The history of asylums

From sanctuary to snake pit: the rise and fall of asylums

Most people associate the word “asylum” with squalor and brutality – an impression strengthened by portrayals in books and films like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – but they were originally designed to be places of sanctuary. Christopher Payne visited and photographed 70 such institutions across the US for his book Asylum: Inside the closed world of state mental hospitals, which documents how their fall from grace reflects changing attitudes to mental illness

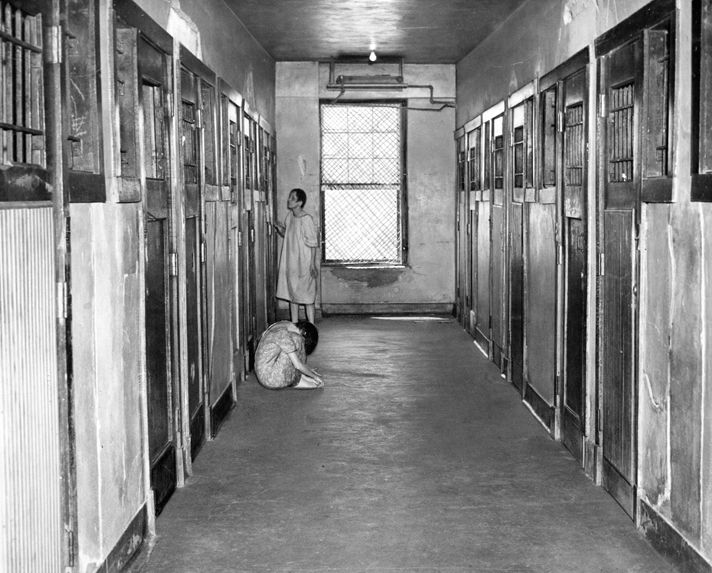

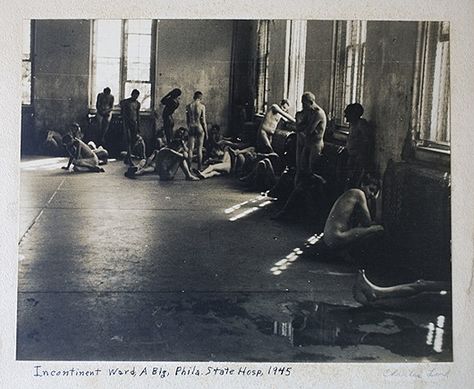

Mental institutions have a bad reputation. Many people think of them as little more than prisons for the insane, their populations of violent or stupefied patients forcibly confined to dismal wards ruled over by tyrannical matrons. There's some truth in that: this picture shows Matteawan State Hospital in Beacon, New York – which is now Fishkill Correctional Facility.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

In the foreword of Christopher Payne's book Asylum: Inside the closed world of state mental hospitals, the neurologist Oliver Sacks says that we tend to think of asylums as "snake pits, hells of chaos and misery, squalor and brutality" – places that no one would stay in voluntarily. These straitjackets were used to restrain and pacify patients at the North Dakota State Hospital in Jamestown.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

But asylums started out as philanthopic dreams, rather than psychiatric nightmares. The concept was born in the mid-1800s, when socially minded citizens, dismayed by the often dismal lot of the mentally unstable, paid for dozens of institutions to be constructed for their care. By 1880, 139 had been built in the US.

These were often palatial buildings, designed by prestigious architects, with vast landscaped grounds and impressive vistas. They were symbols of civic pride, just as museums and universities are today, and some became fixtures on the tourist trail. This vintage postcard shows part of the extensive gardens of Danvers State Hospital in Massachusetts.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

The intention was for the asylums to be places of refuge – sanctuaries where patients' disorders were recognised and allowed for. Their founders hoped that the mentally ill could be cured by providing them with a calming environment, fresh air, a varied diet, exercise and jobs in the asylum's workshops or farm – an approach known as "moral treatment". This is the sweeping marble staircase in the lobby at Yankton State Hospital in South Dakota.

Their founders hoped that the mentally ill could be cured by providing them with a calming environment, fresh air, a varied diet, exercise and jobs in the asylum's workshops or farm – an approach known as "moral treatment". This is the sweeping marble staircase in the lobby at Yankton State Hospital in South Dakota.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

Unfortunately, moral treatment didn't prove very effective. Rather than being cured and leaving, residents tended to remain in the asylum for the duration of their lives, even as more continually arrived.

By the end of the 19th century, some asylums had many thousands of residents and had become more like miniature towns, complete with the appropriate utilities and recreational facilities. These bowling shoes were photographed at Rockland State Hospital in New York.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

Residents at these huge institutions could also visit theatres and cafés, as well as beauty salons like this one at Trenton State Hospital in New Jersey.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

