Ritalin and anxiety

The Science Behind Ritalin and Anxiety

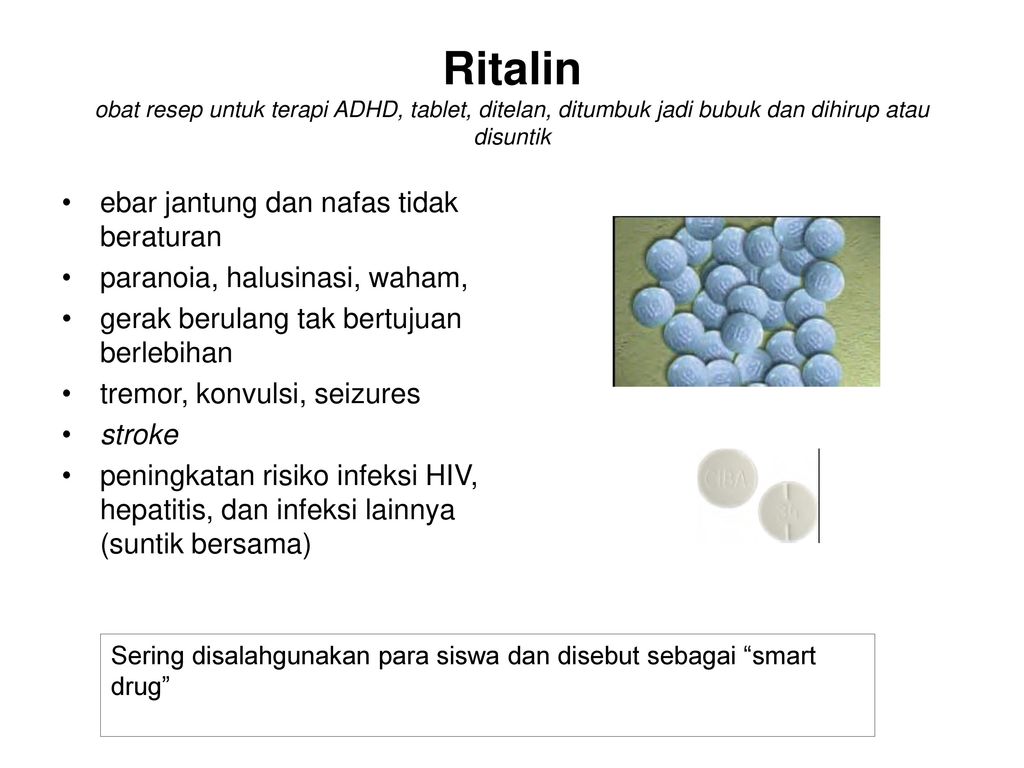

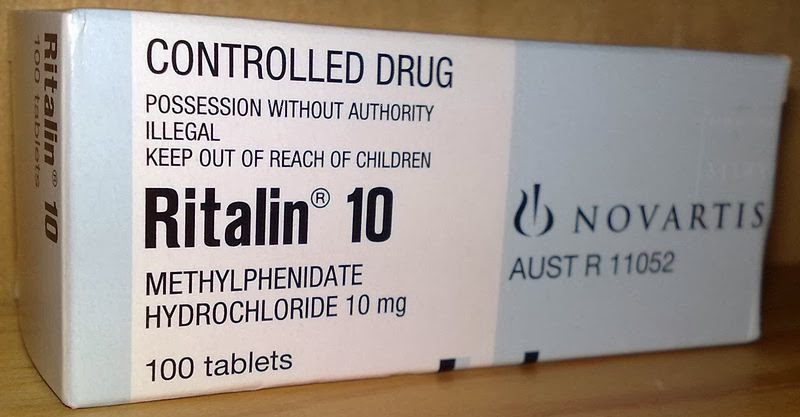

The prescription drug Ritalin (occasionally misspelled "Riddlin"), also known as methylphenidate, is a controversial substance.

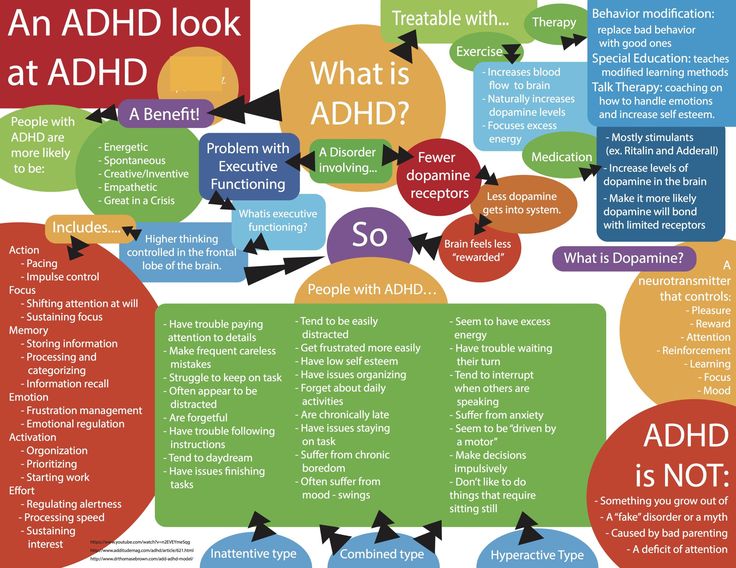

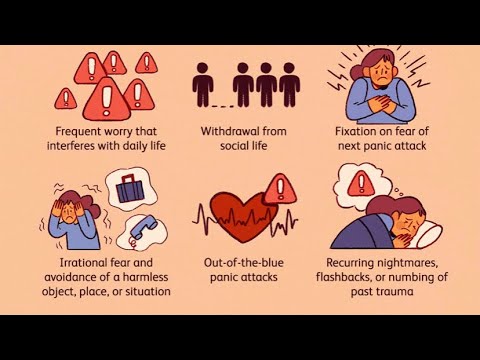

Frequently prescribed to children in the U.S. who are diagnosed with ADHD (a.k.a. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), there have been concerns about its negative side effects as well as discoveries of new uses for it including recovery from cigarette and even cocaine addictions. While scientists do know the effect it has on the brain, why it works is not well understood.

This article will explore the possibility of using Ritalin as a treatment for anxiety problems, as well as the risks involved with its use.

Listening to Your Doctor

Ritalin is never something you should take off label, and only something to take if a doctor recommends it. If your doctor tells you or your child to take Ritalin, you should consider it. But note that anxiety is better cured with behavioral interventions.

