Sensorimotor obsessions treatment

CBT for Sensorimotor OCD in Sevenoaks and London | CBT for Body Sensations

We provide Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Sensorimotor OCD from our offices in London as well as from over 100 plus locations across the UK. We can also deliver Sensorimotor OCD treatment online via video link. If you want to talk to a CBT specialist about Sensorimotor OCD, call +44 1732 808626 or email [email protected] to organise an initial informal call with a member of our CBT team.

Therapist Credentials

Our CBT therapists are professionally qualified in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and other evidence-based psychological approaches including EMDR, Clinical Psychology, ACT, DBT and CFT. All of our CBT therapists hold full accreditation with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP).

What is Sensorimotor OCD?

Sensorimotor OCD is a subtype of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder focused on bodily feelings, posture, sensations, physical functions and the internal sounds of thinking itself. This involves a preoccupation with the internal feeling or bodily function, worry and self-doubt about escaping the feeling and compulsions to prevent, avoid or distract one’s self from the problem.

Common body focused obsessions include:

- Heartbeat and pulse.

- Breathing sensations and effort.

- Blinking.

- The mechanism of eye contact.

- Swallowing.

- Bladder or bowel pressure

- Skin tingling, itching or high sensitivity.

- Position of limbs and body posture.

- Joints popping or creaking in movement.

- How the hair falls, touches or contacts forehead or neck.

- Visual floaters or the nose in the field of vision.

- Sensitivity to the internal sound or mechanism of thinking.

Hyperawareness of internal thoughts also known as cognitive hyperawareness, involves an internal sensitivity to the sounds, rhythm and structure of thoughts and thinking.

Cognitive hyperawareness is not the same as obsessional thinking. Whilst obsessional thinking is a common aspect of many forms of OCD, cognitive hyperawareness involves a sensitivity to the perceived “sounds” of the internal thoughts and ruminations themselves.

Whilst obsessional thinking is a common aspect of many forms of OCD, cognitive hyperawareness involves a sensitivity to the perceived “sounds” of the internal thoughts and ruminations themselves.

How sensorimotor OCD is maintained

Sensorimotor OCD is maintained by three psychological processes. These include:

- Cognitive Avoidance / Suppression - trying to not notice or push the sensation out of awareness. This creates a rebound effect and directs attention to the sensation that the individual is attempting to avoid.

- Overthinking - continuously thinking about and attempting to figure out the problem. This increases worry, rumination and meta-obsessions, where the individual worries about the worry itself.

- Checking / Monitoring – physically or mentally monitoring and checking the sensations, seeking reassurance and over-researching the problem. This directs attention and increases awareness of the unwanted feelings and sensations.

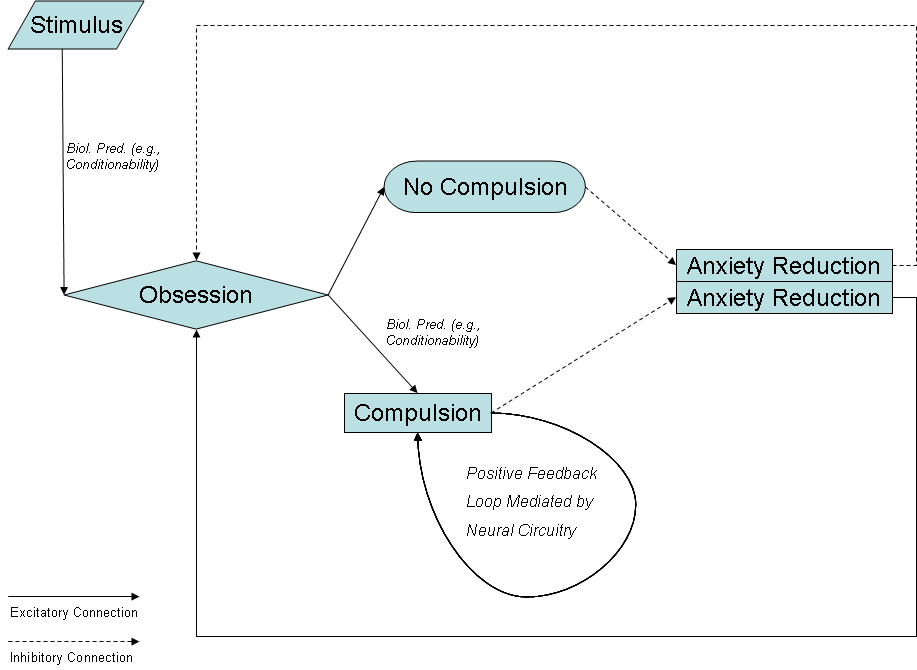

like all forms of OCD, sensorimotor OCD involves obsessional and compulsive processes:

The Obsessional Process

Whether the sensitivity is focused on a bodily sensation, physical function or internal thinking process, this leads to a level of obsessional worry, rumination and self-doubt about feeling trapped in a never-ending cycle of unwanted internal attention. Anxiety about never escaping the problem compounds the level of sensitivity and can lead to overwhelming feelings of distress and hopelessness.

Anxiety about never escaping the problem compounds the level of sensitivity and can lead to overwhelming feelings of distress and hopelessness.

The Compulsive Process

The automatic compulsive response is an attempt to control or avoid the problem. This can include physical and mental checking to see if the sensation feels normal, repeating the process a certain number of times or in a ritualistic way before stopping, attempting to compare the feeling with earlier examples, distracting, avoiding and seeking reassurance.

This fixation with stopping the problem paradoxically increases the individual’s level of overall awareness. Existing anxiety levels are also significantly compounded by the emotional effort that goes into trying to escape the problem.