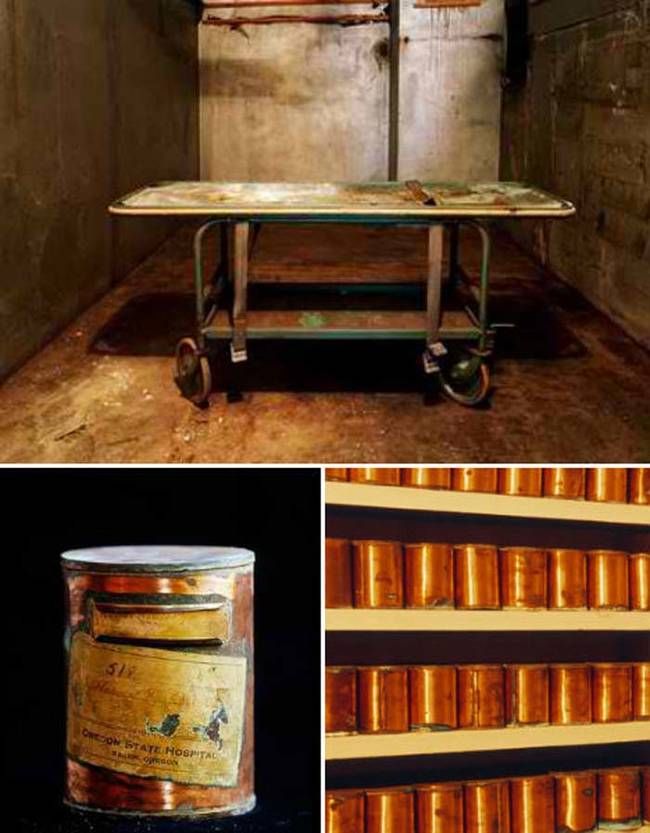

Asylums even cared for residents after their deaths. Patients might be buried in the asylum's graveyard, or their remains stored for collection by next of kin – although that sometimes never happened. This picture shows rows of unclaimed copper cremation urns at Oregon State Hospital. (You can see David Maisel's stunning close-up photographs of these canisters in this New Scientist gallery.)

(This image: Christopher Payne)

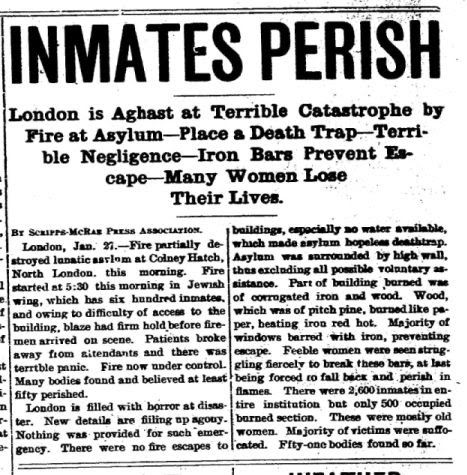

As time went on, however, state funding dwindled, and so did the number of qualified staff. The benevolent philanthropists' dream began to crumble, with the institutions gradually becoming "bywords for squalor and negligence, and often run by inept, corrupt or sadistic bureaucrats", writes Sacks.

This is the view through the observation window from the seclusion room at Middletown State Hospital in New York.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

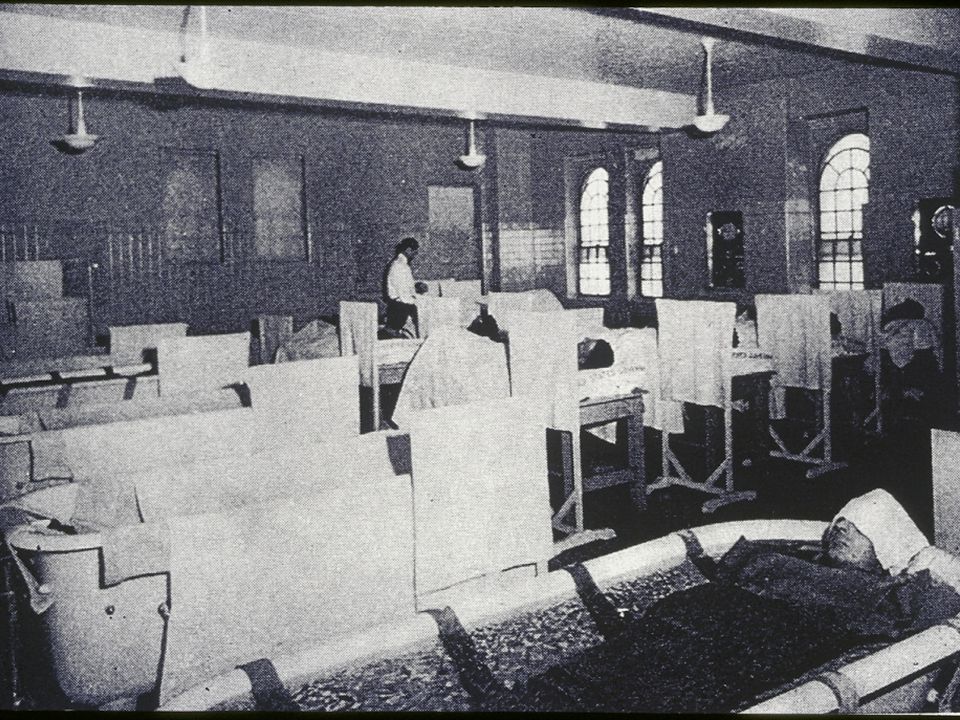

By the beginning of the 20th century the "moral treatment" philosophy was essentially dead, to be replaced by more invasive therapies. For example, in insulin shock therapy, an early treatment for schizophrenia, patients were put into a coma induced by injections of large doses of insulin every day for weeks.

For example, in insulin shock therapy, an early treatment for schizophrenia, patients were put into a coma induced by injections of large doses of insulin every day for weeks.

