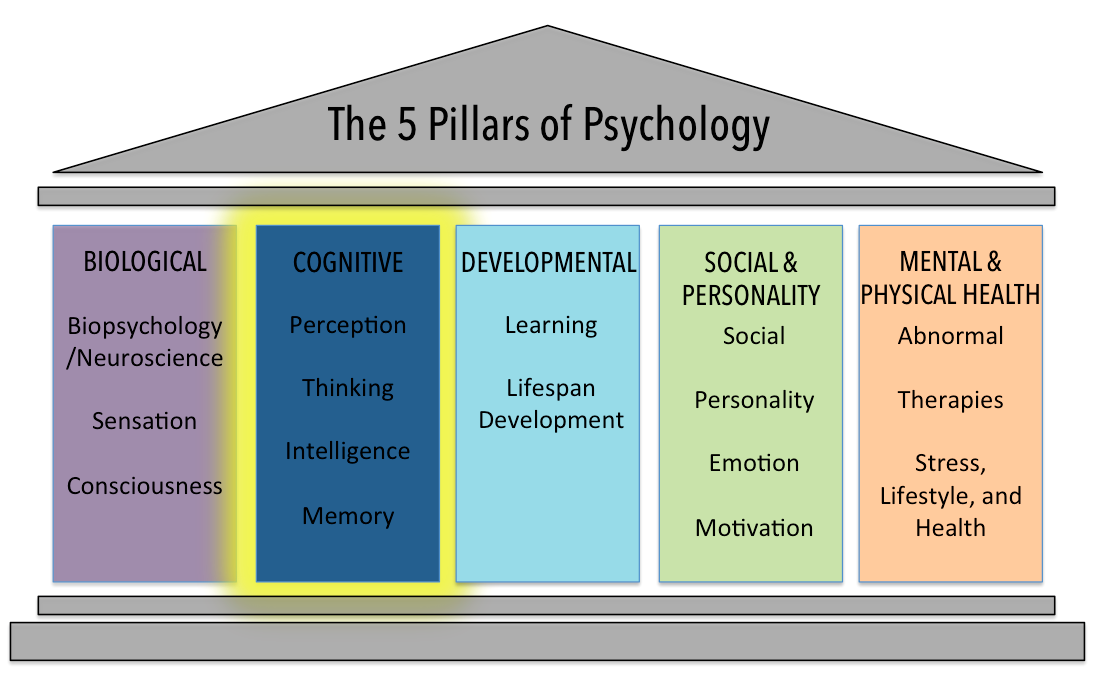

Many people with hoarding disorder also have associated issues with cognitive functioning, including:

- Indecisiveness.

- Perfectionism.

- Procrastination.

- Disorganization.

- Distractibility.

These issues can greatly affect their functioning and the overall severity of hoarding disorder.