Sensorimotor OCD follows a similar pattern to Hyperawareness OCD which involves a focus on external sounds and visual stimuli. Whilst there are many common crossovers between these problems, we make a general distinction between the self / internal focus of Sensorimotor OCD and the external focus of Hyperawareness OCD.

We have therefore outlined the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy approach to Sensorimotor OCD on a separate page. You can follow this link to find out more about Sensorimotor OCD

How Sensorimotor OCD is Treated

The recommended treatment for Sensorimotor OCD is Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. The CBT treatment process involves the following psychological interventions:

- Cognitive reappraisal to identify and change negative or unhelpful patterns of thinking.

- Cognitive Defusion and Acceptance techniques to unhook from and normalise unwanted thoughts and feelings.

- Exposure Response Prevention (ERP) to habituate the conditioned or learnt response to the body focused sensation.

- Focus of Attention training to improve attentional skills and develop behavioural agility.

- Mindfulness training to improve present moment awareness and cognitive flexibility.

EMDR Therapy for Sensorimonitor OCD

Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) has also been found to provide an effective treatment for sensorimotor OCD. This clinical protocol can be delivered as a standalone therapy or as a powerful adjunct to Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapy. This should only be delivered by level 3 qualified practitioners with specialist experience in the treatment of OCD.

This clinical protocol can be delivered as a standalone therapy or as a powerful adjunct to Cognitive Behavioural Psychotherapy. This should only be delivered by level 3 qualified practitioners with specialist experience in the treatment of OCD.

Members of Our Team Specialising in Sensorimotor OCD

The following team members are fully qualified CBT specialists, hold professional accreditation with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP) and have direct experience of treating sensory motor OCD:

Jodie Broughton

Adlington, Chorley, PR7

View Profile

Charu Bassi

Charu Bassi, Erith Road, Belvedere, DA17 6EY

View Profile

Paula Reid

Manchester, Stretford, M32

View Profile

Leonie O'Loughlin

School Cottage, Polstead Hill, Polstead, CO6 5AH (Suffolk/Essex border)

View Profile

Cloudette Hancel

30 Monument Green, Weybridge, Surrey, KT13 8NA

View Profile

Roz West

84 The Lakes, Larkfield, Kent, ME20 6GS

View Profile

Derek Barkham

104 St Williams Way, Thorpe Street, Andrew, Norwich, NR7 0AP

View Profile

Hal Satterthwaite

15 Old Bailey, London, EC4M 7EF

View Profile

Elaine Deaves

Elaine Deaves, Field Lane, Litherland, Liverpool, L21 9NF

View Profile

Daniel Roe

Marshgate Drive, Hertford, Hertfordshire, SG13 7JY

View Profile

Victoria Lumley

Crakehall, North Yorkshire

View Profile

Maria Greenan

Radstock, Somerset, BA3

View Profile

Sheelagh Brown

Stockcross, Newbury, RG20

View Profile

Sally Tribe

Poole Bh24

View Profile

Chryssa Chalkia

162-168 Regent St, Soho, London, W1B 5TG

View Profile

Dr Francisco Flores

43a Quarry Hill Road. Tonbridge, TN9 2RS

Tonbridge, TN9 2RS

View Profile

William Phillips

Suite E, 52 High Street, Sevenoaks, TN13 1JG

View Profile

How Many CBT Sessions are Required to Treat Sensorimotor OCD?

The CBT process for Sensorimotor OCD is highly structured and normally requires between eight-twelve sessions of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. This will depend upon the presenting problems and any wider background factors.

Whilst there are counsellors and therapists offering CBT and other therapeutic approaches for Sensorimotor OCD, our advice is to always check the training, qualifications and professional credentials of the therapist before engaging in any form of therapy.

At Think CBT our clinicians are professionally qualified in CBT to a master’s level and have usually completed between four-seven years psychological training to achieve full accreditation with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy (BABCP). The similarly sounding BACP is a counselling organisation and does not professionally accredit CBT specialists.

If you want to talk to a recognised CBT specialist call 01732 808 626, complete the contact form on this page or email [email protected]

International OCD Foundation | When Automatic Bodily Processes Become Conscious: How to Disengage from “Sensorimotor Obsessions”

by David J. Keuler, PhD

Dr. Keuler is a senior clinician at The Behavior Therapy Center of Greater Washington. He is a specialist in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and related conditions and has been in private practice for well over a decade. Comments regarding this article may be directed to [email protected]

This article was initially published in the Fall 2011 edition of the OCD Newsletter.

The literature on obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) routinely includes detailed accounts of washing, checking, repeating, and undoing behaviors associated with fears of harm to oneself or others. Likewise, descriptions of intrusive sexual or violent imagery; urges to touch, tap, or even-up objects; and concerns about good & bad and right & wrong, populate the pages of scientific and self-help books and articles on OCD. Yet for some individuals suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder, there is little hope of “finding themselves” in the pages of this popular literature. Their OCD is somehow different: it simply does not conform to these popular descriptions.

Likewise, descriptions of intrusive sexual or violent imagery; urges to touch, tap, or even-up objects; and concerns about good & bad and right & wrong, populate the pages of scientific and self-help books and articles on OCD. Yet for some individuals suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder, there is little hope of “finding themselves” in the pages of this popular literature. Their OCD is somehow different: it simply does not conform to these popular descriptions.