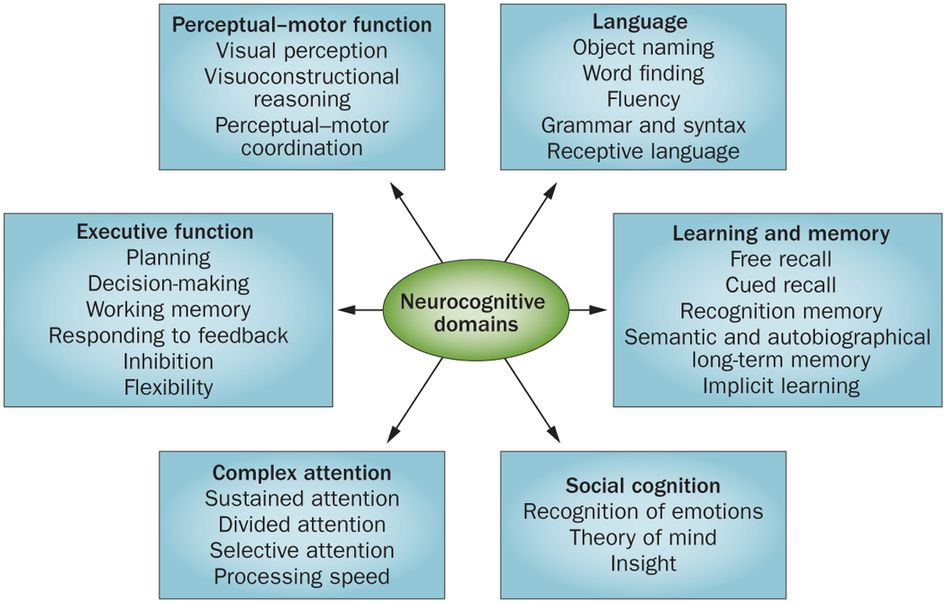

Another approach was psychosurgery. Lobotomy consisted of cutting connections to and from the prefrontal cortex of the brain, the region responsible for everyday decisions, language, memory, socialising and spontaneity. As a result, lobotomised people underwent drastic personality changes. It was widely used between the 1930s and 1950s to treat a wide range of severe disorders, including schizophrenia and clinical depression.

This is an electroencephalograph used to observe patients' brain activity at Clarinda State Hospital in Iowa.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

The most notorious of the new therapies was electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), introduced in the 1930s. ECT involves electrically inducing seizures in anaesthetised patients using machines like this one at Lincoln State Hospital in Nebraska. The treatment has been portrayed as barbaric but is still used to treat some conditions, such as severe depression.

The treatment has been portrayed as barbaric but is still used to treat some conditions, such as severe depression.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

The 1950s brought the advent of antipsychotic drugs such as Thorazine, which suppressed the symptoms of mental disorders, raising hopes that sufferers might be able to lead relatively normal lives beyond the asylum walls.

This was a welcome development for the cash-strapped asylums. A 1948 survey showed that a quarter of New York's state budget was going to the hospitals, and by the mid-1960s the US government had started to opt for community care of the mentally ill. New mental health centres were set up, designed to administer the short-term treatments made possible by the new drugs.

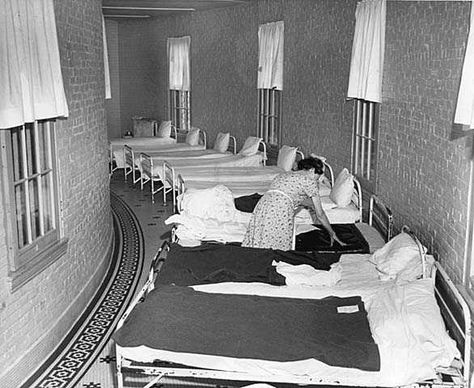

This is a photograph of a typical ward of the now outmoded asylums, a corridor with bedrooms branching off it, at Buffalo State Hospital in New York. It was euphemistically rebranded as a state hospital at the turn of the century.:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8109851/unspecified.jpg)

(Image: Christopher Payne)

Care in the community offered the remaining state hospitals relief from their financial pressures, but these were renewed in the 1970s, when laws were passed establishing minimum standards of care and barring patients from working. These measures were intended to protect patients' rights, but the cost of complying with them was staggering. Vast areas of land were sold to raise funds and the institutions started to decay.

Patients who could not be treated in accordance with the new standards were simply released. Those who remained found themselves directionless, sometimes becoming the TV-addict zombies of popular imagination.

