Safety contract mental health

The Suicidal Client: Contracting for Safety

One of my colleagues angrily shared a story about a friend of hers. The friends father had been despondent ever since his wife died a few months ago. He told his daughter that it would be better if he just ended it all and joined his wife.

The daughter was sufficiently alarmed to take him to the local emergency room. There, he was interviewed and asked to sign a Contract for Safety, promising that he wouldnt harm himself. He sighed. He signed. And he was sent home.

His daughter was beside herself: Of course he signed the thing, she told my colleague. He knew if he refused hed be admitted and he didnt want to give up the option. So what was I supposed to do?

Fortunately, this story has a positive ending. The daughter was able to persuade her father to go to a therapist. The therapist was experienced and kind and, possibly because he was about the same age, able to connect with a 70-year-old depressed man who was grieving.

But the story is a good illustration of the limitations of the often used Contract for Safety.

Whats Wrong with a Contract for Safety?

Results of Contracts for Safety (CFS), where a client is asked to agree either verbally or in writing that she will not engage in self harm, were first published by Drye, et.al. in 1973 . Although these original authors only investigated its effectiveness with patients in a long term relationship with their therapist, the use of the tool has since become standard practice for many crisis teams and clinicians, even during an initial interview. But are they effective?

A careful review of the literature by Kelly and Knudson at Idaho State Universitys Institute of Rural Health in 2000 showed that no studies demonstrate that contracts are an effective way to prevent suicide .

A 2001 study by B.L. Drew found that of people who attempted suicide in a psychiatric hospital, 65% had signed a CFS . In still another study, this one a 2000 survey of psychiatrists in Minnesota by Dr. Jerome Kroll, 40% had a patient make a serious or successful suicide attempt after signing a CFS.

Jerome Kroll, 40% had a patient make a serious or successful suicide attempt after signing a CFS.

Contracts for Safety have not been found to be useful with suicidal patients who are psychotic, impulsive, depressed or agitated, who have a personality disorder or who are under the influence of alcohol or street drugs the very patients who are the most likely to show up in emergency rooms.

In fact, there is even some evidence that for people diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder, a CFS may make things worse.

There are a number of reasons why clinicians continue to use Contracts for Safety, despite the evidence that when used alone, they may not be helpful and, in some cases, may even be harmful.

First, most clinicians receive limited training in suicidality. The use of the Contract for Safety has become almost folkloric. Confronted with a suicidal client, the clinician may have heard that such a contract is helpful. Doing something, even something that may be ineffective, feels better than doing nothing.

Secondly, some clinicians seem to think that the use and documentation of a CFS protects them from legal liability if the client does commit suicide

Studies have shown, however, that having a CFS does not decrease a clinicians liability. Thirdly, some clinicians think they can relax a bit if they have a contract. They mistakenly believe that having the contract buys them some time to help the client abandon suicide as a solution to his problems.

Finally, a severely mentally ill or intellectually disabled or addicted client may be in no shape to make a contract that represents an informed, responsible decision.

If Not a Contract for Safety, What?

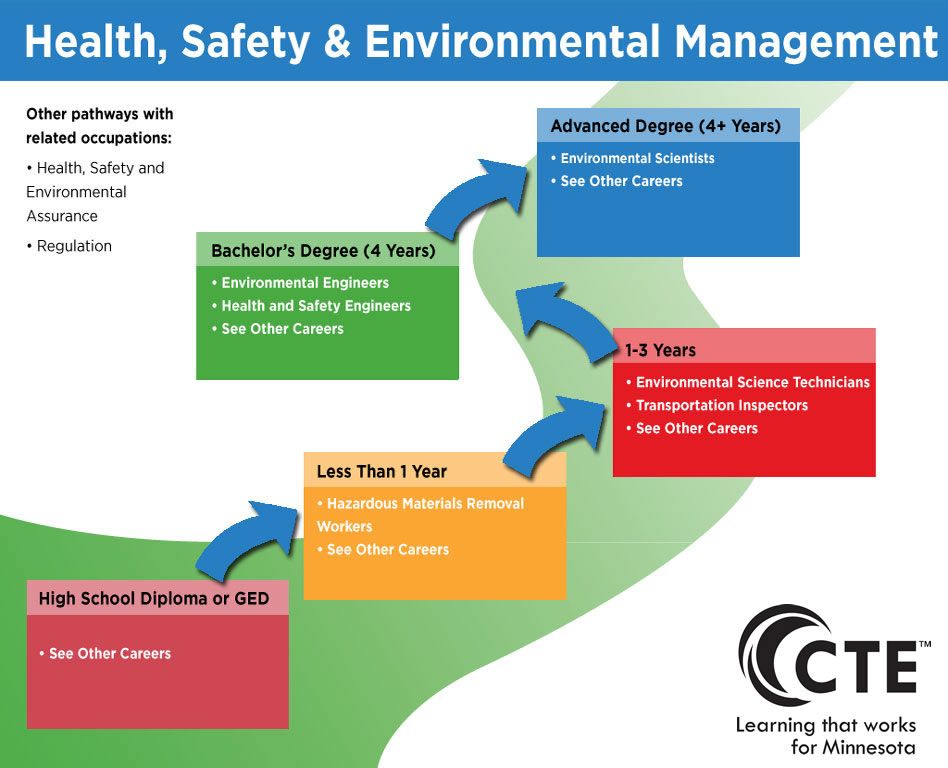

Obtain training: There are other, more effective responses to the threat of suicide than the Contract for Safety. But in order for any of them to be maximally effective, the clinician must develop his or her own expertise. (See related article). Few graduate and professional programs offer adequate training to new clinicians. If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

Develop the therapeutic relationship: Limit use of a Contract for Safety to clients with whom you have a long-term solid relationship: In such cases, the contract can be a useful way to open a conversation about their intentions and feelings.

It can be a relief to a long term client that you are taking her despair seriously and that you care enough to explore whether such an agreement would be helpful. When the client is in crisis, consider increasing the frequency of sessions or other types of contact.

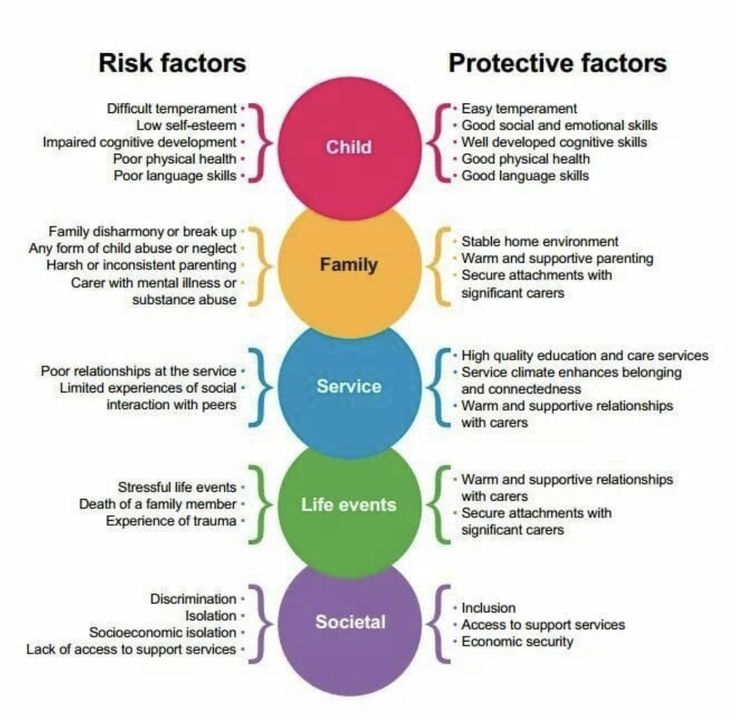

Use the contract only as a part of a full risk assessment: A comprehensive risk assessment includes an evaluation of risk factors, an understanding of what has precipitated suicidal thinking, assessment of the individuals plan and access to means, investigation of any history of past attempts and identification of resiliency factors and potential supports.