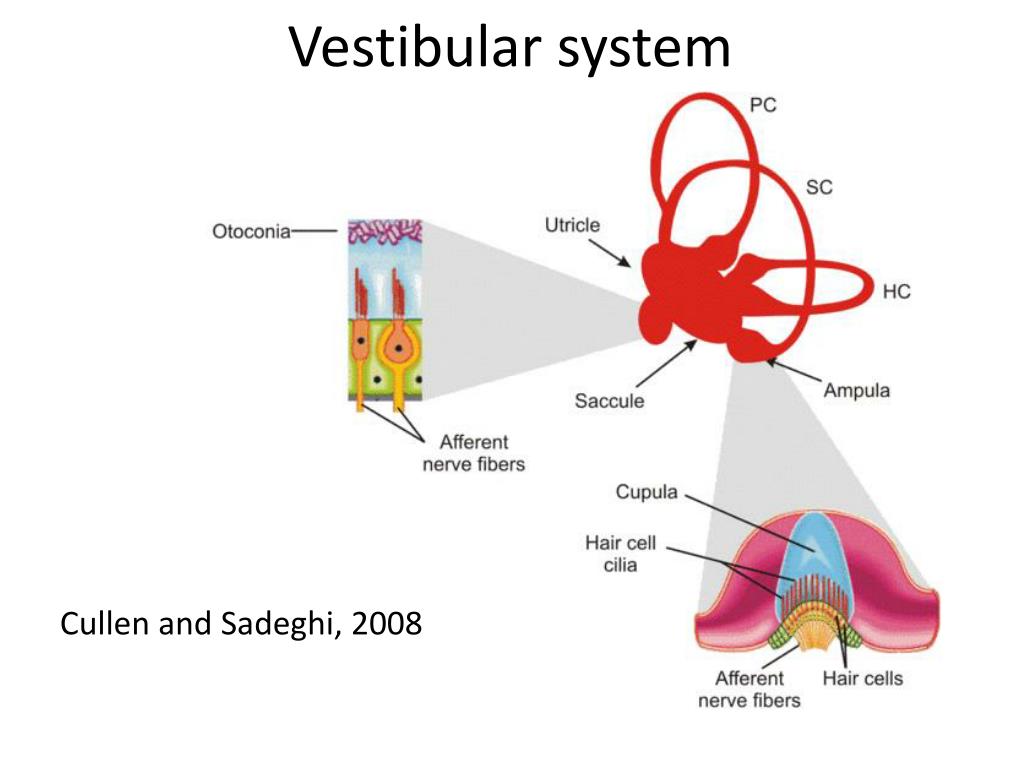

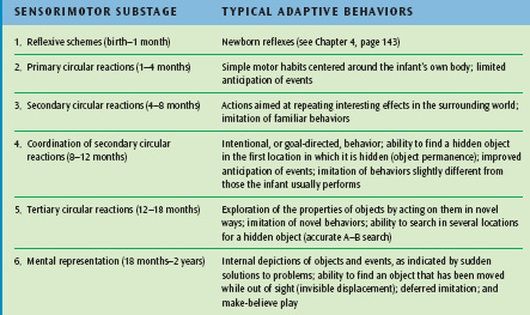

One such neglected subgroup of sufferers report distressing preoccupations with bodily processes or bodily sensations. Colloquially termed “obsessive swallowing,” “obsessive blinking,” or “conscious breathing,” these problems fall within a class of complaints that may be aptly described as “sensorimotor obsessions”. Sensorimotor obsessions as defined here involve either a focus on automatic bodily processes or discrete physical sensations. Whether technically sensory or sensorimotor in nature, such obsessions share one common precursor: selective attention. Any bodily process or sensation to which one selectively attends can form the foundation of this sensory or sensorimotor obsession. In a typical scenario, individuals begin to selectively attend to their swallowing, for example, and become anxious that they will become unable to stop thinking about their swallowing. Attempts to distract themselves fail, leading to higher levels of anxiety. This anxiety perpetuates the focus on swallowing, leaving them preoccupied and frustrated by their unsuccessful attempts to shift attention elsewhere.

Any bodily process or sensation to which one selectively attends can form the foundation of this sensory or sensorimotor obsession. In a typical scenario, individuals begin to selectively attend to their swallowing, for example, and become anxious that they will become unable to stop thinking about their swallowing. Attempts to distract themselves fail, leading to higher levels of anxiety. This anxiety perpetuates the focus on swallowing, leaving them preoccupied and frustrated by their unsuccessful attempts to shift attention elsewhere.

Examples of Common Sensorimotor Obsessions

Sensorimotor obsessions often involve one or more of the following:

- breathing [whether breathing is shallow or deep, or the focus is on some other sensation of breathing]

- blinking [how often one blinks or the physical requirement to blink]

- swallowing/salivation (how frequently one swallows, the amount of salivation produced, or the sensation of swallowing itself)

- movement of the mouth and/or tongue during speech

- pulse/heartbeat (awareness of pulse or heartbeat, particularly at night while trying to fall asleep)

- eye contact (unlike social anxiety-based concerns, this form involves awareness of the eye contact itself or which eye one is looking at when staring into the eyes of another person)

- visual distactions (e.

g. paying attention to “floaters”, the particulate matter that is drifting within the eye that is most visible when staring at a blank wall or awareness of subtle movements of the eyes, such as saccadic eye movements)

g. paying attention to “floaters”, the particulate matter that is drifting within the eye that is most visible when staring at a blank wall or awareness of subtle movements of the eyes, such as saccadic eye movements) - awareness of specific body parts (e.g. perception of the side of one’s nose while trying to read or, as in the cases of a young boy and older man, a hyper-awareness of particular body parts such as their feet or fingers respectively)

Distinguishing Characteristics

Sensorimotor obsessions as defined here rarely involve elaborated fears of harm to oneself or others. Fears center mainly on the concern that automatic bodily processes or physical sensations will fail to return to their previous unconscious state, thus forever “driving the sufferer crazy.” Such fears are frequently accompanied by the broader concern that the obsession itself will be unending, a concern that Dr. Jonathan Grayson has termed “obsessing about obsessing” (Grayson, 2004). Sensorimotor obsessions are infrequently accompanied by perfectionistic attitudes or beliefs; however, they do occasionally play a role, as in the case of a perfectionistic patient who was constantly preoccupied by smudges on his glasses and by other imperfections in his sensory environment. By definition sufferers report significant levels of distress, particularly as a result of impairments in concentration at work, when socializing, or when attempting to fall asleep. Compulsions in response to sensorimotor obsessions are usually limited to repeated attempts to use distraction to interrupt the fixation on sensory phenomena.