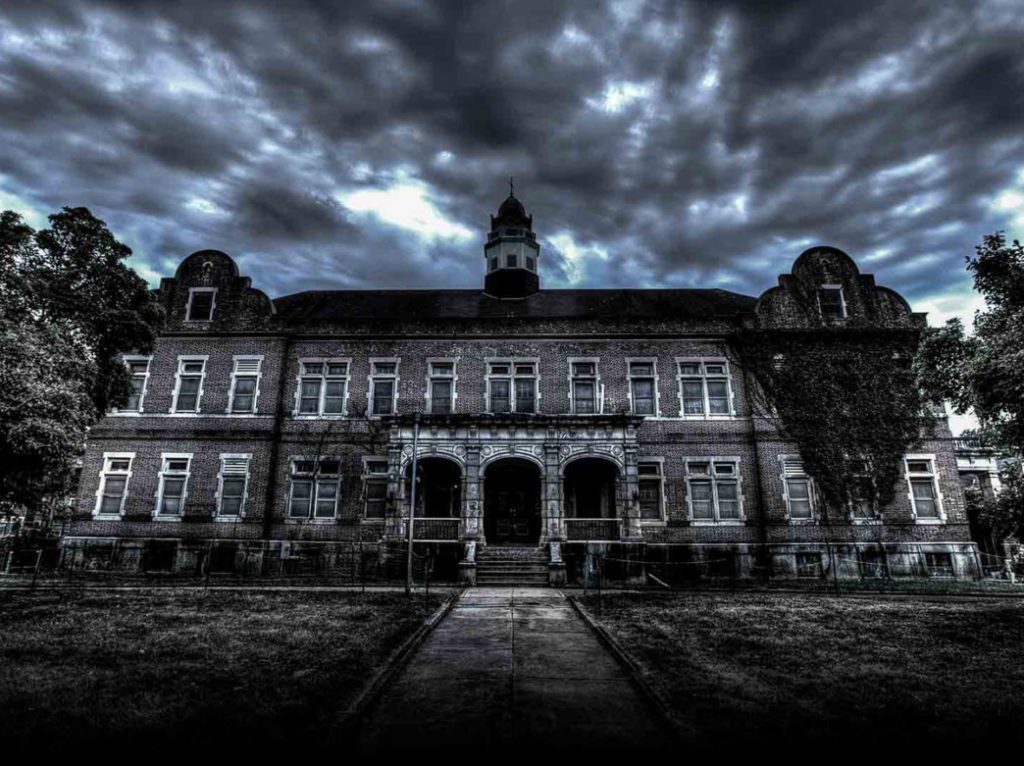

The Norwich State Hospital, Connecticut, was closed in 1996. Although its windows are boarded up, its national architectural and historical significance mean that its buildings can't be torn down.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

By the 1980s, deinstitutionalisation was in full swing, with patients being returned to their communities in large numbers. The remaining institutions were shut down, with their grounds sold off and buildings demolished.

The remaining institutions were shut down, with their grounds sold off and buildings demolished.

But by the 1990s it became clear that the rapid closing of the asylums had been a mistake. Not enough clinics and half-way houses had been set up to ease the transition, and the community care centres were struggling to cope.

This picture shows Danvers State Hospital, which closed in 1992 but where demolition only began in 2005. There was public outcry at the destruction of its Gothic architecture, which is said to have inspired the fictional Arkham Asylum of the Batman comics.

(Image: Christopher Payne)

The photographer of these images, Christopher Payne, says there are now signs that the mental health system is returning to a more balanced approach: "Cognitive behavioural therapy and other cognitive therapies are receiving greater attention, although there are still lots of doctors happy to follow a largely pharmaceutical approach," he says.

"It's unlikely that asylums in their benevolent guise will ever be a common feature in our towns again, as the process of deinstitutionalisation is too far along to be reversed. There are too many rules and regulations in place and not enough money to see a return to the old kind of 'moral therapy'."

There are too many rules and regulations in place and not enough money to see a return to the old kind of 'moral therapy'."

"The best we can hope for is vocational training in modern rehab centres, or art therapy as practised at Creedmoor Psychiatric Centre's Living Museum in New York." (pictured)

(Image: Christopher Payne)

History of Psychiatric Hospitals • Nursing, History, and Health Care • Penn Nursing

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The history of psychiatric hospitals was once tied tightly to that of all American hospitals. Those who supported the creation of the first early-eighteenth-century public and private hospitals recognized that one important mission would be the care and treatment of those with severe symptoms of mental illnesses. Like most physically sick men and women, such individuals remained with their families and received treatment in their homes. Their communities showed significant tolerance for what they saw as strange thoughts and behaviors. But some such individuals seemed too violent or disruptive to remain at home or in their communities. In East Coast cities, both public almshouses and private hospitals set aside separate wards for the mentally ill. Private hospitals, in fact, depended on the money paid by wealthier families to care for their mentally ill husbands, wives, sons, and daughters to support their main charitable mission of caring for the physically sick poor.

But some such individuals seemed too violent or disruptive to remain at home or in their communities. In East Coast cities, both public almshouses and private hospitals set aside separate wards for the mentally ill. Private hospitals, in fact, depended on the money paid by wealthier families to care for their mentally ill husbands, wives, sons, and daughters to support their main charitable mission of caring for the physically sick poor.

But the opening decades of the nineteenth-century brought to the United States new European ideas about the care and treatment of the mentally ill. These ideas, soon to be called “moral treatment,” promised a cure for mental illnesses to those who sought treatment in a very new kind of institution—an “asylum.” The moral treatment of the insane was built on the assumption that those suffering from mental illness could find their way to recovery and an eventual cure if treated kindly and in ways that appealed to the parts of their minds that remained rational. It repudiated the use of harsh restraints and long periods of isolation that had been used to manage the most destructive behaviors of mentally ill individuals. It depended instead on specially constructed hospitals that provided quiet, secluded, and peaceful country settings; opportunities for meaningful work and recreation; a system of privileges and rewards for rational behaviors; and gentler kinds of restraints used for shorter periods.

It repudiated the use of harsh restraints and long periods of isolation that had been used to manage the most destructive behaviors of mentally ill individuals. It depended instead on specially constructed hospitals that provided quiet, secluded, and peaceful country settings; opportunities for meaningful work and recreation; a system of privileges and rewards for rational behaviors; and gentler kinds of restraints used for shorter periods.