Assess regularly: Risk assessment is a dynamic process and should be done regularly with clients who present with or have a history of suicidality or self-harm.

Take time to review risk whenever there is a change in presentation, if symptoms persist or get worse, if medications are changed or if the client talks about terminating.

Periodically utilize a tool like the Beck Depression Scale to check for progress with depressed clients. Regularly do a Mental Status Exam. Be sure to assess the client for delusions, hallucinations, a thought disorder or a decrease in capacity for reality testing.

Develop a Safety Plan with your client. A Safety Plan differs from a Contract for Safety in several important ways. Such a plan focuses on what the client will do to keep himself safe rather than what he wont do to harm himself.

- Help the client identify her own triggers and situations that put her at greatest risk.

- Work with the client to list and practice whatever coping skills he has available.

- Determine if the client has access to guns, potentially lethal medications or any other means for hurting herself. Ask/insist that the client give such items to a trusted friend or relative.

- Ask the client to permit you to contact family members or other trusted individuals who can be helpful in getting her through a crisis. If possible, involve those individuals in some of the clients sessions to clarify whether they are willing to accept a supportive role and what they can do that is the most helpful for this individual. For example: Do they just need to talk the person through on the phone or do they need to take the person to the hospital?

- Identify other sources of support such as the local crisis team, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the local NAMI group. Write down the phone numbers and ask the client to keep them with him.

- Collaborate. If a client becomes suicidal, get a release to talk to the prescriber and to collaborate with the local crisis team. With the clients permission, involve the family (see above). Increase your own supervision.

The Contract for Safety has become too much a part of the routine for clinicians when confronted with the suicidal client.

Although it was created as an assessment tool for use with clients who have a relationship with their therapist, it is too often the immediate and only response to suicidality. Clinical decisions regarding risk require a much more thorough and complex assessment of the individual. When there is clinical concern about the clients safety, it is a safety plan, not a contract, that is most likely to result in positive outcomes.

Healthcare form photo available from Shutterstock

The Suicidal Client: Contracting for Safety

One of my colleagues angrily shared a story about a friend of hers. The friends father had been despondent ever since his wife died a few months ago. He told his daughter that it would be better if he just ended it all and joined his wife.

The daughter was sufficiently alarmed to take him to the local emergency room. There, he was interviewed and asked to sign a Contract for Safety, promising that he wouldnt harm himself. He sighed. He signed. And he was sent home.

He signed. And he was sent home.

His daughter was beside herself: Of course he signed the thing, she told my colleague. He knew if he refused hed be admitted and he didnt want to give up the option. So what was I supposed to do?

Fortunately, this story has a positive ending. The daughter was able to persuade her father to go to a therapist. The therapist was experienced and kind and, possibly because he was about the same age, able to connect with a 70-year-old depressed man who was grieving. But the story is a good illustration of the limitations of the often used Contract for Safety.

Whats Wrong with a Contract for Safety?

Results of Contracts for Safety (CFS), where a client is asked to agree either verbally or in writing that she will not engage in self harm, were first published by Drye, et.al. in 1973 . Although these original authors only investigated its effectiveness with patients in a long term relationship with their therapist, the use of the tool has since become standard practice for many crisis teams and clinicians, even during an initial interview. But are they effective?

But are they effective?

A careful review of the literature by Kelly and Knudson at Idaho State Universitys Institute of Rural Health in 2000 showed that no studies demonstrate that contracts are an effective way to prevent suicide .

A 2001 study by B.L. Drew found that of people who attempted suicide in a psychiatric hospital, 65% had signed a CFS . In still another study, this one a 2000 survey of psychiatrists in Minnesota by Dr. Jerome Kroll, 40% had a patient make a serious or successful suicide attempt after signing a CFS.

Contracts for Safety have not been found to be useful with suicidal patients who are psychotic, impulsive, depressed or agitated, who have a personality disorder or who are under the influence of alcohol or street drugs the very patients who are the most likely to show up in emergency rooms.

In fact, there is even some evidence that for people diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder, a CFS may make things worse.

There are a number of reasons why clinicians continue to use Contracts for Safety, despite the evidence that when used alone, they may not be helpful and, in some cases, may even be harmful.

First, most clinicians receive limited training in suicidality. The use of the Contract for Safety has become almost folkloric. Confronted with a suicidal client, the clinician may have heard that such a contract is helpful. Doing something, even something that may be ineffective, feels better than doing nothing.

Secondly, some clinicians seem to think that the use and documentation of a CFS protects them from legal liability if the client does commit suicide

Studies have shown, however, that having a CFS does not decrease a clinicians liability. Thirdly, some clinicians think they can relax a bit if they have a contract. They mistakenly believe that having the contract buys them some time to help the client abandon suicide as a solution to his problems.

Finally, a severely mentally ill or intellectually disabled or addicted client may be in no shape to make a contract that represents an informed, responsible decision.

If Not a Contract for Safety, What?

Obtain training: There are other, more effective responses to the threat of suicide than the Contract for Safety. But in order for any of them to be maximally effective, the clinician must develop his or her own expertise. (See related article). Few graduate and professional programs offer adequate training to new clinicians. If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

But in order for any of them to be maximally effective, the clinician must develop his or her own expertise. (See related article). Few graduate and professional programs offer adequate training to new clinicians. If you are among those who never received such training, its essential to fill in that gap.

Develop the therapeutic relationship: Limit use of a Contract for Safety to clients with whom you have a long-term solid relationship: In such cases, the contract can be a useful way to open a conversation about their intentions and feelings.

It can be a relief to a long term client that you are taking her despair seriously and that you care enough to explore whether such an agreement would be helpful. When the client is in crisis, consider increasing the frequency of sessions or other types of contact.

Use the contract only as a part of a full risk assessment: A comprehensive risk assessment includes an evaluation of risk factors, an understanding of what has precipitated suicidal thinking, assessment of the individuals plan and access to means, investigation of any history of past attempts and identification of resiliency factors and potential supports.

Assess regularly: Risk assessment is a dynamic process and should be done regularly with clients who present with or have a history of suicidality or self-harm.

Take time to review risk whenever there is a change in presentation, if symptoms persist or get worse, if medications are changed or if the client talks about terminating.

Periodically utilize a tool like the Beck Depression Scale to check for progress with depressed clients. Regularly do a Mental Status Exam. Be sure to assess the client for delusions, hallucinations, a thought disorder or a decrease in capacity for reality testing.

Develop a Safety Plan with your client. A Safety Plan differs from a Contract for Safety in several important ways. Such a plan focuses on what the client will do to keep himself safe rather than what he wont do to harm himself.

- Help the client identify her own triggers and situations that put her at greatest risk.

- Work with the client to list and practice whatever coping skills he has available.

