How to learn resilience

Five Science-Backed Strategies to Build Resilience

A mentor of mine recently passed away, and I was heartbroken—so I tried my best to avoid thinking about it. I didn’t even mention it to my family because I didn’t want those sad feelings to resurface.

In other words, I took the very enlightened approach of pretend it didn’t happen—one that’s about as effective as other common responses such as get angry, push people away, blame yourself, or wallow in the pain.

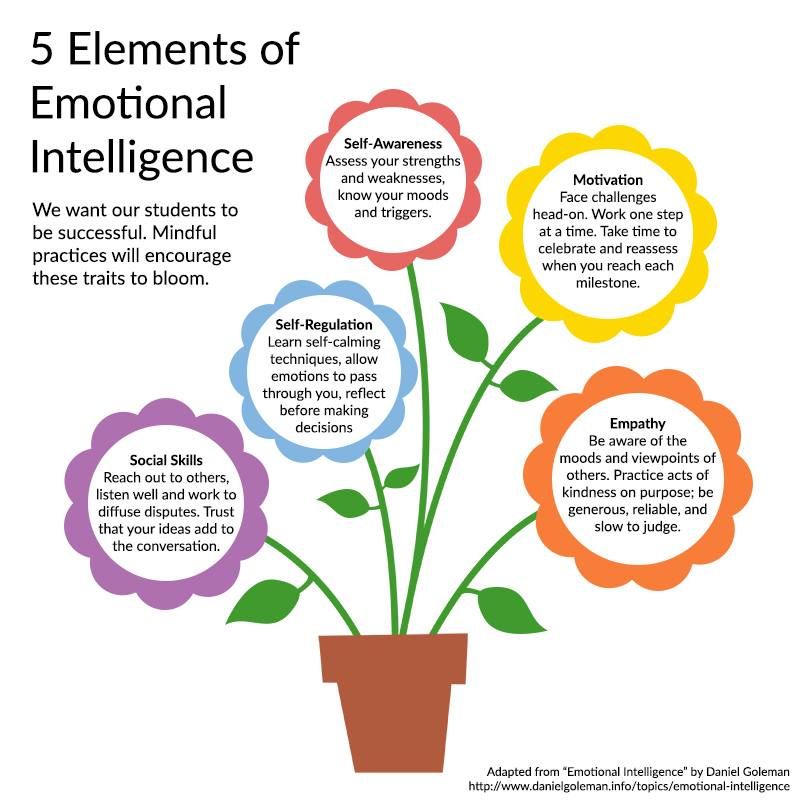

Even for the relatively self-aware and emotionally adept, struggles can take us by surprise. But learning healthy ways to move through adversity—a collection of skills that researchers call resilience—can help us cope better and recover more quickly, or at least start heading in that direction.

Advertisement XMeet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

The Greater Good Science Center has collected many resilience practices on our website Greater Good in Action, alongside other research-based exercises for fostering kindness, connection, and happiness. Here are 12 of those resilience practices (squeezed into five categories), which can help you confront emotional pain more skillfully.

1. Change the narrative

When something bad happens, we often relive the event over and over in our heads, rehashing the pain. This process is called rumination; it’s like a cognitive spinning of the wheels, and it doesn’t move us forward toward healing and growth.

The practice of Expressive Writing can move us forward by helping us gain new insights on the challenges in our lives. It involves free writing continuously for 20 minutes about an issue, exploring your deepest thoughts and feelings around it. The goal is to get something down on paper, not to create a memoir-like masterpiece.

A 1988 study found that participants who did Expressive Writing for four days were healthier six weeks later and happier up to three months later, when compared to people who wrote about superficial topics. In writing, the researchers suggest, we’re forced to confront ideas one by one and give them structure, which may lead to new perspectives. We’re actually crafting our own life narrative and gaining a sense of control.

We’re actually crafting our own life narrative and gaining a sense of control.

Once we’ve explored the dark side of an experience, we might choose to contemplate some of its upsides. Finding Silver Linings invites you to call to mind an upsetting experience and try to list three positive things about it. For example, you might reflect on how fighting with a friend brought some important issues out into the open, and allowed you to learn something about their point of view.

In a 2014 study, doing this practice daily for three weeks helped participants become more engaged with life afterward, and it decreased their pessimistic beliefs over time. This wasn’t true for a group whose members just wrote about their daily activities. It was particularly beneficial for staunch pessimists, who also became less depressed. But the effects wore off after two months, suggesting that looking on the bright side is something we have to practice regularly.

2. Face your fears

The practices above are helpful for past struggles, ones that we’ve gained enough distance from to be able to get some perspective. But what about knee-shaking fears that we’re experiencing in the here and now?

But what about knee-shaking fears that we’re experiencing in the here and now?

The Overcoming a Fear practice is designed to help with everyday fears that get in the way of life, such as the fear of public speaking, heights, or flying. We can’t talk ourselves out of such fears; instead, we have to tackle the emotions directly.

The first step is to slowly, and repeatedly, expose yourself to the thing that scares you—in small doses. For example, people with a fear of public speaking might try talking more in meetings, then perhaps giving a toast at a small wedding. Over time, you can incrementally increase the challenge until you’re ready to nail that big speech or TV interview.