Many of the more prestigious private hospitals tried to implement some parts of moral treatment on the wards that held mentally ill patients. But the Friends Asylum, established by Philadelphia’s Quaker community in 1814, was the first institution specially built to implement the full program of moral treatment. The Friends Asylum remained unique in that it was run by a lay staff rather than by medical men and women. The private institutions that quickly followed, by contrast, chose physicians as administrators. But they all chose quiet and secluded sites for these new hospitals to which they would transfer their insane patients. Massachusetts General Hospital built the McLean Hospital outside of Boston in 1811; the New York Hospital built the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in Morningside Heights in upper Manhattan in 1816; and the Pennsylvania Hospital established the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital across the river from the city in 1841. Thomas Kirkbride, the influential medical superintendent of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, developed what quickly became known as the “Kirkbride Plan” for how hospitals devoted to moral treatment should be built and organized. This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

But they all chose quiet and secluded sites for these new hospitals to which they would transfer their insane patients. Massachusetts General Hospital built the McLean Hospital outside of Boston in 1811; the New York Hospital built the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in Morningside Heights in upper Manhattan in 1816; and the Pennsylvania Hospital established the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital across the river from the city in 1841. Thomas Kirkbride, the influential medical superintendent of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, developed what quickly became known as the “Kirkbride Plan” for how hospitals devoted to moral treatment should be built and organized. This plan, the prototype for many future private and public insane asylums, called for no more than 250 patients living in a building with a central core and long, rambling wings arranged to provide sunshine and fresh air as well as privacy and comfort.

Occupational Therapy Group, Philadelphia Hospital for Mental Diseases, Thirty-fourth and Pine StreetsWith both the ideas and the structures established, reformers throughout the United States urged that the treatment available to those who could afford private care now be provided to poorer insane men and women. Dorothea Dix, a New England school teacher, became the most prominent voice and the most visible presence in this campaign. Dix travelled throughout the country in the 1850s and 1860s testifying in state after state about the plight of their mentally ill citizens and the cures that a newly created state asylum, built along the Kirkbride plan and practicing moral treatment, promised. By the 1870s virtually all states had one or more such asylums funded by state tax dollars.

Dorothea Dix, a New England school teacher, became the most prominent voice and the most visible presence in this campaign. Dix travelled throughout the country in the 1850s and 1860s testifying in state after state about the plight of their mentally ill citizens and the cures that a newly created state asylum, built along the Kirkbride plan and practicing moral treatment, promised. By the 1870s virtually all states had one or more such asylums funded by state tax dollars.

By the 1890s, however, these institutions were all under siege. Economic considerations played a substantial role in this assault. Local governments could avoid the costs of caring for the elderly residents in almshouses or public hospitals by redefining what was then termed “senility” as a psychiatric problem and sending these men and women to state-supported asylums. Not surprisingly, the numbers of patients in the asylums grew exponentially, well beyond both available capacity and the willingness of states to provide the financial resources necessary to provide acceptable care. But therapeutic considerations also played a role. The promise of moral treatment confronted the reality that many patients, particularly if they experienced some form of dementia, either could not or did not respond when placed in an asylum environment.

But therapeutic considerations also played a role. The promise of moral treatment confronted the reality that many patients, particularly if they experienced some form of dementia, either could not or did not respond when placed in an asylum environment.

Philadelphia Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia, PA c. 1900The medical superintendents of asylums took such critiques seriously. Their most significant effort to improve the quality of the care of their patients was the establishment of nurses’ training schools within their institutions. Nurses’ training schools, first established in American general hospitals in the 1860s and 1870s, had already proved critical to the success of these particular hospitals, and asylum superintendents hoped they would do the same for their institutions. These administrators took an unusual step. Rather than following an accepted European model in which those who trained as nurses in psychiatric institutions sat for a separate credentialing exam and carried a different title, they insisted that all nurses who trained in their psychiatric institutions sit for the same exam as those who trained in general hospitals and carry the same title of “registered nurse. ” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses. But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

” Leaders of the nascent American Nurses Association fought hard to prevent this, arguing that those who trained in asylums lacked the necessary medical, surgical, and obstetric experiences common to general-hospital-trained nurses. But they could not prevail politically. It would be decades before American nursing leaders had the necessary social and political weight to ensure that all training school graduates—irrespective of the site of their training—had comparable clinical and classroom experiences.

Byberry State Hospital, Philadelphia, PA c. 1920It is, at present, hard to assess the impact of nurses’ training schools on the actual care of patients in psychiatric institutions. In some larger public institutions, the students worked only on particular wards. It does seem that they had a more substantive impact on the care of patients in much smaller and private psychiatric hospitals where they had more contact with more patients. Still, it may be that their most enduring contribution was opening the practice of professional nursing to men. Training schools in asylums, unlike those in general hospitals, actively welcomed men. Male students found places either in schools that also accepted women or in separate schools formed just for them.

Training schools in asylums, unlike those in general hospitals, actively welcomed men. Male students found places either in schools that also accepted women or in separate schools formed just for them.

Training schools for nurses, however, could not stop the assault on psychiatric asylums. The economic crisis of the 1930s drastically cut state appropriations, and World War II created acute shortages of personnel. Psychiatrists, themselves, began looking for other practice opportunities by more closely identifying with general, more reductionistic, medicine. Some established separate programs—often called “psychopathic hospitals”—within general hospitals to treat patients suffering from acute mental illnesses. Others turned to the early-twentieth-century’s new Mental Hygiene Movement and created outpatient clinics and new forms of private practice focused on actively preventing the disorders that might result in a psychiatric hospitalization. And still others experimented with new forms of therapies that posited brain pathology as a cause of mental illness in the same way that medical doctors posited pathology in other body organs as the cause of physical symptoms: they tried insulin and electric shock therapies, psychosurgery, and different kinds of medications.