Sensorimotor obsessions are infrequently accompanied by perfectionistic attitudes or beliefs; however, they do occasionally play a role, as in the case of a perfectionistic patient who was constantly preoccupied by smudges on his glasses and by other imperfections in his sensory environment. By definition sufferers report significant levels of distress, particularly as a result of impairments in concentration at work, when socializing, or when attempting to fall asleep. Compulsions in response to sensorimotor obsessions are usually limited to repeated attempts to use distraction to interrupt the fixation on sensory phenomena.

Most people at some point in their lives have experienced transient problems with this sort of sensory hyper-awareness. Stuffy noses, irritated eyes, rashes, coughing and the like represent the normal sensory annoyances that can come to preoccupy individuals for short periods of time. For some less fortunate individuals, their chronic allergies, pain syndromes, and other medical problems cause sustained interruptions to selective attention. However, for a minority of sufferers, their awareness of sensorimotor phenomena elicits anxiety and preoccupation severe enough to warrant a clinical diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder or an obsessive-compulsive spectrum condition.

However, for a minority of sufferers, their awareness of sensorimotor phenomena elicits anxiety and preoccupation severe enough to warrant a clinical diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder or an obsessive-compulsive spectrum condition.

Relationship of Sensorimotor Obsessions to Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Conditions

Anecdotal evidence suggests that sufferers diagnosed with this type of sensorimotor OCD are also more likely to have current or past difficulties with other, more common variants of obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, or panic disorder. This reflects the fact that problems with sensory hyper-awareness are not confined to a particular diagnostic entity (such as OCD), but cut across a number of obsessive-compulsive spectrum conditions. For example, individuals with bowel or bladder preoccupations, hypochondriasis (health anxiety), and panic disorder report not only sensory hyper-awareness (such as fullness of the bladder, acute physical symptoms, or rapid heart rate) but also cognitive embellishments that involve specific, catastrophic fears (such as humiliating bowel accidents, serious illness, or having a heart attack).

Currently, individuals who suffer from the relatively unelaborated sensorimotor preoccupations as described in this article are routinely diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Individuals who suffer from elaborated catastrophic fears associated with their sensorimotor preoccupations tend to be diagnosed according to the content of those fears (e.g. a focus on heart rate that leads to fears of a heart attack is diagnosed as panic disorder). Future research will ultimately determine whether sensormotor preoccupations that occur within various clinical diagnostic categories reflect the same or unrelated neurobiological processes.

Treatment of Sensorimotor Obsessions

Sensorimotor obsessions can be treated quite successfully by decoupling any sensory awareness with reactive anxiety. In other words, sufferers must ultimately experience their sensory hyperawareness without any resulting anxiety. Anxiety, as is the case in other forms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, serves as the glue that binds particular thoughts to conscious awareness. Once a thought is linked with anxiety, the conscious mind keeps it ever present. This occurs because anxiety is part of the brain’s alarm system for danger. The mind clearly does not want us to forget about any danger that may be lurking around. If a particular idea scares us, we tend to think about it over and over. In sensorimotor obsessions, sufferers repeatedly attempt to shift their attention for fear that their sensory focus will become “stuck” and they will not be able to concentrate fully on the task at hand. Here, the thought that “I’m never going to stop thinking about this” leads to immediate fears of impaired functioning. As a result of the pairing between this thought and a feared outcome, the mind holds on tightly to the very awareness that the sufferer is attempting to rid. In many ways this is much like “white bear syndrome,” where attempts by individuals to think about anything other than a white bear lead to many more thoughts of white bears (Wegner, 1989).

Once a thought is linked with anxiety, the conscious mind keeps it ever present. This occurs because anxiety is part of the brain’s alarm system for danger. The mind clearly does not want us to forget about any danger that may be lurking around. If a particular idea scares us, we tend to think about it over and over. In sensorimotor obsessions, sufferers repeatedly attempt to shift their attention for fear that their sensory focus will become “stuck” and they will not be able to concentrate fully on the task at hand. Here, the thought that “I’m never going to stop thinking about this” leads to immediate fears of impaired functioning. As a result of the pairing between this thought and a feared outcome, the mind holds on tightly to the very awareness that the sufferer is attempting to rid. In many ways this is much like “white bear syndrome,” where attempts by individuals to think about anything other than a white bear lead to many more thoughts of white bears (Wegner, 1989).

In order to disengage from sensorimotor obsessions, sufferers must learn “the art of self-awareness.” Sufferers must learn how to invite in the sensory awareness with a relaxed and accepting posture, very much like the focus on diaphragmatic breathing during mediation.

Psychoeducation

The first stage of treatment focuses on teaching patients that selective attention to previously automatic or unconscious bodily processes or sensations is not dangerous in and of itself. Patients are reassured that once their anxiety dissipates, the sensory awareness will shift. This reassurance often sets the stage for “inviting in” the sensations as a means of reducing anxiety.