- Determine if the client has access to guns, potentially lethal medications or any other means for hurting herself. Ask/insist that the client give such items to a trusted friend or relative.

- Ask the client to permit you to contact family members or other trusted individuals who can be helpful in getting her through a crisis. If possible, involve those individuals in some of the clients sessions to clarify whether they are willing to accept a supportive role and what they can do that is the most helpful for this individual. For example: Do they just need to talk the person through on the phone or do they need to take the person to the hospital?

- Identify other sources of support such as the local crisis team, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline or the local NAMI group. Write down the phone numbers and ask the client to keep them with him.

- Collaborate. If a client becomes suicidal, get a release to talk to the prescriber and to collaborate with the local crisis team.

With the clients permission, involve the family (see above). Increase your own supervision.

With the clients permission, involve the family (see above). Increase your own supervision.

The Contract for Safety has become too much a part of the routine for clinicians when confronted with the suicidal client.

Although it was created as an assessment tool for use with clients who have a relationship with their therapist, it is too often the immediate and only response to suicidality. Clinical decisions regarding risk require a much more thorough and complex assessment of the individual. When there is clinical concern about the clients safety, it is a safety plan, not a contract, that is most likely to result in positive outcomes.

Healthcare form photo available from Shutterstock

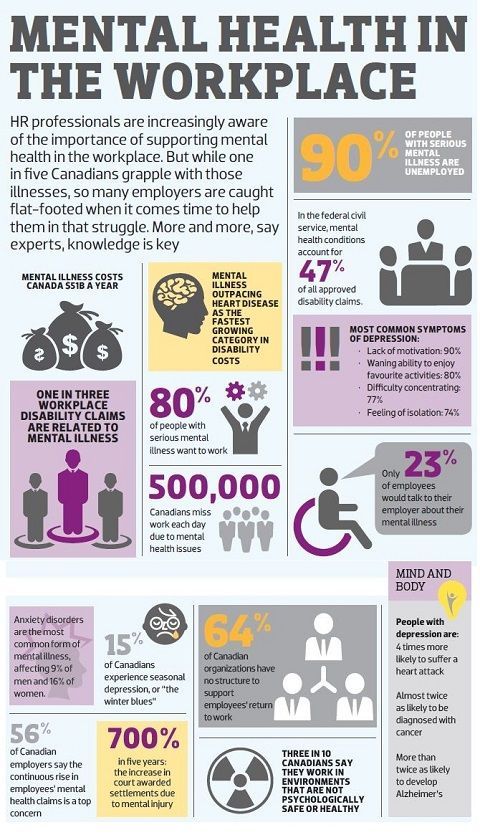

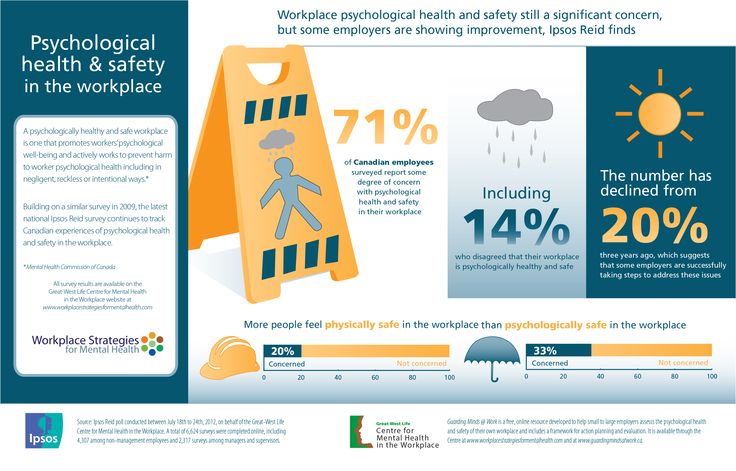

Workplace mental health

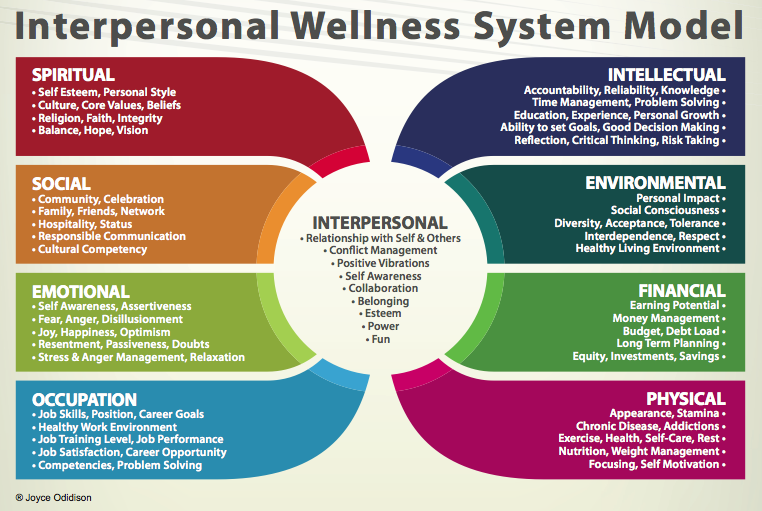

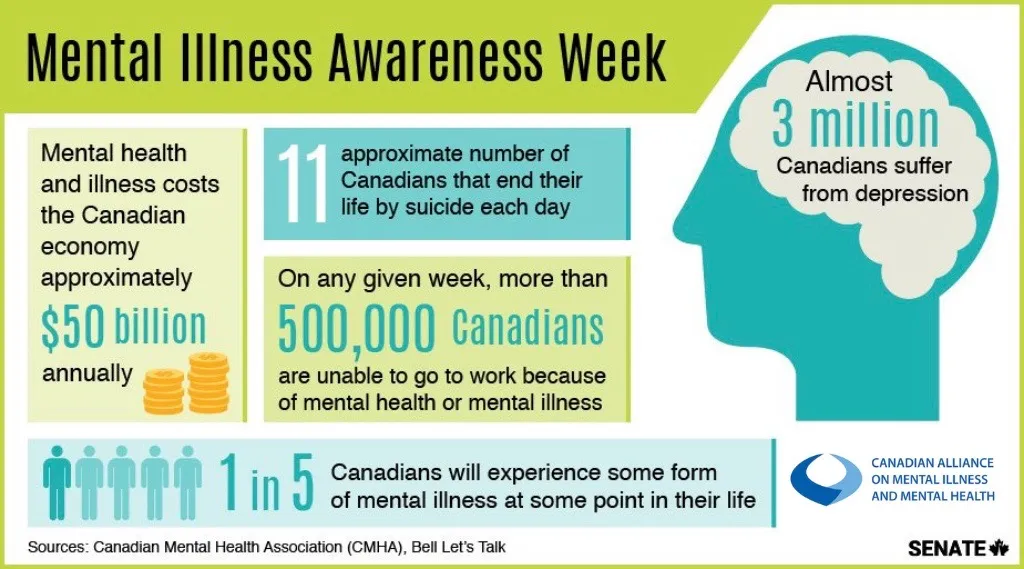

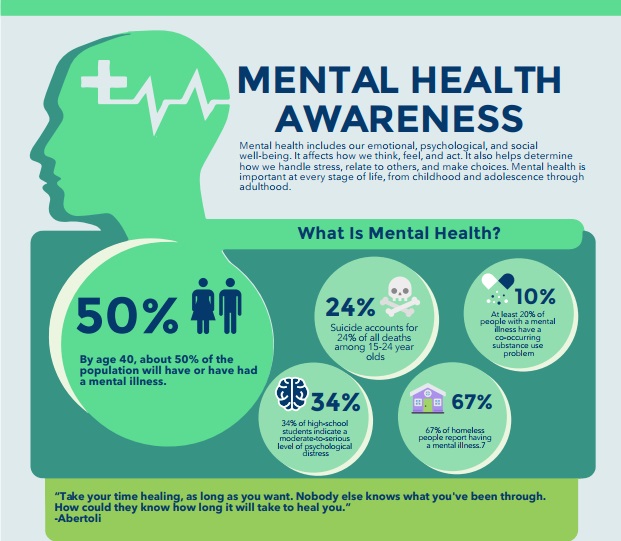

Worldwide, over 300 million people suffer from depression, the leading cause of disability, and some of these people also suffer from symptoms of anxiety. According to a recent WHO-led study, depression and anxiety-related productivity losses are estimated to cost the global economy US$1 trillion annually.