By the 1950s, the death knell for psychiatric asylums had sounded. A new system of nursing homes would meet the needs of vulnerable elders. A new medication, chlorpromazine, offered hopes of curing the most persistent and severe psychiatric symptoms. And a new system of mental health care, the community mental health system, would return those suffering from mental illnesses to their families and their communities.

Today, only a small number of the historic public and private psychiatric hospitals exist. Psychiatric care and treatment are now delivered through a web of services including crisis services, short-term and general-hospital-based acute psychiatric care units, and outpatient services ranging from twenty-four-hour assisted living environments to clinics and clinicians’ offices offering a range of psychopharmacological and psychotherapeutic treatments. The quality and availability of these outpatient services vary widely, leading some historians and policy experts to wonder if “asylums,” in the true sense of the word, might be still needed for the most vulnerable individuals who need supportive living environments.

Patricia D’Antonio is Carol E. Ware Professor in Mental Health Nursing, Chair, Department of Family and Community Health, Director, Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, and Senior Fellow, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

A bit of history

« Love for animals is an aesthetic feeling.

The loss of this love is tantamount to the loss of happiness

and adversely affects the mental abilities

and the moral principles of a person.

KG Paustovsky

August 16 - International Day for the Protection of Homeless Animals. This day is celebrated at the initiative of the International Society for Animal Rights - ISAR, USA. At 1992 ISAR came up with a proposal to mark every third Saturday in August as National Homeless Animal Day. The initiative was supported by animal protection organizations from different countries, and soon August 16 was declared the International Day for the Protection of Homeless Animals.

The initiative was supported by animal protection organizations from different countries, and soon August 16 was declared the International Day for the Protection of Homeless Animals.

Peter Scott, founder of WWF (World Wildlife Fund) has become the motto of many animal relief communities: who didn't even try. nine0024

According to statistics, about 75% of stray dogs and cats were once pets. Through the fault of soulless owners, they find themselves on the street without having the skills necessary to survive in such an environment. Abandoned animals have little chance of life.

Therefore, on International Homeless Animal Day (and not only on this day), please do not pass by crying kittens and whining puppies, past dogs and cats looking into your eyes. After all, it is at this moment that their fate is in your hands. And everyone can help them. A person can shelter an animal for a while or find a temporary place for him to live; place an ad looking for hosts on the Internet, for example; donate food and medicine to animal protection organizations; help them financially or distribute animal announcements, etc. nine0005

nine0005

The world's first known dog shelter appeared in Japan near the city of Edo (now Tokyo) in 1695 at the initiative of the feudal ruler Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, known by the nickname "Inukobo", or "Dog Shogun". In the nursery for 50,000 heads, the animals received three meals a day, they had to be addressed with respect and called “master” or “lady”. 270 employees of the shelter were obliged to please the dogs in every possible way, to ensure that they did not get into a fight with each other. For two hours after dinner, the dogs were lectured on Confucianism. nine0005

In 1822, the first law to protect animals from cruelty was passed in Great Britain. Soon animal protection laws were adopted in most European countries. In the UK, the first officially registered shelter for abandoned and starving cats was founded in 1885 in Dublin.

Not all of the existing shelters have their own premises - their volunteers keep the animals at home while they look for new owners. In Liverpool, any dog that is on the street or in city parks without an owner is caught and placed in the shelter of the Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA), where it will be kept for up to 7 days. If the owner is found, the dog will be returned to him after payment for catching and keeping in the shelter. nine0005

In Liverpool, any dog that is on the street or in city parks without an owner is caught and placed in the shelter of the Royal Society for the Protection of Animals (RSPCA), where it will be kept for up to 7 days. If the owner is found, the dog will be returned to him after payment for catching and keeping in the shelter. nine0005

The first shelter for stray dogs in Russia was established by Emperor Paul I in the Mikhailovsky Castle. One of the rescued stray dogs lived directly in the chambers of the Empress. The Russian Society for the Protection of Animals was created by Russian nobles under the patronage of Emperor Alexander II.

This was caused by numerous cases of ugly attitude towards horses on the part of cabbies. However, the main goal was to achieve humane treatment of all animals.

Under the influence of the Society, the "Rules for the treatment of animals" were approved by the Ministry of the Interior. Clause 8 stated: "In general, any torture of any animals and any cruel treatment of them is prohibited. " Under the influence of the Society in the Russian Empire, laws were adopted to restrict hunting. Shelters and hospitals for sick homeless animals were created. The police were instructed to assist anyone who presented the Society's identity card. The policemen were given awards for "zealous implementation of the rules and laws on the treatment of animals" (for example, guard Supolnikov, who saved a dog drowning in the Moscow River, was awarded a medal and a cash prize). nine0005

" Under the influence of the Society in the Russian Empire, laws were adopted to restrict hunting. Shelters and hospitals for sick homeless animals were created. The police were instructed to assist anyone who presented the Society's identity card. The policemen were given awards for "zealous implementation of the rules and laws on the treatment of animals" (for example, guard Supolnikov, who saved a dog drowning in the Moscow River, was awarded a medal and a cash prize). nine0005

His Serene Highness Prince Alexander Arkadyevich Suvorov (grandson of the famous commander) was the first Chairman of the Society. The idea of creating the Society belonged to P.V. Zhukovsky, vowel of the St. Petersburg Duma. The founder of the Society was Fyodor Khristianovich Pauli. The highest patrons of the Society were Emperors Alexander II, Alexander III, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. The society had branches in various provincial cities. Metropolitan of Kyiv and Galicia Ioanniky became an honorary member of the Kyiv department. The Society worked closely with representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church. At 19On the 15th, in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, the sermon "Blessed is the one who has mercy on the cattle."