Exposure and Response Prevention

In short, sensorimotor obsessions can be outsmarted by voluntarily paying attention to the relevant bodily process or sensation. Patients are instructed to allow the sensation to be present and to invite in any such awareness (exposure) with a casual, dispassionate focus. By purposely focusing on the sensations (exposure), patients stop relying on distraction (response prevention) as the tool for reducing anxiety. Repeated voluntary exposure to the sensations leads to diminished anxiety as patients grow accustomed to embracing any awareness without attempts to avoid or escape it. Imaginal exposure to particular feared outcomes (e.g. “my life will be ruined,” “I’ll never have peace of mind,” “I’ll never be able to get rid of this problem,” or “this obsession will never go way”) may be employed to enhance exposure. Additionally, patients may be asked to invite in the sensations and accompanying fears throughout the day. This is accomplished by having patients place reminders (such as Post-It notes or stickers) at home, in the car, and at work. These reminders help to cue patients to engage in repeated exposures throughout the day, thus increasing the likelihood of successful habituation.

By purposely focusing on the sensations (exposure), patients stop relying on distraction (response prevention) as the tool for reducing anxiety. Repeated voluntary exposure to the sensations leads to diminished anxiety as patients grow accustomed to embracing any awareness without attempts to avoid or escape it. Imaginal exposure to particular feared outcomes (e.g. “my life will be ruined,” “I’ll never have peace of mind,” “I’ll never be able to get rid of this problem,” or “this obsession will never go way”) may be employed to enhance exposure. Additionally, patients may be asked to invite in the sensations and accompanying fears throughout the day. This is accomplished by having patients place reminders (such as Post-It notes or stickers) at home, in the car, and at work. These reminders help to cue patients to engage in repeated exposures throughout the day, thus increasing the likelihood of successful habituation.

Body Scan and Mindfulness

Patients are frequently unaware of the changes in perception that occur when selectively attending to their bodies. These changes in awareness can be frightening, as they may represent an uncomfortable and disquieting level of awareness to previously unconscious bodily processes. Patients tend to believe that they must purposely shift attention away from these unusual or previously unnoticed sensations in order to restore them to their unconscious state. Participation in a body scan can help patients fluidly move in and out of their awareness of these sensations without resorting to forced attempts.

These changes in awareness can be frightening, as they may represent an uncomfortable and disquieting level of awareness to previously unconscious bodily processes. Patients tend to believe that they must purposely shift attention away from these unusual or previously unnoticed sensations in order to restore them to their unconscious state. Participation in a body scan can help patients fluidly move in and out of their awareness of these sensations without resorting to forced attempts.

A body scan involves shifting attention to various bodily processes or sensations for prescribed periods of time. Patients are instructed to close their eyes and selectively attend to their feet, for example, until they acquire full sensory awareness. Once this occurs, they can next move to their calves, stomach, upper body, arms, head, or any particular sensorimotor process (such as breathing). Patients learn that they can move gently from one sensation to another without getting “stuck” by focusing and refocusing in the absence of anxiety, apprehension, or active attempts to force a shifting in awareness.

Mindfulness, the art of paying close attention to an experience in the absence of criticism, judgment, or defensiveness, can also play an important role. As stated earlier, eastern meditative practices in mindfulness often involve choosing certain bodily processes to be the focus of meditative practice (e.g. breathing, the rise and fall of the chest or stomach, sensations of air through the nostrils). Patients are instructed to allow their particular sensory preoccupation to become their meditative focus; they are to accept all sensations without criticism or judgment, and observe any sensations with curiosity and interest. Over time patients begin to experience a fading of sensory awareness (or much greater tolerance of it) as their anxiety diminishes and their willingness to invite in the sensations grows.

Conclusion

Sensorimotor obsessions likely affect countless thousands of individuals each year. Future research is necessary to determine how prevalent the problem is and how best to treat it. Until such systematic research is conducted, we are left with case studies and anecdotal evidence that suggests that sensorimotor obsessions are best dealt with within a cognitive-behavioral framework. Psychoeducation, cognitive reframing, reassurance, exposure and response prevention, and certain mindfulness and acceptance techniques can all play important roles in diminishing the frustration and distress associated with this maddening and at times incapacitating experience.

Until such systematic research is conducted, we are left with case studies and anecdotal evidence that suggests that sensorimotor obsessions are best dealt with within a cognitive-behavioral framework. Psychoeducation, cognitive reframing, reassurance, exposure and response prevention, and certain mindfulness and acceptance techniques can all play important roles in diminishing the frustration and distress associated with this maddening and at times incapacitating experience.

References

- Grayson, J. (2004). Freedom from obsessive-compulsive disorder: A personalized recovery program for living with uncertainty. New York: Berkley Publishing Group.

- Wegner, D. (1989). White Bears and other unwanted thoughts: Suppression, obsession, and the psychology of mental control. New York: Penguin/Viking.

The effectiveness of the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder was predicted by MRI

American scientists were able to predict the effectiveness of psychotherapy in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. This was done thanks to the analysis of the functional connections of the brain of patients during fMRI at rest. The results of the work are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

This was done thanks to the analysis of the functional connections of the brain of patients during fMRI at rest. The results of the work are published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences .

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) often has obsessive or frightening thoughts (obsessions), which are helped by a kind of “rituals” (compulsions) - certain actions, such as washing hands or counting objects around or actions performed.

