Neurocognitive disorders symptoms

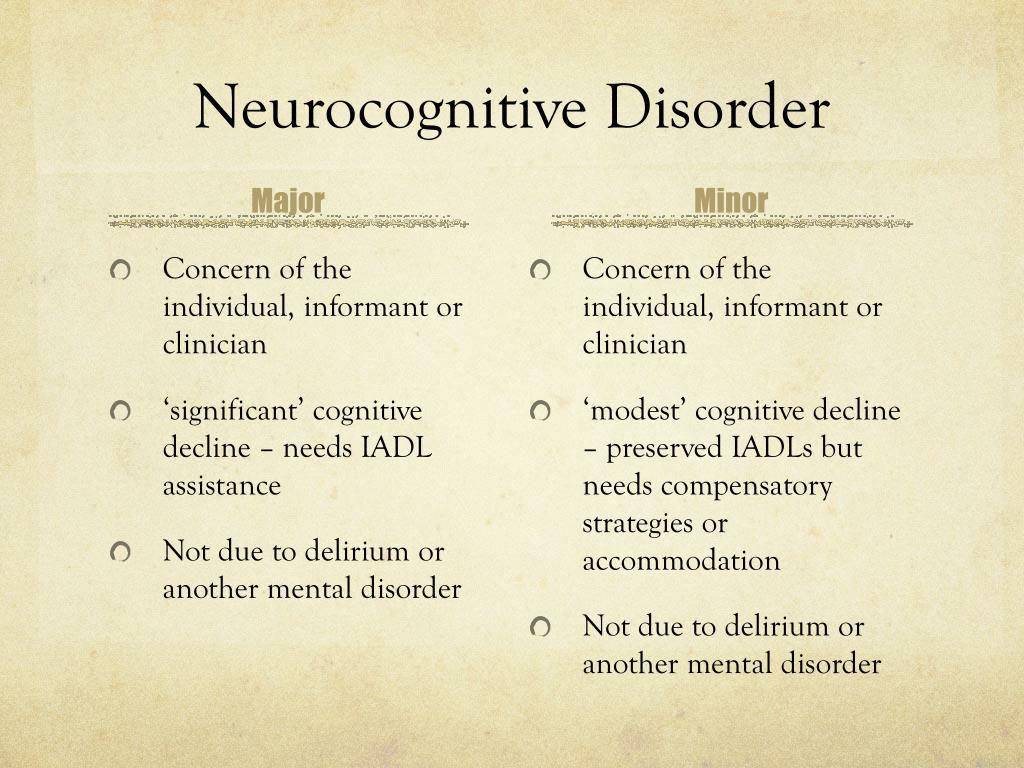

Major Neurocognitive Disorder: Signs and Symptoms

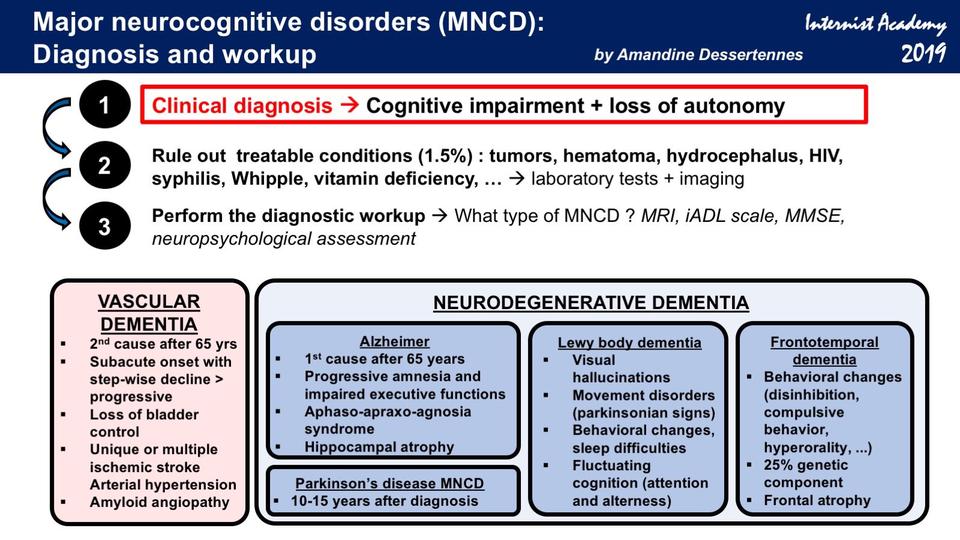

Major neurocognitive disorder — a new term for dementia — is an acquired deficit in your ability to think that’s severe enough to impact your daily functioning.

Neurocognitive disorders can lead to cognitive deficits in various domains involving attention, memory, language, or social skills, for instance.

Various medical conditions can lead to major neurocognitive disorder. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of major neurocognitive disorder.

While it’s not possible to “cure” the cognitive symptoms brought on by major neurocognitive disorder, various treatments — including medications, therapies such as skills training, and support options — can potentially slow down symptom progression.

What does neurocognitive mean?

“Neuro” is related to the nerves or nervous system, while “cognitive” relates to cognition.

In terms of major neurocognitive disorder, neurocognitive refers to an issue with how the brain functions. Neuro means that there’s a biological problem with the way the brain is functioning. Cognition is defined as thinking, or anything that the mind does to sense, organize, prepare, and perform tasks.

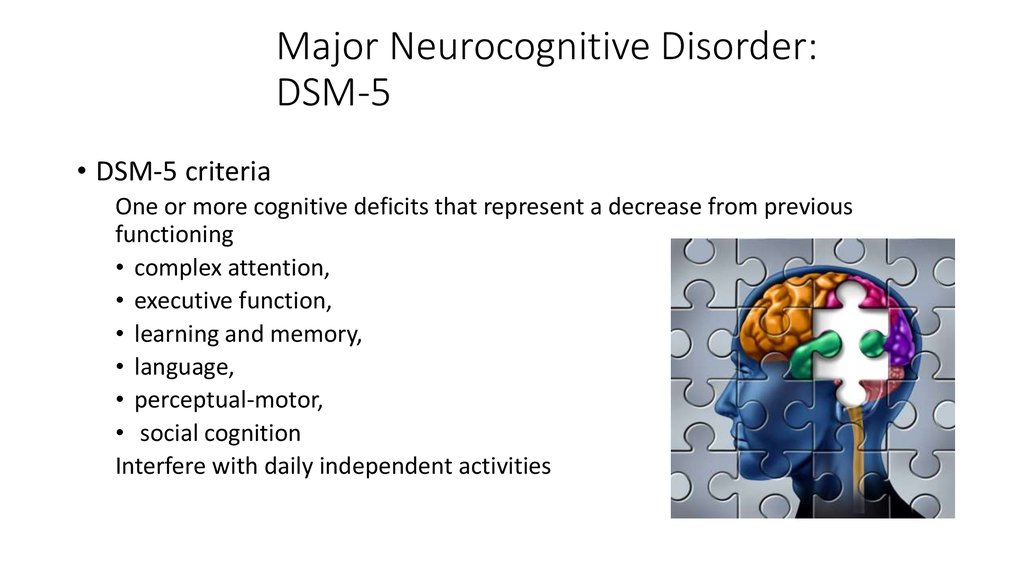

There are a variety of symptoms that may indicate major neurocognitive disorder. Some common symptoms, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), include:

- a significant decline in one or more cognitive domains, compared to your previous abilities

- the cognitive change impairs your independence in daily life, such as paying bills, managing money, or taking medications

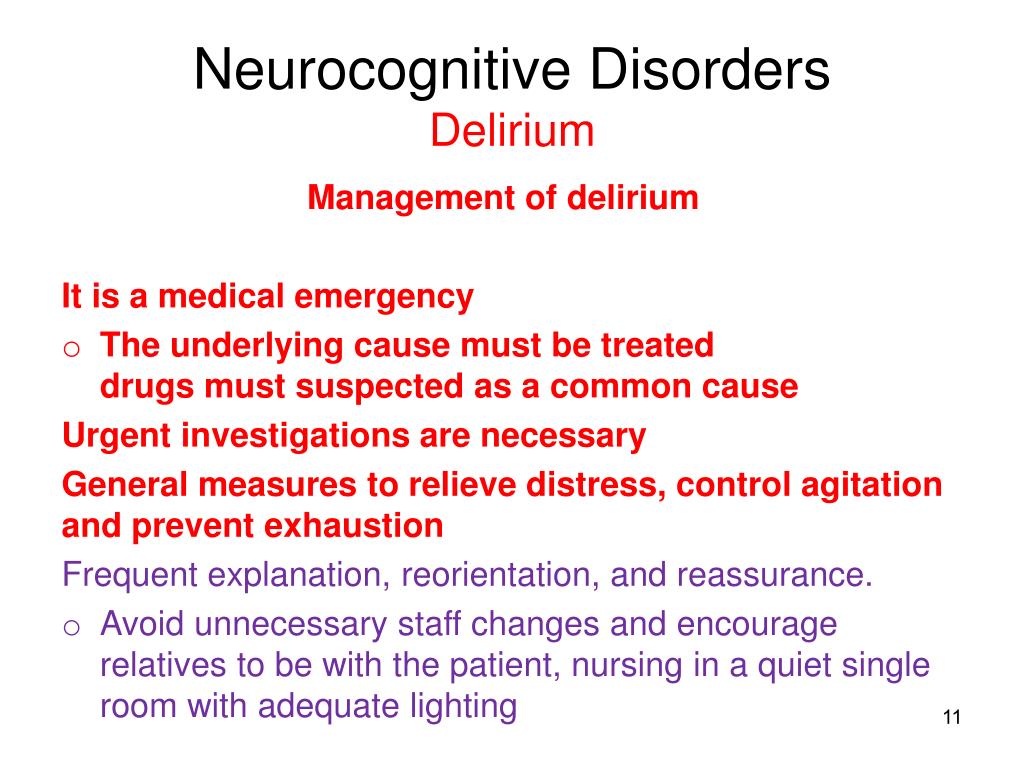

- the cognitive change does not exclusively occur as part of a delirium — a sudden state of confusion

- the cognitive decline cannot be better explained by another mental health condition

The cognitive symptoms that someone with a major neurocognitive disorder has may be reported by the person having them, someone close to them, or a medical professional.

Medical professionals can assess a person’s cognitive abilities using standardized neurological and psychological tests.