Unemployment is a well-known risk factor for mental health problems, while returning to or starting work is a protective factor. Unfavorable working conditions can lead to physical and mental health problems, alcohol or substance abuse, absenteeism and reduced productivity. nine0003

Creating a mental health-friendly working environment that is supportive of people with mental health problems is likely to reduce absenteeism, increase productivity, and in turn generate economic returns.

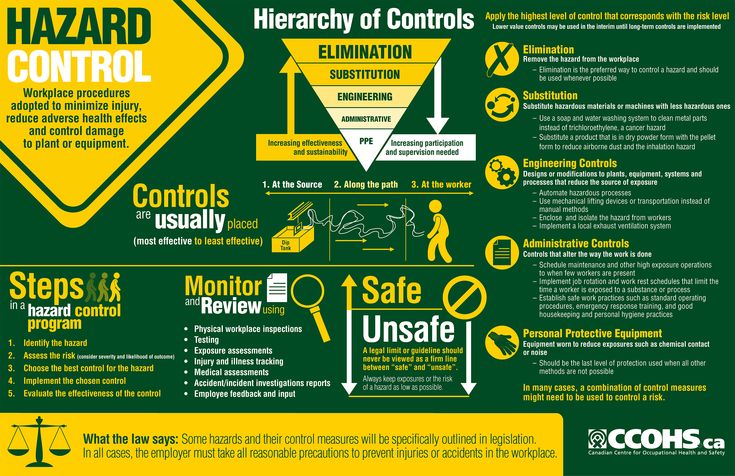

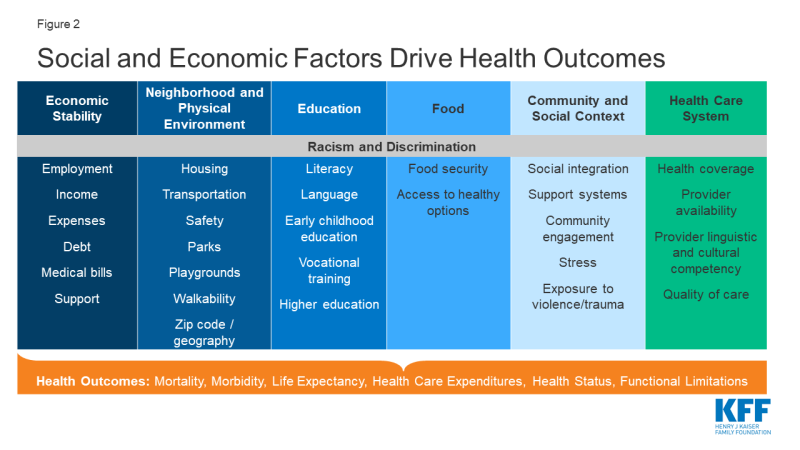

Work-related risk factors

Many risk factors for mental health problems can be associated with working conditions. Most of the risk factors are related to the interaction of such aspects as the type of work activity, organizational conditions and relationships with management, the skills and competencies of employees, the measures available at the enterprise to support employees in the performance of their job duties. nine0003

For example, an employee may have the necessary skills to complete a task but lack the resources to do what is required of them, or the enterprise may have unfavorable leadership styles and negative organizational practices.

Examples of mental health risk factors:

- inadequate occupational health and worker health;

- limited participation in decision-making;

- little control over their area of work; nine0018

- low level of employee support;

- inflexible working hours;

- fuzzy objectives or organizational goals.

The risk may also be associated with the nature of the activity, for example, the performance of duties by the employee that do not correspond to his competence, or a continuously high workload. Some activities may present a higher risk to the worker (for example, working as a disaster responder or humanitarian worker), which can lead to negative mental health effects and symptoms of mental disorders, or provoke alcohol or substance abuse. The risk may be increased if there is no cohesion within the team or there is no social support. nine0003

Harassment and psychological abuse (also taking the form of bullying) are common causes of work-related stress that pose a health risk to workers. Both physical and psychological problems can be associated with them. All of this creates economic costs for employers as productivity declines and employee turnover rises. It can also have a negative impact on the family and social life of workers.

Both physical and psychological problems can be associated with them. All of this creates economic costs for employers as productivity declines and employee turnover rises. It can also have a negative impact on the family and social life of workers.

Creating a healthy work environment

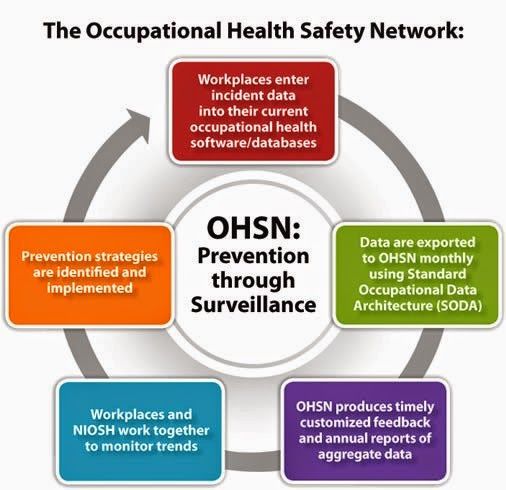

As demonstrated by the EU Mental Health Compass, an important element in creating healthy working conditions is the development of appropriate legislation, strategies and policies at the national level.