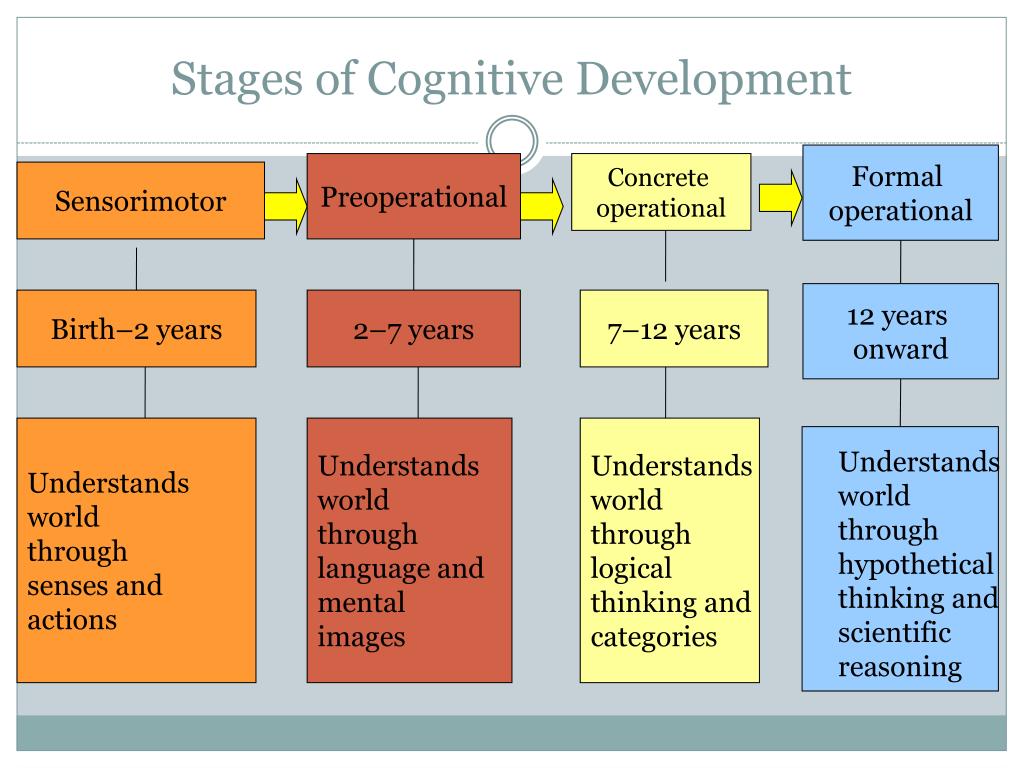

One of the treatments for OCD is cognitive behavioral therapy. The method is based on identifying the causes of mental states, their analysis by the patient together with a specialist, as well as positive reinforcement of positive patterns of behavior. However, psychotherapy is time consuming and costly and not always equally effective, so a method of accurately predicting its benefits is needed.

Scientists led by Jamie D. Feusner of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California at Los Angeles proposed to predict the effectiveness of treatment of OCD using cognitive behavioral therapy by analyzing neuroimaging data. Their study involved 42 people aged 18 to 60 with diagnosed OCD.

Their study involved 42 people aged 18 to 60 with diagnosed OCD.