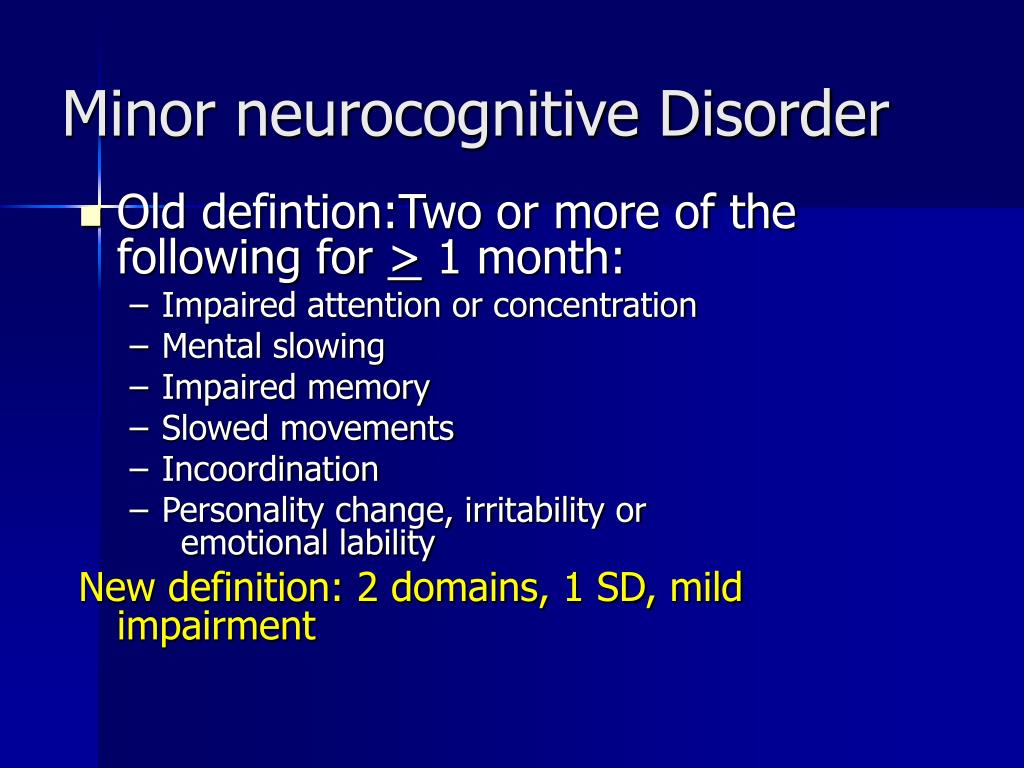

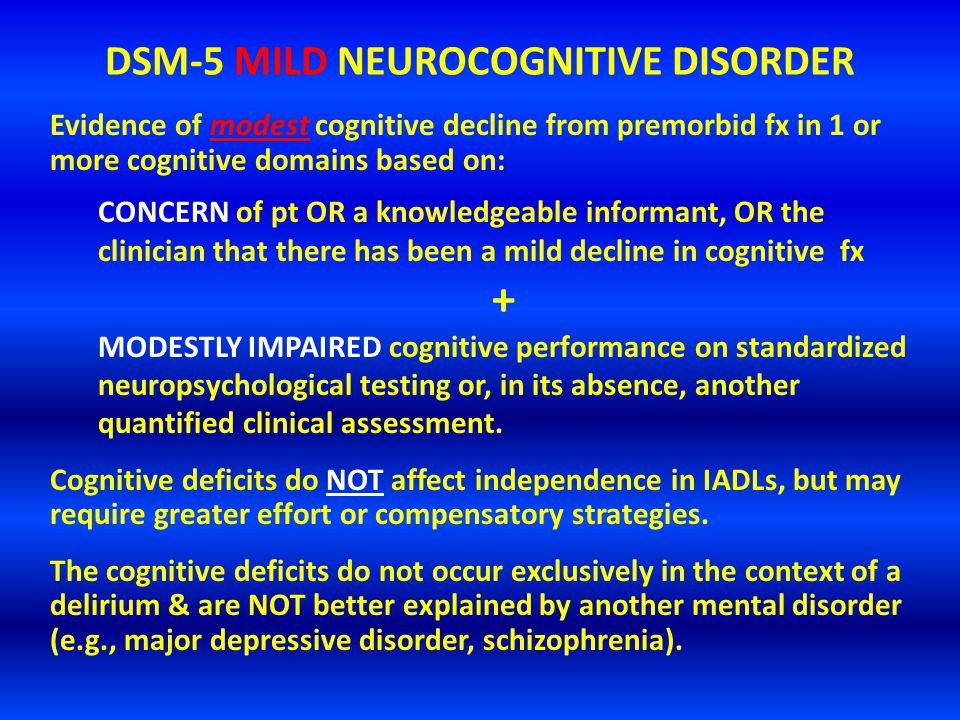

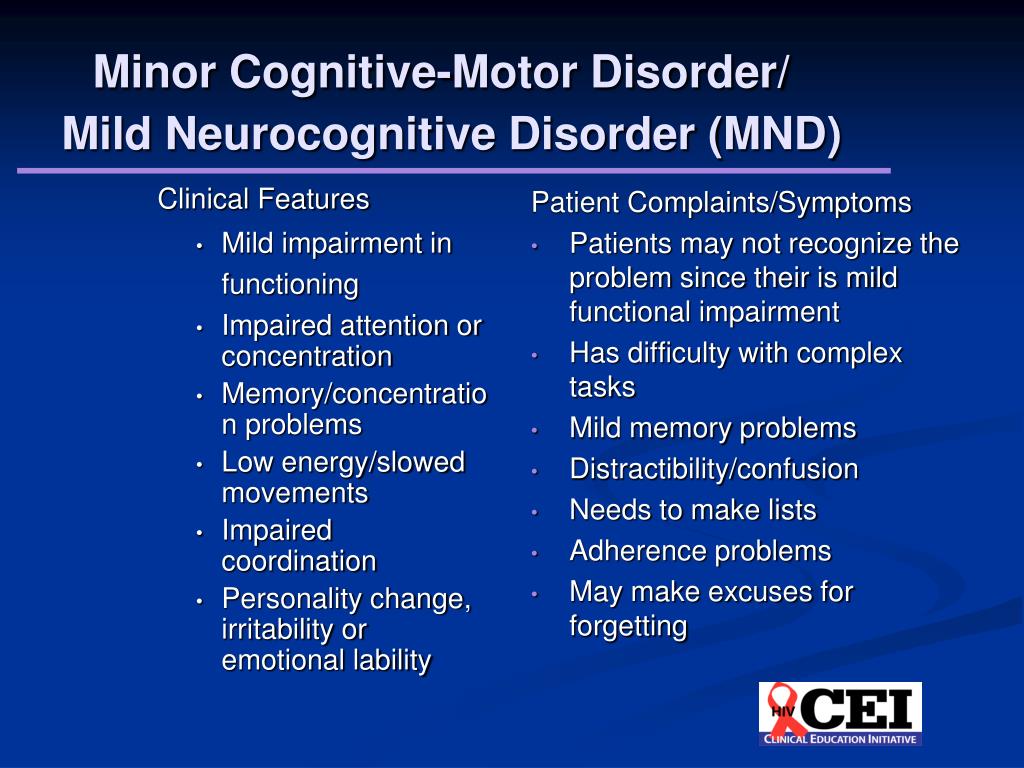

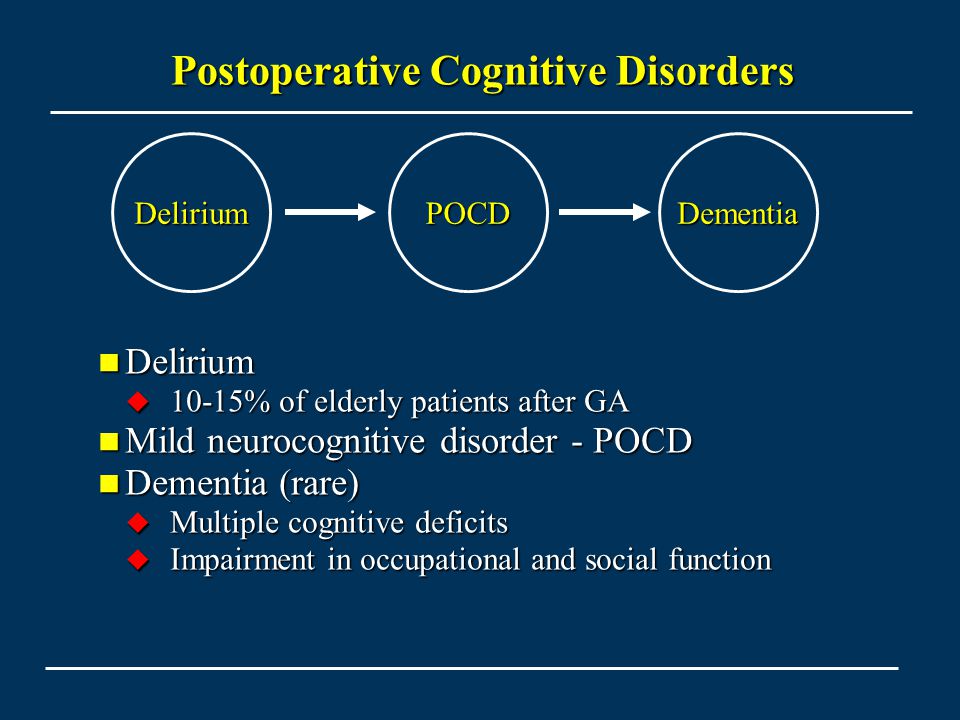

Mild neurocognitive disorder is a less severe form of major neurocognitive disorder. The difference in symptoms is that if you have a mild neurocognitive disorder, there’s only a modest cognitive decline from your previous level of performance.

If you have a mild neurocognitive disorder, you can still perform daily activities with independence. You can complete your usual complex activities, although they may require more effort than before.

The DSM-5 discusses groups of symptoms that individuals with major and mild neurocognitive disorders may have. Common symptoms among neurocognitive disorders include:

- anxiety

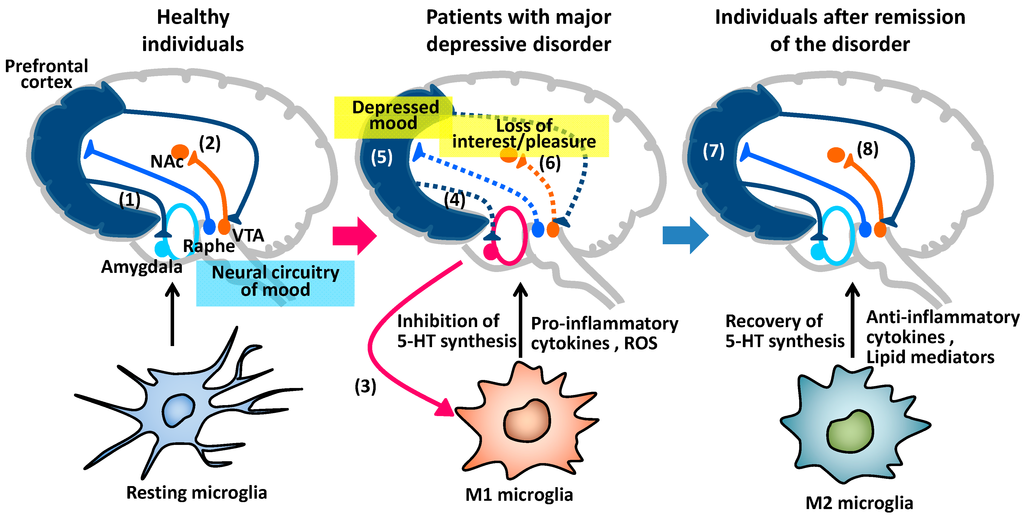

- depression

- elation

- agitation

- confusion

- insomnia (difficulty sleeping)

- hypersomnia (oversleeping)

- apathy

- wandering

- disinhibition

- hyperphagia (extreme hunger or eating)

- hoarding

- hallucinations

- delusions

Treatment for major neurocognitive disorder is primarily based on what symptoms you’re experiencing. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help treat symptoms of anxiety and depression present with major neurocognitive disorder.

For example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help treat symptoms of anxiety and depression present with major neurocognitive disorder.