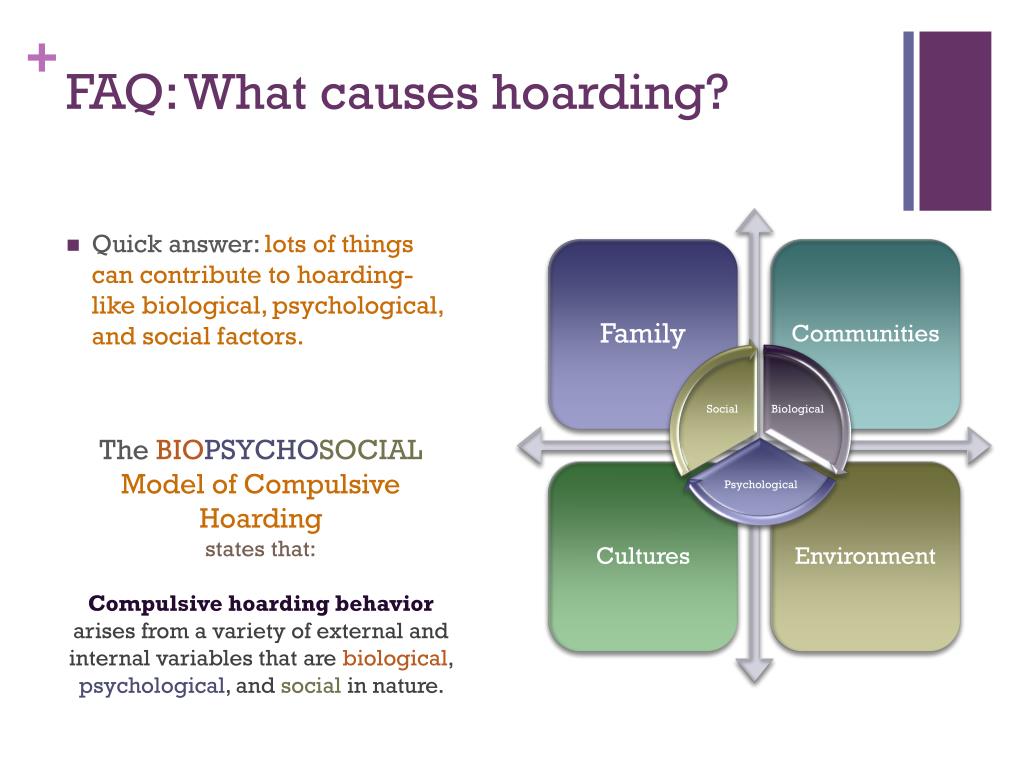

What causes hoarding disorder?

Researchers don’t yet know the exact cause of hoarding disorder. So far, they’ve identified several information (mental) processing deficits associated with hoarding, including issues with:

So far, they’ve identified several information (mental) processing deficits associated with hoarding, including issues with:

- Planning.

- Problem-solving.

- Visuospatial learning and memory.

- Sustained attention.

- Working memory.

- Organization.

Hoarding disorder may exist on its own or may be part of another condition. Mental health conditions most often associated with hoarding disorder include:

- Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD).

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Depression.

Researchers have identified other risk factors associated with hoarding disorder that may make it more likely that you’ll develop the condition, including:

- Having a relative with hoarding disorder.

- Brain injury.

- Traumatic life event.

- Impulsive buying habits.

- Inability to pass up free items, such as coupons and flyers.

- Substance use disorder or alcohol use disorder.

- Prader-Willi syndrome.

Diagnosis and Tests

How is hoarding disorder diagnosed?

People with hoarding disorder rarely seek help on their own. Concerned friends or family members often reach out to a professional to help a loved one with the condition.

Contact a healthcare provider or mental health professional if hoarding makes a living situation unhealthy or unsafe for you or someone you know. If someone you know is hoarding animals, it’s important to contact the correct authorities, such as Animal Control Services, to safely acquire and care for the animals.

To diagnose hoarding disorder, your healthcare provider will ask about your collecting and saving habits. To confirm a diagnosis, the following symptoms must be present:

- Ongoing difficulty getting rid of possessions whether they have value or not.

- Feeling a strong need to save items and feelings of distress associated with discarding items.

- Living spaces that are so filled with possessions that they’re unusable and/or unsafe.

Management and Treatment

How is hoarding disorder treated?

Healthcare providers use two main types of therapies to treat hoarding disorder:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy, a type of talk therapy (psychotherapy).

- Antidepressant medications, which are usually selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a common treatment for hoarding disorder. With the help of a licensed mental health professional, such as a psychologist, people learn to understand why they hoard and how to feel less anxiety when throwing away items. Specialists also teach organization and decision-making skills. These skills can help you better manage your possessions.

Some providers prescribe medications called antidepressants to help treat hoarding disorder. These medicines can improve the symptoms of the condition for some people.

Prevention

Can hoarding disorder be prevented?

There’s no known way to prevent hoarding disorder. However, hoarding behaviors appear relatively early in life (usually between the ages of 15 and 19 years) and then follow a chronic course. If you notice signs of hoarding in your child or someone you know, early recognition, diagnosis and treatment are essential to improving outcomes.

Outlook / Prognosis

What is the prognosis (outlook) for hoarding disorder?

The prognosis (outlook) for hoarding disorder is often poor. While some people with the condition greatly improve after treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy, many people still have symptoms after treatment that impact their day-to-day life.

People with hoarding disorder often have a lack of functional living space, which can prevent them from performing important daily tasks, such as cooking, cleaning, sleeping and bathing. They may also live in unhealthy or unsafe conditions. Serious hoarding can lead to fire hazards, tripping hazards and health code violations.

Serious hoarding can lead to fire hazards, tripping hazards and health code violations.