Ritalin In Your Body: A Scientific Overview

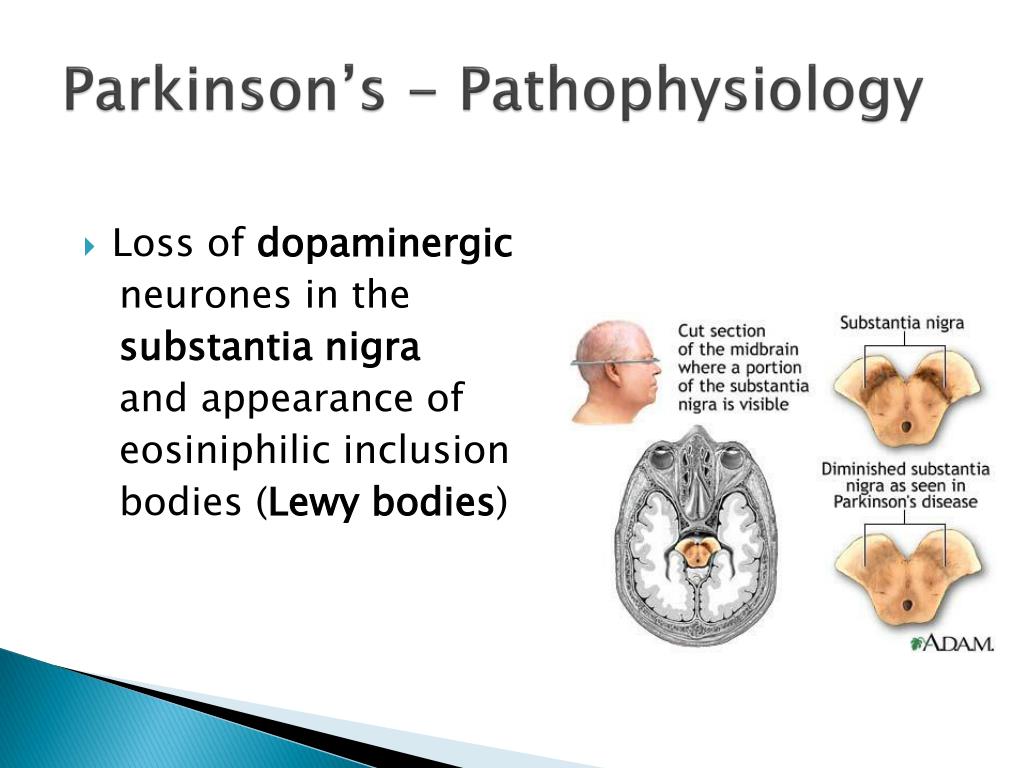

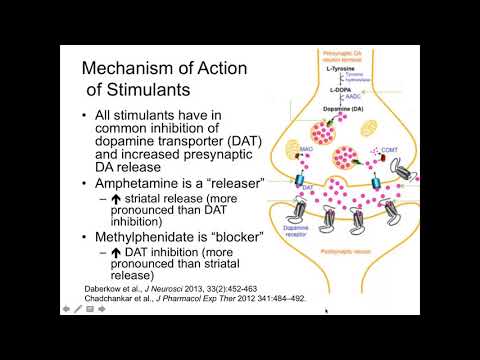

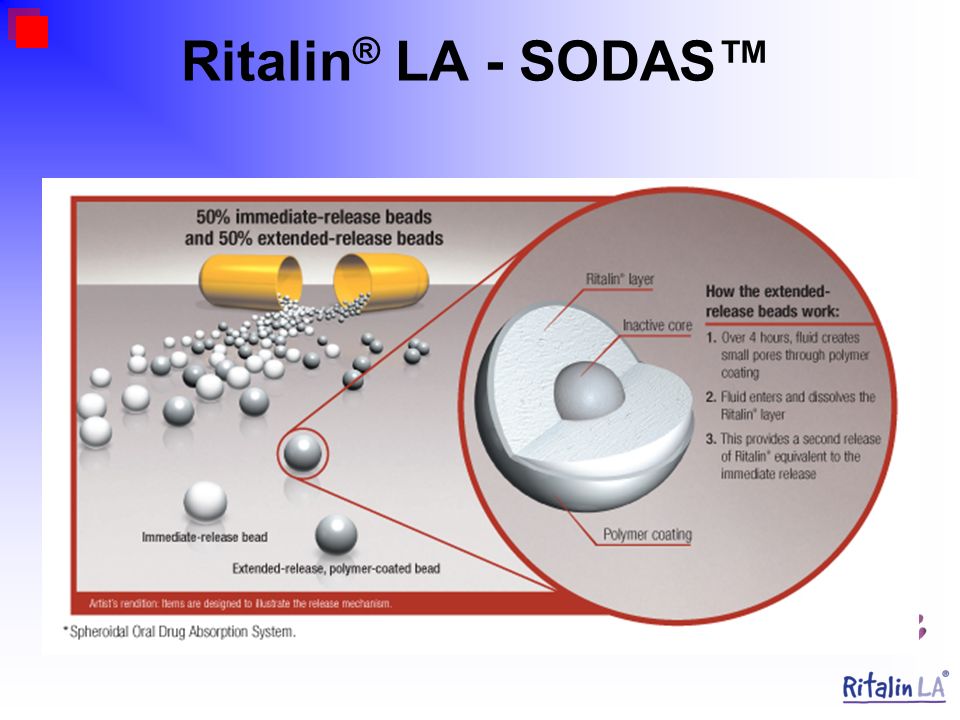

Ritalin's primary function is increasing the levels of the chemicals dopamine and norepinephrine in the human brain. It does this by partially blocking the dopamine and norepinephrine transporters that removes them from the synapses.

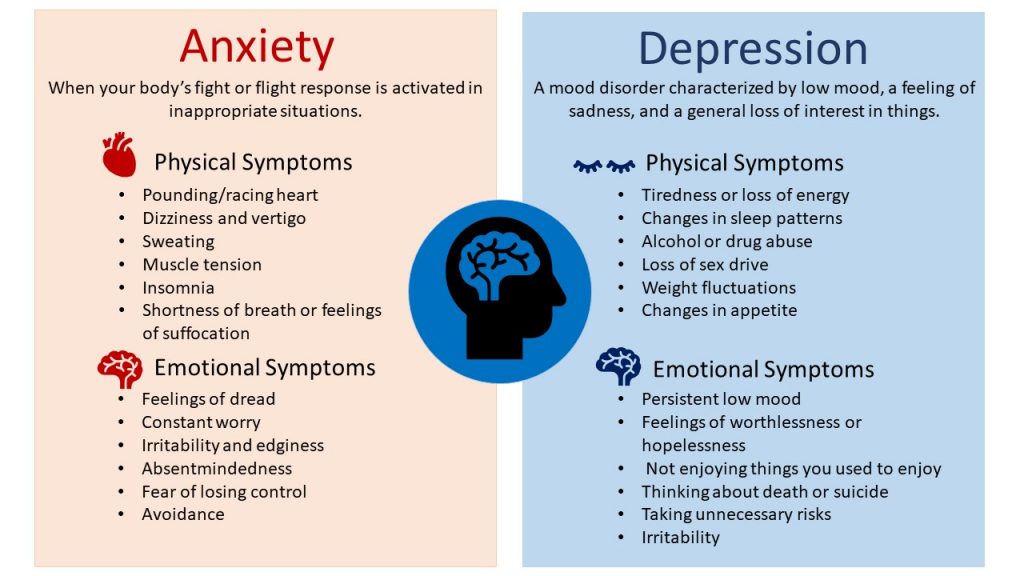

Dopamine is a potentially useful chemical for anxiety sufferers: however, norepinephrine is more problematic. To summarize what each chemical does:

- Dopamine Dopamine is the body's "happy" chemical, playing an important role in motivation and arousal, as well as motor control. A significant increase in dopamine mimics the effect of "hard drugs" such as cocaine, which is why Ritalin is now used as a treatment for cocaine addiction and occasionally used recreationally by drug abusers.

- Norepinephrine Norepinephrine, on the other hand, is responsible for actions in the sympathetic nervous system that direct fight or flight responses such as increased heart rate, the release of glucose from the body's energy stores, and increased blood flow to the skeletal muscles.

In sufferers from ADHD this can help promote alertness. However, for anxiety-sufferers, it is more likely to have the effect of increasing anxiety.

In sufferers from ADHD this can help promote alertness. However, for anxiety-sufferers, it is more likely to have the effect of increasing anxiety.

Ritalin is technically categorized as a stimulant (specifically a "psychostimulant," or stimulant of the central nervous system). It is because of this factor that psychostimulant drugs - even drugs that, by increasing dopamine, may temporarily reduce anxiety - may paradoxically have the effect of increasing anxiety for people more psychologically prone to anxiousness.