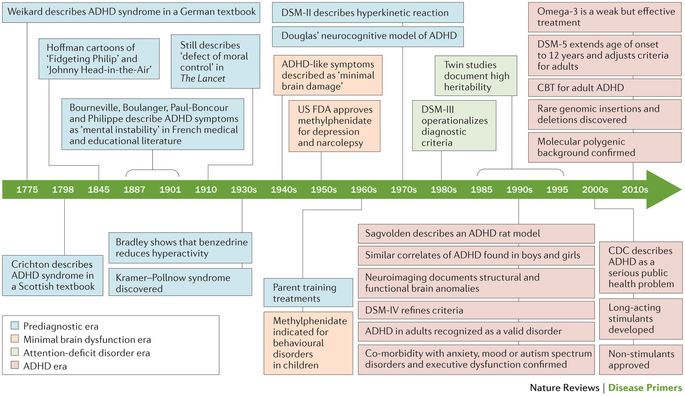

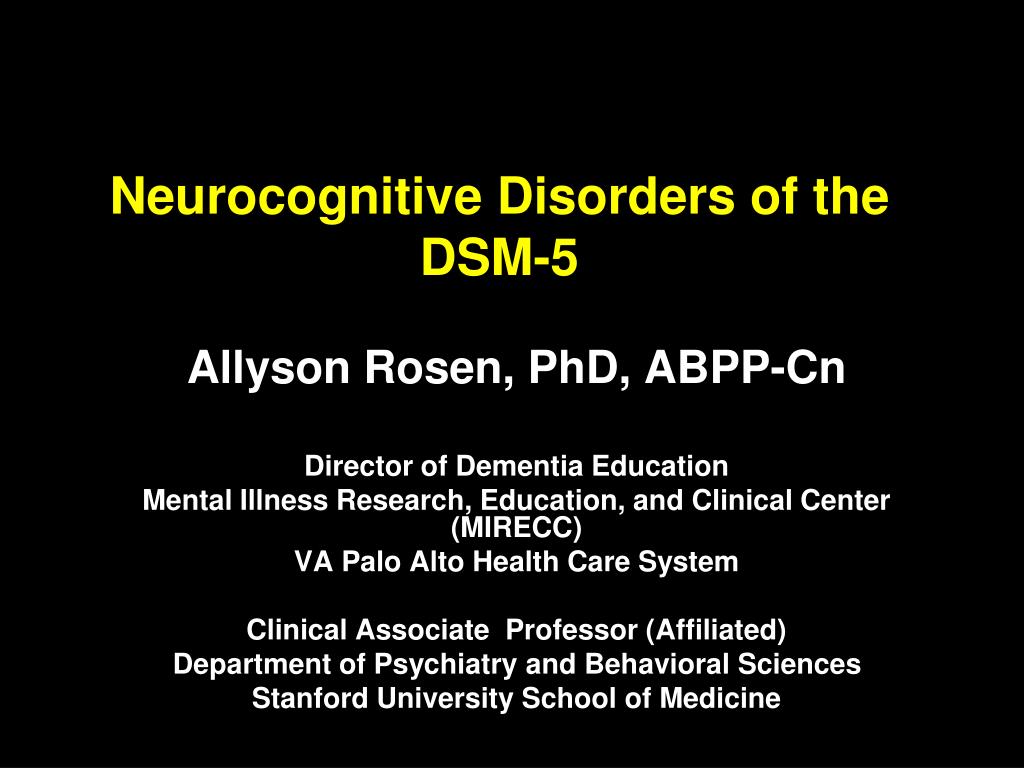

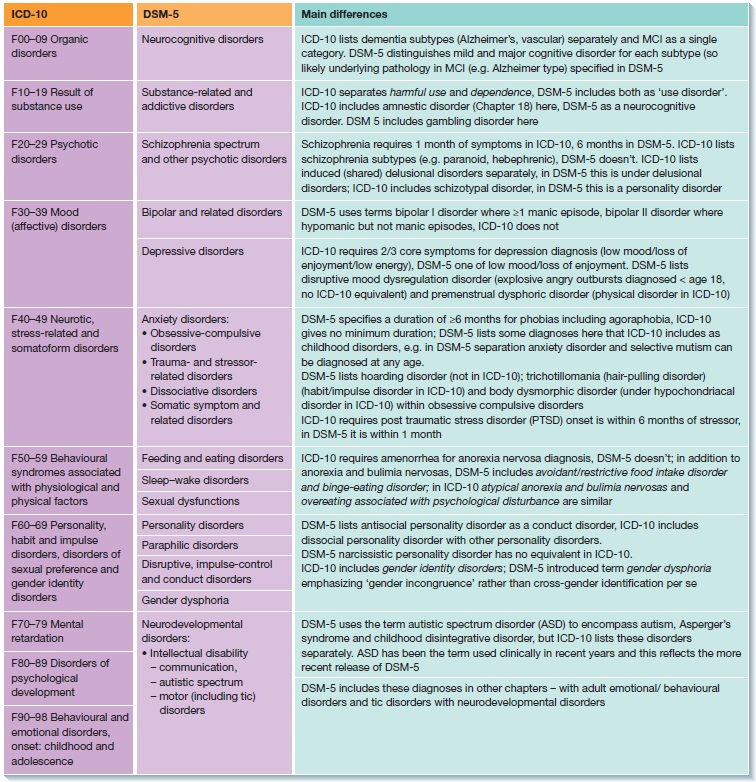

Major neurocognitive disorder is a new name for dementia. The DSM-5 changed the name to major neurocognitive disorder in 2013.

The word ‘dementia’ comes from the Latin word for madness or ‘being out of one’s mind.’ The name change intends to remove stigma from the condition.

According to the DSM-5, major neurocognitive disorder occurs in around 1–2% of people at age 65, and 30% of people by age 85.

In comparison, mild neurocognitive disorder affects around 2–10% of people at age 65 and between 5–25% of people by age 85.

Around 6.2 million people in the United States are living with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common major neurocognitive disorder.

In the United States, Alzheimer’s disease is the sixth leading cause of death — and in people ages 65 and older, it’s the fifth leading cause of death.

The most significant predictor of developing major neurocognitive disorder is age.

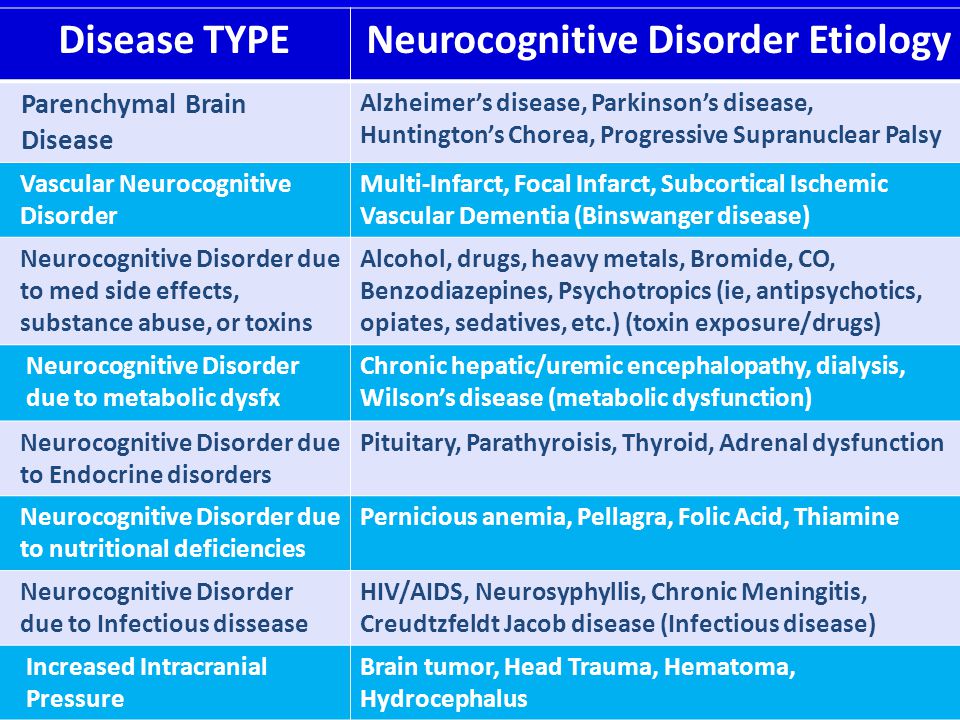

Major neurocognitive disorder may be caused by a variety of factors noted in the DSM-5 as specifiers. These specifiers are:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- frontotemporal lobar degeneration