In a 2010 study, researchers modeled this process in the lab. They gave participants a little electrical shock every time they saw a blue square, which soon became as scary as a tarantula to an arachnophobe. But then, they showed the blue square to participants without shocking them. Over time, the participants’ Pavlovian fear (measured by the sweat on their skin) gradually evaporated.

In effect, this kind of “exposure therapy” helps us change the associations we have with a particular stimulus. If we’ve flown 100 times and the plane has never crashed, for example, our brain (and body) start to learn that it’s safe. Though the fear may never be fully extinguished, we’ll likely have greater courage to confront it.

3. Practice self-compassion

I’ve never been a good flyer myself, and it was comforting when an acquaintance shared an article he wrote about having the same problem (and his favorite tips). Fears and adversity can make us feel alone; we wonder why we’re the only ones feeling this way, and what exactly is wrong with us. In these situations, learning to practice self-compassion—and recognizing that everyone suffers—can be a much gentler and more effective road to healing.

Self-compassion involves offering compassion to ourselves: confronting our own suffering with an attitude of warmth and kindness, without judgment. In one study, participants in an eight-week Mindful Self-Compassion program reported more mindfulness and life satisfaction, with lower depression, anxiety, and stress afterward compared to people who didn’t participate—and the benefits lasted up to a year.

One practice, the Self-Compassion Break, is something you can do any time you start to feel overwhelmed by pain or stress. It has three steps, which correspond to the three aspects of self-compassion:

- Be mindful: Without judgment or analysis, notice what you’re feeling. Say, “This is a moment of suffering” or “This hurts” or “This is stress.”

- Remember that you’re not alone: Everyone experiences these deep and painful human emotions, although the causes might be different. Say to yourself, “Suffering is a part of life” or “We all feel this way” or “We all struggle in our lives.”

- Be kind to yourself: Put your hands on your heart and say something like “May I give myself compassion” or “May I accept myself as I am” or “May I be patient.”

If being kind to yourself is a challenge, an exercise called How Would You Treat a Friend? could help. Here, you compare how you respond to your own struggles—and the tone you use—with how you respond to a friend’s. Often, this comparison unearths some surprising differences and valuable reflections: Why am I so harsh on myself, and what would happen if I weren’t?

Often, this comparison unearths some surprising differences and valuable reflections: Why am I so harsh on myself, and what would happen if I weren’t?

Once we start to develop a kinder attitude toward ourselves, we can crystallize that gentle voice in a Self-Compassionate Letter. This practice asks you to spend 15 minutes writing words of understanding, acceptance, and compassion toward yourself about a specific struggle that you feel ashamed of—say, being shy or not spending enough time with your kids. In the letter, you might remind yourself that everyone struggles, and that you aren’t solely responsible for this shortcoming; if possible, you could also consider constructive ways to improve in the future.

4. Meditate

As mindfulness gurus like to remind us, our most painful thoughts are usually about the past or the future: We regret and ruminate on things that went wrong, or we get anxious about things that will. When we pause and bring our attention to the present, we often find that things are…okay.

Practicing mindfulness brings us more and more into the present, and it offers techniques for dealing with negative emotions when they arise. That way, instead of getting carried away into fear, anger, or despair, we can work through them more deliberately.

One of the most commonly studied mindfulness programs is the eight-week-long Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), which teaches participants to cope with challenges using a variety of meditation practices (including the ones detailed below). Various studies have found that MBSR has wide-ranging health and psychological benefits for people in general, as well as those struggling with mental illness or chronic disease.

One meditation that might be particularly effective at calming our negative thoughts is the Body Scan. Here, you focus on each body part in turn—head to toe—and can choose to let go of any areas of tension you discover. Strong feelings tend to manifest physically, as tight chests or knotted stomachs, and relaxing the body is one way to begin dislodging them.

In one study, researchers found that time spent practicing the Body Scan was linked to greater well-being and less reactivity to stress. Being more aware of our bodies—and the emotions they are feeling—might also help us make healthier choices, trusting our gut when something feels wrong or avoiding commitments that will lead to exhaustion.

When stress creeps in, good habits often creep out—and one of those is healthy eating. When we’re emotional, many of us reach for the sweets; when we’re short on time, fast food seems like the only option. So in addition to helping us cultivate mindfulness, the Raisin Meditation could help change our relationship to food.

This exercise invites you to eat a raisin mindfully—but wait, not so fast. First, examine its wrinkles and color; see how it feels between your fingers, and then take a sniff. Slowly place it on your tongue, and roll it around in your mouth before chewing one bite at a time. Notice the urge to swallow, and whether you can sense it moving down your throat into your stomach. Not only will you have practiced mindfulness, but you may never look at food the same way again.

Not only will you have practiced mindfulness, but you may never look at food the same way again.

-

More on Stress & Resilience

Kelly McGonigal explains how to transform stress into courage and connection.

Robert Sapolsky explores the psychology of stress.

Jeremy Adam Smith explains the relationship between stress and empathy.

How stressed are you? Take the quiz!

One final meditation that we can sprinkle throughout our day—or practice on its own—is Mindful Breathing. It involves bringing attention to the physical sensations of the breath: the air moving through the nostrils, the expansion of the chest, the rise and fall of the stomach. If the mind wanders away, you bring attention back. This can be done during a full 15-minute meditation, or during a moment of stress with just a few breaths.