Study Shows Ritalin as Effective Anti-Anxiety Med for ADHD Children

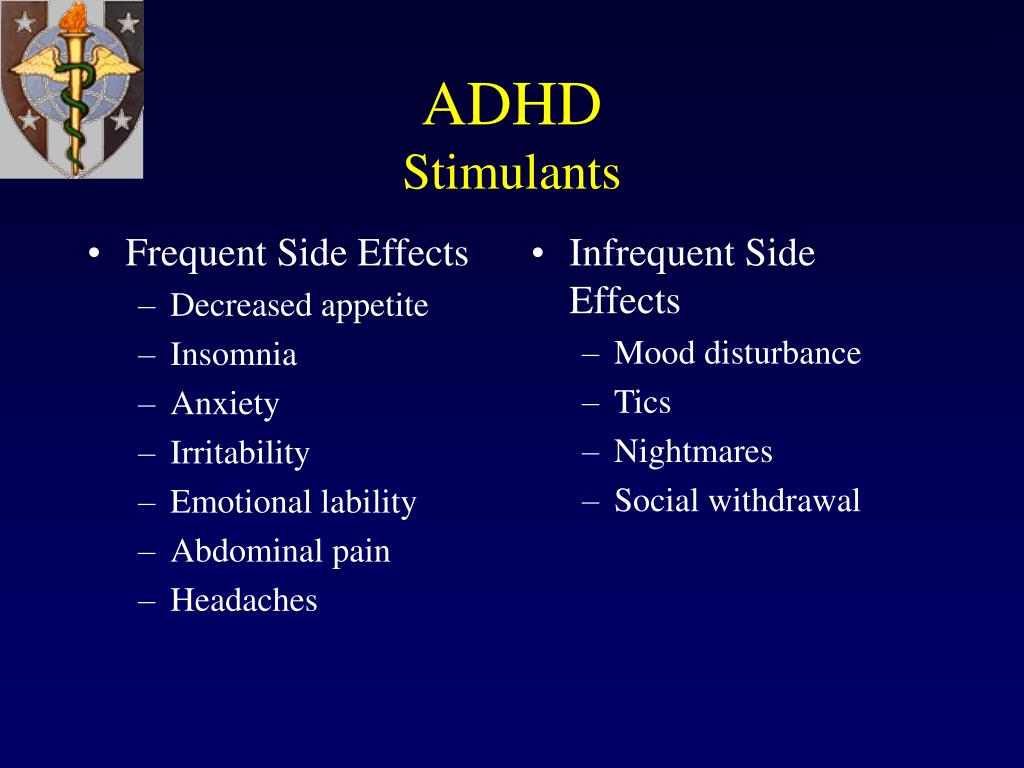

In a 1993 placebo-controlled study of the effects of Ritalin on children, it was concluded that while the frequency of insomnia, appetite disturbance, stomachache, headache and dizziness significantly increased in the children taking Ritalin, the frequency of anxiety and nail-biting (along with "staring and daydreaming") significantly decreased. This would seem to indicate that at least in children, Ritalin can be an effective anti-anxiety medication.

It is important to note, however, that the children who took part in this study suffered from ADHD, rather than from anxiety. Because of the risk of aggravating preexisting anxiety problems posed by increased norepinephrine in the body, studies of Ritalin's effects on anxiety-prone adults are not being performed.

What Anxiety-Sufferers Are Saying About It

Despite the scientific community's misgivings, some anxiety sufferers who have been prescribed Ritalin for ADHD have found it to have some interesting effects, though the negative reports are more common than the positive. Some described fatigue, while others described extreme energy.

However, the majority of users simply found that their anxiety increased, and experienced no noticeable calmative effects.

The Final Word on Ritalin and Anxiety

While it is easy to imagine that a drug that seems to "calm" overexcited children would be great for your anxiety, the truth is that this drug is designed to stimulate alertness and therefore runs the risk of worsening your anxiety rather than improving it.

If your doctor insists that you start taking Ritilan, than you should take it. But otherwise make sure that you're considering behavioral options as well.

Was this article helpful?

- Yes

- No

Sources:

- Ahmann, Peter A., et al. Placebo-controlled evaluation of Ritalin side effects. Pediatrics 91.6 (1993): 1101-1106.

- Vastag, Brian. Pay attention: ritalin acts much like cocaine. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 286.8 (2001): 905-906.

Effect of Methylphenidate on State Anxiety in Children With ADHD-A Single Dose, Placebo Controlled, Crossover Study

- Journal List

- Front Behav Neurosci

- PMC6530494

Front Behav Neurosci. 2019; 13: 106.

2019; 13: 106.

Published online 2019 May 15. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00106

,1,2,1,3,2,4 and 1,2,3,*

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Introduction: Non-adherence to efficacious pharmacotherapy is a major obstacle in the treatment of children suffering from attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). Some hold the position that pharmacotherapy induces anxiety, and that this is one of the reasons for this non-adherence. Previous studies have pointed to the opposite, a moderating effect of methylphenidate (MPH) on state anxiety in patients with ADHD. This has been shown in continuous treatment in children, but not on a single dose. We hypothesized that a single dose might have a different effect.

Method: Twenty children with ADHD were given single doses of MPH in a randomized, controlled, crossover, double blind study. State anxiety using The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and a continuous performance test were assessed.

State anxiety using The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and a continuous performance test were assessed.

Results: As a group, no change was detected in state anxiety with MPH or placebo. However, children who were given MPH during the first session as opposed to those who received placebo first, demonstrated deterioration in baseline state anxiety in the second session [t(2.485), p < 0.05].

Conclusion: Our findings show a possible delayed anxiety-provoking effect of a single dose of MPH. This may be relevant to the understanding of difficulties in adherence with MPH treatment in children with ADHD.

Clinical Trial Registration: www.ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier: {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT01798459","term_id":"NCT01798459"}}NCT01798459

Keywords: ADHD, state anxiety, methylphenidate, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, pharmacotherapy

Attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) is a common worldwide behavioral and neurocognitive disorder with an onset in childhood and substantial negative effects on child and adult life (Erskine et al. , 2016; Sayal et al., 2018). The evidence regarding the efficacy and importance of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of ADHD is extremely robust (Group, 1999; Lichtenstein et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2017), and pharmacotherapy (most commonly prescribed are stimulants) is part of treatment recommendations and practice guidelines (Atkinson and Hollis, 2010; Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder et al., 2011; Seixas et al., 2012).

, 2016; Sayal et al., 2018). The evidence regarding the efficacy and importance of pharmacotherapy in the treatment of ADHD is extremely robust (Group, 1999; Lichtenstein et al., 2012; Chang et al., 2017), and pharmacotherapy (most commonly prescribed are stimulants) is part of treatment recommendations and practice guidelines (Atkinson and Hollis, 2010; Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder et al., 2011; Seixas et al., 2012).

Studies demonstrate high rates of ADHD comorbidity with anxiety (~25–50%) (Larson et al., 2011; Sciberras et al., 2014). The effect of stimulant medications on anxiety in ADHD patients, bears both conceptual and clinical importance. Non-adherence to pharmacotherapy is a major obstacle to effective treatment for children suffering from ADHD. Side effects that include loss of appetite, as well as “not feeling like myself” and feeling tense and stressed were identified as leading reasons for non-adherence (Frank et al., 2015; Kovshoff et al., 2016; Wang et al. , 2016). MPH causes a rise in extracellular dopamine in the brain, leading to improvements in cognitive functions such as attention and vigilance. However, it may possibly also cause a rise in tension, stress and anxiety through the same mechanism. Evidence regarding the possibility of anxiety as a stimulant side effect have been mixed. There are patient reports that highlight that anxiety is a possible side effect of stimulants, however, systematic studies point to the opposite effect. A meta-analysis of well controlled studies that collected systematic reports of anxiety during stimulant therapy revealed a significant dose-dependent reduction in anxiety in the treatment group when compared with placebo (Coughlin et al., 2015). This raises the possibility that untreated ADHD is a mediator of anxiety.

, 2016). MPH causes a rise in extracellular dopamine in the brain, leading to improvements in cognitive functions such as attention and vigilance. However, it may possibly also cause a rise in tension, stress and anxiety through the same mechanism. Evidence regarding the possibility of anxiety as a stimulant side effect have been mixed. There are patient reports that highlight that anxiety is a possible side effect of stimulants, however, systematic studies point to the opposite effect. A meta-analysis of well controlled studies that collected systematic reports of anxiety during stimulant therapy revealed a significant dose-dependent reduction in anxiety in the treatment group when compared with placebo (Coughlin et al., 2015). This raises the possibility that untreated ADHD is a mediator of anxiety.

One possible explanation for these contradictory findings is the difference in duration of follow-up. In a nationwide follow-up study of adherence to stimulants in Taiwan, more than 17% of the children that were diagnosed with ADHD and given a prescription for Methylphenidate IR (MPH), discontinued therapy after a single dose, accounting for approximately a third of the total discontinuation rate within the first year (51% of study population discontinued within the first year) (Wang et al. , 2016). Thus, it is possible that there is an acute rise in anxiety levels in children treated with MPH, however, for a considerable part of the patient population, continuous therapy can improve the anxiety related to ADHD.

, 2016). Thus, it is possible that there is an acute rise in anxiety levels in children treated with MPH, however, for a considerable part of the patient population, continuous therapy can improve the anxiety related to ADHD.

In the present pilot study, we set out to assess state anxiety in pediatric ADHD patients facing a cognitive task, after being given single dose of MPH, compared with placebo.