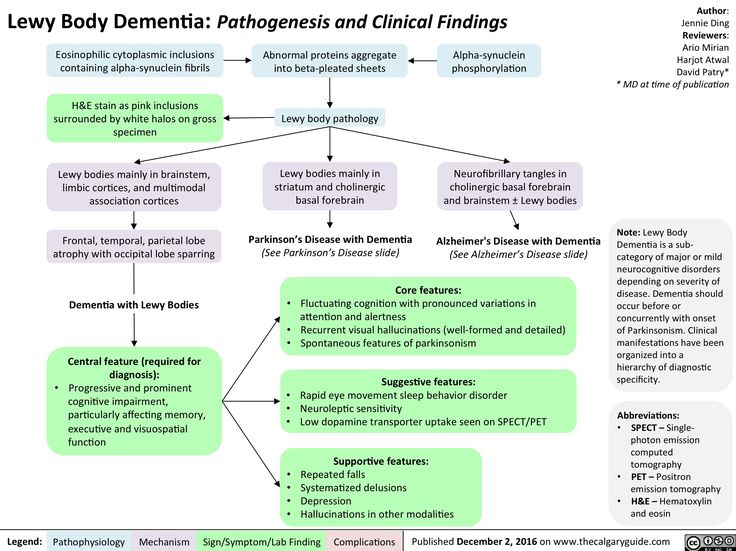

- Lewy body disease

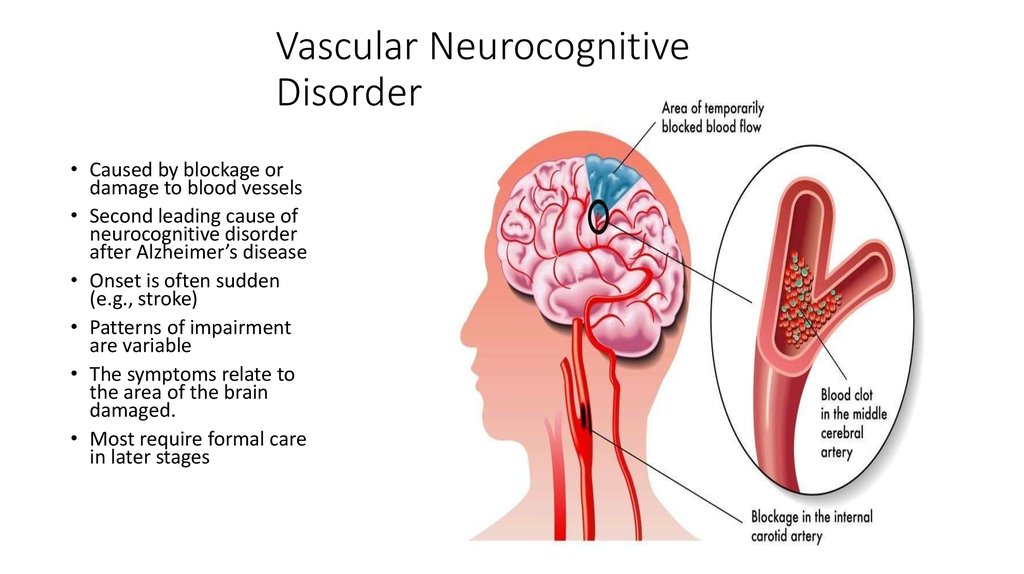

- vascular disease

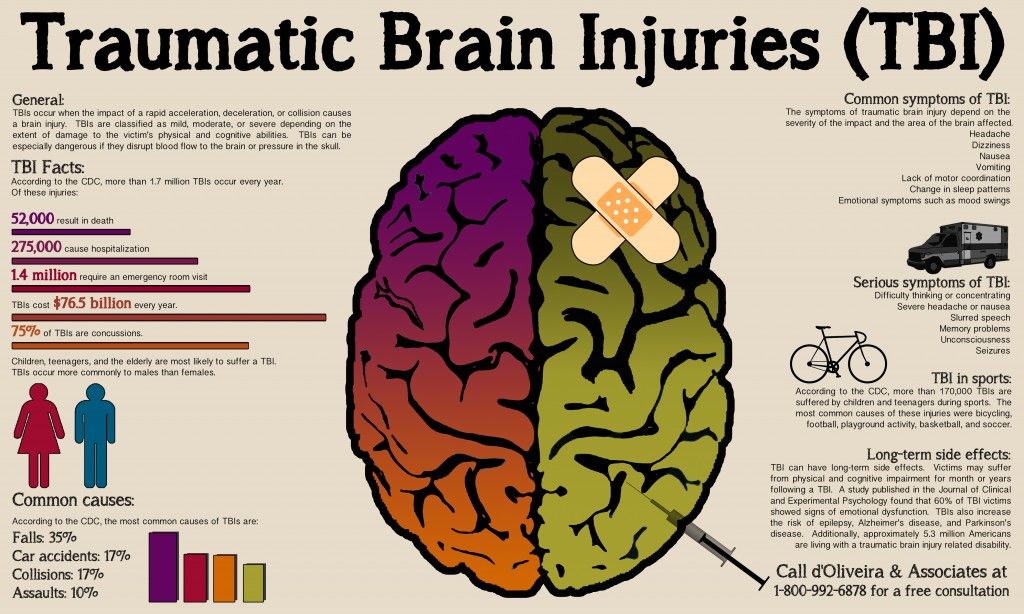

- traumatic brain injury

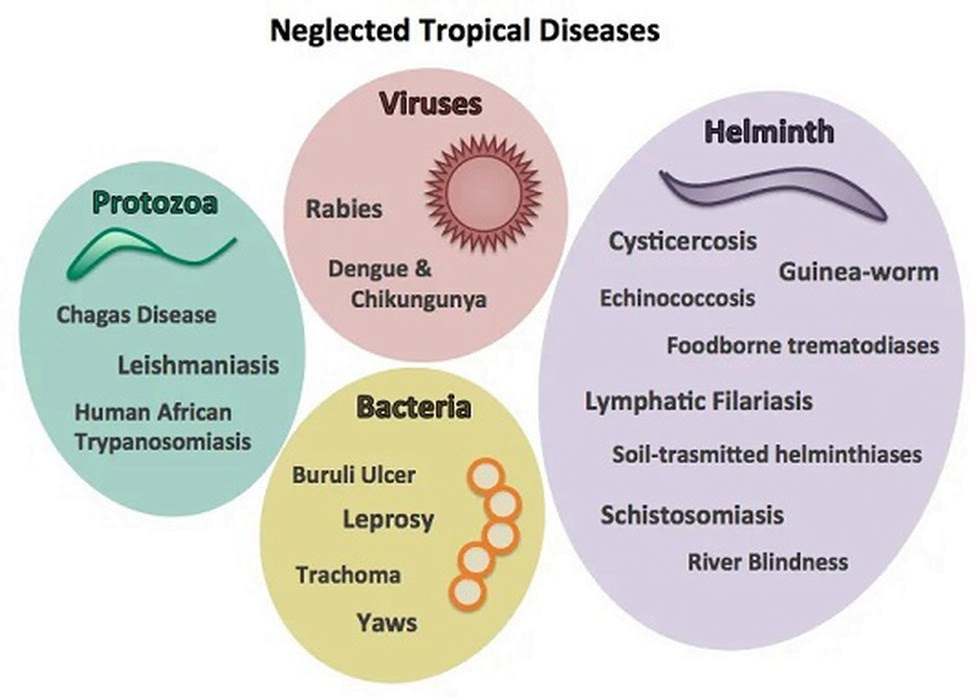

- substance or medication use

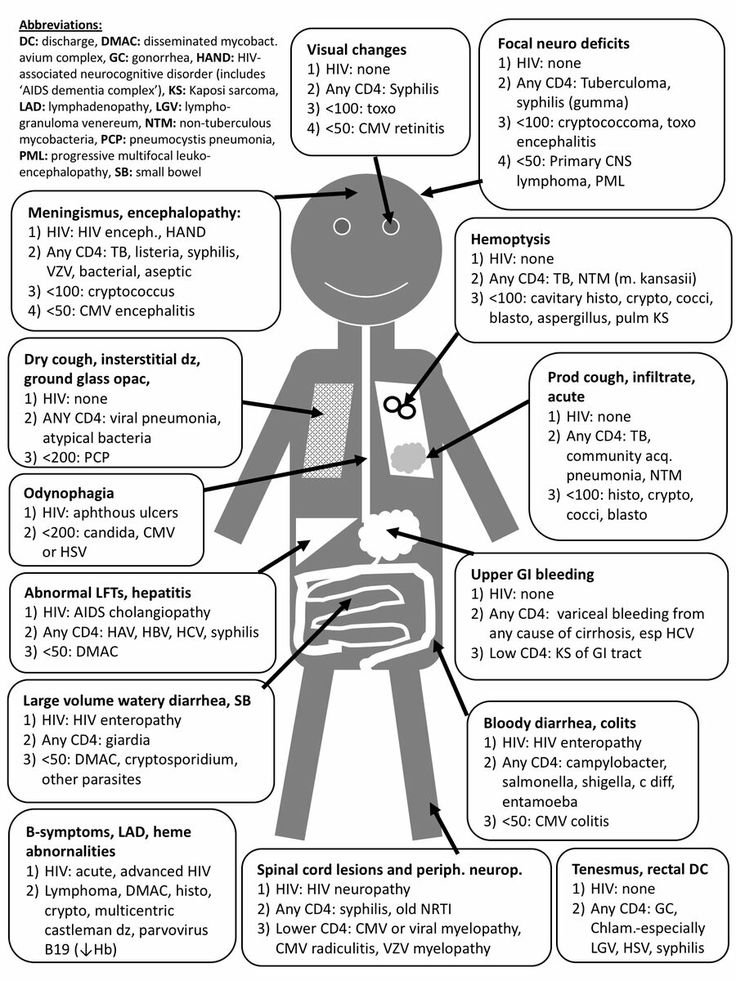

- HIV

- prion disease

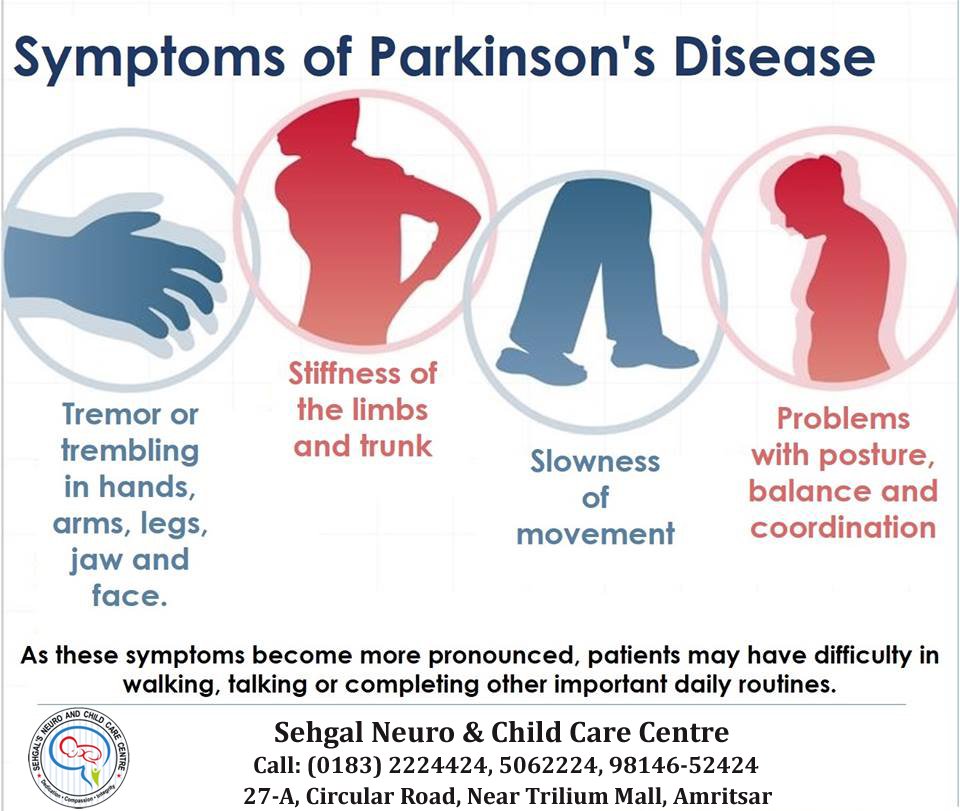

- Parkinson’s disease

- Huntington’s disease

- another medical condition

- multiple etiologies

- unspecified

Females have a higher risk of developing a major neurocognitive disorder, especially Alzheimer’s disease. This may be because females live longer on average than males.

Major neurocognitive disorder is not currently curable. However, some treatments can alleviate symptoms or slow the progression of cognitive decline.

Treatment is mainly dependent on the specific cause.

In some cases, cognitive training may help improve cognition or slow down the progression of symptoms. This non-pharmacological treatment uses guided practices to improve memory, problem-solving, or attention. This type of skills training focuses on the improvement of specific cognitive functions.

This non-pharmacological treatment uses guided practices to improve memory, problem-solving, or attention. This type of skills training focuses on the improvement of specific cognitive functions.

One study in 2018 examined the pharmacological treatments of major neurocognitive disorders.

The researchers recommended that non-pharmacological treatments should be the first line of treatment for major neurocognitive disorders due to the risks and side effects linked with antipsychotics, such as mortality from stroke, myocardial infarction, or infection.

Doctors often prescribe antipsychotics as a treatment for major neurocognitive disorders.

Antipsychotics may be used to relieve mood instability, psychosis, agitation, and aggression in people with neurocognitive disorders. If used for these purposes, it’s important for the medical professional to work with the patient and their family to determine if this is the best course of action.

Standard antipsychotics that can be effective for symptoms include:

- risperidone (Risperdal)

- olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- quetiapine (Seroquel)

- aripiprazole (Abilify)

Not all patients respond to antipsychotics, but those that do respond generally find their symptoms improve in 1–4 weeks.

Consider talking with your doctor if you’re considering antipsychotic medications, as they can have significant side effects.

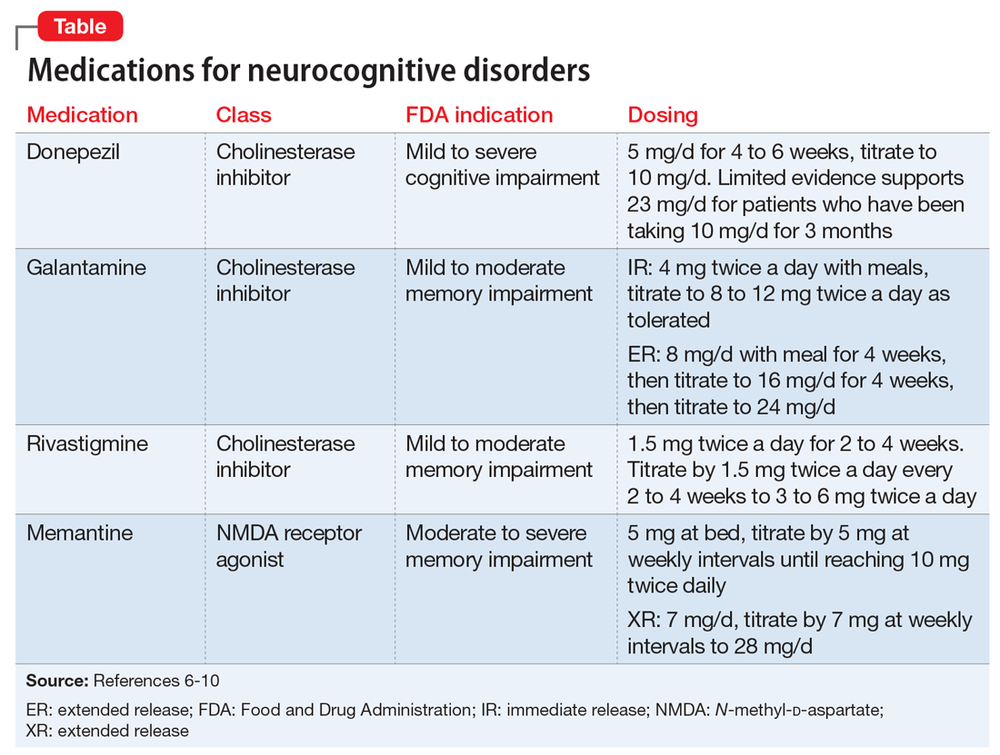

Other types of medications that have minor to moderate effects on treating symptoms of major neurocognitive disorder include:

- cholinesterase inhibitors

- memantine

- selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Consider talking with a doctor to find the appropriate medications for you or your loved one.