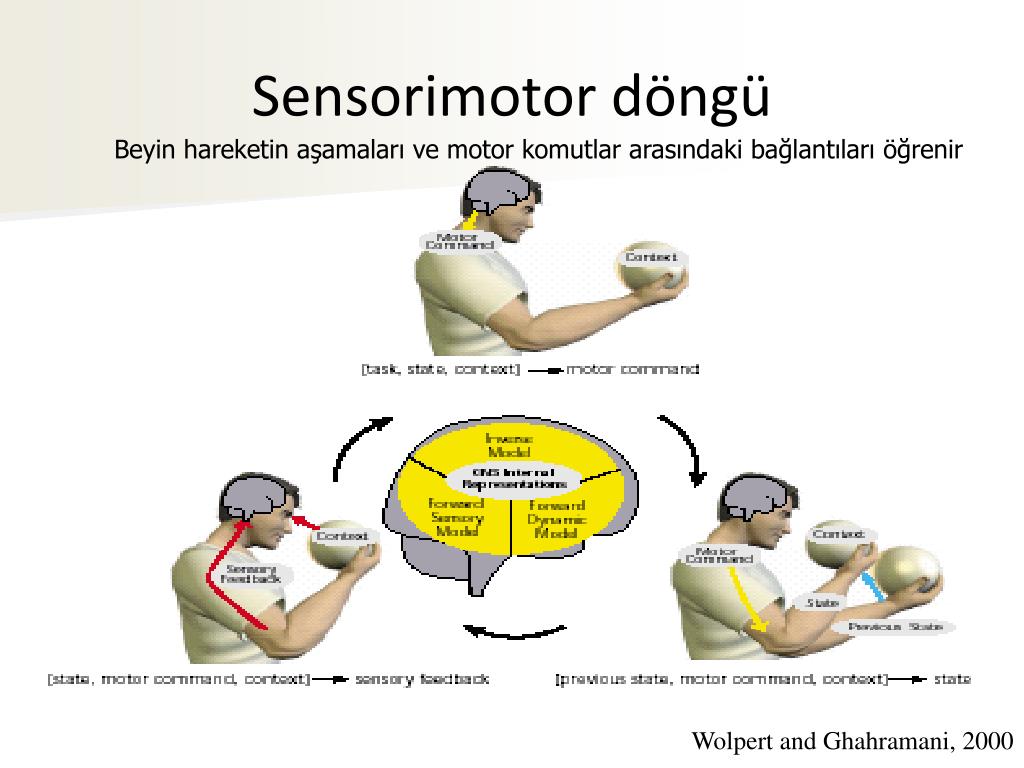

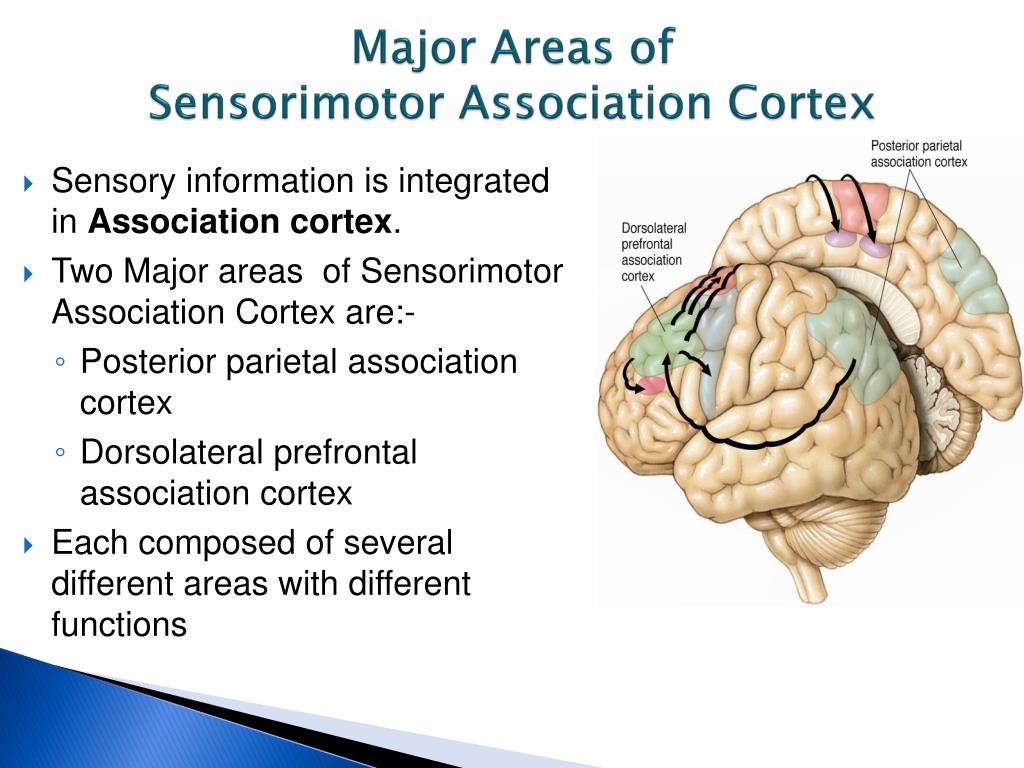

Participants received daily CBT for OCD for four weeks. An analysis of the functional connections of the brain was carried out before and after treatment using fMRI at rest. First of all, scientists were interested in the neural connections of the visual and sensorimotor systems, as well as the dorsal and ventral neural connections responsible for attention, and the network of the passive mode of the brain - a violation of their work is associated with the development of the disorder. Prior to the start of treatment, 21 people were on the so-called "waiting list" for four weeks. At this time, they did not undergo psychotherapy - the fMRI data obtained before and after the waiting time were used as a control condition.

Based on data on the integrity and activity of the studied neuronal connections before treatment, as well as information on the severity of OCD, the use of medications aimed at treating it, and demographic data, scientists identified a list of properties that characterize the presence of the disease in 32 participants. These data were then correlated with treatment outcomes, both fMRI data and measures of OCD symptom severity. The remaining ten were used for divination.

These data were then correlated with treatment outcomes, both fMRI data and measures of OCD symptom severity. The remaining ten were used for divination.

It has been found that up to 67 percent of differences in treatment efficacy can be predicted from the integrity of functional relationships prior to treatment. The most revealing markers were the functional connection within the network of the passive mode of the brain (it is responsible for the activity of the brain at rest) and the visual system.

Scientists note that the results can be used to find effective ways to treat OCD. For example, in the event that the introduction of cognitive behavioral therapy would be incompatible with the functional integrity of the patient's brain, one should consider, for example, drug therapies or test the effectiveness of another type of psychotherapy.

By analyzing the functional connections of the brain, one can predict the individual abilities of people: for example, to determine whether he can learn a second language, and how well he will do it.

Elizaveta Ivtushok

Found a typo? Select the fragment and press Ctrl+Enter.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Treatment

Great Thought is an obsessive compulsive disorder treatment program. We will relieve you of obsessive thoughts, movements and rituals. Let's get back to life!

Symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Frightening images and drives

- Compulsive acts (rituals)

- Obsessive check of own actions

- Fear of trouble, pollution or contamination

- Inexplicable desire to count something

- Excessive organization and pedantry

- Perfectionism in relationships, work and even leisure

- "Stuck", "looping" on one's thoughts

You feel that over time your mood becomes worse: apathy, depression, obsessions increase, and rituals begin to fill all your free time or harm your physical health.

You may have had more than one meeting with psychologists, psychotherapists and psychiatrists. You are not given the "scary" psychiatric diagnoses of Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder, but are prescribed medication and psychotherapy nonetheless. However, such treatment cannot be called effective - the symptoms persist and only aggressive pharmacotherapy temporarily reduces anxiety.

You are not given the "scary" psychiatric diagnoses of Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder, but are prescribed medication and psychotherapy nonetheless. However, such treatment cannot be called effective - the symptoms persist and only aggressive pharmacotherapy temporarily reduces anxiety.

What is obsessive-compulsive disorder?