Participants

A group of 20 children and adolescents native Hebrew speakers, 11 boys and 9 girls, between ages 8 and 18 years, participated in the study (M age = 10.5 years, SD = 1.99). The patients were recruited through advertisement and through the outpatient clinic. The diagnosis of ADHD was based on structured clinical interviews with the child and parents conducted by a child psychiatrist trained in diagnosing childhood ADHD with the aid of the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale (SNAP-IV) filled by multiple informants. This questionnaire is widely used, as a screening tool, with good sensitivity to detect the core symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Hall et al. , 2019). Criteria for exclusion were a known diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, current depressive episode, eating disorder, active anxiety disorder, and current (past 6 months) substance abuse. No formal cognitive assessment was performed, but all participants studied in regular classes, and based on the clinical assessment, there was no intellectual disability.

, 2019). Criteria for exclusion were a known diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, current depressive episode, eating disorder, active anxiety disorder, and current (past 6 months) substance abuse. No formal cognitive assessment was performed, but all participants studied in regular classes, and based on the clinical assessment, there was no intellectual disability.

Procedure

This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Study protocol and consent form were approved by both the institutional review board (0009-12-SHA) and the national review board (20120239). Participants were recruited from our ADHD clinic. The study protocol was explained in detail to the participant and family. Informed consent was provided by participants' parent or legal guardian prior to any study-related activity.

The study was registered on clinical trials.gov 0009-12-SHA; {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT01798459","term_id":"NCT01798459"}}NCT01798459.

All participants underwent two identical session evaluations. In both sessions, the subjects completed The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) questionnaire (Okun et al., 1996) before any intervention and performed Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery CANTAB neurocognitive tests (De Luca et al., 2003). Mean STAI-Trait was 45.90 (SD = 6.70).

Participants were randomly assigned to receive MPH 0.3 mg/kg immediate release or inert ingredient (placebo). Forty-five minutes after drug administration, subjects completed STAI—state questionnaire again and performed the cognitive tasks. In the second session, medication (MPH/placebo) was crossed-over.

Tools

The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire (SNAP-IV) (Bussing et al., 2008), is a well validated questionnaire that is used to quantify ADHD symptomatology as well as to screen for other common behavioral and emotional symptoms. It was completed by one of the parents and, separately, by a teacher.

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (Sheehan et al., 2010), is a short structured diagnostic interview for phenomenological psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents.

The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1970), is a 40-item scale which measures the intensity of felt anxiety. It includes 20 questions aimed to quantify state anxiety (temporary, experienced in particular situations) and 20 questions to evaluate trait anxiety (a general tendency to perceive situations as threatening). Each item is rated on a 1–4 scale. Range of scores for each subtest is 20–80, the higher score indicating greater anxiety (Oei et al., 1990; Rossi and Pourtois, 2012). The STAI was used in its' hebrew version (Teichman and Melink, 1984), that was validated and used in previous studies in this age group (Zohar and Bruno, 1997).

The following Subsets from Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) were administered: The Motor screening Test (MOT), The Rapid Visual Information Processing (RVP), The Spatial Working Memory (SWM), and the Reaction Time (RT) tasks. These tasks were chosen because they measure executive functions relevant in evaluating ADHD and commonly used both in research and in clinical practice of ADHD. The reason for their use was the thought that they will be challenging and thus anxiety provoking for patients suffering from ADHD.

These tasks were chosen because they measure executive functions relevant in evaluating ADHD and commonly used both in research and in clinical practice of ADHD. The reason for their use was the thought that they will be challenging and thus anxiety provoking for patients suffering from ADHD.

Statistical Analysis

A paired t-test was applied for within subject comparison. Based on previous studies in adults we expected a sample size of 20 participants to suffice (Bloch et al., 2017; Pozzi et al., 2018).

No difference was found in state anxiety after administration of MPH (before 44.15 (±5.24) after 45.15 (±4.77) [t(−0.925), p = 0.367]; nor following administration of placebo (before 46.25 (±5.40) after 45.95 (±4.12) [t(1.03), p = 0.317].

However, baseline state anxiety scores at the second visit was significantly associated with previous experience at the first visit. Those who received MPH at the first visit (baseline anxiety 44 (±5/12) reported higher baseline state anxiety at the second visit (46. 22 ± (4.79) before administration of the placebo) [t(2.485), p < 0.05).

22 ± (4.79) before administration of the placebo) [t(2.485), p < 0.05).

The difference in baseline state anxiety scores for the participants who were given placebo in the first session was a non-significant decline [t(1.724), p= 0.115].

In the present study, there was no immediate effect of a single dose of MPH on state anxiety in ADHD pediatric patients. However, there was an incline in baseline anxiety at the second treatment visit in patients that received MPH at the first visit.

This may be considered to be a type of conditioned phenomenon, related to the experience with the medication, whose importance is in the possible clinical relevance. Seventeen percent of the pediatric patients that start MPH, stop after the first prescription (Wang et al., 2016), raising the probability of early side effects as a reason for discontinuation of MPH.

Non-adherence to efficient pharmacotherapy is a major obstacle in treating ADHD patients. The reasons for non-adherence vary, but a major reason is side effects. While anxiety is suggested as an important side effect (Pozzi et al., 2018), studies and meta-analyses support the opposite, i.e., that prolonged MPH treatment for ADHD causes a reduction in anxiety (Coughlin et al., 2015; Pozzi et al., 2018).

The reasons for non-adherence vary, but a major reason is side effects. While anxiety is suggested as an important side effect (Pozzi et al., 2018), studies and meta-analyses support the opposite, i.e., that prolonged MPH treatment for ADHD causes a reduction in anxiety (Coughlin et al., 2015; Pozzi et al., 2018).

Since most studies focused on prolonged therapy, they could not reveal an immediate anxiety provoking effect that is relevant to early medication withdrawal.

In a previous study of adult ADHD patients, our group demonstrated an anxiolytic effect of a single dose of MPH (Bloch et al., 2017). While one could argue that this relates to the age difference, it is important to stress that adult ADHD patients have, like the younger age groups, difficulties with adherence, and suffer from MPH-related side effects (Lichtenstein et al., 2012; Fredriksen and Peleikis, 2016). Thus, the age difference seems to not be supported as clinically-relevant to the different effect on anxiety. It is important to note that it was not an immediate anxiety provoking effect that we demonstrated in the current study.

It is important to note that it was not an immediate anxiety provoking effect that we demonstrated in the current study.

The finding of this pilot study relates to a delayed possibly conditioned anxiety provoking effect, that has not been studied yet. It is different from the anxiolytic effect of MPH on adherent patients that probably do not suffer from the aversive effect we encounter with some pediatric ADHD patients in the clinic (Kovshoff et al., 2016; Pozzi et al., 2018). If supported by larger studies, this type of anxiety can contribute to our understanding of non-adherence, and help develop new approaches to overcome these difficulties.

There are several limitations of the current study. First and most importantly, the sample was small, and with considerable age variation. Larger and more age homogenous studies with imaging evaluations, are needed in order to substantiate these findings and have a wider understanding of their implications.

The study was approved by the Shalvata ethics committee. Parents completed the informed consent process and signed the informed consent form. Children and adolescents signed the assent form.

Parents completed the informed consent process and signed the informed consent form. Children and adolescents signed the assent form.

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. MKr and MKo made major contribution to the acquisition of data. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data for the work, drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, provide approval for publication of the content, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Atkinson M., Hollis C. (2010). NICE guideline: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 95, 24–27. 10.1136/adc.2009.175943 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. Ed. 95, 24–27. 10.1136/adc.2009.175943 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Bloch Y., Aviram S., Segev A., Nitzan U., Levkovitz Y., Braw Y., et al.. (2017). Methylphenidate reduces state anxiety during a continuous performance test that distinguishes adult ADHD patients from controls. J. Atten. Disord. 21, 46–51. 10.1177/1087054712474949 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bussing R., Fernandez M., Harwood M., Wei H, Garvan C. W., Eyberg S. M., et al.. (2008). Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment 15, 317–328. 10.1177/1073191107313888 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z., Quinn P. D., Hur K., Gibbons R. D., Sjölander A., Larsson H., et al.. (2017). Association between medication use for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of motor vehicle crashes. JAMA Psychiatry 74, 597–603.