In one study, participants who did a Mindful Breathing exercise before looking at disturbing images—like spiders or car crashes—experienced less negative emotion than people who hadn’t done the exercise. Negative thoughts can pull us along into their frantic stream, but the breath is an anchor we can hold onto at any time.

Negative thoughts can pull us along into their frantic stream, but the breath is an anchor we can hold onto at any time.

5. Cultivate forgiveness

If holding a grudge is holding you back, research suggests that cultivating forgiveness could be beneficial to your mental and physical health. If you feel ready to begin, it can be a powerful practice.

Both Nine Steps to Forgiveness and Eight Essentials When Forgiving offer a list of guidelines to follow. In both cases, you begin by clearly acknowledging what happened, including how it feels and how it’s affecting your life right now. Then, you make a commitment to forgive, which means letting go of resentment and ill will for your own sake; forgiveness doesn’t mean letting the offender off the hook or even reconciling with them. Ultimately, you can try to find a positive opportunity for growth in the experience: Perhaps it alerted you to something you need, which you may have to look for elsewhere, or perhaps you can now understand other people’s suffering better.

If you’re having trouble forgiving, Letting Go of Anger through Compassion is a five-minute forgiveness exercise that could help you get unstuck. Here, you spend a few minutes generating feelings of compassion toward your offender; she, too, is a human being who makes mistakes; he, too, has room for growth and healing. Be mindfully aware of your thoughts and feelings during this process, and notice any areas of resistance.

Not convinced this is the best approach? Researchers tested it against the common alternatives—either ruminating on negative feelings or repressing them—and found that cultivating compassion led participants to report more empathy, positive emotions, and feelings of control. That’s an outcome that victims of wrongdoing deserve, no matter how we feel about the offenders.

Stress and struggles come in many forms in life: adversity and trauma, fear and shame, betrayals of trust. The 12 practices above can help you cope with difficulties when they arise, but also prepare you for challenges in the future. With enough practice, you’ll have a toolbox of techniques that come naturally—a rainy-day fund for the mind, that will help keep you afloat when times get tough. Just knowing that you’ve built up your skills of resilience can be a great comfort, and even a happiness booster.

With enough practice, you’ll have a toolbox of techniques that come naturally—a rainy-day fund for the mind, that will help keep you afloat when times get tough. Just knowing that you’ve built up your skills of resilience can be a great comfort, and even a happiness booster.

How People Learn to Become Resilient

Norman Garmezy, a developmental psychologist and clinician at the University of Minnesota, met thousands of children in his four decades of research. But one boy in particular stuck with him. He was nine years old, with an alcoholic mother and an absent father. Each day, he would arrive at school with the exact same sandwich: two slices of bread with nothing in between. At home, there was no other food available, and no one to make any. Even so, Garmezy would later recall, the boy wanted to make sure that “no one would feel pity for him and no one would know the ineptitude of his mother.” Each day, without fail, he would walk in with a smile on his face and a “bread sandwich” tucked into his bag.

The boy with the bread sandwich was part of a special group of children. He belonged to a cohort of kids—the first of many—whom Garmezy would go on to identify as succeeding, even excelling, despite incredibly difficult circumstances. These were the children who exhibited a trait Garmezy would later identify as “resilience.” (He is widely credited with being the first to study the concept in an experimental setting.) Over many years, Garmezy would visit schools across the country, focussing on those in economically depressed areas, and follow a standard protocol. He would set up meetings with the principal, along with a school social worker or nurse, and pose the same question: Were there any children whose backgrounds had initially raised red flags—kids who seemed likely to become problem kids—who had instead become, surprisingly, a source of pride? “What I was saying was, ‘Can you identify stressed children who are making it here in your school?’ ” Garmezy said, in a 1999 interview. “There would be a long pause after my inquiry before the answer came. If I had said, ‘Do you have kids in this school who seem to be troubled?,’ there wouldn’t have been a moment’s delay. But to be asked about children who were adaptive and good citizens in the school and making it even though they had come out of very disturbed backgrounds—that was a new sort of inquiry. That’s the way we began.”

“There would be a long pause after my inquiry before the answer came. If I had said, ‘Do you have kids in this school who seem to be troubled?,’ there wouldn’t have been a moment’s delay. But to be asked about children who were adaptive and good citizens in the school and making it even though they had come out of very disturbed backgrounds—that was a new sort of inquiry. That’s the way we began.”