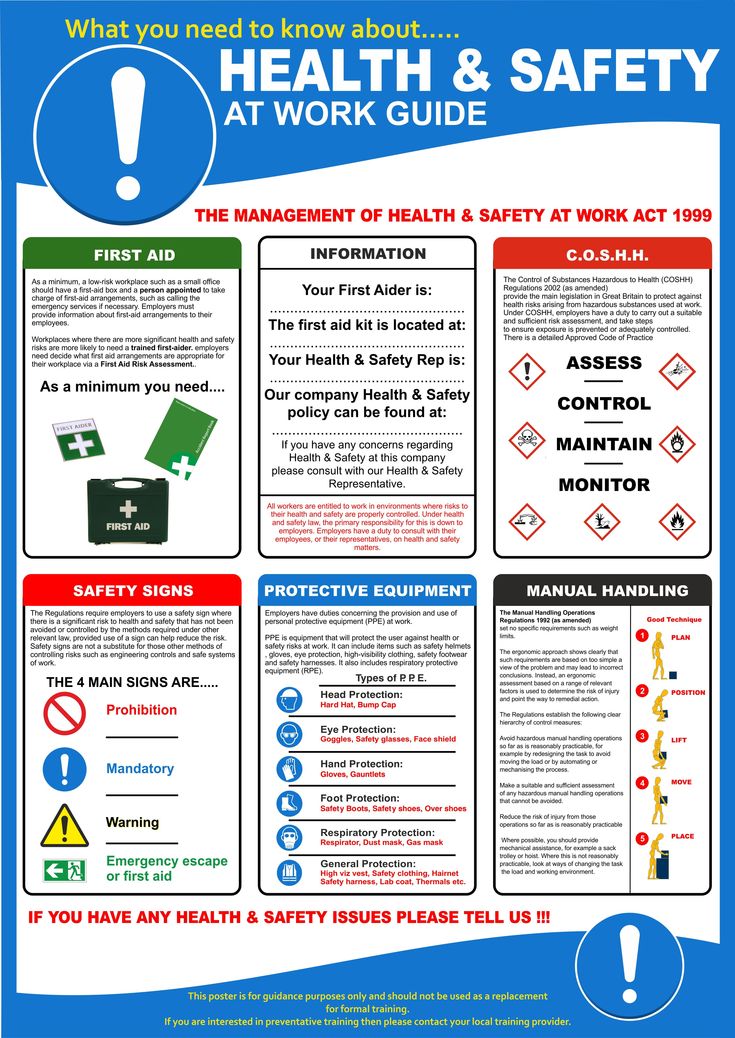

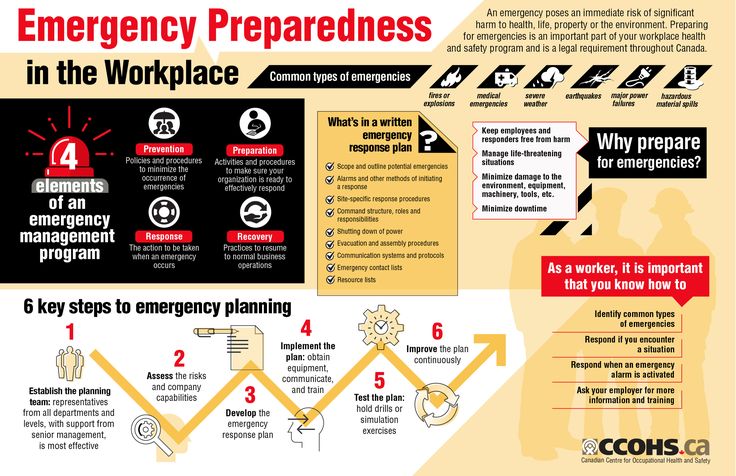

A healthy workplace environment can be described as one in which workers and managers actively participate in shaping the working environment by preserving and protecting the health, safety and well-being of all workers. The World Economic Forum guidelines recommend action in three areas:

- promote mental health by reducing work-related risk factors;

- strengthen mental health through the development of positive aspects of work and the strengths of workers;

- address mental health problems, whatever their causes.

The guide highlights a number of steps organizations can take to create a healthy workplace environment, such as:

- studying the workplace environment and how it can be adapted to improve the mental health of individual employees;

- studying the experience and motivation of leaders and employees of the organization who have taken any measures to improve working conditions;

- abandoning the practice of “reinventing the wheel” and using the positive experience of other companies;

- studying the needs of individual workers and how they can be involved in the development of more mental health-friendly policies within the enterprise; nine0018

- dissemination of information about sources of possible support and where help can be obtained.

Measures and best practices to promote mental health in the workplace include:

- implementing and enforcing occupational health and health policies and practices, including the identification of stress, substance abuse and disease, and providing resources to address these issues; nine0018

- informing employees about available types of assistance;

- involvement of employees in the decision-making process, creating a sense of ownership and participation in process management; implementation of measures for the organization of work, contributing to a normal balance between work and personal life;

- implementation of career development programs for employees;

- recognition and reward of employees' contributions.

Mental health interventions should be implemented as part of a comprehensive health and wellness strategy covering prevention, early detection, care and rehabilitation. Enterprise health services or health professionals can assist organizations in implementing such activities, if available; but even if this is not possible, a number of changes can be made to work processes that will preserve and strengthen the mental health of workers. The key to success is to involve stakeholders and workers themselves at all levels in health promotion and support activities and to monitor their effectiveness. nine0003

Providing support for people with mental disorders in the workplace

Organizations have a responsibility to support people with mental disorders so that they can either continue to work or be able to return to work. Research shows that unemployment, especially long-term unemployment, can be devastating to mental health.

Many of the initiatives listed above can help people with mental health problems. In particular, flexible working hours, reorganization of the work process, dealing with negative manifestations in the workplace, and communication with management, built on the principles of goodwill and trust, can all help people with mental disorders to return to work or continue working. nine0003

In particular, flexible working hours, reorganization of the work process, dealing with negative manifestations in the workplace, and communication with management, built on the principles of goodwill and trust, can all help people with mental disorders to return to work or continue working. nine0003

Providing access to evidence-based treatments has been shown to help overcome depression and other mental health conditions. Because of the stigmatization of mental disorders, employers need to ensure that workers feel supported and can seek help to continue or return to work, and that they are provided with sufficient resources to carry out their duties. nine0003

Article 27 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) provides a set of global, legally binding legal principles to protect the rights of persons with disabilities (including psychosocial disabilities). It recognizes that every person with a disability has the right to work, to be treated the same as other people, not to be discriminated against, and to receive support at work.

Principles for the protection of mentally ill persons and the improvement of mental health care - Conventions and agreements - Declarations, conventions, agreements and other legal materials

Adopted by General Assembly resolution 46/119 of 17 December 1991

Application

These Principles shall apply without discrimination of any kind on the basis of disability, race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, nationality, ethnicity or social origin, legal or social status, age, property or estate status.

Definitions

In these Principles:

a ) the term "lawyer" means a legal or other qualified representative;

b ) the term "independent authority" means a competent and independent body established in accordance with domestic law;

c ) the term "psychiatric care" includes the analysis or diagnosis of a person's mental state, as well as treatment, care and rehabilitation in connection with a mental illness or suspected mental illness; nine0003

d ) the term "psychiatric institution" means any institution or any department of an institution whose primary function is the provision of mental health care;