10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0659 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Coughlin C. G., Cohen S. C., Mulqueen J. M., Ferracioli-Oda E., Stuckelman Z. D., Bloch M. H. (2015). Meta-analysis: reduced risk of anxiety with psychostimulant treatment in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 25, 611–617. 10.1089/cap.2015.0075 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca C. R., Wood S. J., Anderson V., Buchanan J. A., Proffitt T. M., Mahony K., et al.. (2003). Normative data from the CANTAB. I: development of executive function over the lifespan. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 25, 242–254. 10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Erskine H. E., Norman R. E., Ferrari A. J., Chan G. C., Copeland W. E., Whiteford H. A., et al.. (2016). Long-term outcomes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad.

Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 841–850. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 55, 841–850. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.06.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Frank E., Ozon C., Nair V., Othee K. (2015). Examining why patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder lack adherence to medication over the long term: a review and analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry 76, e1459–e1468. 10.4088/JCP.14r09478 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen M., Peleikis D. E. (2016). Long-term pharmacotherapy of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a literature review and clinical study. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 118, 23–31. 10.1111/bcpt.12477 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Group M. C. (1999). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 1073–1086. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hall C. L., Guo B.

, Valentine A. Z., Groom M. J., Daley D., Sayal K., et al. (2019). The validity of the SNAP-IV in children displaying ADHD symptoms. Assessment 16:1073191119842255 10.1177/1073191119842255 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Valentine A. Z., Groom M. J., Daley D., Sayal K., et al. (2019). The validity of the SNAP-IV in children displaying ADHD symptoms. Assessment 16:1073191119842255 10.1177/1073191119842255 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Kovshoff H., Banaschewski T., Buitelaar J. K., Carucci S., Coghill D., Danckaerts M., et al.. (2016). Reports of perceived adverse events of stimulant medication on cognition, motivation, and mood: qualitative investigation and the generation of items for the medication and cognition rating scale. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 26, 537–547. 10.1089/cap.2015.0218 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larson K., Russ S. A., Kahn R. S., Halfon N. (2011). Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics 127, 462–470. 10.1542/peds.2010-0165 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P., Halldner L., Zetterqvist J., Sjölander A., Serlachius E., Fazel S.

, et al.. (2012). Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2006–2014. 10.1056/NEJMoa1203241 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, et al.. (2012). Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2006–2014. 10.1056/NEJMoa1203241 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Oei T. P., Evans L., Crook G. M. (1990). Utility and validity of the STAI with anxiety disorder patients. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 29(Pt 4), 429–432. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1990.tb00906.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Okun A., Stein R. E., Bauman L. J., Silver E. (1996). Content validity of the psychiatric symptom index, CES-depression scale, and state-trait anxiety inventory from the perspective of DSM-IV. Psychol. Rep. 79(3 Pt 1), 1059–1069. 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.1059 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi M., Carnovale C., Peeters G., Gentili M., Antoniazzi S., Radice S., et al.. (2018). Adverse drug events related to mood and emotion inpaediatric patients treated for ADHD: a meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 238, 161–178. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.05.021 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi V.

, Pourtois G. (2012). Transient state-dependent fluctuations in anxiety measured using STAI, POMS, PANAS, or VAS: a comparative review. Anxiety Stress Coping 25, 603–645. 10.1080/10615806.2011.582948 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Pourtois G. (2012). Transient state-dependent fluctuations in anxiety measured using STAI, POMS, PANAS, or VAS: a comparative review. Anxiety Stress Coping 25, 603–645. 10.1080/10615806.2011.582948 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Sayal K., Prasad V., Daley D., Ford T., Coghill D. (2018). ADHD in children and young people: prevalence, care pathways, and service provision. Lancet Psychiatry 5, 175–186. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30167-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sciberras E., Lycett K., Efron D., Mensah F., Gerner B., Hiscock H. (2014). Anxiety in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 133, 801–808. 10.1542/peds.2013-3686 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seixas M., Weiss M., Müller U. (2012). Systematic review of national and international guidelines on attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Psychopharmacol. 26, 753–765. 10.1177/0269881111412095 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D. V., Sheehan K.

H., Shytle R. D., Janavs J., Bannon Y., Rogers J. E., et al.. (2010). Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 313–326. 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

H., Shytle R. D., Janavs J., Bannon Y., Rogers J. E., et al.. (2010). Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J. Clin. Psychiatry 71, 313–326. 10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Spielberger C. D., Gorsuch R. L., Lushene R. E. (1970). Manual for the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Self-Evaluation Questionnaire). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychological Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement Management. Wolraich M., Brownm L, Brown R. T., DuPaul. G., et al.. (2011). ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 128, 1007–1022. 10.1542/peds.2011-2654 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Teichman Y., Melink C. (1984). Hebrew Manual for the STAI, STAIC, 2nd Edn.

Ramot: Ramat Aviv. [Google Scholar]

Ramot: Ramat Aviv. [Google Scholar] - Wang L. J., Yang K. C., Lee S. Y., Yang C., Huang T. S., Lee T. L., et al.. (2016). Initiation and persistence of pharmacotherapy for youths with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 11:e0161061. 10.1371/journal.pone.0161061 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zohar A. H., Bruno R. (1997). Normative and pathological obsessive-compulsive behavior and ideation in childhood: a question of timing. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 38, 993–999. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01616.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience are provided here courtesy of Frontiers Media SA

Do we need a magic pill to improve memory and attention?

- Zaria Gorvette

- BBC Capital

Image credit: Getty Images

But are they really effective? And what will happen if everyone starts using them?

Honoré de Balzac was an avid coffee drinker who believed that coffee was the best way to stimulate the brain. Every evening he went in search of night coffee shops, and then wrote until morning. nine0011

Every evening he went in search of night coffee shops, and then wrote until morning. nine0011

It is said that he drank 50 cups of his favorite drink daily. And ... he literally swallowed ground coffee with spoons - it "worked" well on an empty stomach.

The writer said that after a sip of coffee powder "the ideas in my head began to march briskly, like battalions of a great army that go to the battlefield to rush into battle."

Obviously it really helped. Balzac was an incredibly prolific writer, writing almost a hundred novels, short stories and plays. True, he died of heart failure at the age of only 51 years. nine0011

Image copyright, Getty Images

Caption before photo,Honore de Balzac was one of the first proponents of nootropics - to stimulate creativity, he consumed huge amounts of caffeine daily

For centuries, the only help in overcoming the mountain of boring and painstaking work was caffeine .

And only the last generation of workers began to experiment with substances that, in their opinion, increase intellectual abilities and contribute to fantastic performance. nine0011

In fact, some of these "smart drugs" ("mind pills") are already quite popular. A recent survey of tens of thousands of Americans found that 30% of them had taken such drugs within the past year.

Perhaps soon we will start doing all this.

But what will be the consequences? Will a new generation of giants of thought appear, whose brilliant inventions will mark the space age of mankind? Will we achieve insane economic growth? Or maybe the working week will become noticeably shorter, because people will work more efficiently? nine0011

"Changes the mind"

To answer these questions, we first need to figure out what scientists are offering us.

The first drug of this group, piracetam, was synthesized in the early 1960s by the Romanian chemist and psychologist Corneliu George. He was looking for a drug that would cause drowsiness, and after a few months he came up with the drug Compound 6215.

He was looking for a drug that would cause drowsiness, and after a few months he came up with the drug Compound 6215.

It was safe, but there was no sedative effect either. It seemed to be the other way around. In patients who took it for a month, memory improved significantly. nine0011

- Is legalization of marijuana a headache for employers?

- The LSD cult that transformed America

- What to eat for clarity of thought and good memory

- Coffee and cigars: what is known about the main defendant in the "cocaine case"?

- Coffee does more good than harm

George immediately realized the significance of his invention and coined the term "nootropic" - a combination of the Greek words νους ("mind") and τροπή ("turning, hindering, changing").

Today piracetam is the favorite "magic pill" of students and young professionals who seek to improve their performance. Although several decades after the invention of the drug, there is no sufficient evidence of its effectiveness. nine0011

Although several decades after the invention of the drug, there is no sufficient evidence of its effectiveness. nine0011

In the UK, Piracetam is available by prescription only, although the US Food and Drug Administration has not approved Piracetam and has not allowed Piracetam to be sold as a dietary supplement.