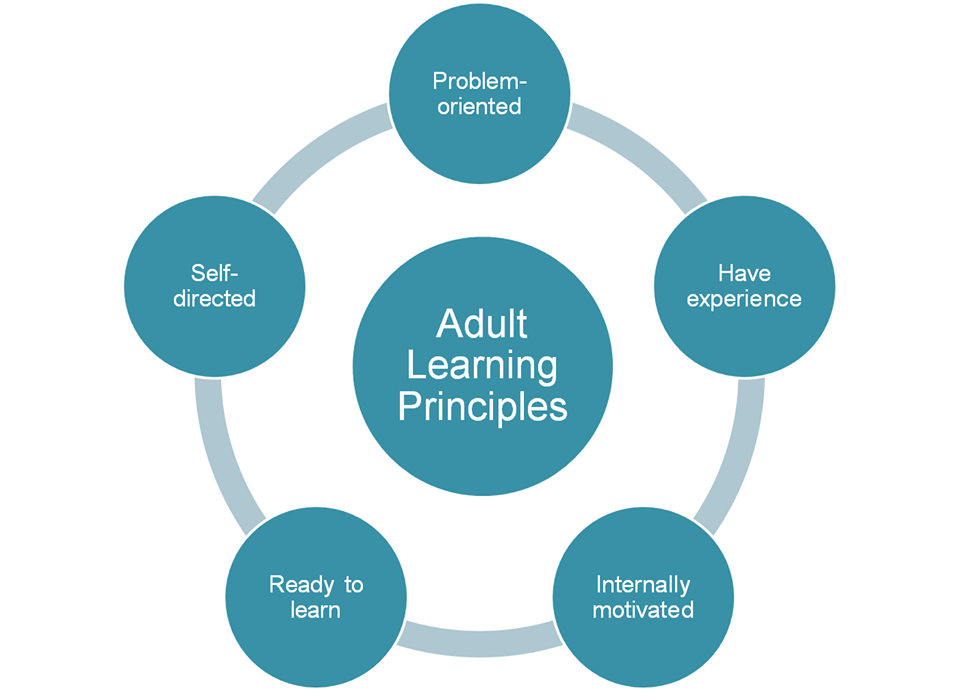

Resilience presents a challenge for psychologists. Whether you can be said to have it or not largely depends not on any particular psychological test but on the way your life unfolds. If you are lucky enough to never experience any sort of adversity, we won’t know how resilient you are. It’s only when you’re faced with obstacles, stress, and other environmental threats that resilience, or the lack of it, emerges: Do you succumb or do you surmount?

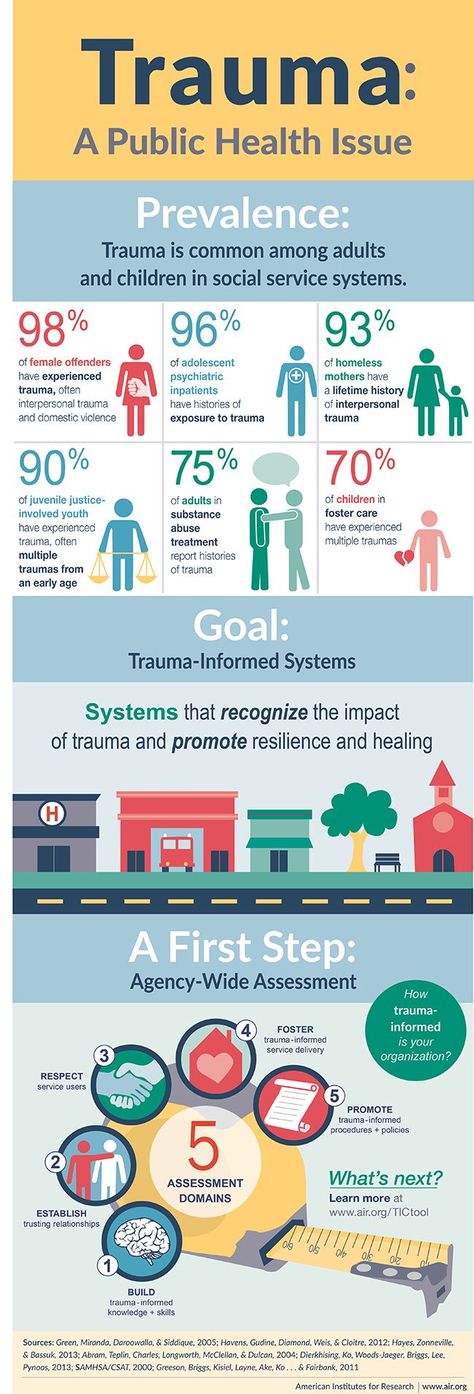

Environmental threats can come in various guises. Some are the result of low socioeconomic status and challenging home conditions. (Those are the threats studied in Garmezy’s work. ) Often, such threats—parents with psychological or other problems; exposure to violence or poor treatment; being a child of problematic divorce—are chronic. Other threats are acute: experiencing or witnessing a traumatic violent encounter, for example, or being in an accident. What matters is the intensity and the duration of the stressor. In the case of acute stressors, the intensity is usually high. The stress resulting from chronic adversity, Garmezy wrote, might be lower—but it “exerts repeated and cumulative impact on resources and adaptation and persists for many months and typically considerably longer.”

) Often, such threats—parents with psychological or other problems; exposure to violence or poor treatment; being a child of problematic divorce—are chronic. Other threats are acute: experiencing or witnessing a traumatic violent encounter, for example, or being in an accident. What matters is the intensity and the duration of the stressor. In the case of acute stressors, the intensity is usually high. The stress resulting from chronic adversity, Garmezy wrote, might be lower—but it “exerts repeated and cumulative impact on resources and adaptation and persists for many months and typically considerably longer.”

Prior to Garmezy’s work on resilience, most research on trauma and negative life events had a reverse focus. Instead of looking at areas of strength, it looked at areas of vulnerability, investigating the experiences that make people susceptible to poor life outcomes (or that lead kids to be “troubled,” as Garmezy put it). Garmezy’s work opened the door to the study of protective factors: the elements of an individual’s background or personality that could enable success despite the challenges they faced. Garmezy retired from research before reaching any definitive conclusions—his career was cut short by early-onset Alzheimer’s—but his students and followers were able to identify elements that fell into two groups: individual, psychological factors and external, environmental factors, or disposition on the one hand and luck on the other.