Hoarding disorder can also cause problems in relationships and social and work activities. It often leads to family strain and conflicts, isolation and loneliness.

Hoarding can affect the social development of children. Unlivable conditions may lead to separation or divorce, eviction and even loss of child custody. People who hoard animals that are in unsafe living conditions may also face prosecution under state animal cruelty laws.

Living With

When should I see my healthcare provider about hoarding disorder?

If you or someone you know is experiencing symptoms of hoarding disorder, contact your healthcare provider or a mental health professional.

In some communities, public health agencies can assist in addressing hoarding problems. In some cases, it may be necessary for animal welfare agencies to intervene.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

It’s important to remember that hoarding disorder is a mental health condition — it’s not a matter of laziness or willpower. As with all mental health conditions, seeking professional help as soon as symptoms appear can help decrease the disruptions to your life. Mental health professionals can offer treatment plans that can help you manage your thoughts and behaviors related to hoarding.

As with all mental health conditions, seeking professional help as soon as symptoms appear can help decrease the disruptions to your life. Mental health professionals can offer treatment plans that can help you manage your thoughts and behaviors related to hoarding.

The family members of people with hoarding disorder often experience stress, depression, grief and isolation. It’s important to take care of your mental health and seek help if you’re experiencing these symptoms.

Scientists told how to treat pathological hoarding

Plushkin's syndrome is a much more common thing than it might seem.

In a new paper, Australian scientists have formulated strategies for treating pathological hoarding, which was recognized as a mental disorder in 2013.

The work was published in Prescriber magazine, Science Alert talks about it briefly.

Despite the image we are accustomed to from books and films, most "hoarders" do not fit the dramatic stereotype of life in poverty.

Researchers report that 2-6% of people suffer from hoarding disorder. This mental disorder often manifests itself as a coping mechanism when a person struggles with other conditions, from grief and depression to recovering from traumatic brain injury. In other words, pathological hoarding is much more common than we are used to thinking and can happen to anyone.

The patient has difficulty throwing away or parting with things, regardless of their value. In his picture of the world, there is a conscious need to save objects, and when throwing them away, a person experiences suffering.

Hoarding behavior becomes a disorder when the things a person keeps begin to interfere with his own life or the lives of others. At first, many gatherers are socially active members of society. The development of the disease leads to the accumulation of things that increasingly clutter up the house up to the complete impossibility of using this room. Some patients spend the night in the car or on the street because of the inability to enter the house filled with things.

Some patients spend the night in the car or on the street because of the inability to enter the house filled with things.

“One of the main hallmarks of this condition is denial of care, so clinicians are in the unique position of not immediately agreeing with patients' desire to remain untreated,” the scientists explained. “Instead, gentle, persistent attempts to help should be made, combined with emotional support, even if the person refuses to open the door.”

The researchers emphasize that once help has been accepted, physicians must first address other problems that may worsen accumulation. In more than 50% of cases, hoarding coexists with other conditions such as mental disorders (depression or alcohol abuse) or physical ailments (arthritis).

MRI scans have shown that people with storage disorders tend to have fewer neural connections in areas of the brain associated with cognitive control, but more connections in parts of the brain that focus on the inner world. This explains the inability of patients to comprehend the real value and meaning of the collected things.

This explains the inability of patients to comprehend the real value and meaning of the collected things.

Researchers recommend CBT. In some cases, drugs used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder are effective.

Scientists emphasize that a multidisciplinary approach is required in the treatment of pathological hoarding. Such patients need emotional support and a sense of security.

Photo: Shutterstock

Hallucinations in mice helped to understand the cause of psychosis

Researchers have found that money really makes people happier

Materials from Facebook and Instagram Internet resources owned by Meta Platforms Inc. banned on the territory of the Russian Federation

Tell a friend

-

From toilet paper to letters "from the other world": what you can get by subscription

-

Shutterstock

Named professions that will not be the same after the advent of ChatGPT

-

The control signal (green) activates a set of switches on the metal strip.