Texas entrepreneur and podcast author Mansal Denton takes phenylpiracetam, a close analogue of piracetam developed in the Soviet Union to help astronauts cope with the stresses of space life.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Creatine has always been a mainstay of bodybuilders' dietary supplements, but now it is also used to improve mental alertness

"When I use this drug, my speech skills improve, and therefore I usually record a lot of podcasts on such days," he says.

In fact, this effect is quite typical for nootropics. Despite the abundance of their passionate admirers, the intellectual effect is almost imperceptible or non-existent.

Brain gain? nine0042

Take, for example, creatine monohydrate. This white powder dietary supplement is usually mixed with sugary drinks or milkshakes, or taken as a tablet.

The substance enters the brain, and recent research shows that creatine does improve working memory and intelligence.

While creatine is a relatively recent discovery by ambitious young professionals, it has been known to bodybuilders for decades. The substance is the main element of many dietary supplements, and in the US, sports supplements are a multi-billion dollar industry. nine0011

In a survey last year by Ipsos Public Affairs, 22% of adults said they had taken a dietary supplement in the last year.

If creatine had a serious effect on human performance, we would certainly notice it.

Of course, there are drugs with a stronger effect.

"Some of them are quite effective," says Andrew Huberman, a neuroscientist at Stanford University.

There is one category of nootropics that scientists and biohackers (amateurs who try to change the physiology of their body at the molecular level) are very interested in. nine0011

These are psychostimulants.

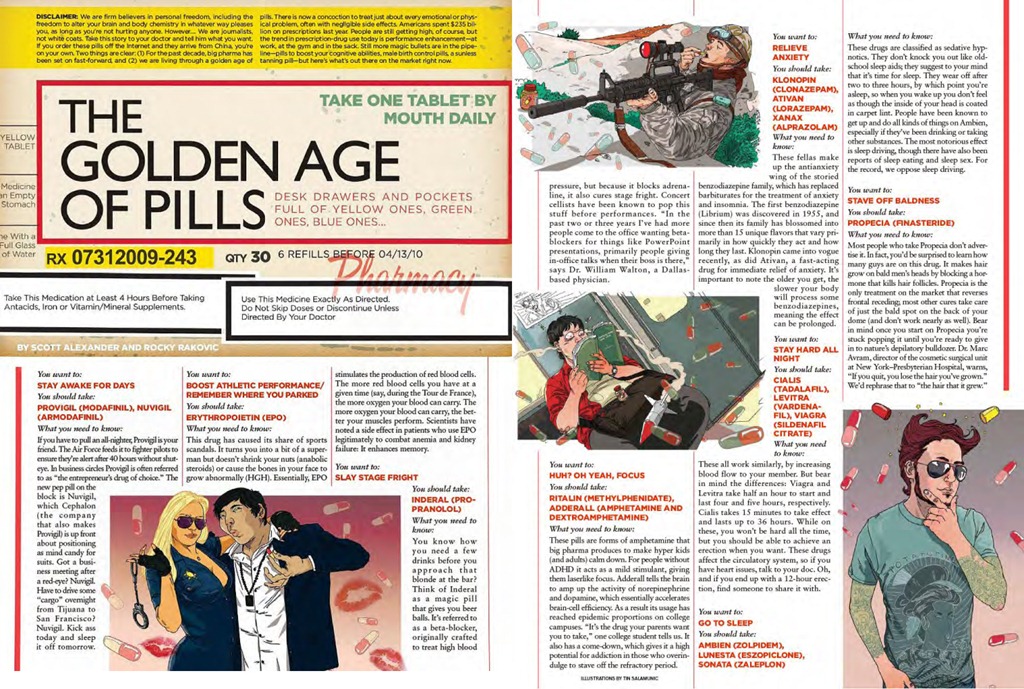

The most common of these are amphetamines and methylphenidate, which are sold by prescription under the brand names Adderall and Ritalin.

In the United States, both drugs are approved for the treatment of people with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.

But now they are often abused by people whose work requires a high concentration of attention.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Ritalin is a psychostimulant used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but is often used simply to improve attention

Amphetamines have long established themselves as nootropics.

This feature was well known to the legendary Hungarian mathematician Pal Erdős, who with the help of amphetamines withstood 19-hour mathematical sessions.

Writer Graham Greene used them to write two books at the same time. Today, their use is quite common among journalists, creative professionals and financiers.

Those who have taken them swear that they really change consciousness, although not in the way you expected. nine0011

Back in 2015, a scientific review showed that the effect of amphetamines on intelligence is rather "modest". But most people use them to improve their mental abilities, but rather to increase energy and motivation to work.

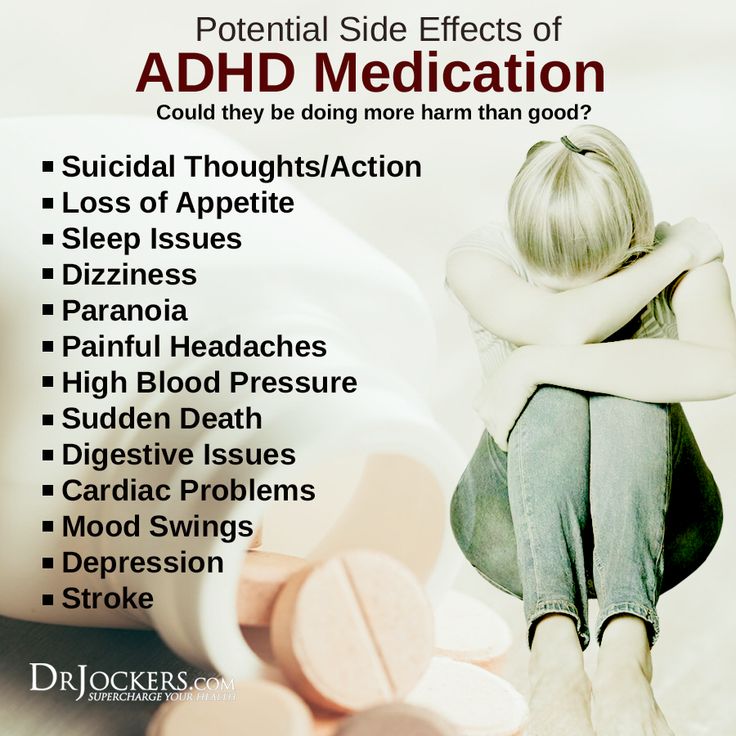

(Both drugs have serious side effects, more on that later).

One of the effects of psychostimulants like Adderall and Ritalin is to make it easier to perform psychologically exhausting tasks.

One study showed that under the influence of "Ritalin" mathematical problems seemed to be studied more interesting. nine0011

Assuming that all people start using mental stimulants, we will have at least two main consequences.

First, people will stop avoiding unpleasant tasks.

Tired office workers who have spent years perfecting the art of idleness in the workplace will frantically sort through documents, update spreadsheets, and enthusiastically attend boring meetings.

- How to prevent employees from "surfing the Internet" during working hours

- What gives us the ability to think flexibly

- One simple trick to improve memory

- The withdrawal syndrome: a mysterious disease in Sweden

Secondly, competition among employees will begin to skyrocket. This side effect of nootropics has been talked about for quite some time.

But is it so good, the question is debatable.

"Many in Silicon Valley and Wall Street are already using mental stimulants. It's starting to feel like a professional mental sport where the stakes and competition are rising daily," said Jeffrey Wu, CEO and co-founder of HVMN, which makes a line of nootropic supplements. . nine0011

. nine0011

But there are significant drawbacks in this. Amphetamines are structurally similar to methamphetamine, a powerful addictive drug that has ruined countless lives. It can also have fatal consequences.

There are many reports that Adderall and Ritalin are addictive. And they also have a number of side effects, such as nervousness, anxiety, insomnia, stomach pain, and even hair loss.

Finally, psychostimulants are unlikely to increase overall productivity. nine0011

An important question, how will the person feel the next day? You can work at your peak for 12 hours, but then for a day or two you will feel a strong decline in activity.

However, we still have a few proven options that can be bought without a prescription in every coffee shop.