If you or a loved one have been diagnosed with major neurocognitive disorder, support is available. You can reach the Alzheimer’s Association helpline 24/7 at 800-272-3900.

If you’re a caregiver for someone who has cognitive deficits, the Family Caregiver Alliance offers information on caring for adults with cognitive disorders and memory impairments.

While it’s not currently possible to reverse cognitive decline, treatments may slow down or help manage symptoms. Consider speaking with your doctor to assess treatment options that may be right for you.

Neurocognitive Disorders (Organic Brain Syndrome)

What Are Neurocognitive Disorders?

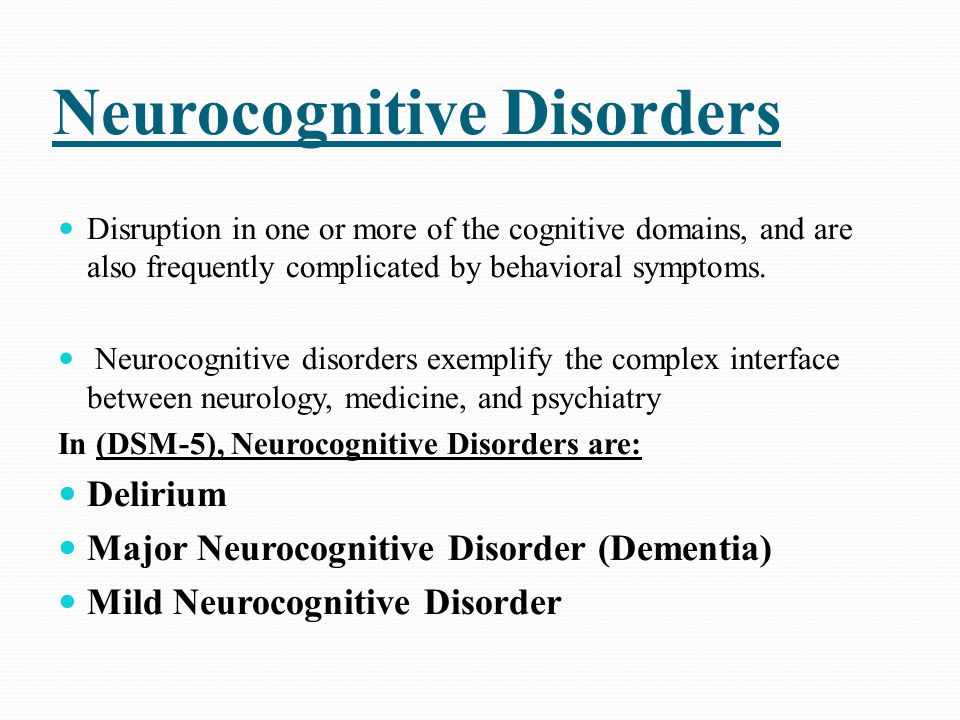

Neurocognitive disorders are a group of conditions that frequently lead to impaired mental function. Organic brain syndrome used to be the term to describe these conditions, but neurocognitive disorders is now the more commonly used term.

Neurocognitive disorders most commonly occur in older adults, but they can affect younger people as well. Reduced mental function may include:

- problems with memory

- changes in behavior

- difficulty understanding language

- trouble performing daily activities

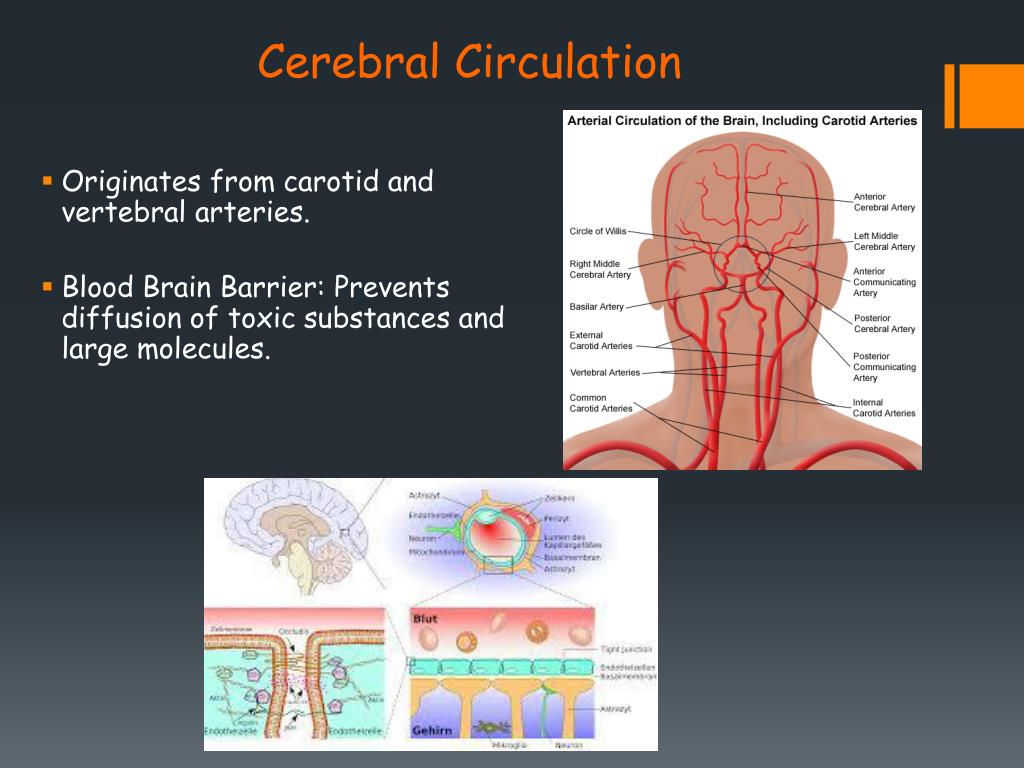

These symptoms may be caused by a neurodegenerative condition, such as Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. Neurodegenerative diseasescause the brain and nerves to deteriorate over time, resulting in a gradual loss of neurological function. Neurocognitive disorders can also develop as a result of brain trauma or substance abuse. Healthcare providers can usually determine the underlying cause of neurocognitive disorders based on the reported symptoms and the results of diagnostic tests. The cause and severity of neurocognitive disorders can help healthcare providers determine the best course of treatment.

Healthcare providers can usually determine the underlying cause of neurocognitive disorders based on the reported symptoms and the results of diagnostic tests. The cause and severity of neurocognitive disorders can help healthcare providers determine the best course of treatment.

The long-term outlook for people with neurocognitive disorders depends on the cause. When a neurodegenerative disease causes the neurocognitive disorder, the condition often gets worse over time. In other cases, decreased mental function may only be temporary, so people can expect a full recovery.

The symptoms of neurocognitive disorders can vary depending on the cause. When the condition occurs as a result of a neurodegenerative disease, people may experience:

- memory loss

- confusion

- anxiety

Other symptoms that may occur in people with neurocognitive disorders include:

- headaches, especially in those with a concussion or traumatic brain injury

- inability to concentrate or focus

- short-term memory loss

- trouble performing routine tasks, such as driving

- difficulty walking and balancing

- changes in vision

The most common cause of neurocognitive disorders is a neurodegenerative disease. Neurodegenerative diseases that can lead to the development of neurocognitive disorders include:

Neurodegenerative diseases that can lead to the development of neurocognitive disorders include:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease

- Huntington’s disease

- dementia

- prion disease

- multiple sclerosis

In people under age 60, however, neurocognitive disorders are more likely to occur after an injury or infection. Nondegenerative conditions that may cause neurocognitive disorders include:

- a concussion

- traumatic brain injury that causes bleeding in the brain or space around the brain

- blood clots

- meningitis

- encephalitis

- septicemia

- drug or alcohol abuse

- vitamin deficiency

Your risk of developing neurocognitive disorders partly depends on your lifestyle and daily habits. Working in an environment with exposure to heavy metals can greatly increase your risk for neurocognitive disorders. Heavy metals, such as lead and mercury, can damage the nervous system over time. This means that frequent exposure to these metals puts you at an increased risk for decreased mental function.

This means that frequent exposure to these metals puts you at an increased risk for decreased mental function.

You’re also more likely to develop neurocognitive disorders if you:

- are over age 60

- have a cardiovascular disorder

- have diabetes

- abuse alcohol or drugs

- participate in sports with a high risk of head trauma, such as football and rugby