The Society worked closely with representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church. At 19On the 15th, in the Trinity-Sergius Lavra, the sermon "Blessed is the one who has mercy on the cattle."

In the US, the first animal shelters appeared in the 19th century. In 1883, The Capital Area Humane Society was formed in Ohio. The shelter has existed for more than a hundred years, according to 2001 data, more than 10 thousand abandoned dogs and cats pass through it every year. The main task of the shelter is to find new owners for homeless animals. The shelter staff are volunteers aged 16 and over, they serve the dogs, treat them, walk with them and check how the animals live with their new owners. nine0005

Australia's first Lost Dog Home was established in 1912 and is now the third largest shelter in the country. The dog does not have time to become a stray, being on the street. It is customary to report a lost animal to shelters and volunteers immediately come to pick up the animal. Under the 1994 Pet Law, an owner has eight days to claim a found dog. The animal is under veterinary control. If a dog has serious incurable diseases that bring her suffering, she is euthanized. nine0005

Under the 1994 Pet Law, an owner has eight days to claim a found dog. The animal is under veterinary control. If a dog has serious incurable diseases that bring her suffering, she is euthanized. nine0005

On May 27, 2004, one of the most progressive animal protection laws in Europe was passed by the Austrian Parliament. Under this law, keeping chickens in cramped cages, cutting off dogs' tails and ears, using lions and other wild animals in circuses, keeping dogs on chains, and keeping puppies and kittens in the stuffy windows of pet stores is considered a crime.

Germany became the first country in the world where the rights of animals have been protected by the Constitution since 2002.

New laws prohibit (and in some cases restrict) the use of animals to test cosmetics, household chemicals and medicines. nine0005

Russia's first private animal shelter was established in the Moscow region in 1990.

Website materials http://www.4erdak.ru/news/9898, http://www. calend.ru/holidays/0/0/2980/, http://nobilities.ucoz.ru, https: //ru.wikipedia.org/wiki

calend.ru/holidays/0/0/2980/, http://nobilities.ucoz.ru, https: //ru.wikipedia.org/wiki

Stories of animals from the shelter and their new owners

Dombai, 1.2 years old

Owners

Olga - product manager in residential real estate

Sergey - employee of the karting center nine0005

We chose the name "Dombai" even before we decided on a pet. We are both snowboarders, and the nickname comes from the name of a mountain village in the Caucasus, where we once cut through the snowy slopes. We immediately agreed that the dog would be from the shelter. Before the Yuna-fest exhibition in April 2018, we went through the site and spotted one black and white handsome man. But in the end they chose his fidget brother. Although, it would be more accurate to say that he himself chose us.

Dombay before and after meeting with a new family

Since childhood, Dombai has been a very sociable and kind dog - he is friends with all dogs on the street and willingly starts playing games, raising his tail with a pipe! A very smart dog, he quickly mastered all the basic commands: sit, lie down, serve, somersault, go to work (that means go to the place). Fidget dog: the most powerful Duracell battery will envy his energy! Naturally, this caused difficulties. When we are at work, and Dombay is left alone, he turns into a little monster that crushes and gnaws everything around. In the kitchen, we have already changed the linoleum, and soon we will have to glue new wallpaper. 😄 And if we forgot to take out the trash, wait for the apocalypse when we return. But all these are trifles, which, by the way, teach us discipline and responsibility. And what happiness, having come tired from work, to find the most joyful wet nose jumping with pleasure! You immediately forget about the egg shells scattered throughout the kitchen. nine0005

Fidget dog: the most powerful Duracell battery will envy his energy! Naturally, this caused difficulties. When we are at work, and Dombay is left alone, he turns into a little monster that crushes and gnaws everything around. In the kitchen, we have already changed the linoleum, and soon we will have to glue new wallpaper. 😄 And if we forgot to take out the trash, wait for the apocalypse when we return. But all these are trifles, which, by the way, teach us discipline and responsibility. And what happiness, having come tired from work, to find the most joyful wet nose jumping with pleasure! You immediately forget about the egg shells scattered throughout the kitchen. nine0005

With the advent of Dombai, our life has changed only for the better. A dog is pure happiness and love. A friend who is always there.

We try to take Dombay to all our activities: in the summer we ride a boat and sup-surf together, go to the country house and walk in all Moscow parks. We take with us for a run along the embankment, so far only 5 kilometers, but we are striving for ten. There are no problems, he is the soul of the company and feels comfortable in any environment. Even sometimes we envy his positivity and energy. This summer we are going to go to the sea by car, and of course we will take it with us. nine0005

There are no problems, he is the soul of the company and feels comfortable in any environment. Even sometimes we envy his positivity and energy. This summer we are going to go to the sea by car, and of course we will take it with us. nine0005