Garmezy retired from research before reaching any definitive conclusions—his career was cut short by early-onset Alzheimer’s—but his students and followers were able to identify elements that fell into two groups: individual, psychological factors and external, environmental factors, or disposition on the one hand and luck on the other.

In 1989 a developmental psychologist named Emmy Werner published the results of a thirty-two-year longitudinal project. She had followed a group of six hundred and ninety-eight children, in Kauai, Hawaii, from before birth through their third decade of life. Along the way, she’d monitored them for any exposure to stress: maternal stress in utero, poverty, problems in the family, and so on. Two-thirds of the children came from backgrounds that were, essentially, stable, successful, and happy; the other third qualified as “at risk.” Like Garmezy, she soon discovered that not all of the at-risk children reacted to stress in the same way. Two-thirds of them “developed serious learning or behavior problems by the age of ten, or had delinquency records, mental health problems, or teen-age pregnancies by the age of eighteen. ” But the remaining third developed into “competent, confident, and caring young adults.” They had attained academic, domestic, and social success—and they were always ready to capitalize on new opportunities that arose.

” But the remaining third developed into “competent, confident, and caring young adults.” They had attained academic, domestic, and social success—and they were always ready to capitalize on new opportunities that arose.

What was it that set the resilient children apart? Because the individuals in her sample had been followed and tested consistently for three decades, Werner had a trove of data at her disposal. She found that several elements predicted resilience. Some elements had to do with luck: a resilient child might have a strong bond with a supportive caregiver, parent, teacher, or other mentor-like figure. But another, quite large set of elements was psychological, and had to do with how the children responded to the environment. From a young age, resilient children tended to “meet the world on their own terms.” They were autonomous and independent, would seek out new experiences, and had a “positive social orientation.” “Though not especially gifted, these children used whatever skills they had effectively,” Werner wrote. Perhaps most importantly, the resilient children had what psychologists call an “internal locus of control”: they believed that they, and not their circumstances, affected their achievements. The resilient children saw themselves as the orchestrators of their own fates. In fact, on a scale that measured locus of control, they scored more than two standard deviations away from the standardization group.

Perhaps most importantly, the resilient children had what psychologists call an “internal locus of control”: they believed that they, and not their circumstances, affected their achievements. The resilient children saw themselves as the orchestrators of their own fates. In fact, on a scale that measured locus of control, they scored more than two standard deviations away from the standardization group.

Werner also discovered that resilience could change over time. Some resilient children were especially unlucky: they experienced multiple strong stressors at vulnerable points and their resilience evaporated. Resilience, she explained, is like a constant calculation: Which side of the equation weighs more, the resilience or the stressors? The stressors can become so intense that resilience is overwhelmed. Most people, in short, have a breaking point. On the flip side, some people who weren’t resilient when they were little somehow learned the skills of resilience. They were able to overcome adversity later in life and went on to flourish as much as those who’d been resilient the whole way through. This, of course, raises the question of how resilience might be learned.

This, of course, raises the question of how resilience might be learned.