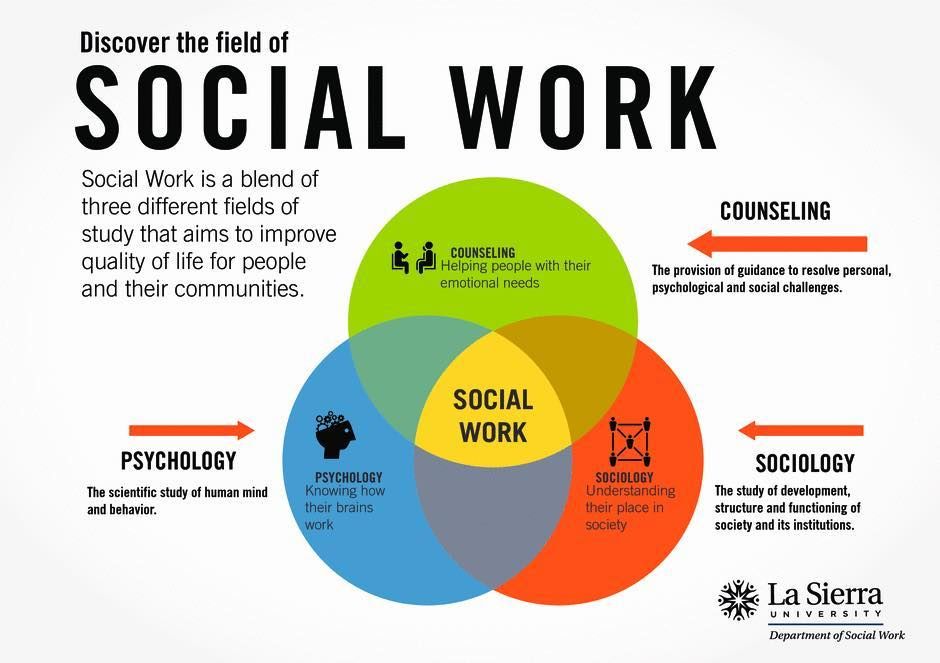

e ) the term "psychiatric professional" means a physician, clinical psychologist, nurse, social worker, or other person who has received appropriate training and has the necessary qualifications and specific skills to provide mental health care; nine0003

f ) the term "patient" means a person receiving mental health care, including persons admitted to a mental health facility;

g ) the term "personal representative" means a person who is required by law to represent the patient in any specified area or to exercise the specified rights on behalf of the patient, and includes the parent or legal guardian of a minor, unless national law provides otherwise.

; nine0003

h ) the term "supervisory authority" means the authority established in accordance with principle 17 to oversee the involuntary admission or detention of a patient in a psychiatric institution.

General limitation

The exercise of the rights set forth in these Principles may be subject only to such restrictions as are provided by law and are necessary to protect the health or safety of the person or others concerned, or to protect public safety, order, health or morals or fundamental rights and freedoms of others. nine0003

Principle 1

Fundamental freedoms and rights

1. All persons have the right to the best available mental health care, which is part of the health and welfare system.

2. All persons who are or are considered to be mentally ill shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person.

3. All persons who are or are considered to be mentally ill have the right to be protected from economic, sexual and other forms of exploitation, physical or other abuse and degrading treatment. nine0003

nine0003

4. No discrimination is allowed on the basis of mental illness. "Discrimination" means any difference, exclusion or preference which has the effect of canceling or hindering the equal enjoyment of rights. Special measures taken solely for the purpose of protecting the rights or improving the situation of mentally ill eggs are not considered discriminatory. Discrimination does not include any distinction, exclusion or preference exercised in accordance with the provisions of these Principles and necessary to protect the human rights of a mentally ill person or other individuals. nine0003

5. Every mentally ill person has the right to enjoy all civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 1 , the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2 civil and political rights 2 and other relevant documents such as the Declaration on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 3 and the Code of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment 4 .

6. Any decision that, by reason of his mental illness, a person is incompetent, and any decision that, as a result of such incapacity, a personal representative should be appointed, shall be taken only after a fair hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal established in accordance with with domestic law. The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings shall have the right to be represented by a lawyer. If the person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings is unable to provide himself with such representation, the latter must be provided to that person free of charge if he does not have sufficient means to do so. Counsel must not, in the same proceedings, represent a psychiatric institution or its staff, and also must not represent a family member of the person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, unless the judicial authority is satisfied that there is no conflict of interest. Decisions relating to legal capacity and the need for a personal representative are subject to review at reasonable intervals in accordance with domestic law. The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, his personal representative, if any, and any other interested person shall have the right to appeal any such decision to a higher court. nine0003

The person whose legal capacity is the subject of the proceedings, his personal representative, if any, and any other interested person shall have the right to appeal any such decision to a higher court. nine0003

7. If a court or other competent judicial authority determines that a mentally ill person is unable to manage his affairs, measures shall be taken, to the extent necessary and taking into account the state of such a person, in order to ensure that his interests are protected.

Principle 2

Protection of minors

For the purposes of these Principles, and in the context of domestic law relating to the protection of minors, particular attention should be paid to the protection of the rights of minors, including, if necessary, the appointment of a personal representative who is not a family member. nine0003

Principle 3

Living in the community

Every person with a mental illness has the right, as far as possible, to live and work in the community.

Principle 4

Diagnosis of mental illness

1. A person is diagnosed as having a mental illness in accordance with internationally recognized medical standards.

2. A diagnosis of mental illness is never made on the basis of political, economic, social status, or membership of any cultural, racial, or religious group, or for any other reason not directly related to a mental health condition. nine0003

3. Family or work conflict, or inconsistency with the moral, social, cultural or political values or religious beliefs prevailing in the society in which the person lives, can never be a determining factor in the diagnosis of mental illness.

4. Information about past treatment or hospitalization as a patient cannot by itself justify a diagnosis of present or future mental illness. nine0003

5. No person or authority may declare or otherwise indicate that a person is suffering from a mental illness except for purposes directly related to the mental illness or the consequences of the mental illness.

Principle 5

Medical examination

No person may be compelled to undergo a medical examination to determine whether he or she suffers from a mental illness, except in accordance with a procedure provided for by national law. nine0003

Principle 6

Confidentiality

Information relating to all persons to whom these Principles apply shall be kept confidential.

Principle 7

The role of the community and culture

1. Every patient has the right, to the extent possible, to treatment and care in the community in which he lives.

2. While being treated in a psychiatric institution, the patient has the right, whenever possible, to be treated close to his home or the home of his relatives or friends, and has the right to return to his community as soon as possible. nine0003

3. Every patient has the right to culturally appropriate treatment.

Principle 8

Standards of Care

1. Every patient has the right to such medical and social care as is necessary to maintain his health and is entitled to care and treatment in accordance with the same standards as other patients.

Every patient has the right to such medical and social care as is necessary to maintain his health and is entitled to care and treatment in accordance with the same standards as other patients.

2. Every patient shall be protected from harm to his health, including the unreasonable use of medicines, abuse by other patients, staff or others, and other acts that cause mental suffering or physical discomfort. nine0003

Principle 9

Treatment

1. Every patient has the right to be treated in the least restrictive setting and by the least restrictive or invasive methods appropriate to maintain his health and protect the physical safety of others.

2. Each patient's care and treatment is based on an individually developed plan that is discussed with the patient, regularly reviewed, modified as necessary, and provided by qualified medical personnel. nine0003

3. Psychiatric care is always provided in accordance with applicable ethical standards for professionals working in the field of psychiatry, including internationally recognized standards such as the Principles of Medical Ethics relating to the role of health professionals, especially physicians, in protecting prisoners or detainees from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations 5 . Abuse of knowledge and skills in the field of psychiatry is not allowed

Abuse of knowledge and skills in the field of psychiatry is not allowed

4. The treatment of each patient should be aimed at maintaining and developing the autonomy of the individual.

Principle 10

Medications

1. Medications must best suit the need to maintain the patient's health, should only be administered to the patient for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes, and should never be used as a punishment or for the convenience of others. Except as provided in paragraph 15 of principle 11 below, mental health professionals will only use medications that are known or proven to be effective. nine0003

2. All medications are prescribed by legally authorized psychiatrists and recorded in the patient's medical record.

Principle 11

Consent to treatment

1. No treatment may be administered to a patient without their informed consent, except as provided in paragraphs 6,7,8,13 and 15 of this principle.