The electromagnetic impedance of the metamaterial changes abruptly, as a result of which the direct propagating signal (marked in blue) is partially reflected in time (marked

The electromagnetic impedance of the metamaterial changes abruptly, as a result of which the direct propagating signal (marked in blue) is partially reflected in time (marked Andrea Alu/ City University of New York's Advanced Science Research Center

After decades of searching, physicists have discovered 'reflections of time'

-

Shutterstock

The study showed what feature helped the dinosaurs to dominate the planet for so long

-

Midjourney

Unbalance, selfishness and just a lie? Why You Shouldn't Trust Chatbots

Do you want to be aware of the latest developments in science?

Leave your email and subscribe to our newsletter

Your e-mail

By clicking on the "Subscribe" button, you agree to the processing of personal data

What is pathological hoarding and how to get rid of it

housing is filled with rubbish and garbage. Understanding what causes PN and how it is treated0005

Understanding what causes PN and how it is treated0005

Your browser does not support the audio player.

The guys from the Trends team discussed this material in the episode of the Flying Podcast. You can listen on any convenient platform: in the player above, in Apple Podcasts, CastBox, Yandex.Music, Google Podcasts and wherever there are podcasts.

Causes of pathological hoarding

Scientists used to classify pathological hoarding as a type of OCD, but now they classify it as a separate mental illness. PN can occur gradually: a person is immersed in the illusion that some things will be useful to him in the future, which is why he begins to store them at home. The development of the disease can be spurred by tragic events. In addition, people who:

- live alone;

- have recently experienced the loss of a loved one;

- already suffer from mental problems (including ADHD, depression, dementia, OCD, schizophrenia).

Who suffers from pathological hoarding

Pathological hoarding is quite widespread. From 2% to 6% of the world's population in various forms are subject to it. At the same time, approximately every fiftieth person on the planet suffers from especially neglected forms of PN. They are equally common in men and women. Age plays a significant role: in people who have reached the age of 55, PN can develop with a probability three times greater than in 20-30 years.

From 2% to 6% of the world's population in various forms are subject to it. At the same time, approximately every fiftieth person on the planet suffers from especially neglected forms of PN. They are equally common in men and women. Age plays a significant role: in people who have reached the age of 55, PN can develop with a probability three times greater than in 20-30 years.

Symptoms of hoarding

Due to the fact that hoarding develops gradually, the person may not be aware of the deterioration. In order not to start the disease, it is worth looking closely at the symptoms. They may include:

- the inability to part with things: both expensive and worthless;

- complete disorder at home or workplace;

- inability to find the right thing among a pile of others;

- inability to throw away an item for fear that it will ever be needed;

- attachment to a large number of things due to the fact that they remind of a person or period in one's life;

- storage of packages, bags and other garbage;

- throwing off the blame for disorganization in life on the condition of the house;

- avoiding guests because of shame about the state of the house;

- postponing repairs for later due to piles of rubbish.

One of the most striking descriptions of pathological hoarding can be found in Nikolai Gogol's poem Dead Souls. The landowner Stepan Plyushkin suffers from him:

“He still walked every day through the streets of his village, looked under the bridges, under the crossbars and everything that came across to him: an old sole, a woman's rag, an iron nail, a clay shard, - he dragged everything to himself and put it in that heap that Chichikov noticed in the corner of the room ... after him there was no need to sweep the street: it happened to a passing officer to lose his spur, this spur instantly went to the well-known heap: if a woman ... forgot the bucket, he dragged the bucket away.

Tragic circumstances probably led Plyushkin to this state: the death of his wife, the flight of his daughter with her fiancé, the departure of his son and the death of his second daughter. This correlates with the standard causes of pathological hoarding.

How to treat pathological hoarding

In order to treat pathological hoarding, a person first needs to recognize the problem. This is usually the most difficult part. After it, the patient can be helped in several ways.

This is usually the most difficult part. After it, the patient can be helped in several ways.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy . In the context of PN, it focuses on changing a person's behavior so that he himself comes to the idea of the uselessness of trash in his house.

- Support groups . Like Alcoholics Anonymous, Accumulators Anonymous meets once a week to share their progress and support each other.

- Medicines . A specialist may prescribe mild antidepressants to help manage the negative emotions that cause hoarding.

One of the most important aspects of the fight against pathological hoarding is the support of loved ones. If you feel that your friend or relative is starting to show symptoms of illness, follow these tips:

- don't help him save money;

- Recommend professional help;

- support him without criticism;

- Discuss ways to make his home safer;

- be kind, sympathetic and gentle.