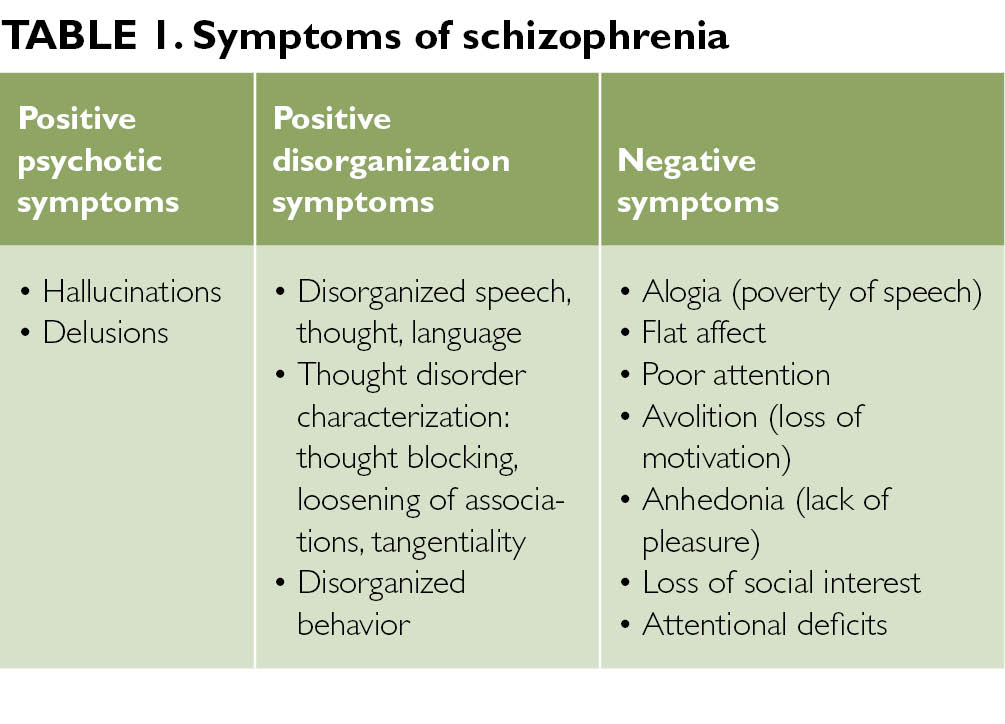

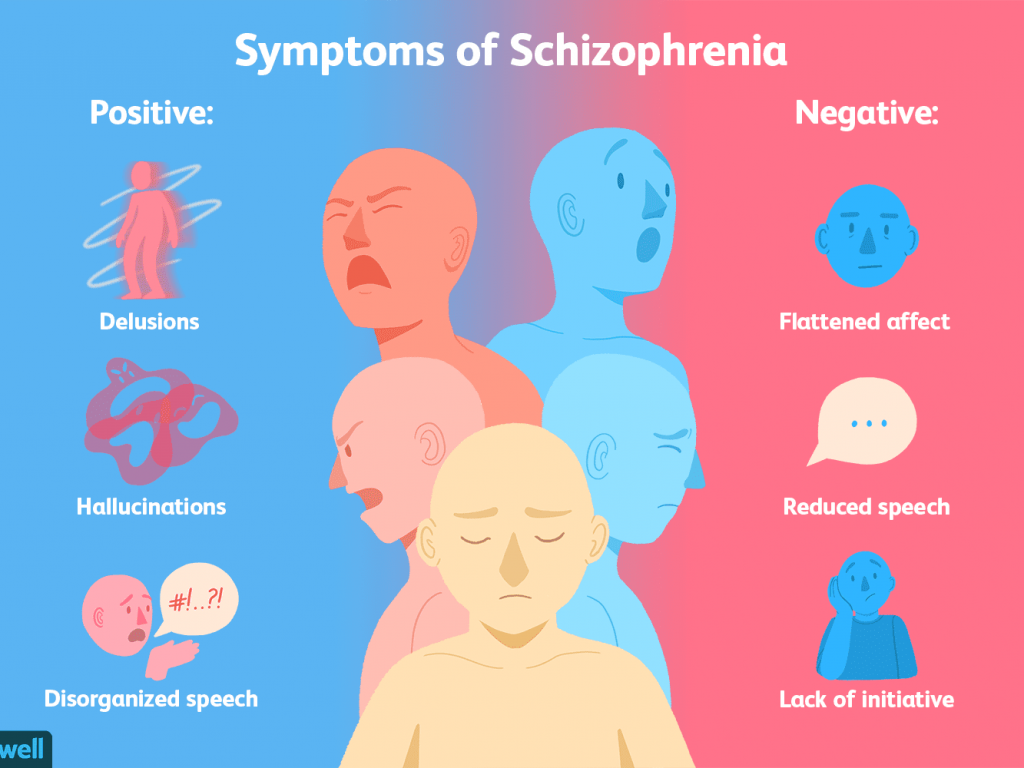

Neurocognitive disorders aren’t caused by a mental disorder. However, many of the symptoms of neurocognitive disorders are similar to those of certain mental disorders, including schizophrenia, depression, and psychosis. To ensure an accurate diagnosis, healthcare providers will perform various diagnostic tests that can differentiate symptoms of neurocognitive disorders from those of a mental disorder. These tests often include:

- cranial CT scan: This test uses a series of X-ray images to create images of the skull, brain, sinuses, and eye sockets. It may be used to examine the soft tissues in the brain.

- head MRI scan: This imaging test uses powerful magnets and radio waves to produce detailed images of the brain. These pictures can show signs of brain damage.

- positron emission tomography (PET) scan: A PET scan uses a special dye that contains radioactive tracers. These tracers are injected into a vein and then spread throughout the body, highlighting any damaged areas.

- electroencephalogram (EEG): An EEG measures the electrical activity in the brain. This test can help detect any problems associated with this activity.

Treatment for neurocognitive disorders varies depending on the underlying cause. Certain conditions may only require rest and medication. Neurodegenerative diseases may require different types of therapy.

Treatments for neurocognitive disorders may include:

- bed rest to give injuries time to heal

- pain medications, such as indomethacin, to relieve headaches

- antibiotics to clear remaining infections affecting the brain, such as meningitis

- surgery to repair any severe brain damage

- occupational therapy to help redevelop everyday skills

- physical therapy to improve strength, coordination, balance, and flexibility

The long-term outlook for people with neurocognitive disorders depends on the type of neurocognitive disorder. Neurocognitive disorders such as dementia or Alzheimer’s present a challenging outlook. This is because there is no cure for those conditions and mental function steadily gets worse over time.

Neurocognitive disorders such as dementia or Alzheimer’s present a challenging outlook. This is because there is no cure for those conditions and mental function steadily gets worse over time.

However, the outlook for people with neurocognitive disorders, such as a concussion or infection, is generally good because these are temporary and curable conditions. In these cases, people can usually expect to make a full recovery.

classification, main causes and treatment uMEDp

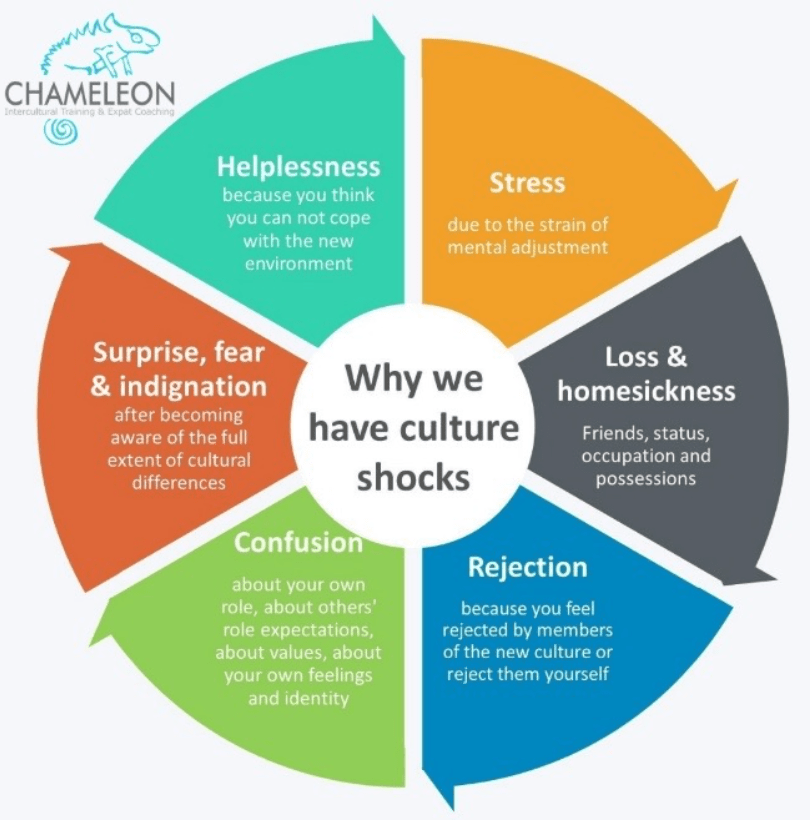

The article provides a definition, classification, diagnostic criteria, principles of pathogenetic and symptomatic therapy of non-dementia cognitive impairment. The possibilities of using the dopaminergic and noradrenergic drug piribedil (Pronoran) for the treatment of mild and moderate cognitive impairments that do not reach the severity of dementia are considered in detail.

Table 1. Cognitive Functions (according to DSM-V)

Table 2. DSM-V

Diagnostic Criteria for Moderate and Severe Neurocognitive Impairment Table 3. Classification of cognitive impairment by severity [5]

Classification of cognitive impairment by severity [5]

Table 4. Diagnostic criteria for depression according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

Fig. 1. The increase in the sum of points on the Montreal scale for assessing cognitive functions during therapy with Pronoran (group A), piracetam (group B), ginkgo biloba (group C) and vinpocetine (group D)

Fig. 2. Dynamics of subjective neurological symptoms during therapy with Pronoran (p < 0.05)

About 90% of the area of the human cerebral cortex is involved in cognitive activity. Therefore, most neurological diseases with an interest in the brain are accompanied by certain cognitive disorders. Usually they are combined with changes in the emotional-behavioral sphere, being united by a common pathomorphological and pathophysiological substrate. A practicing neurologist needs to assess the presence and characteristics of cognitive and other neuropsychiatric disorders and take this information into account when diagnosing syndromic, topical and nosological diseases of the nervous system. nine0004

nine0004

Cognitive impairment is of equal importance to clinicians in other medical specialties. The target organ of many somatic diseases, in particular, diseases of the cardiovascular system that are widespread in old age, is the brain. In this case, the assessment of the state of the brain is extremely important for assessing the effectiveness of controlling the underlying disease and choosing a therapeutic tactic.

The presence of cognitive impairments has an extremely negative impact on the quality of life of the patient and his immediate family, makes it difficult to treat concomitant diseases and carry out rehabilitation measures. Therefore, timely diagnosis and the earliest possible start of therapy for existing cognitive disorders are very important. nine0004

Definition and classification of cognitive impairments

According to the latest revision of the international recommendations for the diagnosis of mental disorders (Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental diseases - DSM-V), cognitive disorders include a decrease in comparison with the premorbid level of one or more higher brain functions that provide the processes of perception, storage, transformation and transmission of information (Table 1) [1]. nine0004

nine0004

It is important not only to establish cognitive decline and conduct its qualitative analysis, but also to quantify the severity of existing disorders. It is known that some drugs that are effective in severe cognitive impairment (dementia) have a much lesser effect on cognitive impairment that does not reach the degree of dementia. This is probably due to various neurochemical changes that are noted at the early and later stages of the pathological process [2–4]. nine0004

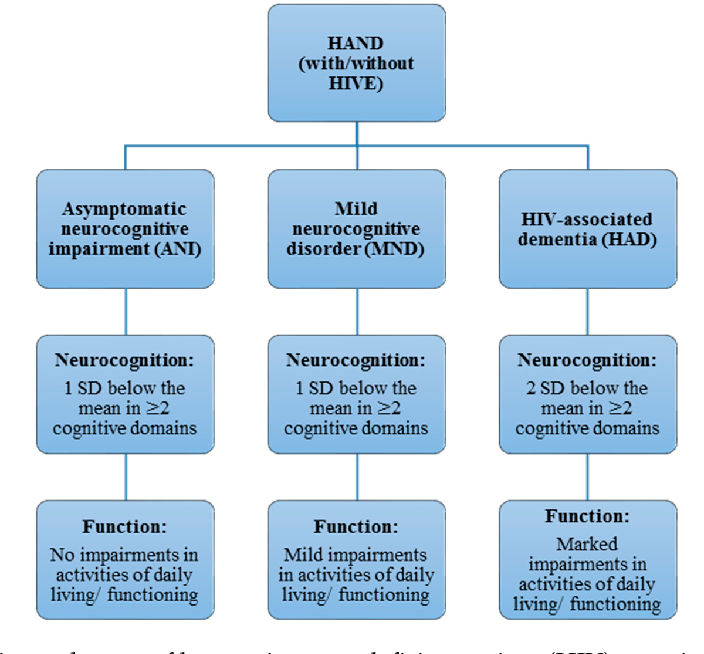

Dementia (or, according to DSM-V, severe neurocognitive impairment) is characterized by significant impairment of higher brain functions that interfere with the normal functioning of the patient. With dementia, due to severe cognitive impairment, the patient is at least partially deprived of independence and needs outside help in the most common life situations (for example, when orienting in the area, shopping in a store) (Table 2) [1].

In the treatment of patients with severe cognitive disorders, priority should be given to drugs with a symptomatic effect, which can reduce the severity of disorders and thereby improve the quality of life of patients and their relatives.