The Resilient: How to Become More Resilient

Know Yourself

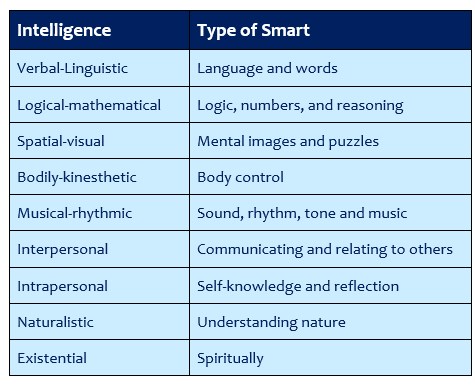

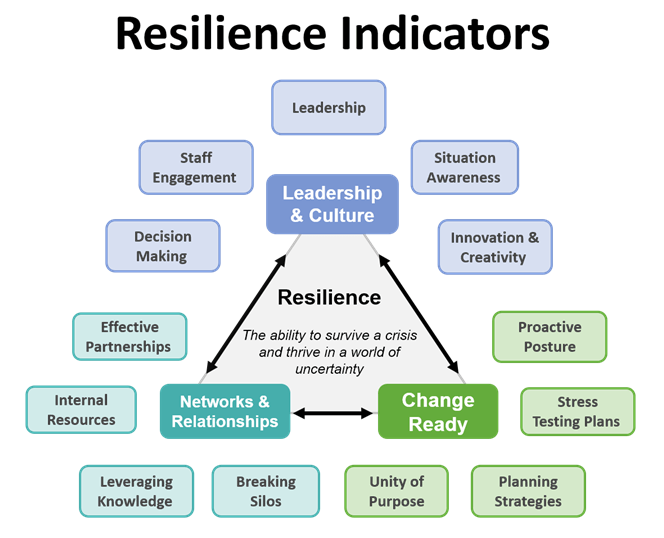

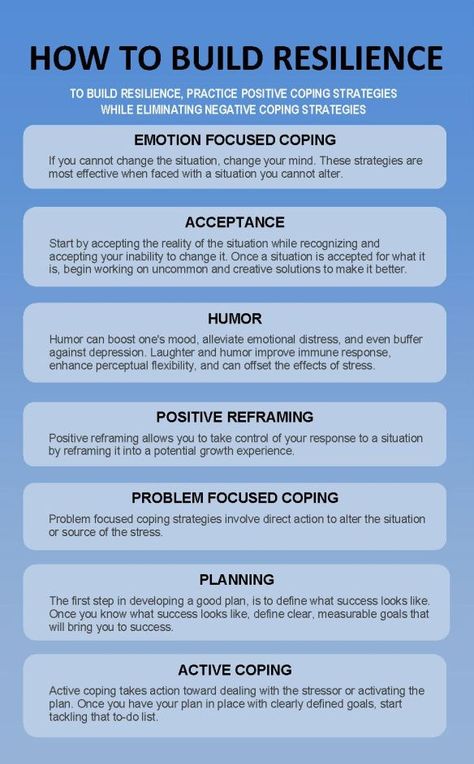

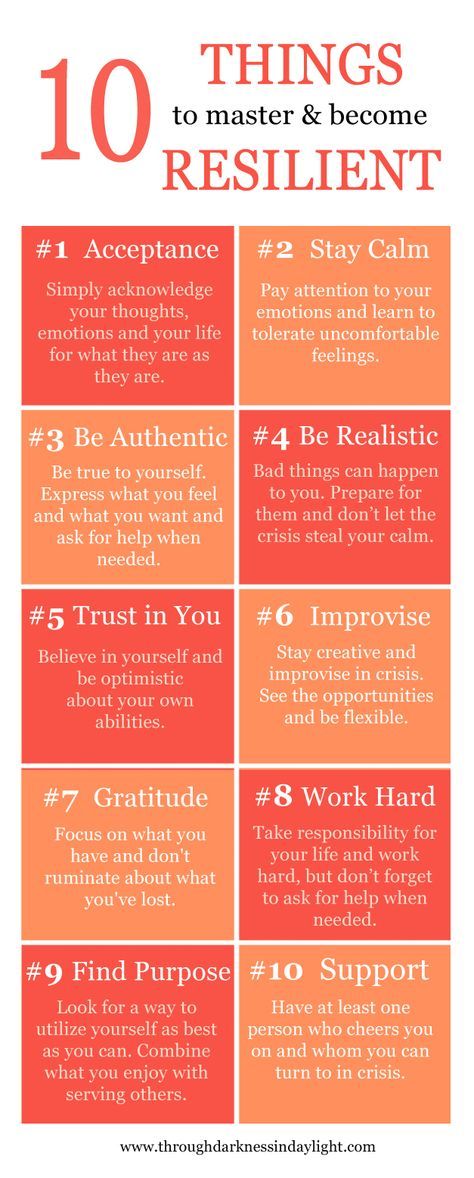

According to the American Psychological Association, several factors distinguish resilient people:

— They have a “support group”: people they trust, who love them and are always ready to support them.

— They know how to set themselves realistic goals and achieve them.

- They have developed communication and problem-solving skills.

— They control their emotions and impulsive desires.

- They feel good about themselves and are confident that they can cope with life's difficulties.

Based on my experience with clients, I can add a few more traits to this list that are characteristic of those who show resilience. Such people:

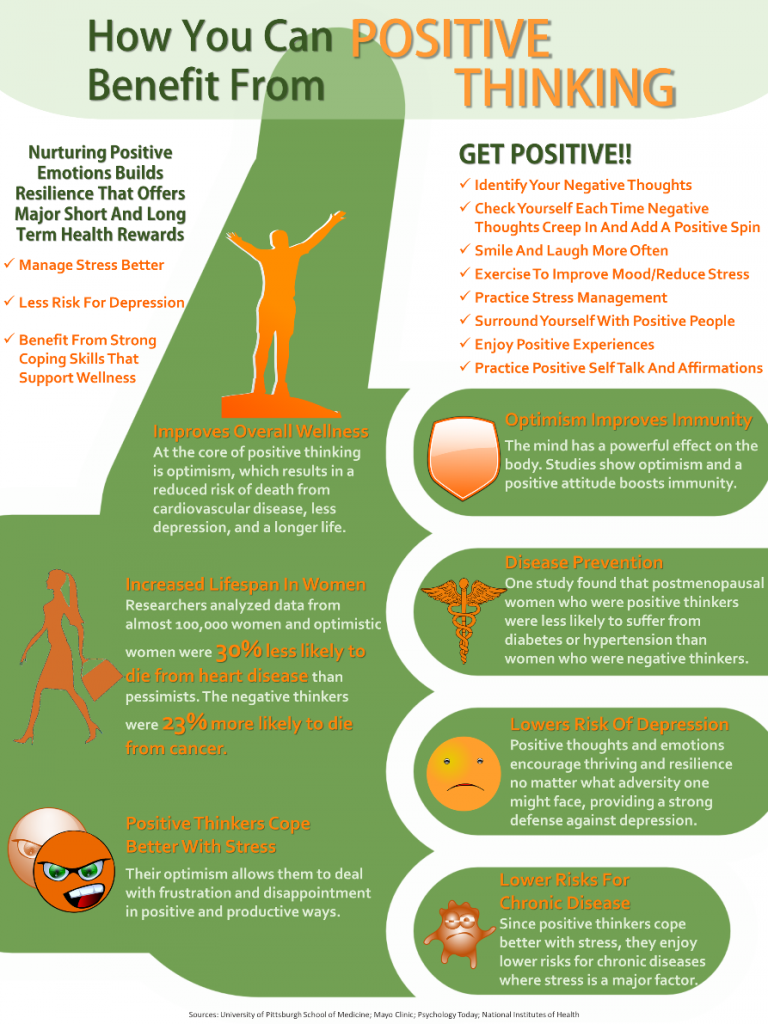

- as a rule, are generally more optimistic.