2. Informed consent is consent obtained freely, without threats or undue coercion, after adequate and clear information has been provided to the patient, in a form and language that the patient understands, about:

a ) preliminary diagnosis,

b ) the purpose, methods, likely duration and expected results of the proposed treatment;

with ) alternative therapies, including less invasive ones;

d ) possible pain and discomfort, possible risks and side effects of the proposed treatment.

3. During the consent process, the patient may request the presence of a person or persons of their choice.

4. The patient has the right to refuse or stop treatment, except as provided in paragraphs 6, 7, 8, 13 and 15 of this principle. The consequences of refusing or stopping treatment should be explained to the patient.

5. The patient must not be asked or encouraged to waive the right to informed consent. If the patient expresses a desire to waive this right, it must be made clear to him that the treatment cannot be carried out without his informed consent. nine0003

6. Except as provided in paragraphs 7, 8, 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, the proposed course of treatment may be administered to a patient without his informed consent, subject to the following conditions:

a ) the patient is currently involuntarily hospitalized;

b ) an independent authority, in possession of all relevant information, including the information referred to in paragraph 2 of this principle, is satisfied that the patient is not currently in a position to give or withhold informed consent to the proposed course of treatment or, if provided for by domestic law, that, having regard to the patient's own safety or the safety of others, the patient has unreasonably refused to give such consent; nine0003

to ) an independent authority has determined that the proposed course of treatment is in the best interest of the patient's health.

7. The provisions of paragraph 6 above do not apply to a patient who has a personal representative authorized by law to consent to treatment for the patient; however, except as provided in paragraphs 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, treatment may be administered to such a patient without his informed consent if the personal representative, having received the information specified in paragraph 2 of this principle, consents on behalf of the patient. nine0003

8. Except as provided in paragraphs 12, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, treatment may also be given to any patient without their informed consent, if a qualified mental health professional authorized by law determines that administer this treatment urgently to prevent immediate or imminent harm to the patient or others. Such treatment shall not be extended beyond the period strictly necessary for that purpose. nine0003

9. Where any treatment is administered to a patient without the patient's informed consent, every effort should nevertheless be made to inform the patient of the nature of the treatment and of any possible alternative methods and, to the extent possible, involve the patient in the development of a course of treatment.

10. Any treatment is immediately recorded in the patient's medical record, indicating whether the treatment is compulsory or voluntary.

11. Physical restraint or involuntary isolation of a patient shall be used only in accordance with the official procedures of the psychiatric facility and only when it is the only means available to prevent immediate or imminent harm to the patient or others. They shall not be extended beyond the period strictly necessary for that purpose. All cases of physical restraint or involuntary isolation, the reasons for their application, their nature and duration should be recorded in the patient's medical history. A patient subjected to restraint or isolation must be kept in humane conditions, cared for, and carefully and constantly monitored by qualified medical personnel. The personal representative, if any and if appropriate, shall be promptly informed of any physical restraint or involuntary isolation of the patient. nine0003

12. Sterilization is never used as a treatment for mental illness.

13. A mentally ill person may be subjected to serious medical or surgical intervention only in cases where this is permitted by national law, when it is considered in the best interests of the patient's health, and when the patient gives informed consent, but in cases where the patient is not able to give informed consent, this intervention is prescribed only after an independent assessment. nine0003

14. Psychosurgery and other types of invasive and irreversible treatment of mental illness shall not, under any circumstances, be applied to a patient who has been involuntarily admitted to a psychiatric institution, and may be applied, within the limits permitted by domestic law, to any other patient only where the patient has given informed consent and an independent external body is satisfied that the patient's consent is indeed informed and that the treatment is in the best interests of the patient's health. nine0003

15. Clinical trials and experimental treatments shall not, under any circumstances, be used on any patient without their informed consent, unless clinical trials and experimental treatments may be used on a patient who is unable to give informed consent, only with the permission of a competent independent supervisory authority specially established for this purpose.

16. In the cases specified in paragraphs 6, 7, 8, 13, 14 and 15 of this principle, the patient or his personal representative, or any interested person, has the right to appeal to a judicial or other independent authority regarding the application to the patient any treatment. nine0003

Principle 12

Notice of rights

1. The patient in a psychiatric institution shall, as soon as possible after admission, be informed, in a form and in a language that he understands, of all his rights under these Principles and under national law, and such information includes an explanation of these rights and how they can be exercised.

2. If and until the patient is unable to understand such information, the patient's rights will be communicated to the patient's personal representative, if any and as appropriate, and to the person or persons best able to represent the patient and willing to do so. nine0003

3. A patient with the necessary legal capacity has the right to appoint any person to be informed on his behalf, as well as a person to represent his interests before the administration of the institution.

Principle 13

Rights and conditions of detention in psychiatric institutions

1. Any patient held in a psychiatric institution has the right, in particular, to be fully respected:

a ) universal recognition as a subject of law; nine0003

b ) privacy rights;

c ) freedom of communication, which includes the freedom to communicate with others within the institution; the freedom to send and receive private communications that are not subject to censorship; freedom to receive in private a lawyer or personal representative and, at any reasonable time, other visitors; and freedom of access to postal and telephone services, as well as to newspapers, radio and television;

nine0002 d ) freedom of religion or belief.

2. The environment and conditions of life in a psychiatric institution should, as far as possible, approximate those of normal life for persons of the same age and, in particular, include:

a ) opportunities for leisure and recreation;

b ) educational opportunities;

with ) opportunities to buy or receive items necessary for everyday life, leisure activities and communication;

d ) opportunities - and encouragement to use such opportunities - to involve the patient in activities appropriate to his social position and cultural characteristics, and to carry out appropriate vocational rehabilitation measures for his social reintegration.

These measures should include vocational guidance, vocational training and placement services so that patients can get or keep jobs in the community. nine0003

3. Under no circumstances may a patient be subjected to forced labor. To the extent compatible with the needs of the patient and with the requirements of the institution's administration, the patient should be able to choose the kind of work he wishes to do.

4. The work of a patient held in a psychiatric institution must not be exploited. Any such patient shall be entitled to receive for the work performed by him the same remuneration as, in accordance with national laws or customs, a person who is not a patient would receive for similar work. Any such patient shall in all cases be entitled to receive a fair share of any remuneration paid to a psychiatric institution for its work. nine0003

Principle 14

Resources for psychiatric institutions

1. A psychiatric institution must have access to the same resources as any other hospital, including but not limited to:

a ) a sufficient number of qualified medical personnel and other relevant professionals and adequate facilities to provide each patient with conditions of privacy and for the necessary and active course of treatment; nine0003

b ) diagnostic and therapeutic equipment for the patient;

with ) proper maintenance by specialists;

d ) adequate, regular and comprehensive treatment, including the supply of medicines.

2. Every mental health facility should be inspected with sufficient regularity by the competent authorities to ensure that the conditions of patient care, treatment and care comply with these Principles. nine0003

Principle 15

Principles of hospitalization

1. When a person needs treatment in a psychiatric institution, every effort should be made to avoid involuntary hospitalization.

2. Access to a mental health facility should be regulated in the same way as access to any other health facility for any other illness.