The diagnosis of non-dementia cognitive impairment is established in cases where, despite the existing intellectual defect, the patient retains independence in everyday life. At the same time, the patient may feel some difficulties in mental work, which is reflected in complaints. However, the patient overcomes these difficulties without resorting to outside help (Table 2) [1]. In the treatment of patients with non-dementia cognitive disorders, one should not only use symptomatic therapy, but also take measures to prevent dementia. nine0004

According to the classification of Academician N.N. Yakhno, non-dementia cognitive disorders are divided into mild and moderate (Table 3) [5]. At the same time, patients with moderate impairments may experience difficulties in the most complex and unusual activities for the patient. At the same time, patients with mild disorders are completely independent and independent in all types of activity, including the most difficult one.

In recent years, the attention of neurologists, psychiatrists and representatives of other neurosciences has increased to an even earlier stage of cognitive deficiency - the so-called subjective cognitive impairment. The wording "subjective cognitive impairment" (subjective memory impairment, cognitive complaints) is currently widely used both in the scientific literature and in everyday clinical practice as an independent diagnosis. This diagnosis is made if there are cognitive complaints, while the results of objective cognitive tests remain within the age norm. nine0004

The wording "subjective cognitive impairment" (subjective memory impairment, cognitive complaints) is currently widely used both in the scientific literature and in everyday clinical practice as an independent diagnosis. This diagnosis is made if there are cognitive complaints, while the results of objective cognitive tests remain within the age norm. nine0004

Patients may complain of increased forgetfulness, decreased concentration of attention, increased fatigue during mental work, and sometimes difficulty in finding the right word in a conversation. These complaints are a very urgent problem for the patient, which can serve as an independent or main reason for contacting a doctor. At the same time, the use of standard cognitive tests does not reveal any significant deviations from the accepted standards. Patients with subjective cognitive disorders fully maintain independence in everyday life. Cognitive difficulties are also invisible from the outside: relatives, colleagues and other persons always assess the patient's cognitive abilities as quite intact. nine0004

nine0004

Currently, the following international diagnostic criteria (2014) for the syndrome of subjective cognitive impairment are known [6]:

-

patient complaints about a persistent deterioration in mental performance compared to the past, which arose for no apparent reason;

-

the absence of any deviations from the age norm according to the cognitive tests used to diagnose Alzheimer's disease and other dementing diseases; nine0004

-

cognitive complaints are not associated with any established diagnosis of a neurological, psychiatric disease or intoxication.

The dissociation between patient complaints, test results, and patients' day-to-day functioning raises legitimate questions about the true nature of the complaints. These issues are still far from being resolved and are being actively studied. At the present stage of scientific knowledge, it seems that patients with subjective cognitive impairments represent a very heterogeneous group, which includes both patients with the earliest stages of the dementing process, and patients with disorders of the anxiety-depressive and hypochondria spectrum. nine0004

nine0004

In some cases, the predominantly subjective nature of disorders is explained by methodological difficulties in objectifying cognitive status. Currently, there are no generally accepted recommendations on the use of specific methods for the diagnosis of dementia or non-dementia cognitive impairment. Therefore, in practice, tests of varying degrees of sensitivity, specificity and reproducibility are used. The use of tests with low sensitivity will lead to underdiagnosis of mild and moderate cognitive impairments and to overdiagnosis of so-called subjective impairments. nine0004

The diagnosis of "subjective cognitive impairment" is often received by patients with a high premorbid intellectual level. The cognitive functions reduced as a result of a cerebral disease in comparison with the individual norm will formally be within the average statistical standard for a long time. Consequently, cognitive decline can remain formally unconfirmed for a long time, in other words, “subjective”.

Complaints of a cognitive nature may be due to anxiety-depressive disorders in the absence of an organic cerebral disease. Thus, patients with a high level of anxiety will be overly concerned about minor situational forgetfulness. In this case, the reason for going to the doctor is such widespread complaints, including among healthy people, such as “I don’t remember why I came to the room”, “I don’t remember what I put where”, “I didn’t recognize a familiar person or didn’t remember him surname", etc. nine0004

However, the greatest research interest in a heterogeneous group of patients with subjective cognitive impairments is caused by patients with reduced tolerance to mental stress, since this pathological phenomenon may indeed be the earliest clinical manifestation of the dementing process. As is known, at the very initial stages of a neurodegenerative or cerebrovascular disease, clinical symptoms may be absent, despite the presence of organic brain damage, sometimes significant. This is due to the so-called cerebral reserve, that is, the compensatory capabilities of the brain. The presence of such opportunities will lead to a false negative test result. At the same time, in everyday life, the patient may experience difficulties in special conditions when the cerebral reserve is depleted and cannot overcome the difficulties that arise, for example, in a state of fatigue or emotional stress. At present, the development of the "intellectual treadmill" methodology is being carried out very actively in the world. It will allow assessing the degree of tolerance to increased mental stress, which may decrease to the development of clinically defined cognitive disorders. nine0004

This is due to the so-called cerebral reserve, that is, the compensatory capabilities of the brain. The presence of such opportunities will lead to a false negative test result. At the same time, in everyday life, the patient may experience difficulties in special conditions when the cerebral reserve is depleted and cannot overcome the difficulties that arise, for example, in a state of fatigue or emotional stress. At present, the development of the "intellectual treadmill" methodology is being carried out very actively in the world. It will allow assessing the degree of tolerance to increased mental stress, which may decrease to the development of clinically defined cognitive disorders. nine0004

International studies show that the risk of developing dementia among patients with subjective cognitive impairment is significantly higher than the average in the population [6]. Therefore, even isolated complaints that are not confirmed by cognitive tests should not be ignored by the attending physicians. They cannot serve as a basis for any specific clinical diagnosis, but their presence is an indication for active prevention, primarily non-pharmacological (mental and physical activity, optimization of nutrition and lifestyle). nine0004

They cannot serve as a basis for any specific clinical diagnosis, but their presence is an indication for active prevention, primarily non-pharmacological (mental and physical activity, optimization of nutrition and lifestyle). nine0004

Diagnosis of moderate cognitive impairment

As follows from the above criteria (Table 2), the diagnosis of the syndrome of moderate neurocognitive impairment is based, firstly, on the complaints of patients and / or their relatives, and secondly, on objective test results. At the same time, it should be borne in mind that complaints of a cognitive nature are far from always straightforward. Usually, patients with the so-called amnestic type of the syndrome of moderate neurocognitive impairment complain of a decrease in memory or increased forgetfulness, in which progressive memory disorders predominate in their cognitive status. In such patients, Alzheimer's disease is most often established in the future. However, according to the analysis of specialized outpatient admission of patients with cognitive impairment, the most common cause of the syndrome of moderate cognitive impairment is cerebrovascular pathology. Thus, the experience of the first Russian clinic of memory disorders shows that dyscirculatory encephalopathy or the consequences of acute cerebrovascular accidents cause 68% of moderate cognitive impairments [7]. nine0004

Thus, the experience of the first Russian clinic of memory disorders shows that dyscirculatory encephalopathy or the consequences of acute cerebrovascular accidents cause 68% of moderate cognitive impairments [7]. nine0004

Vascular cognitive impairments in most cases are of the so-called subcortical-frontal type. At the same time, the memory for current events and life events practically does not suffer, and the cognitive status is dominated by a decrease in the concentration of attention and the pace of cognitive activity (bradyphrenia), a violation of frontal control functions (planning and control). A characteristic feature is also the frequent combination of cognitive and emotional-behavioral disorders: depression, apathy or affective lability. It should be emphasized that emotional and behavioral disorders in chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency are of an organic nature and are caused by the same brain damage (dysfunction of fronto-striatal connections) as cognitive impairment. The comorbidity of vascular depression and vascular cognitive impairment is at least 80% [8–11]. nine0004

The comorbidity of vascular depression and vascular cognitive impairment is at least 80% [8–11]. nine0004

Patients with vascular cognitive disorders rarely complain of forgetfulness, since their memory is relatively intact. The structure of complaints is dominated by the so-called subjective neurological symptoms: headache, non-systemic dizziness, noise and heaviness in the head, increased fatigue, sleep disturbances. These symptoms are quite typical for the initial stages of dyscirculatory encephalopathy and in the recent past were considered as an important sign of chronic ischemic brain damage. It is now obvious that headache, dizziness and other unpleasant sensations in the head cannot be a direct result of cerebral ischemia. The pathogenesis of subjective neurological symptoms is more complex and is associated primarily with existing cognitive, emotional and motor disorders. So, headache most often has the character of a tension headache, which, as you know, is almost always caused by anxiety and / or depression. Sleep disturbances also have an emotional cause. Increased fatigue can either be a sign of depression (Table 4) or reflect a decrease in mental performance. In the latter case, this complaint is the subjective equivalent of cognitive disorders. Dizziness in chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency is usually non-systemic and is described as a feeling of unsteadiness when walking. Behind this sensation, as a rule, there are real imbalances due to damage to the fronto-striatal and fronto-cerebellar connections. nine0004

Sleep disturbances also have an emotional cause. Increased fatigue can either be a sign of depression (Table 4) or reflect a decrease in mental performance. In the latter case, this complaint is the subjective equivalent of cognitive disorders. Dizziness in chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency is usually non-systemic and is described as a feeling of unsteadiness when walking. Behind this sensation, as a rule, there are real imbalances due to damage to the fronto-striatal and fronto-cerebellar connections. nine0004

Subjective neurological symptoms are almost always present in the initial stages of chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency. They cannot be the basis for a diagnosis, but should lead the doctor to suspect a chronic cerebrovascular disease. To confirm the diagnosis, a thorough assessment of the cognitive and emotional status using objective methods is necessary. At the stage of moderate (non-dementic) cognitive disorders, the most sensitive methods should be used, for example, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale [12]. nine0004

nine0004

Pathogenetic and symptomatic therapy of non-dementia cognitive impairments

To date, a unified generally accepted protocol for the management of patients with cognitive impairments that do not reach the severity of dementia has not been finally developed. Many international studies have failed to demonstrate that pharmacotherapy with drugs such as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, piracetam, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevents or reduces the risk of dementia [2-4]. At the same time, the same studies showed the ability of some of the above drugs to reduce the severity of symptoms in patients with mild cognitive impairment syndrome. nine0004

Currently, vasotropic and neurometabolic drugs, the dopaminergic and noradrenergic drug piribedil (Pronoran), and NMDA receptor blockers are widely used empirically in everyday clinical practice.

The results of a number of large studies and practical experience indicate the clinical effectiveness of the drug piribedil (Pronoran). Pronoran has a complex mechanism of action: it stimulates postsynaptic D 2 / D 3 - dopamine receptors and blocks presynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptors. At the same time, the blockade of presynaptic adrenergic receptors leads to an increase in cerebral noradrenergic activity. Thus, against the background of the use of this drug, the activity of two cerebral neurotransmitter systems increases: dopaminergic and noradrenergic. Both of these systems are directly involved in cognitive activity. At the same time, it is believed that dopaminergic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex, indirectly through the mesocortical dopaminergic pathway, plays an important role in attention processes and provides intellectual flexibility, that is, the ability to change the behavioral paradigm. Noradrenergic activation is important for the processes of memorization and reproduction of information, since it provides the optimal level of concentration and motivation for mnestic activity.