See more options and be more resourceful.

- recognize that change is an integral part of life and that things don't always work out as planned.

- focus on what they can really control and direct energy to change themselves.

- accept help from others.

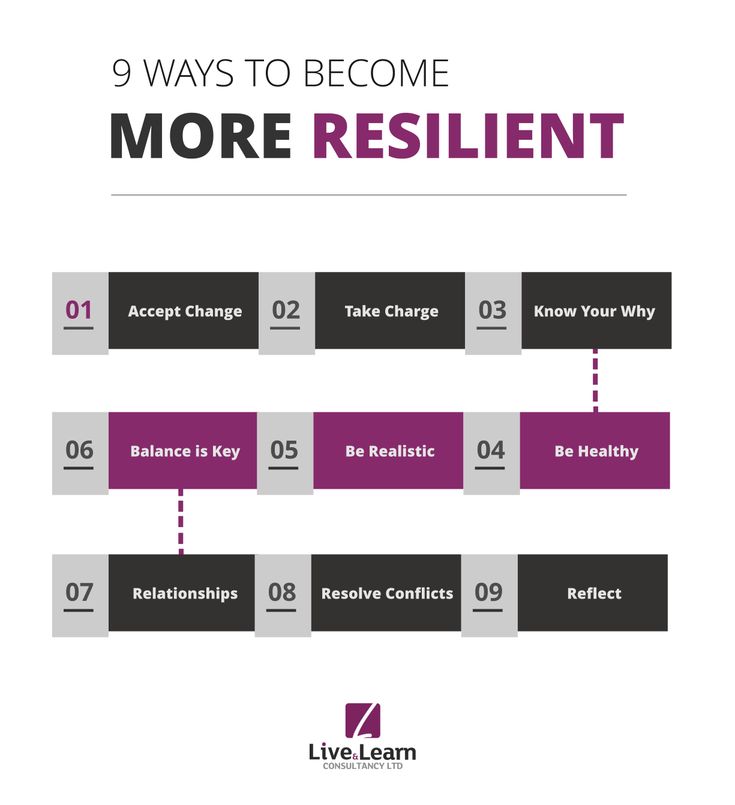

The good news is that resilience can be developed. And here's how.

1. See failure as an opportunity to grow

It is important to learn to treat failure as a valuable lesson. Remembering that black streaks in life are normal and inevitable, you can not take them as something personal - punishment or proof of your failure - and not blame yourself.

2. Create your own “support group”

Our resilience is largely due to the people who support us. Work on relationships by keeping in touch with old friends and making new ones by participating in social or religious life, various circles, sections, interest groups.

3. Don't ask why, ask how?

Very often the question of why something bad happened is simply impossible to answer. But many still engage in a fruitless search for answers and, as a result, wallow in anger, guilt, and depression. The question to really ask yourself is, “How can I deal with this?”

The question to really ask yourself is, “How can I deal with this?”

4. Control your emotions

An important component of psychological stability is the ability to control and regulate your emotions and mood. Strong experiences - anger, sadness, fear - prevent you from thinking clearly, soberly assessing the options available and making informed decisions.

Resilient people are able to control their emotions so that they do not prevent them from concentrating on business. However, they do not suppress these experiences, but find healthy means to express them. They know how to calm down and relax through creative hobbies, sports or meditation.

5. Stop feeling sorry for yourself

To be more resilient, it is important to stop thinking of yourself as a victim. Try to see yourself as a person who can cope with any difficulties. By replacing self-pity with compassion, you will understand that everyone has difficulties, and stop comparing your problems with others.

6. Remind yourself that you are stronger than you think

Resilient people do not see problems as insurmountable: they believe that they can withstand any difficulties. How successfully you overcome obstacles depends largely on how you perceive these obstacles.

My favorite confidence building exercise is to make a list of all the challenges you've already overcome. For most, it will turn out to be quite long, and it will include both real tragedies, such as the death of loved ones, and minor troubles, like a dent in a car.

Even if you dealt with past problems in less than optimal ways, you still have accumulated a wealth of experience that will tell you what is worth doing and what is not. It is very important to remember that you are actually stronger than you think.

7. Don't think about problems, think about how to solve them

Another way to increase your mental resilience is to focus not on difficulties, but on possible solutions. By endlessly “chewing” problems, you only exacerbate the situation.

By endlessly “chewing” problems, you only exacerbate the situation.

Anxiety and fruitless thinking usually do not contribute to flexible thinking and creative problem solving. If you find yourself “fixated” on overthinking things, switch to finding a solution or asking for advice from someone you trust.

8. Do not forget the humor

Can you laugh at yourself or your problems? Humor can help overcome the most difficult periods in life.