3. Every non-involuntary hospitalized patient has the right to leave a psychiatric facility at any time, unless the criteria for involuntary detention provided for in principle 16 below apply, and he must be informed of this right. nine0003

Principle 16

Involuntary hospitalization

1. Any person may be admitted to a psychiatric institution as an involuntary patient or already admitted as a voluntary patient may be involuntarily detained as a patient in a psychiatric institution if and only if an authorized person for this goals under the law a qualified mental health professional will determine, in accordance with principle 4 above, that the person is suffering from a mental illness and will determine:

a ) that, as a result of this mental illness, there is a serious risk of imminent or imminent harm to that person or others; or

b ) that, in the case of a person whose mental illness is severe and whose mental capacity is impaired, refusal to admit the person to hospital or to a psychiatric facility could seriously impair his health or make it impossible for appropriate treatment to be given subject to admission to a psychiatric institution in accordance with the principle of the least restrictive alternative.

nine0003

In the case of subparagraph b), it is necessary, if possible, to consult with a second such specialist working in the field of psychiatry. In the case of such consultation, hospitalization in a psychiatric institution or involuntary detention may take place only with the consent of a second specialist working in the field of psychiatry.

2. Involuntary admission or detention in a psychiatric institution shall be carried out initially for a short period determined by national law for the purpose of observation and pre-treatment, pending consideration of the admission or detention of the patient in a psychiatric institution by a supervisory authority. The reasons for hospitalization or detention are immediately reported to the patient; the fact of hospitalization or detention and their reasons shall also be reported promptly and in detail to the supervisory authority, the patient's personal representative, if any, and, if the patient does not object, to the patient's family. nine0003

nine0003

3. A psychiatric facility may only admit involuntary patients if the facility is designated for that purpose by a competent authority established by national law.

Principle 17

Supervisory Authority

1. The Supervisory Authority is a judicial or other independent and impartial body established under national law and functioning in accordance with procedures established by national law. In preparing his decisions, he shall be assisted by one or more qualified and independent professionals working in the field of psychiatry and take their advice into account. nine0003

2. Consistent with principle 16, paragraph 2, above, the initial review by a supervisory authority of a decision to admit or hold a patient in a psychiatric facility shall take place as soon as possible after the decision has been made and should be carried out in accordance with simplified and expedited procedures, provided for in national law.

3. The oversight body reviews cases of involuntary hospitalization periodically at reasonable intervals determined by national law. nine0003

nine0003

4. A compulsorily hospitalized patient may, at reasonable intervals, as determined by national law, apply to a supervisory authority for discharge or to be granted the status of a voluntary hospitalized patient.

5. At each review, the supervisory authority should consider whether the criteria for involuntary admission set out in principle 16, paragraph 1, above are still met and, if not, the patient should be discharged as an involuntary hospitalization. nine0003

6. If at any time the psychiatric professional in charge of the case is satisfied that the conditions of the person's detention as an involuntary hospitalized patient are no longer satisfied, that specialist shall order the person's release as a patient, compulsorily hospitalized.

7. The patient, or his personal representative, or any interested person has the right to appeal to a higher court the decision to hospitalize the patient or keep him in a psychiatric facility. nine0003

Principle 18

Procedural safeguards

1. The patient has the right to choose and appoint an attorney to represent the patient as such, including representation in any complaint or appeal procedure. If the patient does not provide such services on his own, the lawyer is provided to the patient free of charge insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for his services.

The patient has the right to choose and appoint an attorney to represent the patient as such, including representation in any complaint or appeal procedure. If the patient does not provide such services on his own, the lawyer is provided to the patient free of charge insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for his services.

2. The patient also has the right, if necessary, to use the services of an interpreter. When such services are needed and the patient cannot provide them, they are provided free of charge to the patient insofar as the patient does not have sufficient funds to pay for these services. nine0003

3. The patient and the patient's advocate may request and present at any hearing an independent psychiatric report and any other opinions and written and oral evidence that is relevant and acceptable.

4. Copies of the patient's medical records and any reports and documents that are required to be produced are served on the patient or the patient's advocate, except in exceptional cases where it is determined that disclosing specific information to the patient would cause serious harm to the patient's health or endanger the safety of others. In accordance with national law, any document not presented to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be served on the patient's personal representative and counsel. In the event that any part of any document is not presented to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the failure and the reasons for it, and the decision may be subject to judicial review. nine0003

In accordance with national law, any document not presented to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be served on the patient's personal representative and counsel. In the event that any part of any document is not presented to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the failure and the reasons for it, and the decision may be subject to judicial review. nine0003

5. The patient and the patient's personal representative and advocate have the right to attend, participate in, and be heard at any hearing.

6. If a patient, or a personal representative, or a patient advocate, requests that a certain person be present at the hearing, that person is admitted to the hearing, unless it is determined that his presence would cause serious harm to the patient's health or put him under threat to the safety of others. nine0003

7. Any decision as to whether a hearing, or part of it, will be open or closed and disclosed to the public must be made in the light of the wishes of the patient, the need to respect the right of the patient and others to privacy, and the need to prevent serious harm to the patient's health or risk to the safety of others.

8. The decision made at the end of the hearing and the reasons for it are set out in writing. Copies are issued to the patient and the patient's personal representative and advocate. In deciding whether the decision will be published in whole or in part, full consideration should be given to the wishes of the patient, the need to respect the privacy of the patient and the privacy of others, the public interest in the open administration of justice, and the need to prevent serious harm to the patient's health or safety risk. other persons. nine0003

Principle 19

Access to information

1. A patient (a term which in this principle also includes former patients) has the right to access information relating to him/her in the medical history maintained by a psychiatric institution. This right may be restricted in order to prevent serious harm to the health of the patient and risk to the safety of others. In accordance with national law, any such information not provided to the patient should, when possible in confidence, be communicated to the patient's personal representative and counsel. In the event that any such information is not disclosed to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the non-disclosure of this information and the reasons for it, and this decision is subject to judicial review. nine0003

In the event that any such information is not disclosed to the patient, the patient or the patient's advocate, if any, is notified of the non-disclosure of this information and the reasons for it, and this decision is subject to judicial review. nine0003

2. Any written comments by the patient, or the patient's personal representative or advocate, may be included in the patient's medical history upon request.

Principle 20

Criminal offenders

1. This principle applies to persons who are serving a term of imprisonment for a criminal offense or to persons who are otherwise detained in the course of proceedings or investigations brought against them for a criminal offense and who are found to be suffering from a mental illness or are suspected to be suffering from such an illness. nine0003

2. These persons should receive the best possible mental health care, as provided for in principle 1 above. These Principles apply to them to the fullest extent possible, with only such limited modifications and exceptions as are necessary in the circumstances. No such modification or exclusion shall prejudice the rights of these persons under the instruments listed in paragraph 5 of principle 1 above.

No such modification or exclusion shall prejudice the rights of these persons under the instruments listed in paragraph 5 of principle 1 above.

3. Provisions of domestic law may authorize a court or other competent authority, on the basis of a competent and independent medical opinion, to decide on the placement of such persons in a psychiatric institution. nine0003

4. The treatment of persons diagnosed with mental illness must, in all circumstances, be consistent with principle 11 above.

Principle 21

Complaints

Every patient and former patient has the right to file a complaint in accordance with the procedures set out in national law.

Principle 22

Oversight and remedies

States shall ensure that appropriate mechanisms are in place to promote compliance with these Principles for the inspection of mental health facilities, for the presentation, investigation and resolution of complaints, and for the initiation of appropriate disciplinary or judicial proceedings in cases of breach of duty or patient rights.