This is, first of all, coffee. Unfortunately, no one has yet calculated the impact of caffeine on economic growth, but many other studies have found many of its benefits. nine0011

nine0011

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Coffee seems to be the best stimulant of intellectual activity after all

Interestingly, caffeine was more effective than a commercial supplement based on it, which is produced by Woo and now costs $17.95 for 60 tablets.

Well, and secondly, nicotine. Scientists are increasingly realizing that it has a powerful nootropic effect that improves a person's memory and helps focus.

Although the risks and side effects are well known to everyone. nine0011

"Some famous neuroscientists chew Nicorette to improve their mental alertness. But they've all smoked in the past, so it's probably a replacement for a bad habit," Guberman notes.

What happens if we all start taking brain stimulation drugs?

It turns out that many of us already do this on a daily basis. And Balzac could tell you about it.

The purpose of the article is general information. It cannot replace the medical advice of a specialist. The BBC is not responsible for any diagnosis made by a reader based on information from the site. The BBC is not responsible for the content of any external Internet sites to which the authors of the article link, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service referred to

It cannot replace the medical advice of a specialist. The BBC is not responsible for any diagnosis made by a reader based on information from the site. The BBC is not responsible for the content of any external Internet sites to which the authors of the article link, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service referred to

Medicines for mental illness

The effectiveness of drug therapy with psychotropic drugs is determined by the compliance of the choice of the drug with the clinical picture of the disease, the correct dosage regimen, the method of administration and the duration of the therapeutic course. As in any field of medicine, in psychiatry it is necessary to take into account the entire complex of drugs that the patient takes, since their mutual action can lead not only to a change in the nature of the effects of each of them, but also to the occurrence of undesirable consequences. nine0011

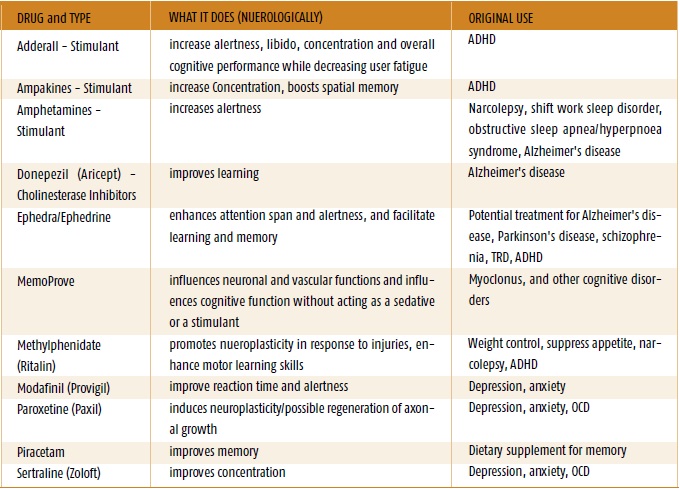

There are several approaches to the classification of psychotropic drugs. Table 1 shows the classification proposed by the WHO in 1990, adapted to include some domestic medicines.

Table 1 shows the classification proposed by the WHO in 1990, adapted to include some domestic medicines.

Table 1. Classification of psychopharmacological drugs.

| Grade | Chemical group | Generic and common trade names |

| Antipsychotics | Phenothiazines | Chlorpromazine (chlorpromazine), promazine, thioproperazine (majeptil), trifluperazine (stelazine, triftazine), periciazine (neuleptil), alimemazine (teralen) |

| nine0008 Xanthenes and thioxanthenes | Chlorprothixene, Clopenthixol (Clopexol), Flupenthixol (Fluanxol) | |

| Butyrophenones | Haloperidol, trifluperidol (trisedil, triperidol), droperidol | |

| Piperidine derivatives | Fluspirilene (imap), pimozide (orap), penfluridol (semap) | |

| Cyclic derivatives | Risperidone (rispolept), ritanserin, clozapine (leponex, azaleptin) | nine0241 |

| Indole and naphthol derivatives | Molindol (moban) | |

| Benzamide derivatives | Sulpiride (eglonil), metoclopramide, racloprid, amisulpiride, sultopride, tiapride (tiapridal) | nine0241 |

| Derivatives of other substances | Olanzapine (Zyprexa) | |

| Tranquilizers | Benzodiazepines | Diazepam (Valium, Seduxen, Relanium), Chlordiazepoxide (Librium, Elenium), Nitrazempam (Radedorm, Eunoctin) |

| Triazolobenzodiazepines | Alprazolam (Xanax), Triazolam (Chalcion), Madizopam (Dormicum) | |

| Heterocyclic | Brotizopam (lendormin) nine0232 | |

| Diphenylmethane derivatives | Benactizine (staurodorm), hydroxyzine (atarax) | |

| Heterocyclic derivatives | Busperone (buspar), zopiclone (imovan), clometizol, gemineurin, zolpidem (ivadal) | |

| Antidepressants | Tricyclic | Amitriptyline (Triptisol, Elivel), Imipramine (Melipramine), Clomipramine (Anafranil), Tianeptine (Coaxil) |

| Tetracyclic | Mianserin (Lerivon), Maprotiline (Ludiomil), Pirlindol (Pyrazidol), | |

| Serotonergic | Citalopram (Seroprax), Sertraline (Zoloft), Paroxetine (Paxil), Viloxazine (Vivalan), Fluoxetine (Prozac), Fluvoxamine (Fevarin), nine0232 | |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA) | Mirtazapine (remeron), milnacipran (ixel) | |

| MAO inhibitors (reversible) | Moclobemide (Aurorix) nine0232 | |

| Nootropics (and substances with a nootropic component of action) | Pyrrolidone derivatives | Piracetam (nootropil) |

| Cyclic derivatives, GABA | nine0229 ||

| Acetylcholine precursors | Deanol (acti-5) | |

| Pyridoxine derivatives | Pyritinol nine0232 | |

| Devincan derivatives | Vincamine, Vinpocetine (Cavinton) | |

| Neuropeptides | Vasopressin, oxytocin, thyroliberin, cholecystokinin | |

Antioxidants | Ionol, mexidol, tocopherol | |

| Stimulants | Phenethylamine derivatives | Amphetamine, salbutamol, methamphetamine (Pervitine) nine0232 |

| Sydnonimine derivatives | Sydnocarb | |

| Heterocyclic | Methylphnidate (Ritalin) | |

| Purine derivatives | Caffeine | |

| Normotimics | Metal salts | Lithium salts (lithium carbonate, lithium hydroxybutyrate, lithonite, micalite), rubidium chloride, cesium chloride | nine0241

| Assembly group | Carbamazepine (Finlepsin, Tegretol), Valpromide (Depamide), Sodium Valproate (Depakine, Convulex) | |

| Additional group | Assembly group | nine0229

The main clinical characteristics and side effects of the listed classes of pharmacological drugs are given below.

Antipsychotics

Clinical characteristics. This class of drugs is central to the treatment of psychosis. However, the scope of their application is not limited to this, since in small doses in combination with other psychotropic drugs they can be used in the treatment of affective disorders, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive and somatoform disorders, with decompensation of personality disorders. nine0011

Regardless of the characteristics of the chemical structure and mechanism of action, all drugs of this group have similar clinical properties: they have a pronounced antipsychotic effect, reduce psychomotor activity and reduce mental arousal, neurotropic effect manifested in the development of extrapyramidal and vegetovascular disorders, many of they also have antiemetic properties.