Basya, 1.5 years old

Hostess

Viktoriya — specialist in consulting services

Basya did not adapt after the orphanage in principle. As soon as they got into the car, she moved from the carrier to her knees, at first purred and kissed, and then got behind the wheel. 😄 When we entered the apartment, there was a feeling that Basya had always lived here - she immediately found everything she needed. At first, she asked me to try everything, like a child. Ate strawberries, tangerines, pasta. And when I saw the broth with chicken pieces, I didn’t even understand how to eat it - it seems that you need to grab onto the meat, and there is liquid ... It was such a scream! Now she likes to take food in her paw and eat from it. For meat sticks will sell everything in the world. Every morning begins with the fact that we throw sticks to her, and she brings, then she calls me to play in the bathroom with sunbeams that appear from the mirrors when I do my morning make-up - it fascinates her. nine0005

For meat sticks will sell everything in the world. Every morning begins with the fact that we throw sticks to her, and she brings, then she calls me to play in the bathroom with sunbeams that appear from the mirrors when I do my morning make-up - it fascinates her. nine0005

Basya before and after the meeting with the owner

Everyone says that we are very similar to her. Basya is a real girl, loves flowers and manicures. As soon as he sees a nail file in his hands, he immediately sticks out his paw and lets him file his claws - he can sit like that forever. And she also loves outfits: she opens the closet and pulls out things from the shelves, and brings the most beloved in her teeth and puts them by the bed. It's like she grew up with dogs! Although Basya is already an adult, she continues to suck on the blanket like a little kitten, this is funny and cute, but everything is in saliva.

With the advent of Basya, my life was filled with fluffy tenderness. We've been together for a year now. I fell in love with her at first sight from the photo, then I waited for several weeks to pick her up, and this is a 100% hit.

I fell in love with her at first sight from the photo, then I waited for several weeks to pick her up, and this is a 100% hit.

The only negative, but fixable - my travel. We agreed with Baska that as soon as summer comes, we will start traveling together. At least let's try! So far it's difficult, because on the street she's a coward.

Basia and I wish you all furry friends!

Cooper, 1.9 years old

Owners

Oksana and Roman are entrepreneurs

My husband and children have been asking for a beagle for a long time, but I resisted for a long time, because the dog is very active and requires proper upbringing. But sometimes circumstances develop in an absolutely incredible way, and it becomes pointless to resist. Having given my husband a figurine of a dog for the New Year, I had the imprudence to put it on my desktop. I’m sitting, which means I’m working, and no, no, yes, and I’ll look into these slightly sad eyes of a Beagle dog . .. On the third day I decided to put it on a shelf in the library, otherwise I even began to clearly hear the clatter of claws on the floor. In the evening of the same day, I decided to look at the news feed before going to bed. Imagine my surprise when the first post turned out to be about that same dog. It was an announcement about a new pet in the Yuna shelter, which I already know, whose life I follow with admiration. A real gift of fate: an adult dog almost two years old, brought up and trained, raised in a large family, and besides, a Beagle boy in a reliable shelter, where there are all the specialists and even an animal psychologist! Fate - I decided, and immediately let's write, call ... In the morning, my husband was already rushing to get acquainted with his dream! 😌 He couldn’t believe it and kept calling and asking again: “Are you really going to let us have a dog?!”. nine0005

.. On the third day I decided to put it on a shelf in the library, otherwise I even began to clearly hear the clatter of claws on the floor. In the evening of the same day, I decided to look at the news feed before going to bed. Imagine my surprise when the first post turned out to be about that same dog. It was an announcement about a new pet in the Yuna shelter, which I already know, whose life I follow with admiration. A real gift of fate: an adult dog almost two years old, brought up and trained, raised in a large family, and besides, a Beagle boy in a reliable shelter, where there are all the specialists and even an animal psychologist! Fate - I decided, and immediately let's write, call ... In the morning, my husband was already rushing to get acquainted with his dream! 😌 He couldn’t believe it and kept calling and asking again: “Are you really going to let us have a dog?!”. nine0005

Cooper before and after moving to a new house

First date - 2 hours of walking, jogging, diving into a snowdrift with a good-natured plump, and the decision is made: we take it! After a week of excitement, family conversations about a new life with a dog, preparations at home for a meeting, and now we have come to pick up our foster child. I was very surprised by the center itself, built and equipped according to the most advanced European standards, and by the people who give so much love and warmth to the four-legged. My fears about the long journey of 500 kilometers were in vain. The guy behaved better than any child: calmly looked out the window and dozed off. At the only stop, I joyfully dived into the snowdrifts and jumped back into the car with pleasure. Only the youngest son did not know about the upcoming appearance of the dog in the house. It was his reaction that we all waited for, anticipating his surprise and endless joy. And so it happened! I have not seen so much delight and happiness in the eyes of the whole family for a long time. There was also an educational reason to get a pet: the eldest son took it upon himself to walk with Cooper twice for half an hour every day, and this is a whole hour of outdoor activity away from the Internet. Where there is one son, there is another. And so the friendship between the brothers grows stronger.

I was very surprised by the center itself, built and equipped according to the most advanced European standards, and by the people who give so much love and warmth to the four-legged. My fears about the long journey of 500 kilometers were in vain. The guy behaved better than any child: calmly looked out the window and dozed off. At the only stop, I joyfully dived into the snowdrifts and jumped back into the car with pleasure. Only the youngest son did not know about the upcoming appearance of the dog in the house. It was his reaction that we all waited for, anticipating his surprise and endless joy. And so it happened! I have not seen so much delight and happiness in the eyes of the whole family for a long time. There was also an educational reason to get a pet: the eldest son took it upon himself to walk with Cooper twice for half an hour every day, and this is a whole hour of outdoor activity away from the Internet. Where there is one son, there is another. And so the friendship between the brothers grows stronger.