Obsessive-compulsive disorder is a syndrome characterized by the presence of obsessive thoughts (obsessions) to which a person reacts with certain actions (compulsions). The causes of the disorder are rarely superficial. The syndrome is also accompanied by the development of obsessive memories and various pathological phobias. May be chronic, episodic or progressive.

Obsession - obsessive thought, persistent desire for something, uncontrollable and accompanied by anxiety and intense anxiety. In an attempt to cope with such thoughts, a person resorts to committing compulsions.

Compulsion - an irresistible need to perform certain actions (rituals), which can be assessed by the person himself as irrational or meaningless, and the internal need to perform them is forced and is the result of obsessive ideas.

Common examples of OCD

- An exaggerated sense of danger. Fear of the materiality of thoughts:

- "now I will lose control and hurt my loved ones"

- "something terrible is about to happen, I can feel it"

- "I shouldn't think like that, all this will come true because of me"

- Pathological fear of pollution. Thirst for Purity

- Excessive perfectionism, exaggerated responsibility - "everything must be done perfectly", "everything depends on me, mistakes are unacceptable"

How does this painful algorithm work?

Most people have unwanted or obsessive thoughts quite often, but all sufferers of the disorder greatly exaggerate their importance. Fear of one's own thoughts leads to attempts to neutralize the negative feelings that arise from obsessions, for example by avoiding thought-provoking situations or by engaging in "rituals" of excessive self-cleansing or prayer.

As we noted earlier, repetitive avoidance behavior can "get stuck", "loop", that is, have a tendency to repeat. The cause of obsessive-compulsive disorder is the interpretation of intrusive thoughts as catastrophic and true.

The cause of obsessive-compulsive disorder is the interpretation of intrusive thoughts as catastrophic and true.

If you experience periodically over the years:

- Constant or fluctuating anxiety

- The need to perform certain ritualized actions

- Persistent decline in quality of life due to the need to avoid certain thoughts and actions, places and events

And you are also persecuted:

- Significant problems in studies and career

- Failure to establish a serious relationship

- Constant criticism and pressure from relatives

- Lots of senseless activities

- Excessive involvement in computer games and the Internet, alcohol

- Loneliness and isolation

We strongly recommend that you do not delay seeking help and that you complete a remedial program. Consultations and psychotherapeutic sessions according to the program are held several times a week, until the relief of severe symptoms, then the frequency of meetings with specialists is reduced to 2–3 per month.

Count on the fact that in the end we will deal with your problem together.

Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in Neuro-Psi

Every day, the specialists of the NEURO-PSI clinic analyze the world practice in the field of psychiatry and psychotherapy. The goal is the impartial selection and implementation of those methods of treatment and psychological assistance, the effectiveness of which has been convincingly proven in independent studies.

We are guided by the principles of evidence-based medicine and use as a basic method of treatment a psychotherapeutic paradigm, the effectiveness of which has been widely recognized by the professional community.

1. What is the essence of the obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment program

Since obsessive thoughts, rituals and conditions are only symptoms of mental dysfunction, the root cause must be treated in order to achieve a stable result. A comprehensive work is carried out with the client, taking into account the main factors that create well-being.

The main emphasis is on teaching the client how to properly respond to his thoughts, emotions, inner feelings and interpretation of external events.

All types of psychotherapeutic and drug treatments serve the same goal: to achieve the best result in the shortest possible time. At the same time, by coordinating the efforts of specialists in various fields, the most complete coverage of all types of mental illnesses, disorders and disorders is possible.

2. What treatments are used

- Priority:

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy.

- Schema Therapy.

- Reality Therapy.

- Choice Theory.

- Rational pharmacotherapy.

- Psychopharmacotherapy (if indicated)

- Biofeedback Therapy

- Rational psychocorrection of stress

- Jacobson progressive muscle relaxation.

- Traditional and modern gymnastic systems, relaxation techniques.

- Breathing techniques .

- Stress exposure.

- Training in self-control.

- Lifestyle modification

- Working with bad habits.

- Correction of the diet.

- Professional and social adaptation.

3. How is the treatment under the program

Each treatment program at the NEURO-PSI clinic consists of four stages:

- diagnostics,

- work with disease symptoms,

- work with the causes of the disease,

- consolidation of the achieved results.

Work efficiency is increased by dividing the treatment process into a predetermined number of sessions, at a convenient time and without hospitalization. This means that each program is adapted to the problem that the client has addressed.

The program method of treatment is predictable, time-limited, productive, and, most importantly, understandable for the client.

Of course, the treatment takes place in a comfortable mode without interruption from work, study or family. Specialists of various profiles will work with you (team method). This is necessary to minimize the risk of diagnostic errors that could lead to the adoption of a suboptimal treatment plan.

Specialists of various profiles will work with you (team method). This is necessary to minimize the risk of diagnostic errors that could lead to the adoption of a suboptimal treatment plan.

Improvements in well-being and mood (healing) occur in stages: after the decrease in emotional problems, bodily symptoms decrease. Working with the causes (etiology) of obsessive-compulsive disorder helps to avoid relapses in the future.

4. What are the results and prognosis?

Upon completion of the program, you get rid of obsessive thoughts and rituals, fear of pollution, unmotivated fears, panic attacks and multiple vegetative symptoms (sudden jumps in blood pressure, rapid heartbeat, dizziness, nausea).

According to statistics, the effectiveness of the methods used approaches 100% if all recommendations of specialists are followed.

Skills you acquire during the program:

- self-control and self-regulation

- constructive body analysis

- understanding one's own mental and emotional sphere

- ability to control one's attention

- ability to act consciously in stressful situations

Significantly improves the emotional and physical condition, gaining self-confidence, in the future.