Pronoran has a complex mechanism of action: it stimulates postsynaptic D 2 / D 3 - dopamine receptors and blocks presynaptic alpha-adrenergic receptors. At the same time, the blockade of presynaptic adrenergic receptors leads to an increase in cerebral noradrenergic activity. Thus, against the background of the use of this drug, the activity of two cerebral neurotransmitter systems increases: dopaminergic and noradrenergic. Both of these systems are directly involved in cognitive activity. At the same time, it is believed that dopaminergic stimulation of the prefrontal cortex, indirectly through the mesocortical dopaminergic pathway, plays an important role in attention processes and provides intellectual flexibility, that is, the ability to change the behavioral paradigm. Noradrenergic activation is important for the processes of memorization and reproduction of information, since it provides the optimal level of concentration and motivation for mnestic activity. With age, the synthesis and activity of both dopamine and norepinephrine decrease. Therefore, the correction of these neurotransmitter disorders against the background of the use of Pronoran helps to reduce the severity of age-associated disorders of attention and memory. In addition, due to the adrenoblocking and dopaminergic action, Pronoran also has a favorable vasotropic effect, which creates additional benefits in case of cognitive impairment of vascular etiology [13–16]. nine0004

With age, the synthesis and activity of both dopamine and norepinephrine decrease. Therefore, the correction of these neurotransmitter disorders against the background of the use of Pronoran helps to reduce the severity of age-associated disorders of attention and memory. In addition, due to the adrenoblocking and dopaminergic action, Pronoran also has a favorable vasotropic effect, which creates additional benefits in case of cognitive impairment of vascular etiology [13–16]. nine0004

In clinical practice, Pronoran is used to treat mild and moderate cognitive impairment that does not reach the severity of dementia in patients over 50 years of age. The drug can be prescribed both for vascular cognitive impairment and at the initial stages of the neurodegenerative process. A large number of clinical studies have been performed for this indication, including those using a double-blind method. For example, in France in the 1980s. 14 clinical studies were conducted, in which more than 7 thousand patients with non-dementia cognitive impairments took part. It has been shown that Pronoran contributes to a significant improvement in memory, concentration and intellectual flexibility, that is, the ability to change the paradigm of behavior depending on external conditions [17, 18]. In 2001, the clinical efficacy of Pronoran was again demonstrated by D. Nagaradja and S. Jayashree. The authors used Pronoran in the syndrome of moderate cognitive impairment in accordance with modern diagnostic criteria. It was shown that against the background of the study drug, there was a more than two-fold increase in the frequency of cognitive improvement on the short mental status assessment scale compared with placebo, which was statistically and clinically significant [19].

It has been shown that Pronoran contributes to a significant improvement in memory, concentration and intellectual flexibility, that is, the ability to change the paradigm of behavior depending on external conditions [17, 18]. In 2001, the clinical efficacy of Pronoran was again demonstrated by D. Nagaradja and S. Jayashree. The authors used Pronoran in the syndrome of moderate cognitive impairment in accordance with modern diagnostic criteria. It was shown that against the background of the study drug, there was a more than two-fold increase in the frequency of cognitive improvement on the short mental status assessment scale compared with placebo, which was statistically and clinically significant [19].

Currently, Russian specialists also have significant experience in using Pronoran in patients with cognitive impairments that do not reach the severity of dementia. Thus, as part of the PROMETHEUS study, 574 patients from 33 cities in 30 regions of Russia, including 336 women and 207 men, aged 60 to 89 years (mean age 69. 5 ± 5.5 years) received Pronoran with mild or moderate cognitive impairment. . Patients with cognitive complaints who scored 25–27 points on the Mini Mental Status Scale or who performed the clock drawing test with errors but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for dementia were selected for treatment. During therapy, a statistically significant improvement in cognitive functions was recorded, which was noted as early as the sixth week of treatment and further increased until the end of the 12-week follow-up. At the same time, one part of the patients received Pronoran monotherapy, and the other part received Pronoran in combination with vasotropic and / or neurometabolic drugs. No significant difference was shown between these groups of patients, that is, the combination of Pronoran with vasotropic and neurometabolic therapy had no advantages over monotherapy with the study drug [20, 21]. nine0004

5 ± 5.5 years) received Pronoran with mild or moderate cognitive impairment. . Patients with cognitive complaints who scored 25–27 points on the Mini Mental Status Scale or who performed the clock drawing test with errors but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for dementia were selected for treatment. During therapy, a statistically significant improvement in cognitive functions was recorded, which was noted as early as the sixth week of treatment and further increased until the end of the 12-week follow-up. At the same time, one part of the patients received Pronoran monotherapy, and the other part received Pronoran in combination with vasotropic and / or neurometabolic drugs. No significant difference was shown between these groups of patients, that is, the combination of Pronoran with vasotropic and neurometabolic therapy had no advantages over monotherapy with the study drug [20, 21]. nine0004

In the largest Russian non-comparative study, Pronoran was treated by more than 2,000 patients aged 50 to 94 years (mean age 64. 9 ± 8.3 years) with a diagnosis of stage 1 or 2 dyscirculatory encephalopathy and with mild or moderate cognitive impairment. violations. All patients took Pronoran for three months. According to the attending physicians, in 2/3 of cases there was a significant or moderate improvement in cognitive and other neurological functions [22]. nine0004

9 ± 8.3 years) with a diagnosis of stage 1 or 2 dyscirculatory encephalopathy and with mild or moderate cognitive impairment. violations. All patients took Pronoran for three months. According to the attending physicians, in 2/3 of cases there was a significant or moderate improvement in cognitive and other neurological functions [22]. nine0004

According to some data, the magnitude of the therapeutic effect of dopamine and noradrenergic therapy in relation to non-dementia cognitive disorders may be greater than that of other vasotropic and neurometabolic drugs actively used in clinical practice. In the FUETE study, 189 patients were observed, including 139 women and 57 men, aged 42 to 82 years (mean age 63.6 ± 8.5 years) with cognitive disorders that did not reach the severity of dementia, against the background of arterial hypertension and cerebral atherosclerosis . The patients were treated with various drugs, while the representatives of the therapeutic groups did not differ in age, level of education and clinical features of the underlying disease. Against the background of the therapy, there was a regression of both subjective and objective cognitive disorders in all compared therapeutic groups. At the same time, the severity of subjective improvement and objective dynamics of cognitive tests against the background of the use of Pronoran after two months of therapy were significantly greater compared with vasotropic and neurometabolic therapy (Fig. 1) [23]. nine0004

Against the background of the therapy, there was a regression of both subjective and objective cognitive disorders in all compared therapeutic groups. At the same time, the severity of subjective improvement and objective dynamics of cognitive tests against the background of the use of Pronoran after two months of therapy were significantly greater compared with vasotropic and neurometabolic therapy (Fig. 1) [23]. nine0004

Regression of cognitive disorders, according to special tests, is the main criterion for the effectiveness of the therapy. However, as noted above, many patients with moderate cognitive impairment, primarily of a vascular nature, also complain of headache, non-systemic dizziness, noise, heaviness or other unpleasant sensations in the head, increased fatigue and sleep disturbances. These complaints are of the same nature and are associated with both cognitive impairment and changes in the emotional status of patients at the initial stage of chronic cerebrovascular insufficiency. They significantly reduce the quality of life of patients and are often the main reason for visiting a neurologist. Therefore, the dynamics of subjective neurological symptoms in patients with a syndrome of moderate neurocognitive disorders of vascular etiology during therapy is extremely important for assessing the significance of the clinical effect and the degree of influence of therapy on the daily life of patients. Regression of subjective neurological symptoms contributes most to adherence to therapy. nine0004

They significantly reduce the quality of life of patients and are often the main reason for visiting a neurologist. Therefore, the dynamics of subjective neurological symptoms in patients with a syndrome of moderate neurocognitive disorders of vascular etiology during therapy is extremely important for assessing the significance of the clinical effect and the degree of influence of therapy on the daily life of patients. Regression of subjective neurological symptoms contributes most to adherence to therapy. nine0004

In the study by N.N. Yakhno et al. (2006) 29 patients with a diagnosis of "moderate cognitive impairment" against the background of dyscirculatory encephalopathy of the first or second stage received Pronoran for three months [24]. At the same time, no other vasotropic or neurometabolic drugs were used. During treatment with Pronoran, the frequency and severity of headache, dizziness, fatigue and subjective feeling of forgetfulness significantly decreased (Fig. 2). Other authors also reported on the weakening of subjective neurological symptoms during the use of Pronoran [17, 18]. Thus, dopamine and noradrenergic therapy contributes to a significant improvement in the well-being of patients, and, consequently, improves the quality of life and adherence to ongoing therapeutic measures. nine0004

Thus, dopamine and noradrenergic therapy contributes to a significant improvement in the well-being of patients, and, consequently, improves the quality of life and adherence to ongoing therapeutic measures. nine0004

It can be summarized that to date, Pronoran has established itself as an effective drug that improves cognitive abilities and well-being in patients with the initial stages of organic cerebral diseases without dementia. In contrast to Parkinson's disease, in which significantly higher doses are used, for non-demented cognitive impairment, Pronoran is prescribed at a dose of 50 mg / day once a day. The recommended duration of therapy is at least three months. nine0004

Neurocognitive syndrome in COVID-19. Clinical cases | Pashkovsky

1. Kavanaugh BC, Cancilliere MK, Spirito A. Neurocognitive heterogeneity across the spectrum of psychopathology: need for improved approaches to deficit detection and intervention. CNS Spectr. 2020;25(3):436–444. 2. Maury A, Lyoubi A, Peiffer-Smadja N, de Broucker T, Meppiel E. Neurological manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses: A narrative review for clinicians. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177(1–2):51–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.10.001 Epub 2020 Dec 16. PMID: 33446327; PMCID: PMC7832485

Neurological manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses: A narrative review for clinicians. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2021;177(1–2):51–64. DOI: 10.1016/j.neurol.2020.10.001 Epub 2020 Dec 16. PMID: 33446327; PMCID: PMC7832485

3. Hassett CE, Frontera JA. Neurologic aspects of coronavirus disease of 2019 infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021;34(3):217–227. DOI: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000731 PMID: 33769966

Al-Shahi Salman R, Menon DK, Nicholson TR, Benjamin LA, Carson A, Smith C, Turner MR, Solomon T, Kneen R, Pett SL, Galea I, Thomas RH, Michael BD; CoroNerve Study Group. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875–882. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X Epub 2020 Jun 25. Erratum in: Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul 14;: PMID: 32593341; PMCID: PMC7316461

5. Melegari G, Rivi V, Zelent G, Nasillo V, De Santis E, Melegari A, Bevilacqua C, Zoli M, Meletti S, Barbieri A. Mild to Severe Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: Cases Reports . Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3673. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph28073673 PMID: 33915937; PMCID: PMC8036948

Mild to Severe Neurological Manifestations of COVID-19: Cases Reports . Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3673. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph28073673 PMID: 33915937; PMCID: PMC8036948

6. Whiteside DM, Oleynick V, Holker E, Waldron EJ, Porter J, Kasprzak M. Neurocognitive defi cits in severe COVID-19 infection: Case series and proposed model. Clinic Neuropsychol. 2021;35(4):799–818. DOI: 10.1080/13854046.2021.1874056 Epub 2021 Jan 25. PMID: 33487098

7. Negrini F, Ferrario I, Mazziotti D, Berchicci M, Bonazzi M, de Sire A, Negrini S, Zapparoli L. Neuropsychological Features of Severe Hospitalized Corvirus Disease 2019 Patients at Clinical Stability and Clues for Postacute Rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102(1):155–158. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.09.376 Epub 2020 Sep 28. PMID: 32991870; PMCID: PMC7521874

8. Llamas-Velasco S, Llorente-Ayuso L, Contador I, Bermejo-Pareja F. Versiones en español del Minimental State Examination (MMSE). Cuestiones para su uso en la practica clinica [Spanish versions of the Minimental State Examination (MMSE).