Humor has been named one of the five best ways to build resilience: laughing in the face of adversity can help you get rid of pain, both physical and mental.

9. Remember: you are not only your problems

It is important to remind yourself that your life and yourself are much bigger than your problems. You can not always control what is happening, but it depends on you how you will react.

About the author: Sharon Martin is a psychotherapist with over 20 years of experience.

Text: Nikolai Protsenko Photo Source: Getty Images

New on the site

How to speak so that your partner understands? 5 tips from psychological practice

How to cope with laziness: advice from a psychologist - take action

“A teenage son suddenly began to avoid hugs. This is fine?"

This is fine?"

4 Signs You're Not Knowing Yourself

"A Good Enough Mother": How Donald Woods Winnicott Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love Parenting - 4 Key Ideas to help children”

How to develop fortitude of character? – Success Constructor

Different people behave differently in the same situation. Faced with troubles, one will worry for a long time and engage in self-flagellation, while the second will shake himself off, pull himself together and move on. This is the fortitude of character, which helps its owner to quickly cope with failures and achieve great success in life.

Fortitude is an important property that should not be underestimated. It happens that a talented and intelligent person remains out of work only because he could not cope with himself in time, was afraid of difficulties, did not want to face unpleasant situations again.

To fulfill your dreams, you will have to take on the development of resilience. It will help in the fight against one's own laziness, and in resisting the psychological attacks of ill-wishers, and will increase resistance to stress. Sometimes we can be morally crippled by banal criticism of the authorities or our own mistake in important calculations. Knowing how to develop resilience, we can stay on the horse of success, if he wants to kick.

Sometimes we can be morally crippled by banal criticism of the authorities or our own mistake in important calculations. Knowing how to develop resilience, we can stay on the horse of success, if he wants to kick.

- Learn from failure. To achieve success and reach a new level, you need to be prepared for the fact that you first have to overcome an obstacle course. It is inevitable - you will try, make mistakes, correct them and thus learn. Failure is not a tragedy, and development does not end with it. On the contrary, failure is an important element of learning and personal growth. If you treat your mistakes correctly, analyze them and try not to repeat them, then your experience will be useful.

- Man makes mistakes because he is a man. Everyone makes mistakes, even super-accurate programs are subject to this. And people are even more prone to mistakes - our psyche is designed to protect itself from overload. Therefore, when processing a large flow of information, we can forget, confuse or do something wrong.

This is normal, and by keeping this in mind, you won't get stuck in self-examination after every mistake. I made a mistake - I'll fix it.

This is normal, and by keeping this in mind, you won't get stuck in self-examination after every mistake. I made a mistake - I'll fix it. - Don't forget about your friends. Close people and friends are our moral support and a source of positive. When everything is tired and it seems that all the work is going to hell - get together with friends, talk about something pleasant, have fun as it should. It can also be useful to discuss your problem with a friend over a glass of tea - sometimes the very pronunciation helps to find a way out. And two heads are better than one.

- Emotions - under control. When emotions are overwhelming, it is impossible to make a sound decision or focus on a painstaking process. Emotions must be controlled, otherwise they will control you. To develop resilience, you need to learn how to deal with anger, discouragement, confusion, and even joy and love. Yes, and they can harm us like sweets, if you don't know the measure. To control emotions, there are techniques, meditations, rules that you need to forbid yourself to break.

For example, never make an important decision in a moment of despondency or anger. Controlling emotions is an important aspect of resilience, and this, in turn, is necessary for developing a strong character. After all, all the key events of our lives are accompanied by stress, even pleasant ones. To know how to cope with stress, study this question and find the ways that are most suitable for you. There are a lot of them, so we will not go deep - this is a separate topic.

For example, never make an important decision in a moment of despondency or anger. Controlling emotions is an important aspect of resilience, and this, in turn, is necessary for developing a strong character. After all, all the key events of our lives are accompanied by stress, even pleasant ones. To know how to cope with stress, study this question and find the ways that are most suitable for you. There are a lot of them, so we will not go deep - this is a separate topic. - Stop complaining. Speaking about something, we give this phenomenon power, we materialize repetitions of negative or positive scenarios. Is it magic? No, ordinary psychology. The more we talk, the more we obsess, the more we attract into our lives. You should not discuss your experiences with everyone in a row - people don’t need them, they have plenty of their own “cockroaches”. You need to try to abstract, distract from your suffering, keep yourself busy with work or look for positive emotions in something new.

By complaining, you are spinning yourself into a tight roll of depression, and the more you feel sorry for yourself, the more coils this roll has. And by the way, no one likes whiners.

By complaining, you are spinning yourself into a tight roll of depression, and the more you feel sorry for yourself, the more coils this roll has. And by the way, no one likes whiners. - It doesn't matter why it happened. Seriously. If the event has already happened, then there is no need to blame the indirectly involved forces, events and people in it. This is a waste and a waste of energy and precious time. First of all, you need to find a solution, and already in the second ... However, no - neither second nor last, you should not look for hidden meanings, complain about injustice and curse the heavens. There is no sense in this. All resources should be thrown to correct the situation.

- "Man is capable of more than we think." This phrase is in quotation marks, because I often repeat it when it seems that that's it, it's time to turn the sails and give in to circumstances - there is no more strength left. At times like these, it’s good to remember people who didn’t give up in much more difficult situations.