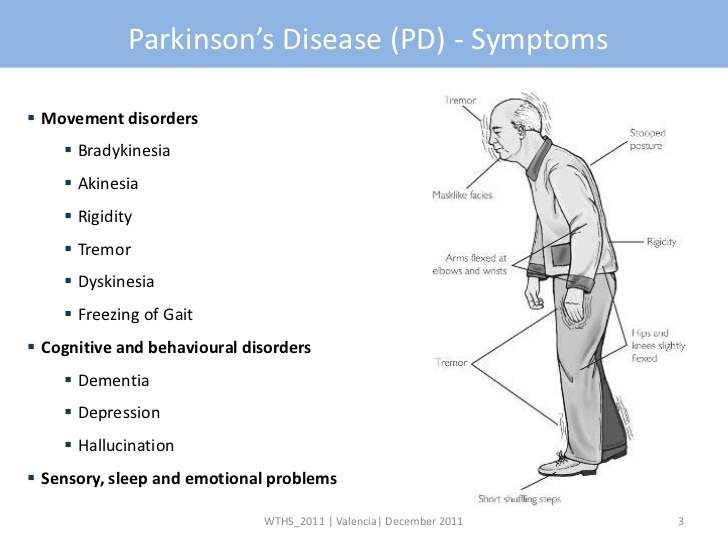

Side effects. The main side effects in the treatment of neuroleptics form the neuroleptic syndrome. The leading clinical manifestations of this syndrome are extrapyramidal disorders with a predominance of either hypo- or hyperkinetic disorders. Hypokinetic disorders include drug-induced parkinsonism, manifested by increased muscle tone, lockjaw, rigidity, stiffness, and slowness of movement and speech. Hyperkinetic disturbances include tremor and hyperkinesis. Usually in the clinical picture in various combinations there are both hypo- and hyperkinetic disorders. The phenomena of dyskinesia can be paroxysmal in nature, localized in the mouth area and manifested by spasmodic contractions of the muscles of the pharynx, tongue, lips, jaws. Often there are phenomena of akathisia - feelings of restlessness, "restlessness in the legs", combined with tasikinesia (the need to move, change position). A special group of dyskinesias includes tardive dyskinesia, which occurs after 2-3 years of taking antipsychotics and is expressed in involuntary movements of the lips, tongue, face. nine0011

The leading clinical manifestations of this syndrome are extrapyramidal disorders with a predominance of either hypo- or hyperkinetic disorders. Hypokinetic disorders include drug-induced parkinsonism, manifested by increased muscle tone, lockjaw, rigidity, stiffness, and slowness of movement and speech. Hyperkinetic disturbances include tremor and hyperkinesis. Usually in the clinical picture in various combinations there are both hypo- and hyperkinetic disorders. The phenomena of dyskinesia can be paroxysmal in nature, localized in the mouth area and manifested by spasmodic contractions of the muscles of the pharynx, tongue, lips, jaws. Often there are phenomena of akathisia - feelings of restlessness, "restlessness in the legs", combined with tasikinesia (the need to move, change position). A special group of dyskinesias includes tardive dyskinesia, which occurs after 2-3 years of taking antipsychotics and is expressed in involuntary movements of the lips, tongue, face. nine0011

Among the disorders of the autonomic nervous system, orthostatic hypotension, sweating, weight gain, changes in appetite, constipation, diarrhea are most often observed. Sometimes there are anticholinergic effects - visual disturbances, dysuric phenomena. Possible functional disorders of the cardiovascular system with changes in the ECG in the form of an increase in the Q-T interval, a decrease in the T wave or its inversion, tachycardia or bradycardia. Sometimes there are side effects in the form of photosensitivity, dermatitis, skin pigmentation; skin allergic reactions are possible. nine0011

Sometimes there are anticholinergic effects - visual disturbances, dysuric phenomena. Possible functional disorders of the cardiovascular system with changes in the ECG in the form of an increase in the Q-T interval, a decrease in the T wave or its inversion, tachycardia or bradycardia. Sometimes there are side effects in the form of photosensitivity, dermatitis, skin pigmentation; skin allergic reactions are possible. nine0011

Antipsychotics of new generations, compared with traditional derivatives of phenothiazines and butyrophenones, cause significantly fewer side effects and complications.

Tranquilizers

Clinical characteristics. This group includes psychopharmacological agents that relieve anxiety, emotional tension, fear of non-psychotic origin, and facilitate the process of adaptation to stressful factors. Many of them have anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant properties. Their use in therapeutic doses does not cause significant changes in cognitive activity and perception. Many of the drugs in this group have a pronounced hypnotic effect and are used primarily as hypnotics. Unlike neuroleptics, tranquilizers do not have a pronounced antipsychotic activity and are used as an additional tool in the treatment of psychosis - to stop psychomotor agitation and correct the side effects of neuroleptics. nine0011

Many of the drugs in this group have a pronounced hypnotic effect and are used primarily as hypnotics. Unlike neuroleptics, tranquilizers do not have a pronounced antipsychotic activity and are used as an additional tool in the treatment of psychosis - to stop psychomotor agitation and correct the side effects of neuroleptics. nine0011

Side effects of during treatment with tranquilizers are most often manifested by daytime drowsiness, lethargy, muscle weakness, impaired concentration, short-term memory, as well as a slowdown in the rate of mental reactions. In some cases, paradoxical reactions develop in the form of anxiety, insomnia, psychomotor agitation, hallucinations. Among the dysfunctions of the autonomic nervous system and other organs and systems, hypotension, constipation, nausea, urinary retention or incontinence, decreased libido are noted. Long-term use of tranquilizers is dangerous due to the possibility of developing addiction to them, i.e. physical and mental dependence. nine0011

nine0011

Antidepressants

Clinical characteristics. This class of drugs includes drugs that increase the pathological hypothymic effect, as well as reduce somatovegetative disorders caused by depression. A growing body of scientific evidence now suggests that antidepressants are effective for phobic anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. It is assumed that in these cases, not the actual antidepressant, but the anti-obsessional and antiphobic effects are realized. There is data confirming the ability of many antidepressants to increase the threshold of pain sensitivity, to have a preventive effect in migraine and vegetative crises. nine0011

Side effects. Side effects related to the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system are expressed as dizziness, tremor, dysarthria, impaired consciousness in the form of delirium, epileptiform seizures. Possible exacerbation of anxious disorders, activation of suicidal tendencies, inversion of affect, drowsiness or, conversely, insomnia. Side effects may be manifested by hypotension, sinus tachycardia, arrhythmia, impaired atrioventricular conduction. nine0011

Side effects may be manifested by hypotension, sinus tachycardia, arrhythmia, impaired atrioventricular conduction. nine0011

When taking tricyclic antidepressants, various anticholinergic effects are often observed, as well as an increase in appetite. With the simultaneous use of MAO inhibitors with food products containing tyramine or its precursor - tyrosine (cheeses, etc.), a "cheese effect" occurs, manifested by hypertension, hyperthermia, convulsions and sometimes leading to death.

When prescribing serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and reversible MAO-A inhibitors, there may be disturbances in the activity of the gastrointestinal tract, headaches, insomnia, anxiety, and impotence may develop against the background of SSRIs. In the case of a combination of SSRIs with drugs of the tricyclic group, the formation of the so-called serotonin syndrome, which is manifested by an increase in body temperature and signs of intoxication, is possible. nine0011

Normotimics

Clinical characteristics. Normotimics include drugs that regulate affective manifestations and have a preventive effect in phasic affective psychoses. Some of these drugs are anticonvulsants.

Normotimics include drugs that regulate affective manifestations and have a preventive effect in phasic affective psychoses. Some of these drugs are anticonvulsants.

The most common side effects of when using lithium salts are tremor. Often there are violations of the function of the gastrointestinal tract - nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea. Often there is an increase in body weight, polydipsia, polyuria, hypothyroidism. Acne, maculo-papular rash, alopecia, as well as worsening of psoriasis are possible. nine0011 Signs of severe toxic conditions and drug overdose are a metallic taste in the mouth, thirst, pronounced tremor, dysarthria, ataxia; in these cases, the drug should be stopped immediately. It should also be noted that side effects may be associated with non-compliance with the diet - a large intake of fluids, salt, smoked meats, cheeses. Side effects of anticonvulsants are most often associated with functional disorders of the central nervous system and manifest themselves as lethargy, drowsiness, ataxia. With a pronounced cardiotoxic effect, atrioventricular block may develop. Nootropics Clinical characteristics. Nootropics include drugs that can positively influence cognitive functions, stimulate learning, enhance memory processes, increase brain resistance to various adverse factors (in particular, to hypoxia) and extreme stress. However, they do not have a direct stimulating effect on mental activity, although in some cases they can cause anxiety and sleep disturbance. nine0011 Side effects are rare. Sometimes there are nervousness, irritability, elements of psychomotor agitation and disinhibition of drives, as well as anxiety and insomnia. Dizziness, headache, nausea and abdominal pain may occur. Psychostimulants Clinical characteristics. Hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor can be observed much less frequently. The severity of these phenomena is significantly reduced with a smooth increase in doses. nine0011

Hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor can be observed much less frequently. The severity of these phenomena is significantly reduced with a smooth increase in doses. nine0011

Learn more